William Mason Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

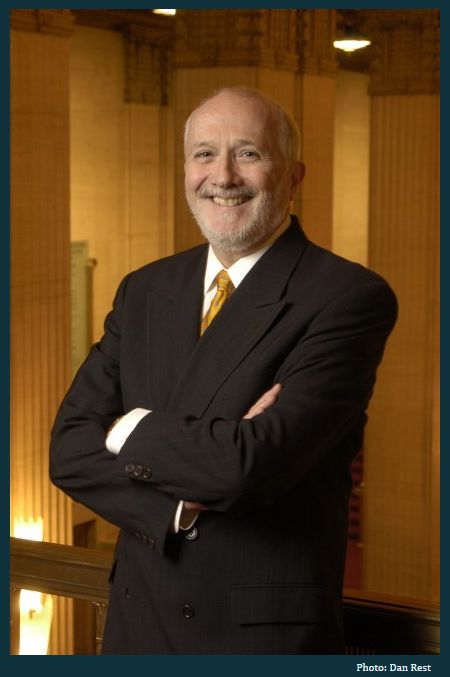

Manager William Mason

General Director,

Lyric Opera of Chicago,

1997-2011

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Though not a requirement of my full-time employment at WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago, I was able to present interviews with many of the musicians who graced our city. In the fall of 1998, I did a series of Backstage Interviews with those who kept Lyric Opera of Chicago running smoothly day after day, season after season. As shown in the photo below, it was a very interesting array of talent, and, by request, the series was repeated early in 1999.

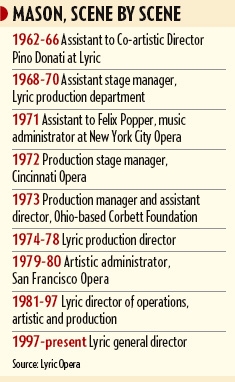

While a few of them were known to me, most were only understood to be there by their titles and superb execution of their tasks. I had met William Mason previously, and was one of the first people from outside of the company to congratulate him after he assumed the title of General Director. I knew he had been the Shepherd Boy in Tosca during the first few Lyric seasons, but I was amazed to learn of his rise through the ranks over the ensuing decades. His predecessor, Ardis Krainik, followed a similar pattern, taking on more and more administrative duties, as didDrew Landmesser, who is now, in 2021, Deputy General Director and Chief Operating Officer.

Mason took over the company when Krainik became ill in 1997, and spoke lovingly of her several times during our conversation . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Let

’s start with a real easy question. Tell me the joys and sorrows of running one of the world’s greatest opera companies.

William Mason: [Laughs] The joys are getting to sit and listen to music I love all the time. That’s one of the great joys. I

’ve always loved the opera since I’ve been a kid. So, to be a part of it, and to sit out there every night and listen to some of the great artists doing what they do best is one of the great pleasures.

BD: Especially knowing that you have been either in part or in full responsible for what is on the stage?

Mason: Of course, especially now that I have been a part of the planning for the last eighteen years with Ardis, and Bruno [Bartoletti], and Matthew Epstein. It’s always nice to see everything that you planned come to fruition on the stage. I’m the General Director, so when those seasons come up that are under my aegis, that will even be more satisfying. But there is a sense of continuity in a way. The first season that will be totally planned under my direction will be 2002, so I’ve got time before that.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] Time to enjoy, or time to head for the hills?

Mason: [Smiles] Time to enjoy.

BD: How much responsibility is strictly you, and how much is your team?

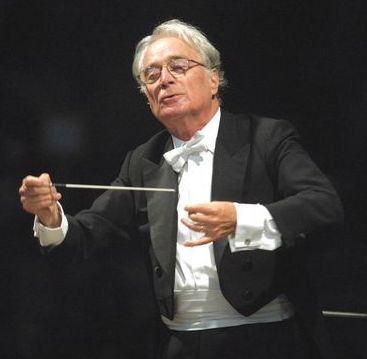

Bruno Bartoletti (Sesto Fiorentino, 10 June 1926 – Florence, 9 June 2013) made his US conducting debut with Lyric Opera of Chicago in 1956, conducting Il trovatore. In 1964, he was named co-artistic director of Lyric Opera, alongside Pino Donati, and served jointly with Donati until 1974. In 1975, Bartoletti became sole artistic director, and held the post until his retirement in 1999. Following his retirement, he had the title of artistic director emeritus for the remainder of his life. Bartoletti began as Lyric Opera's principal conductor in 1964, and served in that capacity until 1999. Over the period from 1956 to 2007, Bartoletti conducted approximately 600 performances of 55 operas with Lyric Opera. His other notable conducting work at Lyric Opera included conducting the US premiere of Britten's Billy Budd in 1970, and the 1978 world premiere of Krzysztof Penderecki's_Paradise Lost_.

Bartoletti focused almost exclusively on opera in his career, with few conducting engagements in symphonic work. He conducted several world premieres of works by composers such as Luciano Berio, Luigi Dallapiccola, Paul Dessau, Lodovico Rocca, Gian Francesco Malipiero, and Alberto Ginastera (Don Rodrigo, 1964).

The Italian government had bestowed on Bartoletti the rank of Cavaliere di Gran Croce della Repubblica Italiana. He was also a member of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia, and a winner of the Abbiati Prize. In his later years, Bartoletti taught at the Accademia Chigiana in Siena.

