Hypoxia Inducible Factors: Central Regulators of the Tumor Phenotype (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2011 Nov 14.

Published in final edited form as: Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007 Jan 8;17(1):71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.006

Abstract

Low oxygen levels are a defining characteristic of solid tumors, and responses to hypoxia contribute substantially to the malignant phenotype. Hypoxia-induced gene transcription promotes characteristic tumor behaviors including angiogenesis, invasion, metastasis, de-differentiation and enhanced glycolytic metabolism. These effects are mediated, at least in part, by targets of the Hypoxia Inducible Factors (HIFs). The HIFs function as heterodimers, made up of an oxygen-labile α-subunit and a stable (β-subunit, also referred to as ARNT. HIF-1α and HIF-2α stimulate the expression of overlapping as well as unique transcriptional targets, and their induction can have distinct biological effects. New targets and novel mechanisms of dysregulation place the HIFs in an ever more central role in tumor biology, and have led to development of pharmacological inhibitors of their activity.

Introduction

Hypoxia occurs when available oxygen falls below 5%, triggering a complex cellular and systemic adaptation mediated primarily through HIF transcription. HIF-1α was first identified as a critical regulator of erythropoietin expression in response to low oxygen [1]. HIF-2α and HIF-3α have also been described, with HIF-3α (also known as IPAS) functioning as an inhibitor of transcription [2,3]. More than 100 HIF targets have been identified in a variety of systems. These include promoters of angiogenesis, such as Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and Platelet Derived Growth Factor, glycolytic enzymes such as Aldolase A and Phosphoglycerate Kinase, and cell cycle regulators such as p21 and p27, as well as genes involved in extracellular matrix remodeling, differentiation and apoptosis [4–7]. HIF-1α and HIF-2α bind hypoxia response elements (HREs) in a complex with the (β-subunits, ARNT and (more rarely) ARNT2 [8,9]. The biological significance and transcriptional effects of HIF-3α remain somewhat obscure, and only HIF-1α and HIF-2α will be discussed further in this review.

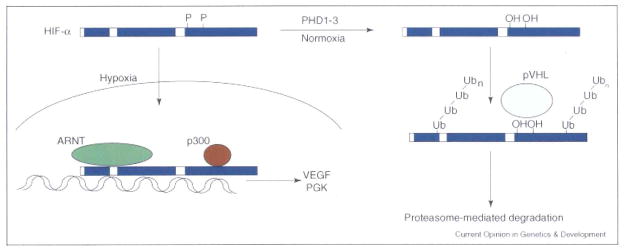

HIF-α subunits are continuously transcribed and translated, and their stability is regulated by oxygen availability. Under normoxic conditions, two prolines (402 and 564 in human HIF-1α and 405 and 531 in human HIF-2α) in the HIF-α oxygen-dependant degradation domain (ODD) are hydroxylated by a family of oxygen dependant proline hydroxylases (PHD1–3) [10–13], allowing binding and ubiquitylation by the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor, a component of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex [14]. HIF-α interaction with the transcriptional co-activator p300 is also regulated by oxygen levels, with binding inhibited by oxygen-dependent asparaginyl hydroxylation (asparagines 803 in human HIF-1α and 851 in human HIF-2α) of the HIF transactivation domain by Factor Inhibiting HIF (FIH) [15,16].

VHL disease is a hereditary cancer syndrome marked by clear cell renal carcinoma (RCC), pheochromocytoma, and hemangioblastoma. The VHL tumor suppressor protein (pVHL) is required for normoxic degradation of the HIF-α subunits and can also target atypical protein kinase C λ and some subunits of RNA polymerase for degradation [17]. Of the _VHL_-associated malignancies, RCC and hemangioblastoma result from normoxic HIF-2α stabilization [18–21], whereas pheochromocytoma results from a HIF-independent effect of pVHL on JunB [22]. The HIFs also play an important role in non-inherited malignancies. There is substantial clinical data associating HIF-α protein expression with poor outcomes in patients with a broad range of sporadic cancers. These include adenocarcinoma of the breast, lung, and GI tract, as well as CNS malignancies and squamous cell tumors of the cervix and head and neck [5]. Data from mouse allograft studies have been less consistent. In some cases, disruption of Hif-1α inhibited allograft growth [23,24], but in others it promoted it [25,26]. Consistent inhibition of tumor growth has been observed following normoxic stabilization of HIF-1α due to Vhl loss [20,27–29] and the overexpression of HIF-1α or HIF-2α in glioma [25,30].

