Dora Carrington (original) (raw)

Dora Carrington, the second of the two daughters and fourth of the five children of Samuel Carrington, railway engineer, and his wife, Charlotte Houghton, was born in Hereford on 29th March 1893. The family moved to Rothsay Gardens in Bedford. She later recalled that she had "an awful childhood."

According to Vanessa Curtis: "Although Carrington adored and revered her father, sketching him almost obsessively, she did not admire her fussy, martyr-like mother, who crammed the house with ornaments and devoted herself to charity work and religious causes." Her brother, Noel Carrington, has suggested that his mother was obsessed with conformity and convention and this took two forms: "The first was extreme prudishness. Any mention of sex or the common bodily functions was unthinkable. We were not even expected to know that a woman was pregnant. Even a word like confined was kept to a whisper. The second was church-going and behaviour on Sunday. We all came to hate the whole atmosphere of a Sunday morning. The special clothes, the carrying of prayer books, the kneeling, standing and murmuring of litanies."

While at Bedford High School her teachers became aware of her artistic talent. Gretchen Gerzina, the author of A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989) has pointed out: "At school, Dora's work was indifferent except in natural history and art, but her great talent for drawing and painting was obvious to everyone.... Her artistic success at Bedford High School was immense. Each year the Royal Drawing Society of Great Britain and Ireland awarded prizes for the best school drawings and exhibited them in a London show. Two years after entering the school, she became a regular winner: in 1905 she won First Class for imaginative drawings of figures; in 1906 a Bronze Star for figure drawing in colour."

In 1910 Samuel Carrington agreed that his daughter she should attend the Slade School. At the time the students included C.R.W. Nevinson, Mark Gertler, Stanley Spencer, John Currie, Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot, Dorothy Brett, Paul Nash, John Nash, David Bomberg, Isaac Rosenberg, Edward Wadsworth, Adrian Allinson and Rudolph Ihlee. Nevinson commented that the Slade "was full with a crowd of men such as I have never seen before or since." He also wrote that Gertler was "the genius of the place... and the most serious, single-minded artist I have ever come across." One of their tutors, Henry Tonks, who found them too rebellious, later pondered: "What a brood I have raised."

Carrington's friend, Frances Marshall, has argued: "She (Carrington) was an attractive and popular figure with her large blue eyes and her shock of thick hair bobbed in the fashion she had set... Moreover, her individual sense of fun and fantasy made her an enchanting companion, though a neurotic strain was also apparent.... Her oil paintings were much influenced by Mark Gertler in their careful, smooth technique, three-dimensioned effect, and dense, rich colour." Ottoline Morrell, who got to know her during this period, described her as "a wild moorland pony".

David Boyd Haycock, the author of A Crisis of Brilliance (2009) has pointed out that Carrington became very close to Dorothy Brett and Barbara Hiles while at the Slade School. Brett and Hiles copied Carrington when in 1911 she cut her long hair to a "short, boyish bob". They became known as the "Slade Cropheads" and "set a trend for young female art students".

Dora Carrington, Barbara Hiles and Dorothy Brett in 1911

Paul Nash, a fellow student at the Slade School, later recalled: "Carrington... was the dominating personality, and when she cut her thick gold hair into a heavy golden bell, this, her fine blue eyes, her turned-in toes and other rather quaint but attractive attributes, combined to make her a conspicuous and popular figure... I had noticed her long before this was achieved, when as a bored sufferer in the Antique Class my attention had been suddenly fixed by the sight of this amusing person with such very blue eyes and such incredibly thick pigtails of red-gold hair. I got an introduction to her and eventually won her regard by lending her my braces for a fancy-dress party. We were on the top of a bus and she wanted them then and there."

Mark Gertler and C.R.W. Nevinson both became closely attached to Carrington. According to Michael J. K. Walsh, the author of C. R. W. Nevinson: The Cult of Violence (2002): "What he (Nevinson) was not aware of was that Carrington was also conversing, writing and meeting with Gertler in a similar fashion, and the latter was beginning to want to rid himself of competition for her affections. For Gertler the friendship would be complicated by sexual frustration while Carrington had no particular desire to become romantically involved with either man."

On 12th June 1912, Carrington wrote to C.R.W. Nevinson. The letter has not survived, but his response to it has. It starts: "Your note came as a horrible surprise to me. I cannot guess what has happened to make you wish to do without me as a friend next term." It seems that Carrington had complained about the intimacy of his letters. He added: "I swear I will never speak a word to you as your lover... I promise you I will be a great friend of yours nothing more and nothing less and if you want to get simple again I am only too willing to do the same."

Carrington also received a letter from Mark Gertler asking her to marry him. He listed the reasons why she should accept his proposal: "(1) I am a very promising artist - one who is likely to make a lot of money; (2) I am an intelligent companion; (3) You would not have to rely upon your people; (4) I could help you in your art career. (5) You would have absolute freedom and a nice studio of your own."

When she rejected this proposal he wrote a further letter on 2nd July, suggesting: "Your affections are completely given to Nevinson. I must have been a fool to stand it as long as I have, without seeing through you. I have written to Nevinson telling him that we, he and I, are no longer friends." In the letter he argued, "much as I have tried to overlook it, I have come to the conclusion that rivals, and rivals in love, cannot be friends."

Dora Carrington, C.R.W. Nevinson and Mark Gertler at the Slade School.

C.R.W. Nevinson continued to plead with Carrington to remain his friend: "I am now without a friend in the whole world except you.... I cannot give you up, you have put a reason into my life and I am through you slowly winning back my self-respect. I did feel so useless so futile before I devoted my life to you." He also wanted a return of Gertler's friendship: "I am aching for the companionship of Gertler, our talks on Art, on my work, his work and our life in general. God how fond of him I am. I never realised it so thoroughly till now."

Mark Gertler now wrote to Nevinson: "I am writing here to tell you that our friendship must end from now, my sole reason being that I am in love with Carrington and I have reason to believe that you are so too. Therefore, much as I have tried to overlook it, I have come to the conclusion that rivals, and rivals in love, cannot be friends. You must know that ever since you brought Carrington to my studio my love for her has been steadily increasing. You might also remember that many times, when you asked me down to dinner. I refused to come. Jealously was the cause of it. Whenever you told me that you had been kissing her, you could have knocked me down with a feather, so faint was I. Whenever you saw me depressed of late, when we were all out together, it wasn't boredom as I pretended but love."

(If you find this article useful, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter)

However, Carrington refused to begin a sexual relationship with Gerter during this period. Vanessa Curtis has suggested: "Although passionate towards Gertler when discussing art, Carrington, at eighteen, had not yet had her sexuality awakened; her upbringing had taught her to repress her innermost feelings. She was looking for a platonic soul mate, but what she found was a man who was highly sexed and constantly irritated and frustrated by Carrington's lack of passion. The heartbreaking letters that passed regularly between them pay sad testimony to the anguish that this long relationship caused."

Gretchen Gerzina has argued: "In adulthood she found herself hopelessly divided, with frigidity and sexuality, tradition and free-thinking, reclusiveness and sociability uncomfortably mixed in her personality.... She was very much the product of a late-Victorian upbringing, and it is doubtful that she knew very much about sex at all. She felt none of the sexual urges that Gertler did, even confessing that she had never been drawn to a man's body in the way he was drawn to a woman's."

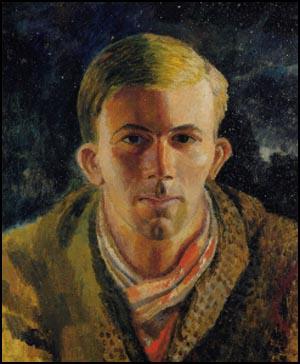

Dora Carrington, The Boot Boy (c. 1913)

Albert Rutherston also fell in love with Carrington. In a letter sent on 17th May 1914, he explained his feelings for his fellow student: "Carrington please never believe for an instant that anybody in the world could say or for a moment think seriously, that you gave me the slightest encouragement to think of you save as a friend. I knew always & realised that you regarded me entirely in this light - if it hadn't been for this knowledge, then I would have told you myself before other folks made you realise that it wasn't quite so & that I cared for you differently ... Carrington it wasn't that I didn't wish & long to speak to you but that it was impossible, knowing you to be entirely innocent that I cared for you rather more than I ought to. I'm wretchedly sorry... I've loved you & all of you, yes, your talent, your delightful insight & wit, & your presence & friendship have brought me golden hours & perhaps great hope & all this given thought I knew that in your eyes I was simply a friend."

