Chromatin remodelling during development (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2011 Mar 18.

Published in final edited form as: Nature. 2010 Jan 28;463(7280):474–484. doi: 10.1038/nature08911

Abstract

New methods for the genome-wide analysis of chromatin are providing insight into its roles in development and their underlying mechanisms. Current studies indicate that chromatin is dynamic, with its structure and its histone modifications undergoing global changes during transitions in development and in response to extracellular cues. In addition to DNA methylation and histone modification, ATP-dependent enzymes that remodel chromatin are important controllers of chromatin structure and assembly, and are major contributors to the dynamic nature of chromatin. Evidence is emerging that these chromatin-remodelling enzymes have instructive and programmatic roles during development. Particularly intriguing are the findings that specialized assemblies of ATP-dependent remodellers are essential for establishing and maintaining pluripotent and multipotent states in cells.

An essential aspect of building a mammalian cell is packing 1.7 metres of DNA into a 5-micrometre nucleus in a form that allows it to be replicated and transcribed in stable, tissue-specific patterns. The basic unit of chromatin assembly is the nucleosome1, which compacts DNA about sevenfold. However, because the overall level of compaction of the vertebrate genome is several thousand fold, relatively little of the DNA in vertebrates is present on simple nucleosomal templates in vivo. Instead, most chromatin is present in undefined, highly compacted structures that remain available for the induction of developmental programs that specify cell fate and morphogenesis.

At least three processes control the assembly and regulation of chromatin: DNA methylation (see ref. 2 for a review); histone modifications (see ref. 3 for a review); and ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling, which is the focus of this Review. ATP-dependent remodelling seems to be crucial for both the assembly of chromatin structures and their dissolution. About 30 genes encode the ATPase subunits of these complexes in mammals. With few exceptions, these ATPases seem to be genetically non-redundant, with mutation of the encoding genes often having severe effects on the early embryo or giving rise to maternal-effect phenotypes (in which the phenotype of the embryo reflects the genotype of the mother). Indeed, in many cases, the genes encoding the ATPases or their subunits are haploinsufficient (that is, one copy is insufficient for development), indicating that their role in specific processes is rate limiting. Despite their genetic non-redundancy, the various ATPases seem to have similar activities when studied in vitro: they all increase nucleosome mobility4. Therefore, it is clear that better in vitro assays are needed to tease apart their biological functions.

With the advent of genome-wide analysis techniques such as combining chromatin immunoprecipitation with serial analysis of gene expression (ChIP–SAGE) or with massively parallel sequencing (ChIP–Seq), our understanding of chromatin regulation has improved markedly5. These approaches, combined with rapid RNA interference (RNAi) screening and simpler genetic methods, are allowing a new appreciation of the role of the ATP-dependent remodellers in development, particularly in stem cells. Here, we review the key developmental roles of the four classes of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling enzyme in Drosophila melanogaster and mice, and we present evidence that these remodellers have an important role in establishing and maintaining the pluripotency of embryonic stem cells, perhaps as a result of the unique configuration of the chromatin ‘landscape’ of a pluripotent cell. These studies show that chromatin remodellers consist of a large number of assembled complexes, some of which are cell-type specific and developmental-stage specific. Many of these assemblies have specialized and largely non-redundant functions during development.

ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling families

ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling complexes seem to have evolved to accommodate the major changes in chromatin regulation that occurred during the evolution of vertebrates from unicellular eukaryotes (Box 1). As an example, complexes of the SWI/SNF family, which is one of the most-studied families of chromatin-remodelling complexes, have lost, gained and shuffled subunits during evolution from yeast to vertebrates. In particular, the transition to vertebrate chromatin-remodelling complexes involved the expansion of several of the gene families encoding the subunits and the use of combinatorial assembly, which together are predicted to allow the formation of several hundred complexes. But what is the advantage of combinatorial assembly?

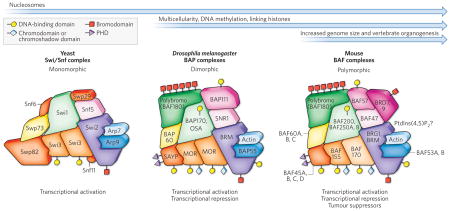

Box 1. Evolutionary diversification of SWI/SNF complexes.

During the evolution of multicellularity and complex body plans, the demand for tissue-specific and developmental-stage-specific expression of genes coincides with increased complexity in chromatin organization and in strategies for chromatin regulation. In the figure, the arrows represent the timescale of evolution, and the appearance of specific strategies of chromatin regulation is indicated, together with relevant important developments in eukaryotic evolution. For instance, the chromatin of yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), which is unicellular, is simpler than that of vertebrates and does not contain linker histones or methylated DNA, the latter of which is also rare in Drosophila melanogaster.

ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling enzymes also evolved, and we take SWI/SNF complexes as an example. In the figure, the homologous subunits of these complexes in yeast, D. melanogaster and mice are shown as similar shapes of the same colour, allowing them to occupy specific positions in the illustration of the complex, as in a jigsaw puzzle. The domains that enable the subunits to interact with DNA are depicted at the surface of each protein, as explained in the key. In yeast, these complexes are monomorphic in composition and seem to contribute mainly, if not exclusively, to transcriptional activation and transcriptional elongation.

The evolutionary emergence of multicellular organisms was accompanied by the loss of some of the subunits that are present in yeast Swi/Snf complexes (Snf6, Snf11, Swp29 and Swp82) and the gain of others. Unlike in yeast, there are two D. melanogaster SWI/SNF complexes — the Brahma (BRM)-associated proteins (BAP) complex and the polybromo-containing BAP (PBAP) complex, and these can mediate transcriptional activation and transcription repression. In the figure, these are depicted collectively as BAP complexes.

In the transition to vertebrate complexes, there was a large increase in the number of possible complexes as a result of vertebrates gaining the ability to combinatorially assemble several subunits encoded by gene families. The possible subunits at each position are listed in the figure (for example, BAF60A, B, C indicates that one of these three subunits is present). Some assemblies of the vertebrate SWI/SNF complexes known as brahma-associated factor (BAF) complexes are tissue-specific and have unique developmental roles, for example the npBAF complex (which is specific to neuronal progenitors) and the nBAF complex (which is specific to neurons) (Fig. 1). Other assemblies might coexist in a specific cell type and perhaps target specific genes or function together with specific transcription factors. As in D. melanogaster, PBAF complexes are a subset of mammalian BAF complexes defined by the incorporation of polybromo (also known as BAF180) and BAF200 (also known as ARID2), although these were purified from HeLa extracts and may represent partly assembled complexes. Thus, although the fundamental activity of promoting nucleosome mobility is highly conserved from yeast to humans, additional mechanisms that have not yet been discovered could account for the evolution of functionally different complexes. It is not known whether these ideas can be generalized to other ATP-dependent remodelling enzymes.

BRD, bromodomain-containing protein; BRG1, brahma-related gene 1; MOR, Moira; PHD, plant homeodomain; PtdIns(4,5)P2, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate; SAYP, supporter of activation of yellow protein; SNR1, Snf5-related protein 1.

One of the surprises of the genomic era is the relatively small number of genes that are present in vertebrates but not in flies (D. melanogaster). Hence, the greater complexity of vertebrates cannot be attributed to an increase in gene number. Instead, the vertebrate genome, which is about 30-fold larger than the fly genome, contains more genetic regulatory information outside protein-coding genes. Perhaps in response to this expansion of the genome, another strategy was used to regulate chromatin: combinatorial diversity. Current evidence indicates that many vertebrate chromatin-regulatory complexes are assembled combinatorially (see ref. 6 for a review), thereby greatly expanding the potential for diverse gene-expression patterns compared with unicellular eukaryotes. Arguably, the greatest need for diverse patterns of gene expression occurs in the development and function of the brain, and it may be no accident that an extraordinary diversity of neural phenotypes is emerging from genetic studies of the subunits of chromatin remodellers in the nervous system (see ref. 7 for a review).

