Crohn Disease Workup: Approach Considerations, Routine Laboratory Studies, Serologic Testing (original) (raw)

Approach Considerations

Crohn disease is initially diagnosed on the basis of a combination of clinical, laboratory, histologic, and radiologic findings. Laboratory study results are generally nonspecific but may be helpful in supporting the diagnosis and managing the disease. Serologic studies are sometimes used to facilitate differentiation of Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) of undetermined type.

Various imaging modalities are available to aid in the diagnosis and management of Crohn disease. Contrast radiologic studies are recommended to determine disease extent, disease severity and complications, and treatment strategy. [12] The choice of modality depends on the clinical question being asked, as follows:

- Colonoscopy is the technique of choice to assess disease activity in patients with symptomatic colonic Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis; [59] complementary cross-sectional imaging can be used to assess phenotype and as an alternative to evaluate disease activity [59]

- Upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy and/or colonoscopy and histologic examination are recommended in cases of suspected Crohn disease on the basis of clinical findings; [12] upper GI endoscopy is also recommended when lower GI endoscopy is unable to definitely diagnose Crohn disease or in the presence of upper GI symptoms, but not for asymptomatic newly diagnosed patients [59, 12]

- Plain radiography or computed tomography (CT) scanning of the abdomen can be used to assess for bowel obstruction; these studies can also be used to assess the pelvis for the presence of any intra-abdominal abscesses

- The use of CT enterography or magnetic resonance (MR) enterography is replacing small bowel follow-through (SBFT) studies; the enterographic images can better distinguish between inflammation and fibrosis

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis or endoscopic ultrasonography (ie, transrectal ultrasonography) can identify perianal fistulae anatomy and activity and detect the presence or absence of pelvic and perianal abscesses

Capsule endoscopy is sensitive for early mucosal inflammation, but it can only detect mucosal changes, whereas MRI and intestinal ultrasonography are able to reveal transmural inflammation, as well as identify complications. [59, 12] Furthermore, MRI detects fistulae, deep ulcerations, and a thickened bowel wall. [59] Ultrasonography is inexpensive and can be performed at the point of care by the treating gastroenterologist.

Ultrasonography, CT scanning, and MRI can determine pretreatment and posttreatment disease activity or identify disease complications. [12] Cross-sectional imaging should be used to detect strictures in the case of complications. [59] Because of radiation associated with CT scanning, the preferred methods are MRI and intestinal ultrasonography. Cross-sectional imaging is also recommended for the detection of abscesses. For the diagnosis of perianal Crohn disease, clinical and endoscopic rectal examination, as well as MRI, is recommended; ultrasonography in the absence of anal stenosis or transperineal ultrasonography is an alternative to MRI. [59]

A risk-stratification model based on levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), which are significantly associated with complications of Crohn disease, could reduce the use of computed tomography (CT) scans in patients reporting to the emergency department by 43%, while missing only 0.8% of emergencies, according to a retrospective analysis of 613 adult patients. [60] Researchers used logistic regression to model associations between these laboratory values and perforation, abscess, or other serious complications. Further validation studies of the models need to be performed.

Many centers favor judicious use of imaging and employ low-radiation protocols where possible, especially in younger individuals. Patients with complicated Crohn disease who undergo multiple radiologic examinations may be at risk for cumulative exposure to potentially excessive amounts of diagnostic radiation. [61, 62, 63, 64] Ultrasonography and MRI can be used as adjunct studies if radiation exposure is an issue in monitoring disease activity.

Interventional radiology is primarily used in the percutaneous drainages of abscesses that complicate Crohn disease, which may obviate the need for surgical resection. [65]

Endoscopic visualization and biopsy are essential in the diagnosis of Crohn disease. Colonoscopy with intubation of the terminal ileum is used to evaluate the extent of disease, to demonstrate strictures and fistulae, and to obtain biopsy samples to help differentiate the process from other inflammatory, infectious, or acute conditions. Given the increased risk of colorectal cancer in patients with IBD, colonoscopy may have a role in cancer surveillance, although the frequency of this practice remains controversial.

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy may be used to diagnose gastroduodenal disease, if suspected. This study is recommended for all children, regardless of the presence or absence of upper GI symptoms.

For more information, see Imaging in Crohn Disease.

Routine Laboratory Studies

Laboratory results for Crohn disease are nonspecific and are of value principally for facilitating disease management. Laboratory values may also be used as surrogate markers for inflammation and nutritional status and to screen for deficiencies of vitamins and minerals.

Complete blood cell count

A complete blood cell (CBC) count is useful in detecting anemia, which may be due to multiple causes, including chronic inflammation, iron malabsorption, chronic blood loss, and malabsorption of vitamin B-12 or folate. Leukocytosis may be due to chronic inflammation, abscess, or steroid treatment.

Chemistry panel

Electrolyte analysis can help determine the patient’s level of hydration and renal function. Hypoalbuminemia is a common laboratory finding in patients with suboptimally treated Crohn disease. Additional common abnormalities include deficiencies in iron and micronutrients (eg, folic acid, vitamin B-12, serum iron, total iron binding capacity, calcium, and magnesium). Liver function test results may be elevated, either transiently (because of inflammation) or chronically (because of sclerosing cholangitis).

Inflammatory markers

Acute inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) level or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), may correlate with disease activity in some patients. If Crohn disease activity is suspected, however, a normal ESR or CRP level should not deter further evaluation.

Stool studies

Stool samples should be tested for the presence of white blood cells (WBCs), occult blood, routine pathogens, ova, parasites, and Clostridium difficile toxin. These studies should also be used to rule out infectious etiologies during relapses and before the initiation of immunosuppressive agents. [6]

Fecal calprotectin has been proposed as a noninvasive surrogate marker of intestinal inflammation in IBD. [66] The level of the inflammatory marker calprotectin in feces correlates significantly with endoscopic colonic inflammation in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease, and fecal lactoferrin is significantly correlated with histologic inflammation. [67] However, colorectal neoplasia and GI infection also increase fecal calprotectin; therefore, this study should be used with caution.

At present, fecal calprotectin is not in widespread use, except in research protocols. In the future, this marker may be made more available to clinicians for following patients’ disease activity.

Serologic Testing

There are 2 serologic tests that are currently used in efforts to differentiate ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease. Antibodies to the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ie, anti-S cerevisiae antibodies [ASCA]) are found more commonly in Crohn disease than in ulcerative colitis, whereas perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA), a myeloperoxidase antigen, is found more commonly in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn disease.

