Renée Fleming Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . .

Soprano Renée Fleming

An Early Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Renée Fleming, one of the best-loved and versatile sopranos of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, has been described as "the people's diva," and perhaps comes closer than any other singer of her time to being an old-fashioned operatic superstar. Her wise repertoire decisions have allowed her to embrace a wide variety of works throughout her career, including Baroque opera, Mozart, the Italian bel canto repertoire, Verdi, Massenet, Puccini, Richard Strauss, a number of contemporary operas, and songs from all eras. Her voice is notable for its fullness, warmth, its creamy tone quality, and her ability to spin out long, velvety, legato lines. She is known for the intensity and integrity of her dramatic portrayals and her engaging stage presence.

Renée Fleming, one of the best-loved and versatile sopranos of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, has been described as "the people's diva," and perhaps comes closer than any other singer of her time to being an old-fashioned operatic superstar. Her wise repertoire decisions have allowed her to embrace a wide variety of works throughout her career, including Baroque opera, Mozart, the Italian bel canto repertoire, Verdi, Massenet, Puccini, Richard Strauss, a number of contemporary operas, and songs from all eras. Her voice is notable for its fullness, warmth, its creamy tone quality, and her ability to spin out long, velvety, legato lines. She is known for the intensity and integrity of her dramatic portrayals and her engaging stage presence.

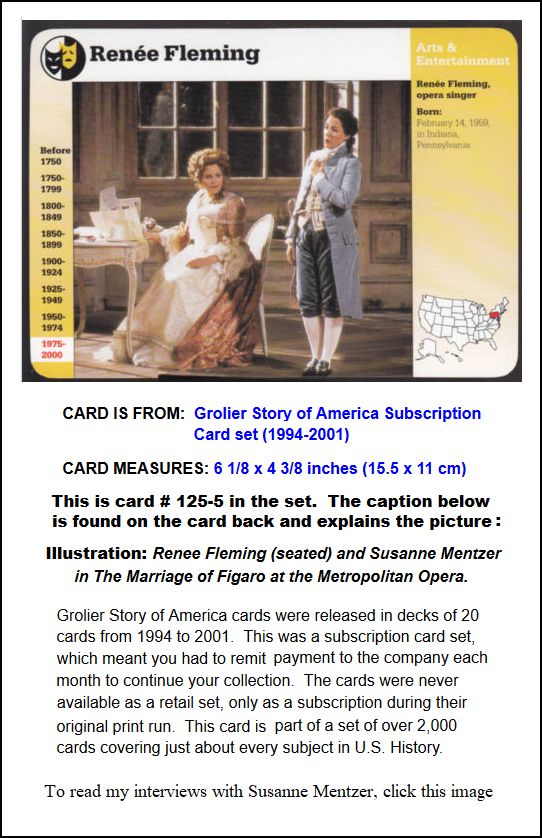

Fleming was born in Indiana, Pennsylvania, on February 14, 1959. Her parents were high school vocal music teachers in Rochester, New York, where she mostly grew up. In 1981, she graduated from the State University of New York at Potsdam (where she sang in a jazz trio at a bar) with a degree in music education and continued her musical studies at the Eastman School of Music, which she credits with giving her a strong academic and theoretical background. From 1983 to 1987, she was enrolled in the American Opera Center at Juilliard, where she met Beverley Johnston, the voice teacher with whom she would continue to study throughout her career. Fleming also recalls with admiration the year she spent studying Lieder with Arleen Augér, on a Fulbright Scholarship. In 1988, she won the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions and the George London Prize (in the same week), and the Eleanor McCollum Competition in Houston.

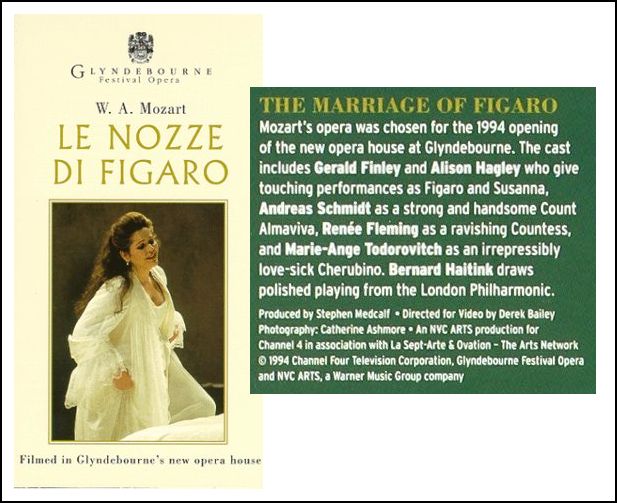

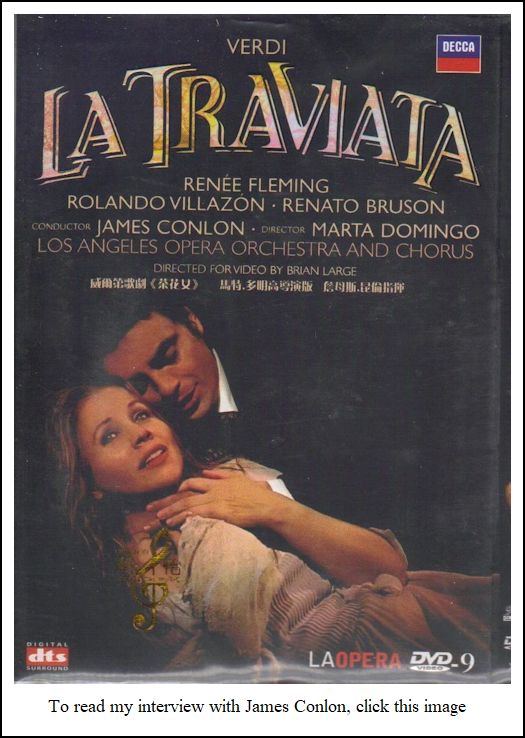

Fleming sang the Countess in Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro at the Houston Grand Opera in 1988, made her New York City Opera debut in 1989 as Mimi in La bohème, and her Covent Garden debut as Glauce in Cherubini's Medea later that year. In 1991, she made her acclaimed Met debut, stepping in for an indisposed Felicity Lott as the Countess, which was also her debut role in San Francisco (1991), Vienna State Opera (1993), and Glyndebourne (1994). In 1993, she made her debut at La Scala as Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni, and she sang Eva in Die Meistersinger at the 1996 Bayreuth Festival. Since that time, she has continued performances at the world's leading opera houses and concert halls and has continued to expand her repertoire. Among the roles for which she has won acclaim are Handel's Alcina and Rodelinda; Rossini's Armida, Violetta, Manon, Thaïs, Tatyana, and Rusalka; and numerous roles in Strauss operas, including the Marschallin, Daphne, Arabella, and the Countess in Capriccio. She created the role of Rosina inCorigliano's_The Ghosts of Versailles_ in 1991, Madame Tourvel in Conrad Susa's Dangerous Liaisons in 1994, and Blanche DuBois in André Previn's_A Streetcar Named Desire_ in 1998.