The evolutionarily conserved SWI-like ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling complexes can be broadly divided into four main families on the basis of the sequence and structure of the ATPase subunit: SWI/SNF, ISWI, CHD and INO80 complexes. However, many of the predicted SWI/SNF-like ATPases do not fit any of these classes and await characterization. Why does the regulation of a genome require so many functionally non-redundant ATP-dependent chromatin remodellers if they all act to increase nucleosome mobility? Emerging evidence supports at least two possible explanations. First, new roles and molecular functions of chromatin remodellers have been discovered recently. For example, ISWI complexes have been shown to be required for maintaining the higher-order structure of the D. melanogaster male X chromosome8, and INO80 complexes are involved in telomere regulation, chromosome segregation, and checkpoint control and DNA replication during cell division (see ref. 9 for a review). Hence, it is becoming clear that SWI-like remodellers are intricately involved in many aspects of cell biology beyond transcription. Second, even within their traditional role of transcriptional regulation, ATP-dependent chromatin remodellers do not function in a consistent manner. Brahma-associated factor (BAF) complexes, which belong to the SWI/SNF family, can function as both transcriptional activators and repressors and can even switch between these two modes of action at the same gene10. In addition, tissue-specific BAF complexes have been reported to interact with a variety of transcription factors in different cell types (see ref. 11 for a review), allowing the complexes to take on context-dependent functions arising from their different interaction partners. For these reasons, the roles of ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling may be wider, yet more precise and programmatic, than was previously thought. Indeed, modulating the expression of a single target gene can partly suppress the phenotypes of mutations in the BAF complex in the heart12 and in post-mitotic neurons13. This focus on a single target is also seen for polycomb group (PcG) proteins. These proteins mediate transcriptional repression and often oppose the function of trithorax group (TrxG) genes such as those encoding BRG1 and MLL (discussed in the next section), by regulating chromatin structure. Early developmental effects of mutations in the mouse PcG gene Ring1b (also known as Rnf2) can be partly repressed by a mutation in Ink4a (also known as Cdkn2a or Arf), which is a BMI1-target gene and cell-cycle inhibitor14. In addition, late developmental effects of Bmi1 mutation can be partly repressed by null mutations of Chk2 (also known as Chek2), which normally induces a checkpoint evoked by the mitochondrial dysfunction in _Bmi1_-mutant mice15. Furthermore, the neural developmental phenotypes of mice lacking the TrxG protein MLL, can be reversed by rescuing expression of just one of its targets, Dlx2 (ref. 16). The surprising dedication of chromatin regulators to a single gene suggests that in vitro studies of mechanism will need to focus on appropriate biological targets in the correct cell type.

The diverse developmental roles of each family of chromatin remodeller in mammals are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. What emerges from this distillation is the large number of phenotypes associated with mutations in these complexes. It seems that most, if not all, developmental transitions require chromatin regulation and that such regulation is more specific than was initially thought. This is consistent with the findings mentioned above that alterations to single genes can often rescue at least part of the null phenotype. In retrospect, this conclusion is perhaps not surprising given that several hundred proteins seem to be involved in a non-redundant manner in chromatin regulation during development.

Table 1.

Roles of SWI/SNF chromatin-remodelling complex subunits in mammalian development

| SWI/SNF complex subunit (synonym) | Gene-family members | Developmental phenotype in mammals |

|---|---|---|

| BRM or BRG1 | NA | Brg1 knockout is peri-implantation lethal in mice26. BRG1 is required for zygotic genome activation25 and for differentiation into neurons24, lymphocytes10, adipose tissue92 and heart tissue40. BRG1 is essential in T-cell development, in which it suppresses Cd4 expression and activates Cd8 expression10,47. BRG1 is also essential during embryonic erythropoiesis for activation of expression of the β-globin gene93._Brm_-knockout mice are normal, with greater body mass27. |

| BAF250-family member (ARID1) | BAF250A, BAF250B and BAF250C | _Baf250a_-knockout mice die at E6.5. _Baf250a_-knockout mouse ESCs have reduced self-renewal capacity and defective mesodermal differentiation31._Baf250b_-knockout mouse ESCs have a propensity for spontaneous differentiation in culture28. |

| BAF155 and/or BAF170 | NA | Baf155 knockout is peri-implantation lethal in mice. Heterozygotes (Baf155+/−) have exencephaly owing to failure of neural tube closure35. |

| BAF47 (INI1, SNF5) | NA | Baf47 knockout is peri-implantation lethal in mice. Heterozygotes (Baf473+/−) develop sarcomas of the neural and soft tissues34. |

| BAF60-family member | BAF60A, BAF60B and BAF60C | BAF60C is expressed in the mouse heart and somites and is required for normal heart morphogenesis and establishment of left–right asymmetry40,41, and ectopic expression of BAF60C outside developing mouse heart regions is sufficient to specify development into cardiomyocytes42. |

| Actin | NA | The contribution of actin has been difficult to analyse because of its essential roles as a component of the cytoskeleton. |

| BAF53-family member | BAF53A and BAF53B | BAF53A is required for neuronal stem-cell proliferation in mice24.BAF53B is neuron specific and is required for activity-dependent dendritic outgrowth in mice13. |

| BAF57 | NA | A dominant-negative mutant of BAF57 prevents T-cell development in mice47. |

| BAF200 (ARID2) | NA | Not reported |

| Polybromo (BAF180) | NA | Polybromo is required for cardiac chamber maturation43 and coronary development44 in mice. |

| BAF45-family member | BAF45A, BAF45B, BAF45C and BAF45D | BAF45A is necessary and sufficient for neuronal progenitor proliferation in mice24.BAF45C is required for heart and muscle development in zebrafish39. |

| BRD7 or BRD9 | NA | BRD7 is essential for mouse ESC proliferation94. |

Table 2.

Roles of CHD, ISWI and INO80 chromatin-remodelling complexes in mammalian development

| ATPase | Other members of complex | Developmental phenotype in mammals |

|---|---|---|

| CHD family | ||

| CHD1 | SSRP1 | Chd1 knockdown in mouse ESCs renders them defective in multilineage differentiation, and they undergo global heterochromatinization of euchromatin67. |

| CHD2 | Unknown | CHD2-null mouse embryos have retarded growth and die before birth95. |

| CHD3 or CHD4 | NURD complex: HDAC1 or HDAC2; MTA1, MTA2 or MTA3; RbBP4 and/or RbBP7; MBD2 or MBD3; P66 | CHD4 is required for the development of T cells in the mouse thymus74 and for the self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells and differentiation along the myeloid lineage in the bone marrow75.MBD3-null mouse embryos die mid-gestation, owing to a failure of the inner cell mass to develop into a late epiblast and to the misregulation of several genes during the transition from pre-implantation to post-implantation72. |

| CHD5 | Unknown | CHD5 is a tumour-suppressor protein96 associated with human malignancies such as neuroblastomas97. |

| CHD7 | Unknown | CHD7 is mutated in CHARGE syndrome in humans76. CHD7-null mice show perinatal lethality and widespread tissue defects77. CHD7 is required for the proliferation and differentiation of olfactory stem cells98. |

| CHD9 | Unknown | CHD9 might be required for differentiation of osteogenic cells99. |

| ISWI family | ||

| SNF2H | NoRC complex: TIP5 WICH complex: WSTF | SNF2H-null mouse embryos implant but die between E5.5 and E7.5, owing to the failure of both the inner cell mass and the trophoblast to survive and grow58.The NoRC complex regulates cell growth by regulating the transcription of ribosomal DNA100.WSTF resides in the haploinsufficient region of human chromosome 7, which is responsible for Williams– Beuren syndrome. WSTF-null mice have cardiovascular defects similar to those of patients with Williams– Beuren syndrome60. |

| SNF2L | NURF complex: BPTF, and RbBP4 or RbBP7CERF complex: CECR2 | SNF2L knockdown in human cells leads to reduced expression of engrailed genes101. SNF2L expression in a neuroblastoma cell line potentiates neurite outgrowth101.BPTF-null mouse embryos die between E7.5 and E8.5, owing to defects in gastrulation, the absence of an anteroposterior axis and primitive streak, and lack of differentiation of mesoderm and definitive endoderm. BPTF-null ESCs are viable but defective in mesodermal and endodermal differentiation56.CECR2-null mouse embryos develop exencephaly and defects in neurulation57. |

| INO80 family | ||

| p400 | TIP60–p400 complex: TIP60 and TRRAP (and others as listed in ref. 85) | Depletion of TIP60, p400 or TRRAP from mouse ESCs by using RNAi results in altered (differentiated) ESC morphology87.TRRAP-null mouse embryos die at peri-implantation, owing to the failure of the blastocyst to proliferate86. |

Developmental roles of SWI/SNF complexes

SWI/SNF complexes are crucial for the proper development of all organisms in which they have been studied. In this section, we highlight their widespread developmental functions, emphasizing the importance of combinatorial diversity to their specialized roles throughout development.

