Origins of a cyanobacterial 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase in plastid-lacking eukaryotes (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background

Plastids have inherited their own genomes from a single cyanobacterial ancestor, but the majority of cyanobacterial genes, once retained in the ancestral plastid genome, have been lost or transferred into the eukaryotic host nuclear genome via endosymbiotic gene transfer. Although previous studies showed that cyanobacterial gnd genes, which encode 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, are present in several plastid-lacking protists as well as primary and secondary plastid-containing phototrophic eukaryotes, the evolutionary paths of these genes remain elusive.

Results

Here we show an extended phylogenetic analysis including novel gnd gene sequences from Excavata and Glaucophyta. Our analysis demonstrated the patchy distribution of the excavate genes in the gnd gene phylogeny. The Diplonema gene was related to cytosol-type genes in red algae and Opisthokonta, while heterolobosean genes occupied basal phylogenetic positions with plastid-type red algal genes within the monophyletic eukaryotic group that is sister to cyanobacterial genes. Statistical tests based on exhaustive maximum likelihood analyses strongly rejected that heterolobosean gnd genes were derived from a secondary plastid of green lineage. In addition, the cyanobacterial gnd genes from phototrophic and phagotrophic species in Euglenida were robustly monophyletic with Stramenopiles, and this monophyletic clade was moderately separated from those of red algae. These data suggest that these secondary phototrophic groups might have acquired the cyanobacterial genes independently of secondary endosymbioses.

Conclusion

We propose an evolutionary scenario in which plastid-lacking Excavata acquired cyanobacterial gnd genes via eukaryote-to-eukaryote lateral gene transfer or primary endosymbiotic gene transfer early in eukaryotic evolution, and then lost either their pre-existing or cyanobacterial gene.

Background

A cyanobacterium-like ancestor gave rise via primary endosymbiosis to a distinctive endosymbiotic organelle, the plastid (primary plastid), in eukaryotic cells [1,2]. Some eukaryotic lineages retained the plastid through successive generations, and its photosynthetic ability enabled them to grow autotrophically. Some may have lost the plastid, and returned to their previous heterotrophic state, whereas others may have never experienced such an endosymbiotic event.

Green plants (green algae and land plants), Glaucophyta and red algae are primary plastid-containing photosynthetic eukaryotes. They are classified into a single super-group, Archaeplastida, among the six 'super-groups' proposed by Adl et al. [3]. It is generally believed that the majority of the cyanobacterial genes (genes sharing their origins with cyanobacterial homologues) found in the nuclear genomes of extant Archaeplastida were recruited from cyanobacterium-like endosymbionts via endosymbiotic gene transfer (EGT) [4-6].

Other algae in several independent lineages are thought to have secondarily acquired plastids by engulfing primary photosynthetic eukaryotes. These have evolved into secondary plastid-containing photosynthetic eukaryotes (secondary phototrophs) [1,2]. Most secondary plastids in the super-group Chromalveolata, which consists of Stramenopiles, Alveolata, Haptophyta and Cryptophyta, are derived from red algae. Chlorarachniophyta in the Rhizaria group and Euglenida in the Excavata group possess secondary plastids derived from green algal ancestors [7-9]. A large number of plastid-related cyanobacterial genes were further introduced into nuclear genomes of secondary phototrophs via secondary EGT [10-12].

Although several studies have reported cyanobacterial genes in plastid-lacking eukaryotes [13,14], gnd genes are remarkable in their broad distribution among primary and secondary plastid-containing photosynthetic eukaryotes as well as among plastid-lacking protists [15,16]. The gnd gene encodes an oxidative pentose phosphate pathway enzyme, 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, which is important in regulating sugar metabolism and intracellular redox state. Previous studies reported that the gnd gene is widely conserved among eukaryotes and eubacteria [17], and showed that there are two types of gnd genes; one is phylogenetically close to cyanobacterial gnd genes (termed 'cyanobacterial gnd'), and the other resembles cytosol-localized gnd genes in Opisthokonta (termed 'eukaryotic ancestral gnd'). Cyanobacterial gnd genes are present not only in primary and secondary phototrophs, but also in plastid-lacking protists. These include the plant pathogen Phytophthora that is classified into the super-group Chromalveolata, and the heterolobosean amoebo-flagellates that are classified into the super-group Excavata [15,16]. These pioneering studies suggested a possible scenario that cyanobacterial gnd genes were introduced via primary or secondary endosymbiosis [15-17]. Nevertheless, the origin and evolutionary relationships of these genes in photosynthetic and plastid-lacking eukaryotes remains inconclusive.

We present here an extended analysis of the phylogeny of gnd genes with emphasis on the plastid-lacking excavate protists. We also discuss the origin and evolutionary history of the cyanobacterial genes in plastid-lacking protists, within the scope of previously proposed hypotheses on ancient lateral gene transfer (LGT) and EGT events.

Methods

Culture material

Diplonema papillatum (ATCC No. 50162) was axenically cultured at 25°C in artificial seawater supplemented with 1% horse serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 1 × Daigo IMK medium (Nippon Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) and 0.1% tryptone. Peranema trichophorum cells, co-cultured with Chlorogonium sp., were provided by Dr. Toshinobu Suzaki (Kobe University). Euglena gracilis Z (NIES-48) was cultured as described previously [18].

cDNA Library construction and PCR-based gene isolation

D. papillatum genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). P. trichophorum full-length cDNA sequences were synthesized using the SV total RNA isolation system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and the CapFishing full-length cDNA kit (Seegene, Seoul, Korea). Glaucophyte cDNAs (Cyanophora paradoxa NIES-547, Gloeochaete wittrockiana SAG 46.84 and Cyanoptyche gloeocystis SAG 34.90) were prepared as described in the previous study [19], and used as templates for gene isolation. Fragments of gnd genes were amplified using nested-degenerated primers based on the conserved amino acid motif GLAVMGQN for forward primers (GGIYTIGCIGTIATGGGICA or YTIGCIGTIATGGGICARAA) and QAQRDFFG for reverse primers (CCRAARAARTCICKYTGIGC or AARAARTCICKYTGIGCYTG). PCR products and cDNA clones were sequenced directly or after TA-cloning, using an ABI PRISM 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with a BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit v. 3.1 (Applied Biosystems). Expressed sequence tags (ESTs) of Euglena gracilis (3,934 sequenced clones, average length 532 bp) were generated by sequencing cDNA clones selected at random from a cDNA library (average insert size, >1 kbp) constructed using a cDNA synthesis kit (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, TX, USA). The EST sequencing was performed at the Dragon Genomics Center, Takara Bio Inc. (Yokkaichi, Japan). A clone harboring the full-length gnd gene sequence was identified by BLAST search.

