Rebuilding an Immune-Mediated Central Nervous System Disease: Weighing the Pathogenicity of Antigen-Specific versus Bystander T Cells (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2017 Feb 21.

Abstract

Although both self- and pathogen-specific T cells can participate in tissue destruction, recent studies have proposed that after viral infection, bystander T cells of an irrelevant specificity can bypass peptide-MHC restriction and contribute to undesired immunopathological consequences. To evaluate the importance of this mechanism of immunopathogenesis, we determined the relative contributions of Ag-specific and bystander CD8+ T cells to the development of CNS disease. Using lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) as a stimulus for T cell recruitment into the CNS, we demonstrate that bystander CD8+ T cells with an activated surface phenotype can indeed be recruited into the CNS over a chronic time window. These cells become anatomically positioned in the CNS parenchyma, and a fraction aberrantly acquires the capacity to produce the effector cytokine, IFN-β. However, when directly compared with their virus-specific counterparts, the contribution of bystander T cells to CNS damage was insignificant in nature (even when specifically activated). Although bystander T cells alone failed to cause tissue injury, transferring as few as 1000 naive LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells into a restricted repertoire containing only bystander T cells was sufficient to induce immune-mediated pathology and reconstitute a fatal CNS disease. These studies underscore the importance of specific T cells in the development of immunopathology and subsequent disease. Because of highly restrictive constraints imposed by the host, it is more likely that specific, rather than nonspecific, bystander T cells are the active participants in T cell-mediated diseases that afflict humans.

The exquisite specificity of the adaptive immune system is exemplified by the ability of the host to display both foreign and self-derived peptides in a molecular scaffold, referred to as the MHC (1, 2). In most instances, the context within which these peptides are displayed permits T lymphocytes to make a critical distinction between self and nonself, thus averting undesired immunopathological consequences. Unfortunately, this distinction is occasionally associated with a lapse in judgment that results in the adaptive immune response becoming misdirected toward self. This aberrant T cell response, now defined by its specificity toward self-proteins, can be triggered by several established mechanisms, including bystander activation (3–6), epitope spreading (7, 8), and molecular mimicry (9–15). In each scenario the factors governing the maintenance of tolerance (16) are overridden, resulting in the expansion of an activated population of self-reactive T lymphocytes capable of directing (or participating in) immunopathogenesis.

The fact that self-reactive T cells when mistakenly activated can contribute to tissue breakdown and subsequent disease seems intuitive and fits appropriately within the self/nonself framework that has become so prominent in immunology. Along this continuum of T lymphocyte-induced immunopathology, it has been recognized repeatedly that an adaptive immune response directed against infectious agents can also play an irreducible role in human disease (17). The immense clonal expansion of T lymphocytes that often follows infection (18, 19) probably represents an effort by the host to completely overwhelm an invading pathogen, thus minimizing the amount of tissue pathology that develops. However, other factors, such as the anatomical positioning of a pathogen during clearance (20) or the ability of a pathogen to persist (21, 22), can shift the balance in favor of dire immunopathological consequences. Because a subset of T lymphocytes is armed with the capacity to lyse targets (23–25), immunopathology is an unfortunate side effect associated with the eradication of pathogens from the host. Therefore, it is imperative that several dampening mechanisms converge to thwart this ill-favored side effect. Specificity (1, 26) and tight regulation (27, 28) lie at the heart of such dampening mechanisms.

An issue central to the ability of both self- and pathogen-specific T lymphocytes to cause immunopathology is that of specificity. Both populations recognize cognate peptides presented in MHC complexes on the surface of cells residing in various tissue compartments. This evolutionary checkpoint limits the degree of tissue destruction by ensuring that T lymphocytes use effector mechanisms only after target cell recognition is achieved. However, recent studies focusing on viral infection of the CNS (29, 30) and the eye (4, 31, 32) have revealed that T lymphocytes under certain circumstances are able to bypass recognition of peptide-MHC complexes and mediate tissue destruction without using TCR engagement. The T lymphocytes studied in the aforementioned model systems lack apparent specificity to self or foreign Ags and thus are appropriately referred to as bystander T cells. The precise mechanism by which these bystander T cells cause immunopathology is not known; however, their participation in disease appears to defy important evolutionary constraints imposed by the host.

In the present study we used a well-defined model of meningitis induced by lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV)3 (20, 33) in an attempt to further explore as well as generalize the importance of bystander T cells in the development of CNS pathology. A strong base of literature indicates that the lethal meningitis initiated after an intracerebral challenge with LCMV bears the hallmarks of specificity. CD8+ T cells play an indispensable role in the disease pathogenesis, which becomes lethal at 6–7 days postinfection (34). Moreover, it has been touted that the effector molecule perforin, which is secreted by CD8+ T cells, is also important in the acute disease process (23). However, at the end stage of the disease when neurologic deficits become apparent, we were unable to account for the specificity of most CD8+ T cells residing in the CNS. This led us to theorize that bystander CD8+ T cells of an irrelevant specificity might indeed contribute to the development of pathology if retained in the CNS over an extended time period. Furthermore, the ability of a seemingly endless supply of pathogens to replicate within the CNS (35) may serve as a stimulus to recruit and activate bystander T cells. Consequently, we set out to address several important issues regarding bystander T cell activation, recruitment, and potential effector mechanisms within the CNS after viral infection.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6, C57BL/6 OT-I TCR-transgenic (tg) (36, 37), C57BL/6 gp33 TCR-tg (38), and C57BL/6-TgN(ACTbEGFP)10sb (39) mice were bred and maintained in the closed breeding facility at The Scripps Research Institute. All strains are on a pure C57BL/6 background. The gp33 TCR-tg mice were crossed with GFP mice to generate a GFP-labeled population of Dbgp33–41-specific T cells (40). The handling of all mice conformed to the requirements of the National Institutes of Health and The Scripps Research Institute animal research committee.

Virus

The parental Armstrong 53b (Arm) of LCMV, which is a triple-plaquepurified clone from Armstrong CA 1371 (41), was used for all experiments. Mice at 8–10 wk of age were injected either intracerebrally with 103 PFU or i.p. with 105 PFU of LCMV Arm.

Intracellular cytokine analyses

Splenocytes or brain-infiltrating lymphocytes were cultured (5 h, 37°C, 5% CO2) in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Eggenstein, Germany) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% L-glutamine, 1% HEPES, 1% nonessential amino acids, 1% sodium pyruvate, 1 _μ_g/ml brefeldin A, 100 U/ml IL-2, and 1 (or 2) _μ_g/ml of the indicated peptides. The following peptide sequences were purchased from Peptido-Genic Research (Livermore, CA): gp33–41 (KAVYNFATC), gp276–286 (SGVENPGGYCL), gp118–125 (ISHNFCNL), gp92–101 (CSANNAHHYI), NP396–404 (FQPQNGQFI), NP205–212 (YTVKYPNL), gp61–80 (GLNgp-DIYKGVYQFKSVEFD), NP309–328 (SGEGWPYIACRTSVVGRAWE), and OVA257–264 (SIINFEKL). After the 5-h in vitro stimulation, surface as well as intracellular cytokine stains were performed to evaluate the percentage of CD8+ or CD4+ T cells producing IFN-γ. Cells from uninfected mice or cultures stimulated with a mismatched peptide were used as a negative control.

Immunizations

OT-I mice were immunized 1 day before infection by i.p. injecting 100 _μ_g of cognate peptide (OVA257–264) emulsified in CFA (Difco, Detroit, MI). Control mice received CFA containing HBSS buffer only.

Flow cytometry

The following Abs purchased from BD Pharmingen (La Jolla, CA) were used to stain splenocytes and brain-infiltrating lymphocytes: anti-CD8-FITC, anti-CD8-PE, anti-CD8-PerCP, anti-CD8-allophycocyanin, anti-CD4-PE, anti-CD44-allophycocyanin, anti-V_β_5.1-PE, anti-Va2-FITC, and anti-IFN-_γ_-allophycocyanin. Cells were acquired using the FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) and were analyzed with the FlowJo (Treestar) software.

Mononuclear cell isolations and tissue processing

To obtain cell suspensions for flow cytometric analyses/peptide stimulation cultures, spleens and CNS were harvested from mice after an intracardiac perfusion with a 0.9% saline solution to remove the contaminating blood lymphocytes. Splenocytes and brain-infiltrating leukocytes were collected after mechanical disruption of the respective tissues through a 70-_μ_m filter. Splenocytes were treated with RBC lysis buffer (0.14 M NH4Cl and 0.017 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.2), washed, and then analyzed. To extract brain-infiltrating leukocytes, homogenates were resuspended in 90% Percoll (4 ml), which was overlaid with 60% Percoll (3 ml), 40% Percoll (4 ml), and finally 1× HBSS (3 ml). The Percoll gradients were then centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 15 min, after which the band corresponding to mononuclear cells was carefully extracted, washed, and ultimately analyzed. The number of mononuclear cells was determined from each organ preparation and used to calculate the absolute number of CD8+ T cells. PBMC were obtained by centrifugation after incubating (1 h on ice) a capillary of blood (~210 _μ_l) with 10 ml of RBC lysis buffer. To visualize GFP+Dbgp33–41-specific T cells in situ, mice received an intracardiac perfusion of 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were then removed, incubated for 24 h in 4% paraformaldehyde and for an additional 24 h in 30% sucrose. After freezing tissues in OCT (Tissue-Tek), 6-_μ_m frozen sections were cut and stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1 mg/ml, 5 min) to visualize nuclei. For all other immunohistochemical analyses, fresh, unfixed brains were submerged in OCT and frozen using dry ice.