The World Gastroenterology Organization (WGO) indicates that ulcerative colitis is more likely when the test results are positive for pANCA and negative for ASCA antigen; [57] however, the pANCA test may be positive in Crohn disease, and this may complicate obtaining a diagnosis in otherwise uncomplicated colitis. [58]

It should be noted that both tests are recommended only as an adjunct to the clinical diagnosis; the results are not specific and have been found to be positive in other bowel diseases. Patients with Crohn disease whose condition is ASCA-positive have a higher rate of surgery and require surgery earlier in the course of the disease, independent of the area of involvement. [1, 2, 6]

Additional serologic markers, such as Escherichia coli anti-ompC (outer membrane porin C), can be found in more than 50% of Crohn disease cases and in only a small percentage of ulcerative colitis cases. Pseudomonas fluorescens (anti-12) may be found in more than 50% of Crohn disease cases and in only 10% of ulcerative colitis cases. Flagellinlike antigen (anti-Cbir1) is associated independently with small bowel, intestinal penetrating, and fibrostenosing disease. These tests further increase sensitivity and diagnostic value.

Plain Abdominal Radiography

Abdominal radiography is a nonspecific test for evaluation of IBD; however, it can useful if there is concern about obstruction or perforation. If abdominal radiographs are obtained, findings may include mural thickening and dilatation, small bowel and colonic mucosal abnormalities, and abnormal fecal distribution with areas of colonic involvement without fecal material. [65]

In patients with known Crohn disease who present with acute exacerbation, symptoms, or suspected complications, radiographs can be obtained to evaluate for the presence of bowel obstruction, perforation (free air), or toxic colon distention. [65] These conditions necessitate rapid management.

For more information, see Imaging in Crohn’s Disease.

Barium Contrast Studies

Barium enema is noninvasive and usually well tolerated for evaluating features such as pseudodiverticula, fistulization, and the severity and length of colonic strictures. SBFT and enteroclysis may be valuable in demonstrating the distribution of small bowel disease in a patient presenting with suspected IBD. Mucosal fissures, bowel fistulae, strictures, and obstructions can be visualized. The terminal ileum may be narrowed and thickened, with a characteristic pipe appearance.

However, barium studies are contraindicated in patients with known perforation, and water-soluble agents should be used in place of barium. Barium can also cause peritonitis. Although in the past, barium contrast studies were the imaging modalities of choice for Crohn disease, these studies now are less commonly used, with the advent of new and more detailed CT, MRI, and capsule endoscopy techniques to assess for small bowel and pelvic Crohn disease.

For more information, see Imaging in Crohn Disease.

Small bowel follow-through

An upper GI SBFT and spot films of the terminal ileum can be used to assess the small bowel of patients with suspected Crohn disease. SBFT can also detect alteration of the small bowel wall indirectly (through findings such as enteroenteric and enterocolonic fistulization.

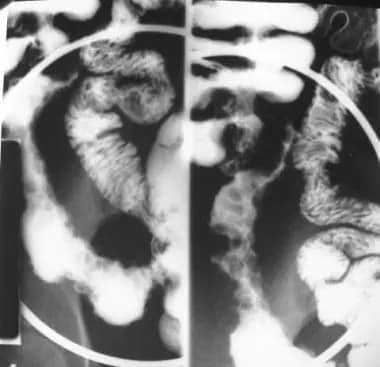

Radiographic findings in both the small and the large bowel parallel the clinical pattern. Edema and ulceration of the mucosa in the small bowel may appear as thickening and distortion of valvulae conniventes. Edema of the deep layers of the bowel wall results in separation of the barium-filled bowel loops. Tracking of deep ulcerations, both transversely and longitudinally, results in a cobblestone appearance (see the image below).

Crohn disease. Cobblestoning in Crohn disease. This is a spot view of the terminal ileum from a small bowel follow-through study. It demonstrates linear longitudinal and transverse ulcerations that create a cobblestone appearance. Also, note the relatively greater involvement of the mesenteric side of the terminal ileum and the displacement of the involved loop away from the normal small bowel secondary to mesenteric inflammation and fibrofatty proliferation.

Ileitis can also manifest as a string sign on barium studies secondary to spasm or, rarely, because of fibrotic stricture (see the following images).

Crohn disease. Crohn disease of terminal ileum. The small bowel follow-through study demonstrates the string sign in the terminal ileum. Also, note the pseudodiverticula of the antimesenteric wall of the terminal ileum, secondary to greater distensibility of this less-involved wall segment.

Crohn disease. This spot view of the terminal ileum from a small bowel follow-through study in a patient with Crohn disease demonstrates the string sign, consistent with narrowing and stricturing. Also, note a sinus tract originating from the medial wall of the terminal ileum and the involvement of the medial wall of the cecum.

Enteroclysis

Overall, enteroclysis is reserved for complicated cases. This imaging modality is roughly as accurate as SBFT and has a shorter examination time; however, the peroral SBFT examination uses less total room time, radiologist time, and radiation, and it has greater patient tolerability. [65]

A useful adjunct study to the initial SBFT or enteroclysis is the peroral pneumocolon evaluation, in which air is instilled per rectum after the opacification of the terminal ileum. [65] This double-contrast examination allows assessment of the distal small bowel or ascending colon or both and often yields improved mucosal detail and greater distention of the terminal ileum. [65]

Barium enema

If the patient can tolerate a barium enema, this study may help in the evaluation of colonic lesions (see the following images).

Crohn disease. Aphthous ulcers. A double-contrast barium enema examination in a patient with Crohn colitis demonstrates numerous aphthous ulcers.

Crohn disease. This double-contrast barium enema study demonstrates marked ulceration, inflammatory changes, and narrowing of the right colon in a patient with Crohn colitis.

Fistulae can also be detected by barium studies of the digestive tract or through injection into the opening of the suspected fistulae (see the image below). [68, 69, 70]

Crohn disease. Enterocolic fistula in a patient with Crohn disease. The double-contrast barium enema study demonstrates multiple fistulous tracts between the terminal ileum and the right colon adjacent to the ileocecal valve (so-called double-tracking of the ileocecal valve).

Computed Tomography Scanning

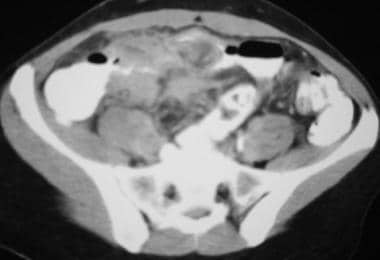

Computed tomography (CT) scanning is helpful in—and considered the imaging technique of choice for—the assessment of extramural complications as well as hepatobiliary and renal complications in adults and children. [65, 68, 69, 70] It may show bowel wall thickening, bowel obstruction, mesenteric edema, abscesses, or fistulae (see the image below).

