Contributions of ubiquitin- and PCNA-binding domains to the activity of Polymerase η in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (original) (raw)

Abstract

Bypassing of DNA lesions by damage-tolerant DNA polymerases depends on the interaction of these enzymes with the monoubiquitylated form of the replicative clamp protein, PCNA. We have analyzed the contributions of ubiquitin and PCNA binding to damage bypass and damage-induced mutagenesis in Polymerase η (encoded by RAD30) from the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. We report here that a ubiquitin-binding domain provides enhanced affinity for the ubiquitylated form of PCNA and is essential for in vivo function of the polymerase, but only in conjunction with a basal affinity for the unmodified clamp, mediated by a conserved PCNA interaction motif. We show that enhancement of the interaction and function in damage tolerance does not depend on the ubiquitin attachment site within PCNA. Like its mammalian homolog, budding yeast Polymerase η itself is ubiquitylated in a manner dependent on its ubiquitin-binding domain.

INTRODUCTION

Replicative bypass of DNA damage by translesion synthesis (TLS) is essential for the proliferation of cells in the presence of genotoxic agents, but also to overcome lesions caused by the spontaneous decay of DNA in an aqueous environment (1,2). Replicative DNA polymerases are poorly equipped for TLS, because their catalytic centers are optimized for an unperturbed primer-template junction. Most organisms, therefore, harbor specialized damage-tolerant polymerases with more relaxed active sites that can accommodate a variety of lesions in the template strand (3–5). Conserved in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, the Y-family of DNA polymerases comprises a group of enzymes dedicated to TLS (6). While the genome of budding yeast encodes only two Y-family polymerases, Polη and Rev1, at least four different enzymes with varying specificities and preferences for different types of lesions are available to human cells.

One inevitable consequence of their ability to synthesize across DNA lesions is the overall reduced fidelity of TLS polymerases, even on undamaged templates (7). The replicative bypass of DNA lesions therefore contributes significantly to the mutagenic effect of DNA-damaging agents (8), and it is not surprising that the activity of the damage-tolerant polymerases is tightly regulated in order to prevent the accumulation of unwanted mutations due to unrestrained activity of these error-prone enzymes. In eukaryotes, the principal mechanism of damage-induced activation of TLS polymerases involves the sliding clamp, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). PCNA acts as a processivity factor for replicative polymerases, but also as a binding platform for a large number of other proteins involved in the coordination of events at the replication fork (9). Many of these proteins, including some of the Y-family polymerases, bind PCNA via a conserved motif, termed PCNA interacting peptide (PIP) (10). Covalent modification of PCNA by ubiquitin or SUMO was found to modulate the properties of the clamp and to regulate access of alternative sets of accessory factors to the site of replication (11–16). Specifically, genetic studies indicate that PCNA monoubiquitylation at lysine (K) 164 by the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) Rad6 and the ubiquitin ligase (E3) Rad18 is a prerequisite for the activation of all damage-tolerant polymerases in yeast (15), and preferential interactions of TLS polymerases Polη, Polκ, Polι and Rev1 with the modified form of the clamp have now been demonstrated in mammalian cells (12,16–20), providing strong support for a model that explains the recruitment of damage-tolerant polymerases to stalled replication forks by means of PCNA ubiquitylation.

The identification of two novel types of ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs), termed UBM and UBZ (18), has recently uncovered the molecular basis for the observed enhancement of PCNA binding by ubiquitylation. These motifs are present in one or two copies in all the mammalian Y-family polymerases and were found to directly bind ubiquitin in vitro. As they reside outside the catalytic domains, they do not affect polymerase activity of the TLS enzymes, but rather act by modulating their interactions and localization (18,20). Interestingly, they are also responsible for the ubiquitylation of the polymerases themselves, a phenomenon whose significance is not yet understood, but is characteristic for other ubiquitin-binding proteins as well (18–20).

Polη is a Y-family polymerase conserved in yeast and mammals, with a strong preference for cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) induced by ultraviolet (UV) radiation (21,22). It inserts the correct nucleotides opposite a thymine CPD, but is less efficient and highly inaccurate in the bypass of other lesions (23–26). In humans, defects in Polη result in a hereditary disease, Xeroderma pigmentosum variant (XP-V), involving photosensitivity and a predisposition to skin cancer (22,27). PCNA stimulates the activity of Polη without enhancing its processivity, and a PIP domain at the carboxy (C)-terminus of the protein (Figure 1A, B) was found to be required for interaction with the clamp and function in vivo (28). A UBZ domain was identified in the C-terminal region of human Polη (Figure 1A, C) and shown to convey ubiquitin binding and recruitment to damage-induced nuclear foci (18,20). Expression of a Polη allele carrying a point mutation in the UBZ domain failed to fully complement the UV sensitivity of XP-V cells without affecting polymerase activity, indicating that an intact UBZ domain is required for Polη function in vivo (18).

