Phyllis Bryn-Julson Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

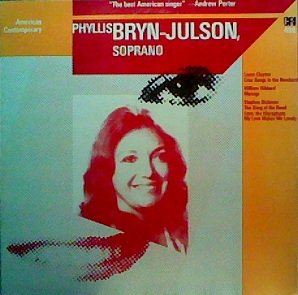

Soprano Phyllis Bryn-Julson

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

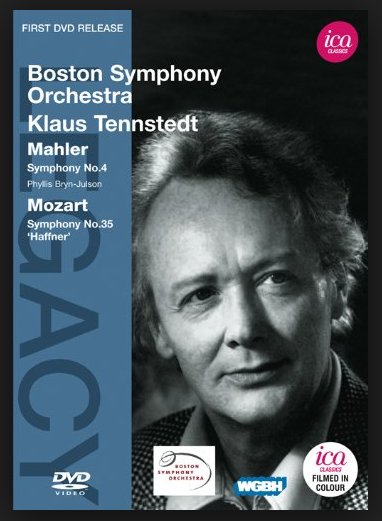

Recognized as one of the most authoritative interpreters of vocal music of the 20th century, Phyllis Bryn-Julson commands a remarkable repertoire of literature spanning several centuries. Born in North Dakota, she began studying the piano at age three. She enrolled in Concordia College in Moorhead, Minnesota, studying piano, organ, voice and violin. She received an Honorary Doctorate from Concordia in 1995. After attending the Tanglewood summer music festival, she transferred to Syracuse University, studying voice with Helen Boatwright, completing her BM and MM degrees. During these college years, she made her debut with the Boston Symphony in Boston, Providence, RI, and Carnegie Hall in New York. She ultimately sang with this orchestra and the New York Philharmonic dozens of times.

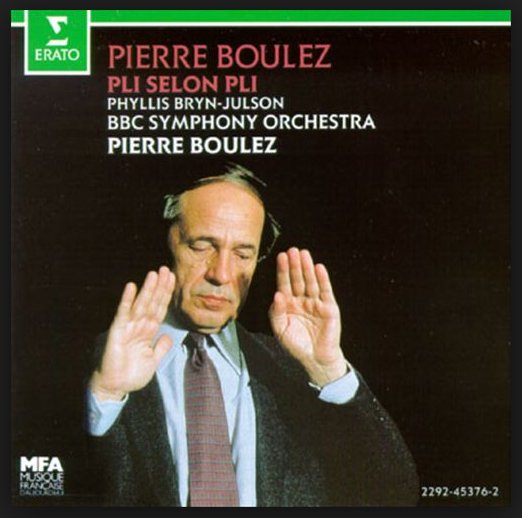

Ms. Bryn-Julson collaborated with Pierre Boulez and the Ensemble Intercontemporaine for much of her career, taking her to numerous festivals in Europe, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the former Soviet Union, and Japan. She has premiered works of many 20th century composers, some of which were written for her. Included in this list are Boulez, Messiaen, Goehr, Kurtag, Holliger, Tavener, Rochberg,Del Tredici,Rorem, Carter, Babbitt, Birtwistle, Boone, Cage, Felciano, Wuorinen, Aperghis, and Penderecki.

In recent years, Ms. Bryn-Julson gave performances of Kurtag's Kafka Fragments in New York at the Guggenheim Museum with Violaine Melançon, violinist. She took part in the Radical Past series in Los Angeles, giving four performances of the great works of Milton Babbitt, John Cage, Cathy Berberian, and Luciano Berio. She toured with the Peabody Trio throughout the United States and Canada, and recorded works of Samuel Adlerfor the Milken Foundation in Barcelona. She also toured with the Montreal Symphony, performing the award winning opera Il Prigioniero by Dallapiccola. Performances occurred at Carnegie Hall, and in Montreal. Following this, she premiered the same work in Tokyo, Japan, where it was staged and televised. With Southwest Chamber Music Society, Ms. Bryn-Julson has performed and recorded the complete works of both Ernst Krenekand Mel Powell. Last season she premiered and recorded An American Decomeron by Richard Felciano, commissioned by the Koussevitsky Foundation, and written for her and the Southwest Chamber Music Society.

With over 100 recordings and CD's to her credit, Ms. Bryn-Julson's performance of Erwartung by Schönberg (Simon Rattle conducting) won the 1995 best opera Grammaphone Award. Her recording of the opera Il Prigioniero by Dallapiccola won the Prix du Monde. She has been nominated twice for Grammy awards; one for best opera recording (Erwartung), and best vocalist (Ligeti Vocal Works). She has received the Amphoion Award, The Dickinson College Arts Award, The Paul Hume Award, and the Catherine Filene Shouse Award. She was inducted into the Scandinavian-American Hall of Fame in 2000. She was the first musician to receive the United States - United Kingdom Bicentennial Exchange Arts Fellowship. She received the Distinguished Alumni Award from Syracuse University, the Peabody Conservatory Faculty Award for excellence in teaching, and the Peabody Student Council Award for outstanding contribution to the Peabody Community.

