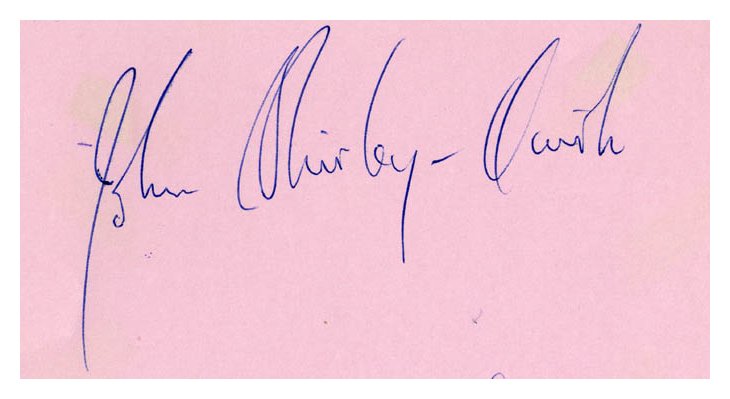

John Shirley-Quirk Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

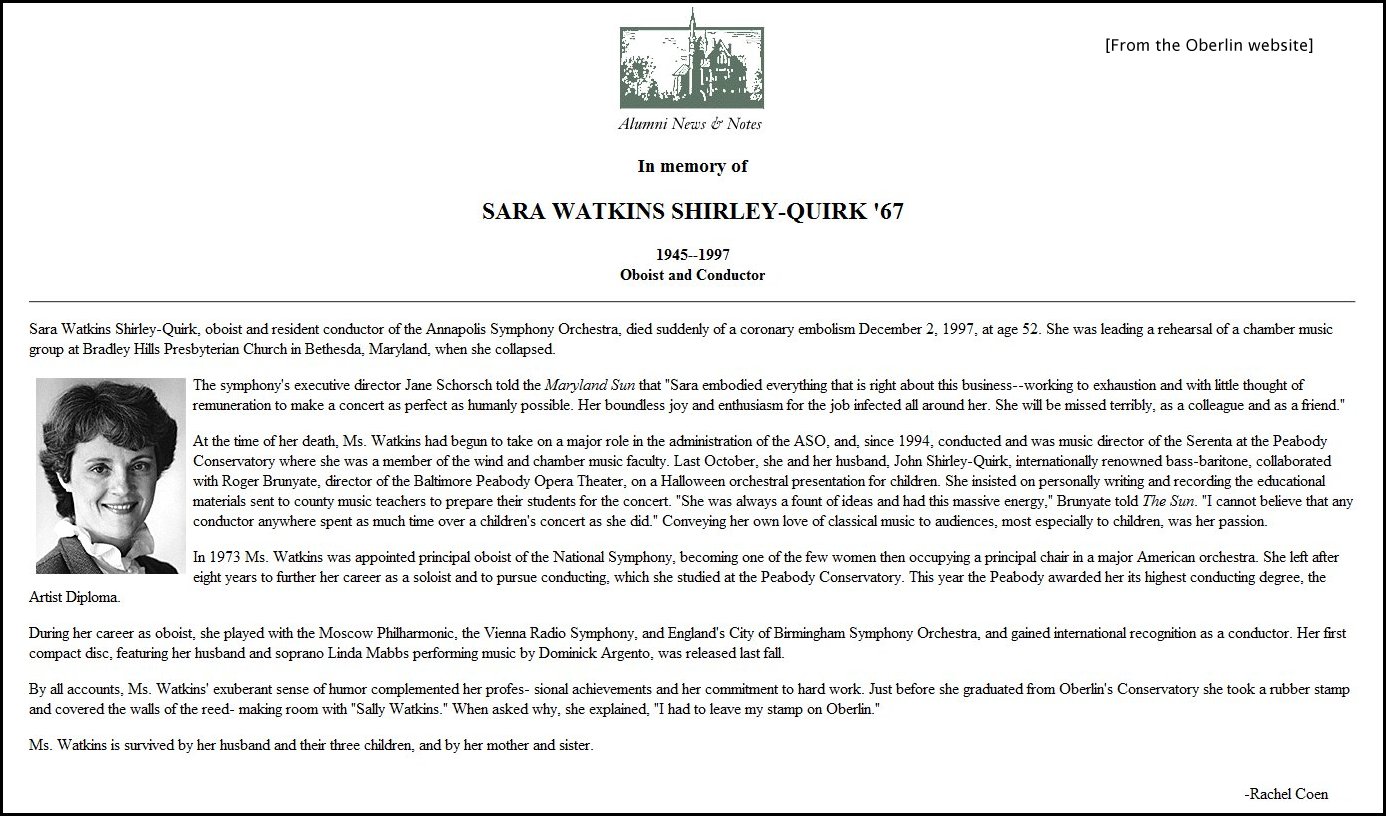

Baritone John Shirley-Quirk

and Oboist Sara Watkins

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

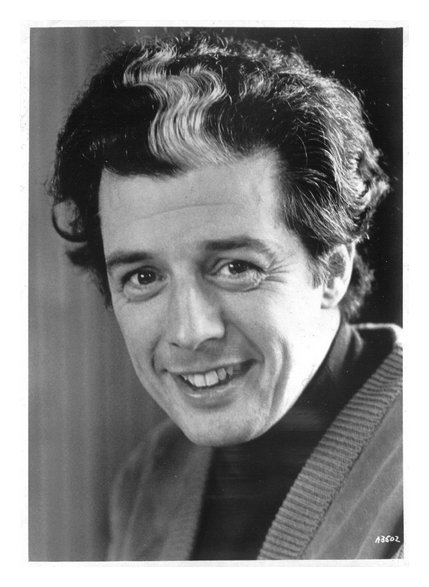

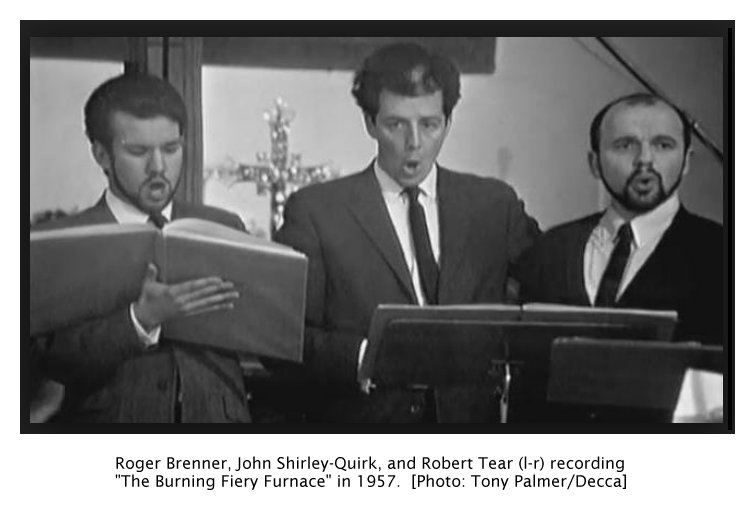

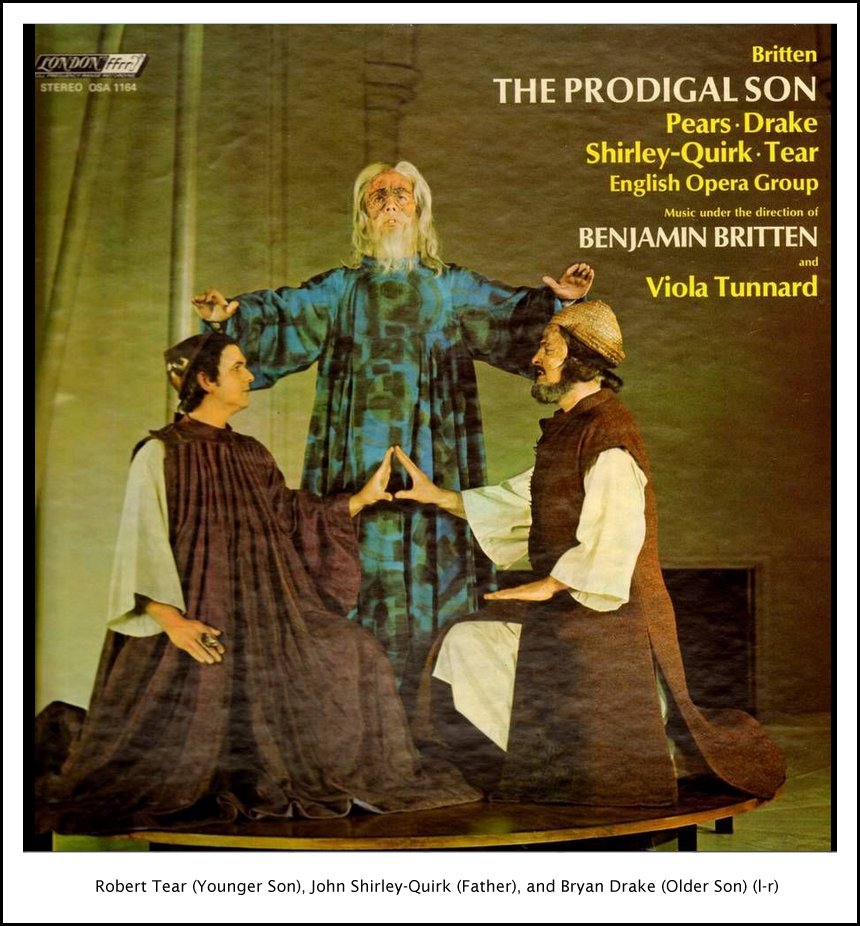

John Shirley-Quirk, who has died at the age of 82, established a niche for himself as the bass-baritone of choice in countless performances, both live and recorded, not least in the English-language repertoire in which he excelled. A close colleague of Benjamin Britten, he sang with the English Opera Group from 1964, creating roles in a number of Britten's dramatic works. His first assignment was the Ferryman in Curlew River and he went on to create Ananias in The Burning Fiery Furnace (1966), the Father in The Prodigal Son(1968), Mr. Coyle in Owen Wingrave(BBC TV 1971, Royal Opera 1973) and the multiple baritone roles in Death in Venice (1973).