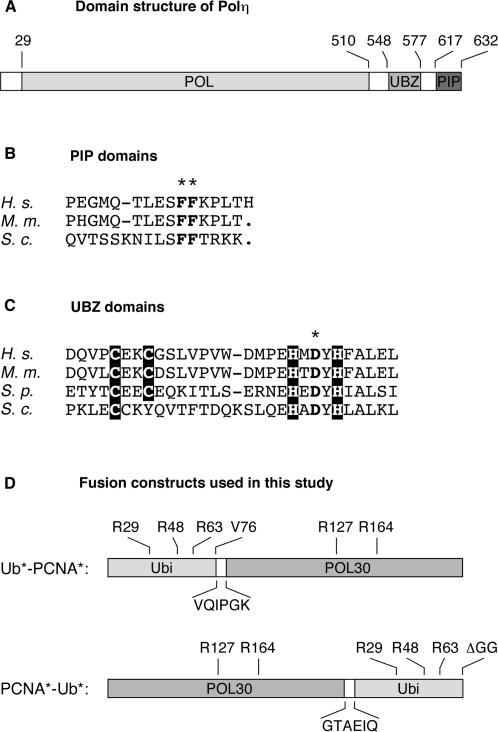

Figure 1.

Structure of Polη and the constructs used in this study. (A) Domain structure of Polη, indicating the positions of the polymerase domain (POL), the UBZ domain and the PCNA-interacting peptide (PIP), numbered according to the budding yeast protein. (B) Sequence alignment of Polη PIP domains from human (H. s.), mouse (M. m.) and budding yeast (S. c.). A dash indicates a gap in the alignment. The PIP* mutant was generated by changing the two conserved phenylalanine residues (indicated by an asterisk) to alanine. This change is known to disrupt the interaction with PCNA without affecting the overall structure of the protein (28). (C) Sequence alignment of Polη UBZ domains. Conserved cysteine and histidine residues are shaded in black. The conserved aspartate residue indicated by an asterisk was changed to alanine in order to create the UBZ* mutant in analogy to the mammalian protein (18). (D) Structure of the linear fusions of ubiquitin and PCNA used for analysis of protein–protein interactions and in vivo function. Mutations that prevent ubiquitin polymerization, conjugation and processing are indicated above and sequences of the linker peptides below each construct.

In Polη and Polκ, the UBZ domains are characterized by a mononuclear Zinc finger (UBZ) of the C2H2 or C2HC type, respectively (18). The corresponding sequence within budding yeast Polη, encoded by the RAD30 gene (29,30), differs considerably from that of the mammalian homolog, and one of the conserved cysteine residues is replaced by a tyrosine (Figure 1C). Moreover, we were unable to detect binding of a recombinant C-terminal fragment comprising the putative UBZ domain and the PIP motif, or of full-length Rad30 from total yeast cell lysate, to free ubiquitin or ubiquitin chains (our unpublished results). We have therefore examined the relevance of the putative UBZ domain for physical interactions with the modified clamp and biological function of Polη in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. We show here that the domain fulfills the expected function in yeast, but only in conjunction with an intact PIP domain. In addition, we have characterized the requirements for ubiquitylation of Polη itself, and we provide evidence that the exact molecular arrangement of ubiquitin and PCNA is not critical for recruitment of Polη and effective damage bypass in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmids

Standard procedures were followed for the cultivation and manipulation of S. cerevisiae. Unless otherwise noted, yeast strains (rad30::HIS3, rad5::HIS3, rad18::TRP1, rad6::HIS3, rev1::URA3, rev3::KanMX and appropriate combinations) are derived from DF5 and have been described previously (31). For genetic analysis of mutants in the RAD30 gene, a rad30 or rad30 rad5 deletion strain was transformed with shuttle vectors based on YIplac128 (32), which carried the WT or mutated RAD30 open reading frame (ORF) under the control of the endogenous RAD30 promoter, for integration into the LEU2 locus. The empty vector YIplac128 served as a negative control. The RAD30 vectors were constructed by inserting a PCR product comprising the ORF (SmaI-PstI) flanked by 500 bp of RAD30 upstream region (SacI-SmaI) and a transcription terminator derived from pGBT9 (Clontech, PstI-SphI). Mutations in the UBZ (D570A) and/or PIP motif (FF627/628AA) were introduced by PCR-based mutagenesis. All constructs were sequenced throughout the ORF. For two-hybrid analysis, the ORFs were subcloned into the vectors pGAD424 and pGBT9 (Clontech). In addition, a truncated version of RAD30 encoding amino acids 538–632 was constructed. The ORFs of pol30(K127/164R), ubiquitin and the fusion constructs shown in Figure 1D were assembled by PCR and cloned (Ub*-PCNA*: BamHI-PstI; PCNA*-Ub*: SmaI-PstI) into the two-hybrid vectors, into pQE30, and into YIplac128 under control of the POL30 promoter, in analogy to the expression vector for PCNA described previously (15). For detection of Polη on western blots, a sequence encoding the 9myc-epitope was appended to the RAD30 ORF as described (31). For in vivo pull-down experiments, a sequence encoding His7-tagged ubiquitin was generated by PCR and cloned (BamHI-PstI) into an episomal plasmid based on YEplac181 or YEplac195 (32), under control of the CUP1 promoter (428 bp of upstream sequence, SacI-BamHI) and the transcription terminator from pGBT9 (PstI-SphI).

Two-hybrid analysis

Analysis of protein–protein interactions in the two-hybrid system was performed in PJ64-4A, as described previously (32). Selection for the presence of the bait and prey plasmids was carried out on synthetic medium lacking tryptophan and leucine, and positive interactions were scored by growth on medium further lacking histidine or histidine and adenine.

Measurements of UV sensitivities and UV-induced mutation frequencies

UV sensitivities were determined by plating defined numbers of cells onto YPD medium, irradiation at 254 nm in a UV crosslinker (Stratalinker 2400 by Stratagene), incubation in the dark for 3 days, and colony counting. UV-induced mutation frequencies in the CAN1 locus were measured similarly by comparing the numbers of can1R mutants at a given UV dose, selected on synthetic medium without arginine containing 30 µg/ml canavanine, with the numbers of survivors on YPD exposed to the same UV dose. Standard deviations were calculated from triplicate measurements.

