Diminished neurokinin-1 receptor availability in patients with two forms of chronic visceral pain (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2015 Jan 14.

Abstract

Central sensitization and dysregulation of peripheral substance P and neurokinin-1 receptor (NK-1R) signaling are associated with chronic abdominal pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Although positron emission tomography (PET) has demonstrated that patients with injury-related chronic pain have diminished NK-1R availability in the brain, it is unknown whether these deficits are present in IBD and IBS patients, who have etiologically distinct forms of non-injury-related chronic pain. This study's aim was to determine if patients with IBD or IBS exhibit deficits in brain expression of NK-1Rs relative to healthy controls (HCs), the extent to which expression patterns differ across patient populations, and if these patterns differentially relate to clinical parameters. PET with [18F]SPA-RQ was used to measure NK-1R availability by quantifying binding potential (BP) in the 3 groups. Exploratory correlation analyses were performed to detect associations between NK-1R BP and physical symptoms. Compared to HCs, IBD patients had NK-1R BP deficits across a widespread network of cortical and subcortical regions. IBS patients had similar, but less pronounced deficits. BP in a subset of these regions was robustly related to discrete clinical parameters in each patient population. Widespread deficits in NK-1R BP occur in IBD and, to a lesser extent, IBS; however, discrete clinical parameters relate to NK-1R BP in each patient population. This suggests that potential pharmacological interventions that target NK-1R signaling may be most effective for treating distinct symptoms in IBD and IBS.

Keywords: PET, NK-1 receptor, Irritable bowel syndrome, Inflammatory bowel disease, Somatic pain, Quality of life

1. Introduction

Patients with chronic somatic pain exhibit functional and structural alterations in brain circuits that modulate cognitive and affective processes [4–6,33,38,78]. The relationship between chronic pain and neurotransmitters is less clear [4]. Substance P (SP), a neuropeptide that modulates effects of acute or chronically recurring physical and emotional distress, acts centrally and peripherally through neurokinin-1 receptors (NK-1Rs). NK-1Rs are expressed at high levels in brain regions implicated in pain and emotion regulation, including insula, cingulate cortex, dorsal pre-frontal cortex (PFC), amygdala, and striatum [29]. NK-1Rs have therefore been considered a promising pharmacological target for treating chronic pain and psychopathology [30,50]. Despite encouraging outcomes in patients with irritable bowel syndrome [39,76], clinical trials with NK-1R antagonists for depression and other chronic pain syndromes have been disappointing [25,37,52]. Disease-related specificity in NK-1R expression may contribute to these inconsistent findings.

SP modulates physical and emotional distress by differentially influencing NK-1R expression in the central nervous system. In rodents, acute nociceptive stimuli [2] and stress [59,70] produce a rapid release of SP in the spinal cord and brain [45,68]. The magnitude of SP release, and subsequent binding-related NK-1R downregulation, is proportional to the intensity and duration of the stimulus [2]. Conversely, chronic pain [1,35] and stress [9] upregulate NK-1Rs in the spinal cord, but downregulate NK-1Rs in limbic and striatal brain regions [17,74]. In humans, positron emission tomography (PET) studies show that patients with anxiety disorders [24,51] or injury-related chronic pain [42] have diminished NK-1R availability in amygdala and PFC, while SP is elevated in the cerebral spinal fluid [67] and plasma [3] of noninjured chronic pain patients. This suggests that chronic pain and emotional distress are associated with heightened SP release, indexed by elevated SP in cerebral spinal fluid and plasma, and reduced NK-1R availability in the brain, possibly related to SP-induced receptor downregulation. To develop effective treatments that target SP system dysfunction, it is critical to determine if this association exists across discrete patient populations.

In this pilot study, PET with the radioligand [18F]SPA-RQ was used to quantify availability of NK-1Rs in the brains of 2 patient populations with abdominal pain symptoms but discrete pathophysiology, namely inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). IBD is characterized by abdominal pain and discomfort due to intestinal inflammation during disease flares. IBS is characterized by chronic abdominal pain and discomfort that occurs without detectable pathology, but commonly in the presence of stress and comorbid psychopathology [47,48]. Our behavioral [57] and brain-based research [11,46] suggests that clinically remitted IBD patients have less abdominal pain and are better able to engage endogenous pain inhibition systems during acute aversive visceral stimulation compared to IBS patients. This difference in symptomatology may reflect differences in NK-1R expression in the brain. Here, we tested the extent to which NK-1R downregulation in the brain generalizes across, or is specific to, discrete chronic pain disorders, and the degree to which downregulation relates to clinical parameters.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants provided informed consent prior to enrolling in the study, which was approved by the institutional review board of the University of California, Los Angeles. Twenty-seven participants completed the study: 9 healthy controls (HCs); 9 IBS patients; and 9 IBD patients (see Table 1 for demographics). All were free of psychiatric illness as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV [22]), and of medication known to affect SP/NK-1R or central nervous system function, such as steroids and psychotropic medication. Self-reported medical history and physical examination supported that HCs were free of physical illness. Diagnosis of IBS or IBD (Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis) was verified via medical records. Patients had not been treated with biologics, and they discontinued steroidal or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication 2 weeks prior to the study. At the time of enrollment, patients with IBS were required to meet Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders [43], and underwent a rectal examination to ensure that symptoms were unrelated to physical abnormalities. Patients with IBD were not in an acutely active flare state as per clinical assessment by a gastroenterologist, rectal examination, and reflected by high scores on the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (M ± SD = 180.00 ± 25.24; full remission ≥ 170 [34]).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Healthy control | IBD | IBS | Group differences | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F | _P_-value | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| n (female/male) | 9/0 | 8/1 | 9/0 | |||||

| Age | 27.44 | 5.32 | 31.56 | 8.44 | 31.78 | 12.25 | 0.64 | 0.534 |

| Gastrointestinal symptom characteristics | ||||||||

| 24-hour symptom severity | – | – | 3.78 | 3.42 | 9.56 | 5.43 | 7.29 | 0.016 |

| Duration of symptoms (years) | – | – | 10.56 | 8.95 | 18.67 | 13.88 | 2.17 | 0.160 |

| Symptoms of anxiety and depression | ||||||||

| Anxiety (HAD) | 4.56 | 5.18 | 5.89 | 2.80 | 4.00 | 2.18 | 0.65 | 0.533 |

| Depression (HAD) | 2.89 | 4.17 | 1.78 | 1.86 | 2.45 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.417 |

| State anxiety (STAI) | 43.44 | 5.86 | 51.33 | 13.66 | 51.67 | 8.65 | 1.98 | 0.160 |

| Temperature for pain threshold (°C) | 46.69 | 2.86 | 45.33 | 1.49 | 46.35 | 2.28 | 0.87 | 0.432 |

2.2. PET acquisition

NK-1R availability was quantified with the radioligand [18F]SPA-RQ, a high-affinity NK-1R antagonist [29,58,73]. Images were acquired using a Siemens ECAT EXACT HR+ scanner (Siemens Healthcare Solutions, Deerfield, IL, USA: in-plane resolution full-width at half-maximum [FWHM] = 4.6 mm, axial FWHM = 3.5 mm, axial field of view = 15.52 cm) in 3-dimensional (3D) mode. A 7-minute transmission scan was acquired using a rotating 68Ge/68Ga rod source for attenuation correction. Dynamic data were acquired in list mode following a bolus injection of [18F]SPA-RQ (5 mCi in 30 seconds). After 85 minutes of data acquisition, participants were given a 13-minute break, and were then returned to the scanner bed. After a second transmission scan, dynamic data were collected for another 85 minutes. Thus, the total dynamic scanning sequence consisted of 170 1-minute frames, acquired continuously across both 85-minute blocks of scanning. Short-duration frames were utilized to minimize signal noise associated with within-frame head motion. Data were reconstructed using ECAT v7.3 software using the OSEM algorithm (Ordered Subset Expectation Maximization; 6 iterations, 16 subsets), correcting for decay, attenuation, and scatter.