Mason: It’s difficult to delineate exactly. As the General Director, you’re expected to have the final authority and say so, but the fact of the matter is that under Ardis, it was a collaboration, and will continue to be so with me. No one person clearly has all the best ideas, and when you work with a group like Matthew and Bruno, and now with Andrew, there’s a synergy that happens. People sit around the table, and it’s all a set of ideas. That’s much better than one person doing it by themself. A lot of times people will ask, “Whose idea was this?” and it’s difficult to say because it came out of a collective meeting. You don’t really remember who had the very germ of the idea, but it was developed in such a way that truly it belongs to all of us.

BD: Does it ever surprise you that some ideas which sound outrageous actually come off... and that some ideas which sound wonderful you never get to?

Mason: Certainly that happens. We like to think that everything we do works out well, but there have been things that we’ve really wanted to do, and we’ve planned them out, or brought them to a certain point, and we’ve had to discard them. There are a number of those things. Certain operas we’ve talked about for years that we’d like to put on, and somehow we’d go so far, and then some crucial element is lacking or missing, and we have to discard them. Hopefully, we can re-instate them later. But I must say that by the time we’ve gotten to the point where we’re committed to something, we firmly believe that it’s going to be good and worthwhile. Otherwise, we would have jettisoned it before that.

BD: Can we assume that when you get your eight-opera season, that it’s the eight you’ve been left with out of twenty-five or thirty, rather than just the eight you’re stuck with?

Mason: Absolutely.

BD: Are some of these works that you’ve wanted to do operas that the public is always clamoring for?

Mason: In some cases, yes. In some cases, they just happen to be particular wishes of one member of the team. Maybe someone has a soft spot for an opera, but then it makes sense to do it. However, again, for one reason or another, it’s just not possible to do.

BD: How much opera should Lyric Opera be doing

— the whole repertoire? A part of the repertoire? Should you be expanding the repertoire?

Mason: I think eight operas is a very nice balance for us. I don’t see that we would go beyond that in the immediate future. It does enable you. When you’re only doing eight operas, you are able to really concentrate very thoroughly on those, unlike some of the European companies that do thirty or forty a year. Then, it’s impossible to give each opera the kind of care and preparation you can do when you’re only performing eight.

BD: A number of years ago, it was thought that over three seasons you’d get the real balance.

Mason: We sort of look at it that way. We try to maintain a balance in every season, but clearly, some seasons are a little bit out of kilter, and have less balance than others. But if you look at three consecutive seasons, we are hopeful that you will get a fairly balanced repertoire, with nice diets of everything that you need.

BD: From the vast repertoire, what should Lyric Opera be doing in any season?

Mason: The pillars of opera are Verdi, Wagner, and Mozart. I don’t think you can go a season or two without having one of those. Puccini and Strauss are right behind, and there will certainly be people who would argue that Puccini belongs in that first group. In addition to that, you want to have a smattering of other operas. You need some bel canto, and you need to represent the French repertoire. The Nineteenth century German group is pretty much taken care of by Wagner. There really isn’t much other than Wagner, though there are certain things such as Weber. We’ve got to get some of the Slavic things, the Russian, or the Czech, and you’ve got to do some pre-Mozart such as Gluck, Haydn, Monteverdi, and some Twentieth century European, as well as some American. I’ve done a chart with those groups, and I try to make sure that we maintain a balance among them. Over the course of several years, all those groups will be theoretically represented.

BD: Is there any artistic decision that you make that is not tempered by financial considerations?

Mason: Overall, no. It all boils down to money, as Ardis used to say. Some decisions less than others, but whenever you’re planning a season, in the back of your mind you’re always conscious of the financial implications of the whole season. You can’t plan a season of just enormous operas with orchestra, and supplementary chorus, and ballet. It wouldn’t happen that way, but nonetheless, when planning it, you have to keep that in mind. You have to keep in mind that you can’t do an opera season that will call for five or six new productions. You will want to have a few operas in each season that you’ll be able to bring from the warehouse. You’re always thinking, and that’s almost built into your thinking. It’s almost second nature to think like that as you’re doing the planning.

BD: Let me turn the question around. Is there any financial decision that does not have artistic ramifications?

Mason: No. It all goes hand in hand. It really does. There are some things you can’t do for financial reasons, and there are times when what’s something that might seem attractive from a financial standpoint doesn’t work fine artistically. Again, there’s a balance. I’m very big on the word

‘balance’. Everything has to be in balance. There has to be a proper balance in the season of both artistic and financial needs and desires. You can’t plan a season only thinking of the finances, and do a season of low budget operas. At the same time, you can’t do a season of ‘highfalutin’ artistic stuff where you’re going to blow the budget. You have to keep everything in a proper perspective and balance.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] Are opera singers balanced?

