PTEN mediates Notch-dependent stalk cell arrest in angiogenesis (original) (raw)

Introduction

Vessel sprouting is a central mechanism of blood vessel growth1,2 and it relies on the induction of specialized endothelial cell (EC) populations, each accounting for distinct functions. At the very front of the sprouts, tip cells provide guidance and migrate towards gradients of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A, but rarely proliferate2,3,4. Instead, trailing stalk cells located at the base of the sprout proliferate, establish adherent and tight junctions and form the vascular lumen1,2,5.

The tip cell phenotype is usually associated with high levels of Delta-like 4 (Dll4), which activate Notch in neighbouring stalk cells, preventing them from becoming a new tip cell. Notch signalling is initiated by receptor–ligand recognition between adjacent cells. This interaction results in two sequential proteolytic events that release the Notch intracellular domain (NICD). Subsequently, NICD translocates to the nucleus, where it forms a complex with the transcriptional factor Rbpj/Cbf1 and the Mastermind-like proteins to drive target gene expression6,7. Activation of Notch in ECs leads to cell cycle arrest both in vitro8 and in vivo9,10,11. However, it is still unclear how Notch exerts its negative effects on EC proliferation, and the transcriptional programme that triggers stalk cell function is not understood2,5,12. Furthermore, it is not clear how stalk cells are ultimately released from this arrest to provide sufficient cell numbers for the sprout to elongate and stabilize.

PTEN (phosphate and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome TEN) is a dual lipid/protein phosphatase, which is often underexpressed in cancer13,14,15. The main activity of PTEN is to dephosphorylate the lipid phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PtdIns(3,4,5)P3) at the -position, thereby counterbalancing class I phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signalling that mediates growth, cell division, survival, migration and metabolism13,16,17,18. Genetic studies in mouse and zebrafish point to a restrictive role of PTEN in angiogenesis. Mice lacking PTEN specifically in ECs exhibit cardiac failure and severe haemorrhages due to defects of the myocardial wall and impaired mural cell coverage of blood vessels19. Mutant zebrafish embryos lacking functional PTEN show enhanced angiogenesis20; whether this is due to a cell-autonomous effect of PTEN in ECs or is simply a consequence of increased VEGF levels is unclear. Importantly, the specific functions of PTEN in endothelial behaviour and vascular patterning remain unknown.

In most cells and tissues, PTEN localizes to the cytoplasm and the nucleus13,15. There is evidence to suggest that PTEN has nuclear, non-lipid phosphatase-dependent functions21,22. Interestingly, PTEN localization is cell cycle-dependent, with higher levels of nuclear PTEN during the G0–G1 phase than during the S phase23,24. This is in line with the observation that nuclear PTEN negatively regulates cell cycle progression13,22. Indeed, in late mitosis and G1, nuclear PTEN enhances the E3 ligase activity of APC/C by facilitating the association of APC/C with its activator Fzr1/Cdh1 (encoded by the Fzr1 gene), with no requirement of its phosphatase activity22. The APC/C-Fzr1/Cdh1 complex controls G1 progression by targeting several proteins for degradation, including mitotic cyclins (Cyclin-A), mitotic kinases (Aurora Kinase A (Aurora A) and Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1)), proteins involved in chromosome segregation and DNA replication (Geminin; ref. 25). Despite the large body of molecular evidence, the role and relevance of nuclear PTEN in physiology is poorly understood.

Here we report that endothelial PTEN regulates stalk cell proliferation during vessel development. Our data further identify PTEN as a key mediator of the antiproliferative responses of Notch. We show that Dll4/Notch signalling arrests stalk cell proliferation by inducing expression of PTEN to balance stalk cell numbers and coordinate patterning. On PTEN deletion, Notch signalling fails to arrest early stalk cells and result in defective sprout length and patterning. Our results strongly indicate that both catalytic and non-catalytic activities of PTEN contribute to this function, providing evidence for an important in vivo physiological function for the PTEN-APC/C-Fzr1/Cdh1/axis.

Results

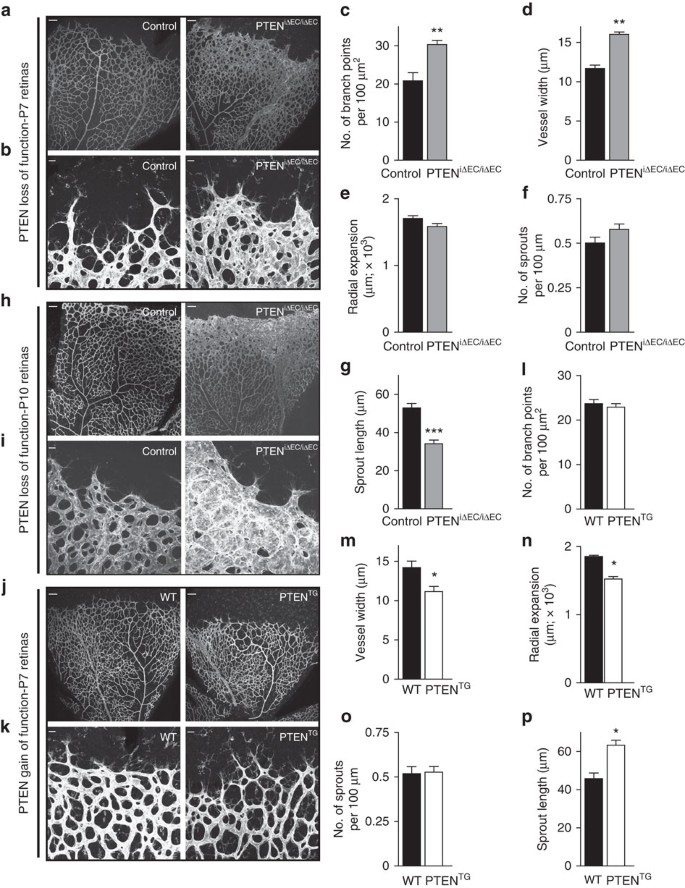

PTEN negatively regulates vascular density in angiogenesis

To study the EC-autonomous role of PTEN in sprouting angiogenesis, we crossed Pten flox/flox mice with PdgfbiCreER T2 transgenic mice that express a tamoxifen-activatable Cre recombinase in ECs26 (further referred to as PTENiΔEC/iΔEC) and assessed postnatal retinal angiogenesis. 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) was administrated in vivo at postnatal day 1 (P1) and P2, followed by analysis of the retinal vasculature at different time points. Comparing whole-mount-stained retinas of control (Pten flox/flox) to PTENiΔEC/iΔEC mice at P5 revealed a mild increase in vessel width (Supplementary Fig. 1a–g). By P7, loss of PTEN resulted in excessive branching and substantially increased vessel width (Fig. 1a–d), a phenotype that was further exacerbated at P10 (Fig. 1h,i). PTENiΔEC/iΔEC P7 retinas showed efficient recombination of the Cre-reporter R26-R and depletion of PTEN in the retinal endothelium (Supplementary Fig. 1h,i), with an increase in staining for phosphoS6 (pS6), a marker of PI3K pathway activation (Supplementary Fig. 1j). Isolated mouse lung ECs (mECs) from PTENiΔEC/iΔEC mice confirmed that effective depletion of PTEN protein in mECs was achieved 96 h following 4-OHT administration (Supplementary Fig. 1k,l). To further characterize the cell-autonomous role of PTEN in ECs, we therefore focused on the P7 time point. No differences in radial expansion (Fig. 1e) and in the number of sprouts per 100 μm of leading endothelial membrane were found in PTENiΔEC/iΔEC when compared with control retinas (Fig. 1f). Instead, the length of the sprouts was significantly reduced in the PTENiΔEC/iΔEC retinal vasculature compared with controls (Fig. 1g). The hyperplastic phenotype observed on PTEN loss was validated in an independent cellular system based on embryoid body (EB) formation, in which clusters of embryonic stem cells respond to VEGF by forming vascular tubes27. Compared with wild type (WT), PTEN null EBs showed increased sprout width and length (Supplementary Fig. 2a–d), with no differences in the number of sprouts (Supplementary Fig. 2e).

Figure 1: PTEN regulates vascular density.

(a,b) Whole-mount visualization of blood vessels by isolectin B4 (IB4) staining of control and PTENiΔEC/iΔEC littermates at P7. (c–g) Quantitative analysis of the retinas shown in a,b. (c) Vascular branch points per unit area (_n_≥6). (d) Vessel width (_n_≥4). (e) Radial expansion of blood vessels (_n_≥7). (f) Number of sprouts per vascular front length (_n_≥7). (g) Sprout length from the tip to the base of the sprout (_n_≥7). (h,i) Whole-mount visualization of blood vessels by IB4 staining of control and PTENiΔEC/iΔEC littermates at P10. (j,k) Whole-mount visualization of blood vessels by IB4 staining of WT and PTENTG littermates at P7. (l–p) Quantitative analysis of the retinas shown in j,k. (l) Vascular branch points per unit area (_n_=8). (m) Vessel width (_n_=12). (n) Radial expansion of blood vessels (_n_=4). (o) Number of sprouts per vascular front length (_n_=6). (p) Sprout length from the tip to the base of the sprout (_n_=6). Scale bars, 100 μm (a,h,j) and 20 μm (b,i,k). Error bars are s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed by nonparametric Mann–Whitney test.