Ms. Bryn-Julson has appeared with every major European and North American Symphony Orchestras under many of the leading conductors such as Esa-Pekka Salonen, Simon Rattle, Pierre Boulez, Leonard Slatkin, Leonard Bernstein, Claudio Abbado, Seiji Ozawa, Zubin Mehta, Gunther Schuller, and Erich Leinsdorf.

Ms. Bryn-Julson's students continue to win prizes and awards, and have made careers in some of the leading opera houses and orchestral venues. They have had contracts in opera houses in Zurich, Duesseldorf, Vienna, Paris, Lyons, London, and Sydney, and in America, the Metropolitan Opera, Houston, Minnesota, Philadelphia, Seattle, and Washington, D.C

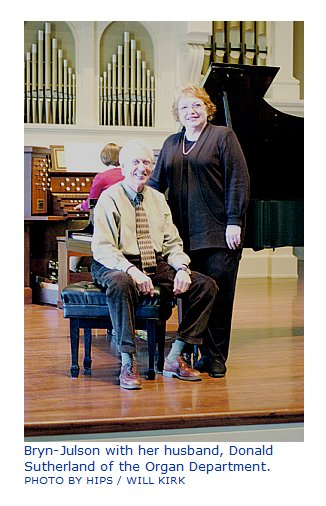

-- From the website of the Peabody Institute of Johns Hopkins University, where she is Chair of Voice

[Note: Names which are links (both in this biography, and below in the conversation) refer to interviews with Bruce Duffie found elsewhere on this website.]

Having previously done many interviews with a number of composers, soprano Phyllis Bryn-Julson was known to me as a performer of their music. I had often played her recordings on WNIB in conjunction with programs of these creators, so it was especially important to make contact with her and arrange to meet while she was in Chicago in May of 1991. She was here for performances of the cantata Le Visage Nuptialby Pierre Boulez with Daniel Barenboim conducting the Chicago Symphony. The program also had music of Schubert and Ravel.

Unlike my notorious

“half-concerts” where I would hear the first part and then meet the soloist backstage after intermission, this time we decided to meet at her hotel following the performance. She was pleased to speak about the various topics, and here is what was said at that time . . . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: You sing all kinds of music, but you’ve made something of a specialty of 20th century music. Tell me the joys and the sorrows of singing something new.

Phyllis Bryn-Julson: Oh, I love it. The new is what keeps me going, really, because I’ve always been an adventurer. It’s music of our time. A lot of this now is very old, as a matter of fact. To do something really, really new, I’d have to really look hard to find something really, really new. But it’s been a strange kind of happening, because when I first went to Tanglewood many years ago, my composition teacher gave me a list of names that I should recognize and memorize in case I run into them. I wish I’d kept the list because it was phenomenal, but the more I separate myself from that experience, I realize how awesome it was. There were names like Cage, Barber, Babbitt, Sessions, Schuller, Del Tredici, Lucas Foss, Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland, Kodaly, Wuroinen, Sollberger, you name it, and they were all there that summer! Sollberger was doing a lot of playing at that time. Now I put myself years away from that, and I think it was phenomenal... and I didn’t get a single autograph! [Both laugh] Oh, I could kill! How stupid of me!

BD: Isn’t it better, though, to get their music and perform it and keep it alive?

PB-J: I guess so! Depends, you know. Now I keep telling people like Pierre Boulez, “Make your signature clear so I can sell it one day, at least.” [Much laughter] It was quite a time in American history. That was a big moment of lots and lots of creativity going on, and to be a part of it was very exciting.

BD: Is there not a lot of creativity still going on?

PB-J: I think so. It’s just that as a beginner, it was exciting to be in the center of such a hub of composers! Certainly there were composers all over Santa Barbara and Aspen and other places, too, but for me this was it. There couldn’t have been any other place that was more like an Eden.

BD: Of all of these composers that you met, have you specifically championed their music?

PB-J: Not from that summer, no, not really. I’ve certainly done a little bit of everybody, I suppose. I certainly know the repertoire. Careers can go in many directions for whatever reasons — some reasons I don’t even know. Managers manage my life, and so sometimes I’m doing things that I really don’t know why or how it happened. Usually I find out, but sometimes, however, I’m in a situation where I really don’t know how it happened, or why, for instance, I have a whole season of Mahler and no modern music whatsoever.