2.3. Structural MRI acquisition

Participants also underwent structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with a 1.5-T Siemens SONATA scanner. A single, high-resolution sagittal T1-weighted 3D volumetric scan was acquired using a whole-brain MPRAGE sequence (repetition time/echo time = 25/11 ms, number of excitations = 1, slice thickness = 1.2 mm contiguous, in-plane resolution = 1 × 1 mm2). This anatomical scan was used for data registration in preprocessing (see 2.5.2), to improve anatomical localization of PET data.

2.4. Clinical parameters

2.4.1. Gastrointestinal and psychological symptom characteristics

2.4.1.1. Gastrointestinal symptoms

Symptom severity was assessed prior to scanning with a 20-point visual analogue scale used to rate unpleasantness of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms during the prior 24 hours [26]. Duration of illness was calculated using patient-reported year of symptom onset.

2.4.1.2. Psychological symptoms

SP system function is closely related to emotional processes [19,49], and IBS patients typically have high levels of comorbid anxiety and depression [47,48]. While participants who completed this study were free of diagnosable mental illness, anxiety and depression were nevertheless measured to determine if differences in NK-1R binding potential (BP) related to the presence of subclinical symptoms.

Anxiety and depression symptoms were assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD; [85]) scale. State anxiety was assessed prior to scanning with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; [72]). This 20-item questionnaire has scores that range from 20 to 80 (low to high symptom severity).

2.4.2. Sensitivity to acute somatic pain stimulus

As noted above, our prior work demonstrates that HCs, IBS, and IBD patients differ in their sensitivity to acute visceral stimuli [57], and in the neural circuits that such stimuli engage [46]. Therefore, we sought to determine whether pain threshold to an acute somatic pain stimulus differed across groups, and if NK-1R BP would be differentially related to this threshold.

Once PET scanning concluded, acute pain threshold was assessed. Participants received 3 consecutive thermal stimuli to the left volar forearm. Each stimulus began at a low temperature (30 °C), which then increased (0.5 °C/sec); participants indicated the temperature at which they first experienced pain with a button press. If pain threshold was not reached, the maximum temperature to safely apply brief thermal stimulation (51 °C) was recorded for that participant. To ensure consistency, this process was repeated 3 times. Pain threshold was defined as the average temperature to evoke pain.

2.5. Data analysis

2.5.1. Clinical parameters

Independent sample _t_-tests were conducted with SPSS v18 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) to determine if patient groups differed on current GI symptoms and duration of illness. Separate one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs), with group (HC, IBS, IBD) as a between-participant factor, were used to determine if the 3 groups differed on symptoms of anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to acute thermal stimulation. Planned comparisons were carried out for these measures to test whether patient groups differed from HCs (HC vs IBS; HC vs IBD), and whether patient groups differed from one another (IBD vs IBS).

2.5.2. PET data preprocessing

Preprocessing was carried out using PMOD software v3.2 (PMOD Technologies Ltd, Zurich, Switzerland). One-minute frames were binned together to generate a series of 27 frames (16 1-minute frames, 19 5-minute frames, 8 10-minute frames). The final 3-minutes from the first 85-minute scan block and last 5-minutes from the second 85-minute scan block were omitted to allow for consistent average frame duration across scan blocks. To correct for motion, the 27 averaged frames were realigned to a mean image, which was generated from the first 19 frames. Motion-corrected PET data were co-registered to each participant's structural MRI scan.

Whole-brain BP maps were used to quantify NK-1R availability. These maps were generated for each participant using a simplified reference tissue model 2 (SRTM2 [84]), implemented with PMOD's Pixel-wise Kinetic Modeling Tool (PMOD Technologies Ltd). Pixel-wise processing for SRTM2 requires k2′ estimates and time activity curves (TACs) from one region of interest (ROI) with a high level of receptor availability, in this case the putamen, and another with negligible receptor expression, in this case the cerebellum [29], to serve as a reference tissue. Bilateral putamen ROIs were delineated on each participant's anatomical MRI using a template-based method (FSL's [FMRIB Software Library] FMRIB [functional MRI of the brain] Integrated Registration and Segmentation Tool [FIRST]; Oxford University, Oxford UK). Unlike the putamen, NK-1R density in the cerebellum is negligible and homogeneous [29]. As such, cerebellar TACs can be derived from several consecutive slices, which reflect NK-1R density in the structure as a whole [51]. Here, bilateral cerebellum ROIs were manually delineated with cylindrical volumes (diameter = 15 mm; height = 5 mm). ROIs were transferred to the co-registered PET data, where TACs were extracted and input into the SRTM2 pixel-wise analysis to produce a whole-brain BP map for each participant.

2.5.3. Quantification of NK-1R BP

Structural MRI data were normalized into MNI (Montreal Neurological Institute) template space using SPM8 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm), and the transformation parameters were then applied to the coregistered whole-brain BP maps. BP maps were then smoothed with a Gaussian filter to 8-mm FWHM. A whole-brain BP map, averaged across all participants, was generated to depict overall NK-1R BP distribution.

2.5.4. Group comparison of BP values

2.5.4.1. Region of interest analyses

A priori ROIs were selected based on existing knowledge of brain regions critical for processing nociception in general, and visceral nociception in particular [4,9], and established NK-1R distribution [29]. Subcortical regions included striatum (putamen, caudate nucleus, and nucleus accumbens), globus pallidus, thalamus, hippocampus, and amygdala. Cortical regions included insula, cingulate cortex, dorsolateral (dlPFC), ventrolateral (vlPFC), and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). All regions were delineated with the WFU Pickatlas (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA; Version 2.4 [44]). Distinct regions of the cingulate cortex (reviewed by [79]) and insula (reviewed by [13]) have been implicated in pain and emotion-based processes. Thus, the cingulate cortex was parsed into perigenual anterior cingulate cortex, anterior aspect of mid cingulate cortex (MCC), and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) [80]; the insula was parsed into anterior, mid, and posterior sections [15]. Average BP was calculated for each ROI bilaterally, yielding a single BP value for each of the 7 subcortical and 9 cortical ROIs. In addition, weighted average BP was calculated for all subcortical and cortical ROIs. These weighted averages approximate global subcortical and cortical BP in each group, while controlling for variability in the size (number of voxels) of each structure.

ROI data were imported into SPSS v18 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) to test for group differences in BP. Planned linear contrasts were calculated based on estimated group means from a general linear model, which specified group as an independent factor (HC, IBS, IBD) and average BP as the dependent variable for each ROI. For each analysis, F–tests were used to evaluate each of the 3 planned comparisons. A modified Bonferroni procedure was used to control the familywise type I error rate for the 3 comparisons at P < 0.05 [31].

