Dust-climate couplings over the past 800,000 years from the EPICA Dome C ice core (original) (raw)

Abstract

Dust can affect the radiative balance of the atmosphere by absorbing or reflecting incoming solar radiation1; it can also be a source of micronutrients, such as iron, to the ocean2. It has been suggested that production, transport and deposition of dust is influenced by climatic changes on glacial-interglacial timescales3,4,5,6. Here we present a high-resolution record of aeolian dust from the EPICA Dome C ice core in East Antarctica, which provides an undisturbed climate sequence over the past eight climatic cycles7,8. We find that there is a significant correlation between dust flux and temperature records during glacial periods that is absent during interglacial periods. Our data suggest that dust flux is increasingly correlated with Antarctic temperature as the climate becomes colder. We interpret this as progressive coupling of the climates of Antarctic and lower latitudes. Limited changes in glacial-interglacial atmospheric transport time4,9,10 suggest that the sources and lifetime of dust are the main factors controlling the high glacial dust input. We propose that the observed ∼25-fold increase in glacial dust flux over all eight glacial periods can be attributed to a strengthening of South American dust sources, together with a longer lifetime for atmospheric dust particles in the upper troposphere resulting from a reduced hydrological cycle during the ice ages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

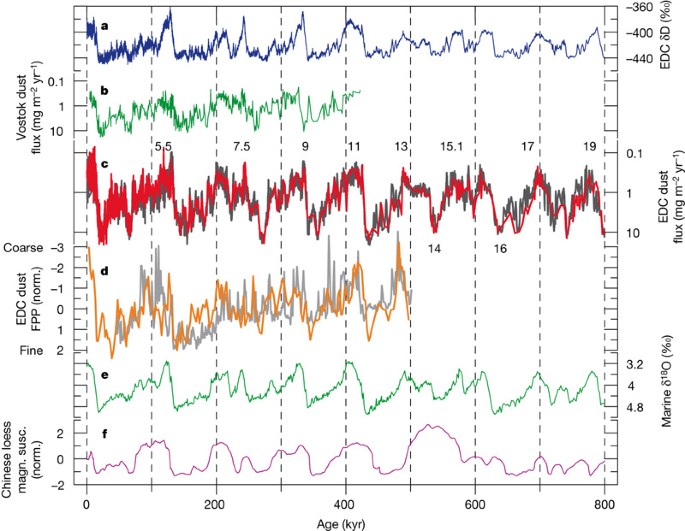

The EPICA (European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica) ice core drilled at Dome C (hereafter EDC) in East Antarctica (75° 06′ S; 123° 21′ E) covers the past 800,000 yr (Fig. 1a). The dust flux record of Vostok (Fig. 1b) is thus extended over four additional cycles (Fig. 1c). The glacial–interglacial climate changes are well reflected in the sequence of high and low dust concentrations with typical values from 800 to 15 μg kg-1 and a ratio of 50 to 1 over most of the past eight climate cycles. The concentration of insoluble dust in snow depends on a number of factors such as the primary supply of small mineral particles from the continents, which is related to climate and environmental conditions in the source region11, the snow accumulation rate, the long-range transport, and the cleansing of the atmosphere associated with the hydrological cycle. The strontium and neodymium isotopic signature of dust12 revealed that southern South America was the dominant dust source for East Antarctica during glacial times13, although contributions from other sources are possible during interglacials14. Because of the low accumulation rate at Dome C (∼3 cm yr-1 water equivalent), dry deposition is dominant and the atmospheric dust load is best represented by the dust flux15. The total dust flux and the magnitude of the glacial–interglacial changes are remarkably uniform within the East Antarctic Plateau, as shown by the similarity between the EDC and the Vostok records (Fig. 1b, despite some chronological differences and a 10-times finer resolution at EDC) over the past four climatic cycles and also depicted by the Dome Fuji dust record16 (not shown).

Figure 1: EDC dust data in comparison with other climatic indicators.

a, Stable isotope (δD) record from the EPICA Dome C (EDC) ice core8 back to Marine Isotopic Stage 20 (EDC3 timescale) showing Quaternary temperature variations in Antarctica. b, Vostok dust flux record (Coulter counter) plotted on its original timescale11. c, EDC dust flux records. Red and grey lines represent, respectively, Coulter counter (55-cm to 6-m resolution) and laser-scattering data (55-cm mean). Numbers indicate Marine Isotopic Stages. Note that the vertical extent of the scales of b and c is larger than for the other records. d, EDC dust size data expressed as FPP (see Methods). The orange and grey curves represent measurements by Coulter counter (2-kyr mean) and laser (1-kyr mean), respectively. e, Marine sediment δ18O stack18, giving the pattern of global ice volume. f, Magnetic susceptibility stack record for Chinese loess17 (normalized).