Next, we sought to address whether regulated elevation in PTEN expression in vivo would oppose the phenotype induced by loss of PTEN. To this end, we used super-PTEN transgenic mice (PTENTG)28, a mouse model that allows moderate organismal elevation of PTEN levels (two-fold over WT littermates), including in the vasculature (Supplementary Fig. 1m). PTENTG retinas exhibited decreased vessel width and increased sprout length (Fig. 1j,k,m,p), with no changes in the number of branches (Fig. 1l) and sprouts (Fig. 1o). A slight reduction in radial expansion was also observed on moderate PTEN overexpression (Fig. 1n), similar to retinas from mice that are heterozygous for a kinase-dead p110α PI3K allele29. Neither loss nor gain of PTEN function resulted in changes in Dll4 or Notch target genes (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c), further supporting that PTEN is not required for tip/stalk selection. Analysis of EphB4, EphrinB2 and Nr2f2 gene expression, key genes involved in arteriovenous differentiation, did also not reveal any obvious difference between control and loss and gain of PTEN function in ECs, suggesting that PTEN signalling does not play a predominant role in this process (Supplementary Fig. 3d,e).

Taken together, these data uncover a selective role for PTEN in angiogenesis, regulating vascular density and consequently vessel growth in vivo.

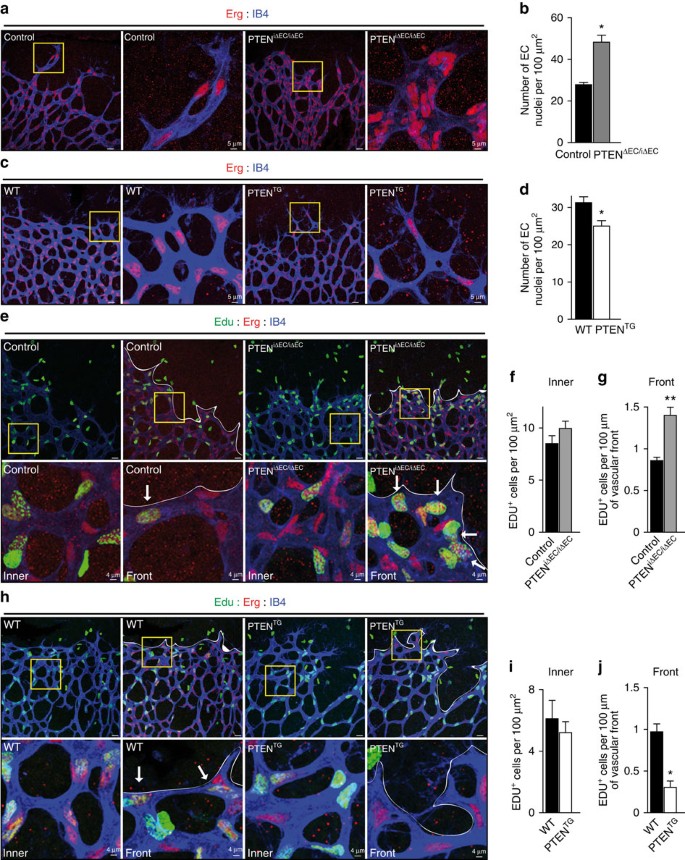

PTEN regulates endothelial stalk cell number

Previous data have shown that constitutive targeting of PTEN in ECs results in altered mural cell coverage19. Instead, immunostaining with desmin, a retinal pericyte marker30, did not reveal any obvious defect in mural cell coverage in PTENiΔEC/iΔEC retinas compared with control, consistent with the lack of sprouting defects on PTEN loss (Supplementary Fig. 3f).

Analysis of PTENiΔEC/iΔEC retinas stained with a nuclear endothelial marker (Erg) revealed increased EC numbers in the angiogenic vasculature (Fig. 2a,b). Conversely, elevated PTEN expression resulted in reduced EC numbers at the sprouting front (Fig. 2c,d). We sought to validate whether these differences relate to changes in EC proliferation. Surprisingly, no difference in the number of proliferative ECs located in the subfront retinal area, behind the sprouting front, was found on either loss (Fig. 2e,f) or gain of PTEN function (Fig. 2h,i). This is unexpected, given that in the growing vasculature ECs with high turnover are located in this subfront area (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b). To test whether PTEN regulated proliferation of ECs in other retinal locations, we focused on the first line of cells located at the sprouting front where proliferating cells are rarely observed (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b). Interestingly, a 40% increase in proliferation in PTENiΔEC/iΔEC retinas (Fig. 2g) or 60% reduction in PTENTG retinas (Fig. 2j) compared with control retinas was observed in ECs at the front. These data point towards a selective role of PTEN in restricting EC proliferation in cells located at the sprouting front.

Figure 2: PTEN negatively regulates stalk cell proliferation.

(a) IB4 (blue) and Erg (red) staining of control and PTENiΔEC/iΔEC littermate retinas at P7. Islets show higher magnification of selected regions shown to the right. (b) Quantification of EC nuclei per unit area assessed by Erg positivity in control and PTENiΔEC/iΔEC P7 retinas (_n_≥4). (c) IB4 (blue) and Erg (red) staining of WT and PTENTG littermate retinas at P7. Islets show higher magnification of selected regions shown to the right. (d) Quantification of EC nuclei per unit area assessed by Erg positivity in WT and PTENTG P7 retinas (_n_=8). (e) IB4 (blue), Erg (red) and Edu (green) staining of control and PTENiΔEC/iΔEC P7 retinas. Islets show higher magnification of selected regions shown below. Arrows indicate Edu-positive ECs in the sprouting front. (f) Quantification of Edu-positive cells per unit area assessed in control and PTENiΔEC/iΔEC P7 retinas (_n_≥7). (g) Quantification of number of Edu-positive cells located at the sprouting front expressed per vascular front length in control and PTENiΔEC/iΔEC P7 retinas (_n_=7). (h) IB4 (blue), Erg (red) and Edu (green) staining of WT and PTENTG littermate retinas at P7. Islets show higher magnification of selected regions shown below. Arrows indicate Edu-positive ECs in the sprouting front. (i) Quantification of Edu-positive cells per unit area assessed in WT and PTENTG P7 retinas (_n_=4). (j) Quantification of number of Edu-positive cells located at the sprouting front expressed per vascular front length in WT and PTENTG retinas (_n_=4). Scale bars, 20 μm (a,c,e,h). Error bars are s.e.m. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed by nonparametric Mann–Whitney test.

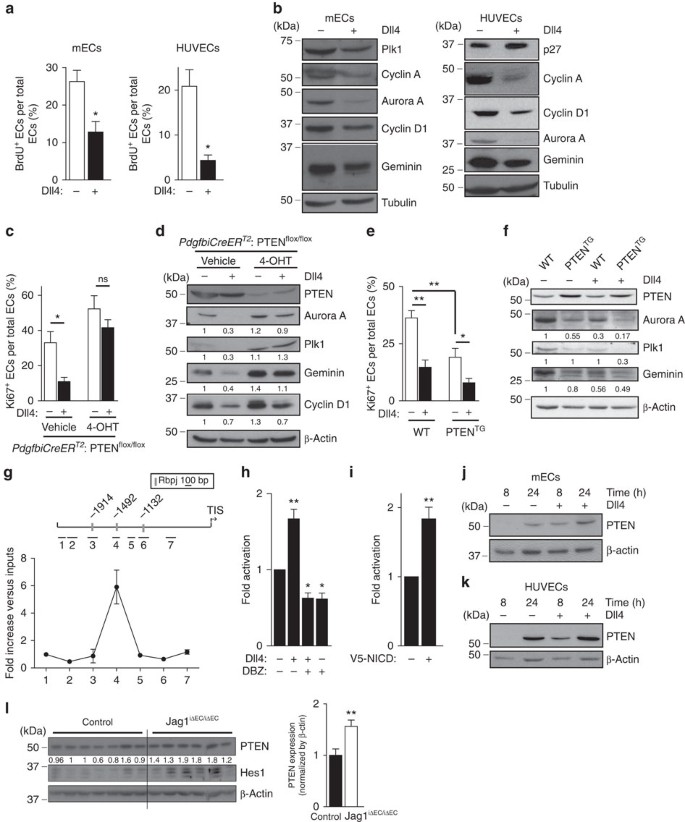

PTEN executes Notch-dependent cell cycle arrest

Given that the impact of PTEN loss or overexpression in vivo on proliferation are restricted to the sprouting front that is highly Notch-dependent9, we hypothesized that a functional connection exists between these two signalling pathways. Activation of Notch in mECs, both in vivo and in vitro, resulted in cell cycle arrest, shown by reduced 5-bromo-2'-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation (Supplementary Fig. 4c,d and Fig. 3a) and downregulation of cell cycle regulators including Cyclin D and A, Plk1, Aurora A and Geminin (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, genetic manipulation of PTEN levels in ECs altered the antiproliferative response to Notch activation (Fig. 3c,e). PTENiΔEC/iΔEC mECs failed to stop proliferation on Notch activation (Fig. 3c,d), whereas PTENTG mECs showed a 50% increase in the cell cycle arrest response (Fig. 3e,f). Consistent with a role of PTEN in regulating the cell cycle arrest, higher PTEN levels in ECs in vivo corresponded to nonproliferative cells (Supplementary Fig. 4e,f). Our results suggest that PTEN is necessary for the growth-suppressive activity of Notch signalling in ECs and imply that the PTEN loss-of-function phenotype is the result of an impaired response to Dll4 stimulation.