The sample size of the current study was small, which could potentially limit our ability to detect significant differences between the groups, despite the presence of medium-to-large effect sizes. Therefore, to further characterize group differences in subcortical and cortical ROIs, combinatorial analyses were conducted to determine how many regions in the HC group exceeded the expected corresponding values in each patient group. This was done by calculating the exact binomial probability under the null hypothesis that BPs in each ROI across all groups are equivalent [81].

2.5.4.2. Exploratory whole-brain analyses

To help inform future research on the relationship between NK-1Rs and chronic pain, an exploratory whole-brain analysis was performed with SPM8 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm), using a one-way ANOVA with group (HC, IBS, IBD) as a between-participant factor. Planned comparisons were carried out to test whether BP differed in each patient group compared to HCs (HC vs IBS; HC vs IBD), and whether BP differed between patient groups (IBD vs IBS). Student t maps for these comparisons were generated using a height threshold of P < 0.001 with a 20-voxel extent threshold. This combination of threshold parameters yields a desirable balance between Type I and Type II error rates for exploratory analyses [41], which are appropriate given the preliminary nature of this study.

2.5.5. Exploratory analyses relating clinical parameters and NK-1R BP

To better understand the clinical relevance of NK-1R BP, and to inform future clinical studies on NK-1Rs and chronic pain, exploratory correlational analyses between NK-1R BP in ROIs were conducted for GI symptom characteristics in each patient group. The relationship between NK-1R BP in ROIs, scores on the HAD and STAI, and sensitivity to acute somatic pain was assessed in HCs as well as IBD and IBS patients. A modified Bonferroni procedure was used to control the type I error rate at P < 0.05 for the 16 ROIs examined, for each variable tested [31].

3. Results

3.1. Clinical parameters

Participant characteristics and accompanying statistics are described in Table 1. Patients with IBS reported more severe GI symptoms than patients with IBD. Duration of symptoms did not differ across patient groups. HCs, IBS, and IBD patients did not differ in symptoms of depression or anxiety, or in their sensitivity to an acute somatic pain stimulus.

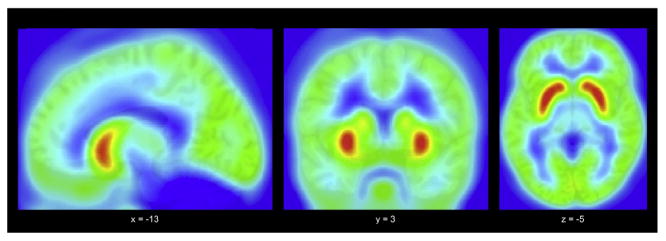

3.2. Overall NK-1R BP distribution

A whole-brain BP map, averaged across all participants, depicts overall NK-1R BP distribution (Fig. 1). In each group, NK-1R BP for ROIs (see Table 2A) follows the same pattern as described in the literature [24,29,58], with striatal regions (putamen, caudate, and nucleus accumbens) exhibiting the highest NK-1R BP, followed by globus pallidus, amygdala, and insula, then anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), PFC (dlPFC, vlPFC, and mPFC), followed by thalamus and hippocampus.

Fig. 1.

Average whole-brain neurokinin-1 receptor binding potential across all participants.

Table 2.

NK-1 receptor BP for each group in subcortical and cortical regions of interest (A). Group differences in NK-1 Receptor BP (B).

| Region | A) | B) | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy control | IBD | IBS | Healthy control vs IBD | Healthy control vs IBS | IBS vs IBD | ||||||||||||||||

| Mean BP | SD | Mean BP | SD | Mean BP | SD | F | _P_-value | ES+ | 95% CI | F | _P_-value | ES+ | 95% CI | F | _P_-value | ES+ | 95% CI | ||||

| − | + | − | + | − | + | ||||||||||||||||

| Subcortical ROIs | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Putamen | 3.96 | 0.42 | 2.99 | 0.57 | 3.30 | 0.81 | 11.00 | 0.003* | 2.06 | −3.20 | −0.91 | 5.04 | 0.034 | 1.09 | −2.07 | −0.10 | 1.15 | 0.294 | 0.47 | −1.41 | 0.47 |

| Caudate nucleus | 2.97 | 0.59 | 2.21 | 0.60 | 2.38 | 0.80 | 5.86 | 0.023 | 1.35 | −2.38 | −0.33 | 3.47 | 0.075 | 0.89 | −1.86 | 0.08 | 0.31 | 0.583 | 0.26 | −1.18 | 0.67 |

| Nucleus accumbens | 3.83 | 0.48 | 3.09 | 0.55 | 3.54 | 0.44 | 10.06 | 0.004* | 1.52 | −2.57 | −0.47 | 1.53 | 0.228 | 0.67 | −1.62 | 0.28 | 3.74 | 0.065 | 0.96 | 0.74 | 2.95 |

| Globus pallidus | 1.93 | 0.26 | 1.56 | 0.28 | 1.74 | 0.27 | 8.42 | 0.008* | 1.45 | −2.49 | −0.41 | 2.14 | 0.157 | 0.76 | −1.72 | 0.20 | 2.08 | 0.163 | 0.69 | −1.65 | 0.26 |

| Thalamus | 1.14 | 0.23 | 0.95 | 0.17 | 1.07 | 0.21 | 3.75 | 0.065 | 1.00 | −1.98 | −0.02 | 0.47 | 0.500 | 0.34 | −1.27 | 0.59 | 1.57 | 0.222 | 0.67 | −1.62 | 0.28 |

| Hippocampus | 1.14 | 0.13 | 0.91 | 0.15 | 1.03 | 0.18 | 10.30 | 0.004* | 1.74 | −2.82 | −0.65 | 2.61 | 0.119 | 0.74 | −1.70 | 0.21 | 2.54 | 0.124 | 0.77 | −1.73 | 0.19 |

| Amygdala | 1.81 | 0.20 | 1.42 | 0.25 | 1.65 | 0.20 | 14.20 | 0.001* | 1.83 | −2.93 | −0.73 | 2.45 | 0.130 | 0.85 | −1.81 | 0.12 | 4.85 | 0.037 | 1.08 | −2.07 | −0.09 |

| Weighted average | 2.30 | 0.26 | 1.78 | 0.30 | 1.97 | 0.42 | 10.95 | 0.003* | 1.96 | 0.006 | 0.661 | 4.24 | 0.046 | 1.00 | −0.14 | 0.52 | 1.45 | 0.240 | 0.55 | −0.14 | 0.52 |

| Cortical ROIs | |||||||||||||||||||||

| dlPFC | 1.35 | 0.18 | 1.29 | 0.16 | 1.39 | 0.13 | 0.47 | 0.500 | 0.37 | −1.31 | 0.56 | 0.36 | 0.552 | 0.27 | −0.66 | 1.20 | 1.65 | 0.211 | 0.73 | −1.68 | 0.23 |

| vlPFC | 1.57 | 0.21 | 1.51 | 0.19 | 1.59 | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.528 | 0.32 | −1.25 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.824 | 0.10 | −0.82 | 1.03 | 0.75 | 0.395 | 0.43 | −1.37 | 0.50 |