At EDC, interglacials display dust fluxes similar to that of the Holocene (∼400 μg m-2 yr-1). However, some differences can be seen in the record before and after the Mid-Brunhes Event (MBE, ∼430 kyr bp) which is considered a transition in the climatic record7,8 from cooler (for example Marine Isotopic Stages, MIS 13, 15, 17) to warmer (for example MIS 11, 9 and 5.5) interglacials. Before the MBE there were fewer occurrences of low concentrations, and warm periods represent ∼12% of the time, compared with ∼30% after the MBE. All eight glacial periods appear similar in magnitude and show an average increase in dust flux by a factor of about 25, with glacial maxima displaying fluxes of at least 12 mg m-2 yr-1. The weakest glacial stages in the EDC ice core are MIS 14 and 16. For MIS 14 this is consistent with the findings from terrestrial and marine records6,17,18. In contrast, MIS 16 in those records is the strongest glacial in the Late Quaternary period.

The extension of the EDC dust record to 800 kyr bp confirms the increased atmospheric dust load during cold periods of the Quaternary period with respect to warm stages. The first-order similarity of EDC dust with the global ice-volume record (Fig. 1e, _r_2 = 0.6) confirms that major aeolian deflation in the Southern Hemisphere was linked to Pleistocene glaciations. Comparison with the magnetic susceptibility record of loess/palaeosol sequences from the Chinese Loess Plateau (Fig. 1f) also provides evidence for broad synchronicity of global changes in atmospheric dust load.

EDC dust has been measured using both a Coulter counter and a laser sensor (see Methods). Laser measurements are obtained at higher resolution along the core, but dust size is difficult to calibrate; therefore only the relative variation of the signal is used. Overall, the Coulter counter and laser (relative) size records (Fig. 1d) are in good agreement. The slight discrepancies during MIS 5.5, 6 and 12 are possibly related to the different sampling resolution, as size data from the laser and Coulter counter represent a continuous 1.1-m average and discrete 7-cm subsamples every 0.5–6 m, respectively. From MIS 14 (∼2,900 m depth) and downwards in the ice core, the dust size profile is not available because of the presence of particle aggregates formed in the ice. This phenomenon, which needs further investigation, has been observed in the EDC core only in very deep glacial sections, where ice thinning becomes very important and in situ temperature higher than -8 °C may allow partial melting around particles. This problem was solved through sonication of the samples, which allowed us to obtain reliable concentration data (see Methods). For the upper part of the record, larger (smaller) particles are generally observed during warm (cold) periods, as reflected by the variability in the fine particle percentage (FPP)12, which is highest during the two last glacial periods. The advection of dust to central Antarctica involves the high levels of the troposphere and the small changes in dust size may reflect changes in the altitude of transport and thus transport time12. Higher FPP values in glacial times have been ultimately attributed to increased isolation of Dome C during glacials, in terms of reduced dust transport associated with greater subsidence12 or possibly through baroclinic eddies.

