The Functional Impact of the Intestinal Microbiome on Mucosal Immunity and Systemic Autoimmunity (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2016 Jul 1.

Published in final edited form as: Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015 Jul;27(4):381–387. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000190

Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review will highlight recent advances functionally linking the gut microbiome with mucosal and systemic immune cell activation potentially underlying autoimmunity.

Recent Findings

Dynamic interactions between the gut microbiome and environmental cues (including diet and medicines) shape the effector potential of the microbial organ. Key bacteria and viruses have emerged, that, in defined microenvironments, play a critical role in regulating effector lymphocyte functions. The coordinated interactions between these different microbial kingdoms—including bacteria, helminths, and viruses (termed transkingdom interactions)—play a critical role in shaping immunity. Emerging strategies to identify immunologically-relevant microbes with the potential to regulate immune cell functions both at mucosal sites and systemically will likely define key diagnostic and therapeutic targets.

Summary

The microbiome constitutes a critical microbial organ with coordinated interactions that shape host immunity.

Keywords: Microbiome, Th17 cells, Treg, ILC3, Prevotella copri, Transkingdom interactions

Introduction

The intestinal microbiota has emerged as a microbial organ, shaped by host genotype, developmental needs, and environmental exposures. Pioneering advances in using culture-independent methods to identify the components of the human microbiome by 16S rRNA sequencing composition revealed that two bacterial phyla, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, constitute >90% of the mammalian genome. Despite substantial interpersonal variation in the microbiome in healthy individuals [1,2], a core minimal metagenome exists with 3.3 million non-redundant bacterial genes (~150 times the human genome)[3]. These genes are 93% conserved at the enzyme level and play a critical role in secondary metabolism of carbohydrates and sugars for energy extraction. To understand the relative contribution of host genotype versus environmental conditions in determining this variation in the human microbiota, adult twin-twin and twin-mother comparisons have been conducted [4]. Notably, the results revealed equivalent differences in dizygotic and monozygotic twin-twin comparisons, both of which were more dissimilar than self-self comparison but more similar than twin-mother comparison, suggesting a key role for environmental cues in shaping the microbiome. Recent studies have revealed how key environmental and microbial exposures functionally shape the mucosal immune system with more pervasive effects on systemic immunity. Mechanistic insights provided by these studies will help identify novel biomarkers and therapeutic strategies for autoimmune diseases.

Environmental Cues Shape the Microbiome’s Impact on Metabolic and Inflammatory Disease

Dietary and xenobiotic (e.g. foreign to host) exposures are key regulators of the gut microbiome. For example, a high-fat, high-sugar diet stereotypically altered the gut microbiota in outbred mouse strains as well as numerous inbred mouse strains deficient for immune-linked genes [6]. Notably, alterations occurred within several days. Pilot studies in humans have confirmed these findings [7]. In particular, ten healthy individuals on a stable diet were switched to either plant- or animal-based diets ad libitum for five days. Similar to mouse studies, significant changes were seen in the composition and diversity within several days of dietary changes. These changes resulted in changes in production of short chain fatty acids critical for promoting barrier health as well shifts in the enzymes involved in nutrient extraction. Correlative findings from the microbiota of obese individuals revealed stereotypic reductions in the Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio. When transferred to gnotobiotic (germ-free) mice, these microbiota resulted in an obese phenotype with increased caloric energy extraction from food [5].

Dietary changes associated with geographic and cultural factors produce characteristic differences in the microbial communities. For example, substantial differences between the distinct communities from the Amazonas of Venezuela, rural Malawi and US metropolitan areas exists including a stereotypical Bacteroides/Prevotella “trade-off” in the composition of the intestinal microbiome [8]. Within communities, pronounced differences are seen in infancy (<3 years old) compared with adults, reflecting age-associated changes in vitamin and nutrient extraction requirements—e.g. increased abundance of enzymes involved in de novo tetrahydrofolate (THF) synthesis in breast-fed babies compared to an increased abundance of enzymes involved in THF extraction in adults and formula-fed infants. Illustrating the effect of culturally-driven dietary influences on shaping these differences, routine consumption of non-caloric artificial sweeteners led to key shifts in the microbiome, which, similar to the obese microbiome, can transfer a phenotype of inflammatory metabolic syndrome to germ-free mouse hosts [9].