Figure 3: Notch limits EC proliferation by upregulating PTEN levels.

(a) Quantification of in vitro proliferation of mECs and HUVECs plated for 24 h in vehicle or Dll4-coated dishes, pulsed with BrdU for 2 h and subjected to immunostaining analysis. At least 100 cells per condition were counted (_n_=4). (b) Immunoblot analysis of mECs and HUVECs plated for 24 h in vehicle or Dll4-coated plates using the indicated antibodies (_n_=3). Molecular weight marker (kDa) is indicated. (c,e) Quantification of in vitro proliferation by Ki67 immunofluorescence of control and PTENiΔEC/iΔEC (c) and WT and PTENTG mEC (e) plated for 24 h in vehicle or Dll4-coated plates. Overall 100 cells per condition were counted (_n_=4). (d) Control and PTENiΔEC/iΔEC or (f) WT and PTENTG mEC were plated for 24 h in vehicle or Dll4-coated dishes, followed by immunoblot analysis using the indicated antibodies. The quantification of the relative immunoreactivity of each protein normalized to β-actin is represented as the mean of four different experiments in d,f. Molecular weight marker (kDa) is indicated. (g) ChIP with the anti-NICD antibody from HUVECs and the analysis of the PTEN locus by qPCR. A pool of two independent experiments is shown. (h,i) PTEN-luciferase reporter assays were performed in HUVECs with a 2,666-bp PTEN promoter construct (pGL3 PTEN Hind III-NotI). (h) Cells were plated for 6 h in vehicle or Dll4-coated dishes and (i) HUVECs were transfected with V5-NICD (_n_=3). (j,k) Immunoblot analysis of PTEN in lung mECs (j) and in HUVECs (k) plated for 8 or 24 h in vehicle or Dll4-coated plates (_n_=4). Molecular weight marker (kDa) is indicated. (l) Immunoblot analysis of PTEN and Hes in lung lysates from control (_n_=7) and Jag1iΔEC/iΔEC (_n_=6) pups. Molecular weight marker (kDa) is indicated. Error bars are s.e.m. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 were considered statistically significant. ns, not statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed by nonparametric Mann–Whitney test.

Because PTEN is required for the Notch-dependent regulation of endothelial proliferation, we tested whether PTEN expression is regulated by Notch. Bioinformatic analysis of the PTEN locus identified the presence of three Rbpj motifs that are conserved in both the human and mouse PTEN gene (Fig. 3g). We used chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChiP) analysis on human ECs to determine the recruitment of NICD protein to the PTEN promoter after 2 h of incubation with Dll4. PTEN promoter occupancy was determined using real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) probes that amplify seven regions spanning from −2,380 to −590 relative to the transcription initiation site. Our analysis revealed NICD occupancy in the −1,492 region, which contains one of the three predicted Rbpj-binding sites (Fig. 3g). We next validated the functional significance of Rbpj binding to the promoter in luciferase reporter assays. Indeed, analysis of PTEN promoter activity showed activation in response to Dll4 (Fig. 3h) and on overexpression of the intracellular domain of the Notch receptor (NICD; Fig. 3i). Importantly, enhanced PTEN promoter responsiveness to Dll4 was abrogated by the γ-secretase inhibitor dibenzazepine (DBZ; Fig. 3i). Western blot experiments confirmed that Dll4 stimulation results in elevated protein levels of PTEN in human ECs and mECs (Fig. 3j,k). Using lungs as highly vascularized tissue, we validated that overactivation of Notch signalling by inhibiting the Notch ligand, Jagged 1 (Jag1)11, resulted in higher PTEN expression levels (Fig. 3l). Taken together, these results demonstrate that PTEN is a target gene of Notch signalling in ECs, which becomes induced by Dll4 stimulation.

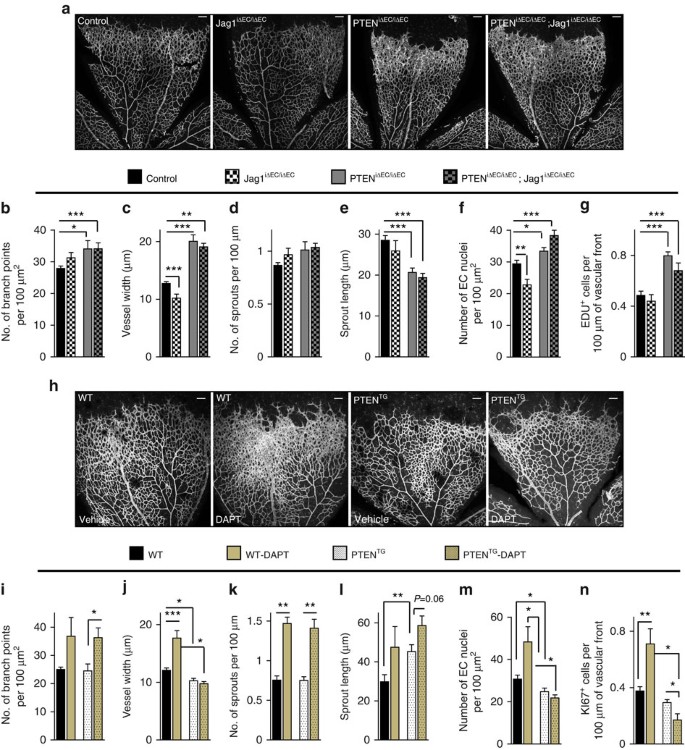

PTEN is required for Notch function in vivo

We sought to confirm the Notch/PTEN functional interaction in vivo. We took advantage of endothelial Jag1 inactivation, which results in reduced EC proliferation and decreased vascular branching due to overactivation of Notch signalling11. We hypothesized that, if the regulation of the angiogenic process by Notch requires the increase in PTEN function, loss of PTEN would prevent the phenotype of Jag1 deletion. We tested this hypothesis in inducible endothelial-cell-specific PTENiΔEC/iΔEC;Jag1iΔEC/iΔEC double mutants. The vasculature of Jag1iΔEC/iΔEC retinas showed reduced endothelial proliferation and reduced vessel width, confirming previous reports (Fig. 4a–g and Supplementary Fig. 5a)11. However, concomitant PTEN deletion abrogated the phenotype observed in Jag1iΔEC/iΔEC retinas (Fig. 4a–g), while the phenotype of PTEN loss remained unaffected by Jag1 deletion (the increase in endothelial proliferation at the spouting front). Next, we validated our hypothesis in the PTENTG mice by blocking Notch activation with the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT (N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetly)-L-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester) that strongly enhances angiogenesis partially due to increased EC proliferation9. Remarkably, DAPT-induced increase in vascular density at the angiogenic front was abolished by increased levels of PTEN (Fig. 4h,j,m,n and Supplementary Fig. 5b). However, elevated levels of PTEN did not prevent the enhanced sprouting caused by DAPT (Fig. 4i,k,l), further indicating that PTEN is not required for Notch-dependent tip/stalk selection.

Figure 4: PTEN interacts with Notch in vivo to negatively control stalk cell proliferation.

(a) Whole-mount visualization of blood vessels by IB4 staining of control, Jag1iΔEC/iΔEC, PTENiΔEC/iΔEC and PTENiΔEC/iΔEC; Jag1iΔEC/iΔEC littermates at P7. (b–g) Quantitative analysis of the retinas shown in a. Retinas from five independent litters were pooled for quantification. (b) Vascular branch points (_n_≥4). (c) Vessel width (_n_≥4). (d) Number of sprouts per vascular front length (_n_≥4). (e) Sprout length from the tip to the base of the sprout (_n_≥4). (f) Quantification of EC nuclei per unit area assessed by Erg positivity (_n_≥4). (g) Quantification of number of Edu-positive cells located at the vascular front expressed per sprouting front length (_n_≥3). (h) Whole-mount visualization of blood vessels by IB4 staining of WT and PTENTG P7 retinas treated with vehicle or DAPT (100 mg kg−1). (i–n) Quantitative analysis of the retinas shown in h. Retinas from three independent litters were pooled for quantification. (i) Vascular branch points per unit area (_n_≥4). (j) Vessel width (_n_≥4). (k) Number of sprouts per vascular front length (_n_≥4). (l) Sprout length from the tip to the base of the sprout (_n_≥4). (m) Quantification of endothelial nuclei per unit area assessed by Erg positivity (_n_≥4). (n) Quantification of number of Ki67-positive cells located at the vascular front expressed per sprouting front length (_n_=6). Scale bars, 100 μm (a,h). Error bars are s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed by nonparametric Mann–Whitney test.