She has garnered praise for her many recordings, both on CD and DVD, has been nominated for 12 Grammy Awards and has won four, in 1996, 1999, 2010, and 2013. In addition to her work in the classical repertoire, Fleming has recorded contemporary pop songs, jazz, and film soundtracks. She has hosted a number of television and radio broadcasts, including The Metropolitan Opera's Live in HD series, and _Live from Lincoln Center_for PBS. Her honors include Sweden’s Polar Prize (2008), designation as Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur from the French government (2005), Honorary Membership in the Royal Academy of Music (2003), and a 2003 Honorary Doctorate from the Juilliard School. In 2012 she received the U.S. National Medal of the Arts from President Barack Obama.

-- Biography adapted from the Allmusic website.

-- [_Throughout this webpage, names which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD_]

When posting these interviews on my website, I don’t put a specific title on them (unless they were previously published in a printed journal, in which case, the title is included).So, most are just ‘A Conversation with...’. This one, however, could easily be called ‘Promise Fulfilled’.

When posting these interviews on my website, I don’t put a specific title on them (unless they were previously published in a printed journal, in which case, the title is included).So, most are just ‘A Conversation with...’. This one, however, could easily be called ‘Promise Fulfilled’.

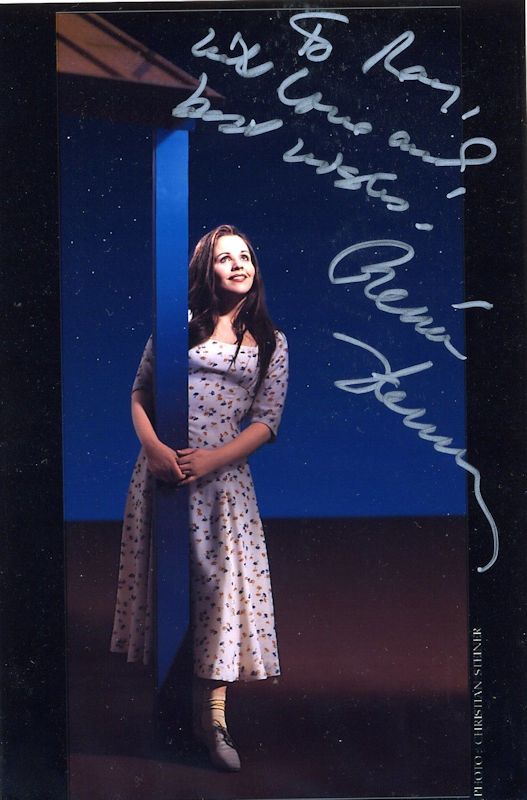

What you are about to read is a chat with Renée Fleming from October of 1993, when she was making her debut at Lyric Opera of Chicago as the title character in Susannah by Carlisle Floyd. This was just as she was beginning to become an international sensation, and long before her place in the operatic firmament was fixed. She had already made notable performances both in the U.S. and Europe, and her first recordings had been well-received. But without the trappings of super-stardom, her responses to my inquiries are, perhaps, more genuine, and are certainly more laced with the enthusiasm of a young, up-and-coming artist.

After a bit of chit-chat while setting up the tape recorder, we had gotten onto the topic of product-obsolescence . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: [With a gentle nudge] Are opera singers ever obsolete?

Renée Fleming: [Smiles] You mean specific people or in general?

BD: In general.

RF: No. We’ve been around this long, and I suspect it will continue. I wonder when the first opera singer was?

BD: The first operas were presented around 1600, so presumably the first singers were of that era, the ‘camerata’. Now you are involved in singing quite a number of newer operas. Is this a good thing for opera

—to continue to make it grow and sing new works, as opposed to just always standard repertoire?

RF: I would really like to be known as encouraging new works to be heard, and supporting the works. The legacy that Phyllis Curtin had and has left in her career comes right down to the dedication and the insight of my score of Susannah. Carlisle Floyd dedicated the opera to her, and thanks to her help and support she really pushed the project right from the beginning. They were explaining this to me when I met her on opening night. That shows her integrity as an artist, and really for our culture. The American culture lives and breathes. It’s not just Michael Jackson. We need to support the new operas, and make sure there’s a place for them in the world, and a place for it for young people to come and see them.

BD: Is the opera that you’re doing

— or any of the operas either new or old — for the Michael Jackson crowd, or is it just for converted crowd?

RF: That’s an interesting question. Do you want to write classical music for a small, elite audience

— and by elite, I mean sophisticated people who are well educated listeners — or do you want it to appeal to the masses, as it were. I think there’s a place for both, and I hope that both happen, because if you appeal to the masses, then they may actually find themselves more educated, and more interested in listening to something difficult. You can tell I come from an education background. My parents were both music teachers in the public schools, so it’s something that I care a great deal about.

BD: How can we make the operas that are currently around for more people?

RF: The Ghosts of Versailles kind of achieves that in its musical eclecticism. There was something in that piece for everybody. There were beautiful moments; there were dissonant moments; there were very exciting things, and also very romantic things. That opera really hit on everything, and it was a huge success. It was an extraordinary experience to be standing on the stage at the Metropolitan Opera, and looking at a cheering audience and knowing that the composer was alive next to us.

BD: Is that where opera is going today?

RF: There’s certainly a trend now in neo-romantic music. I’m working on The Dangerous Liaisons by Conrad Susa, which will be a world premiere next year in San Francisco, and the bits of music I have already seen are very beautiful. I

’m not a musicologist, so I don’t know if it’s because the years and years of exploring new things seems to have run dry, or if it’s because people are just tired of it, but that seems to be a trend.

BD: I assume that you are offered all kinds of new roles in new operas. How do you decide which ones you’ll select and which ones you’ll turn aside?

RF: [Smiles] I assure you I haven’t been offered that much new music. I don’t have the reputation that, say, Dawn Upshaw has for being involved in new music. It’s beginning to come up a little bit, and my decisions tend to be made on the basis of time, because I’m so overwhelmed with my schedule, and keeping particularly the operatic engagements through the next few years, that it’s tough for me to fit in the learning of new music. It’s time consuming, but I do as much as I can.

BD: Is it comforting to know that on a specific Tuesday, three years from now, that you will be singing a certain role in a certain house in a certain city?

