Bacteria–autophagy interplay: a battle for survival (original) (raw)

- Review Article

- Published: 02 January 2014

Nature Reviews Microbiology volume 12, pages 101–114 (2014)Cite this article

- 25k Accesses

- 438 Citations

- 1 Altmetric

- Metrics details

Subjects

Key Points

- Autophagy is used by the cell to degrade various substrates; this is achieved either through the canonical, non-selective autophagy pathway or through selective autophagy. Both pathways proceed via distinct key steps and use specific molecular mechanisms.

- The canonical autophagy pathway has been studied in detail in mammalian cells and in model organisms, such as yeast. The molecular mechanisms underlying non-canonical autophagy, in addition to alternative pathways that are independent of some of the key autophagy machinery, are beginning to become clear.

- Besides degradation of cellular proteins, autophagy proteins are also involved in many other functions, some of which are important during bacterial infections.

- Autophagy functions as an antibacterial mechanism. The induction and recognition mechanisms for several bacterial species have been elucidated.

- Bacteria can escape killing by autophagy and some can even use autophagy to promote infection of host cells, through the interaction between bacterial effector proteins and autophagy components.

- The knowledge about bacteria–autophagy interactions will inform the design of new drugs and treatments against bacterial infections.

Abstract

Autophagy is a cellular process that targets proteins, lipids and organelles to lysosomes for degradation, but it has also been shown to combat infection with various pathogenic bacteria. In turn, bacteria have developed diverse strategies to avoid autophagy by interfering with autophagy signalling or the autophagy machinery and, in some cases, they even exploit autophagy for their growth. In this Review, we discuss canonical and non-canonical autophagy pathways and our current knowledge of antibacterial autophagy, with a focus on the interplay between bacterial factors and autophagy components.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) is a cellular pathway that delivers cytoplasmic proteins and organelles to the lysosome for degradation. It occurs at a basal level in nutrient-rich conditions but can be upregulated in response to various stress conditions, such as starvation. Autophagy can be non-selective (that is, a portion of the cytoplasm is engulfed, for example, in response to amino acid deprivation) or selective. Selective autophagy targets various cargoes for degradation; this includes organelle-specific autophagy (including mitophagy, pexophagy and reticulophagy) and xenophagy (which is the degradation of microorganisms)1.

Autophagy has also emerged as an innate immune response pathway, targeting intracellular bacteria in the cytosol, in damaged vacuoles and in phagosomes to restrict bacterial growth. Autophagy can be induced on bacterial infection and involves the formation of double-membrane compartments (known as autophagosomes) around target bacteria and their transport to lysosomes for degradation2. Extensive work has been done to determine the induction and targeting mechanisms of antibacterial autophagy. It is now thought that multiple host factors and pathways are activated and contribute to this process.

Increasing evidence also suggests that bacteria have evolved strategies to combat autophagy3. Recent studies have indicated the existence of active interactions between bacterial factors and host autophagy components. Certain bacteria can inhibit the signalling pathways that lead to autophagy induction4,5, mask themselves with host proteins to avoid autophagy recognition6,7,8, interfere with the autophagy machinery to escape targeting9,10 or block fusion of the autophagosome with the lysosome11. Some bacteria even actively exploit autophagy components to promote their own intracellular growth12,13. The mechanisms by which bacteria interfere with autophagy remain mostly unclear and are currently the subject of intense investigation.

In this Review, we provide an overview of the mechanisms of canonical and non-canonical autophagy and then focus on the interplay between bacteria and autophagy, including how autophagy targets bacteria for clearance and how bacteria block this process or hijack it for survival.

Mechanisms of autophagy

The hallmark of autophagy is the formation of the double-membrane autophagosome, which captures and transports cytoplasmic components to the lysosome for degradation. In mammalian cells and yeast, autophagosomes are initiated at the phagophore assembly site (PAS)[14](/articles/nrmicro3160#ref-CR14 "Parzych, K. R. & Klionsky, D. J. An overview of autophagy: morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/ars.2013.5371

(2013)."); an example of a PAS in mammals is the omegasome, a phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PtdIns3P)-enriched subdomain of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)[15](/articles/nrmicro3160#ref-CR15 "Axe, E. L. et al. Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 182, 685–701 (2008)."). A group of autophagy-related (ATG) proteins are the key players in autophagy, although some also have non-autophagy functions ([Table 1](/articles/nrmicro3160#Tab1)).Table 1 Non-canonical functions of autophagy proteins

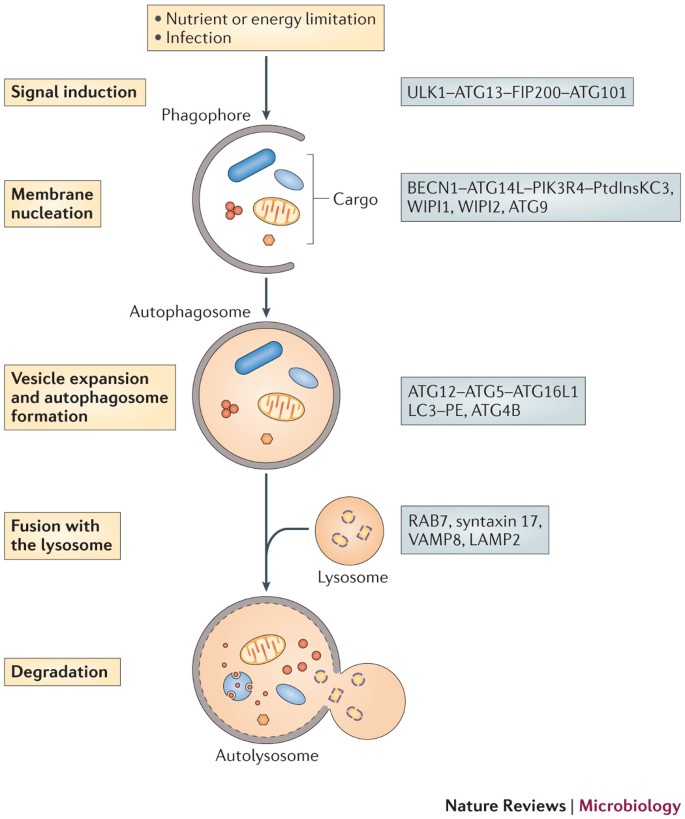

Canonical and selective autophagy. Autophagy can be dissected into the following steps: signal induction, membrane nucleation, cargo targeting, vesicle expansion and autophagosome formation, fusion with the lysosome, cargo degradation and nutrient recycling[14](/articles/nrmicro3160#ref-CR14 "Parzych, K. R. & Klionsky, D. J. An overview of autophagy: morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/ars.2013.5371

(2013).") ([Fig. 1](/articles/nrmicro3160#Fig1)).Figure 1: A diagram of the autophagy pathway.

On stimulation of autophagy, a small membrane sac, known as the phagophore, is assembled and starts to elongate to enclose cytoplasmic components. The phagophore expands and grows into a double-membrane compartment, known as the autophagosome, which sequesters cytoplasmic targets, such as proteins, organelles and microorganisms. The autophagosome fuses with the lysosome to generate the autolysosome, in which the cargo is degraded by hydrolytic enzymes. Key proteins involved in autophagy in mammals are shown on the right. ATG, autophagy-related; ATG14L, ATG14-like; ATG16L1, ATG16-like 1; BECN1, beclin 1; FIP200, FAK family kinase-interacting protein of 200 kDa; LAMP2, lysosomal-associated membrane glycoprotein 2; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PIK3R4, phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulatory subunit 4; PtdInsKC3, phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase class III; ULK1, Unc-51-like kinase; VAMP8, vesicle-associated membrane protein 8; WIPI, WD-repeat domain phosphoinositide-interacting.

Induction can be triggered by a range of signals, from nutrient limitation (in the case of non-selective autophagy) to the recognition of specific cargo, such as damaged mitochondria or bacteria16. The Unc-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1; known as Atg1 in yeast) complex (which comprises ULK1, ATG13, FAK family kinase-interacting protein of 200 kDa (FIP200) and ATG101 (also known as C12orf44)) is the signal initiation complex and has a key role in recruiting ATG proteins to the PAS17. In the presence of nutrients, the ULK1 complex is inhibited by mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1; which promotes growth in nutrient-rich conditions)17. mTORC1 phosphorylates ULK1 and ATG13, thus inhibiting the recruitment of the ULK1 complex to the PAS18,19. By contrast, when mTORC1 is inactive (during nutrient limitation or rapamycin treatment), ULK1 is released18,19, which enables it to phosphorylate FIP200, translocate to the PAS and recruit other ATG proteins to initiate autophagosome formation18,19,20. The ULK1 complex is also essential for initiation during selective autophagy, although, in most cases, it is unclear whether ULK1 recruitment is regulated by mTORC1 or by other signalling molecules. For example, in yeast, Atg1 is required for pexophagy21, mitophagy22 and the cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting pathway (Cvt pathway)23, and in mammals FIP200 is crucial for the autophagic degradation of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium24.

