LMP1 association with CD63 in endosomes and secretion via exosomes limits constitutive NF-κB activation (original) (raw)

Abstract

The ubiquitous Epstein Barr virus (EBV) exploits human B-cell development to establish a persistent infection in ∼90% of the world population. Constitutive activation of NF-κB by the viral oncogene latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) has an important role in persistence, but is a risk factor for EBV-associated lymphomas. Here, we demonstrate that endogenous LMP1 escapes degradation upon accumulation within intraluminal vesicles of multivesicular endosomes and secretion via exosomes. LMP1 associates and traffics with the intracellular tetraspanin CD63 into vesicles that lack MHC II and sustain low cholesterol levels, even in ‘cholesterol-trapping’ conditions. The lipid-raft anchoring sequence FWLY, nor ubiquitylation of the N-terminus, controls LMP1 sorting into exosomes. Rather, C-terminal modifications that retain LMP1 in Golgi compartments preclude assembly within CD63-enriched domains and/or exosomal discharge leading to NF-κB overstimulation. Interference through shRNAs further proved the antagonizing role of CD63 in LMP1-mediated signalling. Thus, LMP1 exploits CD63-enriched microdomains to restrain downstream NF-κB activation by promoting trafficking in the endosomal-exosomal pathway. CD63 is thus a critical mediator of LMP1 function in- and outside-infected (tumour) cells.

Keywords: CD63, endosomes, exosomes, LMP1, NF-κB signalling

Introduction

Epstein Barr virus (EBV) is a lymphotrophic γ-herpesvirus that encodes for the latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1), a pleiotropic viral oncoprotein expressed in many EBV-associated tumours (Thorley-Lawson and Gross, 2004). The assumed biological function of LMP1 in healthy carriers is to mimic downstream signalling of the human TNF receptor family member CD40 in EBV-infected B cells passing the germinal centre (GC). Timely expression of LMP1 in concordance with other latent gene products during the restricted latency II (default) and latency III (growth program) stages of infected cells is suspected to provide essential survival signal(s). Ultimately, the surviving infected cells access the long-lived peripheral memory B-cell compartment, widely considered as the main site of EBV persistence (Thorley-Lawson, 2001). Recent in situ studies unequivocally confirmed that EBV-infected tonsillar B cells within GCs of healthy individuals contain LMP1 mRNA (Roughan and Thorley-Lawson, 2009; Roughan et al, 2010) and protein (Hudnall et al, 2005).

LMP1 has classic transforming activity in rodent fibroblasts (Wang et al, 1985) and is essential for efficient EBV-mediated transformation of naive B cells (Dirmeier et al, 2003) by inducing constitutive NF-κB activation upon infection that drives the proliferation of latency type III lymphoblastoid B cell line (LCL) cells (Cahir-McFarland et al, 2000). In addition, LMP1 drives the growth of infected lymphoma cells (Liebowitz, 1998; Guasparri et al, 2008). The oncogenic and growth-promoting properties of LMP1 are directly associated with its ability to signal without a ligand (Gires et al, 1997). LMP1 contains six membrane-spanning domains that mediate trafficking and intermolecular (self)aggregation that initiates downstream signalling via the recruitment of TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) molecules (Yasui et al, 2004; Soni et al, 2006; Lee and Sugden, 2007). Studies in transgenic mice provided compelling evidence that without the control of an external ligand, uncontrolled CD40 signalling causes lymphomagenesis (Thornburg et al, 2006; Hatzivassiliou et al, 2007; Homig-Holzel et al, 2008). Likewise in humans, mutations that result in constitutive activation of NF-κB define a clinically distinct subgroup of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (Davis et al, 2001, 2010). Thus, NF-κB signalling through LMP1 expression during normal viral latency in healthy developing B cells must be tightly controlled to prevent malignant conversion.

A recurring drawback in studying the biological function of EBV-encoded genes such as LMP1 is that naturally infected B cells are extremely rare and difficult to isolate. Furthermore, observations made in cell lines in vitro seldom accurately reflect the in vivo situation. Despite these difficulties, comprehensive in situ studies confirmed that the LMP1 protein and transcripts are expressed in distinct subsets of GC B cells in healthy carriers (Hudnall et al, 2005; Roughan and Thorley-Lawson, 2009; Roughan et al, 2010). In contrast, in EBV-associated lymphomas such as Hodgkin's disease, AIDS-related lymphomas and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease, LMP1 is always expressed in proliferating infected cells and the protein is easily detectable (Middeldorp and Pegtel, 2008). While in vitro LMP1 expression is controlled by the EBNA2 transactivator gene, in vivo studies reveal LMP1 protein expression in absence of EBNA2 (default program) that appears relevant for normal EBV persistence in B cells (Babcock and Thorley-Lawson, 2000; Roughan and Thorley-Lawson, 2009). LMP1 expression thus seems tightly regulated at the transcriptional level in vivo, but little remains known about its fate after translation. Considering the potential oncogenic consequence of LMP1 expression, a detailed understanding in LMP1 regulation at the protein level is crucial. It has been suggested that cellular protein levels of LMP1 are somehow ‘balanced’ to sustain NF-κB-dependent growth and activation of anti-apoptotic pathways in the infected B cells, while simultaneously preventing potential NF-κB overstimulation and transformation into lymphomas (Lee and Sugden, 2008a, 2008b; Brooks et al, 2009). Rapid turnover was proposed to regulate LMP1 signalling activity early on (Mann and Thorley-Lawson, 1987; Martin and Sugden, 1991), yet the exact mechanism(s) that regulate LMP1 protein levels to achieve a balance in constitutive NF-κB signalling remain poorly understood.

Here, we considered an alternative mechanism for regulating LMP1 protein levels apart from the proteasomal and lysosomal degradatory pathways. Independent observations indicate that full-length LMP1 protein is secreted via microvesicles suggesting escape from degradation (Dukers et al, 2000; Flanagan et al, 2003; Keryer-Bibens et al, 2006; Ceccarelli et al, 2007; Houali et al, 2007; Meckes et al, 2010). Similarly, functional MHC II molecules are secreted via endocytic vesicles named exosomes that are enriched in proteins and lipids (cholesterol), consistent with both tetraspanin-enriched protein-based microdomains (TEMs) and/or conventional lipid rafts (Raposo et al, 1996; Wubbolts et al, 1996; Muntasell et al, 2007; Arita et al, 2008). Our data suggest a diversification in endosomal compartments in EBV-infected B cells between vesicles that are enriched in MHC II or LMP1. LMP1 is known to activate NF-kB constitutively from intracellular compartments that sustain lipid rafts presumably the Golgi (Higuchi et al, 2001; Lam and Sugden, 2003; Yasui et al, 2004; Liu et al, 2006). We demonstrate here that upon Golgi exit, LMP1 assembles within protein-based tetraspanin subdomains (TEMs) for trafficking and sorting into endosomes leading to its secretion via exosomes and reduced NF-κB activation.

Results

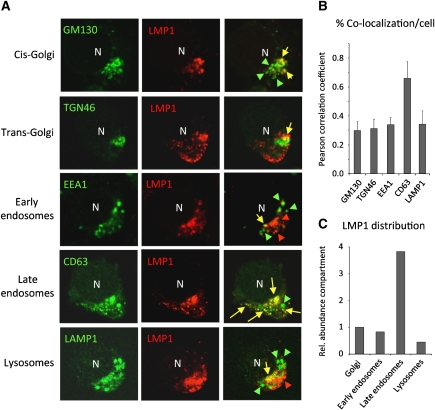

LMP1 in EBV-infected LCL cells is enriched in multivesicular endosomes

To determine the subcellular localization of endogenous LMP1 protein in LCLs, we performed double fluorescent confocal analysis (CLSM) using established markers to identify distinct subcellular compartments and quantified the percentage of cells in which we observed co-localization. For accurate comparison, we selected individual cells expressing ‘intermediate’ levels of LMP1 (Figure 1A) and determined the percentage of co-localization averages of multiple individual cells (Pearson correlation coefficient, PCC). A small proportion endogenous LMP1 protein is present in Golgi compartments (cis or trans) or early endosomes (PCC<0.30); however, we detected substantial co-localization with the late endosomal protein Lamp3/CD63 (CD63) (PCC>0.65) in defined peripheral vesicles (Supplementary Video SV1), yet LAMP1-positive lysosomes contained little LMP1 (PCC<0.3) (Figure 1B). Besides a high degree of co-localization with intracellular CD63, co-localization was observed in much larger part of the cell population compared with other markers such as the lysosomal marker LAMP1 (Supplementary Figure S1). When we multiply the calculated average percent co-localization/cell with the proportion of cells in which we detected co-localization in a population (Supplementary Figure S1), the proportion of LMP1 in endosomes is more pronounced (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Intracellular EBV-encoded LMP1 localizes to late endosomes. CLSM analysis on cytospins of EBV-infected LCLs showing the subcellular localization of endogenous LMP1 in combination with subcellular markers (A). Shown are representative images of individual LCL cells with a polarized phenotype and ‘intermediate’ levels of LMP1 co-stained with GM130 (cis-Golgi; 34%), TGN46 (trans-Golgi; 30%), EEA1 (early endosomes; 24%), CD63/Lamp3 (late endosomes; 92%) or LAMP1 (lysosomes; 13%). Percentages represent the proportion of cells with co-localization as shown in Supplementary Figure S1. (B) Pearson correlation coefficients (PCCs) were calculated from multiple individual cells expressing ‘intermediate’ levels LMP1 and the indicated subcellular markers (error bars represent s.d.; _n_>5). (C) The percentage co-localization calculated in (B) were multiplied by the proportion of cells (_n_>50) that display co-localization in overview images (Supplementary Figure S1) (GM130 represents Golgi=1).