RF: Yes, it’s comforting from one side that I know that I’ll be working. On the other side, it’s kind of overwhelming. It feels like a weight, in a way, to know that you will have to learn these things by these dates. It’s pressure, but I overwhelmingly feel supported. It’s a very happy thing.

BD: When you’re building your schedule, do you make sure that you keep enough time for you and your family?

BD: When you’re building your schedule, do you make sure that you keep enough time for you and your family?

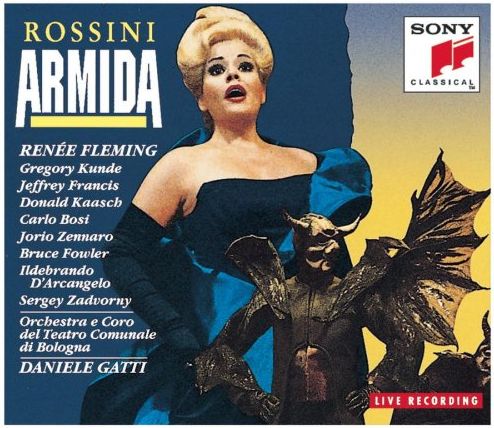

RF: [Laughs] I don’t yet. I’m trying to work on that. My husband is encouraging me to do that. I find it very difficult. To achieve what we do on this level, the international level, we have to be very ambitious, and that’s certainly a strong part of me. I was supposed to have the summer off, but somebody canceled, and I found myself in Pesaro, Italy, singing Armida [Rossini], so that was a big job. As I was working to death, killing myself to learn the role, I tempered it by saying,

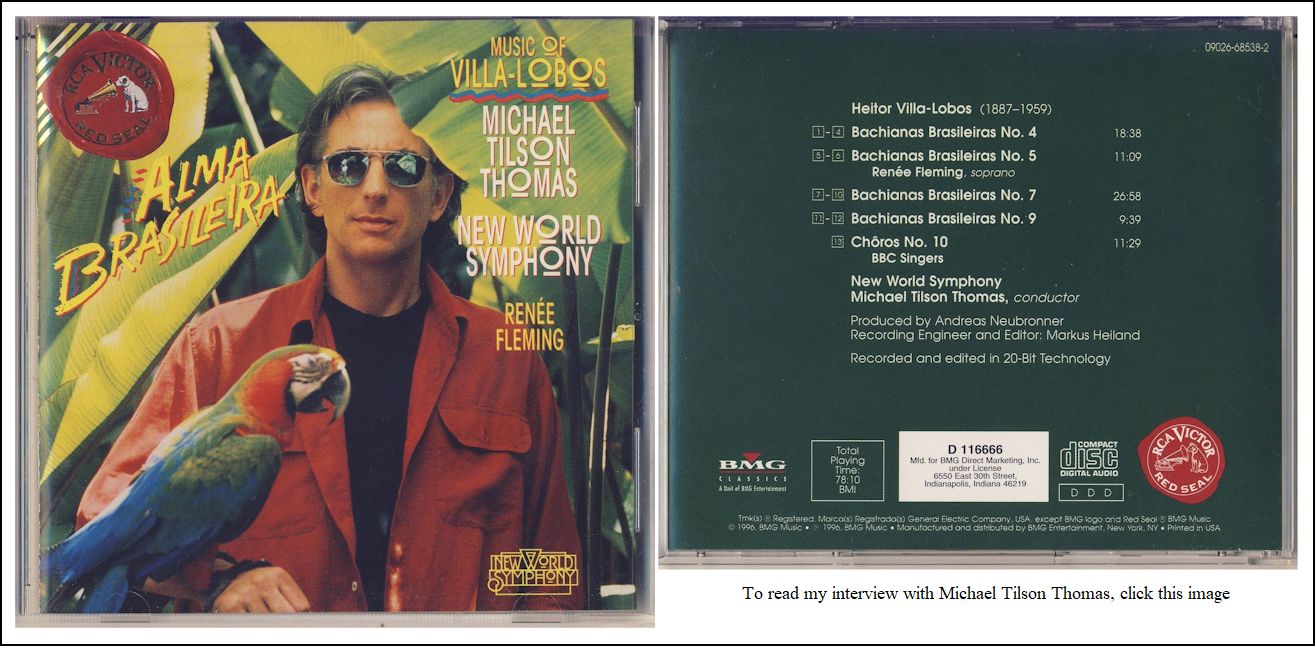

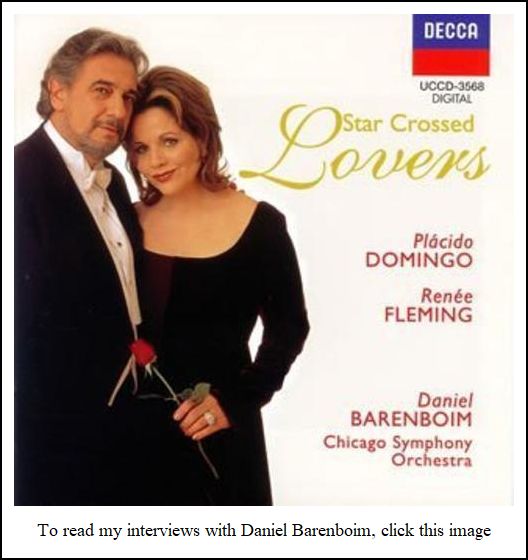

”We’ll be on the beach, and it’s a beautiful place to spend the summer.” I’m glad I did it. It was great, but I do work a lot. [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my interview with Donald Kaasch, which includes a photo him with Fleming in the Chicago production of Thaïs_._]

BD: As you look forward into your schedule then, are you making sure that there are big gaps?

RF: I’m trying more now. I’ll start with little gaps. It’s an addiction for me. They tell you when you’re young you

’ve got to learn how to say ‘no’. But you think, big deal, that’s ridiculous, and it’s true. It’s tough. It’s really not just for repertoire, but for the work in general. It’s very tough to say ‘no’.

BD: Let me ask it from a little different angle. When you’re offered a number of different roles, how do you decide which of the various possibilities you will take?

RF: I’ve developed a rule for myself recently

— and it makes sense — which is not to accept an engagement unless there is a compelling reason to do so. Money is NOT one of those reasons for me at this point. Maybe it will be some day when I’m old and jaded, but now there are four reasons I generally look at: (1) If it’s a role I really want to do; (2) if it’s a theater I really want to sing in; (3 & 4) if it’s a conductor, or a director I want to work with. If there’s something about that offer which says I must do it, then I do it, and I say yes. [Laughs] Unfortunately, there tend to be more and more offers which fall into these categories, and then it’s more complicated.

