Semyon Bychkov interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

Conductor Semyon Bychkov

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

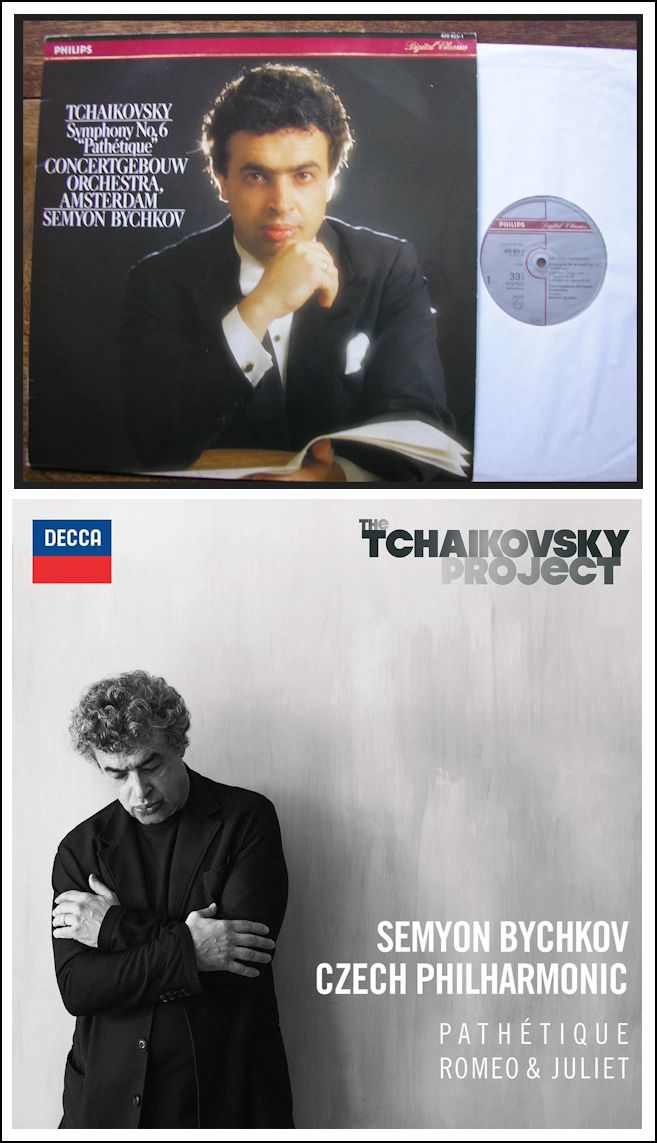

Born in St. Petersburg in 1952, Semyon Bychkov immigrated to the United States in 1975 and has been based in Europe since the mid-1980s. In common with the Czech Philharmonic, of which he became Music Director in 2018, Bychkov has one foot firmly in the cultures both of the East and the West. Following his early concerts with the Orchestra in 2013, Bychkov devised The Tchaikovsky Project, a series of concerts, residencies and studio recordings which allowed them the luxury of exploring Tchaikovsky’s music together, both in Prague’s Rudolfinum and abroad.

Bychkov won the Rachmaninov Conducting Competition when he was 20 years old. Two years later, having been denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, he left the former Soviet Union where, from the age of five he was singled out for an extraordinarily privileged musical education. Starting with piano, Bychkov was later selected to study at the Glinka Choir School where he received his first conducting lesson aged 13. Four years later he was accepted at the Leningrad Conservatory as a student of the legendary Ilya Musin.

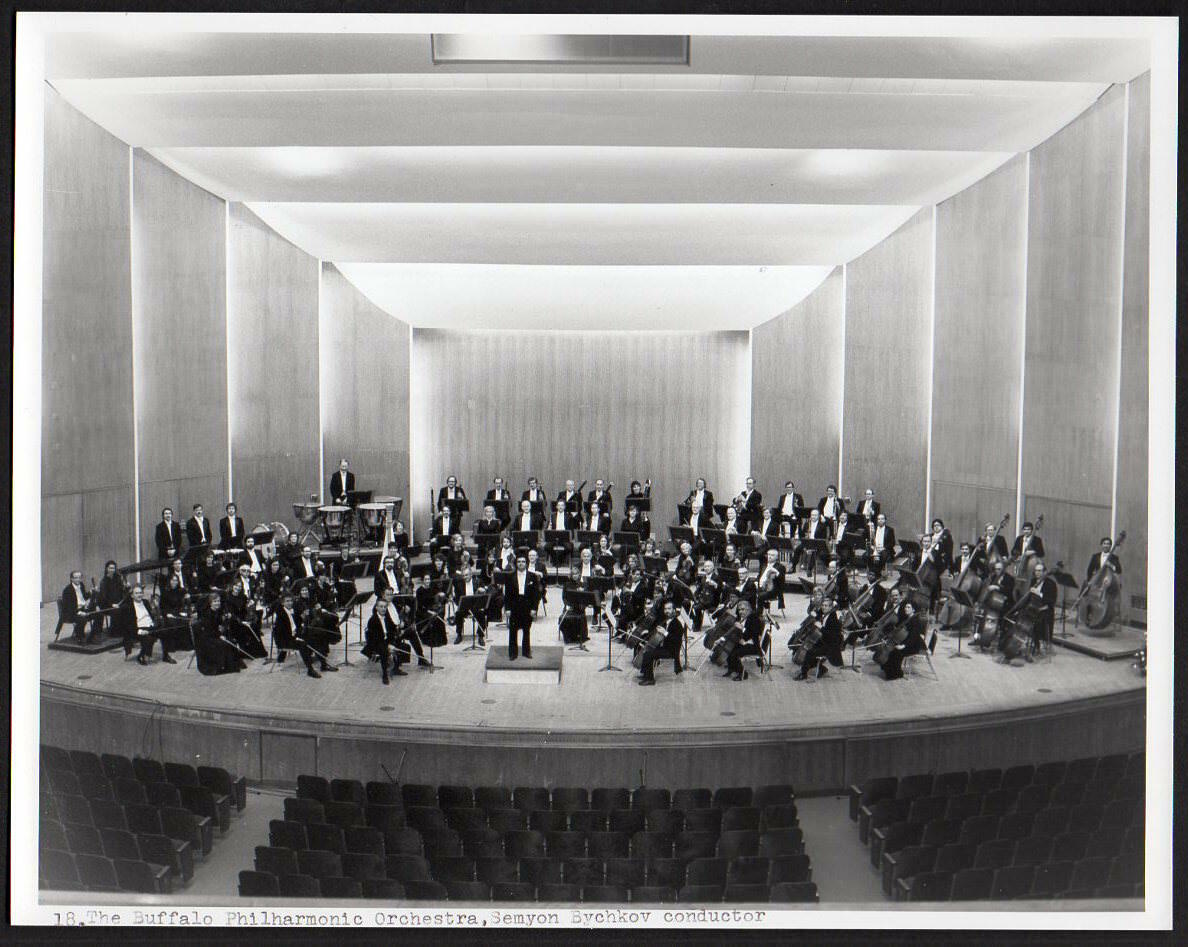

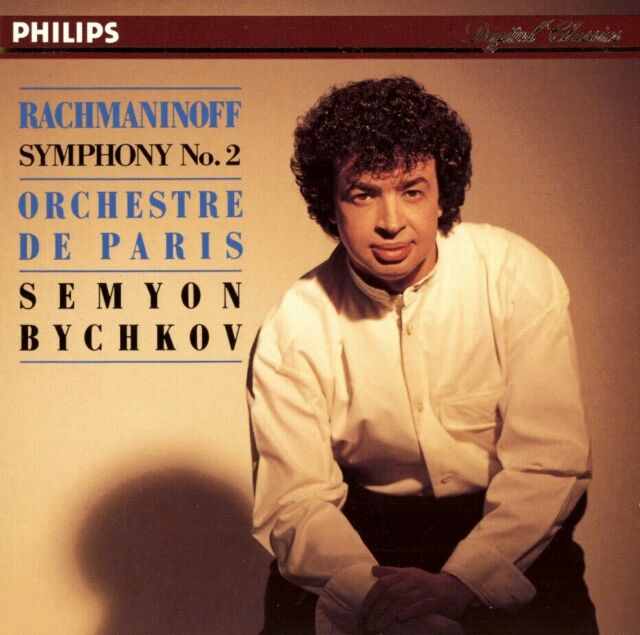

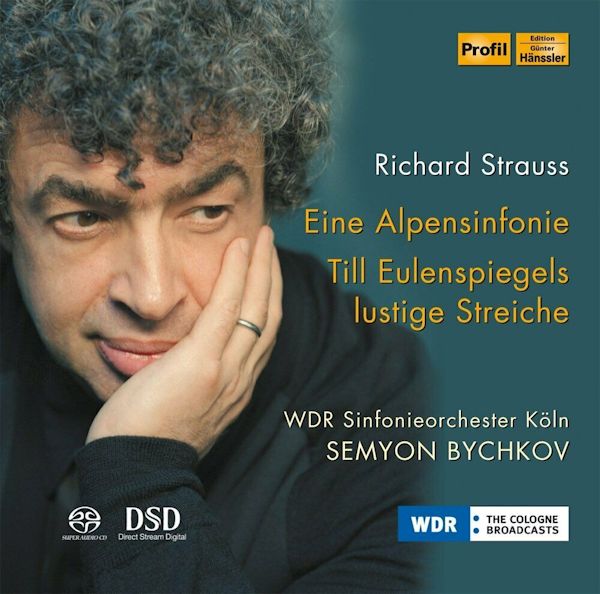

By the time Bychkov returned to St. Petersburg in 1989 as the Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor, he had enjoyed success in the US as Music Director of the Grand Rapids Symphony Orchestra and the Buffalo Philharmonic. His international career, which began in France with Opéra de Lyon and at the Aix-en-Provence Festival, took off with a series of high-profile cancellations which resulted in invitations to conduct the New York Philharmonic, Berlin Philharmonic and Royal Concertgebouw Orchestras. In 1989, he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris; in 1997, Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne; and the following year, Chief Conductor of the Dresden Semperoper.