BAP complexes and the organization of the insect body plan

In D. melanogaster, correct body segmental identity is determined by the proper expression patterns of homeotic genes of the Antennapedia complex and the Bithorax complex. Misexpression of homeotic genes leads to segmental transformations and other patterning defects. The expression patterns of genes in the Antennapedia and Bithorax complexes are first established by the actions of the gap and pair-rule groups of genes and are then maintained by the opposing actions of PcG proteins (which are repressive) and TrxG proteins (which are activating). The genes encoding the core homologues of yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) Swi/Snf in D. melanogaster — brahma (brm), osa and moira (mor) — were first identified in screens for suppressors of homeotic transformations caused by mutations in the Polycomb gene17 and were hence classified as TrxG genes. D. melanogaster SWI/SNF proteins are present and function in a multisubunit complex known as Brahma-associated proteins (BAP). Subsequently, analysis of several other subunits of the BAP complex — SNR1 (Snf5-related protein 1; a homologue of mammalian BAF47 and yeast Snf5) and SAYP (supporter of activation of yellow protein; also known as E(Y)3; a homologue of mammalian BAF45-family members) — showed that they are also required for the antagonism of PcG proteins18,19. By light microscopy, PcG proteins and BAP complex proteins are mutually exclusive on salivary-gland polytene chromosomes20 and PcG proteins might directly counteract the chromatin-remodelling activity and recruitment of the BAP complex to chromatin21.

Although maternal BAP complex proteins are required for the early stages of specifying segmental identity in D. melanogaster, when BRM or other components of the BAP complex are depleted from the zygote, this leads to multiple defects in organ and gamete formation and is lethal in embryos at late stages of development (see ref. 22 for a review), revealing that the roles of the BAP complex extend beyond antagonizing PcG proteins.

Developmentally distinct BAF complexes in mammalian development

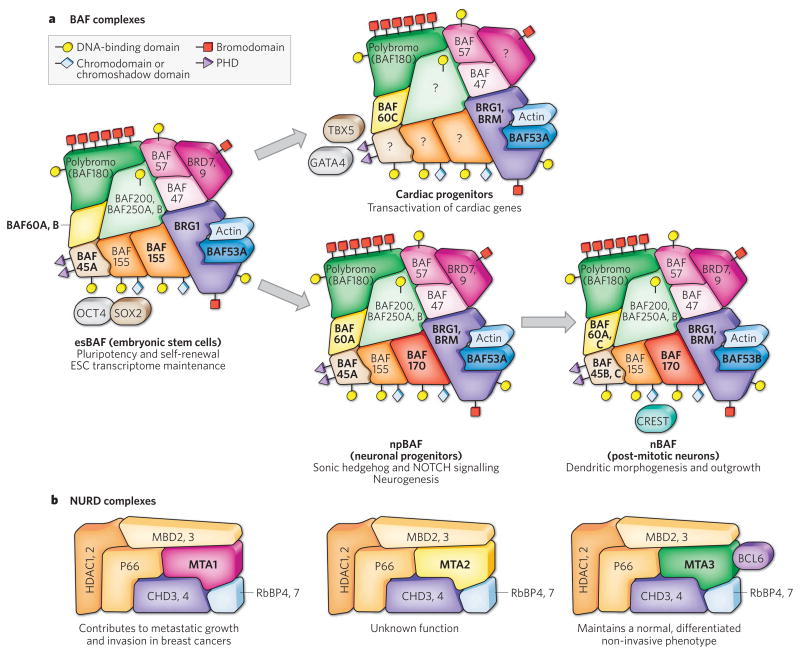

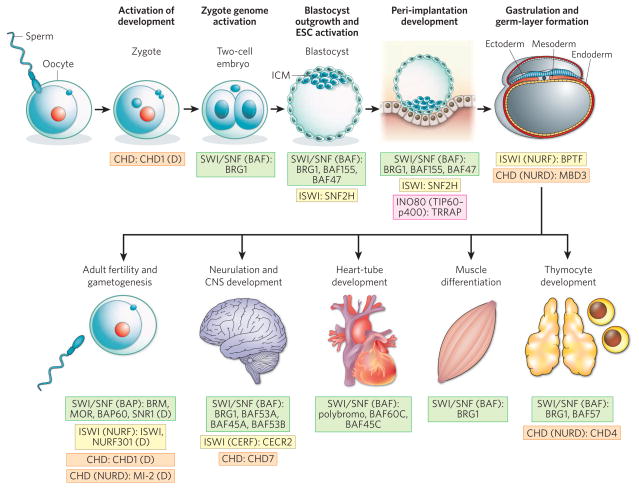

The mammalian homologues of the BAP complex have similarly widespread roles in development, although at present there is no evidence that mammalian complexes have TrxG-protein-like functions during the specification of segment identity in vertebrates. Studies of BAF complexes in mammals indicate that these complexes undergo progressive changes in subunit composition during the transition from a pluripotent stem cell to a multipotent neuronal progenitor cell to a committed neuron (Fig. 1a). In mammals, the ATPase subunit of the SWI/SNF complex is encoded by two homologues, Brm and Brg1 (brahma-related gene 1). The ATPase is 1 of 12 subunits that seem to be non-exchangeable in vitro. Several subunits are encoded by gene families (for example, BRG1 and BRM are encoded by one gene family, and only one of these is present in each complex), giving rise to a diversity of stable assemblies that differ between cell types and that have distinct functions23,24 (Fig. 1a). Mice deficient in either of the two ATPases have different phenotypes. Maternal Brg1 is required for zygotic genome activation in a two-cell-stage embryo25, and zygotic Brg1 is essential for both the survival and the proliferation of the cells of the inner cell mass and the trophoblast26 (Table 1 and Fig. 2). By contrast, _Brm_-knockout mice develop normally, albeit with a slight increase in body mass27. Consistent with the fact that lethality occurs near the time that the embryo is implanted in the uterine wall (at peri-implantation), recent studies have demonstrated that BAF complexes have a crucial role in maintaining the self-renewal and pluripotency of mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs)28–31. Mouse ESCs produce a complex called esBAF, which is characterized by containing BRG1 but not BRM, and BAF155 but not BAF170 (refs 28, 29); this complex regulates the core pluripotency transcriptional network of mouse ESCs32. So far, complexes containing BAF155 and not BAF 170 have not been found in other cell types. In addition to its role in transcriptional regulation during early embryogenesis, a homologue of BRG1 was also identified in a screen for genes that are essential for nuclear reprogramming in the cytoplasm of frog (Xenopus laevis) oocytes33. It is not clear whether the oocyte contains a specialized complex that is responsible for the nuclear-reprogramming activity. However, given that mouse ESCs are also capable of nuclear reprogramming, the complex present in oocytes might be akin to the esBAF complex. Additional evidence that the esBAF complex is essential for pluripotency comes from the observation that deletion of BAF47 or BAF155 is lethal to the embryo before it has implanted34,35. To differentiate into cells of different lineages, pluripotent ESCs need to exit from the state of self-renewal by silencing genes that potentiate the ESC state. BAF complexes are also crucial for this exit from the ESC state: this is evident from a study showing that RNAi-mediated depletion of BAF57 or BAF155 (components of esBAF) prevents silencing of Nanog, which encodes a master regulatory transcription factor, and also hinders chromatin compaction and hetero-chromatin formation during differentiation36.

Figure 1. Combinatorial assembly of chromatin-remodelling complexes produces biological specificity.

