Frontiers | Associations of Whole Grain and Refined Grain Consumption With Metabolic Syndrome. A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies (original) (raw)

Introduction

The metabolic syndrome is a complex of interrelated risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes and all-cause mortality. These factors include dysglycemia, raised blood pressure, elevated triglyceride levels, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, and obesity (particularly central adiposity) (1). Affecting about 25% of the population in developed countries in parallel with obesity and diabetes, MetS has been known as an important public health issue in the 21st century (2). Although the etiology of MetS is still not well-understood yet, dietary factors are considered to be associated with MetS (3–5).

Grain, a small, hard and dry seed, is composed of the endosperm, germ, and bran (6). Grain is served as the primary source of carbohydrates and global staples of diets (7). Whole grain contains more abundant and diverse nutrients with potential health benefits (fiber, vitamins, and minerals) than refined grains (8). Indeed, a potential different biological effect of whole grain and refined grain on health issues has been reported, e.g., gastric cancer (6), chronic kidney disease (9) or all-cause mortality (10), etc. Moreover, whole grain consumption was indicated to be associated with a lower risk of hypertension (11) and diabetes (12, 13), whereas refined grain consumption was associated with higher risk of diabetes (13). Moreover, some randomized control trials demonstrated that whole grain (replacing refined grain) within a weight-loss diet could reduce blood glucose (14). A whole grain-based diet could also lower the postprandial plasma insulin and triglyceride level in MetS (15). With regard to the fundamental research, the pre-germinated brown rice extract was also proved to ameliorate MetS model (16, 17).

As far as we know, the associations of whole grain and refined grain consumption with MetS has been investigated by numerous observational studies (18–31). However, their results are still controversial. The present meta-analysis of observational studies was therefore employed to examine the issues further. It was hypothesized that whole grain consumption was inversely associated with MetS, whereas refined grain consumption was positively associated with MetS.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

We conducted this meta-analysis according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (32). The PubMed, Web of Science and Embase database were searched until March 2021 (without restriction for inclusion time), by a series of logic combinations of keywords related to metabolic syndrome (“metabolic syndrome”) and grain (“grain,” “grains,” “rice,” “bread,” “breads,” “wheat,” “wheats,” “rye,” “cereal,” “cereals”). No language restrictions were set in the search strategy. We first screened the titles and abstracts of all of the articles to identify eligible studies and then read the full articles to include eligible studies. Moreover, the reference lists from retrieved articles were reviewed to identify additional studies.

Study Selection

Two researchers (YZ and JD) reviewed the titles, abstracts and full texts of all retrieved studies independently. Disagreements were resolved by discussions and mutual-consultations. The potentially eligible articles were selected through full text review in line with the inclusion and exclusion criteria according to PICOS strategy. The included studies were required to meet the following criteria: (1) the participants were general population; (2) the exposure of interest was the consumption of whole grain or refined grain; (3) the comparison was the highest vs. lowest category of exposure; (4) the outcomes included the MetS; (5) observational studies in general population. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) duplicated or irrelevant articles; (2) reviews, letters or case reports; (3) randomized controlled trials; (4) non-human studies.

Data Extraction

Two researchers extracted the data (YZ and JD) independently. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. The information about first author, year of publication, location, age, gender, sample size, study design, exposure assessment, category of exposure, effect estimates for MetS, adjustments, and diagnostic criteria of MetS was collected. The corresponding effect estimates adjusted for the maximum number of confounding variables with corresponding 95% CIs for the highest vs. lowest level were extracted. For the studies that reported the effect estimates by gender, the pooled effect estimates were calculated. In addition, Huang presented the data as southern and northern China, and they were processed independently (30). Rice/white rice was also processed as refined grain (23, 25–27).

Quality Assessment

Quality assessment was conducted according to the Newcastle-Ottawa (NOS) criteria for non-randomized studies, which is based on three broad perspectives: the selection process of study cohorts, the comparability among different cohorts, and the identification of either the exposure or outcome of study cohorts. Disagreements with respect to the methodological quality were resolved by discussion and mutual-consultation. In the current study, we considered a study awarded seven or more stars as a high-quality study (33).

Statistical Analyses

RR was considered as the common measure of the associations of whole grain or refined grain consumption with MetS, and OR and HR was directly converted into RR. The I2 statistic, which measures the percentage of the total variation across studies due to heterogeneity, was also examined (I2 > 50% was considered heterogeneity). If significant heterogeneity was observed among studies, the random-effects model was used; otherwise, the fixed effects model was utilized. Begg's tests were performed to assess the publication bias (34), and statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 11.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas). A _p_-value < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant. Subgroup analysis for study design, diagnostic criteria of MetS, sample size, exposure assessment, study quality and adjustment of BMI and energy, were conducted.

