Cardiovascular Disease and Breast Cancer: Where These Entities Intersect: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2019 Sep 4.

Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of mortality in women, yet many people perceive breast cancer to be the number one threat to women’s health. CVD and breast cancer have several overlapping risk factors, such as obesity and smoking. Additionally, current breast cancer treatments can have a negative impact on cardiovascular health (eg, left ventricular dysfunction, accelerated CVD), and for women with pre-existing CVD, this might influence cancer treatment decisions by both the patient and the provider. Improvements in early detection and treatment of breast cancer have led to an increasing number of breast cancer survivors who are at risk of long-term cardiac complications from cancer treatments. For older women, CVD poses a greater mortality threat than breast cancer itself. This is the first scientific statement from the American Heart Association on CVD and breast cancer. This document will provide a comprehensive overview of the prevalence of these diseases, shared risk factors, the cardiotoxic effects of therapy, and the prevention and treatment of CVD in breast cancer patients.

Keywords: AHA Scientific Statement, breast cancer, cardiotoxicity, cardiovascular disease, oncology, prevention, risk factors

The number one cause of mortality in US women is cardiovascular disease (CVD),1 yet the general public awareness of this remains suboptimal despite large-scale public education campaigns. Awareness is particularly low in racial and ethnic minority communities.2,3 CVD and breast cancer have individually received significant publicity with media campaigns (such as the Red Dress and Pink Ribbon campaigns); however, there is inadequate public awareness of the coexistence of common risk factors associated with these 2 conditions.

Although cardiology and oncology are often considered separate medical fields, they are frequently intertwined. Multidisciplinary care is critical in the management of cancer patients. Cancer outcomes can be influenced by cardiovascular health: antecedent cardiovascular health can affect cancer treatment selection, and furthermore, cancer care can result in cardiovascular toxicities that could impact ongoing cancer treatment. Finally, latent effects of CVD from cancer treatment can alter cancer survivorship. Much of the intersection between CVD and breast cancer pertains to similarities in predisposing risk factors such as age, tobacco use, diet, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle. CVD risk factors are increased in long-term cancer survivors; however, discussion of CVD prevention and modification of these risk factors during and after cancer treatment is limited.4 The risk of CVD (heart failure [HF], myocardial ischemia, hypertension) is high, and development of CVD risk factors (obesity and dyslipidemia) is higher in older breast cancer survivors than the risk of tumor recurrence. In addition, with advancements in cancer care, survivors could develop latent cardiac effects secondary to the cancer treatment, which can include chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted therapy (eg, trastuzumab).5–7

The field of cardio-oncology has emerged in response to the need to provide the best cancer care without compromising cardiovascular health. Societal committees and new organizations have rapidly emerged to address patients’ needs, including clinical care, research, and education.8,9 Recent societal publications include a consensus statement regarding the training of future cardio-oncologists and guidelines regarding the monitoring and prevention of left ventricular (LV) dysfunction in adult cancer survivors.10,11 Hospitals have been developing and marketing collaborative cardio-oncologic programs to meet rising clinical demands in the field. Lack of formal clinical training programs, funding, and cardiovascular guidelines are some of the unmet needs that will need to be addressed over time to further advance CVD care of cancer patients.8 This scientific statement is the American Heart Association’s first on the connection between CVD and breast cancer. It aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the prevalence of these diseases, shared risk factors, and the cardiotoxic effects of cancer therapy, as well as review the prevention and treatment of CVD in breast cancer patients. Although treatment of cardiotoxicity is not within the scope of this statement, it is clearly an important aspect of cardio-oncology, and it too warrants further research and guideline development.