In vivo analysis of yeast proteins

Total cell lysates were prepared as described (33). PCNA and the fusion constructs were detected by western blot with an anti-Pol30 antibody (15). For detection of Polη modification, strains bearing 9myc-tagged RAD30 (WT, rad6, rad18 or rad30 mutants) were transformed with an episomal vector encoding His7-tagged ubiquitin (see above). Cultures were grown in selective medium containing 0.1 mM CuSO4. Pull-downs on Ni-NTA agarose from total lysates were performed under denaturing conditions as described previously (11,15), and the Rad30 protein was detected by western blot using a monoclonal anti-myc antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Detection of phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) with a monoclonal antibody (Molecular Probes) served as loading control.

In vitro analysis of protein interactions

Recombinant PCNA*, Ub*-PCNA* and PCNA*-Ub* were produced in E. coli by expression from pQE30 with an N-terminal His6-epitope. Proteins were purified by chromatography on Ni-NTA agarose and dialyzed against a buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol. Gel filtration analysis was performed at 2 µM PCNA on a Superdex 200 column as described (34). In vitro pull-down assays with GST fusion proteins were performed by immobilizing the GST-PCNA fusion protein (13) on glutathione Sepharose, incubation with the respective binding partner for 30 min at 30°C in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.05% Triton X-100, washing three times with the same buffer and eluting bound material by boiling in SDS sample buffer.

RESULTS

UBZ and PIP motifs jointly contribute to interaction of yeast Polη with ubiquitylated PCNA

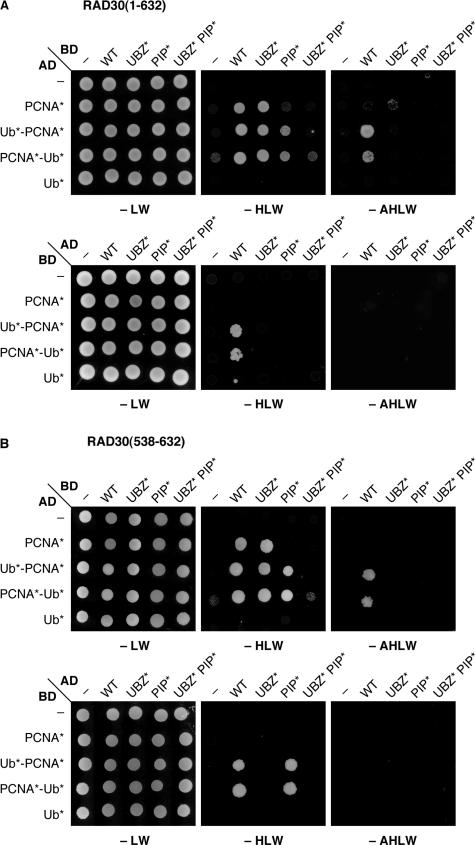

In order to analyze the interactions between Polη and ubiquitylated PCNA in the two-hybrid system, we constructed linear fusions of ubiquitin to the amino (N)- and the C-terminus of PCNA, respectively (Figure 1D). The lysine residues within PCNA and the ubiquitin moiety known to be involved in ubiquitin or SUMO conjugation were mutated to arginine to prevent further modification, and the C-terminus of ubiquitin was altered in order to prevent processing by isopeptidases or conjugation to other proteins. Using isolated ubiquitin (Ub*) and PCNA (PCNA*) carrying the same mutations as controls, these constructs were examined for binding to wildtype (WT) Rad30 or variants in which the PIP and/or the UBZ motif were inactivated by point mutations (Figure 1B, C). When PCNA* was fused to the GAL4 activation domain (AD) and Rad30 to the DNA-binding domain (BD), interaction depended on an intact PIP domain in Rad30 and was strong enough to activate the _HIS3_-, but not the ADE2 reporter in the two-hybrid system (Figure 2A, upper panel). Stronger signals with both reporter genes were observed with the two fusion constructs Ub*-PCNA* and PCNA*-Ub*. These interactions were affected by both PIP and UBZ domains. Mutation of either resulted in weakening of the interaction to the level of the interaction with PCNA*, and mutation of both completely abolished the signal. Reversal of the orientation in the two-hybrid system resulted in overall weaker signals: interaction was only visible with the fusions and depended on both UBZ and PIP (Figure 2A, lower panel). Very similar results were obtained with a C-terminal domain of Rad30 comprising the UBZ and PIP motifs (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Physical interactions between Rad30, PCNA and ubiquitin. Interactions were monitored in the two-hybrid system, based on fusions to the GAL4 activation (AD) and DNA-binding (BD) domains. Presence of the respective constructs was ensured by selection on plates lacking leucine and tryptophane (-LW), and interactions were scored by growth on plates lacking histidine or histidine and adenine (-HLW, -AHLW). (A) Interaction of Rad30 (WT) and the indicated mutants with PCNA*, ubiquitin (Ub*) and the linear fusions shown in Figure 1D. PCNA* and Ub* were mutated in the same manner as the fusion constructs. (B) same as in (A), but using an N-terminally truncated version of Rad30, comprising amino acids 538–632.