Results

Study Identification and Selection

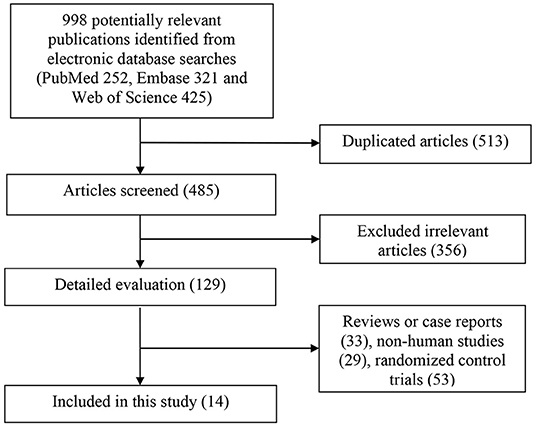

The detailed flow diagram of study identification and selection was presented in Figure 1. A total of 998 potentially relevant articles (PubMed 252, Embase 321 and Web of Science 425) were retrieved during the initial literature search. After eliminating 513 duplicated articles, 485 articles were screened by titles and abstracts. Three hundred fifty six irrelevant studies were excluded thereafter. Then, 33 reviews, case reports or letters, 29 non-human studies, and 53 randomized control trials were removed. Eventually, a total of 14 studies were identified for this meta-analysis.

Figure 1. Flow chart for the identification of studies that were included in this meta-analysis.