PB-J: Not from that summer, no, not really. I’ve certainly done a little bit of everybody, I suppose. I certainly know the repertoire. Careers can go in many directions for whatever reasons — some reasons I don’t even know. Managers manage my life, and so sometimes I’m doing things that I really don’t know why or how it happened. Usually I find out, but sometimes, however, I’m in a situation where I really don’t know how it happened, or why, for instance, I have a whole season of Mahler and no modern music whatsoever.

BD: I assume you have the final say-so?

PB-J: Not always.

BD: [Genuinely surprised] Really???

PB-J: Sometimes things are so busy that I just can’t keep track of it, really.

BD: So you have to trust your manager?

PB-J: I do, and I’ve never been in a bad situation. It’s always been very nice, but as far as prejudging what the career is going to be, I could not have possibly, ever in my wildest dreams thought that I would be doing what I’m doing and what I have done. I’ve touched every possible period and style that I ever wanted to in my life, and I’ve gotten to do opera and jazz and movies, and I’ve just about really done just everything. It’s all very exciting! There’s lots more I could do, but I have absolutely no complaints whatsoever.

BD: Do you make sure that you get enough time to rest?

PB-J: I used to. [Both laugh] It seems like that becomes more and more difficult. But my career is switching so much, with a major portion of it being in the teaching area. It’s hard to take a summer off when you have areas that want you to come and teach. So this is where it’s going now, and I don’t get my whole summer anymore, I’m afraid. But I do try very hard to make a whole month, if not two months, for myself somewhere along the way.

BD: Are you teaching singing, or are you teaching 20th century singing?

PB-J: Both. I’m trying more and more to develop greater courses in the 20th century repertoire. I’ve done specifically that at Peabody, and next year I will teach 20th Century Art Song. I would like more time to really research and take a good look at the 20th century so that I can get it organized myself. It’s just been sort of, you know, let’s get this done! I’ve got to try to do this by next September, and it’s impossible. It’s going to be someone’s life-long dissertation to sort out this century.

BD: Is there any place you can go to get lists and repertoire just to see how much of an avalanche there is?

PB-J: There is an avalanche, there’s no doubt. There are a few lists. There’s a couple of books that are out, but they go up to 1945, or they only touch repertoire for voice and percussion, or only art song repertoire that is totally non-threatening to any singer. In other words, it’s all tonal. I don’t know how it’s going to be done because there is so much in the European repertoire; we haven’t even scratched the surface. What about South America? What about the Soviet Union? Denisov is the big name out of the Soviet Union in the last ten or fifteen years, and we haven’t scratched the surface there. I know we haven’t.

BD: Are you going to try and plow through new ground?

PB-J: I don’t know. Somebody said, “Teaching is your best teacher,” and it’s been the truth in my life. My students are my best teachers, and teaching the course is going to make me sort some things out. But certainly it’s too big a job for any one person.

BD: What basic advice do you have for someone who wants to sing new music?

PB-J: Learn the old repertoire first. Absolutely learn how to make a phrase and be musical. Sing Mozart. Mozart’s the hardest composer in the world to sing. More and more I absolutely believe this to be true. It is not easy!

BD: It’s the hardest to sing correctly.

PB-J: Yes, and technically perfect because everything shows. So if you can’t do that, then for heaven sakes don’t take it out on the poor 20th century composer. They have a hard enough time selling their music. I know a lot of singers think they can’t quite get their technique together, so maybe they should just plunge into something like Berio. But it just isn’t true because it shows in both. Whether you have technique shows in the modern music as well as the old, certainly.

BD: Do they figure that in the new music one won’t notice if the notes are wrong?

PB-J: Yeah, that people won’t know the difference, and that’s just wrong. Wrong, wrong, wrong! One can do all of it. There’s no reason why any of us should be silly enough to ignore the beauty of Beethoven songs and Mozart songs and so forth. It’s healthy to do them all, and you just bring in greater understanding to the new music. Certainly the new music helps the old because if you learn the new music right and you learn it accurately, then you take that accuracy back to the old music and suddenly you’ve got, voila, a whole new creation!

BD: Do the new composers — the ones who are writing today or the ones who have recently stopped writing — know how to write well for the voice?

PB-J: This is a hard question. I can, however, go back to Beethoven. Did he know how to write for the voice? Whether it was the pitch sense at the time I don’t know, but that certainly is some of the most difficult writing. It’s very high, and one must repeat words up on the high notes that’s just like Del Tredici today. There is a total parallel right there. Composers don’t have a book like they do for clarinet, for example, telling them what’s the highest note on a clarinet and how low it goes. You can do this or that with the string for the violin, but there is nothing like that for the human voice.

BD: Should there be?

PB-J: I don’t know that there ever could be, because the minute I tell you that I shouldn’t sing the e vowel on the note E or G, someone else will come along who can do it. We’re dealing with equipment here that is completely different per person. I suppose each instrument is also different, but not as vastly different as the human body.

BD: Each voice is unique?