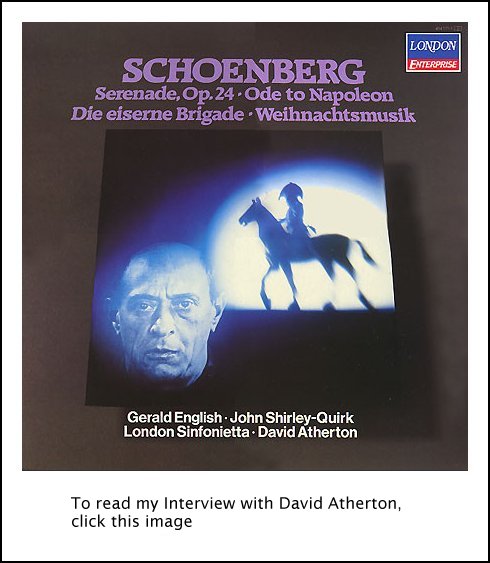

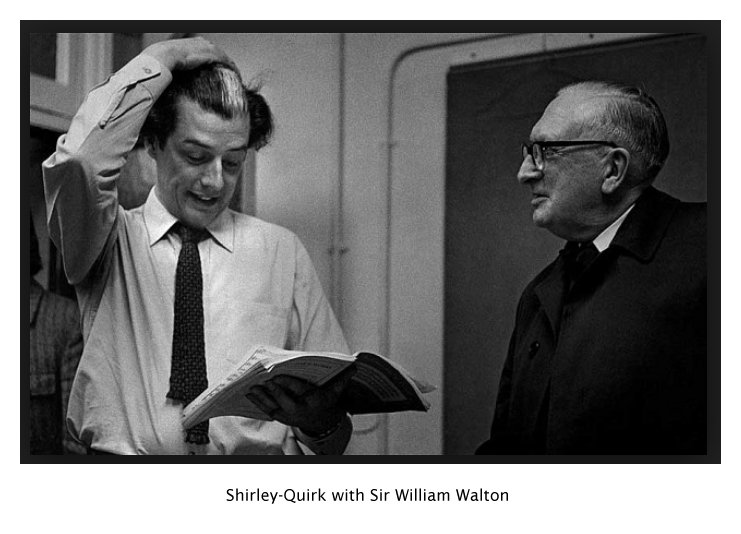

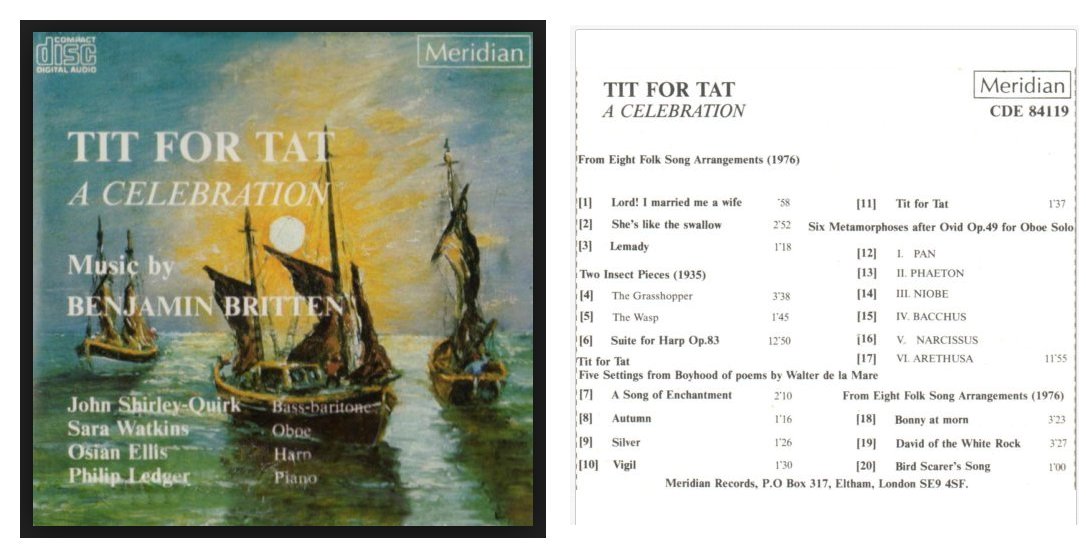

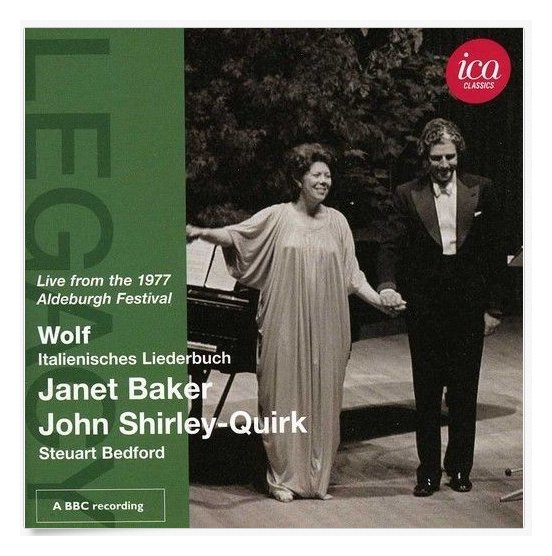

He also gave the premiere at Aldeburgh in 1969, accompanied by Britten, of the newly revised Tit for Tatcycle (five settings of Walter de la Mare), and sang in the first performance of Journey of the Magi(Aldeburgh, 1971), of which he was a dedicatee. The major choral works of Elgar, Walton [in photo below] and Delius, the songs of Vaughan Williams and the oratorios of Handel were particular strengths, but his repertoire also included Bach's Passions, Brahms's German Requiem, and German and French song, as well as operas from Mozart to Henze.

He entered the musical profession comparatively late. Born in Liverpool to Joseph and Amelia, he went to Holt school and gained a chemistry degree at Liverpool University (1952). After national service in the RAF, he taught chemistry at Acton Technical college, west London, and studied singing, first with Austen Carnegie, later with Roy Henderson. In 1961 he became a vicar choral at St Paul's Cathedral.

The following year he made his operatic debut at Glyndebourne as the Doctor in Pelléas et Mélisande. After a performance of Bach's Christmas Oratorioin Ipswich in 1963 he was congratulated by a stranger who had particularly admired his singing of "the D major aria". Unknown to him, Britten had been invited to hear him and this was effectively his audition for joining the English Opera Group, which he did the following year. That successful and creative relationship culminated in Britten's final opera, Death in Venice, in which he played The Traveller (who additionally takes the part of six "nemesis" roles: Elderly Fop, Old Gondolier, Hotel Manager, Hotel Barber, Leader of the Players and Voice of Dionysus).

Fashioning the latter roles – all harbingers of death – for Shirley-Quirk, Britten created a series of deft cameos with which the singer was eloquently to engage. Shortly after the composer's death he wrote affectionately of his time with Britten and his colleagues at Aldeburgh, remembering "vicious games of croquet, played to Red House rules, whirlwind table tennis which I was not quite quick enough to watch, Indian or China tea to choose from, and rich cakes for young and non-slimmers alike". The recording he took part in of Schumann's Scenes from Faust(1972) was the last made under Britten's baton. In 1975 Shirley-Quirk was able to offer the physically ailing composer a short holiday along the canals of Oxfordshire on his narrowboat.

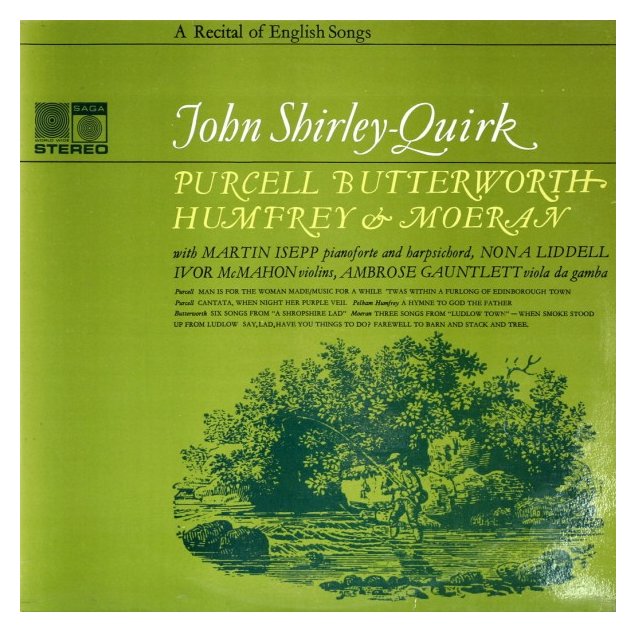

His extensive discography also included many of the staples of the English repertoire: Purcell's Dido and Aeneas, Handel's Messiah, Tippett's A Child of Our Time, Vaughan Williams's A Pilgrim's Progress and Delius's A Village Romeo and Juliet, as well as many of Britten's works and numerous songs. Elgar too loomed large in his career. In Adrian Boult's classic 1969 recording of The Kingdom, he brings to the role of St. Peter an appropriately rock-like authority but blended with humanity and warmth. Elgar's earlier oratorio The Light of Lifehe recorded twice, under Charles Groves and Richard Hickox. In both, his "I am the Light of the World" is a glorious affirmation, confirmed shortly after with a ringing top G where he fearlessly takes the higher option.

To his operatic incarnations he brought musical and dramatic intelligence. His Golaud in Pelléas et Mélisande, for example, explored the warmth of the character as well as his sadistic displays of jealousy. The genius figure of Gregor Mittenhofer in Henze's Elegy for Young Lovershe projected not as a "great man" but as an absurd, pretentious "little man". His Count in Le Nozze di Figaro(Scottish Opera, 1972) was curiously self-effacing, while in Basil Coleman's production for television (1974) he was less the aristocratic seducer than a thoughtful, frustrated intellectual – a portrayal that won considerable sympathy for the count. In Fidelio(Scottish Opera, 1977) his individual interpretation presented the prison governor Don Pizarro as neurotic rather than conventionally villainous.

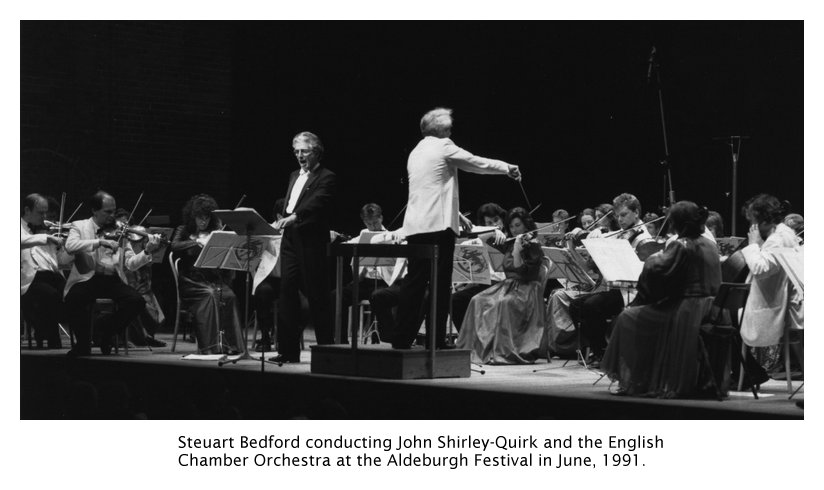

His Metropolitan Opera debut came in Death in Venice in 1974, and three years later he created the role of Lev in Tippett's The Ice Breakat Covent Garden. To his music-making in all genres he brought elegant phrasing and a superbly schooled tone, combining them to produce a distinctive delivery suffused with humanity. He was appointed CBE in 1975 and made associate artistic director of the Aldeburgh Festival in 1982. He taught at the Peabody Conservatory of Music in Baltimore, Maryland (1991-2012), and then at Bath Spa University.