The ULK1 complex recruits beclin 1 (BECN1; Atg6 in yeast), ATG14-like (ATG14L) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulatory subunit 4 (PIK3R4; vacuolar protein sorting-associated 15 (Vps15) in yeast) to the PAS, where they are involved in the phagophore membrane nucleation step. This is achieved by engaging PtdIns3-kinase class III (PtdIns3KC3; Vps34 in yeast), resulting in the production of PtdIns3P at the phagophore. This leads to the recruitment of PtdIns3P-binding proteins, such as WD-repeat domain phosphoinositide-interacting 1 (WIPI1; Atg18 in yeast) and WIPI2 (Atg21 in yeast) to the PAS to aid phagophore assembly by, at least in yeast, recruiting downstream Atg proteins (Atg16 and Atg8; see below)25,26. ATG9 is also important for phagophore assembly. In yeast, Atg9 exits from the _trans_-Golgi network (TGN) and associates with small vesicles27,28, some of which contribute membranes, at least partially, for phagophore biogenesis27,28. In mammals, ATG9 localizes at the TGN and on endosomes, transiently interacts with omegasomes and is required for PAS formation and expansion29,30. However, ATG9 is not incorporated into the PAS.

Autophagosome elongation is mediated by two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems. The ATG12–ATG5 ubiquitin-like-conjugate, which is activated by the E1-like enzyme ATG7 and the E2-like enzyme ATG10, promotes phagophore elongation31,32. In addition, ATG12–ATG5 forms a complex with ATG16L1, which associates with the expanding phagophore membrane33 but is released from the autophagosome membrane when the vesicle is complete32. The fusion of ATG16L1- associated precursor vesicles with each other is mediated by SNARE proteins and possibly contributes to the phagophore expansion process34. ATG12–ATG5 is necessary for the formation of the second ubiquitin-like conjugate, light chain 3 (LC3; also known as MAP1LC3B; Atg8 in yeast)–phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), which is activated by the E1-like enzyme ATG7 and the E2-like enzyme ATG3. The ATG12–ATG5–ATG16L1 complex directs LC3 to the target membrane35, where it becomes conjugated to PE by the E3-like enzyme activity of ATG12–ATG5 (Ref. 36). The cysteine protease ATG4B is also required for LC3–PE formation, as it cleaves the carboxyl terminus of LC3 and exposes a glycine residue that is then covalently attached to PE37. In addition, ATG4B deconjugates a proportion of the LC3–PE complexes when autophagosome formation is complete, thus facilitating the recycling of LC3 for the formation of new autophagosomes37,38. Recent studies in yeast indicate that this deconjugation process is necessary for efficient autophagosome biogenesis as well as for maturation of the autophagosome into a fusion-capable autophagosome38,39. LC3 has been shown to mediate the hemifusion of vesicles and to control the size of the autophagosome in yeast40,41.

Eventually, autophagosomes mature into degradative autolysosomes by a series of fusion events with endosomes and lysosomes. In mammals, the fusion of an autophagosome with a lysosome requires the small GTPase RAB7 (Ypt7 in yeast)42, the autophagosomal SNARE protein syntaxin 17 (Ref. 43) and the lysosomal SNARE vesicle-associated membrane protein 8 (VAMP8), as well as lysosomal membrane proteins, such as lysosomal-associated membrane glycoprotein 2 (LAMP2)44,45. In yeast, the vesicle SNARE (v-SNARE) proteins vacuolar morphogenesis protein 7 (Vam7) and Ykt6, the target SNARE (t-SNARE) proteins Vam3 and Vti1, the GTPase Ypt7, the Ypt7 guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) monensin sensitivity 1–calcium-caffeine-zinc sensitivity 1 (Mon1–Ccz1) and homotypic vacuole fusion and vacuole protein sorting (HOPS) proteins46 are all required for autophagosome fusion with the vacuole (which is the yeast counterpart of the lysosome). Lysosomal breakdown of the inner autophagosomal membrane and the autophagosome cargo is mediated by lysosomal hydrolases.

Selective autophagy has an additional step — cargo selection — which is mediated by cargo receptors and adaptor proteins. In mammalian cells, cargo-specific receptors usually contain an LC3-interacting region (LIR) that mediates the recruitment of LC3-decorated autophagosomes to the cargo (for example, mitochondria)47,48,49. Moreover, ubiquitin-associated cargoes are recognized by ubiquitin-binding protein adaptors, which also contain LIRs50. One example is p62, which links various cargo targets, including ubiquitylated protein aggregates51,52, ubiquitin-tagged peroxisomes53 and bacteria8,54,55, to autophagosomes. Other adaptor proteins that have both a ubiquitin-binding domain and an LIR have also been discovered, including NBR1 (next to BRCA1 gene 1)56, NDP52 (nuclear dot protein 52 kDa; also known as CALCOCO2)57 and optineurin58. NBR1 is involved in the targeting of protein aggregates56, peroxisomes59 and the bacterial pathogen Francisella tularensis60 for autophagy; NDP52 and optineurin, together with p62, are involved in the autophagy of S. Typhimurium55,57,58.

Alternative (non-canonical) autophagy. Recent studies have identified alternative autophagy pathways that are independent of some of the core machinery components; these are known as non-canonical forms of autophagy. For example, autophagy that is independent of ULK1 and ULK2 has been observed after long-term glucose starvation61. Moreover, a recent study found that autophagy can occur in _Atg5_-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts62. ATG5-independent autophagy, which contributes to organelle clearance during erythrocyte maturation, depends on the ULK1 complex and BECN1 but does not require LC3–PE and several other essential conventional autophagy components, including ATG7, ATG12, ATG16L1 and ATG9. BECN1-independent autophagy has also been identified in cancer cell lines, in which it is induced by apoptotic stimuli, such as staurosporine63, and by the antioxidant resveratrol64, as well as in non-tumour cell lines, in which it is induced by the neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium65 and by the recombinant viral capsid protein VP1 of foot-and-mouth disease virus66, among others. BECN1-independent autophagy involves the formation of double-membrane autophagosomes and requires the ULK1 complex, ATG5, ATG7 and LC3–PE conjugation systems, but the exact mechanism remains unclear63,64,67.

A recent study identified a non-canonical form of autophagy in which the autophagosome was derived from the late endosome — a process known as endosome-mediated autophagy (ENMA)68. ENMA is induced by the Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligand lipopolysaccharide in dendritic cells, which contain late endosomes known as major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-containing compartments (MIICs). Typical MIIC marker proteins and autophagy proteins, including LC3 and ATG16L1, were associated with these MIIC-derived autophagosomes. Notably, ENMA was independent of ATG4B and LC3 conjugation to PE, as the MIIC-derived autophagosomes were formed in _Atg4b_-knockout dendritic cells.

During TLR- or Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis in professional phagocytic cells, autophagy components, including LC3, BECN1, PtdIns3KC3 and ATG12–ATG5, are translocated to the phagosomal membrane to promote phagosome fusion with the lysosome69,70. This process does not involve the formation of a double- membrane autophagosome and has been termed LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP). Induction of LAP is independent of the ULK1 complex71 but requires the activity of NADPH oxidase and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS)70. NADPH oxidase is activated and assembled on the phagosomal membrane during the phagocytosis of microorganisms and generates ROS in the phagosomal lumen to directly kill them. How ROS induce the recruitment of LC3 to the phagosome, and how autophagy components facilitate lysosomal fusion, remains unknown. Notably, LAP is thought to restrict the growth of bacterial pathogens, such as S. Typhimurium70 and Burkholderia pseudomallei72, in host cells.

Autophagy as an antibacterial defence

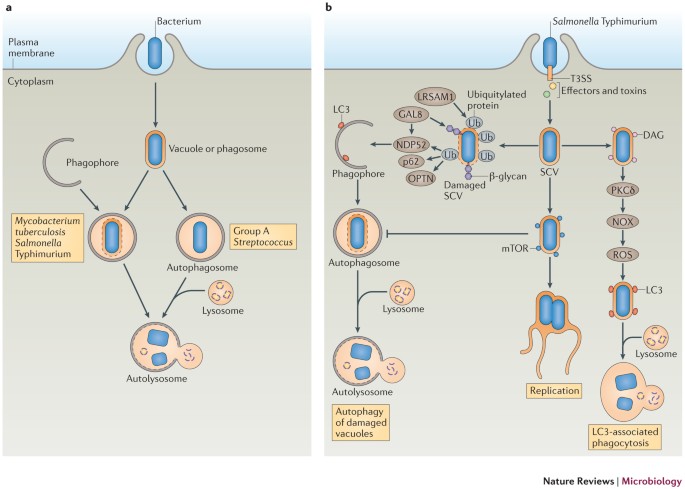

As mentioned above, bacteria have been identified as targets of selective autophagy, and this process is known as xenophagy. In this context, autophagy acts as an innate immune mechanism against bacterial infection. Autophagy can target intracellular bacteria either in the cytosol or in vacuoles to restrict their growth (Fig. 2a). In most cases, LC3-decorated autophagosomes are formed around the target bacteria2 and deliver them into the lysosome for degradation.