PB-J: Each voice is unique because there are different stress points. In general, a dramatic soprano is always going to be Wagnerian or Verdian. In general, the lyric soprano is always going to be able to do certain lyric roles, but in the end there still is one thing. There could be one or two different notes or variations in the human voice that would be different than anybody else’s, and those are things that one must find out. I always say I’m in the practice of teaching like the practice of medicine. You bring in a new student and you listen and you look and you study and you try to observe, and it’s going to be a little different from the other lyric soprano I had in the same room.

PB-J: Each voice is unique because there are different stress points. In general, a dramatic soprano is always going to be Wagnerian or Verdian. In general, the lyric soprano is always going to be able to do certain lyric roles, but in the end there still is one thing. There could be one or two different notes or variations in the human voice that would be different than anybody else’s, and those are things that one must find out. I always say I’m in the practice of teaching like the practice of medicine. You bring in a new student and you listen and you look and you study and you try to observe, and it’s going to be a little different from the other lyric soprano I had in the same room.

BD: Yet both of those lyric sopranos, different though they may be, are going to have to sing overlapping repertoire.

PB-J: Same repertoire, yup, and it’s difficult. That’s what makes it fascinating and also makes it difficult.

BD: For you yourself, you are offered all of these new pieces and all the old pieces. How do you decide which ones you’ll say, “Sure, I’ll learn them,” and which ones you’ll say, “No, I don’t want to touch this piece?”

PB-J: If you’ve done your homework and done a lot of listening to the modern music and various styles

— because we have a lot of styles to listen to these days — eventually one gets to a point of being able to judge something as being good or bad. Again, I keep comparing it to the old repertoire because I think people identify with that quickly. For me, a piece has to speak something to me. If it’s interesting rhythmically, I like that. If it’s got a superb text and if the composer really set the text well, that’ll get me every time. If it’s fun, I’ll read it and have a go at it. If it’s just craziness and seeming to be too many thirteens against tens for endless numbers of pages, I probably will say no. Somebody else can have it. I already did that stuff. [Both laugh] But I’m sure that there are lots of worthy pieces that shouldn’t be just thrown away, or tossed off like that.

BD: What is it that makes a piece worthy?

PB-J: It has to somehow move me. If it doesn’t get to me first, then I wonder if I can really do it justice. For a long time I felt that I was put here to do exactly this thing, to present the music that I could

— given my abilities — to the public, and to give every composer that happened to come across my way a chance at this because obviously he spent a great deal of time creating. If he or she is a serious composer, they deserve to have the best possible hearing of their music. But now I’m so very, very busy that I just have to make sure I have enough time to learn a piece. I have one with me at the moment, as a matter of fact, and it already looks just very, very difficult, and has a tape to play to go with it. It’s a lot of notes.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] Didn

’t someone tell Mozart he wrote too many notes?

PB-J: That’s right, and in a row, too!

BD: There seems to be a parallel between the time of Mozart and even a little before, and the 20th century, leaving this big gap in the middle.

PB-J: Yes.

BD: People who specialize in 20th century often do Baroque up to Mozart. Why is that?

PB-J: True. I think because they both require a very clean kind of singing, for one thing. Some people are going to be mad at me for saying that but I, for one, like to hear Mahler done very cleanly also. But the Romantic Period brought along a lot of bigger, heavier voices. Certainly Wagner, Strauss and all of that just opened up a huge door and we will never, ever probably recover from that. Everything that’s happened in this century is really their fault. If you listen to Wagner, it’s every bit as difficult as Boulez, maybe more so.

BD: And yet we’re used to the Wagner.

PB-J: Yes, I guess you are if one has listened to it a great deal. But if one begins to tear apart the score to even put together the complexities of the chordal progressions and so forth, this is really outrageous, unbelievably difficult! But it is the cleanliness of the singing of the Mozart. You can’t really sing Mozart with an enormous wobble or a very dramatic voice, and get by with it for a very long time.

PB-J: Yes, I guess you are if one has listened to it a great deal. But if one begins to tear apart the score to even put together the complexities of the chordal progressions and so forth, this is really outrageous, unbelievably difficult! But it is the cleanliness of the singing of the Mozart. You can’t really sing Mozart with an enormous wobble or a very dramatic voice, and get by with it for a very long time.

BD: Once in a while you get a Nilssonsinging Dona Anna, but that’s about it.

PB-J: Yes, and that doesn’t bother me. There should be lots of flavor to the kind of voices that fill those character

s’ shoes.

BD: Obviously when you get to a piece you’ve got to perform it correctly, but is there only one way to perform a piece correctly?