His first wife, Patricia Hastie, died in 1981 and his second wife, Sara Van Horn Watkins, in 1997. He is survived by his third wife, Teresa May Perez (nee Cardoza), whom he married in 2009, and by two sons and two daughters. Another daughter predeceased him.

• John Stanton Shirley-Quirk, bass-baritone, born 28 August 1931; died 7 April 2014

-- Barry Millington, The Guardian [Photos added for this website presentation]

Most of the interviews I have done over the years are with a single guest, one-on-one. Occasionally, a second colleague (often the spouse) was included, and this is one of those happy events.

I had arranged to meet baritone John Shirley-Quirk in March of 1988 on one of my very infrequent trips to New York City. The wheels had been greased, so to speak, by a mutual friend, as noted at the very end of our discussion. I did not know, however, until I met them, that his wife, the oboist Sara Watkins would be along as well. Being a bassoonist myself, this meant an immediate cordiality of double reed players!

As often happens in this kind of situation, the two artists occasionally spoke between themselves, and I had the good sense to let them continue rather than interrupting with the next question.

They had just arrived in New York and were going to give a concert the following day. We began chatting immediately about the current state of affairs, and after they got all checked into their hotel, we sat down and had a wonderful conversation . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Vis-à-vis what we’ve been talking about, is there any hope for serious music in great cities in the late part of this century?

John Shirley-Quirk: [Ponders a moment] It seems difficult, doesn’t it? The financial constraints on music-making seem to be almost insuperable. Opera, particularly, has always been a great luxury, perhaps the greatest if not the most expensive luxury.

BD: Should opera be for everyone?

BD: Should opera be for everyone?

JS-Q: Why not?

It is in the other countries, isn’t it? I imagine it is in China, for example. I’ve never been to China, but I imagine that Chinese opera — whatever they call it — is a very popularist undertaking. I don’t imagine that it’s elitist.

Sara Watkins: I think that’s part of the problem, or why there might be a problem in serious music collapsing — not having enough funding because people think it is an elitist thing. Why should it be? It’s an artistic expression that anybody could understand if they get over their fear of it. That starts at a very early age. People hear Muzak [elevator music] all the time and they’re completely desensitized to listening and enjoying what they're listening to. How many people actually sit there and listen and enjoy Muzak?

BD: If they turn off to Muzak, then do they also turn off to real concert music?

SW: I think it’s very difficult for them not to.

JS-Q: I think they do. You’re trained to turn off, and it’s one of the great problems of being a musician in that you’re trained to turn on. You live in this Muzak-ridden world.

BD: So what can be done to specifically grab them?

JS-Q: To grab an audience? I used to think that was what one would have to do

— grab an audience. I’m coming round to the view that it’s much better to invite them to join you

SW: Exactly

— make them come to you. Would I bend over backwards or actually bend over forwards in more ways than one? I find that I’m working too hard psychologically as well as physically in a performance. There’s not enough space.

JS-Q: Space is very good. You should give every member of the audience the right to go into their own thoughts in a performance. They’ve not got to be grabbed; they’ve not got to think your thoughts at that very moment. They are allowed to have their own collateral train of thought.

BD: So then you have no expectations of the audience?

JS-Q: Yes, oh, yes. I do have expectations of the audience. I expect an audience to have done some homework to know something about what they’re going to listen to. In my case, if I’m singing in a foreign language, I would like them to know something about the text. If the best they can do is read the program notes beforehand, I would like them to have done that. So I do have these sorts of expectations. They may do it as soon as they sit down in the hall, but it’s still homework in some ways. But that’s not the only thing that I expect them to do.

SW: I expect them to come with an open mind...

JS-Q: Certainly I expect them to come with an open mind, but also to come with the willingness to take part. I think it’s very dangerous if the music is only performed on stage. Music has got to be performed within the audience’s minds as well.

BD: So it is a participatory act?

JS-Q: Yes, yes, I do think that very much. But it’s a participatory act that they have every right to say,

“Oh well, I’ve done enough of it now for a bit! Do I want to take some off?”

SW: I don’t think audiences realize how much their energy affects the performance and the performers. It isn’t something that can be gauged or measured, but it really exists.

BD: It’s a feeling you get?

BD: It’s a feeling you get?

SW: Oh yes, and most performers do really feel whether the audience is with you and responding or not, and it affects the performance. I’m thinking of one performance just recently of a particular piece where I felt as if the audience was yawning and just tuned out during our whole performance. It’s very hard then to be on stage and not feel, “God, they’re not listening. God, what are we going to do? We have got to do something extra. We really have got to go running out to the fourth row and grab them!” as you were saying. That changes the performance

JS-Q: Yes.

BD: And yet when they’re with you, the performance escalates.

SW: Oh yes.

JS-Q: Oh yes, absolutely.

SW: It becomes quite a different performance, yes.

BD: What about on a recording where you don’t have the audience there to feed off of. Do you perform differently for microphone than you do for the audience?

JS-Q: The trick is to pretend there is an audience.

SW: Or just to perform for yourself

JS-Q: You pretend there’s an ideal audience, or that you’re performing for the people around you. You’re not absolutely alone when you’re recording. There are other people about.

BD: Technicians and others?

JS-Q: Technicians or friends or the agents.

SW: It’s very difficult to keep the same tension from one take to the next.

JS-Q: I used to do a lot of recording of discs and for radio, the BBC particularly. Then I really did imagine an audience. I was singing into a microphone but I could sort of see through it, and there was this panorama of thousands or even millions of people listening at the other end. That helped me in the early stages, but once you’ve learnt a trick you don’t have to do that to such an extent.

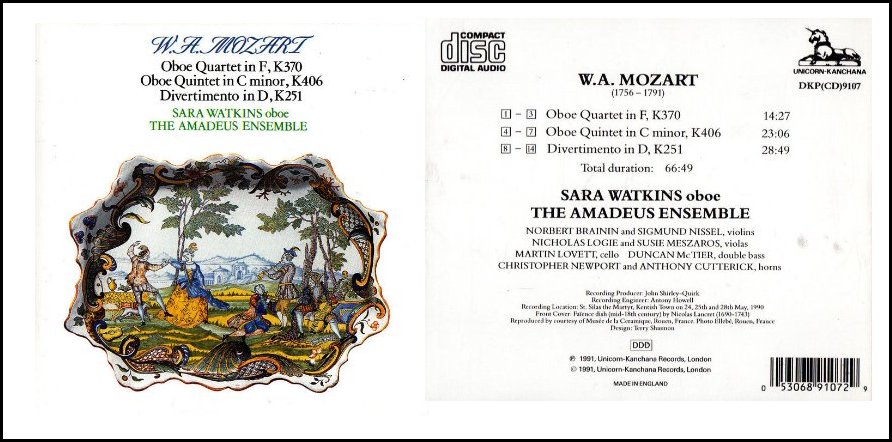

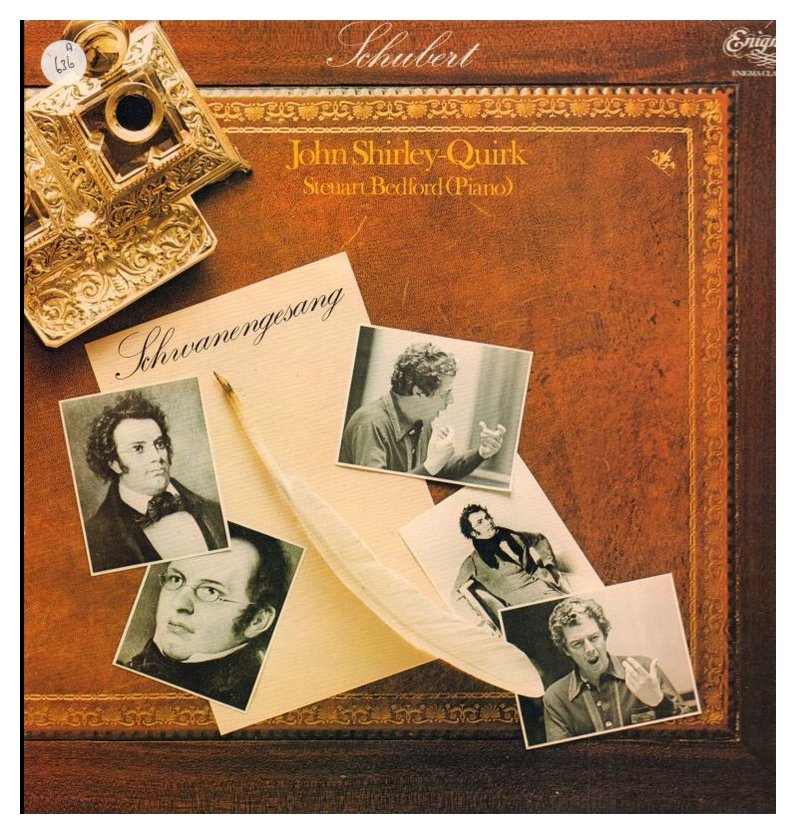

BD: What are some of the recordings that you’ve felt most happy with?

JS-Q: [Ponders a moment] I was very happy with the recordings of the Bach Cantatas, but I’m becoming less pleased with it as I grow older.

BD: [Surprised] Why? The recording’s the same...

JS-Q: The recording’s the same, yes, but I’m becoming less pleased with myself as I grow older. [Laughs] I think that I know more about music now, and that can affect the performance

BD: Does it bother you when someone comes up and says they love ‘such an such’ a recording which was made early on?

JS-Q: No it doesn’t because I’m still quite content with that early side of me. There are times when I still hear early recordings, and I think it sounds fresh and young and innocent and naive, and all those lovely things!

SW: Self-cindulgent! [Laughs] No, no, not you...

JS-Q: I don’t ever feel that I was notably self-indulgent as a recording artist, no. But I look at myself as through a glass

— distantly, if not darkly — and I see that it had qualities which I cannot now reproduce. But I do know that I could do it differently now, and it would be neither better nor worse, but certainly different.

BD: Are you still singing opera?

JS-Q: Yes!

BD: How do you balance your career

— opera and concerts?

JS-Q: Well, I’ve never done a lot of opera. I did most opera when Benjamin Britten was alive and writing, producing a new opera every two years or thereabouts. That was the bulk of my opera work.

BD: Was he writing with you in mind?

JS-Q: Eventually, yes, I am delighted to say he was.

JS-Q: Eventually, yes, I am delighted to say he was.

BD: Tell me about working with Benjamin Britten.

JS-Q: It was the most important relationship that anyone could have

— to be around a musician of that caliber — and not just a musician but a generous musician. He was very generous with his encouragement and enthusiasm, and in a very gentle way in teaching. To go to a working rehearsal session with him was like going to a university seminar in music. If you were open and receptive you could learn an enormous amount from him, but if you asked him a specific technical question he’d say, “Oh, I don’t know the answer to that!” You couldn’t ask questions very much.