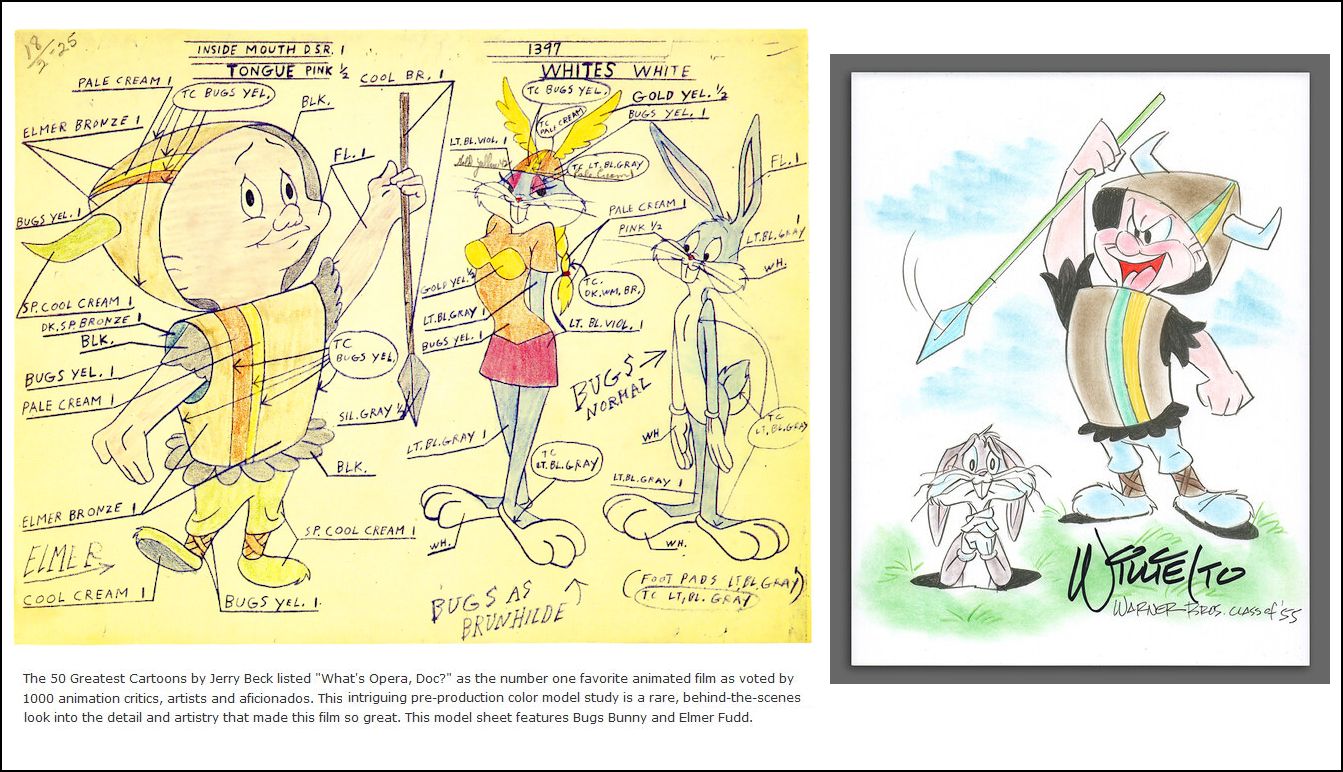

Mason: Absolutely. I know there’s a tradition that goes back to Bugs Bunny cartoons that says opera singers are temperamental and difficult, as many people in general are. Just thinking of conductors, the idea of a Toscanini or a Reiner standing in front of an orchestra today and doing the things they got away with fifty or sixty years ago would not be possible now. Any sort of things that happened of that nature years ago don’t happen today. By the same token, singers are better musicians. They’re better prepared. They’re better colleagues. There are very few people who give you any kind of difficulty.

BD: You’ve been involved in opera since you were a very little boy, on stage, backstage, and in the administration. Has opera continued to grow steadily, or have there been little spurts and then relaxations?

Mason: I think it’s been a steady growth. Clearly, the most important change in opera has been the swing over to the importance of the visual aspects of opera. In Lyric Opera’s first season, we did eight operas in three weeks. Anybody today going back and looking at them would see what appeared to be practically a series of costumed concerts.

BD: Just a couple performances of each one?

Mason: Two performances of each one in that first season. But in the old days of staging, it pretty much was a question. To stage the chorus scene, you would say,

“Sopranos and tenors on stage right, mezzos, and basses, and baritones on stage left,” and they’d pretty much position themselves there. Then, if you want to get real tricky, they’d cross at some point during the act. The principal singers would basically stand down stage, and do those things that were basic to what they had done in that same opera in Vienna or Milan. BD: They knew their own staging?

BD: They knew their own staging?

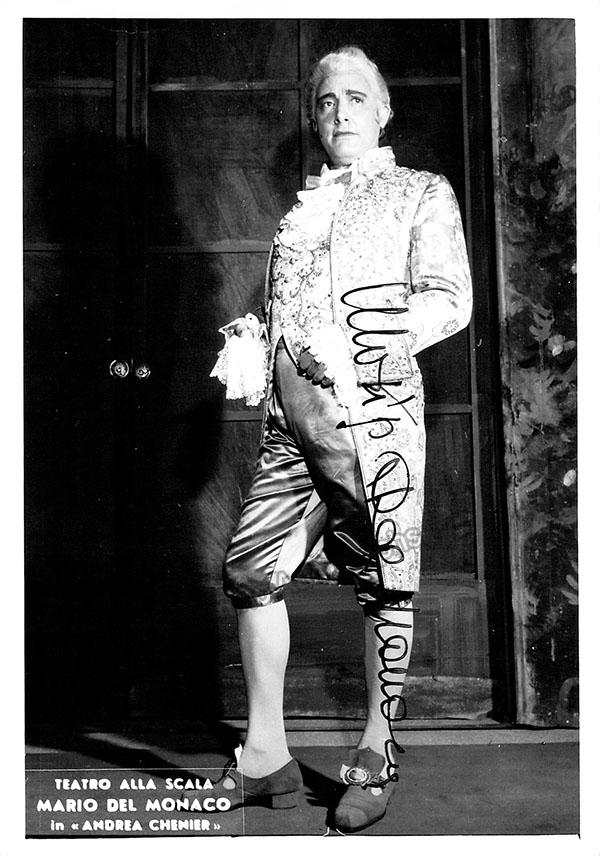

Mason: They knew their staging. In many cases, they brought their own costumes. They certainly brought their own wigs and boots. Mario Del Monaco’s wife made his costumes, so there wasn’t a sense of a cohesive physical production. [The photo of Del Monaco at right shows him in Andrea Chenier at La Scala, Milan, a role he also sang in Chicago in 1956.] Lighting was very primitive. When I was first stage managing in the early

