Distribution and storage of inflammatory memory in barrier tissues (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2020 Nov 1.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Rev Immunol. 2020 Feb 3;20(5):308–320. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0263-z

Abstract

Memories of previous immune events enable barrier tissues to rapidly recall distinct environmental exposures. To effectively inform future responses, these past experiences can be stored in cell types that reside long-term in tissues or are essential constituents of tissues. There is an emerging understanding that in addition to antigen-specific immune cells, diverse haematopoietic, stromal, parenchymal and neuronal cell types can store inflammatory memory. Here, we explore the impact of previous immune activity on various cell lineages with the goal of presenting a unified view of inflammatory memory to environmental exposures (such as allergens, antigens, noxious agents and microorganisms) at barrier tissues. We propose that inflammatory memory is distributed across diverse cell types, stored through shifts in cell states, and we provide a framework to guide future experiments. This distribution and storage may promote adaptation or maladaptation in homeostatic, maintenance and disease settings — especially if the distribution of memory potentiates cellular cooperation during storage or recall.

INTRODUCTION

The epithelial barriers of the skin, airways and intestines in mammals form essential interfaces that constantly sense and respond to external and internal signals1-3. Adaptation to environmental exposures is a conserved property of barrier tissues [G] , and the cell types that compose these barriers must balance metabolic functions with host defense4,5. In simpler metazoans that lack specialized immune cells, this function falls solely on epithelial cells, whereas in more cellularly complex mammalian tissues, immune cells may mediate this process5.

For a barrier tissue to optimally access information derived from a previous immune event [G] to inform a present or future memory [G] response, it can be stored in locally-accessible cell types that are residents or permanent residents and maintain appropriate qualitative features (Fig. 1). Deviations in memory storage or retrieval can predispose a tissue to pathological consequences: insufficient memory leads to increased infections, excessive memory retrieval drives chronic inflammation, and malignancy potentially arises from both insufficient and excessive memory6,7. The appropriately named adaptive immune system has key roles in promoting antigen-specific memory through encoding receptors — T cell receptors (TCRs) and B cell receptors (BCRs) — specific for microorganisms, environmental antigens and self-antigens in lymphocyte-bearing organisms8,9.

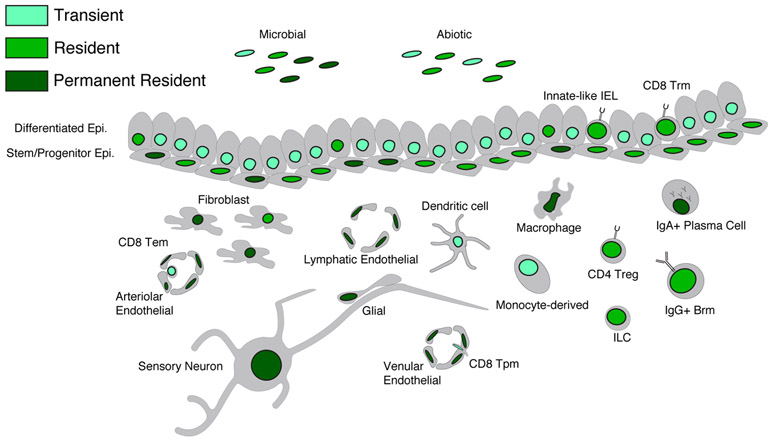

Figure 1 ∣. Cell type residence and permanence in barrier tissues.

The cell types in a tissue at any given moment may be there short-term (transient cells), have capacity to reside long-term in a tissue (resident cells) or be essential constituents (permanent resident cells). The fundamental permanent resident unit of a barrier tissue consists of epithelial stem cells and stromal cells (fibroblasts and endothelial cells). Other permanent resident cells include macrophages and sensory neurons. We acknowledge that there are specific cases where cell subsets that are typically transient (such as monocyte-derived mononuclear phagocytes) can acquire the characteristics of resident cells (such as Langerhans cells or macrophages) based on environmental perturbation and niche availability. Cell types that are non-essential to the fundamental tissue unit (plasma cells) can also exhibit characteristics of permanent residence. Moreover, microorganisms can also be permanent residents, residents or transient, and abiotic stimuli such as nutritional components can vary in “residence” based on the frequency and duration of environmental exposure.

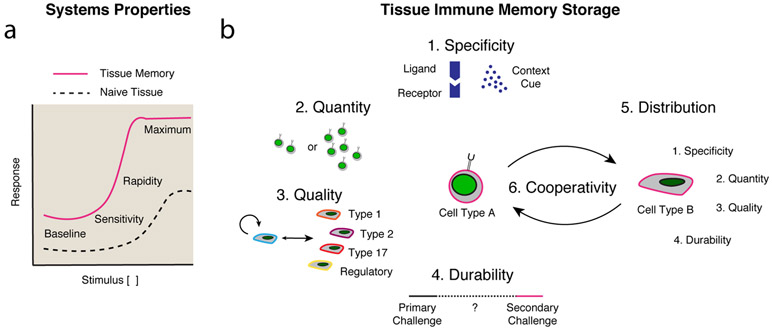

However, antigen-specific adaptive immune memory [G] is just one of the myriad ways in which tissues and organisms can adapt during immune events10. Indeed, the properties of memory are now being identified within other haematopoietic cells, such as innate immune cells, as well as more recently in the tissue parenchyma10-16. Here, we use the term memory to refer to a defined response to an initiating trigger that has altered baseline, maximum, rapidity or sensitivity, and that persists until a secondary challenge11 (Fig. 2a). Immunological, inflammatory and neuronal memory are all subject to independent environmental or host factors, including temperature, metabolism, hormones and circadian cycles, that may diminish or enhance a secondary response.

Figure 2 ∣. Properties of tissue inflammatory memory storage.

a ∣ The properties of memory to a stimulus include increases in baseline, sensitivity, rapidity or maximum response. Graphic adapted with permission from REF. 11 © Elsevier. b ∣ The discrete components of tissue inflammatory memory storage include specificity, quantity, quality (i.e. cell state), durability and distribution among various cell types. Cooperativity may exist across similar or distinct cell types, with each cell type being defined through its own discrete components.

The division of the adaptive immune system into cell types [G] (such as αβ and γδ T cells), cell subsets [G] (such as CD4+ and CD8+ T cells) and cell state [G] descriptors (such as type 1, type 2, type 17, circulating and resident-memory cells) has been invaluable in providing cellular mechanisms for the observed phenomena of tissue immunity17,18. Comprehensively identifying the sets of gene modules [G] that define the types, subsets and states of the main parenchymal, stromal, neuronal and immune cell lineages in barrier tissues will afford an unprecedented view of tissue immunity19. To date, this has been technically challenging given the lack of discrete markers for the prospective isolation of epithelial cells, stromal cells and some immune cells by subset and state, limiting our understanding to broad gene expression patterns within these subsets. However, recent advances in large scale single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) and epigenetic profiling are now enabling inquiries into the properties and adaptations of discrete cell subsets, as well as the relationships between them20-22 (Box 1).

Box 1 ∣. Techniques for measuring inflammatory memory.

Achieving a comprehensive understanding of the cell types and states that comprise a barrier tissue, and shifts thereto, has been technically challenging given a lack of discrete cell markers for prospective isolation. Recent advances in large scale single-cell RNA-sequencing20-22 now enable directed inquiries into human epithelial cell adaptation, as well as deep characterization of the cellular composition of barrier tissues. Coupling these methods with validated antibody panels173,174 will facilitate interpretation of gene expression in the context of established protein lineage markers. Further, deploying recently developed methods for assessing single-cell epigenetic features, such as chromatin accessibility, methylation state, chromatin marks175 and three-dimensional genome architecture176, will help to elucidate underlying epigenetic mechanisms of memory, especially when coupled with judicious sample selection strategies15 and transcriptional measurements from the same single cells175,177. To help position identified cell types and their states within their proper tissue contexts, high-content spatial profiling methods for RNA or protein profiling can be applied178-182. These endpoint measures can be further coupled with live cell imaging modalities and lineage tracing183 to elucidate the dynamic attributes of the various forms of memory, as well as perturbation methods to screen and functionally test putative memory mechanisms184-186.