Notably, interaction with ubiquitin alone or a fusion of ubiquitin to an unrelated protein such as GFP (data not shown) was never observed in our system. Taken together, these findings suggest that the UBZ domain of Polη from budding yeast does contribute to ubiquitin binding, but this association is unlikely to be strong and may be effective only in conjunction with a basal affinity of Rad30 for PCNA, mediated by the PIP motif. Naturally, neither the two-hybrid system nor the linear fusions of ubiquitin and PCNA fully reflect the physiological arrangement of the interaction partners, which makes quantitative statements problematic. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the exact position of ubiquitin on PCNA was irrelevant in this context, such that UBZ-dependent enhancement of PCNA binding was detectable even though ubiquitin was not attached to its natural position, K164.

The UBZ domain is required for Polη function in translesion synthesis

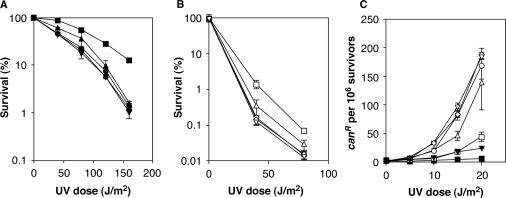

Having obtained evidence for a contribution of the UBZ domain to ubiquitin binding, we analyzed the consequences of mutations in this domain for the function of Rad30 in DNA damage tolerance. Since the Rad30 protein, like human Polη, is largely selective for the bypass of UV-induced CPDs, we used UV radiation as a damaging agent. Mutation of the UBZ domain resulted in a UV sensitivity close to that of a rad30 deletion or a mutant in the PIP motif (Figure 3A). Similar results were obtained in a rad5 background, where overall UV sensitivities are exacerbated due to the abolishment of error-free damage avoidance (Figure 3B). In this background, the rad30(PIP*) mutant displayed a substantial, but not complete loss of function, which is consistent with previous results that have demonstrated a somewhat milder phenotype for modification by point mutations as compared to deletion of the PIP motif in this background (28). These results demonstrate a contribution of the Rad30 UBZ domain to resistance towards UV-induced DNA damage.

Figure 3.

The Rad30 UBZ domain is required for Polη-dependent error-free bypass of UV damage in yeast. (A) Effect of UBZ and PIP domain mutations on sensitivities towards UV radiation. Strains bearing a rad30 deletion were complemented with WT RAD30 or mutants in the UBZ and/or PIP domain on integrative vectors. The empty vector served as control. (B) same as in (A), but using a rad5 rad30 deletion background. (C) UV-induced forward mutation frequencies in the CAN1 locus. Constructs used: RAD30 (squares), rad30, i.e. empty vector (inverted triangles), rad30(UBZ*) (circles), rad30(PIP*) (triangles), rad30(UBZ* PIP*) (diamonds). Filled symbols indicate _RAD_5, open symbols a rad5 background.

An alternative way of assessing the function of RAD30 in lesion bypass is the measurement of damage-induced mutation frequencies in a strain that is dependent on TLS for damage bypass because the error-free damage avoidance pathway has been inactivated. MacDonald et al. have shown that in a rad5 background, deletion of RAD30 results in a massive increase in UV-induced reversion frequencies (29), presumably due to the processing of lesions by error-prone, Polζ- and/or Rev1-dependent TLS in the absence of error-free, Polη-dependent bypass. This provides a sensitive tool to monitor the contribution of RAD30 to error-free TLS. When we determined forward mutation frequencies in the CAN1 locus in response to UV irradiation (Figure 3C), we found that rad30(UBZ*) afforded mutation frequencies comparable to those of the rad30 deletion, consistent with a complete loss of function, whereas rad30(PIP*) retained some residual activity. Again, these data provide evidence for an absolute requirement of the UBZ domain in yeast Polη.

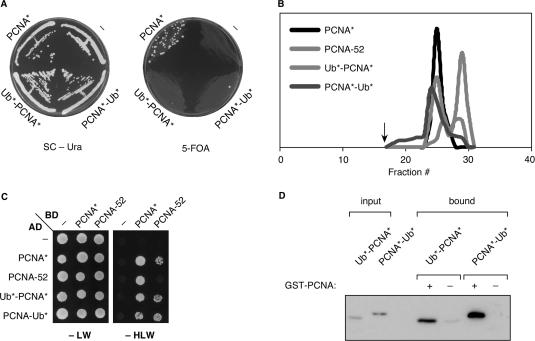

Linear fusions of ubiquitin and PCNA can partially substitute for loss of PCNA ubiquitylation