Figure 2: Autophagy is an antibacterial mechanism.

a | Schematic diagram of the ways that autophagy targets intracellular bacteria. After invasion of host cells, the bacterium resides in a bacterium-containing vacuole (or phagosome). Some bacteria damage the vacuolar or phagosomal membrane and eventually escape into the cytosol. Autophagy can target bacteria in damaged vacuoles or phagosomes (as with, for example, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium) or in the cytosol (as with, for example, Group A Streptococcus) and deliver them to the lysosome for degradation. b | Model of the antibacterial autophagy of S. Typhimurium. The bacterium resides in a _Salmonella_-containing vacuole (SCV) after invading epithelial cells. Early after infection (∼1 hour), the membrane of a subset of SCVs is damaged and the bacterium is exposed to the cytoplasm, where it becomes associated with ubiquitylated proteins in a process that depends on the E3 ubiquitin ligase leucine-rich repeat and sterile α-motif-containing 1 (LRSAM1). Next, adaptor proteins, including p62, NDP52 (nuclear dot protein 52 kDa) and optineurin (OPTN) are recruited to the SCV by binding to ubiquitin, and they recruit autophagosomes by interacting with microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3), ultimately resulting in autolysosome formation. The damaged SCV membrane also exposes β-glycans to the cytoplasm and recruits galectin 8 (GAL8), which binds to NDP52 and further recruits LC3. Also at ∼1 hour post-infection, a subset of bacteria recruits diacylglycerol (DAG) to the undamaged SCVs. DAG activates protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ), which activates NADPH oxidase (NOX) and promotes reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, in turn inducing LC3-associated phagocytosis of bacteria. At ∼4 hours post-infection, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is redistributed to the SCV membrane, which inhibits autophagy induction, resulting in autophagy escape and enabling bacteria to replicate in SCVs. T3SS, type III secretion system.

Autophagy targeting S. Typhimurium. One well-studied example of a bacterium that is targeted for autophagy is S. Typhimurium (Fig. 2b). Autophagy is essential for restricting the growth of this bacterium in Caenorhabditis elegans and Dictyostelium discoideum73. S. Typhimurium uses its two type III secretion systems (T3SSs; encoded by Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) and SPI-2) to invade epithelial cells, and typically resides in the _Salmonella_-containing vacuole (SCV)74. However, a subset of bacteria damages the SCV membrane early after infection, via SPI-1 T3SS pore-forming activities on the vacuolar membrane, and can potentially escape into the cytosol to obtain nutrients for rapid growth75. Some of the cytosol-exposed bacteria are targeted by autophagy within damaged SCVs, as shown by the recruitment of LC3 and other ATG proteins to the bacteria. As a consequence, autophagy protects the cytosol from bacterial colonization76.

How S. Typhimurium is selectively targeted to autophagosomes has been the subject of many studies. Evidence suggests that SCV membrane damage exposes specific signature molecules either on the bacterial surface or on the inner face of the SCV membrane, and in turn, these molecules recruit adaptor proteins from the cytosol that then recruit autophagy components to the SCV (Fig. 2b). For example, it has been shown that a population of bacteria is associated with ubiquitylated proteins shortly after invasion, indicating exposure to the cytosol76. These ubiquitin-positive bacteria also colocalize with adaptor protein p62 (see above) and LC3 (Ref. 55), which suggests that p62 links the bacteria to autophagosomes via LC3. The adaptor protein optineurin58 also has a role in bacterial autophagy: phosphorylation of optineurin by the innate immune receptor TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1; which activates the transcription of type I interferons (IFNs)) strengthens its interaction with LC3, which restricts the intracellular growth of S. Typhimurium58. Recently, a host ubiquitin E3 ligase, leucine-rich repeat and sterile α-motif-containing 1 (LRSAM1), was found to have a role in the ubiquitylation of proteins that are associated with the autophagy of S. Typhimurium77, but the ubiquitylated host and bacterial proteins that are involved are unknown.

Other host molecules are also thought to participate in the autophagic targeting of bacteria and to interact with autophagy adaptor proteins. Specifically, SCV membrane damage exposes the host cell sugar molecule β-galactoside — which normally localizes to the plasma membrane surface and luminal face of endosomes, including SCV membranes — to the cytosol. This β-galactoside is recognized by its cytosolic receptor, galectin 8, which binds NDP52 and thus recruits LC3 to the damaged SCV78. Remarkably, it is the recruitment of NDP52 to bacteria through galectin 8 binding, not ubiquitin binding, that is required for NDP52-mediated autophagy of S. Typhimurium.

Therefore, both ubiquitin and sugar signals contribute to the autophagy of bacteria in damaged vacuoles. The existence of three adaptor-mediated pathways (p62, optineurin and NDP52) might guarantee the maximal targeting of cytosol-exposed bacteria, although the order of activation of each pathway is not entirely clear at the moment. The peak of LC3 association with S. Typhimurium is at 1 hour post-infection, a time at which both ubiquitin and galectin 8 have been recruited to the bacteria76,78. It is possible that ubiquitin recruits p62 and optineurin to the bacteria at the same time and that galectin 8 recruits NDP52 in parallel. More precise kinetic and microscopic studies are needed to resolve the order of translocation of ubiquitin and galectin 8 to the bacteria at the early stages of infection.

Other core machinery autophagy components, such as ULK1, FIP200, ATG14L, ATG16L1 and ATG9, are also targeted to the SCV, and each of them has a role in restricting the intracellular growth of S. Typhimurium24. However, targeting of LC3 to the SCV is independent of the essential autophagy factors (the ULK1 complex, the BECN1 complex and ATG9). Therefore, LC3 can be recruited to SCVs by at least one other, non-canonical pathway. Indeed, S. Typhimurium is also targeted by the LAP pathway. It has been shown that NADPH oxidase and ROS are necessary for efficient recruitment of LC3 to bacteria70. In addition, the lipid signalling molecule diacylglycerol (DAG) is recruited to SCVs, and its production is necessary for efficient LC3 recruitment to bacteria79. In fact, DAG-positive bacteria are not associated with ubiquitin or p62, and inhibiting both DAG and p62 leads to an additive inhibitory effect on LC3 recruitment to the bacteria. These results suggest that the DAG pathway and the ubiquitin-adaptor pathway contribute independently to the recruitment of LC3 to S. Typhimurium. The downstream effector of DAG, protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ), is also required for LC3 recruitment to bacteria79. PKCδ can activate NADPH oxidase by phosphorylation of one of its components80, which suggests that DAG-dependent LC3 targeting of bacteria involves the PKCδ–NADPH oxidase–ROS pathway. It remains unknown what triggers the translocation of DAG to the SCVs. The SPI-1 T3SS of S. Typhimurium is required for DAG localization on the SCVs, suggesting that either bacterial effectors or the membrane damage caused by T3SS pore-forming activity is involved. Whether LAP occurs before canonical autophagy targets S. Typhimurium is not clear. ROS production is very rapid after bacterial invasion (peaking at ∼10 min post-infection)81, and association of DAG with S. Typhimurium peaks at 30 min post-infection79. It has also been suggested that ROS might contribute to damaging SCV membranes. Therefore, activation of LAP signalling might occur slightly earlier than activation of the ubiquitin–adaptor–autophagy pathway. Correlative electron microscopy studies are needed to distinguish LAP from the canonical autophagy pathway.

Other bacteria targeted by autophagy. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is another example of a bacterium that is targeted for autophagy in damaged vacuoles (Fig. 2a). During infection of macrophages, M. tuberculosis blocks phagosome maturation and replicates in the phagosome. A recent study showed that ∼30% of phagosomal mycobacteria were selectively targeted by LC3 and ATG12 by 4 hours post-infection82. The membrane-permeabilization factor early secreted antigenic target of 6 kDa (ESAT-6; also known as EsxA), which is the major substrate secreted from the bacterial type VII secretion system ESX-1, is required for the targeting of M. tuberculosis for autophagy. Autophagy is thought to be triggered following damage to the _M. tuberculosis_-containing phagosomes, with ubiquitylation of host and bacterial proteins having a major role. Ubiquitin-associated bacteria colocalize with p62, NDP52 and LC3, which suggests that phagosomal damage triggers bacterial targeting by LC3 and adaptor proteins, and thus allows targeting of the bacteria by selective autophagy82. The same study found that naked bacterial DNA in the host cytosol can function as the signal that triggers autophagy, possibly through the activation of TBK1 and STING, both of which are necessary for ubiquitin-mediated selective autophagy of M. tuberculosis83. The ubiquitin E3 ligase Parkin was recently implicated in autophagy of these bacteria84.