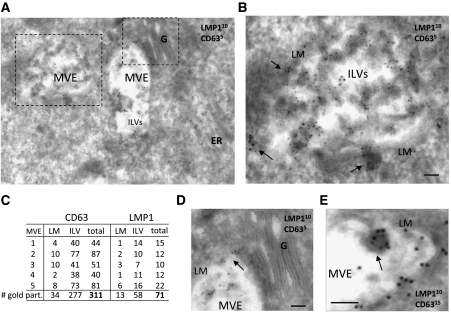

To confirm that intracellular LMP1 localizes to late endosomal membranes, we performed electron microscopy (EM) analysis using double immunogold labelling against the LMP1 protein and CD63 on ultrathin cryosections of LCL. Figure 2A shows CD63 (5 nm gold particles) localization and enrichment in the intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within multivesicular bodies/endosomes (MVEs). Higher magnification shows that LMP1 protein (10 nm gold particles) and CD63 are both enriched in the ILVs of MVEs (Figure 2B). However, we observed that not all MVEs in individual cells hold LMP1 and/or CD63 (Supplementary Figure S2). Quantification of MVEs from individual LCL cells that contain LMP1, indicated an approximately five-fold enrichment compared with the limiting membrane (LM) (Figure 2C). We did not detect abundant LMP1 at or near the plasma membrane or in Golgi structures, but occasionally observed LMP1 at endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membranes and ‘intermediate lysosomal’ structures (Mobius et al, 2003; Supplementary Figure S2). We also observed to what appears a budding event of a subdomain from the LM containing both CD63 and LMP1 (Figure 2D). In conclusion, confocal and EM imaging indicate that LMP1 protein in LCL cells is abundantly associated with late endosomal membranes. The EM analysis confirms that LMP1 is enriched within ILVs of MVEs, generally accepted as the precursors of exosomes.

Figure 2.

Endogenous LMP1 accumulates in multivesicular endosomes of LCL. LCL cells were cryosectioned and the ultrathin sections were stained with primary antibodies directed against LMP1 (OT21A) and CD63 (NKI-C3) using Protein-A gold (PAG) with the indicated sizes. (A) EM image of an LCL cell with multiple late endosomes/multivesicular endosomes (MVEs). Golgi (G), endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) are shown. (B) Magnification of (A) showing the limiting membrane (LM) of an MVE holding ILVs that incorporated LMP1 and CD63. Arrows indicate clusters of LMP1 and CD63 near MVEs. (C) Five MVEs (from multiple cells) were quantitated for CD63 and LMP1 presence at LM or ILVs. ILVs contain several fold more gold particles indicating enrichment of both proteins in the ILVs compared with the LM. (D) Magnification of (A), representing a Golgi stack that is devoid of CD63 and LMP1 gold particles relative to MVE-associated membranes. (E) Budding event of the LM from a MVE with LMP1 (10 nm) and CD63 (15 nm) (bar in images represents 100 nm).

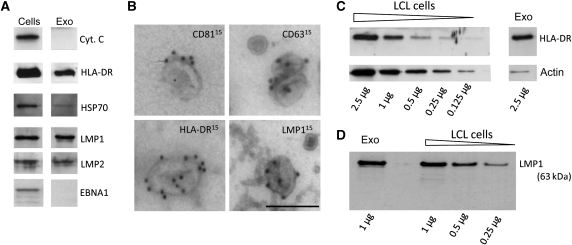

LMP1 is secreted from EBV-infected LCL cells via exosomes

Virally encoded proteins can be secreted from infected cells via microvesicles such as exosomes, which has been demonstrated for the HIV Nef protein, EBV LMPs and the HSV glycoprotein B (Flanagan et al, 2003; Ikeda and Longnecker, 2007; Lenassi et al, 2010; Temme et al, 2010). To establish that LMP1 is secreted through endocytic exosomes, we purified the exosome population secreted by EBV-containing LCL as previously described (Pegtel et al, 2010). Western blotting on the exosomal extracts confirmed the presence of exosomal proteins enriched in LCL exosomes, such as HLA-DR and HSP70. The EBV-encoded membrane proteins LMP1 and LMP2 were also abundantly present, but the mitochondrial protein cytochrome C and the nuclear EBV antigen EBNA1 were not detected (Figure 3A). Immunogold labelling on purified exosomes suggests that the tetraspanins CD63 and CD81 as well as HLA-DR were located at the surface of individual 100 nm sized exosomes (Figure 3B), and LMP1 appears to have a similar membranous localization. We conclude that EBV-encoded LMP1 is selectively sorted into ILVs of MVEs and preferentially secreted via bona fide exosomes during culture.

Figure 3.

Full-length LMP1 is secreted via endosomal-derived vesicles called exosomes. (A) LCL cells and purified exosome preparations were lysed and fractions were loaded and run on the same gel for a direct comparison by western analysis. Proteins analysed included the EBV-encoded proteins LMP1, LMP2 and EBNA1 as well as the cellular exosomal proteins HLA-DR and HSP70 and the mitochondrial protein Cytochrome C. The nuclear viral protein EBNA1 and the cytoplasmic cellular protein Cytochrome C were not detected in the exosomal lysates. This figure was assembled from multiple blots. (B) Immunogold labelling on purified exosomes for the tetraspanins CD81 and CD63, HLA-DR and LMP1 (bar represents 100 nm). (C) Semi-quantitative western analysis to HLA-DR and actin abundance in cellular lysates compared with exosomal lysates. Decreasing amounts of total LCL lysate (2.5–0.125 μg) were measured for HLA-DR and actin abundance and compared with the abundance of these proteins in 2.5 μg of exosomal lysate (exo). Lanes shown represent one gel. (D) As in (C), but here the abundance of LMP1 in 1 μg of exosome-preparation lysate were compared with decreasing amounts of LCL cell lysates (1–0.25 μg).

It was estimated by Muntasell et al (2007) that as much as ∼50% of the surface MHC class II molecule HLA-DR, escapes degradation and that ∼12% of newly synthesized HLA-DR is secreted through exosomes within 24 h. Using a semi-quantitative western analysis, we show that the abundant cellular cytoskeleton protein actin is markedly underrepresented in exosomal fractions from LCL collected over a 24-h period, compared with HLA-DR (Figure 3C). In a similar experiment, we determined that LMP1 was equally enriched in LCL exosomes (Figure 3D), thus further confirming our initial observations by immuno-EM indicating that LMP1 is selectively sorted into ILVs (Figure 2).

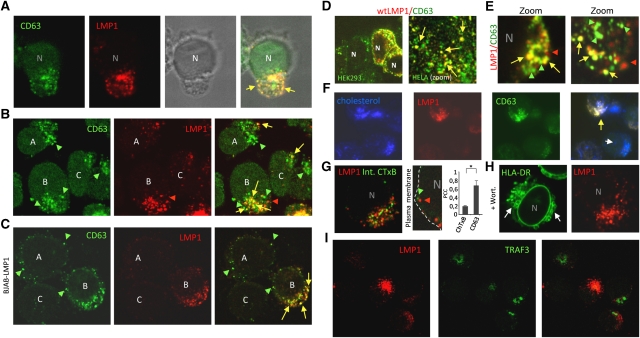

LMP1 associates with CD63 in late endosomes that lack HLA-DR

LCL cells display a polarized morphology with the bulk of intracellular LMP1 and CD63 present in distinctive vesicles located at one side of the nucleus (Figure 4A). Despite their presumed clonal origin, endogenous LMP1 is heterogeneously expressed comparing LCL cells individually. Endogenous (intra)cellular LMP1 co-localized abundantly with CD63, although LMP1-negative vesicles and cells are observed (Figure 4B). To investigate whether the distribution of LMP1 and CD63 was limited to the context of EBV infection, we expressed LMP1 in EBV-negative BJAB cells with an inducible LMP1 expression construct. At 0 h, endogenous CD63 was present in vesicles that surrounded the nucleus, but upon LMP1 induction CD63 was redistributed (Supplementary Figure S3) to LMP1-rich vesicles in a more polarized manner (Figure 4C). Exogenous LMP1 in HEK293 and HELA cells also localized and redistributed endogenous CD63 into peripheral vesicles (Figure 4D). When we treated LCL with chloroquine to enlarge MVEs enhancing resolution (Zwart et al, 2005), we observed a striking LMP1 co-localization with CD63 in defined microdomains and peripheral vesicles (Figure 4E). Together, these findings suggest that LMP1 shares endosomal trafficking with CD63.

Figure 4.

Endogenous LMP1 associates with CD63 in peripheral vesicles and microdomains. (A–E) CLSM analysis showing intracellular distribution of LMP1 (red) and CD63 (green) in multiple cell types. (A) LCL combined with transmission imaging highlights the vesicles in a polarized phenotype. (B) LCLs representing the different expression levels of LMP1. (C) LMP1-inducible cell line (BJAB-LMP1) 24 h after induction. (D) wtLMP1 transfected HEK293 and HELA cells, stained for LMP1 (red) and CD63 (green) and LCLs that were treated with 100 μM chloroquine for 3 h (E). (F) Immunofluorescence imaging of LCL cytospins with LMP1 (red) and CD63 (green) and filipin (blue) indicating cholesterol. (G) CLSM analysis showing a representative LCL cell with intracellular LMP1 (red) distribution and internalized CTxB-FITC (green) representative of gangliosine-1-rich lipid microdomains. LMP1 localization correlated with CD63, not CTxB. (Student's _t_-test, *P<0.05; error bars represent s.d.; _n_>5). (H) LCLs treated with Wortmannin were co-stained on cytospins for LMP1 and HLA-DR. CLSM shows the redistribution of HLA-DR into ‘ring-like’ structures due to enlarged vesicles (white arrows). This effect was not observed for LMP1. (I) CLSM analysis showing intracellular distribution of LMP1 (red) and TRAF3 (green) in LCL cells.