| mPFC | 1.43 | 0.17 | 1.35 | 0.17 | 1.45 | 0.15 | 1.34 | 0.277 | 0.50 | −1.44 | 0.44 | 0.07 | 0.788 | 0.13 | −0.79 | 1.06 | 1.92 | 0.179 | 0.66 | −1.61 | 0.29 |

| Perigenual ACC | 1.70 | 0.18 | 1.46 | 0.17 | 1.54 | 0.17 | 8.73 | 0.007* | 1.45 | −2.49 | −0.42 | 4.19 | 0.05 | 0.97 | −1.95 | 0.007 | 0.83 | 0.373 | 0.50 | −1.44 | 0.44 |

| Anterior MCC | 1.70 | 0.20 | 1.46 | 0.19 | 1.49 | 0.14 | 8.20 | 0.009* | 1.30 | −2.32 | −0.29 | 5.86 | 0.023 | 1.29 | −2.31 | −0.27 | 0.20 | 0.662 | 0.19 | −1.12 | 0.74 |

| PCC | 1.69 | 0.15 | 1.60 | 0.21 | 1.67 | 0.21 | 1.18 | 0.289 | 0.52 | −1.46 | 0.42 | 0.07 | 0.792 | 0.12 | −1.04 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.422 | 0.36 | −1.29 | 0.57 |

| Anterior insula | 1.72 | 0.20 | 1.52 | 0.21 | 1.62 | 0.27 | 3.43 | 0.077 | 1.03 | −2.02 | −0.05 | 0.82 | 0.375 | 0.45 | −1.38 | 0.49 | 0.90 | 0.353 | 0.44 | −1.37 | 0.50 |

| Mid insula | 1.76 | 0.20 | 1.50 | 0.19 | 1.64 | 0.27 | 5.87 | 0.023 | 1.41 | −2.45 | −0.38 | 1.09 | 0.306 | 0.54 | −1.48 | 0.41 | 1.90 | 0.181 | 0.64 | −1.58 | 0.31 |

| Posterior insula | 1.77 | 0.19 | 1.51 | 0.20 | 1.65 | 0.23 | 7.20 | 0.013 | 1.41 | −2.45 | −0.38 | 1.56 | 0.223 | 0.60 | −1.55 | 0.34 | 2.06 | 0.165 | 0.69 | −1.64 | 0.26 |

| Weighted average | 1.46 | 0.18 | 1.33 | 0.17 | 1.43 | 0.14 | 3.18 | 0.087 | 0.79 | −0.02 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.731 | 0.20 | −0.13 | 0.18 | 2.06 | 0.164 | 0.68 | −0.05 | 0.27 |

3.3. Group comparison of BP values

3.3.1. Region of interest analyses

Across subcortical ROIs, NK-1R BP was ∼20% lower in IBD patients than HCs, and ∼10% lower in IBS patients than HCs. Across cortical ROIs, NK-1R BP was ∼7% lower in IBD patients than HCs, and showed a general tendency to be lower in IBS patients in 6 of 9 regions. Thus, IBD patients appear to have global reductions of NK-1R BP, while patients with IBS have less pronounced reductions in NK-1R BP.

For each ROI, mean effect size differences between groups and 95% confidence intervals are presented in Table 2B. Planned comparisons show that patients with IBD exhibited significantly lower NK-1R BP than HCs in several subcortical regions, including putamen, nucleus accumbens, globus pallidus, hippocampus, and amygdala, as well as cortical regions including perigenual ACC and anterior MCC (all _F_s > 8.19). The same pattern was observed in the caudate nucleus, mid insula, and posterior insula; however, these differences did not survive statistical correction. Relative to HCs, patients with IBS tended to exhibit lower NK-1R BP. While these differences did not reach statistical significance with or without correction, the medium (d = 0.5–0.6) to large (d > 0.8) effect sizes observed across most ROIs suggest that the failure to reach significance is likely a consequence of the modest sample size. A similar pattern of results was observed when comparing the patient samples to one another. Patients with IBD exhibited lower NK-1R BP than patients with IBS. As with the above comparisons, these differences did not reach statistical significance, but medium-to-large effect size differences were observed across most ROIs.

Given that medium-to-large effects were detected in some planned comparisons, but failed to reach significance, likely due to small sample size, combinatorial analyses were performed to provide additional support for group differences in NK-1R BP. The probability that, for all 7 subcortical regions, patients with IBD or IBS would demonstrate lower NK-1R BP than HCs exhibit is P = 0.016. For the cortical regions, the probability that patients with IBD would demonstrate lower NK-1R BP than HCs in all 9 regions is P = 0.004. In contrast, the probability that patients with IBS would have lower NK-1R BP than HCs in 6 of 9 cortical regions is P = 0.32.

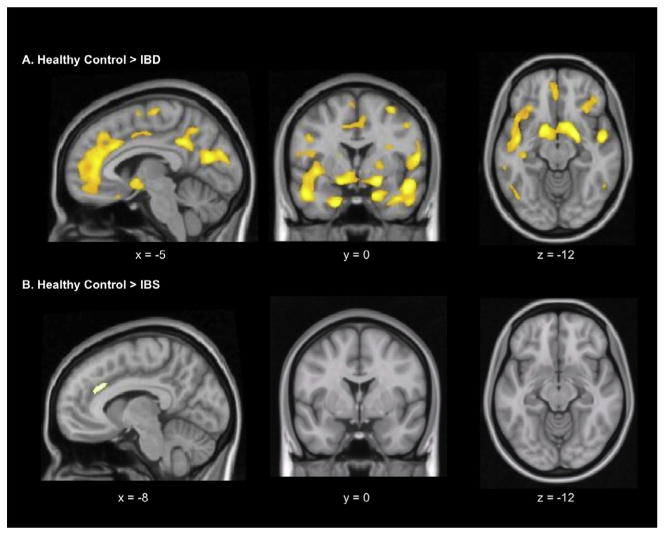

3.3.2. Exploratory whole brain analysis

A whole-brain, voxel-wise, one-way ANOVA confirmed the group differences observed with linear contrast ROI analyses, and also revealed additional group differences. Fig. 2A depicts regions with lower NK-1R BP in patients with IBD relative to HCs. In addition to cortical regions and subcortical structures identified with ROI analyses, further differences emerged throughout temporal and parietal regions of the brain (Supplementary Table 1). A comparison between HCs and IBS patients revealed significantly lower NK-1R BP in patients with IBS in a small region of anterior MCC (Fig. 2B), which was not detected with ROI analyses. Neither patient group had greater NK-1R BP than HCs in any region of the brain.

Fig. 2.

Whole-brain voxel-wise statistical parametric mapping analysis depicting regions with lower levels of neurokinin-1 receptor binding in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (A) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients (B), relative to healthy controls (voxel extent threshold P < 0.001; cluster extent threshold > 20).

3.4. Exploratory analyses relating clinical parameters and NK-1R BP

3.4.1. Gastrointestinal and psychological symptom characteristics

3.4.1.1. Gastrointestinal symptom severity (Table 3A)

Table 3.