Adoptive transfer of GFP+Dbgp33–41 T cells

CD8+ T cells were purified from gp33 TCR-tg × GFP mouse splenocytes by negative selection (StemCell Technologies, Cambridge, MA). The enrichment procedure resulted in a purity of >98%. Concentrations ranging from 101–105 GFP+Dbgp33–41 T cells were transferred i.v. into naive C57BL/6 or OT-I TCR-tg recipients. Two days after the adoptive transfer, mice were infected intracerebrally with 103 PFU or i.p. with 105 PFU of LCMV Arm. To enumerate the absolute number of GFP+Dbgp33–41 CD8+ T cells present in OT-I mice reconstituted with 103 naive precursors, splenocytes and CNS (brain/spinal cord)-infiltrating leukocytes were harvested at precisely the time point when overt neurologic dysfunction became apparent. Each cell population was stained with anti-CD8-allophycocyanin and analyzed by flow cytometry to establish the percentage of the population that was both CD8+ and GFP+. This percentage was then multiplied by the number of cells harvested from each organ to obtain values approximating the absolute number of GFP+Dbgp33–41 CD8+ T cells required in the spleen and CNS to reconstitute disease in OT-I mice (see Fig. 9_D_).

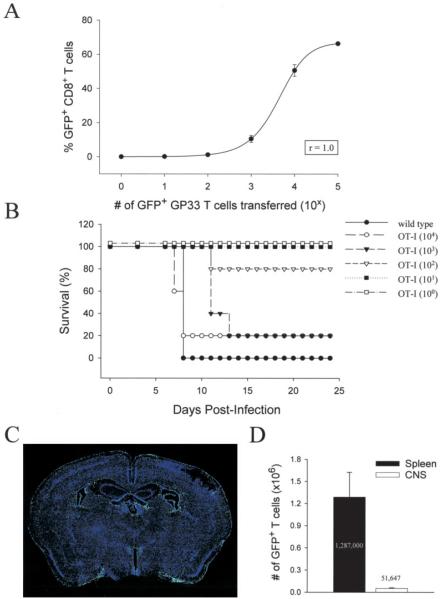

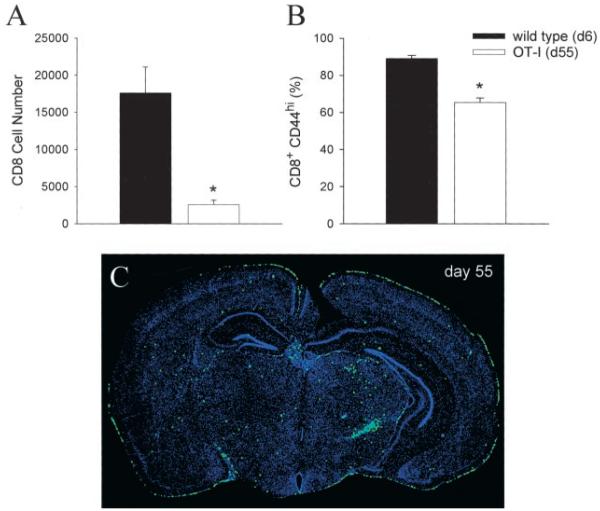

FIGURE 9.

Reconstitution of acute disease in OT-I mice. A, The perfect sigmoidal relationship (r = 1.0) between the number of naive GFP+Dbgp33–41-specific CD8+ T cells injected and the magnitude of the virus-specific immune response on day 8 after an i.p. infection of wild-type mice with 105 PFU of LCMV Arm. Two days before infection, mice received log-serial dilutions of naive GFP+Dbgp33–41-specific CD8+ T cells ranging from 105–100. B, Survival curve of OT-I mice (n = 5/group) reconstituted with log-serial dilutions of naive GFP+Dbgp33–41-specific CD8+ T cells ranging from 104–100. Wild-type mice (n = 5) served as a positive control for this experiment. Two days after the adoptive transfer, mice received intracerebral infection with 103 PFU of LCMV Arm. C, Representative example (n = 3) of a coronal brain reconstruction from a symptomatic OT-I mouse (day 8) receiving the minimum number of naive GFP+Dbgp33–41-specific CD8+ T cells (i.e., 103) required to reconstituted disease. Green dots represent individual GFP+Dbgp33–41-specific CD8+ T cells in the brain. Sections were costained with a nuclear dye (blue). D, Quantification of the absolute number of GFP+Dbgp33–41-specific CD8+ T cells present in the spleen and CNS of symptomatic OT-I mice (n = 4) on day 8 postinfection, receiving the minimum number of cells required to reconstitute disease. Data are represented as the mean ± SD. The average for each tissue is shown on the graph.

Immunohistochemistry

To visualize LCMV, neurons, astrocytes, and CD8+ T cells, 6-_μ_m frozen sections were cut, fixed with 2% formaldehyde, blocked with 10% FBS (1 h, at room temperature), and stained (1 h, at room temperature) with guinea pig anti-LCMV (1/1000), mouse anti-neuronal nuclei (anti-NeuN; 1.25 _μ_g/ml; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA), rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (anti-GFAP; 1/800; DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA), and rat anti-CD8 (1.0 _μ_g/ml; BD Pharmingen, La Jolla CA) Abs, respectively. To block endogenous mouse Abs, sections stained with mouse anti-NeuN were preincubated (1 h, at room temperature) with a Fab′ anti-mouse H and L chain Ab (35 _μ_g/ml; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). After the primary Ab incubation, sections stained with Abs directed against NeuN, GFAP, or CD8 were washed, stained with a biotinylated secondary Ab (1/400; 1 h, at room temperature; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), washed, and then stained with streptavidin-rhodamine red-X (1/400; 1 h, at room temperature; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). The polyclonal anti-LCMV Ab was detected using an anti-guinea pig secondary conjugated to FITC (1/800; 1 h, at room temperature). All sections were costained with DAPI (1 _μ_g/ml; 5 min, at room temperature) to visualize nuclei. We calculated the percentage of LCMV-infected cells accounted for by neurons (NeuN) or astrocytes (GFAP) using frozen brain sections from persistently infected OT-I mice costained with the above-mentioned Abs (see Fig. 3). Eighteen random ×40 fields were captured using a confocal microscope (see Microscopy section) and analyzed to determine the number LCMV-infected cells in each field that overlapped with NeuN or GFAP. The resultant fractional value was ultimately represented as a percentage.

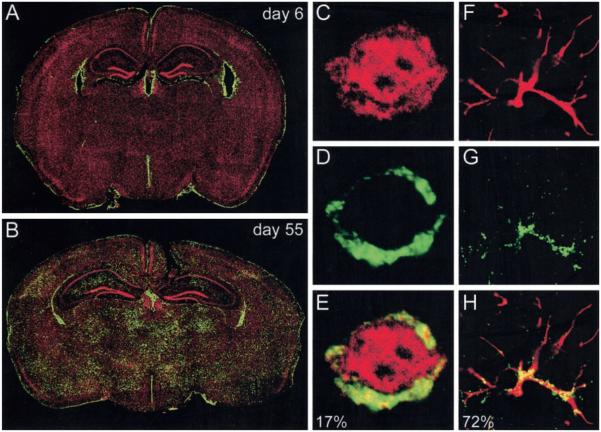

FIGURE 3.

Evaluation of viral tropism in OT-I mice. Six-micron coronal brain sections from OT-I mice on day 6 (n = 3; A) and day 55 (n = 3; B) postinfection were stained with a polyclonal anti-LCMV Ab (green) and a nuclear dye (red). Brain reconstructions were performed to illustrate the anatomical distribution of LCMV. On day 6 after an intracerebral inoculation, LCMV localizes to the meninges, ependyma, and choriod plexus. At later time points, the virus also establishes persistence in the brain parenchyma. C–H, High resolution analyses of LCMV-infected cells (green; D and G) that colocalize with neuronal (red; C) or astrocyte (red; GFAP; F) staining on day 55 postinfection. Overlapping fluorescence illustrated in the merged panels (E and H) appears in yellow. The percentages shown on the merged images indicate the frequency of LCMV-infected cells that can be accounted for by neuronal (17%) or astrocyte staining (73%).

Analysis of apoptosis

Analysis of cell death was performed on 6-_μ_m frozen brain sections using the ApopTag Red apoptosis detection kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Chemicon International). Sections were costained with DAPI (1 _μ_g/ml; 5 min) to visualize nuclei. The number of apoptotic cells per square centimeter of brain tissue was calculated from brain reconstructions (see Fig. 7 and Microscopy section) using a program written for the KS300 image analysis software. After segmentation of the regions representing apoptotic cells from each image, the average area of a single apoptotic cell as well as the total area occupied by apoptotic cells were calculated. The absolute number of apoptotic cells was then determined by dividing the total area occupied by apoptotic cells by the average area of a single apoptotic cell. The data were ultimately represented as the absolute number of apoptotic cells per square centimeter of brain tissue sampled.