Here, we focus on the distribution and storage of inflammatory memory [G] across the cell types and subsets that form barrier tissues, highlighting recent mechanistic insights, the potential functional consequences of encoding memory, and how it may be reinforced. We propose a framework to guide future experiments aimed at understanding cooperative storage of memory across cell lineages, and its impact on tissue adaptation and maladaptation. Elucidating the mechanisms of collective inflammatory memory may eventually allow for new approaches to programme and re-programme memory for infectious and inflammatory disease (Box 2).

Box 2 ∣. The therapeutic implications of inflammatory memory.

“Programming” memories through vaccine-induced immunological memory provided by B cells and plasma cells, and in some cases T cells, has been transformative in reducing infectious disease burden in modern society187. Furthermore, the concept of trained immunity was inspired by the heterologous immunity to pathogens beyond tuberculosis afforded by Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination, presumably through monocytes and macrophages12. Understanding how to prophylactically re-balance myeloid cell subsets in viral and bacterial diseases could yield future dividends, although it is still early in our understanding of this phenomenon188. Furthermore, leveraging the broader principle of tissue inflammatory memory for therapeutic aims in barrier tissues will require a better understanding of how memory is distributed and stored in parenchymal, stromal and neuronal cells to provide effective immunological memory.

While acute inflammation and inflammatory memory are necessary for protective barrier tissue adaptation, chronic activation or re-activation can lead to disease pathology6,29. Significant deviations in the composition of cell types and subsets, and the emergence of unique cell states, are often seen in diseases such as psoriasis, eczema, chronic rhinosinusitis, asthma, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis15,65,189. These diseases are defined by their tissue-restricted presentation, unique genetic predispositions190, microbial dysbioses56,167 and context-dependent triggers, yet are unified through fundamental epithelial barrier remodeling and dysfunction that has been appreciated for decades.

For each of these diseases, the contribution of both innate and adaptive immune cells is well-appreciated 49,191,192, yet therapies targeting cytokines and leukocytes are successful in only some patients193,194, with many becoming treatment refractory, which suggests that alternative mechanisms beyond adaptive immunological memory are involved13,31,62. Therapies that effectively disrupt resident memory leukocytes, in addition to the recruitment of transient leukocytes, will be essential for treating established disease. Furthermore, re-programming of the distributed components of inflammatory memory in parenchymal, stromal and neuronal cell types may serve as important adjunctive therapies to restore tissue health15. Taken together, these approaches may also open opportunities for refining therapeutic strategies towards specific diseases in barrier tissues, rather than suppressing broad types of inflammation or recruitment to many barrier tissues simultaneously.

Components of inflammatory memory

We use the term inflammatory memory to describe the broad responses that encompass protective immunological memory [G] and account for protective, neutral and deleterious secondary responses, regardless of cell type. Our working definitions expand on the latest thinking in the field, including the definitions of immunological memory and distinctions between adaptation and memory provided in two recent perspective articles10,13.

We formalize tissue inflammatory memory storage into five measurable discrete components that are connected through cooperativity (Fig. 2b). The first component of tissue inflammatory memory is specificity, which refers to the recognition of an initiating stimulus, and can range from unique receptor–ligand recognition, or recognition of context-specific cues, to complete promiscuity of specificity. The second component is quantity, which generally refers to an increase in the frequency of responding cells. The third is quality, which describes the polarization of responding cells towards a specified cell state dictated by one to several genes or gene modules or the activity of their products. The fourth component is durability, which is a measure of the time period of increased quality or quantity of a response owing to a combination of cellular and epigenetic factors. And the fifth component describes the distribution, which encompasses the cell lineages, types and subsets that show intrinsic alterations in the first four components in a tissue. Finally, these are linked by the sixth component, cooperativity, which refers to the factors that operate and communicate between cells to promote collective memory retention and recall.

Specificity, quantity, quality and durability.

Immunological memory is present across all kingdoms of life. Bacteria use CRISPR arrays to restrict viral infections, plants use sensitization or priming strategies to defend local and distal tissues, Drosophila fruitflies deploy RNA interference, and mammals rely on antigen-specific T and B cells12,23-25. Much of the recent interest in immunological memory has focused not on its functional properties, but rather on whether the cellular and molecular mechanisms used should be classified as immunological memory within and across species25. Yet, the unifying principle of these mechanisms is that prior exposure to a specific environmental agent induces a change to a measurable parameter (such as specificity) of the host response that persists, often in the absence of the initiating trigger11,13,25. Protective immunity may result from complex cell state programmes26, or even a single gene product being more robustly produced, as is the case for interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3) and infection with influenza virus27.

Two of the main routes to memory storage are through increasing the number of specific cells present (that is, quantity) or altering the response characteristics of these cells (that is, quality; such as polarization towards T helper 1 (TH1), TH2 or TH17 cell states9 (Fig. 2). These shifts are related to clonal expansion and epigenetic alterations (Box 3), respectively12,24, and involve changes to how inputs are sensed in the tissue and subsequent outputs. However, it is important to note that changes in quantity and quality are not mutually exclusive, and both are found in hallmark examples of adaptive and innate immune memory [G]. Thinking beyond the concept that memory is stored within adaptive or innate immune cells is essential for us to more broadly consider the functional roles of inflammatory memory in tissue adaptation25,28-30. It is also important to consider that the time period (durability) over which memory is useful or detrimental, and whether it is an adaptation or memory, will vary based on the specific context (such as microbial or allergen exposure in daily, weekly, monthly or yearly intervals). Finally, it will be important to define whether the presence of the initiating trigger is required to maintain adaptation or whether memory persists in its absence10.

Box 3 ∣. Epigenetic mechanisms of inflammatory memory.

We note that the term epigenetic mechanisms can encompass many distinct layers of regulation: from the activity of transcription factors and non-coding RNAs to enhancer accessibility, the modification of histone tails, and overall three-dimensional genome architecture. We favour the definition of epigenetics as the perpetuation of a transient event or signal within a cell and its progeny195. The sequence-specific activity of transcription factors acting on a cell’s chromatin landscape can promote the stable or transient acquisition of a cell state programme104,195,196, and this is key to specifying and maintaining examples of cellular memory through influence over chromatin accessibility and histone modifications105,106,114,197-200.

This cellular memory fundamentally underlies the stable inheritance of developmental cell type information, tissue-specific adaptations, and the immunological and inflammatory memory considered here10. Cell type, cell subset and cell state gene modules, informed by this epigenetic landscape, have different capacity and propensity to be retained as memories depending on the nature of the mechanisms that enforce them. It will be of interest to further identify the conserved and unique aspects of inflammatory memory modules used by each cell lineage, and the cooperativity of these transcription factors with pioneer cell identity factors and ubiquitous chromatin modifiers46,101,104,114,201-203.

Distribution and cooperativity.

Quantitatively and/or qualitatively enhanced responses may be distributed across multiple cell types in the relevant tissue for rapid inflammatory memory14,31,32. Work over the past decade has elucidated discrete lymphocyte subsets that can “remember” specific immune events and persist in tissues long term18,33-36. This lymphocyte storage of memory occurs in the context of the basic mammalian barrier tissue unit of epithelial cells (the parenchyma), supported by stromal cells (fibroblast and endothelial cells), neurons and haematopoietic cells (macrophages)5,14,37 (Fig. 1)

Cell types other than lymphocytes can also remember immune events. Specific examples include how macrophages can become “trained” to adapt to inflammatory challenges38, how fibroblasts and endothelial cells can be primed by inflammatory cytokines39-41, and most recently, how inflammation shapes epithelial barriers through its actions on the stem cells that give rise to them15,16. How do parenchymal, stromal, neuronal and haematopoietic cells participate in the distribution and storage of tissue inflammatory memory, both independently and cooperatively10,15,16,28,38-40,42? In an attempt to integrate key concepts of inflammatory memory distribution and storage, we describe select examples for each cell type, beginning with those cell subsets for which there is more robust experimental evidence, and ending with emergent findings on the distribution of memory. We conclude with more speculative views on the cooperative storage of memories, and highlight the need for experimental approaches to test the physiological relevance of inflammatory memory cell states in tissues.

