The Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (original) (raw)

Abstract

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) affects over one-fourth of the global adult population and is the leading cause of liver disease worldwide. To address this, the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) has created clinical practice guidelines focused on MAFLD. The guidelines cover various aspects of the disease, such as its epidemiology, diagnosis, screening, assessment, and treatment. The guidelines aim to advance clinical practice, knowledge, and research on MAFLD, particularly in special groups. The guidelines are designed to advance clinical practice, to provide evidence-based recommendations to assist healthcare stakeholders in decision-making and to improve patient care and disease awareness. The guidelines take into account the burden of clinical management for the healthcare sector.

Introduction

The Asia–Pacific region is the largest global landmass with more than half of the world's population. Approximately half of the global burden of liver disease, mainly cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and liver-related mortality occurs in this region [1]. While there has been substantial improvements in the prevention and treatment of viral hepatitis, the prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is expected to increase in the future due to the rising burden of metabolic disorders and the consumption of energy dense, nutrient-poor foods, a sedentary lifestyle and reduced physical activity, both in high and low resources settings. A person living with MAFLD plays a vital role in their disease management, as the cornerstone of treatment is adherence to a healthy diet and being physically active. In this context, the development of effective strategies for managing MAFLD is paramount for reducing liver-related morbidity and mortality [2].

This document is the clinical practice guidelines of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) on MAFLD. These guidelines provide a broad framework for its management, encompassing aspects such as diagnosis, screening, treatment, surveillance, and detection of related co-morbid diseases. They are also designed to offer practical insights for healthcare professionals treating adult patients with MAFLD, with particular reference to special groups whenever necessary. The statements in this document adhere to the Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development, and Evaluation approach as outlined in Table 1. The ultimate goal is to enhance patient care and raise awareness about MAFLD, while also aiding stakeholders in making informed decisions based on evidence-based data.

Table 1 Evidence grade used for the APASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on MAFLD (adapted from the GRADE system) [3]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of MAFLD in the Asia–Pacific region ranges from 28 to 40%, largely reflecting that observed globally [4,5,6]. A recent meta-analysis provides more specific prevalence rates for different regions as follows: South Asia 34% (23 − 47%), South-East Asia 33% (19 − 51%), East Asia 30% (26 − 34%), and the Pacific region 28% (25 − 32%) [6]. The escalating prevalence of MAFLD in the aging population, currently impacting 120 million elderly people is anticipated to place a significant burden on the healthcare system in the near future [7]. the global steatohepatitis prevalence is 5.27%, with around 4.49% in the Asia Pacific. Additionally, the rising prevalence among young people is very concerning as the related health burden will be experienced across the lifespan.

At a country level, a study in China which included 75,570 participants undergoing regular health check-up visits, reported an overall MAFLD prevalence of 37%, with a higher rate in men (46%) than women (24%) [8]. The study also found that the prevalence increased with advancing age [8]. Another investigation from an urban Chinese population found an MAFLD prevalence of 26% as determined by ultrasonography [9]. Likewise, in a study of 6146 participants from New Delhi, India, approximately half of the study population was found to have MAFLD [10]. Another study which included 2782 participants showed that about one-third of the population of Bangladesh is affected by MAFLD [11]. A nationwide study from South Korea, which utilized ultrasonography and magnetic resonance elastography to investigate hepatic steatosis and fibrosis, reported MAFLD prevalence of 34% [12]. Of these patients, 3% exhibited advanced fibrosis. In a Japanese cohort of 2254 patients who underwent transient elastography during regular check-up visits, 35% were diagnosed with MAFLD. Of these, 9% had an increased risk for progressive liver disease as determined by the FibroScan-AST (FAST) score [13]. A separate investigation conducted in North Eastern Iran of 4242 patients reported an MAFLD prevalence of 23% [14]. A multicenter study from Turkey, representative of the general population, revealed a higher prevalence of MAFLD at 46% [15]. Notably, this cohort exhibited a more dysfunctional metabolic profile, with prevalence rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, and hypertension of 43%, 25%, 52%, 92%, and 32%, respectively. Another Turkish study which included 424 biopsy-proven MAFLD patients, found that 16% of patients had evidence of advanced fibrosis [16]. Similarly, MAFLD prevalence in Australia has increased from 33 to 39% between 2003 and 2018[17]. Another study from Australia of 722 participants from randomly selected households showed that the unadjusted prevalence was 47% [18].

Considering the collective data from investigations conducted in the Asia–Pacific, it is evident that patients with MAFLD from this region exhibit impaired metabolic profiles and an elevated risk for progressive liver disease, notwithstanding variations attributable to discrepancies in study methodologies and ethnic backgrounds. However, the epidemiological patterns in Asian countries largely align with global trends [6].

Definition and diagnosis of MAFLD

To address issues with the former nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) term, APASL was the first society to endorse the MAFLD definition [19]. MAFLD is a shift towards a diagnosis of inclusion based on the presence of metabolic dysfunction, the key driver of the disease [20, 21].

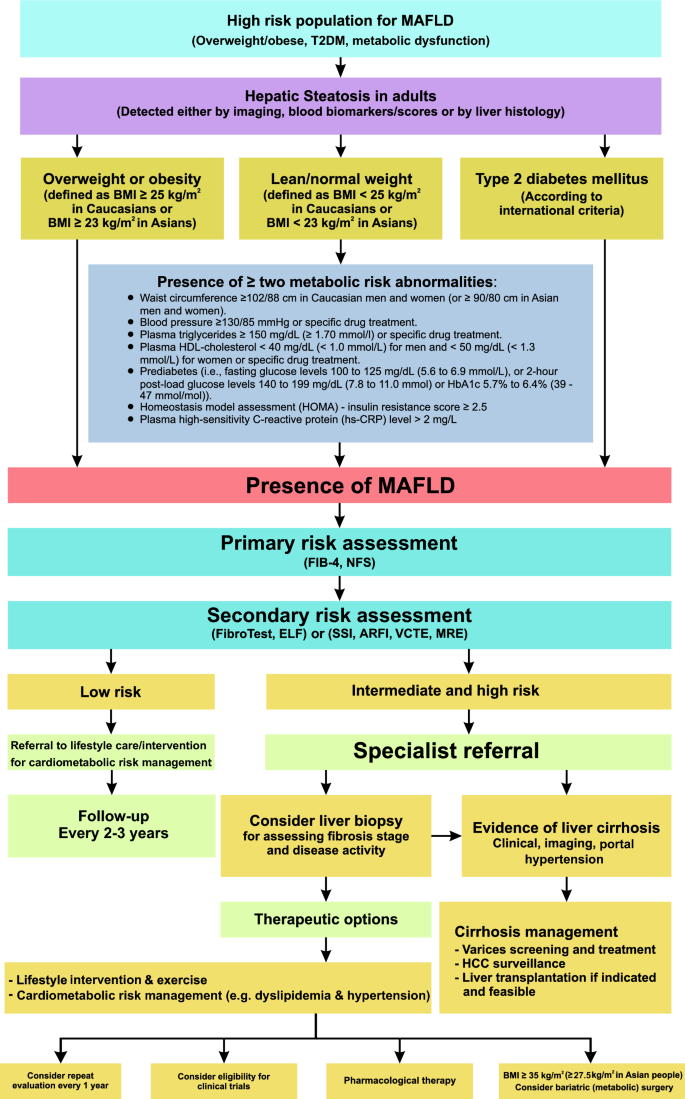

The diagnosis of MAFLD is based on the detection of liver steatosis (liver histology, non-invasive biomarkers or imaging) together with the presence of at least one of three criteria that include overweight or obesity, T2DM, or clinical evidence of metabolic dysfunction in lean subjects (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Recommended algorithm to diagnose, evaluate, and monitor disease severity in suspected patients with MAFLD and management approach for confirmed cases. HDL-cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; FIB-4, Fibrosis-4 index; NFS, MAFLD fibrosis score; ELF, enhanced liver fibrosis; SSI, supersonic shear imaging; ARFI, acoustic radiation force impulse; VCTE, vibration-controlled transient elastography; MRE, magnetic resonance elastography

Recent data confirm the superior utility of MAFLD for identifying patients at high risk for hepatic and extra-hepatic complications [22], as well as those who would benefit from genetic testing, including patients with concomitant other liver diseases. As MAFLD segregates patients into three homogenous groups (diabetic, overweight/obese and lean with evidence of metabolic dysfunction) with different baseline characteristics, clinical trajectories and outcomes, it represents an advance for the field in how we should think of liver disease related to systemic metabolic dysregulation [23]. Additionally, MAFLD can guide efforts towards a more inclusive, equitable, and patient-centered approach.