PB-J: No, certainly not. I’ve heard some pieces that can be. Not Bach or Mozart, though. Usually that requires a certain kind of voice, and most people usually ask for the lyric voices to sing that repertoire, but certainly in the later repertoire. I’ve heard Berg, for example, sung with a variety of voices, from the very lightest kind of lyric voices where the orchestras have to play very softly. But I’ve heard Mahler done with many different types of voices. All of it deserves some kind of attention and merit for what they do. There was a reason for choosing the person to do that, whatever it was.

BD: The music of our time comes out of the age that we live in, and yet you have to sing Mozart despite the fact that we’ve gone through world wars and depressions and all of this. How can we make the old music speak to us as well as the new music?

PB-J: By listening to the new music. I think they need each other. If you listened to the Boulez tonight and then you heard the Ravel following, the Ravel benefited from the Boulez and the Boulez benefited from the Ravel. It can be the same with Tchaikovsky. If you listen to the most avant garde piece that was ever written in the world, something very, very modern — maybe some Carter or Babbitt — and then you listen to Tchaikovsky after this, both are going to be enhanced. It’s because of your listening to the Babbitt (or whatever it was) that made you listen to the Tchaikovsky with a keener ear, a better ear. It never fails. You have to open your ears and your mind to accept this idea. It’s been that way since ever. That’s history.

BD: As we head into the last decade of this millennium, how do we get the audiences to demand Babbitt and Carter and Boulez on the same program with Tchaikovsky and Ravel?

PB-J: They may not be able to, but as teachers we should do it. I think Mr. Barenboim will be a perfect leader in this area because he knows this repertoire. He knows very, very much the 20th century, and I think it’s fortunate to have him in this country, let alone with the Chicago Symphony. But that’s what we have to do

— keep inviting and keep showing that this really belongs, and choose the works that have already withstood a great many performances and have, so to speak, withstood many audiences and many reactions. Certainly this Boulez piece, has been done a great deal already. Other Boulez pieces have been done even more and they have withstood the test of time. Also Mr. Barenboim told me there’s a discussion about the composer before the programs, and that is good. This gives audiences an important opportunity. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could just ask Mozart what he meant by writing that low A and then the high A in the opening of the Mass in C Minor, or the low B-flat, A-flat, and then up to high A-flat?

BD: What if he tells you it’s just for the emotional impact?

PB-J: But it’s the way it is, of course. I’m sure he has a reason. But I just think that’s a wonderful opportunity today, and I hope people will take advantage of it. It’s a sure way to get involved a little more than anyone had ever hoped to.

BD: We’re kind of dancing around this, so let me come straight out with the question. What is the reason for music in society?

PB-J: I think it’s absolutely the reaction to society. It’s our release. It’s our sanity, and it pains me when I read that schools are taking music out of the curriculum. It pains me when I find that children really have to beg their parents to allow them to have a piano lesson. In fact, if they have this little bit of emotional tug of war with the heart, you can bang your emotions and frustrations out on a drum or learn to play a beautiful flute line — not that you ever have to do it in your life, but that this is what keeps our society sane. You’ll find people that have no music or art in their life live that way. They have very little human emotion. I know very few loving and caring people who would honestly say that they never ever listen to a piece of music in their life no matter what it is. It doesn’t have to always be classical, certainly. Many of the best rock bands, for example, have a terrific background in their education in music. I know they do because I’ve listened to it with my children, trying to keep up with them. There is a terrific difference between the composers who have actually studied the instruments and studied music in a situation in a university or school, compared to those who just lucked out and got into it and didn’t study at all.

BD: How are the electronics fitting into all this?

PB-J: I don’t know yet. I really don’t know.

BD: Are we going to have to wait fifty years and look back?

PB-J: [Laughs] I think so. For me, some electronic sound is tasteful and some is not. I’ve done a lot of electronic music for voice and synthesizer, or tape. Heinz Holliger wrote a piece for me many years ago called Not I, a Becket play, and it was with sixteen-track tape of my voice.

BD: So you were the seventeenth part?

PB-J: I was the seventeenth part.

BD: Did you feel like a seventeenth wheel? [Both laugh]

PB-J: A little bit, but it was fascinating and it didn’t come across as being an electronic, or that kind of quality. It came across as being certainly what the play is, Not I, and it was just as very, scary frightening as it was to sing it. As far as just electronics for the sake of electronics or adding to the sound of the human voice, I’m not sure I really am for that yet. Maybe if we electrify the violins and the cellos and everybody gets electrified, all right, we’ll try it. But just for the voice, no.

BD: What about the other side of the electronics

— the proliferation of recordings that are easy to play at home?

PB-J: Well, the CD is, as you know, the most perfect recording now...

BD: [With a good-natured sneer] Aw, they said that about 78s when they changed from the acoustic process to the electrical process, and then the first LPs and then stereo...