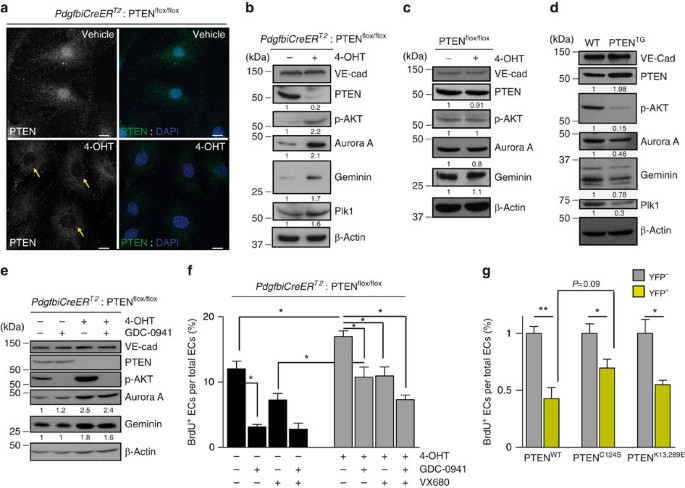

Dual function of PTEN in angiogenesis

To gain insight into the biological mechanism underlying the role of PTEN in sprouting angiogenesis, we investigated the contribution of phosphatase-dependent and -independent activities of PTEN at the organismal and cellular levels. We observed a compartmentalization of PTEN in the nucleus and cytoplasm in cultured control cells (Fig. 5a), whereas PTENiΔEC/iΔEC mECs showed no nuclear staining with some residual positivity in the cytoplasm. PTEN depletion in mECs resulted in increased Akt phosphorylation and in accumulation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase APC/C-Fzr1/Cdh1complex substrates Aurora A, Plk1 and Geminin (Fig. 5b). Control mECs treated with 4-OHT did not show any of the aforementioned changes (Fig. 5c). In contrast, mECs isolated from PTENTG lungs showed reduced Akt phosphorylation and reduced accumulation of E3 ubiquitin ligase APC/C-Fzr1/Cdh1 complex substrates compared with WT cells (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5: Catalytic and non-catalytic roles of PTEN regulate EC proliferation.

(a) Confocal images of PTEN (green) and DAPI immunofluorescence in PdgfbiCreER T2; PTENflox/flox mECs treated with vehicle or with 4-OHT for 96 h. Yellow arrows indicate the lack of PTEN staining in the nucleus of PTEN null cells. Scale bars, 10 μm (_n_=3). (b–d) Exponentially growing mECs were lysated, followed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. PdgfbiCreER T2; PTENflox/flox (b) and PTENflox/flox (c) mECs were treated for 96 h with vehicle or 4-OHT. (d) WT and PTENTG mECs were cultured for 48 h before cell lysis and immunoblotting. (e) PdgfbiCreER T2; PTENflox/flox mECs were treated for 96 h with vehicle or 4-OHT. Before cell lysis, cells were pretreated for 2 h with GDC-0941 (1 μM). The quantification of the relative immunoreactivity of each protein normalized to β-actin is represented as the mean from at least three different experiments in b–e. Molecular weight marker (kDa) is indicated. (f) Exponentially growing control and PTENiΔEC/iΔEC mECs were treated for 48 h with test compounds or vehicle, and then were pulsed with BrdU for 2 h and subjected to immunostaining analysis. Inhibitors and doses used were as follows: GDC-0941 (pan-class I PI3K inhibitor; 1 μM) and VX680 (Aurora Kinase inhibitor; 0.5 μM). Data shown are means of four independent experiments. (g) PdgfbiCreER T2; PTENflox/flox mECs were infected with PTENWT, PTENC124S or PTENK13,289E, treated with 4-OHT for 72 h, plated for 48 h in the presence of doxycycline, pulsed with BrdU for 2 h and subjected to immunostaining analysis. Data shown are the means of six independent experiments. Error bars are s.e.m. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed by nonparametric Mann–Whitney test.

To investigate whether increased levels of the APC/C-Fzr1/Cdh1 targets were only a consequence of increased PI3K activity, we tested the impact of GDC-0941 (a pan-class I PI3K inhibitor that blocks p110α, p110β, p110δ and p110γ; ref. 31). While pretreatment with GDC-0941 abrogated Akt activation in PTENiΔEC/iΔEC mECs (Fig. 5e), it did not modify the levels of Aurora A and Geminin (Fig. 5e), further corroborating that the function of PTEN promoting the APC/C-Fzr1/Cdh1 activity is independent of its ability to inhibit PI3K signalling through its lipid phosphatase activity22.

As our data indicate that the principal function of PTEN in sprouting angiogenesis is to regulate EC proliferation, we tested to what extent phosphatase-dependent and -independent activities of PTEN participate in this regulation. In vitro isolated PTENiΔEC/iΔEC and PTENTG mECs showed increased and decreased BrdU incorporation, respectively (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 6a,b). Inhibition of PI3K activity and Aurora kinase, one of the main targets of APC/C-Fzr1/Cdh1 (ref. 22), partially rescued normal proliferation rate in PTENiΔEC/iΔEC mECs (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 6a). A synergistic effect was observed on pretreatment with both GDC-0941 and VX680, further implying a dual function of PTEN in this process. Next, we complemented PTEN-depleted ECs with either WT (PTENWT), phosphatase-inactive (C124S; PTENC124S; refs 32, 33) or nuclear-excluded (K13,289E; PTENK13,289E) PTEN (ref. 22). Expression of PTENWT, PTENC124S and PTENK13,289E abrogated the increase in EC proliferation (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 6c) of PTEN null ECs, albeit most prominently seen with PTENWT. All together, these data indicate that phosphatase-dependent and -independent activities of PTEN are important to regulate EC proliferation.

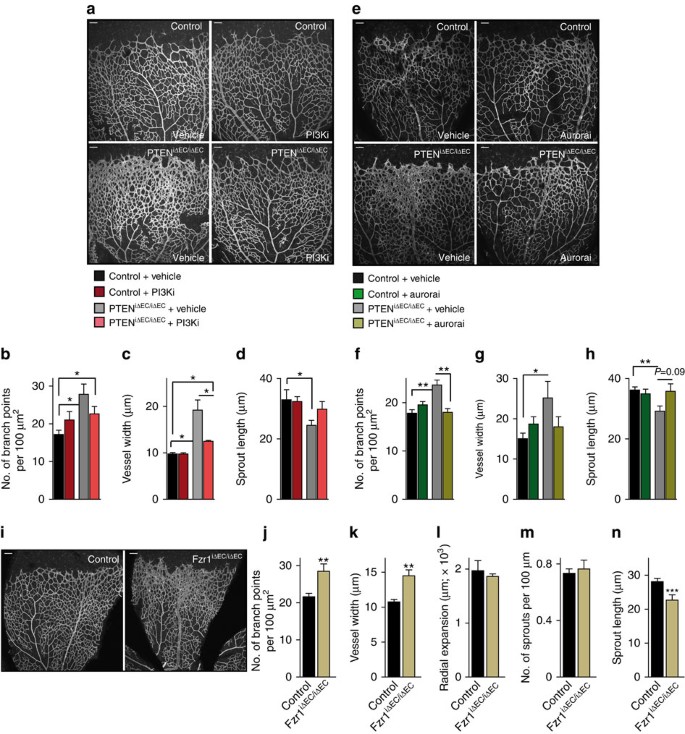

Next, we tested the differential contribution of each of these functions in vivo, by first analysing the retinas of PTENiΔEC/iΔEC on inhibition of class I PI3K activity with GDC-0941. The hyperplasia induced by PTEN loss was rescued by inhibiting PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 production (Fig. 6a–d and Supplementary Fig. 7a), indicating, as expected, an important role of PTEN lipid phosphatase activity in vascular growth. Next, we assessed the contribution of phosphatase-independent activity of PTEN to sprouting angiogenesis by inhibiting Aurora kinase. Strikingly, the phenotype of PTENiΔEC/iΔEC was abrogated by Aurora kinase inhibition (Fig. 6e–h), which is consistent with the contribution of the phosphatase-independent activity of PTEN to sprouting angiogenesis in vivo. This was further corroborated by genetic conditional and inducible deletion of Fzr1 in ECs. Complete depletion of Fzr1/Cdh1 protein was achieved 48 h post incubation with 4-OHT (Supplementary Fig. 7b,c). Therefore, pups were treated with 4-OHT at P5 and P6, followed by analysis of the retinal vasculature at P7. The retinas of Fzr1iΔEC/iΔEC showed increased vascular density and reduced length of sprouts (Fig. 6i–n) comparable to PTENiΔEC/iΔEC. All together, these data suggest that, in ECs, there is a dual contribution of PTEN, counterbalancing the PI3K signalling pathway through its lipid phosphatase activity and facilitating the APC/C-Fzr1/Cdh1 complex activity, which has been reported to be independent of its catalytic function22.

Figure 6: Dual function of PTEN in sprouting angiogenesis.