BD: Regarding the first of your four reasons, what about one or another role grabs you and says this is a role I must do?

RF: That’s a multi-faceted issue. First of all, I see if it’s vocally suited to me, and not just suited but also challenging. I like to do things that I can learn from. I don’t like to do things that are necessarily just easy. I’m very much a technical singer, in that I’ve had to work so hard with my technique, and I’m still working on it. Every night I’m thinking that if something didn’t quite feel right, what can I do that to improve that, and how do I do it? Very often I accept a role from that angle, but also I’m a literature person. I’m very much moved by stories and texts. If somebody hands me a bel canto opera, I want to know what the story is before I look at the music. I don’t know if that’s the norm, but that’s just the way I approach things. Then, I also ask if it will be good for my repertoire in general in the future. Is this something I’ll sing once and never sing again

— as has been the case with a lot of stuff I’ve done. I have to start looking at that as well. I only have so many days in my career that I can devote to it.

BD: [Playing Devil

’s Advocate] But you don’t want to miss something if it would be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, even though it would just be once.

RF: Absolutely. Armida was, perhaps, something I’d never do again, but it was a fabulous experience. It really bribed me. It was the most dramatic role I’d ever sung, and I thought Rossini was just like the Bellini I’ve sung. [Laughs] Ignorance is bliss! About two weeks after I was Pesaro, I realized this is a big sing! In Pesaro, they also do new editions which Philip Gossett prepares, and things are very long. There are no cuts. Things are not as easy as they were in the

’50s when they were doing these pieces.

BD: You could cut and paste to make it easier.

RF: Absolutely. Also, because the music was new to the audience, they didn’t really trust that it would be enjoyed and accepted in all its lengthy glory.

BD: Are we doing that same kind of educating of audience

— and singers — now for the new operas?

RF: [Thinks a moment] It’s hard to say, because new composers write incredibly varying vocal styles. A minimalistic opera can be extremely difficult for a singer, and instrumentalists also find this. It’s very difficult to make your voice move in a muscular pattern that is the same and is repetitive. Your mind gets tired very quickly, so that’s a completely different thing to attack than, say, John Corigliano’s work in The Ghosts of Versailles, which was much more classical

— depending on the character. My music was completely different than the music that Teresa Stratas [as Marie Antoinette] sang in that opera, so I can’t make any generalizations about it.

BD: How do you divide your career between new, or newer works, and the older standard repertoire?

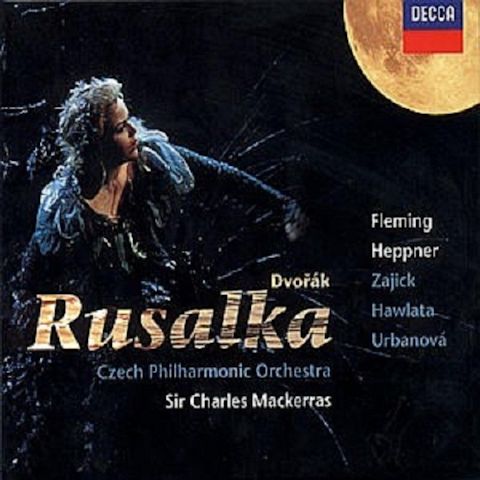

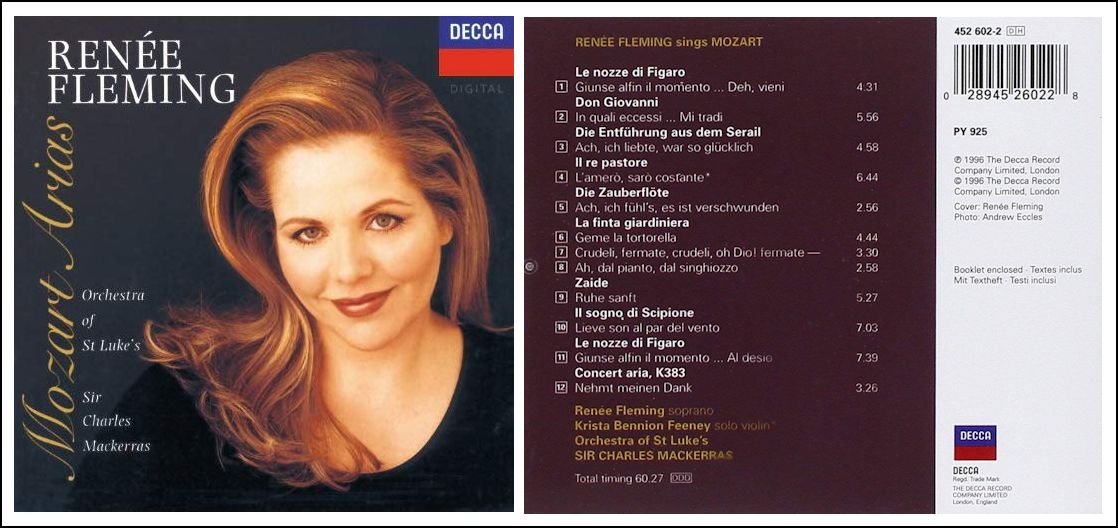

RF: I look at my repertoire, and actually new works don’t really fit into it that much at this point. I look at the core of my repertoire as being very much in Mozart. Most of my debuts in major opera theaters in the world have been in the role of the Countess in The Marriage of Figaro. I do a lot of Mozart, and then to the one side of that are the higher, more florid roles in the bel canto repertoire, which I find keep my voice in as good a shape as it can be. They’re the most virtuosic, and the most difficult, and I also love them because they’re so free and so expressive. They’re closest too my days as a jazz singer. I developed that and the bel canto repertoire together. Then, to the other side of the Mozart is the Slavic and Russian repertoire that I love

RF: I look at my repertoire, and actually new works don’t really fit into it that much at this point. I look at the core of my repertoire as being very much in Mozart. Most of my debuts in major opera theaters in the world have been in the role of the Countess in The Marriage of Figaro. I do a lot of Mozart, and then to the one side of that are the higher, more florid roles in the bel canto repertoire, which I find keep my voice in as good a shape as it can be. They’re the most virtuosic, and the most difficult, and I also love them because they’re so free and so expressive. They’re closest too my days as a jazz singer. I developed that and the bel canto repertoire together. Then, to the other side of the Mozart is the Slavic and Russian repertoire that I love

— Janáček, Dvořák, Tchaikovsky — which I’ve done quite a bit of at this point.

BD: So, you’ve got quite a large range. [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my interviews with Dolora Zajick, Franz Hawlata, and Sir Charles Mackerras.]