Study Characteristics

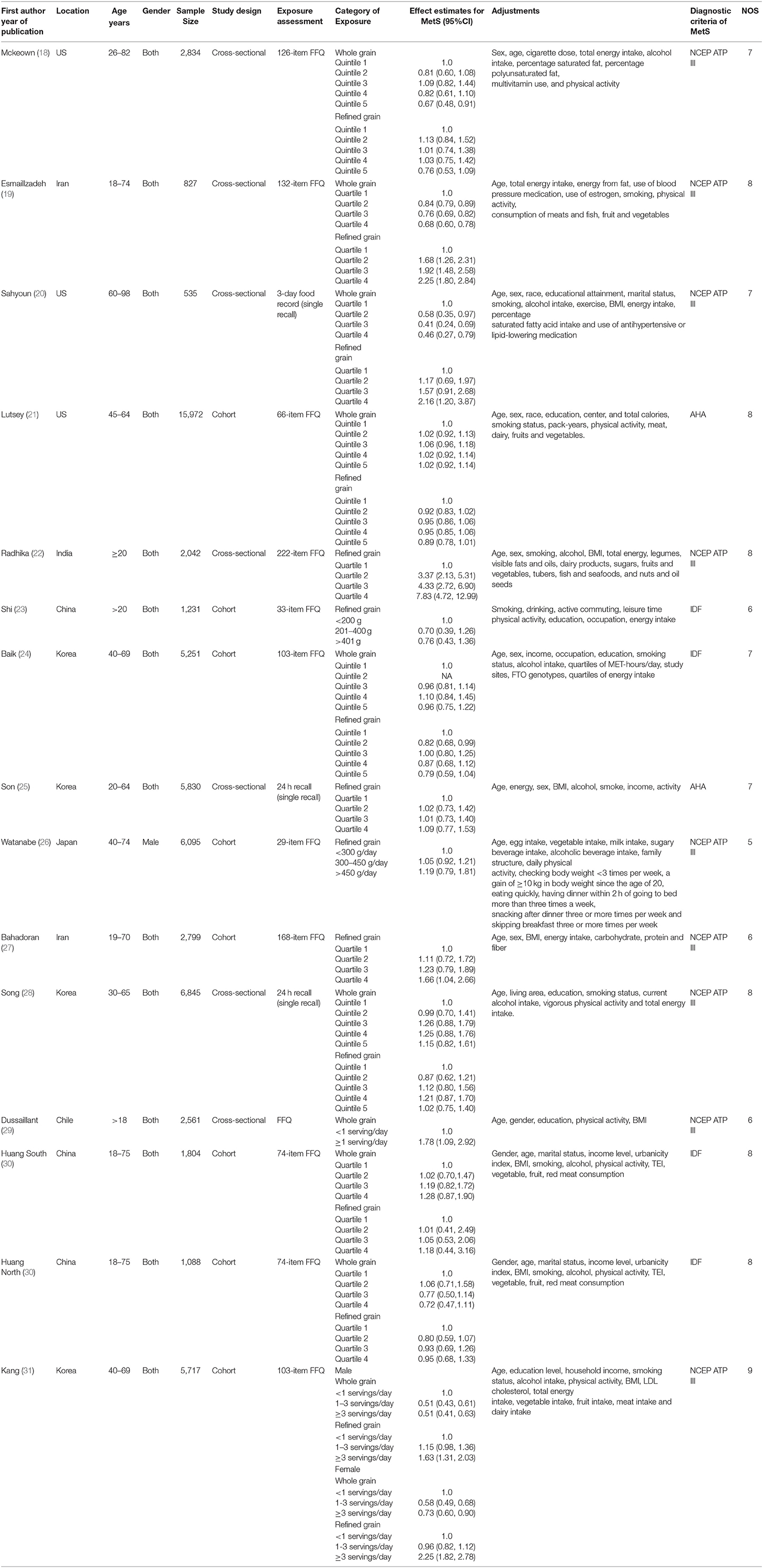

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the included studies. These studies were published between 2004 and 2020, which involved seven cross-sectional and seven prospective cohort studies. Ten studies were performed in the Asian countries [Korea (24, 25, 28, 31), Iran (19, 27), Japan (26), India (22) and China (23, 30)], three studies were conducted in US (18, 20, 21), and one study was conducted in Chile (29). Thirteen articles included both male and female participants (18–25, 27–31), whereas 1 study included only male participants (26). The sample size ranged from 535 to 15,972 for a total number of 61,431. Food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was utilized in 11 studies (18, 19, 21–24, 26, 27, 29–31) and three studies employed recall record (24 h or 3 days) (20, 25, 28). Ten (18–22, 24, 25, 28, 30, 31) and four (23, 26, 27, 29) studies were defined as high and low-quality study, respectively. The diagnostic criteria for MetS were National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) in nine (18–20, 22, 26–29, 31), International Diabetes Foundation (IDF) in three (23, 24, 30), American Heart Association (AHA) (21, 25) in two studies, respectively.

Table 1. Characteristics of the individual studies included in this meta-analysis.

Association Between Whole Grain Consumption and MetS

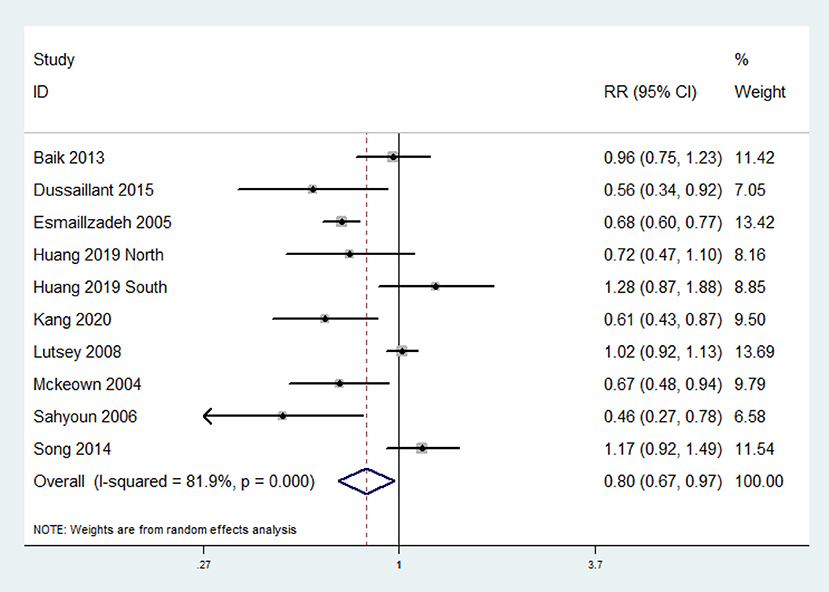

The overall multi-variable adjusted RR evidenced an inverse association between whole grain consumption and MetS (RR = 0.80, 95%CI: 0.67–0.97; P = 0.02) (Figure 2). A substantial level of heterogeneity was observed among studies (P < 0.001, _I_2 = 81.9%). No evidence of publication bias was observed among the included studies according to the Begg rank-correlation test (P = 0.152). In addition, such findings were obtained only in cross-sectional (RR = 0.71, 95%CI: 0.53–0.95; P = 0.02), NCEP ATP III (RR = 0.69, 95%CI: 0.54–0.89; P = 0.004), FFQ (RR = 0.80, 95%CI: 0.65–0.97; P = 0.03), adjustment of BMI (RR = 0.69, 95%CI: 0.49–0.98; P = 0.04) and energy intake (RR = 0.75, 95%CI: 0.59–0.96; P = 0.01) studies (Table 2).

