Complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 full-length human cDNAs (original) (raw)

Main

Now that most of the human genomic sequence has been determined1,2,3,4,5 efforts are focused on its annotation. Full-length cDNAs, which are complete copies of mRNAs, are a particularly important resource for identifying genes and determining their structural features, forming a basis for transcriptome analysis. Physical cDNA clones are also indispensable reagents in the experimental analysis of gene functions, particularly in higher eukaryotes, such as humans.

In 1999, we started the FLJ project, which aimed to collect and determine the complete sequences of putatively full-length human cDNAs. At that time, there were only about 6,000 cDNAs in RefSeq, the curated informational resource6, with full-length cDNA sequence information. One million cDNAs clones were available from the IMAGE collection, the physical resource for cDNA clones. Unfortunately, most IMAGE clones were only partly sequenced (as expressed-sequence tags; ESTs7) and there were no good clues to indicate which ones were full-length. Therefore, we began the large-scale collection and full-length sequencing of cDNAs not only to obtain cDNA sequence information but also to provide a physical source of cDNA clones. Here, we report the first characterization of 21,243 clones.

Results

Collecting and sequencing full-length cDNAs

To facilitate the large-scale collection and sequencing of full-length cDNAs, we constructed 107 human cDNA libraries enriched for full-length cDNA clones representing 61 tissues, 21 primary cell cultures and 16 cell lines. We used a cap-targeted selection method called oligo-capping8,9 for all but one spleen library, which was constructed using a highly selective size-fractionation method to clone cDNAs of long mRNAs10. Supplementary Table 1 online shows the cDNA libraries we used. The average frequency of full-length cDNA clones in the libraries was 85%.

We randomly picked cDNA clones from these libraries and subjected them to one-pass sequencing. In total, we obtained the 5′-end one-pass sequences from 1,154,510 cDNA clones. In some cases, we compared these sequences to GenBank using BLAST searching11. We found that 40–60% of our cDNA sequences matched RefSeq entries at the time of the search. The rest matched only human ESTs or had no matches. We selected 21,243 cDNA clones from the two latter categories and determined their complete sequences. For each of the cDNAs, we completely sequenced both strands, mainly using the primer walking method12. Judging from the sequence quality scores calculated using Phred13, the accuracy of the sequence data was more than 99.99%. The average length of the cDNAs was 2,314 bp (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). All the sequence data have been registered in public databases through the DNA database of Japan (DDBJ). Searches for the cDNAs by accession numbers, chromosomal positions, various keywords or sequence similarities are enabled at our website (http://fldb.hri.co.jp/ cgi-bin/cDNA3/public/publication/index.cgi). All physical cDNA clones are freely available for research use on request. Requests for physical cDNA clones should be sent to flcdna@ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp or isogai-t@reprori.jp.

Comparison of the FLJ collection with predicted genes

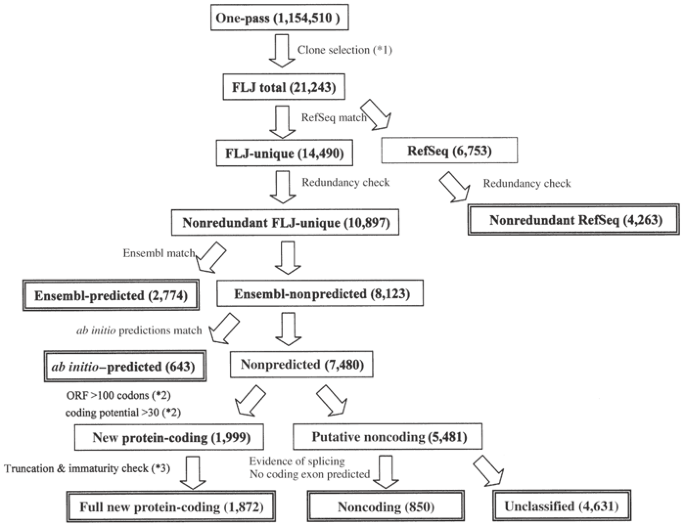

We used BLAST searches to compare our full-length cDNA sequences in series with RefSeq (and other relevant data sets, as outlined in Fig. 1). For 14,490 cDNAs, there were no matches in RefSeq (excluding the 2,313 RefSeq entries that were derived from the FLJ collection), indicating that the full sequences of these cDNAs were unique to the FLJ collection ('FLJ-unique'). The remainder (6,753 cDNAs in 4,263 clusters) at least partially matched sequences in RefSeq. This overlap was because many cDNA sequences that did not have matches at the time of the selection were later sequenced by other researchers during the course of this project. The matches also included alternatively spliced isoforms in RefSeq. There were also a number of cDNAs that were identical to sequences in RefSeq but were selected because of inaccurate one-pass sequence data or human error when picking the clones. We clustered the 14,490 FLJ-unique cDNAs pairwise to remove the redundancy, resulting in 10,897 nonredundant cDNA clusters ('nonredundant FLJ-unique').

Figure 1: Flow chart of cDNA categorization.