BD: You just had to go and do it?

JS-Q: You had to go and listen and try to respond, and then do it. He would, in a very gentle way, reform your performance without saying very much at all. Working with him as an accompanist was extraordinary because he would completely reform his way of performing to suit yours, so that the performance you produced together was unique. That had never happened to me. For example, I did the Songs and Proverbs of William Blake. I know he did them with Fischer Dieskau, but I also know that when we did them together it was a totally different performance than he’d ever done with anybody else, because it had been worked out of our capabilities and how we felt about it at the start.

BD: What is it about the music of Benjamin Britten that makes it great?

JS-Q: [Ponders again] I think it’s that the passion of the man comes out in his music. That’s the best I can say.

BD: How many operas of his have you sung?

JS-Q: I don’t know. I haven’t really counted. Five or six?

BD: The last one wasDeath in Venice. Tell me about the multi-faceted character you portray.

JS-Q: Well, I have to tell you about his illness that was going on at the same time. Because he exhausted himself so much in writing it, it was obvious that he was ill-prepared for the operation he had, the result of which was the stroke which finally killed him. Once the music was in our hands to work at it, he was already in hospital, so the only time I had to talk with him about it was two visits to the hospital, just talking about the characters. He just gave me a few little clues about what he saw about the characters, but about a year before, he’d told me about the opera and he told me about the novella by Thomas Mann. I’d gone away and found it and read it, and he told me that he had this plan of six or seven characters. He didn’t know exactly how many it was going to be at that point. So I searched the novella for all the particular characters that I might have to portray, and I kept on coming across character after character and I thought, “Oh, I hope that’s not me. I hope I don’t do this one. I’ll never be able to be that character, never be able to find the form of portraying in this particular character.” Actually finding those characters was quite an interesting job. For one of them, Mr. Barber, the one that makes up von Aschenbach eventually, I actually discussed that character with my barber, my hairdresser. He said, “Oh yes, it’s always easy to tell another hairdresser. They’ve always got hunched shoulders!” So there it was. There is a barber immediately.

BD: Was that something Britten also knew?

JS-Q: That barbers had hunched shoulders? I don’t know. I don’t think he cared about that. I don’t know that he minded whether I had hunched shoulders or not. I did in those days. I think I’m losing them slowly!

BD: Did you accentuate that detail?

JS-Q: When I was trying to be the barber, I tried to hunch my shoulders, and produce this look.

BD: Is it especially difficult to put on so many different characters in one evening?

JS-Q: Well, it all happens so quickly. In the first ten minutes I have to be four characters in that opera, so each character can only be a quick sketch. You have to look for something that’s as characteristic as possible, that will put a stamp on each of the characters. I got another character from the costume design. They’d drawn one particular character with a particular pose, a particular way of holding his hands, so I used that. There was no time to build characters. They had to be almost lightening sketches, so once I’d learnt the technique of using each little sketch, then it wasn’t very difficult. What was difficult was the months of preparation, and finding the characters.

BD: If you came back to that part today, would you have to relook for those characters, or would you use the existing characters?

JS-Q: I would try to look around further, and see if there is any way I could make them more distinctive or less distinctive. There was even a criticism that on one occasion I had made too great a distinction in the characters. It wasn’t always obvious that there was the unifying part, which was supposed to be me. It wasn’t always obvious that I was always the same person being these different characters.

BD: So really all of these characters are different facets of a single character?

JS-Q: That is the point in both the novella and in Britten’s opera, yes. So there’s a danger in separating the characters too much.

BD: What other Britten operas have you done on stage?

JS-Q: Well, the first operas that I did at Aldeburgh at all were the Church Parables. The first was Curlew River, and from then the three in the series. The next one was Mr. Coyle in Owen Wingrave [seen in photo at right]. It was a television opera. I don’t know that it’s had very many performances over in America here.

JS-Q: Well, the first operas that I did at Aldeburgh at all were the Church Parables. The first was Curlew River, and from then the three in the series. The next one was Mr. Coyle in Owen Wingrave [seen in photo at right]. It was a television opera. I don’t know that it’s had very many performances over in America here.

BD: It was on the television, and I don’t know if it’s been revived since. It was conceived for the television?

JS-Q: That was conceived totally for television.

BD: Does it work on stage?

JS-Q: Yes, I think it does. I don’t know that it’s as successful as it might be on stage, and I also don’t think that it was as successful as it ought to have been for television, because the technical resources were not put at disposal for the proper treatment of this opera. Now a lot more film technique would have been used in producing it. It was a little too expensive to use in those days. It could be done quite differently now, and much better.

BD: Tell me a bit about the Parables. I know them on recording, but how do they work in performance?

JS-Q: They are incredibly powerful. They always did take place in churches, so there’s already an aura around them at performance. It’s as though they were at a service, or the old miracle plays in that a troop of so-called monks process into the church in front of the audience dressed as the various characters. They put on masks to show the different characters, and then made the performance, and finally take off their masks and cloaks and go back to being monks and process out again. So this very formal and religious structure gives a very somber seriousness to the parables.

BD: Are they religious works, or are they theatrical works.

JS-Q: They’re theatrical works on religious subjects. Just as the miracle plays in England and Europe were theatrical works on religious subjects.

BD: All of these works are in English, which is the original language. Do you feel a very close communication with the audience, knowing that they’re understanding every word?

JS-Q: Oh yes, of course.

BD: Do you work especially hard at your diction because it’s English?

JS-Q: I don’t think I work any harder at English diction than I do at any other language diction. English is the hardest language to sing well.

BD: Why?

JS-Q: Because it’s such a flexible language. We don’t have pure vowels. Every vowel must be a diphthong, otherwise it doesn’t sound English. You’ve got to balance that diphthong right throughout the course of quite a long note if necessary, and yet you still must keep the balance of the word in mind. In other languages it is quite easy. You can just get onto the open vowel and stay there as long as you like. But in English you daren’t do that, so you have to keep your ear balancing not only the whole word but the balancing of the diphthong, the changing of vowel.

BD: Let me ask the

‘Capriccio’question. In opera, where is the balance between the music and the drama?

JS-Q: My answer would be exactly the same as Strauss’s!

BD: Your wife plays oboe, and you’re trying to incorporate her to as much of your life as you can, obviously.

JS-Q: Yes, indeed.

BD: It is special then when the two of you are performing together

— perhaps more special than when either of you are performing separately?

JS-Q: Yes, I think so. It’s tremendous to get up on stage and have a superb musician beside you.

BD: Have you had to teach her about the style of Benjamin Britten?

JS-Q: That sounds a little pedagogic! I don’t teach her, but she’s asked me a few questions about it!

BD: Then let me turn it around. [To Sara] What have you learned about Benjamin Britten from him? [Both laugh]

SW: The expansiveness of his music and the idea that you can’t take everything literally, particularly about the Metamorphosesfor oboe. He’s sort of given me permission to follow my instincts... not just my instincts but my little perception that I might have looking at the music. He’s given me a lot more courage by saying, “Yes, Ben would have liked that!”

BD: Does that then carry over and let you feel that, yes, Bach would have liked that?

SW: No.

BD: Why not?

SW: It’s a totally different style.

BD: I mean about trusting your instincts.

SW: Yes, I suppose. That’s one thing I like about performing new music, especially music that has been composed by good composers. There is a lot of new music that I don’t enjoy playing. Because of the relationship with the composer, the vicarious pleasure I get out of that is enjoyable. I don’t feel as if I am creative in just reproducing their music. I enjoy seeing what they’re up to and picking their brains to understand a little bit of what went into composing the piece. I suppose that gives me a lot more courage to then go back to Bach and think he probably wanted more freedom here after all.

BD: What really constitutes great music?

SW: Good architecture, balance, color. Bach is an incredible architect. If you look at just one aria, you see the structure underneath it all

— not just the beautiful melody and the beautiful harmony but the incredible perfect architecture. That’s what I’m really the most in awe of in great music is this seeing the bones underneath it all.

BD: Do you agree with that?

JS-Q: Yes I do, and more and more. This is something I’ve learned from being around Sara. I was far more an instinctual musician until I met her, and it’s her excitement at discovering the architecture that has enthused me into looking for architecture much more, and being aware of it, and I hope responding to it.

BD: We talk about great music. Should there be a place in the concert hall for music that is not quite great?

JS-Q: Oh yes, oh definitely.

SW: I don’t think we are able to judge right away whether or not something is great anyway.

BD: Who should judge

— if anyone?

SW: Generations beyond us. For instance, take the Metamorphoses. I’ll go back to that as being a really great piece for oboe. The first time I looked at the piece I thought,

“Oh, well this is nice. A little ditty here and a little ditty there!” I really didn’t see the greatness of it. Who was I to say five years ago this was great music? I didn’t understand it, but you grow with the music that you see and hear. You’re not necessarily able to judge right away that it’s great or isn’t. Maybe your performance is lousy! [Laughs]

JS-Q: You did answer your own question

— should anybody judge — but of course one should judge. Every member of the audience should judge because they’ve got every right not to like something. Even to be told that a piece of music is ‘great’ doesn’t mean that it’s enjoyable! That may be the performer’s fault or maybe the auditor’s fault that he does not enjoy it. An example of great music, which I don’t happen to enjoy very much...

SW: [Interrupting] Strauss!

JS-Q: Strauss, exactly.

JS-Q: It offends me. It hits me below the belt, and so I get offended by it. I recognize that it’s probably great, but I don’t like it!

BD: So then you turn down any offers to do it?

JS-Q: On the whole, or at least I think very, very hard, and so far I’ve managed to avoid most of the offers to date. [Laughs] In fact the only Strauss I’ve ever sung was at Glyndebourne where I did a little bit in Capriccio, but I don’t think that really counts. Then I did the Music Master in Ariadne auf Naxos here at the Met some seven or eight years ago, and lo and behold I enjoyed it very much indeed!

SW: You like the Oboe Concerto?

JS-Q: I do, absolutely. That’s a very classical but it has a great classical structure.

SW: Yes, it is very Mozartian.

JS-Q: I don’t feel that my privacy is infringed by the Oboe Concerto.

SW: You’re not manipulated by Strauss?

JS-Q: That’s the word. That’s what I mean. I don’t feel manipulated.

SW: In other works you think you’re going somewhere and you never quite get there. Then he turns off in a totally different direction.

JS-Q: Yes, yes!

SW: Oh, I love that because I still think there is form underneath it all! [Laughter all around]

JS-Q: Well, there you go! Yes.

SW: He pulls it apart as much as he can possibly pull it apart and still have form. I love it!

BD: Over your career you’ve been offered many things. How do you decide which roles you will accept and which roles you’ll either postpone or decline?

JS-Q: [Ponders] I don’t know how I make those decisions, really. Obviously if it’s something I feel I wouldn’t do well and it’s not in my nature to do or not in my voice to do, then it’s quite easy to say, “Oh, no! No, that’s not for me now, thank you very much!” You just pass on it. So I don’t remember the process because it seems so obvious. If someone came and asked me to sing Wotan I’d say, “Oh, thank you very much for the invitation. That’s not for me. Good-bye!”

