A decade after SARS: strategies for controlling emerging coronaviruses (original) (raw)

- Review Article

- Published: 11 November 2013

Nature Reviews Microbiology volume 11, pages 836–848 (2013)Cite this article

- 35k Accesses

- 462 Citations

- 198 Altmetric

- Metrics details

Subjects

Key Points

- Two highly pathogenic human coronaviruses, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), have emerged in the past decade. The lack of any clinically approved antiviral treatments or vaccines for either virus emphasizes the importance of the design of effective therapeutics and preventives.

- Bats have been implicated as reservoirs of both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV as well as related viruses and other human coronaviruses (HCoVs), such as HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63. The dispersion of bat species over much of the globe probably enhances their potential to act as reservoirs for pathogens, some of which are extremely virulent and potentially lethal to other animals and humans.

- Multiple animal models for SARS-CoV infection exist, although mouse models have been the most thoroughly characterized. Mouse-adapted SARS-CoV is capable of causing pathology that is representative of human infections in both young and aged animals.

- Small animal models for MERS-CoV infection have not yet been reported, although the possibility of further ongoing selection in the receptor-binding sequence in the spike protein or other sequences that are important for host specificity might contribute to this limitation. A mild disease phenotype that can include either localized or widespread pneumonia is observed in inoculated macaques.

- Multiple vaccine strategies have been attempted with coronaviruses, mostly (but not exclusively) targeting the spike glycoprotein. Successful live-attenuated vaccines have utilized reverse genetic strategies to delete the envelope protein or inactivate the exonuclease activity of non-structural protein 14 (nsp14) .

- MERS-CoV, similarly to SARS-CoV in 2003, has the potential to have a profound impact on the human population; however, its low penetrance thus far suggests that the virus might either ultimately fail to develop a niche in humans or it might still be adapting to human hosts and that the worst of its effects are yet to come.

- Coronavirus phylogeny shows an incredible diversity in antigenic variants, which leads to limited cross-protection against infection with different strains, even within a phylogenetic subcluster. Consequently, the risk of introducing novel coronaviruses into naive human and animal populations remains high.

Abstract

Two novel coronaviruses have emerged in humans in the twenty-first century: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), both of which cause acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and are associated with high mortality rates. There are no clinically approved vaccines or antiviral drugs available for either of these infections; thus, the development of effective therapeutic and preventive strategies that can be readily applied to new emergent strains is a research priority. In this Review, we describe the emergence and identification of novel human coronaviruses over the past 10 years, discuss their key biological features, including tropism and receptor use, and summarize approaches for developing broadly effective vaccines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

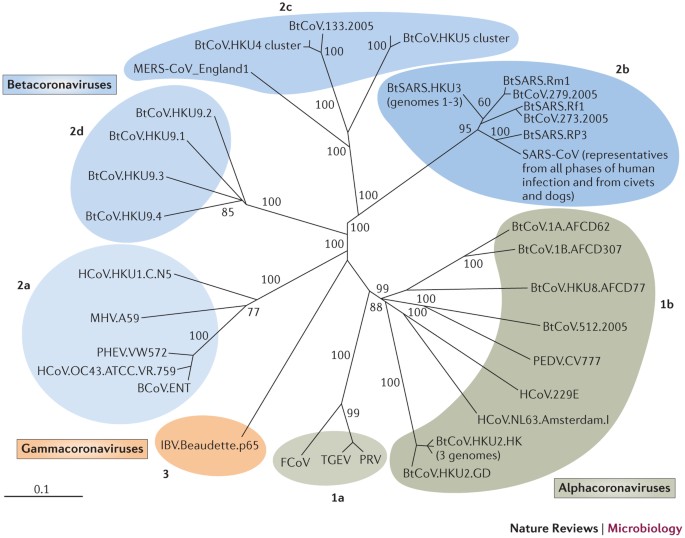

Coronaviruses are potentially lethal pathogens, and several novel strains have emerged or have been identified in animal and human populations in the past 10 years. The global severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) epidemic was recognized in early 2003 and caused 10–50% mortality in infected individuals, depending on their age1,2,3. SARS-CoV probably originated in bats, and the search for this reservoir has resulted in the vast expansion of the library of known coronaviruses. Many of these viruses infect various bats and other animal species, and several are phylogenetically similar to known pathogenic human coronaviruses4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, which suggests that additional emergence events are highly likely to occur. Indeed, recent reports have confirmed the emergence of a novel coronavirus, designated Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), which causes ∼50% mortality in patients who seek medical attention, is transmissible on close contact and has caused transmission clusters and cases in several countries, including Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Qatar and the United Kingdom14. Bat species have been implicated as reservoirs of MERS-CoV, but these species are distinct from those that are thought to have been involved in the emergence of SARS-CoV6,12,15,16,17,18. Coronaviruses can also be major pathogens in animal populations; for example, porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus (PEDV), which is related to certain bat alphacoronaviruses (Fig. 1), is a major cause of economic loss in the swine industry in Europe and Southeast Asia and has now been detected in US herds (National Pork Board statement on PEDV).

Figure 1: Whole-genome phylogeny of representative coronaviruses.

The full genomic sequences of 50 coronaviruses were aligned and phylogenetically compared. Three distinct phylogenetic groups are shown: alphacoronaviruses (green), betacoronaviruses (blue) and gammacoronaviruses (orange). This taxonomical nomenclature replaced the former group 1, 2 and 3 designations, respectively. Deltacoronavirusesare newly characterized and are not shown. Classic subgroup clusters are marked as 2a–2d for the betacoronaviruses and 1a and 1b for the alphacoronaviruses. The tree was generated using maximum likelihood with the PhyML package. The scale bar represents nucleotide substitutions. Only nodes with bootstrap support above 70% are labelled.

The recent coronavirus emergence events that are summarized in this article indicate that coronaviruses have the potential to rapidly adapt and stably transmit to new species (see Box 1 for a discussion on the structure and proteins of coronaviruses). These observations, when paired with an apparently extensive zoonotic reservoir and the propensity of coronaviruses to emerge as highly virulent human pathogens, have spurred the development of animal models to investigate coronavirus replication, pathogenesis and vaccine efficacy. In addition, because coronavirus vaccines have historically exhibited poor capacity for cross-protection19, the design of methods to generate safe, effective vaccines that can be rapidly implemented during an emerging epidemic is a high priority. In this Review, we summarize the human coronavirus emergence events that have taken place over the past decade, highlight key biological properties that are unique to coronaviruses, discuss the development of animal models for characterizing coronavirus replication, pathogenesis, transmission and vaccine efficacy, and examine the various strategies that have been implemented for the production of safe and effective coronavirus vaccines.

Emergence of novel coronaviruses

Before 2003, two coronaviruses were known to cause human disease: human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E) and HCoV-OC43, both of which were identified in the 1960s. HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43 cause comparatively mild common colds, except in infants, the elderly and the immunocompromised, in whom symptoms can be more severe20,21. However, in early 2003, a previously uncharacterized virus that was associated with the development of SARS, which often progressed to severe lung disease, was isolated from humans. The infected patients exhibited atypical pneumonia that was characterized by diffuse alveolar damage and that had the potential to progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Box 2). SARS was first reported in Guangdong Province, China, and the disease quickly spread worldwide. After an unprecedented global containment effort, the final statistics included more than 8,000 infected individuals and nearly 800 deaths1,2,3,22. The virus, a lineage B betacoronavirus, was eventually named SARS-CoV and was found to have crossed to humans from zoonotic reservoirs, such as bats12, Himalayan palm civets (Paguma larvata) and raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides)23,24,25.