Each cDNA was categorized as shown here. For further details on the categorization (steps *1–*3), refer to Supplementary Note and Supplementary Figure 6 online. Detailed descriptions of the cut-offs and the supporting evidence are also presented there.

To determine what proportion of these 10,897 nonredundant FLJ-unique clusters had been previously predicted from the genome sequence (for chromosome assignments of the FLJ cDNAs, see Supplementary Table 2 online), we used BLAST searches to compare these cDNAs with Ensembl genes (using version 4.28.1; 29,076 genes), which are representative predicted genes based on comprehensive analyses of a wide range of evidence and are expected to cover most human genes14. Ensembl genes supported by RefSeq were removed from the search. Among the 10,897 clusters, 2,774 at least partly matched Ensembl genes ('Ensembl-predicted') and 8,123 did not ('Ensembl-nonpredicted').

We then examined whether the 8,123 Ensembl-nonpredicted clusters were predicted by ab initio gene prediction programs, such as DIGIT, FGENESH, GENSCAN and HMMGENES, because the criteria for identifying Ensembl genes are based on a somewhat conservative method of evaluation. As shown in Table 1, 643 Ensembl-nonpredicted clusters were predicted by at least one of these programs ('_ab initio_–predicted'). In total, 3,417 (31%) of the 10,897 nonredundant FLJ-unique clusters corresponded to genes predicted by one or more of the computational methods. These ab initio methods did not predict the existence of the remaining 7,480 clusters ('nonpredicted').

Table 1 Sequence comparison of the 10,897 non-redundant FLJ unique cDNAs and computationally predicted cDNAs

One possible reason why these sequences were not predicted by the computational methods is that most of them were non-protein-coding, and many computational methods predict only protein-coding regions as genes. To check this possibility, we determined how many clusters met the criteria of ORF length >100 codons and coding potential >30 (calculated according to the standard method15). We used these criteria because most of the ORFs registered in RefSeq satisfied them, whereas ORFs randomly occurring in the human genome seldom do (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3 online). Of 7,480 nonpredicted clusters, 1,999 ('new protein-coding') satisfied the criteria. Altogether, there were 5,416 protein-coding clusters (2,774 Ensembl-predicted, 643 _ab initio_–predicted and 1,999 new protein-coding clusters) among the 10,897 nonredundant FLJ-unique clusters ('protein-coding'). We found no ORFs meeting the criteria in the remaining 5,481 nonredundant FLJ-unique clusters (see also Supplementary Note and Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8 online).

Non-protein-coding FLJ-unique cDNA clusters

The length distribution of the cDNAs in the 5,481 clusters that were categorized as non-protein-coding was similar to that of the other clusters (see also Supplementary Fig. 4 online). Although some of these cDNAs might be cloning artifacts, recent evidence indicates that unexpectedly large populations of non-protein-coding transcripts exist in mammalian cells16,17. Genomic alignments of these clusters clearly showed that splicing had occurred for 1,378 of the 5,481 clusters. This splicing can be taken as explicit evidence that these cDNAs were derived from transcripts. We further examined whether these cDNAs contained any protein-coding-like sequences using GENSCAN, because it was possible that ORFs might be disrupted by retained introns, and because GENSCAN can identify interrupted ORFs in cDNA sequences. GENSCAN detected no coding exon–like regions in at least 850 clusters, ruling out the possibility that the retained introns disrupted the ORFs in these clusters.

To characterize the 850 non-coding-transcript clusters, we carried out BLAST searches using our one-pass sequence database (Supplementary Table 1 online), which contains many cDNA sequences derived from various tissues. On average, the BLAST search resulted in 3.7 one-pass-sequence matches per cDNA. Many cDNAs matched a few one-pass sequences, indicating their low expression levels, and 44 clusters matched >10 one-pass sequences. By determining from which cDNA library the matching one-pass sequences were derived, we were able to identify the tissue distribution patterns of the expression of these genes. Some cDNAs had ubiquitous expression patterns, whereas others had very tissue-specific patterns. For 22 cDNAs, >20% of the matching one-pass sequences were derived from a particular cDNA library (examples are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4 online).