Tissue leukocytes in memory storage

Evidence for the existence and functional roles of tissue-resident memory T cells revitalized the study of tissue-resident immune cells; a field originally pioneered through the study of intraepithelial lymphocytes17,33,35,43-45. The initial work on tissue-resident memory cells helped to identify functional markers, such as CD69 and CD103, that are enriched within tissue-resident CD8+ T cell subsets36,46,47. These markers have prompted more recent work characterizing the transcriptional networks that establish tissue-residency programmes and their functional contributions to tissue immunity18,36,46. Efforts continue to extend this paradigm to other lymphocyte subsets36,48.

B cells and plasma cells.

The production of antigen-specific antibodies by memory B cells and terminally-differentiated plasma cells serves to protect epithelia from bacterial colonization and subsequent invasion26,49. If an antibody can neutralize an environmental agent prior to epithelial colonization, it may completely restrict the need to call in the next layer of lymphocytes and molecular mechanisms of defense26 (Fig. 3). These antibodies may be synthesized locally and/or in lymphoid organs50.

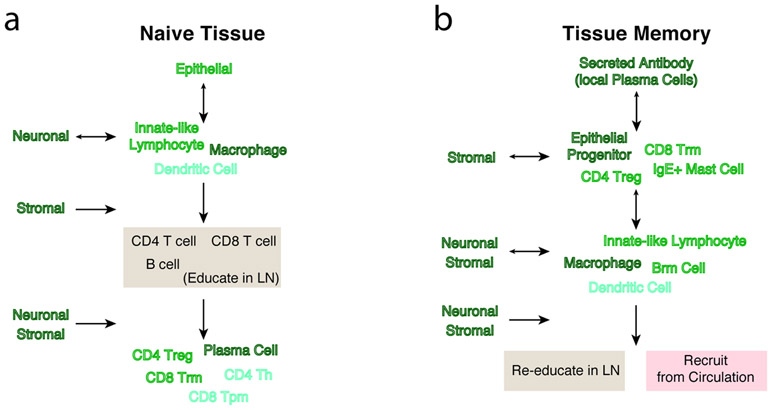

Figure 3 ∣. Inflammatory memory alters circuits in barrier tissues.

The flow of information through a naive tissue (a) or a hypothetical experienced tissue (b), in which memory has been established, with key regulators at each step highlighted on the side of the vertical flow. Arrows indicate predominant direction of information flow. By establishing memory in specific cell subsets such as antibody-producing plasma cells, resident memory CD8+ T cells and epithelial progenitors, the typical flow of information can be “inverted” in a tissue that has inflammatory memory.

Recent work identified discrete subsets of tissue-resident antibody-producing cells. After pulmonary infection of mice with influenza virus, a subset of lung memory B cells expressing CD69 and CXCR3 could persist long-term and promote faster viral clearance upon re-infection by producing IgA and IgG51. Furthermore, the process of selecting B cells that are adept at neutralizing viral escape preferentially occurs in long-lived germinal centres within the lungs52, and antigen re-encounter, rather than non-specific inflammation, was shown to be important for establishing resident memory B cells53. Together, these studies provide evidence that the presence of memory B cells in the lung parenchyma leads to enhanced quantity, quality and rapidity of responses, resulting in enhanced protective immunological memory. However, some tissues, such as the lower female genital tract, may rely on rapidly recruited CXCR3+ memory B cells, rather than resident plasma cells, for protective immunological memory54. While the duration of resident memory B cell responses remains to be determined, solid-organ transplant studies in humans support the potential for plasma cells to preserve life-long memory in the intestine55.

Whether antibody-mediated B cell memory is productive or detrimental varies according to context. Recent theory and studies suggest that antibody-mediated protection strategies may actually support niche establishment of microorganisms that express certain antigenic determinants by selecting for preferential retention56,57. Paradoxically, the presence of pathogen-specific memory B cells in the lungs may even allow for influenza A virus to infect cell types other than epithelial cells, illustrating how the virus may exploit host defense strategies58. The presumed antimicrobial functions of specific induced antibody mechanisms require careful consideration in light of host–microbe co-evolution59.

T cells.

If a microbial pathogen evades antibody detection and successfully infiltrates an epithelial barrier, conventional T cell-mediated effector programmes provide the next layer of specific control. After education in secondary lymphoid organs, conventional T cells gain the ability to migrate to their target tissue and extravasate from the vascular bed into the parenchyma to establish tissue residency31,32,60-62. These steps of tissue homing are required for circulating cells to become tissue residents, and are therefore distinct to the developmental determination of permanent resident cell types, such as parenchymal, stromal and neuronal cells. The literature on tissue-resident memory lymphocytes has been extensively covered in recent Reviews36,46,47.

Experiments using mouse models for infection-independent transplantation of activated CD8+ T cells directly into tissues, and the depletion of vaccination-induced circulating memory cells, have highlighted the functions of resident memory cells in enhancing tissue-restricted infection control36. Pioneering studies demonstrated that antigen-specific CD8+ T cells transferred directly into the skin markedly suppressed replication of herpes simplex virus, and, in a parabiotic mouse model of vaccinia virus skin infection, resident memory T cells provided 300-fold better protection than central memory T cells33,35. Transfer of lung memory CD4+ T cells into naive recipient mice also afforded complete protection from influenza virus-induced mortality34. Collectively, these findings illustrate that enhancing the quantity of antigen-specific, tissue-resident, CD8+ or CD4+ T cells may mediate more effective host protection.

Some fundamental questions that arise from these observations include: what are the qualitative effector mechanisms used by these cells? How many cells are required for immunity? And, how are they retained long term? The answers to these questions may be interdependent, as distinct effector mechanisms can act directly on specific target cells (such as through cytotoxicity) or affect a tissue more broadly (such as through IFN release)17,45, and this may explain how antigen-specific stimulation can lead to heterologous immunity to unrelated pathogens63,64. Tonic expression of several co-inhibitory receptors may restrain the functional activation of expressed cytotoxic and cytokine gene modules, as suggested by scRNA-seq of human colonic intraepithelial CD8+ T cells in healthy individuals and patients with ulcerative colitis65. How effector capacity is intrinsically and/or extrinsically modulated in tissue-resident CD8+ T cells will be of interest to explore further46,47.

To understand what constitutes effective protective immunological memory, it is crucial to define the relative number of tissue-resident memory T cells required to effectively survey permanent resident cell types (such as epithelia, fibroblasts and neurons)66,67. Quantitative microscopy illustrated that a lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV)-induced T cell in the small intestine may only need to scan 6 cells relative to the 80 targets it is “responsible” for by previous estimates, and that, at least after LCMV infection, 90% of memory CD8+ T cells in barrier tissues are resident memory T cells32. The use of quantitative models to determine contact-dependent and contact-independent mechanisms across distinct lymphocyte subsets and environmental challenges will be essential to more accurately quantify surveillance capacity67.

It is currently difficult to generalize about the requirements for the best-known key extrinsic “residence” factors for T cells – namely, antigen, transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) and interleukin-15 (IL-15) – as even seemingly related tissues, such as the upper respiratory tract and the lungs, appear to have different requirements68. Local antigen is not required for resident memory T cell programming, but it can amplify numbers of tissue-resident memory T cells by approximately 50-fold53,69-71. As TGFβ and IL-15 are trans-presented growth factors that maintain tissue-resident memory T cells62,72, understanding the relative contributions of distinct cell sources for these cytokines will be key73,74 (see section on “Memory niches” below). Furthermore, the eliciting type of inflammation and/or antigen strength may play a role in the capacity to form CD8+ and/or CD4+ resident memory cells in the lungs75,76. It will also be important to determine how metabolism intersects with these cues as recent work shows the importance of lipid metabolism and extracellular ATP in shaping fitness and persistence of tissue-resident memory T cells77-79. Other work has explored residency in human tissues, leveraging unique diseases and treatments to clarify specific mechanisms of tissue-resident memory T cells80,81.

CD4+ T cells in tissues and CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cell subsets follow different rules. We speculate that non-migratory tissue-residency programmes may help to confine cytotoxic programmes to sites of previous inflammatory exposure, whereas, when inflammation subsides, CD4+ T helper cells may patrol new sites33,82-86. However, forkhead box P3 (FOXP3)+ regulatory CD4+ T cells have been shown to exploit mechanisms for long-term tissue retention yet “memory-less” suppressor function87-89. Future work is needed to elucidate how spatiotemporal aspects of tissue memory circuits relate to organismal memory90.