Surface MHC II is internalized via endocytosis in part via lipid domains (rafts) supporting the sorting of these molecules into exosomes (De et al, 2003; Wubbolts et al, 2003; Muntasell et al, 2007; Buschow et al, 2009). However, we observed that endogenous LMP1/CD63-rich vesicles reside in what appears cholesterol ‘low’ compartments as indicated by filipin staining (Figure 4F). To investigate the possibility that LMP1, is internalized (rapidly) from the surface via lipid rafts like HLA-DR, we incubated LCL with exogenous CTxB-FITC that binds strongly to gangliosine-1 (GM1), an established constituent of lipid rafts. However, Figure 4G shows that, in contrast to CD63, the large majority of intracellular LMP1 does not co-localize with internalized CTxB-FITC (Pearson coefficient 0.3 versus 0.7, P<0.05 in a Student's _t_-test). Although both HLA-DR and LMP1 are abundantly secreted through LCL exosomes (Figure 3), confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) further indicated that little LMP1 co-localizes with HLA-DR (Supplementary Figure S1) suggesting diversification in late endosomal compartments. Consistent with this, Wortmannin-treated LCL (to inhibit VPS34-mediated formation of ILVs) showed characteristic enlargement of HLA-DR containing vesicles (Fernandez-Borja et al, 1999), while this was never seen for LMP1 (Figure 4H). To gain insight whether peripheral vesicles contain active LMP1 complexes, we performed CLSM analysis for LMP1 and TRAF3 but observed very distinct staining patterns (Figure 4I). In conclusion, LMP1 and CD63 co-localize in membranous intracellular subdomains of late endosomes (LEs) that are distinct from GM1-enriched rafts and seem to lack MHC II or the signalling intermediate TRAF3.

LMP1 interacts with CD63 and induces shared secretion through exosomes

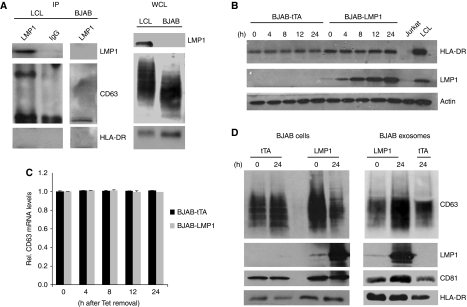

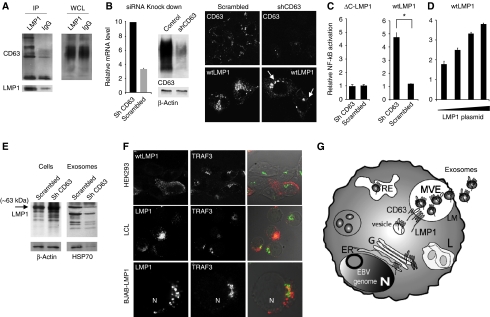

To study whether CD63 associated with LMP1 in LCL, we performed immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments with the endogenous LMP1 protein. We first confirmed the interaction between endogenous LMP1 and TRAF1 by co-IP (data not shown). CD63 is heavily glycosylated and in non-reducing conditions displays a broad range between 30 and 60 kDa by western analysis because much of size is attributed to N-glycosylation (Pols and Klumperman, 2009). LMP1 co-immunoprecipitated a specific band of ∼40–50 kDa that corresponds to endogenous CD63 as defined by western analysis using a CD63-specific antibody (Figure 5A). This band was absent in an equal amount of IP lysate using an IgG control antibody and was not observed using the same antibody with an IP lysate of EBV-negative (BJAB) cells. Moreover, endogenous LMP1 did not form complexes with HLA-DR (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

LMP1 binds to CD63 in B cells stimulating secretion via exosomes. (A) Endogenous LMP1 associates with CD63. LMP1 and IgG control immunoprecipitates from equal amounts of 1% Triton X-100 LCL lysates were examined by western blotting for LMP1, CD63 and HLA-DR. CD63 is heavily glycosylated displaying a range of bands between 30 and 60 kDa. (B) EBV-negative BJAB cells carrying a tetracyclin-inducible (TET-Off) LMP1 or tTA (control) expression constructs. LMP1 is induced by TET-removal from the media. Cell lysates at 0, 4, 8, 12 and 24 h after tet-removal were subjected to western blotting for HLA-DR, LMP1 and actin using equal amounts of lysate. Jurkat and LCL were used as controls. (C) Semi-quantitative RT–PCR for relative CD63 mRNA levels, performed on RNA isolated after 0, 4, 8, 12 and 24 h of LMP1 induction in BJABs (error bars represent s.d., _n_=3) (D) LMP1-inducible BJABs were cultured for 24 h with or without tetracycline. Equal amounts of cell lysates were subjected to western blotting. Simultaneously, exosomes were purified from the medium by ultra-centrifugation and equal proportion of cell- and exosomal lysates were subjected to western blotting for CD63, CD81, and LMP1 and HLA-DR.

To gain insight into the kinetics of LMP1 secretion via exosomes, we studied LMP1 release though exosomes in the BJAB-LMP1 cells. Upon removal of tetracycline, LMP1 protein levels increased steadily over time, reaching endogenous LCL protein levels after ∼24 h (Figure 5B). CLSM analysis for endogenous CD63 suggested that LMP1 expression caused a redistribution and aggregation of CD63 (Supplementary Figure S3); however, semi-quantitative RT–PCR analysis showed that CD63 transcript levels remained unaltered (Figure 5C). We conjectured that total CD63 protein levels may be increased by LMP1 induction, but unexpectedly, we detected a decrease in cellular CD63 protein levels. When we analysed equal proportions of exosomal fractions of non-induced and 24 h induced BJAB cells, we detected abundant full-length (63 kDa) LMP1 and a significantly increased amount of CD63 in the exosomal fraction (Figure 5D), which was not seen for HLA-DR or CD81. These findings can be explained by induction of exosome secretion or through more efficient trafficking/sorting of CD63. It is attractive to speculate that the heterogeneity of LMP1 levels in clonal LCLs maybe due to differences in sorting efficiency. Although we cannot discriminate between these two possibilities, increased exosomal secretion of CD63 argues against a third possibility that CD63 upon LMP1 expression becomes less stable. Taken together, our results suggest that LMP1 assembles CD63-enriched microdomains and are both sorted into ILVs of MVEs for secretion through exosomes. Heterogeneity of LMP1 levels between individual cells in LCL cultures may be further explained by differences in LMP1 synthesis and secretion rate relative to the cell-cycle stage (work in progress).

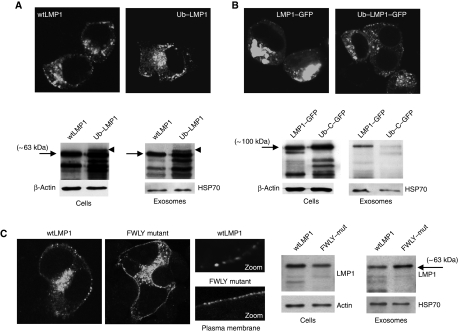

Ubiquitylation nor lipid-raft targeting controls LMP1 sorting into exosomes

The endosomal-lysosomal sorting pathway for membrane proteins requires ubiquitylation of the cytoplasmic domain and recognition by the evolutionary conserved endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) that regulates ILV biogenesis (Piper and Luzio, 2007). HEK293 cells express functional ESCRT complexes that mediate incorporation of ubiquitylated cargo proteins into ILVs of MVEs (Gauvreau et al, 2009). To investigate whether ubiquitin has a role in the selective incorporation of LMP1 into exosomes, we expressed a stable ‘non-cleavable’ mono-ubiquitylated (Ub)–LMP1 fusion protein and analysed incorporation into exosomes. Confocal analysis shows that Ub–LMP1 and wild-type LMP1 (wtLMP1) have a similar distribution in HEK293 cells with some small aggregates in/near the plasma membrane, although the major pool of LMP1 is intracellular (Figure 6A). Western analysis confirmed that LMP1 is secreted via exosomes as a 63-kDa protein. Forced mono-ubiquitylation at the N-terminus was associated with additional and more intense LMP1 breakdown products, in accordance with previous findings (Aviel et al, 2000; Tellam et al, 2003). However, the unprocessed Ub–LMP1 fusion protein, was not preferentially sorted and secreted via exosomes, consistent with ECSRT-independent loading of LMP1 (Stuffers et al, 2009).

Figure 6.

Effect of ubiquitylation and FWLY on LMP1 sorting into exosomes. (A) HEK293 cells seeded on coverslips were transfected with wtLMP1 or LMP1 with a covalently attached ubiquitin at the N-terminus (Ub–LMP1) in the same vector (pcDNA3) and stained for LMP1 24 h after transfection. In parallel, equal amounts of HEK293 cells were transfected with wtLMP1 construct or Ub–LMP1. After 48 h, exosomes were purified from the medium and equal proportions of the cellular and exosomal lysates were analysed by western blotting for the presence of LMP1, actin and HSP70. (B) As in (A), with HEK293 cells transfected with C-terminal GFP-tagged LMP1 (LMP1–GFP) or Ub–LMP1 with a C-terminal GFP-tag (Ub–LMP1–GFP) (both in pEGFP) and analysed for GFP fluorescence by CLSM analysis 24 h after transfection. In parallel, HEK293 cells were transfected with LMP1–GFP or Ub–LMP1–GFP and after 48 h, exosomes were purified from the medium. Both cell and the exosome lysates were loaded in equal amounts on the gel and subjected to western blotting analysis for LMP1 using actin and HSP70 as loading control respectively. (C) As in (A), with HEK293 cells were transfected with LMP1 containing a mutated, non-functional FWLY domain (FWLY mutant) or with a wtLMP1 control construct with non-essential mutations in TM2 (both in pSG5 plasmid). Cells were fixed and stained for LMP1 localization 24 h after transfection and analysed with CLSM analysis. In parallel, HEK293 cells were transfected with wtLMP1 control or the FWLY mutant. After 48 h of transfection, exosomes were purified from the medium and exosome lysates and cell lysates were analysed by western blotting for LMP1 and actin, or HSP70 (image representative for (A) 92 and 95%, (B) 81 and 94%, (C) 92 and 89%, respectively).

We observed that GFP tagging to LMP1 disturbs trafficking, resulting in accumulation at perinuclear regions (Figure 6B) in a major proportion (∼80%) of the LMP1-transfected cells. LMP1–GFP did not redistribute or co-localize with CD63 (Supplementary Figure S4B) and was inefficiently sorted into exosomes. Because HSP70 secretion was unchanged, we reasoned that only the trafficking and loading of LMP1 into exosomes was altered not exosomal production and/or secretion itself. Forced ubiquitylation did not reverse the intracellular retention of LMP1–GFP, perhaps because this form is less stable since more intense breakdown products were observed (Figure 6B). Overall, we conclude that the sorting and secretion of wtLMP1 into exosomes is linked to co-aggregation and intracellular trafficking with CD63. C-terminal modification by GFP fusion impairs this function, leading to intracellular retention that precludes the incorporation into exosomes. Although we cannot formally rule out the possibility that wtLMP1 is ubiquitylated and at the final stage de-ubiquitylated, before sorting into exosomes, an ‘ubiquitin-independent’ sorting pathway seems more likely.