GC content of new protein-coding cDNAs

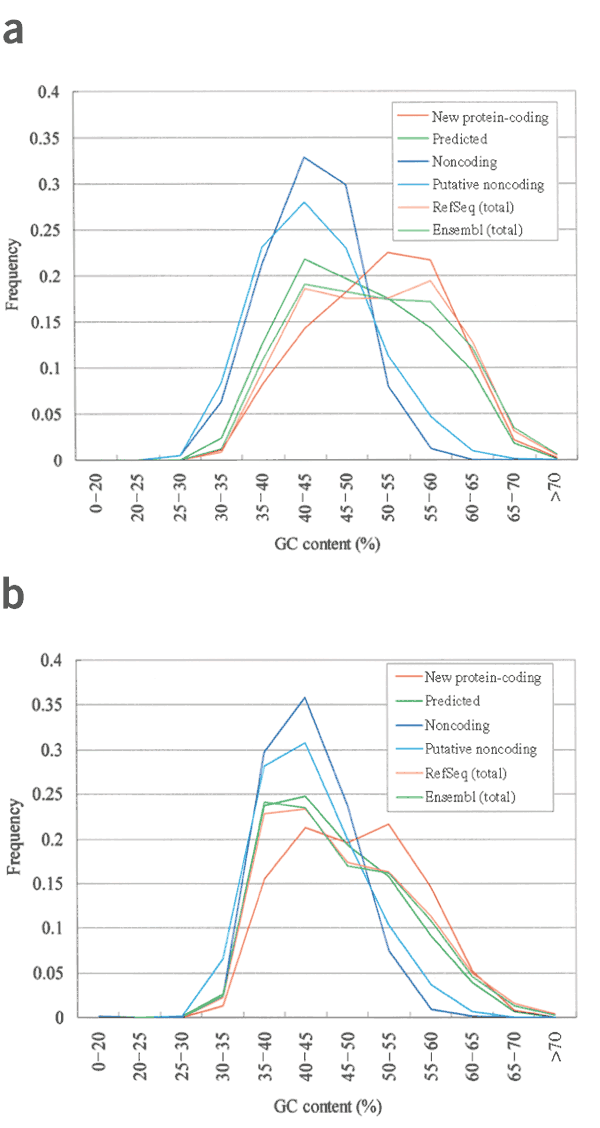

To determine why 1,999 new protein-coding clusters in our FLJ-unique cDNAs were not predicted in Ensembl or by other computational methods, we compared the GC content of cDNAs between new protein-coding and 'predicted' (Ensembl-predicted and _ab initio_–predicted) clusters. The GC content of RefSeq mRNAs ranged broadly between 30% and 70% with two peaks, one at ∼42% and the other at ∼58% (Fig. 2a). The GC content of predicted and new protein-coding cDNAs showed similar broad distributions, but with only one peak each: at 42% for predicted and 58% for nonpredicted cDNAs. This suggests that there is some prediction bias against GC-rich transcripts in current gene prediction procedures. This can be seen also in the distribution of GC content of Ensembl genes. In contrast to RefSeq mRNAs, the peak at ∼58% for all Ensembl genes is less pronounced.

Figure 2: GC contents of the FLJ cDNAs and the corresponding genomic regions to which they were mapped.

(a) GC contents of the new protein-coding cDNAs, non-protein-coding cDNAs, RefSeqs and Ensembl transcripts are shown. (b) GC contents of the genomic regions to which the corresponding transcripts were mapped (from the 5′ ends of first exons to the 3′ ends of the last exons) are shown for each category of the transcripts. For the detailed protocol for the chromosomal assignments of the FLJ cDNAs, please refer to Supplementary Note online (section on length distribution and chromosomal assignments of the 10,897 nonredundant FLJ-unique clusters section). Chromosomal positions of RefSeqs and Ensembl genes are as presented at University of California Santa Cruz genome browser.

As introns are generally more AT-rich than exons4, the distributions of GC content of the corresponding genomic regions for both new protein-coding and predicted cDNAs shifted towards being more AT-rich. But overall patterns showed similar tendencies as cDNAs (Fig. 2b). Thus, current gene prediction procedures may have slight bias against predicting genes in GC-rich regions. This contradicts previous observations that the accuracy of these gene prediction methods is insensitive to the GC content (or is better in GC-rich regions)18,19. The discrepancy is probably caused by the fact that previous analyses were based on a smaller data set and may not be extrapolated accurately to the full-genome scale.

We also calculated distribution of the GC content of noncoding and putative noncoding cDNAs (Fig. 2). To our surprise, both types of cDNA were relatively AT-rich (Fig. 2a). The new protein-coding and putative noncoding cDNAs were originally grouped together as 'nonpredicted' and later separated according to the criteria of ORF length >100 codons and coding potential >30 (Fig. 1). Thus, we anticipated that these two categories might have similar GC content distributions. Instead, the GC content distributions of both putative noncoding and noncoding cDNAs had a peak at ∼42%, similar to that of the predicted clones, but the range was much narrower. The GC content of the genomic regions where those cDNAs were mapped showed a similar AT-rich tendency (Fig. 2b). This raised the possibility that the noncoding cDNAs and the new protein-coding cDNAs are mainly transcribed from different regions of the human genome.

Annotation of protein-coding FLJ-unique cDNAs

For the 5,416 protein-coding clusters, we determined their amino acid sequences from the corresponding cDNA sequences. From the 1,999 new protein-coding cDNAs, we removed cDNAs that seemed to be derived from possibly truncated or immature forms of mRNA (T. Nishikawa et al., unpublished data; see also Supplementary Note online), leaving 1,872 cDNAs ('full new protein-coding'). Thus, a total of 5,289 clusters were subjected to further analysis. The average ORF length was 335 codons (see Supplementary Fig. 1 online for the distribution of the ORF length).