Another admirer was David Garnett, who met her at a party: "The door opened and two other visitors entered - a dark handsome young Jewish painter, called Mark Gertler, and a girl to whom I was at once powerfully attracted. Her thick hair, the colour of a new wheat straw thatch, was cut pudding-basin fashion round her neck and below her ears. Her complexion was delicate, like a white-heart cherry; a curious crooked nose gave character to her face and pure blue eyes made her appear simple and childish when she was in fact the very opposite. Her clothes labelled her an art-student and she was in fact, like Gertler, at the Slade. She concealed her Christian name, which was Dora, and was always called by her surname, Carrington."

Dora Carrington left the Slade School in 1914. Carrington's lack of confidence meant that she was reluctant to exhibit or even sign her work. However, she had some important friends who tried to help her career. Virginia Woolf commissioned her to produce several woodcuts for Hogarth Press and Roger Fry provided work restoring a Mantegna for Hampton Court.

Frances Marshall met Carrington in 1914. "Her unique personal flavour makes her extraordinarily difficult to describe, but fortunately she has painted her own portrait much better than anyone else could in her letters and diaries, which no-one can read without recognising her originality, fantastic imagination and humour. Her poetic response to nature shines from her paintings, and from letters whose handwriting was in itself a form of drawing.... Physically, her most remarkable features were her large, deepset blue eyes and her mop of thick straight hair, the colour of ripe corn. Her movements were sometimes almost awkward, like those of a little girl, and she would stand with head hanging and toes turned in; while her very soft voice was also somewhat childish and made a first impression of affectation. Her laugh was delightfully infectious."

Aldous Huxley fell in love with Carrington during this period. "Her short hair, clipped like a page's, hung in a bell of elastic gold about her cheeks. She had large blue china eyes, whose expression was one of ingenuous and often puzzled earnestness." Although she enjoyed his company she was not looking for a physical relationship with Huxley. He told Dorothy Brett: "Carrington and I had a long argument on the subject of virginity: I may say it was she who provoked it by saying that she intended to remain a vestal for the rest of her life. All expostulations on my part were in vain."

Huxley put Carrington in his novel Crome Yellow (Mary Bracegirdle). Huxley recreated his many discussions with Carrington. She explained what she was looking for in a man: "It must be somebody intelligent, somebody with intellectual interests that I can share. And it must be somebody with a proper respect for women, somebody who's prepared to talk seriously about his work and his ideas and about my work and my ideas. It isn't, as you see, at all easy to find the right person."

Dora continued to see Mark Gertler, but refused to have a sexual relationship with him. On 16th April 1915 she wrote to Gertler: "I cannot love you as you want me to. You must know one could not do, what you ask, sexual intercourse, unless one does love a man's body. I have never felt any desire for that in my life: I wrote only four months ago and told you all this, you said you never wanted me to take any notice of you when you wrote again; if it was not that you just asked me to speak frankly and plainly I should not be writing. I do love you, but not in the way you want.... Can I help it? I wish to God I could. Do not think I rejoice in being sexless, and am happy over this. It gives me pain also."

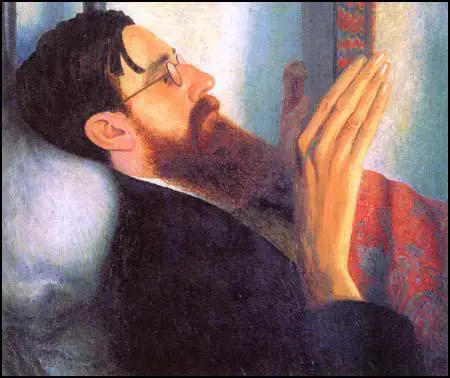

Carrington met Lytton Strachey while staying with Virginia Woolf at Asheham House at Beddingham, near Lewes, she jointly leased with Leonard Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell and Duncan Grant. The author of Virginia Woolf's Women (2002) has pointed out: "Attracted to Carrington from the moment he first laid eyes on her, he had boldly tried to kiss her during a walk across the South Downs, the feeling of his beard prompting an enraged outburst of disgust from the unwilling recipient. According to legend, Carrington plotted frenzied revenge, creeping into Lytton's bedroom during the night with the intention of cutting off the detested beard. Instead, she was mesmerized by his eyes, which opened suddenly and regarded her intently. From that moment on, the two became virtually inseparable."

Jane Hill, the author of The Art of Dora Carrington (1994) has commented: "Carrington was petite, several heads shorter than Lytton and had a quirky way of dressing. Lytton was bohemian looking and emaciated. Both together and apart they were stared at in the street. Carrington's hair attracted hostile yells and Lytton's unfashionable beard provoked goat bleatings." Vanessa Curtis has argued: "Initially, Strachey's friends viewed the idea of Carrington and Lytton as a couple with repulsion; it was considered extremely inappropriate. Even though it was evident almost from the start that they were to enjoy a platonic relationship rather than a sexual one, the relationship was the talk of Bloomsbury for several months. They were a curious looking couple: Lytton was tall and lanky, bespectacled and with a curiously high-pitched voice, Carrington was short, chubby, eccentrically dressed and with daringly short hair."

Dora Carrington, Lytton Strachey (1916)

Dora Carrington became friendly with Philip Morrell and Ottoline Morrell. In 1915 the Morrells purchased Garsington Manor near Oxford and it became a meeting place for left-wing intellectuals. This included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, Lytton Strachey, Dora Carrington, Bertram Russell, Leonard Woolf, David Garnett, Desmond MacCarthy, Dorothy Brett, Siegfried Sassoon, D.H. Lawrence, Frieda Lawrence, Ethel Smyth, Katherine Mansfield, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, Thomas Hardy, Vita Sackville-West, Herbert Asquith, Harold Nicolson and T.S. Eliot.

Carrington became especially close to Katherine Mansfield. In a letter Carrington wrote to Lytton Strachey on 6th September 1916 she explained how she was hoping to set up home with Mansfield and Dorothy Brett: "Late Tuesday evening I bicycled over to Garsington to see Dorothy Brett about this house business, & Katherine Mansfield was there. I shared a room with her. So talked to her more than anyone else late at night in bed & early in the morning. I like her very much. It is a good thought to think upon that I shall live with them & Brett ... What parties we shall have in Gower Street in the evenings. Katherine was full of plans... Except for Katherine I should not have enjoyed it much. But she surprised me I did not believe she would love the sort of things I do so much. Pretending to be other people & playing games & all those strange people with their intrigues .. . Katherine and I wore trousers. It was wonderful being alone in the garden. Hearing the music inside, & lighted windows and feeling like two young boys - very eager. The moon shining on the pond, fermenting & covered with warm slime. How I hate being a girl. I must tell you for I have felt it so much lately. More than usual. And that night I forgot for almost half an hour in the garden, and felt other pleasures strange, & so exciting, a feeling of all the world being below me to choose from. Not tied - with female encumbrances, & hanging flesh."

Carrington became very angry when Philip Morrell and Ottoline Morrell began to interfere with her relationship with Mark Gertler. She told Lytton Strachey on 28th July 1916: "I spent a wretched time here since I wrote this letter to you. I was dismal enough about Mark and then suddenly without any warning Philip Morrell after dinner asked me to walk round the pond with him and started without any preface, to say, how disappointed he had been to hear I was a virgin! How wrong I was in my attitude to Mark and then proceeded to give me a lecture for a quarter of an hour! Winding up by a gloomy story of his brother who committed suicide. Ottoline then seized me on my return to the house and talked for one hour and a half in the asparagus bed, on the subject, far into the dark night. Only she was human and did see something of what I meant."