Crohn disease. Active small bowel inflammation in a patient with Crohn disease. This computed tomography scan demonstrates small bowel wall thickening, mesenteric inflammatory stranding, and mesenteric adenopathy.

CT enterography can be helpful in the assessment of subtle and obvious mucosal damage. VoLumen oral contrast (Bracco Diagnostics, Princeton, NJ) is used as a negative agent to enhance small bowel wall changes, if present. Active disease is demonstrated by bowel wall thickening and mural hyperenhancement that occurs in a stratified enhancement pattern and a hyperemic vasa recta. [65] In the presence of severe inflammation, perienteric inflammatory changes can be seen.

CT enterography is also useful in deciphering whether a stricture is fibrostenotic rather than inflammatory or mixed. The degree and length of narrowing are important in planning for endoscopic examination (eg, by determining whether dilation is possible) and in preoperative staging.

The American College of Radiology (ACR) indicates that CT may be more sensitive than barium studies in detecting Crohn disease, owing to its ability to visualize pelvic small bowel loops, [71, 72] which are often obscured by overlapping bowel in barium studies. This and other evidence partially explain why CT has become the procedure of choice not only for helping diagnose Crohn disease but also for managing abscesses. Moreover, a growing body of literature shows that CT-guided percutaneous abscess drainage may obviate surgery.

For more information, see Imaging in Crohn Disease.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

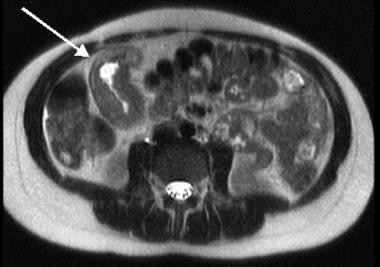

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been shown to yield a higher sensitivity and specificity than ileocolonoscopy (the criterion standard) both for diagnosing Crohn disease and for determining its severity. [73, 74] It is especially useful for evaluating pelvic and perianal disease when one is investigating for evidence of perianal fistulae and abscesses (see the image below). Typical changes depicting active disease include thickening of the bowel wall, high T2 signal of the walls with hyperenhancement and stratification, and hyperemic vasa recta. [65]

Crohn disease. This magnetic resonance image demonstrates an inflamed terminal ileum in 10-year-old girl with Crohn disease.

In a prospective study comparing the use of MRI to the standard Crohn Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity (CDEIS), MRI was validated as a modality that accurately assesses intestinal wall thickness, the presence and degree of edema, and ulcers in patients with Crohn disease. [75] This study confirmed that through relative contrast enhancement (RCE), MRI plays an essential role in predicting disease activity and severity in Crohn disease. [75]

MRI is the study of choice for evaluation and management of perianal Crohn disease. It can be superior to CT in demonstrating pelvic lesions. In addition, MRI can be used when ionizing radiation is contraindicated and in children and pregnant women (if done without gadolinium). [65] Compared with CT, MRI of the pelvis can more accurately detect pelvic and perianal abscesses, as well as better categorize fistula anatomy and activity.

MR enterography and CT enterography are increasingly being used for evaluation of the small bowel. Compared with SBFT, both of these studies are as sensitive and specific, and possibly more accurate, in detecting extraenteric complications, including fistulae and abscesses. [76] Because of the lack of radiation exposure, MR enterography is a particularly attractive option.

Owing to the differential water content, MRI can differentiate active inflammation from fibrosis as well as distinguish between inflammatory and (fixed) fibrostenotic lesions in Crohn disease. [68, 69, 70]

Studies have shown that MR enterography may be superior to CT enterography in the depiction of disease activity (eg, mural thickening and enhancement) [77] and in the detection of stricture presence. [78] In particular, the positive impact on medical or surgical management has been noted in evaluation of small bowel Crohn disease [79] ; these conclusions have been gathered by comparing findings on MR enterography to endoscopic evaluations and surgical pathology reports.

For more information, see Imaging in Crohn Disease.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is a quick, inexpensive, and noninvasive screening method used for the diagnosis of IBD or for repeated evaluation for complications. [68, 69, 70] Abdominal ultrasonography can rule out gallbladder and kidney stones as well as detect enlarged lymph nodes and abscesses. However, it has a steep learning curve that yields a range of sensitivity that is operator-dependent. Because of their lack of radiation exposure, ultrasonography and MRI are often preferred to CT, especially in younger patients. [65]

Rectal endoscopic ultrasonography has been used as an alternative to MRI in the assessment of perianal disease. This technique allows differentiation of simple fistulae from complex ones, as well as assessment of fistula tracts in relation to the sphincter muscle. [68, 69, 70] Ultrasonography has been shown to improve the outcomes of fistula healing when used in conjunction with surgical seton (silk string) placement and anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy. [80, 81, 82]

For more information, see Imaging in Crohn’s Disease.

Endoscopy and Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy

Ileocolonoscopy is a highly sensitive and specific tool in the diagnosis and management of patients with suspected or already established IBD. This procedure is useful in obtaining biopsy tissue, which helps in the differentiation of other diseases, in the evaluation of mass lesions, and in the performance of cancer surveillance.

Colonoscopy also enables dilation of fibrotic strictures in patients with long-standing disease and has been used in the assessment of mucosal healing. In addition, it may be used in the postoperative period to evaluate surgical anastomoses as a means of predicting the likelihood of clinical relapse as well as the response to postoperative therapy. [1]

Ileocolonoscopy has a sensitivity of 74% and a specificity of 100% in the assessment of Crohn disease, leading to a positive predictive value of 100% as a diagnostic test. [45] When paired with small bowel imaging, the sensitivity of this pair of diagnostic tests is increased to 78%, with a continued positive predictive value of 100%. [45]

For patients with Crohn disease of the colon, magnifying endoscopy allows a more detailed view of the mucosal surface than conventional endoscopy does. In combination with chromoendoscopy (methylene blue), it is possible to analyze the surface staining pattern further to help identify neoplastic changes in situ and take targeted biopsies. [6, 25, 68, 69, 70]

For more information, see Colonoscopy.