Using the amino acid sequences, we searched the protein motif databases PROSITE (version 16) and Pfam (version 5.5). In the PROSITE search, we found that 1,318 (25%) of these cDNAs had some protein signature (Table 2). In the Pfam search, we found that 3,112 (59%) of the cDNAs had some Pfam motif(s). In total, 1,529 kinds of Pfam motif, corresponding to 63% of the total 2,478 Pfam motifs, were represented. We also searched for putative membrane proteins and secretory proteins using SOSui and PSORT II, respectively (Table 3), which predicted 244 cDNAs for secretory proteins and 848 cDNAs for membrane proteins. Detailed functional annotations for each of these cDNAs are available at our websites20,21.

Table 2 Functional categorization and distribution of the protein motifs of the 5,289 protein-coding clusters

Table 3 Predicted secretory proteins and membrane proteins

Confirmation of transcripts from chromosomes 20–22

We mapped 45, 16 and 39 clusters of protein-coding transcripts to chromosomes 20, 21 and 22, respectively (Supplementary Table 2 online). These chromosomes are 'finished' chromosomes, whose initial annotations are considered complete. As shown in Table 4, 491 of 10,897 nonredundant FLJ-unique clusters mapped to these chromosomes. Of these 491, 268 were protein-coding cDNAs, including 100 full new protein-coding cDNAs. There were 2,188 previously predicted genes (Ensembl genes and _ab initio_–predicted genes). Of these, 1,004 were experimentally identified cDNAs registered in RefSeq; thus, our analyses of FLJ cDNAs confirmed the presence of 168 (14%) of the 1,184 genes that had been predicted without full-length cDNA support and also identified an additional 100 protein-coding genes. This result emphasizes that full-length cDNA data should contribute to the precise annotation of the human genome.

Table 4 FLJ cDNAs mapped to chromosomes 20, 21 and 22

Of these 100 full new protein-coding clusters, we experimentally confirmed the expression of 84 (84%) by RT-PCR using eight kinds of human tissue (Supplementary Fig. 5 online). For the other cDNAs, we observed no clear band under our experimental conditions, perhaps because their expression levels were too low or their expression was highly specific for the tissues or operation materials from which we isolated the RNAs to construct the cDNA libraries.

We also attempted RT-PCR analysis of the noncoding transcripts that mapped to chromosomes 20–22. We detected PCR bands for 32 of these clusters (74%) and observed both ubiquitous and tissue-specific expression patterns (Supplementary Fig. 5 online). There seem to be at least hundreds of potential non-protein-coding transcripts in the human genome, some of which are expressed ubiquitously and others in a tissue-specific manner.

Discussion

Here we describe the complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 cDNA clones of our FLJ cDNA collection (the results of statistical analyses are summarized in Supplementary Table 3 online). Of these, the full-length sequences of 14,490 cDNA clones or 10,876 cDNA clusters were unique to the FLJ project. Within the FLJ-unique clusters, 5,416 seemed to be protein-coding, and these included 2,774 Ensembl-predicted, 643 _ab initio_–predicted and 1,999 non-predicted protein-coding genes.

About two-thirds of the protein-coding genes (3,417 of 5,416) were predicted by computational methods. The total number of Ensembl-predicted genes is currently about 29,000, of which about 15,000 have been confirmed by fully sequenced cDNAs (according to RefSeq as of 1 August 2002). Here we confirmed an additional 2,774 such genes by identifying fully sequenced cDNA clusters (Ensembl-predicted). This corresponds to ∼20% of the 14,000 Ensembl genes that lacked full-length cDNA support. The overlap was not as large as we expected, considering the scale of our project and the fact that Ensembl uses comprehensive evidence of protein homology from various organisms. One reason for this may be that cDNAs derived from long mRNAs were under-represented in the cDNA libraries used in our project. There is a cDNA sequencing project, KIAA, in which considerable effort is aimed at collecting cDNAs of long transcripts10. Such projects, as well as technical development, will be needed to collect cDNAs of long mRNAs. Another reason for the limited overlap may be the limited repertory of our cDNA libraries. Although we analyzed more than 100 different cDNA libraries, we might have missed transcripts whose expression is limited to small organs or rare cell types.

About one-third of protein-coding cDNAs (1,999 of 5,416) were not predicted by Ensembl or by ab initio gene predictions. We found that these new protein-coding cDNAs are relatively GC-rich. Thus, gene prediction methods that are currently in use may have some bias against GC-rich transcripts. Consistent with this finding, we found that the GC content distribution of RefSeq entries has two peaks at ∼42% and ∼58%, and that the peak at ∼58% becomes insignificant when analyzing all Ensembl genes. This supports the suggestion that Ensembl genes that lack RefSeq support tend to be AT-rich. Bernardi proposed that the human genome could be divided into five different GC compositional categories (L1, L2 (AT-rich regions), H1, H2 and H3 (GC-rich regions)) and that L1 and L2 comprise ∼70% of the human genome22. He predicted that GC-rich isochores, especially H3 (GC >48%), are gene-rich and that ∼70% of genes are in the GC-rich region (GC >42%). Recent analysis using human genome draft sequence confirmed that known genes were rich in GC-rich regions (∼70%), although the length and distribution of GC-rich regions and AT-rich regions vary widely in the human genome4,5. The estimate based on the gene prediction suggests that ∼50% rather than ∼70% of genes are present in GC-rich regions5. Our results suggest that there may be more genes to discover in GC-rich regions of the human genome. The new protein-coding cDNAs may be a good training set for improving the gene prediction methods.