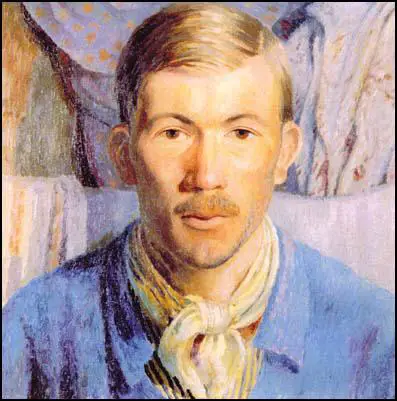

In 1916 Gilbert Cannan published the novel Mendel: A Story of Youth. It was based on the lives of his friends, Carrington, Mark Gertler and John S. Currie. The novel tells the story of an impetuous but talented immigrant painter, Mendel Kuhler (Gertler) who is in love with Greta Morrison (Carrington), who refuses to sleep with him. D. H. Lawrence explained how "Gertler... has told every detail of his life to Gilbert... who has a lawyer's memory and he has put it all down, and so ridiculously when it comes to the love affair... it is a bad book - statement without creation - really journalism." Carrington was furious that Gertler had told Cannan about their relationship: "How angry I am over Gilbert's book. Everywhere this confounded gossip, and servant-like curiously. It's ugly and so damned vulgar."

Soon after the publication of this book, Carrington agreed to sleep with Gertler. According to Gretchen Gerzina, the author of A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989): "At long last they embarked upon a sexual relationship, with a predictable result. Carrington failed to get really interested and it proved a tremendous disappointment after the years of difficulty that preceded it.... She and Mark continued to sleep together, unsatisfactorily, for some time."

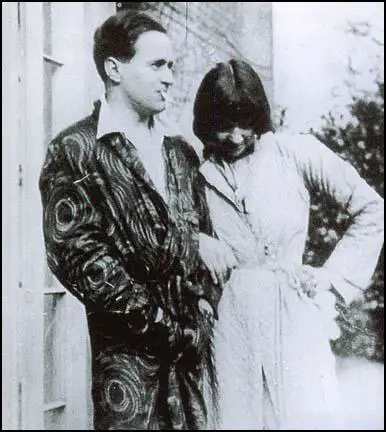

Dora Carrington (1917)

Mark Gertler continued to complain about her need to have relationships with several different people. In December 1916 he wrote to Carrington complaining about these "advanced" views: "For God's sake don't torture me by not letting me see much of you - I must see you very often. I shan't worry you for much sugar if only I can see you and talk - I must, I must. And if any other man touches any part of your beautiful body I shall kill myself - don't forget that! I could not bear such a thing. Give me time - give me at any rate a year or so of happiness. I deserve it - you have tortured me enough in the past. Perhaps later I shall be able to be advanced and reasonable about your other friends. Then you can have other ships... Don't believe those advanced fools who tell you that love is free. It is not - it is a bondage, a beautiful bondage. We are bound to one another - you must love the bondage. How I hate your advanced philosopher self! Yes I hate that part of you - you have lately added hateful parts to yourself. If you really loved me you could not be so advanced. A person really in love is not advanced. I loathe your many ships idea... Also you would not call love-making vulgar if you were in love. You would not arrange for it only to happen three times a month."

In 1917, Dora Carrington set up home with Lytton Strachey at Mill House, Tidmarsh, in Berkshire. Her close friend, Dorothy Brett, was shocked by the decision: "How and why Carrington became so devoted to him I don't know. Why she submerged her talent and whole life in him, a mystery... Gertler's hopeless love for her, most of her friendships I think were partially discarded when she devoted herself to Lytton... I know that Lytton at first was not too kind with Carrington's lack of literary knowledge. She pandered to his sex obscenities, I saw her, so I got an idea of it. I ought not to be prejudiced. I think Gertler and I could not help being prejudiced. It was so difficult to understand how she could be attracted." Mark Gertler was furious when he heard the news and asked Carrington how she could "love a man like Strachey twice your age (36) and emaciated and old."

Carrington and Lytton Strachey did attempt a sexual relationship. She was willing to adapt to Strachey's homosexuality. However, she admitted in a letter to Strachey: "Hours were spent in front of the glass last night strapping the locks back, and trying to persuade myself that two cheeks like turnips on the top of a hoe bore some resemblance to a very well nourished youth of sixteen." Virginia Woolf assumed that Carrington was having a sexual relationship with Lytton Strachey. However, she recalled in her diary on 2nd July, 1918: "After tea Lytton and Carrington left the room ostensibly to copulate; but suspicion was aroused by a measured sound proceeding from the room, and on listening at the keyhole it was discovered that they were reading aloud Macaulay's Essays!"

According to David Garnett: "They (Dora Carrington and Lytton Strachey) became lovers, but physical love was made difficult and became impossible. The trouble on Lytton's side was his diffidence and feeling of inadequacy, and his being perpetually attracted by young men; and on Carrington's side her intense dislike of being a woman, which gave her a feeling of inferiority so that a normal and joyful relationship was next to impossible....When sexual love became difficult each of them tried to compensate for what the other could not give in a series of love affairs."

Julia Strachey was a regular visitor to the house. She later described the woman who was living with her uncle: "Carrington had large blue eyes, a thought unnaturally wide open, a thought unnaturally transparent, yet reflecting only the outside light and revealing nothing within, just as a glass door betrays nothing to the enquiring visitor but the light reflected off the sea... From a distance she looked a young creature, innocent and a little awkward, dressed in very odd frocks such as one would see in some quaint picture-book; but if one came closer and talked to her, one soon saw age scored around her eyes - and something, surely, a bit worse than that - a sort of illness, bodily or mental. She had darkly bruised, hallowed, almost battered sockets."

In the summer of 1918, her brother, Noel Carrington, introduced her to a friend, Ralph Partridge, who he had rowed with at the University of Oxford, while they were on holiday in Scotland. On 4th July she wrote to Lytton Strachey that "Partridge shared all the best views of democracy and social reform... I hope I shall see him again - not very attractive to look at. Immensely big. But full of wit, and recklessness." Strachey replied: "The existence of Partridge is exciting. Will he come down here when you return? I hope so; but you give no suggestion of his appearance - except that he's immensely big - which may mean anything. And then, I have a slight fear that he may be simply a flirt."

Gretchen Gerzina, the author of A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989), pointed out "Partridge was the opposite of the kind of man who normally attracted her. He was tall and broad-shouldered and, in spite of her critical assessment of his looks, very handsome. He was in many ways a man's man, who wore his uniform as if he was meant to and was an athlete. Her friends in Bloomsbury took to calling him the major, and wondered how to assimilate such a seemingly stereotypical and masculine member of the English upper middle classes into their circle. They were to find that he fitted in rather well."

Ralph Partridge went to live with Carrington and Lytton Strachey at Mill House. Carrington began an affair with Partridge. According to Strachey's biographer, Stanford Patrick Rosenbaum, they created: "A polygonal ménage that survived the various affairs of both without destroying the deep love that lasted the rest of their lives. Strachey's relation to Carrington was partly paternal; he gave her a literary education while she painted and managed the household. Ralph Partridge... became indispensable to both Strachey, who fell in love with him, and Carrington." However, Frances Marshall denied that the two men were lovers and that Lytton quickly realised that Ralph was "completely heterosexual".

In 1918 Lytton Strachey published Eminent Victorians (1918). The book was an irreverent look at the lives of Florence Nightingale, Thomas Arnold, Charles George Gordon and Henry Edward Manning. The historian, Gretchen Gerzina, has pointed out: "Not only did the book completely revise the art of biography from something long and dull to a quick-paced and creative form, but Lytton suddenly found himself a well-known and socially desirable character. Further he began to enjoy, for the first time in his life, a comfortable and independent income."

Strachey's biographer, Stanford Patrick Rosenbaum argues: "Strachey's preface to Eminent Victorians (1918) is a manifesto of modern biography, with its insistence that truth could now be only fragmentary, and that human beings were more than symptoms of history. The biographer's responsibility was to preserve both a becoming brevity and his own freedom of spirit, which for Strachey meant illustrating and exposing lives rather than imposing explanations on them.... Strachey's portraits are unified by a point of view that ironically juxtaposes the psychology and careers of his subjects."

Gerald Brenan, who had served with Ralph Partridge during the First World War, was a regular visitor to Mill House when he was in England. Brenan later described an early meeting with Dora: "Carrington came to the door and with one of her sweet, honeyed smiles welcomed me in. She was wearing a long cotton dress with a gathered skirt and her straight yellow hair, now beginning to turn brown, hung in a mop round her head. But the most striking thing about her was her eyes, which were of an intense shade of blue and very long-sighted, so that they took in everything they looked at in an instant."

