Comparative Genomics Reveal Extensive Transposon-Mediated Genomic Plasticity and Diversity among Potential Effector Proteins within the Genus Coxiella (original) (raw)

Abstract

Genetically distinct isolates of Coxiella burnetii, the cause of human Q fever, display different phenotypes with respect to in vitro infectivity/cytopathology and pathogenicity for laboratory animals. Moreover, correlations between C. burnetii genomic groups and human disease presentation (acute versus chronic) have been described, suggesting that isolates have distinct virulence characteristics. To provide a more-complete understanding of C. burnetii's genetic diversity, evolution, and pathogenic potential, we deciphered the whole-genome sequences of the K (Q154) and G (Q212) human chronic endocarditis isolates and the naturally attenuated Dugway (5J108-111) rodent isolate. Cross-genome comparisons that included the previously sequenced Nine Mile (NM) reference isolate (RSA493) revealed both novel gene content and disparate collections of pseudogenes that may contribute to isolate virulence and other phenotypes. While C. burnetii genomes are highly syntenous, recombination between abundant insertion sequence (IS) elements has resulted in genome plasticity manifested as chromosomal rearrangement of syntenic blocks and DNA insertions/deletions. The numerous IS elements, genomic rearrangements, and pseudogenes of C. burnetii isolates are consistent with genome structures of other bacterial pathogens that have recently emerged from nonpathogens with expanded niches. The observation that the attenuated Dugway isolate has the largest genome with the fewest pseudogenes and IS elements suggests that this isolate's lineage is at an earlier stage of pathoadaptation than the NM, K, and G lineages.

Q fever is a wide-ranging zoonotic disease caused by the gram-negative obligate intracellular bacterium Coxiella burnetii. Acute Q fever typically arises from inhalation of aerosolized bacteria and has protean manifestations, such as periorbital headache, fever, and malaise. Rare but potentially severe chronic disease can occur that commonly manifests as endocarditis. Cattle, sheep, and goats are the primary reservoirs of C. burnetii, but isolates have been obtained from a large variety of wild vertebrates and arthropods. In most animals, C. burnetii does not cause overt disease. Exceptions are sheep and goats, where massive proliferation of the organism in the female reproductive system can result in late-term abortion. Parturition by infected mammals can consequently deposit tremendous numbers of C. burnetii into the environment (reviewed in reference 66).

The intracellular replication compartment of C. burnetii, the parasitophorous vacuole (PV), is a niche unique among intracellular bacteria in having features of a mature phagolysosome (108). The moderately acidic pH (∼5.0) of the PV is required to trigger C. burnetii metabolism, a behavior that constitutes a “biochemical stratagem” by promoting intracellular replication and extracellular stability (44). The metabolically quiescent C. burnetii small-cell variant (SCV) developmental form has spore-like resistance and appears specifically adapted for extracellular survival (24). Conversely, the more-fragile large-cell variant developmental form is metabolically and replicatively active (24). C. burnetii's pronounced extracellular stability and aerosol infectious dose of less than 10 organisms (10) has resulted in its classification as a class III biohazard and a U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention category B select agent with potential for illegitimate use.

C. burnetii was historically classified as a member of the Rickettsiaceae family. However, it is now clear that the organism is a member of the Gammaproteobacteria group of eubacteria, with a close relationship to the human pathogen Legionella pneumophila (92). Multiple studies have revealed genetic diversity among C. burnetii isolates derived from a variety of geographical areas (6, 9, 37, 55, 65). A clear biochemical manifestation of this diversity is the production of at least three antigenically and structurally unique lipopolysaccharide (LPS) molecules (43). Full-length LPS is the only defined virulence factor of C. burnetii and is synthesized by virulent phase I organisms acquired from natural sources (72). Phase I C. burnetii bacteria gradually convert to avirulent phase II organisms upon serial passage in embryonated eggs or tissue culture. Phase II C. burnetii bacteria produce a severely truncated LPS lacking _O_-antigen and several core sugars that appears to represent a minimal LPS structure (1, 105). The genetic lesion(s) that accounts for the deep, rough chemotype of phase II C. burnetii is unknown.

All C. burnetii isolates carry a moderately sized (∼37 to 55 kb) autonomously replicating plasmid or have plasmid-like sequences integrated into their chromosome (65, 77, 106). The absolute conservation of chromosomally integrated or autonomously replicating plasmid sequences among all isolates suggests that they are essential for the pathogen's survival. Because of a correlation between plasmid type and disease presentation (human acute or chronic), Samuel et al. (93) first proposed that C. burnetii isolates have distinct pathogenetic potential, an hypothesis later buttressed by a restriction fragment length polymorphism study of 32 isolates that showed disease associations between six defined genomic groups (I to VI) (51). More recently, three studies using PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism examination of the isocitrate dehydrogenase gene (76), multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis (104), and multispacer sequence typing (37) have again revealed relationships between C. burnetii's genome composition and disease outcome. However, it is also clear that existing host conditions, such as heart valve abnormalities in the context of cytokine-mediated immunosuppression, are critical cofactors in the evolution of chronic endocarditis (49, 87).

While debate continues on the contributions of host and microbe to C. burnetii pathogenesis, both in vitro and in vivo model systems indicate that prototype C. burnetii chronic disease isolates have distinct phenotypes relative to that of the reference Nine Mile (NM) isolate. (Although NM was originally isolated from a tick [28], infection by this isolate was later associated with a laboratory-acquired case of human acute Q fever [31]; therefore, NM is considered biologically representative of a human acute disease isolate.) For example, the F (Q228) endocarditis isolate inefficiently infects mouse L-929 fibroblasts, forms several vacuoles instead of one, and cannot maintain a persistent infection once host cells are transferred from static to suspension culture (90). Moreover, the G (Q212) endocarditis isolate disseminates less and causes less inflammatory damage than the NM isolate following aerosol challenge of BALB/c mice (99). Finally, some isolates derived from infected animals, such as Priscilla (Q177), a goat abortion isolate, and Dugway (5J108-111), a rodent isolate, are attenuated in virulence for guinea pigs (72, 102). Thus, diversity in pathogenic potential extends to environmental isolates.

Information is lacking on the genome composition of C. burnetii bacteria isolated from human chronic Q fever patients. Therefore, to provide a more-complete understanding of C. burnetii's genome content, architecture, and pathogenic potential, we sequenced the genomes of the prototype group IV and V human endocarditis isolates, K (Q154) and G (Q212). Sequencing of the attenuated Dugway (5J108-111) rodent isolate was also conducted and a four-genome comparison performed that included the genome of previously sequenced NM. Our results suggest that mobile genetic elements are a major influence on C. burnetii's genome evolution and function. While isolates contain novel genes, they also harbor disparate collections of virulence-associated pseudogenes that likely contribute to pathogenicity and other phenotypes. We suggest that C. burnetii isolates are at different stages of pathoadaptation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. burnetii isolates, cultivation, and purification.

The C. burnetii isolates used in this study are part of the culture collections maintained at the Rocky Mountain Laboratories, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Hamilton, MT, and Texas A&M Health Science Center, College Station, TX. The NM reference isolate (RSA493) has been previously described (96). The K (Q154) isolate was obtained in Oregon in 1976 from the aortic valve of a human endocarditis patient (43, 93). The G isolate (Q212) was acquired in Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1982 from the aortic valve of a human endocarditis patient (43, 93). The Dugway 5J108-111 isolate was recovered from a rodent in Dugway, UT, in 1957 (101). All isolates had been passaged five times or less in embryonated eggs and/or tissue culture cells and were considered to be in the phase I serological form (72).

C. burnetii was propagated in African green monkey kidney (Vero) fibroblasts (CCL-81; American Type Culture Collection) grown in RPMI medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum or in embryonated hen's eggs, as previously described (23, 93). Organisms were released from infected Vero cells by sonication and purified by Renografin density gradient centrifugation (23). Organisms were released from infected yolk sacs by tissue homogenization and purified by sucrose density gradient centrifugation (93).

Genomic DNA purification.

Total genomic DNA was isolated directly from purified C. burnetii by using an UltraClean microbial DNA isolation kit (MoBio Laboratories, Inc., Carlsbad, CA). An additional heating step (85°C for 30 min) was added before physical disruption of the bacterial cells. All DNA was resuspended in distilled H2O and frozen at −20°C.

Genome sequencing and analysis.

G and K genome sequencing and analysis, open reading frame (ORF) calling, and origin of replication identification were conducted essentially as described by Greenberg et al. (38). The Dugway 5J108-111 isolate genome was sequenced by the J. Craig Ventor Institute Microbial Sequencing Center using previously published methods (96). This genome, and the previously sequenced NM genome (96), were subjected to gene prediction and annotation procedures as described above for the G and K isolates to provide continuity in bioinformatic analyses. Alignment of the G, K, and Dugway genomes with the NM genome was performed by using Mauve 2.1.0 Muscle 3.6 aligner software with a seed weight of 15 and minimum locally colinear block (LCB) weight of 6,661 (27).

Four-way isolate genome comparisons were conducted by using the ERGO (81) protein similarity clustering tool (default e value of greater than −05 threshold cutoff) to identify unique and shared ORFs. As an additional evaluation/verification step, unique ORFs from the unique protein clusters generated were blasted against the other cognate genome in the specific comparison concerned. Unique and shared protein clusters were rebalanced to accommodate any ORFs having protein similarity hits better than e greater than −05, such that the unique families represent bona fide unique protein clusters in the specific comparison.