Regulation of HIF Stability and Expression

The normoxic degradation of the HIF-α subunits is well characterized, but its inhibition under hypoxia is an area of active investigation, and remains controversial. As oxygen is required for hydroxylation, it is a limiting substrate under anoxic (0% O2) conditions. However, HIF-α’s are stabilized in a reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent fashion well above this threshold. Early evidence showed that inhibitors of mitochondrial ROS generation were able to block hypoxic HIF-α stabilization [31]. However, such drugs may have toxic or off target effects on HIF-α regulation. It has also been suggested that these drugs may cause redistribution of oxygen away from the mitochondrion, leaving more available for PHD activity and thus maintaining it under moderate hypoxia [32,33]. However, genetic studies have shown that disruption of electron transport chain (ETC) Complex III, cytochrome c and Rieske iron-sulfur protein also block hypoxic HIF stabilization [34,35], while disruption of ETC Complex IV did not [36]. These data suggest that respiration is not required for HIF-α stabilization but the delivery of electrons to cytochrome c is, supporting a requirement for ROS (but not oxygen consumption) in hypoxic HIF-α stabilization. Further evidence comes from the analysis of junD−/− mice, which show enhanced ROS production and normoxic HIF-α expression. In this case, enhanced intracellular H2O2 levels were shown to inhibit PHD activity by altering the reduction of Fe3+ to Fe2+, which is required for PHD activity [37]. This is also a plausible mechanism for PHD regulation in hypoxic cells.

Normoxic HIF-α stabilization is both necessary and sufficient for RCC development following VHL inactivation. pVHL can also be inhibited by the E2-EPF ubiquitin carrier protein, which targets pVHL for proteasome mediated degradation [38]. Overexpression of this protein occurs in breast, lung, ovarian and CNS cancers, and correlates strongly with tumor grade and poor patient outcomes [39]. The alteration of metabolic pathways impinging on PHD activity can also promote normoxic HIF-α stabilization and tumor formation. In addition to oxygen and Fe2+, the PHDs require 2-oxoglutarate as a substrate and ascorbic acid as a co-factor to catalyze HIF-α hydroxylation, and produce succinate and carbon dioxide in addition to hydroxylated proline residues. Inactivation of fumarate hydratase, a rare cause of inherited RCC, promotes HIF-α stabilization due to inhibition of the PHDs by fumarate, which competes with 2-oxoglutarate for active site binding [40]. Similarly, inactivation of succinate dehydrogenase, which occurs in some renal, thyroid and colon cancers, leads to succinate accumulation and product inhibition of the PHDs [41].

Control of HIF-α translation

The mTOR kinase responds to nutrient and growth factor availability to regulate translation. Normoxic HIF-α expression is promoted by disruption of mTOR regulation, resulting from increased HIF-α translation rates despite unaltered levels of degradation. This is likely to occur in many tumors which show hyperactivation of receptor tyrosine kinases, and thus translation [42], but is also seen in several inherited tumor syndromes. Loss of the TSC2 tumor suppressor gene, an inhibitor of mTOR activity, causes normoxic stabilization of the HIF-α subunits by enhancing their translation rate, leading to the formation of highly vascular tumors [43]. Enhancement of HIF-α translation under hypoxia by disruption of the promyelocytic leukemia tumor suppressor (PML) can also promote tumor growth. Originally identified as part of a leukemogenic fusion protein, PML has since been appreciated to have a tumor suppressive effect, and is lost in multiple sporadic tumors [44]. Genetic disruption of Pml correlates with increased VEGF and HIF-α expression through attenuation of the hypoxic inhibition of mTOR, normally effected by the sequestration of mTOR in PML containing nuclear subdomains [45]. Thus, the regulation of HIF-α translation is likely to have a contributing role in a broad range of tumor types.

HIF-1α vs. HIF-2α

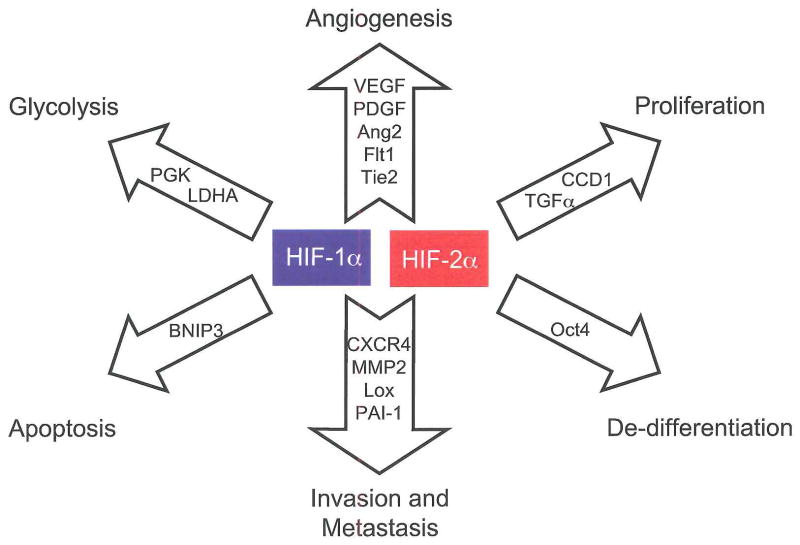

Discovered first and expressed ubiquitously, HIF-1α is by far the best characterized α-subunit. HIF-2α expression is limited to endothelium, kidney, heart, lung and gastrointestinal epithelium, and some cells of the CNS [3,46,47]. Differences exist in their targets, with HIF-1α uniquely activating glycolytic enzyme genes and HIF-2α preferentially activating VEGF, transforming growth factor-α (TGFα), lysyl oxidase, Oct4 and Cyclin D1 [7,48–52]. Similarly, the effects of Hif-1α and Hif-2α gene disruption are substantially different, with Hif-1α knockout leading to impaired cardiac and vascular development and E10.5 lethality [23,26,53] while Hif-2α loss leads to a broad range of phenotypes including embryonic lethality due to bradycardia and vascular defects, perinatal lethality due to impaired lung maturation, and embryonic and post-natal lethality caused by multi-organ failure and mitochondrial dysfunction [54–57].