These studies on tissue-resident memory T cells illustrate how the presence of newly-recruited cell subsets can fundamentally invert the typical circuits within a naive tissue from the innate immune system to the adaptive immune system (Fig. 3). Recent work on CD8+ T cells resident in the uterus and skin suggests that these cells autonomously dominate the secondary recall response relative to recruited effector T cells91. In summary, after establishment of inflammatory memory, the key sensor of an experienced tissue becomes the TCR, instead of the Toll-like receptor (TLR), and activates antiviral immunity via the output of B cells, dendritic cells (DCs), natural killer (NK) cells, keratinocytes3,63,64 and potentially other resident cell subsets.

Innate lymphoid cells and innate-like T cells.

The qualitative components of resident memory T cells, such as the production of cytokines in the absence of lymph node (re)-education, are often properties of the anticipatory developmental programmes of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) and innate-like lymphocytes48,92,93. Furthermore, antigen-specific resident memory T cells, similarly to ILCs, can activate a generalized state of tissue alarm or alertness through the production of IFNγ acting on other resident cell subsets63,64,91,92. What then is the role of antigen-specific memory in tissues, when the qualities appear similar to those developmentally programmed into resident lymphocytes?

The distribution of memory into antigen-specific cell subsets may serve to allow for wider sensing of environmental exposures through TCRs and BCRs,,together with more tailored cell state outputs compared to those by innate lymphocytes and/or innate-like lymphocytes4,94. Consistent with this idea, _Tcrd_−/− and _Tcra_−/− mice have a hyper-inflammatory phenotype in the intestinal tract, perhaps from the chronic compensatory activation of ILCs17,94. The extent to which antigen-specific tissue-resident memory cells can replace or extend the homeostatic roles of ILCs is an exciting area of investigation92,93,95,96. The progressive loss, or increased specialization towards different subsets, of ILCs and innate-like T cells with increasing immunological events in tissues may replace their generalized tissue maintenance and repair functions in favour of host defense92,97-99.

Macrophages.

Work over the past few years has shown that macrophage and DC subsets share core developmental cell type identity programmes as well as tissue-specific cell state adaptations that are driven by their local environment5,100,101. At the same time, investigators have developed the concept of trained immunity, whereby a primary exposure can functionally reprogramme myeloid cells to a secondary challenge with a similar or distinct pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) or microorganism12,38,102. The unifying aspect of tissue-specific identity and trained immunity is that epigenetic transcriptional response modules integrate with cell type and subset gene regulatory modules to drive the emergence of specific states that are adapted to that tissue and/or microbial challenge10,103-106 (Box 3). While the importance of fetal-derived macrophage subsets relative to recruited monocytes in retaining tissue-resident memory remains to be determined, foundational work in this area highlights that myeloid progenitors in the bone marrow also become functionally reprogrammed107-110.

The concept of trained immunity was largely inspired by two parallel, but related, experimental approaches. Original experiments with Candida albicans infections in mice suggested that a non-lethal dose of C. albicans primes organisms and protects against a future, otherwise lethal, infection in a cytokine- and macrophage-dependent manner28. However, priming with a pathogen or a PAMP does not always lead to an enhanced response, as is the case for lipopolysaccharide (LPS) tolerance [G] 42. Studying the transcriptional and epigenetic response to LPS tolerance has highlighted that while some pro-inflammatory mediators are suppressed, antimicrobial effector molecules are primed, which illustrates the layered control of specific effector transcriptional modules in macrophages42. Intriguingly, exposure to β-glucan derived from C. albicans can reverse some aspects of LPS tolerance111, suggesting contextual control over the formation and erasure of memory.

Early studies of the role of trained immunity in tissues suggest that IFNγ from T cells can directly prime alveolar macrophages, which correlate with enhanced bacterial protection after viral exposure107. Current work is also examining how environmentally responsive transcription factors (such as PPARγ) and cytokine-responsive transcription factors (such as STAT6) cooperatively modify macrophage cell states112. It will be of interest to determine how macrophage-mediated trained immunity operates within the broader context of tissue immunity.

Non-leukocytes in memory storage

Whereas tissue residency is an acquired cell state of an effector lymphocyte or monocyte, it is a developmental property of epithelial, stromal and neuronal cell types46,113,114. Across all four cell lineages, if a cell (or its progeny) can persist between the initial immunological event and subsequent recall, it may have the capacity to meaningfully contribute to collective inflammatory memory. Of course, there may also be instances of bystander effects whereby alterations occur in a cell lineage without impacting subsequent recall. Here, we consider recent insights into epithelial-retained inflammatory memory, which poses an intriguing problem regarding how long-term storage of information could be achieved within a rapidly regenerating compartment, as well as recent insights into the contribution of stromal and neuronal cells to inflammatory memory.

Epithelial cells.

The architecture of stratified epithelia (skin), pseudo-stratified epithelia (airways) and monolayer epithelia (lungs and gut) are distinct, yet all are composed of specialized epithelial cell subsets that collectively perform tissue-essential functions. The production of these cell types is regulated at the level of multipotent epithelial progenitor and stem cells113,115-117. This design is crucial for the epithelial development, turnover (in the order of weeks to months) and response to induced demands5-7,118. If immunological events are to be remembered by epithelia directly, the progenitor compartment would be the prime candidate for storage, as memory assigned to terminally differentiated cells could be rapidly lost.

Groundbreaking insights came from the analysis of dietary regulation of progenitor cell function in the intestine. In this study, mice given a high-fat diet showed increased stemness of both intestinal stem cells and progenitor cells, such that the stem cells became independent of their normal requirement for a Paneth cell niche in organoid-forming assays119. Furthermore, PPARδ was seen to drive elements of the WNT pathway and enhance tumourigenicity of intestinal progenitors. Morphologically the organoids grown from the epithelia of mice given a high-fat diet appeared abnormal, suggesting differences in the output of mature epithelial cells and a potential cellular memory component that was retained ex vivo119.

Another pioneering study in this area highlighted that a brief period of psoriasis-like inflammation could fundamentally alter skin epithelial stem cells to more rapidly repair a subsequent wound at that site14,16. The contributions of skin-resident macrophages or T cells were formally excluded from this process and instead the AIM2–caspase 1–IL-1β axis seemed to be essential for implanting and recalling this memory at a later date16. The inflammatory memory state in progenitor cells persisted for at least 180 days, showing durability of the response.

Identifying non-immune cellular mechanisms that might sustain human inflammatory disease at barrier tissues, another recent study uncovered striking changes in epithelial cellular diversity and mature functional cell types by performing scRNA-seq of samples from patients with chronic rhinosinusitis15. Intriguingly, this study found that alterations in mature cells were driven by the type 2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 acting directly on basal airway epithelial progenitor cells, shifting their cell state and restraining their differentiation capacity. Some of these inferred type 2 cytokine signatures determined in vivo could be propagated through long-term in vitro culture and expansion of sorted human basal progenitor cells, suggesting that these cells could serve as repositories for allergic inflammatory memory15.

Taken together, these studies indicate that memory of immune events can be integrated by epithelial progenitors through diverse sensors, altering their recall responses and functional outcomes across distinct barrier tissues and species15,16,119 (Fig. 3). These studies have yet to address how memory may be preferentially retained within heterogeneous progenitor cell subsets120. Furthermore, it remains to be determined how inflammatory memory retained by epithelial cells affects stress-induced ligands, which interact with innate-like T cells, or chemokines, which recruit conventional T cells, and potentiate cooperation45,47,121. Notably, these studies of inflammatory memory by epithelial stem cells reveal putative transcription factors on the basis of increases in the accessibility of specific chromatin motifs, and draw parallels with the mechanisms of transcriptional maintenance observed in myeloid and lymphoid immunological memory12,28,47,103,106,122,123. It is tempting to speculate that genetically-encoded susceptibility to disease may modify the epigenetic landscape within disease-relevant cell states at baseline to alter predisposition65.

Stromal cells.