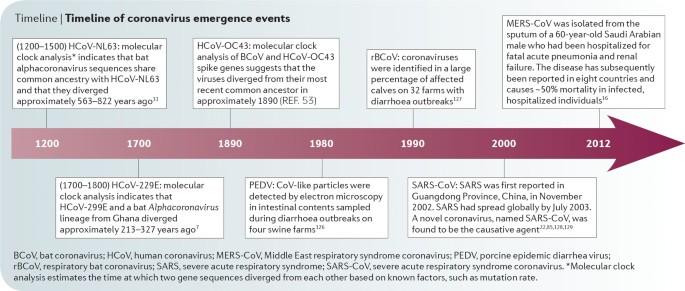

Subsequent to the SARS epidemic, two other coronaviruses that are capable of causing disease in humans, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-HKU1, were identified from archived nasopharyngeal aspirates26,27,28. These viruses cause mild to serious lower respiratory tract infections — including croup, bronchiolitis and pneumonia — in infants, children and adults, although the precise disease prevalence and severity, especially in the very young, are still being studied29. Although the characterization of these viruses was carried out very recently, molecular clock analyses indicate that HCoV-NL63 probably diverged from its nearest relative, HCoV-229E, around 500–800 years ago; however, as with all molecular clock analyses, these periods of time might be vastly under-estimated or over-estimated because of mutation masking and rate changes owing to purifying selection7,30,31 (Fig. 1; Fig. 2 (Timeline)).

Figure 2

Timeline of coronavirus emergence events

In June and September 2012, two cases of severe infections with another novel coronavirus were identified in the Eastern Mediterranean region6,16,17. Both patients succumbed to severe respiratory illness and, at the time of writing, 145 cases and 62 deaths associated with the novel MERS-CoV have been confirmed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC MERS-CoV incidence updates). MERS-CoV infection causes atypical pneumonia, ARDS and in some cases renal failure, which are often fatal; however the mortality rate cannot yet be accurately estimated owing to the small number of confirmed cases. Additionally, there is evidence that infection can cause less severe illness in cluster infections (such as those that occur among families and in hospitals) and can even be asymptomatic32,33,34. In addition to human infections, high seropositivity for MERS-CoV has been reported in camels, although the exact role of camels in virus transmission and maintenance in populations remains uncertain35. As is the case for SARS-CoV pathogenesis, the elderly seem to be especially vulnerable to poor disease outcomes as a result of MERS-CoV infection, particularly in the presence of co-morbidities such as diabetes, cardiac disease, hypertension and renal disease34. MERS-CoV is a lineage C betacoronavirus and is phylogenetically distinct from all known human coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV. MERS-CoV also uses a receptor that is distinct from that used by SARS-CoV and other human coronaviruses: MERS-CoV uses dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4), whereas SARS-CoV and HCoV-NL63 have been shown to use angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)36,37,38. This difference in receptor usage seems to affect tropism, as SARS-CoV infects type I pneumocytes, whereas MERS-CoV infects type II pneumocytes and non-ciliated bronchial cells39,40,41 (Table 1). Additionally, MERS-CoV is capable of both animal-to-human and human-to-human transmission: evidence shows that multiple animal-to-human transmission events have occurred in Saudi Arabia in addition to human-to-human transmission42,[43](/articles/nrmicro3143#ref-CR43 "Cotten, M. et al. Transmission and evolution of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia: a descriptive genomic study. Lancet http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61887-5

(2013)."), which suggests that MERS-CoV is still undergoing selection in animal and human hosts and will probably continue to do so if the virus is to firmly establish itself in humans. Furthermore, zoonotic isolates that might be related to MERS-CoV have been identified in bat species that are native to the Arabian peninsula, Mexico, Ghana and Europe[15](/articles/nrmicro3143#ref-CR15 "Annan, A. et al. Human betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012-related viruses in bats, Ghana and Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19, 456–459 (2013).").Table 1 Coronavirus receptor and co-receptor usage*

Coronavirus reservoirs: the hidden bat virome

Although investigators initially focused on Himalayan palm civets and raccoon dogs as potential reservoirs of SARS-CoV infection, multiple observations suggested that palm civets were opportunistic hosts rather than the primary reservoirs of SARS-CoV-like viruses in the wild. Marketplace civets were disproportionately positive for viral RNA in screening assays44, and samples that had been isolated from civets showed ongoing selection, which suggested that the virus was still adapting to the civet rather than persisting in equilibrium in this host44,45. In fact, bioinformatic analysis suggested that there were at least three and possibly more transmission events that occurred between civets and humans: the first occurred before the 2003 epidemic, as indicated by the presence of SARS-CoV antigens in serum samples from uninfected individuals; the second occurred during the main SARS epidemic in 2003; and the third occurred in the winter of 2003–2004 and consisted of a series of sporadic infections45,46. Additionally, molecular analysis of samples that were taken from healthy individuals in Hong Kong in 2001 revealed a prevalence rate of 1.8% for antibodies against SARS-related viruses, which suggests that SARS-CoV or a close ancestor circulated in humans before the 2003 epidemic47. In 2005, two groups independently reported the identification of SARS-CoV-related RNA sequences and anti-SARS nucleocapsid antibodies in Rhinolophus bats, particularly Rhinolophus sinicus and Rhinolophus macrotis12,13,23. Interestingly, high antibody titres correlated with low RNA levels, which suggests that active viral replication occurred in these bat species. Genomes from these viruses differ by approximately 10–15% from the 2003 epidemic SARS-CoV, which suggests that viruses with increased homology to SARS-CoV that are capable of using human and bat ACE2 orthologues for docking and entry could exist in bats.

With more than 1,100 species spanning 17 families, it is estimated that bats (order Chiroptera) comprise over 20% of all mammalian species. Their dispersion over much of the globe probably enhances their potential to act as reservoirs for pathogens, some of which are extremely virulent and potentially lethal to other animals and humans, including SARS-CoV48,49. Bats' natural roosting behaviours, in combination with ecological pressures that select for synanthropy, have brought bats closer to humans and to animals that live in proximity to humans, probably increasing the chances of bat-to-animal and bat-to-human transmission48,50. In fact, such a scenario has been proposed for the transmission of SARS-CoV-related coronaviruses from bats to humans: the bats roosted in or near open markets that sold civets in China; viruses were transmitted to civets via faecal and/or oral shedding; and humans handled civets and raw or improperly cooked civet meat, thus completing the transmission chain from bat to human. Alternatively, bats might have directly transmitted the virus to humans via shedding, incidentally co-infecting the civets. There is evidence in support of this hypothesis, as a genetically reconstructed R. sinicus bat SARS-CoV-related coronavirus was able to infect primate cells, mouse cells that expressed human ACE2 molecules and mice used to model SARS-CoV infection, and it was able to produce cross-neutralizing antibodies in these mice51.

Since 2005, dozens of previously unknown bat coronaviruses have been identified; in fact, so many bat coronaviruses are known to be distributed across the Coronaviridae family that there is enough evidence to suggest that bat coronaviruses were the ancestral sources of the alphacoronavirus and betacoronavirus genera5,9,15,31,52,53 (Fig. 1). Additionally, a recent study reported the transmission of a bat coronavirus between bats of two different suborders, which supports the hypothesis that bats can be co-infected with different coronaviruses and thus, could enable viral molecular recombination6. Given that two new human coronaviruses might have emerged from bats and that HCoV-NL63 has been shown to replicate in New World bat cells31, priorities for basic research and global health preparedness include determining the amount of virus diversity in bats and other species and, in parallel, mapping the breadth of bat coronavirus host ranges among different bat and animal species.