Risk factors for MAFLD

The pathogenesis of MAFLD is complex and likely influenced by the dynamic interactions between various risk factors such as central obesity, T2DM, dyslipidemia, and genetic risk factors.[24] These risk factors can be divided into modifiable and non-modifiable categories (Table 2).

Table 2 Risk factors for MAFLD

The presence of obesity is associated with MAFLD, and the prevalence of MAFLD increases as body mass index (BMI) increases [9, 25, 26]. In addition to BMI, growing evidence suggests that central obesity plays a major role in the development and progression of MAFLD [27]. Central obesity should be considered when assessing risk factors in Asian patients with MAFLD [28] as they are more likely to have high central fat deposition despite a lower BMI [24]. It was reported that T2DM is a major risk factor for the development and progression of MAFLD [26], and the global prevalence of MAFLD among patients with T2DM is approximately 65% [29]. Dyslipidemia also affects the development of MAFLD [26].

While overweight/obesity is associated with the onset and progression of MAFLD, weight gain without reaching overweight status plays a crucial role in metabolic disease pathogenesis and in MAFLD [30]. According to a systematic review of 93 studies from 24 countries and areas around the world, among individuals with MAFLD, 19% were classified as lean, while 41% were classified as non-obese with no differences in histological severity between lean and obese patients. Remarkably, about one-third of patients with normal BMI and MAFLD meet the criteria for metabolic syndrome [31].

A low level of physical activity is reported to increase the risk of MAFLD [32, 33]. Similarly, sarcopenia and MAFLD share many common pathophysiologic mechanisms, thus they are associated in a bidirectional manner [34, 35]. The risk of MAFLD increases in the presence of sarcopenia, and sarcopenia is associated with significant fibrosis [36,37,38]. Recently, it has been suggested that myosteatosis and muscle quality can play an important role in the progression of early-stage MAFLD [39, 40], even among the non-obese population [41]. A high-caloric or high-fructose diet is another risk factor for MAFLD, regardless of obesity [42, 43]. Recent studies indicate that gut microbiota and its metabolites play a critical role in the onset of MAFLD [44, 45]. In addition, obstructive sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, polycystic ovary syndrome, and hypogonadism are associated with the development of MAFLD [46,47,48,49].

As for non-modifiable risk factors, a study of 73,566 ethnic Chinese reported that male sex and older age were risk factors for MAFLD [25]. Genetic factors contribute to the development and progression of MAFLD. For example, gene variants such as PNPLA3, TM6SF2 and MBOAT7 are associated with the full spectrum of MAFLD [50,51,52]. Growing evidence also suggests that epigenetic factors are implicated in MAFLD pathogenesis. Likewise, the length of telomeres in liver cells shortens as fibrosis stage advances in patients with MAFLD [53, 54].

Natural history of MAFLD

The progression of MAFLD is complex and not entirely clear due to it being part of a multisystem disorder with hepatic and extrahepatic complications. In general, the natural history of MAFLD is slowly progressive, starting with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver (Simple steatosis) characterized by lipid accumulation in liver cells. It is estimated that within 7 years, about 44% of patients, especially those with genetic predisposition, will develop lipotoxicity leading to steatohepatitis-(Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis—MASH) [55]. However, observational data also indicate that MASH patients may regress to steatosis spontaneously (around 7% within 7 years) although it is uncertain if this is true regression, is due to variability in liver biopsy, or due to improvements in systemic metabolic dysregulation. Patients with pure fatty infiltration without inflammation or fibrosis have a relatively low risk of disease progression [56].

At the MASH stage, characterized by the activation of inflammatory cascades in various cell types (including Kupffer cells and stellate cells), there is excessive intercellular matrix deposition. This leads to early-stage liver fibrosis occurring in about a quarter of patients over approximately 3.4 years [57]. The average progression rate by an additional one fibrosis stage in patients with steatosis and steatohepatitis is 14.3 years and 7.1 years, respectively [[58](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR58 "Singh S, Allen AM, Wang Z, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Loomba R. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.014

")\]. Approximately 16% of patients with low-grade fibrosis (< F3) will progress to advanced fibrosis \[[6](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR6 "Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Paik JM, Henry A, Van Dongen C, Henry L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology. 2023;77(4):1335–1347")\]. However, around 13.2% of patients may experience regression, reducing by one fibrosis stage \[[59](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR59 "Nasr P, Ignatova S, Kechagias S, Ekstedt M. Natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective follow-up study with serial biopsies. Hepatol Commun. 2018;2(2):199–210")\].Approximately 2.6% of people with MAFLD-related cirrhosis will develop HCC annually [60]. A systematic review showed that among 470,404 MAFLD patients, the incidence rate of HCC was 0.03/100 person-years, and 3.78/100 person-years in the pre-cirrhotic and cirrhotic stages, respectively [61]. Additionally, data show that 35–47% of HCC cases among patients with MAFLD may develop in the absence of cirrhosis [62, 63].

Assessment for MAFLD

MAFLD affects a large proportion of the general population, but only a small yet significant proportion develop advanced liver fibrosis (≥ F3 stage) [64]. Patients with advanced liver fibrosis are at increased risk of liver-related events and mortality [65, 66]. However, patients with MAFLD, even in the presence of advanced liver fibrosis, are often asymptomatic and may present for the first time with hepatic decompensation, thereby missing the opportunity for preventive intervention [67]. Widespread screening for MAFLD in the general population followed by treatment is currently not justified until further evidence emerges. Therefore, active case findings among high-risk groups are more appropriate.

Ultrasonography, the most common test for the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis can be utilised for screening. There is a high prevalence of MAFLD among patients with T2DM who are at increased risk of steatohepatitis and for advanced liver fibrosis [68, 69]. Furthermore, T2DM has been identified as an independent risk factor for hepatic decompensation and HCC among patients with MAFLD [70]. Therefore, patients with metabolic comorbidities generally and those with T2DM particularly, represent an important target population for identification of MAFLD and advanced liver fibrosis. In this context, assessment of the liver can be included as part of the assessment for target organ damage in patients with T2DM. This can be achieved with simple blood tests (i.e., serum ALT and AST levels and platelet count) and blood-based biomarkers and scores.

Recommended pathway for referral from primary care to tertiary hospital

Clear referral pathways aid in risk-stratifying patients who are most in need of specialist assessment, from those with mild disease who can be managed in primary care.

Elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels should prompt evaluation for the cause of liver injury. However, normal serum ALT and AST levels do not exclude underlying liver disease. Patients with MAFLD and steatohepatitis and/or advanced liver fibrosis or cirrhosis can have normal serum ALT and AST levels [71,72,73]. Current risk-stratification algorithms use non-invasive tests (NIT’s) in a sequential fashion to identify patients with advanced liver fibrosis (F3-4) who are present in 2-5% of the primary care population [12, 74, [75](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR75 "Mahady SE, Macaskill P, Craig JC, Wong GL, Chu WC, Chan HL, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive fibrosis scores in a population of individuals with a low prevalence of fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.031

")\]. Recent studies have shown that significant liver fibrosis (F2-4) is associated with an increased risk of liver-related death compared to no fibrosis. This population is currently the target of ongoing clinical trials.Currently, there is no standardised cutoff established for diagnostic accuracy for advanced fibrosis; the recommended cutoffs to rule in advanced hepatic fibrosis using NITs are shown in Table 3. Fibrosis-4 Index (FIB-4) is recommended as the first-line test for fibrosis assessment in general practice. Although it has modest accuracy with a meta-analysis of 37 studies (_n_=5735) finding a summary area under the curve (AUC) of 0.76, its appeal relates to its availability and low-cost.[76] A cut-off of 1.3 has a sensitivity of 74% (95% CI 72–76%) and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 95–97% for excluding advanced fibrosis, highlighting its role in identifying patients who can remain in primary care. These patients should be monitored with a repeat FIB-4 in 2-3 years; patients with an FIB-4 persistently <1.3 are at very low risk of developing cirrhosis and HCC.[77] A cut-off of 2.67 is 94% (95% CI 93–94%) specific for advanced fibrosis and patients above this threshold should be referred for specialist assessment.[76] It is important to recognize that the positive predictive value (PPV) of a FIB-4 >2.67 in primary care is only 24–40%, highlighting the need for other investigations to confirm a diagnosis of advanced fibrosis. Approximately 30% of patients will have an indeterminate FIB-4 between 1.3 and 2.67 and will benefit from further testing.[78, 79]. There are limitations of FIB-4 in screening for advanced liver fibrosis, particularly in individuals with diabetes. Additionally, the FIB-4 score is affected by age, making it less reliable in patients under 35 or over 65 years old. Although using age-specific thresholds raising the cut-off for participants ≥65 years old from 1.3 to 2.0 (while high-risk thresholds remain the same) was suggested, it might lead to an undesirable reduction in sensitivity (from 84 to 36%). Nevertheless, considering the widespread occurrence of MAFLD in the general population, it is reasonable to use a cutoff of <1.3, along with other clinical measures, to rule out most individuals with advanced fibrosis. The potential coexistence of MAFLD with other liver diseases, including viral hepatitis and alcohol-related liver disease, should be considered, particularly in patients with persistently elevated liver enzymes or higher FIB-4 levels.