Stromal cells include fibroblasts, and vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells. They are essential constituents of barrier tissues that provide structure, conduits for cell migration and developmental cues to surrounding cell types31,124. Furthermore, they have key immunological functions, are pathognomonic in various settings and can lead to the establishment of fibrotic disease125. Of note, experiments performed using type I IFNs provided the initial evidence illustrating cytokine-induced priming of subsequent responses, and the underlying mechanisms were further investigated, in large part, with fibroblasts126,127.

A recent review39 elegantly unifies recent experimental evidence of how stromal cells can also exhibit characteristics of inflammatory memory, and we distill select elements here. Most studies have investigated synovial fibroblasts isolated from inflamed or non-inflamed joints and their enhanced responsiveness after priming to stimuli such as tumour necrosis factor and LPS40,128,129. Intriguingly, synovial fibroblasts, unlike macrophages or endothelial cells, did not show LPS tolerance, illustrating how distinct cell types may differentially regulate identical genes to facilitate a future stereotyped or learned response40,128-130. Extending preliminary insights obtained from scRNA-seq studies to determine whether specific human disease-associated fibroblast subsets preferentially retain more complex memory cell states will be of great interest65,131.

Neurons.

Although the cell bodies of neurons do not reside within epithelial barrier tissues, their processes densely innervate them2,132. Recent work showed that autonomic and peripheral sensory neurons can exert substantial regulation of immunological processes at barrier tissues through directly interfacing with specific immune cell subsets2,133,134 (Fig. 3).

One study highlighted that a specific subset of heat-sensing neurons in the skin drives IL-23 production from dermal DCs leading to IL-17 production from dermal γδ T cells, and promoting psoriasis-like inflammation132. Intriguingly this pathway can be triggered solely by activating neurons optogenetically and is beneficial for host defense during C. albicans skin infection135. Further work on understanding painful bacterial infections emphasized important roles for pain-sensing neurons in directly detecting bacterial toxins and regulating the inflammatory response to intradermal infections136,137. There has also been particular interest in studying ILCs, where investigators have identified several distinct means of neuroimmune interaction, effectively placing a new sensory and regulatory layer above the typical innate-like functions of ILCs at barrier tissues133,138.

Is there a memory of painful exposures that can be recalled to inform future immunological encounters? While the aforementioned circuits have not been explicitly tested for memory formation, recent evidence suggests the possibility that activating cell bodies or peripheral axons of neurons can influence both avoidance behaviour and anticipatory peripheral immune responses, even in the absence of other inflammatory cues135,139,140.

Distribution towards cooperative memory

Cooperativity is a common phenomenon in biology, acting as a crucial regulator of interactions at the molecular, cellular and species levels. Importantly, cooperation can lead to the emergence of higher-order functions that would not have been possible by the individual component4,5,56,141. This specialization is well appreciated as a facilitator of cell type and tissue evolution in metazoans. However, our study of immunological memory has largely focused on the individual components, rather than on their collaborative actions (multiple cell subsets working independently) or cooperative actions (multiple cell subsets working together). Here, based on recent evidence suggesting that multiple cell types distribute memory storage, we propose inflammatory memory can be retained in cooperative cell circuits (Fig. 4). These circuits may help to reinforce cell states and/or promote cell residence in tissues.

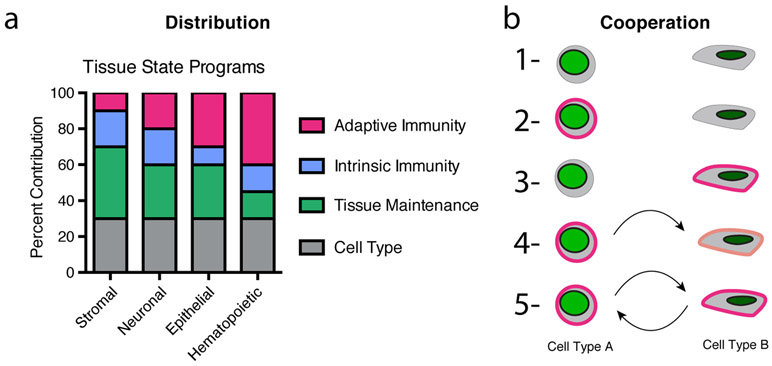

Figure 4 ∣. Distribution and cooperation in tissue memory.

a ∣ A schematic illustrating that stromal, neuronal, epithelial and haematopoietic cells can contain distinct combinations of cell state modules which define their cell type, typical role in tissue maintenance, intrinsic immune capacity and inflammatory memory capacity. The presented values reflect hypothetical relative distributions. b ∣ Potential distributed inflammatory memory states for a system comprised of two cell types: (1) no memory; (2,3) one cell type or the other has inflammatory memory; (4,5) one cell type, or the other, has inflammatory memory which partially influences the other cell type; (6) both cell types collaborate in forming inflammatory memory; (7) or both cell types through cooperation can mutually reinforce one another.

Intercellular circuits.

Looking beyond the intrinsic functions of each cell’s state, we ask how might distinct lineages collaborate or cooperate towards the larger goal of barrier tissue adaptation? (Fig. 4) Epithelial cells have long been appreciated as producers of cytokines and chemokines during barrier tissue challenges9,49. In particular, during type 2 immunity, epithelial cells can release the instructive cytokines thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), IL-33, and IL-2549. Importantly, IL-33 expression by basal cells isolated from human donors with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can be sustained long term142. Together, this work has highlighted that information flow occurs from the epithelium to lymphocytes and myeloid cells.

Only recently has it been appreciated that immune effector cytokines can act directly on permanent residents (that is, stem cells) of the epithelial barrier14. In pioneering work, ILC3-derived IL-22 was shown to influence tissue stem cells in the intestine and promote tissue regeneration143. More recent work in human ulcerative colitis links CD4+ T cell-derived IL-22 with enterocyte fate65. Although IL-22 is generally beneficial owing to its pro-regenerative activity, it may occasionally be detrimental, depending on its cell source and inflammatory context94,143,144, shifting epithelial cell states away from normal metabolic function and towards tumorigenesis94,145.

Direct interactions also facilitate information flow. Such interactions have been revealed in greater detail, for example, through the application of scRNA-seq to generate an atlas of the mouse small intestine, highlighting which specific subsets of stem cells and differentiated cells express MHC class II molecules116,120,146. Expression of MHC class II and antigen presentation machinery was increased in cycling intestinal stem cells, reduced in enterocytes and absent in secretory cell subsets120. By testing lineage-defining cytokines from T helper cell subsets, the authors found that IL-17 was associated with an increase in transit amplifying cells, IL-13 with increased tuft cells [G] and IL-10 with increased stem cell self-renewal120.

Recent work also identified discrete circuits between epithelial instructive cytokines and lymphocyte effector cytokines in type 2 immunity147-149. This work showed that specialized secretory epithelial cells known as tuft cells are responsible for the production of IL-25. Helminth infection enhances tuft cell IL-25 production, leading to an increased abundance of both IL-25+ tuft cells and IL-13+ ILC2s147. Follow-up work clarified that dietary-derived or parasite-derived succinate can also activate this circuit148,149. It will be interesting to determine the points at which homeostatic and induced circuits exhibit long-term adaptation or memory responses in one, or both, of these cell types

Memory niches.

Although we know some of the cytokines, chemokines, growth factors and adhesion molecules that are important for the maintenance of resident memory T and B cells, the cellular sources of these factors remain incompletely defined. Furthermore, the way in which inflammation shapes their expression by distinct cell lineages has not been fully explored. We highlight some vignettes into how niches are formed in barrier tissues, and speculate about how memory in niche cells of any lineage may alter the size or type of memory that is retained.

IL-15, which is a key maintenance factor for intraepithelial lymphocytes, seems to be synthesized by specific subsets of hair follicle-proximal keratinocytes150-152. IL-15 maintains both innate-like T cells and subsequent waves of recruited resident memory CD8+ T cells46,62,72. This creates another interesting problem: how are niches reallocated to accommodate newly recruited T cells? Early work into this area highlighted how, upon inflammation, the network pattern of dendritic epidermal T cells [G] and Langerhans cells present in mouse epidermis at steady state becomes altered and more complex through their replacement by resident memory CD8+ T cells153. Similarly, a recent study in coeliac disease illustrated how chronic inflammation can reshape the epithelial niche for innate-like γδ T cells, which are usually sustained by butyrophilin-like 3 and butyrophilin-like 8 molecules in homeostatic conditions, leading to the entry of gluten-reactive, IFNγ-producing γδ T cells154.