Pseudogenes were classified according to the criteria of Lerat and Ochman (62), where frameshifts caused by small indels or truncation caused by insertion/deletion or nonsense mutations diminished protein length by more than 20%. Frameshift validation at the raw chromatogram data level was conducted for 30 ORFs in each isolate, including all ankyrin repeat protein-encoding genes, by examining the base quality at and surrounding the junction region between two contiguous ORFs involved in a potential frameshift for errors in sequence. No errors were detected.

Proteins containing eucaryotic-like domains were identified by using the Pfam, Prosite, and PSI-BLAST databases with links provided by the ERGO bioinformatics suite. The SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) and InterPro (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) databases, along with the COILS server (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/COILS_form.html), were also used with default parameters for computational screens.

SNP identification protocol.

To identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), all ORFs, RNAs, and intergenic regions from C. burnetii isolates were clustered into their respective groups. The DNA types were further filtered using a similarity cutoff of 80% of bases between two genomes of the same type. If features differed by less than 10% in overall length, they were considered clustered and were used for calculation of SNPs. Features that differed by more than 10% were analyzed manually. All clusters of each feature type were aligned by using ClustalW, and SNPs were assigned where the aligned sequences had a change in a nucleotide at a specific location in the alignment.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis was conducted by using predicted protein sequences of NM, K, G, and Dugway. Also included in this analysis were C. burnetii strains Priscilla Q177 (partial genome sequence) and Henzerling RSA331 (recently completed genome sequence), Rickettsiella grylli, and Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia 1, whose predicted protein sequences were taken from NCBI. Proteins were clustered by applying OrthoMCL (63) to all-versus-all BLAST data, yielding 2,338 _C. burnetii_-containing families. Among these families, 1,402 contained one and only one representative from each C. burnetii isolate and were retained for further phylogenetic analysis. Each family was made representative for the outgroup isolates by excluding isolates with more than one member in the family, leaving R. grylli represented in 710 families and L. pneumophila in 868. The protein sequences of each family were aligned by using Muscle (32), and ambiguous portions of the alignment were removed by using Gblocks (17). The concatenation of these alignments contained 425,592 amino acid characters, of which only 3,510 were C. burnetii informative (for which at least two C. burnetii isolates differed from the others, or one isolate differed from the others and an outgroup was present). Three single-chain MrBayes (91) runs were primed with a random tree and maintained for 200,000 generations. All reached a likelihood plateau by 50,000 generations, and the trees from the final 150,000 generations in each of the three runs were combined to prepare a consensus tree.

Two additional tests of this tree topology were applied, speeded by removing the _C. burnetii_-noninformative characters from the matrix. One hundred bootstrap resamplings were generated and evaluated by using the maximum-likelihood program PhyML (42), fixing the proportion of invariant sites at 0.58, and the substitution matrix Cprev that the above-described MrBayes runs had determined for the large data set. One hundred jackknife resamplings (with random removal of half the characters) were taken and evaluated by single-chain MrBayes runs as described above, again with all runs reaching a likelihood plateau by 50,000 generations. Consensus trees were taken for both of these tests.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database project accession numbers for the C. burnetii genomes sequenced in this study are as follows: K, CP001020 (chromosome) and CP001021 (plasmid); G, CP001019; and Dugway, CP000733 (chromosome) and CP000735 (plasmid). The newly annotated NM genome sequence has the GenBank accession numbers AE016828 (chromosome) and AE016829 (plasmid).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chromosome and plasmid nucleotide features.

To gain insight into C. burnetii genetic diversity and pathogenetic potential, the genome sequences of the K, G, and Dugway isolates were determined and compared to the sequenced genome of NM. Chromosomal and plasmid features of the isolates are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Each isolate contains a roughly 2-Mb single circular chromosome. Relative to NM, the genomes of K, G, and Dugway have 13, 5, and 17 novel chromosomal insertions encompassing 51,414, 45,378, and 175,046 bp of DNA, respectively (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Dugway has 10 unique insertions totaling 120,747 bp, while K and G do not contain unique DNA.

TABLE 1.

Chromosomal features of C. burnetii isolates

| Statistic | C. burnetii isolate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM | K | G | Dugway | |

| Size of chromosome (bp) | 1,995,281 | 2,063,100 | 2,008,870 | 2,158,758 |

| Coding region (%) | 90.7 | 90.3 | 89.7 | 90.7 |

| G+C content (%) | 42.7 | 42.7 | 42.6 | 42.4 |

| No. of ORFs | ||||

| Total (including ORFs comprising pseudogenes) | 2,227 | 2,325 | 2,300 | 2,265 |

| With assigned function | 1,348 | 1,441 | 1,403 | 1,391 |

| Without assigned function | 879 | 884 | 897 | 874 |

| In asserted pathways | 946 | 1,014 | 1,017 | 942 |

| Not in asserted pathways | 1,281 | 1,311 | 1,283 | 1,323 |

| With assigned function but no pathway | 410 | 428 | 387 | 450 |

| Full-length | 1,814 | 1,849 | 1,816 | 1,999 |

| Comprising pseudogenes (total pseudogenes) | 413 (197) | 476 (244) | 484 (224) | 265 (136) |

| Encoding transposases (pseudogenes) | 31 (1) | 59 (27) | 40 (7) | 32 (20) |

TABLE 2.

Features of C. burnetii plasmids

| Statistic | Plasmid | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| QpH1 | QpRS | QpDG | |

| Size of plasmid (bp) | 37,393 | 39,280 | 54,179 |

| Coding region (%) | 81.0 | 79.6 | 84.9 |

| G+C content (%) | 39.3 | 39.7 | 39.8 |

| No. of ORFs | |||

| Total (including ORFs comprising pseudogenes) | 50 | 48 | 66 |

| With assigned function | 19 | 20 | 26 |

| Without assigned function | 32 | 28 | 40 |

| In asserted pathways | 4 | 6 | 8 |

| Not in asserted pathways | 46 | 42 | 58 |

| With assigned function but no pathway | 14 | 14 | 18 |

| Full-length | 35 | 38 | 53 |

| Comprising pseudogenes (total pseudogenes) | 15 (10) | 10 (6) | 13 (7) |

| Encoding transposases | 0 | 0 | 1 |

NM, K, and Dugway carry a moderately sized plasmid, while G has plasmid-like sequences integrated into its chromosome. The nucleotide sequence of the QpRS plasmid of K (39,280 bp) has 17 polymorphisms affecting eight ORFs (four ORFs being frameshifted) relative to the previously sequenced QpRS plasmid of the Priscilla (Q177) isolate, another genomic group IV isolate (60) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The Dugway plasmid, termed QpDG (65), is 54,179 bp. The larger size of QpDG relative to other C. burnetii plasmids is consistent with a previous description (65) and contrasts with a report claiming that QpDG is nearly identical to the NM plasmid QpH1 (37,393 bp) (54). The G isolate has 17,532 bp of QpRS-like plasmid sequence integrated into its chromosome between two ORFs (CbuG0070 and CbuG0090) encoding hypothetical proteins (8). This sequence has three SNPs relative to the previously sequenced integrated plasmid-like sequences of the S (Q217) isolate of genomic group V (111) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). At the nucleotide level, QpH1, QpRS, QpDG, and the integrated plasmid sequences of G are 99% identical within 14,218 bp of common DNA, while QpH1, QpRS, and QpDG are 99% identical within 28,421 bp of common DNA. QpH1, QpRS, and QpDG harbor 3,685, 2,677, and 15,423 bp, respectively, of unique sequence (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). At the nucleotide level, QpRS and QpDG are most similar in sharing 34,940 bp of common sequence.

Conserved and novel gene content.

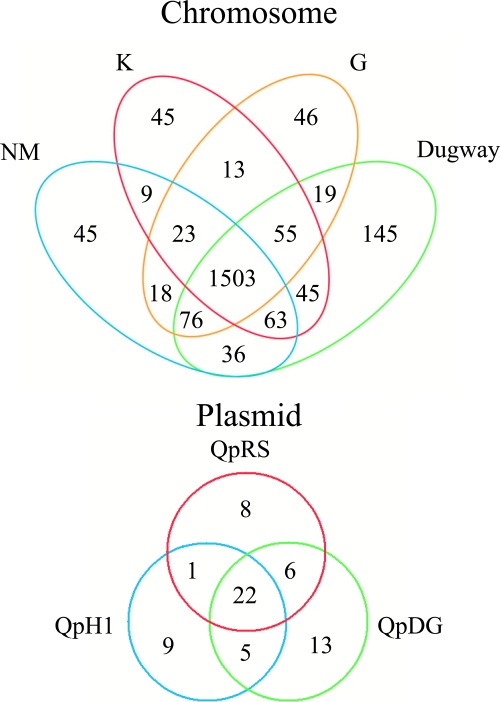

To obtain consistency in genomic comparisons, the previously sequenced NM genome (96) was subjected to gene prediction and annotation procedures as described for the K, G, and Dugway isolates (see Materials and Methods). Including pseudogenes, but not insertion sequence (IS) element-associated genes, reannotation of the NM chromosome and plasmid (QpH1) resulted in the identification of 111 and 1 previously uncalled ORF(s), respectively (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). Dugway, with the largest chromosome and plasmid, encodes the most full-length ORFs (2,052), with 145 and 13 unique ORFs encoded by the chromosome and plasmid, respectively. G, with the smallest chromosome and lacking an autonomously replicating plasmid, encodes the fewest full-length ORFs (1,816). G encodes only 31 novel intact ORFs relative to the other C. burnetii isolates, consistent with its lack of novel DNA (Fig. 1 and Tables 1 and 2; see Tables S1 and S5 in the supplemental material). A detailed comparison of the four genomes revealed 1,503 chromosomal and 22 plasmid ORFs shared by C. burnetii isolates (Fig. 1; see Fig. S1 and Table S5 in the supplemental material). The lack of extensive novel gene content between isolates is in agreement with the organism's obligate intracellular lifestyle that limits opportunities for genetic exchange. C. burnetii lacks obvious bacteriophage, although there are some phage-like genes carried by the plasmids (96). Moreover, all C. burnetii isolates contain pseudogenes associated with natural competence (e.g., comA) and lack genes encoding a conjugal apparatus. Intact chromosomal ORFs with functional annotation that are missing in NM but intact in K, G, and/or Dugway are listed in Table S6 in the supplemental material. Intact conserved and unique ORFs encoded by plasmid and plasmid-like sequences of C. burnetii isolates are listed in Table S7 in the supplemental material. Isolate-specific genes and pseudogenes with functional annotations related to metabolism and virulence are discussed in more detail below.