Table 3 Recommended cutoff to rule in advanced hepatic fibrosis

Second-line testing of patients who fall within indeterminate FIB-4 ranges can be performed using elastography or direct serum tests according to local availability and cost. Vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) or Fibroscan® accurately excludes advanced fibrosis, with a large multicentre study from Asia demonstrating a liver stiffness measurement (LSM) threshold of 8 kPa being 96% sensitive with an NPV of 99.7% [80]. XL probes are available to determine LSM in overweight or obese patients. Subjects with an indeterminate FIB-4 and a subsequent LSM of < 8 kPa can be managed in primary care and have a rate of risk of future liver-related events that is similar to patients with a FIB-4 < 1.3 [81]. Two-dimensional shear wave elastography (2D-SWE) using the Aixplorer® platform provides similar accuracy to VCTE when used in a sequential fashion in MAFLD patients with an indeterminate FIB-4 result [82]. In a study of 577 patients, a threshold of 8 kPa using 2D-SWE provided a false negative rate of 8% for the presence of advanced fibrosis, however, the rate of invalid scans was relatively high (23%) [82]. The most accurate non-invasive method to quantify liver fibrosis is MR elastography [83], but this has limited accessibility and requires additional technical hardware beyond a standard MR scan and is not recommended as a first-line approach for risk stratification in a patient with MAFLD [84].

A strategy of using the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF) test (which is a serum test that measures 3 molecules that are directly involved in liver matrix metabolism: (1) hyaluronic acid (HA), (2) procollagen III amino-terminal peptide (PIIINP), and (3) tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1)) for those with an indeterminate FIB-4, has a low false negative rate (8%) for predicting an elevated LSM (>8 kPa) when using an ELF cut-off of 9.8.[78] This strategy is also associated with a reduced referral rate of 14% [78]. A study based in primary care in the UK confirmed the effectiveness of the sequential use of FIB-4 followed by ELF, demonstrating a four-fold increase in the diagnosis of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis and an 81% reduction in unnecessary referrals [85]. Other direct serum tests include Hepascore (a serum fibrosis model that uses bilirubin, α2-macroglobulin, hyaluronic acid, and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase) and Fibrometer (which includes indirect blood markers (AST, urea, platelets, prothrombin time) and direct (hyaluronate, alpha2-macroglobulin)) tests which have similar accuracy to VCTE for predicting liver-related events in patients with MAFLD [86]. In a study of 938 MAFLD patients, sequential use of FIB-4 followed by Hepascore or Fibrometer had diagnostic accuracies of 80–83% and 100% specificity for both approaches, but only 50–59% sensitivity for the diagnosis of advanced fibrosis [87]. A PRO‐C3‐based score (ADAPT) accurately identifies patients with MAFLD and advanced fibrosis [88, 89].

Implementing referral pathways in primary care needs to be combined with educational strategies to increase disease awareness and understanding of the prevalence, natural history and assessment of patients with MAFLD.[90] Computer decision support systems consisting of automatic liver fibrosis risk calculators and electronic reminders can aid in increasing referrals.[91] New combinations of novel NIT’s are likely to be more accurate and can result in fewer inappropriate referrals, however, they will need to be of low cost and easily available to enable widespread implementation. With effective pharmacotherapy likely available in the near future, referral pathways will need to be altered to identify ‘At Risk MASH’ (MASH and significant fibrosis, F2/F3 stage), the patient group targeted in current clinical trials.

Assessment of disease severity

Hepatic steatosis is traditionally detected by conventional ultrasonography, although this is limited by its non-quantitative nature, inter-operator variability and lower sensitivity for mild steatosis [92]. Controlled attenuation parameter (CAP), performed via VCTE, quantifies ultrasound attenuation radiofrequency which correlates with the histological degree of steatosis. Based on a meta-analysis of biopsy-based studies, optimal cut-offs of 248, 268 and 280 dB/m were reported for histological mild, moderate and severe steatosis respectively, achieving area under the curves of 0.82–0.89 [93]. While CAP measurements are extensively used due to their point-of-care applicability and easy reproducibility, variabilities in quantification still exist especially in patients with obesity and other metabolic risk factors and the association between CAP measurements and clinical outcomes are not well established. To optimize diagnostic performance, the obesity-specific XL probe has been developed [94], while an interquartile range of 40 dB/m is employed as a criterion for the original M probe [95]. Magnetic resonance (MR)-proton density fat fraction (PDFF) is the most accurate non-invasive method for steatosis quantification but has limited accessibility [96]. Additionally, blood biomarkers and scores, such as the fatty liver index (FLI), are considered suitable for epidemiological studies to detect hepatic steatosis in adults.

Histological steatohepatitis, characterized by hepatocyte injury and ballooning, is associated with an increased rate of disease progression and liver-related complications [[58](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR58 "Singh S, Allen AM, Wang Z, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Loomba R. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.014

")\]. Serum ALT alone poorly predicts the presence of steatohepatitis \[[97](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR97 "Verma S, Jensen D, Hart J, Mohanty SR. Predictive value of ALT levels for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and advanced fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Liver Int. 2013;33(9):1398–1405")\]. The FAST score, which combines LSM and CAP from VCTE and serum AST, was found in a meta-analysis to achieve a sensitivity and specificity of 89% for identifying patients with steatohepatitis, increased inflammatory activity and significant fibrosis \[[98](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR98 "Ravaioli F, Dajti E, Mantovani A, Newsome PN, Targher G, Colecchia A. Diagnostic accuracy of FibroScan-AST (FAST) score for the non-invasive identification of patients with fibrotic non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2023;72(7):1399–1409")\]. No other serum or ultrasound-based single biomarker or multimarker score was able to accurately predict steatohepatitis \[[99](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR99 "Vali Y, Lee J, Boursier J, Petta S, Wonders K, Tiniakos D, et al. Biomarkers for staging fibrosis and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (the LITMUS project): a comparative diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(8):714–725"), [100](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR100 "Wong VW-S, Anstee QM, Nitze LM, Geerts A, George J, Nolasco V, et al. FibroScan-aspartate aminotransferase (FAST) score for monitoring histological improvement in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis activity during semaglutide treatment: post-hoc analysis of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;66:102310")\]. The combined assessment of a ≥ 30% decline in MRI-PDFF and a ≥ 17 U/L decrease in ALT are associated with an increased probability of steatohepatitis resolution (adjusted odds ratio 7.32), although this finding has yet to be validated in real-world practice \[[101](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR101 "Huang DQ, Sharpton SR, Amangurbanova M, Tamaki N, Sirlin CB, Loomba R. Clinical utility of combined MRI-PDFF and ALT response in predicting histologic response in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(10):2682-2685.e2684")\].Non-invasive tests are predictive of clinical outcomes. The abovementioned FIB-4 and LSM combination are independent predictors of liver-related events [81, 102], and on their own had a similar predictability as histologically-assessed liver fibrosis [65]. Non-invasive tests can hence be considered as alternatives to liver biopsy for disease prognostication.

Who should undergo liver biopsy?

Liver biopsy is the best method to evaluate hepatic architectural distortion and the complex relationships between fibrosis, inflammation, and cellular injury. While liver biopsy is not routinely recommended for the evaluation of MAFLD patients, it remains required for MAFLD evaluation in some circumstances. This includes patients with atypical presentations where histology can be an aid to diagnosis, especially in individuals with equivocal or discordant non-invasive test results. Patients enrolled in late phase clinical trials require liver biopsy as regulatory authorities require the resolution of steatohepatitis and/or improvement in fibrosis as endpoints. These endpoints can only be evaluated by liver biopsy [103]. Lastly, liver biopsy results are used as reference standards to validate non-invasive biomarkers.

There are limitations to liver biopsy including sampling error, interobserver variability, and cost, as well as some rare complications [104]. It is worth noting that staging and classification systems are heavily reliant on the assessment of fibrosis and inflammation. However, liver tissue sampling by a biopsy is one snapshot of a miniscule portion of the liver in an otherwise long-term, fluctuating chronic liver disease that spans decades. Liver biopsy does not consider changes in the inflammatory state, i.e. chronic or sporadic relapse, as is found in many chronic liver diseases [105] and this may also be the case with MAFLD.