Brahma-associated factor (BAF) complexes (a) and nucleosome-remodelling and histone deacetylase (NURD) complexes (b). Analogous subunits of each complex are shown as similar shapes in the same colour, allowing them to occupy specific positions in the illustration of the complex, as in a jigsaw puzzle. The colour schemes in a and b are unrelated. The domains that enable the subunits to interact with DNA are depicted at the surface of each protein, as explained in the key. a, Tissue-type-specific and cell-type-specific assemblies of BAF complexes (which are members of the SWI/SNF family of chromatin-remodelling complexes) have distinct functions that are indispensable to their resident cell type. The diagram depicts the composition of BAF complexes in some of the primary cell types that have been characterized so far. In each case, the subunits shown are stable members of the complex; in some cases, they have been shown to be non-exchangeable in experimental challenges with an _in vitro_-synthesized subunit. The possible subunits at each position are listed (for example, BAF60A, B indicates that one of these two subunits is present). For subunits labelled with a question mark, it is unclear which family member is present at that position. The variable subunits that distinguish the complexes depicted here are highlighted in boldface type: these are the core ATPase (brahma-related gene 1 (BRG1) or brahma (BRM)), BAF45, BAF53, BAF60 and BAF155 and/or BAF170. The BAF complex in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) is called esBAF; in neuronal progenitors, npBAF; and in neurons, nBAF. In cardiac progenitors, the composition of the BAF complex is also distinct but has not been characterized by proteomic analysis, unlike the other BAF complexes shown. In the respective cell types, these complexes have been experimentally shown to mediate specific processes (which are listed below each complex) that cannot be mediated by BAF complexes of other compositions. In some cases, key transcription factors that work in cooperation with BAF complexes (such as OCT4 and SOX2 in ESCs, CREST in neurons and GATA4 and TBX5 in cardiac progenitors) are depicted. These transiently associated transcription factors are not shown in contact with the main complex to distinguish them from the subunits of the complex. b, NURD complexes (which are members of the CHD family of chromatin-remodelling complexes) incorporate different products of the MTA (metastasis-associated) gene family, and these complexes have distinct, and even opposing, functions in regulating the development and tumorigenesis of mammary tissues (see ref. 102 for a review). For example, MTA1-containing complexes repress oestrogen-receptor-mediated transcription and thereby contribute to the invasive growth of cancerous mammary tissue. By contrast, MTA3-containing complexes interact with BCL6 and directly repress the expression of metastasis-inducing gene Snail (also known as Snai1), thereby contributing to the maintenance of a non-invasive mammary phenotype. BAF200, also known as ARID1; BAF250, also known as ARID2; BRD, bromodomain-containing protein; HDAC, histone deacetylase; MBD, methyl-CpG-binding domain; PHD, plant homeodomain; RbBP, retinoblastoma-associated-binding protein.

Figure 2. Chromatin-remodelling complexes in development.

The four families of chromatin remodellers — SWI/SNF (green background), ISWI (yellow), CHD (orange) and INO80 (pink) — are required at distinct steps for the normal development of the development of embryos (implantation, gastrulation and organogenesis) and for the formation of gametes. The proteins known to be involved in mouse development are listed next to each step, together with the family of the complex involved (and the name of the specific complex, in parentheses, if known). In cases in which studies using mouse models have not been reported, proteins found to be involved in Drosophila melanogaster development are listed, as denoted by (D), although it is unclear whether these results can be extrapolated to mammalian development. BAF complexes are involved in most of the developmental transitions depicted. The requirement for BAF complexes throughout development could reflect the many combinatorial possibilities of BAF complex composition. However, the apparent involvement of BAF complexes more than other chromatin-remodelling complexes could just reflect that these complexes are the most widely studied of the chromatin remodellers. BAP, Brahma-associated proteins; BPTF, bromodomain PHD-finger transcription factor; CERF, CECR2-containing remodelling factor; CNS, central nervous system; ICM, inner cell mass; MOR, Moira; NURF, nucleosome-remodelling factor; SNR1, Snf5-related protein 1; TRRAP, transformation/transcription-domain-associated protein.

As ESCs differentiate into neuronal progenitors, the esBAF complex undergoes several subunit exchanges: it incorporates BRM and BAF60C and excludes BAF60B24,29 (Fig. 1a). BRG1 is required for the self-renewal of neuronal progenitors and for the normal differentiation of neurons from these progenitors24. BRG1-deficient neuronal progenitors misexpress key components of the NOTCH-and sonic-hedgehog-signalling pathways, which direct neurogenesis24. BAF45A is sufficient to induce the proliferation of neuronal progenitors past their normal mitotic exit point24. As neuronal progenitors leave their stem-cell niche in the subventricular zone of the brain and exit from mitosis, they express BAF45B and BAF53B, which replace BAF45A and BAF53A in the neuronal-progenitor-specific BAF (npBAF) complex to form a neuron-specific BAF (nBAF) complex24. The nBAF complex promotes activity-dependent dendritic outgrowth by interacting with the Ca2+-responsive dendritic regulator CREST (also known as SS18L1), thereby directly regulating genes essential for dendritic outgrowth13. The function of BAF53B in dendritic morphogenesis cannot be replaced by BAF53A, demonstrating the functional specialization of BAF complexes of different compositions. Genes encoding several subunits of BAF complexes were also found in an RNAi screen for factors involved in dendritic morphogenesis in D. melanogaster37, indicating that there is a conserved chromatin-regulatory program of dendritic morphogenesis. Interestingly, the downregulation of BAF53A during neuronal differentiation in mice is mediated by two microRNAs (miRNAs): miR-9* and miR-124 (ref. 38). These miRNAs are targeted by REST, a transcriptional repressor that is selectively downregulated in post-mitotic neurons. Mutating the miRNA-binding sites in the 3′-untranslated region of BAF53A gene leads to prolonged expression of BAF53A and reduced amounts of BAF53B in post-mitotic neurons. In accordance with the neuron-specific function of BAF53B, the persistent expression of BAF53A in neurons causes defects in activity-dependent dendritic outgrowth, illustrating the biological significance of subunit switching in BAF complexes during neural development. These studies suggest that the tissue-specific BAF complexes that arise from combinatorial assembly might allow matching between chromatin-remodelling complexes and ambient transcription factors, such as CREST in the case of post-mitotic neurons.

Additional evidence for this coordination between tissue-specific BAF complexes and transcription factors comes from studies of heart development. Baf45c-containing complexes are required for heart and muscle development in zebrafish (Danio rerio)39. In addition, BAF60C is selectively expressed in the regions of the mouse embryo that give rise to a heart and is required for morphogenesis of the heart, differentiation into cardiac and skeletal muscle cells40 and establishment of left–right asymmetry in the early embryo41. Remarkably, ectopic expression of BAF60C but not BAF60A, in coordination with the transcription factors GATA4 and TBX5, is sufficient to induce the development of beating cardiomyocytes from non-cardiogenic mesoderm in the developing embryo42 (Figs 1a and 2). Hence, BAF complexes are required for cardiac fate determination. But the closely related polybromo-containing BAF (PBAF) complexes (a subfamily of mouse SWI/SNF complexes defined by the incorporation of polybromo (also known as BAF180)) are expressed in the epicardium and have roles that are non-redundant with those of BAF60C in mediating coronary development and cardiac chamber maturation43,44. By contrast, PBAF complexes are not required for ESC formation or function: deletion of the signature subunit of these complexes, polybromo (BAF180), does not impair the formation of the inner cell mass or the production of different germ layers43.

The first evidence that BAF complexes could repress transcription through long-range interactions came from studies of mouse T cells. Normal T-cell development in the thymus depends on BAF complexes, although it is unclear whether thymocytes also have a specialized BAF complex. During development, T-cell differentiation is coupled to the differential expression of two co-receptors of the T-cell antigen receptor: CD4 and CD8. The expression of Cd4 is developmentally repressed by a distant silencer located 2 kb from the transcription start site of Cd4, and deletion of this silencer results in de-repression of Cd4 at an early stage of development45. The silencer binds to BRG1, BAF57 and presumably the entire BAF complex, which subsequently recruits a transcription factor required for Cd4 silencing, RUNX1 (which mediates repression by an unknown mechanism)46. BRG1-deficient thymocytes prematurely express CD4 and fail to activate CD8 expression, resulting in arrested thymocyte development47. This mode of action is distinct from that of the yeast Swi/Snf complex, which in all cases investigated is recruited to promoters by transcription factors in order to activate transcription48. Surprisingly, in mice, BRG1 is required again at a later stage to activate CD4 expression, indicating that BAF complexes can both activate and repress the transcription of a single gene10 depending on the developmental context. Because mammalian BAF complexes often repress transcription at a distance, whereas the yeast Swi/Snf complex always activates transcription by binding to promoters, there are likely to be significant mechanistic differences between these two complexes. These observations indicate that the initial nomenclature that we proposed, mSWI/SNF49, may be an inappropriate extrapolation.

BRG1 and BAF complexes might also be necessary for the induction of differentiation into skeletal muscle, given that the ability of the myogenic transcription factors MYOD1 and MEF2D to transactivate myogenic genes in mice was found to be inhibited by a dominant-negative allele of Brg1 (ref. 50) and also by short-hairpin-RNA-mediated depletion of BAF60C40.