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

CVD and breast cancer are significant causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States. CVD affects ≈47.8 million women,1 and breast cancer affects ≈3.32 million women.12 On the basis of 2014 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention attributable mortality data in women, 1 in 3.3 deaths was attributed to CVD and 1 in 8.3 deaths was attributed to coronary heart disease (CHD), whereas 1 in 31.5 deaths was attributed to breast cancer.1 Mortality rates for CVD and breast cancer have decreased, with an average decline in CVD deaths (both sexes) by 6.7% per year from 2004 to 2014 and in female breast cancer deaths by 1.8% per year from 2005 to 2014.1,12 Direct annual medical costs in the United States are high: ≈$272.5 billion for CVD, 124.57billionforallcancers,and124.57 billion for all cancers, and 124.57billionforallcancers,and16.5 billion for breast cancer; moreover, these costs are expected to continue to rise.13,14

The lifetime risk of developing breast cancer in women is ≈12.4% based on 2012 to 2014 data. The rate of new female breast cancer cases was 124.9 per 100 000 women per year, with a death rate of 21.2 per 100 000 women per year.12 Nearly 90% of breast cancer patients survive at least 5 years after their initial diagnosis.12 Currently, there are ≈3 million breast cancer survivors in the United States15; however, older women are more likely to die of diseases other than breast cancer, and CVD is the most frequent cause.16,17 In older, postmenopausal women, the risk of mortality attributable to CVD is higher in breast cancer survivors than in women without a history of breast cancer. This greater risk manifests itself ≈7 years after the diagnosis of breast cancer, which highlights the need to reduce the additional burden of CVD during this time frame with early recognition and treatment of CVD risk factors.18

Influence of Race and Age

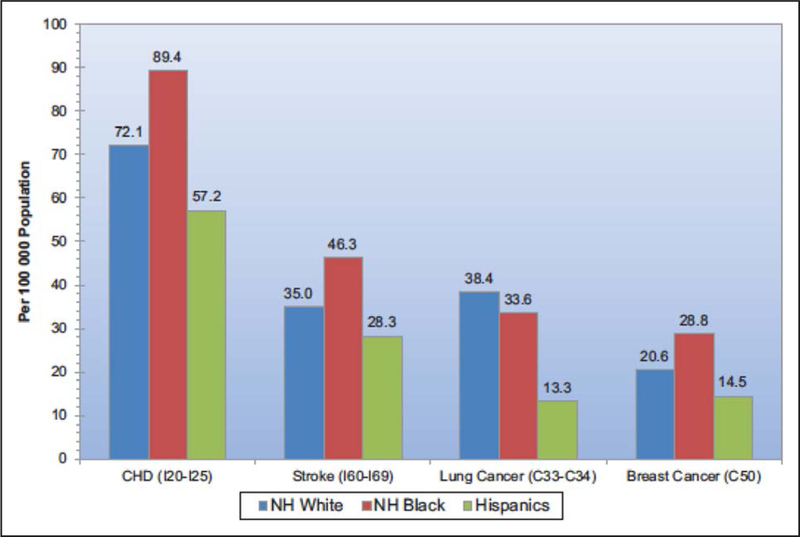

Age-adjusted death rates are higher for CHD and stroke than for breast cancer in non-Hispanic white and black females; however, when race was examined, the rates of CHD, stroke, and breast cancer were higher in non-Hispanic black women than in non-Hispanic white women and Hispanic women (Figure 1).1 There are similar racial-ethnic differences concerning the incidence and mortality rates of breast cancer, with non-Hispanic black women having the highest mortality.5 Non-Hispanic white women 60 to 84 years of age have a higher incidence of breast cancer than black women; however, in black women, the incidence of breast cancer is higher in those <45 years of age, and the mortality rate for breast cancer is higher at all ages.19 Furthermore, American Indian/Alaska Native, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander women have lower breast cancer incidence and mortality rates than non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black women. Additionally, compared with non-Hispanic white women, Hispanic and non-Hispanic black women are more likely to present with later stages of breast cancer,20 which in turn can have a negative impact on clinical outcomes.

Figure 1. Rates of cardiovascular disease and breast cancer in women.

Age-adjusted mortality rates of coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke are higher than that of breast cancer. Death rates are higher in NH black women than in NH white and Hispanic women for CHD, stroke, and breast cancer.1 NH indicates non-Hispanic. Reprinted from Benjamin et al.1 Copyright © 2017, American Heart Association, Inc.