Pathological recommendations: standardisation of assessment and reporting

If percutaneous liver biopsy is performed, a 14 or 16-gauge needle is recommended since there is no data to suggest a higher complication rate as compared to the use of a smaller needle [106]. Suction biopsy should be avoided since it can cause fragmentation of cirrhotic liver tissue. An optimum biopsy should be 1.5–2.5 cm in length and when possible, the right lobe of the liver is preferred since the left lobe is thinner with more fibrous septa closer to the liver capsule. Once obtained, fresh tissue should be immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin immediately and left for fixation for at least 6 h, but less than 72 h.

The minimum required staining includes hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; for detection of morphological features including lobular inflammation, ballooning, and steatosis) and Masson trichrome (for detection of fibrosis); alternatively, Picrosirius red or Mallory’s stain can be used for detection of fibrosis.

Pathological reporting systems

The common system for evaluation of fibrosis in MAFLD is the Brunt score [107]. The NAFLD activity score (NAS) is composed of the unweighted sum of semiquantitative scores for steatosis, lobular inflammation and hepatocellular ballooning. Although a high NAS grade closely links to disease progression, grading should be used in conjunction with the NASH CRN fibrosis staging system.

The fatty liver inhibition of progression (FLIP) algorithm or SAF (steatosis, activity, and fibrosis) scoring system also provides a detailed histological assessment (Table 4). [108] [109]

Table 4 Comparisons of grading and staging of histological lesions in MAFLD

Overall, the NAS and SAF score share many similarities, but they are not interchangeable, and both the NASH CRN and SAF score show improved interobserver variability and has been validated clinically. Integration of both might be of added value. However, a recent study has shown that current reporting systems remain suboptimal for end-point determination in clinical trials [110, 111]. Digital image analysis and artificial intelligence (AI) show strong correlations with fibrosis but their performance is lower when assessing inflammation. More data will be generated in this field over the coming years.

Extrahepatic manifestations of MAFLD

MAFLD is a multi-system disease [112,113,114]. Existing evidence has confirmed that MAFLD is associated with dysfunction in multiple organ systems, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), T2DM and extrahepatic cancers [115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124]. In addition, MAFLD is associated with sarcopenia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, SARS-Co-V2 infection and related morbidity, ischemic stroke and cognitive dysfunction [115, 125,126,127,128,129]. In one study, compared to non-MAFLD, MAFLD was associated with increased risk of 10 of the 24 examined cancers, including those of the uterus, gallbladder, liver, kidney, thyroid, oesophagus, pancreas, bladder, breast, colorectum and anal canal [130].

Many studies have shown that MAFLD is an independent risk factor for CKD, and its severity is associated with a ~ 1.3-fold higher risk of having CKD [115, 116, 131,132,133]. Similar to CKD, CVD is an important outcome event in the MAFLD population. Previous studies indicate that patients with MAFLD have 1.5 times the risk of fatal and non-fatal CVD events compared to patients without MAFLD. This result was also confirmed in a recent meta-analysis of seven cohort studies [120, 124, 134, 135].

The molecular mechanisms for these multi-system effects are complex. Proposed mechanisms include genetic predisposition, shared environmental risk factors and interacting metabolic diseases, the gut-liver axis, bile acids, endotoxins and adipokines in the setting of a dysmetabolic milieu. In concert to varying degrees, these factors promote MAFLD progression [136,137,138,139,140].

Management

Setting up integrated, multi-disciplinary care for MAFLD patients

The complex and bidirectional relationships between MAFLD and other conditions associated with metabolic dysfunction suggests that the implementation of integrated, multidisciplinary models for the delivery of standardized care can strike the right balance between cost-effectiveness, improved clinical outcomes, and patient satisfaction [24, 141, 142].

Implementing multidisciplinary models of care, comprising a hepatologist, a cardiologist, a diabetologist, a nephrologist and a medically supervised diet and exercise program, has been reported to be effective in improving liver and cardiometabolic-related health parameters, liver function, and weight loss [143,144,145]. Another study showed that a model tailored for MAFLD patients “ICHANGE”, coordinated by hepatologists but engaging other relevant subspecialties not only facilitated enhanced quality of care, patient compliance with treatment, and better alignment between healthcare providers and patients, but also added value in terms of cost-time efficacy and fewer hospital visits [146].

However, there are challenges in sustainably implementing care models, particularly with the diverse resourcing and health settings reflected in APASL countries. These include travelling long distances for a consultation to tertiary centres, developing one-stop coordinated consultations with various subspecialists, and having well-coordinated referrals without longer wait times. Further, training and collaboration between primary and secondary care and upskilling general practitioners for timely triage, screening, and referrals, as well as the need for constant capacity building to cater to the increasing burden of patients with increasing awareness is another issue [142]. Additionally, the high prevalence of the disease poses a challenge to the widespread application of these programs, requiring prioritization of those at greatest risk (i.e., MASH with significant fibrosis). Leveraging existing multidisciplinary care models, including in low-resource settings such as at diabetes, CKD, TB and HIV clinics, for managing MAFLD is a possible approach. Additionally, nurses and potentially nurse-led clinics play a critical role in providing critical primary care level services, which can be expanded to enhance care coverage.

Hence, while the adoption of integrated, multidisciplinary care models can streamline the delivery of standardized care to patients, the structure of the models and the composition of practitioners involved in organizing the care may vary depending on the context and healthcare system, particularly in resource-constrained settings. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the target population, settings, and subspecialties involved in multidisciplinary care, as well as the dynamics of integrating and coordinating services between primary, secondary, and tertiary care. Optimally done, this ensures an effective, cost-efficient, time-efficient, patient-centred approach, while also promoting health system sustainability [147, 148].

Lifestyle management recommendations

Lifestyle interventions, including diet and physical activity, are the main treatments for MAFLD. Overweight or obese MAFLD patients should be advised to lose 5–10% of body weight. A weight reduction of > 5% reduces liver steatosis, 7–10% leads to MASH resolution, and > 10% improves liver fibrosis [149]. Frequent self-weighing (at least weekly), reduced-calorie diets, and increased physical activity are associated with better long-term weight management.

Practical recommendations for dietary management

The dietary plan should be individualized while considering cultural background and social context. Dietary calorie restriction results in weight reduction and improvement of serum liver enzymes, hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis [149,150,151,152]. MAFLD patients should be advised to consume 1200–1800 kcal a day or 500–750 kcal less daily for weight loss.

A diet comprising added sugar (fructose, high-fructose corn syrup, and sucrose), such as sugar-sweetened beverages, excess saturated fat (for instance, palm oil), as well as ultra-processed foods (UPF), should be avoided [151, 153]. UPF is a potential risk factor for MAFLD, obesity, and metabolic syndrome [154].

The Mediterranean-type dietary pattern is the most evidence-based for MAFLD [155,156,157,158,159]. This diet is characterized by a reduced intake of refined carbohydrates, sugars, and processed foods while increasing consumption of monounsaturated and omega-3 fatty acids. A Mediterranean-style diet is associated with a reduced risk of T2DM, CVD, liver fat, and fibrosis in patients with MAFLD [160,161,162]. In addition, this dietary pattern is associated with a reduced risk for HCC [163]. A diet style tailored to local eating habits may improve adherence. However, this needs further validation in future studies.

Intermittent fasting and time-restricted feeding have recently gained popularity. Intermittent fasting involves alternating feeding days with fasting days, while time-restricted feeding involves restricting eating to an 8 h or less period each day within a 24 h cycle. Both dietary approaches lead to significant weight reduction and metabolic improvements in overweight and obese subjects. Evidence regarding the efficacy of these dietary strategies on MAFLD is limited. However, a meta-analysis suggested, with moderate- to high-quality evidence, that intermittent fasting and time-restricted feeding improve hepatic inflammation, steatosis, and stiffness, as well as promoting weight loss in adults with MAFLD [164].

The ketogenic diet is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate (less than 20–50 g/day) dietary pattern. Ketogenic diets reduce body weight and liver steatosis but not fibrosis as suggested by previous small randomized-controlled trials [165, 166]. At this time, ketogenic diets should only be followed after recommendation and support from a health care professional or dietitian- and is likely only suitable and sustainable in the short term. Further studies are required to assess the effects of ketogenic diets on liver-related outcomes and the sustainability of this diet approach in MAFLD.

Coffee consumption (three or more cups per day), regardless of caffeine content, is considered to be beneficial. Epidemiological and meta-analyses have demonstrated that coffee consumption is associated with a lower risk of MAFLD and decreased liver fibrosis in patients with MAFLD [167, 168]. However, a caveat is that all these studies are non-randomised, epidemiological reports that compare coffee drinkers to non-coffee drinkers and are therefore potentially subject to unmeasured confounding.