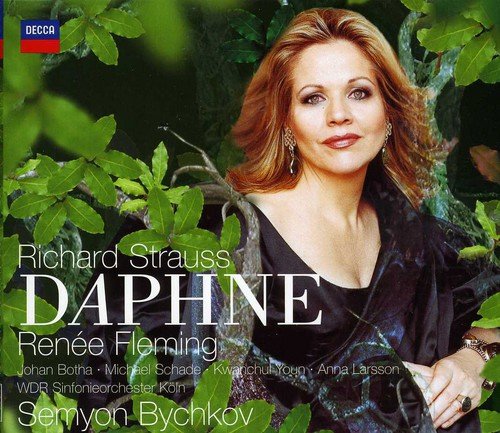

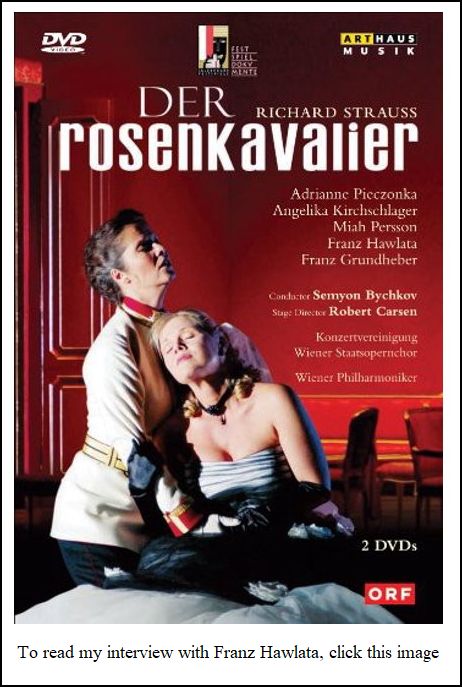

Bychkov’s symphonic and operatic repertoire is wide-ranging. He conducts in all the major houses including La Scala, Opéra national de Paris, Dresden Semperoper, Wiener Staatsoper, New York’s Metropolitan Opera, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden and Teatro Real. Madrid. While Principal Guest Conductor of Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, his productions of Janáček’s Jenůfa, Schubert’s Fierrabras, Puccini’s La bohème, Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk and Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov each won the prestigious Premio Abbiati. In 2018, he conducted Wagner’s Parsifal both at the Wiener Staatsoper and Bayreuth. Other new productions in Vienna include Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier and Daphne, Wagner’s_Lohengrin_ and Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina; while in London, he made his debut with a new production of Strauss’ Elektra, and subsequently conducted new productions of Mozart’s Così fan tutte [DVD cover shown below], Strauss’ Die Frau ohne Schatten and Wagner’s Tannhäuser.

On the concert platform, the combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy has ensured that Bychkov’s performances are highly anticipated. In the UK, in addition to regular performances with the London Symphony Orchestra, his honorary titles at the Royal Academy of Music and the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – reflect the warmth of the relationships. In Europe, he tours frequently with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic and Munich Philharmonic, as well as being an annual guest of the Berlin Philharmonic, the Leipzig Gewandhaus, the Orchestre National de France and the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia; in the US, he can be heard with the New York Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony, Los Angeles Symphony, Philadelphia and Cleveland Orchestras.

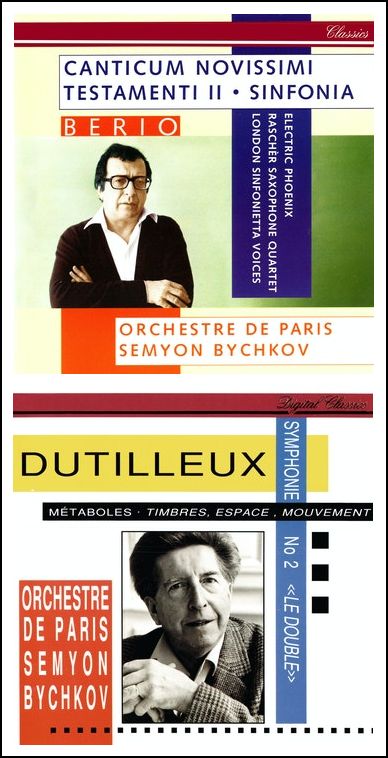

Recognised for his interpretations of the core repertoire, Bychkov has worked closely with many extraordinary contemporary composers including Luciano Berio, Henri Dutilleux and Maurizio Kagel. In recent seasons he has worked closely with René Staar, Thomas Larcher, Richard Dubignon, Detlev Glanert and Julian Anderson, conducting premières of their works with the Vienna Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Royal Concertgebouw and the BBC Symphony Orchestra at the BBC Proms.