The improved success of screening and treating breast cancer has contributed to the growing number of survivors, more than half of whom are >65 years of age.21 The prognosis of older breast cancer patients is affected by the effective management of preexisting comorbid conditions such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension.22 In older women diagnosed with breast cancer, CVD is the leading cause of mortality, and breast cancer is the second most common cause.23 Not surprisingly, comorbidities, including CVD, in older breast cancer patients have been associated with decreased overall survival.24 The identification and management of cardiovascular risk factors23 in this population is important because CVD, if not recognized and treated, can pose a greater health risk than the cancer itself.22 The expanding role of primary care physicians, oncologists, cardiologists, and allied healthcare providers in survivorship programs is essential to optimize the management of comorbidities to realize the gains seen in breast cancer treatment.25–28

COMMON RISK FACTORS

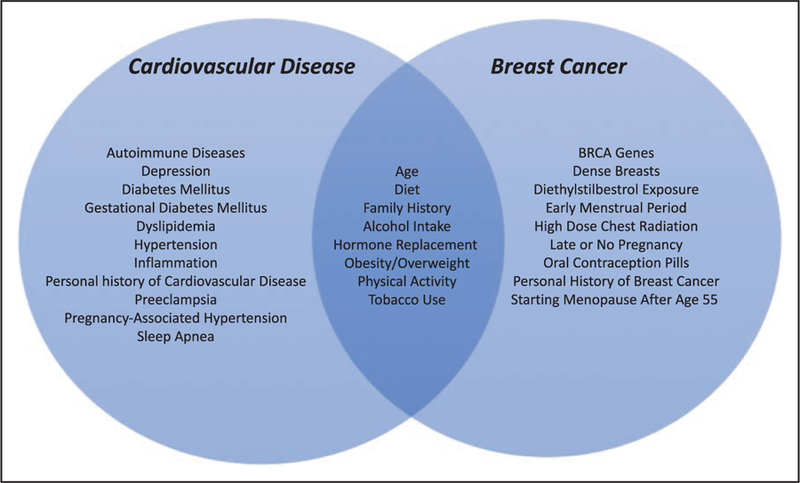

Breast cancer and CVD share a number of common risk factors (Figure 2). Cardiovascular clinical care and research have focused on risk factors for >60 years, because it is believed that ≈80% of CVD can be prevented through risk factor modifications such as promoting a healthy diet, physical activity, and a healthy weight; abstinence from tobacco; blood pressure control; diabetes mellitus management; and a good lipid profile.32 Adherence to a larger number of ideal cardiovascular health behaviors or factors from the American Heart Association’s Life’s Simple 7 health campaign1 is associated with a trend toward a lower incidence of breast cancer (P for trend=0.11).33 The Cardiovascular Lifetime Risk Polling Project, involving 18 cohort studies, found that at age 45 years, individuals with optimal risk factor profiles have a significantly lower lifetime risk of CVD events than those with even 1 major risk factor (4.1% versus 20.2% among women). Having ≥2 risk factors further increased lifetime CVD risk to 30.7% in these women.34 Aggressive management of these cardiovascular risk factors can also substantially reduce the lifetime risk of developing cancer.35 Risk factors for breast cancer have only been discussed more recently, but there is growing awareness that through risk factor modification, some cases of breast cancer might be prevented.36,37

Figure 2. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and breast cancer.

CVD and breast cancer have shared and separate risk factors.19,29–31

Dietary Patterns

Studies of the association between dietary patterns, CVD, and breast cancer typically compare a prudent or healthy dietary pattern (high in vegetables and fruits, poultry, fish, low-fat dairy products, and whole grains) with the Western diet or so-called unhealthy diet (red or processed meats, refined grains, sweets, and highfat dairy products).38 The American Heart Association’s 2020 Impact Goals include a definition of cardiovascular health with a healthy diet pattern that is appropriate in energy balance and consistent with a Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension–type eating plan.39 Dietary habits also affect multiple established cardiovascular risk factors, including blood pressure, cholesterol levels, glucose levels, and obesity.32,40 The NHS (Nurses’ Health Study) found that a dietary pattern consisting of higher intake of vegetables, fruits, fish, poultry, and whole grains (prudent diet) was associated with a 28% lower cardiovascular mortality (relative risk [RR], 0.72; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.60–0.87), whereas a dietary pattern consisting of higher intake of processed or red meats, refined grains, and sweets (Western diet) was associated with a 22% higher cardiovascular mortality (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.01–1.48).41