Endosomal membranes are not uniform, but can contain lateral lipid subdomains enriched in ceramide (Trajkovic et al, 2008) or cholesterol, that may favour the formation of ILVs (Piper and Katzmann, 2007). Selective MHC II sorting into B-cell exosomes may occur through association within detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs) or lipid rafts enriched in cholesterol and proteins such as GM1 and the tetraspanins CD81 and CD82 (Escola et al, 1998; De et al, 2003; Wubbolts et al, 2003). We investigated the possibility that the hydrophobic sequence FWLY within the first transmembrane region of LMP1 (TM1) controls its sorting into exosomes as FWLY has been shown to mediate the association of LMP1 within DRMs (Yasui et al, 2004; Soni et al, 2006; Lee and Sugden, 2007). CLSM shows that LMP1 with a disrupted FWLY domain by four alanine substitutions (FWLY mutant) forms more, but smaller aggregates in the plasma membrane compared with wtLMP1 and a control construct with non-functional point mutations in the TM2 domain (Figure 6C). Intracellular distribution was similar to wtLMP1 and co-localization with endogenous CD63 was retained (Supplementary Figure S4). Moreover, LMP1-FWLY was detectable by western blot analysis in exosomes. In fact, in a direct comparison, disruption of FWLY may even support secretion of LMP1 via exosomes to some extent (Figure 6C). Combined, these studies suggest that LMP1 sorting into HEK293 exosomes is neither mediated by the lipid-raft anchoring domain FWLY nor by ubiquitylation of the N-terminus.

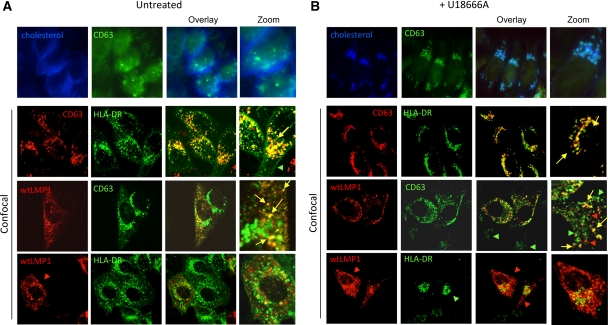

LMP1 recruits CD63 into vesicles that sustain low cholesterol levels

Cholesterol is required for the integrity of lipid rafts and abundant in Golgi and some endosomal compartments. We investigated the influence of impaired endosomal cholesterol trafficking on LMP1, HLA-DR and CD63 distribution in HELA cells stably transduced with CIITA, a key regulator of the MHC class II promoter (Chang et al, 1994) upon treatment with the drug U18666A. Increased levels of cholesterol in LEs due to U18666A treatment lead to a dramatic repositioning from the periphery to perinuclear regions (compare Figure 7A and B, top panels), evidenced by filipin staining in combination with CD63. CLSM analysis demonstrate that HLA-DR and CD63 co-localize in peripheral LEs of HELA-CIITA cells and that upon cholesterol accumulation the vesicles are repositioned to the perinuclear regions (Figure 7A and B). In contrast, exogenous LMP1, as its endogenous counterpart in LCL, did not co-localize with HLA-DR and upon U18666A treatment, the LMP1-positive vesicles remained in the cellular periphery. Remarkably, a proportion of the endogenous CD63 that assembled with LMP1 remained in peripheral vesicles upon U18666A treatment, suggesting that LMP1 modifies CD63 physiology. Previous work showed that the oxysterol-binding protein ORP1L functions as a cholesterol sensor in LE positioning (Rocha et al, 2009). Control experiments indicated that ORP1L–GFP co-localized with endogenous CD63 in peripheral vesicles of HELA-CIITA cells while exogenous LMP1 did not, suggesting that elevated cholesterol levels in LMP1 vesicles cannot be sensed by ORP1L. In fact, filipin staining suggested that cholesterol levels are not increased in LMP1/CD63 peripheral vesicles (Supplementary Figure S5). We thus confirm our EM-based suggestions that HLA-DR and LMP1 reside in distinct compartments as judged by cholesterol-sensing ability upon U18666A treatment. LMP1 appears to re-route a significant fraction of CD63 into cholesterol ‘low’ compartments that are able to retain their peripheral position in the presence of U18666A.

Figure 7.

LMP1/CD63 peripheral vesicles do not accumulate cholesterol upon U18666A treatment. (A) HELA-CIITA cells were transfected with wtLMP1 and CLSM analysis was performed using LMP1-, CD63- and HLA-DR-specific antibodies in untreated (A) or U18666A-treated cells in the indicated combinations. (B) U18666A treatment causes accumulation of cholesterol in late endosomes as measured by filipin staining and repositioning to the nucleus ((A, B) upper rows). While HLA-DR (green) and CD63 (red) peripheral vesicles are repositioned to the perinuclear region upon U18666A treatment (second row) this has no effect on vesicles that contain LMP1 (third and fourth row). Note that HLA-DR/CD63 vesicles repositioned to the nucleus but LMP1/CD63 vesicles not.

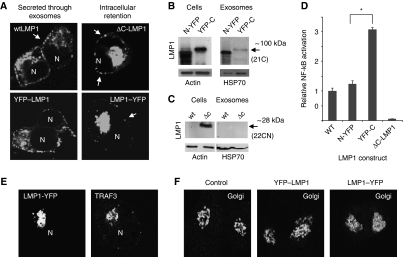

Endosomal-exosomal trafficking and sorting of LMP1 is coupled to signalling

The fusion of a GFP moiety to the cytoplasmic C-terminus of LMP1 disturbed trafficking to exosomes and subcellular distribution (Supplementary Figure S4). To demonstrate whether a modification at either the C- and or N-terminus determines proper LMP1 trafficking and secretion through exosomes, we expressed LMP1–YFP fusion constructs at both N- and C-terminus. The cellular distribution of LMP1 protein with an N-terminally tagged YFP (YFP–LMP1) was similar as wtLMP1 and accordingly targeting to exosomes was unaffected (Figure 8A and B). However, expressing LMP1 as a C-terminal YFP fusion protein (LMP1–YFP) resulted in a marked accumulation/redistribution of the protein to the perinuclear region (Figure 8A) and consequently impaired secretion through exosomes (Figure 8B). To confirm that the C-terminus controls LMP1 trafficking to exosomes, we deleted the complete cytoplasmic C-terminal region of LMP1 (ΔC-LMP1). CLSM revealed a similar redistribution and accumulation in the perinuclear area of ΔC-LMP1 compared with LMP1–YFP (Figure 8A) in the majority of cells (92 and 81%, respectively). Importantly, exosomal secretion of this deletion mutant was impaired (Figure 8C). In summary, the wild-type C-terminus of LMP1 controls proper intracellular trafficking leading to secretion via exosomes.

Figure 8.

Modification of LMP1 C-terminus abrogates trafficking to exosomes. (A) HEK293 cells were seeded on coverslips and after 24 h transfected with wtLMP1, YFP–LMP1 or LMP1–YFP, or a C-terminal deletion mutant (ΔC-LMP1). After 24 h, cells were fixed and stained for LMP1 and CLSM shows subcellular localization of LMP1 (N represents nuclei). (B) HEK293 cells were transfected with N-terminally tagged (N-YFP) or C-terminally tagged (YFP-C) LMP1 constructs. After 48 h, exosomes were purified from the medium. Both the cell and the exosome-preparation lysates were subjected to western blotting analysis for LMP1, actin and HSP70. (C) HEK293 cells were transfected with wild-type (wt) or ΔC-LMP1 (ΔC) construct. After 48 h, exosomes were purified from the medium. Both the cell and the exosome-preparation lysates were subjected to western blotting analysis for LMP1, actin and HSP70. (D) HEK293 cells were transfected with wtLMP1 (WT), N-YFP, YFP-C or empty vector control, together with an NF-κB-reporter construct (Firefly luciferase) and a transfection control (Gaussia luciferase). After 24 h, cell lysates were analysed for Firefly luciferase activity, and supernatants for Gaussia luciferase activity (Student's _t_-test, *P<0.05; error bars represent s.e.m., _n_=4). (E) HEK293 cells transfected with LMP1–YFP were analysed by CLSM showing similar (co)-localization of LMP1–YFP and TRAF3 in the perinuclear region, presumably Golgi compartments. (F) CLSM analysis of HEK293 cells that express YFP–LMP1, or LMP1–YFP or wtLMP1 (control) were fixed and stained with the cis-Golgi marker GM130. Represented in each image are two individual cells. Note the ‘fuzzy’ GM130-Golgi staining in the LMP1–YFP expressing cells (right image).

Interestingly, we determined, with dual NF-κB-luciferase reporter assays, that the retention of LMP1–GFP markedly increased NF-κB activity (Supplementary Figure S6A). In agreement with this, we demonstrate that N-terminally tagged YFP–LMP1 resembled a ‘normal’ wtLMP1 distribution and a similar level of NF-κB activation, while C-terminally tagged LMP1–YFP (the form of LMP1 that is precluded from secretion through exosomes) showed a 3-fold increase in NF-κB activation (Figure 8D). As suspected from its subcellular localization, LMP1–YFP was retained in GM130-positive (cis)-Golgi compartments (Figure 8E). Consistent with this conclusion, we observed that LMP1–YFP in transfected cells had an effect on GM130 distribution (more bright) and co-localized to TRAF3-rich regions as demonstrated previously (Liu et al, 2006; Figure 8F). In contrast, wtLMP1 and YFP–LMP1 had no effect on GM130 distribution. Thus, the modifications to the LMP1 C-terminus impair intracellular LMP1 trafficking and export via exosomes, which increases downstream NF-κB signalling.