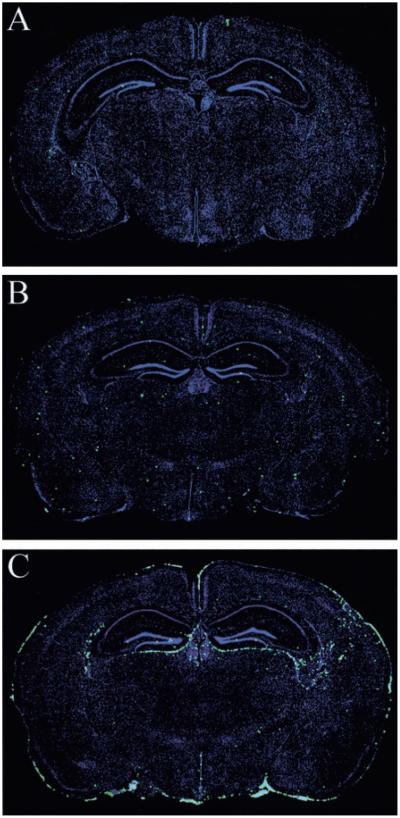

FIGURE 7.

Apoptosis in the brains of infected wild-type and OT-I mice. An ApopTag detection kit (see Materials and Methods) was used to visualize apoptotic cells (green) on 6-_μ_m frozen brain sections from uninfected wild-type (n = 3; A), day 31 after infection (d31) OT-I (n = 3; B), and d6 wild-type (n = 5; C) mice. Sections were counterstained with a nuclear dye (blue). The diameter of each green dot, which represents an individual apoptotic cell, was digitally enhanced by 1 pixel to facilitate visualization of these cells on the reconstruction. Note the marked increase in the number of apoptotic cells in the brain of symptomatic B6 mice on d6 after an intracerebral infection.

Microscopy

Two-color reconstructions to visualize the distribution of LCMV, apoptotic cells, or GFP+Dbgp33–41-specific T cells on coronal brain sections were obtained using an Axiovert S100 immunofluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) fitted with an automated xy stage, an Axiocam color digital camera, and a ×5 objective. Registered images were captured for each field on the coronal brain section, and reconstructions were performed using the MosaiX function in the KS300 image analysis software. Higher resolution images were captured with an MRC1024 confocal microscope (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) fitted with a krypton/argon mixed gas laser (excitation at 488, 568, and 647 nm) and a ×40 oil objective. All two-dimensional confocal images illustrate a single z section captured at a position approximating the midline of the cell.

Statistical analyses

Data handling, analysis, and graphic representation were performed using Microsoft Excel and SigmaPlot. Statistical differences were determined by Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA ( p < 0.05) using SigmaStat.

Results

Bystander T cells fail to drive an acute meningitis

Because of the rapidity with which disease presents in mice infected intracerebrally with LCMV Arm (i.e., 6–7 days), it is reasonable to hypothesize that virus-specific T cells play a pivotal role in pathogenesis. Supporting this hypothesis are several irrefutable studies demonstrating that LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells are required for the lethality of the disease process (34, 42). However, at the precise time point when mice succumb to the meningitis, no more than 20.4 ± 2.5% of the CNS-infiltrating CD8+ T cells could be tallied as those capable of responding to one of seven different MHC class I-restricted peptides thought to represent the entire LCMV-specific T cell response (43–44). These data were obtained by analyzing six symptomatic B6 mice on day 6 postinfection. Splenocytes and CNS-infiltrating mononuclear cells were incubated with a peptide pool containing the seven known class I-restricted LCMV epitopes and then assayed for IFN-γ production (see Materials and Methods). At this time point postinfection, a similar frequency of LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells was observed in the spleen (19.5 ± 5.0%).

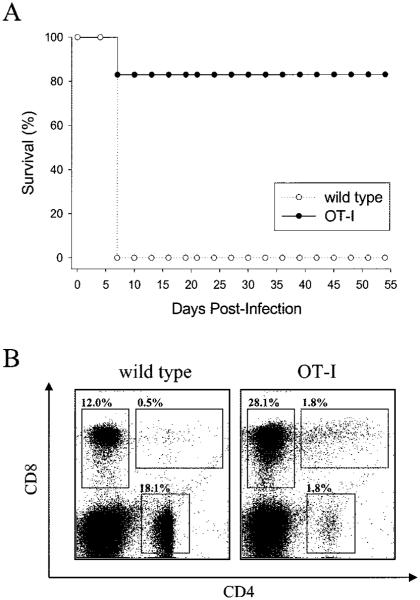

Considering that we could not account for ~80% of the CD8+ T cells residing in the CNS at the peak of disease, we surmised that T cells of an irrelevant specificity (i.e., bystander T cells) were recruited into the CNS and may indeed participate in disease pathogenesis. To test this supposition, we intracerebrally inoculated a TCR-tg mouse strain (hereafter referred to as an OT-I mice) in which >90% of the CD8+ T cells recognized aa 257–264 of OVA presented in the H-2Db molecule (36, 37). Because there is no overlap between this portion of OVA and any LCMV protein, KbOVA257–264-specific CD8+ T cells are truly bystander T cells of an irrelevant specificity. When OT-I mice were infected intracerebrally with LCMV Arm, the majority of the mice failed to succumb to the infection (Fig. 1_A_). In fact, for the entire observation period (>150 days), OT-I mice remained completely asymptomatic. In contrast, wild-type C57BL/6 mice showed signs of neurologic dysfunction (i.e., ruffled fur, hunched back, and tremors) and, as expected, succumbed to the meningitis precisely on day 6 postinfection. These data indicate that the restricted, largely monospecific T cell repertoire present in OT-I mice was incapable of recapitulating the overt disease observed in wild-type mice.

FIGURE 1.

Analysis of survival and the peripheral T cell compartment in OT-I mice. Wild-type (n = 5) and OT-I mice (n = 5) were infected intracerebrally with 103 PFU of LCMV Arm and monitored for survival. The plot in A illustrates an observation period of 55 days, which is representative of the entire 150-day window of the study. The OT-I curve shows that one of the five mice succumbed to the intracerebral challenge. This probably resulted from the intracerebral injection procedure, because no additional OT-I mice succumbed to infection in subsequent experiments (see Fig. 9_B_ for examples). PBMC harvested from uninfected wild-type and OT-I mice were analyzed flow cytometrically to establish the frequency of CD8+, CD4+, and CD8+CD4+ cells in the T cell compartment (B). Gray boxes are used to highlight each of the aforementioned T cell populations. Note the significant skewing of the repertoire in OT-I mice: 28% CD8+ and only 1.8% CD4+.

OT-I mice do not mount an LCMV-specific T cell response

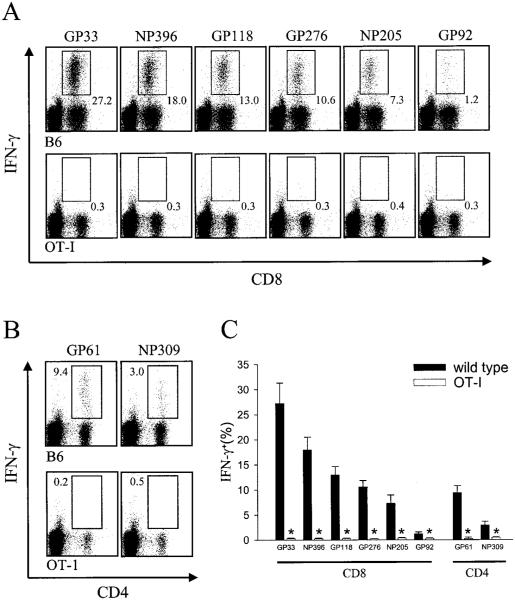

Having established that signs reminiscent of LCMV-induced meningitis were not observed in OT-I mice, we next set out to define the parameters underlying this benign disease course and gather information regarding the migration, activation status, and cytokine production of bystander T cells. Because the LCMV-specific T cell response is thought to drive the disease process through the engagement of virus-infected targets residing in the meninges, ependyma, and choriod plexus, we initially evaluated whether OT-I mice were indeed capable of mounting an LCMV-specific T cell response despite their restricted T cell repertoire. To maximize the probability of detecting such a response, we infected OT-I and wild-type control mice i.p. with 105 PFU of LCMV Arm and analyzed the entire known MHC class I- and class II-restricted immune response (Fig. 2). Splenocytes were harvested on day 8 postinfection (the established peak of the virus-specific immune response (18)), stimulated with the indicated LCMV peptides, and evaluated for the synthesis of IFN-γ. As anticipated, OT-I mice, when compared with wild-type controls, failed to mount a CD8+ T cell response to any of the known LCMV peptides ( p < 0.05; Fig. 2, A and C). However (and perhaps more surprisingly), a population of LCMV-specific CD4+ T cells also failed to expand in OT-I mice ( p < 0.05; Fig. 2, B and C). This can probably be explained by the skewing in the CD4+ T cell compartment that occurs in TCR-tg mice (37). Because of alterations in thymic selection, a substantially reduced number of CD4+ T cells were observed in the peripheral tissues of naive OT-I mice (Fig. 1_B_). In concert, these data suggest that the absence of an acute LCMV-specific T cell response explains the failure of OT-I mice to present with the rapid and overt neurologic complications observed in wild-type mice. However, the reason behind the lack of neurologic complications over the entire observation period as well as the status of the bystander T cells remained open-ended questions.