FIG. 1.

Venn diagram of common and unique full-length ORFs of C. burnetii isolates. The diagram shows the number of full-length ORFs that are unique or shared between one or more C. burnetii isolates or plasmids. Included among the 46 chromosomal ORFs unique to G are 15 ORFs contained in the 17,532 bp of integrated plasmid-like sequences. Thirteen of these ORFs are found in one or more C. burnetii plasmids. Pseudogenes, transposases, and transposase-associated genes were not included in this analysis.

As originally described for NM (96), C. burnetii isolates cumulatively encode an unusually high proportion (39.2%) of hypothetical and conserved hypothetical proteins (i.e., without assigned function), most of which are conserved among the four isolates (Tables 1 and 2; see Table S5 in the supplemental material). Isolates encode one copy each of 5S, 16S, and 23S rRNA genes, with the latter containing two self-splicing group I introns (86).

In a recent study using comparative genomic hybridization, Beare et al. (9) identified genetic polymorphisms of the Dugway isolates 7E9-12 and 5G61-63 relative to NM. These Dugway isolates were recovered in the same field study as the Dugway 5J108-111 isolate sequenced for this report (102). The nucleotide sequence of Dugway 5J108-111 revealed the same plasmid and chromosomal polymorphisms as 7E9-12 (e.g., deletion of NM Cbu0881), suggesting that these isolates are genetically very similar and unlike the Dugway 5G61-63 isolate, which has no polymorphisms relative to NM (9).

C. burnetii genome architecture and gene content.

Although once considered rare in obligate intracellular bacterial pathogens, IS elements have now been described in at least four species of Rickettsia (12), with large numbers present in Orientia tsutsugamushi (19). Combined, the four C. burnetii isolates harbor eight distinct families of IS elements with associated transposases: the IS_1111A_, IS_30_, IS_As1_, IS_652_, and IS_4_ families, as well as three unknown transposase types (see Table S8 in the supplemental material). K has 59 IS elements, with 31 containing an intact transposase. G has 40 IS elements, with 33 containing an intact transposase. NM and Dugway have roughly the same number of IS elements (31 and 33, respectively); however, transposases are intact in only 5 Dugway IS elements while being intact in 28 NM IS elements. A single IS element (IS_4_ family) was found in the QpDG plasmid of Dugway. Other C. burnetii plasmids lack IS elements, although an IS element (IS_1111A_ family) is found adjacent to the integrated plasmid-like sequences of G.

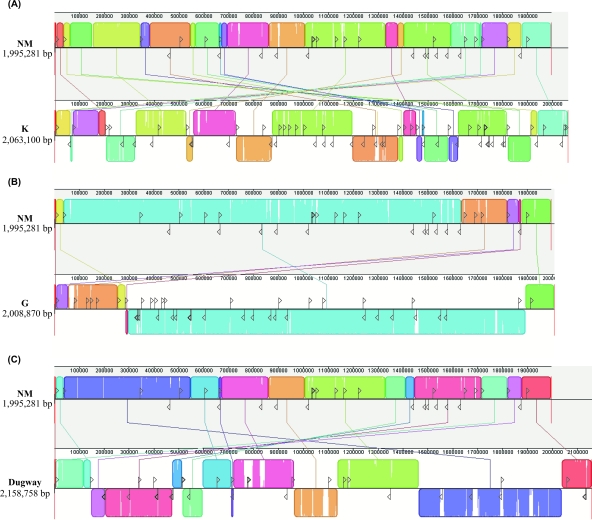

The movement of IS elements clearly contributes to C. burnetii genomic plasticity. Chromosomal rearrangements have resulted in 21, 6, and 13 syntenic blocks (defined as having the same gene order and gene content as NM) in K, G, and Dugway, respectively (Fig. 2 and 3; see Table S9 in the supplemental material). Two syntenic blocks are shared between K, G, and Dugway, with 5 shared between K and Dugway. G contains four novel syntenic blocks. Cumulatively, the syntenic blocks of K, G, and Dugway represent 40 chromosomal breakpoints relative to the NM chromosome. Of these, 30 (75%) have an intact or remnant IS element within 100 bp of the breakpoint (see Table S9 in the supplemental material), suggesting an important role for homologous recombination between IS elements in C. burnetii genome rearrangements. Homologous recombination has been demonstrated in the NM isolate (103). Moreover, intact recA is present in all four isolates, with functionality recently demonstrated for the NM ortholog Cbu1054 (67).

FIG. 2.

Alignment of NM, K, G, and Dugway chromosomes. Depicted are chromosomal rearrangements of K (Q154) (A), G (Q212) (B), and Dugway (5J108-111) (C) relative to the chromosome of the reference NM (RSA493) isolate. Each contiguously colored LCB represents a region without rearrangement of the homologous backbone sequence. LCBs were calculated with the Mauve 2.1.0 Muscle 3.6 aligner. Lines between genomes indicate orthologous LCBs. Average sequence similarities within LCBs are proportional to the height of the interior colored bars. LCBs containing sections of no similarity (white) indicate genome-specific sequence. LCBs below the center line represent blocks in the reverse orientation relative to the NM genome. The positions of IS (transposase genes) elements in each genome are indicated by black vertical lines, while their orientation is depicted by a triangle. Nucleotide alignments reveal that rearranged syntenic genomic blocks are often associated with IS elements.

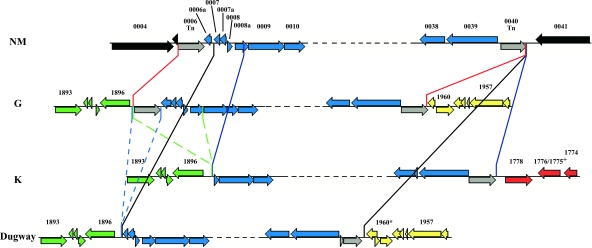

FIG. 3.

Transposon-mediated chromosomal rearrangements. Rearrangement of an NM ORF cluster bounded by IS_1111A_ transposases Cbu0006 and Cbu0040 is depicted. (The dashed black line represents NM ORFs Cbu0011 to Cbu0038.) Orange, blue, and black lines denote ORF cluster boundaries in G, K, and Dugway, respectively. Dotted green and blue lines indicate deletions relative to the G genome that could give rise to the 3′ end of the gene cluster in K and Dugway genome structures, respectively. K, G, and Dugway ORFs are numbered using NM annotation to identify the corresponding NM orthologs in these genomes. ORFs denoted with an asterisk or plus sign are frameshifted or fused relative to NM, respectively.

Figure 3 depicts a syntenic chromosomal region shared by the four isolates that was presumably rearranged by recombination of flanking IS_1111A_ elements. The region contains multiple genes encoding hypothetical proteins and housekeeping enzymes, such as prlC (Cbu0039 in NM) encoding oligopeptidase A, a protein involved in signal peptide degradation. In all isolates, the region is flanked at the 3′ end by a full-length or frameshifted IS_1111A_ element (Cbu0040 in NM). The next gene at the 3′ end in G and Dugway is an ortholog of NM Cbu1960 encoding a hypothetical cytosolic protein. In K it is an ortholog of NM Cbu1778 encoding fructose-bisphosphatase. At the 5′ end, only NM and G maintain the flanking IS element (Cbu0006 in NM). However, the upstream gene in G is an ortholog of Cbu1896 encoding a macrolide efflux pump. This gene also constitutes the 3′ end of the syntenic block in K and Dugway, with the IS element and the NM Cbu0006a ortholog deleted in Dugway. A larger deletion in K eliminates the IS element and orthologs of NM Cbu0006a, Cbu0007, Cbu0008, and a piece of Cbu0008a.

Expansion of IS elements, accumulation of pseudogenes (defined as genes disrupted by IS elements, small indels, or nonsense mutations), and numerous genomic rearrangements are associated with pathogens that have recently emerged from nonpathogens (82). An example is the facultative intracellular bacterium Francisella tularensis (89). A pathoadaptive evolutionary process is thought to result from bottlenecks encountered by small, isolated populations of a newly emerged pathogen whereby the new niche promotes gene decay by genetic drift (89). The obligate intracellular nature of C. burnetii, with its exploitation of host metabolic processes and limited opportunity for genetic exchange, would be expected to accelerate this process (2). Although genome reduction is clearly occurring in C. burnetii (96), it is nowhere near the extent of other obligate intracellular bacteria, such as Rickettsia prowazekii and Chlamydia trachomatis. These pathogens are apparently in the final stages of host cell adaptation and have cleared most pseudogenes from their respective genomes (2). A nonpathogenic progenitor of C. burnetii has not been identified; however, _Coxiella_-like endosymbionts of ticks are highly prevalent and may represent nonpathogenic ancestors of virulent C. burnetii (57).