The capacity of tissues for distinct antigen-specific resident memory T cell populations has not been formally explored, but early studies suggest that the niche may be capable of accommodating several waves of recruitment without displacement155. Moreover, researchers are starting to consider how inflammatory cues during subsequent waves of tissue damage either help to retain and reinforce or displace and re-programme existing memory niches. Indeed, extracellular ATP was shown to preferentially deplete bystander resident memory T cells in the tissue to free up niches for new infection-relevant specificities79. Stromal cells will likely play a central role in niche formation156. Exaggerated niche structures known as ectopic lymphoid follicles can form in the lungs via type I interferons leading to CXCL13-mediated support of germinal centre reactions157. Studies exploring how cellular circuits regulate relative cell numbers during homeostasis and disease will help to inform exploration of this important topic in tissues, with single-cell approaches enabling this line of inquiry37,65.

It will be interesting to determine whether ILCs and innate-like T cells serve as essential early settlers in a tissue to preserve future niches for adaptive lymphocytes, in addition to their sentinel role92. Competition for niches between embryonic or adult-derived macrophages may also be relevant in trained immunity. While, in some cases, cells of the same type may compete for niches, distinct cell types can also form cooperative arrangements to maintain memory108. In some barrier tissues, myeloid cells appear to be instrumental for the preservation of memory within the subepithelial compartment, for example through production of the chemokine CCL5, which retains clusters of resident memory CD4+ T cells in the genital mucosa158. There is also evidence for cooperation between closely related cell subsets, whereby the presence of IFNγ-producing CD4+ T cells helps CD8+ T cells enter the epithelium159. Even the earliest work on resident memory CD8+ T cells illustrated the potential for cooperativity between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in local immunity33.

Beyond internal cues, tissue-resident cells may also integrate cues from the external environment into their intrinsic cell state programmes160. Some cell subsets even require an environmentally derived ligand for persistence. For example, aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands, such as those derived from cruciferous vegetables in the intestine, are essential to maintain both intraepithelial innate-like T cells and some conventional CD8+ T cell subsets161. Similarly, microbial-specific T cells adapt their residency programme to balance effector and immunoregulatory functions in response to their microbial environment93,162,163. Comparing wild or “pet store” mice with specific pathogen-free mice will be essential to determine how environmental factors are stored as transient adaptations or long-term memory164. Using TCR-transgenic systems and swapping antigens across bacterial species illustrated that microbial specificity, rather than antigen, dictates the resultant T cell effector state165,166. More broadly, the production of abundant products of colonic microbial fermentation — that is, short-chain fatty acids — has been shown to promote the production of peripheral regulatory T cells167 and also the antimicrobial function of macrophages168. How diet, leukocytes and microorganisms intersect to impact the quantity, quality and distribution of memory will be of interest to explore further169.

Challenges and future perspectives

The concept of innate and adaptive immunity has been, and will continue to be, essential to establish a framework for how immune responses are initiated, maintained and remembered9,170. Here, we extend recent theory and data to suggest that most, if not all, cells in tissues can adapt to, and potentially remember, immunological events12,25,28,30. The process of inflammatory memory is fundamentally concerned with promoting tissue adaptation to environmental exposures during homeostasis, maintenance and disease settings. This process draws from any of the cell types, subsets and states that may be available at the time of exposure, and the specific molecular mechanisms that each individual cell has within its repertoire. Even molecular structures associated with classical adaptive responses, such as the TCR and BCR, have hard-wired “innate” functions that are deployed in advance of, or in parallel with, their “adaptive” properties171,172.

One additional area for further investigation relates to the durability of tissue memory and will require rigorous definitions of what constitutes short-term and long-term adaptation relative to memory responses10. In simple terms, durability reflects a combination of factors, including the stability of inherited memory within a cell, the lifespan of that cell and the ability of that cell to propagate its memory to progeny within a barrier tissue. We highlight that, by necessity, the two longest-lived cell types in a barrier tissue must be its adult epithelial stem cells and underlying stroma. Furthermore, the dense innervation of barrier tissues, in conjunction with the long-lived nature of sensory and autonomic neurons, raises the possibility that neuron-encoded memory might be able to influence subsequent immune responses in tissues2. Determining the mechanisms of inflammatory memory will allow for experimental systems to rigorously test cell states for their potential relevance to tissue adaptation and maladaptation. In particular, it will be of interest to determine the duration, distribution and interaction of these mechanisms across cell lineages, relative contributions to specific responses, and how they are shaped by host and environmental factors15,29. Improving the throughput and cost-effectiveness of techniques to map tissues will provide new opportunities to programme and re-programme inflammatory memory formation prophylactically and during disease.

Does a particular type of inflammation preferentially allow residence and maintenance for the same polarized T cell type? It remains to be seen how the diversity of immunological experience in a tissue influences the quality and plasticity of memory storage. This will likely be dictated by whether memory is truly cell intrinsic or stored in cell-level or tissue-level cooperative circuits, as well as the overall capacity of the tissue for information flow. Furthermore, how the increased specificity of responses to immune events following memory formation intersects with the repair and regenerative capacity of barrier tissues remains to be systematically explored. While there is an overt emphasis here on local immunity, it is also important to remember that redistributing memory through migration to new sites within the same tissue, or between tissues, is essential for overall organismal health.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following individuals for insightful discussions and comments: S. Nyquist, M. Vukovic, S. Kazer, M. Ramseier, V. Miao, C. Kummerlowe, S. Prakadan, members of the Shalek laboratory, U. von Andrian, C. Borges, Z. Sullivan, V. Mani and S. Naik. This work was supported, in part, by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (HHMI Fellow DRG-2274-16; to J.O.M.), the Smith Family Foundation (to J.O.M.), Searle Scholars Program (to A.K.S.), the Beckman Young Investigator Program (to A.K.S.), the Pew-Stewart Scholars Program for Cancer Research (to A.K.S.), a Sloan Fellowship in Chemistry (to A.K.S.), the US National Institutes of Health (1DP2GM119419, 2U19AI089992, 2R01HL095791, 1U54CA217377, 2P01AI039671, 5U24AI118672, 2RM1HG006193, 1U2CCA23319501, 1R01AI138546, 1R01HL134539 and 1R01DA046277; to A.K.S.), the US FDA (HHSF223201810172C; to A.K.S.), and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (to A.K.S.).

GLOSSARY

Barrier tissues

Epithelial tissues that interface directly with the external environment (i.e., any surface directly and constantly exposed to the world outside the host), composed of a monolayer, pseudo-stratified or stratified epithelium, as well as an underlying stromal-derived component and other transient, resident or permanent resident cell lineages.

Immune event

Exposure to an environmental stimulus (such as allergens, antigens, noxious agents, diet, pathogens and microbial communities) or a host-derived stimulus (such as metastasis or sterile tissue damage) at a barrier tissue sensed by the host, triggering downstream transcription and or epigenetic changes in cell state and/or cell composition in the tissue.

Memory

The properties of memory include an altered baseline, maximum, rapidity or sensitivity for a defined response upon secondary challenge to an initiating trigger.

Adaptive immune memory

Classically defined as a memory response by a cell that is considered to be a part of the adaptive immune system (e.g. T cells and B cells), based on the ability of the receptor to be formed and stably inherited across cell divisions through the recombination of genetic elements.

Cell types

Developmentally specified cell identity modules that are typically irreversible beyond enforced overexpression of lineage-overriding transcription factors.

Cell subsets

Typically developmentally stable cells, but their programming may be over-ridden based on niche availability or extreme environments.

Cell state

Characteristics that can be transiently acquired from tissue entry and/or an immune event, is distinct from cellular differentiation, and related to the quality (i.e. type of inflammation) of an immune response.

Gene modules

Sets of co-varying genes that may be co-regulated through the activity of one or more transcription factors, or a complex thereof, often associated with a specific cell attribute such as type (T cell) or state (FOXP3+ regulatory T cell).