FIGURE 2.

Quantification of the LCMV-specific T cell response in wild-type vs OT-I mice. Splenocytes from wild-type (n = 4) and OT-I (n = 4) mice infected i.p. with 105 PFU of LCMV Arm were analyzed on day 8 postinfection for CD8+ (A) or CD4+ (B) T cell responses to eight known class I- and class II-restricted peptides that map to the NP and glycoprotein (GP) of LCMV Arm (see Materials and Methods). The peptides are shown in order of immunodominance. Splenocytes were incubated in the presence of the indicated peptides for5h in vitro and then were analyzed for the production of IFN-γ. A summation of the results is shown in C. Data are represented as the mean ± SD. Statistical differences denoted by asterisks were determined using Student’s t test (p < 0.05).

Viral tropism shifts in the brains of OT-I mice

Because the lethal disease process observed after infection of wild-type mice depends not only on the expansion of LCMV-specific T cells, but also on the anatomical positioning of the virus within the CNS, we next addressed whether LCMV replicated in the meninges, ependyma, and choriod plexus of infected OT-I mice. At the time point when wild-type mice normally succumb to the infection (i.e., day 6 postinfection), the tropism of LCMV was indistinguishable from that observed in wild-type mice (Fig. 3_A_) (see Ref. 40 for example of viral tropism in wild-type mice), indicating that a failure to develop neurologic complications could not be explained by an aberrant anatomical positioning of the LCMV. Moreover, the lack of neurologic complications over time could also not be explained by the inability of LCMV to establish persistence in the CNS. Interestingly, when the brains of OT-I mice were examined on day 55 postinfection, it was found that LCMV persisted in the meninges and ependyma as well as the brain parenchyma (Fig. 3_B_). Within the brain parenchyma, LCMV preferred to persist in astrocytes and neurons, because 72% (or 354 of 492) of all LCMV-infected cells were found to colocalize with GFAP staining (Fig. 3, F–H), and an additional 17% (or 71 of 410) colocalized with NeuN staining (Fig. 3, C–E). The presence of LCMV in astrocytes is supported by recent studies demonstrating that astrocytes are among the first cells that become infected in the developing rat brain (46).

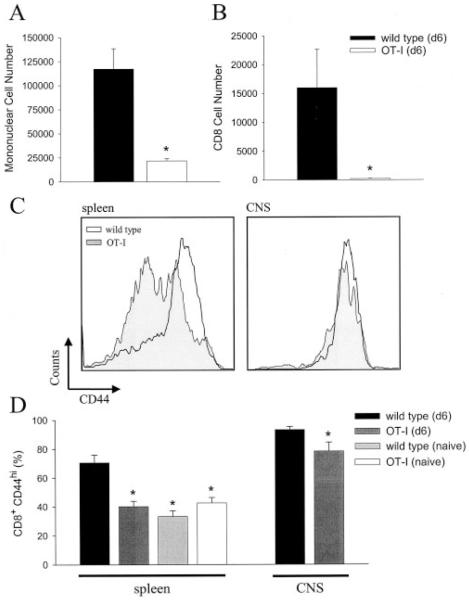

Bystander T cells traffic to the CNS, but with limited efficiency

Knowing that LCMV could indeed replicate as well as persist in the brains of OT-I mice, we focused our next line of experimentation on whether this could serve as a stimulus to recruit a monospecific population of bystander T cells. Because OT-I mice did not develop overt disease over time, it remained a distinct possibility that bystander T cells were simply not recruited into the CNS. To address this possibility, we isolated mononuclear cells from the brains of wild-type and OT-I mice on day 6 after an intracerebral infection with LCMV. Quantification of the absolute number of mononuclear (Fig. 4_A_) as well as CD8+ (Fig. 4_B_) T cells in the brains at this time point revealed that inflammatory cells could traffic to the CNS of OT-I mice, but to a markedly limited degree ( p < 0.05). Of the few CD8+ T cells residing in the CNS on day 6, the majority were deemed KbOVA257–264 specific (data not shown) after analysis of V_α_2 and V_β_5.1 expression (the TCR present on transgenic cells). Therefore, despite extensive LCMV replication in the CNS on day 6 postinfection (Fig. 3_A_), there was an inherent failure to efficiently recruit bystander KbOVA257–264-specific CD8+ T cells.

FIGURE 4.

Quantitative analysis of bystander T cell trafficking to the brain. The total number of mononuclear cells (A) and CD8+ T cells (B) residing in the brain was determined for wild-type (n = 5) and OT-I (n = 4) mice on day 6 postinfection (d6). Statistical differences denoted by asterisks were determined using Student’s t test (p < 0.05). Flow cytometric analyses were used to evaluate the expression of CD44 on CD8+ T cells obtained from the spleen or brain of mice at the indicated time point (C and D). A representative histogram gated on CD8+ T cells is shown for both tissue compartments (C). A summation of the results that illustrates the percentage of CD8+ T cells deemed CD44high is shown in D. For splenic CD8+ T cells, CD44 expression was compared statistically by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05) using the values obtained from uninfected wild-type (n = 4), uninfected OT-I (n = 4), day 6 wild-type (n = 5), and day 6 OT-I (n = 4) mice. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant reduction compared with day 6 wild-type mice. Uninfected wild-type and day 6 OT-I mice were not statistically different from one another. Because no CD8+ T cells were extracted from the brains of uninfected mice, analysis of CD44high expression on brain-infiltrating CD8+ T cells was restricted to infected wild-type and OT-I mice. Compared with wild-type mice, a slight reduction in the percentage of CD8+CD44high T cells was observed in OT-I mice; however, this percentage was significantly higher than that in the splenic compartment (p < 0.05).

Throughout the CNS literature, the dogma states that only activated T cells are permitted access to the CNS (47, 48). However, some have called this view into question, indicating that naive T cells also share this property, which is thought to be unique to activated T cells (49, 50). Based on the prevailing dogma, we surmised that the reduced ability of bystander KbOVA257–264-specific CD8+ T cells to migrate into the CNS could be explained by their failure to become activated after LCMV infection. Thus, we quantitatively evaluated CD44 expression (an established activation marker) in the CD8+ T cell compartment of wild-type and OT-I mice on day 6 after intracerebral infection. As expected, the expression of CD44 was markedly increased on CD8+ T cells obtained from the spleen and CNS of wild-type mice (Fig. 4, C and D). In fact, >93% of all CD8+ T cells residing in the CNS expressed CD44, confirming that T cells with an activated surface phenotype have preferential access to this tissue. In contrast, splenic CD8+ T cells (>90% of which are KbOVA257–264 specific) from OT-I mice showed an activation profile identical with that observed in naive mice (Fig. 4, C and D), and those that were recruited to the CNS were largely CD44high. These data suggest that the limited trafficking of KbOVA257–264-specific CD8+ T cells to the CNS in OT-I mice probably results from a failure of the bulk population to become activated.

Chronic viral persistence enhances bystander T cell recruitment into the CNS as well as cytokine production

KbOVA257–264-specific CD8+ T cells fail to efficiently migrate to the CNS 6 days after intracerebral infection with LCMV. Based on these findings, it could be argued that this is an insufficient time period to recruit a nonactivated population of bystander T cells into the CNS. Furthermore, the chronicity of a disease process as well as the continued stimulation of APCs from viral persistence may, in fact, drive aberrant T cell activation, thus promoting CNS recruitment and tissue pathology. To address these issues, we quantified the absolute number of CD8+ T cells in the brain on day 55 postinfection. Compared with wild-type mice on day 6, the absolute number of CD8+ T cells (>90% of which are KbOVA257–264specific) extracted from the brain remained significantly reduced ( p < 0.05; Fig. 5_A_), and as before, the majority of these cells were CD44high (Fig. 5_B_). Nevertheless, the absolute number of bystander T cells in the CNS of OT-I mice at this time point was indeed higher than that observed on day 6 (see Fig. 4_B_). These data indicate that over time an elevated number of bystander T cells are retained in the CNS, although the efficiency of recruitment remains diminished compared with that in wild-type mice infected with LCMV.

FIGURE 5.