Upper GI endoscopy

Upper GI endoscopy (or esophagogastroduodenoscopy [EGD]) with biopsy is helpful in differentiating Crohn disease from peptic ulcer disease induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or Helicobacter pylori or from fungal and viral gastroenteritis in patients with upper GI tract symptoms. A history of ileocolic Crohn disease in a patient with unexplainable upper GI symptoms warrants an EGD.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is helpful as a diagnostic procedure and a therapeutic tool in patients with sclerosing cholangitis and biliary stricture formation. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) may provide equally valuable information without invasive complications. A dominant biliary stricture may benefit from balloon dilation, stent placement, or both, though the latter is controversial in the management of primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Small bowel enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy

Single- and double-balloon enteroscopy allows complete evaluation of the small bowel and makes distal ileal biopsies feasible. Enteroscopy can also be helpful in the detection of complications of Crohn disease, such as stricture and active disease.

Wireless capsule endoscopy helps to identify involvement of the upper GI tract and may be especially useful in cases of jejunal or proximal ileal anastomotic surveillance. Drawbacks of this technique include the inability to take biopsies and the risk of acute obstruction. If an obstruction is suspected, small bowel imaging should be done before capsule endoscopy.

Guidelines on the use of enteroscopy and endoscopy in the diagnosis and management of IBD are available from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. [83]

Nuclear Imaging

Radionucleotide scanning may be helpful in assessing the severity and extent of the disease in patients who are too ill to undergo colonoscopy or barium studies. [68, 69, 70] However, nuclear imaging studies are not the tests of choice: MRI, CT, and endoscopic examination of the mucosa for active disease are preferred.

Leukocytes labeled with either technetium-99m (99m Tc )-HMPAO (hexamethyl propylene amine oxime) or indium-111 (111 In) can be used to assess for active bowel inflammation in IBD. The99m Tc-labeled leukocytes may be able to obtain an exact image of the inflammatory disease distribution and intensity at a moment in time—in a single examination. [65]

Compared with the111 In label, the99m Tc-HMPAO label has better imaging characteristics and can be imaged much sooner after injection. However, imaging must typically be performed within 1 hour after the injection of99m Tc- HMPAO–labeled leukocytes because there is normal excretion into the bowel after this time; in contrast,111 In-labeled leukocytes have no normal bowel excretion.

Fluorine-18-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) combined with positron emission tomography (PET) or CT helps improve localization of the tracer in areas of active inflammation, but false-positive results can occur with inadequate distention of the bowel. [65] Studies are being conducted to evaluate combining PET/CT with CT enterography/enteroclysis techniques with the aim of further improving localization while reducing the rate of false-positive findings. [65]

For more information, see Imaging in Crohn’s Disease.

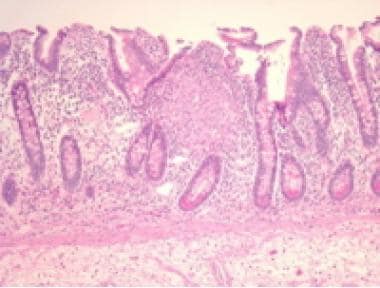

Histology

The characteristic pattern of inflammation in Crohn disease is transmural involvement of the bowel wall by lymphoid infiltrates that contain noncaseating granulomas in about 15-30% of cases of biopsy samples and 40-60% of surgical specimens. A granuloma is defined as a collection of monocyte/macrophage cells and other inflammatory cells, with or without giant cells (see the image below).

Crohn disease. The histologic image shows granuloma in the mucosa of a patient with Crohn disease.

Other characteristics include proliferative changes in the muscularis mucosa and in the nerves scattered in the bowel wall and myenteric plexus. In the involved foci of the small and large bowel, Paneth cell hyperplasia is frequent, and areas of pyloric metaplasia may be seen. In severe cases, long and deep fissurelike ulcers form.

Upper GI tract Crohn disease may be more challenging to diagnose. The histologic picture of gastric Crohn disease is typically described as focally enhancing gastritis in the setting of negative H pylori or other infections. Esophageal or duodenal biopsies in Crohn disease may reveal villous architectural changes with moderate inflammation. Granulomas generally are not identified, but when they are present, they provide substantial corroborative evidence for the diagnosis.

- Kornbluth A, Sachar DB, Salomon P. Crohn's disease. Feldman M, Scharschmidt BF, Sleisenger MH, eds. Sleisenger & Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1998. Vol 2: 1708-34.

- Panes J, Gomollon F, Taxonera C, et al. Crohn's disease: a review of current treatment with a focus on biologics. Drugs. 2007. 67(17):2511-37.

- Tierney LM. Crohn's disease. Tierney LM, McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA, eds. Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment. 40th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional Publishing; 2001. 638-42.

- Mackner LM, Bickmeier RM, Crandall WV. Academic achievement, attendance, and school-related quality of life in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012 Feb. 33(2):106-11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rabbett H, Elbadri A, Thwaites R, et al. Quality of life in children with Crohn's disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996 Dec. 23(5):528-33. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Nikolaus S, Schreiber S. Diagnostics of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. Nov 2007. 133(5):1670-89. [Full Text].