Phylogenetic analysis

The data matrix of gnd genes was based on the amino acid alignment in Andersson and Roger [15]. We excluded amitochondrial and/or parasitic eukaryotes, which might cause long branch attraction due to unusual nucleotide substitutions [15,20,21]. We included the novel sequences determined in this study (Table 1), and sequences identified by the BLAST program from the Galdieria sulphuraria genome database [22], the Joint Genome Institute [23] and the Acanthamoeba castellanii EST database in TBestDB [24]. The sequences were aligned using CLUSTAL X [25] and manually refined using SeaView [26]. The data matrix was made with 63 taxa and 437 amino acid sites (available upon request to SM). Data matrices excluding Heterolobosea (61 taxa, 437 sites) and including amitochondrial and/or parasitic eukaryotes (72 taxa, 437 sites) were also prepared to construct additional trees (Additional files 1 and 2, respectively).

Table 1.

Sequences encompassing the EW signature and accession numbers of gnd genes identified in this study

| Species name | Taxonomy | EW signature | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyanophora paradoxa | Glaucophyta | IDGGNEWYENTE | AB425331 |

| Gloeochaete wittrockiana | Glaucophyta | IDGGNEWYKNTE | AB425332 |

| Cyanoptyche gloeocystis | Glaucophyta | IDGGNEWYLNTE | AB425333 |

| Euglena gracilis | Euglenida | VDGGNEWFPNSQ | AB425328 |

| Peranema trichophorum | Euglenida | IDGGNEWFPNTL | AB425329 |

| Diplonema papillatum | Diplonemea | IDGGNSHFPDSI | AB425330 |

Bayesian inference was performed with the program MrBayes version 3.1.2 [27] using the WAG matrix of amino acid replacements assuming a proportion of invariant positions and four gamma-distributed rates (WAG+I+Γ4 model). For the MrBayes consensus trees, 1,000,000 generations were completed with trees collected every 100 generations. One thousand replicates of bootstrap analyses by maximum likelihood (ML) method were performed using PhyML version 2.4.4 [28] with the WAG+I+Γ4 model on two SunFire 15K machines, each of which has 96 CPUs. Bootstrap values (1,000 replicates) based on maximum parsimony (MP) analysis were calculated with PAUP 4.0 b10 with TBR heuristic search [29]. For exhaustive ML analysis, topology-dependent sitewise likelihood values were calculated using TREE-PUZZLE version 5.2 under a WAG+F+Γ8 model [30]. Alternative tree topologies were analyzed with the approximately unbiased (AU) [31] and Kishino-Hasegawa (KH) [32] tests, and the resampling estimated log-likelihood (RELL) bootstrap support values [33], using the CONSEL package [31].

Results and Discussion

Phylogenetic and statistical analysis of gnd genes

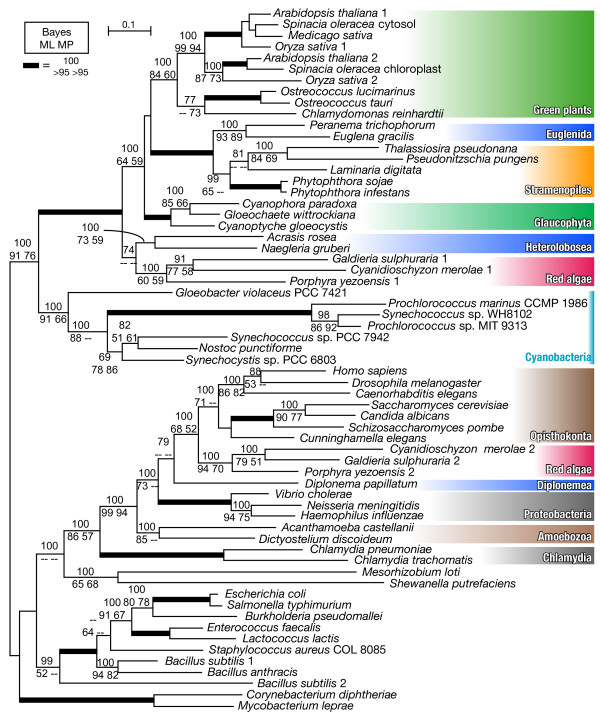

Fig. 1 shows a Bayesian consensus tree from a matrix with 63 taxa, with Bayesian posterior probabilities (Bayes) of 70% or more, and ML and MP bootstrap support values of 50% or more. As reported previously [15,16], all the red algae examined have both cyanobacterial and eukaryotic ancestral gnd genes. Although several excavate gnd genes (Heterolobosea and Euglenida) were cyanobacterial in agreement with the previous studies [15,16], the gnd gene from another excavate species, D. papillatum, was found to group with Opisthokonta and red algal eukaryotic ancestral genes (Bayes|ML|MP = 79|--|--). Several proteobacterial species (Vibrio, Neisseria and Haemophilus) showed a weak affinity to eukaryotic genes (Bayes|ML|MP = 100|73|--), and Amoebozoa was located outermost in the eukaryotic ancestral clade (Bayes|ML|MP = 100|99|94). Notably, red algae and excavate genes shared basal positions within each of the cyanobacterial and eukaryotic ancestral clades. As shown in Trypanosoma, Giardia and Trichomonas [15], the EW sequence signature, which is unique to the cyanobacterial gnd genes, was absent in the D. papillatum gnd gene (Table 1, Additional file 3), confirming its non-cyanobacterial origin. However, the parasitic excavates were positioned outside of the eukaryotic ancestral clade with weak support values in the tree of 72 taxa (Additional file 2), possibly due to long branch attraction. Whether the genes from parasitic Excavata truly shared the same origin as known free-living Excavata genes, or were independently acquired via prokaryote-to-eukaryote LGT is open to further investigation of evolutionary signals and functional characterization. Our results and currently available genome information suggest that, while each red algal species possesses both cyanobacterial and eukaryotic ancestral genes and supposedly use them in different cellular compartments, free-living Excavata examined to date have just one or the other.