In addition to protein-coding genes, we observed a number of putative noncoding clusters (5,481 clusters) among our nonredundant FLJ-unique clusters. About 1,300 of them were derived from spliced transcripts and 850 of them ('noncoding') contained no predicted exons. RT-PCR showed that at least some of them are transcribed in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 5 online). Thus, we consider that most noncoding cDNAs come from real transcripts. The GC content of these cDNAs and the genomic regions in which they were mapped were in the range of low-GC regions. About 65% of those noncoding transcripts are transcribed from genomic regions that were low-GC regions and more than 5 kb upstream or downstream of any RefSeq- or Ensembl-predicted genes (data not shown). We categorized the remaining putative noncoding clusters as 'unclassified'. At present, we think that most of these unclassified cDNAs came from transcripts or their fragments rather than genomic DNA contaminants. For more detailed discussion of this issue, see Supplementary Note online.

Several large-scale projects for the systematic collection and complete sequencing of human and mouse cDNAs are underway23,24,25. The cDNAs identified in the present study, together with those from other projects, should produce a nearly complete physical collection of full-length cDNAs for human genes and those of important model organisms. For analysis of the proteome, the cDNAs are being transferred to various types of expression vectors. Recombinant proteins are being expressed with fusion tags and used for the systematic purification and identification of protein complexes26,27. Projects aimed at the large-scale determination of the three-dimensional structures of proteins have also been initiated based on the full-length cDNA resources28. Comprehensive analysis of the genome, transcriptome and proteome will lead to a better understanding of the architecture of life.

Methods

Construction and characterization of the libraries.

We constructed the cDNA libraries used in this project as previously described9,10. To evaluate the frequency of the full-length cDNAs in each of the libraries, we carried out BLAST searches with the cut-off value of e-100 and examined the relative positions of the 5′ end of the oligo-capped cDNAs compared with the RefSeq data, using all the one-pass sequences produced from each of the libraries. When the one-pass sequences covered the annotated coding-sequence start sites, we categorized them as 'full or near-full'. We applied this criterion because, in many cases, transcriptional start sites could not be sharply defined owing to possible slippery transcriptional start events29, which made it difficult to determine exactly which cDNAs should be more specifically categorized as either 'full' or 'near-full'. The proportion of full-length sequences was calculated as the frequency of the full or near-full sequences among the cDNAs that had matches in RefSeq. The cDNAs that did not match around the 5′ ends, possibly due to either alternative splicing or sequencing errors, were excluded from the calculation. We also excluded cDNAs in RefSeq that were derived from the FLJ project.

BLAST searches.

As those that matched RefSeq sequences, the cDNAs containing at least the annotated coding sequence start sites were categorized as 'full at the 5′ end'. The RefSeq records containing 'FLJ' in the description field were excluded, because 'FLJ' indicated that the FLJ cDNA data were essential for experimental identification of the complete cDNAs of these genes, whose presence was otherwise only predicted based on the homology or partial cDNAs. For re-BLAST searching of the total 21,243 cDNA sequences against RefSeq, we used the BLAST score 1,000 for the cut-off. To further remove the redundancy from 14,490 FLJ-unique cDNAs, we carried out pairwise BLAST searches with a cut-off score of 1.0e-100. When we observed redundancy, we selected the cDNA with the longer 5′ end as representative (10,897 nonredundant FLJ-unique cDNAs). For further details on bioinformatics procedures and supporting evidence, see Supplementary Note online.

Ensembl prediction and ab initio gene predictions.

We obtained Ensembl genes (using version 4.28.1; 29,076 genes) from the Ensembl website. We searched the sequences of 'Homo_sapiens.cdna.fa', which correspond to the predicted cDNA sequences, using our full-length cDNA sequences by BLAST with a cut-off score of 1.0e-100. Ensembl genes contained in RefSeq were excluded. Gene prediction programs were run against the human genomic sequence data (University of California Santa Cruz genome browser) with the default cut-off values. We used predicted exons to generate virtual cDNA sequences and did BLAST searches against them using FLJ cDNA sequences with a cut-off score of 1.0e-100.

URLs.

GenBank, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov /Sitemap/index.html#GenBank; FLJ-DB, http://fldb.hri.co.jp/ cgi-bin/cDNA3/public/publication/index.cgi; Ensembl, http://www.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/; PROSITE, http://www.expasy.ch/prosite/; Pfam, http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Pfam/; SOSui, http://sosui.proteome.bio.tuat.ac.jp/about-sosui.html; PSORT II, http://psort.ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp/; DIGIT, http://digit.ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp; FGENESH, http://www.softberry.com/berry.phtml; GENSCAN, http://genes.mit.edu/GENSCAN.html; HMMGENES, http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/HMMgene/; HUNT database, http://www.hri.co.jp/HUNT/; HUGE database, http://www.kazusa.or.jp/huge/; University of California Santa Cruz genome browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/; NEDO, http://www.nedo.go.jp/bio/index.html.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Genetics website.