Carrington now became a member of the Bloomsbury Group and a friend of Virginia Woolf, who wrote in her diary: "She (Dora Carrington) is odd from her mixture of impulse & self consciousness. I wonder sometimes what she's at: so eager to please, conciliatory, restless, & active. I suppose the tug of Lytton's influence deranges her spiritual balance a good deal. She has still an immense admiration for him & us. How far it is discriminating I don't know. She looks at a picture as an artist looks at it; she has taken over the Strachey valuation of people & art; but she is such a bustling eager creature, so red & solid, & at the same time inquisitive, that one can't help liking her."

Frances Marshall was a close friend of Dora Carrington during this period: "Her love for Lytton was the focus of her adult life, but she was by no means indifferent to the charms of young men, or of young women either for that matter; she was full of life and loved fun, but nothing must interfere with her all-important relation to Lytton. So, though she responded to Ralph's adoration, she at first did her best to divert him from his desire to marry her. When in the end she agreed, it was partly because he was so unhappy, and partly because she saw that the great friendship between Ralph and Lytton might actually consolidate her own position."

In the summer of 1920 Ralph Partridge began work for Virginia Woolf and Leonard Woolf at the Hogarth Press. This gave him enough money to marry Carrington on 21st May 1921. She wrote to Lytton Strachey on her honeymoon: "So now I shall never tell you I do care again. It goes after today somewhere deep down inside me, and I'll not resurrect it to hurt either you or Ralph. Never again. He knows I'm not in love with him... I cried last night to think of a savage cynical fate which had made it impossible for my love ever to be used by you. You never knew, or never will know the very big and devastating love I had for you ... I shall be with you in two weeks, how lovely that will be. And this summer we shall all be very happy together."

Carrington gradually realised she was a lesbian. In 1922 she spent time with an aristocratic friend, Phillis Boyd, who was just about to marry Henri de Janze. She admitted in a letter to Gerald Brenan that she found Boyd "immoral, but full of character and terribly attractive" She added: "I actually suffered torments because I longed to possess her in some vague way. To make her realise somehow that I was important to her. But she only prattled away in her bed, about her chateau in Normandy, her parents, her past lovers, and the scandals of London."

In 1924 Strachey purchased Ham Spray House in Ham, Wiltshire, for £2,100. Dora and Ralph were invited to live with Strachey. According to Michael Holroyd, the author of Lytton Strachey (1994): "Ham Spray House had no drains or electric light and was in need of general repairs... The builders started work there in early spring... Even with some help from a legacy which Ralph had received on his father's death, it was all turning out to be fearfully expensive." Later, the loft at the east end of the house was converted into a studio for Carrington.

Although Gerald Brenan continued to live in Yegen, whenever he was in England he stayed in Ham Spray House. A friend, Frances Marshall later recalled: "Gerald Brenan, a great friend of Ralph's from the war, and here it was that Gerald and Carrington - who had met before, and indulged in a light flirtation - finally fell in love." Gretchen Gerzina, the author of A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989), has argued: "Gerard agonised. Wanting more than anything to make love to her, he feared that importance would overcome him, causing not only sexual failure but embarrassment. He spent the night awake and miserable, and early the next morning crept down to her room to explain himself. Sitting unhappily on the edge of Carrington's bed, he found her completely understanding and sympathetic."

They became lovers. Brenan's biographer has argued: "His love affair with Dora Carrington was far the most serious in his life, producing as it did an enormous two-way correspondence, some ecstasy, and considerable unhappiness on both sides. Otherwise he was obsessed by sex, and inhibited by fears of impotence. A stream of prostitutes, hippies, and peasant girls occupied his agitated thoughts and feelings and directed his travels."

Frances Marshall fell in love with Ralph Partridge. She later recalled: "He was a tall, good-looking and very broad-shouldered man.... His remarkably blue eyes never seemed quite still, conveyed an impression of great vitality held in check with difficulty, and often flashed in my direction, as I couldn't help observing." Virginia Woolf was also fond of Ralph describing him as having "an ox's shoulders and a healthy brain".

Michael De-la-Noy has pointed out: "It was not long before Frances Marshall found herself entangled in another extraordinary ménage à trois, at Tidmarsh, where Lytton Strachey was in love with the literary journalist Ralph Partridge, Partridge with the painter Dora Carrington, and Carrington, most improbably of all, with the quite obviously homosexual Strachey." By this time Carrington stopped having a sexual relationship with Partridge.

David Garnett was another man who fell in love with Carrington: "When she talked to me she seemed to be confiding a secret, and I was flattered. She made me feel like a child and she was a child herself. She had indeed many of the childish, or adolescent characteristics that afflict girls at puberty. She never overcame her shame at being a woman, and her letters are full of references to menstruation. Although her sexual desire had greatly increased between her affair with Mark Gertler and that with Gerald Brenan, and although she was in love with Brenan as she had never been with Gertler, they follow a curiously similar pattern: almost the same deceptions, excuses and self-accusations are repeated in each relationship. And in each it was the hatred of being a woman which poisoned it."

Carrington developed several strong emotional relationships with women. Her most passionate affair was with Henrietta Bingham, an American who was a student at the London School of Economics. After her first visit to Ham Spray House, Carrington commented that this lovely creature "wandered around the house taking about as much interest in me if I'd been the housekeeper!" The author of A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 has argued: "For the first time in her life, Carrington was in active pursuit of a particular lover. Men had always been attracted to her, but she had never taken on the chase herself."

The two women became lovers. She wrote to her friend, Alix Strachey: "Really I confess Alix I am very much more taken with Henrietta than I have been with anyone for a long time. I feel now regrets at being such a blasted fool in the past, to stifle so many lusts I had in my youth, for various females. But perhaps one would have only have been embittered, or battered by blows on the head from enraged virgins. Unfortunately she is living in London now with a red haired creature from America." Bingham told Carrington: "You must wait, if you can. My passions don't last long."

Carrington eventually began an intense affair with Henrietta Bingham. Michael Holroyd, the author of Lytton Strachey (1994), has argued: "Henrietta went about the breaking the hearts of many men and women. Her enigmatic smile, caressing syllables, glowing skin, held no appeal for Lytton who sensed her destructive powers." In a letter sent to Gerald Brenan on 27th September 1924: "Henrietta Bingham said on the telephone she would come & see me off (from Paddington station). So I dashed up & down the platform looking for her. No sign of her, & one minute for my train to start. All the windows blocked with beastly little school girls saying goodbye to parents. The platform crowded. I felt it was some terrible dream & that I would go mad. Suddenly in the distance I saw Henrietta walking down the platform very slowly with that enigmatic smile on her face - I pushed the school girls from the carriage door brushed through the parents & dashed towards her. The smoothness of her cheeks again returned, & I remembered nothing but that she is more lovely to me than any other woman. We talked for one minute I leap into the train. She kissed me fondly, & the train moved away."

Henrietta Bingham

Jane Hill, the author of The Art of Dora Carrington (1994), pointed out: "Carrington made two frankly erotic, sensual drawings of women in the mid 1920s, which are completely winning. In pen and ink, using a very fine nib, like the hardest pencil, Carrington drew Henrietta in a most revealing and unselfconscious stance. The attitude of her right arm is beautifully drawn and the fetishistic addition of shoes makes her nudity nakedness." Carrington was devastated when Bingham dropped her. According to Ernest Jones, who psychoanalysed Bingham, "the real reason why she threw over Carrington was because she wasn't a virgin."

Henrietta Bingham now began an affair with Carrington's friend, Stephen Tomlin. In July 1924 Tomlin took Henrietta to Scotland. Carrington wrote to Gerald Brenan complaining that "Henrietta repays my affections almost as negatively as you find I do yours." Her friend, Julia Strachey, commented that sexual guilt "surrounded her (Carrington) like a cloud of mosquitoes wherever she went."

Carrington continued to write to Brenan but decided she did not want to continue their sexual relationship. When he complained she replied on 19th March, 1925: "You are again I see going to press in a direction which will cause difficulties. Every sentence of your post script confirms what I felt only too acutely last winter. That by becoming your lover I would make the situation more difficult. Because the responsibilities would be greater. Since our relations are circumscribed because my life is so arranged that I can only give you a small portion of it it is a very difficult matter the arranging of that portion... I tell you there are few things that hurt me more than to think I am cared for just because of sex. The whole difficulty in my relation with Mark Gertler was always that he could take little interest in seeing me unless he made love... If you find no point in seeing me because you cannot make love to me, you have only not to see me. But I refuse to be intimidated by your saying before hand you are going to make a scene. You know making you unhappy doesn't give me pleasure."