Enumeration and anatomical localization of bystander T cells in persistently infected OT-I mice. The total number of brain-infiltrating CD8+ T cells (A) as well the percentage of CD8+CD44high T cells (B) were compared between acutely infected (day 6 (d6)) wild-type mice (n = 5) and persistently infected (day 55 (d55)) OT-I mice (n = 5). Statistical differences denoted by asterisks were determined using Student’s t test (p < 0.05). The anatomical distribution of CD8+ T cells in persistently infected OT-I mice (_n_ = 3) was evaluated by performing reconstructions of 6-_μ_m coronal brain sections stained with an anti-CD8 Ab (green) and a nuclear dye (blue). Anti-CD8 (instead of a V_β_5.1) Ab was used because flow cytometric analyses revealed that >90% of brain-infiltrating CD8+ T cells at this time point coexpressed V_α_2 and V_β_5.1, confirming that they were KbOVA257–264 specific. A representative coronal brain reconstruction is shown in C. The diameter of each green dot, which represents an individual CD8+ T cell, was digitally enhanced by one pixel to facilitate visualization of these cells on the reconstruction.

Because mononuclear cell preparations from the CNS require mechanical disruption of the tissue, the aforementioned analyses of absolute cell numbers provide no information regarding the anatomical positioning of bystander T cells within the CNS. Consequently, we next addressed whether bystander T cells in the brains of OT-I mice were anatomically poised to drive tissue pathology. Coronal brain reconstructions were performed on day 55 postinfection to examine the localization of CD8+ T cells within the brain (Fig. 5_C_). The results revealed that the bystander T cells were widely distributed throughout the brain parenchyma and meningeal surface, which are both sites of viral persistence in OT-I mice (see Fig. 3_B_). Thus, bystander T cells are not only retained in the CNS over time, but are anatomically positioned to facilitate tissue pathogenesis if triggered to release effector molecules.

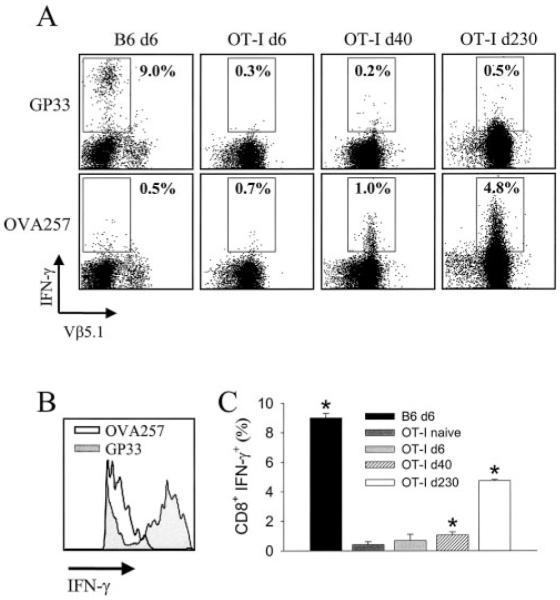

The ability of a bystander T cell population to drive tissue pathology is predicated on the supposition that the population in question has been nonspecifically (or aberrantly stimulated) to engage effector mechanisms. Therefore, we addressed whether KbOVA257–264-specific CD8+ T cells could produce IFN-γ in response to their cognate Ag ex vivo despite having never been challenged with this Ag in vivo. To ensure that an appropriate number of cells could be analyzed, splenocytes (instead of brain-infiltrating mononuclear cells) were harvested from acutely (day 6) and persistently (day 40) infected OT-I mice, stimulated with peptide for 5 h in vitro, then analyzed for IFN-γ production. On day 6 postinfection, the percentage of KbOVA257–264-specific CD8+ T cells that produced IFN-γ in response to OVA257–264 was not statistically increased over that observed with an irrelevant peptide (i.e., gp33–41; Fig. 6, A and C). When the same population was analyzed in persistently infected OT-I mice on day 40, 1.0% of all bystander T cells responded to their cognate Ag (a statistically significant increase over the irrelevant peptide control, p < 0.05), which was not observed in age-matched uninfected OT-I mice (Fig. 6_C_). Interestingly, this frequency increased to 4.8% on day 230 postinfection (Fig. 6, A and C). However, the response was both qualitatively and quantitatively diminished when compared with that of a dominant LCMV-specific T cell population (i.e., Dbgp33–41-specific cells; Fig. 6, A and B). The geometric mean fluorescent intensity of IFN-_γ_-producing, Dbgp33–41-specific T cells in wild-type mice was 810.2 ± 29.3 (mean ± SD). In contrast, the geometric mean fluorescent intensity for KbOVA257–264 specific T cells from persistently infected mice was only 80.7 ± 10.2 on day 40 and 129.6 ± 22.3 on day 230, which resembled the low producing, Dbgp33–41-specific cells observed in wild-type mice (Fig. 6_B_). Collectively, these data demonstrate that bystander T cells are stimulated (perhaps aberrantly) to produce the effector cytokine, IFN-γ, in persistently infected OT-I mice, although the quality of this response on a per cell basis is markedly reduced compared with that in LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells.

FIGURE 6.

Analysis of IFN-γ production by bystander T cells. Splenocytes from intracerebrally inoculated wild-type (day 6 (d6); n = 3), OT-I (d6; n = 4), OT-I (d40; n = 3), and OT-I (d230; n = 3) mice were analyzed for the ability to produce IFN-γ after a 5-h in vitro stimulation with either gp33–41 or OVA257–264 peptide. Representative flow cytometric plots gated on CD8+ T cells are shown in A. The percentage of CD8+ T cells that produce IFN-γ in response to the indicated peptide is shown on each plot (■). V_β_5.1 expression was evaluated to ensure that the CD8+ T cells analyzed from OT-I mice were, in fact, KbOVA257–264 specific. B, Representative histogram (gated on CD8+ T cells) comparing the intensity of IFN-γ production between Dbgp33–41-specific (d6) and KbOVA257–264-specific (d40) T cells. C, Summary of the percentage of IFN-γ expressing CD8+ T cells to cognate peptide shown in A. This panel also includes uninfected OT-I (n = 3) mice as a control. Asterisks denote a statistical difference, as determined by Student’s t test (p < 0.05), between cells stimulated with cognate vs irrelevant peptide. For example, a statistically significant increase in IFN-γ production was observed for OT-I mice on d40 when OVA257–264 peptide (cognate) was compared with gp33–41 (irrelevant).

Bystander T cells induce minimal apoptosis in the brains of persistently infected mice

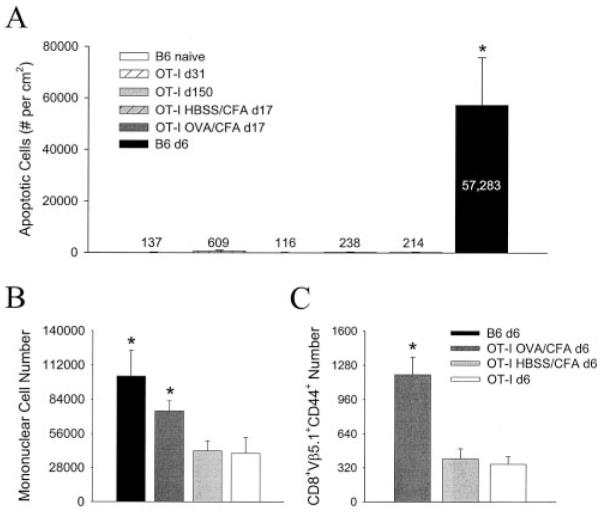

Having established that bystander T cells are anatomically positioned in the CNS parenchyma and harbor the potential to produce cytokines (albeit to a reduced degree) in persistently infected OT-I mice, we theorized that the retention of this population of cells within the CNS over time could potentially have a detrimental impact. Although overt disease was not noted in persistently infected OT-I mice, we opted to evaluate a more sensitive readout for tissue pathology (i.e., apoptosis). The number of apoptotic cells per square centimeter of tissue was analyzed quantitatively on coronal brain reconstructions from naive, persistently infected OT-I (days 31 and 150), and acutely infected (day 6) wild-type mice (Figs. 7 and 8_A_). The number of apoptotic cells per square centimeter was similar between uninfected (137 ± 55) and persistently infected OT-I mice on day 31 (609 ± 383) and day 150 (116 ± 48) postinfection, although a slight, but not statistically significant, difference was noted on day 31 ( p = 0.329). In stark contrast, the number of apoptotic cells in the brains of wild-type mice on day 6 (57,283 ± 18,541) was substantially elevated ( p < 0.05), which accurately reflects both the severity and the outcome of the pathologic process (i.e., death). Importantly, quantitative analysis revealed that 78.0 ± 4.7% (or 384 of 490) of the apoptotic cells colabeled with LCMV Ab staining. Because LCMV is a noncytopathic virus, these results signify that the majority of the apoptosis results from immune targeting of virus-infected cells (presumably by CD8+ T cells). Only a minor fraction (<22%) of the cellular death can be accounted for by infiltrating inflammatory cells. In concert, these results demonstrate that bystander T cells induce minimal CNS pathology despite their chronic retention, activation status, and potential to produce an effector cytokine.

FIGURE 8.