Practical recommendations for exercise management

Physical activity is an integral component of the multidisciplinary care of patients with MAFLD and should be evaluated (e.g., via the simple Physical Activity Vital Sign [169]) and prioritised [170, 171]. While a combination of diet and structured exercise training has synergistic benefits for MAFLD [172, 173], regular exercise alone elicits broad hepatic and cardiometabolic benefits irrespective of weight loss and can improve health-related quality of life [170]. Regular exercise improves insulin sensitivity, reduces inflammation, and alters substrate metabolism in the muscle, liver and adipose tissue, which affects hepatic free fatty acid flux [174,175,176,177,178].

A total of 150–240 min per week of moderate-to-vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise is recommended for reducing hepatic steatosis by 2–4% (absolute reduction), equating to a clinically meaningful ~ 30% relative reduction in liver fat [33, 133, 179]; however as little as 135 min per week may be effective [170]. Brisk walking, cycling, and jogging are modalities commonly reported to elicit a benefit. This volume of aerobic exercise is likely to reduce visceral adiposity, increase cardiorespiratory fitness, reduce LDL-cholesterol and improve vascular health in people with MAFLD, although large-scale randomised controlled trials with long-term follow-up are lacking [170].

While intensity-dependent benefits are not apparent for hepatic steatosis [180,181,182], emerging evidence demonstrates that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) involving one or more bursts of high-intensity exercise interspersed with lower-intensity recovery periods is equally effective under the supervision of an exercise professional [181] [183].

There are limited data to inform the efficacy of exercise for the histological features of MAFLD given the challenges associated with repeated liver biopsy. Pilot data has indicated a one-stage regression in liver fibrosis and hepatocyte ballooning in 58% and 67% of MAFLD participants, respectively, with 12 weeks of moderate-vigorous aerobic exercise on 3–5 days per week [184]. Histological improvements were more strongly associated with improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness than weight loss [184]. Moreover, moderate-intensity aerobic exercise led to improvements in serum- and imaging-based surrogates of liver fibro-inflammation and histological activity [185, 186].

The benefits of resistance training for MAFLD are less clear with equivocal findings for efficacy on hepatic steatosis, likely due to the heterogeneity of training methodologies [170]. However, given the interrelationship between sarcopenia and MAFLD [187], and the profound benefits of resistance training on lean mass, bone mass, blood pressure and glycaemic control [[188](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR188 "El-Kotob R, Ponzano M, Chaput JP, Janssen I, Kho ME, Poitras VJ, et al. Resistance training and health in adults: an overview of systematic reviews. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2020-0245

"), [189](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR189 "Abou Sawan S, Nunes EA, Lim C, McKendry J, Phillips SM. The health benefits of resistance exercise: beyond hypertrophy and big weights. Exercise Sports Movement. 2023;1(1):e00001")\], resistance exercise is likely beneficial for many individuals with MAFLD and should be recommended in addition to aerobic exercise. A meta-analysis showed that resistance exercise improves MAFLD with less energy consumption \[[190](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR190 "Hashida R, Kawaguchi T, Bekki M, Omoto M, Matsuse H, Nago T, et al. Aerobic vs resistance exercise in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2017;66(1):142–152")\]. While data is lacking, resistance training on 2–3 days per week should be prioritised in MAFLD patients with co-existing sarcopenia, T2DM, low functional capacity and/or those reducing body weight substantially via pharmacological approaches to minimise losses of lean and bone mass. There are no evidence-supported recommendations regarding the intensity, frequency, number of sets and repetitions of resistance exercise required for hepatic benefit \[[170](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR170 "Keating SE, Sabag A, Hallsworth K, Hickman IJ, Macdonald GA, Stine JG, et al. Exercise in the management of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) in adults: a position statement from exercise and sport science Australia. Sports Med. 2023;53(12):2347–2371")\].It is prudent to acknowledge that most MAFLD patients will have low initial cardiorespiratory fitness and varying degrees of cardiovascular dysfunction and therefore a stepped approach to achieving exercise recommendations is required. Referral to an appropriately qualified exercise professional is recommended to provide tailored prescriptions, cognisant of individual capability and preferences, which address common barriers to exercise in MAFLD (e.g., time, access to equipment/facilities, musculoskeletal limitations, low exercise-related self-efficacy) [191,192,193].

Metabolic surgery and endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies for MAFLD

Metabolic surgery and Endoscopic Bariatric and Metabolic Therapies (EBMT) are highly effective in the management of morbid obesity. While they have not been tested specifically for the treatment of MAFLD, multiple studies have demonstrated efficacy in improving the features of MAFLD [194,195,196].

Metabolic surgery, which includes sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, adjustable gastric banding or biliopancreatic diversion, is an accepted standard of care for morbid obesity. These therapies are effective in inducing sustained weight loss by up to 30%, and also improve metabolic dysfunction and adverse clinical outcomes from T2DM, and cardiovascular disease and reduce overall mortality [197]. Within the Asian context, the ethnicity-adjusted BMI risk thresholds for obesity should be used and should also take into account metabolic comorbidity risk [198]. In the Asian population, a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 suggests clinical obesity, and individuals with a BMI ≥ 27.5 kg/m2 should be considered for metabolic and bariatric surgery.

Specific to MAFLD, several meta-analyses have shown concordant observations that bariatric surgery results in the resolution of steatosis, ballooning degeneration and inflammation in up to 50% of patients; about 24% demonstrate improvement in liver fibrosis [196, 199, 200]. Interestingly, pooled analysis shows that Asian MAFLD patients, respond better to metabolic surgery in terms of improvement of liver enzymes, steatosis and fibrosis compared to non-Asian patients [196]. Randomized controlled studies with bariatric surgery have demonstrated up to 3.6-fold higher efficacy in the resolution of biopsy-proven steatohepatitis without worsening of liver fibrosis compared to standard medical therapy [201]; these benefits can be sustained for up to 5 years [202]. Large cohort studies have also shown a reduction in the 10-year cumulative incidence of major adverse liver outcomes from 9.6 to 2.3% compared to a matched non-surgical cohort [203].

While the efficacy of bariatric surgery for MAFLD is acknowledged, it is worth noting that the evidence for patients with advanced fibrosis undergoing bariatric surgery is still low. Liver fibrosis can progress in a subset of these patients and monitoring is recommended [200]. A further note of caution is that while bariatric surgery is relatively safe in compensated cirrhosis, adverse events and mortality can be as high as 18% in decompensated cirrhosis, highlighting the need to screen for portal hypertension [204, 205].

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies are a rapidly evolving field, where non-surgical endoscopic procedures are used to replicate the outcomes of bariatric surgery. Some of the techniques include intragastric balloons, endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty; primary obesity surgery endoluminal (POSE) plication device, aspiration therapy, and transpyloric shuttle. These broad-ranging techniques were analysed in a meta-analysis of 18 high-quality studies (including 5 from Asia) and showed promising efficacy for weight loss, improvement in liver enzymes, steatosis, steatohepatitis and fibrosis, albeit not all used gold standard liver biopsies [194, 195]. While EBMT theoretically has lower morbidity compared to bariatric surgery, the relative sustained efficacy for MAFLD needs to be determined and the risk of potential adverse events such as ulcer bleeding, leaks and peritonitis requires further study.

Pharmacological treatment

Current potential therapies

Recent studies have focused on the potential for repurposing approved agents for alleviating steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis in MAFLD. Among these, evidence on the efficacy of anti-diabetic medications is rapidly accumulating.