- Strong SA, Koltun WA, Hyman NH, Buie WD. Practice parameters for the surgical management of Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007 Nov. 50(11):1735-46. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Farmer RG, Hawk WA, Turnbull RB Jr. Clinical patterns in Crohn's disease: a statistical study of 615 cases. Gastroenterology. 1975 Apr. 68(4 Pt 1):627-35. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- D'Haens G, Baert F, van Assche G, et al, for the Belgian Inflammatory Bowel Disease Research Group., North-Holland Gut Club. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn's disease: an open randomised trial. Lancet. 2008 Feb 23. 371(9613):660-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tsianos EV, Katsanos KH, Tsianos VE. Role of genetics in the diagnosis and prognosis of Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Jan 14. 18(2):105-18. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Thoreson R, Cullen JJ. Pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease: an overview. Surg Clin North Am. 2007 Jun. 87(3):575-85. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Matsuoka K, Kobayashi T, Ueno F, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2018 Mar. 53 (3):305-53. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Hampe J, Grebe J, Nikolaus S, et al. Association of NOD2 (CARD 15) genotype with clinical course of Crohn's disease: a cohort study. Lancet. 2002 May 11. 359(9318):1661-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zouali H, et al. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001 May 31. 411(6837):599-603. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Duerr RH, Taylor KD, Brant SR, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 2006 Dec 1. 314(5804):1461-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Glas J, Seiderer J, Wetzke M, et al. rs1004819 is the main disease-associated IL23R variant in German Crohn's disease patients: combined analysis of IL23R, CARD15, and OCTN1/2 variants. PLoS One. 2007 Sep 5. 2(9):e819. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Nimmo ER, et al. IL23R Arg381Gln is associated with childhood onset inflammatory bowel disease in Scotland. Gut. 2007 Aug. 56(8):1173-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Barrett JC, Hansoul S, Nicolae DL, et al. Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn's disease. Nat Genet. 2008 Aug. 40(8):955-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Hampe J, Franke A, Rosenstiel P, et al. A genome-wide association scan of nonsynonymous SNPs identifies a susceptibility variant for Crohn disease in ATG16L1. Nat Genet. 2007 Feb. 39(2):207-11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rioux JD, Xavier RJ, Taylor KD, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for Crohn disease and implicates autophagy in disease pathogenesis. Nat Genet. 2007 May. 39(5):596-604. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Parkes M, Barrett JC, Prescott NJ, et al. Sequence variants in the autophagy gene IRGM and multiple other replicating loci contribute to Crohn's disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2007 Jul. 39(7):830-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Libioulle C, Louis E, Hansoul S, et al. Novel Crohn disease locus identified by genome-wide association maps to a gene desert on 5p13.1 and modulates expression of PTGER4. PLoS Genet. 2007 Apr 20. 3(4):e58. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007 Jun 7. 447(7145):661-78. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Hedin C, Whelan K, Lindsay JO. Evidence for the use of probiotics and prebiotics in inflammatory bowel disease: a review of clinical trials. Proc Nutr Soc. 2007 Aug. 66(3):307-15. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Baumgart DC. Endoscopic surveillance in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: who needs what and when?. Dig Dis. 2011. 29 Suppl 1:32-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB, Rutgeerts P, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance treatment of Crohn's disease: results of the CLASSIC II trial. Gut. Sep 2007. 56(9):1232-9. [Full Text].

- Lindberg E, Jarnerot G, Huitfeldt B. Smoking in Crohn's disease: effect on localisation and clinical course. Gut. 1992 Jun. 33(6):779-82. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- D'Souza S, Levy E, Mack D, et al. Dietary patterns and risk for Crohn's disease in children. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008 Mar. 14(3):367-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Davis RL, Kramarz P, Bohlke K, et al, for the Vaccine Safety Datalink Team. Measles-mumps-rubella and other measles-containing vaccines do not increase the risk for inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study from the Vaccine Safety Datalink project. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001 Mar. 155(3):354-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Reif S, Lavy A, Keter D, et al. Appendectomy is more frequent but not a risk factor in Crohn's disease while being protective in ulcerative colitis: a comparison of surgical procedures in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Mar. 96(3):829-32. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Loftus EV Jr, Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Crohn's disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gastroenterology. 1998 Jun. 114(6):1161-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Dec. 5(12):1424-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Shivananda S, Lennard-Jones J, Logan R, et al. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease across Europe: is there a difference between north and south? Results of the European Collaborative Study on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EC-IBD). Gut. 1996 Nov. 39(5):690-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Loftus EV Jr. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004 May. 126(6):1504-17. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lovasz BD, Golovics PA, Vegh Z, Lakatos PL. New trends in inflammatory bowel disease epidemiology and disease course in Eastern Europe. Dig Liver Dis. 2013 Apr. 45(4):269-76. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Economou M, Zambeli E, Michopoulos S. Incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disease and its etiological influences. Annals of Gastroenterology. Available at https://www.annalsgastro.gr/index.php/annalsgastro/article/view/743. 2009. 22(3):158-67; Accessed: December 11, 2012.

- Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012 Jan. 142(1):46-54.e42; quiz e30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Calkins BM, Lilienfeld AM, Garland CF, Mendeloff AI. Trends in incidence rates of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1984 Oct. 29(10):913-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Duerr RH. Update on the genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003 Nov-Dec. 37(5):358-67. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Jess T, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, et al. Survival and cause specific mortality in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a long term outcome study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-2004. Gut. 2006 Sep. 55(9):1248-54. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Jess T, Frisch M, Simonsen J. Trends in overall and cause-specific mortality among patients with inflammatory bowel disease from 1982 to 2010. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Jan. 11(1):43-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, Binder V. Intestinal cancer risk and mortality in patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1993 Dec. 105(6):1716-23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology and pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 1998 Jul. 115(1):182-205. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Friedman S, Blumberg RS. Inflammatory bowel disease. Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DS, et al, eds. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 15th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional Publishing; 2001. Vol 2: 1679-91.

- Wilkins T, Jarvis K, Patel J. Diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease. Am Fam Physician. 2011 Dec 15. 84(12):1365-75. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Danese S, Semeraro S, Papa A, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2005 Dec 14. 11(46):7227-36. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Canavan C, Abrams KR, Mayberry J. Meta-analysis: colorectal and small bowel cancer risk in patients with Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006 Apr 15. 23(8):1097-104. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Jess T, Simonsen J, Jorgensen KT, Pedersen BV, Nielsen NM, Frisch M. Decreasing risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease over 30 years. Gastroenterology. 2012 Aug. 143(2):375-81.e1; quiz e13-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Herrinton LJ, Liu L, Levin TR, Allison JE, Lewis JD, Velayos F. Incidence and mortality of colorectal adenocarcinoma in persons with inflammatory bowel disease from 1998 to 2010. Gastroenterology. 2012 Aug. 143(2):382-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Yu N. The prevalence of extraintestinal diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Apr. 96(4):1116-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Isaacs KL. How prevalent are extraintestinal manifestations at the initial diagnosis of IBD?. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008 Oct. 14 Suppl 2:S198-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Aghazadeh R, Zali MR, Bahari A, Amin K, Ghahghaie F, Firouzi F. Inflammatory bowel disease in Iran: a review of 457 cases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005 Nov. 20(11):1691-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J, et al. A simple classification of Crohn's disease: report of the Working Party for the World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000 Feb. 6(1):8-15. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005 Sep. 19 Suppl A:5-36. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Leach ST, Nahidi L, Tilakaratne S, Day AS, Lemberg DA. Development and assessment of a modified Pediatric Crohn Disease Activity Index. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010 Aug. 51(2):232-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kappelman MD, Crandall WV, Colletti RB, et al. Short pediatric Crohn's disease activity index for quality improvement and observational research. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Jan. 17(1):112-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Bernstein CN, Eliakim A, Fedail S, et al. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guidelines inflammatory bowel disease: update August 2015. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016 Nov/Dec. 50 (10):803-18. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] World Gastroenterology Organisation. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guideline: inflammatory bowel disease: a global perspective. Munich, Germany: World Gastroenterology Organisation; 2009. Available at https://guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=15231. Accessed: December 12, 2012.