In order to determine whether the linear fusions between ubiquitin and PCNA reflected the physiological situation of naturally ubiquitylated PCNA to any degree, we examined their properties in vivo and in vitro. Figure 4A shows that the fusion proteins did not rescue the lethality of a pol30 deletion, indicating that vital functions of PCNA, such as promoting DNA replication, are affected by attaching ubiquitin to its N- or C-terminus. However, gel filtration analysis of the purified proteins indicated that both Ub*-PCNA* and PCNA*-Ub* exist as relatively stable homotrimers in solution, suggesting that the failure to support viability is not caused by a lack of trimerization (Figure 4B). Two-hybrid and in vitro pull-down assays showed that the fusion proteins can interact not only with themselves, but also with native PCNA* (Figure 4C, D). Thus, coexpression of the fusions with endogenous PCNA should result in the formation of mixed trimers, which could potentially take over the function of physiologically ubiquitylated PCNA in a strain unable to ubiquitylate endogenous PCNA, such as a rad18 mutant. We, therefore, expressed the two constructs, Ub*-PCNA* and PCNA*-Ub*, under the control of the POL30 promoter from an integrative vector in a rad18 strain (Figure 5A). As a control, we expressed unmodified pol30(K127/164R) (PCNA*) to the same level, as it has previously been shown that overexpression of POL30 or pol30(K164R) suppresses the damage sensitivity of rad18 mutants to some extent (11). We found that fusion of ubiquitin to the N- or C-terminus of PCNA significantly enhanced its ability to suppress the UV sensitivity of a rad18 mutant, whereas it had no effect in a WT background (Figure 5B). As expected, suppression was incomplete, consistent with the notion that the fusion proteins cannot be further ubiquitylated, which eliminates the error-free, polyubiquitin-dependent pathway of damage avoidance. In order to demonstrate that the observed suppression was in fact due to TLS, we reexamined UV sensitivities in a rad18 mutant that additionally carries deletions of the genes encoding the TLS polymerases, REV1, REV3 and RAD30. In this mutant (rad18 Δ_TLS_), expression of the fusion constructs had no effect on survival of DNA damage, indicating that Ub*-PCNA* and PCNA*-Ub* indeed exert their influence by means of the TLS polymerases. The enhanced UV sensitivity observed in the rad18 Δ_TLS_ strain compared to rad18 may be due to functions of REV3 independent of PCNA ubiquitylation (34,35). Taken together, these results indicate that linear fusions of ubiquitin and PCNA can partially substitute for the loss of endogenously ubiquitylated PCNA in DNA damage tolerance, and they suggest that the constructs used for interaction studies reflect the physiological situation to some degree.

Figure 4.

Properties of permanently ubiquitylated PCNA. (A) Fusions of PCNA to ubiquitin cannot rescue the lethality of a pol30 deletion. The linear fusion constructs of ubiquitin and PCNA shown in Figure 1D or a construct for expression of pol30(K127/164R) (PCNA*) under control of the POL30 promoter or an empty vector (“–“) were integrated in a pol30 strain expressing _WT POL_30 on a centromeric plasmid bearing the URA3 marker. Growth on plates containing 5-fluoroorotate (5-FOA) indicates viability after loss of the plasmid. The rare colonies arising from Ub*-PCNA* and PCNA*-Ub* on 5-FOA were analyzed by western blot and found to have maintained expression of PCNA despite loss of the URA3 marker. (B) Gel filtration analysis shows that Ub*-PCNA* and PCNA*-Ub* form homotrimers in solution with a stability approaching that of native PCNA*. A non-lethal allele defective in trimerization (PCNA-52) (47) was analyzed for comparison. Proteins were produced in E. coli with an N-terminal His6 epitope. An arrow indicates the void volume of the column. (C) Interaction of the PCNA constructs used in (B) in the two-hybrid system. (D) Subunit exchange between GST-PCNA and His6-tagged Ub*-PCNA* or PCNA*-Ub* in vitro. GST-PCNA was immobilized on glutathione Sepharose and incubated with the His6-tagged fusion protein, and bound material was analyzed by western blot (anti-His).

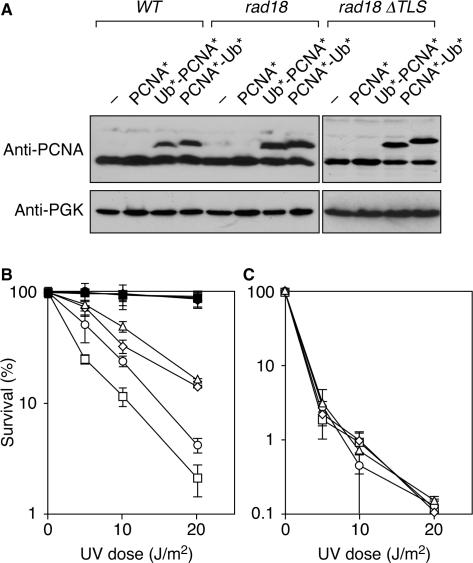

Figure 5.

In vivo function of permanently ubiquitylated PCNA. (A) Detection of PCNA by western blot (anti-Pol30) in total lysates from cells expressing the constructs described in the legend to Figure 4 in addition to endogenous PCNA. Detection of phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) was used as loading control. (B) UV sensitivities of the strains shown in (A): “–“, i.e. empty vector (squares), PCNA* (circles), Ub*-PCNA* (triangles), PCNA*-Ub* (diamonds). Filled symbols indicate WT host strains, open symbols a rad18 background. (C) UV sensitivities in the rad18 rad30 rev1 rev3 (rad18 Δ_TLS_) background, labeled as in (B).