The beneficial effects of pioglitazone on hepatic histology have been reported in patients with steatohepatitis, with and without T2DM [206, 207]. A double-blind randomized trial showed that a 24-weeks pioglitazone treatment was well-tolerated and effective in improving liver histology and reducing liver steatosis in Asian patients with MASH [208]. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) have been widely used for the treatment of T2DM and cardiovascular disease, with some evidence of benefit for MAFLD [209, 210]. The beneficial effects of SGLT2i’s such as dapagliflozin, empagliflozin and canagliflozin on liver fat content has been reported as well as improvement of serum transaminases and non-invasive scores for fibrosis [209,210,211,212,213,214]. There remains a paucity of data on the efficacy of these agents for the improvement of liver inflammation and fibrosis. Recent reports demonstrate that licogliflozin led to improvement in surrogate markers of liver fibrosis assessed by the ELF score and serum PIIINP levels [215]. Similarly, empagliflozin led to significant reductions in LSM, but not other non-invasive scores of fibrosis [216]. These reports lack histological evidence for improvements in steatohepatitis or fibrosis. Trials of ipragliflozin and tofogliflozin included paired liver biopsy to demonstrate histological benefits in MAFLD patients [216, 217], nevertheless, the relatively small sample sizes mean that the level of evidence is not strong. In addition, most of these studies were carried out among T2DM patients with MAFLD, with few investigating SGLT2 inhibitors in non-diabetic patients with MAFLD [218]. Metformin does not improve hepatic histology in patients with MAFLD [219,220,221,222]. However, metformin improves insulin resistance [219, 221, 222] and reduces the risk of HCC in patients with MAFLD, although available studies have not been prospective or randomized [223, 224]. A non-randomized interventional cohort study reported that among oral antidiabetic drugs for patients with T2DM accompanied by MAFLD, SGLT2 inhibitors are preferable considering the improvement of MAFLD and the reduction of incident adverse liver-related outcomes when compared to thiazolidinediones, DPP4 inhibitors, and sulfonylureas. This retrospective study was conducted using South Korea’s National Health Insurance Database. It followed 80,178 patients over 219,941 person-years follow-up and demonstrated improvement of MAFLD in 4,102 cases. SGLT2 inhibitors had a higher likelihood of improving MAFLD and significantly lower rates of adverse liver-related outcomes such as liver-related hospitalizations, death, liver transplants, and HCC compared to other oral antidiabetic drugs [225].

Vitamin E has been reported to be effective in improving hepatic histology in patients with steatohepatitis [226,227,228,229]. However, several studies have failed to demonstrate its beneficial effects and level 1 evidence is thus lacking [216, 221, 230, 231]. Recently, a propensity score matching analysis demonstrated that vitamin E decreases the risk of death or transplant and hepatic decompensation in MASH patients with bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis [217]. The development of prostate cancer and hemorrhagic stroke is a possible concern with vitamin E [218].

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) might have beneficial effects for MAFLD [232], with some reports from observational studies showing their use to be associated with milder liver fibrosis [233] and a reduced risk of liver-related events. However, the benefits of ACEIs or ARBs for MAFLD patients with early-stage fibrosis need further study.

One international phase II placebo-controlled randomized comparative trial investigated the therapeutic effects of low-dose aspirin on MAFLD without cirrhosis. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to a low-dose aspirin group (81 mg once daily) and a placebo group, and treated for six months. The primary endpoint was a change in liver fat content based on MRS at six-month marks. The change in liver fat content was 3.6% in the placebo group, whereas it was − 6.6% in the low-dose aspirin group (difference between groups: − 10.2%, 95% confidence interval [CI] − 27.7 to − 2.6, p = 0.009). [234]

Statins have shown potential benefits on liver function tests in patients with MAFLD [235, 236], but their efficacy on steatosis or fibrosis is uncertain. Recently, ezetimibe with rosuvastatin treatment reduced liver fat as assessed by MRI-PDFF, but not fibrosis [237]. Future studies with larger sample sizes and robust endpoints are required, ideally based on plausible mechanistic data.

Pipeline of new drug treatments

A number of new drugs have shown promise in phase 2b or registration phase 3 studies. With the approval of Resmetirom by the FDA in March 2024, it is anticipated that more pharmacotherapies may be available for the treatment of MASH in the foreseeable future. Resmetirom, a selective thyroid hormone receptor-beta agonist, demonstrated positive results in two phase 3 studies. In the MAESTRO-NASH study, patients with biopsy-proven at-risk MASH were randomized to placebo (n = 318), resmetirom 80 mg (n = 316) or resmetirom 100 mg (n = 321) [238]. The study reached both interim histological endpoints at week 52. MASH resolution with no worsening of fibrosis was achieved in 26% and 30% in the resmetirom 80 mg and 100 mg arms, respectively, compared with 10% in the placebo arm. Fibrosis improvement without worsening of MASH occurred in 24% in the 80 mg arm, 26% in the 100 mg arm, and 14% in the placebo arm. In the accompanying MAESTRO-NAFLD-1 study based entirely on noninvasive tests, resmetirom again demonstrated superiority in reducing hepatic fat, liver stiffness, serum LDL-cholesterol, apolipoprotein B and triglycerides [239]. Resmetirom is well tolerated with a mild increase in diarrhea and nausea. No cardiovascular toxicity has been reported. Prescribing resmetirom necessitates thorough patient assessment by a specialist and should be overseen within a multidisciplinary context. Resmetirom can be considered in patients with stage 2 or stage 3 fibrosis or those with histological evidence of steatohepatitis, using several non-invasive criteria or liver biopsy, depending on their availability in individual practice settings. It is recommended that patients in the early stages of MAFLD not be treated, as also patients likely to have established cirrhosis. The benefits of resmetirom in this population are still being assessed in a phase 3 cirrhosis trial. Patients meeting treatment criteria should receive weight-based dosing, with 80 mg for patients weighing less than 100 kg and 100 mg for those weighing over 100 kg. There are still unanswered questions regarding the duration of treatment and the criteria for stopping treatment due to lack of effectiveness. Ongoing analysis of emerging data, including real-world evidence, is likely to provide further guidance in the future, especially concerning monitoring therapeutic response and clinical outcomes.

One of the biggest breakthroughs in the management of obesity and T2DM is the introduction of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA). This class of drugs reduces appetite and slows gastric emptying, resulting in weight loss of 5–15% [240]. In clinical trials with long-term follow-up, GLP-1RAs also reduced major adverse cardiovascular events and mortality. In a phase 2b study in patients with MASH, semaglutide at a dose of 0.4 mg daily given subcutaneously for 72 weeks achieved MASH resolution with no worsening of fibrosis in 59% of patients, compared with 17% in the placebo group, though differences in fibrosis improvement did not reach statistical significance [241]. In a subsequent study in patients with compensated MASH-related cirrhosis, semaglutide at a dose of 2.4 mg weekly failed to increase the rate of either MASH resolution or fibrosis improvement [242]. This suggests that the weight loss effect of GLP-1RAs, though potent, may be too late for patients with advanced liver disease. Currently, dual and triple incretin agonists involving glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon receptor are under development. The newer drugs have demonstrated superiority in reducing body weight and glycated hemoglobin compared to GLP-1RA alone, but their effects on MASH and liver fibrosis remain to be proven [243, 244]. Tirzepatide is a single molecule that combines glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 receptor agonism; it demonstrated positive effects on both MASH resolution and fibrosis improvement in a relatively short phase 2 study [243]. These promising results need to be replicated in phase 3 studies, which are underway. The need for subcutaneous injections and gastrointestinal side effects (most notably nausea and vomiting and the potential increased risk of pancreatitis) are the main liability of this class of drugs, with treatment cessation required in around 10% of patients. Survodutide is another GLP-1/glucagon dual agonist that demonstrated histological improvement of MASH in a phase 2 randomized trial [245].

Lanifibranor (a pan-PPAR agonist) [246] and fibroblast growth factor-21 analogues (e.g., efruxifermin and pegozafermin) have also shown promising results in early-stage clinical trials, while phase 3 studies are underway [247, 248].

Monitoring progress and response to treatment

There is currently no agreement on the most effective approach for monitoring patients with MAFLD and their response to pharmacotherapy [249]. Given that the severity of fibrosis is the principle determinant of both liver-related outcomes and mortality, and as patients with MAFLD are expected to progress by an average of 0.12 (range: 0.07 − 0.18) fibrosis stages per year [[58](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR58 "Singh S, Allen AM, Wang Z, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Loomba R. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.014

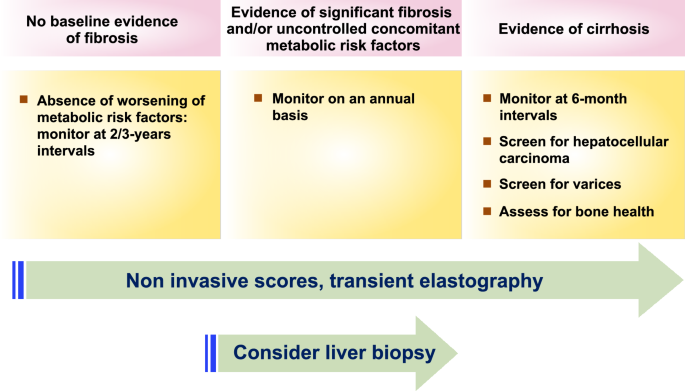

"), [250](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#ref-CR250 "Taylor RS, Taylor RJ, Bayliss S, Hagström H, Nasr P, Schattenberg JM, et al. association between fibrosis stage and outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):1611-1625.e1612")\], the following algorithm is recommended (Fig. [2](/article/10.1007/s12072-024-10774-3#Fig2)).Fig. 2

Monitoring protocol for patients with MAFLD in clinical practice

Interval of follow-up

- Patients without fibrosis should be monitored at 2–3 years intervals if there has been no worsening of concomitant metabolic risk factors.