Differences in gene targets and knockout phenotypes suggest that HIF-2α may promote a distinct phenotype in tumors expressing it. This has been observed in CNS, colorectal, non-small cell lung and head and neck tumors, where expression of HIF-2α is more strongly associated with poor patient outcomes than expression of HIF-1α [5,58]. Data from genetic models suggest that HIF-2α may preferentially promote tumorigenesis, where ES cell derived teratomas with HIF-2α “knocked in” to the Hif-1α locus exhibiting a four-fold increase in mass over HIF-1α expressing controls, largely due to increased proliferation [59]. Enhanced proliferation likely results from increased expression of TGFα and Cyclin Dl. Additional effects on the tumor phenotype may result from HIF-2α mediated induction of the stem cell factor Oct4 and activation of c-Myc transcription, as described below [49,60].

HIF transcriptional targets

A series of microarray studies have defined HIF target gene families [6,7,50,61–64]. Erythropoeisis, angiogenesis, and glycolytic metabolism are controlled through multiple gene targets, with differential activation based on cell type and which HIF-α subunit is expressed. Continued analysis is expanding our understanding of how some of these responses are mediated. HIF-1α induction of glycolytic metabolism has been well appreciated, but the inhibition of aerobic metabolism through the induction of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK1) was only recently described. PDK1 phosphorylates pyruvate dehydrogenase, inhibiting the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA. The inhibition of aerobic metabolism at moderate levels of hypoxia may free limited oxygen supplies for other cellular processes and avoid the accumulation of toxic metabolites [65,66].

Metastasis is a defining characteristic of cancer, and is also promoted by tumor hypoxia. Metastasis is a coordinated process, where chemokines direct cell migration, adhesion molecules mediate attachment in distant organs, and proteases and other secreted enzymes degrade or alter the extracellular matrix. Studies in breast cancer and RCC demonstrated that the chemokine receptor CXCR4, a major metastatic mediator, is upregulated by HIF [67], while analysis of lung epithelium further showed matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) 2 and 9 are regulated by hypoxia [68]. Another key mediator of metastasis is the HIF target lysyl oxidase, which is strongly associated with hypoxia and poor patient outcome in several tumor types. Lysyl oxidase alters extracellular matrix components such as elastin and collagen and its inhibition blocks in vitro migration and in vivo metastasis from subcutaneous xenografts or after tail vein injection [52].

HIF targets known to be important in development also have a substantial role in tumor biology. Oct4, a POU-domain transcription factor and HIF-2α target, is a key regulator of stem cell behavior. Well known for a role in embryonic stem cells, Oct4 has more recently been observed in some adult stem cell populations [69]. In studies of a knock-in model where HIF-2α was expressed from the Hif-1α promoter, a dramatic disruption of embryonic development was observed, correlating with an enhancement of TGF-α, VEGF and Oct4 expression. In vitro models of these developmental phenotypes were mostly reversed by shRNA knockdown of Oct4 [49]. Interestingly, Oct4 knockdown also substantially reversed the growth advantage seen in subcutaneous teratomas derived from the knock-in ES cells compared to teratomas from Hif-1α WT ES cells [49]. The mechanism by which Oct4 modulates tumor behavior is not yet clear, but one intriguing possibility is that it promotes the growth of a ‘cancer stem cell’ population, and thus self-renewal and chemotherapy resistance.

In addition to its direct gene targets, HIF can regulate the transcription factors Notch and c-Myc [70,71]. HIF-1α was found to require Notch and its target genes in models of hypoxia-induced muscle and neural cell de-differentiation. In fact, HIF-1α interacts directly with the intracellular domain of Notch1, increasing its half-life and transcriptional activity [72]. The in vivo implications of this interaction remain to be understood, but given Notch’s role in development and tumor biology they are likely to be significant [73]. The implications of HIF-1α inhibition of c-Myc are somewhat clearer. Though HIF-1α has long been connected with cell cycle arrest, the mechanism by which this occurs has not been well understood. HIF-1α directly inhibits c-Myc, causing de-repression of its targets p21 and p27 [70]. c-Myc targets involved in mismatch repair are also modulated by HIF-1α, suggested a role for HIF in hypoxia induced genetic instability [71]. In assessing the effects of HIF-2α on c-Myc, we have observed that HIF-2α promotes c-Myc transcriptional activity, which may also contribute to HIF-2α mediated tumor progression [60].