Polη is ubiquitylated in vivo in a RAD6- and _RAD18_-independent manner

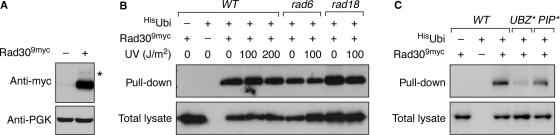

Ubiquitylation of UBD-containing proteins in a UBD-dependent manner has been observed previously (36,37), and mammalian Polη, Polτ and Rev1 were all found to be ubiquitylated in vivo (18,19). For detection of yeast Polη, we appended a 9myc-epitope to the protein's C-terminus (Figure 6A). On western blots, a faint band of higher molecular weight suggested a modified form. As shown in Figure 6B, Rad309myc was detected in Ni-NTA pull-downs performed under denaturing conditions from cells expressing His-tagged ubiquitin, suggesting that the modification was indeed monoubiquitin. We were interested to see whether ubiquitylation of Polη required any of the same conjugation factors that operate on PCNA, i.e. Rad6 and Rad18 (11). Figure 6B shows that the levels of modified Rad309myc were unchanged in the rad18 mutant and only marginally reduced in rad6, suggesting that either a different E2-E3 pair is responsible for the modification, or that the UBZ domain functions in an autocatalytic manner and affords modification independent of any additional E3 and not entirely relying on Rad6 as an E2. Relevance of the UBZ domain for Rad309myc modification was confirmed by a significant reduction in ubiquitylation of the UBZ* mutant (Figure 6C). In contrast, interaction with PCNA was dispensable, because modification of the PIP* mutant was comparable to that of WT Rad309myc (Figure 6C). Moreover, we did not observe an effect of DNA damage, suggesting that ubiquitylation of Polη in S. cerevisiae may not be regulated via the DNA damage response (Figure 6B). Thus, the physiological significance of this modification is still unclear.

Figure 6.

Budding yeast Polη is modified by monoubiquitin. (A) Detection of Rad309myc in a total cell lysate by western blot (anti-myc). A band of higher molecular weight, which might represent ubiquitylated Rad309myc, is indicated by an asterisk. (B) Monoubiquitylation of Rad30 does not depend on RAD6, RAD18 or UV damage. Ubiquitylated Rad309myc protein was detected by western blot (anti-myc) after isolation of total ubiquitylated proteins under denaturing conditions from a strain bearing His-tagged ubiquitin. Strains with untagged Rad30 or untagged ubiquitin were used as controls. The top panel shows the ubiquitylated Rad309myc protein isolated by pull-down of His-ubiquitin, while the bottom panel shows the levels of Rad309myc in the corresponding total cell extracts. (C) Monoubiquitylation of Rad30 depends on the UBZ*, but not on the PIP* domain mutant. A 9myc-epitope was appended to the mutant rad30 alleles in the strains used in Figure 3, and ubiquitylated Rad309myc was isolated and detected as in (B).

DISCUSSION

Our analysis of the UBZ motif of budding yeast Polη has revealed several parallels to the corresponding domain in its mammalian ortholog, but we have also made observations that will help generalize our understanding of UBDs in eukaryotic Y-family polymerases.

Ubiquitin binding by the UBZ domain

We have shown that, despite its variation in primary sequence, the UBZ domain from yeast Polη is functional in ubiquitin binding and contributes to an enhanced association of the polymerase with ubiquitylated PCNA. However, neither full-length yeast Polη nor its UBZ domain alone exhibited significant affinity for isolated, unconjugated ubiquitin. This situation differs from the mammalian system, where UBZ domains were first isolated by means of interaction with free ubiquitin in a two-hybrid screen, and the UBZ of Polη promoted binding to ubiquitin agarose in the context of the full-length polymerase (18). This suggests that the interaction of the yeast UBZ domain with ubiquitin might be weaker or more transient, possibly due to its divergent sequence, thus requiring a PIP-mediated basal affinity for PCNA as an obligatory interaction partner. In mammalian Polη, the relative contributions of PIP and UBZ domains to binding of ubiquitylated PCNA have not been analyzed. In human Polι, however, inactivation of the functionally related UBM domains had a much more severe effect on the affinity to a PCNA-ubiquitin fusion than mutation of the PIP domain (18), and in the Rev1 protein, constitutive damage-independent association with PCNA at replication foci was found to require an N-terminal BRCT domain (38), whereas the damage-induced enhancement of binding to the ubiquitylated clamp was mediated by the UBM domains (19). Thus, it appears that UBDs may vary substantially in their affinities to ubiquitin and might, therefore, not always function autonomously in their recognition of ubiquitylated target proteins.

Function of the UBZ domain in TLS

The single amino acid substitution introduced into the UBZ motif to abolish ubiquitin binding does not prevent the interaction of the mutated protein with unmodified PCNA in the two-hybrid system, and it is unlikely that this situation would be different in the case of chromatin-bound PCNA. Thus, the functions of the PIP and the UBZ motifs appear to be separable. Yet, analysis of damage sensitivities and mutation frequencies demonstrates that both domains are absolutely required for function in damage bypass and prevention of damage-induced mutagenesis in yeast Polη. Phenotypic analysis of human Polη was more ambiguous with respect to the relative importance of each motif (18). This absolute requirement for both PCNA and ubiquitin binding resembles the phenotype of yeast rev1 mutants in the BRCT and the UBM domains, which are both inactive with respect to TLS and damage-induced mutagenesis (19,38). Thus, analysis of the yeast proteins in the context of damage bypass can prove valuable when loss-of-function mutants in some of the mammalian Y-family polymerases are poorly accessible to genetic studies.

Flexibility in the site of ubiquitin attachment

Our study has shown that monoubiquitin attached to the N- or C-terminus of PCNA can partially overcome the need for PCNA ubiquitylation at its physiological site, K164, in mediating UBZ-dependent interaction with Polη in the two-hybrid system and also in terms of biological function in the context of TLS. Precedents for the functionality of linear fusion constructs have been reported for targets of ubiquitin as well as SUMO conjugation (39–42), but in many of these cases more than one lysine within the target protein can naturally serve as acceptor for the modifier. Given that both in vivo and in vitro PCNA is ubiquitylated exclusively at K164 (11,43), a redundancy in the positioning of the modifier is surprising. In molecular terms, simultaneous interactions involving both the UBZ domain and the PIP motif, which is known to interact with a region involving the interdomain connector loop of PCNA (44,45), must therefore involve significant flexibility either on the side of Polη itself or in the linkage between the C-terminus of ubiquitin and K164 of PCNA. Thus, in the case of PCNA, the ubiquitin acceptor site might reflect an arbitrary preference of the conjugating enzymes rather than a condition for functionality of the modified clamp. Considering that the fusion proteins cannot substitute for PCNA with respect to its essential function in DNA replication, however, K164 might also be one of a limited number of sites within the PCNA molecule that allows modification without disrupting vital interactions with other cellular factors.