Correlation between NK-1R BP in regions of interest and: symptom severity (A); duration of illness (B); and sensitivity to thermal stimulation (C).

| Region | A) Symptom severity | B) Duration of illness | C) Temperature for pain threshold | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBD | IBS | IBD | IBS | Healthy control | IBD | IBS | |

| r | r | r | r | r | r | r | |

| Subcortical ROIs | |||||||

| Putamen | −0.65 | −0.07 | −0.25 | −0.76* | 0.38 | 0.18 | −0.43 |

| Caudate | −0.63 | −0.06 | −0.35 | −0.83* | 0.44 | 0.42 | −0.48 |

| Nucleus accumbens | −0.39 | −0.33 | −0.23 | −0.58 | 0.26 | 0.06 | −0.47 |

| Globus pallidus | −0.23 | −0.12 | 0.46 | 0.03 | −0.25 | 0.06 | −0.07 |

| Thalamus | −0.45 | 0.28 | 0.38 | −0.19 | −0.48 | −0.19 | −0.25 |

| Hippocampus | −0.19 | −0.34 | −0.13 | −0.28 | −0.86** | 0.26 | −0.37 |

| Amygdala | −0.61 | −0.49 | −0.07 | −0.67 | −0.40 | 0.28 | −0.22 |

| Average of ROIs | −0.66 | −0.07 | −0.19 | −0.72* | 0.14 | 0.26 | −0.45 |

| Cortical ROIs | |||||||

| dlPFC | −0.09 | 0.29 | 0.44 | −0.59 | −0.18 | 0.11 | −0.94** |

| vlPFC | −0.23 | 0.15 | 0.06 | −0.63 | −0.30 | −0.17 | −0.70 |

| mPFC | −0.49 | 0.11 | 0.23 | −0.68 | −0.26 | −0.09 | −0.80* |

| Perigenual ACC | −0.77* | 0.21 | −0.02 | −0.64 | −0.26 | 0.01 | −0.63 |

| Anterior MCC | −0.69* | 0.10 | 0.27 | −0.65 | −0.22 | 0.08 | −0.52 |

| PCC | −0.74 | 0.00 | 0.17 | −0.59 | −0.07 | −0.05 | −0.80* |

| Anterior INS | −0.90** | 0.16 | 0.10 | −0.80* | −0.24 | 0.09 | −0.58 |

| Mid INS | −0.90** | 0.08 | 0.16 | −0.85* | −0.22 | 0.20 | −0.51 |

| Posterior INS | −0.75 | 0.16 | 0.15 | −0.83* | −0.38 | 0.06 | −0.61 |

| Average of ROIs | −0.63 | 0.05 | 0.22 | −0.70 | −0.29 | 0.06 | −0.62 |

Among patients with IBD, GI symptom severity on the day of scanning was highly negatively correlated with average NK-1R BP in anterior and mid insula (_r_s = −0.90) and perigenual ACC (r=-0.77), indicating that lower NK-1R BP was associated with more unpleasant abdominal symptoms in the period immediately prior to scanning. This relationship was not observed in patients with IBS (Supplemental Fig. 1).

3.4.1.2. Duration of gastrointestinal symptoms (Table 3B)

Among patients with IBS, duration of symptoms was negatively correlated with average NK-1R BP in caudate nucleus, putamen, each aspect of insula, and the weighted average for cortical ROIs (_r_s < −0.72). This relationship was not observed in patients with IBD (Supplemental Fig. 2).

3.4.1.3. Psychological symptoms

NK-1R BP was not related to state or trait anxiety, or depression symptoms in any group.

3.4.2. Sensitivity to somatic pain stimulus

As described in Table 3C, for patients with IBS, temperature required to elicit pain was negatively correlated with NK-1R BP in dlPFC, mPFC, and PCC (_r_s ≤ −0.80; Supplemental Fig. 3). A negative relationship was also observed in HCs for the hippocampus. In IBD, there was no relationship between sensitivity to pain and NK-1R BP.

4. Discussion

Despite its modest sample size, this pilot study demonstrates that patients with IBD and, to a lesser extent, IBS have diminished NK-1R availability in brain regions that play key roles in nociception and affective processes. Moreover, clinical parameters in each patient group differentially relate to NK-1R availability. Together, these findings may help explain why NK-1R antagonists have had relatively little success in treating patients with chronic pain and emotional disorders.

4.1. NK-R1 availability in IBD patients

IBD patients exhibited low NK-1R availability in brain regions that modulate nociceptive and affective processes (eg, ACC, anterior MCC, amygdala [4,5,33,61,80]). These findings are consistent with deficits found in patients with short-term, injury-related chronic pain [42]. Unlike those with injury-related pain, IBD patients also had diminished NK-1R availability in striatum, a region that is increasingly associated with pain processing [40]. Lower NK-1R availability may reflect higher levels of SP in brain regions that receive nociceptive signals from gut inflammation, or that are engaged to modulate such signals. As suggested previously [46], nociceptive signals from the gut heighten engagement of endogenous pain inhibition systems in IBD compared to IBS patients, which could modulate the experience of GI symptom severity.

Indeed, IBD patients reported milder symptoms than IBS patients; however, IBD patients with more severe symptoms had fewer NK-1Rs available in regions implicated in pain processing. Between-group differences emerged in the relationship between severity of symptoms and NK-1R availability in the insula, a key region implicated in pain processing (reviewed by [14,23]) and endogenous pain inhibition [12,63,82]. This is consistent with symptom-related SP release, suggesting that deficits in NK-1R availability in IBD may correspond with NK-1R endocytosis.

4.2. NK-R1 availability in IBS patients

IBS patients had diminished NK-1R availability relative to HCs, but greater availability than IBD patients. These differences were characterized by medium-to-large size effects, but likely due to small sample size, did not reach statistical significance.

IBS patients reported more severe GI symptoms than IBD patients; but these symptoms were not related to NK-1R availability. Instead, NK-1R availability was associated with duration of illness; patients with longer illnesses had lower NK-1R availability in putamen, caudate nucleus, and insula, a relationship not observed in IBD patients. Thus, in IBS patients, the cumulative experience of illness, not current symptoms, may be more closely related to SP/NK-1R signaling. Thus, diminished NK-1R availability in IBS patients may reflect a gradual loss of NK-1Rs or reduced genetic expression for NK-1R, as seen in the insula of rodent models of chronic pain and stress [16].

In IBS, heightened sensitivity to noxious somatic stimulation (ie, lower temperature required to evoke pain) was associated with greater NK-1R availability in dlPFC, mPFC, and PCC, a relationship not observed in patients with IBD or HCs. This finding suggests that dysregulation in short-term or acute SP/NK-1R system function may contribute to the visceral hypersensitivity that IBS patients experience when confronted with noxious or stressful contexts. This finding is also consistent with functional neuroimaging studies, which show that IBS patients do not engage PFC to the same extent as HCs or IBD patients while anticipating noxious visceral stimulation [46,56]. Moreover, when IBS patients are treated with NK-1R antagonists, they report attenuated pain to acute visceral stimulation [39,76], coupled with reduced activity in amygdala, hippocampus, and ACC [76], regions associated with nociceptive processing that have high levels of NK-1R expression.