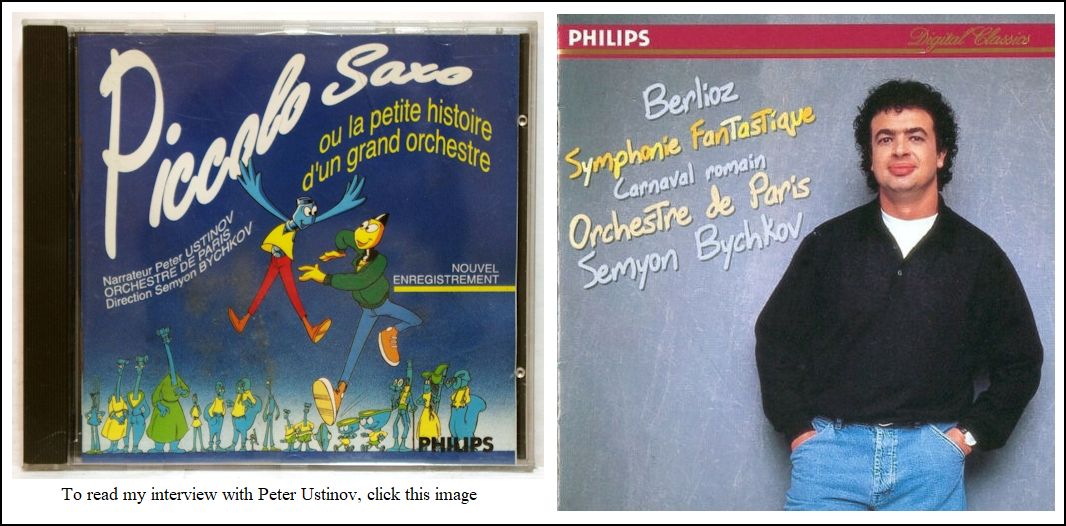

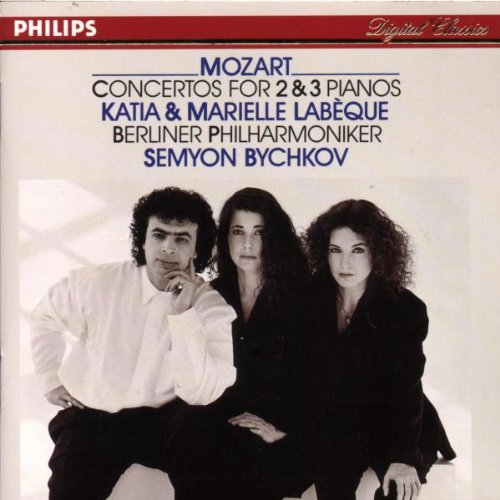

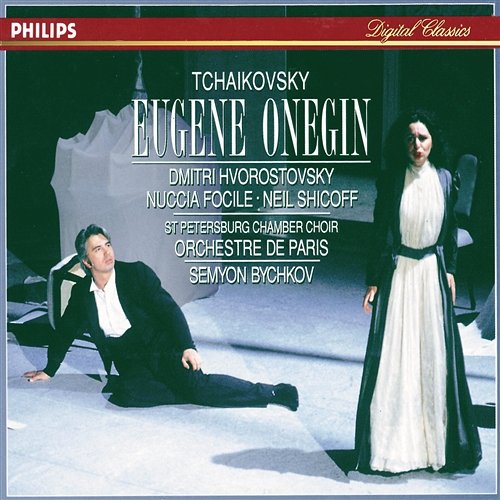

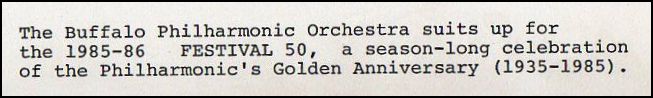

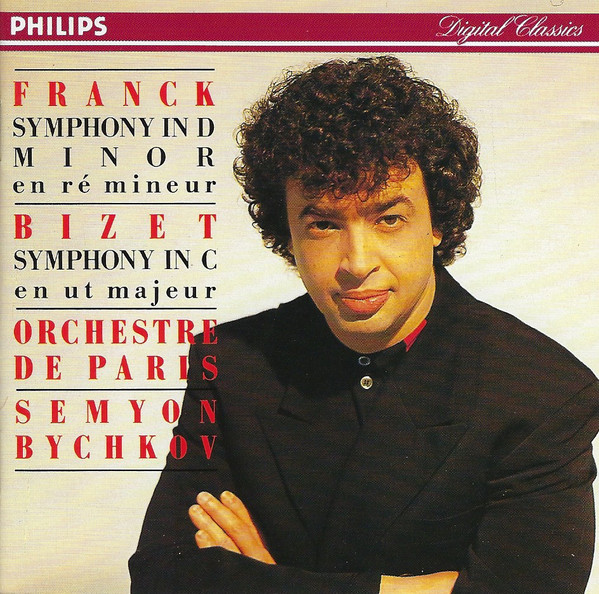

Bychkov’s recording career began in 1986 when he signed with Philips and began a significant collaboration which produced an extensive discography with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia, London Philharmonic and Orchestre de Paris. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings – the result of his 13-year collaboration (1997-2010) with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne – include a complete cycle of Brahms Symphonies, and works by Strauss (Elektra,Daphne, Ein Heldenleben, Metamorphosen, Alpensinfonie, Till Eulenspiegel), Mahler (Symphony No. 3, Das Lied von der Erde), Shostakovich (Symphony Nos. 4, 7, 8, 10, 11), Rachmaninov (The Bells, Symphonic Dances,Symphony No. 2), Verdi (Requiem), Detlev Glanert and York Höller. His recording of Wagner’s Lohengrin was voted BBC Music Magazine’s Disc of the Year in 2010; his recording of César Franck’s Symphony in D minor was the Recommended Recording of BBC Radio 3’s Record Review’s Building a Library; and his recent recording of Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was selected as BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month.

Bychkov was named 2015’s Conductor of the Year by the International Opera Awards.

== Text of biography from IMG Artists

In the fall of 1988, Bychkov was in Chicago for engagements with both Lyric Opera and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. First came nine performances of Don Giovanni at Lyric, with Samuel Ramey, Claudio Desderi, Carol Vaness, Karita Mattila, Marie McLaughlin, Gösta Winbergh, and John Macurdy in the Ponnelle production which was lit by Duane Schuler. Then in mid-December he led the CSO in the Symphony #44 of Haydn, the Symphonic Dances of Rachmaninoff, and the Mendelssohn _Piano Concerto #1_played by Stephen Hough. [Names which are links on this webpage refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website.]

We met at the end of November, between performances of the Mozart opera, and spent more than an hour discussing his musical ideas and his significant accomplishments... to that date! Needless to say, since that time he has continued to bring first-rate performances in concert halls and opera houses, to say nothing of the many recordings under his baton.

As we spoke, he was about to complete his tenure with the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, and take up a new position with the Orchestre de Paris. We started, however, with his beginnings in Russia . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: When you started out in music, why did you go into conducting instead of piano or violin?

Semyon Bychkov: Actually, I was studying piano when I was five, and then I entered the Glinka Choir School in Leningrad. It’s a very famous boys choir which has a three hundred year old tradition. [The ensemble is the oldest professional academic institution in Russia. It dates back to 1476 when the Sovereign’s Chorus of Singing Scribes, founded by Grand Duke Ivan III of Moscow, opened its Chorus of Young Singers. During the reign of Peter the Great, it was reorganized in 1701 and moved to St. Petersburg in 1703. The ensemble’s history has been closely tied to St. Petersburg ever since. In 1922 the Choral Technical College was established, which developed into an independent educational institution, as of 1955 the Glinka Choir School

_._]

BD: Similar to the Vienna Boys Choir?

Bychkov: Yes. What is interesting about the School, and quite unique, is that one studies there for ten years, both academic and musical subjects mixed together, and the degree of difficulty grows as time goes by. There is a tremendous competition to be accepted. In 1960, when I was entering, there were 500 kids being auditioned, and only twenty of us were lucky, and ten years later only thirteen graduated.

BD: So once you get into the school, there’s still a weeding out process?

Bychkov: Yes. One studies piano, sings in the chorus, studies harmony, gets solfège training, learns musical literature, all those things, as well as choral conducting.

BD: Are they training to become choral conductors?

Bychkov: Yes. That is not to say there haven’t been exceptions. For example, Vladamir Atlantov, the tenor of the Bolshoi Theater, was studying there in his time. But, generally speaking, usually those who emerged go on to continue their studies at the conservatory as choral conductors. That is the usual route. In my case it was different, because since I was twelve or thirteen, I was already interested in orchestral and operatic music, not just choral works. So, I made that transition much sooner than would have been expected.

BD: Did you get interested because of going to performances, or listening to recordings?

BD: Did you get interested because of going to performances, or listening to recordings?

Bychkov: Both. Just being with that music.

BD: What grabbed you?

Bychkov: The music! The power of it, and the infinite possibilities of instrumental music, the orchestral music literature.

BD: Is there any chance that the amount of literature is just too vast to take in, because so much has been written in the last 300 years?

Bychkov: Yes. A great deal of it is known to us because it’s something we grow up with. That is not to say that truly there is such a huge body of music, and one cannot know it all, but there is a basis on which the knowledge is being built. That includes people from Bach to Haydn, Beethoven, Mozart, and onwards. Then you can discover things. There is so much music that I cannot say I know it all, but I would very much like to learn a great deal. I just don’t have the time and the chance, which makes it very interesting and fascinating, because there’s always more music that one would like to do than the actual physical ability of a person to do it. [Both laugh]

BD: Are you making time in your career to explore a few new scores every year?

Bychkov: Absolutely, all the time.

BD: How do you decide which ones you will select, and which one’s you’ll postpone, and which ones you’ll never get to?

Bychkov: I rarely say never, only in the case of the pieces that I really feel ought not to be played.

BD: Why not?

Bychkov: Because I just don’t feel that they’re good. That’s a value judgment.

BD: This is what I’m digging for. What makes it good?

Bychkov: Many things make it good. One is the emotional content of the piece, and what it represents to me as a musician. Before I take it to the audience, I have to have a deep feeling for it, and a deep commitment. It has to speak to me directly. Secondly, the mastery of that composition, which is also a very important. It’s not good enough just to have a nice tune and nothing else. That won’t make a piece for me, personally. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why music of Rimsky-Korsakov, Glazunov, and people like that, does not really interest me. I feel that they had a tremendous melodic gift, but a lack of ability to develop those beautiful melodies that they would write. They would always end up repeating themselves, and for me that’s really not interesting.

BD: Repeating within the piece, or from piece to piece?

Bychkov: Within the piece, and very much from piece to piece, as well. I’m making a value judgment on their music, because they were still great masters. I’m just saying that I do not have an interest in their music. But there are other pieces that I would make a value judgment, and say I simply don’t want to perform because I don’t think that it’s good music. Then there are pieces that I feel ought to be performed, but I’m personally not really interested in because for some one reason or another they don’t speak to me today. It may change in a month, or in twenty years, and then I will perform them. There are many reasons that go into deciding what to perform and what to put into the program. Some of them are logistical, and some of them have to do with the fact that some pieces that I have... not admiration, but a great awe for, take time to mature. That’s been the case, for example, with Mahler’s First Symphony. I’ve been studying it and living with it for twenty years, and have not performed it until a year ago. This is because the first movement was a great, great, great, great challenge for me, and a great puzzle. I wasn’t quite sure what to do with it, and finally I simply felt enough conviction about the way to do it. It may change later on, but it took that time, so finally I performed it.

BD: So before you present a piece, you must be convinced that your way of presenting is the best way?

Bychkov: Not necessarily the best way, but that I have something to say, that hopefully will be convincing enough to do justice to the music, and make people sit up and listen.

BD: You studied in Leningrad. What was your first conducting assignment there?

Bychkov: I was first conducting when I was in the Glinka School, for the choir there, and then while at the conservatory, I also had my choir in one of the universities, which was a very valuable experience. I was not even eighteen years old, and I had a group which was mine, and we could make music. I had to plan for it, administer it, and do all the things that one needs to do being a conductor.

BD: Isn’t that an awful lot of responsibility to place on very young shoulders?Bychkov: It was a tremendous responsibility, but it was a great joy. I had tremendous support of the group because I started out as the accompanist, and literally several weeks later, the conductor of the choir was forced to resign. He couldn’t get along with them, and during that time I already had had several sectional rehearsals with them. So, they already had a chance to work with me, so they simply asked the administration to appoint me as their conductor. All of them were older than I was — still young people, mostly students, but older — and at that age that makes a difference. There I was telling them how to sing. They were amateurs, not professional musicians, but still it was really a remarkable experience, and I benefited from it a great deal. In the conservatory, student conductors do get to conduct symphonic performances, and operas as well, which is marvelous. In the opera house which is part of the conservatory, you have a professional orchestra in the pit, and you have some professional singers on the staff, and some students.

BD: Isn’t that an awful lot of responsibility to place on very young shoulders?Bychkov: It was a tremendous responsibility, but it was a great joy. I had tremendous support of the group because I started out as the accompanist, and literally several weeks later, the conductor of the choir was forced to resign. He couldn’t get along with them, and during that time I already had had several sectional rehearsals with them. So, they already had a chance to work with me, so they simply asked the administration to appoint me as their conductor. All of them were older than I was — still young people, mostly students, but older — and at that age that makes a difference. There I was telling them how to sing. They were amateurs, not professional musicians, but still it was really a remarkable experience, and I benefited from it a great deal. In the conservatory, student conductors do get to conduct symphonic performances, and operas as well, which is marvelous. In the opera house which is part of the conservatory, you have a professional orchestra in the pit, and you have some professional singers on the staff, and some students.