(a) IB4-stained control and PTENiΔEC/iΔEC P7 retinas (4-OHT administration from P1 to P2) treated with vehicle or GDC-0941 at P6 and P7. (b–d) Quantitative analysis of the retinas shown in a. (b) Vascular branch points per unit area (_n_≥4). (c) Vessel width (_n_≥4). (d) Sprout length from the tip to the base of the sprout (_n_≥4). (e) IB4-stained control and PTENiΔEC/iΔEC P7 retinas (4-OHT administration from P1 to P2) treated with vehicle or VX680 at P6 and P7. (f–h) Quantitative analysis of the retinas shown in e. (f) Vascular branch points per unit area (_n_≥6). (g) Vessel width (_n_≥6). (h) Sprout length from the tip to the base of the sprout (_n_≥6). (i) Overview of P7 control and Fzr1iΔEC/iΔEC iB4-stained. (j–n) Quantitative analysis of the retinas shown in i. (j) Vascular branch points per unit area (_n_=11). (k) Vessel width (_n_=11). (l) Radial expansion of blood vessels (_n_≥5). (m) Number of sprouts per vascular front length (_n_=11). (n) Sprout length from the tip to the base of the sprout (_n_=6). Scale bars, 100 μm (a,e,i). Error bars are s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed by nonparametric Mann–Whitney test.

Discussion

Here we report that PTEN in ECs is required in a cell-autonomous and dose-dependent manner for the control of vascular density and vessel growth, but is dispensable for the regulation of the sprouting activity of tip cells. We show that endothelial PTEN restricts vascular growth by limiting stalk cell proliferation during sprouting angiogenesis. An important conclusion from this study is that PTEN is not required in all ECs to regulate proliferation in vivo, as shown in cultured ECs (our data and ref. 19). Instead, our results indicate that the consequence of PTEN loss or overexpression in vivo is restricted specifically to the zone of the vasculature that is highly Notch-dependent.

Constitutive targeting of PTEN in ECs leads to embryonic lethality due to aberrant angiogenesis19. Although these studies have established that PTEN regulates EC proliferation, the analysis of vasculature in Tie2Cre-PTENflox/flox embryos did not allow unravelling precisely how PTEN regulates sprouting angiogenesis. Furthermore, Hamada et al. were unclear of whether the aberrant vasculature, which results on PTEN loss, was a consequence of aberrant PTEN signalling in ECs or simply a consequence of an altered pro-angiogenic cytokine profile19. Similarly, zebrafish studies have shown that loss of PTEN leads to increased VEGF levels and in turn vessel hyperplasia, highlighting indeed that PTEN also regulates angiogenesis in a paracrine manner20. Another difference between Hamada et al. and our study is that constitutive loss of PTEN in ECs also results in altered mural cell coverage, while induced loss of postnatal endothelial PTEN does not. These discrepancies suggest that PTEN may differently regulate angiogenesis in different vascular beds.

Activation of Notch leads to cell cycle arrest8,9,10,11,34. In this study, we identify PTEN as a critical mediator of Notch antiproliferative response in stalk cells. If PTEN is not expressed in ECs, stalk cells become insensitive to the antiproliferative signals of Notch and exhibit unrestricted expansion, hence perturbing sprout length and pattern and eventually resulting in profound hyperplasia. Interestingly, our results also reveal that stalk cells located further away from the front are insensitive to changes in PTEN expression. Given that these stalk cells at the subfront area are highly proliferative, our data support the existence of two biological states for stalk cells. A first state in which stalk cells must remain arrested to ensure the correct patterning of the sprout, and a second state in which cells enter the cell cycle to expand the plexus. These two states are likely the consequence of dynamic changes in Notch signalling, with high Notch activity in early nonproliferative stalk cells and low Notch activity in the late proliferative stalk cells. Our data predict a rise and fall in PTEN levels that will accompany the early quiescent and late proliferative phases, respectively. This is supported by the observation that, in WT cultured ECs, higher PTEN levels are seen 8 h post stimulation with Dll4 compared with 24 h post stimulation. Furthermore, co-staining of PTEN and 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (Edu) in the growing vasculature showed that Edu-negative cells express higher levels of PTEN than Edu-positive cells, supporting the notion that PTEN protein levels rise to guarantee cell cycle arrest. Whether high PTEN cells correspond to high Notch signalling still needs to be determined. Moya et al. speculated that early and late stalk cell behaviours might be orchestrated by oscillation in Notch activity. The authors proposed that Id proteins, members of HLH proteins, govern these two states by releasing the negative autoregulatory loop of Hes1 (ref. 35). While our results are consistent with the idea of two states, they identify PTEN as the key mediator of early stalk cell function in response to Notch.

Why and how Notch exerts a unique negative regulation in the endothelium while driving proliferation in virtually every other cell type and in cancer has been a mystery5,36. Our data show that PTEN negatively regulates cell cycle progression in ECs through conserved pathways. Critically, what our results illustrate is a novel interaction between Notch and PTEN in ECs. We find that Notch stimulates PTEN transcription in the endothelium, an effect that is required for Notch-mediated cell cycle arrest. Interestingly, in cell types where Notch stimulates cell cycle progression, PTEN is transcriptionally repressed by Notch/Hes36,37,38. The PTEN gene locus contains both Rbpj- and Hes-binding sites, suggesting that binding to one or another is what determines the final biological output.

In line with the observation that PTEN restricts stalk cell proliferation, endothelial gain and loss of PTEN proliferation phenotypes are reminiscent of gain and loss of Notch function in stalk cells9,10,11. However, in response to Notch signalling PTEN appears to only regulate EC proliferation while it is not required for tip and stalk specification. This is shown by the observation that Notch mutants not only show aberrant proliferation phenotypes in the nascent plexus but also sprouting defects9,11, while PTEN mutants only show vascular density defects. In the same line, increased levels of PTEN protect angiogenic ECs treated with DAPT from uncontrolled proliferation but fail to prevent excessive tip cell numbers. Conversely, a recent study has shown that inhibitors of the VEGFR3 kinase activity rescue the hypersprouting phenotype of Notch loss-of-function mutants, without reducing EC proliferation39. Taken together, these data suggest that Notch regulates tip cell numbers and stalk cell proliferation independently through VEGFR3 and PTEN pathways, respectively.

The predominant activity of PTEN is the dephosphorylation of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and thus the counteraction of class I PI3K-mediated functions13,15. However, PTEN also exhibits PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-independent functions, including protein phosphatase14 and non-catalytic activities13,15. In this context, PTEN can be found in the nucleus where it regulates DNA stability and cell cycle progression22,40. Several reports have highlighted the relevance of nuclear PTEN in disease22,41,42,43. To date, the physiological relevance of nuclear PTEN in vivo remains elusive. Our results reveal that both lipid phosphatase-dependent and non-catalytic activities of PTEN regulate stalk cell proliferation during sprouting angiogenesis. Inhibition of class I PI3K activity with GDC-0941 or Aurora kinase with VX680 significantly abrogates the phenotype observed on PTEN loss. However, the observation that pretreatment with either GDC-0941 or VX680 is not able to completely rescue the hyperplasia phenotype of PTENiΔEC/iΔEC retinas and cultured ECs indicates that both types of activities of PTEN are required to drive the PTEN response in angiogenesis. Furthermore, genetic deletion of Fzr1 in ECs recapitulates the phenotype observed on endothelial loss of PTEN, reinforcing the relevance of nuclear PTEN facilitating the APC/C-Fzr1/Cdh1 function. Taken together, our study provides in vivo evidence that nuclear PTEN is not only involved in disease such as cancer or cerebral ischaemia22,41,42,43 but is also critical to regulate a fundamental physiological process such as angiogenesis.

We and others have previously shown that inhibition of class I PI3K isoform in vivo does not lead to blockade of EC proliferation29,44,45,46. Although contradictory, these observations may reflect that PTEN principally regulates EC proliferation independently of its lipid phosphatase activity22. In line with this, our data also reveal that the regulation of APC/C-Fzr1/Cdh1 by PTEN seems to play a major role in response to Notch signalling in angiogenesis. This is shown by the altered APC/C-Fzr1/Cdh1 target expression under conditions of PTEN loss and Notch activation. This observation, together with the fact that Notch stimulation in ECs results in phosphorylation of Akt47,48, suggest that Notch stimulates PTEN nuclear translocation. These findings would be in agreement with the notion that higher nuclear PTEN levels are found during G0–G1 phase than during the S phase23,24. Further experiments are needed to elucidate how PTEN accumulates in the nucleus on Notch activation.

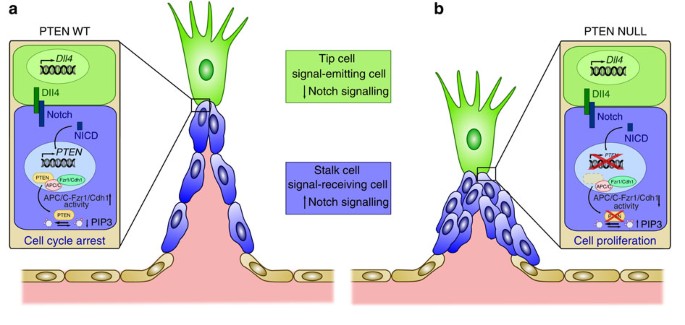

The unique direction of the coupling of Notch and PTEN in the endothelium (Fig. 7), and the highly selective effects on the active vascular front raise the prospect that targeting this interaction and stimulation of PTEN signalling may be used therapeutically to render EC quiescence in aberrant tumour angiogenesis and in turn promote a normalization effect. Clinically, our results imply that stimulating both arms of PTEN function in ECs could render a more quiescence phenotype of highly proliferative tumour ECs2,49. However, inhibition of PI3K in the tumour stroma not only results in reduced EC proliferation but also in reduced vascular function47. It is thus tempting to speculate that promoting nuclear PTEN may offer more selectivity towards a tight control of EC proliferation.