PB-J: [Laughs] Yes, it’s unbelievable. But I hope people will remember that the excitement about being live in a hall just can’t be matched with a CD. I don’t think it can with any kind of recording. It’s maybe the too perfect kind of situation, rather than being in a place where there’s some excitement because you don’t know what’s going to happen. In a live concert, you don’t know how a piece is going to end. You don’t know how the piece is going to be in the middle. It’s so great.

BD: You’ve made quite a number of recordings. Do you sing the same way in front of a microphone that you do in front of an audience?

PB-J: I try to. Certainly, there are little adjustments one has to make, like the S sound. Speech-wise, one has to be more careful in front of a microphone, so that changes. Diction changes as does sometimes the quality of sound or the length of a phrase. If it were a particularly big moment with the orchestra, I would actually be able to sneak a breath in a live performance in order to sustain it, whereas with a recording I don’t have to do that. So I back off a little bit. They mike it up or I stand close to the mike, and I can do it in one phrase because the microphone’s going to tell everything. That’s the only thing about that. It’s going to tell whether I’m sneaking breaths.

BD: [With mock horror] You mean the microphone is completely honest?

PB-J: Yes. Absolutely!

BD: But is the splicing tape completely honest?

PB-J: Well, that’s probably not, but in the recordings I do I’ve been really fortunate. It’s usually with people who like to go through it and then cover the spots that were bad. I think piecing together a piece is just tiring and you lose it; you don’t have a piece at all. I’ve been so lucky with Boulez. It’s just a dream to record with that man. It’s very clear. Of course I’m a little nervous, and usually the first time through sounds nervous, but he knows that. I know that. The orchestra knows that. So we’ll do it one time through. You have to get the cobwebs out, and then the second time through sparkles happen and so do mistakes. So we just cover those mistakes and we’re done. It’s really wonderful. I think the hardest one I did with him was the Pli selon plibecause all of us wanted to make this the most perfect recording of this piece. We wanted everything lined up, everything in tune and yet very beautiful. It took us forever! It was three long days of recording. It was hard.

PB-J: Well, that’s probably not, but in the recordings I do I’ve been really fortunate. It’s usually with people who like to go through it and then cover the spots that were bad. I think piecing together a piece is just tiring and you lose it; you don’t have a piece at all. I’ve been so lucky with Boulez. It’s just a dream to record with that man. It’s very clear. Of course I’m a little nervous, and usually the first time through sounds nervous, but he knows that. I know that. The orchestra knows that. So we’ll do it one time through. You have to get the cobwebs out, and then the second time through sparkles happen and so do mistakes. So we just cover those mistakes and we’re done. It’s really wonderful. I think the hardest one I did with him was the Pli selon plibecause all of us wanted to make this the most perfect recording of this piece. We wanted everything lined up, everything in tune and yet very beautiful. It took us forever! It was three long days of recording. It was hard.

BD: Did it finally work?

PB; I think so, but I’d like to have a second shot at recording again. Now I’d say I’m not so much for the perfection as I am for making it real. I don’t know. I haven’t listened to it for a while. Maybe I’d change my mind.

BD: Where is the balance, then, between the technical perfection and the inspiration of the moment?

PB-J: It’s hard because I think that happens over a period of time. If we’re lucky enough to record something more than once in a lifetime it is wonderful. I’ve been lucky with Pierrot Lunaire, my third recording in this next year. It will have changed and also the groups change, so there it’s going to be lots of different things. Something like the Beethoven symphonies, which I can’t believe how many times they’ve been recorded. I don’t know that that’s really necessary. I wish we could do a little more Benjamin Britten fifteen times or Vaughn Williams or Elgar or some of these composers of major works that would be so beneficial to hear more than once. Sibelius doesn’t get nearly enough attention for what he wrote.

BD: And yet you wouldn’t want to give the same attention to Sibelius or Vaughn Williams that we give to Beethoven every year.

PB-J: No, I wouldn’t. Beethoven, I think, will begin to lose pretty soon if he keeps getting so much attention. Every time I read a magazine, Beethoven’s being recorded again.

BD: Often by the same people again.

PB-J: Yes. Unbelievable!

BD: Let me ask another balance question. Where is the balance in music between an artistic achievement and an entertainment value?

PB-J: Oh, that’s a perfect question for Peabody! We talk about this all the time. I guess we say it is entertainment, and then that sounds so Hollywood and trashy. But in the end I don’t think it’s entertainment in the classical arena, certainly not like Hollywood. But it is entertainment by the mere fact that it deals with beauty. When doing a musical performance, everything should look good, everything should feel good. The hall should feel good. You don’t want to go into some sleazy place that looks like a barn, for example, and find everybody coming out in jeans and sweatshirts going to do this Ravel for you at this moment. So in a sense, that’s entertainment, that’s the entertainment value — the feeling that the musicians are very special people. I think there is a kind of a stardom that comes with it. That’s sort of a Hollywood thing also, when it’s not really true. We’re all just as human as everybody else. What is untrue is that we spend most of our day reading or doing something like that, when in fact most of the day is spent trying to get ready for the next concert and practicing the music that we have to learn and translating your text. I don’t speak Swahili, so I’ve got to find a Swahili person to coach me. It’s a lot of work. It’s more than entertainment, certainly. It should give the audience a feeling of peace and calm and beauty. When somebody falls asleep in a concert, I think that’s a marvelous compliment.