BD: Do you start it from the beginning, and not just conduct the last rehearsal or two?

Bychkov: Normally you don’t do a new production, but an ongoing production. For example, one season I conducted twenty performances of Eugene Onegin. That was a tremendous experience. [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my interviews with Dmitri Hvorostovsky, and Neil Shicoff.]

BD: But that was assigned to you. You were told you must conduct this, rather than whatever you like?

Bychkov: I was basically asked what it was that I would like to do, but without any guarantee that I would get to do it. I asked for Onegin because it was something that was extremely important to me, and they said okay.

BD: But if you had asked to do The Enchantress or Voyevoda, it probably would not have been done?

Bychkov: No, it would have had to be an ongoing production. They had a number of ongoing productions every season, and one of those I would get to conduct. So, that particular year it was Onegin. It’s a very good way of doing it, because study is very important, but part of the study is actually doing it. So, there was a good proportion.

BD: Is there any way really to prepare to do it, or do you have to plunge in and start doing it and learn from experience?

Bychkov: You do have to prepare, and you have to taught. These people who say that conducting cannot be taught, that one has to be a born conductor, don’t quite understand conducting. It’s not surprising, because conducting is still the youngest performing profession as we know. It hadn’t really developed as an occupation until the middle of the Nineteenth century. There is still a great deal of mystique about what makes a conductor, and what makes musicians follow one conductor and not another. So, because of that mystique, people say one has to be a born conductor, that it cannot be taught. That’s not really true. In a certain sense, it takes quality of character to be a conductor, just the same as it is to be a leader of any group. But in a purely technical aspect of leading a performance, conducting requires technique, no less than playing an instrument, because a symphony orchestra is an instrument.

BD: And you’re playing it?

Bychkov: You’re playing it, in a sense, because you are involved in the sound. But you’re invoking the sound with the gestures, and those gestures have to be eloquent enough to convey not only the basic aspects of a performance

—the tempo, the dynamics and things like — but also the character of a performance. That character will vary greatly from orchestra to orchestra, from performance to performance, and so one needs to be able to express it silently.

BD: How much of your work is done in the rehearsal, and how much inspiration do you leave for that night of performance?

BD: How much of your work is done in the rehearsal, and how much inspiration do you leave for that night of performance?

Bychkov: Inspiration is something that I don’t really count on, because we don’t really know what inspiration is. I suppose one way to describe inspiration is a particular state of mind and heart at a particular moment in the performance. You never know how it works, why in a particular performance you will feel something incredibly special, and in another performance you will feel a little bit flat. Sometimes you are very tired and it will be a very exciting performance, and sometimes you’re very fresh and it will be a very dull one where something won’t go right. One just doesn’t know how it is. Maybe inspiration is having that special feeling for wanting to make music, and ideas are coming suddenly on the spur of the moment that you have never thought of before. Maybe this is what inspiration is, but one cannot count on it because you never know if it will be there.

BD: Is it special when it does arrive? [_Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Renée Fleming, and Michael Schade._]

Bychkov: Yes, yes, it is, but it will never arrive unless there is a tremendous preparatory period, where first you’re alone with the music. Then, when you’re with the group rehearsing it, all things being equal, perhaps every once in a while, you will have something that is quite memorable to you, and hopefully to the audience.

BD: So everything in your working with the music, leads up to that performance

— the study, the rehearsal and everything?

Bychkov: Yes.

BD: You don’t get any joy just sitting at home reading a score?

Bychkov: Yes, I do, but that is not the main point of it. The main point, of course, is performing it, but only when you feel a hundred per cent convinced that you have something to say, and that this is the piece you absolutely must perform. There are some pieces that you feel ninety per cent about performing, but that last ten per cent may be missing, and then there is no point.

BD: Really??? Ninety per cent isn’t enough?

Bychkov: No, it’s not enough. For example, you might have a symphony that will have three movements which will be brilliant, and one of them that will be dull and really not up to the level of the rest of the piece. Then you have a very hard decision to make. Are you going to perform the piece in spite of that one movement, or you’re not going to perform it at all?

BD: Are there times when the three movements are of such inspirational value that you put aside that one movement?

Bychkov: Yes, and you try to find enough conviction to present the good side of the one that is not so strong, and try somehow to hide the weaknesses.

BD: Are those weaknesses in you, or are those weaknesses in the score?

Bychkov: Sometimes both, and sometimes either.

BD: Let’s come back to Leningrad again. When you were still there, what were your first professional engagements?

Bychkov: Those concerts with the choir that I had with the operas were professional engagements. I was actually paid for them. Then I won the Rachmaninov Conducting Competition while at the conservatory, and was invited to conduct the Leningrad Philharmonic, to make a debut with them.

BD: How can there be a conducting competition? How can you rate conductors?

Bychkov: The same way you can rate a pianist, a violinist, a singer

— by the quality of the music-making.

BD: [Gently protesting] But I would assume though that once you get up to that very top level, it’s very hard to distinguish between numbers one, two, and three, since every one in that group has attained that top level.

Bychkov: I don’t think that we were at that top level. We were studying. We were students. Some of us were more gifted, and others less. Some of us had more ability to persuade the orchestra to play what we wanted, and to make it a more convincing statement musically than others. This is not a satiation where you have a Karajan, a Kleiber, a Giulini, a Furtwängler, and you have to rate it.

BD: Looking at the other side of it, do you ever find a poor orchestral performer, and try to remove him or her?

Bychkov: That’s a very sensitive subject because you’re dealing with human lives there.

BD: Let me phrase it a little differently. As Music Director of the Buffalo Philharmonic [_shown below_], is it your responsibility to do a little weeding and cultivating of the orchestra?

Bychkov: Yes, it is my responsibility, however there is always a question. If the person is not performing as well as one expects him or her to, you really have to know the reason why. You have to understand that it takes time.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] So you’re part psychologist then?

Bychkov: Absolutely. In fact, a great deal of it is understanding human nature. Without sounding pompous, it is that people go through periods in life which are ups and downs. A musician is like everyone else, and all of that affects one’s work. Someone gets divorced, somebody gets married, somebody has a loss in the family, someone has a physical difficulty of one sort or another. All of that can affect the playing of a person. It might also be that somebody is just lazy, or has forgotten what is expected of what it takes to be a musician and to make music. Or, maybe someone simply cannot do it anymore. To make that kind of decision is very difficult, and you’re not always able to make the change because there are very strict rules and protections that exist for the musicians. In many ways it’s good, and it’s a result of abuses that happened in the past when people could literally be thrown out of the job because someone didn’t like the way they were dressed. Things like that have happened, and that’s why there’s protection today. On the other hand, sometimes it goes into an extreme where the person who really is unwilling, or, more often, unable to perform. It has been demonstrated, and the player is still protected, which I feel is also quite wrong. But I’ve noticed the most interesting thing is that most of the time, if one gives proper attention to a musician who has problems with the playing, it improves. The degree of improvement may vary, but it is extremely rare where you will attain no result at all. As I say, it’s a very complicated situation, and should always be addressed in every particular instance. One can never generalize about that.

BD: Coming back to the story, you won the Rachmaninov Competition. What did that lead to?

BD: Coming back to the story, you won the Rachmaninov Competition. What did that lead to?

Bychkov: I was invited to go and make a debut with the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, and I would have made it had it not been canceled a week before. After that I left.

BD: Did you leave because it was canceled, or was it canceled because you were leaving?

Bychkov: Officially it was not known that I was thinking of leaving, and I certainly hadn’t announced it, but I was never a believer in that system of government, and the lifestyle that people lead. Probably on a couple of occasions I said more than I should have under the circumstances, and that became known to the authorities. So, they decided that I was not

— as they put it — worthy of honor of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic. You must understand, though, that I was a kid. I was not a kid in my mind, but I was very young, just twenty years old.

BD: They thought you would be a trouble maker if they let you get started that way?

Bychkov: I don’t know exactly what they thought, but obviously they didn’t like the fact that I had independence of mind. In addition to that, being Jewish certainly didn’t help.

BD: Let me ask you one more question on this, and I will get off the subject completely. Was there never a thought in your mind that your immense talent, which you knew you had, could bring something special to those were living in this repressed society?

Bychkov: [Thinks a moment] Perhaps it is true, but before you decide whether you’re going to serve that particular society, you have to address the most basic things that one always has to do think about... for instance, what is the purpose of life? What is my mission in life? I’m not speaking about creating big revolutions, or attaining unbelievable world power. I’m speaking about every individual who has a certain purpose in life, and what that purpose is, and what one’s obligation to society is.

BD: Just how you live day to day?

Bychkov: How you live day to day. One of the basic things that one ought to have is a simple honesty with yourself, and a belief in what you’re saying and what you’re doing. I found that I couldn’t possibly abide by their dogmas, and a having a necessity to lie all the time while living there, because, basically, everything was based on a lie.

BD: There was not enough escape in the music?

Bychkov: Not really, because to be able to escape into music, and to have the musical opportunity that an artist has to have, there was a price to be paid. In addition to that, being Jewish was a double price to pay, because that would mean conforming to those political clichés and dogmas in which I had absolutely no faith. Life had always proven the opposite of what they were saying, and I just couldn’t face living with myself if I had to abide by that. So, that came first, and then came the idea of the question you just asked. Wouldn’t it be important to help the people living in the oppressive society? I’m afraid this has happened many times, and they have robbed themselves of great artistic talent in this century and in the past, with many people whom I admire tremendously, such as Baryshnikov, Rostropovich, and Solzhenitsyn. It is really their loss.