IBS patients often have comorbid anxiety or depression [10,36,71], which potentiate GI symptoms [20]. NK-1R availability did not relate to symptoms of anxiety and depression in the current sample of psychiatrically healthy patients. However, prior work shows that in IBS patients, NK-1R antagonists reduce functional activity in the insula during acute visceral stimulation, but only to the extent that symptoms of anxiety are alleviated [76]. Together, these data suggest that central SP/NK-1R signaling in IBS patients is dysregulated in response to acute aversive stimuli, and that this heightened sensitivity may be associated with the emotional modulation of pain.

4.3. Interpreting diminished NK-1R availability

It is important to note that NK-1R availability is determined by several nonmutually exclusive factors. Diminished availability may reflect NK-1R endocytosis following release of SP [45]. SP release can occur in response to noxious stimulation in visceral afferents [66,68], psychological distress [18], or both [9], but may also result from increased engagement of endogenous pain or stress inhibition systems [7,55,60]. Indeed, previous PET studies have found that injury-related chronic pain patients have a dysregulated relationship between functional activity and NK-1R availability in brain regions critical to both the detection and modulation of pain [42].

Variations in NK-1R gene expression can lower the rate of NK-1R expression by reducing receptor insertion into the plasma membrane. These variations may be unrelated to a primary disease, but may also reflect disease-related changes in gene transcription [69]. For example, in a rodent model of chronic inflammatory pain, NK-1R gene expression is downregulated in insula and hippocampus, but upregulated in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord [17], an effect that also occurs in the spinal cord following noninflammatory chronic stress [9,16].

4.4. Limitations

Central limitations of the study included small sample size and inclusion of only one male participant. While chronic pain syndromes are more common in women than men [32,53], NK-1R availability also varies with sex [21,58]. It is also possible that different results would emerge if IBD patients were studied in an acute disease flare instead of the remitted state in which they were studied here. Likewise, because the patient groups differed in current symptom severity, it is unclear whether differences in NK-1R availability were due to pathophysiological differences intrinsic to each illness, or to the experience of symptoms at the time of study. Moreover, while some evidence suggests that expression of SP or NK-1R in the gastrointestinal tract is heightened in patients with IBD (reviewed by [27]), it is difficult to speculate about how elevated peripheral expression of SP or NK-1R may relate to the current findings. To tease apart these relationships, future large-scale studies should match patients based on gender and symptom severity, and utilize PET in conjunction with quantification of SP/NK-1R expression in colonic mucosa. Finally, to limit the already considerable number of statistical tests performed, brainstem structures such as periaqueductal grey, which has high levels of NK-1R binding [29] and is implicated in descending inhibitory pain [4], were not included in ROI analyses. However, whole brain exploratory analyses suggest that NK-1R availability in brainstem does not differ for HCs, IBD, or IBS patients.

4.5. Clinical implications and future directions

Although preclinical studies suggest that NK-1R antagonists effectively treat chronic pain, anxiety, and depression, translation to humans has been less promising [25,37,52,65]. These outcomes may reflect the fact that central SP/NK-1R system function differentially modulates discrete diseases and symptoms. In the present study, NK-1R availability in the insula was closely related to GI symptoms in IBD patients, but to duration of illness in IBS patients, whereas NK-1R availability in dlPFC was related to sensitivity to acute somatic stimuli in patients with IBS. These differences may have direct clinical implications. For example, an NK-1R antagonist relieved pain, anxiety, and negative affect during acute visceral stimulation in IBS patients, but did not effectively reduce IBS-specific symptoms [76]. Thus, for IBS, NK-1R antagonists may effectively treat dysregulation in SP/NK-1R system function associated with acute pain and stress, but not long-term dysregulation that may emerge over the course of illness. Such treatment may be useful for patients with secondary symptoms of anxiety related to their chronic pain. For example, NK-1R antagonists may effectively treat fear of movement among patients with chronic short-term pain from acute trauma, which is associated with reduced NK-1R availability in ventromedial PFC [42].

Finally, while upregulation of spinal NK-1Rs in response to neuropathic or inflammatory pain increases spino-bulbo-spinal pain facilitation, inducing persistent hyperalgesia [77,83], implications of downregulated NK-1Rs in the brain on other neurotransmitter systems are not well understood. For example, NK-1Rs are expressed on glial cells, serotonergic, and noradrenergic neurons [54,62,75]. Chronic stress [9] or inflammation [28] increases glial NK-1R expression and SP/NK-1R signaling in neurons, while chronic NK-1R antagonism increases 5-HT transmission in hippocampus [8]. Increased 5-HT transmission may, in turn, modulate the experience of pain [64]. Further research is clearly needed to determine how this complex relationship affects treatment outcomes.

In summary, this pilot study identified group differences in NK-1R availability in HCs and patients with etiologically distinct chronic pain, and in the relationship between clinical characteristics and NK-1R availability. Taken together with existing work demonstrating that IBS and IBD patients differ in functional brain responses to acute visceral stimuli [46], these data suggest that dysregulation in SP/NK-1 signaling may be disease and symptom-state specific. While many questions remain, these findings promote the hypothesis that, in contrast to the well-documented upregulation of the SP/NK-1R system in the spinal cord, NK-1Rs in the brain are differentially downregulated in chronic pain syndromes. This differential regulation of NK-1Rs in discrete diseases and symptoms, in anatomically distinct regions of the central nervous system, may help explain the results of clinical trials with NK-1R antagonists.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table and Figures S1-S3