JS-Q: [Ponders] I don’t know how I make those decisions, really. Obviously if it’s something I feel I wouldn’t do well and it’s not in my nature to do or not in my voice to do, then it’s quite easy to say, “Oh, no! No, that’s not for me now, thank you very much!” You just pass on it. So I don’t remember the process because it seems so obvious. If someone came and asked me to sing Wotan I’d say, “Oh, thank you very much for the invitation. That’s not for me. Good-bye!”

BD: Would it be,

“Thank you very much,”or would it be “You’re out of your mind!”?

JS-Q: Actually I remember an occasion when Britten asked me to do a role that I really felt was wrong for me, and that would have been Sarastro. I understood why he wanted me to do Sarastro. He saw in me some of the character of Sarastro that he would like to see on stage. So I didn’t go and say, “You’re out of your mind!” [Laughs] Not to Britten, thank you very much. I had to think carefully how to refuse as graciously as I knew.

BD: Did you manage?

JS-Q: I managed, yes. I said I would be miserable, and he understood and accepted that.

BD: What other kinds of operatic parts have you done in general?

JS-Q: In general, I’ve done Mozart and twentieth century opera. I’ve left out virtually all the nineteenth century repertoire.

BD: Tell me the secret of singing Mozart.

JS-Q: Ah! When I’ve discovered it, I’ll tell you! [Laughs] It’s discipline...

SW: [Interjecting] Simplicity!

BD: ...but then discipline is the secret of simplicity or vice versa. I don’t know which way round that is. I think it’s vocal and musical discipline

SW: Elegance!

JS-Q: Yes, elegance. That’s right. And twentieth century opera starting, withPelléas through to Wozzeck to...

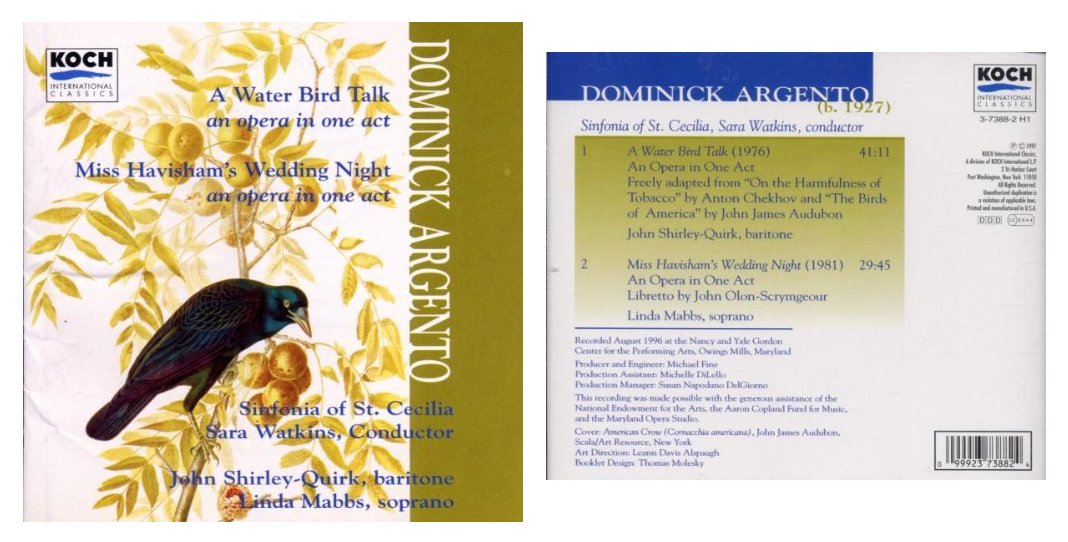

SW: Argento!

JS-Q: I did the first English performance of A Water Bird Talk, and that is an absolute delight. That’s something we keep on trying to revive. We’re doing some performances next year, probably at the Cambridge Festival. We were hoping that we were going to do it again this summer and that Sara would conduct, but unfortunately the finances intervened... or the lack of.

[As can be seen in the photo below, they recorded this work about eight and a half years later.]

SW: We’re in the process of having it translated into German so we can do some performances in Germany and Austria.

BD: In Pelléas, you were Golaud?

JS-Q: I’ve sung everything but Pelléas inPelléas in my time. I started off life as the Doctor, and I understudied Arkel and actually sung one performance of it. But Golaud, yes.

BD: Tell me about Golaud.

JS-Q: Golaud can be summed up in his very first words

— “I will never get out of this forest!” That’s it, and he’s seems so entangled in his own forest that he will never get out, poor soul!

JS-Q: Well, inPelléas no one gets out, do they? The only people who do get out are the people who die. That is Pelléas and Mélisande eventually. They’re the only ones who get out. Everyone else is left in their misery. Should Golaud get out? I think he deserves greater happiness than he achieves, but he’s not built for happiness.

BD: What would have made him happy?

JS-Q: I don’t think he knows.

BD: Is that what he’s doing

— searching for happiness?

JS-Q: I think so, searching constantly.

BD: Why does he think he will find happiness with Mélisande?

JS-Q: I don’t know that he does actually.

BD: Then why does he take her?

JS-Q: Just because she’s so beautiful, which is the worst reason for marrying anybody, I suppose!

BD: Is that an opera that can be translated?

JS-Q: I would hate to see it translated. I would hate to hear it translated, so I don’t think so. I believe it is done in German in Germany, but it is purely prose and it is pure recitative right from the start to finish. I cannot conceive of it coming into any other language with anything like the same impact.

BD: What about the Britten operas

— do they translate well?

JS-Q: Yes, I believe they do. I’ve never actually heard any but I know they do translate quite well.

BD: You’ve recorded Britten and Bach, and Don Giovanni. What kind of rogue is he?

JS-Q: I don’t think he’s a rogue. I have a different view of Giovanni than most singers, in which case it doesn’t actually work on stage. I think he’s also trapped in his own incessant search.

BD: For what?

JS-Q: He doesn’t know. It’s just pure gratification in his case

— or at least he’s settled for gratification, as distinct from real satisfaction perhaps.

BD: Is that a good role for you to portray?

JS-Q: I’d like it be. I don’t know whether it really is.

BD: What more can you do to make it better?

JS-Q: Learn to sing Italian faster! [Both laugh]

BD: When you’re on stage doing an opera, are you portraying a character or do you become that character?

JS-Q: I think you always seek to become that character, but you’ll never reach that condition because there’s always too much distraction

— like watching the conductor, for example. You can’t become a character, you can only portray. But what I particularly try to do is seek that character in myself, or if I can’t do that, find that element in somebody else that I know quite well so as to build a base and make the character believable to myself, and therefore I hope to the audience. The hardest character I’ve ever found, and the one which I was very worried about was the Strolling Player in Death in Venice. I didn’t know that I could become vulgar enough in public. I might be very vulgar in private, and I didn’t know that I could allow myself to be vulgar enough in public. What I didn’t know was that I was going to have Sir Frederick Ashton as the choreographer to help me. So it was wonderful. He helped me enormously with that particular character. But apart from that, I found the one most difficult to believe in was Mittenhofer in Henze’s Elegy for Young Lovers. [See my Interview with Hans Werner Henze.]

BD: Why?

JS-Q: There’s a supposed poet who is prepared to sacrifice anyone, including his young mistress and his favorite godson, in order to get the inspiration to write another poem. He will do anything and sacrifice anything and anybody on the altar of creativity or art. I didn’t know where I was going to find that character because I didn’t think I could find it in myself. It would be invidious of me to say where I found it, but I did find elements of that character, and obviously the Mittenhofer is a distillation of those elements. I found it in the ruthlessness of a creative artist, because there has to be a ruthlessness, perhaps, in any artist, really. And if that is just somewhat supplemented and created and becomes blown up, then it becomes Mittenhofer. That’s how I came to terms with that particular character.

BD: Was Henze any help at all in that?

JS-Q: Henze was actually producing on this occasion, and in between writing it and producing for Scottish Opera, he had completely changed his politics, and it also completely changed his views of Mittenhofer. Here was I, searching to create a Mittenhofer that was credible, at least to myself, and Henze was looking simply to make a buffoon out of his character.

BD: So it was schizophrenic?

JS-Q: I became so, yes! I’m not sure that we really found ourselves in this.

BD: Did you ever want to go to him and just say, “Let your character alone!”?

JS-Q: Yes, I did, but I didn’t feel confident enough to do so, I’m afraid. Perhaps I would be able to do so now, but at that stage I wasn’t self-confident enough.

BD: Since Britten’s death, have you learned other works of his that he didn’t teach you?

BD: Since Britten’s death, have you learned other works of his that he didn’t teach you?

JS-Q: Sadly, no, I haven’t had much opportunity or cause to look back at any of his other stuff. He wrote very little for baritone of course because he had such a wonderful medium for his songs in Peter Pears. It’s a good question! I’ll have to think why have I not searched further.

BD: In performing Britten or anything else, where the balance between the artistic achievement and the entertainment value?

JS-Q: It changes constantly. Entertainment is an artistic achievement alone, but I don’t think I seek to entertain.

SW: What does

‘entertain’ mean?

JS-Q: I suppose it means to divert the audience for an hour or so and send them out different then they came in.

SW: Like it would be to just ‘educate’? Does ‘entertain’ mean have a good time? What do you mean by entertain?

BD: I guess that it’s a little more frivolous

SW: Aha.

BD: Do you seek to educate every concert audience and every opera public?

JS-Q: No, I don’t seek to educate. I think I did, but then I used to be a teacher and it was a habit I found difficult to lose, this seeking to educate, but I don’t now.

BD: What do you see as the ultimate purpose of music in society?

SW: An expression of something that we can’t talk about. Something that is non-verbal.

JS-Q: It’s an expression of the inexpressible, and it is a communication. It is a communication and when you do manage to communicate with so many thousands of people, it’s a great entertainment!

SW: It’s a connection among people...

JS-Q: Yes, yes.

SW: ...and the qualities that make us all human. When you don’t feel that connection with an audience, you start feeling you have to stand on your head! It is what we were talking about earlier when you don’t feel as if you’re connecting....

JS-Q: ...and then you’re trying to entertain

SW: Yes.

BD: And then you start losing it all together?

JS-Q: Indeed, you can unless you recognize what you’re doing quick enough, and draw back.

SW: The whole nature of standing up in front of an audience is very curious to me anyway, because you’re directing everything towards the audience when in fact your whole body should be performing, not just the front of you. It’s very tempting to just have the front of you perform, in which case you’re really not communicating, not using your body.

JS-Q: You’re just a cardboard cut-out!

SW: Yes, yes! You’re not three-dimensional, and that comes across to the audience, so that’s another reason you don’t want to be towards the audience. You want to feel as if your whole being is three-dimensional, and your whole being is playing this music. The audience happens to be out in one direction, but...