The original NM genome annotation identified 83 pseudogenes, including those encoding transposases (96). Using cross-genome comparisons of the four isolate genomes and pseudogene criteria described in Materials and Methods, an additional 125 NM pseudogenes were revealed (see Tables S5 and S10 in the supplemental material). These data are consistent with recent findings that bacterial pseudogenes are frequently underannotated (79). Most new NM pseudogenes (78%) were originally annotated as ORFs encoding hypothetical proteins. The 207 total pseudogenes of NM represent 10.1% of NM ORFs (see Table S11 in the supplemental material). The K isolate has the highest percentage of pseudogenes (11.7%), while the Dugway isolate has the lowest percentage (6.6%) (see Table S11 in the supplemental material). Isolate pseudogenes are all caused by small indels or nonsense mutations, with none directly attributed to insertional disruption by an IS element. Sixty-five pseudogenes are conserved among C. burnetii isolates (see Tables S5 and S10 in the supplemental material), representing genes likely inactivated in a common ancestor.

Similar to a scenario recently proposed for pathogenic Francisella tularensis (89), IS element-mediated genome rearrangements may drive pseudogene development in C. burnetii. For example, in K, with 21 chromosomal breakpoints relative to NM, pseudogenes are enriched within 3 kb of a breakpoint (21.2%) (see Table S11 in the supplemental material). A proposed mechanism for IS element-mediated pseudogene formation is recombination between elements to result in transcriptional units that are no longer transcribed. Genes within these units then lack selective pressure and consequently accumulate mutations by genetic drift that result in their inactivation (89). Isolates display substantial heterogeneity in pseudogenes associated with virulence, such as the ankyrin-repeat protein (Ank)-encoding genes (discussed in more detail below), a factor that likely contributes to isolates' virulence potential and other phenotypes.

SNPs associated with nonsynonymous amino acid substitutions.

Orthologous genes showing high numbers of SNPs are generally considered to be under selective pressure. Relative to NM, a total of 9,154 SNPs were identified in full-length ORFs conserved between NM and K, G, and/or Dugway (see Table S12 in the supplemental material). Of these, 5,497 resulted in nonsynonymous amino acid changes. The 49 full-length ORFs conserved in K, G, and Dugway that collectively contain 13 or more nonsynonymous SNPs relative to the NM ortholog are listed in Table S13 in the supplemental material. Orthologs of NM Cbu0021 encoding a hypothetical protein were the most polymorphic, with 39 total SNPs. Genes encoding hypothetical membrane-spanning proteins, various transporters, and potential virulence factors, i.e., enhC, ankI, pilB, and icmE (discussed in more detail below) also contain high numbers of SNPs. Orthologs of NM genes encoding the surface proteins Com1 (Cbu1910) and P1 (Cbu0311), which are known to elicit strong antibody responses (112), contain disparate cumulative numbers of nonsynonymous SNPs (4 and 20, respectively) (see Table S13 in the supplemental material), suggesting that these surface proteins are under different selective pressure to antigenically vary.

Phylogenetics.

Several lines of evidence suggest that Dugway is more primitive than NM, K, or G. Dugway, with the largest chromosome and plasmid, appears to have undergone the least amount of genome reduction and has more unique ORFs (Tables 1 and 2; see Tables S1 and S3 in the supplemental material). The Dugway isolate also has the fewest pseudogenes (Tables 1 and 2) and IS_1111A_ insertion elements, an element that has particularly multiplied within other C. burnetii genomes (see Table S8 in the supplemental material). Of Dugway's 12 IS_1111A_ elements, 9 have genomically conserved positions in at least two other isolates. Moreover, 17 of Dugway's 33 insertion elements have genomically conserved positions in all isolates, with 6 of the 11 uniquely positioned insertion elements belonging to the IS_30_ family, which has multiplied solely within the Dugway genome.

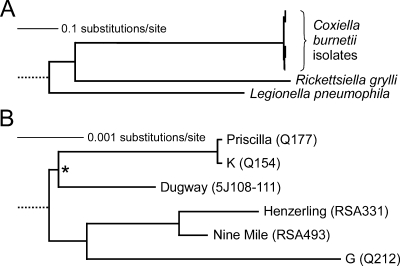

A multiprotein phylogenetic analysis was employed to test the hypothesis that Dugway is more primitive than NM, K, and G. Also included in this analysis were the recently completed genome sequence of Henzerling (RSA331), a human acute disease isolate, and the partially completed genome sequence of Priscilla (Q177), a goat abortion isolate (51). Comparisons were made to the most-closely related outgroup genera Rickettsiella (R. grylli) and Legionella (L. pneumophila) (92). Bayesian analysis of 1,402 families that contained one and only one representative from each C. burnetii isolate was conducted to gauge the vertical inheritance pattern of the genus (see Materials and Methods). While alignments of C. burnetii protein sequences yielded a supermatrix with a very large number (425,592) of amino acid characters, only a small percentage (0.82%) were informative.

The tree was rooted based on a separate study of 102 diverse Gammaproteobacteria which found the Coxiella/Rickettsiella/Legionella clade robustly supported, with no intervening genera (Fig. 4A) (K. P. Williams, J. J. Gillespie, E. E. Snyder, J. M. Shallom, E. K., Nordberg, A. W. Dickerman, and B. W. Sobral, unpublished data). The phylogenetic relatedness of these three genera correlates with conservation of homologous genes that likely accommodate common features of their intracellular lifestyles. For example, all carry a close homolog (e greater than −87) of Cbu0515, a major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporter (94). This protein may transport a vacuolar nutrient that overcomes a common auxotrophy of these bacteria (94). Genes are also exclusively shared between C. burnetii isolates and L. pneumophila, such as the enhABC cluster (Cbu1136-1138) that is implicated in macrophage invasion (21).

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic relationships of C. burnetii isolates. Consensus tree from Bayesian analysis of 1,402 combined protein sequences. (A) Full tree, rooted according to a study of 102 gammaproteobacteria based on 240 protein families (Williams et al., unpublished data). (B) C. burnetii portion only, at smaller scale. All C. burnetii nodes received 100% support in the original Bayesian analysis, in maximum-likelihood analysis of a set of bootstrap resamplings, and in Bayesian analysis of a set of jackknife resamplings, except for the node marked with an asterisk, which received 99%, 55%, and 62% support from the three analyses, respectively. In the third analysis, the remaining trees had the Dugway branch grouped with the G/NM/Henzerling clade (25%) or subtending both main C. burnetii clades (13%).

For C. burnetii isolates, a consensus tree showed 100% support for each node, except for the node grouping Dugway with the K and Priscilla pair, which received 99% support (Fig. 4B). Because multiprotein datasets can receive exaggerated Bayesian support values and the number of informative characters was relatively low, the robustness of the tree was tested by two different resampling methods, one generating trees by a maximum likelihood program and the other by Markov chain Monte Carlo. The consensus trees from both tests reproduced the original tree topology and again gave all nodes 100% support, except for that placing the Dugway branch, which in these tests received 55 to 62% support. Based on these data, the designation “ancestral” for Dugway is not directly supported since it does not subtend all other isolates on the tree. However, “primitive” is an accurate designation for the Dugway isolate, because it has the shortest distance to the root of the tree and has the previously mentioned features that are presumed to have been lost during the pathoadaptation process of more-virulent isolates.

Comparative metabolomics.

C. burnetii is metabolically complex relative to other obligate intracellular bacteria, with pathways of central carbon metabolism and bioenergetics largely intact (96). However, some notable deficiencies exist. All C. burnetii isolates encode a putative glucose transporter (Cbu0265), and biochemical evidence exits for conversion of glucose to pyruvate via glycolysis (44). However, they lack a hexokinase responsible for converting glucose to glucose-6-phosphate, the first step in glycolysis. As an alternative, C. burnetii isolates may phosphorylate glucose by a transphosphorylation reaction involving carbamoyl phosphate and a predicted inner-membrane-bound glucose-6-phosphatase (Cbu1267). A key pathway that appears inoperative is the oxidative branch of the pentose phosphate pathway. All isolates lack glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase. Thus, C. burnetii may not rely on this pathway to replenish reducing equivalents in the form of NADPH. This biochemical deficiency could contribute to low biosynthetic capacity and the slow growth rate of C. burnetii (24). All C. burnetii isolates lack the nonmevalonate (i.e., glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate-pyruvate) pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis that is common in gram-negative bacteria. Instead, they encode the mevalonate pathway (Cbu0607, Cbu0608, Cbu0609, and Cbu0610) that is found almost exclusively in gram-positive cocci and considered horizontally acquired from a primitive eucaryote (88, 110).

Isolate-specific gene polymorphisms are evident that may affect metabolic function. For example, isolate heterogeneity occurs within the MFS transporter family whose members transport a variety of molecules, including amino acids (18). NM contains 13 intact transporters, including three paralog groups (Cbu0906-Cbu1162, Cbu0902-Cbu0515, and Cbu0566-Cbu2067-Cbu2068) that presumably resulted from gene duplication. All NM MFS transporter ORFs are conserved in other isolates, although some are frameshifted (e.g., Cbu0432 is frameshifted in both K and G). K, G, and Dugway have 11, 12, and 13 intact transporter genes, respectively, and share CbuD1564, which is frameshifted in NM. Interestingly, most C. burnetii MFS transporters have homologs (e greater than −39) in L. pneumophila, such as phtJ that transports valine (18). This observation is consistent with C. burnetii's auxotrophy for this amino acid (96).