Autophagy also selectively targets cytosolic bacteria, such as Group A Streptococcus (GAS)85. When actively invading HeLa cells, GAS escapes from the endosomes to the cytoplasm, in a process that is mediated by the toxin streptolysin O (SLO), a member of a family of cholesterol-dependent pore-forming cytolysins86. Most cytosolic bacteria are enveloped in LC3-decorated, GAS-containing autophagosome-like vacuoles (GcAVs) and are degraded through autophagy85 (Fig. 2a). GcAV formation and bacterial clearance are severely impaired in _Atg5_-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts compared with wild-type cells, in which most bacteria are killed during the first 4 hours post-infection. Moreover, SLO is necessary for autophagic targeting of the bacteria, as SLO-deficient mutants are not sequestered in LC3-positive autophagic structures and survive longer than wild-type bacteria85,86. Notably, SLO-deficient mutants remain in endosomes and cannot escape to the cytosol of HeLa cells, so bacterial exposure to the cytosol may function as the signal for antibacterial autophagy. Engagement of the human cell surface pathogen receptor CD46 has also been shown to induce autophagy clearance of GAS by activating BECN1 and PtdIns3KC3 (Ref. 87).

In addition to ATG proteins, members of the RAB GTPase family localize to GcAVs and are involved in their formation. For example, RAB7, which mediates late endosome maturation, and RAB23, which regulates intracellular vesicle transport, were found to be necessary for the formation of GcAVs86,88. RAB9A, which mediates protein transport from late endosomes to the TGN, is required for GcAV enlargement and fusion with the lysosomes88. RAB9A and RAB23 are not involved in starvation-induced canonical autophagosome formation88, which suggests that they have unique roles in selective bacterial autophagy.

Another study showed that, in human oropharyngeal keratinocytes, GAS uses both SLO (which is required for the association with ubiquitin) and the pore-forming cytolysin streptolysin S (SLS; which is required for the association with galectin 8) to damage the vacuolar membrane, resulting in its association with ubiquitin or galectin 8 and consequent targeting by autophagy adaptor proteins89. However, in this study, SLO was shown to promote bacterial survival in human oropharyngeal keratinocytes. Together with NAD glycohydrolase, a toxin that is encoded in the same operon, SLO inhibits the fusion of GcAVs with lysosomes89. Thus, in human oropharyngeal keratinocytes, GAS infection induces the xenophagic response, but bacterial toxins inhibit the formation of mature autolysosomes and enable bacterial survival. This is a more complex interaction between bacteria and autophagy than that seen in HeLa cells, in which autophagy kills most bacteria during early infection85.

Manipulating autophagy

Although some bacteria are targeted and eliminated by autophagy, others have developed ways to escape this defence system or even hijack the autophagy machinery to promote their intracellular growth (Fig. 3; Table 2). In addition to the examples that are discussed below, other bacteria, such as F. tularensis, Yersinia enterocolitica and Orientia tsutsugamushi have been reported to escape autophagy, but the bacterial and host factors that are involved have not been fully elucidated60,90,91,92,93.

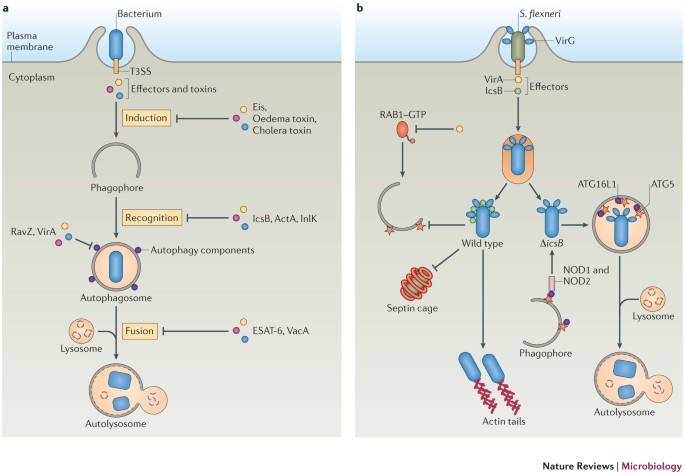

Figure 3: Bacteria manipulate autophagy for survival.

a | A diagram of how bacteria interfere with the autophagy machinery. Bacteria actively invade mammalian cells and secrete effectors to modulate the host cell machinery. Some bacteria use their effectors or toxins to interfere with the autophagy machinery at various stages in order to escape autophagic killing. Methods include inhibiting the autophagy induction signal (as with Eis (enhanced intracellular survival) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, oedema factor toxin from Bacillus anthracis and cholera toxin from Vibrio cholerae), inhibiting recognition by the autophagy machinery (as with IcsB from Shigella flexneri, and ActA and internalin K (InlK) from Listeria monocytogenes), directly interfering with autophagy components (as with RavZ from Legionella pneumophila and VirA from S . flexneri) or blocking autophagosome fusion with the lysosome (as with ESAT-6 (early secreted antigenic target of 6 kDa) from M . tuberculosis and VacA from Helicobacter pylori). b | Model of S. flexneri evasion of autophagy. Wild-type bacteria escape the phagosomal compartment into the cytosol, where they recruit actin tails and replicate. The secreted effector IcsB binds to the bacterial surface protein VirG to block autophagy-related 5 (ATG5). IcsB also prevents formation of septin cages around the bacteria. The effector protein VirA inactivates RAB1 GTPase through its GTPase-activating protein (GAP) activity and inhibits autophagy. Δ_icsB_-mutant bacteria are recognized by nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing 1 (NOD1) and NOD2, which interact with ATG16-like 1 (ATG16L1) and recruit autophagosomes to the invaded bacteria. In addition, ATG5 binds VirG and targets bacteria to autophagosomes. T3SS, type 3 secretion system.

Table 2 Factors involved in the bacterium–autophagy interplay

Inhibition of autophagy-initiation signalling. Some bacteria have developed strategies to inhibit the signalling cascade that initiates autophagy. For example, it has been shown that, early after S. Typhimurium infection (1 hour post-infection), membrane damage triggers a transient cytosolic amino acid starvation response, as shown by the activation of the amino acid sensor GCN2 (a kinase that phosphorylates the translation initiation factor eukaryotic initiation factor-2α (eIF2α), which controls protein synthesis)5. This acute amino acid starvation inhibits mTORC1 activity and relocalizes mTOR (which is a part of mTORC1) from the late endosome to the cytosol5, thus activating autophagy signalling. However, by 4 hours post-infection, the cytosolic amino acid pool is restored and mTOR is reactivated; mTOR then relocalizes to late endosomes and SCVs, thus inhibiting autophagy targeting towards S. Typhimurium (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, inactivation of mTORC1 by rapamycin treatment resulted in an association of ∼50% of bacteria with LC3 at 4 hours post-infection, which suggests that S. Typhimurium escapes autophagy targeting at this time point by promoting mTORC1 activation. Although it remains unclear how this is achieved, it has been shown that SPI-2 T3SS is upregulated 4 hours after infection94, and SPI-2 T3SS, or its secreted effectors, might have a role in the relocalization of mTORC1 regulators to the SCVs.

Another example of a bacterium that has evolved to avoid autophagy is M. tuberculosis str. H37Rv. In this bacterial strain, deletion of the gene encoding Eis (enhanced intracellular survival) induces the formation of autophagosomes following the infection of bone marrow-derived macrophages, which suggests that Eis can inhibit autophagy activation during infection by wild-type bacteria95. Further analysis revealed that this is achieved by interfering with JUN N-terminal kinase (JNK) signalling, thus blocking the production of ROS (which are required for autophagy triggering): Eis-mutant bacteria were found to activate JNK and to consequently promote the production of ROS95. Eis is an _N_-acetyltransferase that acetylates and activates a JNK-specific phosphatase, mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 7, which inhibits JNK phosphorylation and leads to its inactivation96.

In addition, bacterial toxins have been shown to inhibit autophagy induction by modulating the levels of cyclic AMP, a second messenger that regulates many cellular processes, such as lipid and glucose metabolism and pro-inflammatory cytokine production97,98. cAMP is thought to negatively regulate autophagy, as its major effector, protein kinase A (PKA)97, inhibits autophagy in yeast by directly phosphorylating Atg13 (which is a component of the Atg1 complex), and cAMP- and PKA-modulating drugs have been reported to block autophagy in mammals99. Many bacteria express cAMP-increasing toxins to inhibit host innate immune responses. For example, oedema factor toxin from Bacillus anthracis is an adenylyl cyclase that can directly increase intracellular cAMP levels100, and cholera toxin from Vibrio cholerae is an ADP ribosyltransferase that is capable of indirectly increasing cAMP by activating host adenylyl cyclases101. Both toxins have inhibitory effects on host cell autophagy induction: when cells were treated with purified toxins, the induction of different types of autophagy was significantly reduced, including rapamycin-induced autophagy, S. Typhimurium-induced autophagy and LAP4, suggesting that cAMP regulates an upstream signal that is common for all of the above tested autophagy pathways.