RF: It’s pretty big. In fact, I’m going to start really examining that, and trying to figure it all out. I don’t think I’ll ever be a sing who specializes. I don’t see that I’m going in that direction at all, or that I even want to. But I also want to be careful that I don’t spread myself too thin, which is beginning to be dangerous.

BD: When you get a new role and you’ve agreed to sing it

— either an old work or a new work — how long does it take you to learn it and get it into your voice and into your psyche?

RF: I would really like to say that I spend a lot of time doing that, but I’ll be very honest and say that I don’t, because I do six or seven new roles a year. It’s insane, and I have to stop that. That’s what I’ve been doing, and I’m going to stop doing that. What I’ve been doing is crazy,

and I don’t recommend it to any young singer — or anybody, for that matter. I have been learning a new role cerebrally, then going and singing it into my voice during the rehearsal process. It is much better to show up on day one knowing it, and then have three or four weeks — or sometimes five weeks — in rehearsal to iron out vocal problems. But that’s very dangerous. Ideally, you start working on a role a couple of years before you do it.

BD: Is it fun to come back to a role that you’ve already sung and have a few performances already under your belt?

RF: It can be really quite wonderful. I don’t know how many productions of Figaro I’ve done at this point. I’ve done quite a few, but when I did it in Geneva in May, I finally conquered Dove Sono. Other people will still have misgivings about what I do with it, but vocally and technically it was the first time I figured out how to sing that aria. So, each time you come back to a role you’ve sung, you find new things and you grow. That’s the best thing about putting something away and then coming back to it a year later. You never get bored, and if you have an engagement that’s unhappy for one reason or another, it’s just for six weeks and then you’re onto something else. You never get stuck anywhere.

BD: Would you prefer to be singing in one particular house at least for a major part of the year?

RF: That comes to another question. The way the opera world works in today

’s day and age, I don’t think that you could continue to grow professionally, or that your career could move ahead if you did that. It’s unfortunate because it takes its toll. It’s not great from a lifestyle question, especially if we travel ten or eleven months of the year as some of us do. I’d be much happier to stay in one place. I have a daughter now who’s thirteen months old, and when she goes to school, I don’t know what I’m going to do. But I found when I keep improving and I want to keep my career moving ahead, I have to keep on the road, and keep my profile up in all those theaters in Europe as well as in America. It’s a balancing act, and it’s not easy.BD: Do you like being a wandering minstrel? RF: No, not really, but that’s the part of what I do that I don’t like. It’s not because I don’t like to travel. I love to travel and I love to be in new places. I’m the kind of person that anywhere I hang my clothes is home. But I really miss my family and my friends, and that’s something that we always have to do. So, we manage.

RF: No, not really, but that’s the part of what I do that I don’t like. It’s not because I don’t like to travel. I love to travel and I love to be in new places. I’m the kind of person that anywhere I hang my clothes is home. But I really miss my family and my friends, and that’s something that we always have to do. So, we manage.

BD: Your husband is supportive of all this?

RF: Yes, I’m very fortunate. My husband’s an actor so he does what I do, but not really, so we’re not competitive with one another. At the same time, he’s supportive and understands. We met before I achieved success. We met ten years ago when I was a student, and I’m one of the lucky ones in the business. My father said to me before we got married,

“Now, Renée, I love you, and I think you’re wonderful, but I certainly couldn’t put up with your lifestyle, so you better marry this guy!” [Laughs] I took his advice and I’m glad I did!

BD: You say wherever you can hang your clothes is home. Are there special things that you do to make each place home, or is it just that home is where you are?

RF: Well, I sure travel with a lot of stuff! Now that I have a baby, we have to cart around her toys and the crib. We try to make it as comfortable as possible, and we have everything we need. I’m experienced at doing that now, so I’m pretty good at it even though when I’m home I

’m whipping through the suitcases, pulling out the clothes from one season and adding another. It works out very well. One advantage to having a toddler and being in corporate apartments is that there’s not a lot they can get into! [Much laughter] You don’t have to baby-proof anything, so it works out okay.BD: I assume you couldn’t live without the nanny along?

RF: No way.

BD: Is it particularly good to have a nanny who’s also getting involved in the business?

RF: I think it’s great. It’s something I’m going continue to try to do for a couple of reasons. One, you know are aware of the sacrifice that they make of also being away from their family and friends. In her case she’s learning about the business and she’s learning about the lifestyle. I’m also helping her a little bit with coaching, and I have an intelligent companion that understands what I do. If I have a performance, she’s more than willing to take the baby early in the morning, and not mind at all. So, it’s really the best of all possible worlds for this situation.

BD: If you come home and say you want to talk about something in the throat, she’ll understand.

RF: Yes, and she eats it up! She loves to talk about it, whereas probably anybody else who normally does this, would be probably find us a bit strange. [Laughs] It works out great.

BD: You’re here now for about seven weeks...

RF: This is very long. In fact, this is unusual because there are nine performances, which is more than the norm. After I opened on the 9th of October, I’m here for almost entire month just doing two performances a week. So, that’s almost like a vacation for me, which is great because I’m learning Jenůfa right now. It

’s sometimes rather chaotic and terrifying learning new roles for the next engagement, but I’ve loved it here. I like this city a lot.

BD: Good. Do you get a little time to explore the city?

RF: Oh, yes, I’m going to a bit. I have friends coming over the weekend, and I’m going to look around. I want to go to this great art museum...

BD: Yes, the Art Institute is world class.

RF: Absolutely, that’s what I hear.

BD: Is there a secret to singing Mozart?

RF: Mozart is one of the most difficult composers to sing. I can’t imagine how people think it is the best music to give to young singers because the thing that Mozart demands

— which is control — is the last thing that we all learn how to do. It demands a perfect line, a legato, and a perfect sense of style. You have to have complete dynamic control. You have to be able to sing _pianissimo_as well as forte, and sometimes from one bar to the next! Most difficulty demands an ease of singing in the part of the voice that we refer to as the passaggio, which is the very uncomfortable part of the range. It is a transition place between different parts of the voice in terms of register, so I find it the most difficult. The secret is experience. It is also having a very good technique, being in command of your voice, and having a very strong sense of style. It takes a long time to learn how to sing Mozart recitative well. You have to have command of the language — much more so than in Puccini or Verdi where there’s much less, or even no recitative. So, I think it’s the toughest. There is one thing missing from Mozart for the soprano voice in the roles that I sing, and that’s high notes. That’s why I enjoy the bel canto repertoire. I call it Mozart with high notes. I’m speaking from a vocal point now, not from a musical point, because it demands everything you do in Mozart plus having the top. So, I think it’s tough. It’s certainly been a training ground for me. I’ve learned to sing by getting in there and doing the Countess all over the place, and kind of hashing through it.