In addition to SARS-CoV, there is evidence that other human coronaviruses have emerged from bats, including HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63 and the newly emerged MERS-CoV. MERS-CoV-related viruses (which can be as little as ∼1.8% divergent from MERS-CoV) were identified in a recent survey of Pipistrellus bats that were captured in Ghana and Europe15. Bats that were sampled in Ghana also carried viral sequences that are phylogenetically similar to HCoV-229E15. Viral sequences that were sampled from North American Perimyotis bats have phylogenetic similarity to HCoV-NL63 (Ref. 31). Additionally, immortalized cells from Perimyotis bats are capable of hosting HCoV-NL63 infection, which supports the hypothesis that bats serve not only as reservoirs but also as reverse transmission conduits31. Clearly, there is substantial evidence that a broad array of coronaviruses persists in bats and that these viruses have the capacity to recombine and emerge as novel animal and human pathogens. Indeed, MERS-CoV is closely related to both HKU4 (which is a Tylonycteris bat coronavirus) and HKU5 (which is a Pipistrellus bat coronavirus); all three viruses probably emerged from a common ancestor several centuries ago. Additionally, many polymorphisms have been detected in HKU5 spike protein sequences, which suggests that this virus and, by extension, other bat coronaviruses are capable of generating mutants to occupy new ecological niches when they encounter novel hosts54.

Animal models for human coronaviruses

The continuing emergence of virulent human coronaviruses emphasizes the need for animal models for studying viral replication, pathogenesis and transmission. Thus far, this work has largely focused on SARS-CoV infection. SARS-CoV replication has been reported in mice, hamsters, cats, civets and primates, and the most severe disease symptoms have been observed in aged animals. MERS-CoV has a broad host range in vitro55, which provides some promise for the development of a small animal model for human disease in the near future. However, a functional small animal model for MERS-CoV replication or pathogenesis has not yet been characterized or reported; the possibility of ongoing selection in the receptor-binding sequence in the spike protein or other sequences that are important for host specificity might contribute to this limitation. Inoculation of rhesus macaques with 7 × 106 half-maximal tissue culture infectious doses (TCID50) of a MERS-CoV isolate results in transient mild-to-moderate clinical disease, which includes localized or widespread pneumonia56; however, the lack of a small animal model is clearly a major obstacle to furthering our understanding of viral pathogenesis and to testing vaccines and therapeutics.

SARS-CoV mouse models. Epidemic SARS-CoV strains that have been isolated from humans encode receptor-binding domains (RBDs) that interact well with human ACE2. These strains, particularly SARS-CoV Urbani, are capable of interacting with the mouse ACE2 orthologue and of replicating in mouse lungs and small intestine, but disease is limited to mild respiratory symptoms and minimal (<5%) weight loss. However, passage of SARS-CoV Urbani in BALB/c mice produced mouse-adapted variants (SARS-CoV MA15, SARS-CoV MA20 and SARS-CoV v2163) that cause severe and lethal respiratory disease that closely resembles the clinical illness observed in patients and that leads to pneumonitis and diffuse alveolar damage57,58,59. In young mice, adaptation requires 6–9 mutations, is focused on specific mutation sites (in the spike and membrane proteins) and takes approximately 15–25 passages; however, in aged mice, mouse-adapted strains emerge within five passages and are defined by fewer mutations, which occur at various locations across the genome. SARS-CoV mouse-adapted strains are significantly more pathogenic in 1-year-old, aged animals, as shown by ∼100- to 1,000-fold reductions in median lethal dose values, increased clinical disease severity, extensive ARDS-associated pathological lesions and increased mortality19,57,60,61,62,63. Viraemia is rare and transient in mice but is common and long-lasting in patients64. Sublethally infected mice develop neutralizing antibody responses, and passive transfer of sera from these mice protects recipients from subsequent lethal challenge. These observations reflect what probably occurred in infected humans during the epidemic: in a cohort study of 128 convalescent human samples, 50% were positive for T cell responses (CD8+ T cell responses were more frequent than CD4+ T cell responses), and 90% possessed strongly neutralizing antibodies. Of the T cell epitopes that were identified, most were in the spike protein65.

Other mouse strains are also susceptible to infection with SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV mouse-adapted strains, most notably 129SvEv-lineage mice and C57BL6 mice. This breadth of susceptibility facilitates the use of genetic knockout and transgenic animals, as most relevant transgenic and knockout lines are available in these backgrounds66,67,68,69; for example, myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88)-knockout and signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1)-knockout animals, which both have defects in innate immunity, develop severe disease with weight loss, pneumonitis and bronchiolitis, and die within 9 days of infection. In STAT1-knockout animals, death follows a brief convalescent period and a resurgence of the animal's inflammatory response63,70. By contrast, recombination activating gene (RAG)-knockout and severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice, which have defects in adaptive immunity, become persistently infected after SARS-CoV inoculation and maintain viral titres for at least 30–60 days after infection. There is no evidence of clinical disease during the course of the entire infection, probably owing to a lack of the inflammatory responses that would normally occur as a result of lymphocyte recruitment71.

Other SARS-CoV animal models. Syrian golden and Chinese hamsters have also been evaluated as models of SARS-CoV disease72,73,74,75. Infected animals develop pneumonitis, inflammation and immune cell infiltration, although signs of clinical illness do not necessarily accompany the lung pathology. In contrast to mice, hamsters experience transient (1–2-day) viraemia and become less active. In addition, the virus can be detected in the spleen and liver, although it is not associated with inflammation in these organs. Similarly to mice, hamsters also develop a protective neutralizing antibody response to subsequent SARS-CoV challenge. Reagents for measuring immune responses in the hamster are improving, but there is still limited availability of genetically defined animals and refined immunological and cellular markers for hamster models. TALEN-mediated mutagenesis and CRISPR–Cas-mediated mutagenesis of zygotes might enable the development of genetically defined hamsters and other atypical model species for pathogenesis research.

Ferrets support SARS-CoV replication in both the upper and lower respiratory tracts; however, studies have yielded variable results in terms of other signs of infection. Multifocal lesions develop over 5–10% of the lung surface area and are detected during gross pathological analysis, but clinical symptoms differ between studies76,77. Fever has been reported in SARS-CoV-infected ferrets, in addition to nasal discharge, sneezing and virus shedding; ferrets are the only animals that regularly develop fever when infected with SARS-CoV, a symptom that is a hallmark of human infections78,79. Ferrets have not been evaluated as a model for studies of SARS-CoV transmission, but their use might provide interesting information about the genetic basis of the super-spreader events that were observed during the 2002–2003 epidemic. As ferret and human ACE2 molecules probably require different mutations in the SARS-CoV RBD for optimal interactions to occur, it is probable that such 'transmission-evolved' ferret-adapted strains would efficiently replicate in ferrets, but less so in humans; however, such studies might highlight residues or regions that have roles in transmission and altered host specificity.

SARS-CoV has also been serially passaged in young F344 rats, which yielded a virus that was capable of enhanced replication and limited pathogenesis in young rats and more severe clinical disease in adult rats. Sequence analysis of the adapted mutant showed that there was a Y442S substitution in the spike protein80. In vitro passage of SARS-CoV on Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells that expressed rat ACE2 yielded a variant that encoded A811S and S950F substitutions in the spike protein81. Further sequence analysis of rat-adapted variants might help to identify interesting genetic correlates between serially passaged mouse and rat viruses.

Multiple non-human primates (NHPs) are susceptible to SARS-CoV infection, including rhesus macaques, cynomolgus macaques, marmosets and African green monkeys82,83,84,85. Clinical symptoms and pathology vary by species but all NHPs that support infection show evidence of SARS-CoV replication in the lungs (with 105–106 TCID50 titres in the lungs) and shedding in respiratory secretions. Most primate models develop histopathological changes and show evidence of pneumocyte infection and some degree of diffuse alveolar damage. Disease outcomes seem to be more severe in aged macaques86, which reflects human disease outcomes. As in humans, increased virus replication and increased lung pathology are noted in primates that are infected with wild-type SARS-CoV compared to most other animal models, except for mice that have been infected with mouse-adapted SARS-CoV. Few vaccine candidates have been evaluated in NHPs, probably owing to the cost and the challenge of achieving statistically significant sample sizes in NHP studies.