Developmental roles of ISWI complexes

The second family of SWI-like ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling complexes is the ISWI family. These complexes were first identified in D. melanogaster, which has a single ISWI ATPase. This ATPase is the core component of three types of ISWI complex: NURF (nucleosome-remodelling factor), ACF (chromatin-assembly factor) and CHRAC (chromatin accessibility complex) complexes (see ref. 51 for a review). Loss-of-function mutations in Iswi are lethal during late pupal or larval development8, perhaps as a result of impaired expression of homeotic genes in the imaginal discs. Restricted expression of an ATPase-dead, dominant-negative allele of Iswi leads to defects in organogenesis, owing to its widespread role in cell viability and cell division8. More intriguingly, ISWI complexes are involved in regulating higher-order chromatin structure. This is evident from a study showing that dominant-negative Iswi or Iswi loss-of-function mutations results in marked global decondensation of mitotic chromosomes, owing to the apparent requirement for ISWI in incorporating the linker histone protein H1 (ref. 52), which is in turn required for normal chromosome condensation and compaction53. In females, ISWI deficiency leads to complete sterility8. This results from the misregulation of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-mediated gene expression in the germinal stem cells of females, which leads to a rapid loss of self-renewal of these stem cells54. Although the ISWI ATPase is present in three complexes, NURF might be the functionally predominant complex, because deletion of nurf301 (a dedicated component of the NURF complex) recapitulates almost all the phenotypes of the Iswi mutant55.

In mammals, the core ISWI ATPase is SNF2H or SNF2L. SNF2L and SNF2H have non-overlapping protein expression patterns in mice51. They are functionally distinct and are found in different complexes, as distinguished by their accessory subunits51 (Table 2). SNF2L is present in the NURF and CERF (CECR2-containing remodelling factor) complexes, whereas SNF2H is present in the NoRC (nucleolar remodelling complex), WICH (WSTF ISWI chromatin remodelling), ACF and human CHRAC complexes. NURF complexes and NoRC are involved in transcriptional activation and repression. By contrast, ACF, CHRAC and WICH complexes are required for the regulation of chromatin structure (including nucleosome assembly and spacing), the replication of DNA through heterochromatin and the segregation of chromosomes51.

There are no reports of Snf2l_-null mice. However, in mice, disruption of the gene encoding the largest subunit of mammalian NURF complexes, bromodomain PHD-finger transcription factor (Bptf),_ is lethal to the embryo between embryonic day (E) 7.5 and E8.5 (Fig. 2). In these organisms, although the inner cell mass forms normally, the embryo does not develop a distal or anterior visceral endoderm, leading to a lack of the anteroposterior axis and primitive streak and a lack of subsequent mesodermal and endodermal differentiation56. Although BPTF-null mouse ESCs are viable, they are impaired in their ability to generate mesodermal and endodermal cell fates. BPTF also interacts with transcription factors of the SMAD family and regulates BMP-mediated signalling during the establishment of the germ layers in the embryo56. Although this is reminiscent of ISWI function in the D. melanogaster ovary8, it is unclear whether mammalian NURF complexes are similarly required for proper oogenesis. The functions of ISWI are not limited to early embryonic development in mice. Although NURF complexes function during early embryonic patterning, another SNF2L-containing complex, the CERF complex, is required later in embryogenesis: deletion of the gene encoding the CERF-specific subunit CECR2 disrupts cranium formation and causes exencephaly57.

Mice deficient in SNF2H die after embryonic implantation (between E5.5 and E7.5, a checkpoint at which impaired proliferation is often associated with lethality) and have not been fully characterized58. The role of SNF2H-containing complexes in development is less clear than that of SNF2L-containing complexes, although the severe phenotype of _Snf2h_-null mice suggests that such complexes have crucial roles. An accessory subunit of the WICH complex, known as WSTF (Williams–Beuren syndrome transcription factor), is encoded in the 1.6-megabase haploinsufficient region of chromosome 7. This region is responsible for the genetic disorder Williams–Beuren syndrome in humans, a developmental disorder characterized by a specific form of mental ability or retardation combined with congenital cardiovascular disease and growth deficiency59. _Wstf_-haploinsufficient mice recapitulate the cardiovascular defects observed in human patients60. Hence, WICH complexes might be responsible for these phenotypes, through either their functions in regulating the replication of DNA or the assembly and structure of chromatin.

Developmental roles of CHD complexes

The third family of SWI-like ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling complexes is the CHD family. Theses complexes contain members of the CHD family of ATPases, which comprises nine chromodomain-containing members (see ref. 61 for a review) (Table 2). CHD proteins are broadly classified into three subfamilies based on their constituent domains: subfamily I (CHD1 and CHD2), subfamily II (CHD3 and CHD4) and subfamily III (CHD5, CH6, CHD7, CHD8 and CHD9).

CHD1 and global chromatin structure

The subfamily I member CHD1 was initially thought to be integral to transcriptional activity. The tandem chromodomain of human CHD was found to specifically recognize and bind to the trimethylated lysine residue at position 4 of histone H3 (H3K4me3; a hallmark of actively transcribed chromatin)62, mediating subsequent recruitment of post-transcriptional initiation and pre-messenger-RNA splicing factors63. However, this role in transcriptional activation is either not general or not conserved, because _Chd1_-mutant D. melanogaster zygotes are viable and display only a mild notched-wing phenotype. Instead, in D. melanogaster, CHD1 seems to have a more important role in gametogenesis and as a maternal product. Both _Chd1_-null male and female D. melanogaster are sterile64. In females, oogenesis depends on the presence of functional CHD1 (ref. 64) (Fig. 2). Closer examination reveals that _Chd1_-mutant females, when mated to wild-type males, lay fertilized eggs that die before hatching. Maternal CHD1 is required for the incorporation of H3.3 into the male pronucleus during decondensation after fertilization. Failure to incorporate H3.3 may render the paternal genome unable to participate in mitosis in the zygote, resulting in non-viable haploid embryos65. Interestingly, mutation of both genes encoding H3.3 in D. melanogaster recapitulates the Chd1 loss-of-function phenotype — that is, viable adults are completely sterile66 — suggesting that this remodeller is specifically dedicated to H3.3 incorporation during early development after fertilization.

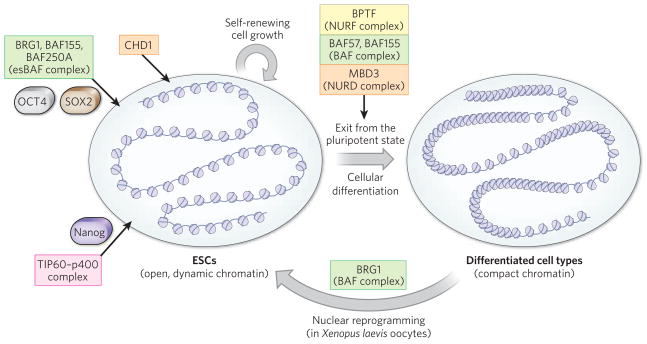

Although there are no reports of _Chd1_-knockout mice, RNAi-mediated depletion of CHD1 in mouse ESCs results in a loss of pluripotency. CHD1 seems to maintain mouse ESC chromatin in a hyperdynamic and euchro-matic state, thereby preserving lineage plasticity67 (Fig. 3). The findings in mice therefore seem inconsistent with the phenotype of null mutants in D. melanogaster. Developing null mice in which Chd1 can be conditionally deleted will be essential to test these conclusions rigorously.

Figure 3. Chromatin-remodelling complexes in maintaining pluripotency.

ESCs are characterized by hyperdynamic chromatin, which is compacted when these cells exit from their pluripotent state and differentiate into cells of multiple lineages103. In the self-renewing state, chromatin remodellers are required to prevent this chromatin compaction (CHD1) and to repress and refine the inappropriate expression of genes (esBAF and the TIP60-p400 complex) that would otherwise be allowed by the permissive chromatin landscape. Exit from this self-renewing state into a state that allows multilineage commitment involves global changes in chromatin configuration, such as the formation of heterochromatin and the silencing of pluripotency genes (BAF complexes and NURD complexes), and key signalling events (bone-morphogenetic-protein-mediated signalling pathway and NURF complexes). Not surprisingly, evidence is emerging that chromatin remodellers such as BAF complexes (by way of an unknown mechanism) are crucial for the reversal of development and the reactivation of pluripotency genes such as Oct4, which occurs during the nuclear reprogramming of a committed cell type back into an ESC-like state. The proteins known to be involved are listed, together with the chromatin-remodelling complex they are found in (CHD, orange; SWI/SNF, green; ISWI, yellow; and INO80, pink).