Gene polymorphisms in metabolic genes may also directly impact isolates' virulence potential. Clearance of C. burnetii during acute infection requires macrophage activation by gamma interferon (4). Among the gamma interferon-induced macrophage effector functions that limit bacterial replication is the upregulation of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). This enzyme degrades l-tryptophan to l-kynurenine (33), and a role for IDO in limiting C. burnetii growth has been suggested (13). Dugway may be less susceptible to IDO activity because, unlike NM, K, and G, it appears to be a tryptophan prototroph and capable of synthesizing the amino acid from chorismate via a putative trp operon encoding intact trpE (CbuD1249), trpG (CbuD1249a), trpD (CbuD1251), trpC (CbuD1251), a fused trpBF (CbuD1253), and intact trpA (CbuD1255). Other isolates apparently lack TrpD. Fused TrpBF is present in NM and K, while G instead appears to have intact TrpF and fused TrpAB. An unlinked tryptophan operon repressor, TrpR, is present in all isolates.

PV detoxification.

All C. burnetii isolates possess numerous enzymes capable of detoxifying deleterious reactive oxygen species, peroxides, and metals that may be present in the PV. These enzymes include iron-manganese and copper-zinc superoxide dismutases (Cbu1708 and Cbu1822, respectively), glutaredoxins (Cbu0583 and Cbu1520), thioredoxin peroxidases (Cbu0963 and Cbu1706), thioredoxins (Cbu0455 and Cbu2087), thioredoxin reductase (Cbu1193), rubredoxin (Cbu1881), and rubredoxin reductase (Cbu0276). All isolates also encode an apparent operon of two peroxide-scavenging alkyl hydroperoxide reductases (Cbu1477, ahpC, and Cbu1478, ahpD). Homologs of these proteins are found in L. pneumophila, where they provide critical peroxide-scavenging functions and may compensate for weak catalase activity of the organism's two bifunctional catalase-peroxidases (katA and katB) (61). Ahp proteins may serve a similar compensatory role in C. burnetii, with critical importance in NM and G where the single catalase gene (katE, Cbu0281) is severely truncated and likely nonfunctional. Isolate variation is also observed with the copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (Cbu1822), which is frameshifted in Dugway but intact in the other isolates. Mechanisms conserved by isolates that may protect against the PV's acidic pH include sodium ion/proton antiporters (e.g., Cbu1259 and Cbu1590) and an unusually high percentage of high isoelectric point proteins (i.e., over 26% of isolate proteins have predicted isoelectric points greater than 10). Protons that enter the C. burnetii cytoplasm may be buffered by basic proteins (96) or actively removed by transporters.

Secretion systems.

All C. burnetii isolates appear capable of type I secretion while lacking prototypical proteins required for type II secretion (20). Isolates contain a number of Pil genes that are involved in type IV pilus biogenesis and evolutionarily related to components of type II secretion systems (T2SSs) (84). Type IV pili are important virulence factors in a number of gram-negative bacteria, which act by promoting host cell adherence, twitching motility, biofilm formation, and secretion (16, 45). C. burnetii encodes core genes for type IV pilus biosynthesis, including pilA (Cbu0156; major prepilin), pilE (Cbu0412; minor prepilin), fimT (Cbu0453; minor prepilin), pilD (Cbu0153; peptidase/methylase), pilB (Cbu0155; ATPase), pilQ (Cbu1891; outer membrane secretin), pilC (Cbu0154; multispanning transmembrane protein), pilF (Cbu1855; uncharacterized envelope protein), and pilN (Cbu1889; uncharacterized envelope protein) (84). However, C. burnetii lacks a key gene required to synthesize a functional type IV pilus as all isolates lack a homolog to the ATPase PilT that presumably acts in concert with PilB to promote the pilus assembly and disassembly required for twitching motility (16). As recently suggested for Francisella novicida, the incomplete repertoire of C. burnetii type IV pilus genes may constitute a secretion system (45). Polymorphisms are found in Pil genes of Francisella spp. and are associated with virulence potential (36). C. burnetii isolates also display genetic heterogeneity in Pil genes, with apparent frameshifts in pilN of NM, pilC of K and G, and pilQ of G and Dugway which disrupt the functional domains of the latter two genes.

Substrates of L. pneumophila type II and F. novicida type IV pili secretion systems are biased toward signal sequence-containing enzymes (e.g., peptidases, glycosylases, phospholipases, and phosphatases) (29, 45). All C. burnetii isolates encode abundant enzymes with predicted signal sequences including phospholipase A1 (Cbu0489), phospholipase D (Cbu0968), acid phosphatase (Cbu0335), Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase (Cbu1822), and d-alanine-d-alanine carboxy peptidase (Cbu1261). Isolate variation is also observed in this group of genes, e.g., a gene encoding a predicted secreted chitinase (CbuD1225) is intact only in Dugway. Along with PV detoxification, C. burnetii exoenzymes could presumably degrade macromolecules into simpler substrates that could then be transported by the organism's numerous transporters.

While C. burnetii lacks a T3SS, it does encode a Dot/Icm T4SS homologous to that of L. pneumophila (97). All C. burnetii isolates contain 23 of the 26 L. pneumophila dot/icm genes. While all isolates lack a homolog of IcmR, a predicted chaperone for the pore-forming protein IcmQ (35), they contain a functional homolog of IcmR (Cbu1634a) immediately upstream of IcmQ (Cbu1634) (35). Dot/Icm secretion substrates that are translocated directly into the host cell cytosol are essential for the establishment of the L. pneumophila replication vacuole (107), and a similar scenario has been invoked for C. burnetii (108). L. pneumophila translocates over 50 proteins with its Dot/Icm T4SS, and these effector proteins target a variety of host cell functions (58, 78). With the possible exception of Cbu1063 and Cbu0414 (58), C. burnetii lacks homologs of these proteins, which is consistent with the pathogen's biologically distinct vacuolar niche (95). However, using L. pneumophila as a surrogate host and a well-established adenylate cyclase-based translocation assay, four C. burnetii ankyrin repeat domain-containing proteins (discussed in more detail below) were recently identified as Dot/Icm substrates (83). Finally, C. burnetii lacks autotransporter proteins indicative of type V secretion (50) and a newly described gram-negative T6SS (11).

Eucaryotic-like proteins.

A common property of bacterial virulence factors is their ability to functionally mimic the activity of host cell proteins (98). For example, it is clear that many predicted and documented T2SS and T4SS substrates of L. pneumophila are most similar to eucaryotic proteins and/or contain eucaryotic-like domains and were likely acquired via interdomain horizontal gene transfer (14, 29, 30). Similar to L. pneumophila, C. burnetii isolates collectively encode multiple eucaryotic-like proteins predicted to modulate host cell functions (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Eucaryotic-like ORFs of C. burnetii isolates

| ORF designation | ORF alias(es) in isolate: | Recognized motifa | Best e-value | G+C content (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM | K | G | Dugway | ||||

| None | Cbu1158 | CbuK1025 | CbuG0851b | CbuD1256 | Sterol reductase (sterol delta-7-reductase) | 8.4E-32 | 40.07 |

| None | Cbu1206 | CbuK1070 | CbuG0804 | CbuD1293 | Sterol reductase [ -sterol reductase] -sterol reductase] |

4.1E-156 | 39.72 |

| HmgA | Cbu0610 | CbuK1440 | CbuG1393 | CbuD0622 | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase | 4.0E-59 | 49.39 |

| None | Cbu0609 | CbuK1441 | CbuG1394 | CbuD0621 | Mevalonate kinase | 5.0E-14 | 43.14 |

| MvaK | Cbu0608 | CbuK1442 | CbuG1395 | CbuD0620 | Phosphomevalonate kinase | 8.0E-16 | 44.83 |

| MvaD | Cbu0607 | CbuK1443 | CbuK1396 | CbuD0619 | Diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase | 3.0E-36 | 43.21 |

| None | Cbu0175 | CbuK0362 | CbuG1837 | CbuD1925 | Protein kinase (STPK) | 2.3E-04 | 39.7 |

| None | Cbu1168-Cbu1168ab | CbuK1031b | CbuG0843b | CbuD1261 | Protein kinase (STPK) | 1.7E-10 | 36.95 |

| None | Cbu1377-Cbu1379b | CbuK1237 | CbuG0633c | CbuD1462e-CbuD1462fb | Protein kinase | 2.9E-09 | 37 |

| AnkP | Cbu0069-Cbu0070-Cbu0071b | CbuK1981a | CbuD2035 | Ankyrin repeats | 3.3E-02 | 43.68 | |

| AnkA | Cbu0072 | CbuK1982 | CbuD2034d | Ankyrin repeats | 2.8E-02 | 44.87 | |

| AnkB | Cbu0144-Cbu0145b | CbuK1907c | CbuG1870b | CbuD1961-CbuD1960b | Ankyrin repeats | 2.1E-07 | 45 |

| AnkC | Cbu0201 | CbuK0392 | CbuG1805 | CbuD1894 | Ankyrin repeats | 2.9E-07 | 48.09 |

| AnkD | Cbu0355-Cbu0356b | CbuK0551b | CbuG1652c | CbuD1724 | Ankyrin repeats and F box | 6.2E-03 and 5.7E-04 | 41.47 |

| AnkF | Cbu0477 | CbuK1384 | CbuG1537 | CbuD1598 | Ankyrin repeats | 3.3E-04 | 44.75 |

| AnkG | Cbu0781 | CbuK0651c | CbuG1220 | CbuD0829 | Ankyrin repeats | 4.2E-04 | 39.35 |

| AnkH | Cbu1024-Cbu1025b | CbuK0815b | CbuG0983b | CbuD1019 | Ankyrin repeats | 2.0E-05 | 38.54 |

| AnkI | Cbu1213c | CbuG0798 | CbuD1298 | Ankyrin repeats | 1.4E-03 | 39.2 | |

| AnkJ | Cbu1253-Cbu1254b | CbuK1113b | CbuG0758b | CbuD1337-CbuD1338b | Ankyrin repeats | 1.6E-06 | 38 |