Prevention of human coronavirus disease

There are currently no approved antiviral treatments or vaccines for human coronavirus infections, including HCoV-NL63, HCoV-HKU1, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Studies have described small-molecule inhibitors that have the potential to control SARS-CoV infection, and in vitro studies have reported that the virus has partial ribavirin and interferon sensitivity at high doses, but clinical management of severe infections (which mostly occur in people infected with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV) is limited to supportive and palliative care14,87,88. Thus, the development of safe, stable vaccines is necessary, and, because these viruses rise rapidly out of heterogeneous, zoonotic pools, vaccines would ideally be broad-spectrum and rapidly adaptable to new coronaviruses. Of particular importance is the protection of the elderly, as they might be disproportionately susceptible to severe disease from both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infections. In support of this hypothesis, the median age of MERS-affected patients who experience disease that is severe enough to require medical attention is currently 50 years (with an age range from 14 months to 94 years) (WHO MERS-CoV incidence updates). Additionally, in the case of SARS-CoV, the elderly respond poorly to most vaccine formulations14,42,89. Multiple strategies have been used to generate coronavirus vaccines, which include inactivated virus vaccines, live-attenuated virus vaccines, viral vector vaccines, subunit vaccines and DNA or protein vaccines. Most studies have focused only on SARS-CoV vaccine development and have used animal models that do not recapitulate the severe clinical disease that occurs in humans (Table 2). To critically evaluate a vaccine, lethal-challenge models using viral strains that are homologous and heterologous to the vaccine strain in both young and aged animals are essential.

Table 2 Coronavirus vaccine strategies: advantages and disadvantages

Inactivated virus vaccines. Inactivated virus vaccines use chemicals (such as formalin, β-propiolactone and diethylpyrocarbonate) or radiation to render the viral genome non-infectious while maintaining the virion structure, thus preserving antigenicity but eliminating the potential to cause productive infection. Thus, in concept, inactivated virus vaccines are easily prepared and antigenically similar to the live virus. In SARS-CoV research, various studies have shown that inactivated vaccines elicit the production of neutralizing antibodies78,90,91,92, and administration of inactivated vaccines with or without adjuvants has been shown to protect against viral replication78,93,94. Vaccination and SARS-CoV challenge in primates and ferrets was reported to favour a T helper 2 (TH2) cell response that resulted in the production of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and subsequent IL-4-driven inflammatory pathology, rather than the macrophage-driven clearance that is observed in the typical antiviral TH1 response95. One particular inactivated SARS-CoV vaccine, double-inactivated vaccine (DIV), which uses alum as the adjuvant, was protective against challenge with the homologous virus; however, it induced eosinophilia and TH2 cell immune pathology with poor protection after challenge with a heterologous virus19. This type of response has been noted with other inactivated, vectored and DNA vaccines (see below). For respiratory syncytial virus, eosinophilic infiltrates are associated with increased mortality and exacerbated lung disease96. The eosinophilia that was observed in SARS-CoV-vaccinated animals was not age-dependent but might have promoted hypersensitivity in the presence of other inflammatory responses that are enhanced in aged animals, such as neutrophilia19. Inactivated SARS-CoV vaccines have been administered to humans; the vaccines were well tolerated and induced the production of neutralizing antibodies, although the participants were all relatively young (with an age range between 21 and 40 years) and lung pathology was not assessed. Additionally, in the absence of a natural challenge, no data on vaccine efficacy are available78,97.

Live-attenuated virus vaccines. Live-attenuated vaccines are produced by reducing or eliminating the virulence of a live virus, typically using chemical-driven or site-directed mutagenesis; thus, the virus is capable of productive infection but the resulting disease is either diminished or eliminated. Live-attenuated vaccines can elicit both innate and adaptive immune responses, and protection can be life-long. Additionally, their production is inexpensive98. The development of reverse genetics for coronaviruses, particularly SARS-CoV, has greatly simplified the investigation of attenuation-associated alleles and their resistance to reversion in cell culture and in mice and the evaluation of the efficacy of attenuated viruses as vaccine candidates. The envelope protein, which is involved in viral morphogenesis, intracellular trafficking and budding and which might possess ion channel activity, is dispensable for SARS-CoV production; however, replication is attenuated in SARS-CoV lacking this protein99. SARS-CoV lacking the envelope protein that was initially constructed in a wild-type rather than mouse-adapted backbone was protective against challenge in hamsters99 and partially protective in mice that transgenically express the human ACE2 molecule100. When the deletion of the envelope protein was engineered in the MA15 backbone, it elicited higher titres of neutralizing antibodies and was protective against challenge in aged mice101. This improvement in vaccine efficacy is probably facilitated by the ∼2 log-increased replication of mouse-adapted strains compared to wild-type virus in mice59.

All coronaviruses encode an exonuclease (ExoN) in the non-structural protein 14 (nsp14)-coding region of ORF1b. ExoN has been shown to mediate proofreading activity for the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase102. Inactivation of ExoN (ΔExoN) in SARS-CoV yields viable, replication-attenuated virus that accumulates mutations when passaged103. When generated in the MA15 background, the SARS-CoV MA-ΔExoN virus is attenuated for both growth and pathogenesis in young, aged and immunocompromised mice; it is fully protective against lethal challenge and elicits high levels of neutralizing antibodies, even at low vaccination doses71. Moreover, SARS-CoV MA-ΔExoN is stable in terms of both replication and resistance to reversion over short- and long-term passage. Its high resistance to reversion to virulence in vitro and in vivo might be due to the increased mutation frequency, which is likely to continuously introduce attenuating and/or neutral mutations that discourage and/or prohibit primary (at the site of the original mutation) and secondary (at sites other than the original mutation) reversion to virulence.

The particular advantage of approaches that involve conserved alleles, such as envelope and ExoN, aside from their effects on replication and efficacy in all mouse models tested, is that the conservation of the alleles makes them prime candidates for the rapid generation of new vaccines after the genome sequence of a novel emerging coronavirus (such as MERS-CoV) is known. Further work will focus on stabilizing the attenuated ΔExoN background and ensuring that it remains resistant to both primary and secondary reversion to virulence and recombination with virulent coronaviruses. For example, all coronaviruses possess a network of fairly well-conserved transcriptional regulatory sequences (TRSs) that are essential for the production of subgenomic mRNAs. Changing the TRS consensus yields viable viruses that have a reduced capacity to recombine with other coronaviruses — a method that shows great promise for rendering vaccine candidates refractory to recombination with naturally occurring (virulent) coronaviruses and for enhancing the safety of using genetically engineered coronaviruses as live vaccines104. With the recent development of MERS-CoV reverse genetic systems, these approaches can also be tested in the newest emergent coronavirus105,106.

Other vaccine approaches. Viral-vector vaccines, which function as viral gene delivery systems, rely on a host viral genome (for example, adenovirus) that typically lacks the genetic components necessary to produce new virions and that encodes antigenic components of the virus of interest to elicit an immune response. Because viral-vector vaccines persist in the host as genetic material, directly infect antigen-presenting cells and have strong inherent adjuvant activity, they can efficiently induce both innate and B cell- and T cell-mediated immune responses. Adenovirus vectors that express SARS-CoV spike and nucleocapsid proteins, which are the immunodominant coronavirus proteins, yield varying results depending on preparation, the route of administration and the animal model used; however, challenge experiments have not always been performed78,93. Although intramuscular vaccination induces high serum titres of neutralizing antibodies, intranasal inoculation more effectively prevents replication of the challenge virus, which suggests that the intranasal route is more efficient at inducing mucosal immunity94. In a side-by-side comparison with inactivated virus, an adenovirus-vectored vaccine produced significantly lower titres of neutralizing antibodies but was protective against subsequent challenge (although not as protective as inactivated virus)94. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEE) viral replicon particles (VRPs) have also been used to express SARS-CoV spike and nucleocapsid proteins. Spike-expressing VRP (VRP-S) vaccines protect against lethal homologous challenge in both young and aged BALB/c mice. When challenged with lethal virus that expresses the heterologous spike protein, only young mice are protected and only for a short time66,107,108. Other viral vectors that use the spike protein, including poxvirus109,110, parainfluenza virus111,112, rabies virus113 and vesicular stomatitis virus114, confirm the production of neutralizing antibodies, and some demonstrate protection. Conversely, vaccination with VRP constructs that express SARS-CoV nucleocapsid protein results in a TH2 cell-skewed immune response and immune pathology in the lungs, with no protection against homologous or heterologous challenge107.