BD: If it’s so hard on the voice, especially in the passaggio, did Mozart not know how to write for the voice?

RF: There are things to take into account, and I suspect that singers produced their sounds then differently than we do now.

BD: Because of the smaller theaters?

RF: Smaller theaters, and also the pitch difference was as much as half a step lower. That changes things dramatically in that part of the voice and how it feels. I did_Così fan Tutte_ last year for the first time in Geneva, followed by the same role in Glyndebourne with original instruments, and in Glyndebourne, I tell you, it was a lot easier.

BD: Because it was lower pitch?

BD: Because it was lower pitch?

RF: Just the lower pitch, yes.

BD: How far down was it

— about 425?

RF: I don’t remember exactly the numbering. It wasn’t even half a step, but it felt very different because when you’re singing in that part of the voice, which is tiring, it makes a difference.

BD: If they offered you another Mozart role, would you accept that?

RF: I’m opening the new house in Glyndebourne this summer. They put the theater up for renovation, and the opening night will be Figaro. So, I’m really excited about that. [Vis-à-vis the video of this production shown at left, see my interview with Bernard Haitink.]

BD: Do you do any roles in the lesser-known operas of Mozart?

RF: I’ve done nine Mozart roles now. In fact, at this point I’m not so anxious to do new Mozart roles because some of those nine are roles in standard operas that I wouldn’t do it now, such as Zerlina and Susanna. So, I’ve done an awful lot of Mozart. I’ve only done Ilia once, but I really loved the music and loved that opera. I did Sandrina in La Finta Giardiniera with the Paris Orchestra. That was difficult and rewarding.

BD: Would you want to do Mademoiselle Silberklang in the Impresario?

RF: [Smiles] For fun some time, possibly! That’s a cute opera. I was looking at Donna Anna, and I decided it can wait. [_She would, of course, do the role, and preserve it on audio with Solti and video withLevine._]

BD: [Surprised] Really??? Why?

RF: It’s dramatic, so it’s a lot of work. Elvira’s character is so much fun. I’ve done Elvira quite a bit, and you don’t have to sustain quite the weight of sound in the high tessitura that Anna requires.

BD: Is it even more difficult to do a second or third role in an opera

— especially in the ensemble passages?

RF: The first time I did Susanna, I had already sung the Countess. I had some problems in the duet, so it’s tough. I know there are lots of artists who do it all the time

— particularly the men— and I don’t know how they do it. I honestly don’t know how they keep them straight, doing both Giovanni and Leporello, for instance. BD: They take one disc out of their throat and put the new disc in! [Much laughter]

BD: They take one disc out of their throat and put the new disc in! [Much laughter]

RF: Exactly! I find that difficult. You could be distracted for a moment, and oops!

BD: With the wide repertoire that you have, and all of the new roles, do you rely very much on prompters?

RF: I don’t. I started out on the regional level here in this country, where there are no prompters. The first time I experienced a prompter, I found it incredibly distracting. Even now, I’ve really only relied heavily on a prompter once, and that was for my first Così, particularly for the recits. I needed help with that, but there was no prompter for Susanna. They asked us, and we all said we could manage.

BD: There’s not even anybody in the wings just in case?

RF: No, we’re on our own. We all know the opera well enough, so we can help each other out on stage.

BD: Is it particularly gratifying to sing an American opera in an American house for an American audience?

RF: It’s really wonderful, especially having sung Italian in Italy this summer

— which was quite terrifying — and doing radio and television interviews in the intermissions on the opening night in Italian, and my Italian is not that good. The first thing I did when I came home was Barber’s Knoxville, and it was the most effective to open the Harris Hall in Aspen, Colorado. It was the most gratifying and wonderful thing. The music felt fresh. When you sing in your language, it is like removing veils from the front of your face. Suddenly you can see again, and you don’t have to wade through the swamp to get to the meaning. It’s all there; it’s completely accessible to me, and I hope the audience enjoyed it, too. The same is true for the audience here in Chicago, and particularly this Susannah. It’s so emotional and so direct. There’s really zero intellectual activity. This is meant to be a story that should get to your gut and your heart, and you should feel something about that. So, I must say I’m really pleased about the whole experience. I love it. That’s one thing I love about doing American performances.

BD: Is it odd to try to bring these operas

— some of which are a hundred or two hundred years old — to audiences that have lived through a couple of World Wars, and Depressions, and bombs and all of this?

RF: I don’t think it’s odd in the sense that our audiences are really any different than the audiences were then. There is one major exception, which is that when these operas were written they were new music, and that’s all the people had, or really listened to. There was no media, there were no televisions or radios, and when you think about that, that’s a rather mind-boggling situation. Really, the operas now

— as opposed to being almost completely a new living thing — are historic. Of course, people work very hard to make it new and to make it fresh, and people enjoy it as it is. They like hearing Traviata for the fiftieth time. So, that’s something I think about a lot, and find very interesting.

BD: Have you ever been involved in a production that updates in the wrong way, and goes too far in the production values and the ideas of the stage director?

RF: Yes, and I think it’s tiresome now. It’s been done for twenty or thirty years, and once you’ve gotten beyond the concept of whatever the director has put upon the opera, then it’s no longer terribly interesting. But sometimes it works fabulously. It works in such a way that people forget about the updating, and yet the opera seems fresh. I personally loved [seeing] Nic Muni’s Traviata at City Opera. I thought the second act was so shocking, which is what that opera did to its public when it came out.

BD: What was the gimmick?

RF: The people were in kind of a stripper nightclub joint with druggies around. It was kind of vulgar, and yet the whole spirit of the piece for me remained the same. I’m sure somebody sitting next to me probably hated it, but I thought it worked. Sometimes some of Peter Sellars’ productions I really enjoyed, and others not as much. I don’t mind it with standard operas. What I do mind is directors doing this sort of thing in operas that are not done very much. We haven’t seen this opera in twenty years, so let us see it and what it’s supposed to be instead of making it into something it may not be. But for standard repertoire, sure. Have some fun, and see something interesting.

BD: Where’s the balance between the artistic achievement and the entertainment value in new works or old works?