BD: [Somewhat shocked] Really???

PB-J: When a person in an audience falls asleep, this means that the person has been put serenely out. For the moment anyway, something went so well with the person. It’s better than watching them cling to the edge of their seats. [Laughs]

BD: Or fidget.

PB-J: Depending on what the piece is, of course.

BD: I can just imagine now there’ll be a cartoon where you’re singing and everyone is asleep. [Both laugh]

PB-J: What a great idea! Paul Hume once suggested I do a whole recital of lullabies. He just happened to like the way I sang lullabies. I often think about that and laugh. If I ever did a program of lullabies, that would be quite something.

BD: Sounds like a psychological experiment rather than a concert.

BD: Is singing fun?

PB-J: Most of the time

PB-J: Most of the time

— if everything is going well, if my voice is working right, if I didn’t have to blow up at anybody today, if I didn’t have to scream at anyone or have an argument... It’s really peculiar — it’s not the kind of life that is at all normal when you think about it. You go off to a hotel. You can’t talk to too many people because then you’d lose your voice for the concert. Somebody might say something wrong that just irritates you the wrong way. Any little thing like that can take away the special adrenaline or the moment, the sparkle that goes into the performance. So that’s the hard part. Whether that’s fun, I don’t know. Fun comes when you’re in the middle of the piece and things are going well and everybody’s really doing their job and you feel it in the room. You feel it with the audience; you feel it with the conductor. That’s fun.

BD: I assume you wouldn’t trade it for anything?

PB-J: No, but it certainly isn’t like playing golf. Now, that’s fun. [Both laugh]

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of music?

PB-J: Yes. It’s always survived. It certainly goes through bigger pitfalls than any other career in this country. For the life of me, I can’t figure out why it should happen over and over again that National Endowment funding is cut or that the government decides that funding for the arts is really not worthwhile. Would they rather have all of us on welfare? Is that the choice? It just doesn’t make any sense. I remember once Beverly Sills asking a President to give us just enough money to pave one mile of road — just put that amount into the arts. Or the money to make one bomb. That’s all we need. It really isn’t much. It’s a drop in the bucket compared to the rest of the budget for the government. Anyway, I think it will survive, certainly. It’s going to depend a lot on the kind of community help and support that exists in every city where there’s a major orchestra. It would be very, very sad, and a lot of people would realize it and recognize it if anything happened to the major orchestras. We’ve had a couple of orchestras in this country that have gone under for a few years, and it’s not good because these were major orchestras. So be on guard, if I can say that. Take care of the orchestra. At least if you’re listening in the audience, make sure that they know that you want them to remain intact. Think of this beautiful hall that exists in Chicago. All over the country we have beautiful halls and beautiful orchestras.

BD: You work with a lot of young singers. How is the raw talent that’s coming along these days?

PB-J: Better and better all the time. It’s amazing! And the other phenomenon is that people don’t seem to be shying away from going into the singing career. I can’t believe it! I’m always a little optimistic and a little pessimistic with them. I give them reality checks. Nine times out of ten, if I’m lucky to have one student every few years that actually makes music a go as a living. This doesn’t mean that none of them can sing, but there are lots of reasons

— maybe marriage, maybe a change and something happens in the person’s life, or maybe they decide they don’t want it. They prefer to go to some nice little community and teach and maybe do some community recitals, and they’re happy to sit in a smaller area. We’re being very positive at Peabody and tell them that you don’t have to make the career by singing on the Met stage. Nine times out of ten you won’t. A lot of us have never been on the Met stage, but you can do a lot of work in this other area which is keeping the arts alive. You can go to a community and really put your best effort into building a good music center in some way or other. You can work for arts management; you can work for an orchestra. There are lots of jobs to be had, and then you also keep your singing going. It doesn’t mean that you haven’t made it or that you’ve been a failure. We need to build strong audiences and strong supporters, and a lot of the people coming out of conservatories are going to be exactly that. They’ll do a lot of help in the community theater or maybe join the opera chorus. They can be very, very useful. A lot of good singers can be in these spots. If you look at Europe and compare the two, we still have a long way to go with supporting the young musicians just when they’re beginning.

BD: What advice do you have for audiences that come to hear your performance

— or any performance?