HIF and Cancer Therapy

Pharmacologic inhibition of the HIF target VEGF has proven efficacy as a cancer therapeutic [74], and has generated interest in targeting global HIF activity. Direct approaches, such as inhibition of p300-mediated co-activation [75] and DNA binding [76], are being explored as is HIF inhibition through repression of its translation. HIF-α subunits appear to be particularly sensitive to translational regulation as the use of pharmacological mTOR inhibitors can block HIF-α expression even following VHL loss [77]. In fact, the mTOR inhibitor CCI-779 resulted in a statistically significant survival advantage in patients with metastatic renal cancer [78].

Mouse models have shown that HIF can have a substantial impact on the response to cytotoxic cancer therapies. Ionizing radiation (IR) treatment in subcutaneous tumor models causes HIF-1α stabilization through ROS induction. HIF-1α induction leads to release of cytokines including VEGF that promote endothelial cell survival, and thus blunt the therapeutic effect of IR [79]. The stabilization of HIF-1α in endothelial cells is also likely to occur following IR, and can substantially promote tumor growth [80]. On the other hand, HIF-1α enhances the effect of IR on tumor cells themselves. In a similar model, induction of HIF-1α promotes p53 phosphorylation and stabilization, as well as cell death following IR. These effects, combined with HIF effects on the endothelium, suggest a particular advantage to combination treatments using IR followed at a later point by HIF inhibition [81]. Thus, the inhibition of the HIFs, either at the level of protein expression or transcriptional activity, should be consider on a case-by-case basis, depending on tumor type and other therapies used concurrently.

Conclusion

In addition to important roles in development, hematopoeisis, and ischemic disease the HIFs also have a broad range of effects on tumor biology. They are directly responsible for tumor angiogenesis and metastasis, and contribute substantially to metabolic changes, the evasion of apoptosis, and genomic instability. Despite the appreciation of their relevance to tumor biology, novel targets and mechanisms are reported frequently. Their pharmacological inhibition represents an opportunity and a challenge, and an important area for future study.

Figure 1. HIF-1α and HIF-2α activate overlapping but distinct genes.

HIF-1α and HIF-2α share the regulation of target genes involved in angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis, while HIF-1α alone activates genes involved in glycolysis and apoptosis. HIF-2α uniquely activates the stem cell factor Oct4 and Cyclin D1, while it preferentially regulates the growth factor TGFα. Abbreviations: Platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), fms- related tyrosine kinase 1 (Flt1), Tunica internal endothelial cell kinase 2 (Tie2), Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1), Lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19kDa interacting protein 3 (BNIP3), Cyclin D1 (CCD1).

Figure 2.

Regulation of HIF-α stability: continuously transcribed and translated, the HIF-α subunits are degraded under normoxic conditions. Two prolines in the ODD are hydroxylated by PHD1, 2 or 3, allowing recognition by an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex including the VHL tumor suppressor protein. Following pVHL-mediated ubiquitylation, the HIF-α subunits are degraded in a proteasome-dependent fashion. When oxygen levels fall below ~5%, the PHDs are no longer active and the HIF-α subunits can translocate to the nucleus, where they bind co-factors including ARNT and p300 and transactivate hypoxia response genes, such as VEGF and PGK.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This PDF receipt will only be used as the basis for generating PubMed Central (PMC) documents. PMC documents will be made available for review after conversion (approx. 2–3 weeks time). Any corrections that need to be made will be done at that time. No materials will be released to PMC without the approval of an author. Only the PMC documents will appear on PubMed Central -- this PDF Receipt will not appear on PubMed Central.