Figure 1.

MrBayes consensus tree of gnd genes, constructed with 437 amino acid sites from 63 taxa. Bayesian posterior probabilities (Bayes) (70% or more) and maximum likelihood (ML) and maximum parsimony (MP) bootstrap support values (50% or more) are shown. The thick branches are represented as described in the figure.

Cyanobacterial genes from bikonts [34] (namely Archaeplastida, Stramenopiles and Excavata in this study) were robustly monophyletic (Bayes|ML|MP = 100|100|98) and showed a strong affiliation with the genes from cyanobacteria (Bayes|ML|MP = 100|91|76) (Fig. 1). In the cyanobacterial gene clade, each of the three divisions of Archaeplastida (green plants, Glaucophyta and red algae) was monophyletic but separately located (Fig. 1). Glaucophyte gnd genes formed a monophyletic group with green plants, Euglenida, and Stramenopiles with moderate support values (Bayes|ML|MP = 100|64|59). Secondary phototrophs and the plastid-lacking heterotrophic relatives from Euglenida and Stramenopiles were robustly monophyletic (Bayes|ML|MP = 100|100|100). Plastid-lacking heterolobosean protists and red algae were located at the basal position in the cyanobacterial clade, weakly forming a monophyletic group (Bayes|ML|MP = 74|-|-).

To test the possibility that the plastid-lacking excavate protists acquired gnd genes via secondary endosymbiosis of a green alga [15], we carried out an exhaustive ML analysis for calculating the likelihood values of alternative tree topologies. First, based on the topology in Fig. 1, we defined six groups in which monophyly was confirmed by all three methods (Bayes = 100, ML > 50, MP > 50): green plants (Green), Glaucophyta (Glauco), Stramenopiles + Euglenida (EuSt), Heterolobosea (Htrl), red algae (Red) and others (Outgroup). Then, we constructed all possible 105 trees, fixing the intra-group topologies of the six monophyletic groups as in Fig. 1, and calculated probabilities of each tree for AU and KH tests (Table 2, Additional file 3). All possible 15 trees supporting the monophyly of Green + Htrl were rejected by both AU and KH tests at the 5% confidence level. All possible nine trees supporting monophyly of Green + EuSt + Htrl groups were also rejected by both tests at the 5% confidence level (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of alternative tree topologies by exhaustive maximum likelihood (ML) analysis

| Treea | Topologyb | ΔlnLc | S.E. | pAUd | pKHd | RELLe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (Out, (Red, Htrl), (EuSt, (Glauco, Green))); | <-27143.41> | - | 0.867 | 0.758 | 0.283 |

| 36 | (Out, Red, ((Htrl, Green), (EuSt, Glauco))); | 30.2 | 14.4 | 0.038 | 0.020 | 5.00E-06 |

| 49 | (Out, ((Red, (Htrl, Green)), EuSt), Glauco); | 54.7 | 17.8 | 0.013 | 0.003 | 2.00E-04 |

| 54 | (Out, ((Red, (Htrl, Green)), Glauco), EuSt); | 40.1 | 19.3 | 0.011 | 0.024 | 3.00E-04 |

| 56 | (Out, Red, (((Htrl, Green), Glauco), EuSt)); | 27.8 | 15.8 | 0.009 | 0.038 | 4.00E-04 |

| 58 | (Out, ((Red, Glauco), (Htrl, Green)), EuSt); | 41.6 | 19.4 | 0.009 | 0.021 | 3.00E-06 |

| 70 | (Out, ((Red, EuSt), (Htrl, Green)), Glauco); | 52.8 | 18.2 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 3.00E-07 |

| 71 | * (Out, (Red, (Htrl, (EuSt, Green))), Glauco); | 48.9 | 15.5 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 1.00E-05 |

| 82 | * (Out, (Red, ((Htrl, Green), EuSt)), Glauco); | 57.1 | 17.8 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 3.00E-06 |

| 85 | (Out, (Red, (EuSt, Glauco)), (Htrl, Green)); | 44.1 | 15.0 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 2.00E-05 |

| 86 | (Out, (Red, ((Htrl, Green), Glauco)), EuSt); | 39.2 | 19.1 | 5.00E-04 | 0.025 | 6.00E-06 |

| 87 | * (Out, Red, (((Htrl, EuSt), Green), Glauco)); | 29.5 | 14.8 | 4.00E-04 | 0.025 | 1.00E-06 |

| 89 | (Out, ((Red, EuSt), Glauco), (Htrl, Green)); | 51.3 | 18.0 | 2.00E-04 | 0.005 | 3.00E-06 |

| 91 | * (Out, Red, ((Htrl, (EuSt, Green)), Glauco)); | 27.9 | 14.5 | 1.00E-04 | 0.028 | 1.00E-05 |

| 93 | * (Out, (Red, Glauco), (Htrl, (EuSt, Green))); | 50.0 | 16.3 | 1.00E-04 | 0.003 | 3.00E-06 |

| 94 | * (Out, (Red, ((Htrl, EuSt), Green)), Glauco); | 54.0 | 18.5 | 1.00E-04 | 0.004 | 1.00E-06 |

| 95 | (Out, (Red, EuSt), ((Htrl, Green), Glauco)); | 44.8 | 18.5 | 6.00E-05 | 0.012 | 2.00E-06 |

| 96 | (Out, (Red, (Htrl, Green)), (EuSt, Glauco)); | 41.4 | 15.0 | 3.00E-05 | 0.005 | 5.00E-07 |

| 98 | * (Out, (Red, Glauco), ((Htrl, EuSt), Green)); | 52.5 | 18.7 | 2.00E-06 | 0.006 | 7.00E-07 |

| 101 | (Out, ((Red, Glauco), EuSt), (Htrl, Green)); | 55.7 | 18.0 | 2.00E-40 | 0.003 | 2.00E-15 |

| 103 | * (Out, (Red, Glauco), ((Htrl, Green), EuSt)); | 57.0 | 18.2 | 2.00E-53 | 0.003 | 1.00E-17 |

| 104 | * (Out, Red, (((Htrl, Green), EuSt), Glauco)); | 32.8 | 15.0 | 3.00E-56 | 0.016 | 8.00E-19 |