PB-J: Do their homework if they can. If they can’t, that’s fine, but there’s plenty of reading material. I can remember doing the Holliger-Beckett Not I at the Kennedy Center, and we made sure that there were plenty of copies of the play, and that there was open discussion about the play. Those are the kinds of things that are there for a good audience if they’re interested and curious to find out why. What does it mean? What’s it all about? Or they can come and ask us. None of us are afraid to talk. We’ll talk your heads off. [Both laugh] I can tell you all about Boulez and some of the neat things about this piece and other pieces I’ve done by Del Tredici and Ned Rorem. I can talk a good deal about composers and their lives, and how frustrating it is at times for them, and how sometimes they feel like they’re batting, working against a hard rock all the time instead of the other way around.

BD: Most people would put those three

— Boulez, Del Tredici and Rorem— into one segment, and yet they are very disparate.

PB-J: Absolutely. Three different varieties of composers that exist, and also Elliott Carter. A lot of the composers realize, as with anything else, that people are going to know them best after they’re gone. What a pity! I suppose that’s also history in a way.

BD: The music that you sing

— is it for everyone?

PB-J: No, certainly not. I have my favorites like anybody else. When you’re looking at a style or a period or a type of music, especially in the 20th century, one can go at it many ways. One can take it just by itself and leave it there. You’ve just heard this piece of Boulez and you just take it for what it is, or you can be a little more broad-minded and put it in the context of the French evolution of writing. Or you can even go so far as to compare it to someone like Messiaen

PB-J: No, certainly not. I have my favorites like anybody else. When you’re looking at a style or a period or a type of music, especially in the 20th century, one can go at it many ways. One can take it just by itself and leave it there. You’ve just heard this piece of Boulez and you just take it for what it is, or you can be a little more broad-minded and put it in the context of the French evolution of writing. Or you can even go so far as to compare it to someone like Messiaen

— one of the great French teachers — or Boulanger to see where are the influences here and where does Boulez fit in. He studied with Messiaen, but there is very little Messiaen in the writing of Boulez, yet there is an overall French-ness about everything. Boulez would hate that, however! But one can look at it then with this programming, which was absolutely superb. Barenboim should be congratulated for putting the Ravel at the end because that really tied it all together. It’s the 20th century going backwards. Then you begin to see. It’s like with paintings; it’s the same in the art world. You can look at a progression in a country and you can almost see, certainly, the social times. You can see what was happening politically in many instances. I can’t say that about the Boulez work, but I just think that if you can approach it in a way of looking at the music, it can be done in many, many ways, not to just be single-minded and say this it’s René Char and it’s Mallarmé or whoever, and it’s at this moment and I must accept this now. Put it in the context with the program or with the history. Then it becomes fun to really do a little digging. Who were these poets? What were they all about? What were they doing? They were sitting in cafés. What was happening at the time? It must have been fascinating in Paris at that period. It must have been wonderful.

BD: But it’s also fascinating now.

PB-J: It is now, but unfortunately they’re dead.

BD: But I mean it’s fascinating what’s coming now, what’s being done now.

PB-J: Yes, yes, and what will happen in 2000. I can’t wait. I’ll be happy to see what is going to happen. Look at the last change. In 1900 we had Strauss, Wagner, Webern, Schoenberg and Berg. Can it get any better or worse that that in the year 2000? I can’t wait!

BD: Do you have any ideas? Gaze into your crystal ball.

PB-J: No. I wouldn’t even attempt that. I always throw that out for the doctoral students at Peabody. I say, “That’s stuff you should be thinking about. It’s your job, not mine.”

BD: Thank you for doing your job so well.

PB-J: Well, thank you. Thanks very much.

BD: Thank you for coming to Chicago. I hope you will be back.

PB-J: I hope so, too. My friend, our friend

— my husband’s and my friend — Henry Fogel, is here. You know Henry [President of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra 1985-2003]?

BD: Oh sure, yes.

PB-J: Do you know the story of his radio station in Syracuse? It must be thirty years now, when we were all there at school he started the first classical radio station in his kitchen, and when the refrigerator went on, the radio cut off. If he forgot to unplug the refrigerator, he’d be playing along some beautiful orchestra thing, and suddenly the phone would ring, “Henry! Your refrigerator’s gone on!” [Both laugh] My husband would call him every other day. “Henry! Turn the refrigerator off!” He was notorious. He didn’t have a dime at the time, and he still was just so inventive and creative and wonderful people, he and Frances were. We knew them way back then, before children. He’s also a fantastic oriental cook... His son’ll kill me for saying that because he had to do all the chopping!

BD: Thank you for spending a little time after the concert. I appreciate it.

PB-J: You’re welcome.

======= ======= ======= ======= =======

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

======= ======= ======= ======= =======

© 1991 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded at her hotel following the Chicago Symphony concert of May 9, 1991. Segments were used (with recordings) on WNIB in 1995 and 2000. A copy of the unedited audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. The transcription was made and posted on this website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website,click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.