In another letter dated 21st September 1925, Carrington argued: "It is simply another proof of our fundamental difference of character. I wish to bury the past, you have an infinite capacity for investigating it. I do not believe any particular circumstances made our relation impossible. It was rather my predestined inability, (which whenever I think of my past life is forced upon me), to have any intimate relations with anyone. I believe I am a perfect combination of a nymphomaniac and a wood-nymph! I hanker after intimacies, which another side of my nature is perpetually at war against. Lately, removed from any intimacies, causing no one unhappiness and having no sense of guilt I have felt more at peace inside myself than I have ever felt before." Gerald Brenan replied that the sex act was a natural outgrowth of mutual fondness, that one "cannot separate in this way the intellectual and the physical." However, she disagreed and that aspect of their relationship came to an end.

In 1926 Carrington began an affair with Stephen Tomlin. According to Michael Holroyd, the author of Lytton Strachey (1994): "Tomlin, being bisexual, for a brief spell occupied a virtuoso position in the Ham Spray régime." Ralph Partridge strongly objected to Tomlin having an affair with Carrington, "fearing he was someone more likely to destroy than to create happiness." The affair came to an end when Julia Strachey married Tomlin in July 1927. The married couple rented a stone cottage at Swallowcliffe in Wiltshire. Carrington was a regular visitor: "Really its equal to Ham Spray in elegance and comfort, only cleaner and tidier."

Stephen Tomlin and Dora Carrington

Carrington enjoyed a close relationship with Alix Strachey, who she had attempted to seduce. She wrote in December 1928: "I send you my love. I wish it was for some use." She also had similar feelings for Julia Strachey. She told Gerald Brenan that she was strongly attracted to Julia and that she was "sleeping night after night in my house, and there's nothing to be done, but to admire her from a distance, and steal distracted kisses under cover of saying goodnight." In October 1929 she sent a letter to her complaining: "Julia, I wish I was a young man and not a hybrid monster, so that I could please you a little in some way, with my affection. You know you move me strangely. I remember for some reasons every thing you say and do, you charm me so much."

Dora Carrington wrote in her diary in 1929 that her sexual relationships were having a detrimental impact on her art. "I would like this year (since for the first time I seem to be without any relations to complicate me) to do more painting. But this is a resolution I have made for the last 10 years." However, later that year she began a relationship with Beakus Penrose, the younger brother of Roland Penrose. Her biographer, Gretchen Gerzina, has argued: "She may have found a sexual awakening with Henrietta - and there is no evidence that she ever had another woman as a lover - but ultimately it was a romance with a man she craved."

Mark Gertler married Marjorie Greatorex Hodgkinson, a former Slade School student, on 3rd April 1930. Carrington sent the couple a wedding gift. He replied that he had recently re-read her letters: "It certainly made most moving reading. It must have been a most extraordinary and painful time for both of us. But we were both very young and probably unsuited. And it is over now and nobody's fault."

In 1931 Lytton Strachey became extremely ill. He had a fever that would not go away and constantly felt tired. At first he was diagnosed as having typhoid. He then saw another specialist who suggested it was ulcerative colitis. Frances Marshall pointed out: "In those days bulletins were published in the daily papers mentioning the progress of well-known people's illnesses. Lytton rated this degree of importance and the press often rang up, though the nice lady at the local exchange dealt with their queries and kept them supplied with news... On Christmas Day 1931 he was given up for dead. In the evening he made an astonishing recovery from near-unconsciousness."

On 19th January 1932, Dora Carrington asked the nurse who was caring for him if there was any chance that he might survive the illness. She replied: "Oh no - I don't think so now". Soon afterwards she went into the garage and tried to kill herself. However, during the night Ralph Partridge went looking for her and "found her in the garage with the car engine running, rushed in and dragged her out".

Lytton Strachey died of undiagnosed stomach cancer on 21st January 1932. His death made her suicidal. She wrote a passage from David Hume in her diary: "A man who retires from life does no harm to society. He only ceases to do good. I am not obliged to do a small good to society at the expense of a great harm to myself. Why then should I prolong a miserable existence... I believe that no man ever threw away life, while it was worth keeping."

According to Michael Holroyd, the author of Lytton Strachey (1994): "Of all the friends he (Ralph Patridge) invited to Ham Spray it was Stephen Tomlin who appeared most successful in halting her from making another attempt at suicide." Carrington wrote in her journal: "He (Tomlin) persuaded me that after a serious operation or fever, a man's mind would not be in a good state to decide on such an important step. I agreed - so I will defer my decision for a month or two until the result of the operation is less acute." After he returned home, Carrington wrote to him: "You made this last week bearable which nobody else could have done. Those endless conversations were not quite pointless."

She kept a journal where she tried to communicate with Lytton Strachey. On 12th February 1932 Carrington wrote: "They say one should keep your standards & your values of life alive. But how can I when I only kept them for you. Everything was for you. I loved life just because you made it so perfect & now there is no one left to make jokes with or talk to... I see my paints, & think it is no use for Lytton will never see my pictures now, & I cry. And our happiness was getting so much more. This year there would have been no troubles, no disturbing loves... Everything was designed for this year. Last year we recovered from our emotions, & this autumn we were closer than we had ever been before. Oh darling Lytton you are dead & I can tell you nothing."

Frances Marshall was with Ralph Partridge when he received a phone-call on 11th March 1932. "The telephone rang, waking us. It was Tom Francis, the gardener who came daily from Ham; he was suffering terribly from shock, but had the presence of mind to tell us exactly what had happened: Carrington had shot herself but was still alive. Ralph rang up the Hungerford doctor asking him to go out to Ham Spray immediately; then, stopping only to collect a trained nurse, and taking Bunny with us for support, we drove at breakneck speed down the Great West Road.... We found her propped on rugs on her bedroom floor; the doctor had not dared to move her, but she had touched him greatly by asking him to fortify himself with a glass of sherry. Very characteristically, she first told Ralph she longed to die, and then (seeing his agony of mind) that she would do her best to get well. She died that same afternoon."

According to Beatrice Campbell, when Mark Gertler heard the news, "He was so shattered that he felt that nothing but a revolver could end his pain. He went out to buy one, but found it was Saturday afternoon and all the shops were shut." Gertler did later commit suicide in his studio on 23rd June 1939. Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary: "Glad to be alive and sorry for the dead: can't think why Carrington killed herself and put an end to all this." However, ten years later she followed Carrington's example and killed herself.

Gerald Brenan wrote to Alix Strachey about the death of Carrington: " It was proved (at the inquest) that her last letter to Ralph, found in the drawer, was written within three days of that Friday. Then instead of wearing her own yellow dressing gown, she put on Lytton's purple one and died in that. It was a kind of ritual act... She killed herself mainly, I think, to emphasise the importance of Lytton's death but time races away from that Friday and soon very few people will ever remember it. I do not know whether great tragic acts occur out of literature, but this, I feel, was not one but something childish and thoughtless and pitiful. Or perhaps it is merely that I am obliged to go on reproaching her - for the last act as for so many other acts of her life."

Primary Sources

(1) Noel Carrington, Carrington (1970)

He (my father) had always been unconventional in dress: equally in the friends he made and the standards he set. He was charitable and uninteresting in gossip. We could not help noticing that those few old Anglo-Indian friends who visited him spoke of him with glowing admiration. One of them told us how in a famine he had fed a whole district from his own resources. And this was not entirely a myth, as I recently discovered from his letters. He in his turn was so loyal to his friends that for many years an old Welsh doctor lived with us, our father declaring that the man who had once saved his life should never lack a home.

Our mother, on the other hand, was cast in a different mould, and her virtues seemed less and less commendable as we grew older. She was obsessed at all times with "what people would think". She was lame and rheumatic but indefatigable in doing what she conceived to be her duty, which was to oversee what her children and the servants were doing. On the occasion of the slightest lapse we would be reminded that she had given up everything to bring us up in a God-fearing way. That children must grow up, become individuals in their own right, form their own friendships and way of life, was a thought that she could never bring herself to accept. Keeping secrets from one's parents was almost the ultimate sin. Even before she went to London Carrington's friendships and letter-writing became a source of disturbance, especially as she was incurably careless in leaving letters insecurely hidden. As the older members of the family left home to take up careers, so our mother's determination to keep the family together became concentrated on the two last and youngest, Carrington and myself.