Figure 2. Forest plot of meta-analysis: Overall multi-variable adjusted RR of MetS for the highest vs. the lowest category of whole grain consumption.

Table 2. Subgroup analyses of whole grain consumption and MetS.

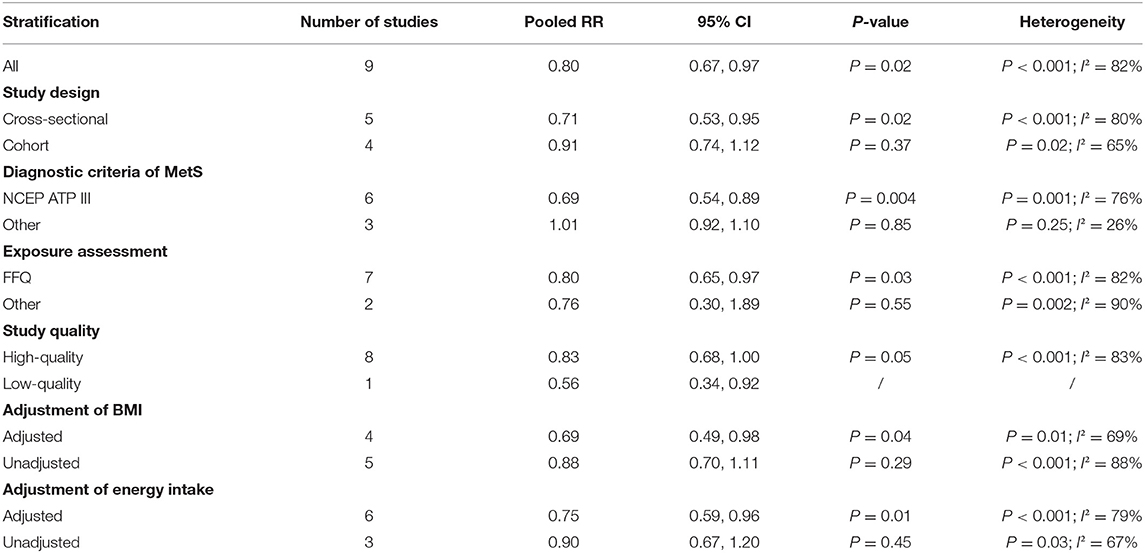

Association Between Refined Grain Consumption and MetS

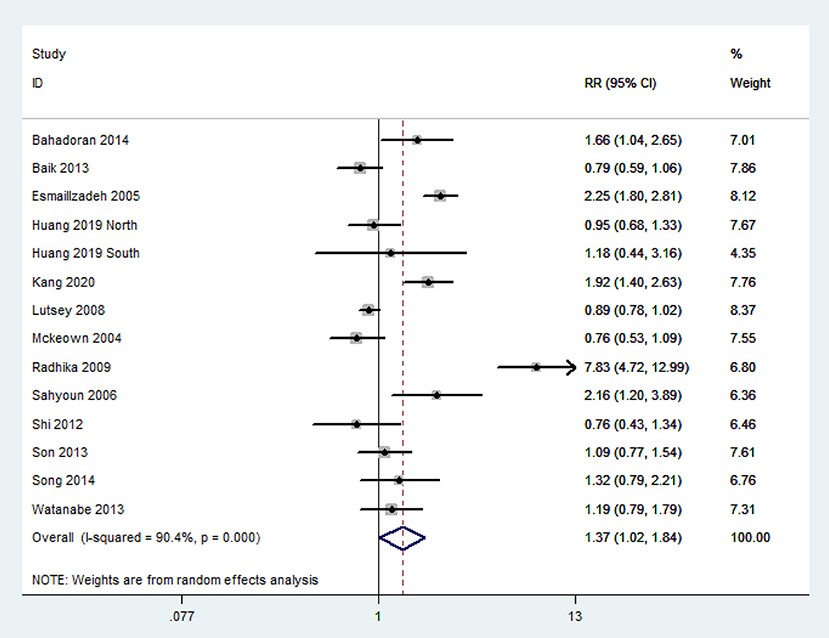

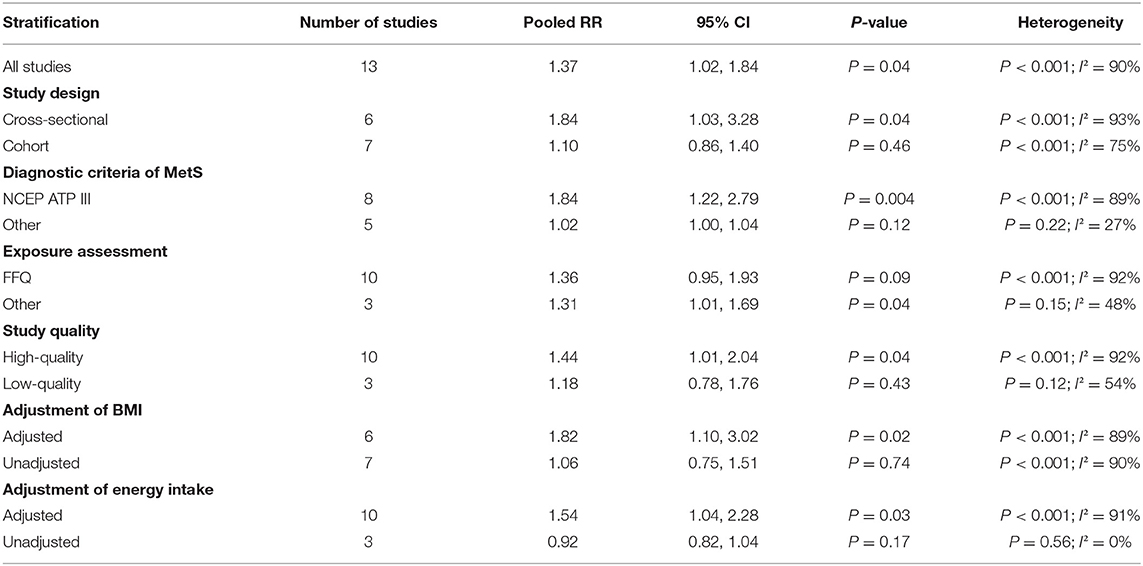

The overall multi-variable adjusted RR demonstrated that refined grain consumption was positively associated with MetS (RR = 1.37, 95%CI: 1.02–1.84 P = 0.036) (Figure 3). A substantial level of heterogeneity was observed among studies (P < 0.001, _I_2 = 90.4%). No evidence of publication bias was observed among the included studies according to the Begg rank-correlation test (P = 0.324). In addition, such findings were obtained only in cross-sectional (RR = 1.84, 95%CI: 1.03–3.28; P = 0.04), NCEP ATP III (RR = 1.84, 95%CI: 1.22–2.79; P = 0.004), high-quality studies (RR = 1.44 95%CI: 1.01–2.04; P = 0.04), adjustment of BMI (RR = 1.82, 95%CI: 1.10–3.02; P = 0.02) and energy intake (RR = 1.54, 95%CI: 1.04–2.28; P = 0.02) studies (Table 3).

Figure 3. Forest plot of meta-analysis: Overall multi-variable adjusted RR of MetS for the highest vs. the lowest category of refined grain consumption.

Table 3. Subgroup analyses of refined grain consumption and MetS.

Discussions

In this study, a total of 14 observational studies were identified. Our pooled analysis showed that whole grain consumption was negatively associated with MetS, whereas refined grain consumption was positively associated with MetS.

The opposite results with regard to the whole grain and refined grain consumption could be explained by several biological mechanisms. First, the glycemic index (GI) and the glycemic load (GL), which are both determined by the amount of carbohydrates consumed, contribute to the glycemic response directly (35). It was reported that GIs and GLs were associated with a higher risk of MetS, which was independent of diabetes mellitus (36). Compared with refined grain, whole grain tends to be absorbed slowly with a relatively low GI. On the contrary, refined grain is abundant in carbohydrate content, which leads to a higher dietary GL (37). Second, whole grain is rich in dietary fiber, trace minerals, and phytochemicals (37). These nutrients and food components were considered to be beneficial for MetS (38, 39). However, the nutrient components of refined grain were lost during the refining process (22).