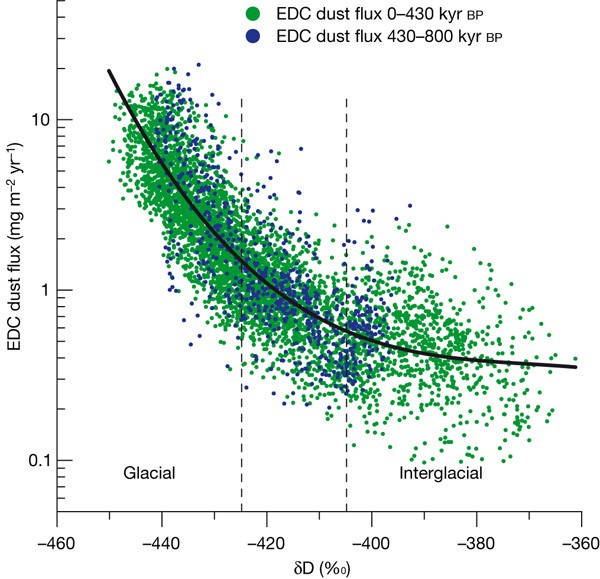

Comparing dust and stable isotope (δD) profiles, there is a significant correlation during glacial periods (Fig. 2), and up to 90% of the dust variability can be explained by the temperature variations. In glacial periods, most of the δD events (for example, Antarctic Isotopic Maxima) have their counterparts in the dust data shown by a reduction of dust concentrations. In contrast, dust and temperature records are not correlated during interglacial periods (Fig. 2). Indeed, the (logarithmic) relationship between dust flux and δD can be well fitted by a cubic polynomial (Fig. 3). Over the record, the geometric standard deviation from the polynomial fit represents a factor of ∼2 in concentrations independent of the climatic period. Similarly, this relationship does not change before and after the MBE. The crescent shape of the dust–δD relationship suggests that the dust fluxes have a higher temperature sensitivity as the climate becomes colder. For δD values above about –405‰, Antarctic temperature and dust flux are not correlated, whereas there is a clear correlation for δD values below about –425‰. This behaviour may represent the expression of a progressive coupling between high- and low-latitude climate as temperatures become colder. During extreme glacial conditions the coupling appears as a direct influence of the Antarctic on the climate of southern South America19,20. The coupling of Antarctic and lower-latitude climate is probably coincident with the significantly extended sea ice over the Southern Atlantic and the Southern Ocean during glacials21 and the consequent meridional (northward) shift of the atmospheric circulation (that is, the westerlies)19,20,21,22.

Figure 2: EDC correlation between dust and temperature.

Linear plot of dust flux (black) and the coefficient of determination _r_2 (blue) between the high-pass filtered values (18-kyr cut-off) of both the δD and the logarithmic values of dust flux. The correlation was determined using 2-kyr mean values in both records and a gliding 22-kyr window. Correlations above _r_2 = 0.27 (dashed line) are significant at a 95% confidence level. Numbers indicate the marine isotopic glacial stages.

Figure 3: EDC dust–temperature relationship.

Values of δD (ref. 8) are plotted against dust flux (both at 55-cm resolution). Green and blue dots represent data from 0–430 kyr bp and 430–800 kyr bp, respectively. Superposed is a cubic polynomial fit, log10(f) = -3.737 × 10-6(δD)3 - 4.239 × 10-3(δD)2 - 1.607(δD) - 204, where f is the dust flux (mg m-2 yr-1), and δD is in ‰ (_r_2 = 0.73, N = 5,164).

Questions remain about the main factors influencing the high dust input into polar areas during glacial periods. So far, general circulation models4,10 have reproduced a glacial dust transport and flux over tropical and mid-latitude regions which is in good agreement with global reconstructions3, but they have failed to simulate the 25-fold increase observed in glacial dust input over Antarctica. This shortcoming is currently attributed to an incomplete representation of the source strength23. In addition, most of the models suggest modest changes in atmospheric transport4,9,10, which seems supported by the relatively small changes in dust size in the EDC ice core, and by the comparison of the two EPICA ice cores24. Moreover, the suggestion that the 25-fold dust influx increase is mainly due to changes in source strength is challenged by evidence from South Atlantic marine records suggesting a 5- to 10-fold increase in the South American source strength25,26 during the last glacial period.

On the basis of the new EDC data set, we suggest a new hypothesis for the glacial–interglacial changes in transport of dust. The indication (Fig. 3) that Antarctica and the southern low latitudes experienced a different coupling during the past 800 kyr is closely linked with the dust pathway within the high troposphere and the likely extended lifetime. With respect to the dust emitted from continents, the dust arriving in Antarctica, with a mode around 2 μm diameter27, represents the endmember of the distribution. The small size of dust particles makes en route gravitational settling inefficient (very long dry deposition lifetime), allowing mixing and spreading at high altitude within the troposphere. The lifetime of the particles is primarily constrained by wet deposition23,28 and therefore by water content and temperature. As an example, along a pathway 4–6 km high and with a mean temperature of about –40 °C (conditions similar to those observed over Antarctica), a temperature reduction by 5 °C, associated with a similar change of sea surface temperature over the Southern Ocean29, reduces the saturation water vapour pressure to about half. Under such premises, a two-dimensional model28 obtained an increase in dust flux to Antarctica of up to a factor of 5. Thus the roughly 25-fold increase in dust flux over the Antarctic plateau during glacials could be explained by a progressive coupling of the climate of Antarctic and lower latitudes with colder temperatures, one influencing the other, and leading to the stronger aeolian deflation of southern South America and to a significantly increased dust particle lifetime along their pathway in the high-altitude troposphere over the Southern Ocean. The new EDC data set thus provides important constraints for models of the dust cycle during glacial–interglacial cycles.