BD: Is your break so complete that if they invited you to come back for two weeks of concerts you would refuse?

Bychkov: No, I would not refuse. I would come back precisely because it would be something that I could give to the people. Making music would make me feel very special about it. Also, it is the country in which I was born, the culture which I have accumulated, the people with whom I studied, and who have given me so much to think about, and to whom I owe so much. For me it would be an honor to perform for them, but this is a different time we’re talking about

— the 1970s as opposed to late 1980s — and things have been changing there. It’s a very turbulent time in their history, and I’m very sympathetic to what some of them are trying to do. But still, I couldn’t possibly live in that society. I have to be free. I was very fortunate.

BD: When you came to the west, where did you go first? Bychkov: New York. I lived there for five years, and I went to the Mannes College of Music.

Bychkov: New York. I lived there for five years, and I went to the Mannes College of Music.

BD: Despite the fact that you had won the competition, and were on the verge of graduation, you decided to do more study?

Bychkov: Yes, because being a conductor is sort of a Catch-22 situation. You cannot prove yourself unless you’re given an orchestra, and no one will give you an orchestra unless they know who you are and are talented. So, how do you start when you come to a country where nobody has ever heard of you, and they have no idea who you are? I felt that the best way would be to go and spend a little time in an academic environment, just to learn and see how music is made here, and meet the musicians, and just become part of it in some way, even though it’s academic.

BD: Is there anything really surprising about the way we make music here?

Bychkov: In a positive and negative sense, yes, there were surprises. One of the great things

— which I expected, so I really shouldn’t call this a surprise — is that fact that people are free to express themselves. Musicians young, and not so young, have grown up with an idea that an artistic expression is basically an expression of a free will, an expression of talent in a free form. If someone doesn’t like it, it’s all right. We can all agree to disagree on something, but it is possible, and is encouraged. On the negative side, what I’ve noticed is that the system of musical education is very much lacking. Let’s say kids would go and study, take violin lessons and piano lessons. They would concentrate mostly on just that, and would obtain tremendous technical virtuosity with it, but really have very little else in a way of knowing more than just those skills.

BD: They’re technicians rather than musicians?

Bychkov: In many ways, yes, and I feel that is not really enough, because music is but one aspect of life. To be an artist, one needs to be exposed to various aspects, especially when one grows up, because it’s something that has to come in a combination of various things that one used to study, and think about, and read, and so forth. In a way, we produce lots of musicians, but very limited ones. Not all, but many. We have all the information we could possibly have, and all of it is accessible. So, someone who is really interested is always able to have it. But not all are so mature that when they grow up to know about that. That’s when I feel that a certain amount of guidance is very much necessary.

BD: This is guidance for performers?

Bychkov: For everyone, but performers particularly.

BD: Should the same kind of guidance be given to audiences?

Bychkov: Yes, absolutely, because there is sometimes a misunderstanding. People think that by going to a concert they’re going to an event of entertainment. Entertainment is something that you come to, and you possibly receive, and, if it’s good, you will enjoy yourself. Very often, people will come and say to me,

“Thank you so much. I really enjoyed myself tonight,” and I always want to ask them, “And what about the music?” [Both laugh]

BD: Is there a balance between the artistic achievement and an entertainment value?

Bychkov: That depends on what one understands by the word

‘entertainment’. What is entertaining? What does the word really mean?

BD: What does it mean to you?

Bychkov: Basically, it’s a way of amusement. It’s a way of resting and enjoying the situation. We all enjoyed being entertained, and it’s great, but art has to be more than just giving a good time to a person. It has to be a challenge. Often it has to be disturbing to a people who are receiving it. It has to make them think. It has to make them feel. It has to make them want to know more about it, and that’s not just entertainment. It goes much deeper than that.

Bychkov: Basically, it’s a way of amusement. It’s a way of resting and enjoying the situation. We all enjoyed being entertained, and it’s great, but art has to be more than just giving a good time to a person. It has to be a challenge. Often it has to be disturbing to a people who are receiving it. It has to make them think. It has to make them feel. It has to make them want to know more about it, and that’s not just entertainment. It goes much deeper than that.

BD: Then let me ask the big philosophical question. What is the purpose of music in society? [_Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Francisco Araiza._]

Bychkov: The purpose of not only music, but of all the arts, is to make people extra sensitive, extra aware of the world in which we live. It brings a special sense of beauty into one’s life which otherwise might be missing, because, in a peculiar way, it can serve as an escape from reality. Let’s say that you listen to a beautiful Mozart symphony. It is an absolutely miraculous piece of music in the way it sounds. If you have a very difficult life, or perhaps a very tragic life, and you hear this music, it is so wonderful and so noble that it makes you want to live. So, it can serve as that. On the other hand, it’s not so good sometimes for us to be too happy with our life, if we are too well off, and feel that we have too many things, and we’re just bored because we are part of the world and the world is not all happy, and not all wonderful. There are many people who do suffer this way, and it’s good to hear a Mahler symphony, and hear the anguish and suffering of another human being, because it makes us extra sensitive to that. Unless we are sensitive enough to others, we cannot expect that kind of sensitivity shown to us. So, the art of music, as does the art of literature or the visual arts, serve different kinds of purposes, but simply it contributes toward people being better human beings.

BD: Now we’re talking about so-called concert music. Is concert music for everyone?

Bychkov: Yes, of course! It’s not just for a few chosen ones.

BD: But it seems there are so many who don’t choose to make it part of their lives.

Bychkov: They cannot be forced. No one can, or should be, forced to take part in something that one is not interested in, but that doesn’t mean it is not for them. It is there for them to enjoy and to partake, but it is not something that they have to do. That I feel very strongly about. Some feel it’s kind of elitist, and that it should be for people who are refined enough to appreciate it. I don’t like that kind of reasoning because it’s absolutely wrong. Performers of a Mozart symphony, or a Bach fugue, or the St. Matthew Passion don’t know the difference between the people who will listen to that kind of music because, in the end, every human being will hear it and feel it very, very deeply. Some will choose to hear it and some won’t, but that should be left to them. The best we can do is to introduce people to it, and tell them it exists, and the earlier we do it in their lives, the more natural it is. It’s like foreign languages. When you grow up with various languages, it becomes something natural. When you have to study them later on, it becomes more difficult. It’s the same with classical music. One of the things which is troublesome in the classical music world today is that we are sometimes too routine. We make too many assembly-line productions of concerts that it is boring. Those people who feel very strongly about classical music in general will still come, and they will be there, but the ones who don’t may try once, but they won’t necessarily come back unless they are hooked on it. But to be hooked on something, there has to be an incredible sense of excitement, and special animation that emanates from the performance to make a person feel hooked, and want to experience it again and again.

BD: Whose responsibility is it to get them hooked

— the composer, the performer, the conductor, the audience?

Bychkov: It certainly is the responsibility of a performer. Not only conductors, but pianists, violinists, and so forth, because the music is there. Mozart has written his symphonies for the people, and so has Tchaikovsky and Brahms and Beethoven.

BD: Is this partly what you look for in the scores

— music that has a hook?

Bychkov: If it hooks me, then I would probably be able to communicate it with more or less success. But I have to have that feeling for that piece in order to perform it.

BD: As you’re emerging in your career, you’re conducting here in the United States, and you’re conducting in Europe. How do you divide your time between operas and concerts, and this orchestra and that orchestra? Bychkov: Most of my time goes to the orchestra with which I’m associated. For the moment it is Buffalo, and then as far as guest conducting is concerned, there is a limited time for that. I have to have enough time to study, and to think about the music, and experience life, in other words just to live. There are maybe four orchestras that I permanently guest conduct every year, and as far as opera is concerned, on the average I’m able to do one production a year, normally in the summer, in the festival environment. That’s how the time is divided.

Bychkov: Most of my time goes to the orchestra with which I’m associated. For the moment it is Buffalo, and then as far as guest conducting is concerned, there is a limited time for that. I have to have enough time to study, and to think about the music, and experience life, in other words just to live. There are maybe four orchestras that I permanently guest conduct every year, and as far as opera is concerned, on the average I’m able to do one production a year, normally in the summer, in the festival environment. That’s how the time is divided.

BD: In a couple of weeks, you’re going to be making your debut with the Chicago Symphony. Are you looking forward to that?

Bychkov: Yes, very much.

BD: Do the great orchestras of the world play better for you than lesser orchestras?

Bychkov: [Thinks a moment] It’s very difficult to answer it like that, because most of the orchestras that I conduct I’m lucky enough to have their good will, and good rapport. They always give me the best they are able to give at this particular moment. Some orchestras can give more, and some can give less, but they all want to give a lot. So, one is always grateful for the effort that is being put into it, even though they’re all very different. Really, one should not compare orchestras because the Chicago Symphony is truly one of the greatest orchestras in the world. I’m sure that you, living in Chicago and hearing them a lot, probably have heard a performance that would not have been of the quality you would expect. That could happen for many reasons, not because they didn’t want to, but maybe circumstances were not particularly good. Every orchestra goes through that. On the other hand, you will hear an orchestra that perhaps in name recognition, in the day-to-day quality by the musicians would not be of the level of the Chicago Symphony, but you would hear them and be absolutely bowled over by what happens on stage that particular day. So I find it always very unfair to make comparisons of the orchestras. The only thing one can talk about is that they’re all different in personalities. They have different traditions, different histories, different chemistry of players, a different history of conductors, different styles, and a different personality on stage.BD: Is the speed with which they can learn something perhaps a little different?

Bychkov: Yes.