Our results were supported by several randomized control trials directly. Jackson et al. (14) showed that the replacing refined grain by whole grain in weight-loss diet could reduce glucose directly. Moreover, Giacco et al. (15) further indicated that a 12-weeks of whole grain intervention could reduce postprandial insulin and triglycerides responses in MetS (also compared to refined grain) (15). On the other hand, some fundamental experimental study should also be emphasized. Both Hao et al. (16) and Yen et al. (17) demonstrated that pre-germinated brown rice extract could ameliorate high-fat diet-induced MetS model. Above all, the results of our study were partly supported by the corresponding clinical and experimental evidence.

Generally speaking, whole grain referred to barley, multigrain and ground mixed grain, whereas refined grain included white rice, noodles and bread. Interestingly, several studies have considered the grain consumption as a whole (without subtype specification). Unsurprisingly, no significant relationship was obtained in these studies (40–43). It could be attributed to the synergistic effect of whole grain and refined grain consumption on MetS. Of note, our result was only confirmed in cross-sectional studies both for whole grain and refined grain. Although the reliability of our results may be influenced by the substantial level of heterogeneity, the potential different effect of grain consumption on the prevalence or risk of MetS could not be ignored, it was still an open question for MetS prevention. Moreover, the inconsistent result with regard to diagnostic criteria of MetS, exposure assessment and study quality (for refined grain) was also acquired. FFQ seems to be more reliable and precise for dietary assessment, and the NCEP ATP III criteria may be suitable for considering the effect of grain consumption. In addition, the quality of study may also influence the results. High consumption of whole-grain foods is associated with lower BMI in a dose-dependent manner (44), and BMI is considered as an important factor in MetS (1). Moreover, grain consumption is closely associated with appetite and energy intake (45), and a low reported energy intake is also reported to be associated with MetS (46). Indeed, the inconsistent result with regard to the adjustment of BMI and energy intake was obtained in our study. Therefore, further studies are required to consider BMI and energy intake as confounding factors. It should also be noted that the heterogeneity of our study cannot be ignored, especially for the exposure assessment. A semi-quantitative FFQ was utilized in most studies (18, 19, 21–24, 26, 27, 29–31), whereas several studies used recall record (20, 25, 28). On the other hand, the definition of whole grain or refined grain may vary greatly among individuals. For example, refined grain always refers to rice, noodles or bread etc, but several studies only considered rice/white rice (23, 25–27). These inconsistent exposure assessments could cause significant heterogeneity and inaccuracies in the interpretation of the results. Of note, the plasma level of alkylresorcinols, which was served as a reliable marker of whole grain consumption (14), was unfortunately ignored in all the included studies. Therefore, more well-designed prospective cohort studies are still needed.

Our study has several strengths. First, this is the first meta-analysis of observational study aiming at the associations of whole grain and refined grain consumption with MetS. Second, the included studies were analyzed based on adjusted results and large samples. Third, our result might be helpful to better consider the diet effect on MetS. We should also acknowledge the limitations of the present study. First, the substantial level of heterogeneity might have distorted the results. Second, due to the limitation of relevant literature, only a limited number of observational studies were identified for this meta-analysis. Third, the classification of exposure may vary greatly among individuals. Fourth, the diagnostic criteria of MetS and the selection of adjusted factors were not uniform. Last but not the least, a subgroup for gender could not be performed since very limited study specified the effect estimates by gender. These limitations might weaken the significance of this study.

Conclusions

The existing evidence suggests that whole grain consumption is negatively associated with MetS, whereas refined grain consumption is positively associated with MetS. More well-designed prospective cohort studies are needed to elaborate the concerned issues further.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

YZ conceived the idea and performed the statistical analysis. YZ, HG, and JD drafted this meta-analysis. HG and JD selected retrieved relevant papers. HG and JL assessed each study. YZ was the guarantor of the overall content. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Young Investigator Grant of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (2020Q14).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Alberti K, Eckel R, Grundy S, Zimmet P, Cleeman J, Donato K, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. (2009) 120:1640–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Athyros V, Ganotakis E, Elisaf M, Mikhailidis D. The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome using the National Cholesterol Educational Program and International Diabetes Federation definitions. Curr Med Res Opin. (2005) 21:1157–9. doi: 10.1185/030079905X53333

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Zhang Y, Zhang D. Associations of vegetable and fruit consumption with metabolic syndrome. A meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr. (2018) 21:1693–703. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018000381

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Zhang Y, Zhang D. Relationship between nut consumption and metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Am Coll Nutr. (2019) 38:499–505. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2018.1561341

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Zhang Y, Zhang D. Relationship between serum zinc level and metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Am Coll Nutr. (2018) 37:708–15. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2018.1463876