CD63 controls NF-_κ_B activity levels induced by LMP1

We showed that endogenous LMP1, associates with CD63 in peripheral vesicles presumably MVEs and that these proteins share trafficking, sorting and secretion via exosomes independently on the EBV status. One distinctive property of tetraspanins is their ability to associate with each other and other transmembrane proteins (known as the tetraspanins web) via indirect associations retained in mild detergents such as CHAPS and/or Brij (Hemler, 2005; Le et al, 2006b). We expressed LMP1 in HEK293 cells and lysed the cells using Brij-98 as detergent. We co-isolated protein complexes with LMP1-specific antibodies that were enriched in CD63 as indicated by several specific bands observed between 40 and 70 kDa (Figure 9A), including an ∼43 kDa band, previously observed in LCL lysates (Figure 5A). Thus, in mild detergents that retain indirect protein interactions, LMP1 expressed in HEK293 cells associates closely with CD63.

Figure 9.

CD63-mediated trafficking of LMP1 attenuates NF-κB. (A) Exogenous LMP1 associates with CD63 in HEK293 cells. LMP1 and IgG control immunoprecipitates from equal amounts of 1% Brij-98 lysates were examined by western blotting for LMP1 and CD63. (B) HEK293 cells were transfected with a shRNAs vector targeting CD63, or a scrambled (scr) control vector. Knockdown was confirmed with RT–PCR, western blotting analysis and by CLSM in LMP1-transfected CD63 KD compared with control cells. These images were obtained with similar settings (* indicates nuclei) (error bar represents s.d.; _n_=3). (C) Scr and CD63 shRNA expressing HEK293 cells were transfected with wtLMP1, NF-κB-reporter construct (Firefly luciferase) and a transfection control construct (Gaussia luciferase). After 24 h, cell lysates were analysed for Firefly luciferase activity, and supernatants for Gaussia luciferase activity (Student's _t_-test, *P<0.05; error bars represent s.e.m.; _n_=3). (D) HEK293 cells expressing scr or CD63 shRNAs were transfected with increasing amounts (20, 50, 300 and 700 ng, respectively) of wtLMP1, together with an NF-κB-reporter construct (Firefly luciferase) and a transfection control (Gaussia luciferase). Graph shows relative induction of NF-κB in shCD63 KD cells over control (error bars represent s.d.; shown is one representative experiment; _n_=3). (E) Scr and CD63 shRNA expressing HEK293 cells were transfected with wtLMP1 and protein levels were analysed in cells and purified exosomal fractions 24 h after transfection by western analysis. Note the decrease in exosome production in the CD63 KD cells as indicated by a reduction in HSP70 levels. (F) Dual-fluorescent CLSM combined with transmission imaging shows LMP1 and TRAF3 staining patterns in HEK293, LCL and BJAB-LMP1 (24 h induced), respectively. (G) Hypothetical model representing LMP1 trafficking to exosomes in LCL cells. LMP1 is synthesized in the ER and traffics through the Golgi from which it mediates NF-κB signalling. Subsequently, LMP1 traffics to and accumulates in microdomains of the limiting membrane (LM) of multivesicular endosomes (MVEs). Inward budding of domains that contain both LMP1 and CD63 form intraluminal vesicles (ILVs). ILVs that contain LMP1 and CD63 are secreted as exosomes upon fusion of the LM with the plasma membrane (PM).

To establish that CD63 controls LMP1-mediated NF-κB activity in HEK293 cells, we reduced endogenous CD63 protein levels by introducing short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) (for details, Supplementary Figure S7). Transfection of CD63 shRNA constructs in HEK293 cells, yielded an ∼80% reduction in transcript levels as measured by semi-quantitative RT–PCR and a sizeable but not complete decrease in protein levels compared with cells transfected with equal amounts of scrambled shRNA (Figure 9B). CLSM suggest that LMP1 in CD63 KD cells is disturbed and accumulates in perinuclear regions in ∼50% of the cells (Figure 9B). Some accumulation of LMP1 was also observed in 28% of the shRNA control cells; however, the redistribution of LMP1 lead to a dramatic increase in LMP1-induced NF-κB activity (Figure 9C), suggesting CD63 KD cells are ‘sensitized’ to LMP1-mediated NF-kB activation. Indeed transfections with as low as 20 ng of LMP1 plasmid DNA lead already to a two-fold increase in NF-κB activation levels in CD63 KD cells compared with shRNA control cells (Figure 9D). To confirm that cellular CD63 levels are important for LMP1 trafficking in the endosomal-exosomal pathway, we analysed exogenous LMP1 protein levels in CD63 KD cells. We observed that full-length LMP1 protein levels are significantly increased at 24 h after transfection in the CD63 KD cells compared with shRNA control cells and to a lesser extent at 48 h (Supplementary Figure S7B). In agreement with this observation, we found that LMP1 levels in the exosomal fraction was reduced, most probably because CD63 KD cells showed reduced exosome secretion as measured by HSP70 levels (Figure 9E). While multiple tetraspanins, including CD63 operate in cellular pathways together (Hemler, 2005; Pols and Klumperman, 2009; Schroder et al, 2009), we conclude that CD63 is a negative regulator of LMP1-mediated NF-κB activation in HEK293 cells.

Previous studies with exogenous LMP1 suggested that active LMP1 signalling complexes are formed in lipid rafts of Golgi membranes as judged in part by TRAF3 co-localization (Lam and Sugden, 2003; Liu et al, 2006). We showed in Figure 4I that endogenous LMP1 and TRAF3 have distinct staining patterns and that only a minor fraction of LMP1 seems to reside in Golgi compartments. To investigate this in better detail, we combined CLSM analysis with transmission data and show that endogenous LMP1 and TRAF3 proteins in LCL do not localize in peripheral vesicles and reside in distinct compartments. In addition, we did not detect any TRAF3 recruitment by exogenous expression of LMP1 in BJAB or HEK293 cells in peripheral vesicles (Figure 9F; Supplementary Video SV2). This is consistent with previous findings suggesting that active LMP1 signalling complexes reside in TRAF3-rich perinuclear compartments, presumably the Golgi (Kaykas et al, 2001; Lam and Sugden, 2003; Liu et al, 2006). Thus, the major proportion of endogenous LMP1 in LCL resides in LEs that do not encompass active LMP1 signalling complexes as indicated by the absence of TRAF3.

Discussion

We studied the intracellular transport of the endogenous EBV-encoded oncogene LMP1 to elucidate how downstream constitutive NF-κB activation is restrained. We demonstrate that LMP1 associates with the tetraspanin CD63 in microdomains and accumulates in a subset of MVEs. We demonstrated that the reported association of LMP1 within cholesterol-enriched domains or lipid rafts does not mediate trafficking/sorting into late endosomes and exosomes, respectively. Instead, Golgi retention by GFP fusion or via CD63 knockdown dramatically increased LMP1-mediated NF-κB activation consistent with the Golgi being signalling-active sites of LMP1. Our findings indicate that LMP1 exploits CD63 trafficking for an ‘exit-strategy’ to antagonize constitutive NF-κB (over)activation.

Generally, incorporation of ubiquitylated proteins into ILVs within MVEs are destined for lysosomal degradation, a process controlled by the evolutionary conserved ESCRT complex (Piper and Katzmann, 2007; Piper and Luzio, 2007). While there is some evidence that LMP1 in LCLs is delivered to lysosomes via autophagy, a role for ubiquitin was not studied (Lee and Sugden, 2008a). Autophagy pathways selectively remove protein aggregates, while the ubiquitin–proteasome system is involved in the rapid degradation of proteins. Early studies proposed that LMP1 is a short-lived protein (Baichwal and Sugden, 1987; Mann and Thorley-Lawson, 1987) presumably because it is targeted for degradation by proteasomes via lysine-independent ubiquitylation (Aviel et al, 2000). However, these studies did not consider the effect of proteasome inhibition on the intracellular ubiquitin pool and MVE formation (Dantuma et al, 2006). Thus, while evidence exists that LMP1 is degraded, in part via common pathways, we demonstrate here that a significant proportion of LMP1 escapes degradation by selective incorporation into MVEs, and secretion into the extracellular space through exosomes. While ubiquitin-driven sorting favours lysosomal targeting and degradation of membrane proteins, ubiquitin–ESCRT-independent sorting mechanisms through membrane (lipid) domains may preferentially support secretion through exosomes (Piper and Katzmann, 2007; Piper and Luzio, 2007; Trajkovic et al, 2008; Buschow et al, 2009; Gauvreau et al, 2009). Our studies agree with this, in that LMP1 is abundantly secreted through exosomes by multiple cell types and that ubiquitylation does not seem to affect sorting efficiency into exosomes.

What could be the mechanism by which LMP1 is sorted into exosomes? Lipid domains, notably conventional rafts on the surface of most B cells, are enriched in cholesterol, sphingomyelin and glycolipids such as ganglioside-1 (GM1) (De et al, 2003; Muntasell et al, 2007), which is strikingly similar to the composition of MHC class II-positive B-cell exosomes (Wubbolts et al, 2003). LMP1 is a lipid-raft-associated protein, as defined by its presence in DRM fractions at 0°C. Although DRMs do not accurately represent microdomains in membranes of living cells, we conjectured that LMP1 maybe sorted into exosomes through its lipid-raft anchoring domain FWLY (Yasui et al, 2004; Soni et al, 2006; Lee and Sugden, 2007), yet mutations in FWLY did not affect sorting. In fact, endogenous LMP1 did not co-localize with endocytosed GM1, which was in agreement with our failure to detect endogenous LMP1 on the plasma membrane of LCL. LMP1 did not reside in MHC II-enriched peripheral compartments in both LCL and HELA-CIITA cells. Interestingly, exogenous LMP1 seemed to recruit CD63 into vesicles excluding MHC II possibly because these sustained low cholesterol levels even under cholesterol accumulating conditions by U18666A treatment (Figures 4 and 7). This diversification of LMP1 and HLA-DR containing compartments is consistent with findings in LCL, indicating that MVEs are highly heterogeneous in cholesterol content (Mobius et al, 2003). Provocatively, we observed that some MVEs in LCLs are enriched with LMP1 while others appear to lack LMP1. Possibly, MHC class II, in contrast to LMP1, is endocytosed via cholesterol-enriched lipid rafts from the cell surface, before sorting in exosomes (De et al, 2003; Muntasell et al, 2007).