Although our tree topology in Fig. 1 suggests that cyanobacterial genes from bikonts were originally acquired via a single gene transfer event from cyanobacteria, there are two possible explanations of their origin as discussed in the previous study [15]; early primary EGT from the ancestral plastid genome, or prokaryote-to-eukaryote LGT from a close relative of extant cyanobacteria independently of EGT. We favor the former scenario for the following reasons: 1) the gnd gene product is functionally plastid-related, and is enzymatically localized to the plastid in green plants [17]; and 2) the overall tree topology in Fig. 1 is consistent with a recent multigene phylogeny of eukaryotes based on slowly evolving nuclear genes [19].

Origins of plastid-lacking excavate gnd genes

Heterolobosean gnd genes occupied the basal positions in the cyanobacterial clade and weakly formed a monophyletic group with red algae. Although our tree topology suggests that euglenid and heterolobosean gnd genes are distantly related, previous studies have not clearly excluded the single secondary-plastid origin of these genes [15,16]. To test whether the heterolobosean gnd genes could originate with secondary EGT as suggested by the 'plastids-early' hypothesis for secondary plastids in Euglenida [8], we verified the possibility that the cyanobacterial gnd genes in plastid-lacking heterolobosean protists and green plants could be potentially monophyletic, using confidence tests based on exhaustive ML analyses (Table 2). According to the plastids-early hypothesis for secondary plastids in Euglenida [8], the secondary endosymbiosis of green alga occurred in the common ancestor of Euglenida and Heterolobosea, and extant plastid-lacking protists within these taxa have secondarily lost their plastids and photosynthesis-related genes. Although this hypothesis is contentious [1,8], it is worth verifying because this is the leading explanation for the acquisition of cyanobacterial genes through secondary endosymbionts in Heterolobosea. Considering that the orientation of LGT between the ancestors of Stramenopiles and Euglenida is unknown, we examined two possibilities on the origin of the euglenid and heterolobosean gnd genes. First, we examined the possibility that ancient euglenid gnd was transferred into the common ancestor of Stramenopiles, which postulates the monophyly of Stramenopiles, Euglenida, Heterolobosea and green plants. Then we examined the second possibility that an ancient stramenopile gnd was acquired by the euglenid ancestor, which assumes that Heterolobosea and green plants are exclusively monophyletic. All the trees supporting first or second possibilities were rejected by AU and KH tests at the 5% confidence level (Table 2). These results suggested that heterolobosean gnd genes were not secondary green plastid-derived, and that the gnd gene phylogeny did not support the plastids-early hypothesis [8,35]. Taken together, our data disallowed the plastids-early hypothesis, and showed that a secondary endosymbiotic origin of the gnd genes from green alga into plastid-lacking excavate protists is unlikely.

It is striking that Euglenida is monophyletic with Stramenopiles in the cyanobacterial clade (Fig. 1). Recent phylogenetic analyses of the plastid-encoded and nuclear-encoded plastid-targeted genes suggest that the ancestor of euglenid secondary plastids branches within green algae, inconsistent with our gnd tree topology [9,36]. The monophyly of cyanobacterial gnd genes from E. gracilis and plastid-lacking P. trichophorum further suggests that euglenid gnd genes have not been recruited via secondary EGT of a green alga, because the 'plastids-recent' hypothesis argues that eukaryovorous euglenid species such as P. trichophorum diverged before the secondary endosymbiotic event in the Euglenida lineage [8]. Meanwhile, the presence of the cyanobacterial genes in Stramenopiles, including photosynthetic algae and the plastid-lacking oomycete Phytophthora, is apparently consistent with the 'Chromalveolate hypothesis' [1,13], which suggests that secondary plastids of Chromalveolata have been acquired through a single secondary endosymbiotic event. The most likely explanation is that the ancestor of the euglenida host cells acquired a gnd gene via ancient LGT from the stramenopile lineage before their divergence. This also explains well why Euglenida and Heterolobosea are robustly separated in the gnd phylogeny (Fig. 1) despite the close relatedness of these two lineages based on SSU rRNA gene phylogeny [35] and multiple nuclear-encoded protein phylogenies [36,37].

Evolutionary history of gnd genes and plastid-lacking excavate genomes

Although our gnd tree topology appears unexpected compared with the prevailing view of plastid evolution [38], several gene phylogenies that suggested imprints of gene transfer between Euglenida and Stramenopiles have been reported. In the plastid-targeted phosphoribulokinase (PRK) gene phylogeny [39], red algal genes were basal in the eukaryotic clade and were separated from chromalveolate and green plant genes. Furthermore, euglenid and chromalveolate PRK genes were monophyletic and sister to green plants, and the authors reasoned that these secondary phototrophs might acquire PRK genes via independent LGT events. As discussed above, it is likely that Euglenida has acquired a cyanobacterial gnd gene from the ancestor of Stramenopiles via LGT. Although PRK genes are found only in photosynthetic organisms (cyanobacteria, algae and land plants) and the origin of euglenid PRK genes was phylogenetically unresolved, one can argue that PRK and cyanobacterial gnd genes might have gone through similar evolutionary histories. A phylogenetic analysis of plastid-targeted fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBP) genes illustrated another case of LGT between Euglenida and Chromalveolata [40]. Thus these genes might have been transferred from the stramenopile lineage to the euglenid lineage via multiple LGT events, perhaps phagocytosis of secondary phototrophs by a phagotrophic ancestor as suggested in the chlorarachniophyte Bigelowiella natans [41].