References

- 1.Wang GL, Semenza GL. Purification and characterization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1230–1237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makino Y, Cao R, Svensson K, Bertilsson G, Asman M, Tanaka H, Cao Y, Berkenstam A, Poellinger L. Inhibitory PAS domain protein is a negative regulator of hypoxia-inducible gene expression. Nature. 2001;414:550–554. doi: 10.1038/35107085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tian H, McKnight SL, Russell DW. Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 (EPAS1), a transcription factor selectively expressed in endothelial cells. Genes Dev. 1997;11:72–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Regulation of angiogenesis by hypoxia: role of the HIF system. Nat Med. 2003;9:677–684. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu CJ, Iyer S, Sataur A, Covello KL, Chodosh LA, Simon MC. Differential regulation of the transcriptional activities of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1alpha) and HIF-2alpha in stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3514–3526. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3514-3526.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu CJ, Wang LY, Chodosh LA, Keith B, Simon MC. Differential roles of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) and HIF-2alpha in hypoxic gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:9361–9374. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9361-9374.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maltepe E, Schmidt JV, Baunoch D, Bradfield CA, Simon MC. Abnormal angiogenesis and responses to glucose and oxygen deprivation in mice lacking the protein ARNT. Nature. 1997;386:403–407. doi: 10.1038/386403a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keith B, Adelman DM, Simon MC. Targeted mutation of the murine arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator 2 (Arnt2) gene reveals partial redundancy with Arnt. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6692–6697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121494298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epstein AC, Gleadle JM, McNeill LA, Hewitson KS, O’Rourke J, Mole DR, Mukherji M, Metzen E, Wilson MI, Dhanda A, et al. C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell. 2001;107:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI, Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, Kriegsheim A, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji M, Schofield CJ, et al. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science. 2001;292:468–472. doi: 10.1126/science.1059796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruick RK, McKnight SL. A conserved family of prolyl-4-hydroxylases that modify HIF. Science. 2001;294:1337–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1066373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu F, White SB, Zhao Q, Lee FS. HIF-1alpha binding to VHL is regulated by stimulus-sensitive proline hydroxylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9630–9635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181341498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, Clifford SC, Vaux EC, Cockman ME, Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maher ER, Ratcliffe PJ. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature. 1999;399:271–275. doi: 10.1038/20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahon PC, Hirota K, Semenza GL. FIH-1: a novel protein that interacts with HIF-1alpha and VHL to mediate repression of HIF-1 transcriptional activity. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2675–2686. doi: 10.1101/gad.924501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lando D, Peet DJ, Gorman JJ, Whelan DA, Whitelaw ML, Bruick RK. FIH-1 is an asparaginyl hydroxylase enzyme that regulates the transcriptional activity of hypoxia-inducible factor. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1466–1471. doi: 10.1101/gad.991402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim WY, Kaelin WG. Role of VHL gene mutation in human cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4991–5004. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18*.Kondo K, Kim WY, Lechpammer M, Kaelin WG., Jr Inhibition of HIF2alpha is sufficient to suppress pVHL-defective tumor growth. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E83. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000083. Expanding on a previous study showing a role for HIF-2α in VHL−/− RCC, Kondo and colleagues provide definitive evidence that normoxic stabilization of HIF-2α and it’s transcriptional activity are required for RCC in VHL disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kondo K, Klco J, Nakamura E, Lechpammer M, Kaelin WG., Jr Inhibition of HIF is necessary for tumor suppression by the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:237–246. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maranchie JK, Vasselli JR, Riss J, Bonifacino JS, Linehan WM, Klausner RD. The contribution of VHL substrate binding and HIF1-alpha to the phenotype of VHL loss in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:247–255. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rankin EB, Higgins DF, Walisser JA, Johnson RS, Bradfield CA, Haase VH. Inactivation of the arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (Arnt) suppresses von Hippel-Lindau disease-associated vascular tumors in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3163–3172. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.8.3163-3172.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22*.Lee S, Nakamura E, Yang H, Wei W, Linggi MS, Sajan MP, Farese RV, Freeman RS, Carter BD, Kaelin WG, Jr, et al. Neuronal apoptosis linked to EglN3 prolyl hydroxylase and familial pheochromocytoma genes: developmental culling and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.015. In this paper, a novel, HIF-independent mechanism for VHL-disease associated pheochromocytoma is described. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan HE, Lo J, Johnson RS. HIF-1 alpha is required for solid tumor formation and embryonic vascularization. Embo J. 1998;17:3005–3015. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan HE, Poloni M, McNulty W, Elson D, Gassmann M, Arbeit JM, Johnson RS. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha is a positive factor in solid tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4010–4015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Acker T, Diez-Juan A, Aragones J, Tjwa M, Brusselmans K, Moons L, Fukumura D, Moreno-Murciano MP, Herbert JM, Burger A, et al. Genetic evidence for a tumor suppressor role of HIF-2alpha. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carmeliet P, Dor Y, Herbert JM, Fukumura D, Brusselmans K, Dewerchin M, Neeman M, Bono F, Abramovitch R, Maxwell P, et al. Role of HIF-1alpha in hypoxia-mediated apoptosis, cell proliferation and tumour angiogenesis. Nature. 1998;394:485–490. doi: 10.1038/28867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mack FA, Patel JH, Biju MP, Haase VH, Simon MC. Decreased growth of Vhl−/− fibrosarcomas is associated with elevated levels of cyclin kinase inhibitors p21 and p27. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4565–4578. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4565-4578.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mack FA, Rathmell WK, Arsham AM, Gnarra J, Keith B, Simon MC. Loss of pVHL is sufficient to cause HIF dysregulation in primary cells but does not promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:75–88. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00240-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raval RJR, Lau KW, Tran MG, Sowter HM, Mandriota SJ, Li JL, Pugh CW, Maxwell PH, Harris AL, Ratcliffe PJ. Contrasting properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5675–5686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5675-5686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blouw B, Song H, Tihan T, Bosze J, Ferrara N, Gerber HP, Johnson RS, Bergers G. The hypoxic response of tumors is dependent on their microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:133–146. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chandel NS, Maltepe E, Goldwasser E, Mathieu CE, Simon MC, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species trigger hypoxia-induced transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11715–11720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagen T, Taylor CT, Lam F, Moncada S. Redistribution of intracellular oxygen in hypoxia by nitric oxide: effect on HIF1alpha. Science. 2003;302:1975–1978. doi: 10.1126/science.1088805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaux EC, Metzen E, Yeates KM, Ratcliffe PJ. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor is preserved in the absence of a functioning mitochondrial respiratory chain. Blood. 2001;98:296–302. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34*.Mansfield KD, Guzy RD, Pan Y, Young RM, Cash TP, Schumacker PT, Simon MC. Mitochondrial dysfunction resulting from loss of cytochrome c impairs cellular oxygen sensing and hypoxic HIF-alpha activation. Cell Metab. 2005;1:393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.003. In a comprehensive series of murine and patient derived genetic models, the authors show a requirement for ROS in hypoxic HIF-α stabilization. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35*.Guzy RD, Hoyos B, Robin E, Chen H, Liu L, Mansfield KD, Simon MC, Hammerling U, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial complex III is required for hypoxia-induced ROS production and cellular oxygen sensing. Cell Metab. 2005;1:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.001. In a comprehensive series of murine and patient derived genetic models, the authors show a requirement for ROS in hypoxic HIF-α stabilization. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36*.Brunelle JK, Bell EL, Quesada NM, Vercauteren K, Tiranti V, Zeviani M, Scarpulla RC, Chandel NS. Oxygen sensing requires mitochondrial ROS but not oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 2005;1:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.002. In a comprehensive series of murine and patient derived genetic models, the authors show a requirement for ROS in hypoxic HIF-α stabilization. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37*.Gerald D, Berra E, Frapart YM, Chan DA, Giaccia AJ, Mansuy D, Pouyssegur J, Yaniv M, Mechta-Grigoriou F. JunD reduces tumor angiogenesis by protecting cells from oxidative stress. Cell. 2004;118:781–794. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.025. Here, junD−/− mice are analyzed, showing a substantial accumulation or ROS, resulting in hypoxic HIF-α stabilization. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38**.Jung CR, Hwang KS, Yoo J, Cho WK, Kim JM, Kim WH, Im DS. E2-EPF UCP targets pVHL for degradation and associates with tumor growth and metastasis. Nat Med. 2006;12:809–816. doi: 10.1038/nm1440. E2-EPF UCP is characterized as a novel upstream regulator of pVHL stability, identifying a mechanism of HIF upregulation that is likely to be important in multiple tumor types. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner KW, Sapinoso LM, El-Rifai W, Frierson HF, Butz N, Mestan J, Hofmann F, Deveraux QL, Hampton GM. Overexpression, genomic amplification and therapeutic potential of inhibiting the UbcH10 ubiquitin conjugase in human carcinomas of diverse anatomic origin. Oncogene. 2004;23:6621–6629. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Isaacs JS, Jung YJ, Mole DR, Lee S, Torres-Cabala C, Chung YL, Merino M, Trepel J, Zbar B, Toro J, et al. HIF overexpression correlates with biallelic loss of fumarate hydratase in renal cancer: novel role of fumarate in regulation of HIF stability. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Selak MA, Armour SM, MacKenzie ED, Boulahbel H, Watson DG, Mansfield KD, Pan Y, Simon MC, Thompson CB, Gottlieb E. Succinate links TCA cycle dysfunction to oncogenesis by inhibiting HIF-alpha prolyl hydroxylase. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhong H, Chiles K, Feldser D, Laughner E, Hanrahan C, Georgescu MM, Simons JW, Semenza GL. Modulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha expression by the epidermal growth factor/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PTEN/AKT/FRAP pathway in human prostate cancer cells: implications for tumor angiogenesis and therapeutics. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1541–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brugarolas JB, Vazquez F, Reddy A, Sellers WR, Kaelin WG., Jr TSC2 regulates VEGF through mTOR-dependent and -independent pathways. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:147–158. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koken MH, Linares-Cruz G, Quignon F, Viron A, Chelbi-Alix MK, Sobczak-Thepot J, Juhlin L, Degos L, Calvo F, de The H. The PML growth-suppressor has an altered expression in human oncogenesis. Oncogene. 