We showed by various visualization techniques that LMP1 recruits and assembles in tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs). Specifically, we showed that knockdown of the tetraspanins CD63 leads to disturbed LMP1 trafficking, signalling and secretion through exosomes. Co-IP experiments using non-ionic (mild) detergents confirmed that in LCL- and LMP1-transfected HEK293 cells endogenous and exogenous LMP1 associates with CD63 (Figures 5A and 9A). Because LMP1 lacks endosomal sorting motifs (Bonifacino and Traub, 2003), it is tempting to speculate that formation of endosomal subdomains with closely associated LMP1 and CD63 may drive the sorting and secretion through exosomes explaining their relative enrichment in these vesicles. Such a mechanism was recently proposed for lipid domain (ceramide)-dependent exosomal sorting of proteolipid protein (Trajkovic et al, 2008). Membrane microdomains enriched in tetraspanins (TEMs) often co-exist with conventional lipid rafts and can be isolated together biochemically, but are functionally distinct entities in living cells (Nydegger et al, 2006; Le et al, 2006b; Pols and Klumperman, 2009). TEMs assemble in part through palmitoylation that presumably occurs in the Golgi and several proteins that associate with tetraspanins are palmitoylated themselves and can be co-isolated using 1% Brij or CHAPS buffers (Hemler, 2005). Because LMP1 is palmitoylated (Higuchi et al, 2001), it is attractive to speculate that palmitoylation-mediated interactions has a role in CD63-LMP1 trafficking to exosomes. Consistent with this, we observed that complexes of exogenous LMP1 and CD63 are readily co-isolated in lysates containing Brij-98 (Figure 9A). Nevertheless, direct interactions possibly with LMP1s C-terminal region cannot be ruled out and thus to completely understand the nature of this association, further exploration is required. Ultimately, we predict that multiple tetraspanins and possibly various types of molecular interactions influence intracellular trafficking and sorting of LMP1 into the endosomal-exosomal pathway.

The major role of LMP1 is not secretion via exosomes, but to activate critical signalling pathways such as the NF-κB pathway that drives the proliferation of EBV-infected cells into a GC type reaction for establishment of viral persistence (Thorley-Lawson, 2001). LMP1 activates NF-κB constitutively upon self-aggregation and as a consequence cannot be under the control of an external ligand (Gires et al, 1997; Liu et al, 2006) raising the risk of developing neoplasia (Thorley-Lawson and Gross, 2004; Staudt, 2010). In line with this, Lam and Sugden (2003) demonstrated that LMP1 signals predominantly from intracellular compartments, presumably the Golgi. A large body of previous work, indicated that LMP1 signalling activation corresponds to its ability to associate in lipid rafts (Higuchi et al, 2001; Coffin et al, 2003; Lam and Sugden, 2003; Yasui et al, 2004; Liu et al, 2006; Lee and Sugden, 2007). However, timely termination of LMP1 signalling maybe equally beneficial for viral persistence. We show that CD63 has an important role in restraining LMP1-mediated NF-κB signalling activity through its function as a molecular chaperone into the endosomal-exosomal pathway. How and where is LMP1 signalling initiated? Liu and co-workers showed recently that upon synthesis in the ER exogenous LMP1 binds to the Rab-associated protein Pra1 and is chaperoned to the Golgi from which it activates NF-κB, presumably via TRAF3. Consistent with this, LMP1 retention in the ER attenuated LMP1 signalling (Liu et al, 2006) and we observed that LMP1 mutants trapped in the Golgi have enhanced signalling (Figure 8D). Because the major pool of endogenous LMP1 resides in peripheral vesicles, presumably LEs that lack the ability to recruit TRAF3 (Figures 4 and 9), we conclude that in LCLs (as well as Raji, data not shown) this proportion of LMP1 does not signal through TRAF3, consistent with recent RNA interference studies (Guasparri et al, 2008).

Although the exact location of active endogenous LMP1 signalling complexes is not (yet) firmly established, based on the current knowledge we propose that upon synthesis in the ER, endogenous LMP1 aggregates in the cholesterol-rich membranes of Golgi compartments from which LMP1 is presumed to initiate NF-κB activation (Lam and Sugden, 2003; Liu et al, 2006). Subsequently, LMP1 associates with CD63 in microdomains leading to incorporation into the LM of MVEs and accumulates within ILVs. From these sites, LMP1 is restricted form activating NF-κB. When LMP1 containing MVEs fuse with the plasma membrane ILVs enriched in LMP1 and CD63 are released as exosomes (Figure 9G). Our data suggest exploitation of distinct membrane subdomains by EBV-encoded LMP1. Our model may also explain how LMP1 limits adverse cellular effects due to uncontrolled constitutive NF-κB activation (Hammerschmidt et al, 1989; Floettmann et al, 1996; Le et al, 2006a; Lee and Sugden, 2008a, 2008b). But would there be a benefit for the virus in secreting LMP1 via exosomes, rather than to simply degrading it? Secreted LMP1 causes negative effects on responding T cells (Dukers et al, 2000; Flanagan et al, 2003) that could be of importance when the infected cell passes through the lymph nodes (Middeldorp and Pegtel, 2008) possibly counteracting the exosomes carrying peptide-loaded MHC II that activate (virus specific) T cells (Muntasell et al, 2007; Buschow et al, 2009). This may be relevant for EBV tumours expressing the EBV default or growth program where LMP1 levels are disturbed (elevated), providing a constant flow of new LMP1 resulting in continuous NF-κB activation supporting oncogenesis (Hiscott et al, 2001; Staudt, 2010). Interestingly, a conceptually related study showed recently that the tetraspanins CD82 and CD9 restrain Wnt signalling by targeting β-catenin for exosomal release, explaining how CD82 may acts as a metastasis suppressor (Chairoungdua et al, 2010). The secreted form of LMP1 could aid the infected tumour cells to escape from immune surveillance (Dukers et al, 2000; Flanagan et al, 2003). Such a view is in line with accumulating evidence suggesting that viruses manipulate uninfected neighbouring cells via functional delivery of viral gene products (Middeldorp and Pegtel, 2008; Xu et al, 2009; Lenassi et al, 2010; Meckes et al, 2010; Pegtel et al, 2010).

Materials and methods

Cell culture

RN, an EBV-transformed human B-cell line RN (HLA-DR15, kind gift from W Stoorvogel), was cultured as previously described (Pegtel et al, 2010). BJAB-LMP1 cell line expressing LMP1 under the control of an inducible promoter, and its LMP1-negative counterpart (BJAB-tTA, kind gifts from M Rowe) were cultured in RPMI-1640 (BioWitthaker), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Perbio Sciences HyClone), 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulphate and 2 mM glutamine in the presence of 125 ng/μl tetracycline (Sigma). For LMP1 induction, cells were washed five times with PBS, and cultured in the absence of tetracycline. Medium and cells were harvested after 24 h incubation. HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Perbio Sciences HyClone), 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulphate and 2 mM glutamine.

Plasmids, transfection and RNA interference

The pcDNA3.1-LMP1-wt, pcDNA3.1-Ub-LMP1-wt, pEGFP-LMP1-GFP, and pEGFP-Ub-LMP1-GFP constructs were a kind gift from Rajiv Khanna and Judy Tellam. The pCDNA3.1-YFP-LMP1 and the pcDNA3.1-LMP1-YFP constructs were a kind gift from Hao-Ping Liu. The pSG5-LMP1-M2, pSG5-LMP1-M6 constructs of LMP1 carrying point mutations in the TM1-FWLY region or the TM2 control region, respectively, as well as the p3x-κB-Luc (NF-κB) were described before (Yasui et al, 2004). The Gaussia construct LV-Gluc-CFP was described previously (Wurdinger et al, 2008). The pcDNA3.1-LMP1-ΔC plasmid was constructed by amplifying amino acids 1–186 out of the LMP1-wt vector using the primers 5′-TAAAGGATCCAAATGGAACACGACCTTGAGAG-3′ and 5′-GGCGGAATTCGCCTAGTAATACATCCAGATTAAAATC-3′ and cloning it into a pcDNA3 backbone using _Bam_HI and _Eco_RI restriction. Transfections were carried out using Lipofectamin 2000 reagent (Invitrogen), typically with 500 ng plasmid. In general, unless otherwise noted, cells were examined 24 h after transfection for transfection efficiency with an eGFP control vector. Constructs carrying shRNAs from the TRC and Sigma Mission library were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MI). The human CD63-specific constructs used were TRCN0000007489-7853 (called #1–5, respectively). The scrambled (scr) shRNA construct used as a negative control was SHC002 from Sigma-Aldrich. All shRNA constructs were in the pLKO.1 vector backbone. Five individual shRNAs against parts of the CD63 sequence and a scrambled control version to test for non-specific target effects and selected 24 h after transfection in HEK293 cells cultured in standard medium containing 1 μg/ml Puromycin for 24 h.