Similarly to vectored vaccines, subunit vaccines only utilize antigenic components from the virus of interest; in contrast to vectored vaccines, the propagating organism is grown in the laboratory rather than in the vaccinee, and the antigenic component is harvested for use in the vaccine. SARS-CoV subunit vaccines contain either a spike protein fragment (which consists of amino acids 14–762) or the nucleocapsid protein. Because the crystal structures of both the SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV spike protein RBDs have been solved in complex with their corresponding receptors and their interacting residues have been mapped, these domains are the most obvious targets for subunit vaccine design36,115,116. Additionally, subunit spike vaccines can produce higher neutralizing antibody titres than live-attenuated SARS-CoV, poxvirus spike protein or DNA spike protein (DNA-S) vaccination117. Subunit nucleocapsid vaccines induce high levels of B cell- and T cell-mediated immune responses; however, in vivo challenge experiments have not yet been performed118,119.

DNA vaccines consist of DNA that encodes the viral antigenic components, and they are directly injected or otherwise inoculated into the vaccinee. As in vectored and subunit vaccines, DNA vaccines also use spike peptides to elicit high titres of neutralizing antibodies120,121. Interestingly, when DNA-S vaccines are used in combination with inactivated vaccines, the cellular immune response is TH1 cell-directed (whereas vaccination with inactivated virus alone induces a TH2 cell response)122. Similarly to viral nucleocapsid protein vectored vaccines, DNA vaccines that encode the nucleocapsid protein induce strong cell-mediated immunity but are not protective after high-titre challenge; additionally, and unlike spike protein vaccines, DNA-nucleocapsid (DNA-N) vaccines can induce delayed-type hypersensitivity, even in the absence of an antibody response119,123. Importantly, subunit and DNA vaccines have not been rigorously tested in either young or aged animals in lethal-challenge models, so their true in vivo efficacy is currently unknown.

Future directions

The emergence of SARS-CoV in 2002 taught us many lessons about zoonotic reservoirs, the importance of identifying animal models that recapitulate the various aspects of human disease and the determinants of vaccine efficacy and safety. This knowledge is being applied to the recent emergence of MERS-CoV in the human population. With its strikingly high morbidity and mortality rates in hospitalized individuals, it is clear that MERS-CoV has the potential have a profound impact on the human population. However, its low penetrance thus far suggests that the virus might ultimately fail to develop a niche in humans or it might still be adapting to human hosts and that the worst of its effects are yet to come. Studies with SARS-CoV suggest that MERS-CoV research should focus on establishing animal models that recapitulate replication, pathogenesis and transmission in humans. A priority is to develop treatments to prevent viral-induced immune pathology, particularly in the elderly. Furthermore, vaccines that target conserved alleles and provide broad protection against strains that are both closely and distantly related to the vaccine strain should be developed. One particular concern is the possibility that MERS-CoV vaccines can elicit TH2 cell immune pathology, as seen with inactivated, vectored and DNA SARS-CoV vaccines. Live-attenuated vaccines and vaccine combinations (for example, inactivated virus combined with DNA vaccines) do not seem to induce this immune phenomenon; thus, these approaches might hold more promise for the development of successful vaccination strategies, particularly in older populations. Adjuvants that promote more robust TH1 cell responses should also be evaluated in more rigorous models. A second concern is that for SARS-CoV escape from neutralization is driven by spike protein variability; thus, spike-dependent vaccine strategies might require multivalent approaches124. For MERS-CoV, the natural variation in the MERS-CoV spike glycoprotein is mostly unknown; thus, it is essential that more natural isolates are recovered and sequenced from humans and reservoir species. Focusing on these priorities will not only help to combat the emergence of MERS-CoV but will also increase our preparedness for any future coronavirus emergence events that originate from the vast, mutable zoonotic reservoir. As such, heterologous SARS-CoV- and MERS-CoV-related isolates that encode even minute variations in the spike protein will be important reagents for evaluating vaccine efficacy against future emerging strains.

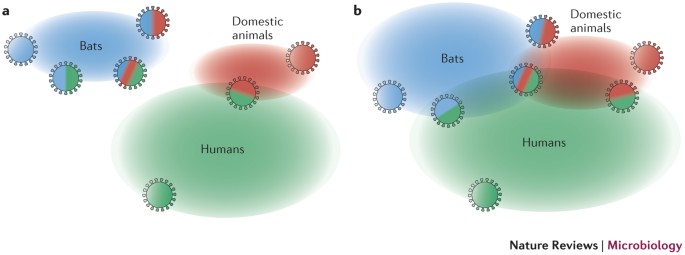

Coronavirus phylogeny demonstrates an incredible diversity in antigenic variants, which leads to limited cross-protection against infection with different strains, even within a phylogenetic subcluster. Consequently, the risk of introducing novel coronaviruses into naive human and animal populations remains high. Despite this antigenic breadth, it is revealing that alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses often use receptor orthologues and/or recognize carbohydrates for cross-species transmission. Given the large number of bat species and an ecology that enables potential pathogens to spread between bat populations, a number of bat coronaviruses might be naturally able to recognize human orthologue receptors for docking and entry. A recent study that analysed viral biodiversity in the flying fox Pteropus giganteus supports this hypothesis, as coronavirus species were among the several potentially novel viral species that were identified in PCR assays125. Moreover, the phylogeny of cornonaviruses that have appeared in the human population indicates an accelerating pattern of emergence and disease outbreaks from zoonotic sources. Molecular clock analyses have estimated the dates of the emergence of HCoV-NL63 (∼500–800 years ago)31, HCoV-229E (∼200–300 years ago)7, HCoV-OC43 (∼120 years ago)53, PEDV (∼30 years ago)126, respiratory bovine CoV (rBCoV) (∼20 years ago)127, SARS-CoV (∼10 years ago)22,85,128,129 and MERS-CoV (<1 year ago)16 (Fig. 2), which demonstrates a potential paradigm shift in the relationships that coronaviruses have with domesticated animals and human hosts. Bat coronaviruses have probably evolved to transmit in close proximity and with broader host tropism as a result of the large multispecies bat populations that exist across much of the globe. This pattern of transmission facilitates the spread of coronaviruses to other hosts; for example, intensive farm-management practices result in thousands of animals being housed together in a closed environment. Human population density has increased over the past 100 years, encroaching on wild animal habitats. In addition, the average age of the human population is increasing, and with it the proportion of immunocompromised individuals who are susceptible to severe lung infections. These conditions provide more vulnerable hosts for severe disease and, if animal models are representative of the process in humans, can lead to rapid in vivo evolution of virulence and transmissibility (Fig. 3). In fact, most early cases of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV have been described in the elderly and arose after close contact in hospital and family settings42,89. Emergence of virulence in the SARS-CoV background in older hosts could require fewer mutations and less passage than is required in young hosts57. Moreover, if close proximity is an important determinant for efficient coronavirus cross-species transmission and dissemination, it is possible that the current and projected ecological and demographic conditions are approaching a critical point. The Coronaviridae family is poised to excel in these conditions and colonize this growing niche. If these hypotheses are correct, accelerated transmission of bat and animal coronaviruses to humans can be expected to continue and possibly escalate. Public health authorities should prepare by developing broadly applicable platform strategies for the rapid diagnosis, containment and treatment of, and vaccination against, emerging coronavirus infections. We have been warned twice in recent years, and the belief that coronaviruses are highly vulnerable to public health intervention strategies is not supported by the increasing incidence of coronavirus emergence in livestock animal populations and the identification of novel coronaviruses in reservoir species, despite the application of widespread disease management practices and intervention strategies.