Quantitative analysis of apoptosis and bystander T cell recruitment in the brains of infected wild-type and OT-I mice. A, Number of apoptotic cells per square centimeter quantified on coronal brain reconstructions (see Fig. 7 for examples) using an image analysis program (see Materials and Methods). The data are represented as the mean ± SD for the following experimental groups: uninfected wild-type (n = 3), day 31 of infection (d31) OT-I (n = 3), d150 OT-I (n = 3), d17 HBSS/CFA OT-I (n = 4), d17 OVA/CFA OT-I (n = 3), and d6 wild-type (n = 5). Numbers on the graph denote the mean for each group. Similar results were obtained when OT-I mice were analyzed on d55. B and C, Absolute number of mononuclear (B) and activated (i.e., CD44+) KbOVA257–264-specific T cells (C) in CNS of the indicated groups on d6 postinfection. V_β_5.1 expression was evaluated in C to ensure that the CD8+ T cells analyzed from the CNS of OT-I mice were, in fact, KbOVA257–264 specific. Data are represented as the mean ± SD. Statistical differences between all groups (denoted by asterisks) were determined by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05).

Because the OT-I mice used in the previous studies were not primed with cognate Ag before infection with LCMV, the potential for CNS pathology relied solely on the recruitment of an existing population of bystander T cells that aberrantly acquired the capacity to produce cytokines and effector molecules. Consequently, it could be argued that the failure to observe CNS pathology in OT-I mice results from an inability to recruit a minimum number of activated bystanders. To address this fundamental concern, OT-I mice were immunized with cognate peptide (OVA257–264) emulsified in CFA and analyzed on day 17 after an intracerebral challenge with LCMV (mirroring previous studies that achieved bystander CNS damage) (29, 30). Despite the enhanced recruitment ( p < 0.05) of mononuclear cells (Fig. 8_B_) as well as bystander CD8+ T cells (Fig. 8_C_) to the CNS after immunization with OVA peptide, the level of apoptosis observed in brains of OVA/CFA mice (214 ± 99) was statistically similar ( p < 0.05) to that observed in HBSS/CFA controls (238 ± 102) and naive B6 mice (Fig. 8_A_). Thus, specific activation of bystander T cells did not enhance their ability to mediate damage in the CNS.

Naive, monospecific Dbgp33–41-specific T cells completely reconstitute disease in OT-I mice

The inability of OT-I mice to mount an LCMV-specific immune response (see Fig. 2) indicates that the T cell repertoire is remarkably restricted, especially when one considers that the number of T cell precursors required to spawn an Ag-specific immune response is exceedingly low (51). Knowing this, we next addressed whether it was possible to “rebuild” the disease process in OT-I mice by reconstituting with naive Dbgp33–41-specific precursors. To establish the validity of the transfer model system, we first evaluated the relationship between precursor frequency and the magnitude of the virus-specific immune response in wild-type mice infected i.p. with LCMV Arm. Mice were infected by this traditional route to ensure survival as well as to maximize the efficiency of the LCMV-specific immune response. Before infection, mice received log-serial dilutions of naive GFP+Dbgp33–41-specific (40) CD8+ T cells (ranging from 105–100). At the peak of the virus-specific immune response (day 8 postinfection), splenocytes were harvested and analyzed for the frequency of CD8+ T cells that were also GFP+ (i.e., Dbgp33–41 specific). A perfect sigmoidal relationship (r = 1.0) between the two variables was observed, demonstrating that a plateau in the response was reached when 105 naive precursors were injected (Fig. 9_A_). Because the burst size of the immune response was indeed impacted by the precursor frequency, we surmised that this experimental paradigm could be used to calculate the number of Ag-specific T cells required to rebuild disease in OT-I mice. To this end, OT-I mice received log-serial dilutions (ranging from 104–100) of naive GFP+Dbgp33–41-specific CD8+ T cells and were then infected intracerebrally with LCMV Arm (Fig. 9_B_). As expected, all wild-type control mice succumbed to the disease by day 7 postinfection, whereas OT-I mice receiving no transfer (i.e., 100 cells) survived for the entire observation period (>100 days). Interestingly, we established that as few as 103 (or 1000) naive GFP+Dbgp33–41-specific T cells were able to reconstitute disease in OT-I mice, although the kinetics of the disease process were delayed compared with those in wild-type controls.

Because naive LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells undergo massive clonal expansion after infection (18, 19), the quantity of precursors injected does not necessarily represent the absolute number of effector cells required in the CNS to drive pathogenesis. Thus, we addressed this question by calculating the number of GFP+Dbgp33–41-specific CD8+ T cells in the brain/spinal cord and spleen of OT-I mice receiving the minimum number of precursors required to reconstitute disease (i.e., 103). At the time when overt neurologic dysfunction became apparent, GFP+Dbgp33–41-specific T cells localized to the meninges, ependyma, and choroid plexus of all reconstituted OT-I mice (Fig. 9_C_). Quantitatively, it was determined at this time that an average of 1,287,000 LCMV-specific T cells were present in the spleen, and 51,647 cells were present in the brain/spinal cord (Fig. 9_D_). Because the SD for the collective group was surprisingly small (Fig. 9_D_), these values provide a fair approximation of the number of monospecific Dbgp33–41-specific T cells required to drive pathogenesis and enhance mortality in OT-I mice.

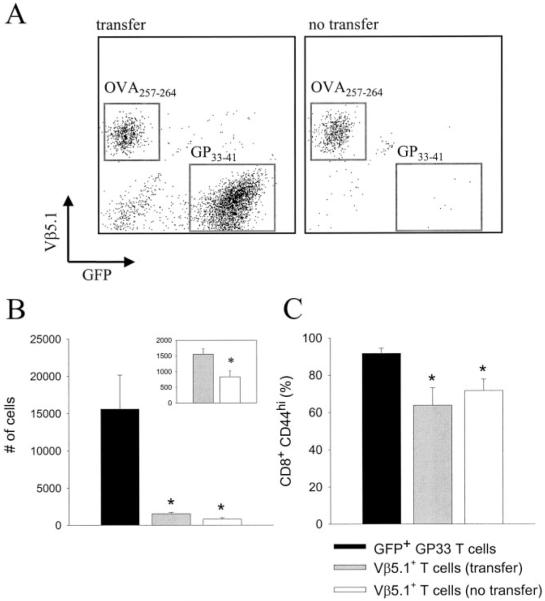

Dbgp33–41-specific T cells only modestly enhance the recruitment of bystander T cells into brain

In our final line of experimentation using this reductionist model system, we evaluated the influence of LCMV-specific T cells on bystander T cell recruitment and activation. Because the biologic system in question (i.e., reconstituted OT-I mice) contained primarily only two CD8+ T cells populations (i.e., Dbgp33–41-specific effectors and KbOVA257–264-specific bystanders), it became possible to address the impact that one monospecific T cell population had on the other. OT-I mice were reconstituted with 104 naive GFP+Dbgp33–41 T cells to restore the normal disease kinetics observed in wild-type mice (see Fig. 10_B_) and compared directly to OT-I mice receiving no transfer. At 7 days after intracerebral infection with LCMV Arm, mononuclear cells were extracted from the brains of both groups and enumerated. As expected, two populations of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells were observed in the brains of symptomatic OT-I mice that received an adoptive transfer (Fig. 10_A_). However, Dbgp33–41-specific T cells had only a small influence on bystander T cell recruitment into the brain. The number of KbOVA257–264-specific T cells in the brain increased by 2-fold in transfer recipients ( p < 0.05; Fig. 10_B_, inset), although this number remained markedly reduced compared with that of Dbgp33–41 T cells ( p < 0.05; Fig. 10_B_). In addition, the activation status of bystander T cells (as measured by CD44 expression) was statistically identical between transfer recipients and controls. Thus, in the acute timeframe analyzed (i.e., 7 days), LCMV-specific effector cells only modestly influence bystander T cell trafficking into the brain.

FIGURE 10.

The influence of Dbgp33–41-specific T cells on bystander T cell recruitment and activation. Representative dot plots of brain-infiltrating leukocytes (gated on CD8) from OT-I mice receiving no transfer (n = 5) or a transfer of 104 GFP+Dbgp33–41-specific CD8+ T cells (n = 5) are shown in A. Both groups (day 7 postinfection) received intracerebral infection with 103 PFU of LCMV Arm. Note the absence of GFP+ T cells in mice not receiving a transfer, whereas the V_β_5.1-expressing bystander T cell population is roughly equivalent in both groups. B, Quantification of the absolute number of brain-infiltrating GFP+ (transfer recipients only) and V_β_5.1+ (transfer vs no transfer) CD8+ T cells. Data are represented as the mean ± SD. Asterisks denote a statistically significant decrease (as determined by one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05) from the number of GFP+ T cells in the brain. B, Inset, The number of V_β_5.1+ T cells on a smaller scale. Student’s t test was used to determine that the values are, in fact, statistically different (p < 0.05). C, The percentage of the aforementioned T cell populations that is CD44high. Data are represented as the mean ± SD. Statistical decreases (asterisks) from GFP+ T cells were determined by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05).

Discussion

When researchers are faced with immunopathology in human disease, the next challenge is to elucidate the potential mechanisms by which this immunopathology develops, with the ultimate intention of devising more efficacious treatment modalities. Although it is widely appreciated that T lymphocytes (both CD4 and CD8) directed against self- or pathogen-specific Ags can mediate tissue destruction, support for the participation of bystander T cells in such processes remains limited (4, 29) and appears to be in contradiction with an important constraint (i.e., peptide-MHC recognition) imposed by the host. At the outset of the present study, we surmised that bystander T cells, if stimulated (either aberrantly or specifically) and recruited to the CNS for a chronic time window (as might be expected to occur in a chronic human disease such as multiple sclerosis), would contribute to nonspecific tissue destruction and subsequent neurologic dysfunction.