Direct interference with the activity of autophagy components. Some bacteria inhibit autophagy by directly interfering with the activity of autophagy components (Fig. 3a). For example, Legionella pneumophila induces autophagy in infected mouse macrophages in a manner that is dependent on the bacterial type IV secretion system (T4SS; known as the Dot/Icm secretion system)102. The bacterium is internalized in a phagosome wrapped by ER structures (a process that is thought to favour bacterial growth), in which autophagy components, such as ATG7 and LC3, are sequentially recruited to eventually deliver the bacterium to lysosomes102. However, it was recently shown that L. pneumophila can avoid autophagy targeting during infection of human embryonic kidney 293 cells10 by the production of the T4SS effector RavZ. This protein functions as an ATG4B-like cysteine protease that directly targets the amide bond between the tyrosine and the glycine at the C terminus of LC3, which is covalently linked to PE on autophagy induction to form LC3–PE10. Therefore, RavZ irreversibly deconjugates LC3 from PE and inhibits autophagosome formation. This is the first evidence of a bacterial effector protein mimicking the function of a host autophagy component to modify another critical autophagy protein and inhibit the whole process.

Another example of a bacterium that interferes with autophagy components is Shigella flexneri, which invades epithelial cells and escapes from the endosomal compartment into the cytoplasm to multiply and disseminate to other cells. S. flexneri can evade autophagy by directly inactivating the autophagy regulator RAB1, which is a small RAB GTPase that also mediates ER-to-Golgi trafficking. Recent studies have shown that RAB1 is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells103,104, possibly by controlling the levels of PtdIns3P on the omegasome by targeting the PtdIns3-phosphatase myotubularin-related 6 to the omegasomal membrane105. Another study reported that the S. flexneri T3SS effector VirA has a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) domain, which suggests that it can inactivate RAB GTPases9. Indeed, in wild-type bacteria, VirA inactivates RAB1, thus inhibiting autophagy induction and, in the absence of VirA, bacteria are more efficiently decorated by LC3 (Ref. 9) (Fig. 3b).

Evasion of autophagy recognition by masking the bacterial surface. Some bacteria avoid recognition by the autophagy machinery by masking themselves with host molecules. One such example is S. flexneri, which produces IcsB, a virulence factor secreted by the T3SS that is important for bacterial pathogenesis at a post-invasion stage106,107. Δ_icsB_ bacteria, which still escape into the cytosol, have a reduced ability to spread into neighbouring cells in certain polarized cells106,107. These bacteria become sequestered in multilamellar autophagosomes by the ubiquitin–p62 and NDP52–LC3 pathways, and show defective replication6,54. Compared with Δ_icsB_ bacteria (of which ∼35% are targeted to autophagosomes at 2 hours post-infection and ∼50% are targeted to autophagosomes at 6 hours post-infection), only ∼10% of wild-type bacteria are targeted for autophagy throughout the first 6 hours of infection, which suggests that S. flexneri uses IcsB to escape autophagy6. In fact, IcsB binds to a bacterial surface protein, IcsA (also known as VirG), and competes with its binding to host ATG5, thereby masking the bacteria from ATG protein recognition6 (Fig. 3b). In addition, when compared with wild-type bacteria, Δ_icsB_ mutants are more frequently surrounded by cage-like structures formed by septins, a group of conserved GTP-binding proteins that are often found at the cell-bud neck during cell division, and these entrapped bacteria are targeted for autophagy108. As septins are necessary for the recruitment of ubiquitin, p62 and NDP52 to the bacteria54, it is possible that IcsB masks the bacteria from septins and prevents their autophagic targeting. Identifying the septin binding partners on bacteria and elucidating their interactions with IcsB will be necessary to fully understand how IcsB blocks septin cage capture.

Listeria monocytogenes is another example of a bacterial pathogen that can mask itself to avoid autophagy recognition. During L. monocytogenes infection of mouse macrophages, the bacterium is internalized by phagocytosis but damages the phagosomal membrane, by secretion of the pore-forming toxin listeriolysin O (LLO) and other bacterial and host factors, and escapes into the cytosol to replicate109. Cytosolic bacteria express ActA, a cell surface protein that recruits the host ARP2/3 (actin-related protein 2/3) complex, which can then polymerize actin on the bacterial surface. The forces that are associated with actin polymerization promote bacterial intracellular motility and cell-to-cell spread110, which are thought to help the bacteria to escape autophagosome capture111,112. Notably, Δ_actA_ mutant bacteria are sequestered in LC3-positive, double-membrane vacuoles following the addition of the antibiotic chloramphenicol to block bacterial protein synthesis111,113. By contrast, wild-type bacteria are not targeted for autophagy even when treated with chloramphenicol, which suggests that when bacteria have acquired actin on their cell surface they become capable of escaping autophagy at later times during the infection. However, another study using a different L. monocytogenes strain found that it was not the actin-based motility but instead the ability of ActA to recruit host proteins (such as actin, the ARP2/3 complex and vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein) that enabled the bacteria to escape autophagy8. Specifically, at 2 hours and 4 hours post-infection, only ∼5% of wild-type bacteria were LC3-positive (and thus targeted for autophagy), but nearly 60% of Δ_actA2_ bacteria were associated with LC3 (Ref. 8). However, _actA_-mutant bacteria, which cannot polymerize actin and lack motility but can recruit other host proteins, successfully escaped autophagy recognition. This suggests that L. monocytogenes uses ActA to recruit host cytoskeleton proteins on the bacterial surface and mask the bacterium from ubiquitin recognition and autophagy targeting.

The recently identified L. monocytogenes virulence factor internalin K (InlK) also has a role in autophagy escape by interacting with mammalian host major vault protein (MVP) and recruiting it to the bacterial surface7. MVP and actin are distributed to opposite sides of the bacterial surface and each shields one part of the bacterium to avoid ubiquitin–p62–LC3-mediated autophagy recognition.

Escaping autophagy by as yet unclear mechanisms. Some bacteria use their effector proteins to escape autophagy by mechanisms that remain unclear in terms of the target of the effectors or the exact stage of autophagy that they interfere with. One such example is the Gram-negative bacterium B. pseudomallei, which uses a T3SS to escape from the phagosome into the cytosol, where it obtains actin-based motility, replicates and disseminates. Studies have shown that a very small population (∼5–10%) of wild-type B. pseudomallei is targeted for LAP72. Mutants that lack the T3SS3 effector BopA or the translocator BipD are defective in phagosomal escape and exhibit higher levels of colocalization with LC3 (∼30–40%) and LAMP1, indicating that wild-type bacteria use T3SS3 to avoid autophagy recognition. However, most wild-type bacteria enter the cytosol but are not targeted by autophagy. In this case, evasion of autophagy is mediated by T3SS1, as bacteria that lack the putative T3SS1 ATPase encoded by bpscN successfully enter the cytosol but are more efficiently targeted by LC3 and show defective survival in RAW macrophages114,115.

M. tuberculosis str. Erdman has been shown to be targeted and eliminated by autophagy in mouse macrophages (∼30% of bacteria were LC3-positive at 4 hours post-infection)116. Another study showed that only ∼10% of wild-type bacteria were targeted for autophagy117. Interestingly, treatment with small interfering RNA against coronin 1a, which is a protein that associates with filamentous actin, increased the percentage of LC3-positive bacteria to ∼30%, and bacterium-containing phagosomes were captured in autophagosomes via ubiquitin–p62–LC3 recruitment. Thus, in this case, the bacteria interfered with coronin 1a to avoid autophagy targeting. However, the mechanisms by which M. tuberculosis can modulate coronin 1a to inhibit autophagy remain unclear.

Blocking autophagosome fusion with the lysosome. Another group of bacteria are recognized by autophagy and are sequestered in autophagosomes but can block or delay the maturation of bacterium-containing autophagosomes into degradative autolysosomes, thus avoiding autophagic killing. The mechanisms by which these bacteria block autophagosome fusion with the lysosome remain mostly unknown. For example, infection with adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC) triggers the accumulation of autophagosomes in the cytosol as well as the sequestration of intracellular bacteria into canonical autophagosomes118. However, although the AIEC-containing autophagosomes acquire LAMP1, they do not fully mature into degradative autolysosomes, so the bacteria avoid killing. Notably, the upregulation of autophagy by starvation or rapamycin treatment can restrict AIEC growth, suggesting that autophagy is an immune defence mechanism against AIEC118.

Early after Mycobacterium marinum infection of macrophages, LC3 is recruited to a population of _M. marinum_-containing phagosomes119. These LC3-positive compartments have a single membrane and are decorated with the late endosomal proteins RAB7 and LAMP1, but they do not acquire the lysosomal hydrolase cathepsin D and are not degradative, indicating a block of the LC3-associated phagosome fusion with the lysosome.

Other bacteria, such as M. tuberculosis str. H37Rv120, Chlamydia trachomatis121,122, Yersinia pestis123 and Helicobacter pylori124,125, have also been shown to accumulate in non-acidic or non-degradative autophagosomes during infection, but less is known about how these bacteria block autophagosome fusion with the lysosome.

Hijacking autophagy for growth. Some bacteria even actively use autophagy for intracellular growth and infection, and show defective replication in autophagy-deficient cells. These bacteria include Staphylococcus aureus13, Anaplasma phagocytophilum12,126, Coxiella burnetii127,128,129,130, Brucella abortus131, Serratia marcescens132, M. tuberculosis (str. Erdman in epithelial cells)133, L. pneumophila (in permissive A/J mice)102,134, Brucella melitensis135, Porphyromonas gingivalis136, uropathogenic E . coli137 and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis138. In most cases, these bacteria actively induce autophagy but at the same time block autophagosome fusion with the lysosome, then use the autophagosome as a replicative niche for their growth.