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Xu Y, Yang J, Du L, Li K, Zhou Y. Association of whole grain, refined grain, and cereal consumption with gastric cancer risk: a meta- analysis of observational studies. Food Sci Nutr. (2018) 7:256–65. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.878

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Kashino I, Eguchi M, Miki T, Kochi T, Nanri A, Kabe I, et al. Prospective association between whole grain consumption and hypertension: the Furukawa Nutrition and Health Study. Nutrients. (2020) 12:902. doi: 10.3390/nu12040902

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Mazidi M, Katsiki N, Mikhailidis D, Banach M. A higher ratio of refined grain to whole grain is associated with a greater likelihood of chronic kidney disease: a population-based study. Br J Nutr. (2019) 121:1294–302. doi: 10.1017/S0007114518003124

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Steffen L, Jacobs D, Stevens J, Shahar E, Carithers T, Folsom A. Associations of whole-grain, refined-grain, and fruit and vegetable consumption with risks of all-cause mortality and incident coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Clin Nutr. (2003) 78:383–90. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.383

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann G, Knüppel S, Iqbal K, Andriolo V, et al. Food groups and risk of hypertension: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Adv Nutr. (2017) 8:793–803. doi: 10.3945/an.117.017178

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Aune D, Norat T, Romundstad P, Vatten L. Whole grain and refined grain consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol. (2013) 28:845–58. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013-9852-5

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Liu S, Manson J, Stampfer M, Hu F, Giovannucci E, Colditz G, et al. A prospective study of whole-grain intake and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in US women. Am J Public Health. (2000) 90:1409–15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.9.1409

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Jackson K, West S, Heuvel J, Jonnalagadda S, Ross A, Hill A, et al. Effects of whole and refined grains in a weight-loss diet on markers of metabolic syndrome in individuals with increased waist circumference: a randomized controlled-feeding trial. Am J Clin Nutr. (2014) 100:577–86. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.078048

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Giacco R, Costabile G, Pepa G, Anniballi G, Griffo E, Mangione A, et al. A whole-grain cereal-based diet lowers postprandial plasma insulin and triglyceride levels in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2014) 24:837–44. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.01.007

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Hao C, Lin H, Ke L, Yen H, Shen K. Pre-germinated brown rice extract ameliorates high-fat diet-induced metabolic syndrome. J Food Biochem. (2019) 43:e12769. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.12769

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Yen H, Lin H, Hao C, Chen F, Chen C, Chen J, et al. Effects of pre-germinated brown rice treatment high-fat diet-induced metabolic syndrome in C57BL/6J mice. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. (2017) 81:979–86. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2017.1279848

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

18. McKeown N, Meigs J, Liu S, Saltzman E, Wilson P, Jacques P. Carbohydrate nutrition, insulin resistance, and the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the framingham offspring cohort. Diabetes Care. (2004) 27:538–46. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.538

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Esmaillzadeh A, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Whole-grain consumption and the metabolic syndrome: a favorable association in Tehranian adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2005) 59:353–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602080

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Sahyoun N, Jacques P, Zhang X, Juan W, McKeown N. Whole-grain intake is inversely associated with the metabolic syndrome and mortality in older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. (2006) 83:124–31. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.1.124

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Lutsey P, Steffen L, Stevens J. Dietary intake and the development of the metabolic syndrome: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circulation. (2008) 117:754–61. doi: 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2008.16455.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Radhika G, Dam R, Sudha V, Ganesan A, Mohan V. Refined grain consumption and the metabolic syndrome in urban Asian Indians (Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study 57). Metabolism. (2009) 58:675–81. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.01.008

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Shi Z, Taylor A, Hu G, Gill T, Wittert G. Rice intake, weight change and risk of the metabolic syndrome development among Chinese adults: the Jiangsu Nutrition Study (JIN). Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. (2012) 21:35–43.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

24. Baik I, Lee M, Jun N, Lee J, Shin C. A healthy dietary pattern consisting of a variety of food choices is inversely associated with the development of metabolic syndrome. Nutr Res Pract. (2013) 7:233–41. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2013.7.3.233

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Son S, Lee H, Park K, Ha T, Seo J. Nutritional evaluation and its relation to the risk of metabolic syndrome according to the consumption of cooked rice and cooked rice with multi-grains in Korean adults: based on 2007-2008 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Korean J Commun Nutr. (2013) 18:77–87. doi: 10.5720/kjcn.2013.18.1.77