Combinatorial assembly of NURD complexes

In mammals, the subfamily II members CHD3 and CHD4 are subunits of NURD (nucleosome-remodelling and histone deacetylase) complexes, which contain histone deacetylases (HDACs) and function as transcriptional repressors68. Like BAF complexes, mammalian NURD complexes achieve diversity in regulatory function through combinatorial assembly (Fig. 1b). The core ATPase is CHD3 or CHD4. There are three main accessory subunits, which are encoded by gene families: MTA (metastasis-associated), MBD (methyl-CpG-binding domain) and RbBP (retinoblastoma-associated-binding protein). Each complex contains one MTA protein: MTA1, MTA2 or MTA3. These are mutually exclusive (see ref. 69 for a review) and nucleate complexes with markedly different, and sometimes opposite, functions. Each complex also contains MBD2 or MBD3, which are functionally distinct and contribute to different forms of the complex70, and RbBP4 and/or RbBP7. The composition of the NURD complexes varies with cell type and in response to signals within a tissue (see ref. 71 for a review), giving rise to a diversity of complexes with distinct functions.

Genetic studies of components of the mammalian NURD complex have shed light on its functions during development. Inactivation of mouse Mbd3 results in death during mid-gestation, stemming from the failure of the inner cell mass to develop into a mature epiblast and the subsequent failure of embryonic and extra-embryonic tissues to organize properly after implantation72. Surprisingly, _Mbd3_-null ESCs are viable and can initiate differentiation in culture, but they fail to commit to developmental lineages, as a result of impaired silencing of pluripotency genes73. Loss of Mbd3 results in the failure to assemble NURD complexes and probably reflects a loss of function for these complexes. Hence, the NURD complex is crucial for the correct silencing of genes during early development to allow proper patterning and lineage commitment. NURD complexes are also required in later development. Conditional inactivation of Chd4 in the haematopoietic cells of mice leads to impaired haematopoietic stem-cell homeostasis and impaired differentiation into myeloid cells, and to defective thymocyte development and defective activation of the Cd4 locus74,75. Thus it seems that NURD and BAF complexes have specific, opposing, roles at the Cd4 locus.

CHD7 and CHARGE

The most extensively studied member of CHD subfamily III is CHD7. Mutations in CHD7 result in CHARGE syndrome in humans (which is characterized by coloboma of the eyes, heart defects, choanal atresia, severe retardation of growth and development, and genital and ear abnormalities)76 and more than 40 alleles have been defined. _Chd7_-heterozygous (Chd7+/−) mice recapitulate several aspects of the human disease, such as inner-ear vestibular dysfunction (resulting from defective sensory epithelial innervation)77. Molecular studies suggest that CHD7 is involved in transcriptional activation of tissue-specific genes during differentiation78. Indeed, the D. melanogaster counterpart of Chd7, kismet, may be globally required for RNA-polymerase-II-driven elongation and for counteracting PcG-protein-mediated repression, by recruiting the histone methyltransferases ASH1 and TRX to chromatin during development79. The widespread defects observed in patients with CHARGE syndrome suggests that, as is the case in D. melanogaster, CHD7 in humans has a general and non-redundant function in gene transcription and cellular development.

Developmental roles of INO80 complexes

The last family of SWI-like ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling complexes is the INO80 family. These complexes contain INO80 ATPases, which in mammals include INO80 and SWR1 and are characterized by the presence of a conserved split ATPase domain. The INO80 and SWR1 complexes are large multisubunit machines with in vitro nucleosome-remodelling activity, which might contribute to their in vivo roles in transcriptional regulation (see ref. 80 for a review). In the light of recent discoveries, we focus on the developmental functions of the SWR1 complex and a related complex known as the TIP60-p400 complex. In yeast, the Swr1 complex incorporates the variant histone Htz1 (known as H2AZ in mammals) into chromatin by replacing H2A81. In mammals, the genes encoding p400 and SRCAP are closely related homologues of yeast SWR1 and the gene products are found in distinct complexes that have common subunits but potentially different functions82. SRCAP-containing complexes are required for the deposition of H2AZ in vivo83, although the role of these complexes in H2AZ incorporation during development has not been studied. H2AZ is conserved from yeast to mammals: how it functions in different organisms has been controversial, but it is essential for the development of both mice and D. melanogaster. Moreover, a recent genome-wide study by Boyer and colleagues showed that the incorporation of H2AZ during mouse ESC differentiation is essential for proper lineage commitment84. Hence, mammalian SWR1 complexes might be required for H2AZ incorporation during differentiation, a possibility that requires further exploration.

In contrast to SRCAP, p400 is present in a complex together with the mammalian histone acetyltransferase TIP60 and about 16 other subunits, which together carry out functions in transcriptional regulation (particularly in transcriptional activation) and DNA damage repair (see ref. 85 for a review). There are no reports of mice that are null for components of the TIP60-p400 complex, except for TRRAP (homozygous _Trrap_-knockout embryos die at the peri-implantation stage)86. But in a recent RNAi screen for chromatin proteins that are required for mouse ESC self-renewal and pluripotency, Panning and colleagues found that reducing the protein levels of several components of the TIP60-p400 complex, including p400 and TIP60 themselves, resulted in premature differentiation and arrest of mouse ESCs87.

Thus, four ATP-dependent chromatin remodellers — CHD1, NURD complexes, the TIP60-p400 complex and the esBAF complex — seem to have non-redundant roles in pluripotency (Fig. 3), raising the question of whether each has a programmatic, specialized, non-overlapping role in maintaining the ‘landscape’ of pluripotent chromatin.

Lessons from genome-wide studies in ESCs

With the advent of genome-wide approaches for probing gene expression, protein occupancy of DNA sites and nucleosome positioning, a molecular framework for understanding the mechanism that underlies differentiation is emerging. ESCs have become the model for generating a unified map of the network of mechanisms that controls pluripotency, self-renewal and differentiation. Master regulatory transcription factors such as OCT4, SOX2 and Nanog work together with miRNAs and chromatin-regulatory proteins to maintain a transcription circuitry that allows both self-renewal and pluripotent lineage commitment (see ref. 88 for a review). Early genetic studies indicated that BAF complexes have an essential role in pluripotency. More recent screens for chromatin-related proteins that are required for ESC morphology identified components of NURD complexes, the TIP60-p400 complex, CHD1 and, as expected, BAF complexes67,87. BAF complexes are the only ATP-dependent remodellers that have been studied by genome-wide ChIP–Seq analysis, but the functions of TIP60 and CHD1 have been studied by using promoter microarrays, providing global mechanistic insights into the functions of chromatin remodellers32,87 (Fig. 3).

As described earlier, the SWI/SNF-like complex in ESCs, esBAF, has a functionally and biochemically distinct composition that is required for self-renewal and pluripotency28,29. High-resolution genome-wide ChIP–Seq studies showed that the esBAF complex is present at about one-quarter of all promoters in mouse ESCs, with the intensity of binding correlating positively with the expression level of a gene. The targets of the esBAF complex are enriched for genes that are expressed highly and selectively by ESCs, and these overlap extensively with the targets of the transcription factors OCT4, SOX2, Nanog, STAT3 and SMAD1, suggesting functional interplay between the esBAF complex and these pluripotency factors in regulating genes involved in maintaining ‘stemness’30,32. A small number of genes have been studied in ESCs cultured in the prolonged absence of BRG1 or BAF components, and the findings suggest that the esBAF complex maintains ESC fate simply by activating ‘ESC genes’ and repressing genes involved in differentiation29–31. However, a genome-wide analysis carried out after acute depletion of BRG1 points to the esBAF complex having additional, more complex, modes of action32. Reduction of esBAF levels by RNAi-mediated knockdown of the core ATPase Brg1 causes a large number of esBAF targets to be both upregulated and downregulated32. Surprisingly, the upregulated genes include ESC-enriched genes that were already being actively transcribed, suggesting that the esBAF complex refines the expression levels of some ESC genes to keep them within the correct boundaries32. The de-repression of several pluripotency genes, including Oct4 and Nanog, in blastocysts treated with _Brg1_-directed short interfering RNAs30 suggests that this refinement might also occur in vivo. Nonetheless, it is unclear whether the activating or repressing functions of the esBAF complex are more crucial, and it is similarly unclear how these different outcomes of remodelling (activation versus repression) are achieved.

In addition to esBAF, the TIP60-p400 complex is also required for maintaining the self-renewal potential and pluripotency of ESCs87. Using promoter microarrays, p400 was found at more than one-half of all promoters across the genome in mouse ESCs, and the intensity of binding was similarly correlated with the activity of the gene. The complex seems to be recruited to its targets in two ways, directly by the H3K4me3 mark and indirectly by Nanog. Although the TIP60-p400 complex has histone-acetyltransferase activity, which is generally associated with gene activation, this complex functions mainly to repress developmental genes. Hence, TIP60-p400 might deposit H4 acetylation marks that function in an unconventional manner to mediate gene repression.