RF: It should be both. The bottom line is that’s what art is

RF: It should be both. The bottom line is that’s what art is

— it is entertainment. Yes, we’re supposed to be enlightened, and our lives are supposed to be enhanced. It should affect us very deeply and very movingly, but it is ultimately something that brings us joy and is entertainment. That’s a definition which has to be, first of all, discussed to find out what that means, and secondly, judged on a per-piece basis. It’s tough to answer, but we shouldn’t forget that what we do is primarily to move people. When I go to the theater, my scale of whether something has succeeded or not is whether I’ve been touched in some way, and more than intellectually. I want to get goose bumps by someone singing. I want to tears to come to my eyes by someone’s voice. I want to feel something because most of us — particularly in our society, and particularly ‘super-women’ like who me who try to do everything — end up feeling like robots just trying to get the next thing done while very much staying in control of our lives and running around. So, when I go to the theater, I want something to be affected in me — the spiritual side or the emotional side. That’s my scale; that’s how I judge things.

BD: You say you are a ‘super-woman’ trying to do all, and presumably a lot of the audience coming each night will be

‘super-women’ who are trying to do everything. Is it right, then, to be on stage portraying women who are essentially victims?

RF: Difficult question! [Laughs] That’s something I try not to think about very much because most every role I sing is a victim. Most all of the operas for three or four hundred years are based on women as victims. [Continues laughing] You got me! I’m not even going to even try to respond to this. I give up! I don’t know. If I think about that too much, I’d have to quit my job and do something else.

BD: Or would you try to restructure things to make new operas where women are not victims?

RF: Yes, new composers should be aware of those issues, and should think about them, absolutely. Operatic performance is one field in which women are completely not discriminated against. Every opera needs a soprano or two, and a mezzo very often, as well as they need the men, so there’s none of that problem. It’s also not a problem with men being paid more than women in opera. I’m also talking about what happens on the stage, so in that sense I feel very fortunate. If anything, it’s the opposite. There’s a lot of ‘Diva worshippers’ out there who put them on a pedestal.

BD: Do you like being on a pedestal?

RF: I’d be lying if I said no. Yes, of course there’s something really fun about that. We don’t have the kind of adulation that screen actors have which permeates their whole lives. It’s difficult for them to go out. There’s a relatively small part of the population who would know who any opera singer is, other than Luciano Pavarotti.

BD: So you could wander around in public and not be recognized?

RF: Absolutely, for the most part, yes. When people do come backstage after a performance and say, ‘

“Gee, we really enjoyed it,” I love that. It’s interesting... I often wish I were involved in something that was a little more service-orientated so that I could help people more. Of course, that is what I do, but it’s removed in a way. My only contact with the public is people saying they enjoyed it when they come back and say hello, or if I get a letter, and at this point it’s hardly overwhelming.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You mean the applause each night is not enough???

RF: Oh, that’s fabulous too, absolutely! I didn’t realize how much I depended on that until I was in a few productions where I didn’t get so much applause! Then I wondered if I’m dependent on applause. I couldn’t believe it because it either made me or broke me. I felt like I was successful based on applause, or maybe I better not try this role again. It does affect us a great deal.

BD: Do you change your vocal technique at all for the size of the house? You’ve sung in the smallest of houses, such as Glyndebourne, and in the largest of houses, like here in Chicago in New York.

RF: I don’t change my vocal technique for the size of the house. I might not be constantly thinking of projecting my voice in Glyndebourne

— as I would in this theater especially, more so even than the Met — but I do change my technique somewhat depending on the repertoire I’m singing. I’ll sing something like Susannah very differently than I would sing something higher, or a_bel canto_role, but it’s relative. I would give weight to the voice much more in this, and try to sing with a much rounder, richer, darker sound than I would if I were singing where I knew I had to constantly be carrying a higher tessitura — like in Mozart, or in the bel canto repertoire — but it’s a slight change. I don’t even know if very many people would notice the difference in the sound, but I feel the difference.

BD: You feel the difference in the projection?

RF: Yes, in how I produce the sound.

BD: Do you change your technique at all for the microphone?

RF: I haven’t worked much with the microphone yet [_remember, this interview took place in 1993!_], and the underground word is yes, you do. People don’t like to admit that because it suggests that only certain voices can record successfully

— which seems to be the case — and other voices which may sound fabulous in a hall are not so great on recordings. The other reason I learned that’s the case is because I used to try to prepare things by listening to recordings. I still listen to them a great deal, but I’d constantly go in for a lesson, and my teacher would say, “What are you crooning for??? Sing!” I finally made the connection (after years of this) that you can’t listen to a recording and sing a role that way. It’s not the same as being on the stage. You have to really use your body and sing out, whereas in a recording studio you certainly don’t.

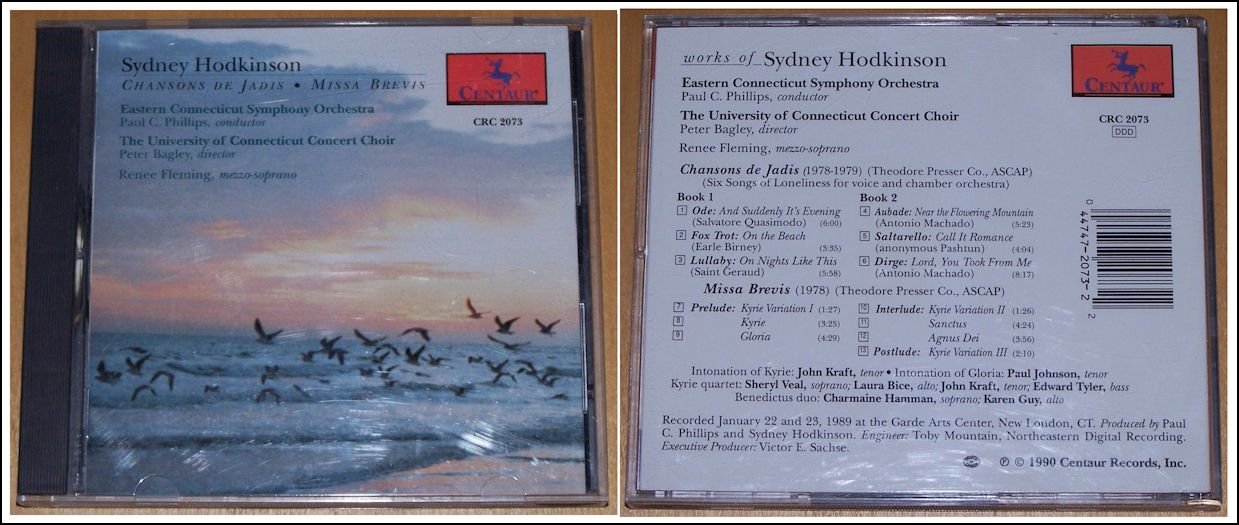

BD: Now, you’ve made the recording of the Hodkinson [_shown above_]?

RF: Yes, and I just recorded the Berg_Lulu_ and Wozzeck suites with James Levine and the Met orchestra. That should be released soon.