Autoubiquitylation of ubiquitin-binding proteins

Finally, ubiquitylation of Polη appears to be conserved across the species and is not unexpected in light of the UBD-mediated modification of many other monoubiquitin-binding proteins, such as components of the endocytic pathway (36,39,46). We have now shown that, in the case of Polη, this phenomenon is largely independent of the conjugation factors responsible for the modification of PCNA or interaction with the clamp, but strongly dependent on the UBZ domain itself, as in mammalian Polη. This suggests either an involvement of a different set of E2 and E3 enzymes, or possibly an autocatalytic action of the UBD. In the latter scenario, the modification could result from interaction of the UBD with an activated ubiquitin moiety loaded onto an E2 (or potentially an E1) molecule, which would circumvent the need for a specific E2–E3 pair. It is yet unclear whether this reaction would be an inevitable consequence of the interaction between a UBD and activated ubiquitin and thus an irrelevant side reaction, or whether modification of UBD-containing proteins can serve as a regulatory strategy of blocking their own ubiquitin-binding properties in an intramolecular fashion (39). The inability of ubiquitylated mammalian Polη to bind ubiquitylated PCNA may suggest the latter (18); however, we did not observe any change in the extent of yeast Rad30 modification in response to DNA damage. Considering that the majority of Polη in yeast and mammals is not modified at any given time, it is difficult to imagine an effective regulatory scenario by modification of the polymerase. Likewise, the apparent absence of polyubiquitylated species argues against a proteolytic function of Polη modification. In order to gain insight into the relevance of this process, it will be necessary to identify the sites of modification and analyze the consequences of the relevant mutations.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Cancer Research UK, by a BioFuture grant from the German Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) and by the Young Investigator Programme of the European Molecular Biology Organisation (EMBO). Funding to the pay the Open Access publication charge was provided by Cancer Research UK.