In contrast, epidemiological data regarding dietary patterns are less consistent in breast cancer. Some reports support prudent dietary patterns as being inversely associated with risk of breast cancer,42–45 whereas others found no association.46–48 The link between breast cancer and a healthy or prudent diet might depend on the tumor type.49 Among 86 261 women in the NHS, a diet high in fruits and vegetables, such as one represented by the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet score, was associated with a lower risk of estrogen receptor (ER)–negative breast cancer. Furthermore, a diet high in plant protein and fat and moderate in carbohydrate content was associated with a lower risk of ER-negative breast cancer.36

Studies of the link between the Western diet and breast cancer have shown positive,50 negative,51 or no associations.46 The relationship between the frequency of consumption of energy-dense foods and fast foods and breast cancer risk was examined in black and white women. Higher consumption of energy-dense foods and fast foods was associated with increased breast cancer risk in both racial groups, with some differences by menopausal and ER status of the tumor.52 The positive association with frequency of fast food intake was stronger among premenopausal black women and postmenopausal white women, for whom a positive trend was also observed with frequent intake of energy-dense foods and sugary drinks. Adjustment for total energy intake attenuated odds ratios (ORs) in black women but strengthened risk estimates in white women. The Western dietary pattern was associated with higher breast cancer risk (OR, for top versus bottom quartile, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.06–2.01), especially in premenopausal women (OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.14–2.67).53

Dietary Fat

Dietary fat is one of the most intensively studied dietary factors related to breast cancer and CVD risk; however, epidemiological studies are difficult to interpret because of the heterogeneity in fat composition. Studies investigating animal and saturated fats, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids, and trans fatty acids have reported that different types of fats differentially affect breast cancer development. Of the subtypes of dietary fat, n-3 PUFA is among the most studied. The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study reported an inverse association between n-3 PUFA intake and breast cancer risk.54 Several case-control studies have found that n-3 PUFA, measured as either dietary intake or with tissue biomarkers, is inversely associated with breast cancer risk.55,56 Other observational studies have found no association between n-3 PUFA and breast cancer risk.57–60 A more recent meta-analysis found that marine n-3 PUFA was associated with a 14% reduction of risk of breast cancer (RR for highest compared with lowest category, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78–0.94), and the RR remained similar whether marine n-3 PUFA was measured as dietary intake or as tissue biomarkers.61

In the WHI (Women’s Health Initiative) dietary modification clinical trial of 48 835 women, reduction of total fat consumption from 37.8% of energy at baseline to 24.3% at 1 year and 28.8% at 6 years had no effect on incidence of major CHD (RR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.88–1.09) or total CVD (RR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.92–1.05) over a mean of 8 years.62 The WHI dietary modification trial of a low-fat, high fruit and vegetable diet also failed to provide a definitive answer as to whether fat intake modifies breast cancer risk (hazard ratio [HR], 0.91; 95% CI, 0.83–1.01 for intervention versus control group after 8 years of follow-up).63 Another randomized trial of reduced fat intake and increased carbohydrate intake in women who were followed for 10 years found no effect of fat intake but an increased risk of ER-positive breast cancer with lower carbohydrate intake.64 In a 20-year follow-up of the NHS, there was no association between fats and breast cancer risk, even when subtypes of fats were considered.65 However, the RR for breast cancer in premenopausal women in the NHS was 1.35 in the highest quartile of dietary fat intake compared with the lowest quartile (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.00, 1.81).66

Blood plasma lipid levels are influenced by diet and weight as well and have been associated with breast cancer risk. In a cohort of 4670 women with increased mammographic density, higher levels of serum highdensity lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and apolipoprotein A1 were associated with increased risk of developing breast cancer (23% and 28%, respectively), whereas higher levels of non-HDL-C and apolipoprotein B were associated with a lower risk of developing breast cancer (19% and 22%, respectively), when compared with the reference group.67 These results demonstrated a possible link between lipids and breast cancer risk, specifically in women with increased mammographic density. The impact of cardiovascular risk reduction strategies on HDL-C and on breast cancer risk needs further study.