References

- Hattori, M. et al. The DNA sequence of human chromosome 21. Nature 405, 311–319 (2000).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Dunham, I. et al. The DNA sequence of human chromosome 22. Nature 402, 489–495 (1999).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Deloukas, P. et al. The DNA sequence and comparative analysis of human chromosome 20. Nature 414, 865–871 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lander, E.S. et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409, 860–921 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Venter, J.C. et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science 291, 1304–1351 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Pruitt, K.D. & Maglott, D.R. RefSeq and LocusLink: NCBI gene-centered resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 137–140 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Boguski, M.S. The turning point in genome research. Trends Biochem. Sci. 20, 295–296 (1995).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Maruyama, K. & Sugano, S. Oligo-capping: a simple method to replace the cap structure of eukaryotic mRNAs with oligoribonucleotides. Gene 138, 171–174 (1994).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Suzuki, Y., Yoshitomo, K., Maruyama, K., Suyama, A. & Sugano, S. Construction and characterization of a full length-enriched and a 5′-end-enriched cDNA library. Gene 200, 149–156 (1997).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Nomura, N. et al. Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. I. The coding sequences of 40 new genes (KIAA0001-KIAA0040) deduced by analysis of randomly sampled cDNA clones from human immature myeloid cell line KG-1. DNA Res. 1, 27–35 (1994).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Altschul, S.F. et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 (1997).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Giesecke, H., Obermaier, B., Domdey, H. & Neubert, W.J. Rapid sequencing of the Sendai virus 6.8 kb large (L) gene through primer walking with an automated DNA sequencer. J. Virol. Methods. 38, 47–60 (1992).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ewing, B., Hillier, L., Wendl, M.C. & Green, P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 8, 175–185 (1998).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hubbard, T. et al. The Ensembl genome database project. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 38–41 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Fickett, J.W. Predictive methods using nucleotide sequences. Methods Biochem. Anal. 39, 231–245 (1998).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Huttenhofer, A. et al. RNomics: an experimental approach that identifies 201 candidates for novel, small, non-messenger RNAs in mouse. EMBO J. 20, 2943–2953 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kapranov, P. et al. Large-scale transcriptional activity in chromosomes 21 and 22. Science 296, 916–919 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Burset, M. & Guigo, R. Evaluation of gene structure prediction programs. Genomics 34, 353–367 (1996).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Rogic, S., Mackworth, A.K. & Ouellette, F.B. Evaluation of gene-finding programs on mammalian sequences. Genome Res. 11, 817–832 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Yudate, H.T. et al. HUNT: launch of a full-length cDNA database from the helix research institute. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 185–188 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hattori, A. et al. Characterization of long cDNA clones from human adult spleen. DNA Res. 7, 1–11 (2001).

Google Scholar - Bernardi, G. The isochore organization of the human genome and its evolutionary history—a review. Gene. 135, 57–66 (1993).

Article CAS Google Scholar - The FANTOM consortium and The RIKEN Genome Exploration Research Group Phase I & II team. Analysis of the mouse transcriptome based on functional annotation of 60,770 full-length cDNAs. Nature 420, 563–573 (2002).

- Wiemann, S. et al. Toward a catalog of human genes and proteins: sequencing and analysis of 500 novel complete protein coding human cDNAs. Genome Res. 11, 422–435 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Strausberg, R.L., Feingold, E.A., Klausner, R.D. & Collins, F.S. The mammalian gene collection. Science 286, 455–457 (1999).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Gavin, A.C. et al. Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature 415, 141–147 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ho, Y. et al. Systematic identification of protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by mass spectrometry. Nature 415, 180–183 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Chance, M.R. et al. Structural genomics: a pipeline for providing structures for the biologist. Protein Sci. 11, 723–738 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Suzuki, Y, et al. Diverse transcriptional initiation revealed by fine, large-scale mapping of mRNA start sites. EMBO Rep. 2, 388–393 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Kishimoto, H. Ezoe and T. Matsuo for supporting the project and E. Nakajima for critically reading the manuscript. This project was supported by the Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry of Japan and also in part by Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. Requests for materials should be addressed to S. Sugano. Requests for physical cDNA clones should be addressed to S.Sugano (flcdna@ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp) or T. Isogai (isogai-t@reprori.jp). For more information on each cDNA clone, visit FLJ-DB. For general information on the FLJ project, please refer to NEDO website.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Helix Research Institute, 1532-3 Yana, Kisarazu, 292-0812, Chiba, Japan

Toshio Ota, Tetsuo Nishikawa, Tetsuji Otsuki, Tomoyasu Sugiyama, Ryotaro Irie, Ai Wakamatsu, Koji Hayashi, Hiroyuki Sato, Keiichi Nagai, Shizuko Ishii, Jun-ichi Yamamoto, Kaoru Saito, Yuri Kawai, Yuko Isono, Yoshitaka Nakamura, Kenji Nagahari, Yasuhiko Masuho & Takao Isogai - Kyowa Hakko Kogyo, Tokyo Research Laboratory, 3-6-6 Asahi-machi, Machida, Tokyo, 194-8533, Japan