This plasticity of the microbiome driven by dietary factors may therefore modify an individual’s risk for systemic inflammatory disease. Seminal work from Eugene Chang’s group illustrated the importance of saturated fat in providing a sulfur-rich environment to support the expansion of the Deltaproteobacteria B. wadsorthia. Coupled with genetic susceptibility for colitis, this expansion of B. wadsorthia resulted in more severe colitis in mouse models [10]. A recent study illustrated the similar potential of commonly-used dietary emulsifiers, carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) and polysorbate 80 (P80), that are detergent-like molecules used as food additives to affect product viscosity. CMC and P80 compromise barrier functions and permeability of intestinal mucosa, leading to microbial population changes that may cause colitis and metabolic syndrome in genetically susceptible animals. [11]. We recently described the expansion of Prevotella copri in patients with new onset rheumatoid arthritis (NORA) [12]. Notably, Prevotella abundance in these NORA patients inversely correlated with genetic susceptibility conferred by the shared epitope HLA-DRB1, further suggesting a potential role for the microbiome in driving an inflammatory phenotype. A Prevotella-predominant microbiome may also confer susceptibility to inflammatory cardiovascular disease in patients with meat-based diets high in L-carnitine. Metabolism of dietary L-carnitine by the intestinal microbiota results in higher serum trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) which correlates with atherosclerosis in humans and accelerates atherosclerosis in mouse models [13]. A further understanding of these potential biomarkers may guide rational therapeutic use of diet in modulating inflammatory disease.

Additionally, the specificity of the microbiome may regulate the efficacy of xenobiotic or therapeutic drug intervention for the treatment of autoimmunity. The conversion of digoxin to inactive derivatives by the Actinobacterium Eggerthella lenta provides a classic example of this effect [14]. Transcriptional profiling and comparative genomics using high-throughput sequencing allowed the recent discovery of a cytochrome-encoding operon (called cardiac glycoside reductase (cgr)), which is inhibited by arginine in E. lenta and regulates digoxin metabolism [15]. Similarly, in NORA, functional analysis of the Prevotella-dominated metagenome reveals a significant decrease in purine metabolic pathways, including tetrahydrofolate reductase, which may have implications for the therapeutic efficacy of methotrexate [12]. Collectively, these recent studies offer insight into the regulation of drug metabolism by the host’s microbial organ.

While plasticity exists in response to dietary alteration, emerging data suggest that a window of opportunity exists in imprinting the early childhood microbiota with critical effects on the metabolic function of the gut(?) microbial organ(?). Recent analysis of malnourished twins in both Bangladesh and Malawi revealed that therapeutic intervention with ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) engendered only transient restoration in metabolic function and the gut microbiome of malnourished children, both of which regressed when RUTF was stopped [16,17]. Gnotobiotic mice colonized with fecal communities from malnourished donors lost significantly more weight than mice colonized with fecal communities from the non-malnourished twin illustrating the potential microbial-dependence of severe malnutrition (Kwashiorkor). In contrast, alterations in the microbiome can support enhanced caloric energy extraction and growth. Indeed, farmers have historically capitalized on the ability to alter long-term metabolic outcomes by feeding low-dose antibiotics to livestock for growth promotion. Recent studies in mice using low-dose penicillin (LDP) delivered from birth (compared to after weaning) revealed a critical window in development for imprinting a durable microbiome with the propensity for enhanced energy extraction and growth [18]. Thus, in combination with environmental triggers, such as high-fat diets typical of western society, early-life exposure may result in durable effects on the microbiome which predispose towards metabolic and inflammatory disease.