| AnkK | Cbu1292 | CbuK1155 | CbuG0716 | CbuD1380 | Ankyrin repeats | 6.1E-10 | 40.57 |

| AnkL | Cbu1608-Cbu1609-Cbu1610-Cbu1611b | CbuK1835b | CbuG0406c | CbuD0382c | Ankyrin repeats | 1.8E-11 | 36 |

| AnkM | Cbu1757-Cbu1758b | CbuK0249b | CbuG0139c | CbuD0245 | Ankyrin repeats | 1.9E-06 | 40.66 |

| AnkN | CbuK1330 | CbuG1487 | CbuD1552-CbuD1553b | Ankyrin repeats | 1.4E-05 | 42.89 | |

| AnkO | CbuD1108 | Ankyrin repeats | 6.3E-08 | 39.32 | |||

| None | Cbu0814-Cbu0815-Cbu0816b | CbuK0684 | CbuG1185b | CbuD0881-CbuD0882b | F box and RCC domain | 8.4E-02 and 8.0E-17 | 42.09 |

| None | CbuA0014 | F box | 2.5E-03 | 35.93 | |||

| None | Cbu1217 | CbuK1077c | CbuG0795b | CbuD1300-CbuD1301b | Hect-like E3 ubiquitin ligase and RCC domain | 4.0E-11 and 8.0E-21 | 37.61 |

| None | CbuD1106-CbuD1107b | F box | 1.60E-01 | 33.93 | |||

| None | Cbu0820-Cbu0821b | CbuK0688 | CbuG1181b | CbuD0886 | LRR | 6.0E-04 | 38.37 |

| None | Cbu0295 | CbuK0492b | CbuG1710b | CbuD1787 | SEL1 TPR | 7.9E-03 | 38.79 |

| None | Cbu0530 | CbuK1306 | CbuG1464 | CbuD1533 | TPR | 1.1E-03 | 43.87 |

| None | Cbu0547 | CbuK1291 | CbuG1449 | CbuD1516 | TPR | 4.2E-11 | 39.99 |

| EnhC | Cbu1136 | CbuK1003 | CbuG0874 | CbuD1234d | SEL1 TPR (enhanced entry protein EnhC) | 4.4E-11 | 37.77 |

| None | Cbu1160 | CbuK1026d | CbuG0849 | CbuD1257d | TPR | 5.0E-08 | 35.52 |

| None | Cbu1364-Cbu1365b | CbuK1225c | CbuG0647b | CbuD1452 | TPR | 2.4E-07 | 40.1 |

| None | Cbu1457 | CbuK1685c | CbuG0554 | CbuD0496c | SEL1 TPR | 2.30E-09 | 40.58 |

| None | CbuD0785 | TPR | 1.00E-01 | 39.6 | |||

| None | CbuD0795 | TPR | 2.1E-03 | 43.84 | |||

| None | CbuDA0024 | SEL1 TPR | 2.9E-03 | 44.25 | |||

| None | Cbu0870 | CbuK0737 | CbuG1132 | CbuD0934 | TPR-like | 7.1E-23 | 35.37 |

| None | Cbu0488 | CbuK1372 | CbuG1525 | CbuD1588 | Metallophosphatase [bis(5′-nucleosyl)-tetraphosphatase] | 1.8E-12 | 43.83 |

| LpxH | Cbu1489 | CbuK1720 | CbuG0517 | CbuD0532 | Metallophosphatase (UDP-2,3-diacylglucosamine hydrolase) | 4.5E-12 | 43.07 |

| ApaH | Cbu1987 | CbuK2037 | CbuG1994 | CbuD2085 | Metallophosphatase [bis(5′-nucleosyl)-tetraphosphatase] | 9.0E-11 | 46.05 |

| None | CbuA0032 | CbuKA0035 | CbuDA0061 | Metallophosphatase (3′,5′-cyclic-nucleotide phosphodiesterase) | 4.7E-22 | 32.29 | |

| None | Cbu0189-Cbu0190b | CbuK0381 | CbuG1816b | CbuD1905-CbuD1906b | Cyclic nucleotide monophosphate binding metallophosphatase and CAAX amino-terminal protease | 7.1E-26 and 1.0E-04 | 35.57 |

| None | Cbu0593-Cbu0594-Cbu0595b | CbuK1245b | CbuG1406c | CbuD1472 | Cyclic nucleotide monophosphate binding metallophosphatase and CAAX amino-terminal protease | 1.6E-03 and 9.5E-04 | 38.76 |

| None | Cbu1482 | CbuK1713 | CbuG0524 | CbuD0526 | SPHF/band 7 domain (stomatin/prohibitin homologs) | 2.5E-52 | 44.44 |

| Cls | Cbu0096 | CbuK1960 | CbuG1921 | CbuD2014 | Cardiolipin synthetase | 8.5E-06 | 43.73 |

| None | Cbu0886a-Cbu0886bb | CbuK0752 | CbuG1115b | CbuD0952c | Patatin-like phospholipase | 1.9E-23 | 42.4 |

| None | Cbu0916a-Cbu0916bb | CbuK0919 | CbuG1087c | CbuD1157c | Cyclic nucleotide monophosphate binding metallophosphatase and patatin-like phospholipase | 4.4E-23 and 3.1E-44 | 35.93 |

| None | CbuDA0012 | Phospholipase D | 1.4E-06 | 42.38 | |||

| None | Cbu0898 | CbuK0763 | CbuG1104 | CbuD0962 | Thyroglobulin type-1 repeat (thyroid-related protein) | 5.0E-14 | 38.48 |

| None | Cbu0335c | CbuK0531 | CbuG1671 | CbuD1744 | Acid phosphatase | 9.9E-43 | 40.23 |

| None | Cbu1730 | CbuK0277 | CbuG0111 | CbuD0272 | Phosphoserine phosphatase | 2.0E-14 | 43 |

| DedA | Cbu0519 | CbuK1318 | CbuG1476 | CbuD1543 | SNARE-associated golgi protein | 9.6E-05 | 41.25 |

C. burnetii isolates encode two eucaryotic-like sterol reductases. One reductase (Cbu1206), annotated as a  -sterol reductase, displays the highest overall similarity to a eucaryotic protein, with no matches to procaryotic proteins. The other reductase (Cbu1158), annotated as a sterol delta-7-reductase, is most similar to a reductase of “Candidatus Protochlamydia amoebophila” UWE25, a _Parachlamydia_-related obligate endosymbiont of free-living amoebae (e greater than −180) (52). Cbu1158 has no additional matches to procaryotic proteins, with the next highest identity to a reductase from Arabidopsis thaliana (e greater than −135). While all C. burnetii isolates encode orthologs of Cbu1206, Cbu1158 is frameshifted in G. De novo synthesis of cholesterol or ergosterol by C. burnetii is improbable as the organism lacks the terminal enzymes of these pathways. Alternative scenarios include modification of a host cholesterol intermediate that could serve as a sterol-based signaling molecule or structural component of the PV membrane. Indeed, C. burnetii's infectious cycle is severely disrupted by pharmacological agents that disrupt host cell cholesterol metabolism (53). The maintenance of a sterol delta-7-reductase in modern day Protochlamydia and Coxiella suggests that the enzyme functions similarly in some key aspect of the host-parasite relationship, a hypothesis supported by the observation that vacuoles harboring Parachlamydia acanthamoebae in human macrophages are superficially similar to the C. burnetii PV in displaying endolysosomal characteristics (e.g., acidic and LAMP-1 positive) (40).

-sterol reductase, displays the highest overall similarity to a eucaryotic protein, with no matches to procaryotic proteins. The other reductase (Cbu1158), annotated as a sterol delta-7-reductase, is most similar to a reductase of “Candidatus Protochlamydia amoebophila” UWE25, a _Parachlamydia_-related obligate endosymbiont of free-living amoebae (e greater than −180) (52). Cbu1158 has no additional matches to procaryotic proteins, with the next highest identity to a reductase from Arabidopsis thaliana (e greater than −135). While all C. burnetii isolates encode orthologs of Cbu1206, Cbu1158 is frameshifted in G. De novo synthesis of cholesterol or ergosterol by C. burnetii is improbable as the organism lacks the terminal enzymes of these pathways. Alternative scenarios include modification of a host cholesterol intermediate that could serve as a sterol-based signaling molecule or structural component of the PV membrane. Indeed, C. burnetii's infectious cycle is severely disrupted by pharmacological agents that disrupt host cell cholesterol metabolism (53). The maintenance of a sterol delta-7-reductase in modern day Protochlamydia and Coxiella suggests that the enzyme functions similarly in some key aspect of the host-parasite relationship, a hypothesis supported by the observation that vacuoles harboring Parachlamydia acanthamoebae in human macrophages are superficially similar to the C. burnetii PV in displaying endolysosomal characteristics (e.g., acidic and LAMP-1 positive) (40).

Eucaryotic domains identified in C. burnetii proteins include ankyrin repeats, F boxes, serine/threonine protein kinases (STPK), tetratricopeptide repeats (TPR), leucine-rich repeats (LRR), and coiled-coil domains (CCD). C. burnetii isolates collectively encode 15 ankyrin repeat domain-containing proteins (Anks), although this protein family shows considerable heterogeneity among isolates in terms of frameshifting and truncation. Anks typically contain at least two tandem 33-residue ankyrin repeat motifs but can contain up to 34 repeats (74). Anks mediate protein-protein interactions that influence a variety of cellular processes, including transcription, endocytosis, and cytoskeletal rearrangements (74). The Dugway isolate encodes 11 full-length Anks, while the NM isolate encodes only 5. Four intact Ank genes (ankC, -F, -G, and -K) are conserved between the 4 isolates. Intact versions of ankD, -H, and -O are found only in Dugway, with ankO unique to this isolate. Intact versions of ankN are found only in K and G, and ankB, -J, and -L appear to be disrupted in all isolates. Both L. pneumophila and C. burnetii Anks are translocated into the host cytosol by a Dot/Icm-dependent mechanism (83). Of interest is the transcription and translocation of the C-terminal portion of frameshifted NM AnkB (Cbu0145) (83), suggesting that this and other disrupted effectors may still be functional.