Figure 7: Schematic model of the role of PTEN in Dll4/Notch-mediated stalk cell cycle arrest.

(a) Activation of Notch by Dll4 induces expression of PTEN, which through its lipid phosphates activity and its nuclear function as a scaffold of the APC/C-Fzr1/Cdh1 blocks stalk cell proliferation. (b) On PTEN loss, Notch signalling fails to arrest stalk cells and result in defective sprout length and patterning.

Methods

Reagents

Sources and catalogue numbers of antibodies were as follows: Cell Signaling Technology: PTEN (#9559), pS473-Akt (#4060) and pSer240/244-S6 (#2215); BD Pharmingen: p27 (#610242), cyclin-D1 (#556470), BrdU (#347580) and Aurora A Kinase (#610939); NeoMarkers: Ki67 (#RM-9106-S); Abcam: NICD (#ab27526), desmin (ab15200) and PTEN (ab32199); Santa Cruz Biotechnology: VE-cadherin (sc-6458), Geminin (#sc-13015), cyclin-A (#sc-53230), Hes1 (#sc-25392) and Erg (sc-353); Millipore: Plk1 (#06-813) and Fzr1/Cdh1 (#CC43); Sigma-Aldrich: β-actin (A5441) and α-tubulin (T6074). Isolectin GS-IB4 and secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa 488, Alexa 568 and Alexa 633, and Click-iT EdU Alexa 488 and 647 Imaging Kit were from Molecular Probes. Human (#1506-D4) and mouse Dll4 (#1389-D4) were from R&D Systems. The GDC-0941 compound was from Chem Express Haoyuan (China). The VX680 (MK-0457) compound was from Selleckchem (USA). All chemicals, unless otherwise stated, were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Inducible genetic protocols and pharmacological inhibition in mice

Mice were kept in individually ventilated cages and cared for according to the guidelines and legislation of the UK Home Office and Catalan Departament d’ Agricultura, Ramaderia i Pesca, with procedures accepted by the Ethics Committees of CRUK-London Research Institute and IDIBELL-CEEA.

To delete PTEN in postnatal vessels, we crossed the PTENflox mice50 into the transgenic mice expressing the tamoxifen-inducible recombinase CreERT2 under the control of the endothelial Pdgfb promoter26. To generate PdgfbiCreER T2; PTENflox/flox and PTENflox/flox littermates, PdgfbiCreER T2; PTENflox/flox were interbred with PTENflox/flox. Cre activity and gene deletion were induced by intraperitoneal injection of 25 μg 4-OHT (Sigma, H7904 10 mg ml−1) in all pups of the litter at P1 and P2, and retinas were collected at different time points (P5, P7 and P10). Class I PI3K signalling or Aurora kinase was inhibited in half of the pups by subcutaneous injection at 18:00 pm of P6 and 10:00 am of P7 with 37.5 μg g−1 GDC-0941 (ref. 31) or with 50 μg g−1 VX680, respectively, dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO). Retinas were harvested at 18:00 pm of P7. Control mice were injected with DMSO only.

PTENTG (ref. 28) was maintained in C57/BL6 background and were fed with a 19% protein-extruded rodent diet (Harlan, 2019) in a 1:1 proportion with normal diet. Notch signalling was inhibited in half of the pups by subcutaneous injection at P5 and P6, with 100 mg kg−1 DAPT (Calbiochem, #565770) and retinas being harvested at P7.

PdgfbiCreER T2; Fzr1flox/flox were interbred with Fzr1flox/flox (ref. 51) to generate PdgfbiCreER T2; Fzr1flox/flox and Fzr1flox/flox littermates. Pups were injected with 25 μg 4-OHT (10 mg ml−1) at P5 and P6 and dissected at P7.

For combined endothelial-cell-specific loss-of-function of PTEN and Jag1, we crossed PTENflox/flox (ref. 50) with Jagged1flox/flox (ref. 52) and PdgfbiCreER T2 (ref. 26). To generate PdgfbiCreER T2; PTENflox/flox; Jag1flox/flox (PTENiΔEC/iΔEC; Jag1iΔEC/iΔEC), PdgfbiCreER T2; PTENflox/flox (PTENiΔEC/iΔEC) and PdgfbiCreER T2; Jag1flox/flox (Jag1iΔEC/iΔEC) littermates, two different types of breeding were set up; PdgfbiCreER T2; PTENflox/flox; Jag1flox/flox were interbred with PTENflox/flox; Jag1flox/WT or with PTENflox/WT; Jag1flox/flox. Cre activity and gene deletion were induced by intraperitoneal injection of 25 μg 4-OHT (10 mg ml−1) in all pups of the litter, at P1 and P3 and retinas were collected at P7. To assess proliferating ECs, the pups were injected intraperitoneally with 60 μl of Edu (0.5 μg−1 μl−1) 2 h before being killed. Edu was dissolved in a 1:1 ratio DMSO:PBS.

Immunofluorescence

Eyes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehye (PFA) for 2 h at 4 °C. For PTEN staining, mice were exsanguinated by transcardiac perfusion of PBS, followed by perfusion with 4% PFA before dissecting and continuing fixing the retinas with methanol at −20 °C. Samples were rehydrated for 30 min at room temperature (RT). After washing twice in PBS, retinas were permeabilized in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.3% Triton X-100 overnight (ON) at 4 °C, followed by incubation with primary antibodies (PTEN (Abcam; 1:75), pSer240/244-S6 (1:100), Erg (1:200), desmin (1:200), Hes1 (1:50) and Ki67 (1:50) in permeabilization buffer ON at 4 °C. The following day, the eyes were washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween (PBT), one time in Pblec buffer (1% Triton X-100, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM MnCl2 in PBS, pH 6.8) for 30 min and then incubated for 2 h at RT or ON at 4 °C in Pblec buffer containing Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:200) and IB4 (1:300), washed three times further with PBT and flat-mounted on microscope glass slides with Mowiol. For fixed confocal laser scanning microscopy, we use a Leica SP5. Images were analysed with Image J Software and Adobe Photoshop CS5.

Embryoid bodies

ES cells were cultured and EBs were generated, as previously described27. Briefly, ES cells were regularly cultured on a layer of irradiated DR4 mouse embryonic fibroblast in DMEM glutamax (Life Technologies, #61965-026) in the presence of 20% fetal bovine serum, HEPES (30 mM), sodium pyruvate (1.5 mM), monothioglycerol (1.5%) and leukaemia inhibitory factor (Chemicon#ESG1107, 123 units ml−1). For vascular sprouting assays, cells were cultured for two passages without feeders, depleted of leukaemia inhibitory factor and left in suspension as hanging drops. Four days after, the formed EBs were transferred to a polymerized collagen I gel with the addition of 60 ng ml−1 VEGF (Peprotech). The medium was changed on day 6 and every day thereafter. Overall, 70,000 WT ES cells and 10,000 PTEN−/− ES cells were plated to generate EB. PTEN−/− ES cells were provided in ref. 53.

Isolation and stimulation of mECs

Mouse lungs were digested with Dispase (Life Technologies, #17105-041; 4 units ml−1) for 1 h at 37 °C, followed by positive selection with antimouse vascular endothelial-cadherin (Pharmingen, #555289) antibody coated with magnetic beads (Dynal Biotech, #110-35). Cells were seeded on a 12-well plate, and were coated with gelatin (0.5%) in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum and EC growth factor (PromoCell, #C30140). After the first passage, the cells were re-purified with vascular endothelial-cadherin antibody-coated magnetic beads. Cells were cultured until passage 6. To induce gene deletion, 4-OHT (5 μM) or vehicle (ethanol) was added to the cultured medium at P4 for 96 h and the medium was replaced every other day. For Dll4 stimulation, mouse Dll4 (500 μg ml−1) was immobilized by coating culture dishes for 1 h at RT, followed by seeding mECs for 6, 8 or 24 h. Mouse and human Dll4 were used accordingly.

In vitro measurement of mEC cell proliferation

Overall, 104 mECs were plated in a 24-well plate for 48 h; 2 h before the termination of the experiment, BrdU (10 μM) was added to the medium. For Ki67 staining, cells were plated for 24 h in Dll4-coated dishes. Cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min at RT, permeabilized for 10 min with TBS-T (25 mM Tris HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100), blocked with TBS-T containing 2% BSA and incubated with primary antibodies BrdU (1:100) or Ki67 (1:50) at 4 °C ON. The following day, cells were washed three times with TBS-T and incubated with Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h at RT. DAPI was added in the final wash. Specimens were mounted in Mowiol. Cells were visualized in a Nikon-80I microscope. For pharmacological inhibition of class I PI3K and Aurora kinase, GDC-0941 (1 μM) and VX680 (0.5 μM) were added, respectively, on plating.