Toshio Ota, Masaya Obayashi, Tatsunari Nishi, Satoshi Nakagawa, Akihiro Senoh, Hiroshi Mizoguchi, Ayako Kawabata, Takeshi Hikiji, Naoko Kobatake, Hiromi Inagaki, Yasuko Ikema, Sachiko Okamoto & Rie Okitani - The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, 4-6-1 Shirokane-dai, Minato-ku, Tokyo, 108-8639, Japan

Yutaka Suzuki, Toshikazu Shibahara, Toshihiro Tanaka, Yoshihiro Ohmori, Takuma Kawakami, Saori Noguchi, Tomoko Itoh, Keiko Shigeta, Tadashi Senba, Kyoka Matsumura, Yoshie Nakajima, Takae Mizuno, Misato Morinaga, Masahide Sasaki, Takushi Togashi, Masaaki Oyama, Hiroko Hata, Manabu Watanabe, Takami Komatsu, Junko Mizushima-Sugano, Tadashi Satoh, Yuko Shirai, Yukiko Takahashi, Kiyomi Nakagawa, Riu Yamashita, Kenta Nakai, Tetsushi Yada, Yusuke Nakamura & Sumio Sugano - Hitachi, Central Research Laboratory, 1-280 Higashi-koigakubo, Kokubunj, Tokyo, 185-8601, Japan

Tetsuo Nishikawa, Kouichi Kimura, Hiroshi Makita, Katsuhiko Murakami, Tomohiro Yasuda, Takao Iwayanagi & Tadashi Satoh - National Institute of Technology and Evaluation, 2-49-10 Nishihara, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, 151-0066, Japan

Mitsuo Sekine & Hisashi Kikuchi - Otsuka Pharmaceutical, 463-10 Kagasuno Kawauchi-cho, Tokushima, 771-0192, Japan

Toshikazu Shibahara, Yoshihiro Goto, Fumio Shimizu, Hirokazu Wakebe, Haretsugu Hishigaki, Takeshi Watanabe, Akira Tanigami, Tsutomu Fujiwara, Toshihide Ono, Katsue Yamada, Yuka Fujii, Kouichi Ozaki, Maasa Hirao, Yoshihiro Ohmori & Takuma Kawakami - Hitachi, Life Science Group, 1-3-1 Minamidai, Kawagoe, 350-1165, Saitama, Japan

Masako Wagatsuma, Akiko Shiratori, Hiroaki Sudo, Takehiko Hosoiri, Yoshiko Kaku, Hiroyo Kodaira, Hiroshi Kondo, Masanori Sugawara, Makiko Takahashi, Katsuhiro Kanda, Takahide Yokoi, Takako Furuya, Emiko Kikkawa, Yuhi Omura, Kumi Abe, Kumiko Kamihara, Naoko Katsuta, Kazuomi Sato, Machiko Tanikawa, Makoto Yamazaki & Ken Ninomiya - Hitachi Science Systems, 1-280 Higashi-koigakubo, Kokubunji, Tokyo, 185-8601, Japan

Tadashi Ishibashi, Hiromichi Yamashita, Katsuji Murakawa, Kiyoshi Fujimori, Hiroyuki Tanai, Manabu Kimata, Motoji Watanabe, Susumu Hiraoka, Yoshiyuki Chiba, Shinichi Ishida, Yukio Ono, Sumiyo Takiguchi, Susumu Watanabe, Makoto Yosida, Tomoko Hotuta, Junko Kusano & Keiichi Kanehori - Takara Shuzo, 2257 Sunaike, Noji, Kusatu, Shiga, 525-0055, Japan

Asako Takahashi-Fujii, Hiroto Hara, Tomo-o Tanase, Yoshiko Nomura, Sakae Togiya, Fukuyo Komai, Reiko Hara, Kazuha Takeuchi, Miho Arita, Nobuyuki Imose, Kaoru Musashino, Hisatsugu Yuuki & Atsushi Oshima - Nisshinbo Industries, 1-2-3 Onodai, Midori-ku, Chiba, 267-0056, Japan

Naokazu Sasaki, Satoshi Aotsuka, Yoko Yoshikawa, Hiroshi Matsunawa, Tatsuo Ichihara, Namiko Shiohata, Sanae Sano, Shogo Moriya, Hiroko Momiyama, Noriko Satoh, Sachiko Takami, Yuko Terashima & Osamu Suzuki - Toyobo, 10-24 Toyo-cho, Tsuruga, 914-0047, Fukui, Japan

Akio Sugiyama, Makoto Takemoto & Bunsei Kawakami - Fujiya, 228 Soya, Hadano, Kanagawa, 257-0031, Japan

Masaaki Yamazaki, Koji Watanabe, Ayako Kumagai, Shoko Itakura, Yasuhito Fukuzumi, Yoshifumi Fujimori, Megumi Komiyama & Hiroyuki Tashiro - Aisin Cosmos R&D, 1698 Yana, Kisarazu, 292-0812, Chiba, Japan