Modulation of eucaryotic ubiquitin signaling pathways is an emerging theme in bacterial pathogenesis. Indeed, many bacterial F-box proteins are thought to possess ubiquitin ligase activity (5). C. burnetii isolates collectively encode three proteins (CbuA0014, Cbu0355, and Cbu0814) with predicted F boxes, a finding also made in a previous bioinformatic screen (5). This ∼50-amino-acid domain is typically N-terminally located and involved in ubiquitination processes that target proteins for degradation by the proteosome (56). Moreover, bacterial F-box-containing proteins are known substrates of T3SS and T4SS (5). Consistent with other F-box proteins, Cbu0355 and Cbu0814 contain additional C-terminal motifs involved in protein-protein interactions (56) in the form of ankyrin repeats and regulator of chromatin condensation (RCC) domains, respectively. The F-box domain comprises the majority of CbuA0014, which is only 77 amino acids long. An additional C. burnetii protein that is potentially ubiquitin-related is Cbu1217, with Hect-like E3 ubiquitin ligase domain similarity in its N terminus and multiple C-terminal RCC domains. Like the Anks, F-box proteins display considerable heterogeneity among C. burnetii isolates, with apparently full-length Cbu0814 and Cbu0355 present only in K and Dugway, respectively, and CbuA0014 specific to the QpH1 plasmid of NM. Moreover, Cbu1217 appears to be full-length in NM and K but frameshifted in G and Dugway.

C. burnetii isolates collectively encode three eucaryotic-like domain proteins with similarity to STPKs (Cbu0175, Cbu1168, and Cbu1379) that may directly impact host cell signal transduction. Mycobacterium tuberculosis secretes an STPK that is critical for the generation of its replication vacuole in macrophages (109), and a similar scenario may be associated with C. burnetii infection. Again, variation is observed in this family of proteins, with Cbu1168 orthologs apparently full-length only in Dugway and Cbu1379 full-length only in K.

The TPR is a 34-amino-acid motif, with the Sel-1-type TPR (SLR) displaying a variable consensus length of 36 to 44 amino acids (68). TPR/SLR repeats are arranged in tandem arrays and form antiparallel α-helices that promote folding of proteins into a solenoid tertiary structure (68). Proteins of this nature are frequently involved in signal transduction pathways, and the working model for TPR/SLR-containing proteins is that they function as adaptor proteins in building signaling complexes (68). Together, C. burnetii isolates encode seven TPR and four SLR proteins. Like the Ank proteins, Dugway encodes the most full-length TPR/SLR proteins, with two unique chromosomal TPR proteins and one unique QpDG plasmid SLR protein. Interestingly, L. pneumophila encodes three annotated SLR proteins (EnhC, LidL, and LpnE) that all appear to function in the early stages of pathogen uptake to establish the organism's vacuolar replicative niche (21, 25, 64, 75). As discussed earlier, only C. burnetii and L. pneumophila encode EnhC, containing 21 and 18 SLRs, respectively, suggesting that the protein was acquired from a common source to mediate replication vacuole biogenesis. EnhC is conserved among all C. burnetii isolates, although the Dugway version has a 34-amino-acid extension at the C terminus.

C. burnetii encodes one LRR protein (Cbu0820) that appears to be full-length only in K and Dugway. C. burnetii isolates also encode numerous hypothetical proteins with predicted CCDs (P > 85%) (data not shown), a structure that consists of interacting heptad α-helices (15). Of particular relevance to C. burnetii is the prevalence of these domains in SNARE (soluble _N_-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor) proteins that control vesicular fusion (15). Continuous fusion between the C. burnetii PV and endolysosomal/autophagosomal compartments is considered necessary for PV biogenesis and maintenance (108), and it is logical to suspect that the organism secretes a CCD protein(s) that modulates host regulators of these processes.

Because most genes encoding eucaryotic-like proteins are conserved, as intact genes or pseudogenes, between C. burnetii isolates, they were likely present in a common ancestor of isolate lineages. Given that C. burnetii lacks a system for conjugal gene transfer, interdomain transfer of at least some of these genes to an ancestral Coxiella organism may have occurred via two horizontal gene transfer events, the first occurring between a eucaryote and an intracellular bacterium with gene transfer capability that secondarily transferred the gene to the ancestral Coxiella organism (26). For example, C. burnetii may have acquired its sterol delta-7-reductase from “Ca. Protochlamydia amoebophila” UWE25, which encodes a potentially functional F-like DNA transfer system (39), after this ameobal symbiont, or ancestor with an expanded host range, acquired the enzyme via interdomain transfer with a eucaryotic host. Supporting the latter scenario is the observation that C. burnetii trpA, -B, and -C, which are tightly linked to the gene encoding the sterol delta-7-reductase, show unusually high degrees of identity with their counterparts in pathogenic chlamydiae. Pathogenic chlamydiae and “Ca. Protochlamydia amoebophila” UWE25 share a common ancestor (52); however, only the former encodes Trp biosynthesis genes. Thus, C. burnetii may have coincidently acquired Cbu1158 and Trp genes in a single horizontal gene transfer event that occurred with the common chlamydial ancestor and not “Ca. Protochlamydia amoebophila” UWE25.

Free-living amoeba-like single-cell protozoa have been proposed to serve as bacterial “melting pots” where promiscuous horizontal gene exchange can occur between internalized bacteria (80). This process has recently been proposed for Rickettsia bellii, whose genome contains a disproportionate number of genes from amoebal parasites, including L. pneumophila and “Ca. Protochlamydia amoebophila” UWE25 (80). Aided by lateral gene transfers, amoebae are furthermore speculated to serve as evolutionary “training grounds” where ancestral amoeba-associated bacteria evolved to become pathogens of multicellular eucaryotes, a prototypic example being L. pneumophila (69). Laboratory studies show resistance of C. burnetii to destruction by the free-living amoeba Acanthamoeba castellanii (59); however, a niche for C. burnetii in environmental amoeba has not been demonstrated (41).

A C. burnetii pathogenicity island?

A NM pathogenicity island was proposed by Seshadri et al. (96) that is flanked by IS_1111A_ elements harboring the transposases Cbu1186 and Cbu1218. Cbu1187 to Cbu1208 is largely conserved among isolates, but this region lacks obvious virulence factors. A possible virulence protein in the form of AnkI (Cbu1213) is missing in K; however, this isolate shows substantial rearrangement following Cbu1187. Moreover, Dugway lacks the upstream IS element, while both Dugway and K lack the downstream IS element. Finally, the G+C content (43.0%) of this region does not differ significantly from that of the chromosome (Table 1), suggesting that this DNA was not acquired by horizontal gene transfer.

Signal transduction and gene regulation.

Relative to gram-negative facultative intracellular bacteria, C. burnetii has a paucity of potential two-component regulatory systems. This likely reflects a stable environmental intracellular niche (73) and is observed in most (3, 100) but not all (19) obligate intracellular bacteria. C. burnetii encodes only four obvious two-component systems: PhoB-PhoR (Cbu0367-Cbu0366), QseB-QseC (Cbu1227-Cbu1228), GacA-GacS (LemA) (four potential response regulators and Cbu0760), and an unclassified response regulator-RstB-like system (Cbu2005-Cbu2006). Four CsrS-like sensory kinases are also present in isolates, with Cbu0634 truncated in NM and K. The stimulus of RtsB is unknown, while PhoB-PhoR senses phosphate in Escherichia coli (7). GacA-GacS regulates the production of multiple virulence factors in gram-negative bacteria (46). Moreover, the activation of GacA-GacS homologs in L. pneumophila (LetA-LetS) during stationary phase derepresses the activity of the mRNA binding protein CsrA and results in pathogen differentiation to a stress-resistant transmission phase (70, 71). In L. pneumophila, limiting nutrients results in production of the alarmone ppGpp by SpoT and RelA that, in addition to LetA-LetS, activates the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS, which can also upregulate transmission-phase genes (70, 71). It is conceivable that a C. burnetii GacA-GacS pair functions similarly to L. pneumophila LetA-LetS. The C. burnetii SCV developmental form is biologically reminiscent of the L. pneumophila transmission phase, and the conservation in all C. burnetii isolates of spoT (Cbu0303), relA (Cbu1375), rpoS (Cbu1609), and csrA (Cbu0024 and Cbu1050) suggests similar roles for these genes in C. burnetii biphasic development. Other developmentally regulated genes, such as hcbA and scvA, that encode SCV-specific DNA binding proteins (47, 48), are also conserved in all isolates. The sensor kinase QseC has recently been described as a bacterial adrenergic receptor that recognizes bacterial autoinducers and the eucaryotic hormones epinephrine/norepinephrine (22). Interestingly, C. burnetii QseB-QseC has also been classified as a PmrA-PmrB-type two-component system (113). In Salmonella enterica, PmrA-PmrB acts coordinately with PhoP-PhoQ to regulate resistance to cationic peptides and Fe3+ and is activated by submillimolar Fe3+ and low pH (∼5.8) (85). Moreover, PmrA has been shown directly and indirectly to regulate Dot/Icm type IV secretion in L. pneumophila and C. burnetii, respectively (113). CpxA-CpxR, another two-component regulator of the L. pneumophila Dot/Icm T4SS (34), is lacking in C. burnetii.