’60s, we used to have a rehearsal on stage until 6 o’clock, and then change the scenery and lighting, and have everything ready for an 8 o’clock performance. Nowadays, with the complexity of the scene and the subtleties of lighting, on the day of performance we generally have to stop rehearsing on stage at 2 o’clock to be ready for a 7:30 curtain. So, it’s changed enormously. People’s expectations of the dramatic abilities of singers have increased.

BD: Do you think the composers who wrote these works a hundred or two hundred years ago are happy with all of this progress?

Mason: I think so. There’s a tendency for people to think that opera is only music, but we have to recognize that the original concept of opera was to marry theater and music together, to come up with something new. That’s why I find the discussion of which is more important

— the words or the music — a difficult one. I think it’s that combination of words and music. Many of the great operas were written by composers for whom the word was very important, and how they set the word was also important. Certainly, we know that from all of Verdi’s talk about what he referred to as the dramatic word, the scenic word, and his trying to get the right phrases and the right words. So, I think that they would applaud the improvements in stagecraft and dramatic credibility.

BD: Are the impresarios from years ago looking down from Heaven at you with envy?

Mason: I think so. My colleagues in Europe are looking across the ocean in envy. We have a very good situation is this company right now. We’re in good shape artistically and financially. We have a wonderful public, a wonderful Board of Directors, and volunteers, a whole support system. It’s a great company right now.

BD: Is it something that can be kept going for the next few years, or even the next many years?

Mason: I see no reason why not. Our mandate is to make sure that it happens.

BD: Was it easier or more difficult for you to walk into a situation that was running so well?

Mason: A little bit of both. When I took it over, there were certain things that were fairly easy quick fixes that many people could have done, but Ardis went far beyond that and made this company into a great institution. I’d been given the keys to a Rolls Royce. It’s wonderful to have this great machine that in many ways drives itself because of the staff, and the board, and the public that we have.

BD: But you’re still behind the wheel.

Mason: Yes. I don’t want to put it into a ditch. The people won’t let that happen.

BD: Does that make you be more careful?

Mason: No, you have to go forward, and in the same way that we’ve gone before, you have to be innovative. It’s terribly important that we do new things in opera. We’re entering the Twenty-First century, and it’s important that it not be an art form that’s totally mired in the Nineteenth century. It’s one thing to be one century behind, but it’s another thing to be two centuries behind. Those are great works of art from the Nineteenth century. We have to identify those works of art in the Twentieth century that are great and that will live on, and we also have to be constantly creating newer works if this is going to continue to be a viable art form.

BD: With that in mind, where is opera going today?

Mason: I’m not exactly sure. The general direction seems to be that it’s going along the music theater vein. It has to be with music that’s more listener-friendly and accessible. There seems to be a debate going on that you read in the Sunday papers and various newspapers whether it should be more accessible or whether or not that sort of pandering to popular taste, but pandering to popular taste is just what the great composers of the past did, and that’s why they were great. The idea that just because a composer spends a lot of hard labor and years producing something, the public is under no obligation to like it. People have to write things that people will want to listen to. At the same time, there has to be even a greater fusion of music and the theater for the American public today.

BD: Is there a clamor for this, or is there just a basic need for it?

Mason: There’s a need for it. The clamor will come from the new generation of opera-goers that we must attract. Those people who come to the opera right now are, in many cases, satisfied with the traditional approach of the traditional repertoire, but I’m not convinced that that approach will work for the generation of people in their 20s and 30s that we’ve got to attract to develop the audience for the future.

BD: What, specifically, is Lyric doing to develop audiences, and how is it working hand-in-hand with the rest of the world to keep the concert music and opera audiences coming?

Mason: We have many things that we’re doing in the way of education. We have our Opera In the Neighborhoods, and our Opera In English programs, plus our student matinees that we do during the season. By the nature of the type of productions that we do, we’re hoping to attract an audience that needs more than just to hear singing. It seems to be there’s a generation coming along for whom just listening is perhaps not enough. It’s a TV generation of people that have to have a visual that engages them at the same time. Our most successful productions are those where the musical components are satisfied as well as the dramatic. We’re hoping to do some things down the way in terms of new operas that we hope will combine this idea of finding music that’s listener-friendly with dramatic believability. In this country, it’s necessary to take components of music theater, and try to find those elements and intermingle them with opera.

BD: When you come to a meeting of the minds of Lyric Opera, about how long does it take for an idea to hit the table before we see it in the theater?

Mason: It’s a minimum of three or four years. Of course, it can be even longer in the case of operas that we think we want to do, but we have to shelve them for one reason or another. There’s one opera that I won’t mention at this point, that we’re talking about for a season down the road. The company has talked about doing this opera for at least 30 years, and we’ll finally get around to it in the next two or three seasons. Sometimes, something just clicks. Right now, we are in July of 1998, and we’re planning the seasons for 2002 and 2003.

BD: How do you know that the specific voices you contract will still be in good shape?