Koji Okumura - Kazusa DNA Research Institute, 1532-3 Yana, Kisarazu, 292-0812, Chiba, Japan

Takahiro Nagase, Nobuo Nomura & Osamu Ohara - BIRC, AIST, 2-41-6 Aomi, Koto-ku, Tokyo, 135-0064, Japan

Nobuo Nomura & Sumio Sugano

Authors

- Toshio Ota

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yutaka Suzuki

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tetsuo Nishikawa

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tetsuji Otsuki

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tomoyasu Sugiyama

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ryotaro Irie

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ai Wakamatsu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Koji Hayashi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hiroyuki Sato

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Keiichi Nagai

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kouichi Kimura

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hiroshi Makita

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mitsuo Sekine

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Masaya Obayashi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tatsunari Nishi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Toshikazu Shibahara

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Toshihiro Tanaka

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Shizuko Ishii

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jun-ichi Yamamoto

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kaoru Saito

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yuri Kawai

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yuko Isono

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yoshitaka Nakamura

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kenji Nagahari

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Katsuhiko Murakami

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tomohiro Yasuda

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Takao Iwayanagi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Masako Wagatsuma

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Akiko Shiratori

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hiroaki Sudo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Takehiko Hosoiri

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yoshiko Kaku

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hiroyo Kodaira

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hiroshi Kondo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Masanori Sugawara

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Makiko Takahashi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Katsuhiro Kanda

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Takahide Yokoi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Takako Furuya

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Emiko Kikkawa

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yuhi Omura

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kumi Abe

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kumiko Kamihara

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Naoko Katsuta

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kazuomi Sato

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Machiko Tanikawa

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Makoto Yamazaki

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ken Ninomiya

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tadashi Ishibashi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hiromichi Yamashita

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Katsuji Murakawa

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kiyoshi Fujimori

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hiroyuki Tanai

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Manabu Kimata

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Motoji Watanabe

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Susumu Hiraoka

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yoshiyuki Chiba

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Shinichi Ishida

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yukio Ono

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Sumiyo Takiguchi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Susumu Watanabe

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Makoto Yosida

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tomoko Hotuta

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Junko Kusano

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Keiichi Kanehori

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Asako Takahashi-Fujii

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hiroto Hara

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tomo-o Tanase

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yoshiko Nomura

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Sakae Togiya

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Fukuyo Komai

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Reiko Hara

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kazuha Takeuchi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Miho Arita

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Nobuyuki Imose

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kaoru Musashino

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hisatsugu Yuuki

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Atsushi Oshima

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Naokazu Sasaki

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Satoshi Aotsuka

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yoko Yoshikawa

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hiroshi Matsunawa

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tatsuo Ichihara

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Namiko Shiohata

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Sanae Sano

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Shogo Moriya

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hiroko Momiyama

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Noriko Satoh

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Sachiko Takami

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yuko Terashima

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Osamu Suzuki

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Satoshi Nakagawa

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Akihiro Senoh

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hiroshi Mizoguchi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yoshihiro Goto

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Fumio Shimizu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hirokazu Wakebe

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Haretsugu Hishigaki

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Takeshi Watanabe

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Akio Sugiyama

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Makoto Takemoto

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Bunsei Kawakami

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Masaaki Yamazaki

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Koji Watanabe

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ayako Kumagai

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Shoko Itakura

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yasuhito Fukuzumi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yoshifumi Fujimori

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Megumi Komiyama

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hiroyuki Tashiro

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Akira Tanigami

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tsutomu Fujiwara

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Toshihide Ono

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Katsue Yamada

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yuka Fujii

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kouichi Ozaki

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Maasa Hirao

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yoshihiro Ohmori

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ayako Kawabata

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Takeshi Hikiji

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Naoko Kobatake

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hiromi Inagaki

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yasuko Ikema

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Sachiko Okamoto

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Rie Okitani

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Takuma Kawakami

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Saori Noguchi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tomoko Itoh

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Keiko Shigeta

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tadashi Senba

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kyoka Matsumura

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yoshie Nakajima

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Takae Mizuno

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Misato Morinaga

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Masahide Sasaki

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Takushi Togashi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Masaaki Oyama

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hiroko Hata

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Manabu Watanabe

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Takami Komatsu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Junko Mizushima-Sugano

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tadashi Satoh

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yuko Shirai

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yukiko Takahashi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kiyomi Nakagawa

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Koji Okumura

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Takahiro Nagase

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Nobuo Nomura

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hisashi Kikuchi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yasuhiko Masuho

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Riu Yamashita

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kenta Nakai

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tetsushi Yada

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yusuke Nakamura

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Osamu Ohara

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Takao Isogai

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Sumio Sugano

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence toSumio Sugano.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ota, T., Suzuki, Y., Nishikawa, T. et al. Complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 full-length human cDNAs.Nat Genet 36, 40–45 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1285

- Received: 07 October 2003

- Accepted: 01 December 2003

- Published: 21 December 2003

- Issue Date: 01 January 2004

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1285