Antibodies and reagents

LysoTracker red DND-99 was purchased from Molecular Probes. Cholera Toxin B Subunit FITC conjugate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. OT21C and OT21A are non-commercial monoclonal antibodies directed to LMP1 that reacts with a conformational epitope mapping at residues 290–318 described previously (Meij et al, 1999). Non-commercial polyclonal antibodies HLA-DR anti-CD63 (NKI-C3) were produced in the laboratory of Dr Jacques Neefjes (NKI, Amserdam). Monoclonal antibodies directed against GM130 (Golgi), Cytochrome C and CD63 were purchased from BD Biosciences, HSP70 and β-actin from Santa Cruz, CD81 from Diaclone. Polyclonal antibodies against HLA-DR and TRAF3 were purchased from Santa Cruz, EEA1 from Cell Signaling. Secondary antibodies swine anti-rabbit FITC, rabbit anti-mouse FITC, swine anti-rabbit HRP and rabbit anti-mouse HRP were purchased from DAKO, goat anti-mouse Alexa594 from Molecular Probes. Chloroquine, Wortmannin, Monensin and poly-L-lysine are purchased from Sigma. For western blotting, cells or exosomes were lysed in a 1% SDS buffer and equal amounts of protein were loaded onto an SDS/PAGE gel. Only gels for CD63 (BD) detection were run under non-reducing conditions. For IP experiments in LCL and BJAB control, cells were lysed and sonicated in a non-denaturing lysis buffer containing Tris (pH 8) 20 mM, NaCl, 10% glycerol, 10%, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA in water including PIC (Protein Inhibitor Cocktail; Roche) on ice. In LMP1-transfected HEK293 cells, instead of Triton X-100 we used a 1% Brij-98. ProtG beads were added to a pre-cleared IP lysate with equal concentrations of S12 and OT21C anti-LMP1 or indicated IgG (control) antibodies incubated ON at 4°C. The beads with captured protein complexes were washed with PBS and the bound proteins subsequently lysed in western blotting buffer for further analysis.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

For immunofluorescence and CLSM analysis, HEK293 cells, seeded on poly-L-lysine coated 10 mm coverslips in 24-well plate, and were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (20 min), permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X (10 min), and blocked with PBS containing 10% FCS (1 h). Lymphoblastoid cells were equally treated after cytospin preparation. The slides were incubated with the primary antibodies for 30 min at RT, followed by incubation with species-specific fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies for 30 min at room temperature, mounted with the Vectashield reagent (Vector Laboratories Inc., CA, USA) and sealed with nail polish. Filipin staining was imaged with a microscope (AxioObserver Z1; Carl Zeiss, Inc.) equipped with a charge-coupled device camera (ORCA-ER; Hamamatsu Photonics) and a × 63 NA 1.25 Plan-Neofluar oil-corrected objective lens. All other stainings were imaged with a Leica DMRB microscope (Leica, Cambridge, UK). All confocal images were obtained through sequential scanning with the pinhole set at 1AE (standard) and when indicated identical settings were maintained to analyse differences in fluorescence intensity. ImageJ software was used for all statistical analysis including calculation of PCCs.

Electron microscopy

For conventional EM, LCL was fixed with a mixture of 2% paraformaldehyde and 1% glutaraldehyde in 0.2 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), post-fixed with 1% OsO4, dehydrated in ethanol and embedded in Araldite 6005. Cell blocks were immersed in 2.3 M sucrose before freezing in liquid nitrogen. Ultrathin cryosections were cut and for immunolabelling, grids were incubated for 30 min at 37°C on gelatine, blocked with 1% BSA in PBS/Glycine for 3 min, incubated with the monoclonal in 1% BSA in PBS, blocked again with 0.1% BSA in PBS/Glycine, and incubated with Protein-A Gold (PAG) diluted in 1% BSA. Grids were fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde in PBS, put on uranylacetate/methylcellulose (pH 4.0) and dried on air. Ultrathin sections were viewed with a JEOL 1010 electron microscope after counterstaining with uranyl acetate.

NF-_κ_B-reporter assays

Dual luciferase reporter assays were normalized for transfection efficiency by co-transfecting a Gaussia luciferase expression plasmid and dividing Firefly luciferase by Gaussia luciferase activity at 20–24 h after transfection of HEK293 cells. Luciferase activities in the presence of LMP1 were plotted relative to luciferase reporter construct (p3X-κB-L) (Luftig et al, 2003) in the absence of the indicated LMP1 constructs typically at 500 ng plasmid unless otherwise noted, or LMP1-wt was set as 100%. Luciferase assays were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Promega).

Exosome isolation

Exosomes were prepared from the supernatant of 1- or 2-day-old LCL as previously described (Pegtel et al, 2010). Exosomes of transfected HEK293 cultures were stimulated with 10 μM Monensin (Sigma) 2 h before isolation when indicated. In brief, exosomes were purified from the cultured media with exosome-free serum. Differential centrifugations at 500 g (2 × 10 min), 2000 g (2 × 15 min), 10 000 g (2 × 30 min) eliminated cellular debris and centrifugation at 70 000 g (60 min) pelleted exosomes. The exosome pellet was washed once in a large volume of PBS, centrifuged at 60 000 g for 1 h and re-suspended in sample buffer for western analysis.

RNA isolation and RT–PCR

Total RNA was isolated with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturers' protocol. RNA was converted to cDNA using the AMV Reverse Transcriptase System from Promega. Briefly, 1 μg RNA was incubated with 250 ng random primers for 5 min at 65°C followed by cDNA synthesis using five units AMV-RT for 45 min at 42°C in a total volume of 20 μl. Semi-quantitative PCR reactions were performed with SYBR Green I Master using the LightCycler480 System (Roche Diagnostics) and consisted of 10 min incubation at 95°C, followed by 45 cycles of 10 s 95°C, 15 s 60°C and 15 s 72°C. Amplification and melting curves were analysed using the LightCycler480 Software release 1.5.0. The following primers were used for CD63 RT–PCR: Fw 5′-GTAGCCCCCTGGATTATGGT-3′, Rev 5′-CTTGCTCTACGTCCTCCTGC-3′.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Video SV1

Supplementary Video SV2

Supplementary Data

Review Process File

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs Rajiv Khanna and Judy Tellam for providing the Ub–LMP1 and LMP1–GFP constructs. Donna Fluitsma and Hans Jansen for their support with EM techniques and reagents. Dr Martin Rowe for the BJAB-tTA-LMP-1 inducible cell lines, Dr Hao-Ping Liu for the LMP1–YFP constructs, Dr Willem Stoorvogel for providing the RN cell line, Peter van den Elsen for HeLa cells expressing CIITA and Jeroen Belien as well as Kees Jalink for their excellent support with CLSM analysis. This work was funded by the Dutch Cancer Foundation (KWF-3775) and in part by the Dutch Science foundation (NWO-Veni) to DMP. EK and ECMF are supported by NIH R01CA085180.