- McNamara D. New IBD guidelines aim to simplify care. Medscape Medical News. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/892853. February 20, 2018; Accessed: June 6, 2018.

- Govani SM, Guentner AS, Waljee AK, Higgins PD. Risk stratification of emergency department patients with Crohn's disease could reduce computed tomography use by nearly half. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Oct. 12(10):1702-1707.e3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Newnham E, Hawkes E, Surender A, James SL, Gearry R, Gibson PR. Quantifying exposure to diagnostic medical radiation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: are we contributing to malignancy?. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Oct 1. 26(7):1019-24. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Desmond AN, O'Regan K, Curran C, et al. Crohn's disease: factors associated with exposure to high levels of diagnostic radiation. Gut. 2008 Nov. 57(11):1524-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kambadakone AR, Prakash P, Hahn PF, Sahani DV. Low-dose CT examinations in Crohn's disease: Impact on image quality, diagnostic performance, and radiation dose. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010 Jul. 195(1):78-88. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Craig O, O'Neill S, O'Neill F, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography using lower doses of radiation for patients with Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Aug. 10(8):886-92. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Panes J, Bouzas R, Chaparro M, et al. Systematic review: the use of ultrasonography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis, assessment of activity and abdominal complications of Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Jul. 34(2):125-45. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gisbert JP, McNicholl AG. Questions and answers on the role of faecal calprotectin as a biological marker in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2009 Jan. 41(1):56-66. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- D'Inca R, Dal Pont E, Di Leo V, et al. Calprotectin and lactoferrin in the assessment of intestinal inflammation and organic disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007 Apr. 22(4):429-37. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mackalski BA, Bernstein CN. New diagnostic imaging tools for inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. May 2006. 55(5):733-41.

- Saibeni S, Rondonotti E, Iozzelli A, et al. Imaging of the small bowel in Crohn's disease: a review of old and new techniques. World J Gastroenterol. 2007 Jun 28. 13(24):3279-87. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Schreyer AG, Seitz J, Feuerbach S, Rogler G, Herfarth H. Modern imaging using computer tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) AU1. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004 Jan. 10(1):45-54. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Kidd R, Mezwa DG, Ralls PW, et al. Imaging recommendations for patients with newly suspected Crohn's disease, and in patients with known Crohn's disease and acute exacerbation or suspected complications. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Radiology. 2000 Jun. 215 Suppl:181-92. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fidler JL, Rosen MP, Blake MA, et al, for the Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal Imaging. ACR Appropriateness Criteria: Crohn disease. [online publication]. Reston, Va: American College of Radiology; 2011. Available at https://guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=35137. Accessed: April 5, 2011.

- Pilleul F, Godefroy C, Yzebe-Beziat D, Dugougeat-Pilleul F, Lachaux A, Valette PJ. Magnetic resonance imaging in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005 Aug-Sep. 29(8-9):803-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Florie J, Horsthuis K, Hommes DW, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging compared with ileocolonoscopy in evaluating disease severity in Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005 Dec. 3(12):1221-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rimola J, Ordas I, Rodriguez S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for evaluation of Crohn's disease: validation of parameters of severity and quantitative index of activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Aug. 17(8):1759-68. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lee SS, Kim AY, Yang SK, et al. Crohn disease of the small bowel: comparison of CT enterography, MR enterography, and small-bowel follow-through as diagnostic techniques. Radiology. 2009 Jun. 251(3):751-61. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Low RN, Francis IR, Politoske D, Bennett M. Crohn's disease evaluation: comparison of contrast-enhanced MR imaging and single-phase helical CT scanning. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000 Feb. 11(2):127-35. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fiorino G, Bonifacio C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Prospective comparison of computed tomography enterography and magnetic resonance enterography for assessment of disease activity and complications in ileocolonic Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 May. 17(5):1073-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hafeez R, Punwani S, Boulos P, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic impact of MR enterography in Crohn's disease. Clin Radiol. 2011 Dec. 66(12):1148-58. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Guidi L, Ratto C, Semeraro S, et al. Combined therapy with infliximab and seton drainage for perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease with anal endosonographic monitoring: a single-centre experience. Tech Coloproctol. 2008 Jun. 12(2):111-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Schwartz DA, White CM, Wise PE, Herline AJ. Use of endoscopic ultrasound to guide combination medical and surgical therapy for patients with Crohn's perianal fistulas. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005 Aug. 11(8):727-32. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Wise PE, Schwartz DA. The evaluation and treatment of Crohn perianal fistulae: EUA, EUS, MRI, and other imaging modalities. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2012 Jun. 41(2):379-91. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Leighton JA, Shen B, Baron TH, et al. ASGE guideline: endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006 Apr. 63(4):558-65. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rubin DT, Panaccione R, Chao J, Robinson AM. A practical, evidence-based guide to the use of adalimumab in Crohn's disease. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011 Sep. 27(9):1803-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Robinson M. Optimizing therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997 Dec. 92(12 Suppl):12S-17S. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Helwick C. Stem cell transplantation halts Crohn's disease. Medscape Medical News from WebMD. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/804570. May 22, 2013; Accessed: June 4, 2013.

- Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr 15. 362(15):1383-95. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lim WC, Hanauer S. Aminosalicylates for induction of remission or response in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Dec 8. CD008870. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ford AC, Bernstein CN, Khan KJ, et al. Glucocorticosteroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr. 106(4):590-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Turner D, Grossman AB, Rosh J, et al. Methotrexate following unsuccessful thiopurine therapy in pediatric Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Dec. 102(12):2804-12; quiz 2803, 2813. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, Hanauer SB, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr. 106(4):644-59. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- US Food and Drug Administration. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) blockers: label change - boxed warning updated for risk of infection from Legionella and Listeria. Posted September 7, 2011. Available at https://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm270977.htm. Accessed: April 5, 2012.