BD: How do you know that the specific voices you contract will still be in good shape?

Mason: [Laughs] There’s no such thing as a 100% guarantee. There’s no guarantee that a singer that we’ve hired even for this season won’t get a cold, or break an arm by October, God forbid. The singers that you’re engaging are at the top of their field. They sing well, and you have every reason to hope and expect that they will be in good shape by that time.

BD: Do you ever wish that you could take a singer who is doing real well and hire him or her for next month?

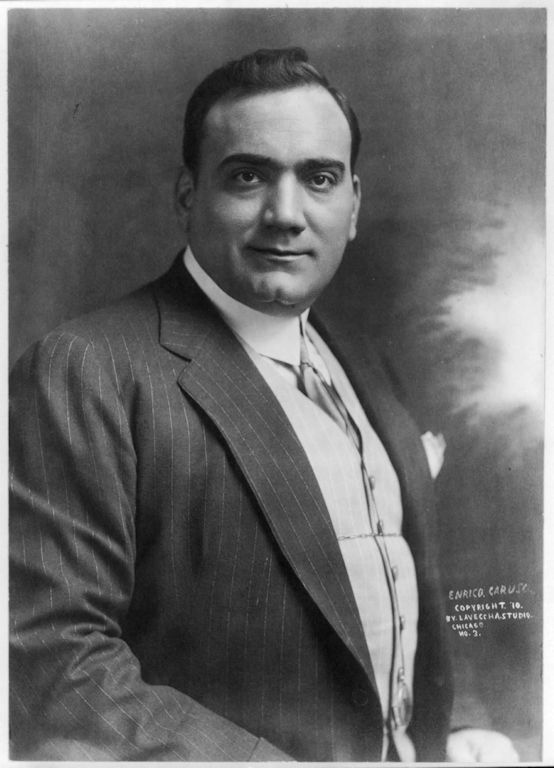

Mason: [With a huge smile] Oh, absolutely. Yes. The way we do things, the difficulty with planning so far in advance is that is if Enrico Caruso showed up tomorrow on our doorstep, we couldn’t hire him for another three or four years... unless someone got ill and we needed a replacement. [The photo of Caruso at left was taken in Chicago. To see an enlargement, click HERE.]

BD: [Musing] Caruso as substitute... that’s an interesting concept.

Mason: Every time you go out and audition singers

— which we’re constantly doing — you’re hoping and praying that you’ll discover some major new great talent, and recognizing that even if you do, you won’t be able to use them for a few years.

BD: Are you looking for a major great talent, or are you looking for just fine singing and fine artistry?

Mason: Both. Everybody would like to discover the new Bryn Terfel, the new Ben Heppner, the new Renée Fleming, etc. At the same time, you’re also looking to find solid, dependable, excellent singers who may not be the superstars in the future, but will be your solid dependable artists day in and day out.

BD: Are you finding them?

Mason: Sure. The training in this country is wonderful. There’s no singer better trained than the American singer today in terms of musicianship, style, languages. They really can do it all. The best singers in the world all come from this continent.

BD: What about the raw talent? Are we still getting that?

Mason: I think we’re getting the raw talent, and, as I say, it’s being trained very well. Clearly, there are people who might have gone into opera years ago who are not going into it today.

BD: Why?

Mason: They may be going into other sorts of vocalism, or they’re just not going into opera because it’s not for them. But the raw talent is there. It’s always been there. We do go through periods where certain types of voices aren’t necessarily available. The Verdi baritone may be rare at this point, or the Wagnerian tenor, or the dramatic mezzo-soprano. There’s always little slack periods for some of those voices, but then, after a number of years, someone comes up and they’re there.

BD: Then all of a sudden you have five of this voice type that you didn’t have before.

Mason: Yes, just so.

BD: Do you utilize your singers the best you can?

Mason: I hope so. In terms of utilizing your singers, you’re conscious of not hiring them for something for which they’re not suited particularly. You don’t want to see too many promising talents go astray because of singing the wrong repertoire, or singing it too quickly, too soon. You have some obligation to look out for the singers, particularly the singers of our ensemble, the Lyric Opera Center for American Artists. We’re very much aware when we cast them, either in roles or as understudies, that we don’t do anything that would be harmful to them.

BD: So, you really are concerned about them?

Mason: You’ve got to be, in light of self-interest.

BD: You’re looking at ten to twenty years down the line?

Mason: Exactly. You want to develop a talent that will have a career. Most singers, by the time they get into their 50s, if they last that long, feel that’s a long career. There are wonderful exceptions, like Alfredo Kraus [_who made his American debut with Lyric Opera in 1962, and sang here in twenty-one seasons_], who is still singing at age 70, and Placido Domingo seems to get better every day. However, there are singers who are so promising in their 20s and 30s, who had vocal crises somewhere in their 30s or early 40s, and that was the end of them. A few come back, but not all of them.

BD: In your career, you’ve been almost everywhere and done almost everything onstage and backstage. Does this give you a greater sense of need and urgency in the people who are now doing things for you, and a greater sense of compassion for people who have these almost insurmountable problems ahead of them?

Mason: I never did any kind of career as a singer, although I would have liked to, but I’ve been around enough to see the problems that they face. I hope I’m understanding and sympathetic to the difficulties of being an opera singer. It’s a difficult task.

BD: What about running the production backstage?

BD: What about running the production backstage?