BD: Would you prefer theater-in-the-round?

SW: No, because the instrument tends to be directional.

JS-Q: And people are directional! I don’t particularly like theaters-in-the-round, although many performances are done in the round and I think they’re very valid. I’m talking about concert performances.

SW: I think acoustically it’s better having the audience in the direction you’re actually pointing your instrument or opening your mouth, but psychologically you have to feel as if the whole of you is engaged, not just the front of you. It’s a hard thing to do. There is a lot of pull from the audience.

BD: Is performing fun?

JS-Q: Sometimes! If it’s going well, it’s great fun. If you have someone like Sara beside you with whom it can be fun, then it is. It’s great fun.

SW: Or it can be very lonely.

SW: Or it can be very lonely.

JS-Q: Yes, it can be very lonely

SW: Places like that are where you feel naked.

JS-Q: And it can be very uphill if you’re not in good form, or there’s something wrong. Perhaps the hall is unresponsive or the piano is out of tune...

SW: ... or your reed is lousy!

JS-Q: I don’t know about that! [Laughter all around]

BD: Do you ever wish you could take a small knife and scrape the voice just a bit like she does with her reeds?

JS-Q: I have that feeling quite often.

SW: When my reed is lousy it is uphill, and it’s not fun then.

JS-Q: No, it would have to be fun. No one in their right mind would go through the agony of preparing for a performance if it wasn’t fun in the end.

BD: I’ve often been told that musicians are not in their right mind.

JS-Q: I think you’ve been told quite correctly! [More laughter all around] No, you have to be a lunatic, you really do.

BD: You have to have a big drive inside of you to go through it and come out the other end and still want to do it again.

JS-Q: You have to have this great desire to communicate, and a great desire to use music as this means of communication to go and want to do it; to show other people the delight of a particular piece of music, or the misery or whatever it is. But you must delight in showing this.

[At this point we stopped momentarily and they showed me their new CD, Tit for Tat, which is pictured above.]

BD: This is your first record together?

JS-Q: Yes.

BD: And you have another coming out?

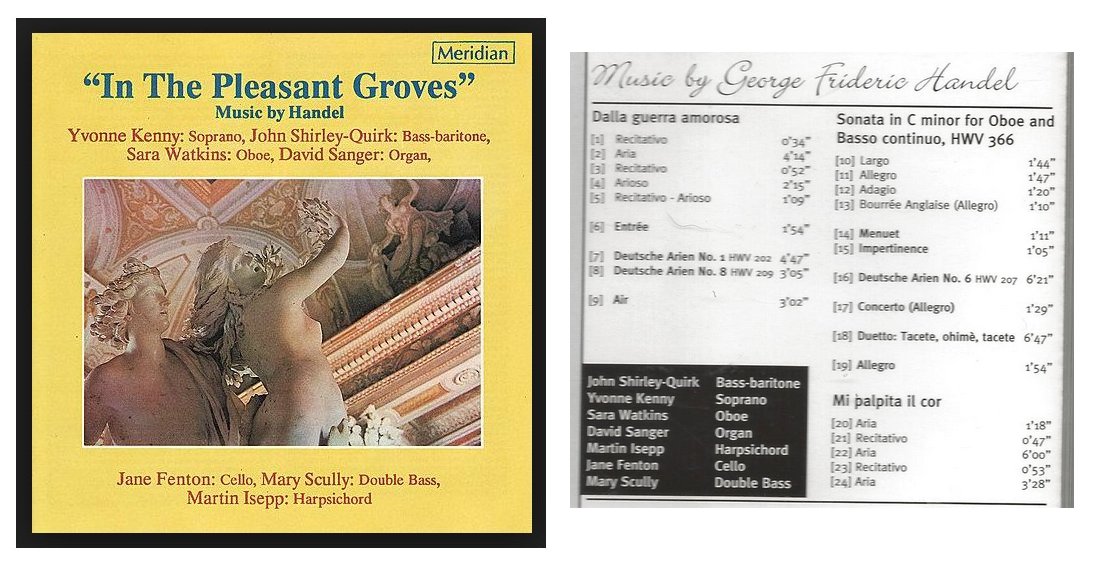

SW: Yes. All Handel

— sonatas, cantatas, arias, with the soprano Yvonne Kenny in addition to John.

BD: [Unable to resist] Where you able to ‘handle’ it correctly? [Sara bursts out laughing at the pun]

JS-Q: Well, we hope so! [Laughter all around] I think that’s going to be fun too, the Handel record.

BD: Have you already made it?

SW: Yes.

JS-Q: It’s made.

SW: Yes, we finished editing it.

JS-Q: We’ve finished editing it. That is the delight.

SW: That’s the torture. The editing is the torture, not the making the record.

BD: How to decide which takes to use?

JS-Q: Yes, that is the problem, deciding which takes!

SW: Oh yes takes are awful!

JS-Q: But there are no edits with this one, so we had to go away and think about it again.

BD: At what point does the cut-and-paste become fraudulent?

SW: When it doesn’t work!

JS-Q: At no point because the record is as such an artificial construction. Performance is the thing, and performances are imperfect. Gramophone records are

‘perfect’, whatever that means, but at least you aim at perfection. You cannot get perfection from performance, so you have to use the cutting technique.

SW: I think the criterion is if the collage that you’ve come up with does not produce a totality that’s believable...

SW: I think the criterion is if the collage that you’ve come up with does not produce a totality that’s believable...

JS-Q: Believable, yes.

SW: ...then it’s fraudulent. Then it’s just a bunch of scotch tape.

JS-Q: Yes. It’s fraudulent if it doesn’t work.

SW: Yes, but if you’ve actually produced it by putting various things together and produced something that makes sense, then...

JS-Q: It’s like any crime

— if you get away with it, you’re not guilty!

BD: Making records is a crime???

JS-Q: Well...

SW: I was amazed. About twenty years ago, my first experience with the record making processes was playing first oboe in the Chicago Symphony doing The Rite of Spring by Stravinsky with Ozawa. I was still a young upstart, and I thought we’d start at the beginning and go to the end. I was startled when we were told to go to measure 453 and we did ten bars. Then we went to measure 227 and did eight bars. I was aghast, but then in hearing the actual record, I thought that’s fine.

BD: It works?

SW: Yes, but I was disillusioned. That was the beginning and the end for me.

JS-Q: Whereas when Britten recorded, it was always in long spans. He would not make small takes. I don’t think he ever patched. By patching I mean rather distinct from editing. Patching meaning going back into the studio and just recording so many bars again.

BD: So he would do two or three long takes and then patch from amongst those?

JS-Q: Yes, from amongst those bars. One notable exception was when we were recording the St John Passion. I was singing Pilate, and every single session either the Christus or I had a cold, so we never actually got together. I remember on one occasion, because I had a cold at that time, having to conduct the recitatives for Pilate, and I had to go and put them back in later. So there was patching with a vengeance, but we had to. That was the only way which we’d actually get it down on record.

BD: And it worked!

JS-Q: It worked, yes, in a sort of fashion! Back to whether a thing is fraudulent or not, the answer is not with patching. If the performer has done his her homework and has a concept of the whole piece, then you can go in and do little patches because you have in your mind, “We have got to this particular point, and this is how is goes!”

SW: This is how it fits in.

JS-Q: This is how it fits in! So an experienced performer can go and record in that way, as you were saying Ozawa did because he obviously had the complete thing in his mind

SW: Oh yes, he certainly had it all worked out, and it worked.

JS-Q: So there is nothing fraudulent in that case about the end result, just that it happened to have been recorded in different phases.

SW: Somethings you just can’t record that way. In our Handel record we had to do a lot of movements just straight through as there was no place to patch.

JS-Q: That’s right, yes.

SW: So we were stuck. [Laughs]

BD: Do it right, and if it wasn’t right do it again!

SW: Right, yes.

JS-Q: Do it again, yes, exactly.

SW: And that’s very difficult.

BD: How do you keep the energy up for each take?

JS-Q: Well, the answer is you don’t! You have to get rid of that take and go have a cup of coffee or chamomile tea. But the most annoying thing is when you get takes and they’re ruined by extraneous noise

BD: Such as a chair creaking?

SW: Traffic!

SW: Traffic!

JS-Q: Traffic.

SW: Birds!

JS-Q: Or birds, or...

SW: Airplanes!

JS-Q: ...airplanes.

SW: Radiators!

JS-Q: Yes, indeed radiators suddenly started to go ‘bang’.

SW: Some of the best takes sometimes were ruined, and you don’t know that until you actually start editing!

JS-Q: Yes. We had a loose floorboard in our Handel recording, which we could not find. We couldn’t decide who was moving it.

SW: At one point I had to stand on three pillows because the producer thought I was the culprit! So I was playing the oboe standing on them. It’s ridiculous. We finally discovered who it was.

BD: What did it turn out to be?

SW: The cellist!

JS-Q: The cellist had her spike in one particular board, and whenever she particularly put an extra bit of pressure on, that board would bang. And of course that noise transmitted through into the microphone.

BD: So you weren’t really hearing it in the hall?

SW: Oh no.

JS-Q: Not at all.

SW: And only on one particular set of earphones. So it was very, very difficult to detect who was doing it.

JS-Q: And it slipped through one entire movement because the person who should have been listening on those earphones wasn’t. Somebody else was listening and didn’t hear it, so it was a near disaster when we went to edit it. We lamented,

“Oh my God, is there anything without this noise???”

BD: Do you like doing your own editing or would you rather leave that to someone else?

SW: I love it and I hate it. It’s excruciatingly painful, but I really like being in charge of what I want to hear and what I don’t want to hear. I would not like somebody else do it. John and I do it together, which is nice.

JS-Q: This has been quite a new experience producing it and then editing it because I’ve never done any editing before. It was quite another aspect of the whole process. It’s fascinating.

SW: I love editing John’s pieces. I have much more difficulty editing my own. In that respect I’m happy for John’s little-less-subjective approach to what he hears from me. But I still like to be in charge of making the final decision because I know what I wanted to hear, and nobody else knows that necessarily. Somebody else’s decision may completely change the whole shape of what I was trying to do.

BD: I wish you lots of continued success with this endeavor.

JS-Q: Thank you.

JS-Q: Thank you.

SW: Thanks!

BD: Thank you for spending the time with me today. It’s been a fascinating discussion.

SW: Oh, I really enjoyed it.

JS-Q: What a wonderful set of questions!

SW: Yes, really. It’s very unusual to get such.

JS-Q: David Gordon warned me! [See my Interview with tenor David Gordon.]

BD: What did David say, I’m curious!

JS-Q: I wouldn’t dream of telling you! [Everyone laughs] But you were well up to his warning!

SW: Yes.

JS-Q: No, it was amazing.

SW: It was unusual to get such intelligent and sensitive questions.

JS-Q: Provocative questions!

SW: Provocative, yes.

JS-Q: Very much so! Thank you very much indeed.