Figure 3: Changing viral ecology in expanding human and animal populations.

Alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses have historically been shown to have the capacity to utilize orthologous receptors and carbohydrates for entry in different species. Thus, in host pools (bats, blue; domestic animals, red; and humans, green), viruses that are capable of cross-species transmission might exist or be generated by the intrinsic error rate of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Bat populations that are largely separated from human and domestic animal populations result in limited viral emergence into new populations (part a). However, the expansion of human populations into previously unsettled areas, intensive domestic animal farm management practices that result in increased herd and flock sizes in small areas and in closer proximity to their human caretakers, and the encroachment of bats into human-populated regions contribute to the increased incidence of pathogenic human viruses from zoonotic pools (part b).

Note added in proof

The recent identification of bat SARS-like coronaviruses in Chinese horseshoe bats that are capable of using both the bat ACE2 and the human ACE2 receptor for entry[152](/articles/nrmicro3143#ref-CR152 "Ge, X.-Y. et al. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature12711

(2013).") strongly supports the argument that SARS-CoV emerged as a human infection directly from a bat reservoir. These data emphasize the importance of surveying synanthropic wildlife populations for potential zoonotic candidates.References

- Zhong, N. Management and prevention of SARS in China. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 359, 1115–1116 (2004).

Article Google Scholar - Peiris, J. S., Guan, Y. & Yuen, K. Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome. Nature Med. 10, S88–S97 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Cherry, J. D. The chronology of the 2002–2003 SARS mini pandemic. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 5, 262–269 (2004).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Anthony, S. J. et al. Coronaviruses in bats from Mexico. J. Gen. Virol. 94, 1028–1038 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Woo, P. C. et al. Discovery of seven novel mammalian and avian coronaviruses in the genus Deltacoronavirus supports bat coronaviruses as the gene source of Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus and avian coronaviruses as the gene source of Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus. J. Virol. 86, 3995–4008 (2012). This paper describes phylogenetic and molecular clock analyses that implicate bat coronaviruses as the forebearers of alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses, and thus all currently known human coronaviruses.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lau, S. K. et al. Recent transmission of a novel Alphacoronavirus, bat coronavirus HKU10, from Leschenault's rousettes to pomona leaf-nosed bats: first evidence of interspecies transmission of coronavirus between bats of different suborders. J. Virol. 86, 11906–11918 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Pfefferle, S. et al. Distant relatives of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and close relatives of human coronavirus 229E in bats, Ghana. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15, 1377–1384 (2009).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Chu, D. K., Peiris, J. S., Chen, H., Guan, Y. & Poon, L. L. Genomic characterizations of bat coronaviruses (1A, 1B and HKU8) and evidence for co-infections in Miniopterus bats. J. Gen. Virol. 89, 1282–1287 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Woo, P. C. et al. Molecular diversity of coronaviruses in bats. Virology 351, 180–187 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Tang, X. C. et al. Prevalence and genetic diversity of coronaviruses in bats from China. J. Virol. 80, 7481–7490 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lau, S. K. et al. Coronavirus HKU1 and other coronavirus infections in Hong Kong. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 2063–2071 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Li, W. et al. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science 310, 676–679 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lau, S. K. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 14040–14045 (2005). This is the first report of a SARS-related coronavirus in bats, and suggests that bats were a primary reservoir of the precursor to human SARS-CoV.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lu, L., Liu, Q., Du, L. & Jiang, S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): challenges in identifying its source and controlling its spread. Microbes Infect. 15, 625–629 (2013).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Annan, A. et al. Human betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012-related viruses in bats, Ghana and Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19, 456–459 (2013).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zaki, A. M., van Boheemen, S., Bestebroer, T. M., Osterhaus, A. D. & Fouchier, R. A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 1814–1820 (2012). This is the first description of the novel coronavirus that is responsible for severe respiratory illness in the Middle East. The virus was later named MERS-CoV.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - van Boheemen, S. et al. Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. mBio 3 e00473-12 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Chan, J. F. et al. Is the discovery of the novel human betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012 (HCoV-EMC) the beginning of another SARS-like pandemic? J. Infect. 65, 477–489 (2012).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Bolles, M. et al. A double-inactivated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus vaccine provides incomplete protection in mice and induces increased eosinophilic proinflammatory pulmonary response upon challenge. J. Virol. 85, 12201–12215 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Pyrc, K., Berkhout, B. & van der Hoek, L. Identification of new human coronaviruses. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 5, 245–253 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Reed, S. E. The behaviour of recent isolates of human respiratory coronavirus in vitro and in volunteers: evidence of heterogeneity among 229E-related strains. J. Med. Virol. 13, 179–192 (1984).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Peiris, J. S. et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 361, 1319–1325 (2003). This is one of three papers to describe the novel coronavirus that is responsible for SARS.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Shi, Z. & Hu, Z. A review of studies on animal reservoirs of the SARS coronavirus. Virus Res. 133, 74–87 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Li, W. et al. Animal origins of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus: insight from ACE2–S-protein interactions. J. Virol. 80, 4211–4219 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Guan, Y. et al. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China. Science 302, 276–278 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Woo, P. C. et al. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J. Virol. 79, 884–895 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - van der Hoek, L. et al. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nature Med. 10, 368–373 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Fouchier, R. A. et al. A previously undescribed coronavirus associated with respiratory disease in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 6212–6216 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Talbot, H. K. et al. Coronavirus infection and hospitalizations for acute respiratory illness in young children. J. Med. Virol. 81, 853–856 (2009).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wertheim, J. O., Chu, D. K., Peiris, J. S., Kosakovsky Pond, S. L. & Poon, L. L. A case for the ancient origin of coronaviruses. J. Virol. 87, 7039–7045 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Huynh, J. et al. Evidence supporting a zoonotic origin of human coronavirus strain NL63. J. Virol. 86, 12816–12825 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Memish, Z. A., Zumla, A. I., Al-Hakeem, R. F., Al-Rabeeah, A. A. & Stephens, G. M. Family cluster of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 2487–2494 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Assiri, A. et al. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 407–416 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Assiri, A. et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13, 752–761 (2013).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Reusken, C. B. et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: a comparative serological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13, 859–866 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wang, N. et al. Structure of MERS-CoV spike receptor-binding domain complexed with human receptor DPP4. Cell Res. 23, 986–993 (2013). This paper reports the crystal structure of the MERS-CoV spike RBD in complex with the human DPP4 receptor molecule and identifies the key spike–DPP4 interaction residues.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Raj, V. S. et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature 495, 251–254 (2013). This paper identifies DPP4 as the receptor for MERS-CoV.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Li, W. et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 426, 450–454 (2003). This paper identifies ACE2 as the receptor for SARS-CoV.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kindler, E. et al. Efficient replication of the novel human Betacoronavirus EMC on primary human epithelium highlights its zoonotic potential. MBio 4, e00611–00612 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Haagmans, B. L. et al. Pegylated interferon-α protects type 1 pneumocytes against SARS coronavirus infection in macaques. Nature Med. 10, 290–293 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Chow, K. C., Hsiao, C. H., Lin, T. Y., Chen, C. L. & Chiou, S. H. Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus in pneumocytes of the lung. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 121, 574–580 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Guery, B. et al. Clinical features and viral diagnosis of two cases of infection with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a report of nosocomial transmission. Lancet 381, 2265–2272 (2013).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Cotten, M. et al. Transmission and evolution of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia: a descriptive genomic study. Lancet http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61887-5 (2013).