A well-studied example of a bacterium that uses autophagy components for the biogenesis of its replication compartment is S. aureus. The bacteria become sequestered in double-membrane autophagosomes during infection of HeLa cells, but fusion of these autophagosome with the lysosome is inhibited and they are used as replicative niches13. Following replication, the bacteria escape into the cytosol and cause autophagy-dependent cell death, and this depends on host ATG5 (Ref. 13) (but not on PtdIns3KC3 and BECN1 (Ref. 139)) and the bacterial accessory gene regulator (Agr) system, specifically the Agr-secreted α-haemolysin (Hla). Indeed, agr and hla mutants cannot trigger autophagy and are delivered to lysosomes, where they are degraded13,139. Interestingly, S. aureus infection decreased cellular cAMP levels and reduced the activity of the cAMP effector exchange protein directly activated by cAMP 1 (EPAC; also known as RAPGEF3) and the downstream factor RAP2B140, suggesting that bacteria trigger autophagy by inhibiting the cellular cAMP–EPAC–RAP2B pathway. Notably, RAP2B is known to increase the levels of cytoplasmic calcium, which is required for the activation of calpains, a family of cysteine proteases that cleave ATG5 to generate a form of ATG5 that does not function in autophagy but instead is involved in apoptosis induction. Similarly, A. phagocytophilum grows in double-membrane vacuoles that are decorated with autophagy proteins, such as LC3 and BECN1 (Refs 12, 126). Autophagosome formation is nucleated by the bacterial T4SS secreted effector anaplasma translocated substrate 1, which directly binds BECN1 (Ref. 126). However, the autophagosomes do not acquire the late endosomal and lysosomal protein LAMP3, indicating that fusion with the lysosome is impaired. How bacteria block autophagosome maturation is unclear.

Another example of a bacterium that hijacks autophagy is C. burnetii, which is the causative agent of Q fever. C. burnetii survives after invasion of host cells in large _Coxiella_-replicative vacuoles (CRVs) that are decorated with the autophagy components LC3, BECN1 and RAB24 (Refs 127, 128, 129, 130). Overexpressing LC3 or BECN1 promotes bacterial infection and increases the number and size of the CRVs at early infection times, and inhibition of autophagy impairs CRV formation and bacterial replication127,130. C. burnetii infection also induces recruitment of the anti-apoptotic protein B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) to the CRV, and the interaction between BECN1 and BCL-2 is important for CRV development and inhibition of apoptosis130. Therefore, the bacteria use autophagy components for intracellular replication and block apoptosis to promote persistent infection.

In addition to promoting their growth, some bacteria hijack autophagy components to promote their intercellular spreading. B. abortus resides in a _Brucella_-containing vacuole (BCV) after internalization by phagocytic or epithelial cells, and traffics from this endocytic compartment to the ER to form the ER-derived BCV (rBCV), which is permissive for bacterial replication. At a later infection stage, rBCVs further convert into double- or multi-membrane autophagic BCVs (aBCVs), and this requires ULK1 and BECN1–ATG14L–PtdIns3KC3 activity but is independent of membrane elongation factors, including ATG12–ATG5–ATG16L1 and LC3–PE131. At very late time points during infection, heavily infected cells release bacteria and cause re-infection of neighbouring cells, which generates infection foci. Approximately 80% of these infection foci have been shown to have aBCV-containing cells, and formation of infection foci depended on ULK1 or BECN1 expression as well as on aBCV formation131. Collectively, these results suggest that B. abortus hijacks some of the autophagy components to form the aBCV, which enables bacterial cell-to-cell spread. It was speculated that the aBCVs can promote the release of bacteria out of the cell, but further work is needed to clarify the possible mechanisms that are involved.

Conclusion

Autophagy was first shown to target intracellular pathogenic bacteria for degradation in 2003, when a study reported that Δ_actA_-mutant L. monocytogenes was captured in autophagosomes under certain conditions113. In the following year, wild-type GAS was shown to be sequestered and eliminated by autophagy during infection of host cells85, which indicates that autophagy is an important host defence mechanism against bacterial pathogens. Since these two seminal studies, there has been a flurry of research on antibacterial autophagy by microbiologists, cell biologists and immunologists. Notably, although bacteria can be targeted by autophagy, increasing evidence suggests that pathogenic bacteria have developed many ways of interfering with the host autophagy machinery. These include the use of virulence factors to camouflage the bacteria or to directly subvert autophagy signalling and/or autophagy proteins, thereby avoiding autophagy targeting. Bacterial factors can mimic modifiers of autophagy components to shut down their proper functions or directly bind and recruit autophagy proteins to the bacteria to favour their growth.

Many key questions in the field remain to be answered. First, the mechanisms of the signalling induction pathways that trigger xenophagy are largely unknown. So far, S. Typhimurium-induced autophagy is the best-studied model, and multiple pathways have been found to contribute to xenophagy. Of note, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing 1 (NOD1) and NOD2, which are cytosolic NOD-like receptors (NLRs) that detect peptidoglycans on intracellular pathogens, are involved in the induction of autophagy targeting of S. flexneri and L. monocytogenes by directly binding to ATG16L1 and recruiting it to the bacterial entry site on the plasma membrane141. It will be important to investigate whether other bacteria that can be sensed by NOD1 and NOD2 also trigger xenophagy by the same mechanism. It will also be necessary to characterize how different signalling pathways regulate xenophagy induction at the same time in a coordinated manner, as well as how they activate autophagy initiation proteins, such as the ULK1 complex.

The mechanisms of selective cargo recognition are not fully understood. Although the ubiquitin–adaptors–LC3 pathway seems to be the main mechanism of autophagy recognition for some bacteria, other mechanisms also exist. For example, tectonin β-propeller repeat-containing protein 1 (TECPR1) is thought to function as a cargo receptor that links autophagosomes to S. flexneri, S. Typhimurium and GAS by interacting with ATG5 and WIPI2 (Ref. 142). However, it remains unknown how TECPR1 recognizes different bacteria. Moreover, TECPR1 only localizes to ubiquitin-negative bacteria142, suggesting that it mediates a ubiquitin-independent pathway. In addition, a recent study showed that human transmembrane protein 59 interacts with ATG16L1 via a 19-amino-acid-long motif143, thereby selectively targeting endosomes to autophagy. The same ATG16L1-binding motif was found in other proteins, suggesting that adaptor proteins that engage ATG16L1 could target other specific cargoes, such as bacteria, to autophagy.

How certain bacteria block autophagosome fusion with lysosomes, and whether bacterial effectors are involved, remains to be fully elucidated. It is possible that bacteria use their virulence factors to inhibit the recruitment of key factors that are involved in autophagosome–lysosome fusion, such as RAB7, to the bacterium-containing autophagosomes. Searching for bacterial mutants that do not block autophagosome fusion with lysosomes might provide some answers.

Finally, it is unknown, in most cases, whether all components of the canonical autophagy machinery are involved in xenophagy and whether they function in their canonical manner. As discussed above, some bacteria are targeted by LAP, which does not require the ULK1 complex, suggesting that different initiation mechanisms, which possibly do not require mTORC1, might be involved. S. aureus induces xenophagy independently of the BECN1 complex140, and it is unclear whether PtdIns3KC3-independent sources of PtdIns3P are involved in inducing xenophagy or whether PtdIns3P is dispensable in this context.

Investigating the interactions between bacterial factors and ATG proteins has been a major focus of recent research, and it will remain one for many years to come. A better understanding of the mechanisms by which bacteria manipulate autophagy will inform drug design and the therapeutic treatment of bacterial infections.