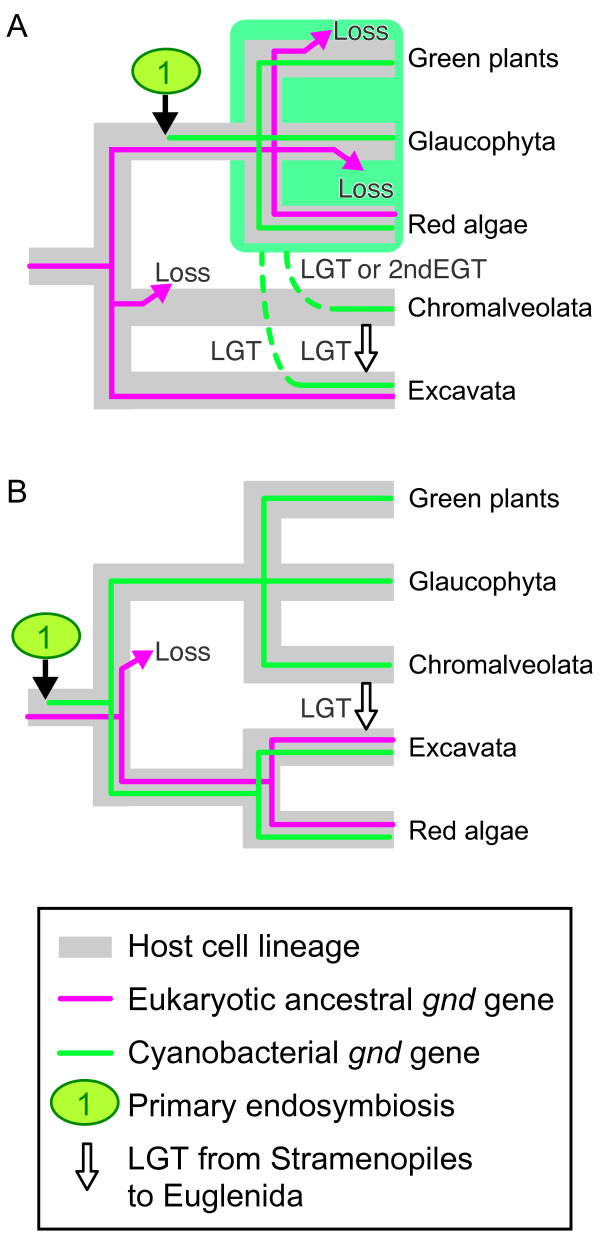

In the cyanobacterial gnd gene subtree, the red algal clade was at the basal position and was moderately separated from green plants and Glaucophyta. An additional phylogenetic analysis excluding Heterolobosea recovered the basal position of red algae in this subtree, suggesting that long branch attraction or artificial misplacement of red algae by heterolobosean sequences was unlikely (additional file 1). Additionally, provided that the cyanobacterial genes from bikonts were robustly monophyletic (Fig. 1), in contrast to well-characterized examples of prokaryote-to-eukaryote LGTs [42-44], it is unlikely that the cyanobacterial gnd genes from bikonts had been acquired via multiple LGTs from cyanobacteria to eukaryotes. Recently, two competing hypotheses on Archaeplastida phylogeny were proposed (monophyly vs. non-monophyly) [19,45]. The phylogenetic position of red algae in Fig. 1 is inconsistent with the monophyletic hypothesis of the Archaeplastida [45] unless multiple eukaryote-to-eukaryote LGTs are hypothesized (Fig. 2A). Although red algal and glaucophyte ancestries of the heterolobosean genes were not significantly dismissed, AU tests rejected the possible secondary EGT from green alga to Heterolobosea (Table 2). Hence, the eukaryote-to-eukaryote LGTs shown in Fig. 2A are likely sources of gnd genes in plastid-lacking protists, in terms of the monophyletic hypothesis of the Archaeplastida [45-47]. However, monophyly of red algae plus Stramenopiles (plus Euglenida) was not rejected in our statistical tests (Additional file 4), suggesting that the stramenopile genes might be attributed to secondary EGT of red alga. On the other hand, an increasing number of multigene phylogenies showed that monophyly of Archaeplastida had limited or no support [19,47-49]. Therefore it is advisable to discuss the evolutionary history of gnd genes, taking a different point of view on the plastid evolution into consideration (Fig. 2B). In terms of the non-monophyly hypothesis of the Archaeplastida, it is reasonable to suggest that the gnd gene phylogeny may reflect the host cell phylogeny as recently resolved by a multiple slowly evolving nuclear gene phylogeny [19], which demonstrated the non-monophyly of Archaeplastida and the most basal positioning of red algae plus Excavata within the bikonts (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Evolutionary scenarios on the cyanobacterial and eukaryotic ancestral gnd gene distribution in bikonts. A, Traditional view of host cell phylogeny of bikonts [e.g. 45], assuming the multiple loss events of eukaryotic ancestral genes and at least two lateral gene transfer events (LGT) of cyanobacterial genes (broken lines plus white arrows). B, Alternative phylogeny [e.g. 19], assuming a single loss and a single lateral gene transfer event. Although only either the cyanobacterial or eukaryotic ancestral gene was found in Excavata in this study, only one is illustrated for clarity. Rhizaria is not shown since no gnd genes have been found in this lineage. 2nd EGT, secondary endosymbiotic gene transfer.