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Watanabe Y, Saito I, Asada Y, Kishida T, Matsuo T, Yamaizumi M, et al. Daily rice intake strongly influences the incidence of metabolic syndrome in japanese men aged 40–59 years. J Rural Med. (2013) 8:161–70. doi: 10.2185/jrm.8.161

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Bahadoran Z, Mirmiran P, Delshad H, Azizi F. White rice consumption is a risk factor for metabolic syndrome in Tehrani adults: a prospective approach in Tehran lipid and glucose study. Arch Iran Med. (2014) 17:435–40.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

28. Song S, Lee J, Song W, Paik H, Song Y. Carbohydrate intake and refined-grain consumption are associated with metabolic syndrome in the Korean adult population. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2014) 114:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.08.025

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

29. Dussaillant C, Echeverría G, Villarroel L, Marin P, Rigotti A. Uuhealthy food intake is linked to higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome in children adult population: cross-sectional study in 2009-2010 national health survey. Nutr Hosp. (2015) 32:2098–104. doi: 10.3305/nh.2015.32.5.9657

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Huang L, Wang H, Wang Z, Zhang J, Zhang B, Ding G. Regional disparities in the association between cereal consumption and metabolic syndrome: results from the china health and nutrition survey. Nutrients. (2019) 11:764. doi: 10.3390/nu11040764

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

31. Kang Y, Lee K, Lee J, Kim J. Grain subtype and the combination of grains consumed are associated with the risk of metabolic syndrome: analysis of a community-based prospective cohort. J Nutr. (2020) 150:118–27. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxz179

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

32. Liberati A, Altman D, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche P, Ioannidis J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. (2009) 339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Yuhara H, Steinmaus C, Cohen S, Corley D, Tei Y, Buffler P. Is diabetes mellitus an independent risk factor for colon cancer and rectal cancer? Am J Gastroenterol. (2011) 106:1911–22. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.301

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Augustin L, Kendall C, Jenkins D, Willett W, Astrup A, Barclay A, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load and glycemic response: an International Scientific Consensus Summit from the International Carbohydrate Quality Consortium (ICQC). Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2015) 25:795–815. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.05.005

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Juanola-Falgarona M, Salas-Salvadó J, Buil-Cosiales P, Corella D, Estruch R, Ros E, et al. Dietary glycemic index and glycemic load are positively associated with risk of developing metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2015) 63:1991–2000. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13668

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

37. Slavin J, Martini M, Jacobs D, Marquart L. Plausible mechanisms for the protectiveness of whole grains. Plausible mechanisms for the protectiveness of whole grains. Am J Clin Nutr. (1999) 70:459S−63S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.3.459s

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Grooms K, Ommerborn M, Pham D, Djoussé L, Clark C. Dietary fiber intake and cardiometabolic risks among US adults, NHANES 1999-2010. Am J Med. (2013) 126:1059–67.e1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.07.023

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Ju S, Choi W, Ock S, Kim C, Kim D. Dietary magnesium intake and metabolic syndrome in the adult population: dose-response meta-analysis and meta-regression. Nutrients. (2014) 6:6005–19. doi: 10.3390/nu6126005

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

40. Ruidavets J, Bongard V, Dallongeville J, Arveiler D, Ducimetière P, Perret B, et al. High consumptions of grain, fish, dairy products and combinations of these are associated with a low prevalence of metabolic syndrome. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2007) 61:810–7. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.052126

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

41. Jung H, Han S, Song S, Paik H, Baik H, Joung H. Association between adherence to the Korean Food Guidance System and the risk of metabolic abnormalities in Koreans. Nutr Res Pract. (2011) 5:560–8. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2011.5.6.560

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

43. Pasdar Y, Moradi S, Moludi J, Darbandi M, Niazi P, Nachvak S, et al. Risk of metabolic syndrome in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Mediterr J Nutr Metab. (2019) 12:353–63. doi: 10.3233/MNM-190290

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

44. McKeown N, Yoshida M, Shea M, Jacques P, Lichtenstein A, Rogers G, et al. Whole-grain intake and cereal fiber are associated with lower abdominal adiposity in older adults. J Nutr. (2009) 139:1950–5. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.103762

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

45. Sanders L, Zhu Y, Wilcox M, Koecher K, Maki K. Effects of whole grain intake, compared with refined grain, on appetite and energy intake: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Nutr. (2021) nmaa178. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmaa178

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

46. Buscemi S, Verga S, Donatelli M, D'Orio L, Mattina A, Tranchina M, et al. A low reported energy intake is associated with metabolic syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. (2009) 32:538–41. doi: 10.1007/BF03346503