CHD1 was also recently implicated in pluripotency, through its ability to maintain the open chromatin configuration that is characteristic of mouse ESCs67. Mouse ESCs in which Chd1 has been knocked down using RNAi maintain many of the characteristics of self-renewing ESCs, but they are defective in multilineage differentiation. CHD1 associates with the promoters of active genes and prevents the accumulation of heterochromatin through an unknown mechanism. The conversion of euchromatin to heterochromatin is presumably the cause of the impaired lineage commitment of CHD1-deficient ESCs, because the induction of differentiation transcription programs potentially requires all genes to be generally accessible, including transcriptionally silent developmental genes in ESCs. Although it is not known how CHD1 maintains open chromatin structure, one intriguing possibility is that it is involved in incorporating H3.3 into the chromatin. Because the phenotypes observed in RNAi studies are sometimes unreliable, the implication that CHD1 is involved in pluripotency will need to be confirmed by analysing embryos with null mutations of Chd1.

These studies illustrate the non-overlapping roles and different modes of action of the various ATP-dependent chromatin remodellers in a single cell type, and they show that these remodellers have genetically non-redundant and programmatic roles in pluripotency, perhaps as a result of their coordinated action with the master regulatory transcription factors. Given the crucial roles of chromatin remodellers in pluripotency, it is curious that they were not identified in the search for factors capable of generating induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. The reason for this might be the strict stoichiometry of the complexes, the requirement for which is shown by the observation that overexpression of just one subunit often results in a dominant-negative phenotype.

Perspectives

Before mammalian genomes were sequenced and genome-wide analyses of chromatin function became possible, ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling was thought to be largely a permissive mechanism that operates to allow the binding of general transcription factors. However, the discovery that a large number of non-redundant genes are involved in chromatin remodelling and the ability to carry out more rigorous genetic analyses is enabling the specialized and instructive functions of these complexes to be defined. These functions arise partly from the combinatorial assembly of the complexes. The assembly of complexes from products of gene families suggest that biological specificity is produced in much the same way that letters produce meaning by being assembled into words. But the mechanisms by which these chromatin-remodelling ‘words’ are ‘translated’ into specific biological functions are still unclear, and new ways to probe complex chromatin structure might be needed before we can improve our mechanistic understanding. This is particularly true of BAF complexes, which can regulate transcription from significant distances from promoters and therefore cannot be accurately studied using the available in vitro assays.

The predominant view that chromatin remodellers work to unwind DNA from nucleosomes is derived from elegant but non-physiological in vitro studies. These experiments used cell-free extracts and artificial nucleosome templates that do not recapitulate the three-dimensional complexity of chromatin structure in vivo, such as its organization into heterochromatin or euchromatin and into chromosome territories. The evidence presented in this Review and elsewhere indicates that chromatin remodellers have an intricate role in determining the overall structure and long-range interactions of chromatin. It is also becoming clear that nuclear architecture and gene positioning contribute to gene regulation (see ref. 89 for a review), so new assays must be developed to examine the contribution of chromatin remodellers to the establishment and regulation of higher-order chromatin structure. Techniques such as chromosome conformation capture (3C)90 will be crucial, but other assays, for example using artificially reconstructed three-dimensional chromatin in vitro, will be needed to answer such questions.

A long-standing controversy in the field is the mode by which chromatin-remodelling complexes are targeted to their site of action, which is key to achieving biological specificity. Because most remodellers lack sequence-specific DNA-binding motifs, the predominant view is that they are recruited by way of transient interactions with transcription factors and with DNA-binding proteins that recognize specific DNA sequences. From this viewpoint, in the context of development, remodellers would have an accessory role rather than an instructive role in shaping the transcriptional program and therefore the lineage outcome of a cell. However, there is also ample evidence that, in some cases, remodellers are pretargeted to their sites of action, either by histone modifications or by unknown mechanisms, and that they prepare the target site for binding by transcription factors91. Such examples suggest that remodellers have an instructive role in determining the ability of a particular genome to respond transcriptionally to signals that lead to recruitment of a transcription factor or DNA-binding factor to chromatin. If this is true, the obvious questions are how remodellers recognize their targets and whether this targeting is required for a cell to respond specifically to developmental cues during lineage commitment.