Possible evolutionary scenarios of plastid and host nuclear genomes

We propose evolutionary scenarios in which the common ancestor of eukaryotes possessed a eubacteria-derived eukaryotic ancestral gnd gene, and the bikonts lineage additionally acquired the cyanobacterial gnd gene via a single primary endosymbiosis [50-52] (but see [53,54] for alternative views), and then diversified into Archaeplastida, Chromalveolata, Excavata (and Rhizaria) (Fig. 2). Given that recent large-scale molecular phylogenies demonstrated the monophyly of bikonts [19,45-47] based on the rooting of eukaryotes [34], and no data providing evidence on primary and secondary plastids in the unikonts has been shown, we illustrated two likely scenarios in Fig. 2. In scenario A, we assumed monophyly of Archaeplastida [e.g. [45]], and accordingly, at least two gains of cyanobacterial gnd genes via LGT and multiple losses of eukaryotic ancestral genes in separate lineages of bikonts. In scenario B, we presumed that all the bikonts including secondary phototrophs and plastid-lacking bikonts had at one time acquired the primary plastid [19]. Green plants, Glaucophyta and Chromalveolata then lost the eukaryotic ancestral gnd gene, red algae retained both, and Excavata lost either one. In the ancestors of Excavata, loss of primary photosynthetic plastids might have triggered concurrent gene loss of either cyanobacterial or eukaryotic ancestral gnd. Only a single LGT event from Stramenopiles into Euglenida is considered in scenario B. Although both scenarios are compatible with our phylogenetic analysis and statistical tests, we reason that scenario B is parsimonious and more likely to explain the evolutionary history of the gnd genes in that less LGT events need to be presupposed. Broader sampling from various eukaryotic groups (especially in Chromalveolata and Rhizaria) will be critical to devise a more reliable evolutionary history of eukaryotic gnd genes, and host lineages [49]. It is also important to note that concatenated nuclear gene phylogeny of eukaryotic (host cell) lineages and data mining for cyanobacterial genes in plastid-lacking protists are supposed to be independent approaches for exploring the origin of plants. Future research will be focused on how deeply primary endosymbiosis is rooted within the bikonts, and which lineage could experience primary endosymbiosis early in the evolution of bikonts.

Conclusion

Our present study demonstrates that (1) free-living Excavata possess either cyanobacterial or eukaryotic ancestral gnd genes, (2) it is statistically unlikely that heterolobosean gnd genes were acquired via ancient secondary EGT of green alga, and (3) Euglenida and Stramenopiles are robustly monophyletic. Although the sister relationship of this monophyletic group to any Archaeplastida lineage is not rejected by the statistical tests (Additional file 4), it is moderately separated from red algae (Fig. 1), suggesting that the gnd genes in Stramenopiles are not of secondary endosymbiont origin. One explanation is that a unique primary EGT of cyanobacterial gnd genes into Archaeplastida was followed by independent eukaryote-to-eukaryote LGTs into Stramenopiles and Heterolobosea, and then by an additional LGT from Stramenopiles into Euglenida (Fig. 2A). Alternatively, our results favor an evolutionary scenario that the gnd gene phylogeny reflects host cell phylogeny, and that the common ancestor of bikonts has acquired cyanobacterial gnd genes via primary endosymbiotic gene transfer early in eukaryotic evolution (Fig. 2B).

Authors' contributions

SM participated in the design of the study and coordination, carried out the molecular phylogenetic and statistical studies, and drafted the manuscript. KM participated in the phylogenetic and statistical studies. MI and MW participated in the cDNA library construction and sequence analysis. HN conceived of the study, and participated in its design and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Additional file 1

Figure 3. MrBayes consensus tree of gnd genes, constructed with 437 amino acid sites from 61 taxa. See text and Fig. 1 for additional notes.

Additional file 2

Figure 4. MrBayes consensus tree of gnd genes, constructed with 437 amino acid sites from 72 taxa. See text and Fig. 1 for additional notes. Accession numbers for sequences shown are as follows: Giardia lamblia, XP_001704443; Trichomonas vaginalis, XP_001298645; Leishmania major, XP_843439; Trypanosoma brucei, XP_827463;Plasmodium falciparum, XP_001348694; Babesia bovis, XP_001610335; Theileria annulata, XP_954525; and Theileria parva, XP_765720. Gene ID to Toxoplasma gondii gene is 49.m00043 at ToxoDB [55].

Additional file 3

Figure 5. A region of the amino acid sequence alignment encompassing the EW signature of gnd genes. See text, Table 1 and Fig. 4 for additional notes.

Additional file 4

Table 3. Comparison of alternative tree topologies by exhaustive maximum likelihood (ML) analysis. All possible 105 trees are shown. See text and Table 2 for additional notes.

Contributor Information

Shinichiro Maruyama, Email: maruyama@biol.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Kazuharu Misawa, Email: kazumisawa@riken.jp.

Mineo Iseki, Email: iseki_mineo@soken.ac.jp.

Masakatsu Watanabe, Email: watanabe_masakatsu@soken.ac.jp.

Hisayoshi Nozaki, Email: nozaki@biol.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Toshinobu Suzaki (Kobe University) for a generous gift of the P. trichophorum culture, and Dr. Takashi Nakada (Keio University) for help with phylogenetic analysis. Computation time was provided by the Super Computer System, Human Genome Center, Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Creative Scientific Research (No. 16GS0304 to HN) and for Scientific Research (No. 17370087 to HN) from The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan.