Commensal Microbiota Promote Homeostatic Regulation of Immunity

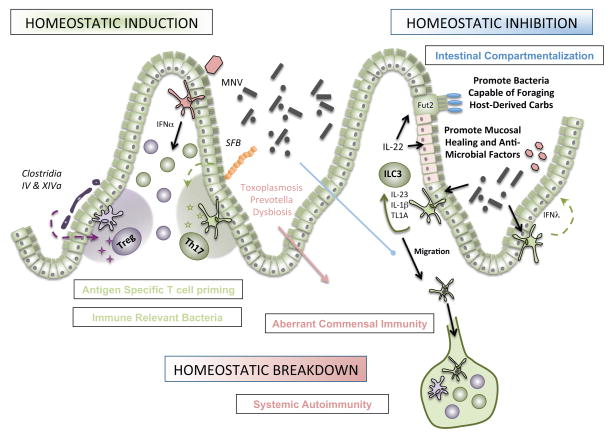

In addition to modulating metabolic functions, commensal microbiota within the gut ‘microbial organ’ maintain the delicate balance of immune effectors, which must remain tolerant to innocuous microbial antigen yet poised to protect the host against invasive pathogens. While a thick mucus layer coating the mucosal surface provides a “demilitarized zone” to promote segregation [19], we have proposed two main immune mechanisms for maintaining this balance: homeostatic inhibition and homeostatic induction afforded by mucosal immune cells [20] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Microbial Regulation of Immunity and Autoimmunity.

Homeostatic induction is maintained by sentinel microbes in which the barrier remains intact. Representative adherent microbes such as the mouse commensal segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) tethers to the ileal mucosa and induces antigen-specific Th17 polarization. Similarly, key clostridial species promote the differentiation of induced Treg cells. Viruses, such as mouse norovirus (MNV), are sufficient to promote lymphocyte homeostasis in the lamina propria via an IFNα-dependent mechanism. Homeostatic inhibition is achieved by re-enforcing intestinal compartmentalization of microbes. Microbial activation of CX3CR1+ mononuclear phagocytes regulates group 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3) to produce the key cytokine IL-22 which promotes mucosal healing, anti-microbial peptide production, and modification of carbohydrates for bacteria. Homeostatic breakdown variably alters these mechanisms, resulting in trafficking of luminal microbes to mesenteric lymph nodes by CX3CR1+ MNPs, aberrant immunity to commensal microbiota, and subsequent systemic autoimmunity.

Recent evidence revealed the contribution of intestinal mononuclear phagocytes (MNPs) to homeostatic inhibition. Two developmentally distinct classes of CD11b+ CD11c+ MHCII+ MNPs exist in the lamina propria—CD103+ conventional DCs (cDCs) and the CX3CR1+ MNPs. Historically, CX3CR1+ MNPs were thought not to migrate, but recent data from our lab suggest that microbiota actively limit the trafficking of CX3CR1+ MNPs [21]. In the context of antibiotic-induced dysbiosis, CX3CR1+ MNPs can migrate to the mesenteric LN and traffic luminal, non-invasive bacteria, resulting in aberrant immunity to commensals. This pathway may contribute to commensal reactivity seen in IBD as well as epitope spreading resulting in aberrant immunity to benign commensal and/or self-antigens. Detailed analysis of these cell populations in response to commensals during steady state as well as inflammation will likely identify targetable pathways in inflammatory disease.

In addition, normal gut microbiota promote homeostatic inhibition by group 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3). ILC3s are major producers of IL-22, a key cytokine that acts on epithelial cells to promote healing both in the steady state and during infection [22],[23]. IL-22 also induces antimicrobial peptide production, including the C-type lectins RegIII, by epithelial cells. These antibacterial proteins directly target Gram-positive, but not Gram-negative bacteria, by forming a hexameric membrance-permeabilizing oligomeric pore [24]. Recently, another, albeit indirect, mechanism of ILC3-dependent reguIation of luminal bacteria was discovered: epithelial cell fucosylation. These terminal fucose moieties can be cleaved by bacterial-derived fucosidases and confer a selective survival advantage to bacteria capable of foraging host-derived carbohydrates, such as Bacteroides thetaiotomicron [25]. Thus, ILC3 maintain homeostatic inhibition by wielding the proverbial carrot and stick (fucosylated carbohydrates and RegIII, respectively) [26].

How are these bacterial signals sensed by ILC3? During inflammation in both mice [27] and humans [28], MNPs expand in the lamina propria. Secretion of CXCL16 by the MNPs acts on CXCR6+ ILC3 to promote co-localization [29]. Early-life microbial exposure, particularly in the neonatal period, may help shape barrier immunity by epigenetically imprinting the Cxcl16 locus [30]. We have recently shown that stimulation of MNPs, but not cDCs, induced the production of IL-23, IL-1β, and the TNF superfamily member 15 (TNFSF15), which potently augment IL-22 production by ILC3 [28]. In patients with mild to moderate colitis (both Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis), exposure to the fecal stream increased production of IL-22 by ILC3, implicating the microbiota in this response [28]. Mechanistic understanding of selective and potentially targetable pathways will be critical for therapeutic intervention to promote mucosal healing.