- Kan, B. et al. Molecular evolution analysis and geographic investigation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in palm civets at an animal market and on farms. J. Virol. 79, 11892–11900 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Song, H. D. et al. Cross-host evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in palm civet and human. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 2430–2435 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yu, S. et al. Retrospective serological investigation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus antibodies in recruits from mainland China. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 12, 552–554 (2005).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zheng, B. J. et al. SARS-related virus predating SARS outbreak, Hong Kong. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10, 176–178 (2004).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Smith, I. & Wang, L. F. Bats and their virome: an important source of emerging viruses capable of infecting humans. Curr. Opin. Virol. 3, 84–91 (2013).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Wang, L. F. et al. Review of bats and SARS. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 1834–1840 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Plowright, R. K. et al. Urban habituation, ecological connectivity and epidemic dampening: the emergence of Hendra virus from flying foxes (Pteropus spp.). Proc. Biol. Sci. 278, 3703–3712 (2011).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Becker, M. M. et al. Synthetic recombinant bat SARS-like coronavirus is infectious in cultured cells and in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 19944–19949 (2008). This paper describes the reverse genetic design and recovery of bat SARS-related CoV with the epidemic and mouse-adapted SARS-CoV RBDs, including its capacity to infect mice and stimulate the production of cross-neutralizing antibodies.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Carrington, C. V. et al. Detection and phylogenetic analysis of group 1 coronaviruses in South American bats. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14, 1890–1893 (2008).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Vijgen, L. et al. Complete genomic sequence of human coronavirus OC43: molecular clock analysis suggests a relatively recent zoonotic coronavirus transmission event. J. Virol. 79, 1595–1604 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lau, S. K. et al. Genetic characterization of Betacoronavirus lineage C viruses in bats reveals marked sequence divergence in the spike protein of Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5 in Japanese Pipistrelle: implications for the origin of the novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. 87, 8638–8650 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Muller, M. A. et al. Human coronavirus EMC does not require the SARS-coronavirus receptor and maintains broad replicative capability in mammalian cell lines. MBio 3, e00515-12 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Munster, V. J., de Wit, E. & Feldmann, H. Pneumonia from human coronavirus in a macaque model. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 1560–1562 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Frieman, M. et al. Molecular determinants of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus pathogenesis and virulence in young and aged mouse models of human disease. J. Virol. 86, 884–897 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Day, C. W. et al. A new mouse-adapted strain of SARS-CoV as a lethal model for evaluating antiviral agents in vitro and in vivo. Virology 395, 210–222 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Roberts, A. et al. A mouse-adapted SARS-coronavirus causes disease and mortality in BALB/c mice. PLoS Pathog. 3, e5 (2007). This is the first description of an in vivo mouse-adapted variant of SARS-CoV that is capable of recapitulating the clinical features of severe human disease in aged BALB/c mice.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhao, J., Zhao, J., Legge, K. & Perlman, S. Age-related increases in PGD2 expression impair respiratory DC migration, resulting in diminished T cell responses upon respiratory virus infection in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 4921–4930 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhao, J., Zhao, J. & Perlman, S. T cell responses are required for protection from clinical disease and for virus clearance in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-infected mice. J. Virol. 84, 9318–9325 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhao, J., Zhao, J., Van Rooijen, N. & Perlman, S. Evasion by stealth: inefficient immune activation underlies poor T cell response and severe disease in SARS-CoV-infected mice. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000636 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Sheahan, T. et al. MyD88 is required for protection from lethal infection with a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV. PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000240 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Chen, W. et al. Antibody response and viraemia during the course of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-associated coronavirus infection. J. Med. Microbiol. 53, 435–438 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Li, C. K. et al. T cell responses to whole SARS coronavirus in humans. J. Immunol. 181, 5490–5500 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Roberts, A. et al. Aged BALB/c mice as a model for increased severity of severe acute respiratory syndrome in elderly humans. J. Virol. 79, 5833–5838 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Subbarao, K. et al. Prior infection and passive transfer of neutralizing antibody prevent replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in the respiratory tract of mice. J. Virol. 78, 3572–3577 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hogan, R. J. et al. Resolution of primary severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus infection requires Stat1. J. Virol. 78, 11416–11421 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Glass, W. G., Subbarao, K., Murphy, B. & Murphy, P. M. Mechanisms of host defense following severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV) pulmonary infection of mice. J. Immunol. 173, 4030–4039 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Frieman, M. B. et al. SARS-CoV pathogenesis is regulated by a STAT1 dependent but a type I, II and III interferon receptor independent mechanism. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000849 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Graham, R. L. et al. A live, impaired-fidelity coronavirus vaccine protects in an aged, immunocompromised mouse model of lethal disease. Nature Med. 18, 1820–1826 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Schaecher, S. R. et al. An immunosuppressed Syrian golden hamster model for SARS-CoV infection. Virology 380, 312–321 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Luo, D. et al. Protection from infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in a Chinese hamster model by equine neutralizing Fab′2. Viral Immunol. 20, 495–502 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Subbarao, K. & Roberts, A. Is there an ideal animal model for SARS? Trends Microbiol. 14, 299–303 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Roberts, A. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection of golden Syrian hamsters. J. Virol. 79, 503–511 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - ter Meulen, J. et al. Human monoclonal antibody as prophylaxis for SARS coronavirus infection in ferrets. Lancet 363, 2139–2141 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Martina, B. E. et al. Virology: SARS virus infection of cats and ferrets. Nature 425, 915 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Roper, R. L. & Rehm, K. E. SARS vaccines: where are we? Expert Rev. Vaccines 8, 887–898 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - See, R. H. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome vaccine efficacy in ferrets: whole killed virus and adenovirus-vectored vaccines. J. Gen. Virol. 89, 2136–2146 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Nagata, N. et al. Participation of both host and virus factors in induction of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in F344 rats infected with SARS coronavirus. J. Virol. 81, 1848–1857 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Fukushi, S. et al. Amino acid substitutions in the s2 region enhance severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infectivity in rat angiotensin-converting enzyme 2-expressing cells. J. Virol. 81, 10831–10834 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Rockx, B. et al. Comparative pathogenesis of three human and zoonotic SARS-CoV strains in cynomolgus macaques. PLoS ONE 6, e18558 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Greenough, T. C. et al. Pneumonitis and multi-organ system disease in common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) infected with the severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus. Am. J. Pathol. 167, 455–463 (2005).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - McAuliffe, J. et al. Replication of SARS coronavirus administered into the respiratory tract of African green, rhesus and cynomolgus monkeys. Virology 330, 8–15 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kuiken, T. et al. Newly discovered coronavirus as the primary cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 362, 263–270 (2003). This is one of three papers to describe the novel coronavirus that is responsible for SARS.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Smits, S. L. et al. Distinct severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-induced acute lung injury pathways in two different nonhuman primate species. J. Virol. 85, 4234–4245 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Falzarano, D. et al. Treatment with interferon-α2b and ribavirin improves outcome in MERS-CoV-infected rhesus macaques. Nature Med. 19, 1313–1317 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Adedeji, A. O. et al. Novel inhibitors of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus entry that act by three distinct mechanisms. J. Virol. 87, 8017–8028 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Breban, R., Riou, J. & Fontanet, A. Interhuman transmissibility of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: estimation of pandemic risk. Lancet 382, 694–699 (2013).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Qu, D. et al. Intranasal immunization with inactivated SARS-CoV (SARS-associated coronavirus) induced local and serum antibodies in mice. Vaccine 23, 924–931 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Takasuka, N. et al. A subcutaneously injected UV-inactivated SARS coronavirus vaccine elicits systemic humoral immunity in mice. Int. Immunol. 16, 1423–1430 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - He, Y., Zhou, Y., Siddiqui, P. & Jiang, S. Inactivated SARS-CoV vaccine elicits high titers of spike protein-specific antibodies that block receptor binding and virus entry. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 325, 445–452 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Enjuanes, L. et al. Vaccines to prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-induced disease. Virus Res. 133, 45–62 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - See, R. H. et al. Comparative evaluation of two severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) vaccine candidates in mice challenged with SARS coronavirus. J. Gen. Virol. 87, 641–650 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Tseng, C. T. et al. Immunization with SARS coronavirus vaccines leads to pulmonary immunopathology on challenge with the SARS virus. PLoS ONE 7, e35421 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ishioka, T. et al. Effects of respiratory syncytial virus infection and major basic protein derived from eosinophils in pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells (A549). Cell Biol. Int. 35, 467–474 (2011).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Lin, J. T. et al. Safety and immunogenicity from a phase I trial of inactivated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus vaccine. Antivir Ther. 12, 1107–1113 (2007).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Vignuzzi, M., Wendt, E. & Andino, R. Engineering attenuated virus vaccines by controlling replication fidelity. Nature Med. 14, 154–161 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - DeDiego, M. L. et al. A severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus that lacks the E gene is attenuated in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 81, 1701–1713 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Netland, J. et al. Immunization with an attenuated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus deleted in E protein protects against lethal respiratory disease. Virology 399, 120–128 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Fett, C., DeDiego, M. L., Regla-Nava, J. A., Enjuanes, L. & Perlman, S. Complete protection against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-mediated lethal respiratory disease in aged mice by immunization with a mouse-adapted virus lacking E protein. J. Virol. 87, 6551–6559 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Minskaia, E. et al. Discovery of an RNA virus 3′→5′ exoribonuclease that is critically involved in coronavirus RNA synthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 5108–5113 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Eckerle, L. D. et al. Infidelity of SARS-CoV Nsp14-exonuclease mutant virus replication is revealed by complete genome sequencing. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000896 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yount, B., Roberts, R. S., Lindesmith, L. & Baric, R. S. Rewiring the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) transcription circuit: engineering a recombination-resistant genome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 12546–12551 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Scobey, T. et al. Reverse genetics with a full-length infectious cDNA of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA (2013). This paper describes the design and implementation of an infectious cDNA clone of MERS-CoV.