In summary, the four-way genome comparison in this report provides a comprehensive view of C. burnetii's genome architecture and gene content. Highlighting C. burnetii's obligate relationship with a eucaryotic host is evidence of interdomain horizontal gene transfer. Gene loss in the form of pseudogene formation appears to be the major source of genomic diversity among C. burnetii isolates, an evolutionary process facilitated by IS element-mediated chromosomal rearrangements. Thus, isolate-specific repertoires of pseudogenes, such as those in the Ank gene family, may impact isolates' virulence potential. The observation that Dugway has the largest genome with the fewest pseudogenes suggests that this lineage is the least pathoadapted, a hypothesis that is consistent with lack of human disease isolates in Dugway's genomic group and the isolate's attenuated virulence in animal models of Q fever. The pathogenetic correlates of disease potential described in this report provide the foundation for testable hypotheses related to gene function and C. burnetii virulence.

Supplementary Material

[Supplemental material]

Acknowledgments

We thank Anamitra Bhattacharyya and Theresa Walunas for assistance during the course of this work.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R.A.H.), and by Public Heath Service grant AI057156 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (J.E.S.).

Footnotes

▿

Published ahead of print on 1 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amano, K., and J. C. Williams. 1984. Chemical and immunological characterization of lipopolysaccharides from phase I and phase II Coxiella burnetii. J. Bacteriol. 160994-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson, J. O., and S. G. Andersson. 1999. Insights into the evolutionary process of genome degradation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 9664-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson, S. G., A. Zomorodipour, J. O. Andersson, T. Sicheritz-Ponten, U. C. Alsmark, R. M. Podowski, A. K. Naslund, A. S. Eriksson, H. H. Winkler, and C. G. Kurland. 1998. The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria. Nature 396133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andoh, M., G. Zhang, K. E. Russell-Lodrigue, H. R. Shive, B. R. Weeks, and J. E. Samuel. 2007. T cells are essential for bacterial clearance, and gamma interferon, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and B cells are crucial for disease development in Coxiella burnetii infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 753245-3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angot, A., A. Vergunst, S. Genin, and N. Peeters. 2007. Exploitation of eukaryotic ubiquitin signaling pathways by effectors translocated by bacterial type III and type IV secretion systems. PLoS Pathog. 3e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arricau-Bouvery, N., Y. Hauck, A. Bejaoui, D. Frangoulidis, C. C. Bodier, A. Souriau, H. Meyer, H. Neubauer, A. Rodolakis, and G. Vergnaud. 2006. Molecular characterization of Coxiella burnetii isolates by infrequent restriction site-PCR and MLVA typing. BMC Microbiol. 638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baek, J. H., and S. Y. Lee. 2006. Novel gene members in the Pho regulon of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 264104-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beare, P. A., S. F. Porcella, R. Seshadri, J. E. Samuel, and R. A. Heinzen. 2005. Preliminary assessment of genome differences between the reference Nine Mile isolate and two human endocarditis isolates of Coxiella burnetii. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 106364-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beare, P. A., J. E. Samuel, D. Howe, K. Virtaneva, S. F. Porcella, and R. A. Heinzen. 2006. Genetic diversity of the Q fever agent, Coxiella burnetii, assessed by microarray-based whole-genome comparisons. J. Bacteriol. 1882309-2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benenson, A. S., and W. D. Tigertt. 1956. Studies on Q fever in man. Trans. Assoc. Am. Physicians 6998-104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bingle, L. E., C. M. Bailey, and M. J. Pallen. 2008. Type VI secretion: a beginner's guide. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanc, G., H. Ogata, C. Robert, S. Audic, J. M. Claverie, and D. Raoult. 2007. Lateral gene transfer between obligate intracellular bacteria: evidence from the Rickettsia massiliae genome. Genome Res. 171657-1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brennan, R. E., K. Russell, G. Zhang, and J. E. Samuel. 2004. Both inducible nitric oxide synthase and NADPH oxidase contribute to the control of virulent phase I Coxiella burnetii infections. Infect. Immun. 726666-6675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruggemann, H., C. Cazalet, and C. Buchrieser. 2006. Adaptation of Legionella pneumophila to the host environment: role of protein secretion, effectors and eukaryotic-like proteins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 986-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burkhard, P., J. Stetefeld, and S. V. Strelkov. 2001. Coiled coils: a highly versatile protein folding motif. Trends Cell Biol. 1182-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burrows, L. L. 2005. Weapons of mass retraction. Mol. Microbiol. 57878-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castresana, J. 2000. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17540-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen, D. E., S. Podell, J. D. Sauer, M. S. Swanson, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 2008. The phagosomal nutrient transporter (Pht) family. Microbiology 15442-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho, N. H., H. R. Kim, J. H. Lee, S. Y. Kim, J. Kim, S. Cha, S. Y. Kim, A. C. Darby, H. H. Fuxelius, J. Yin, J. H. Kim, J. Kim, S. J. Lee, Y. S. Koh, W. J. Jang, K. H. Park, S. G. Andersson, M. S. Choi, and I. S. Kim. 2007. The Orientia tsutsugamushi genome reveals massive proliferation of conjugative type IV secretion system and host-cell interaction genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1047981-7986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cianciotto, N. P. 2005. Type II secretion: a protein secretion system for all seasons. Trends Microbiol. 13581-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cirillo, S. L., J. Lum, and J. D. Cirillo. 2000. Identification of novel loci involved in entry by Legionella pneumophila. Microbiology 1461345-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clarke, M. B., D. T. Hughes, C. Zhu, E. C. Boedeker, and V. Sperandio. 2006. The QseC sensor kinase: a bacterial adrenergic receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10310420-10425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cockrell, D. C., P. A. Beare, E. R. Fischer, D. Howe, and R. A. Heinzen. 2008. A method for purifying obligate intracellular Coxiella burnetii that employs digitonin lysis of host cells. J. Microbiol. Methods 72321-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coleman, S. A., E. R. Fischer, D. Howe, D. J. Mead, and R. A. Heinzen. 2004. Temporal analysis of Coxiella burnetii morphological differentiation. J. Bacteriol. 1867344-7352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conover, G. M., I. Derre, J. P. Vogel, and R. R. Isberg. 2003. The Legionella pneumophila LidA protein: a translocated substrate of the Dot/Icm system associated with maintenance of bacterial integrity. Mol. Microbiol. 48305-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox, R., R. J. Mason-Gamer, C. L. Jackson, and N. Segev. 2004. Phylogenetic analysis of Sec7-domain-containing Arf nucleotide exchangers. Mol. Biol. Cell 151487-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darling, A. C., B. Mau, F. R. Blattner, and N. T. Perna. 2004. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 141394-1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis, G. E., and H. R. Cox. 1938. A filter-passing infectious agent isolated from ticks. I. Isolation from Dermacentor andersonii, reactions with animals, and filtration experiments. Public Health Rep. 532259-2276. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Debroy, S., J. Dao, M. Soderberg, O. Rossier, and N. P. Cianciotto. 2006. Legionella pneumophila type II secretome reveals unique exoproteins and a chitinase that promotes bacterial persistence in the lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10319146-19151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Felipe, K. S., S. Pampou, O. S. Jovanovic, C. D. Pericone, S. F. Ye, S. Kalachikov, and H. A. Shuman. 2005. Evidence for acquisition of Legionella type IV secretion substrates via interdomain horizontal gene transfer. J. Bacteriol. 1877716-7726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dyer, R. E. 1938. A filter-passing infectious agent isolated from ticks. IV. Human infection. Public Health Rep. 532277-2282. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edgar, R. C. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 321792-1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fehlner-Gardiner, C., C. Roshick, J. H. Carlson, S. Hughes, R. J. Belland, H. D. Caldwell, and G. McClarty. 2002. Molecular basis defining human Chlamydia trachomatis tissue tropism. A possible role for tryptophan synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 27726893-26903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feldman, M., and G. Segal. 2007. A pair of highly conserved two-component systems participates in the regulation of the hypervariable FIR proteins in different Legionella species. J. Bacteriol. 1893382-3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feldman, M., T. Zusman, S. Hagag, and G. Segal. 2005. Coevolution between nonhomologous but functionally similar proteins and their conserved partners in the Legionella pathogenesis system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10212206-12211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forsberg, A., and T. Guina. 2007. Type II secretion and type IV pili of Francisella. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1105187-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glazunova, O., V. Roux, O. Freylikman, Z. Sekeyova, G. Fournous, J. Tyczka, N. Tokarevich, E. Kovacava, T. J. Marrie, and D. Raoult. 2005. Coxiella burnetii genotyping. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 111211-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenberg, D. E., S. F. Porcella, A. M. Zelazny, K. Virtaneva, D. E. Sturdevant, J. J. Kupko III, K. D. Barbian, A. Babar, D. W. Dorward, and S. M. Holland. 2007. Genome sequence analysis of the emerging human pathogenic acetic acid bacterium Granulibacter bethesdensis. J. Bacteriol. 1898727-8736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greub, G., F. Collyn, L. Guy, and C. A. Roten. 2004. A genomic island present along the bacterial chromosome of the Parachlamydiaceae UWE25, an obligate amoebal endosymbiont, encodes a potentially functional F-like conjugative DNA transfer system. BMC Microbiol. 448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greub, G., J. L. Mege, J. P. Gorvel, D. Raoult, and S. Meresse. 2005. Intracellular trafficking of Parachlamydia acanthamoebae. Cell. Microbiol. 7581-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greub, G., and D. Raoult. 2004. Microorganisms resistant to free-living amoebae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17413-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guindon, S., and O. Gascuel. 2003. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52696-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]