Inflammatory memory

A memory response by any cell lineage to an environmental or host-derived cue, typically acquired during an immune event.

Protective immunological memory

A functionally defensive memory response that enables the host to better respond to secondary challenge after an initial exposure. This function can comprise any of the potential mechanisms that may mediate protective recall, and these same mechanisms may concomitantly or separately mediate immunopathology.

Innate immune memory

Classically defined as a memory response by a cell that is considered to be a part of the innate immune system (for example, macrophages and natural killer cells). However, we favour the use of innate immune memory for memory events triggered by germline-encoded receptors expressed by any cell lineage.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) tolerance

Macrophages exposed to sustained stimulation with LPS or high-dose LPS acquire a hypo-responsive state in which sets of inflammatory genes are blunted in their secondary response to LPS or other inflammatory cytokines.

Tuft cells

Rare chemosensory epithelial cells characterized by a “tuft-like” brush of microvilli present in epithelial (primarily mucosal) tissues of mammals characterized by expression of taste receptors and production of instructive allergic inflammatory cytokines.

Dendritic epidermal T cells

γ T cell receptor-expressing cells selectively localized in the epidermis that have been identified in rodents and cattle, but not humans. In mice, essentially all dendritic epidermal T cells express the same T cell receptor constituting a prototypical innate-like T cell.

TOC blurb

Here the authors urge us to extend our concept of memory to encompass diverse cell types within a barrier tissue. They propose that any tissue cell can store memory of previous immune events and cooperate in memory recall.

Footnotes

Competing interests

A.K.S. has received compensation for consulting and SAB membership from Honeycomb Biotechnologies, Cellarity, Cogen Therapeutics and Dahlia Biosciences.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Immunology thanks A. Iwasaki, G. Natoli, M. Netea and D. Masopust for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belkaid Y & Artis D Immunity at the barriers. Eur. J. Immunol 43, 3096–3097 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ordovas-Montanes J et al. The regulation of immunological processes by peripheral neurons in homeostasis and disease. Trends Immunol. 36, 578–604 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S & Medzhitov R Recognition of commensal microflora by Toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell 118, 229–241 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arendt D et al. The origin and evolution of cell types. Nat Rev Genet 17, 744–757 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okabe Y & Medzhitov R Tissue biology perspective on macrophages. Nat. Immunol 17, 9–17 (2015).This Review discusses the role of macrophages in tissue biology with a focus on cell type diversification and specialization from an evolutionary and transcriptional perspective.

- 6.Kotas ME & Medzhitov R Homeostasis, inflammation, and disease susceptibility. Cell 160, 816–827 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karin M & Clevers H Reparative inflammation takes charge of tissue regeneration. Nature 529, 307–315 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hedrick SM The acquired immune system: a vantage from beneath. Immunity 21, 607–615 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwasaki A & Medzhitov R Control of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Nat. Immunol 16, 343–353 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Natoli G & Ostuni R Adaptation and memory in immune responses. Nat. Immunol 20, 783–792 (2019).This Review discusses the important concepts of adaptation and memory, providing definitions and molecular properties for these processes.

- 11.Schneider D & Tate AT Innate immune memory: activation of macrophage killing ability by developmental duties. Curr. Biol 26, R503–R505 (2016).In this perspective, the authors outline a framework through which to consider memory responses based on the relationship between stimulus levels and response levels.

- 12.Netea MG et al. Trained immunity: A program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science 352, aaf1098 (2016).This review outlines the properties of trained immunity, and the similarties and differences to adaptive immunity.

- 13.Farber DL, Netea MG, Radbruch A, Rajewsky K & Zinkernagel RM Immunological memory: lessons from the past and a look to the future. Nat. Rev. Immunol 16, 124–128 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naik S, Larsen SB, Cowley CJ & Fuchs E Two to tango: dialog between immunity and stem cells in health and disease. Cell 175, 908–920 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ordovas-Montanes J et al. Allergic inflammatory memory in human respiratory epithelial progenitor cells. Nature 560, 649–654 (2018).This study demonstrated that human epithelial stem cells may contribute to the persistence of disease by serving as repositories for allergic inflammatory memories.

- 16.Naik S et al. Inflammatory memory sensitizes skin epithelial stem cells to tissue damage. Nature 550, 475–480 (2017).This study identified a prolonged memory to acute inflammation that allows murine epidermal stem cells to repair wounds more rapidly on subsequent damage.

- 17.Hayday A, Theodoridis E, Ramsburg E & Shires J Intraepithelial lymphocytes: exploring the Third Way in immunology. Nat. Immunol 2, 997–1003 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mueller SN & Mackay LK Tissue-resident memory T cells: local specialists in immune defence. Nat. Rev. Immunol 16, 79–89 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satija R & Shalek AK Heterogeneity in immune responses: from populations to single cells. Trends Immunol. 35, 219–229 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gierahn TM et al. Seq-Well: portable, low-cost RNA sequencing of single cells at high throughput. Nat Methods 14, 395–398 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shalek AK et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals bimodality in expression and splicing in immune cells. Nature 498, 236–240 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prakadan SM, Shalek AK & Weitz DA Scaling by shrinking: empowering single-cell ‘omics’ with microfluidic devices. Nat Rev Genet 18, 345–361 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nunez JK, Bai L, Harrington LB, Hinder TL & Doudna JA CRISPR Immunological Memory Requires a Host Factor for Specificity. Mol. Cell 62, 824–833 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conrath U, Beckers GJ, Langenbach CJ & Jaskiewicz MR Priming for enhanced defense. Annu Rev Phytopathol 53, 97–119 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pradeu T & Du Pasquier L Immunological memory: What’s in a name? Immunol. Rev 283, 7–20 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed R & Gray D Immunological memory and protective immunity: understanding their relation. Science 272, 54–60 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Everitt AR et al. IFITM3 restricts the morbidity and mortality associated with influenza. Nature 484, 519–523 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cassone A The case for an expanded concept of trained immunity. MBio 9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai X & Medzhitov R Inflammation: memory beyond immunity. Nature 550, 460–461 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun JC, Ugolini S & Vivier E Immunological memory within the innate immune system. EMBO J. 33, 1295–1303 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Andrian UH & Mackay CR T-cell function and migration. Two sides of the same coin. N. Engl. J. Med 343, 1020–1034 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinert EM et al. Quantifying memory CD8 T cells reveals regionalization of immunosurveillance. Cell 161, 737–749 (2015).This study found that tissue dissociation techniques underestimate cellular recovery, and quantified the ratio of parenchymal to tissue-resident CD8+ T cells in selected organs.

- 33.Gebhardt T et al. Memory T cells in nonlymphoid tissue that provide enhanced local immunity during infection with herpes simplex virus. Nat. Immunol 10, 524–530 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teijaro JR et al. Cutting edge: Tissue-retentive lung memory CD4 T cells mediate optimal protection to respiratory virus infection. J. Immunol. 187, 5510–5514 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang X et al. Skin infection generates non-migratory memory CD8+ T(RM) cells providing global skin immunity. Nature 483, 227–231 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masopust D & Soerens AG Tissue-resident T cells and other resident leukocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol 37, 521–546 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou X et al. Circuit design features of a stable two-cell system. Cell 172, 744–757 e717 (2018).This study used computational predictions and experiments to identify the features of macrophage–fibroblast circuits based on growth factor exchange.