References

- Cavalier-Smith T. Principles of Protein and Lipid Targeting in Secondary Symbiogenesis: Euglenoid, Dinoflagellate, and Sporozoan Plastid Origins and the Eukaryote Family Tree. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1999;46:347–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1999.tb04614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Prieto A, Weber AP, Bhattacharya D. The Origin and Establishment of the Plastid in Algae and Plants. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:147–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adl SM, Simpson AG, Farmer MA, Andersen RA, Anderson OR, Barta JR, Bowser SS, Brugerolle G, Fensome RA, Fredericq S, James TY, Karpov S, Kugrens P, Krug J, Lane CE, Lewis LA, Lodge J, Lynn DH, Mann DG, McCourt RM, Mendoza L, Moestrup O, Mozley-Standridge SE, Nerad TA, Shearer CA, Smirnov AV, Spiegel FW, Taylor MF. The new higher level classification of eukaryotes with emphasis on the taxonomy of protists. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2005;52:399–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W, Rujan T, Richly E, Hansen A, Cornelsen S, Lins T, Leister D, Stoebe B, Hasegawa M, Penny D. Evolutionary analysis of Arabidopsis, cyanobacterial, and chloroplast genomes reveals plastid phylogeny and thousands of cyanobacterial genes in the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12246–12251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182432999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Prieto A, Hackett JD, Soares MB, Bonaldo MF, Bhattacharya D. Cyanobacterial contribution to algal nuclear genomes is primarily limited to plastid functions. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2320–2325. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato N, Ishikawa M, Fujiwara M, Sonoike K. Mass identification of chloroplast proteins of endosymbiont origin by phylogenetic profiling based on organism-optimized homologous protein groups. Genome inform. 2005;16:56–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodyl A. Do plastid-related characters support the chromalveolate hypothesis? J Phycol. 2005;41:712–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00091.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leander BS. Did trypanosomatid parasites have photosynthetic ancestors? Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers MB, Gilson PR, Su V, McFadden GI, Keeling PJ. The complete chloroplast genome of the chlorarachniophyte Bigelowiella natans : evidence for independent origins of chlorarachniophyte and euglenid secondary endosymbionts. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:54–62. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbrust EV, Berges JA, Bowler C, Green BR, Martinez D, Putnam NH, Zhou S, Allen AE, Apt KE, Bechner M, Brzezinski MA, Chaal BK, Chiovitti A, Davis AK, Demarest MS, Detter JC, Glavina T, Goodstein D, Hadi MZ, Hellsten U, Hildebrand M, Jenkins BD, Jurka J, Kapitonov VV, Kröger N, Lau WW, Lane TW, Larimer FW, Lippmeier JC, Lucas S, Medina M, Montsant A, Obornik M, Parker MS, Palenik B, Pazour GJ, Richardson PM, Rynearson TA, Saito MA, Schwartz DC, Thamatrakoln K, Valentin K, Vardi A, Wilkerson FP, Rokhsar DS. The genome of the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana : ecology, evolution, and metabolism. Science. 2004;306:79–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1101156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas S, Zauner S, Fraunholz M, Beaton M, Penny S, Deng LT, Wu X, Reith M, Cavalier-Smith T, Maier UG. The highly reduced genome of an enslaved algal nucleus. Nature. 2001;410:1091–1096. doi: 10.1038/35074092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson PR, Su V, Slamovits CH, Reith ME, Keeling PJ, McFadden GI. Complete nucleotide sequence of the chlorarachniophyte nucleomorph: nature's smallest nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9566–9571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600707103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler BM, Tripathy S, Zhang X, Dehal P, Jiang RH, Aerts A, Arredondo FD, Baxter L, Bensasson D, Beynon JL, Chapman J, Damasceno CM, Dorrance AE, Dou D, Dickerman AW, Dubchak IL, Garbelotto M, Gijzen M, Gordon SG, Govers F, Grunwald NJ, Huang W, Ivors KL, Jones RW, Kamoun S, Krampis K, Lamour KH, Lee MK, McDonald WH, Medina M, Meijer HJ, Nordberg EK, Maclean DJ, Ospina-Giraldo MD, Morris PF, Phuntumart V, Putnam NH, Rash S, Rose JK, Sakihama Y, Salamov AA, Savidor A, Scheuring CF, Smith BM, Sobral BW, Terry A, Torto-Alalibo TA, Win J, Xu Z, Zhang H, Grigoriev IV, Rokhsar DS, Boore JL. Phytophthora genome sequences uncover evolutionary origins and mechanisms of pathogenesis. Science. 2006;313:1261–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.1128796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henze K, Horner DS, Suguri S, Moore DV, Sánchez LB, Müller M, Embley TM. Unique phylogenetic relationships of glucokinase and glucosephosphate isomerase of the amitochondriate eukaryotes Giardia intestinalis, Spironucleus barkhanus and Trichomonas vaginalis. Gene. 2001;281:123–131. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00773-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson JO, Roger AJ. A cyanobacterial gene in nonphotosynthetic protists – an early chloroplast acquisition in eukaryotes? Curr Biol. 2002;12:115–119. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00649-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki H, Matsuzaki M, Misumi O, Kuroiwa H, Hasegawa M, Higashiyama T, Shin-I T, Kohara Y, Ogasawara N, Kuroiwa T. Cyanobacterial genes transmitted to the nucleus before divergence of red algae in the Chromista. J Mol Evol. 2004;59:103–113. doi: 10.1007/s00239-003-2611-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krepinsky K, Plaumann M, Martin W, Schnarrenberger C. Purification and cloning of chloroplast 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase from spinach. Cyanobacterial genes for chloroplast and cytosolic isoenzymes encoded in eukaryotic chromosomes. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:2678–2686. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga S, Hori T, Takahashi T, Kubota M, Watanabe M, Okamoto K, Masuda K, Sugai M. Discovery of signaling effect of UV-B/C light in the extended UV-A/blue-type action spectra for step-down and step-up photophobic responses in the unicellular flagellate alga Euglena gracilis. Protoplasma. 1998;201:45–52. doi: 10.1007/BF01280710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki H, Iseki M, Hasegawa M, Misawa K, Nakada T, Sasaki N, Watanabe M. Phylogeny of primary photosynthetic eukaryotes as deduced from slowly evolving nuclear genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1592–1595. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiller JW, Duffield EC, Hall BD. Amitochondriate amoebae and the evolution of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11769–11774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiller JW, Riley J, Hall BD. Are red algae plants? A critical evaluation of three key molecular data sets. J Mol Evol. 2001;52:527–539. doi: 10.1007/s002390010183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Galdieria sulphuraria genome database. http://genomics.msu.edu/galdieria/index.html