- Almazan, F. et al. Engineering a replication-competent, propagation-defective middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus as a vaccine candidate. mBio 4, e00650-13 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Deming, D. et al. Vaccine efficacy in senescent mice challenged with recombinant SARS-CoV bearing epidemic and zoonotic spike variants. PLoS Med. 3, e525 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Baric, R. S. et al. SARS coronavirus vaccine development. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 581, 553–560 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Chen, Z. et al. Recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing the spike glycoprotein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus induces protective neutralizing antibodies primarily targeting the receptor binding region. J. Virol. 79, 2678–2688 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Bisht, H. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein expressed by attenuated vaccinia virus protectively immunizes mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 6641–6646 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Bukreyev, A. et al. Mucosal immunisation of African green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) with an attenuated parainfluenza virus expressing the SARS coronavirus spike protein for the prevention of SARS. Lancet 363, 2122–2127 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Buchholz, U. J. et al. Contributions of the structural proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus to protective immunity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 9804–9809 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Faber, M. et al. A single immunization with a rhabdovirus-based vector expressing severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) S protein results in the production of high levels of SARS-CoV-neutralizing antibodies. J. Gen. Virol. 86, 1435–1440 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kapadia, S. U. et al. Long-term protection from SARS coronavirus infection conferred by a single immunization with an attenuated VSV-based vaccine. Virology 340, 174–182 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Du, L. et al. Identification of a receptor-binding domain in the S protein of the novel human coronavirus Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus as an essential target for vaccine development. J. Virol. 87, 9939–9942 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Li, F., Li, W., Farzan, M. & Harrison, S. C. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science 309, 1864–1868 (2005). This paper reports the crystal structure of the SARS-CoV spike RBD in complex with the human ACE2 receptor molecule and identifies the key spike–ACE interaction residues.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Bisht, H., Roberts, A., Vogel, L., Subbarao, K. & Moss, B. Neutralizing antibody and protective immunity to SARS coronavirus infection of mice induced by a soluble recombinant polypeptide containing an N-terminal segment of the spike glycoprotein. Virology 334, 160–165 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Liu, S. J. et al. Immunological characterizations of the nucleocapsid protein based SARS vaccine candidates. Vaccine 24, 3100–3108 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Gupta, V. et al. SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid immunodominant T-cell epitope cluster is common to both exogenous recombinant and endogenous DNA-encoded immunogens. Virology 347, 127–139 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Woo, P. C. et al. SARS coronavirus spike polypeptide DNA vaccine priming with recombinant spike polypeptide from Escherichia coli as booster induces high titer of neutralizing antibody against SARS coronavirus. Vaccine 23, 4959–4968 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yang, Z. Y. et al. A DNA vaccine induces SARS coronavirus neutralization and protective immunity in mice. Nature 428, 561–564 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zakhartchouk, A. N., Liu, Q., Petric, M. & Babiuk, L. A. Augmentation of immune responses to SARS coronavirus by a combination of DNA and whole killed virus vaccines. Vaccine 23, 4385–4391 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhao, P. et al. Immune responses against SARS-coronavirus nucleocapsid protein induced by DNA vaccine. Virology 331, 128–135 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Rockx, B. et al. Escape from human monoclonal antibody neutralization affects in vitro and in vivo fitness of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Infect. Dis. 201, 946–955 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Anthony, S. J. et al. A strategy to estimate unknown viral diversity in mammals. mBio 4, e00598-13 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Pensaert, M. B. & de Bouck, P. A new coronavirus-like particle associated with diarrhea in swine. Arch. Virol. 58, 243–247 (1978).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Snodgrass, D. R. et al. Aetiology of diarrhoea in young calves. Vet. Rec. 119, 31–34 (1986).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ksiazek, T. G. et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1953–1966 (2003). This is one of three papers to describe the novel coronavirus that is responsible for SARS.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Drosten, C. et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1967–1976 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Narayanan, K., Huang, C. & Makino, S. SARS coronavirus accessory proteins. Virus Res. 133, 113–121 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Snijder, E. J. et al. Unique and conserved features of genome and proteome of SARS-coronavirus, an early split-off from the coronavirus group 2 lineage. J. Mol. Biol. 331, 991–1004 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hofmann, H. et al. Human coronavirus NL63 employs the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor for cellular entry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 7988–7993 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Perlman, S. & Netland, J. Coronaviruses post-SARS: update on replication and pathogenesis. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 7, 439–450 (2009).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Pacciarini, F. et al. Persistent replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in human tubular kidney cells selects for adaptive mutations in the membrane protein. J. Virol. 82, 5137–5144 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Vijgen, L. et al. Evolutionary history of the closely related group 2 coronaviruses: porcine hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus, bovine coronavirus, and human coronavirus OC43. J. Virol. 80, 7270–7274 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Louz, D., Bergmans, H. E., Loos, B. P. & Hoeben, R. C. Cross-species transfer of viruses: implications for the use of viral vectors in biomedical research, gene therapy and as live-virus vaccines. J. Gene Med. 7, 1263–1274 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Baric, R. S., Sullivan, E., Hensley, L., Yount, B. & Chen, W. Persistent infection promotes cross-species transmissibility of mouse hepatitis virus. J. Virol. 73, 638–649 (1999).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Glowacka, I. et al. Evidence that TMPRSS2 activates the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein for membrane fusion and reduces viral control by the humoral immune response. J. Virol. 85, 4122–4134 (2011).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Bertram, S. et al. Cleavage and activation of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein by human airway trypsin-like protease. J. Virol. 85, 13363–13372 (2011).