At present it is not known whether chromatin remodelling can transmit the memory of cell fate from one generation to the next. With mounting evidence of the transience and reversibility of chromatin modifications (such as the presence of histone demethylases), the view that chromatin configuration is fixed after being established is giving way to the view that the chromatin landscape can be altered in response to both extrinsic signals and intrinsic signals, such that de-differentiation through nuclear reprogramming is possible. So are remodellers similarly dynamic in their mode of action? That is, are they highly responsive to signalling events? If their program of action is transmitted from one generation to another, then uncovering the mechanisms that direct remodellers back to their appropriate sites of action after each cell division will be crucial for understanding how the specificity and the memory of chromatin-remodelling action are achieved during development.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Yoo, A. Shalizi and J. Ronan for comment and critique throughout the preparation of this article. L.H. is funded by the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (Singapore). G.R.C. is funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Kornberg RD. Chromatin structure: a repeating unit of histones and DNA. Science. 1974;184:868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.184.4139.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suzuki MM, Bird A. DNA methylation landscapes: provocative insights from epigenomics. Nature Rev Genet. 2008;9:465–476. doi: 10.1038/nrg2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, et al. Linking covalent histone modifications to epigenetics: the rigidity and plasticity of the marks. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2004;69:161–169. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2004.69.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cote J, Quinn J, Workman JL, Peterson CL. Stimulation of GAL4 derivative binding to nucleosomal DNA by the yeast SWI/SNF complex. Science. 1994;265:53–60. doi: 10.1126/science.8016655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schones D, Zhao K. Genome-wide approaches to studying chromatin modifications. Nature Rev Genet. 2008;9:179–191. doi: 10.1038/nrg2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu JI, Lessard J, Crabtree GR. Understanding the words of chromatin regulation. Cell. 2009;136:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoo AS, Crabtree GR. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling in neural development. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deuring R, et al. The ISWI chromatin-remodeling protein is required for gene expression and the maintenance of higher order chromatin structure in vivo. Mol Cell. 2000;5:355–365. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrison AJ, Shen X. Chromatin remodelling beyond transcription: the INO80 and SWR1 complexes. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:373–384. doi: 10.1038/nrm2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chi T. Sequential roles of Brg, the ATPase subunit of BAF chromatin remodeling complexes, in thymocyte development. Immunity. 2003;19:169–182. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trotter KW, Archer TK. The BRG1 transcriptional coregulator. Nucl Recept Signal. 2008;6:e004. doi: 10.1621/nrs.06004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stankunas K, et al. Endocardial Brg1 represses ADAMTS1 to maintain the microenvironment for myocardial morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2008;14:298–311. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu J, et al. Regulation of dendritic development by neuron-specific chromatin remodeling complexes. Neuron. 2007;56:94–108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voncken JW, et al. Rnf2 (Ring1b) deficiency causes gastrulation arrest and cell cycle inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2468–2473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0434312100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu J, et al. Bmi1 regulates mitochondrial function and the DNA damage response pathway. Nature. 2009;459:387–392. doi: 10.1038/nature08040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim DA, et al. Chromatin remodelling factor Mll1 is essential for neurogenesis from postnatal neural stem cells. Nature. 2009;458:529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature07726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennison JA, Tamkun JW. Dosage-dependent modifiers of polycomb and antennapedia mutations in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:8136–8140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chalkley GE, et al. The transcriptional coactivator SAYP is a trithorax group signature subunit of the PBAP chromatin remodeling complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2920–2929. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02217-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dingwall AK, et al. The Drosophila snr1 and brm proteins are related to yeast SWI/SNF proteins and are components of a large protein complex. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:777–791. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.7.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong JA, et al. The Drosophila BRM complex facilitates global transcription by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2002;21:5245–5254. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shao Z, et al. Stabilization of chromatin structure by PRC1, a Polycomb complex. Cell. 1999;98:37–46. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80604-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown E, Malakar S, Krebs JE. How many remodelers does it take to make a brain? Diverse and cooperative roles of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes in development. Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;85:444–462. doi: 10.1139/O07-059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang W, et al. Diversity and specialization of mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2117–2130. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.17.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lessard J, et al. An essential switch in subunit composition of a chromatin remodeling complex during neural development. Neuron. 2007;55:201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bultman SJ, et al. Maternal BRG1 regulates zygotic genome activation in the mouse. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1744–1754. doi: 10.1101/gad.1435106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bultman S, et al. A Brg1 null mutation in the mouse reveals functional differences among mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reyes JC, et al. Altered control of cellular proliferation in the absence of mammalian brahma (SNF2α) EMBO J. 1998;17:6979–6991. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.6979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan Z, et al. BAF250B-associated SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex is required to maintain undifferentiated mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1155–1165. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho L, et al. An embryonic stem cell chromatin remodeling complex, esBAF, is essential for embryonic stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5181–5186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812889106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kidder BL, Palmer S, Knott JG. SWI/SNF–Brg1 regulates self-renewal and occupies core pluripotency-related genes in embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;27:317–328. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao X, et al. ES cell pluripotency and germ-layer formation require the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling component BAF250a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6656–6661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801802105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ho L, et al. An embryonic stem cell chromatin remodeling complex, esBAF, is an essential component of the core pluripotency transcriptional network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5187–5191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812888106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansis C, Barreto G, Maltry N, Niehrs C. Nuclear reprogramming of human somatic cells by Xenopus egg extract requires BRG1. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1475–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klochendler-Yeivin A, et al. The murine SNF5/INI1 chromatin remodeling factor is essential for embryonic development and tumor suppression. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:500–506. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim JK, et al. Srg3, a mouse homolog of yeast SWI3, is essential for early embryogenesis and involved in brain development. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7787–7795. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.22.7787-7795.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaniel C, et al. Smarcc1/Baf155 couples self-renewal gene repression with changes in chromatin structure in mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009 September 25; doi: 10.1002/stem.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parrish JZ, Kim MD, Jan LY, Jan YN. Genome-wide analyses identify transcription factors required for proper morphogenesis of Drosophila sensory neuron dendrites. Genes Dev. 2006;20:820–835. doi: 10.1101/gad.1391006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoo AS, Staahl BT, Chen L, Crabtree GR. MicroRNA-mediated switching of chromatin-remodelling complexes in neural development. Nature. 2009;460:642–646. doi: 10.1038/nature08139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lange M, et al. Regulation of muscle development by DPF3, a novel histone acetylation and methylation reader of the BAF chromatin remodeling complex. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2370–2384. doi: 10.1101/gad.471408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lickert H, et al. Baf60c is essential for function of BAF chromatin remodelling complexes in heart development. Nature. 2004;432:107–112. doi: 10.1038/nature03071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takeuchi JK, et al. Baf60c is a nuclear Notch signaling component required for the establishment of left–right asymmetry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:846–851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608118104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takeuchi JK, Bruneau BG. Directed transdifferentiation of mouse mesoderm to heart tissue by defined factors. Nature. 2009;459:708–711. doi: 10.1038/nature08039. This study showed that BAF60C, together with two cardiogenic transcription factors (GATA4 and TBX5), is sufficient to direct heart formation in non-cardiogenic tissues in developing embyros, demonstrating that chromatin remodelling by specific BAF complexes can be both necessary and sufficient for specific fate induction. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Z, et al. Polybromo protein BAF180 functions in mammalian cardiac chamber maturation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3106–3116. doi: 10.1101/gad.1238104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang X, Gao X, Diaz-Trelles R, Ruiz-Lozano P, Wang Z. Coronary development is regulated by ATP-dependent SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling component BAF180. Dev Biol. 2008;319:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sawada S, Scarborough JD, Killeen N, Littman DR. A lineage-specific transcriptional silencer regulates CD4 gene expression during T lymphocyte development. Cell. 1994;77:917–929. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wan M, et al. Molecular basis of CD4 repression by the Swi/Snf-like BAF chromatin remodeling complex. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:580–588. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chi TH, et al. Reciprocal regulation of CD4/CD8 expression by SWI/SNF-like BAF complexes. Nature. 2002;418:195–199. doi: 10.1038/nature00876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cosma MP, Tanaka T, Nasmyth K. Ordered recruitment of transcription and chromatin remodeling factors to a cell cycle-and developmentally regulated promoter. Cell. 1999;97:299–311. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80740-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khavari PA, Peterson CL, Tamkun JW, Mendel DB, Crabtree GR. BRG1 contains a conserved domain of the SWI2/SNF2 family necessary for normal mitotic growth and transcription. Nature. 1993;366:170–174. doi: 10.1038/366170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de la Serna IL, Carlson KA, Imbalzano AN. Mammalian SWI/SNF complexes promote MyoD-mediated muscle differentiation. Nature Genet. 2001;27:187–190. doi: 10.1038/84826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dirscherl SS, Krebs JE. Functional diversity of ISWI complexes. Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;82:482–489. doi: 10.1139/o04-044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corona DF, et al. ISWI regulates higher-order chromatin structure and histone H1 assembly in vivo. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siriaco G, Deuring R, Chioda M, Becker PB, Tamkun JW. Drosophila ISWI regulates the association of histone H1 with interphase chromosomes in vivo. Genetics. 2009;182:661–669. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.102053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xi R, Xie T. Stem cell self-renewal controlled by chromatin remodeling factors. Science. 2005;310:1487–1489. doi: 10.1126/science.1120140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Badenhorst P, Voas M, Rebay I, Wu C. Biological functions of the ISWI chromatin remodeling complex NURF. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3186–3198. doi: 10.1101/gad.1032202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Landry J, et al. Essential role of chromatin remodeling protein Bptf in early mouse embryos and embryonic stem cells. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Banting GS, et al. CECR2, a protein involved in neurulation, forms a novel chromatin remodeling complex with SNF2L. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:513–524. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stopka T, Skoultchi AI. The, ISWI ATPase Snf2h is required for early mouse development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14097–14102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336105100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Francke U. Williams–Beuren syndrome: genes and mechanisms. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1947–1954. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.10.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoshimura K, et al. Distinct function of 2 chromatin remodeling complexes that share a common subunit, Williams syndrome transcription factor (WSTF) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9280–9285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901184106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 61.Hall JA, Georgel PT. CHD proteins: a diverse family with strong ties. Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;85:463–476. doi: 10.1139/O07-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flanagan JF, et al. Double chromodomains cooperate to recognize the methylated histone H3 tail. Nature. 2005;438:1181–1185. doi: 10.1038/nature04290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sims RJ, et al. Recognition of trimethylated histone H3 lysine 4 facilitates the recruitment of transcription postinitiation factors and pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2007;28:665–676. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McDaniel IE, Lee JM, Berger MS, Hanagami CK, Armstrong JA. Investigations of CHD1 function in transcription and development of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2008;178:583–587. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.079038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Konev AY, et al. CHD1 motor protein is required for deposition of histone variant H3.3 into chromatin in vivo. Science. 2007;317:1087–1090. doi: 10.1126/science.1145339. This was the first study to show the ability of CHD1 to incorporate H3.3 into paternal chromatin, rendering it competent for post-fertilization mitosis, possibly explaining the sterility of CHD1-deficient D. melanogaster. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hödl M, Basler K. Transcription in the absence of histone H3.3. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1221–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gaspar-Maia A, et al. Chd1 regulates open chromatin and pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2009;460:802–803. doi: 10.1038/nature08212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Y, LeRoy G, Seelig HP, Lane WS, Reinberg D. The dermatomyositis-specific autoantigen Mi2 is a component of a complex containing histone deacetylase and nucleosome remodeling activities. Cell. 1998;95:279–289. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bowen NJ, Fujita N, Kajita M, Wade PA. Mi-2/NuRD: multiple complexes for many purposes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1677:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Feng Q, Zhang Y. The MeCP1 complex represses transcription through preferential binding, remodeling, and deacetylating methylated nucleosomes. Genes Dev. 2001;15:827–832. doi: 10.1101/gad.876201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Denslow SA, Wade PA. The human Mi-2/NuRD complex and gene regulation. Oncogene. 2007;26:5433–5438. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kaji K, Nichols J, Hendrich B. Mbd3, a component of the NuRD co-repressor complex, is required for development of pluripotent cells. Development. 2007;134:1123–1132. doi: 10.1242/dev.02802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kaji K, et al. The NuRD component Mbd3 is required for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature Cell Biol. 2006;8:285–292. doi: 10.1038/ncb1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Williams CJ, et al. The chromatin remodeler Mi-2β is required for CD4 expression and T cell development. Immunity. 2004;20:719–733. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]