- The Joint Genome Institute. http://www.jgi.doe.gov/

- The taxonomically broad EST database TBestDB. http://tbestdb.bcm.umontreal.ca/

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtier N, Gouy M, Gautier C. SEAVIEW and PHYLO_WIN: two graphic tools for sequence alignment and molecular phylogeny. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:543–548. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.6.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. PAUP* Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony, Version 4.0b10. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt HA, Strimmer K, Vingron M, von Haeseler A. TREE-PUZZLE: maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis using quartets and parallel computing. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:502–504. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimodaira H, Hasegawa M. CONSEL: for assessing the confidence of phylogenetic tree selection. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1246–1247. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishino H, Hasegawa M. Evaluation of the maximum likelihood estimate of the evolutionary tree topologies from DNA sequence data, and the branching order in hominoidea. J Mol Evol. 1989;29:170–179. doi: 10.1007/BF02100115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishino H, Miyata T, Hasegawa M. Maximum likelihood inference of protein phylogeny and the origin of chloroplasts. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1990;31:151–160. doi: 10.1007/BF02109483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stechmann A, Cavalier-Smith T. Rooting the eukaryote tree by using a derived gene fusion. Science. 2002;297:89–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1071196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith T. The excavate protozoan phyla Metamonada Grassé emend. (Anaeromonadea, Parabasalia, Carpediemonas, Eopharyngia) and Loukozoa emend. (Jakobea, Malawimonas): their evolutionary affinities and new higher taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53:1741–1758. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02548-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldauf SL. The deep roots of eukaryotes. Science. 2003;300:1703–1706. doi: 10.1126/science.1085544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson AG, Inagaki Y, Roger AJ. Comprehensive multigene phylogenies of excavate protists reveal the evolutionary positions of "primitive" eukaryotes. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:615–625. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Prieto A, Bhattacharya D. Phylogeny of Nuclear-Encoded Plastid-Targeted Proteins Supports an Early Divergence of Glaucophytes within Plantae. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:2358–2361. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen J, Teich R, Brinkmann H, Cerff R. A "green" phosphoribulokinase in complex algae with red plastids: evidence for a single secondary endosymbiosis leading to haptophytes, cryptophytes, heterokonts, and dinoflagellates. J Mol Evol. 2006;62:143–157. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0305-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teich R, Zauner S, Baurain D, Brinkmann H, Petersen J. Origin and distribution of Calvin cycle fructose and sedoheptulose bisphosphatases in plantae and complex algae: a single secondary origin of complex red plastids and subsequent propagation via tertiary endosymbioses. Protist. 2007;158:263–276. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archibald JM, Rogers MB, Toop M, Ishida K, Keeling PJ. Lateral gene transfer and the evolution of plastid-targeted proteins in the secondary plastid-containing alga Bigelowiella natans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7678–7683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1230951100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller RF, Slamovits CH, Keeling PJ. Lateral gene transfer of a multigene region from cyanobacteria to dinoflagellates resulting in a novel plastid-targeted fusion protein. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:1437–1443. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin B, Nowack EC, Glöckner G, Melkonian M. The ancestor of the Paulinella chromatophore obtained a carboxysomal operon by horizontal gene transfer from a Nitrococcus-like γ-proteobacterium. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosenko T, Bhattacharya D. Horizontal gene transfer in chromalveolates. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:173. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Ezpeleta N, Brinkmann H, Burger G, Roger AJ, Gray MW, Philippe H, Lang BF. Toward resolving the eukaryotic tree: the phylogenetic positions of jakobids and cercozoans. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1420–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett JD, Yoon HS, Li S, Reyes-Prieto A, Rümmele SE, Bhattacharya D. Phylogenomic analysis supports the monophyly of cryptophytes and haptophytes and the association of rhizaria with chromalveolates. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1702–1713. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patron NJ, Inagaki Y, Keeling PJ. Multiple gene phylogenies support the monophyly of cryptomonad and haptophyte host lineages. Curr Biol. 2007;17:887–891. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burki F, Shalchian-Tabrizi K, Minge M, Skjaeveland A, Nikolaev SI, Jakobsen KS, Pawlowski J. Phylogenomics reshuffles the eukaryotic supergroups. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon HS, Grant J, Tekle YI, Wu M, Chaon BC, Cole JC, Logsdon JM, Patterson DJ, Bhattacharya D, Katz LA. Broadly sampled multigene trees of eukaryotes. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki M, Misumi O, Shin-I T, Maruyama S, Takahara M, Miyagishima SY, Mori T, Nishida K, Yagisawa F, Nishida K, Yoshida Y, Nishimura Y, Nakao S, Kobayashi T, Momoyama Y, Higashiyama T, Minoda A, Sano M, Nomoto H, Oishi K, Hayashi H, Ohta F, Nishizaka S, Haga S, Miura S, Morishita T, Kabeya Y, Terasawa K, Suzuki Y, Ishii Y, Asakawa S, Takano H, Ohta N, Kuroiwa H, Tanaka K, Shimizu N, Sugano S, Sato N, Nozaki H, Ogasawara N, Kohara Y, Kuroiwa T. Genome sequence of the ultrasmall unicellular red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae 10D. Nature. 2004;428:653–657. doi: 10.1038/nature02398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber AP, Linka M, Bhattacharya D. Single, ancient origin of a plastid metabolite translocator family in Plantae from an endomembrane-derived ancestor. Eukaryotic Cell. 2006;5:609–612. doi: 10.1128/EC.5.3.609-612.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Prieto A, Bhattacharya D. Phylogeny of Calvin cycle enzymes supports Plantae monophyly. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2007;45:384–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkum AW, Lockhart PJ, Howe CJ. Shopping for plastids. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiller JW. Plastid endosymbiosis, genome evolution and the origin of green plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Toxoplasma gondii Genome resource ToxoDB. http://toxodb.org/toxo/home.jsp

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1

Figure 3. MrBayes consensus tree of gnd genes, constructed with 437 amino acid sites from 61 taxa. See text and Fig. 1 for additional notes.

Additional file 2

Figure 4. MrBayes consensus tree of gnd genes, constructed with 437 amino acid sites from 72 taxa. See text and Fig. 1 for additional notes. Accession numbers for sequences shown are as follows: Giardia lamblia, XP_001704443; Trichomonas vaginalis, XP_001298645; Leishmania major, XP_843439; Trypanosoma brucei, XP_827463;Plasmodium falciparum, XP_001348694; Babesia bovis, XP_001610335; Theileria annulata, XP_954525; and Theileria parva, XP_765720. Gene ID to Toxoplasma gondii gene is 49.m00043 at ToxoDB [55].

Additional file 3

Figure 5. A region of the amino acid sequence alignment encompassing the EW signature of gnd genes. See text, Table 1 and Fig. 4 for additional notes.

Additional file 4

Table 3. Comparison of alternative tree topologies by exhaustive maximum likelihood (ML) analysis. All possible 105 trees are shown. See text and Table 2 for additional notes.