BD: Some orchestras can do it well, but it takes five rehearsals, and others can do it in a half of a rehearsal?

Bychkov: Absolutely. It is very, very different. American and English musicians are incredibly fast, and the Concertgebouw actually is very slow by the standards of American and English. It takes them longer, but they go deeply into it. The Berlin Philharmonic is very quick, and French musicians are very quick, too. It really varies.

BD: When you conduct in Berlin, do you ever feel that you’re having to overcome some of the Karajan shaping, and then remold it in your image for each concert?

Bychkov: I never feel that I have to overcome anything there, no. They really are an incredible group of players who have a very definite point of view about the music that they have played. They know the music, and are open to the music they don’t know. They always want to know the reason why, and give all their beings into making music. It’s a way of living for them just to sit and make music, and so you don’t really have to overcome anything. If you do a Brahms symphony, or a Beethoven symphony, you are inevitably going to do it differently from what they’re used to, because they have played it so much with their Music Director and his predecessor. There are still people who played under Furtwängler, but they’re open. They’re not interested in just playing a recorded performance.

BD: This bring up another subject that I want to get into. When you’re making records, do you conduct differently for the microphone than you do for the live audience?

Bychkov: No.

BD: Not at all???

Bychkov: No, no. It’s a fantastic process to make a record, because in the back of your mind you know that you can always stop and repeat something. So, you don’t mind this mistake here or there. It really doesn’t matter. Also, you have a chance to hear it back. It’s like looking at yourself in the mirror. All you have to do is open your eyes when you look in a mirror, or open your ears when you listen. However, sometimes that is a hard thing to do, because when you’re doing it at the moment you’re actually working, you’re listening to it in a different way than when you’re removed from it. Then, two months later you’re going to hear the tempo, and it will not feel the same as it did when you were doing it. You go through various stages of acceptance and rejection, but it is really no different. What I don’t like from records is when they are made in a very clinical way. They have no mistakes, and things are absolutely perfect. All the notes are played, but you don’t feel there is a spirit in the music-making that makes you sit up and listen. It’s something that you look for in a live performance, otherwise you will be bored, and you should be able to get the same thing in a recorded performance.

Bychkov: No, no. It’s a fantastic process to make a record, because in the back of your mind you know that you can always stop and repeat something. So, you don’t mind this mistake here or there. It really doesn’t matter. Also, you have a chance to hear it back. It’s like looking at yourself in the mirror. All you have to do is open your eyes when you look in a mirror, or open your ears when you listen. However, sometimes that is a hard thing to do, because when you’re doing it at the moment you’re actually working, you’re listening to it in a different way than when you’re removed from it. Then, two months later you’re going to hear the tempo, and it will not feel the same as it did when you were doing it. You go through various stages of acceptance and rejection, but it is really no different. What I don’t like from records is when they are made in a very clinical way. They have no mistakes, and things are absolutely perfect. All the notes are played, but you don’t feel there is a spirit in the music-making that makes you sit up and listen. It’s something that you look for in a live performance, otherwise you will be bored, and you should be able to get the same thing in a recorded performance.

BD: Then when you make a recording, do you try for this sweep? [_Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Felicity Palmer(Klytämnestra), and Graham Clark (Aegisth)._]

Bychkov: Yes, yes.

BD: Can you always make it?

Bychkov: Not always, depending how successful you are. It can come if you have enough patience. Sometimes you start the session and things are going slowly. It takes time to warm up and get it, but eventually it is going to happen. Eventually you’re going to be totally warm. You’re going to feel totally at ease. You’re going to do it, and you will feel that adrenaline that will enable you to do it as if you’re doing in a live performance. The important thing is to have a producer who will know exactly what you’re trying to do, who will tell you where you’ve missed something. You also have to listen very carefully to see which points need correction.

BD: Then you go back and re-make those details?

Bychkov: Then you go back, and re-make the details again, and you try to make them in the context of the big sweep.

BD: Is there any chance that you’re making things too technically-perfect, even in a recording that has this sweep to it? Are you setting up an impossible standard?

Bychkov: It may be an impossible standard for the critics, because you will find them going to a live performance expecting the kind of technical perfection that they hear when they listen to a recording. I don’t feel that live performances need to be judged on the basis of a total technical efficiency. So what if someone has accidentally played a wrong note, or someone cracked a note, or if one particular spot was not one hundred per cent together? We’re all human beings. This is really not important. I would be perfectly happy to accept that if the performance itself had something special to say, rather than a technically clinical performance that will be absolutely a hundred per cent together with no mistakes and no slips, and be very dull.

BD: And yet the record producer cannot accept that technical flaw!

Bychkov: Nor should they, because in a recording situation, you have an opportunity to repeat something and get it right, and you should. The live performance is a momentous event. It’s a single occasion. It happens, and like time, it will never come back. It’s there for the performance, but a recording is something that is there to stay. There is no reason why a painter would leave a painting with a blemish. He will work until he finally feels that he has done everything that he could, and then he will put it out for observation. That painting is there to stay. Why should a record be different? But it doesn’t mean that it can, or should be devoid of spontaneity and excitement that a live performance can give you.

BD: You’re perfectly willing to accept a blemish or two in the live performance?

Bychkov: [Laughs] Really, there is nothing I can do about it. I have to accept it, because if every time there is a little blemish I would get terribly flustered and upset, I won’t be able to perform because that’s terribly destructive. It’s a negative feeling, and you cannot make music by feeling negatively about yourself, or the performance, or the musicians you’re making it with.

BD: Are there ever performances that are just perfect? Everything works, and it’s all there, and everything’s just right? Bychkov: Every once in a long while you are lucky that somehow all the components happen, and then you feel absolutely incredible. Those are the memorable ones. That is not to say that if things are going wrong in the performance, you’re not going to be a hundred per cent happy. You’re going try to do it better next time, and what can happen is that a particular point of difficulty that one had will be overcome... but something else might go wrong. It’s not really the thing on which one needs to base one’s acceptance or lack of it about the performance. It’s something that we constantly work on, and no one is happy. Do you think a horn player is happy when he cracks a note in an important solo? He’s miserable there. But if he will allow himself to be so depressed that nothing else will matter to him, he’s going to crack the next note, and the note after that, and it’s going to be a complete disaster. He has to recover, and just feel okay. So what? It’s all right. It happens to everyone.

Bychkov: Every once in a long while you are lucky that somehow all the components happen, and then you feel absolutely incredible. Those are the memorable ones. That is not to say that if things are going wrong in the performance, you’re not going to be a hundred per cent happy. You’re going try to do it better next time, and what can happen is that a particular point of difficulty that one had will be overcome... but something else might go wrong. It’s not really the thing on which one needs to base one’s acceptance or lack of it about the performance. It’s something that we constantly work on, and no one is happy. Do you think a horn player is happy when he cracks a note in an important solo? He’s miserable there. But if he will allow himself to be so depressed that nothing else will matter to him, he’s going to crack the next note, and the note after that, and it’s going to be a complete disaster. He has to recover, and just feel okay. So what? It’s all right. It happens to everyone.

BD: [Laughs] Let’s hope it is not at the beginning of Till Eulenspiegel!

Bychkov: Even if it’s the beginning of Till Eulenspiegel! Imagine how many notes these people have to play later.

BD: I would assume it’s easier to make a mistake in a concerted passage, or something that’s very deep down that won’t be noticed, than a big exposed solo.

Bychkov: That’s true. No one likes to do it, but everyone is human, and the best of musicians have these kinds of slips. So what?

BD: Is the music human, or is the music more super-human?

Bychkov: What do you mean by super-human?

BD: If you’re doing an acknowledged masterpiece, is there something about this music that transcends all human failings?

Bychkov: Yes, definitely! One of the greatest puzzles is the fact that I don’t think anyone can rationally explain how it is possible for someone like Bach, or Mozart, or Brahms, to create a great masterpiece out of nothing. No one can explain how in someone’s mind will be conceived Don Giovanni, because before they write it, they have to hear it in their mind, and then they put it on paper, which is a technical process. But that initial point where they actually hear this music in their mind, how is it possible? No one can explain that. You can call it anything you like. For me it’s divine by nature.

BD: Are you saying that the compositional process is more transcription than creation?

Bychkov: No, it is creation. What I’m saying is that when you hear something in your mind, and then you put it on paper, that’s a technical process. But when you hear it your mind, that’s a creative process, and we don’t know why someone will be able to hear it when others can’t.

BD: [Gently pressing the point] Is it heard in the mind, or is it created on the paper to be heard all at once as it’s going and being re-shaped?

Bychkov: After that it is both, but initially, to write something on paper you have to hear it. Otherwise, you have nothing to write.

BD: When you’re presented with a score, is it your job to put these sounds back into the cosmos?

Bychkov: Yes.

BD: We’re talking about a few of the big masterpieces

— Mozart, Bach, and Brahms. Should it be that we only listen to these masterworks, or should we also listen to the next level, and the next level?

Bychkov: Yes, because it’s all a value judgement. I cannot say to another person that they should or should not listen to Sibelius or Rimsky-Korsakov, or others you can name. There is someone who will absolutely love a piece of music written by a composer that perhaps most people have never heard of. But that’s wonderful if there is one person to whom this piece of music gives a great joy. So much the better, and the more we know, the more we discover. There should never be a limit just to what we call accepted masterpieces. Besides, there is so much music that Mozart has written that most people don’t know because it’s not performed. We don’t realize the wealth that is Haydn, for example.

BD: You’re working in Buffalo, which has a rich tradition of new music. Not talking about a specific piece, but are there works being written today, or very recently, that are on the level of Bach, Mozart, or Brahms?