Mason: It’s very important, and it’s been very helpful to me to have gone through that whole experience of working in a rehearsal department, then as a stage manager and assistant director. I got an understanding of how a production gets put together after the planning of it. That’s very useful to me now. Anybody running an opera company would find that very helpful to know. It’s not to say that you can’t do it without that, but then you’re relying on other people for that information. It’s comforting to have had the firsthand experience myself.

BD: Has it changed since you were actually giving signals back there?

Mason: Oh, absolutely. I’m sure the production staff is tired of hearing about what it was like when I was calling the show. It’s much more complex today. It’s an entirely different experience because the productions are more complex. The role of the stage managers is more developed. When I was doing it, one person was the stage manager and the assistant director. It was possible to do that then, but it’s not today. We have more people working on the stage in the production staff because the shows are so much more complicated.

BD: Your previous position was essentially getting everything done. You were responsible to execute all of the decisions that were made.

Mason: I was responsible for the artistic and production departments.

BD: Was it hard for you to fill your former position?

Mason: I haven’t filled it with any one person, but most of the things that I have done have been assumed by other people within the company. Everybody’s been ready to do so, and it’s worked out fairly well. There’s no one way to run a company.

BD: [With mock horror] You mean you don’t want to do everything???

Mason: [Laughs] No, not at all. I don’t need to do that. The focus of my responsibilities were shifted into other areas, because I have to give my attention to all those other areas of the company

— fundraising, finance, PR, and marketing. There’s a wonderful group of department heads that take care of all that, but I have to be involved in those issues. That clearly takes time from the artistic aspect of the company, but that’s why we have the people who can do that. With the addition of Matthew Epstein as our Artistic Director, he’ll be very helpful when he begins next year on a day-to-day basis during the season.

BD: Ideally, should you just sit here and let everybody else do their job, and almost recede into the woodwork?

Mason: No. I should set the direction of the company, and focus on those areas where my knowledge is more solid. Once you’ve made the decisions, you ideally should get out of people’s way and let them do their job. When you have a staff as good as this, they will know when they have to come to you for advice, and what decisions they can and can’t make. That’s why I’m very fortunate having taken over this company after having worked with these people for so long. We know each other, and I trust them. They trust me, and know how far they can go without coming to me. I know that I don’t have to worry about it, and when there’s a problem, they will come to me.

BD: They know they can always just knock on your door and get an answer?

Mason: Yes, absolutely. In many cases, it will be just a question of following their advice. I don’t presume to know more about finance than Rich Dowsek [_who was with Lyric Opera for thirty-two years_], or fundraising than Farrell Frentress, or PR and marketing than Susan Mathieson, but there will be some things where there will be an overview that’s necessary when there are conflicting interests to be balanced out, and that’s what this position is for. It’s not so much to tell any one of those people how to make the crucial decisions in their department, but when there are a number of issues to be considered, there’s an overview that has to be taken into account, and that’s where I come in.

BD: So, everything comes to you, and then you have to make sure that it goes out in balance.

Mason: In balance, absolutely. It’s about keeping things in balance.

BD: Did you sing any other parts besides the Shepherd Boy in Tosca? [1954 and 1957 with Steber, Di Stefano, and Gobbi, and 1956 with Tebaldi, Bjorling, and Gobbi. Also in 1954, Thomas Stewart was Angelotti.] Mason: That was it, plus being in the children’s chorus of Carmen and Bohème. That was the extent of my professional operatic experience.

Mason: That was it, plus being in the children’s chorus of Carmen and Bohème. That was the extent of my professional operatic experience.

BD: Do you now look very carefully at who sings The Shepherd Boy whenever Tosca comes up?

Mason: [Laughs] Well, I suppose I do. Yes, of course I look carefully at everything that somebody sings. I must admit I got a kick out of singing. We’ve been doing it with kids [_as opposed to adult females_] the last number of times that we’ve done it. I remember what a thrill it was for me, and I hope that they are enjoying it as much as I did.

BD: How much does it surprise you that the kid singing the Shepherd Boy is now sitting in the top chair?

Mason: I guess it’s very surprising. It’s very gratifying. I signed with this company in its first season, in 1954, and, God willing, I’ll be around for the fiftieth anniversary in 2004. I can’t tell you what a sense of satisfaction that gives me. It’s a dream of mine that I’ve always had, and there’s a possibility of realizing it. [_Mason would remain with the company through 2011._]

BD: Do you ever look at a Shepherd Boy and say,

“You’ll be in this chair in thirty-five years”?

Mason: If that’s what they would like, then God bless them. They could find other ways of making a living that might be more gratifying for them, but whatever they do, that’s an experience they’ll carry with them for the rest of their lives. It’s quite thrilling. I’ll never forget being backstage during the third act of Tosca and hearing the French Horn start. It does give that electric thrill. It was just magical.

BD: Does that does give you more sympathy for the singer who’s either doing the Shepherd Boy or doing Wotan?

Mason: I think so, yes. I have such a little experience as a singer, and I don’t pretend to be able to be one, but I certainly have a greater understanding of singer. Ardis had a wonderful voice, and sang some minor roles here.

BD: Am I wrong in assuming though that a number of the General Managers if opera companies around the world have never actually stood on stage?

Mason: Yes, I’m sure that’s true, but I must say my colleagues here in America are very, very knowledgeable. There’s a wonderful group of opera directors in this country, certainly in the major companies. Joe Volpe [Metropolitan Opera in New York] is solidly based, from being the head carpenter and technical director, and then being in charge of all the production aspects of that company. Lotfi Mansouri [Canadian Opera Company in Toronto, then San Francisco Opera] performed when he was young, and is a stage director. He speaks many languages, and is enormously talented. David Gockley [Houston Grand Opera] had been a singer, as was Plato Karayanis [Dallas Opera]. So, many of my colleagues in this country do have that background of having been a performer or having worked on stage, and having worked their way up in the field of opera from the very beginning.