In contrast to innate processes of homeostatic inhibition, commensals are also capable of inducing specific T cell differentiation pathways in the absence of barrier damage, termed homeostatic induction. For example, Clostridium clusters IV and XIVa, isolated from a healthy human donor, induce colonic Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) that produce the anti-inflammatory protein IL-10 [31]. Notably, these strains are decreased in patients with IBD [32] and colonization of germ free mice with these bacteria attenuated disease models of colitis[31]. Mechanistically, Clostridial induction of Tregs requires TGFβ and high luminal concentration of short chain fatty acids—primarily butyrate—that can induce the differentiation of Tregs in vivo and in vitro [33,34]. The therapeutic efficacy of these microbes in regulating mucosal and systemic inflammation in human will be important to evaluate.

Similar to the Clostridia, segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) promote immunity without inducing overt intestinal inflammation. In particular, SFB penetrate the mucus layer and bind tightly to the epithelial surface of the ileum where they induce CD4+ T helper cells that produce IL-17a, IL-17f, and IL-22 (called Th17 cells) [35]. Colonization of mice with SFB can protect against concurrent infectious colitis [35]. In contrast, SFB colonization can also promote systemic Th17 cell activation that supports inflammatory arthritis in the K/BxN mouse model [36] and exacerbates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice [37]. The dichotomy of Th17 in promoting barrier protection at the mucosal surface and supporting inflammation systemically may underlie the differential effects of anti-IL17 therapy seen clinically in psoriasis compared to inflammatory bowel disease [38].

The potential effect of luminal microbes on systemic CD4+ T cell responses raises the question of cognate antigen specificity of these cells. While the concept of “molecular mimicry”—cross-activation by sequence similarity in self-antigen—at distal sites of inflammation may be consistent with microbial specificity, an alternate theory is that inflammatory micro-environments regulate the quality of effector lymphocyte differentiation independently of cognate antigen [39]. By cloning the TCRs of Th17 cells from the small intestine of mice colonized with SFB and expressing them in a hybridoma reporter system, we found that most TCRs were indeed responsive to two immunodominant epitopes in SFB. Confirming the cognate antigen specificity of SFB-induced Th17, co-transfer of cells expressing transgenic TCRs specific for SFB or ovalbumin resulted in Th17 polarization of the SFB transgenic TCRs only [40]. Moreover, concomitant exposure of mice to both SFB and Listeria monocytogenes resulted in Th17 polarization of SFB-specific T cells and Th1 polarization of Listeria-specific T cells suggesting specificity of the micro-environment and antigen delivery in guiding T cell polarization. As such, genetic insertion of the immunodominant SFB epitope into Listeria resulted in Th1 polarization of SFB-specific T cells. In contrast, acute infection with Toxoplasma gondii strongly promotes a stereotypic Th1 response and can act in trans to promote non-cognate, long-lived Th1 memory responses to flagellin antigens expressed by the commensal microbiota [41]. These differences may reflect distinct interactions with the mucosal barrier or particular subsets of MNPs and potentially contribute to systemic autoimmunity.

Viruses and Transkingdom Interactions Regulate Immunity

Enteric viruses are not only a frequent causative agent of human GI disease, but active participants in regulating the outcome of commensalism, including host immunity and microbial homeostasis. Recent results using a positive-strand RNA Calicivirus endemic to mouse facilities (called mouse norovirus or MNV) revealed the ability of a single virus to restore the altered intestinal pathology and lymphocyte function associated with either germ-free or antibiotic treated mice [42]. While the dependence of these findings on the host’s innate response to IFNα production reflects a potential key role for co-evolution of eukaryotic viruses with the intestinal immune system of mammals, immune cell activation induced by MNV in the context of genetic susceptibility (for example, mutations in ATG16L associated with IBD) results in aberrant Paneth cell function and increased disease susceptibility.