References

- Klionsky, D. J. et al. How shall I eat thee? Autophagy 3, 413–416 (2007).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Shahnazari, S. & Brumell, J. H. Mechanisms and consequences of bacterial targeting by the autophagy pathway. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 68–75 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Baxt, L. A., Garza-Mayers, A. C. & Goldberg, M. B. Bacterial subversion of host innate immune pathways. Science 340, 697–701 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Shahnazari, S., Namolovan, A., Mogridge, J., Kim, P. K. & Brumell, J. H. Bacterial toxins can inhibit host cell autophagy through cAMP generation. Autophagy 7, 957–965 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Tattoli, I. et al. Amino acid starvation induced by invasive bacterial pathogens triggers an innate host defense program. Cell Host Microbe 11, 563–575 (2012). This study shows that bacteria inhibit autophagy induction signalling by affecting mTOR localization.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ogawa, M. et al. Escape of intracellular Shigella from autophagy. Science 307, 727–731 (2005). This work shows that some bacterial pathogens can avoid autophagy recognition by camouflaging themselves with effector proteins.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Dortet, L. et al. Recruitment of the major vault protein by InlK: a Listeria monocytogenes strategy to avoid autophagy. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002168 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yoshikawa, Y. et al. Listeria monocytogenes ActA-mediated escape from autophagic recognition. Nature Cell Biol. 11, 1233–1240 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Dong, N. et al. Structurally distinct bacterial TBC-like GAPs link Arf GTPase to Rab1 inactivation to counteract host defenses. Cell 150, 1029–1041 (2012). This study shows that a bacterial effector can turn off an autophagy-regulating RAB GTPase to escape killing of the bacterium by autophagy.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Choy, A. et al. The Legionella effector RavZ inhibits host autophagy through irreversible Atg8 deconjugation. Science 338, 1072–1076 (2012). This study shows that a bacterial effector can directly uncouple the LC3–PE conjugation to inhibit autophagy.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Chargui, A. et al. Subversion of autophagy in adherent invasive _Escherichia coli_-infected neutrophils induces inflammation and cell death. PLoS ONE 7, e51727 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Niu, H., Yamaguchi, M. & Rikihisa, Y. Subversion of cellular autophagy by Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Cell. Microbiol. 10, 593–605 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Schnaith, A. et al. Staphylococcus aureus subvert autophagy for induction of caspase-independent host cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 2695–2706 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Parzych, K. R. & Klionsky, D. J. An overview of autophagy: morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/ars.2013.5371 (2013).

- Axe, E. L. et al. Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 182, 685–701 (2008).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - He, C. & Klionsky, D. J. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 67–93 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Mizushima, N. The role of the Atg1/ULK1 complex in autophagy regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 132–139 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Jung, C. H. et al. ULK-Atg13-FIP200 complexes mediate mTOR signaling to the autophagy machinery. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1992–2003 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ganley, I. G. et al. ULK1·ATG13·FIP200 complex mediates mTOR signaling and is essential for autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 12297–12305 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Itakura, E. & Mizushima, N. Characterization of autophagosome formation site by a hierarchical analysis of mammalian Atg proteins. Autophagy 6, 764–776 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Komduur, J. A., Veenhuis, M. & Kiel, J. A. The Hansenula polymorpha PDD7 gene is essential for macropexophagy and microautophagy. FEMS Yeast Res. 3, 27–34 (2003).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kanki, T. et al. A genomic screen for yeast mutants defective in selective mitochondria autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 4730–4738 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kim, J. & Klionsky, D. J. Autophagy, cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting pathway, and pexophagy in yeast and mammalian cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 303–342 (2000).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kageyama, S. et al. The LC3 recruitment mechanism is separate from Atg9L1-dependent membrane formation in the autophagic response against Salmonella. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 2290–2300 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Nair, U., Cao, Y., Xie, Z. & Klionsky, D. J. Roles of the lipid-binding motifs of Atg18 and Atg21 in the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway and autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 11476–11488 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Polson, H. E. et al. Mammalian Atg18 (WIPI2) localizes to omegasome-anchored phagophores and positively regulates LC3 lipidation. Autophagy 6, 506–522 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mari, M. et al. An Atg9-containing compartment that functions in the early steps of autophagosome biogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 190, 1005–1022 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yamamoto, H. et al. Atg9 vesicles are an important membrane source during early steps of autophagosome formation. J. Cell Biol. 198, 219–233 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Orsi, A. et al. Dynamic and transient interactions of Atg9 with autophagosomes, but not membrane integration, are required for autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 1860–1873 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Young, A. R. et al. Starvation and ULK1-dependent cycling of mammalian Atg9 between the TGN and endosomes. J. Cell Sci. 119, 3888–3900 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mizushima, N. et al. A protein conjugation system essential for autophagy. Nature 395, 395–398 (1998).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mizushima, N. et al. Dissection of autophagosome formation using Apg5-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells. J. Cell Biol. 152, 657–668 (2001).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Mizushima, N. et al. Mouse Apg16L, a novel WD-repeat protein, targets to the autophagic isolation membrane with the Apg12-Apg5 conjugate. J. Cell Sci. 116, 1679–1688 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Moreau, K., Ravikumar, B., Renna, M., Puri, C. & Rubinsztein, D. C. Autophagosome precursor maturation requires homotypic fusion. Cell 146, 303–317 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Fujita, N. et al. The Atg16L complex specifies the site of LC3 lipidation for membrane biogenesis in autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 2092–2100 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hanada, T. et al. The Atg12-Atg5 conjugate has a novel E3-like activity for protein lipidation in autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37298–37302 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Tanida, I., Ueno, T. & Kominami, E. LC3 conjugation system in mammalian autophagy. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 36, 2503–2518 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Nair, U. et al. A role for Atg8–PE deconjugation in autophagosome biogenesis. Autophagy 8, 780–793 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yu, Z. Q. et al. Dual roles of Atg8–PE deconjugation by Atg4 in autophagy. Autophagy 8, 883–892 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Nakatogawa, H., Ichimura, Y. & Ohsumi, Y. Atg8, a ubiquitin-like protein required for autophagosome formation, mediates membrane tethering and hemifusion. Cell 130, 165–178 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Xie, Z., Nair, U. & Klionsky, D. J. Atg8 controls phagophore expansion during autophagosome formation. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 3290–3298 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Jager, S. et al. Role for Rab7 in maturation of late autophagic vacuoles. J. Cell Sci. 117, 4837–4848 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Itakura, E., Kishi-Itakura, C. & Mizushima, N. The hairpin-type tail-anchored SNARE syntaxin 17 targets to autophagosomes for fusion with endosomes/lysosomes. Cell 151, 1256–1269 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Tanaka, Y. et al. Accumulation of autophagic vacuoles and cardiomyopathy in LAMP-2-deficient mice. Nature 406, 902–906 (2000).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Eskelinen, E. L. et al. Role of LAMP-2 in lysosome biogenesis and autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 3355–3368 (2002).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Reggiori, F. & Klionsky, D. J. Autophagic processes in yeast: mechanism, machinery and regulation. Genetics 194, 341–361 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hanna, R. A. et al. Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) interacts with Bnip3 protein to selectively remove endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria via autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 19094–19104 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Liu, L. et al. Mitochondrial outer-membrane protein FUNDC1 mediates hypoxia-induced mitophagy in mammalian cells. Nature Cell Biol. 14, 177–185 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Novak, I. et al. Nix is a selective autophagy receptor for mitochondrial clearance. EMBO Rep. 11, 45–51 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Boyle, K. B. & Randow, F. The role of 'eat-me' signals and autophagy cargo receptors in innate immunity. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 16, 339–348 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Dupont, N. et al. Shigella phagocytic vacuolar membrane remnants participate in the cellular response to pathogen invasion and are regulated by autophagy. Cell Host Microbe 6, 137–149 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Pankiv, S. et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24131–24145 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kim, P. K., Hailey, D. W., Mullen, R. T. & Lippincott-Schwartz, J. Ubiquitin signals autophagic degradation of cytosolic proteins and peroxisomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 20567–20574 (2008).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Mostowy, S. et al. p62 and NDP52 proteins target intracytosolic Shigella and Listeria to different autophagy pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 26987–26995 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zheng, Y. T. et al. The adaptor protein p62/SQSTM1 targets invading bacteria to the autophagy pathway. J. Immunol. 183, 5909–5916 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kirkin, V. et al. A role for NBR1 in autophagosomal degradation of ubiquitinated substrates. Mol. Cell 33, 505–516 (2009).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Thurston, T. L., Ryzhakov, G., Bloor, S., von Muhlinen, N. & Randow, F. The TBK1 adaptor and autophagy receptor NDP52 restricts the proliferation of ubiquitin-coated bacteria. Nature Immunol. 10, 1215–1221 (2009).