- Yadav A, Kurada S, Foromera J, Falchuk KR, Feuerstein JD. Meta-analysis comparing the efficacy and adverse events of biologics and thiopurines for Crohn's Disease after surgery for ulcerative colitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2018 May 30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Lichtenstein GR, Abreu MT, Cohen R, Tremaine W. American Gastroenterological Association Institute medical position statement on corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2006 Mar. 130(3):935-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1999 May 6. 340(18):1398-405. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJ, et al. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn's disease. Crohn's Disease cA2 Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997 Oct 9. 337(15):1029-35. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1999 May 6. 340(18):1398-405. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Louis E, Mary JY, Vernier-Massouille G, et al. Maintenance of remission among patients with Crohn's disease on antimetabolite therapy after infliximab therapy is stopped. Gastroenterology. 2012 Jan. 142(1):63-70.e5; quiz e31. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Peyrin-Biroulet L, Laclotte C, Bigard MA. Adalimumab maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease with intolerance or lost response to infliximab: an open-label study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Mar 15. 25(6):675-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn's disease: the CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology. 2006 Feb. 130(2):323-33; quiz 591. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn's disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007 Jan. 132(1):52-65. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mannon PJ, Fuss IJ, Mayer L, et al. Anti-interleukin-12 antibody for active Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2004 Nov 11. 351(20):2069-79. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, et al. Adalimumab induction therapy for Crohn disease previously treated with infliximab: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Jun 19. 146(12):829-38. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Peppercorn MA. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and prognosis of ulcerative colitis in adults. UpToDate. September 15, 2008. [Full Text].

- Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Stoinov S, et al. Certolizumab pegol for the treatment of Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jul 19. 357(3):228-38. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Schreiber S, Khaliq-Kareemi M, Lawrance IC, et al. Maintenance therapy with certolizumab pegol for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jul 19. 357(3):239-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lichtenstein GR, Thomsen OO, Schreiber S, et al. Continuous therapy with certolizumab pegol maintains remission of patients with Crohn's disease for up to 18 months. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Jul. 8(7):600-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Biogen Idec Elan. TYSABRI (natalizumab) Safety Update: (17 August 2012). Available at https://www.tapp.com.au/members/Tysabri_Safety_Update_160812.pdf. Accessed: December 14, 2012.

- FDA. FDA Drug Safety Communication: New risk factor for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) associated with Tysabri (natalizumab) [safety announcement]. January 20, 2012. Available at https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm288186.htm. Accessed: December 14, 2012.

- Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, Enns R, et al. Natalizumab induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2005 Nov 3. 353(18):1912-25. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Targan SR, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, et al, for the International Efficacy of Natalizumab in Crohn's Disease Response and Remission (ENCORE) Trial Group. Natalizumab for the treatment of active Crohn's disease: results of the ENCORE Trial. Gastroenterology. 2007 May. 132(5):1672-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 22. 369(8):711-21. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Brooks M. FDA clears ustekinumab (Stelara) for Crohn's disease. Medscape Medical News. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/869259. September 26, 2016; Accessed: September 30, 2016.

- Johnson & Johnson. FDA approves STELARA (ustekinumab) for treatment of adults with moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease. Available at https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/fda-approves-stelara-ustekinumab-for-treatment-of-adults-with-moderately-to-severely-active-crohns-disease. September 26, 2016; Accessed: September 30, 2016.

- Sandborn W, Gasink C, Blank M, et al. O-001 A multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study of ustekinumab, a human IL-12/23P40 mAB, in moderate-severe Crohn's disease refractory to anti-TFNα: UNITI-1. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Mar. 22 suppl 1:S1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Feagan B, Gasink C, Lang Y, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study of ustekinumab, a human monoclonal antibody to IL-12/23P40, in patients with moderately- to severely-active Crohn's disease who are naive or non-refractory to anti-TNF (UNITI-2). Presented at: American College of Gastroenterology 2015 Annual Scientific Meeting; Honolulu, Hawaii; October 16-21, 2015. [Full Text].

- Sanborn W, Feagan BG, Gasink C, et al. A phase 3 randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of ustekinumab maintenance therapy in moderate-severe Crohn's disease patients: results from IM-UNITI [abstract 768]. Presented at: Digestive Disease Week; San Diego, California; May 23, 2016. [Full Text].

- Iborra M, Beltran B, Fernandez-Clotet A, et al. Real-world short-term effectiveness of ustekinumab in 305 patients with Crohn's disease: results from the ENEIDA registry. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019 Aug. 50 (3):278-88. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- McSharry K, Dalzell AM, Leiper K, El-Matary W. Systematic review: the role of tacrolimus in the management of Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Dec. 34(11-12):1282-94. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Solomon MJ, McLeod RS, O’Connor BI, Steinhart H, Greenberg GR, Cohen Z. Combination of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole in severe perianal Crohn’s disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 1993. 7:571-3.

- Borrelli O, Cordischi L, Cirulli M, et al. Polymeric diet alone versus corticosteroids in the treatment of active pediatric Crohn's disease: a randomized controlled open-label trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Jun. 4(6):744-53. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Harpavat M, Keljo DJ, Regueiro MD. Metabolic bone disease in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004 Mar. 38(3):218-24. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Heuschkel R. Enteral nutrition in Crohn disease: more than just calories. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004 Mar. 38(3):239-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Razack R, Seidner DL. Nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007 Jul. 23(4):400-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Whitten KE, Rogers P, Ooi CY, Day AS. International survey of enteral nutrition protocols used in children with Crohn's disease. J Dig Dis. 2012 Feb. 13(2):107-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Markowitz J, Markowitz JE, Bousvaros A, et al. Workshop report: prevention of postoperative recurrence in Crohn's disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005 Aug. 41(2):145-51. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ewe K, Herfarth C, Malchow H, Jesdinsky HJ. Postoperative recurrence of Crohn's disease in relation to radicality of operation and sulfasalazine prophylaxis: a multicenter trial. Digestion. 1989. 42(4):224-32. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Alos R, Hinojosa J. Timing of surgery in Crohn's disease: a key issue in the management. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 Sep 28. 14(36):5532-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Simillis C, Yamamoto T, Reese GE, et al. A meta-analysis comparing incidence of recurrence and indication for reoperation after surgery for perforating versus nonperforating Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Jan. 103(1):196-205. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Shen B. Managing medical complications and recurrence after surgery for Crohn's disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008 Dec. 10(6):606-11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cobb WS IV. Finney pyloroplasty. Ponsky JR, Rosen MJ, eds. Atlas of Surgical Techniques for the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract and Small Bowel. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2010. 97-103.

- Angel CA. Finney pyloroplasty. Townsend CM Jr, Evers BM, eds. Atlas of General Surgical Techniques. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2010. Chapter 24.