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants F31-DA021951, T32-MH017140 (J.M.J.), F31– DA028812 (S.M.G.), NIH AT00268 (E.A.M.), and endowments from the Marjorie Greene Family Trust and National Institute on Drug Abuse (A.L.B. [R01 DA20872]), the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (A.L.B. [19XT-0135]), the Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development (Merit Review Award [A.L.B.]), and the Thomas P. and Katherine K. Pike Chair in Addiction Studies (E.D.L.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Abbadie C, Brown JL, Mantyh PW, Basbaum AI. Spinal cord substance P receptor immunoreactivity increases in both inflammatory and nerve injury models of persistent pain. Neuroscience. 1996;70:201–9. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00343-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen BJ, Rogers SD, Ghilardi JR, Menning PM, Kuskowski MA, Basbaum AI, Simone DA, Mantyh PW. Noxious cutaneous thermal stimuli induce a graded release of endogenous substance P in the spinal cord: imaging peptide action in vivo. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5921–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05921.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alpar EK, Onuoha G, Killampalli VV, Waters R. Management of chronic pain in whiplash injury. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:807–11. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b6.12738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apkarian AV, Bushnell MC, Treede RD, Zubieta JK. Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur J Pain. 2005;9:463–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baliki MN, Chialvo DR, Geha PY, Levy RM, Harden RN, Parrish TB, Apkarian AV. Chronic pain and the emotional brain: specific brain activity associated with spontaneous fluctuations of intensity of chronic back pain. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12165–73. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3576-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berman SM, Naliboff BD, Suyenobu B, Labus JS, Stains J, Ohning G, Kilpatrick L, Bueller JA, Ruby K, Jarcho J, Mayer EA. Reduced brainstem inhibition during anticipated pelvic visceral pain correlates with enhanced brain response to the visceral stimulus in women with irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurosci. 2008;28:349–59. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2500-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bester H, De Felipe C, Hunt SP. The NK1 receptor is essential for the full expression of noxious inhibitory controls in the mouse. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1039–46. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-01039.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blier P, Gobbi G, Haddjeri N, Santarelli L, Mathew G, Hen R. Impact of substance P receptor antagonism on the serotonin and norepinephrine systems: relevance to the antidepressant/anxiolytic response. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2004;29:208–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradesi S, Svensson CI, Steinauer J, Pothoulakis C, Yaksh TL, Mayer EA. Role of spinal microglia in visceral hyperalgesia and NK1R up-regulation in a rat model of chronic stress. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1339–48. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.044. e1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canavan JB, Bennett K, Feely J, O'Morain CA, O'Connor HJ. Significant psychological morbidity occurs in irritable bowel syndrome: a case-control study using a pharmacy reimbursement database. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:440–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang L, Munakata J, Mayer EA, Schmulson MJ, Johnson TD, Bernstein CN, Saba L, Naliboff B, Anton PA, Matin K. Perceptual responses in patients with inflammatory and functional bowel disease. Gut. 2000;47:497–505. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craggs JG, Price DD, Verne GN, Perlstein WM, Robinson MM. Functional brain interactions that serve cognitive-affective processing during pain and placebo analgesia. Neuroimage. 2007;38:720–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:655–66. doi: 10.1038/nrn894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craig AD. Pain mechanisms: labeled lines versus convergence in central processing. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2003;26:1–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craig AD, Chen K, Bandy D, Reiman EM. Thermosensory activation of insular cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:184–90. doi: 10.1038/72131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Lange RPJ, Wiegant VM, Stam R. Altered neuropeptide Y and neurokinin messenger RNA expression and receptor binding in stress-sensitised rats. Brain Res. 2008;1212:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duric V, McCarson KE. Neurokinin-1 (NK-1) receptor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene expression is differentially modulated in the rat spinal dorsal horn and hippocampus during inflammatory pain. Mol Pain. 2007;3:32. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-3-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebner K, Muigg P, Singewald G, Singewald N. Substance P in stress and anxiety: NK-1 receptor antagonism interacts with key brain areas of the stress circuitry. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1144:61–73. doi: 10.1196/annals.1418.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ebner K, Sartori SB, Singewald N. Tachykinin receptors as therapeutic targets in stress-related disorders. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:1647–74. doi: 10.2174/138161209788168074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elsenbruch S, Rosenberger C, Enck P, Forsting M, Schedlowski M, Gizewski ER. Affective disturbances modulate the neural processing of visceral pain stimuli in irritable bowel syndrome: an fMRI study. Gut. 2010;59:489–95. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.175000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engman J, Ahs F, Furmark T, Linnman C, Pissiota A, Appel L, Frans O, Langstrom B, Fredrikson M. Age, sex and NK1 receptors in the human brain – a positron emission tomography study with [(11)C]GR205171. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22:562–8. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friebel U, Eickhoff SB, Lotze M. Coordinate-based meta-analysis of experimentally induced and chronic persistent neuropathic pain. Neuroimage. 2011;58:1070–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujimura Y, Yasuno F, Farris A, Liow JS, Geraci M, Drevets W, Pine DS, Ghose S, Lerner A, Hargreaves R, Burns HD, Morse C, Pike VW, Innis RB. Decreased neurokinin-1 (substance P) receptor binding in patients with panic disorder: positron emission tomographic study with [18F]SPA-RQ. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:94–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldstein DJ, Wang O, Saper JR, Stoltz R, Silberstein SD, Mathew NT. Ineffectiveness of neurokinin-1 antagonist in acute migraine: a crossover study. Cephalalgia. 1997;17:785–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1707785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gracely RH. Psychophysical assessment of human pain. Adv Pain Res Ther. 1979;3:805–24. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross KJ, Pothoulakis C. Role of neuropeptides in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:918–32. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo W, Wang H, Watanabe M, Shimizu K, Zou S, LaGraize SC, Wei F, Dubner R, Ren K. Glial-cytokine-neuronal interactions underlying the mechanisms of persistent pain. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6006–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0176-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hietala J, Nyman MJ, Eskola O, Laakso A, Grönroos T, Oikonen V, Bergman J, Haaparanta M, Forsback S, Marjamäki P, Lehikoinen P, Goldberg M, Burns D, Hamill T, Eng WS, Coimbra A, Hargreaves R, Solin O. Visualization and quantification of neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptors in the human brain. Mol Imaging Biol. 2005;7:262–72. doi: 10.1007/s11307-005-7001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hökfelt T, Bartfai T, Bloom F. Neuropeptides: opportunities for drug discovery. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:463–72. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hurley RW, Adams MC. Sex, gender, and pain: an overview of a complex field. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:309–17. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0b013e31816ba437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iannetti GD, Mouraux A. From the neuromatrix to the pain matrix (and back) Exp Brain Res. 2010;205:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00221-010-2340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irvine EJ, Feagan B, Rochon J, Archambault A, Fedorak RN, Groll A, Kinnear D, Saibil F, McDonald JW. Quality of life: a valid and reliable measure of therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Canadian Crohn's Relapse Prevention Trial Study Group. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:287–96. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90585-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishigooka M, Zermann DH, Doggweiler R, Schmidt RA, Hashimoto T, Nakada T. Spinal NK1 receptor is upregulated after chronic bladder irritation. PAIN®. 2001;93:43–50. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00288-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jarrett ME, Burr RL, Cain KC, Hertig V, Weisman P, Heitkemper MM. Anxiety and depression are related to autonomic nervous system function in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:386–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1021904216312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keller M, Montgomery S, Ball W, Morrison M, Snavely D, Liu G, Hargreaves R, Hietala J, Lines C, Beebe K, Reines S. Lack of efficacy of the substance p (neurokinin1 receptor) antagonist aprepitant in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:216–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee MC, Tracey I. Unravelling the mystery of pain, suffering, and relief with brain imaging. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14:124–31. doi: 10.1007/s11916-010-0103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee OY, Munakata J, Naliboff BD, Chang L, Mayer EA. A double blind parallel group pilot study of the effects of CJ-11,974 and placebo on perceptual and emotional responses to rectosigmoid distension in IBS patients. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:A846. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leknes S, Tracey I. A common neurobiology for pain and pleasure. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:314–20. doi: 10.1038/nrn2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lieberman MD, Cunningham WA. Type I and Type II error concerns in fMRI research: re-balancing the scale. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2009;4:423–8. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Linnman C, Appel L, Furmark T, Söderlund A, Gordh T, Långström B, Fredrikson M. Ventromedial prefrontal neurokinin 1 receptor availability is reduced in chronic pain. PAIN®. 2010;149:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JH. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1233–9. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mantyh PW. Neurobiology of substance P and the NK1 receptor. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mayer EA, Berman S, Suyenobu B, Labus J, Mandelkern MA, Naliboff BD, Chang L. Differences in brain responses to visceral pain between patients with irritable bowel syndrome and ulcerative colitis. PAIN®. 2005;115:398–409. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mayer EA, Gebhart GF. Basic and clinical aspects of visceral hyperalgesia. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:271–93. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mayer EA, Raybould HE. Role of visceral afferent mechanisms in functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1688–704. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90475-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCabe C, Cowen PJ, Harmer CJ. NK1 receptor antagonism and the neural processing of emotional information in healthy volunteers. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:1261–74. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709990150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mensah-Nyagan AG, Meyer L, Schaeffer V, Kibaly C, Patte-Mensah C. Evidence for a key role of steroids in the modulation of pain. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:S169–77. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michelgård A, Appel L, Pissiota A, Frans O, Långström B, Bergström M, Fredrikson M. Symptom provocation in specific phobia affects the substance P neurokinin-1 receptor system. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:1002–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Michelson D, Hargreaves R, Alexander R, Ceesay P, Hietala J, Lines C, Reines S. Lack of efficacy of L-759274, a novel neurokinin 1 (substance P) receptor antagonist, for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mogil JS, Bailey AL. Sex and gender differences in pain and analgesia. Prog Brain Res. 2010;186:141–57. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53630-3.00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nakamura M, Yasuda K, Hasumi-Nakayama Y, Sugiura M, Tomita I, Mori R, Tanaka S, Furusawa K. Colocalization of serotonin and substance P in the postnatal rat trigeminal motor nucleus and its surroundings. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2006;24:61–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakatsuka T, Chen M, Takeda D, King C, Ling J, Xing H, Ataka T, Vierck C, Yezierski R, Gu JG. Substance P-driven feed-forward inhibitory activity in the mammalian spinal cord. Mol Pain. 2005;1:20. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naliboff BD, Derbyshire SW, Munakata J, Berman S, Mandelkern M, Chang L, Mayer EA. Cerebral activation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and control subjects during rectosigmoid stimulation. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:365–75. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200105000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naliboff BD, Kim SE, Bolus R, Bernstein CN, Mayer EA, Chang L. Gastrointestinal and psychological mediators of health-related quality of life in IBS and IBD: a structural equation modeling analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:451–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nyman MJ, Eskola O, Kajander J, Vahlberg T, Sanabria S, Burns D, Hargreaves R, Solin O, Hietala J. Gender and age affect NK1 receptors in the human brain – a positron emission tomography study with [18F]SPA-RQ. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;10:219–29. doi: 10.1017/S1461145706006572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oehme P, Hecht K, Faulhaber HD, Nieber K, Roske I, Rathsack R. Relationship of substance P to catecholamines, stress, and hypertension. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1987;10:S109–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parenti C, Arico G, Ronsisvalle G, Scoto GM. Supraspinal injection of substance P attenuates allodynia and hyperalgesia in a rat model of inflammatory pain. Peptides. 2012;34:412–8. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Phillips ML, Drevets WC, Rauch SL, Lane R. Neurobiology of emotion perception I: the neural basis of normal emotion perception. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:504–14. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pinto M, Lima D, Castro-Lopes J, Tavares I. Noxious-evoked c-fos expression in brainstem neurons immunoreactive for GABAB, mu-opioid and NK-1 receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1393–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Price DD, Craggs J, Verne GN, Perlstein WM, Robinson ME. Placebo analgesia is accompanied by large reductions in pain–related brain activity in irritable bowel syndrome patients. PAIN®. 2007;127:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rahman W, Suzuki R, Webber M, Hunt SP, Dickenson AH. Depletion of endogenous spinal 5-HT attenuates the behavioural hypersensitivity to mechanical and cooling stimuli induced by spinal nerve ligation. PAIN®. 2006;123:264–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roberts C, Inamdar A, Koch A, Kitchiner P, Dewit O, Merlo-Pich E, Fina P, McFerran DJ, Baguley DM. A randomized, controlled study comparing the effects of vestipitant or vestipitant and paroxetine combination in subjects with tinnitus. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32:721–7. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318218a086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roza C, Reeh PW. Substance P, calcitonin gene related peptide and PGE2 co-released from the mouse colon: a new model to study nociceptive and inflammatory responses in viscera, in vitro. PAIN®. 2001;93:213–9. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Russell IJ, Vaeroy H, Javors M, Nyberg F. Cerebrospinal fluid biogenic amine metabolites in fibromyalgia/fibrositis syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:550–6. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schicho R, Donnerer J, Liebmann I, Lippe IT. Nociceptive transmitter release in the dorsal spinal cord by capsaicin-sensitive fibers after noxious gastric stimulation. Brain Res. 2005;1039:108–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Seybold VS. The role of peptides in central sensitization. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;194:451–91. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-79090-7_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Singewald N, Chicchi GG, Thurner CC, Tsao KL, Spetea M, Schmidhammer H, Sreepathi HK, Ferraguti F, Singewald GM, Ebner K. Modulation of basal and stress-induced amygdaloid substance P release by the potent and selective NK1 receptor antagonist L-822429. J Neurochem. 2008;106:2476–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singh P, Agnihotri A, Pathak MK, Shirazi A, Tiwari RP, Sreenivas V, Sagar R, Makharia GK. Psychiatric, somatic and other functional gastrointestinal disorders in patients with irritable bowel syndrome at a tertiary care center. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;18:324–31. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2012.18.3.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Spielberger CD, Gorusch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sprague DR, Chin FT, Liow JS, Fujita M, Burns HD, Hargreaves R, Stubbs JB, Pike VW, Innis RB, Mozley PD. Human biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of the tachykinin NK1 antagonist radioligand [18F]SPA-RQ: comparison of thin-slice, bisected, and 2-dimensional planar image analysis. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:100–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Takayama H, Ota Z, Ogawa N. Effect of immobilization stress on neuropeptides and their receptors in rat central nervous system. Regul Pept. 1986;15:239–48. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(86)90065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tallaksen-Greene SJ, Elde R, Wessendorf MW. Regional distribution of serotonin and substance P co-existing in nerve fibers and terminals in the brainstem of the rat. Neuroscience. 1993;53:1127–42. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tillisch K, Labus J, Nam B, Bueller J, Smith S, Suyenobu B, Siffert J, McKelvy J, Naliboff B, Mayer E. Neurokinin-1-receptor antagonism decreases anxiety and emotional arousal circuit response to noxious visceral distension in women with irritable bowel syndrome: a pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:360–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04958.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Torsney C. Inflammatory pain unmasks heterosynaptic facilitation in lamina I neurokinin 1 receptor-expressing neurons in rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5158–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6241-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tracey I, Mantyh PW. The cerebral signature for pain perception and its modulation. Neuron. 2007;55:377–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vogt BA. Pain and emotion interactions in subregions of the cingulate gyrus. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:533–44. doi: 10.1038/nrn1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vogt BA, Derbyshire S, Jones AK. Pain processing in four regions of human cingulate cortex localized with co-registered PET and MR imaging. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:1461–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wackerly D, Mendenhall W, III, Schaeffer R. Mathematical statistics with applications. 5th. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wager TD, Rilling JK, Smith EE, Sokolik A, Casey KL, Davidson RJ, Kosslyn SM, Rose RM, Cohen JD. Placebo-induced changes in FMRI in the anticipation and experience of pain. Science. 2004;303:1162–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1093065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Winter MK, McCarson KE. G-protein activation by neurokinin-1 receptors is dynamically regulated during persistent nociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:214–21. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.089565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu Y, Carson RE. Noise reduction in the simplified reference tissue model for neuroreceptor functional imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:1440–52. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000033967.83623.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table and Figures S1-S3