Plasmids and transfections

pRK5-Myc-PTEN, C124S pEGFP-PTEN-wt and pEGFP-PTEN-K13,289E expressing human WT, lipid phosphatase-inactive and nuclear-excluded PTEN mutants, respectively, were provided in ref. 22. All three PTEN mutants were subcloned with an N-terminal yellow fluorescent protein into a modified lentiviral vector TRIPZ. Lentiviral particles were prepared by transfecting HEK293FT cells with the TRIPZ vector of interest and the packaging vectors psPAX, VSV-G and pTAT. Viral particles in the supernatant were concentrated with Lenti-X-concentrator (Clontech). mECs of P2 or P3 from PdgfbiCreERT2; PTENflox/flox were infected with lentivirus expressing WT PTEN, PTEN (C124S) or PTEN (K13,289E) in the presence of viralplus transduction enhancer (Applied Biological Material #G698). For infection, mECs were plated at a density of 4 × 104 per well of 12-well plate and infected with virus from 293FT cells 48 h after transfection. After 48 h post infection, mECs were re-plated and treated with 4-OHT (5 μM) to induce gene deletion for 72 h. Next, 104 mECs were plated in 24-well plate for 48 h in the presence of doxycycline (4 μM); 2 h before the termination of the experiment, BrdU (10 μM) was added to the medium. Cells were then fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min at RT, permeabilized for 10 min with TBS-T (25 mM Tris HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100), blocked with TBS-T containing 2% BSA and incubated with primary antibodies BrdU (1:100) at 4 °C ON. The following day, cells were washed three times with TBS-T and incubated with Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h at RT. DAPI was added in the final wash. Specimens were mounted in Mowiol. Cells were visualized in a Nikon-80I microscope.

MTS viability assay

mECs were cultured in 96-well plate (2,000 cells per 100 μl culture medium per well) in the presence of the test compounds (GDC-0941 (1 μM) and VX680 (0.5 μM)) or the respective controls for 48 h, followed by MTS assay (Promega, #G5421).

Protein extraction and immunoblotting

mECs, human umbilical vascular ECs (HUVECs (Lonza #CC-2519)) and lungs were lysed in 50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.4, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF and 1% Triton X-100 supplemented with 2 mg ml−1 aprotinin, 1 mM pepstatin, 1 ng ml−1 leupeptin, 1 mM phenylmethysulfonylfluoride and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, followed by clearance of lysates using microcentrifugation. Supernatants were resolved on a 10% SDS–PAGE gel, transferred on nitrocellulose membranes and probed with the indicated antibodies. Detection was performed by enhanced chemiluminescence. Uncropped immunoblots and larger blot areas are presented in Supplementary Fig. 8.

qPCR analysis

qPCR was performed using the following proprietary TaqMan Gene Expression assay FAM/TAMRA primers (Applied Biosystems): Dll4 (Mm00446968_m1), Hes1 (Mm01342805_m1), Hey1 (Mm00468865_m), Nrarp (Mm00482529_m1), Ephb4 (Mm00438750_m1), Efnb2 (Mm01215897_m1), Nr2f2 (Mm00772789_m1) and Hprt (Mm00446968_m1). The levels of PTEN mRNA were measured using SYBR Green I Master (Roche, #04.887.352.001) in the LightCycler480 system. Primers used are as follow: forward (5′-GTTTACCGGCAGCATCAAAT-3′) and reverse (5′-CCCCCACTTTAGTGCAC-3′).

Luciferase assays

Reporter assays in HUVECs were performed with the Dual Luciferase Assay System (Promega, #E1910) and a LUMAT LB 9507 luminometer (BERTHOLD Technologies). HUVECs were grown to 60–70% confluence in endothelial basal medium (EGM; Lonza #CC-3124) and co-transfected (Trans Pass V Reagents (New England Biolabs, # M2558S)) with V5-NICD (ref. 54), PTEN-luciferase reporter (pGL3 PTEN HindIII-NotI) construct37 and the constitutive Renilla luciferase reporter pGL4.74hRluc/TK (Promega). Twenty-four hours after, HUVECs were lysed and reporter assays performed according to the manufacturers’ protocol. To induce Notch activity with Dll4, transfected HUVECs were re-plated on Dll4-coated dishes 6 h after plasmid infection. Luciferase activity was measured after an additional 24 h. To inhibit Notch signalling, cells were pretreated for at least 1 h before stimulating with Dll4 with 0.08 μM DBZ ((S,S)-2-[2-(3,5-Difluorophenly)acetylamino]-N-(5-methyl-6-oxo-6,7-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[b,d]azepin-7-yl)propionamide).

ChiP assay

To analyse the binding sites for RBPJ located in the PTEN proximal promoter, we used the Genomatix software. For analysis, the gene bank sequence used was NG_007466.2, which contains the promoter sequence AF406618.1. Three putative RBPJ-binding sites located at −1,914, −1,492 and −1,132 positions relative to transcription initiation site37 were identified. ChiP assay was performed as previously described55. Briefly, chromatin was isolated from HUVECs stimulated for 2 h with vehicle or Dll4 (500 ng ml−1). Crosslinked chromatin was sonicated for 10 min, to medium-sized powder particles, at 0.5-min intervals, with a Bioruptor (Diagenode) and precipitated with anti-NCID or control IgG. After crosslinkage reversal, DNA was used as a template for PCR. qPCR was performed with SYBR Green I Master (Roche, #04.887.352.001) in the LIghtCycler480 system. Primers used are described in Supplementary Table 1.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Serra, H. et al. PTEN mediates Notch-dependent stalk cell arrest in angiogenesis. Nat. Commun. 6:7935 doi: 10.1038/ncomms8935 (2015).

References

- Adams, R. H. & Alitalo, K. Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 464–478 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Potente, M., Gerhardt, H. & Carmeliet, P. Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell 146, 873–887 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ruhrberg, C. et al. Spatially restricted patterning cues provided by heparin-binding VEGF-A control blood vessel branching morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 16, 2684–2698 (2002).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Gerhardt, H. et al. VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J. Cell Biol. 161, 1163–1177 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Blanco, R. & Gerhardt, H. VEGF and Notch in tip and stalk cell selection. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 3, a006569 (2012).

Google Scholar - Roca, C. & Adams, R. H. Regulation of vascular morphogenesis by Notch signaling. Genes Dev. 21, 2511–2524 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Phng, L. K. & Gerhardt, H. Angiogenesis: a team effort coordinated by notch. Dev. Cell 16, 196–208 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Noseda, M. et al. Notch activation induces endothelial cell cycle arrest and participates in contact inhibition: role of p21Cip1 repression. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 8813–8822 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hellstrom, M. et al. Dll4 signalling through Notch1 regulates formation of tip cells during angiogenesis. Nature 445, 776–780 (2007).

Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar - Phng, L. K. et al. Nrarp coordinates endothelial Notch and Wnt signaling to control vessel density in angiogenesis. Dev. Cell 16, 70–82 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Benedito, R. et al. The notch ligands Dll4 and Jagged1 have opposing effects on angiogenesis. Cell 137, 1124–1135 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Benedito, R. & Hellstrom, M. Notch as a hub for signaling in angiogenesis. Exp. Cell Res. 319, 1281–1288 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Song, M. S., Salmena, L. & Pandolfi, P. P. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 283–296 (2013).

Article Google Scholar - Leslie, N. R., Maccario, H., Spinelli, L. & Davidson, L. The significance of PTEN's protein phosphatase activity. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 49, 190–196 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hopkins, B. D., Hodakoski, C., Barrows, D., Mense, S. M. & Parsons, R. E. PTEN function: the long and the short of it. Trends Biochem. Sci. 39, 183–190 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Cantley, L. C. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science 296, 1655–1657 (2002).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Vanhaesebroeck, B., Guillermet-Guibert, J., Graupera, M. & Bilanges, B. The emerging mechanisms of isoform-specific PI3K signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 329–341 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hawkins, P. T., Anderson, K. E., Davidson, K. & Stephens, L. R. Signalling through Class I PI3Ks in mammalian cells. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34, 647–662 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hamada, K. et al. The PTEN/PI3K pathway governs normal vascular development and tumor angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 19, 2054–2065 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Choorapoikayil, S., Weijts, B., Kers, R., de Bruin, A. & den Hertog, J. Loss of Pten promotes angiogenesis and enhanced vegfaa expression in zebrafish. Dis. Model Mech. 6, 1159–1166 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lindsay, Y. et al. Localization of agonist-sensitive PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 reveals a nuclear pool that is insensitive to PTEN expression. J. Cell Sci. 119, 5160–5168 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Song, M. S. et al. Nuclear PTEN regulates the APC-CDH1 tumor-suppressive complex in a phosphatase-independent manner. Cell 144, 187–199 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Whiteman, D. C. et al. Nuclear PTEN expression and clinicopathologic features in a population-based series of primary cutaneous melanoma. Int. J. Cancer 99, 63–67 (2002).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ginn-Pease, M. E. & Eng, C. Increased nuclear phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 is associated with G0-G1 in MCF-7 cells. Cancer Res. 63, 282–286 (2003).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Manchado, E., Eguren, M. & Malumbres, M. The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C): cell-cycle-dependent and -independent functions. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38, 65–71 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Claxton, S. et al. Efficient, inducible Cre-recombinase activation in vascular endothelium. Genesis 46, 74–80 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Jakobsson, L. et al. Heparan sulfate in trans potentiates VEGFR-mediated angiogenesis. Dev. Cell 10, 625–634 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ortega-Molina, A. et al. Pten positively regulates brown adipose function, energy expenditure, and longevity. Cell Metab. 15, 382–394 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Graupera, M. et al. Angiogenesis selectively requires the p110alpha isoform of PI3K to control endothelial cell migration. Nature 453, 662–666 (2008).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Armulik, A., Genove, G. & Betsholtz, C. Pericytes: developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Dev. Cell 21, 193–215 (2010).