- Patients with fibrosis or evidence of uncontrolled concomitant metabolic risk factors should be monitored on an annunal basis, particularly with the emergence of new drugs.

- For selected patients at high risk of fibrosis progression, monitoring might involve baseline liver biopsy assessment, unless they already have established cirrhosis, where MELD scoring may be required.

- Patients with cirrhosis should undergo monitoring at 6-month intervals, including surveillance for HCC and even clinically significant portal hypertension (please see the next sections for details).

Method of follow-up

Monitoring for fibrosis progression in clinical settings can rely on a combination of noninvasive scores (such as FIB-4) and liver stiffness measurement, although this approach requires further validation.

Patient-reported outcomes

A person living with MAFLD plays a vital role in their disease management as the cornerstone of treatment is adherence to a healthy diet and being physically active [24, 156, 251]. Despite the high prevalence of MAFLD, it has a lower level of awareness among the general population compared to that of other metabolic diseases. A global study of patients with MAFLD reported an impairment in quality of life [252]. The impairment of health status is more pronounced in patients with advanced liver disease [253, 254]. This calls for strategic efforts to integrate prevention and management with patient involvement at the core.

Systematic reviews of studies of people with chronic liver diseases including MAFLD reveal several unmet needs which could help them better cope with their chronic illness and improve their quality of life. Affected communities have highlighted the need for high-quality education and health promotion information to better understand and manage their disease, and the need for support services [253]. For the initiation and maintenance of lifestyle change in patients with MAFLD and for patient empowerment, there is evidence to support the use of digital technology for providing their screening results together with advice on lifestyle changes [255, 256]. Recommendations for empowering patients with MAFLD are provided in supplementary Table 1.

MAFLD-related cirrhosis

With the prevalence of MAFLD increasing worldwide, a considerable proportion will progress to cirrhosis and other associated complications [257]. In a Medicare data analysis of over 10 million patients, the cumulative risk of progression to cirrhosis was 39%, and from compensated to decompensated cirrhosis it was 45%, over 8 years of follow-up [258].

Medical history and physical examination can identify patients with or at risk for cirrhosis. The diagnostic criteria for MAFLD cirrhosis is patients with cirrhosis who do not exhibit typical histology but have past or present evidence of metabolic risk factors that meet the criteria for diagnosing MAFLD. These patients can be diagnosed as having MAFLD cirrhosis if they in addition, meet at least one of the following additional criteria. a) documentation of steatosis on a previous liver biopsy; b) historical documentation of steatosis by hepatic imaging [24, 259].

Portal hypertension assessment in patients with MAFLD

In patients with MAFLD, the presence of portal hypertension is not always aligned with liver disease progression and is recognised to occur in people with MAFLD but without cirrhosis [260, 261]. Therefore, early detection of the possible complications of portal hypertension, such as the presence of esophageal as well as gastric varices is important. Additional clinical features that are surrogate markers of clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH) include the presence of intraabdominal varices by imaging, and ascites.

Hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) measurement is the gold standard for portal hypertension assessment. However, this procedure might not be feasible in the same session as esophagogastroduodenoscopy for variceal screening and is not widely accessible in many APASL countries [263,264,264]. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided portal pressure gradient has recently been studied for more accurate portal hypertension assessment, especially in the presence of varices. This can be performed together with other procedures such as endoscopic band ligation, EUS-guided liver biopsy, and EUS-guided cyanoacrylate injection of large gastroesophageal varices [266,267,267]. However, considerable technical expertise is required to establish these evolving procedures. The combination of baseline liver stiffness measurement and platelet count (Baveno-VII criteria) correlates with CSPH and could be used to define CSPH. The recently proposed novel prediction model, the LS-spleen diameter to platelet ratio score (LSPS), uses TE values and the spleen diameter to platelet ratio, which also reflects CSPH [268]. Additionally, the ANTICIPATE model predicts CSPH in patients with viral and alcohol-related cACLD using two parameters: platelet count and LSM. The ANTICIPATE–NASH model is an adapted version for MAFLD patients, incorporating BMI. This model could be a valuable clinical tool for assessing the risk of liver-related events in MAFLD patients [269].

Screening for varices in MAFLD cirrhosis

There is insufficient data to support the utilization of any serological markers such as platelet count alone or the enhanced liver fibrosis panel to exclude CSPH and eliminate the need for endoscopic assessment in detecting varices that require treatment. LSM is recommended for determining thresholds for non-invasive screening of varices in patients with MAFLD-related cirrhosis. LSM less than 9 kPa, in the absence of other known clinical signs, rules out compensated advanced chronic liver disease (cACLD). LSM ≥ 15 kPa is suggestive of cACLD [270]. An LSM ≥ 25 kPa indicates CSPH and a CAP less than 220 dB/m, measured using the XL probe identifies patients with MAFLD-related cACLD who are at high risk for decompensation [270]. The threshold of 21 kPa was confirmed independently to be associated with a higher occurrence of hepatic decompensation. Not only baseline LSM but also change in LSM is associated with the risk of liver-related events and mortality [271].

In patients with MAFLD-related cirrhosis, although HVPG ≥ 10 mmHg remains strongly associated with the presence of clinical signs of portal hypertension, these signs can also be present in a small proportion of patients with HVPG values < 10 mmHg. About 40–50% of patients with MAFLD belong to the “gray zone” of LSM 15–25 kPa, in which a precise estimation of the risk of CSPH is not possible. In this instance, spleen stiffness measurement (SSM) can be used to reduce the proportion of patients in the indeterminate group [272, 273]. About 40–60% of patients in the Baveno VII diagnostic algorithm remain in the grey zone. The addition of SSM (40 kPa) to the model significantly reduced the grey zone to 7–15%, maintaining adequate negative and positive predictive values [274].

Non-selective beta blocker(s) (NSBBs) such as propranolol, nadolol, or carvedilol should be considered as a treatment to prevent decompensation in patients with CSPH. Carvedilol is the preferred NSBB for compensated cirrhosis because it effectively reduces HVPG, has greater benefits in preventing decompensation, is better tolerated, and has been proven to improve survival compared to no active therapy in compensated patients with CSPH [275]. The decision to use NSBBs should be based on clinical indicators, regardless of the ability to measure HVPG. Patients with compensated cirrhosis who are taking NSBBs to prevent decompensation do not require a screening endoscopy to detect varices, as endoscopy will not change their management.

Individuals with compensated cirrhosis who cannot initiate NSBB use (due to contraindication or intolerance) to prevent decompensation should undergo an endoscopy for variceal screening if their LSM is 20 kPa or higher, or if their platelet count is 150 × 10^9/L or lower. For patients unable to use NSBBs and requiring an endoscopy based on the Baveno VI criteria (LSM by TE ≥ 20 kPa or platelet count ≤ 150 × 10^9/L), spleen stiffness measurement by TE of 40 kPa or lower can identify those at low risk of high-risk varices, potentially making endoscopy unnecessary. Patients with cACLD who are on NSBB therapy and show no clear signs of CSPH (LSM < 25 kPa), should be considered for repeat endoscopy, preferably after 1–2 years. If no varices are detected, NSBB therapy can be stopped. In cACLD patients with high-risk varices who cannot use NSBBs due to contraindications or intolerance, endoscopic band ligation is recommended to prevent the first occurrence of variceal bleeding.

Screening for HCC

MAFLD is a major etiology for HCC in the Asia–Pacific region with substantial morbidity and mortality; its prevalence is expected to further increase in the coming decades. [2, 24, 277,278,279,280,281,281] In addition, MAFLD is associated with the onset/recurrence of HCC and poor prognosis in patients with viral hepatitis [283,284,285,286,287,288,289,290,290].

When HCC is diagnosed at an early stage, there are existing acceptable and curative therapies, for example, surgical resection, local ablation, or liver transplantation [291]. Therefore screening can reduce HCC-specific mortality and is recommended [292, 293].

The key concern about surveillance/screening for HCC is the threshold (annual incidence of HCC), with the aim of reaching cost-effectiveness. Based on cost-effectiveness analyses, when the incidence of HCC is > 1 or 2%/year, it is cost-effective to perform HCC screening/surveillance [295,296,297,297]. In contrast, when the incidence of HCC is < 0.2%/year, the cost-effectiveness is poor and screening is not recommended [295,296,297,297].

For MAFLD-related HCC, the threshold for screening is recommended at 1%/year [296]. Thus, for MAFLD-related cirrhosis subjects (annual incidence of HCC: 1–1.5%/year), screening is cost-effective and recommended [296,297,298,298]. In contrast, for MAFLD-related non-cirrhosis patients, the annual incidence of HCC is 0.08–0.63 per 1,000 person-years [298]. Thus, screening of this low-risk population is not recommended.