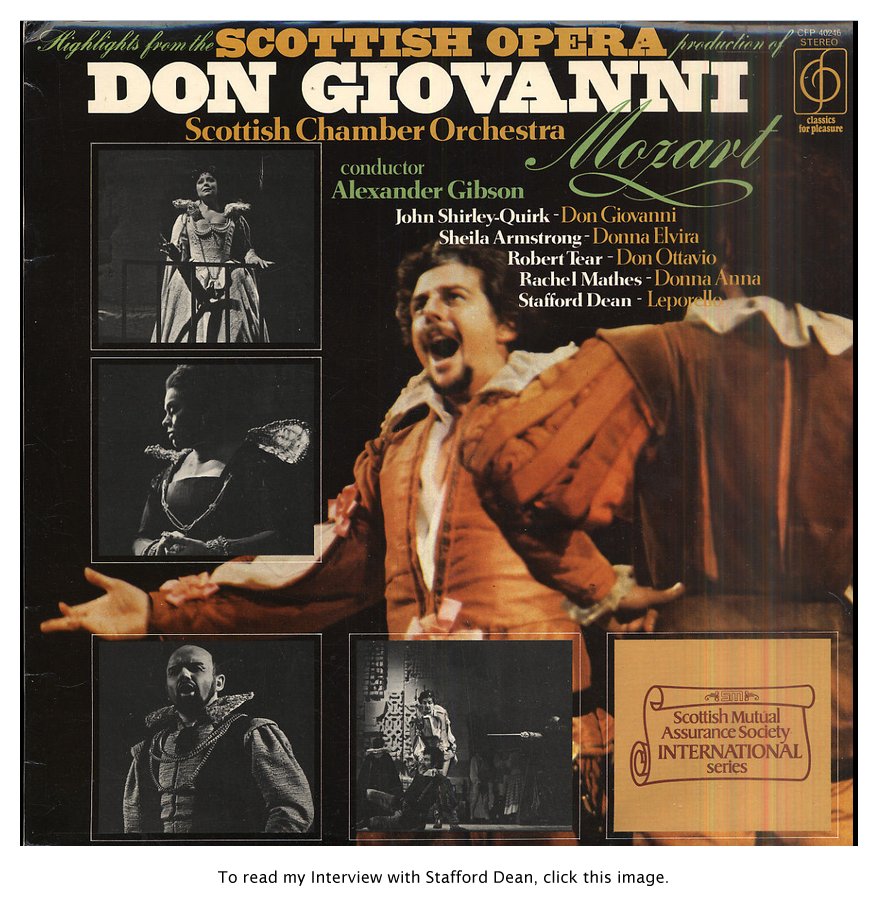

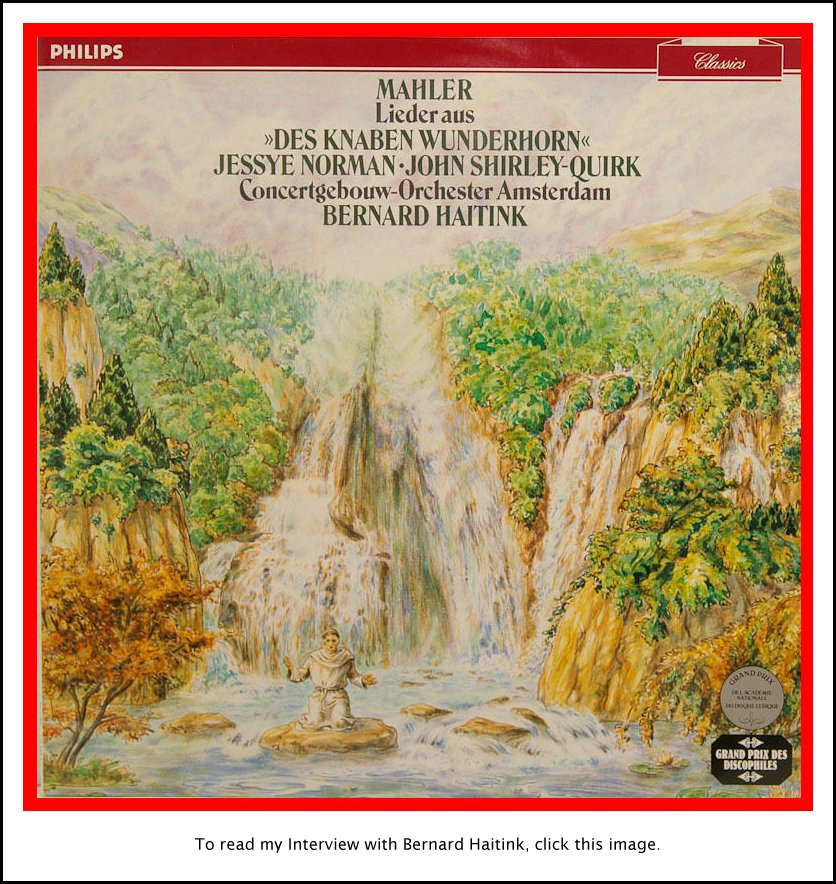

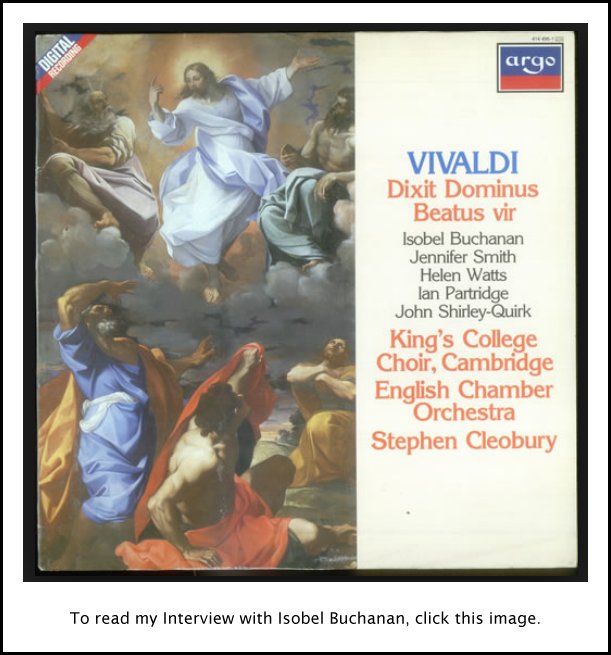

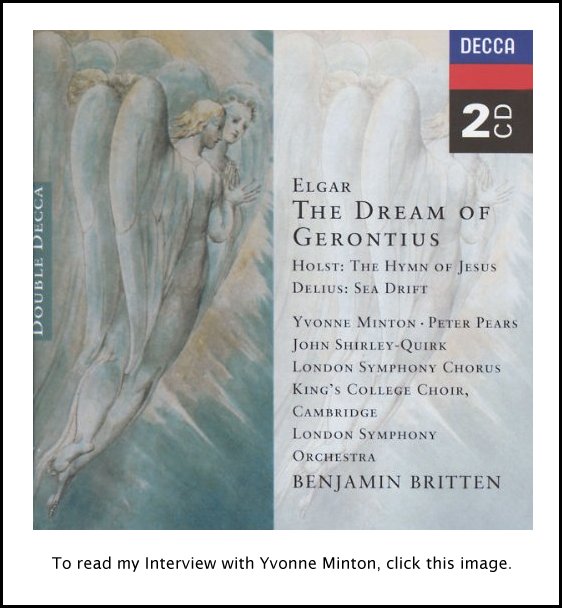

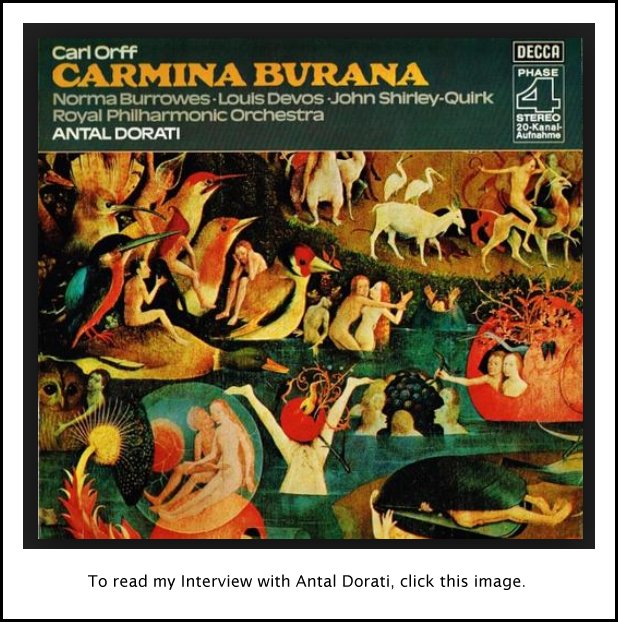

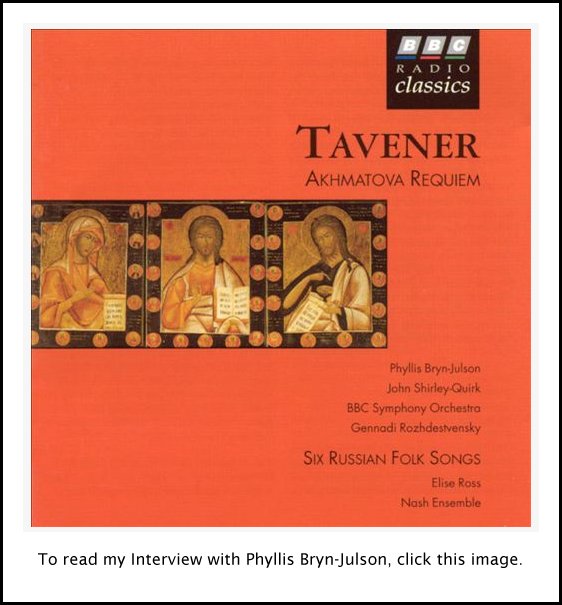

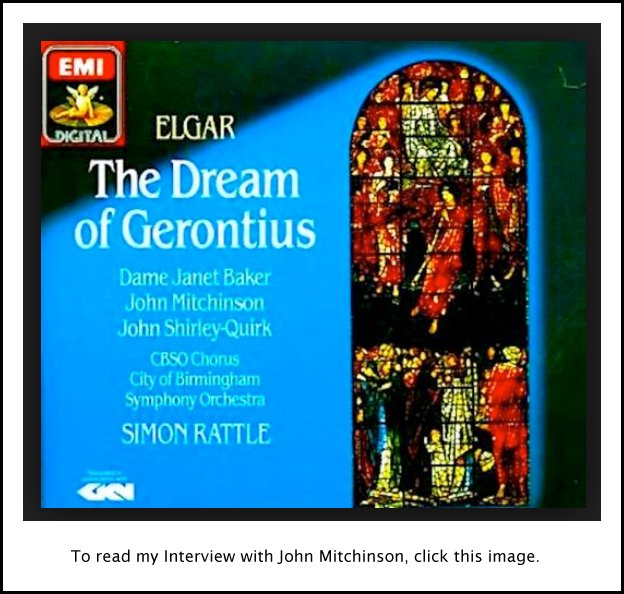

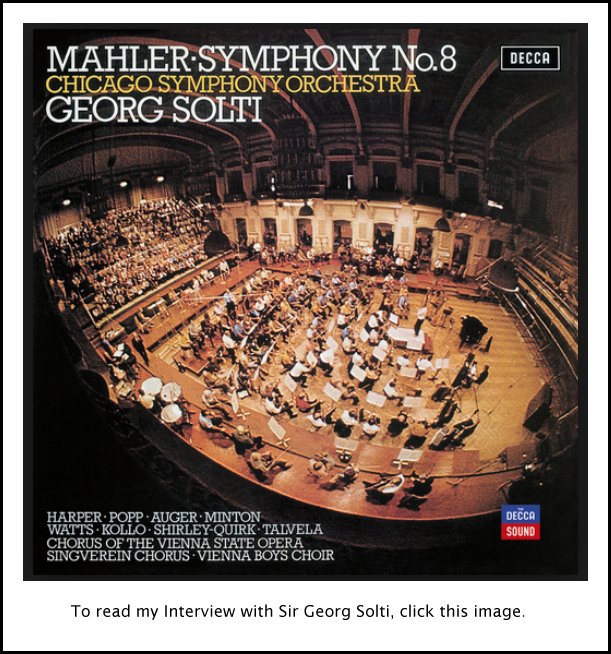

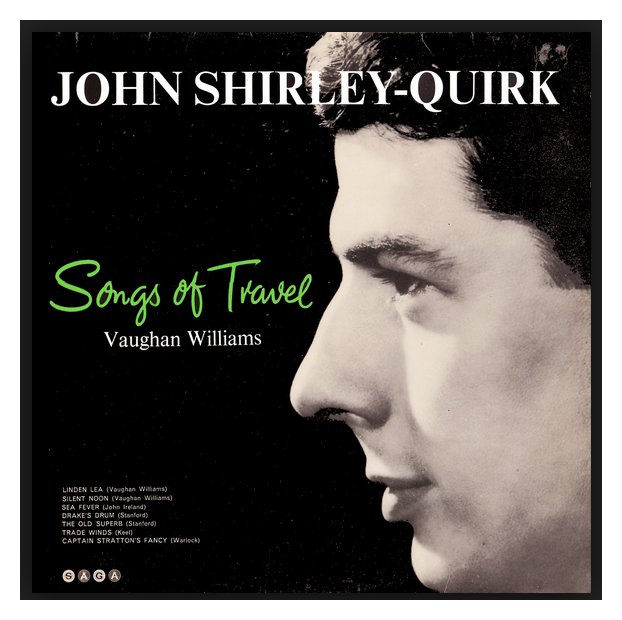

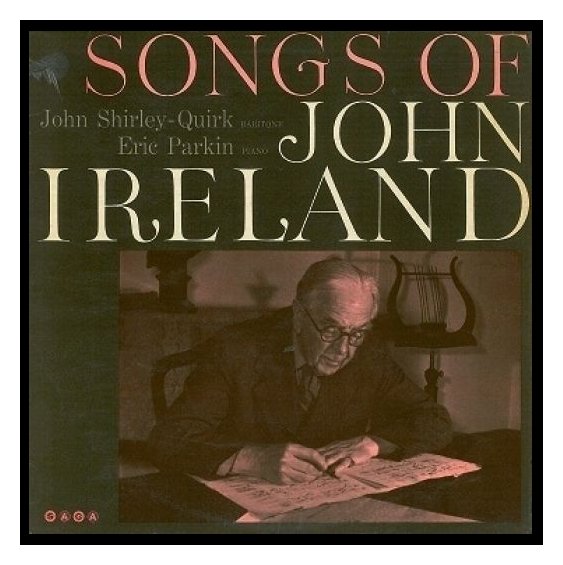

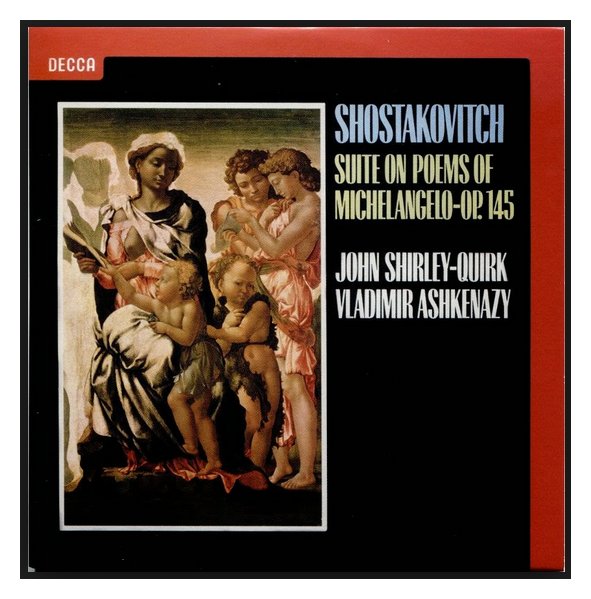

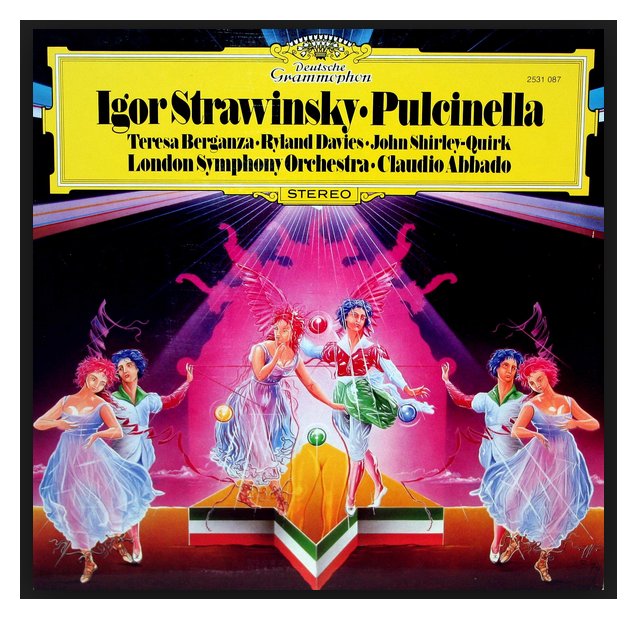

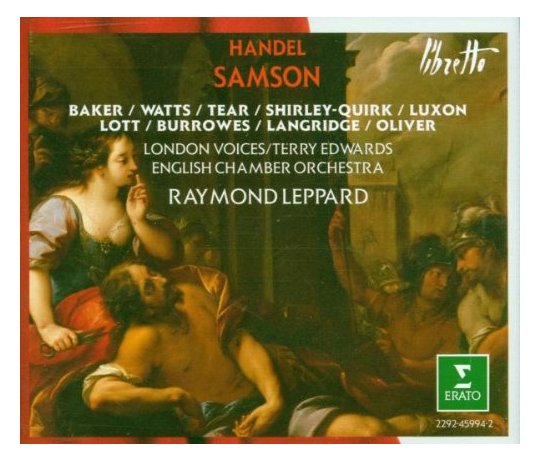

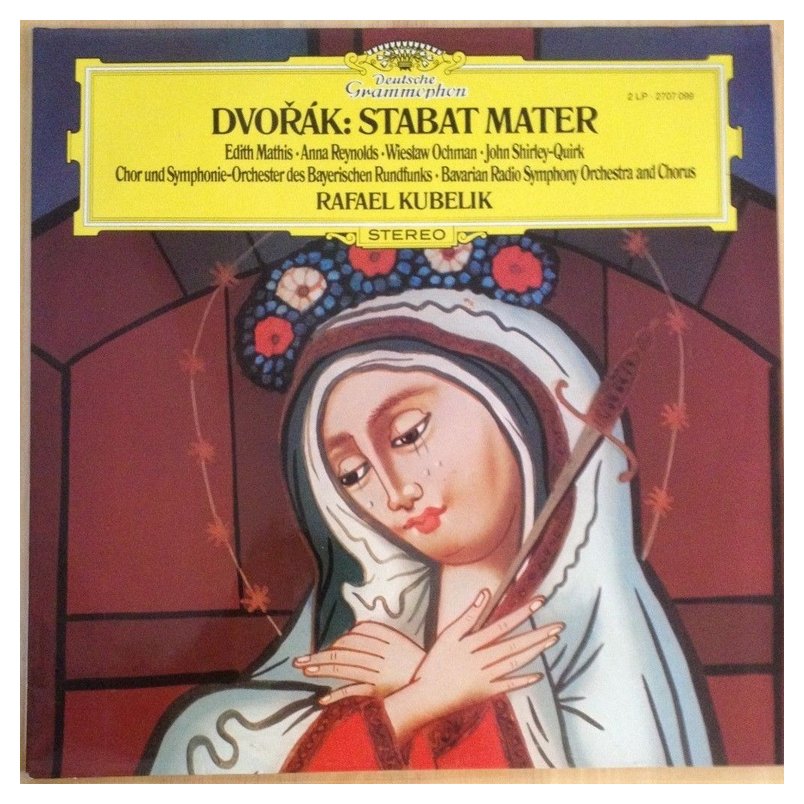

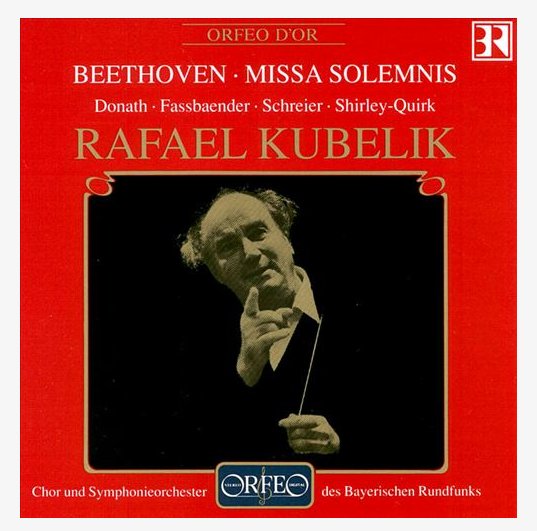

John Shirley-Quirk left a large legacy of commercial recordings.

Here are just a few which also happen to have some of my other guests . . . . .

To read my Interview with Teresa Berganza, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Ryland Davies, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Claudio Abbado, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Benjamin Luxon, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Felicity Lott, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Norma Burrowes, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Raymond Leppard, click HERE.

To read my Interivew with Anna Reynolds, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Wiesław Ochman, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Helen Donath, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Brigitte Fassbaender, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Peter Schreier, click HERE.

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in their hotel in New York City on March 24, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1991 and 1996. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award- winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his websitefor more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mailwith comments, questions and suggestions.