BD: What advice do you have for someone who wants to eventually be General Director of an opera company?

Mason: I don’t think there’s any one way to do it. At some point, they should start off young and work in some aspect of it. The production and technical areas are a very good way to get involved in the basics of opera, and those things that certainly are financially important to the company. A music degree and a solid knowledge of opera is also fairly important, but there’s no one way to approach it. If you look at the heads of Chicago, San Francisco, and the Met, we all came about it from slightly different ways. The common denominator being that really it’s been our life.

BD: So, you really need to immerse yourself.

BD: So, you really need to immerse yourself.

Mason: I think so.

BD: Someone looking for a nine-to-five job better go away?

Mason: They would be well-advised to do something else. Whatever it is, it’s not a nine-to-five job.

BD: I assume you would never want to be in a nine-to-five job?

Mason: No. I don’t know what I would do with the rest of my time.

BD: [With a big smile] You

’d go to the opera!

Mason: [Also with a big smile] I’d go to the opera. It’s a wonderful life. Working in the theater and opera is a great way to go.

BD: Does this give you, then, perhaps a skewed perspective on someone who works nine-to-five, and then comes to the opera?

Mason: I hope not. They

’re people that we are here to entertain, and make sure that the money they’re spending they consider to be well spent. When they walk out of the theater, they will be satisfied with what they’ve seen.

BD: How much is art and how much is entertainment?

Mason: I don’t know. That’s a philosophical question, and I don’t get into that too much. The important thing is that you have to do everything very well, and then it will be entertaining. Anything done well, the public will understand. Clearly, there are going to be pieces such as Un re in ascolto that are very difficult for people. [This work by Luciano Berio, of which Lyric Opera had given the American premiere in 1996, was part of the series Toward the 21st Century.] That’s the sort of work we can’t do too often, but I would like to think that anybody who came to that would recognize that it was something that was very well done.

BD: They can expect to see something like that every few years?

Mason: Every so often. I don’t want to say,

“Every few years,” because that’s very tough for people to take in. It may very well be that fifty or one hundred years from now, the public will find that quite accessible. I’m not so sure that’s the case, but you have to give people the chance. There’s always the idea that people will say, “We don’t want to be educated, we want to be entertained.” That’s a viewpoint I certainly understand, and I respect. At the same point, my obligation is two-fold. It’s to entertain those people, and at the same point also to promote and ensure the future of opera. In doing that, you occasionally need to present those works that are on the cutting edge, and expose people to that, and then let them decide whether they like it or not. It’s not possible just to think of it only as entertainment, and it’s not possible to think of it only as art. We get back to the idea of balance.

BD: We’re dancing around it, so let me ask one last philosophical question. What’s the purpose of opera?

BD: We’re dancing around it, so let me ask one last philosophical question. What’s the purpose of opera?

Mason: What’s the purpose of anything? The purpose of opera is that it ennobles us, and it enriches us, as does any art form. Music is certainly a universal language. It’s a cliché, but it’s very true. There’s not a culture that exists in the world, from the most primitive to the most advanced, that doesn’t have some sort of music as part of its culture. At the same time, most of those cultures have some sort of storytelling, dramatic re-enactment of either legends or romances or novels, depending upon the level of sophistication of that culture. So, opera responds to something that’s innate within us, which is that need for music and for theater. Whether it’s rock

’n’ roll or whether it’s opera, people need music, and we satisfy that need. [Photo at right shows the entrance to the ticket office. The element at the top-center is repeated throughout all areas of the building. To see a fantasy on this element by Kathy Cunningham, click HERE.]

BD: Are you, through Lyric Opera, trying to satisfy it in one specific corner, rather than a greater corner?

Mason: Yes. Obviously, opera will always be... well, I don’t know if it always will be, but at this point it’s an art form that appeals to a limited segment of the population. One can’t pretend that we’re going to fill Soldier Field [home of the Chicago Bears football team, with a seating capacity of about 67,000] doing some of the things that we do.

BD: Would you want to?

Mason: I wouldn’t mind. I would like to see opera and music theater expand to the point where it has a wider audience. I’m not looking to narrow it to a select elite few of the initiated that could enjoy the art form. I would like to see it spread because there’s something ennobling and enriching about it. I think Mozart was a genius. There’s a sublimity to that music that is important, and the more people who are exposed to that, the better the planet will be. That

’s a little far-fetched to say, but it certainly wouldn’t do it any harm.

BD: There have been studies recently showing that if you listen to Mozart, your grade-point average will go up, or your productivity at work will increase.

Mason: [Laughs] Or cows will give more milk. I believe it, though I suppose it’s only anecdotal evidence...

BD: Does that information create more clamor for more Mozart?

Mason: I hope so.

BD: Does it mean that you’ll market it as Opera for Better Grades?

Mason: [Laughing] No, I don’t think so. That’s up to the marketing department, but I don’t think so. That’s not the point. We’re not looking at this to be that you go to the opera, so you’ll get better grades, or you’ll get a better or higher-paying job. It’s very possible that would be the case, but I don’t think that’s the approach. We want to encourage the spread of music of all sorts, but specifically opera, because music is just so important to us. If you ask them, and they have thought about it, most people could not really envision living without music. For those of us whose particular brand happens to be opera, we couldn’t live without opera any more than anybody who likes rap or jazz could say they would be willing to go the rest of my life without it. It’s just too important to us.