The art mistress of her school at Bedford had suggested that the Slade was the only proper place for Carrington's talents to develop. Family pride induced our mother to fall for this notion, which she afterwards professed to regret. To guard against the notorious dangers of London life, Carrington was placed at Byng House in Gordon Square, a hostel with a reputation for respectability and discipline. After a year she was able to persuade the family that the food was unhealthy-a sure argument for parents-with the result that she and her elder sister, now a nurse at a London hospital, were allowed to share a little house off Regent's Park. She never had much in common with her sister, but a convenient neutrality was observed.

The Slade at that time was probably at its peak as a teaching school, with Steer, Brown and Tonks on the staff; Tonks in particular was a dominating and even intimidating figure. Carrington's conversation was soon full of this trinity, with the names of John and McEvoy also spoken with reverence. To our mother's circle the only Mecca for artists was still the Royal Academy which, of course, Carrington treated with disdain. She might try, she said, for the London Group or perhaps the New English, institutions of which Bedford had never heard. Amongst the men students were Stanley and Gilbert Spencer, the Nash brothers, Bomberg, Nevinson and Gertler. Amongst the girls her particular friends were Ruth Humphries, daughter of a Bradford printer, Brett, the daughter of Lord Esher, Lynton and Barbara Hiles.

What irked her most each time she came home were conventions she no longer believed in and to which she felt reasonable people elsewhere no longer conformed. To conform under such circumstances was hypocritical. There were two principal conventions which our mother had inherited. The first was extreme prudishness. Any mention of sex or the common bodily functions was unthinkable. We were not even expected to know that a woman was pregnant. Even a word like "confined" was kept to a whisper. The second was church-going and behaviour on Sunday. We all came to hate the whole atmosphere of a Sunday morning. The special clothes, the carrying of prayer books, the kneeling, standing and murmuring of litanies. Yet to lead her family up the aisle, especially on Easter Sunday for communion, was to our mother the true reward of righteousness. I believe Carrington would have refused point-blank to bend the knee had it not been that it would have bitterly grieved our father.

Apart from her disgust with what Gilbert Cannan described as the "meaningless radiation of gentility", new friendships were effecting another change which was to be probably of greater importance in her future: this was a desire to educate herself in those areas of knowledge - literature and history in particular - which she had hitherto neglected. I found that my text books were being borrowed and not always returned. When sitting as a model, my brains were picked over for any useful information. It was not all "take": in return I was forcibly educated in Art, according to the creeds then held at the Slade. For this I should have been grateful. An essay on the all-embracing virtue of "Significant Form" was decisive in gaining me an open scholarship in History, my examiners being unaware that it was virtually lifted from a recent work of Clive Bell. If Carrington was tireless herself in the quest of knowledge at this time, she also never wearied of improving her brothers' too-conventional minds.

After each term in London the disparity between her home life and what was opening before her became more frustrating. Gradually she devised a makeshift system of alibis, based on painting commissions or visits to approved friends. All this led to a complicated calendar of deceptions which became a second habit even when no longer necessary. Quite apart from our father's feelings, she was economically dependent on the family, so that evasion was preferable to defiance.

There was one occasion when deception could not be practised. This was when she arrived home with her hair cut short or bobbed. She said she had needed to have it cut to fit her costume at a fancy-dress party, but it may have been for other reasons, perhaps psychological. Short hair for girls was then virtually unknown and unheard of at Bedford. Thus it was read as a declaration of audacity and independence and one, alas, which could not be concealed. For a long while our mother continued to lament the loss of "such beautiful hair" as if it were a family rather than a personal possession. I think it impressed on us that something had happened to mark her off as different from the rest, an unmistakable assertion of personality. From that moment her mother began to treat her with a trace of caution in her reprimands, even though she could not restrain her inquisitiveness or gestures of pained disapproval.

By nature Carrington was warm-hearted and affectionate. These feelings were denied expression with her parents once she had left home. With her mother, who survived her by some ten years, neither understanding nor reconciliation was possible. Her father may be supposed to have understood her more than he was able to show in life, for in his will he left her a modest but independent income. One further consequence of the conflict was that she developed a repugnance for family life as such. As her own friends in turn came to marry she was apt to treat it as a lapse from grace, with maternity an inevitable but none the less deplorable sequel for a person of intelligence.

(2) (2)Christopher Nevinson, letter to Dora Carrington (19th June, 1912)

I am now without a friend in the whole world except you.... I cannot give you up, you have put a reason into my life and I am through you slowly winning back my self-respect. I did feel so useless so futile before I devoted my life to you... I am aching for the companionship of Gertler, our talks on Art, on my work, his work and our life in general. God how fond of him I am. I never realised it so thoroughly till now....

If you still find it absolutely necessary to chuck me, remember should you ever need any help or companionship do please come back to me as I know I shall always like and respect you for the rest of my life. I most admire your self-control and grit to throw away a great deal of your happiness for your work even though I consider you are horribly wrong in doing so.

(3) (3)Mark Gertler, letter to Dora Carrington (7th July 1912)

In order to make you understand let me tell you for once always. You are no doubt extremely ignorant that way. Nature, forcibly takes hold of a man, places him on a road where she knows his ideal will pass. She passes: He loves her: madly, horribly, and uncontrollably. Not content with this, Nature implants him with a desire (no doubt for the sake of the preservation of the next generations) to wholly and absolutely honour that woman. This causes him to be jealous of everything she does with other people. He can't stand seeing her own mother kiss her, let alone another man. Of course as I said, it is not for me to tell you who to kiss or who not to kiss, nor will you take any notion of me if I did. The only thing is you mustn't tell me about these things as I can't bear it. I shall try and suffer quietly & alone in future though. Of course it is absurd to ask me to try and be friends with Nevinson, do you think I am made of stone? That I should be friends with the man who kisses my girl.

(4) (4)Mark Gertler, letter to Dora Carrington (December, 1912)

Yes, my isolation is extraordinary. I am alone, alone in the whole of this world! Yes, if only like my brothers I was an ordinary workman as I should have been. But no! I must desire, desire. How I pay for those desires! Oh! God! Do I deserve to be so tormented? By my own ambitions I am cut off from my own family and class and by them I have been raised to be equal to a class I hate! They do not understand me nor I them. So I am an outcast. As I look at my desk I laugh, for there are dozens of notices of me in the daily papers, a lot of them praising my talents. Oh! yes I am quite well known, and yet alone.

(5) Mark Gertler, letter to Christopher Nevinson (December 1912)

I am writing here to tell you that our friendship must end from now, my sole reason being that I am in love with Carrington and I have reason to believe that you are so too. Therefore, much as I have tried to overlook it, I have come to the conclusion that rivals, and rivals in love, cannot be friends.

You must know that ever since you brought Carrington to my studio my love for her has been steadily increasing. You might also remember that many times, when you asked me down to dinner. I refused to come. Jealously was the cause of it. Whenever you told me that you had been kissing her, you could have knocked me down with a feather, so faint was I. Whenever you saw me depressed of late, when we were all out together, it wasn't boredom as I pretended but love.

(6) (6)Paul Nash, letter of Michael Reynolds (c. 1970)

Carrington... was the dominating personality, and when she cut her thick gold hair into a heavy golden bell, this, her fine blue eyes, her turned-in toes and other rather quaint but attractive attributes, combined

to make her a conspicuous and popular figure... I had noticed her long before this was achieved, when as a bored sufferer in the Antique Class my attention had been suddenly fixed by the sight of this amusing person with such very blue eyes and such incredibly thick pigtails of red-gold hair. I got an introduction to her and eventually won her regard by lending her my braces for a fancy-dress party. We were on the top of a bus and she wanted them then and there.

(7) (7)Gretchen Gerzina, A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989)

During their absence from one another at this time the issue of their sexual relations - or more precisely, the lack of them - again was raised. Gertler felt that he had been more than patient and understanding during the last three years; it was time for her to put aside her girlish fears and have an adult relationship with him. She was, after all, nearly twenty-one-years old. In her turn, Carrington felt that he ought to accept her friendship on her terms. She raised no moral objections to sex, but felt herself absolutely incapable of such acts, and without any desire for them. They made her feel unclean and ashamed. Gertler tried to argue her down; since passion would not sway her, perhaps reason would.