Similarly reflecting potential co-evolution, recent reports revealed the importance of “transkingdom interactions” between bacteria and viruses, which have developed systems (both direct and indirect) to regulate each other. Seminal work from Skip Virgin’s lab has identified the importance IFN lamba, another type I IFN, which is induced by commensal microbiota [43] and controls the persistence of MNV [44]. The effect of these signals in the intestine at the steady state or during systemic inflammatory disease will need to be assessed. Reciprocally, viruses likely help shape the bacterial microbiome. Analysis of dsDNA virus-like particles in IBD patient cohorts revealed a significant expansion of Caudovirales bacteriophages, which correlate with significant changes in the bacterial microbiome [45]. Animal models to test the ability of these prokaryotic viruses to regulate the bacterial microbiome in a “predator-prey” fashion during physiology and therapy will be an important area for future investigation.

In addition to bacteria and viruses, helminth colonization of the intestine is frequent, particularly within the developing world. Notable correlations with the ability to control pathogen infection (including M. tuberculosis, HIV, and Plasmodium) have been established, but the mechanisms by which they modulate intestinal and systemic immunity is the subject of ongoing research. Recent work identified a key mechanistic role for helminth-mediated induction (Heligomosomoides polygrus and Schistosoma mansoni) of type 2 immunity (predominantly IL-4) to allow for a permissive environment for viral re-activation [46]. Similar results hold using another helminth, Trichinella, in blunting the CD8+ T cell response to coinfection with a mouse norovirus [47]. Notably, these effects depend on the immunomodulatory function of the helminth-derived molecule Ym1 and STAT6-dependent alternative activation of macrophages, but are independent of the microbiota. Finally, in addition to helminths, fungi and fungal-derived molecules play a critical role in immunomodulation [48].

Defining the Immune-Relevant Bacteria in Autoimmunity

Sequencing technology has revolutionized our understanding of microbiota composition, both in health and disease. The next phase of this revolution is to understand the functional elements of the microbial organ and the ability to target key markers diagnostically and therapeutically. From an autoimmune perspective, it will be important to understand which of the luminal microbiota are recognized by the host immune system. Analysis of the microbiome recognized by IgA has revealed an enrichment in key microbes with dominant immunological effects in mice, including SFB discussed above [49]. Sentinel species have been identified from IBD patients [49] and malnourished individuals [50] that can dominantly transfer susceptibility to intestinal inflammation in mouse models. Further work is needed to apply these strategies to define the microbes mediating systemic autoimmunity.

Conclusions

The gut microbiome constitutes a critical microbial organ with coordinated interactions that shape host immunity. Expanding evidence suggests that a dynamic interaction between microbes and environmental cues (including diet and medicines) exist within the microbial organ that shape mucosal and systemic immunity. The clinical relevance of a critical developmental window in microbiome development with long-lasting implications for metabolic health will need to be explored in autoimmunity. Key bacteria and viruses provide critical regulation of mucosal and systemic immunity in mouse models, but the identification of immune-relevant bacteria in human autoimmunity will help focus our investigation on the microbial signals driving disease. Emerging research in this field will yield new insights into both diagnostic and therapeutic targets of autoimmunity.

Key points.

- Environmental cues shape the microbiome’s impact on immunity

- Commensal microbiota promote homeostatic regulation of immunity

- Viruses and transkingdom interactions regulate immunity

- Therapeutic opportunities will be derived from defining immune-relevant bacteria in autoimmunity

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Gretchen Diehl and Jim Castellanos for their critiques.

Financial support and sponsorship

The work was supported by the NIH (DK083256-02), the American Gastroenterological Association (R.S.L.) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (D.R.L.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None

Contributor Information

Randy S. Longman, Jill Roberts Institute for IBD Research, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, Belfer Research Building, 413 E. 69th Street, Room 514, New York, NY 10021

Dan R. Littman, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Department of Pathology, New York University School of Medicine, Skirball Institute, 540 First Avenue, Lab 2-17, New York, NY