Methods Summary

Apparatus

Samples for Coulter Counter Multisizer IIe measurements were obtained from discrete samples (7 cm long), decontaminated at LGGE through washing in ultrapure water. We adopted the analytical procedure described in ref. 12 (and references therein). A total of about 1,100 values have been obtained.

We obtained laser scattering data from the University of Copenhagen device for the section between 0 and 770 m. The University of Bern device was used between 770 and 3,200 m. Data from both devices were calibrated by Coulter counter. Sampling resolution is about 1 cm.

Particle size distribution

Dust size is expressed as FPP. We define FPP according to ref. 12 as the proportion of the mass of particles having diameter between 1 and 2 μm with respect to the total mass of the sample, which typically includes particles in the size range 1 to 5 μm. This parameter is inversely correlated with the modal value of the log-normal dust mass (volume) size distribution.

From a depth of 2,900 m and below, some glacial samples show distributions with an anomalously large mode. This has been attributed to particle aggregate formation in ice (Supplementary Fig. 1) and prompted us to discard all size distribution data below that point until this phenomenon is better understood. To obtain reliable dust mass, samples were submitted to ultrasonic treatment to break the aggregates apart. Between 3,139-m and 3,190-m depth, 42 samples with anomalous size distribution were submitted to ultrasonic treatment. For 39 of these we accepted the new dust mass measurement, with 11 samples showing a significantly different mass value (Supplementary Table 1). Measurement on a few chosen samples above 3,139-m depth showed normal size distribution and concentration values. However, additional measurements are scheduled for in-depth analysis of the aggregate problem.

References

- Tegen, I. Modeling the mineral dust aerosol cycle in the climate system. Quat. Sci. Rev. 22, 1821–1834 (2003)

Article ADS Google Scholar - Fung, I. et al. Iron supply and demand in the upper ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 14, 281–296 (2000)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Kohfeld, K. E. & Harrison, S. P. DIRTMAP: the geological record of dust. Earth Sci. Rev. 54, 81–114 (2001)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Mahowald, N. et al. Dust sources and deposition during the last glacial maximum and current climate: A comparison of model results with paleodata from ice cores and marine sediments. J. Geophys. Res. 104, 15895–15916 (1999)

Article ADS Google Scholar - Steffensen, J. P. The size distribution of microparticles from selected segments of the Greenland Ice Core Project ice core representing different climatic periods. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 26755–26763 (1997)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Sun, Y. B., Clemens, S. C., An, Z. S. & Yu, Z. W. Astronomical timescale and palaeoclimatic implication of stacked 3.6-Myr monsoon records from the Chinese Loess Plateau. Quat. Sci. Rev. 25, 33–48 (2006)

Article ADS Google Scholar - EPICA community members. Eight glacial cycles from an Antarctic ice core. Nature 429, 623–628 (2004)

- Jouzel, J. et al. Orbital and millennial Antarctic variability over the last 800 000 years. Science 317 10.1126/science.1141038 (2007)

- Krinner, G. & Genthon, C. Tropospheric transport of continental tracers towards Antarctica under varying climatic conditions. Tellus 55B, 54–70 (2003)

Article ADS Google Scholar - Werner, M. et al. Seasonal and interannual variability of the mineral dust cycle under present and glacial conditions. J. Geophys. Res. 107 10.1029/2002JD002365 (2002)

- Petit, J. R. et al. Climate and atmospheric history of the past 420,000 years from the Vostok ice core, Antarctica. Nature 399, 429–436 (1999)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Delmonte, B. et al. Dust size evidence for opposite regional atmospheric circulation changes over east Antarctica during the last climatic transition. Clim. Dyn. 23, 427–438 (2004)

Article Google Scholar - Lunt, D. J. & Valdes, P. J. Dust transport to Dome C, Antarctica at the Last Glacial Maximum and present day. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 295–298 (2001)

Article ADS Google Scholar - Revel-Rolland, M. et al. Eastern Australia: A possible source of dust in East Antarctica interglacial ice. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 249, 1–13 (2006)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Wolff, E. et al. Southern Ocean sea-ice extent, productivity and iron flux over the past eight glacial cycles. Nature 440, 491–496 (2006)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Fujii, Y., Kohno, M., Matoba, S., Motoyama, H. & Watanabe, O. A 320 k-year record of microparticles in the Dome Fuji, Antarctica ice core measured by laser-light scattering. Mem. Natl Inst. Polar Res. 57, 46–62 (2003)

Google Scholar - Kukla, G., An, Z. S., Melice, J. L., Gavin, J. & Xiao, J. L. Magnetic susceptibility record of Chinese Loess. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 81, 263–288 (1994)