(8) (8)Mark Gertler, letter to Dora Carrington (2nd January 1914)

There can be no real friendship between us, as long as you allow that Barrier - Sex - to stand between us. If you care so much for my friendship, why not sacrifice, for a few moments, your distaste for Physical contact & satisfy me? Then we could be friends. Then I could love no one more than my friend - then I could share all with you.

I am doing work now, which is real work. Far better than anything I have done before & I would like you to share it with, but as long as that obsession for you sexually is there, I cannot. Remember I tried to fight it for three years, without success. Now it cannot go on any longer.... I am not ashamed of my sexual passion for you. Passion of that sort, in the case of love, is not lustful, but Beautiful!

(9) (9)Albert Rutherston, letter to Dora Carrington (17th May 1914)

Carrington please never believe for an instant that anybody in the world could say or for a moment think seriously, that you gave me the slightest encouragement to think of you save as a friend. I knew always & realised that you regarded me entirely in this light - if it hadn't been for this knowledge, then I would have told you myself before other folks made you realise that it wasn't quite so & that I cared for you differently ... Carrington it wasn't that I didn't wish & long to speak to you but that it was impossible, knowing you to be entirely innocent that I cared for you rather more than I ought to. I'm wretchedly sorry... I've loved you & all of you, yes, your talent, your delightful insight & wit, & your presence & friendship have brought me golden hours & perhaps great hope & all this given thought I knew that in your eyes I was simply a friend... I feel you will understand me a little & forgive my clumsiness & it's all so odd & nothing would have made me tell you, knowing how you felt if this muddle hadn't come about.

(10) Vanessa Curtis, Virginia Woolf's Women (2002)

Carrington's family situation eased slightly in 1914 when the Carringtons moved to a Georgian farmhouse in Hurstbourne Tarrant, Hampshire. There were enough outbuildings for Carrington to have her own studio, and here she began her love affair with the landscapes and scenery of the countryside, first capturing the view from her top-floor bedroom in an evocative watercolour entitled Hill in Snow at Hurstbourne Tarrant (1916).The other love affair that began at this time was with a fellow student, Mark Gertler, whom Carrington had met at the Slade just before graduating. Their twelve-year long friendship, which started so optimistically with shared trips to galleries and exhibitions, became troubled very quickly and caused both of them much unhappiness. Although passionate towards Gertler when discussing art, Carrington, at eighteen, had not yet had her sexuality awakened; her upbringing had taught her to repress her innermost feelings. She was looking for a platonic soul mate, but what she found was a man who was highly sexed and constantly irritated and frustrated by Carrington's lack of passion. The heartbreaking letters that passed regularly between them pay sad testimony to the anguish that this long relationship caused. On graduating from the Slade, Carrington had fallen into an unhappy, confused state. She was unsure of her own identity, haplessly seeking somebody who would restore it to her. That somebody, a fellow guest at Virginia Woolf's country home, Asheham, was to be Lytton Strachey.

Strachey, along with Clive Bell, Duncan Grant and Mary Hutchinson, had been staying at Asheham, which Virginia had just leased jointly with Vanessa Bell. Attracted to Carrington from the I moment he first laid eyes on her, he had boldly tried to kiss her during a walk across the South Downs, the feeling of his beard prompting an enraged outburst of disgust from the unwilling recipient. According to legend, Carrington plotted frenzied revenge, creeping into Lytton's bedroom during the night with the intention of cutting off the detested beard. Instead, she was mesmerized by his eyes, which opened suddenly and regarded her intently. From that moment on, the two became virtually inseparable.

Initially, Strachey's friends viewed the idea of Carrington and Lytton as a couple with repulsion; it was considered extremely inappropriate. Even though it was evident almost from the start that they were to enjoy a platonic relationship rather than a sexual one, the relationship was the talk of Bloomsbury for several months. They were a curious looking couple: Lytton was tall and lanky, bespectacled and with a curiously high-pitched voice, Carrington was short, chubby, eccentrically dressed and with daringly short hair.

(11) (11)David Garnett, The Flowers of the Forest (1955)

Lawrence was dangerously silent and I foresaw an explosion in which he would turn his wrath on Frieda. Fortunately before it came, the door opened and two other visitors entered - a dark handsome young Jewish painter, called Mark Gertler, and a girl to whom I was at once powerfully attracted. Her thick hair, the colour of a new wheat straw thatch, was cut pudding-basin fashion round her neck and below her ears. Her complexion was delicate, like a white-heart cherry; a curious crooked nose gave character to her face and pure blue eyes made her appear simple and childish when she was in fact the very opposite. Her clothes labelled her an art-student and she was in fact, like Gertler, at the Slade. She concealed her Christian name, which was Dora, and was always called by her surname, Carrington... My interest in her was returned, though I did not know it, and later we became warm friends until her death. On this occasion, she scarcely spoke but sat down on the floor to listen, at intervals stealing critical looks at each of the company in turn out of her forget-me-not blue eyes.

(12) Michael Holroyd, Lytton Strachey (1994)

He (Mark Gertler) did not know where he was, and in his bafflement began discussing his troubles with D.H. Lawrence, Gilbert Cannan, Aldous Huxley, Ottoline Morrell and others. So he and Carrington were to find their way into the literature of the times. In Aldous Huxley's Crome Yellow (1921) Gertler becomes the painter Gombauld, "a black-haired young corsair of thirty, with flashing teeth and luminous large dark eyes"; while Carrington may be seen in the "pink and childish" Mary Bracegirdle, with her clipped hair "hung in a bell of elastic gold about her cheeks", her "large china blue eyes' and an expression of "puzzled earnestness". In D.H. Lawrence's Women in Love (1921), some of Gertler's traits are used to create Loerke, the corrupt sculptor to whom Gudrun is attracted (as Katherine Mansfield was to Gertler), while Carrington is caricatured as the frivolous model Minette Darrington - and Lytton too may be glimpsed as the effete Julius Halliday. Lawrence became fascinated by what he heard of Carrington. Resenting the desire she had provoked and refused to satisfy in his friend Gertler, he took vicarious revenge by portraying her as Ethel Cane, the gang-raped aesthete incapable of real love, in his story None of That. "She was always hating men, hating all active maleness in a man. She wanted passive maleness." What she really desired, Lawrence concluded, was not love but power. "She could send out of her body a repelling energy," he wrote, "to compel people to submit to her will." He pictured her searching for some epoch-making man to act as a fitting instrument for her will. By herself she could achieve nothing. But when she had a group or a few real individuals, or just one man, she could "start something", and make them dance, like marionettes, in a tragi-comedy round her. "It was only in intimacy that she was unscrupulous and dauntless as a devil incarnate," Lawrence wrote, giving her the paranoiac qualities possessed by so many of his characters. "In public, and in strange places, she was very uneasy, like one who has a bad conscience towards society, and is afraid of it. And for that reason she could never go without a man to stand between her and all the others."

(13) Julia Strachey, Carrington: A Study of a Modern Witch (2000)

Carrington had large blue eyes, a thought unnaturally wide open, a thought unnaturally transparent, yet reflecting only the outside light and revealing nothing within, just as a glass door betrays nothing to the enquiring visitor but the light reflected off the sea... From a distance she looked a young creature, innocent and a little awkward, dressed in very odd frocks such as one would see in some quaint picture-book; but if one came closer and talked to her, one soon saw age scored around her eyes - and something, surely, a bit worse than that - a sort of illness, bodily or mental. She had darkly bruised, hallowed, almost battered sockets.

(14) (14)Dorothy Brett, letter to Michael Holroyd, quoted in Lytton Strachey: A Biography (1971)

How and why Carrington became so devoted to him I don't know. Why she submerged her talent and whole life in him, a mystery... Gertler's hopeless love for her, most of her friendships I think were partially discarded when she devoted herself to Lytton... I know that Lytton at first was not too kind with Carrington's lack of literary knowledge. She pandered to his sex obscenities, I saw her, so I got an idea of it. I ought not to be prejudiced. I think Gertler and I could not help being prejudiced. It was so difficult to understand how she could be attracted.