Article Google Scholar - Wild, P. et al. Phosphorylation of the autophagy receptor optineurin restricts Salmonella growth. Science 333, 228–233 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Deosaran, E. et al. NBR1 acts as an autophagy receptor for peroxisomes. J. Cell Sci. 126, 939–952 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Chong, A. et al. Cytosolic clearance of replication-deficient mutants reveals Francisella tularensis interactions with the autophagic pathway. Autophagy 8, 1342–1356 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Cheong, H., Lindsten, T., Wu, J., Lu, C. & Thompson, C. B. Ammonia-induced autophagy is independent of ULK1/ULK2 kinases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 11121–11126 (2011).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Nishida, Y. et al. Discovery of Atg5/Atg7-independent alternative macroautophagy. Nature 461, 654–658 (2009). This study shows that autophagy can occur in the absence of the two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems that are essential for autophagosome formation.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Grishchuk, Y., Ginet, V., Truttmann, A. C., Clarke, P. G. & Puyal, J. Beclin 1-independent autophagy contributes to apoptosis in cortical neurons. Autophagy 7, 1115–1131 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Scarlatti, F., Maffei, R., Beau, I., Codogno, P. & Ghidoni, R. Role of non-canonical Beclin 1-independent autophagy in cell death induced by resveratrol in human breast cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 15, 1318–1329 (2008).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Zhu, J. H. et al. Regulation of autophagy by extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases during 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced cell death. Am. J. Pathol. 170, 75–86 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Liao, C. C., Ho, M. Y., Liang, S. M. & Liang, C. M. Recombinant protein rVP1 upregulates BECN1-independent autophagy, MAPK1/3 phosphorylation and MMP9 activity via WIPI1/WIPI2 to promote macrophage migration. Autophagy 9, 5–19 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wong, C. H. et al. Simultaneous induction of non-canonical autophagy and apoptosis in cancer cells by ROS-dependent ERK and JNK activation. PLoS ONE 5, e9996 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kondylis, V. et al. Endosome-mediated autophagy: An unconventional MIIC-driven autophagic pathway operational in dendritic cells. Autophagy 9 861–880 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Sanjuan, M. A. et al. Toll-like receptor signalling in macrophages links the autophagy pathway to phagocytosis. Nature 450, 1253–1257 (2007). This study reports the discovery of the LAP pathway and shows that recruiting autophagy components to the phagosome promotes phagosome fusion with the lysosome.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Huang, J. et al. Activation of antibacterial autophagy by NADPH oxidases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 6226–6231 (2009).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Martinez, J. et al. Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 alpha (LC3)-associated phagocytosis is required for the efficient clearance of dead cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17396–17401 (2011).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Gong, L. et al. The Burkholderia pseudomallei type III secretion system and BopA are required for evasion of LC3-associated phagocytosis. PLoS ONE 6, e17852 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Jia, K. et al. Autophagy genes protect against Salmonella Typhimurium infection and mediate insulin signaling-regulated pathogen resistance. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 14564–14569 (2009).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Brumell, J. H., Steele-Mortimer, O. & Finlay, B. B. Bacterial invasion: force feeding by Salmonella. Curr. Biol. 9, R277–R280 (1999).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Perrin, A. J., Jiang, X., Birmingham, C. L., So, N. S. & Brumell, J. H. Recognition of bacteria in the cytosol of mammalian cells by the ubiquitin system. Curr. Biol. 14, 806–811 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Birmingham, C. L., Smith, A. C., Bakowski, M. A., Yoshimori, T. & Brumell, J. H. Autophagy controls Salmonella infection in response to damage to the _Salmonella_-containing vacuole. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 11374–11383 (2006). This study shows that S . Typhimurium is targeted by autophagy in a damaged vacuole; on the basis of this work, extensive research has been done on the mechanisms of antibacterial autophagy, using S . Typhimurium as a model.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Huett, A. et al. The LRR and RING domain protein LRSAM1 is an E3 ligase crucial for ubiquitin-dependent autophagy of intracellular Salmonella Typhimurium. Cell Host Microbe 12, 778–790 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Thurston, T. L., Wandel, M. P., von Muhlinen, N., Foeglein, A. & Randow, F. Galectin 8 targets damaged vesicles for autophagy to defend cells against bacterial invasion. Nature 482, 414–418 (2012). This work reveals that sugar molecules on the plasma membrane can serve as signals to trigger antibacterial autophagy.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Shahnazari, S. et al. A diacylglycerol-dependent signaling pathway contributes to regulation of antibacterial autophagy. Cell Host Microbe 8, 137–146 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Fontayne, A., Dang, P. M., Gougerot-Pocidalo, M. A. & El-Benna, J. Phosphorylation of p47_phox_ sites by PKC α, βII, δ, and ζ: effect on binding to p22_phox_ and on NADPH oxidase activation. Biochemistry 41, 7743–7750 (2002).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lam, G. Y. et al. Listeriolysin O suppresses phospholipase C-mediated activation of the microbicidal NADPH oxidase to promote Listeria monocytogenes infection. Cell Host Microbe 10, 627–634 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Watson, R. O., Manzanillo, P. S. & Cox, J. S. Extracellular M. tuberculosis DNA targets bacteria for autophagy by activating the host DNA-sensing pathway. Cell 150, 803–815 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wang, W., Sacher, M. & Ferro-Novick, S. TRAPP stimulates guanine nucleotide exchange on Ypt1p. J. Cell Biol. 151, 289–296 (2000).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Manzanillo, P. S. et al. The ubiquitin ligase parkin mediates resistance to intracellular pathogens. Nature 501, 512–516 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Nakagawa, I. et al. Autophagy defends cells against invading group A Streptococcus. Science 306, 1037–1040 (2004). This is the first study to show that autophagy is an innate immune defence mechanism against an intracellular bacterial pathogen during natural infection.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Sakurai, A. et al. Specific behavior of intracellular Streptococcus pyogenes that has undergone autophagic degradation is associated with bacterial streptolysin O and host small G proteins Rab5 and Rab7. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22666–22675 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Joubert, P. E. et al. Autophagy induction by the pathogen receptor CD46. Cell Host Microbe 6, 354–366 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Nozawa, T. et al. The small GTPases Rab9A and Rab23 function at distinct steps in autophagy during Group A Streptococcus infection. Cell. Microbiol. 14, 1149–1165 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - O'Seaghdha, M. & Wessels, M. R. Streptolysin O and its co-toxin NAD-glycohydrolase protect group A Streptococcus from xenophagic killing. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003394 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Checroun, C., Wehrly, T. D., Fischer, E. R., Hayes, S. F. & Celli, J. Autophagy-mediated reentry of Francisella tularensis into the endocytic compartment after cytoplasmic replication. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 14578–14583 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Deuretzbacher, A. et al. β1 integrin-dependent engulfment of Yersinia enterocolitica by macrophages is coupled to the activation of autophagy and suppressed by type III protein secretion. J. Immunol. 183, 5847–5860 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Choi, J. H. et al. Orientia tsutsugamushi subverts dendritic cell functions by escaping from autophagy and impairing their migration. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7, e1981 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ko, Y. et al. Active escape of Orientia tsutsugamushi from cellular autophagy. Infect. Immun. 81, 552–559 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Eriksson, S., Lucchini, S., Thompson, A., Rhen, M. & Hinton, J. C. Unravelling the biology of macrophage infection by gene expression profiling of intracellular Salmonella enterica. Mol. Microbiol. 47, 103–118 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Shin, D. M. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Eis regulates autophagy, inflammation, and cell death through redox-dependent signaling. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001230 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kim, K. H. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Eis protein initiates suppression of host immune responses by acetylation of DUSP16/MKP-7. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 7729–7734 (2012).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Beebe, S. J. The cAMP-dependent protein kinases and cAMP signal transduction. Semin. Cancer Biol. 5, 285–294 (1994).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Serezani, C. H., Ballinger, M. N., Aronoff, D. M. & Peters-Golden, M. Cyclic AMP: master regulator of innate immune cell function. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 39, 127–132 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Holen, I., Gordon, P. B., Stromhaug, P. E. & Seglen, P. O. Role of cAMP in the regulation of hepatocytic autophagy. Eur. J. Biochem. 236, 163–170 (1996).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Leppla, S. H. Anthrax toxin edema factor: a bacterial adenylate cyclase that increases cyclic AMP concentrations of eukaryotic cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 79, 3162–3166 (1982).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Cassel, D. & Pfeuffer, T. Mechanism of cholera toxin action: covalent modification of the guanyl nucleotide-binding protein of the adenylate cyclase system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 75, 2669–2673 (1978).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Amer, A. O. & Swanson, M. S. Autophagy is an immediate macrophage response to Legionella pneumophila. Cell. Microbiol. 7, 765–778 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Huang, J. et al. Antibacterial autophagy occurs at PI(3)P-enriched domains of the endoplasmic reticulum and requires Rab1 GTPase. Autophagy 7, 17–26 (2010).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zoppino, F. C., Militello, R. D., Slavin, I., Alvarez, C. & Colombo, M. I. Autophagosome formation depends on the small GTPase Rab1 and functional ER exit sites. Traffic 11, 1246–1261 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mochizuki, Y. et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphatase myotubularin-related protein 6 (MTMR6) is regulated by small GTPase Rab1B in the early secretory and autophagic pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 1009–1021 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Allaoui, A., Mounier, J., Prevost, M. C. & Sansonetti, P. J. & Parsot, C. icsB: a Shigella flexneri virulence gene necessary for the lysis of protrusions during intercellular spread. Mol. Microbiol. 6, 1605–1616 (1992).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ogawa, M., Suzuki, T., Tatsuno, I., Abe, H. & Sasakawa, C. IcsB, secreted via the type III secretion system, is chaperoned by IpgA and required at the post-invasion stage of Shigella pathogenicity. Mol. Microbiol. 48, 913–931 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mostowy, S. et al. Entrapment of intracytosolic bacteria by septin cage-like structures. Cell Host Microbe 8, 433–444 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Dussurget, O., Pizarro-Cerda, J. & Cossart, P. Molecular determinants of Listeria monocytogenes virulence. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58, 587–610 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Gouin, E., Welch, M. D. & Cossart, P. Actin-based motility of intracellular pathogens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8, 35–45 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Birmingham, C. L. et al. Listeria monocytogenes evades killing by autophagy during colonization of host cells. Autophagy 3, 442–451 (2007).