References

- 1.Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, Purdom E, Dethlefsen L, Sargent M, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Relman DA. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science. 2005;308(5728):1635–1638. doi: 10.1126/science.1110591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1022–1023. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, Mende DR, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464(7285):59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, Sogin ML, Jones WJ, Roe BA, Affourtit JP, Egholm M, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457(7228):480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmody RN, Gerber GK, Luevano JM, Jr, Gatti DM, Somes L, Svenson KL, Turnbaugh PJ. Diet dominates host genotype in shaping the murine gut microbiota. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17(1):72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7**.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, Fischbach MA, Biddinger SB, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505(7484):559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. This study provided a seminal description of the variance in microbiota composition and function in geographically distinct communities as well as stereotypical changes from infancy to adulthood within the cohort. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP, Heath AC, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486(7402):222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suez J, Korem T, Zeevi D, Zilberman-Schapira G, Thaiss CA, Maza O, Israeli D, Zmora N, Gilad S, Weinberger A, Kuperman Y, et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature. 2014;514(7521):181–186. doi: 10.1038/nature13793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devkota S, Wang Y, Musch MW, Leone V, Fehlner-Peach H, Nadimpalli A, Antonopoulos DA, Jabri B, Chang EB. Dietary-fat-induced taurocholic acid promotes pathobiont expansion and colitis in il10−/− mice. Nature. 2012;487(7405):104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature11225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chassaing B, Koren O, Goodrich JK, Poole AC, Srinivasan S, Ley RE, Gewirtz AT. Dietary emulsifiers impact the mouse gut microbiota promoting colitis and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2015;519(7541):92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature14232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scher JU, Sczesnak A, Longman RS, Segata N, Ubeda C, Bielski C, Rostron T, Cerundolo V, Pamer EG, Abramson SB, Huttenhower C, et al. Expansion of intestinal prevotella copri correlates with enhanced susceptibility to arthritis. Elife. 2013;2:e01202. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, Buffa JA, Org E, Sheehy BT, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Li L, Smith JD, et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of l-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013;19(5):576–585. doi: 10.1038/nm.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saha JR, Butler VP, Jr, Neu HC, Lindenbaum J. Digoxin-inactivating bacteria: Identification in human gut flora. Science. 1983;220(4594):325–327. doi: 10.1126/science.6836275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15*.Haiser HJ, Gootenberg DB, Chatman K, Sirasani G, Balskus EP, Turnbaugh PJ. Predicting and manipulating cardiac drug inactivation by the human gut bacterium eggerthella lenta. Science. 2013;341(6143):295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.1235872. This study used high-throughput sequencing and comparative genomics to identify the operon regulating within E. lenta regulating digoxin and provides a template for the mechanistic investigation of microbial regulation of xenobiotics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith MI, Yatsunenko T, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Mkakosya R, Cheng J, Kau AL, Rich SS, Concannon P, Mychaleckyj JC, Liu J, et al. Gut microbiomes of malawian twin pairs discordant for kwashiorkor. Science. 2013;339(6119):548–554. doi: 10.1126/science.1229000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17**.Subramanian S, Huq S, Yatsunenko T, Haque R, Mahfuz M, Alam MA, Benezra A, DeStefano J, Meier MF, Muegge BD, Barratt MJ, et al. Persistent gut microbiota immaturity in malnourished bangladeshi children. Nature. 2014;510(7505):417–421. doi: 10.1038/nature13421. Both Smith et al and Subramanian et al. provide data for the seminal discovery that durable changes in the microbiome contribute to a malnourished phenotype. This phenotype is transferrable to germ free animals and therapeutically targeted with antibiotics. These data support the clinical implication that antibiotic therapy in addition to nutrition is required to combat severe malnutrition. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18**.Cox LM, Yamanishi S, Sohn J, Alekseyenko AV, Leung JM, Cho I, Kim SG, Li H, Gao Z, Mahana D, Zarate Rodriguez JG, et al. Altering the intestinal microbiota during a critical developmental window has lasting metabolic consequences. Cell. 2014;158(4):705–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.052. Extending the findings of Smith and Subramanian, this study identifies a critical developmental window altered by low dose antibiotics which confers durable effects on the microbiome with long-lasting metabolic consequences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hooper LV, Macpherson AJ. Immune adaptations that maintain homeostasis with the intestinal microbiota. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(3):159–169. doi: 10.1038/nri2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longman RS, Yang Y, Diehl GE, Kim SV, Littman DR. Microbiota: Host interactions in mucosal homeostasis and systemic autoimmunity. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2013;78:193–201. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2013.78.020081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21**.Diehl GE, Longman RS, Zhang JX, Breart B, Galan C, Cuesta A, Schwab SR, Littman DR. Microbiota restricts trafficking of bacteria to mesenteric lymph nodes by cx(3)cr1(hi) cells. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature11809. This study provides genetic evidence that CX3CR1+ intestinal mononuclear phagocytes can migrate to secondary lymph organs with non-invasive luminal antigens defining them as central regulators of adaptive immunity to luminal microbes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonnenberg GF, Monticelli LA, Elloso MM, Fouser LA, Artis D. Cd4(+) lymphoid tissue-inducer cells promote innate immunity in the gut. Immunity. 2011;34(1):122–134. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zenewicz LA, Yancopoulos GD, Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Stevens S, Flavell RA. Innate and adaptive interleukin-22 protects mice from inflammatory bowel disease. Immunity. 2008;29(6):947–957. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukherjee S, Zheng H, Derebe MG, Callenberg KM, Partch CL, Rollins D, Propheter DC, Rizo J, Grabe M, Jiang QX, Hooper LV. Antibacterial membrane attack by a pore-forming intestinal c-type lectin. Nature. 2014;505(7481):103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature12729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goto Y, Obata T, Kunisawa J, Sato S, Ivanov II, Lamichhane A, Takeyama N, Kamioka M, Sakamoto M, Matsuki T, Setoyama H, et al. Innate lymphoid cells regulate intestinal epithelial cell glycosylation. Science. 2014;345(6202):1254009. doi: 10.1126/science.1254009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hooper LV. Immunology. Innate lymphoid cells sweeten the pot. Science. 2014;345(6202):1248–1249. doi: 10.1126/science.1259808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zigmond E, Varol C, Farache J, Elmaliah E, Satpathy AT, Friedlander G, Mack M, Shpigel N, Boneca IG, Murphy KM, Shakhar G, et al. Ly6c hi monocytes in the inflamed colon give rise to proinflammatory effector cells and migratory antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 2012;37(6):1076–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Longman RS, Diehl GE, Victorio DA, Huh JR, Galan C, Miraldi ER, Swaminath A, Bonneau R, Scherl EJ, Littman DR. Cx3cr1+ mononuclear phagocytes support colitis-associated innate lymphoid cell production of il-22. J Exp Med. 2014;211(8):1571–1583. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satoh-Takayama N, Serafini N, Verrier T, Rekiki A, Renauld JC, Frankel G, Di Santo JP. The chemokine receptor cxcr6 controls the functional topography of interleukin-22 producing intestinal innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2014;41(5):776–788. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olszak T, An D, Zeissig S, Vera MP, Richter J, Franke A, Glickman JN, Siebert R, Baron RM, Kasper DL, Blumberg RS. Microbial exposure during early life has persistent effects on natural killer t cell function. Science. 2012;336(6080):489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.1219328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31*.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Oshima K, Suda W, Nagano Y, Nishikawa H, Fukuda S, Saito T, Narushima S, Hase K, Kim S, et al. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature. 2013;500(7461):232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature12331. Defined key Clostridial within cluster IV, XIVa and XVIII which expand colonic Tregs under homeostatic conditions and attenuate models of colitis and allergic diarrhea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gevers D, Kugathasan S, Denson LA, Vazquez-Baeza Y, Van Treuren W, Ren B, Schwager E, Knights D, Song SJ, Yassour M, Morgan XC, et al. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset crohn’s disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15(3):382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, Nakanishi Y, Uetake C, Kato K, Kato T, Takahashi M, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory t cells. Nature. 2013;504(7480):446–450. doi: 10.1038/nature12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly YM, Glickman JN, Garrett WS. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341(6145):569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, Brodie EL, Shima T, Karaoz U, Wei D, Goldfarb KC, Santee CA, Lynch SV, Tanoue T, et al. Induction of intestinal th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139(3):485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu HJ, Ivanov II, Darce J, Hattori K, Shima T, Umesaki Y, Littman DR, Benoist C, Mathis D. Gut-residing segmented filamentous bacteria drive autoimmune arthritis via t helper 17 cells. Immunity. 