Author contributions: FJV, JMM and DMP conceived the experiments. FJV carried out most experiments except cryo-EM with initial help of MAJvE, RvdK, TW and ESH. TV performed the cryo-EM. ECMF, EK, RvdK, JN, TW and DG developed key reagents and analysed data with FJV, JMM and DMP. DMP wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Arita S, Baba E, Shibata Y, Niiro H, Shimoda S, Isobe T, Kusaba H, Nakano S, Harada M (2008) B cell activation regulates exosomal HLA production. Eur J Immunol 38: 1423–1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviel S, Winberg G, Massucci M, Ciechanover A (2000) Degradation of the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Targeting via ubiquitination of the N-terminal residue. J Biol Chem 275: 23491–23499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock GJ, Thorley-Lawson DA (2000) Tonsillar memory B cells, latently infected with Epstein-Barr virus, express the restricted pattern of latent genes previously found only in Epstein-Barr virus-associated tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 12250–12255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baichwal VR, Sugden B (1987) Posttranslational processing of an Epstein-Barr virus-encoded membrane protein expressed in cells transformed by Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol 61: 866–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino JS, Traub LM (2003) Signals for sorting of transmembrane proteins to endosomes and lysosomes. Annu Rev Biochem 72: 395–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JM, Lee SP, Leese AM, Thomas WA, Rowe M, Rickinson AB (2009) Cyclical expression of EBV latent membrane protein 1 in EBV-transformed B cells underpins heterogeneity of epitope presentation and CD8+ T cell recognition. J Immunol 182: 1919–1928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschow SI, Nolte-'t Hoen EN, van NG, Pols MS, ten BT, Lauwen M, Ossendorp F, Melief CJ, Raposo G, Wubbolts R, Wauben MH, Stoorvogel W (2009) MHC II in dendritic cells is targeted to lysosomes or T cell-induced exosomes via distinct multivesicular body pathways. Traffic 10: 1528–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahir-McFarland ED, Davidson DM, Schauer SL, Duong J, Kieff E (2000) NF-kappa B inhibition causes spontaneous apoptosis in Epstein-Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 6055–6060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarelli S, Visco V, Raffa S, Wakisaka N, Pagano JS, Torrisi MR (2007) Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 promotes concentration in multivesicular bodies of fibroblast growth factor 2 and its release through exosomes. Int J Cancer 121: 1494–1506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chairoungdua A, Smith DL, Pochard P, Hull M, Caplan MJ (2010) Exosome release of beta-catenin: a novel mechanism that antagonizes Wnt signaling. J Cell Biol 190: 1079–1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Fontes JD, Peterlin M, Flavell RA (1994) Class II transactivator (CIITA) is sufficient for the inducible expression of major histocompatibility complex class II genes. J Exp Med 180: 1367–1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin WF III, Geiger TR, Martin JM (2003) Transmembrane domains 1 and 2 of the latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus contain a lipid raft targeting signal and play a critical role in cytostasis. J Virol 77: 3749–3758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantuma NP, Groothuis TA, Salomons FA, Neefjes J (2006) A dynamic ubiquitin equilibrium couples proteasomal activity to chromatin remodeling. J Cell Biol 173: 19–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RE, Brown KD, Siebenlist U, Staudt LM (2001) Constitutive nuclear factor kappaB activity is required for survival of activated B cell-like diffuse large B cell lymphoma cells. J Exp Med 194: 1861–1874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RE, Ngo VN, Lenz G, Tolar P, Young RM, Romesser PB, Kohlhammer H, Lamy L, Zhao H, Yang Y, Xu W, Shaffer AL, Wright G, Xiao W, Powell J, Jiang JK, Thomas CJ, Rosenwald A, Ott G, Muller-Hermelink HK et al. (2010) Chronic active B-cell-receptor signalling in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nature 463: 88–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De GA, Geminard C, Fevrier B, Raposo G, Vidal M (2003) Lipid raft-associated protein sorting in exosomes. Blood 102: 4336–4344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirmeier U, Neuhierl B, Kilger E, Reisbach G, Sandberg ML, Hammerschmidt W (2003) Latent membrane protein 1 is critical for efficient growth transformation of human B cells by Epstein-Barr virus. Cancer Res 63: 2982–2989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukers DF, Meij P, Vervoort MB, Vos W, Scheper RJ, Meijer CJ, Bloemena E, Middeldorp JM (2000) Direct immunosuppressive effects of EBV-encoded latent membrane protein 1. J Immunol 165: 663–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escola JM, Kleijmeer MJ, Stoorvogel W, Griffith JM, Yoshie O, Geuze HJ (1998) Selective enrichment of tetraspan proteins on the internal vesicles of multivesicular endosomes and on exosomes secreted by human B-lymphocytes. J Biol Chem 273: 20121–20127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Borja M, Wubbolts R, Calafat J, Janssen H, Divecha N, Dusseljee S, Neefjes J (1999) Multivesicular body morphogenesis requires phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase activity. Curr Biol 9: 55–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan J, Middeldorp J, Sculley T (2003) Localization of the Epstein-Barr virus protein LMP 1 to exosomes. J Gen Virol 84: 1871–1879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floettmann JE, Ward K, Rickinson AB, Rowe M (1996) Cytostatic effect of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 analyzed using tetracycline-regulated expression in B cell lines. Virology 223: 29–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauvreau ME, Cote MH, Bourgeois-Daigneault MC, Rivard LD, Xiu F, Brunet A, Shaw A, Steimle V, Thibodeau J (2009) Sorting of MHC class II molecules into exosomes through a ubiquitin-independent pathway. Traffic 10: 1518–1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gires O, Zimber-Strobl U, Gonnella R, Ueffing M, Marschall G, Zeidler R, Pich D, Hammerschmidt W (1997) Latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus mimics a constitutively active receptor molecule. EMBO J 16: 6131–6140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guasparri I, Bubman D, Cesarman E (2008) EBV LMP2A affects LMP1-mediated NF-kappaB signaling and survival of lymphoma cells by regulating TRAF2 expression. Blood 111: 3813–3820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt W, Sugden B, Baichwal VR (1989) The transforming domain alone of the latent membrane protein of Epstein-Barr virus is toxic to cells when expressed at high levels. J Virol 63: 2469–2475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzivassiliou EG, Kieff E, Mosialos G (2007) Constitutive CD40 signaling phenocopies the transforming function of the Epstein-Barr virus oncoprotein LMP1 in vitro. Leuk Res 31: 315–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemler ME (2005) Tetraspanin functions and associated microdomains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 801–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi M, Izumi KM, Kieff E (2001) Epstein-Barr virus latent-infection membrane proteins are palmitoylated and raft-associated: protein 1 binds to the cytoskeleton through TNF receptor cytoplasmic factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 4675–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscott J, Kwon H, Genin P (2001) Hostile takeovers: viral appropriation of the NF-kappaB pathway. J Clin Invest 107: 143–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homig-Holzel C, Hojer C, Rastelli J, Casola S, Strobl LJ, Muller W, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Gewies A, Ruland J, Rajewsky K, Zimber-Strobl U (2008) Constitutive CD40 signaling in B cells selectively activates the noncanonical NF-kappaB pathway and promotes lymphomagenesis. J Exp Med 205: 1317–1329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houali K, Wang X, Shimizu Y, Djennaoui D, Nicholls J, Fiorini S, Bouguermouh A, Ooka T (2007) A new diagnostic marker for secreted Epstein-Barr virus encoded LMP1 and BARF1 oncoproteins in the serum and saliva of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 13: 4993–5000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudnall SD, Ge Y, Wei L, Yang NP, Wang HQ, Chen T (2005) Distribution and phenotype of Epstein-Barr virus-infected cells in human pharyngeal tonsils. Mod Pathol 18: 519–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Longnecker R (2007) Cholesterol is critical for Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2A trafficking and protein stability. Virology 360: 461–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaykas A, Worringer K, Sugden B (2001) CD40 and LMP-1 both signal from lipid rafts but LMP-1 assembles a distinct, more efficient signaling complex. EMBO J 20: 2641–2654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keryer-Bibens C, Pioche-Durieu C, Villemant C, Souquere S, Nishi N, Hirashima M, Middeldorp J, Busson P (2006) Exosomes released by EBV-infected nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells convey the viral latent membrane protein 1 and the immunomodulatory protein galectin 9. BMC Cancer 6: 283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam N, Sugden B (2003) LMP1, a viral relative of the TNF receptor family, signals principally from intracellular compartments. EMBO J 22: 3027–3038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le CC, Youlyouz-Marfak I, Adriaenssens E, Coll J, Bornkamm GW, Feuillard J (2006a) EBV latency III immortalization program sensitizes B cells to induction of CD95-mediated apoptosis via LMP1: role of NF-kappaB, STAT1, and p53. Blood 107: 2070–2078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le NF, Andre M, Boucheix C, Rubinstein E (2006b) Membrane microdomains and proteomics: lessons from tetraspanin microdomains and comparison with lipid rafts. Proteomics 6: 6447–6454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DY, Sugden B (2008a) The latent membrane protein 1 oncogene modifies B-cell physiology by regulating autophagy. Oncogene 27: 2833–2842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DY, Sugden B (2008b) The LMP1 oncogene of EBV activates PERK and the unfolded protein response to drive its own synthesis. Blood 111: 2280–2289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Sugden B (2007) A membrane leucine heptad contributes to trafficking, signaling, and transformation by latent membrane protein 1. J Virol 81: 9121–9130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenassi M, Cagney G, Liao M, Vaupotic T, Bartholomeeusen K, Cheng Y, Krogan NJ, Plemenitas A, Peterlin BM (2010) HIV Nef is secreted in exosomes and triggers apoptosis in bystander CD4+ T cells. Traffic 11: 110–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz D (1998) Epstein-Barr virus and a cellular signaling pathway in lymphomas from immunosuppressed patients. N Engl J Med 338: 1413–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HP, Wu CC, Chang YS (2006) PRA1 promotes the intracellular trafficking and NF-kappaB signaling of EBV latent membrane protein 1. EMBO J 25: 4120–4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luftig M, Prinarakis E, Yasui T, Tsichritzis T, Cahir-McFarland E, Inoue J, Nakano H, Mak TW, Yeh WC, Li X, Akira S, Suzuki N, Suzuki S, Mosialos G, Kieff E (2003) Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 activation of NF-kappaB through IRAK1 and TRAF6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 15595–15600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann KP, Thorley-Lawson D (1987) Posttranslational processing of the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded p63/LMP protein. J Virol 61: 2100–2108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J, Sugden B (1991) Transformation by the oncogenic latent membrane protein correlates with its rapid turnover, membrane localization, and cytoskeletal association. J Virol 65: 3246–3258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meckes DG Jr, Shair KH, Marquitz AR, Kung CP, Edwards RH, Raab-Traub N (2010) Human tumor virus utilizes exosomes for intercellular communication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 20370–20375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meij P, Vervoort MB, Aarbiou J, van DP, Brink A, Bloemena E, Meijer CJ, Middeldorp JM (1999) Restricted low-level human antibody responses against Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-encoded latent membrane protein 1 in a subgroup of patients with EBV-associated diseases. J Infect Dis 179: 1108–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middeldorp JM, Pegtel DM (2008) Multiple roles of LMP1 in Epstein-Barr virus induced immune escape. Semin Cancer Biol 18: 388–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobius W, van DE, Ohno-Iwashita Y, Shimada Y, Heijnen HF, Slot JW, Geuze HJ (2003) Recycling compartments and the internal vesicles of multivesicular bodies harbor most of the cholesterol found in the endocytic pathway. Traffic 4: 222–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntasell A, Berger AC, Roche PA (2007) T cell-induced secretion of MHC class II-peptide complexes on B cell exosomes. EMBO J 26: 4263–4272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nydegger S, Khurana S, Krementsov DN, Foti M, Thali M (2006) Mapping of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains that can function as gateways for HIV-1. J Cell Biol 173: 795–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegtel DM, Cosmopoulos K, Thorley-Lawson DA, van Eijndhoven MA, Hopmans ES, Lindenberg JL, de Gruijl TD, Wurdinger T, Middeldorp JM (2010) Functional delivery of viral miRNAs via exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 6328–6333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper RC, Katzmann DJ (2007) Biogenesis and function of multivesicular bodies. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 23: 519–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper RC, Luzio JP (2007) Ubiquitin-dependent sorting of integral membrane proteins for degradation in lysosomes. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19: 459–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pols MS, Klumperman J (2009) Trafficking and function of the tetraspanin CD63. Exp Cell Res 315: 1584–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G, Nijman HW, Stoorvogel W, Liejendekker R, Harding CV, Melief CJ, Geuze HJ (1996) B lymphocytes secrete antigen-presenting vesicles. J Exp Med 183: 1161–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha N, Kuijl C, van der KR, Janssen L, Houben D, Janssen H, Zwart W, Neefjes J (2009) Cholesterol sensor ORP1L contacts the ER protein VAP to control Rab7-RILP-p150 Glued and late endosome positioning. J Cell Biol 185: 1209–1225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roughan JE, Thorley-Lawson DA (2009) The intersection of Epstein-Barr virus with the germinal center. J Virol 83: 3968–3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roughan JE, Torgbor C, Thorley-Lawson DA (2010) Germinal center B cells latently infected with Epstein-Barr virus proliferate extensively but do not increase in number. J Virol 84: 1158–1168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder J, Lullmann-Rauch R, Himmerkus N, Pleines I, Nieswandt B, Orinska Z, Koch-Nolte F, Schroder B, Bleich M, Saftig P (2009) Deficiency of the tetraspanin CD63 associated with kidney pathology but normal lysosomal function. Mol Cell Biol 29: 1083–1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni V, Yasui T, Cahir-McFarland E, Kieff E (2006) LMP1 transmembrane domain 1 and 2 (TM1-2) FWLY mediates intermolecular interactions with TM3-6 to activate NF-kappaB. J Virol 80: 10787–10793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudt LM (2010) Oncogenic activation of NF-kappaB. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuffers S, Sem WC, Stenmark H, Brech A (2009) Multivesicular endosome biogenesis in the absence of ESCRTs. Traffic 10: 925–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]