(15) Dora Carrington, letter to Mark Gertler (16th April 1915)

You wrote these last lines only a week ago, and now you tell me you were "hysterical and insincere".

Only I cannot love you as you want me to. You must know one could not do, what you ask, sexual intercourse, unless one does love a man's body. I have never felt any desire for that in my life: I wrote only four months ago and told you all this, you said you never wanted me to take any notice of you when you wrote again; if it was not that you just asked me to speak frankly and plainly I should not be writing. I do love you, but not in the way you want.... Can I help it? I wish to God I could. Do not think I rejoice in being sexless, and am happy over this. It gives me pain also.

(16) (16)Beatrice Elvery, Today We Will Only Gossip (1964)

Pulling the curtains apart, I saw the whole sky was crimson and all the houses and trees lit up. I went down the stairs like an avalanche, gasping, "Zeppelin coming down - burning". Carrington shot out of her room, and we both clawed at the hall-door and dashed out into Norfolk Road. There it was, creeping and dripping down the sky, head first, mighty and majestic, a great flaming torch, and away above it the little light of the plane, signalling to the guns. There was an Artillery barracks at the end of our road. The great roars of cheering, rising and falling in crescendo and diminuendo, came from there, but it sounded as if all London was cheering.

Carrington burst into terrible sobbing and rushed back to her room. I felt almost unconscious with excitement, and was on a plane of living where human suffering no longer existed. It looked as if the remains of the Zeppelin had come down on Hampstead Heath, though in reality it was much farther off, in rural Essex. I wanted to get a taxi and go to where it had fallen, and went to Carrington to get her to come with me, but she was crying so bitterly she could not speak, so I left her.

(17) Dora Carrington, letter to Mary Ruthentall (6th December 1915)

Duncan Grant was there who is much the nicest of them and Strachey with his yellow face and beard. Ugh! ... We lived in the kitchen and cooked and ate there... Everyone devoid of table manners. The vaguest cooking insued. Duncan earnestly putting remnants of milk pudding into the stockpot ... What poseurs they are really!

(18) Dora Carrington, letter to Mark Gertler (December 1915)

I have just come back from spending three days on the Lewes downs with the Clive Bells, Duncan Grant, Mrs Hutchinson and Lytton Strachey. God knows why they asked me!! It was much happier than I expected. The house was right in the middle of huge wild downs, four miles from Lewes, and surrounded by a high hill on both sides with trees. We lived in the kitchen for meals, as there weren't any servants, so I helped Vanessa Bell cook. Lytton is rather curious. I got cold, and feel rather ill today. They had rum punch in the evenings which was good. Yesterday we went a fine walk over tremendous high downs. I walked with Lytton. I like Duncan, even if you don't! What traitors all these people are! They ridicule Ottoline! even Mary Hutchinson laughs at the Cannans with them. It surprises me. I think it's beastly of them to enjoy Ottoline's kindnesses and then laugh at her.

(19) Dora Carrington, letter to Mark Gertler (December 1915)

What a damned mess I make of my life and the thing I want most to do, I never seem to bring off. My work disappoints me terribly. I feel so good, so powerful before I start and then when it's finished, I realise each time, it is nothing but a failure. If only I had any money I should not be obliged to stick at home like this. And to earn money every day, and paint what one wants to, seems almost impossible.

Yesterday I walked over to Rottingdean over the downs with Noel. l It was lovely country. I am afraid I shall never really get intimate with him; he is so governed by conventions, and accepts the "public school" opinions. It's a pity, perhaps he will get out of it in time. You would like him, but it wouldn't be any use now because he's so patriotic, that I am sure you would hate him, and he you! It's a good thing Eddie Marsh doesn't know him, for he's almost as beautiful as Rupert Brooke. I wonder who all the Baronesses are who you are meeting?

(20) (20)Mark Gertler, letter to Dora Carrington (27th February 1916)

The reason is that we both have different ways of reaching it. And the two ways are so different that they clash and fight and they always will clash and fight so that we shall therefore never be able to succeed together. Your way of reaching that state of spirituality is by leaving out sex. My way is through sex. Apparently we neither of us can change our ways, because they are ingrained in our natures. Therefore there will always be strife between us and I shall always suffer.

(21) (21)Mark Gertler, letter to Dora Carrington (December 1916)

For God's sake don't torture me by not letting me see much of you - I must see you very often. I shan't worry you for much "sugar" if only I can see you and talk - I must, I must. And if any other man touches any part of your beautiful body I shall kill myself - don't forget that! I could not bear such a thing. Give me time - give me at any rate a year or so of happiness. I deserve it - you have tortured me enough in the past. Perhaps later I shall be able to be "advanced" and reasonable about your other friends. Then you can have other ships... Don't believe those `advanced' fools who tell you that love is free. It is not - it is a bondage, a beautiful bondage. We are bound to one another - you must love the bondage. How I hate your "advanced" philosopher self! Yes I hate that part of you - you have lately added hateful parts to yourself. If you really loved me you could not be so advanced. A person really in love is not advanced. I loathe your many ships idea... Also you would not call love-making "vulgar" if you were in love. You would not arrange for it only to happen three times a month...

I hate you for three things: 1. Because you can't love passionately. 2. Because of your advanced ideas.

3. I hate you because I love you and am therefore in the power of your cruel, advanced and unpassionate self!

(22) (22)Virginia Woolf, diary entry (6th June 1918)

She (Dora Carrington) is odd from her mixture of impulse & self consciousness. I wonder sometimes what she's at: so eager to please, conciliatory, restless, & active. I suppose the tug of Lytton's influence deranges her spiritual balance a good deal. She has still an immense admiration for him & us. How far it is discriminating I don't know. She looks at a picture as an artist looks at it; she has taken over the Strachey valuation of people & art; but she is such a bustling eager creature, so red & solid, & at the same time inquisitive, that one can't help liking her.

(23) (23)Virginia Woolf, diary entry (16th August 1918)

Carrington came for the weekend. She is the easiest of visitors as she never stops doing things - pumping, scything, or walking. I suspect part of this is intentional activity, lest she should bore; but it has its advantages. After trudging out here, she trudged to Charleston... She trudged off again this morning to pack Lytton's box or buy him a hair brush in London - a sturdy figure, dressed in a print dress, made after the pattern of one in a John picture, a thick mop of golden red hair, & a fat decided clever face, with staring bright blue eyes. The whole just misses, but decidedly misses what might be vulgarity. She seems to be an artist - seems, I say, for in our circle the current that way is enough to sweep people with no more art in them than Barbara in that direction. Still, I think Carrington cares for it genuinely, partly because of her way of looking at pictures.

(24) (24)Aldous Huxley, letter to Dorothy Brett (1st December 1918)

I saw Carrington not long ago, just after the armistice, and thought her enchanting; which indeed I always do whenever I see her, losing my heart completely as soon as she is no longer there. We went to see the show at the Omega, where there was what I thought an admirable Mark Gertler and a good Duncan Grant and a rather jolly Vanessa Bell. Carrington and I had a long argument on the subject of virginity: I may say it was she who provoked it by saying that she intended to remain a vestal for the rest of her life. All expostulations on my part were vain.

(25) Vanessa Curtis, Virginia Woolf's Women (2002)

There were, of course, a few very marked differences between Virginia and Carrington, one of the obvious ones being sexuality. Although both were at times attracted to members of the same sex, Carrington had been experimental with men and women both before and after she met Lytton. She was impulsive in affairs of the heart, but somehow succeeded in remaining friends with all her ex-lovers, a feat in no small way due to her total lack of maliciousness. She was not, unlike Virginia, faithful to her husband, nor he to her.

Another very clear difference between Carrington and Virginia was the reactions they had to social occasions. Virginia could be intimidating, sometimes intentionally, towards people she considered not to be on her own level, but Carrington was always easy company to be with and helpful almost to the point of subservience. Whilst Virginia enjoyed "holding court" in a circle of admirers, Carrington was more likely to be serving drinks to the group, or sitting quietly at the side. She put visitors at their ease and saw to their every need. She was not snobbish and was unconcerned with "class" and, in the absence of regular hired help, fetched and carried for Lytton devotedly, submissively, in a manner that Virginia would not have done for Leonard.

(26) Dora Carrington, letter to Lytton Strachey (28th July 1916)