2010;32(6):815–827. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee YK, Menezes JS, Umesaki Y, Mazmanian SK. Microbes and health sackler colloquium: Proinflammatory t-cell responses to gut microbiota promote experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000082107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hueber W, Sands BE, Lewitzky S, Vandemeulebroecke M, Reinisch W, Higgins PD, Wehkamp J, Feagan BG, Yao MD, Karczewski M, Karczewski J, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-il-17a monoclonal antibody, for moderate to severe crohn’s disease: Unexpected results of a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gut. 2012;61(12):1693–1700. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lochner M, Berard M, Sawa S, Hauer S, Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Fernandez TD, Snel J, Bousso P, Cerf-Bensussan N, Eberl G. Restricted microbiota and absence of cognate tcr antigen leads to an unbalanced generation of th17 cells. J Immunol. 2011;186(3):1531–1537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40*.Yang Y, Torchinsky MB, Gobert M, Xiong H, Xu M, Linehan JL, Alonzo F, Ng C, Chen A, Lin X, Sczesnak A, et al. Focused specificity of intestinal th17 cells towards commensal bacterial antigens. Nature. 2014;510(7503):152–156. doi: 10.1038/nature13279. Defined the specificity of intestinal Th17 repertoire for antigens encoded by SFB suggesting that effector function is matched with microenvironment produced by specific bacteria in a tissue-specific fashion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hand TW, Dos Santos LM, Bouladoux N, Molloy MJ, Pagan AJ, Pepper M, Maynard CL, Elson CO, 3rd, Belkaid Y. Acute gastrointestinal infection induces long-lived microbiota-specific t cell responses. Science. 2012;337(6101):1553–1556. doi: 10.1126/science.1220961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kernbauer E, Ding Y, Cadwell K. An enteric virus can replace the beneficial function of commensal bacteria. Nature. 2014;516(7529):94–98. doi: 10.1038/nature13960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baldridge MT, Nice TJ, McCune BT, Yokoyama CC, Kambal A, Wheadon M, Diamond MS, Ivanova Y, Artyomov M, Virgin HW. Commensal microbes and interferon-lambda determine persistence of enteric murine norovirus infection. Science. 2015;347(6219):266–269. doi: 10.1126/science.1258025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44**.Nice TJ, Baldridge MT, McCune BT, Norman JM, Lazear HM, Artyomov M, Diamond MS, Virgin HW. Interferon-lambda cures persistent murine norovirus infection in the absence of adaptive immunity. Science. 2015;347(6219):269–273. doi: 10.1126/science.1258100. Work by Baldridge et al and Nice et al discovered a critical role for IFN lambda as the effector regulator of commensal bacteria on the outcome on intestinal virus persistence. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45**.Norman JM, Handley SA, Baldridge MT, Droit L, Liu CY, Keller BC, Kambal A, Monaco CL, Zhao G, Fleshner P, Stappenbeck TS, et al. Disease-specific alterations in the enteric virome in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2015;160(3):447–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.002. This work provides the first characterization of virus like particles from fecal DNA and revealed a potential role for Caudovirales bacteriophages in regulating the changes associated with the IBD microbiome. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reese TA, Wakeman BS, Choi HS, Hufford MM, Huang SC, Zhang X, Buck MD, Jezewski A, Kambal A, Liu CY, Goel G, et al. Coinfection. Helminth infection reactivates latent gamma-herpesvirus via cytokine competition at a viral promoter. Science. 2014;345(6196):573–577. doi: 10.1126/science.1254517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osborne LC, Monticelli LA, Nice TJ, Sutherland TE, Siracusa MC, Hepworth MR, Tomov VT, Kobuley D, Tran SV, Bittinger K, Bailey AG, et al. Coinfection. Virus-helminth coinfection reveals a microbiota-independent mechanism of immunomodulation. Science. 2014;345(6196):578–582. doi: 10.1126/science.1256942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Underhill DM, Iliev ID. The mycobiota: Interactions between commensal fungi and the host immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(6):405–416. doi: 10.1038/nri3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palm NW, de Zoete MR, Cullen TW, Barry NA, Stefanowski J, Hao L, Degnan PH, Hu J, Peter I, Zhang W, Ruggiero E, et al. Immunoglobulin a coating identifies colitogenic bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2014;158(5):1000–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kau AL, Planer JD, Liu J, Rao S, Yatsunenko T, Trehan I, Manary MJ, Liu TC, Stappenbeck TS, Maleta KM, Ashorn P, et al. Functional characterization of iga-targeted bacterial taxa from undernourished malawian children that produce diet-dependent enteropathy. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(276):276ra224. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa4877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]