References

- 1.Baynton K, Fuchs RP. Lesions in DNA: hurdles for polymerases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:74–79. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01524-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehmann AR. Replication of damaged DNA in mammalian cells: new solutions to an old problem. Mutat. Res. 2002;509:23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedberg EC, Gerlach VL. Novel DNA polymerases offer clues to the molecular basis of mutagenesis. Cell. 1999;98:413–416. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81970-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodgate R. A plethora of lesion-replicating DNA polymerases. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2191–2195. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.17.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang W. Damage repair DNA polymerases Y. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2003;13:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohmori H, Friedberg EC, Fuchs RP, Goodman MF, Hanaoka F, Hinkle D, Kunkel TA, Lawrence CW, Livneh Z, et al. The Y-family of DNA polymerases. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:7–8. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunkel TA. DNA replication fidelity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:16895–16898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pages V, Fuchs RP. How DNA lesions are turned into mutations within cells? Oncogene. 2002;21:8957–8966. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jónsson ZO, Hübscher U. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen: more than a clamp for DNA polymerases. BioEssays. 1997;19:967–975. doi: 10.1002/bies.950191106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warbrick E. The puzzle of PCNA's many partners. BioEssays. 2000;22:997–1006. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200011)22:11<997::AID-BIES6>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoege C, Pfander B, Moldovan GL, Pyrowolakis G, Jentsch S. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature. 2002;419:135–141. doi: 10.1038/nature00991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kannouche PL, Wing J, Lehmann AR. Interaction of human DNA polymerase η with monoubiquitinated PCNA: a possible mechanism for the polymerase switch in response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell. 2004;14:491–500. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papouli E, Chen S, Davies AA, Huttner D, Krejci L, Sung P, Ulrich HD. Crosstalk between SUMO and ubiquitin on PCNA is mediated by recruitment of the helicase Srs2p. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfander B, Moldovan GL, Sacher M, Hoege C, Jentsch S. SUMO-modified PCNA recruits Srs2 to prevent recombination during S phase. Nature. 2005;436:428–433. doi: 10.1038/nature03665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stelter P, Ulrich HD. Control of spontaneous and damage-induced mutagenesis by SUMO and ubiquitin conjugation. Nature. 2003;425:188–191. doi: 10.1038/nature01965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe K, Tateishi S, Kawasuji M, Tsurimoto T, Inoue H, Yamaizumi M. Rad18 guides polη to replication stalling sites through physical interaction and PCNA monoubiquitination. EMBO J. 2004;23:3886–3896. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bi X, Barkley LR, Slater DM, Tateishi S, Yamaizumi M, Ohmori H, Vaziri C. Rad18 regulates DNA polymerase κ and is required for recovery from S-phase checkpoint-mediated arrest. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;26:3527–3540. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3527-3540.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bienko M, Green CM, Crosetto N, Rudolf F, Zapart G, Coull B, Kannouche P, Wider G, Peter M, et al. Ubiquitin-binding domains in Y-family polymerases regulate translesion synthesis. Science. 2005;310:1821–1824. doi: 10.1126/science.1120615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo C, Tang T-S, Bienko M, Parker JL, Bielen AB, Sonoda E, Takeda S, Ulrich HD, Dikic I, et al. Ubiquitin-binding motifs in REV1 protein are required for its role in the tolerance of DNA damage. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;26:8892–8900. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01118-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plosky BS, Vidal AE, de Henestrosa AR, McLenigan MP, McDonald JP, Mead S, Woodgate R. Controlling the subcellular localization of DNA polymerases ι and η via interactions with ubiquitin. EMBO J. 2006;25:2847–2855. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson RE, Prakash S, Prakash L. Efficient bypass of a thymine-thymine dimer by yeast DNA polymerase, Polη. Science. 1999;283:1001–1004. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5404.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masutani C, Kusumoto R, Yamada A, Dohmae N, Yokoi M, Yuasa M, Araki M, Iwai S, Takio K, et al. The XPV (xeroderma pigmentosum variant) gene encodes human DNA polymerase η. Nature. 1999;399:700–704. doi: 10.1038/21447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Washington MT, Johnson RE, Prakash S, Prakash L. Fidelity and processivity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase η. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:36835–36838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.36835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bresson A, Fuchs RPP. Lesion bypass in yeast cells: Polη participates in a multi-DNA polymerase process. EMBO J. 2002;21:3881–3887. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuda T, Bebenek K, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Kunkel TA. Low fidelity DNA synthesis by human DNA polymerase η. Nature. 2000;404:1011–1013. doi: 10.1038/35010014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masutani C, Kusumoto R, Iwai S, Hanaoka F. Mechanisms of accurate translesion synthesis by human DNA polymerase η. EMBO J. 2000;19:3100–3109. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kannouche P, Stary A. Xeroderma pigmentosum variant and error-prone DNA polymerases. Biochimie. 2003;85:1123–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haracska L, Kondratick CM, Unk I, Prakash S, Prakash L. Interaction with PCNA is essential for yeast DNA polymerase η function. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:407–415. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald JP, Levine AS, Woodgate R. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD30 gene, a homologue of Escherichia coli dinB and umuC, is DNA damage inducible and functions in a novel error-free postreplication repair mechanism. Genetics. 1997;147:1557–1568. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.4.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roush AA, Suarez M, Friedberg EC, Radman M, Siede W. Deletion of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene RAD30 encoding an Escherichia coli DinB homolog confers UV radiation sensitivity and altered mutability. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1998;257:686–692. doi: 10.1007/s004380050698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ulrich HD, Jentsch S. Two RING finger proteins mediate cooperation between ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes in DNA repair. EMBO J. 2000;19:3388–3397. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gietz RD, Sugino A. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yaffe MP, Schatz G. Two nuclear mutations that block mitochondrial protein import in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1984;81:4819–4823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.15.4819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Northam MR, Garg P, Baitin DM, Burgers PM, Shcherbakova PV. A novel function of DNA polymerase zeta regulated by PCNA. EMBO J. 2006;25:4316–4325. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang H, Gibbs PE, Lawrence CW. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae rev6-1 mutation, which inhibits both the lesion bypass and the recombination mode of DNA damage tolerance, is an allele of POL30, encoding proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Genetics. 2006;173:1983–1989. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.058545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Fiore PP, Polo S, Hofmann K. When ubiquitin meets ubiquitin receptors: a signalling connection. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:491–497. doi: 10.1038/nrm1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hicke L, Schubert HL, Hill CP. Ubiquitin-binding domains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:610–621. doi: 10.1038/nrm1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo C, Sonoda E, Tang T-S, Parker JL, Bielen AB, Takeda S, Ulrich HD, Friedberg EC. REV1 protein interacts with PCNA: significance of the REV1 BRCT domain in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cell. 2006;23:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoeller D, Crosetto N, Blagoev B, Raiborg C, Tikkanen R, Wagner S, Kowanetz K, Breitling R, Mann M, et al. Regulation of ubiquitin-binding proteins by monoubiquitination. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:163–169. doi: 10.1038/ncb1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang TT, Wuerzberger-Davis SM, Wu ZH, Miyamoto S. Sequential modification of NEMO/IKKγ by SUMO-1 and ubiquitin mediates NF-κB activation by genotoxic stress. Cell. 2003;115:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00895-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson ES, Bartel B, Seufert W, Varshavsky A. Ubiquitin as a degradation signal. EMBO J. 1992;11:497–505. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05080.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sterner DE, Nathan D, Reindle A, Johnson ES, Berger SL. Sumoylation of the yeast Gcn5 protein. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1035–1042. doi: 10.1021/bi051624q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garg P, Burgers PM. Ubiquitinated proliferating cell nuclear antigen activates translesion DNA polymerases η and REV1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:18361–18366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505949102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gulbis JM, Kelman Z, Hurwitz J, O’Donnell M, Kuriyan J. Structure of the C-terminal region of p21(WAF1/CIP1) complexed with human PCNA. Cell. 1996;87:297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81347-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warbrick E, Lane DP, Glover DM, Cox LS. A small peptide inhibitor of DNA replication defines the site of interaction between the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Curr. Biol. 1995;5:275–282. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hicke L, Dunn R. Regulation of membrane protein transport by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2003;19:141–172. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.154617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ayyagari R, Impellizzeri KJ, Yoder BL, Gary SL, Burgers PM. A mutational analysis of the yeast proliferating cell nuclear antigen indicates distinct roles in DNA replication and DNA repair. Mol. Cell Biol. 1995;15:4420–4429. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]