Our results revealed, however, that the final component of this hypothesis did not occur, and that specificity is greatly favored over nonspecificity where tissue destruction is concerned. In support of this statement is the fact that bystander CD8+ T cells were unable to reconstitute the fatal meningitis observed in wild-type mice. During an acute time window (i.e., 6–7 days), this observation was perhaps expected given that the prevailing literature supports a notable role for LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells in the lethality of this disease process (34, 42). However, it was anticipated that if recruited into the CNS, bystander CD8+ T cells would have an impact over a chronic time window (i.e., >30 days), especially when considering that LCMV established persistence throughout the brain parenchyma. Indeed, over time, a population of KbOVA257–264-specific T cells with an activated surface phenotype (i.e., CD44high) was recruited from the periphery into the CNS. These cells were anatomically poised in the brain parenchyma and thus had the potential to mediate immunopathology. Moreover, it was revealed that as a consequence of persistent infection, a fraction of these bystander T cells was relieved of their naive status and acquired the ability to release an effector cytokine (i.e., IFN-γ), albeit to a reduced degree compared with LCMV-specific T cells. This observation is in line with several studies demonstrating that bystander activation can occur after viral infection (3–6), although the relevance of such activation has been called into question (52). Regardless, in the present study, activation status, cytokine-producing ability, and retention of bystander T cells within the CNS over an extended time frame appeared to have no bearing on the ability of these cells to participate in immunopathogenesis. Infected OT-I mice remained completely asymptomatic, and there was no evidence of enhanced apoptosis in the CNS despite the sustained presence of bystander T cells. Even specific activation of bystander T cells with cognate peptide did not enhance their ability to mediate CNS damage, which is in opposition with previous studies that achieved bystander-mediated damage in the CNS (29, 30).

In our model system, significant CNS pathology depended entirely on the activities of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells. Wild-type mice containing a diverse repertoire of LCMV-specific T cells showed a prodigious amount of CNS apoptosis in a relatively confined time window (~6 days), which underscores the severity with which CD8+ effector T cells can mediate tissue destruction when directed by specific peptide-MHC interactions. Also supporting this point was the ability of 1000 naive Dbgp33–41-specific CD8+ T cell precursors to become activated, clonally expand, and completely reconstitute disease in OT-I mice. Thus, one monospecific T cell population can drive an entire disease process with lethal consequences.

Although the participation of bystander T lymphocytes in immunopathogenesis remains a theoretical possibility, it seems more plausible that self- or pathogen-specific T cells represent the major driving force behind most T cell-mediated disorders afflicting humans. However, under certain circumstances an aberrant (and perhaps uncontrolled) proinflammatory response may give rise to global activation of the T cell compartment, permitting bystander pathology to occur. For example, an ocular infection of TCR-tg mice with HSV results in the development of lesions in the absence of HSV-specific T cells (4, 31, 32). Curiously, bystander T cell activation and pathology were observed when CD8+ or CD4+ TCR-tg mice were used (53), indicating that either T cell population is capable of performing the task in this model system. Although the specific mechanism by which bystander T cells induce ocular lesions after HSV infection has not been determined, the authors favor the generation of a cytokine storm as the underlying cause (4). Thus, it could be argued that LCMV is not a potent inducer of such cytokines (which presently have not been identified in the HSV system), explaining the inability of bystander T lymphocytes to mediate tissue destruction in our study.

Damage mediated by bystander T cells has also been observed in the CNS white matter of TCR-tg mice infected with mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) (29, 30) and, unlike the HSV model, occurred only with transgenic CD8+ (not CD4+) T cells (54). Furthermore, aggressive immunization strategies (i.e., injection of cognate peptide in CFA) were used to fully activate the transgenic bystander T cell population before infection with MHV, and even then the pathology was never as severe as that observed in wild-type mice containing MHV-specific T cells. Because TCR-tg mice have a reduced number of regulatory CD4+ T cells (especially when crossed on a background deficient in RAG-1) (55–57), activation of an entire monospecific T cell population in the absence of sufficient regulation may inadvertently favor the desired outcome (i.e., bystander T cell-mediated pathology). Although studies of regulatory cells in transgenic mice have focused mainly on those containing a population of monospecific CD4+ T cells, alterations in thymic selection also occur in CD8 TCR-tg mice that significantly reduce the number of CD4+ T cells in the periphery (see Fig. 1_B_). This consequently diminishes the absolute number of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in the circulation. For example, a comparison between wild-type (n = 4) and OT-I (n = 4) mice revealed a 73% reduction ( p < 0.05) in the absolute number of splenic regulatory T cells (1,855,400 ± 344,289 vs 494,113 ± 41,210). Thus, it is important to note that studies reporting pathology induced by bystander T cells have used TCR-tg mice devoid of all other B or T cells (i.e., RAG-1-deficient or SCID mice) (4, 29–32), which, unlike the immunocompetent OT-I mice used in the present study, should have no CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Although it is clear that pathology can be observed under such circumstances, it remains to be determined whether this is a commonly used mechanism of tissue destruction in a physiologic microenvironment replete with a diverse repertoire of B and T lymphocytes. This caveat should be carefully considered when conducting and interpreting studies performed in immunodeficient TCR-tg mice. In fact, the presence of regulatory cells in the OT-I mice used in the present study (although reduced compared with that in wild-type mice) may explain our inability to induce bystander pathology after immunization with cognate Ag.

In conclusion, our study clearly demonstrate that a population of pathogen-specific T cells is a far more potent mediator of tissue destruction in the CNS than bystander T cells of an irrelevant specificity (even when the time window of study is extended to favor bystander T cell activation and pathology). It has been proposed (29) that during a chronic disease process, such as human multiple sclerosis, activation and recruitment of bystander T cells into the CNS may explain the established link between microbial infections and relapses (58). However, given that specific T cells may heavily outweigh their nonspecific counterparts in the ability to efficiently mediate tissue destruction, the aggravation of preexisting self (or pathogen)-specific T cells provides a more suitable explanation for such a link. There appears to be a surprising degree of overlap between heterologous viral infections (59) that may indeed prime cross-reactive responses capable of causing pathology. Furthermore, triggering of self-reactive T cells by molecular mimicry (9–15), bystander activation (3–6), or epitope spreading (7, 8) may also play a fundamental role in lesion exacerbation. In each of the aforementioned scenarios, specificity is a vital component of the pathologic outcome. Because such a high threshold has been imposed by the host for the activation and subsequent release of effector molecules from T cells of an irrelevant specificity, it is likely that bystander T cells are of minimal importance in T cell-mediated disease pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael B. A. Oldstone for his generous support and insightful discussions. Phi Truong participated in this study as a scientific intern from the University of California-San Diego.

Footnotes

1

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI09484 and NS048866-01.

3

Abbreviations used in this paper:

LCMV

lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

Arm

Armstrong 53b

DAPI

4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole

GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

MHV

mouse hepatitis virus

NeuN

neuronal nucleus

tg

transgenic

NP

nucleoprotein

References

- 1.Zinkernagel RM, Doherty PC. Restriction of in vitro T cell-mediated cytotoxicity in lymphocytic choriomeningitis within a syngeneic or semiallogeneic system. Nature. 1974;248:701. doi: 10.1038/248701a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stern LJ, Wiley DC. Antigenic peptide binding by class I and class II histocompatibility proteins. Structure. 1994;2:245. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tough DF, Borrow P, Sprent J. Induction of bystander T cell proliferation by viruses and type I interferon in vivo. Science. 1996;272:1947. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gangappa S, Babu JS, Thomas J, Daheshia M, Rouse BT. Virus-induced immunoinflammatory lesions in the absence of viral antigen recognition. J. Immunol. 1998;161:4289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehl S, Hombach J, Aichele P, Rulicke T, Odermatt B, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R, Pircher H. Viral and bacterial infections interfere with peripheral tolerance induction and activate CD8+ T cells to cause immunopathology. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:763. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horwitz MS, Bradley LM, Harbertson J, Krahl T, Lee J, Sarvetnick N. Diabetes induced by coxsackie virus: initiation by bystander damage and not molecular mimicry. Nat. Med. 1998;4:781. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller SD, Vanderlugt CL, Begolka WS, Pao W, Yauch RL, Neville KL, Katz-Levy Y, Carrizosa A, Kim BS. Persistent infection with Theiler’s virus leads to CNS autoimmunity via epitope spreading. Nat. Med. 1997;3:1133. doi: 10.1038/nm1097-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanderlugt CL, Miller SD. Epitope spreading in immune-mediated diseases: implications for immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:85. doi: 10.1038/nri724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane DP, Hoeffler WK. SV40 large T shares an antigenic determinant with a cellular protein of molecular weight 68,000. Nature. 1980;288:167. doi: 10.1038/288167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujinami RS, Oldstone MB, Wroblewska Z, Frankel ME, Koprowski H. Molecular mimicry in virus infection: crossreaction of measles virus phosphoprotein or of herpes simplex virus protein with human intermediate filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1983;80:2346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.8.2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujinami RS, Oldstone MB. Amino acid homology between the encephalitogenic site of myelin basic protein and virus: mechanism for autoimmunity. Science. 1985;230:1043. doi: 10.1126/science.2414848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oldstone MB, Nerenberg M, Southern P, Price J, Lewicki H. Virus infection triggers insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in a transgenic model: role of anti-self (virus) immune response. Cell. 1991;65:319. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90165-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohashi PS, Oehen S, Buerki K, Pircher H, Ohashi CT, Odermatt B, Malissen B, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Ablation of “tolerance” and induction of diabetes by virus infection in viral antigen transgenic mice. Cell. 1991;65:305. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90164-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao ZS, Granucci F, Yeh L, Schaffer PA, Cantor H. Molecular mimicry by herpes simplex virus-type 1: autoimmune disease after viral infection. Science. 1998;279:1344. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5355.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olson JK, Croxford JL, Calenoff MA, Dal Canto MC, Miller SD. A virus-induced molecular mimicry model of multiple sclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:311. doi: 10.1172/JCI13032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ivanyi J. Milan Hasek and the discovery of immunological tolerance. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:591. doi: 10.1038/nri1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kagi D, Ledermann B, Burki K, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Molecular mechanisms of lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity and their role in immunological protection and pathogenesis in vivo. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1996;14:207. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murali-Krishna K, Altman JD, Suresh M, Sourdive DJ, Zajac AJ, Miller JD, Slansky J, Ahmed R. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity. 1998;8:177. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butz EA, Bevan MJ. Massive expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during an acute virus infection. Immunity. 1998;8:167. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80469-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGavern DB, Homann D, Oldstone MB. T cells in the central nervous system: the delicate balance between viral clearance and disease. J. Infect. Dis. 2002;186:S145. doi: 10.1086/344264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borrow P, Evans CF, Oldstone MB. Virus-induced immunosuppression: immune system-mediated destruction of virus-infected dendritic cells results in generalized immune suppression. J. Virol. 1995;69:1059. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.1059-1070.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Letvin NL, Walker BD. Immunopathogenesis and immunotherapy in AIDS virus infections. Nat. Med. 2003;9:861. doi: 10.1038/nm0703-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kagi D, Ledermann B, Burki K, Seiler P, Odermatt B, Olsen KJ, Podack ER, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Cytotoxicity mediated by T cells and natural killer cells is greatly impaired in perforin-deficient mice. Nature. 1994;369:31. doi: 10.1038/369031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh CM, Matloubian M, Liu CC, Ueda R, Kurahara CG, Christensen JL, Huang MT, Young JD, Ahmed R, Clark WR. Immune function in mice lacking the perforin gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:10854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lieberman J. The ABCs of granule-mediated cytotoxicity: new weapons in the arsenal. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:361. doi: 10.1038/nri1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zinkernagel RM, Doherty PC. The discovery of MHC restriction. Immunol. Today. 1997;18:14. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)80008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slifka MK, Rodriguez F, Whitton JL. Rapid on/off cycling of cytokine production by virus-specific CD8+ T cells. Nature. 1999;401:76. doi: 10.1038/43454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veillette A, Latour S, Davidson D. Negative regulation of immunoreceptor signaling. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002;20:669. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.081501.130710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haring JS, Pewe LL, Perlman S. Bystander CD8 T cell-mediated demyelination after viral infection of the central nervous system. J. Immunol. 2002;169:1550. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dandekar AA, Anghelina D, Perlman S. Bystander CD8 T-cell-mediated demyelination is interferon-')'-dependent in a coronavirus model of multiple sclerosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2004;164:363. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63126-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gangappa S, Deshpande SP, Rouse BT. Bystander activation of CD4+ T cells can represent an exclusive means of immunopathology in a virus infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999;29:3674. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199911)29:11<3674::AID-IMMU3674>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deshpande S, Zheng M, Lee S, Banerjee K, Gangappa S, Kumaraguru U, Rouse BT. Bystander activation involving T lymphocytes in herpetic stromal keratitis. J. Immunol. 2001;167:2902. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borrow P, Oldstone MBA. Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fung-Leung WP, Kundig TM, Zinkernagel RM, Mak TW. Immune response against lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection in mice without CD8 expression. J. Exp. Med. 1991;174:1425. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Griffin DE. Immune responses to RNA-virus infections of the CNS. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:493. doi: 10.1038/nri1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, Heath WR, Howard JL, Bevan MJ, Carbone FR. T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell. 1994;76:17. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clarke SR, Barnden M, Kurts C, Carbone FR, Miller JF, Heath WR. Characterization of the ovalbumin-specific TCR transgenic line OT-I: MHC elements for positive and negative selection. Immunol. Cell. Biol. 2000;78:110. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pircher H, Burki K, Lang R, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Tolerance induction in double specific T-cell receptor transgenic mice varies with antigen. Nature. 1989;342:559. doi: 10.1038/342559a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okabe M, Ikawa M, Kominami K, Nakanishi T, Nishimune Y. ‘Green mice’ as a source of ubiquitous green cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;407:313. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGavern DB, Christen U, Oldstone MB. Molecular anatomy of antigen-specific CD8+ T cell engagement and synapse formation in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:918. doi: 10.1038/ni843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dutko FJ, Oldstone MB. Genomic and biological variation among commonly used lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus strains. J. Gen. Virol. 1983;64:1689. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-8-1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moskophidis D, Cobbold SP, Waldmann H, Lehmann-Grube F. Mechanism of recovery from acute virus infection: treatment of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-infected mice with monoclonal antibodies reveals that Lyt-2+ T lymphocytes mediate clearance of virus and regulate the antiviral antibody response. J. Virol. 1987;61:1867. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.6.1867-1874.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gallimore A, Hombach J, Dumrese T, Rammensee HG, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. A protective cytotoxic T cell response to a subdominant epitope is influenced by the stability of the MHC class I/peptide complex and the overall spectrum of viral peptides generated within infected cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 1998;28:3301. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199810)28:10<3301::AID-IMMU3301>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Most RG, Murali-Krishna K, Whitton JL, Oseroff C, Alexander J, Southwood S, Sidney J, Chesnut RW, Sette A, Ahmed R. Identification of Db- and Kb-restricted subdominant cytotoxic T-cell responses in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-infected mice. Virology. 1998;240:158. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gairin JE, Mazarguil H, Hudrisier D, Oldstone MB. Optimal lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus sequences restricted by H-2Db major histocompatibility complex class I molecules and presented to cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 1995;69:2297. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2297-2305.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonthius DJ, Mahoney J, Buchmeier MJ, Karacay B, Taggard D. Critical role for glial cells in the propagation and spread of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in the developing rat brain. J. Virol. 2002;76:6618. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6618-6635.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hickey WF, Hsu BL, Kimura H. T-lymphocyte entry into the central nervous system. J. Neurosci. Res. 1991;28:254. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490280213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams KC, Hickey WF. Traffic of hematogenous cells through the central nervous system. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1995;202:221. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79657-9_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krakowski ML, Owens T. Naive T lymphocytes traffic to inflamed central nervous system, but require antigen recognition for activation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000;30:1002. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(200004)30:4<1002::AID-IMMU1002>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Westermann J, Ehlers EM, Exton MS, Kaiser M, Bode U. Migration of naive, effector and memory T cells: implications for the regulation of immune responses. Immunol. Rev. 2001;184:20. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1840103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blattman JN, Antia R, Sourdive DJ, Wang X, Kaech SM, Murali-Krishna K, Altman JD, Ahmed R. Estimating the precursor frequency of naive antigen-specific CD8 T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:657. doi: 10.1084/jem.20001021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ehl S, Hombach J, Aichele P, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Bystander activation of cytotoxic T cells: studies on the mechanism and evaluation of in vivo significance in a transgenic mouse model. J. Exp. Med. 1997;185:1241. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Banerjee K, Deshpande S, Zheng M, Kumaraguru U, Schoenberger SP, Rouse BT. Herpetic stromal keratitis in the absence of viral antigen recognition. Cell. Immunol. 2002;219:108. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(02)00601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haring JS, Perlman S. Bystander CD4 T cells do not mediate demyelination in mice infected with a neurotropic coronavirus. J. Neuroimmunol. 2003;137:42. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(03)00041-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van de Keere F, Tonegawa S. CD4+ T cells prevent spontaneous experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in anti-myelin basic protein T cell receptor transgenic mice. J. Exp. Med. 1998;188:1875. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.10.1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hori S, Haury M, Coutinho A, Demengeot J. Specificity requirements for selection and effector functions of CD25+4+ regulatory T cells in anti-myelin basic protein T cell receptor transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:8213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122224799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walker LS, Chodos A, Eggena M, Dooms H, Abbas AK. Antigen-dependent proliferation of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:249. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sibley WA, Bamford CR, Clark K. Clinical viral infections and multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1985;1:1313. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)92801-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Welsh RM, Selin LK. No one is naive: the significance of heterologous T-cell immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:417. doi: 10.1038/nri820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]