- Yamamoto T, Fazio VW, Tekkis PP. Safety and efficacy of strictureplasty for Crohn's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007 Nov. 50(11):1968-86. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Couckuyt H, Gevers AM, Coremans G, Hiele M, Rutgeerts P. Efficacy and safety of hydrostatic balloon dilatation of ileocolonic Crohn's strictures: a prospective longterm analysis. Gut. 1995 Apr. 36(4):577-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Garcia JC, Persky SE, Bonis PA, Topazian M. Abscesses in Crohn's disease: outcome of medical versus surgical treatment. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001 May-Jun. 32(5):409-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Berg DF, Bahadursingh AM, Kaminski DL, Longo WE. Acute surgical emergencies in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Surg. 2002 Jul. 184(1):45-51. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kiran RP, Nisar PJ, Church JM, Fazio VW. The role of primary surgical procedure in maintaining intestinal continuity for patients with Crohn's colitis. Ann Surg. 2011 Jun. 253(6):1130-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kamm MA, Ng SC. Perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease: a call to action. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Jan. 6(1):7-10. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bode M, Eder S, Schurmann G. [Perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease--biologicals and surgery: is it worthwhile?]. Z Gastroenterol. 2008 Dec. 46(12):1376-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Poritz LS, Rowe WA, Koltun WA. Remicade does not abolish the need for surgery in fistulizing Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002 Jun. 45(6):771-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Liu CD, Rolandelli R, Ashley SW, Evans B, Shin M, McFadden DW. Laparoscopic surgery for inflammatory bowel disease. Am Surg. Dec 1995. 61(12):1054-6.

- Sardinha TC, Wexner SD. Laparoscopy for inflammatory bowel disease: pros and cons. World J Surg. 1998 Apr. 22(4):370-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Georgeson KE, Cohen RD, Hebra A, et al. Primary laparoscopic-assisted endorectal colon pull-through for Hirschsprung's disease: a new gold standard. Ann Surg. 1999 May. 229(5):678-82; discussion 682-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lowney JK, Dietz DW, Birnbaum EH, Kodner IJ, Mutch MG, Fleshman JW. Is there any difference in recurrence rates in laparoscopic ileocolic resection for Crohn's disease compared with conventional surgery? A long-term, follow-up study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006 Jan. 49(1):58-63. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chen HH, Wexner SD, Iroatulam AJ, et al. Laparoscopic colectomy compares favorably with colectomy by laparotomy for reduction of postoperative ileus. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000 Jan. 43(1):61-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Eshuis EJ, Polle SW, Slors JF, et al. Long-term surgical recurrence, morbidity, quality of life, and body image of laparoscopic-assisted vs. open ileocolic resection for Crohn's disease: a comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008 Jun. 51(6):858-67. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Eshuis EJ, Bemelman WA, van Bodegraven AA, et al. Laparoscopic ileocolic resection versus infliximab treatment of distal ileitis in Crohn's disease: a randomized multicenter trial (LIR!C-trial). BMC Surg. 2008 Aug 22. 8:15. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Farraye FA, Melmed GY, Lichtenstein GR, Kane SV. ACG clinical guideline: preventive care in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Feb. 112 (2):241-58. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, Regueiro MD, Gerson LB, Sands BE. ACG clinical guideline: management of Crohn's disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Apr. 113 (4):481-517. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Bruining DH, Zimmermann EM, Loftus EV Jr, et al. Consensus Recommendations for Evaluation, Interpretation, and Utilization of Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Enterography in Patients With Small Bowel Crohn's Disease. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar. 154 (4):1172-94. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Experts offer guidance on cross-sectional enterography in Crohn’s disease. Reuters Health Information. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/891631. January 23, 2018; Accessed: July 26, 2019.

- Willeman T, Jourdil JF, Gautier-Veyret E, Bonaz B, Stanke-Labesque F. A multiplex liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method for the quantification of seven therapeutic monoclonal antibodies: Application for adalimumab therapeutic drug monitoring in patients with Crohn's disease. Anal Chim Acta. 2019 Aug 27. 1067:63-70. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Khan KJ, Ullman TA, Ford AC, et al. Antibiotic therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr. 106(4):661-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Feagan BG, Rutgeerts PJ, Sands BE, et al. Induction therapy for ulcerative colitis: results of GEMINI I, a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter phase 3 trial [abstract 943b]. Gastroenterology. 2012. 142(5):S160-61.

- Sakuraba A, Keyashian K, Correia C, et al. Natalizumab in Crohn's disease: results from a US tertiary inflammatory bowel disease center. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013 Mar. 19(3):621-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Savarino E, Bodini G, Dulbecco P, et al. Adalimumab is more effective than azathioprine and mesalamine at preventing postoperative recurrence of Crohn's disease: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 Nov. 108(11):1731-42. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Valentine JF, Fedorak RN, Feagan B, et al. Steroid-sparing properties of sargramostim in patients with corticosteroid-dependent Crohn's disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Gut. 2009 Oct. 58(10):1354-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Feuerstein JD, Nguyen GC, Kupfer SS, Falck-Ytter Y, Singh S, for the American Gastroenterological Association Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2017 Sep. 153 (3):827-34. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Satta R, Pes GM, Rocchi C, Pes MC, Dore MP. Is probiotic use beneficial for skin lesions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease?. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019 Sep. 30 (6):612-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Author

Specialty Editor Board

Chief Editor

Acknowledgements

BS Anand, MD Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Baylor College of Medicine

BS Anand, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Priyankha Balasundaram, MD Director, Kovai Heart Foundation, India; Resident Physician, Department of Surgery, Tulane University School of Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Marcy L Coash, DO Staff Physician, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Connecticut

Marcy L Coash, DO is a member of the following medical societies: American Medical Student Association/Foundation and American Osteopathic Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Senthil Nachimuthu , MD, FACP

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Waqar A Qureshi, MD Associate Professor of Medicine, Chief of Endoscopy, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Baylor College of Medicine and Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Waqar A Qureshi, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Gastroenterology, American College of Physicians, American Gastroenterological Association, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Priya Rangasamy, MD Fellow, Department of Gastroenterology/Hepatology, University of Connecticut Health Center

Priya Rangasamy, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Kathleen M Raynor, MD Staff Physician, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Connecticut School of Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Medscape Salary Employment

George Y Wu, MD, PhD Professor, Department of Medicine, Director, Hepatology Section, Herman Lopata Chair in Hepatitis Research, University of Connecticut School of Medicine

George Y Wu, MD, PhD is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American Gastroenterological Association, American Medical Association, American Society for Clinical Investigation, and Association of American Physicians

Disclosure: Springer Consulting fee Consulting; Gilead Consulting fee Review panel membership; Gilead Honoraria Speaking and teaching; Bristol-Myers Squibb Honoraria Speaking and teaching; Springer Royalty Review panel membership