Notably, recent epidemiologic data reveals that about 35–47% of MAFLD-related HCCs develop in people without cirrhosis [299, 300]. Accordingly, if the screening/surveillance is done only in patients with cirrhosis, HCC in subjects without cirrhosis would likely be diagnosed at a late stage with resultant poor outcomes. Nevertheless, if all subjects without cirrhosis with MAFLD are screened, then the cost-effectiveness would be quite low. To resolve this issue, more sensitive and reliable biomarkers of risk, or scoring systems for surveillance that improve cost-effectiveness is required [299,300,301,301]. In this way, patients with non-cirrhotic MAFLD but at higher risk of developing HCC can be identified and placed on surveillance. Commonly used screening tests (non-invasive tumor biomarkers such as AFP, AFP-L3, PIVKA-II; and liver imaging such as by ultrasonography) have low- intermediate sensitivity/specificity [292, 293], so their specific role in non-cirrhotic MAFLD is yet to be clarified. Alternatively, big data or the development of an AI-based prediction model may help in the identification of high-risk populations for HCC surveillance [299,300,301,302,302].

Management of MAFLD-related HCC

Control of metabolic dysfunction plays an important role in the management of patients with HCC [303]. A high BMI is one of the criteria for MAFLD diagnosis [304]. In Western populations, a high BMI is linked to higher HCC-related mortality [305]. However, there appears to be no relationship between a high BMI and HCC-related mortality in Asian patients based on meta-analysis and cohort studies [307,308,308]. Sarcopenia may explain this inconsistency, as it is highly prevalent in patients with HCC [310,311,312,312] and is a prognostic factor in Asian patients with HCC [307, 314,315,316,317,318,319,320,321,321].

Physical activity is linked to improved survival in HCC patients [322]. A recent meta-analysis revealed that combining resistance with aerobic exercise reduces serious adverse events [323].

T2DM is a criterion for MAFLD diagnosis. Metformin has been demonstrated to significantly reduce the risk of HCC in MAFLD patients with an HbA1c level above 7.0% [223]. Additionally, a meta-analysis demonstrated that metformin prolonged the survival of HCC patients with T2DM after curative HCC treatment [224]. Therefore, metformin, along with lifestyle intervention, may be a beneficial treatment for MAFLD-related HCC patients with T2DM.

Nutritional therapy focusing on protein intake and correcting amino acid imbalance might be beneficial for the management of patients with MAFLD-related HCC. The administration of branched-chain amino acids is useful for the management of adverse events from the treatment of HCC. Theoretically, this includes improvements in body composition and nitrogen balance, liver cell regeneration, protein and albumin synthesis and immune function [324].

Liver transplantation is the treatment of choice for patients with early HCC whose liver function does not allow for surgical resection. It is also recommended for patients with a locally advanced disease if their tumors can be reduced in size, number, and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) production to acceptable levels through locoregional therapy. Immunotherapy is currently the first-line treatment for unresectable HCC not amenable to locoregional therapy. However, its anti-tumor effect has been reported to be limited for MAFLD-related HCC [325, 326]. Lenvatinib is a multi-kinase inhibitor and effectively inhibits the tumor vasculature, resulting in anti-tumor effects. Lenvatinib is used for the treatment of unresectable HCC and treatment response and prognosis is reported to be better in HCC patients with MAFLD than non-MAFLD [327]. In other studies, lenvatinib is associated with a significant survival benefit compared to immunotherapy in patients with MAFLD-related HCC [326, 328].

MAFLD is associated with various extra-hepatic complications and since these events could affect the prognosis and quality of life of patients, those with MAFLD-related HCC need to be managed with attention not only to the liver but also to systemic complications.

Liver transplantation for MAFLD

MAFLD has emerged as a leading indication for liver transplantation globally for both decompensated cirrhosis and for HCC, which introduces some unique challenges [329]. These patients are often older that those with other indications for liver transplantation and commonly have significant underlying comorbidities that increase the short and long-term risks of transplantation [330]. The over-representation of obesity, T2DM, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, peripheral and cerebro-vascular disease, CKD [330, 331], and sarcopenia [332] all increase the risk and complexities of liver transplantation. Even if successfully transplanted, the long-term risks from cardiovascular disease, CKD and malignancy often remain [333]. Despite these added risks, well-selected patients with MAFLD-related HCC appear to have posttransplant survival equivalent to other patient groups[330], however those with decompensated MAFLD cirrhosis, particular with CKD requiring simultaneous liver and kidney transplantation, may have significantly inferior outcomes [334, 335].

Patient selection for transplantation requires a detailed assessment of end-organ disease that may preclude liver transplantation. As cardiac complications are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in liver transplant recipients and MAFLD patients are at particular risk, a comprehensive cardiovascular assessment is essential to identify risks, to allow for pretransplant optimisation of cardiac status, and to potentially exclude some candidates. Pretransplant assessment in MAFLD patients should be standardised and usually should incorporate electrocardiography, transthoracic and stress echocardiography, and in some patients, coronary CT angiography, invasive coronary angiography and cardiology consultation [336]. Even after MAFLD patients are placed on a transplant waiting list, challenges remain as they are less likely to receive a transplant and have higher waitlist mortality than non-MAFLD patients [337].

Donor selection for liver transplantation is impacted by the increasing rates of MAFLD and other metabolic diseases in the community that are present in both living and deceased donors. Moderate to marked steatosis in particular poses a significant risk of primary nonfunction, early allograft dysfunction and biliary strictures [338]. Potential living donors with obesity and steatosis may be able to be utilised with good outcomes particularly if subject to short-term weight loss interventions [339] but may be at risk for perioperative wound complications [340], and post-donation metabolic syndrome [341]. Steatotic deceased donor grafts are frequently discarded but may be able to be used in well-selected recipients and optimal peritransplant conditions [342]. Machine-based perfusion strategies may broaden the acceptability and utilisation of steatotic grafts in the future [343]. Patients transplanted for MAFLD may be adversely impacted by the presence of donor metabolic risk factors, particularly diabetes [344].

Patients transplanted for MAFLD are at risk of recurrent graft steatosis and complications of metabolic syndrome. Immunosuppressive medications may compound the risk for metabolic complications, and steroid minimisation or avoidance, and minimisation of calcineurin inhibitor dosing should be considered [345]. Multidisciplinary management with a focus on weight control (including consideration for bariatric surgery and its timing), optimal T2DM, hypertension and lipid management, and monitoring for complications is essential in transplant recipients to ensure good long-term outcomes of liver transplantation [346].

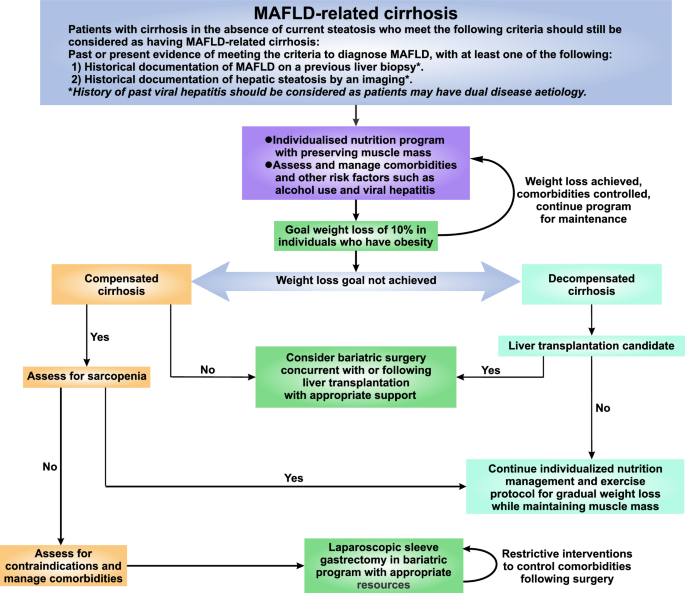

Management of the patient with MAFLD cirrhosis beyond normal cirrhosis care, and management of MAFLD-related hepatic decompensation

While standard cirrhosis care continues to apply in patients with MAFLD-associated cirrhosis, peculiarities distinct from other liver etiologies need to be considered (Fig. 3). Unlike other liver disease etiologies, as a multi-system disease, MAFLD is commonly intertwined with multiple metabolic comorbidities that may impact the progression of disease and its complications [347]. Optimization of these comorbidities is integral to manage MAFLD-related cirrhosis effectively [348].

Fig. 3

Recommended algorithm to diagnose and manage patients with MAFLD-related cirrhosis