I enjoyed doing that very much. I would never sing those roles on stage, but I sure loved recording the suites because I love Berg. All of the other recordings I’ve done were of live performances — the Tucker Gala, the Berlin New Year’s Eve with the Philharmonic and Abbado, and The Ghosts of Versailles — so they were all things which I really didn’t have to think very much about what it was like. Armida was recorded this summer by Sony, and hopefully that will be released, too.

BD: I assume it’s important to add a few recordings to your list?

RF: Oh, yes, that’s the next frontier for me. It

’s something I’m really interested in now.

BD: Are you at the point in your career now that you want to be as it progresses?

RF: Oh, yes! I have no complaints. On the contrary, I feel fortunate to be where I am, very fortunate. Since 1988, when I won the Met competition and the George London Prize, things have moved in a very dramatic way for me, very quickly.

BD: Too quickly?

RF: No, absolutely at the right time. I wasn’t 22, I was 28, so it was absolutely the right time. I was ready, and only now I am really under the scrutiny of the international eye, as it were. That’s beginning now, and I’m ready for it. I can handle it now. I feel secure. My personal life is very stable, and my singing feels very stable at this point. I feel very fortunate. I wouldn’t want to be in this place a lot younger and less experienced.

BD: I hope you can sustain it for quite a number of years.

RF: I do, too. My latest obsession is to find out what makes voices go bad. I ask everybody I meet what they think happened to so and so. There’s not any real consensus about how that happens, but it does happen, and it’s terrifying. I need to be a little more careful with my repertoire, and with the amount of work I do, so I’m going to try to do that.

BD: Good. Are you coming back to Chicago?

RF: Yes! I don’t think I’m allowed to say in what, but yes, I’m definitely coming back. [_The full list of her appearances with Lyric Opera is shown in the box below._]

Renée Fleming at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1993-94 - Susannah [Floyd] (Susannah) with Ramey, Myers, Magee, Kraft; Manahan, Falls, Yeargan, Schuler

1995-96 - Faust (Marguerite) with Leech, Ramey, Hvorostovsky, Risley; Nelson, Corsaro, Colavecchia, Tallchief, Schuler

1997-98 - Marriage of Figaro (Countess) with Terfel, Futral, Hagegård, Graham, Travis, Cook,Davies;

Mehta,Hall/Lawless, Tallchief, Bury, Schuler

1999-2000 - Alcina (Alcina) with Larmore, Blake, Dessay, Kuhlmann; Nelson, Carsen, Hoheisel, Kalman

2000-01 - Otello (Desdemona) with Heppner, Gallo, Kaufmann (Cassio), Wrighte; Davis, Hall, Gunter, Henderson/Buswell

2002-03 - Thaïs (Thaïs) with Hampson, Kaasch, Cabell, McNeese, Morscheck; Davis, Cox, Brown, Schuler

2006-07 - Solo Concert, conducted by Sir Andrew Davis

2007-08 [Opening Night] - Traviata (Violetta) with Polenzani, Hampson, Baggott, Corona; Davis, Corsaro, Heeley, Binder

2010-11 - Reveived the title of Creative Consultant with Lyric Opera of Chicago

- Solo Concert conducted by Sir Andrew Davis

2011-12 - Duo Concert with Dmitry Hvorostovsky conducted by Sir Andrew Davis

2012-13 - Second City Guide to the Opera (Co-Hosted with Patrick Stewart)

- Duo Concert with Susan Graham, Bradley Moore pianist

- Streetcar Named Desire [Previn] (Blanche) with Rhodes, Griffey; Rogister, Dolton, Schuler

2013-14 - Duo Concert with Jonas Kaufmann, conducted by Sir Andrew Davis

2014-15 - Capriccio (Countess) with Skovhus, Von Otter, Rose, Iversen, Burden; Davis, Cox/McClintock, Pagano, Schuler

- Lyric Opera of Chicago 60th Anniversary Concert with many artists, conducted by Sir Andrew Davis

2015-16 - Merry Widow (Hanna) with Hampson, Carfizzi, Stober, Spyres; Davis, Stroman, Maravich

BD: Good. We look forward to it.

RF: Hopefully more and more!

BD: We are glad you’ve taken Chicago to your heart, and put us on your ever-growing list.

BD: We are glad you’ve taken Chicago to your heart, and put us on your ever-growing list.

RF: Oh, I love it. I could move here. I grew up in Rochester, so I know what this winter weather’s like. It’s cold in Rochester too. Before this engagement, I’ve sung here twice with the Symphony, and it was in January both times, so it was cold! It’s nice now...

BD: Yes, we’ve had rather mild weather of late.

[At this point, we chatted briefly about our educational accomplishments, and found

they were quite similar — both of us having earned a Bachelor’s Degree in Music

Education, equipping us to teach music in the schools . . . . . .]

RF: That’s what I would have done. That’s what my parents did, and that’s why they said not to assume a performance job. They told me to get my degree and have something to fall back on. [Both laugh] Interesting phrase, isn’t it? I go to my mother’s school and tell all these kids NOT to go into music. There’s maybe only one of them in the whole school who has a chance of having a career, and the rest could probably do much better doing something else.

BD: Is this the advice you have for all singers who are trying to make it their career

— don’t do it?

RF: The great majority, yes. I would say do something you can be successful in. I had too many friends back in New York who are struggling. It’s painful. I grew up in Rochester, and it depends. If you love it so much that you can’t do anything else, then by all means you’re doing the right thing.

BD: How did you manage to emerge?

RF: I had tremendous support. I had a fabulous education in three schools, and a Fulbright grant. It was a long education. I could have been a doctor by that time! [Laughs] I had a period of a few years where I had a lot of problems with my technique, my confidence, and everything. I was not somebody who just arrived on the scene that could do everything. It was all giving me a hard time, and I wasn’t really getting anywhere. Then at just the time I was about to quit, it gelled, and when it gelled, it worked in a very big way.

BD: I’m glad it’s all come together.

RF: Me too. I don’t think I’d be doing it if it hadn’t. There were too many other things I enjoyed. There are a lot of singers who find music themselves when they’re young , and it’s theirs. It’s something very personal for them. It wasn’t that way for me because my parents really pushed me along. So, I don’t have that feeling that if something ever happened to my voice I don’t know what I would do; I’d die! I don’t feel that way about it.

BD: You’d go on and do something else with your life?

RF: I’d do something else exactly.

BD: Thank you for the conversation. I appreciate it.

RF: My pleasure.

© 1993 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 21, 1993. Portions were broadcast on WNIB a few months later, and again in 1995, 1996, 1999, and 2000. This transcription was made in 2018, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.