1995;10:1315–1324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45**.Bernardi R, Guernah I, Jin D, Grisendi S, Alimonti A, Teruya-Feldstein J, Cordon-Cardo C, Simon MC, Rafii S, Pandolfi PP. PML inhibits HIF-1alpha translation and neoangiogenesis through repression of mTOR. Nature. 2006;442:779–785. doi: 10.1038/nature05029. Identifying PML as a regulator of mTor and thus HIF-α expression under hypoxia, the authors provide mechanistic insight into translational control and an important tumor suppressor. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiesener MS, Jurgensen JS, Rosenberger C, Scholze CK, Horstrup JH, Warnecke C, Mandriota S, Bechmann I, Frei UA, Pugh CW, et al. Widespread hypoxia-inducible expression of HIF-2alpha in distinct cell populations of different organs. Faseb J. 2003;17:271–273. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0445fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ema M, Taya S, Yokotani N, Sogawa K, Matsuda Y, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. A novel bHLH-PAS factor with close sequence similarity to hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha regulates the VEGF expression and is potentially involved in lung and vascular development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4273–4278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gunaratnam L, Morley M, Franovic A, de Paulsen N, Mekhail K, Parolin DA, Nakamura E, Lorimer IA, Lee S. Hypoxia inducible factor activates the transforming growth factor-alpha/epidermal growth factor receptor growth stimulatory pathway in VHL(−/−) renal cell carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44966–44974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305502200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49**.Covello KL, Kehler J, Yu H, Gordan JD, Arsham AM, Hu CJ, Labosky PA, Simon MC, Keith B. HIF-2alpha regulates Oct-4: effects of hypoxia on stem cell function, embryonic development, and tumor growth. Genes Dev. 2006;20:557–570. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399906. By identifying and characterizing HIF-2α effects on Oct4, Covello and colleagues show a novel and unique role for HIF-2α in embryonic development, adult stem cell biology and tumor behavior. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang V, Davis DA, Haque M, Huang LE, Yarchoan R. Differential gene up-regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha in HEK293T cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3299–3306. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baba M, Hirai S, Yamada-Okabe H, Hamada K, Tabuchi H, Kobayashi K, Kondo K, Yoshida M, Yamashita A, Kishida T, et al. Loss of von Hippel-Lindau protein causes cell density dependent deregulation of CyclinD1 expression through hypoxia-inducible factor. Oncogene. 2003;22:2728–2738. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52*.Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Nicolau M, Dornhofer N, Kong C, Le QT, Chi JT, Jeffrey SS, Giaccia AJ. Lysyl oxidase is essential for hypoxia-induced metastasis. Nature. 2006;440:1222–1226. doi: 10.1038/nature04695. In a study utilizing primary patient samples and knockout mice, an essential role in metastasis is described for the HIF target lysyl oxidase. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iyer NV, Kotch LE, Agani F, Leung SW, Laughner E, Wenger RH, Gassmann M, Gearhart JD, Lawler AM, Yu AY, et al. Cellular and developmental control of O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Genes Dev. 1998;12:149–162. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Comperaolle V, Brusselmans K, Acker T, Hoet P, Tjwa M, Beck H, Plaisance S, Dor Y, Keshet E, Lupu F, et al. Loss of HIF-2alpha and inhibition of VEGF impair fetal lung maturation, whereas treatment with VEGF prevents fatal respiratory distress in premature mice. Nat Med. 2002;8:702–710. doi: 10.1038/nm721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55*.Scortegagna M, Ding K, Oktay Y, Gaur A, Thurmond F, Yan LJ, Marck BT, Matsumoto AM, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, et al. Multiple organ pathology, metabolic abnormalities and impaired homeostasis of reactive oxygen species in Epas1−/− mice. Nat Genet. 2003;35:331–340. doi: 10.1038/ng1266. Addressing strain differences in the multiple Hif-2α knockout mice generated to date, the authors identify a new role for HlF-2α in ROS metabolism. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tian H, Hammer RE, Matsumoto AM, Russell DW, McKnight SL. The hypoxia-responsive transcription factor EPAS1 is essential for catecholamine homeostasis and protection against heart failure during embryonic development. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3320–3324. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peng J, Zhang L, Drysdale L, Fong GH. The transcription factor EPAS-1/hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha plays an important role in vascular remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8386–8391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140087397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoshimura H, Dhar DK, Kohno H, Kubota H, Fujii T, Ueda S, Kinugasa S, Tachibana M, Nagasue N. Prognostic impact of hypoxia-inducible factors 1alpha and 2alpha in colorectal cancer patients: correlation with tumor angiogenesis and cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8554–8560. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0946-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Covello KL, Simon MC, Keith B. Targeted replacement of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha by a hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha knock-in allele promotes tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2277–2286. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gordan JD, Bertout JA, Hu CJ, Diehl JA, Simon MC. HIF-2alpha promotes hypoxic cell proliferation by enhancing c-Myc transcriptional activity. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Denko NC, Fontana LA, Hudson KM, Sutphin PD, Raychaudhuri S, Altman R, Giaccia AJ. Investigating hypoxic tumor physiology through gene expression patterns. Oncogene. 2003;22:5907–5914. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maina EN, Morris MR, Zatyka M, Raval RR, Banks RE, Richards FM, Johnson CM, Maher ER. Identification of novel VHL target genes and relationship to hypoxic response pathways. Oncogene. 2005;24:4549–4558. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takeda N, Maemura K, Imai Y, Harada T, Kawanami D, Nojiri T, Manabe I, Nagai R. Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 gene promotes angiogenesis through the transactivation of both vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, Flt-1. Circ Res. 2004;95:146–153. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000134920.10128.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chi JT, Wang Z, Nuyten DS, Rodriguez EH, Schaner ME, Salim A, Wang Y, Kristensen GB, Helland A, Borresen-Dale AL, et al. Gene Expression Programs in Response to Hypoxia: Cell Type Specificity and Prognostic Significance in Human Cancers. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e47. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65*.Kim JW, Tchernyshyov I, Semenza GL, Dang CV. HlF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab. 2006;3:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.002. In identifying pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase as a HIF- 1α target, the authors describe the mechanism whereby HIF inhibits aerobic metabolism under hypoxia, limiting oxygen consumption and ROS production. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66*.Papandreou I, Cairns RA, Fontana L, Lim AL, Denko NC. HIF-1 mediates adaptation to hypoxia by actively downregulating mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Cell Metab. 2006;3:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.012. In identifying pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase as a HIF- 1α target, the authors describe the mechanism whereby HIF inhibits aerobic metabolism under hypoxia, limiting oxygen consumption and ROS production. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Staller P, Sulitkova J, Lisztwan J, Moch H, Oakeley EJ, Krek W. Chemokine receptor CXCR4 downregulated by von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor pVHL. Nature. 2003;425:307–311. doi: 10.1038/nature01874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leufgen H, Bihl MP, Rudiger JJ, Gambazzi J, Perruchoud AP, Tamm M, Roth M. Collagenase expression and activity is modulated by the interaction of collagen types, hypoxia, and nutrition in human lung cells. J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:146–154. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tai MH, Chang CC, Kiupel M, Webster JD, Olson LK, Trosko JE. Oct4 expression in adult human stem cells: evidence in support of the stem cell theory of carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:495–502. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70**.Koshiji M, Kageyama Y, Pete EA, Horikawa I, Barrett JC, Huang LE. inF-1alpha induces cell cycle arrest by functionally counteracting Myc. Embo J. 2004;23:1949–1956. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600196. This article, and one the following year by the same group, shows an important role for HIF-1α in modulating the activity of the c-Myc proto-oncogene. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koshiji M, To KK, Hammer S, Kumamoto K, Harris AL, Modrich P, Huang LE. HIF-1alpha induces genetic instability by transcriptionally downregulating MutSalpha expression. Mol Cell. 2005;17:793–803. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72**.Gustafsson MV, Zheng X, Pereira T, Gradin K, Jin S, Lundkvist J, Ruas JL, Poellinger L, Lendahl U, Bondesson M. Hypoxia requires notch signaling to maintain the undifferentiated cell state. Dev Cell. 2005;9:617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.010. Here, Gustaffson and colleagues describe an important new mechanism for HIF-a effects on development. By modulating Notch activity, the HIF-α subunits can promote or block differentiation in a context dependent fashion. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wilson A, Radtke F. Multiple functions of Notch signaling in self-renewing organs and cancer. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2860–2868. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gasparini G, Longo R, Toi M, Ferrara N. Angiogenic inhibitors: a new therapeutic strategy in oncology. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2:562–577. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kung AL, Zabludoff SD, France DS, Freedman SJ, Tanner EA, Vieira A, Cornell-Kennon S, Lee J, Wang B, Wang J, et al. Small molecule blockade of transcriptional coactivation of the hypoxia-inducible factor pathway. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kong D, Park EJ, Stephen AG, Calvani M, Cardellina JH, Monks A, Fisher RJ, Shoemaker RH, Melillo G. Echinomycin, a small-molecule inhibitor of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 DNA-binding activity. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9047–9055. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thomas GV, Tran C, Mellinghoff IK, Welsbie DS, Chan E, Fueger B, Czemin J, Sawyers CL. Hypoxia-inducible factor determines sensitivity to inhibitors of mTOR in kidney cancer. Nat Med. 2006;12:122–127. doi: 10.1038/nm1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Atkins MB, Hidalgo M, Stadler WM, Logan TF, Dutcher JP, Hudes GR, Park Y, Liou SH, Marshall B, Boni JP, et al. Randomized phase II study of multiple dose levels of CCI-779, a novel mammalian target of rapamycin kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced refractory renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:909–918. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moeller BJ, Cao Y, Li CY, Dewhirst MW. Radiation activates HIF-1 to regulate vascular radiosensitivity in tumors: role of reoxygenation, free radicals, and stress granules. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:429–441. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80*.Tang N, Wang L, Esko J, Giordano FJ, Huang Y, Gerber HP, Ferrara N, Johnson RS. Loss of HIF-1alpha in endothelial cells disrupts a hypoxia-driven VEGF autocrine loop necessary for tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.026. With cre-loxP mediated deletion of HIF-1α from endothelial cells, Tang and colleagues show that HIF-1α expression in endothelial cells is key in tumor vascularization. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81*.Moeller BJ, Dreher MR, Rabbani ZN, Schroeder T, Cao Y, Li CY, Dewhirst MW. Pleiotropic effects of HIF-1 blockade on tumor radiosensitivity. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.016. This study shows a new role for HIF-1α in tumor biology, showing that it substantially promotes p53 activity and cell death following ionizing radiation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]