BD: You’re from Chicago originally and you’ve been here practically all of your life. Is it special to be running the opera company in your hometown? Mason: Absolutely. This is a great city.

Mason: Absolutely. This is a great city.

BD: What is it about Chicago that makes us special?

Mason: There’s something about Chicago and the Midwest. There’s a work ethic here, and there’s a friendliness. We’re blessed with the foresight of the civic planners and leaders of the past for giving us a city that’s aesthetically beautiful. There is something special about this city that differentiates it from any other city that I’ve been to, and it makes me very pleased to be a part of it, and very happy to be running this opera company in the city.

BD: Was it necessary for you to go away for a couple of years here and there just to get experience in the world outside?

Mason: Oh, sure. It was very helpful to me to have spent time on the road as a stage manager, and to have worked in New York, and at the San Francisco Opera, and Cincinnati opera. I like to think we do it a right way here, but we don’t do it necessarily the right way. There’s much to be learned on how things work in other companies, for better or worse.

BD: There’s no one manual that you can just follow play by play?

Mason: No. I wish that were the case, but the life experience of living at other places is very valuable. This is a great, great city, and it needs and deserves an opera company worthy of it. That’s what we intend to do.

BD: I assume you’re going to try to continue to expand the season?

Mason: I’d like to. Certainly, there’s pressure to do that from the unions. In my heart of hearts, I would be delighted if we had the demand and the ability to perform opera fifty-two weeks a year, but that desire has to be tempered with financial prudence.

BD: If you had no financial worries at all, and you didn’t have to consider the costs, would a few, or many, or all, or none of your decisions be similar or different to what you make?

Mason: It’d certainly be different. Ardis used to talk about the Money Tree. She wished she had a Money Tree, and every day she’d just go out and shake the tree, and money would fall down. Then, it would replenish itself by the next day. In the real world it’s unlikely that we will ever run this company, or any company for that matter, without basing decisions on the financial considerations. That’s not the worst thing in the world.

BD: But speculate about it for me.

Mason: No, I don’t think that’s a good thing, to tell you the truth. There’s a discipline that financial restraint imposes that’s well worth it. I see that very clearly in planning productions. You give a director and the designer a budget, and they have to live with it. Then, as often as not, and understandably so, they will come back with initial designs that exceed what you have to spend. Then you go back and say, “I’m sorry. We can’t spend all this money. You’ve got to take all these ideas that you have, and boil them down to what’s really important.

”In so doing, they really distill it to the point where the product is better than if there was an unlimited amount of money available to them. It makes you concentrate on what’s really important. If we were able to say to somebody, “Here, we have an unlimited amount of money at your disposal. Spend what you want on this production,” it would become over-lavish, and it would cloud the thinking in a way. Discipline is a wonderful thing in everything, and financial discipline is also important.

BD: You don’t want to have another Walter Felsenstein?

Mason: No.

BD: He had basically unlimited funds at the_Komische Oper_ in East Berlin.

Mason: Right, but that was a different time. That’s not going to happen again in our lifetime.

BD: Are you glad you’re living now?

Mason: Do I have a choice? [Both laugh] Yes, very much so. As I say, this is a wonderful company. I’m doing what I enjoy doing in a city that I love. It would be nice to be able to go back in time and be there for the premiere of Verdi’s_Nabucco_, and see what happened, or maybe to be able to go ahead fifty years and see what will be happening in the world of opera, and in the world of science and literature, and so many things. But I think this is a good time.

BD: Where do you see the company on its fiftieth birthday, or its one-hundredth birthday?

Mason: That fiftieth birthday is only six years from now. I see the company going along as we’re going now, hopefully having a terribly exciting season, and doing it up in fine style. One-hundred years from now, that’s a prognostication I’m not prepared to make. I would hope the season would be longer, and I would hope that there will be many new works in the repertoire, and that it would be a vital and ongoing cultural institution. One can only hope.

BD: Are you at the point in your career you want to be right now?

Mason: Oh, sure. I thought I wanted to run an opera company for a long time. I went through so many stages. When I was twenty-three or twenty-four in the rehearsal department, I thought I could run an opera company then. [Laughs] I knew better than anybody else. Then I went through a period where I wanted to run an opera company, and thought it would come sooner or later. Then I went through a period where I thought, “Am I the right person to run an opera company? Maybe I should just stay in the artistic and production area.” Up to a few years ago, I don’t want to say I’d given up, in the sense of it being negative, but I had resigned myself that it wasn’t going to happen. I thought I’d retire before Ardis, when unfortunately she became ill. That changed things, and so here I find myself running this company that means so much to me, and it’s very gratifying. One of the reasons that people enjoy performing here so much is that we want this to be an enjoyable place to work, and there’s no reason why it shouldn’t be. What we’re trying to do is perform opera at the very highest level. But even with the standards of excellence that we always must strive to attain, there’s no reason why we can’t have a good time while doing that, and no reason why it can’t be a pleasant and enjoyable place to work.

BD: Thank you for being part of it for so long, and for spending the time with me today.

Mason: My pleasure, thank you.

======== ======== ========

---- ---- ----

======== ======== ========

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in William Mason’s office in the Civic Opera House of Chicago on July 14, 1998. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following October, and again in 1999. This transcription was made in 2021, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information abouthis grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.