Bychkov: Again, this is a value judgement, and a very personal point of view. Music written by Shostakovich, for me is as important as Brahms, Beethoven, and Bach. There are not many more of the composers of our time that I could say that about, but one ought to be open enough to understand that it really takes time. One needs to have the time and the perspective to look at it before deciding on that. If I listen to music of Luciano Berio, that it is something absolutely incredible, really great, interesting, and quite magnificent. And, if I don’t understand it completely right away, I still feel that there is something there that I simply have to take time to know, and that’s what I do, in fact. That applies to many others like, Lutosławski, and Boulez, and Dutilleux, and Henze.

Bychkov: Again, this is a value judgement, and a very personal point of view. Music written by Shostakovich, for me is as important as Brahms, Beethoven, and Bach. There are not many more of the composers of our time that I could say that about, but one ought to be open enough to understand that it really takes time. One needs to have the time and the perspective to look at it before deciding on that. If I listen to music of Luciano Berio, that it is something absolutely incredible, really great, interesting, and quite magnificent. And, if I don’t understand it completely right away, I still feel that there is something there that I simply have to take time to know, and that’s what I do, in fact. That applies to many others like, Lutosławski, and Boulez, and Dutilleux, and Henze.

BD: Are there any Americans in there?

Bychkov: Yes, of course there are many American composers that are very interesting. Elliott Carter, for example, is universally acknowledged as a very difficult composer, so I wouldn’t make a judgement on his music. I have not performed it, so I don’t know it well enough to really say very much about it. But there are very talented people like John Adams and Corigliano. I like Barber’s music very much. Somebody might say, “Ah, it’s nothing new. It’s so traditional. It’s so classical.” Well, okay, but I still find it very beautiful.

BD: By the same token, will you perform Shostakovich over, say, Schnittke?

Bychkov: I will perform Schnittke, too, but I don’t think that I have the right, or anybody has the right, to say it’s interesting and it’s good, but it’s not on the level of Brahms, Beethoven, and so forth. It’s very easy to say that because we’ve had the benefit of living with music of Beethoven and Mozart and Bach for such a long time. We haven’t had the time with music of Boulez, and Messiaen, and Berio. I’m curious what people will say in a hundred years about these composers living today, and how they would acknowledge them compared to the masters of the Nineteenth century and early Twentieth century. I’m very curious about that.

BD: We’re always fifty years behind in our perspective?

Bychkov: We’re behind, but it is the responsibility of performers to be able to distinguish the music that is written today that is valid, that has to be performed, and the music that is not valid, that need not to be performed. There is as much music written today, as there was a hundred years ago, and one cannot perform it all. There is music that has to be performed, and some which is no good, and really doesn’t need to be performed.

BD: Should every piece of music at least get that one chance?

Bychkov: I don’t really know. I don’t know the answer. I cannot personally do it for simply human limitations. But the point is that whenever we perform music of today, the important thing is not to do it just because it’s expected. It must be something that one feels one needs to do because it’s important. But when you do it, it’s not to please a critic, or another composer, or people who always praise new things. It’s because you actually believe in this music. What I’m saying is that there is so much written that it is actually difficult to know which one to concentrate on, because you cannot possibly look through all these scores and decide. One is lucky to have help from other musicians who would know, and I will speak to someone whom I admire tremendously, who has played the greatest contemporary music, and has a tremendous experience. That person will say to me, “You really ought to look at this piece of Kagel, or Berio, and so forth, but don’t waste your time with (something else) because it’s really not gratifying in the end.

” At least you should get a certain amount of guidance, and then you decide for yourself.

BD: What advice do you have for composers who are coming along today who want to write orchestral music?

Bychkov: I don’t think that I have the right to give any advice. [BD is very surprised] Really I don’t, because I cannot tell them how to write, and what to write. I would never presume to do that because I’m not able to compose music myself.

BD: Would you give them encouragement?

Bychkov: Encouragement??? I don’t think they need encouragement coming from me. That would be silly. They will write anyway, because if they have the inner necessity to express themselves through musical composition, they will do it regardless of whether someone will tell them to or not to. There is no one who has the right to tell them don’t do it, because none of us are the guardians. They need to hear from us, “Yes, you should compose!” What they would probably be happy about is if you said to them, “Yes, you write, and I will perform it!” That is a very important thing for a composer, especially for a young composer, to hear from a performer. So, those of us who know a particular composer, who believe in his or her music, I can say that, and that is the best thing we can do for them.

BD: I’m hoping that maybe ten or fifteen years down the line, you will find some composer that you really like, and you’ll start championing his or her music, playing it regularly and taking it with you.

Bychkov: I’m looking at it right now, as a matter of fact, and I’m going to do that.

BD: Can I ask who it is, or is it too early?

Bychkov: It’s too early.

BD: What advice do you have for young conductors?

Bychkov: [Thinks again] I don’t feel very well about giving advice to other people, in the sense that different people need different kinds of advice. There is nothing that is universally good that I feel I should say that would not sound pompous and condescending. I would say what I say to every musician, or every person who wants to apply himself to something, simply to do it honestly, and with total commitment. Not to do it half-way, and try to realize if it’s something that the person has a special talent for. Sometimes that is a very difficult thing, because being obsessed about something and having a special talent to do it is not the same thing. It’s very difficult for a person to know which is which, but that’s not something I could give advice on. Each person should decide for himself.

Bychkov: [Thinks again] I don’t feel very well about giving advice to other people, in the sense that different people need different kinds of advice. There is nothing that is universally good that I feel I should say that would not sound pompous and condescending. I would say what I say to every musician, or every person who wants to apply himself to something, simply to do it honestly, and with total commitment. Not to do it half-way, and try to realize if it’s something that the person has a special talent for. Sometimes that is a very difficult thing, because being obsessed about something and having a special talent to do it is not the same thing. It’s very difficult for a person to know which is which, but that’s not something I could give advice on. Each person should decide for himself.

BD: Tell me the particular joys and sorrows of working in the opera house. In the symphony, you have the eighty-five or a hundred players to mold, and in the opera house, there are singers on stage, and so many more variables. Tell me some of the pluses and minuses of them.

Bychkov: It’s much more complicated in opera precisely because of all the variables and all the ingredients involved. You have so many more people to deal with, who express themselves. So, it is much more difficult to arrive at a unified artistic statement in an opera. However, the power of operatic music, and the beauty of the human voice is such that when it works well, then it is the most beautiful uplifting experience one can have. When it doesn’t, it’s the most miserable one, so one always needs to be careful. [Both laugh]

BD: Can I assume that you don’t have either the very top or the very bottom most of the time? That most of the time it’s a gray area?

Bychkov: Well... I’m afraid with opera it probably is top or bottom. Maybe for other people it is different, but for me, if I’m not working with a company where the voices are beautiful, or the acting ability is not equally strong, and not all of my colleagues have something very special to say about the roles they are singing, or maybe the rehearsal time too short, or the production is one that I don’t like and don’t enjoy, then I’m miserable, because whatever idea I might have about this piece of music is not going to be realized. Also, if I’m not able to receive from my colleagues very strong ideas of their own, then again it’s not going to work, and you are into a protracted period of being very unhappy. On the other hand, if you have a strong company, and strong artists with strong views

— however strong doesn’t matter, but the stronger the better — and you have good conditions with a lot of rehearsal time, and you can find a way that works for all, then it’s magnificent.

BD: I hope the Don Giovanni here is on the magnificent side.

Bychkov: It’s one of those, yes!

BD: You take great care to make sure that the voices can be heard, and keep the orchestra down and not cover them?

Bychkov: Yes. Well, it depends. One always needs to know exactly where one needs to take extra care. The musicians in the pit should play with awareness of the singers, provided they’re not seated in a very bad location. But generally speaking, if they’re able to hear the stage, then it’s going to be fine for the audience.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You expect the back stand violists and the double bass players to hear the singers?

Bychkov: Unless they’re covered by stage, or something like that. But in decent conditions, they ought to be able to hear. The other thing is that you have to know the orchestral texture

— where it is going to cover singers, and where it will not. You can have a tremendous brass section playing with unbelievable power and not cover a human voice on stage. Then, in a particular place in a particular tempo in a particular sonic environment, you can have several string players completely cover the human voice.

BD: I would think that standing in front of the orchestra would be the worst position to judge the balances.

Bychkov: Sometimes that is so, yes, it can be.

BD: Do you occasionally have a deputy conductor so you can go out in the house, or a deputy listener?

Bychkov: I will have usually a deputy listener who will come and say, “Here, it’s a bit loud, and here it’s not enough.” I very much rely on that. Also, if I’m lucky, I have a chance to hear other performances in that particular house to know what works there and how, generally speaking, the orchestra sounds. Then I know what’s beneficial for the stage.

BD: Have you recorded any operas, or just symphonies?

Bychkov: So far, symphonies. There will be opera projects.

BD: Do you enjoy making records?

Bychkov: Yes, tremendously. I enjoy less listening to them after they’re made because there is nothing I can do about it once it’s done. But the process of doing it, I enjoy very much.

Bychkov: Yes, tremendously. I enjoy less listening to them after they’re made because there is nothing I can do about it once it’s done. But the process of doing it, I enjoy very much.

BD: Is there any feeling that twenty years down the line, you’re going to be embarrassed by one of these records you’re making now or have made already?