- 38.Saeed S et al. Epigenetic programming of monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and trained innate immunity. Science 345, 1251086 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crowley T, Buckley CD & Clark AR Stroma: the forgotten cells of innate immune memory. Clin. Exp. Immunol 193, 24–36 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sohn C et al. Prolonged tumor necrosis factor alpha primes fibroblast-like synoviocytes in a gene-specific manner by altering chromatin. Arthritis Rheumatol 67, 86–95 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolff B, Burns AR, Middleton J & Rot A Endothelial cell “memory” of inflammatory stimulation: human venular endothelial cells store interleukin 8 in Weibel-Palade bodies. J. Exp. Med 188, 1757–1762 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foster SL, Hargreaves DC & Medzhitov R Gene-specific control of inflammation by TLR-induced chromatin modifications. Nature 447, 972–978 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Masopust D et al. Dynamic T cell migration program provides resident memory within intestinal epithelium. J. Exp. Med 207, 553–564 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clark RA et al. The vast majority of CLA+ T cells are resident in normal skin. J. Immunol 176, 4431–4439 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheroutre H & Madakamutil L Acquired and natural memory T cells join forces at the mucosal front line. Nat. Rev. Immunol 4, 290–300 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mackay LK & Kallies A Transcriptional regulation of tissue-resident lymphocytes. Trends Immunol. 38, 94–103 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Milner JJ & Goldrath AW Transcriptional programming of tissue-resident memory CD8(+) T cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol 51, 162–169 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fan X & Rudensky AY Hallmarks of tissue-resident lymphocytes. Cell 164, 1198–1211 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iwasaki A, Foxman EF & Molony RD Early local immune defences in the respiratory tract. Nat. Rev. Immunol 17, 7–20 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Radbruch A et al. Competence and competition: the challenge of becoming a long-lived plasma cell. Nat. Rev. Immunol 6, 741–750 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Onodera T et al. Memory B cells in the lung participate in protective humoral immune responses to pulmonary influenza virus reinfection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 2485–2490 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adachi Y et al. Distinct germinal center selection at local sites shapes memory B cell response to viral escape. J. Exp. Med 212, 1709–1723 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allie SR et al. The establishment of resident memory B cells in the lung requires local antigen encounter. Nat. Immunol 20, 97–108 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oh JE et al. Migrant memory B cells secrete luminal antibody in the vagina. Nature 571, 122–126 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Landsverk OJ et al. Antibody-secreting plasma cells persist for decades in human intestine. J. Exp. Med 214, 309–317 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Foster KR, Schluter J, Coyte KZ & Rakoff-Nahoum S The evolution of the host microbiome as an ecosystem on a leash. Nature 548, 43–51 (2017).This perspective provides an evolutionarily-based framework to understand host–microbe interactions with an emphasis on studying the axes of microbial competition and host control.

- 57.Donaldson GP et al. Gut microbiota utilize immunoglobulin A for mucosal colonization. Science 360, 795–800 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dougan SK et al. Antigen-specific B-cell receptor sensitizes B cells to infection by influenza virus. Nature 503, 406–409 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hedrick SM Understanding immunity through the lens of disease ecology. Trends Immunol. 38, 888–903 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mora JR et al. Selective imprinting of gut-homing T cells by Peyer’s patch dendritic cells. Nature 424, 88–93 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gerlach C et al. The chemokine receptor CX3CR1 defines three antigen-experienced CD8 T cell subsets with distinct roles in immune surveillance and homeostasis. Immunity 45, 1270–1284 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mackay LK et al. The developmental pathway for CD103(+)CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells of skin. Nat. Immunol 14, 1294–1301 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schenkel JM et al. T cell memory. Resident memory CD8 T cells trigger protective innate and adaptive immune responses. Science 346, 98–101 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ariotti S et al. T cell memory. Skin-resident memory CD8(+) T cells trigger a state of tissue-wide pathogen alert. Science 346, 101–105 (2014).References 63 and 64 report how CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells activate an alarm function in a tissue providing protection to an unrelated pathogen.

- 65.Smillie CS et al. Intra- and inter-cellular rewiring of the human colon during ulcerative colitis. Cell 178, 714–730 e722 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gebhardt T et al. Different patterns of peripheral migration by memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Nature 477, 216–219 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roychoudhury P et al. Elimination of HSV-2 infected cells is mediated predominantly by paracrine effects of tissue-resident T cell derived cytokines. bioRxiv, 610634 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pizzolla A et al. Resident memory CD8+ T cells in the upper respiratory tract prevent pulmonary influenza virus infection. Sci Immunol 2 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khan TN, Mooster JL, Kilgore AM, Osborn JF & Nolz JC Local antigen in nonlymphoid tissue promotes resident memory CD8+ T cell formation during viral infection. J. Exp. Med 213, 951–966 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Casey KA et al. Antigen-independent differentiation and maintenance of effector-like resident memory T cells in tissues. J. Immunol 188, 4866–4875 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mackay LK et al. Long-lived epithelial immunity by tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells in the absence of persisting local antigen presentation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 7037–7042 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mackay LK et al. T-box transcription factors combine with the cytokines TGF-beta and IL-15 to control tissue-resident memory T cell fate. Immunity 43, 1101–1111 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mortier E et al. Macrophage- and dendritic-cell-derived interleukin-15 receptor alpha supports homeostasis of distinct CD8+ T cell subsets. Immunity 31, 811–822 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mani V et al. Migratory DCs activate TGF-beta to precondition naive CD8(+) T cells for tissue-resident memory fate. Science 366 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Turner DL et al. Lung niches for the generation and maintenance of tissue-resident memory T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 7, 501–510 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Turner DL et al. Biased generation and in situ activation of lung tissue-resident memory CD4 T cells in the pathogenesis of allergic asthma. J. Immunol 200, 1561–1569 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pan Y et al. Survival of tissue-resident memory T cells requires exogenous lipid uptake and metabolism. Nature 543, 252–256 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Borges da Silva H et al. The purinergic receptor P2RX7 directs metabolic fitness of long-lived memory CD8(+) T cells. Nature 559, 264–268 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stark R et al. T RM maintenance is regulated by tissue damage via P2RX7. Sci Immunol 3 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kumar BV et al. Human tissue-resident memory T cells are defined by core transcriptional and functional signatures in lymphoid and mucosal sites. Cell Rep. 20, 2921–2934 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Clark RA et al. Skin effector memory T cells do not recirculate and provide immune protection in alemtuzumab-treated CTCL patients. Sci. Transl. Med 4, 117ra117 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Collins N et al. Skin CD4(+) memory T cells exhibit combined cluster-mediated retention and equilibration with the circulation. Nat Commun 7, 11514 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oja AE et al. Trigger-happy resident memory CD4(+) T cells inhabit the human lungs. Mucosal Immunol. 11, 654–667 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Carbone FR & Gebhardt T Should I stay or should I go - reconciling clashing perspectives on CD4(+) tissue-resident memory T cells. Sci Immunol 4 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Klicznik MM et al. Human CD4(+)CD103(+) cutaneous resident memory T cells are found in the circulation of healthy individuals. Sci Immunol 4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Beura LK et al. CD4(+) resident memory T cells dominate immunosurveillance and orchestrate local recall responses. J. Exp. Med 216, 1214–1229 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.DiSpirito JR et al. Molecular diversification of regulatory T cells in nonlymphoid tissues. Sci Immunol 3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rosenblum MD et al. Response to self antigen imprints regulatory memory in tissues. Nature 480, 538–542 (2011).This study uses tissue-specific autoantigen expression to identify that regulatory T cells are maintained in tissues and provide enhanced suppression to subsequent autoimmune reactions.

- 89.van der Veeken J et al. Memory of inflammation in regulatory T cells. Cell 166, 977–990 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kadoki M et al. Organism-level analysis of vaccination reveals networks of protection across tissues. Cell 171, 398–413 e321 (2017).This study provides a characterization of intra-tissue networks of communication after vaccination and viral infection.

- 91.Beura LK et al. Intravital mucosal imaging of CD8(+) resident memory T cells shows tissue-autonomous recall responses that amplify secondary memory. Nat. Immunol 19, 173–182 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kotas ME & Locksley RM Why innate lymphoid cells? Immunity 48, 1081–1090 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Linehan JL et al. Non-classical immunity controls microbiota impact on skin immunity and tissue repair. Cell 172, 784–796 e718 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mao K et al. Innate and adaptive lymphocytes sequentially shape the gut microbiota and lipid metabolism. Nature 554, 255–259 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Arpaia N et al. A distinct function of regulatory T cells in tissue protection. Cell 162, 1078–1089 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Harrison OJ et al. Commensal-specific T cell plasticity promotes rapid tissue adaptation to injury. Science 363 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sheridan BS et al. gammadelta T cells exhibit multifunctional and protective memory in intestinal tissues. Immunity 39, 184–195 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Martinez-Gonzalez I et al. Allergen-experienced group 2 innate lymphoid cells acquire memory-like properties and enhance allergic lung inflammation. Immunity 45, 198–208 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]