Article Google Scholar - Lisiecki, L. E. & Raymo, M. E. A. Pliocene–Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic delta O-18 records. Paleoceanography 20, 1–17 (2005)

Google Scholar - Iriondo, M. Patagonian dust in Antarctica. Quat. Int. 68, 83–86 (2000)

Article Google Scholar - Markgraf, V. et al. Paleoclimate reconstruction along the Pole-Equator-Pole transect of the Americas (PEP 1). Quat. Sci. Rev. 19, 125–140 (2000)

Article ADS Google Scholar - Gersonde, R., Crosta, X., Abelmann, A. & Armand, L. Sea-surface temperature and sea ice distribution of the Southern Ocean at the EPILOG Last Glacial Maximum: A circum-Antarctic view based on siliceous microfossil records. Quat. Sci. Rev. 24, 869–896 (2005)

Article ADS Google Scholar - Stuut, J.-B. W. & Lamy, F. Climate variability at the southern boundaries of the Namib (southwestern Africa) and Atacama (northern Chile) coastal deserts during the last 120,000 yr. Quat. Res. 62, 301–309 (2004)

Article Google Scholar - Mahowald, N. M. et al. Change in atmospheric mineral aerosol in response to climate: Last glacial period, preindustrial, modern, and doubled carbon dioxide climates. J. Geophys. Res. 111 10.1029/2005JD006653 (2006)

- Fischer, H. et al. Reconstruction of millennial changes in dust emission, transport and regional sea ice coverage using the deep EPICA ice cores from Atlantic and Indian Ocean sector of Antarctica. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 260, 340–354 (2007)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Kumar, N. et al. Increased biological productivity and export production in the glacial Southern Ocean. Nature 378, 675–680 (1995)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Chase, Z. & Anderson, R. F. Evidence from authigenic uranium for increased productivity of the glacial Subantarctic Ocean. Paleoceanography 16, 468–478 (2001)

Article ADS Google Scholar - Delmonte, B., Petit, J.-R. & Maggi, V. Glacial to Holocene implications of the new 27000-year dust record from the EPICA Dome C (East Antarctica) ice core. Clim. Dyn. 18, 647–660 (2002)

Article Google Scholar - Yung, Y. L., Lee, T., Wang, C. H. & Shieh, Y. T. Dust: A diagnostic of the hydrologic cycle during the last glacial maximum. Science 271, 962–963 (1996)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Stenni, B. et al. A late-glacial high-resolution site and source temperature record derived from the EPICA Dome C isotope records (East Antarctica). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 217, 183–195 (2004)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank H. Fischer, E. Wolff, T. Blunier, R. Gersonde, B. Stauffer and M. Renold for their comments and suggestions. This work is a contribution to the European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica (EPICA), a joint European Science Foundation/European Commission scientific programme, funded by the European Commission and by national contributions from Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. This is EPICA publication no. 193.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Climate and Environmental Physics, Physics Institute, University of Bern, Sidlerstrasse 5, 3012 Bern, Switzerland ,

F. Lambert, M. Bigler, P. R. Kaufmann & T. F. Stocker - Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research, University of Bern, 3012 Bern, Switzerland

F. Lambert, P. R. Kaufmann & T. F. Stocker - Environmental Sciences Department, University of Milano Bicocca, Piazza della Scienza 1, 20126 Milano, Italy,

B. Delmonte & V. Maggi - Laboratoire de Glaciologie et Géophysique de l'Environment (LGGE), CNRS-University J. Fourier, BP96 38402 Saint-Martin-d’Hères cedex, France ,

J. R. Petit - Centre for Ice and Climate, Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Juliane Maries Vej 30, 2100 Copenhagen OE, Denmark ,

M. Bigler & J. P. Steffensen - British Antarctic Survey, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK ,

M. A. Hutterli - Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Columbusstrasse, 27568 Bremerhaven, Germany ,

U. Ruth

Authors

- F. Lambert

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - B. Delmonte

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - J. R. Petit

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - M. Bigler

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - P. R. Kaufmann

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - M. A. Hutterli

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - T. F. Stocker

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - U. Ruth

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - J. P. Steffensen

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - V. Maggi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence toJ. R. Petit.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lambert, F., Delmonte, B., Petit, J. et al. Dust-climate couplings over the past 800,000 years from the EPICA Dome C ice core.Nature 452, 616–619 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06763

- Received: 14 May 2007

- Accepted: 21 January 2008

- Issue Date: 03 April 2008

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06763