Article Google Scholar - Edgar, K. A. et al. Isoform-specific phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors exert distinct effects in solid tumors. Cancer Res. 70, 1164–1172 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Nelen, M. R. et al. Germline mutations in the PTEN/MMAC1 gene in patients with Cowden disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6, 1383–1387 (1997).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wang, H. et al. Allele-specific tumor spectrum in pten knockin mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 5142–5147 (2010).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Siekmann, A. F. & Lawson, N. D. Notch signalling limits angiogenic cell behaviour in developing zebrafish arteries. Nature 445, 781–784 (2007).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Moya, I. M. et al. Stalk cell phenotype depends on integration of Notch and Smad1/5 signaling cascades. Dev. Cell 22, 501–514 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Bertrand, F. E., McCubrey, J. A., Angus, C. W., Nutter, J. M. & Sigounas, G. NOTCH and PTEN in prostate cancer. Adv. Biol. Regul. 56, 51–65 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Palomero, T. et al. Mutational loss of PTEN induces resistance to NOTCH1 inhibition in T-cell leukemia. Nat. Med. 13, 1203–1210 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wong, G. W., Knowles, G. C., Mak, T. W., Ferrando, A. A. & Zuniga-Pflucker, J. C. HES1 opposes a PTEN-dependent check on survival, differentiation, and proliferation of TCRbeta-selected mouse thymocytes. Blood 120, 1439–1448 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Benedito, R. et al. Notch-dependent VEGFR3 upregulation allows angiogenesis without VEGF-VEGFR2 signalling. Nature 484, 110–114 (2012).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Shen, W. H. et al. Essential role for nuclear PTEN in maintaining chromosomal integrity. Cell 128, 157–170 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Trotman, L. C. et al. Ubiquitination regulates PTEN nuclear import and tumor suppression. Cell 128, 141–156 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Howitt, J. et al. Ndfip1 regulates nuclear Pten import in vivo to promote neuronal survival following cerebral ischemia. J. Cell Biol. 196, 29–36 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Freeman, D. J. et al. PTEN tumor suppressor regulates p53 protein levels and activity through phosphatase-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Cancer Cell 3, 117–130 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Herbert, S. P. et al. Arterial-venous segregation by selective cell sprouting: an alternative mode of blood vessel formation. Science 326, 294–298 (2009).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Nicoli, S., Knyphausen, C. P., Zhu, L. J., Lakshmanan, A. & Lawson, N. D. wmiR-221 is required for endothelial tip cell behaviors during vascular development. Dev. Cell 22, 418–429 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Graupera, M. & Potente, M. Regulation of angiogenesis by PI3K signaling networks. Exp. Cell Res. 319, 1348–1355 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Soler, A. et al. Inhibition of the p110alpha isoform of PI 3-kinase stimulates nonfunctional tumor angiogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 210, 1937–1945 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wustehube, J. et al. Cerebral cavernous malformation protein CCM1 inhibits sprouting angiogenesis by activating DELTA-NOTCH signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 12640–12645 (2010).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Carmeliet, P. & Jain, R. K. Principles and mechanisms of vessel normalization for cancer and other angiogenic diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10, 417–427 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Suzuki, A. et al. T cell-specific loss of Pten leads to defects in central and peripheral tolerance. Immunity 14, 523–534 (2001).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Garcia-Higuera, I. et al. Genomic stability and tumour suppression by the APC/C cofactor Cdh1. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 802–811 (2008).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Brooker, R., Hozumi, K. & Lewis, J. Notch ligands with contrasting functions: Jagged1 and Delta1 in the mouse inner ear. Development 133, 1277–1286 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Di Cristofano, A., Pesce, B., Cordon-Cardo, C. & Pandolfi, P. P. Pten is essential for embryonic development and tumour suppression. Nat. Genet. 19, 348–355 (1998).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Guarani, V. et al. Acetylation-dependent regulation of endothelial Notch signalling by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Nature 473, 234–238 (2011).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Guiu, J. et al. Hes repressors are essential regulators of hematopoietic stem cell development downstream of Notch signaling. J. Exp. Med. 210, 71–84 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank Ramon Parsons (The Mount Sinai Hospital, NY, US) for pGL3 PTEN HindIII-NotI construct and Lluis Espinosa (IMIM, Barcelona), Alba Martinez (Research Laboratory, Catalan Institute of Oncology, IDIBELL, Barcelona) and Magali Castells (Vascular Signalling laboratory, IDIBELL) for support with experiments. This work was supported by research grants SAF2010-15661 and SAF2013-46542-P from MICINN (Spain), 2014-SGR-725 from the Catalan Government, from the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007-2013/ (REA grant agreement 317250) and Ajuts Joves Investigadors from IDIBELL to M.G., and SAF2013-40922 and RD12/0036/0054 to A.B. Personal support was from FPI of the Spanish Ministry of Education (A.S.), IDIBELL (H.S.) and Ramon y Cajal fellow of the Spanish Ministry of Education (M.G. and O.C.). The work of A.C. is supported by the Ramón y Cajal award, the Basque Department of Industry, Tourism and Trade (Etortek), health (2012111086) and education (PI2012-03), Marie Curie (277043), Movember, ISCIII (PI10/01484, PI13/00031) and ERC (336343). The work of M.P. is supported by the Max Planck Society, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 834) and an ERC Starting Grant (ANGIOMET). H.G. is supported by Cancer Research UK, the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine, the Leducq Network Grant ARTEMIS, BIRAX and an ERC starting grant Reshape 311719.

Author information

Author notes

- Helena Serra and Iñigo Chivite: These authors contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

- Vascular Signalling Laboratory, Institut d'Investigació Biomèdica de Bellvitge (IDIBELL), Gran Via de l’Hospitalet 199-203, 08908 L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain,

Helena Serra, Iñigo Chivite, Ana Angulo-Urarte, Adriana Soler & Mariona Graupera - CIC-bioGUNE, Technology Park of Bizkaia, Derio, 48160, Bizkaia, Spain

James D. Sutherland, Amaia Arruabarrena-Aristorena & Arkaitz Carracedo - Vascular Biology Laboratory, London Research Institute-Cancer Research UK, London, WC2A 3LY, UK

Anan Ragab & Holger Gerhardt - Max Planck Institute for Heart and Lung Research, Bad Nauheim, D61231, Germany

Radiance Lim & Michael Potente - Spanish National Cancer Research Center (CNIO), Madrid, 28029, Spain

Marcos Malumbres & Manuel Serrano - UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, University Collage of London, London, EC1V9EL, UK

Marcus Fruttiger - Centre d’Oncologia Molecular, IDIBELL, Universitat de Barcelona, 08907 L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona,,

Àngels Fabra - Translation Research Laboratory, Catalan Institute of Oncology, IDIBELL, Universitat de Barcelona, 08907 L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain,

Francesc Viñals & Oriol Casanovas - Departament de Ciències Fisiològiques II, Universitat de Barcelona, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, 08907, Spain

Francesc Viñals - Department of Medicine and Pathology, Cancer Research Institute, Beth Israel Deaconess Cancer Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, 02115, Massachusetts, USA

Pier Paolo Pandolfi - Program in Cancer Research, Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute (IMIM), Barcelona Biomedical Research Park, 08003, Barcelona, Spain

Anna Bigas - IKERBASQUE, Basque Foundation of Science, Bilbao, 48011, Bizkaia, Spain

Arkaitz Carracedo - Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), Bilbao, 48940, Spain

Arkaitz Carracedo - Max-Delbrueck Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC), Robert-Rössle-Strasse 10, Berlin, 13125, Germany

Holger Gerhardt

Authors

- Helena Serra

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Iñigo Chivite

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ana Angulo-Urarte

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Adriana Soler

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - James D. Sutherland

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Amaia Arruabarrena-Aristorena

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Anan Ragab

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Radiance Lim

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Marcos Malumbres

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Marcus Fruttiger

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Michael Potente

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Manuel Serrano

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Àngels Fabra

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Francesc Viñals

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Oriol Casanovas

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Pier Paolo Pandolfi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Anna Bigas

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Arkaitz Carracedo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Holger Gerhardt

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mariona Graupera

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

H.S., I.C., A.A.-U., J.D.S., A.S., A.A.-A., A.R., R.L. and A.F. performed experiments, H.S., I.C., A.C., M.G. and H.G. designed research, analysed data and wrote the paper; R.L., A.F., F.V., M.P., A.B. and O.C. analysed data, M.M., M.F., M.S., P.P.P. and A.B. provided reagents.

Corresponding author

Correspondence toMariona Graupera.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Serra, H., Chivite, I., Angulo-Urarte, A. et al. PTEN mediates Notch-dependent stalk cell arrest in angiogenesis.Nat Commun 6, 7935 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8935

- Received: 07 December 2014

- Accepted: 26 June 2015

- Published: 31 July 2015

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8935