Bychkov: I know that there will be, and it will probably not take twenty years. [Laughs] It will probably be much sooner than that, but this is a fact of life that a musician has to live with, and the only alternative is not to make any records. But I enjoy making them enough to push that other thought to the back of my mind. I know that what I do today represents what I think about this piece today, and I do it honestly. I don’t just go to the studio, open the score and start recording it. To the best of my ability I do it, and as I will change, my concept of the piece will change with time. Sometimes it will be some small details that only I will know about, and sometimes it will be in a significant way. But I’m still young enough that when the time comes, I’ll be able to re-record it, and then it will a statement of what I feel with that particular piece at that particular moment, which may be quite different from what it is today. It’s good to have these different things because we’re never the same, and the music will not be the same.

BD: Do you subscribe to Georg Solti’s theory that every conductor should record things three times

— once when they’re young, once in their middle-age, and once when they’re old?

Bychkov: Yes and no. First of all, I’m not quite sure where one can define the middle period and the old age.

BD: Perhaps if you recorded things with fifteen or twenty year gaps. [_Example shown at left_]

Bychkov: Yes, of course, then that will represent a musician at that particular moment in one’s life. In that sense, it’s very true. Interestingly enough, some musicians have done that, and when we will listen to them, sometimes we like the performance that happened earlier more than the later one.

BD: Does this mean he hasn’t learned anything over those years?

Bychkov: Oh, no, it has nothing to do with that. Maybe on that particular day he had a flu and a very high temperature, and wasn’t feeling well. It is possible. We are all human. It could be that he’s no longer as deeply attached to that music, or maybe he performed it too much and it’s stopped being as fresh as it was once before. We don’t know these things, but it happens like that.

BD: Is there any competition amongst conductors?

Bychkov: In a real sense, I don’t think there is a competition, but some people feel that they’re competing against others. Then they feel there is competition, so there is competition, but objectively speaking, no there isn’t really any competition. How can there be? There are so many orchestras. There are so many concerts, and today this person conducts and tomorrow another person conducts, and the day after that the orchestra will be looking for a Music Director. These two people cannot compete because no matter what they do, the musicians will enjoy a concert with one person more than with the other, and then nobody can do anything about that. The audience could be more receptive to that, and so it goes. There is a place for many people in the same field, and there are many people who can contribute something very valuable to it. The ones that I admire most are the ones who don’t give one thought to a competition, but really concentrate on the music, and have something special to say with the music-making that they do. I would be very happy to hear a Brahms symphony with Carlos Kleiber tonight, and Giulini tomorrow, and just pray that perhaps one day I can understand that piece as well as they do.

BD: But are you just as happy to hear that Brahms symphony by unknown conductor X today, and unknown conductor Y tomorrow?

Bychkov: Absolutely! I would be ecstatic if I hear someone who will say something to me in that piece that will touch me deeply, even if I haven’t heard the person before. It doesn’t really matter. It makes no difference.

BD: If something touches you deeply, do you then incorporate that idea into your own interpretation?

Bychkov: It will make me think, and someway it will find a place, yes. Or maybe I will find a performance extremely interesting, and perhaps I will disagree with it, but I will still find it interesting and full of ideas. Maybe I will reject it, but it doesn’t matter. It will stimulate me, it will challenge me, and I will be grateful for that.

BD: Is conducting fun?

Bychkov: It depends on the music, on the conditions, how you feel, how the orchestra is playing, and how the singers are singing. Let’s say you do a Slavonic Dance of Dvořák. That has nothing but sheer joy in it. It’s fun when it sounds beautiful, but you cannot say it’s fun when you’re working on it because it is extremely difficult. It is extremely challenging, and you go through many doubts, and have very many questions that need to be answered. Eventually, if you’re lucky, you can arrive at a point where you have fun, but what’s important is that if it’s the kind of music that is supposed to give fun to the audience, that they actually get it.

BD: You are willing to forego your own fun if the audience has its own fun?

Bychkov: If they have fun, you will have it, too. They won’t have it unless you do, but it has to be so well done, and feel so well and so right. That will apply to music of that kind for sure.

BD: You are about to leave your position in Buffalo?

Bychkov: Yes, I’m leaving the orchestra at the end of this season to be with the Orchestre de Paris.

BD: You’ll be Music Director there?

Bychkov: Yes.

Bychkov: Yes.

BD: There are rumors that you’re in line for Karajan’s job when he steps down. Is that something that appeals to you?

Bychkov: First of all, it’s not something that one can say it appeals to me. Also, there is no line for Karajan’s job. People in the press make it a line, but there is no such thing as line. Karajan is still alive, thank God, and I always find it very distasteful to have people discussing that situation as if he was already dead. I find it really in a very poor taste. I was reading an article the other day in one of the newspapers, and the person was writing about the situation in the orchestral world today, and how people move from one place to the next. Then he said something to the effect that, “Sooner or later, Mr. Karajan is not going to be there anymore.” I just don’t understand why someone would do that.

BD: I guess people are just facing the reality, because there will be a time when he’s not around, and yet we don’t want him to leave soon.

Bychkov: What do you mean when you say ‘we’?

BD: No one in the musical world wants him to leave soon.

Bychkov: Oh, I wouldn’t agree with you on that.

BD: [Shocked] Really???

Bychkov: I read and hear many people who cannot wait for him to leave, and that hurts a great deal because he has given so much to the world of music.

BD: Then let me rephrase it. Those of us who are enlightened are not waiting for him to leave. There’s a reality that it might be twenty years down the line, but eventually there will be a time when he’s no longer there, and it will be very sad, but we have to go on.

Bychkov: Yes, but it doesn’t mean that we have to speculate about it. Really, there is no line.

BD: The situation here in Chicago is a little different, because Solti has said he is going to leave in two years. He’ll stay through ’91.

Bychkov: Then that it different. Karajan didn’t say that he’s going to step down. He’s there, and he’s their Music Director. Why discuss what will happen after he leaves the orchestra? I don’t think that really contributes anything. Besides, nobody knows. The decision will be resting with the orchestra, and with the government of West Berlin. Whichever way they will go, I’m sure they will uphold the great tradition that they have had. They have had very few music directors, and they’ve been lucky with every single one of them. They know that they have this responsibility, and when the time comes, they will make that decision. I really prefer not to speculate about that, and I certainly am not in any way in contention, or in desire, or anything like that. I’m very happy with the relationship I have with that orchestra. I conduct them regularly, and I record with them regularly, and I have toured with them.

BD: That’s almost the ideal situation.

Bychkov: In a sense, yes, because I make music with them, and that is a great joy for me.

BD: Yet you don’t have the artistic administrative responsibilities which can be headaches.

Bychkov: But I have another orchestra with which I do have those responsibilities which are headaches, but I enjoy at the same time with the price to be paid. So I’m very happy with that.

BD: You mentioned that the orchestra has a choice. Is it right that the orchestra musicians have a say-so in who will be the permanent conductor?

Bychkov: Yes. In fact, in every orchestra they do. It’s very rare you will find an orchestra where musicians are totally opposed to someone, yet that person would be appointed. It’s very rare because, let’s face it, we all have to make music together, and I wouldn’t want to go to the orchestra where I’m opposed by the orchestra as a group. I may be opposed by several people, and that’s perfectly normal. But as a group? I wouldn’t be interested.

BD: Do they have veto power?

BD: Do they have veto power?

Bychkov: I don’t know if they have a veto power in Berlin, but the point is that even if you don’t go into the legalities of a veto, or lack of it, if the opposition is tremendous and emanates from the orchestra as a body, then no one would have the stupidity to impose that conductor on an orchestra.

BD: What if the orchestra would rather have so-and-so, but they’ll put up with this other guy? Even though they’re not opposed to it, it’s a lukewarm approval.

Bychkov: Yes, it might be like that. These situations are possible, and one never knows. Those who do know don’t talk, and the ones who talk usually don’t know. [Both laugh]

BD: You’re going to the Orchestre de Paris. Is there really a French orchestral sound?

Bychkov: Yes, there is such a thing.

BD: Are you going to keep that French sound while conducting Mozart and Rimsky-Korsakov?

Bychkov: Yes, depending on the repertoire.

BD: Will you wind up having to play a lot of Debussy and Ravel?

Bychkov: Thank God for that. [Laughs] But I must say, in the case of that particular orchestra, Barenboim has been their Music Director for twelve or thirteen years now, and has developed a tremendous range of repertoire and style of playing. It is really incredible. For example, when they play Bruckner, it sounds very Germanic. Then when they play Debussy or Berlioz, it will sound as French as it can ever be. It’s that versatility that I very much appreciate, because there is no point in trying to play music that will sound very foreign. One tries to find the sound that will be authentic, that will be right, and it will still sound different, and that’s good. But it will still sound different because the artistic temperaments and personalities reflect the national origins.

BD: When you play Debussy and Ravel in Paris, do you learn a little bit about the French sound and transfer that when you’re in Berlin, or Buffalo, or when you guest conduct elsewhere?

Bychkov: Yes, I try in some ways. You are never one thousand per cent successful unless it’s your orchestra with which you are associated, and you permanently address the challenges that you face. But when you guest conduct, you cannot adjust it in the course of two or three days. You should not even change the basic sound of the orchestra. But within that, you have to impress the musicians with the necessity of playing it in the way that will feel is right, and if you play Ravel or Debussy, it should not sound as Brahms. It just would sound bad.

BD: Thank you for spending this time with me today, and thank you for coming to Chicago. I hope you will come back in future seasons.

Bychkov: Thank you very much. You’re very kind. I hope so, too.

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 28, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1992, 1999, and 2000; and on WNUR in 2004. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.