Alcohol Consumption

Meta-analyses of epidemiological studies have shown both beneficial and detrimental associations between alcohol intake and all-cause mortality in women, which is a function of the level of consumption and age.68 Observational data from 34 cohort studies demonstrated an association of moderate alcohol intake with reduced all-cause mortality, and in this report, alcohol intake of 5 g/d (a standard alcoholic drink contains 14 g of alcohol) was associated with an 18% reduction in all-cause mortality.69 However, the relationship between alcohol consumption and ischemic heart disease (IHD) is complex. In the NHS, light to moderate alcohol consumption (5 g/d) was associated with a lower risk of total stroke than for nondrinkers (RR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.75–0.92).70 Several meta-analyses of observational studies show evidence for a cardioprotective association of average alcohol intake on IHD risk.71,72 More recently, a systematic review of 44 observational studies found that in women, a steep J-curve was observed for IHD mortality and morbidity, with the lowest risk shown at 11 g of alcohol per day and no cardioprotection at 14 g/d.73 Data from 8 prospective studies revealed an inverse relationship between alcohol intake and CHD. There was a significantly lower risk of CHD among women (mean age, 50 years) with an alcohol intake of up to 30 g/d (RR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.49–0.68) compared with nondrinkers; however, higher levels of daily alcohol intake did not confer additional CVD benefit.74 However, no beneficial effect on IHD was seen with episodic and chronic heavy alcohol drinking.75

Although low to moderate intake of alcohol might decrease the risk for CHD, there are no cancer-related benefits of modest drinking.35 Alcohol consumption is a well-established, modifiable risk factor for breast cancer.76,77 There is considerable variability on how alcohol intake is defined, and this makes direct comparisons between studies difficult. Epidemiological studies, including the WHI,78 support the positive relationship between alcohol and breast cancer risk.79–82 Meta-analyses suggest a 5% to 9% increase in risk per drink per day, or ≤12.5 g/d.83–87 Consuming ≥2 alcoholic drinks per day for 5 years is associated with an 82% increased breast cancer risk compared with no alcohol intake.88 In the NHSII (Nurses’ Health Study II), the risk of breast cancer was 34% higher (RR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.00–1.80) among women 24 to 44 years of age with alcohol intake of ≥15 g/d (≈1.5 drinks per day) compared with women who abstained from alcohol before first pregnancy.89 There was a dose-response relationship between alcohol intake before first pregnancy and breast cancer risk, with an RR of 1.11 (95% CI, 1.00–1.23) for each additional 10-g/d intake; there was no such relationship for alcohol consumption and breast cancer after the first pregnancy. Furthermore, in the NHS, the risk of breast cancer was increased by 21% in adult binge drinkers compared with nondrinkers after controlling for cumulative alcohol intake.82

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease with many subtypes defined by hormone receptor status and histological type. The elevated levels of intracellular estrogens resulting from alcohol intake might act through the ER to promote breast cancer.76 Epidemiological studies have shown that the relationship between alcohol intake and hormone receptor–positive breast tumors was stronger than with other types of breast cancer.85 Compared with never-drinkers, HRs for postmenopausal women who consumed ≥7 drinks per week were as follows: for ER-positive breast cancer, 1.48 (95% CI, 1.19–1.83); for progesterone receptor (PR)–positive cancer, 1.64 (95% CI 1.31–2.06); and for mixed/ductal/lobular cancer, 2.51 (95% CI, 1.20–5.24).90 The risks for ER-positive/PR-positive and ER-positive/PR-negative breast cancer increased by 8% (95% CI, 2%–15%) and 12% (95% CI, 0%–25%), respectively, per drink per day among postmenopausal women,91 which is comparable to the 12% increase in risk of ER-positive tumors per 10 g/d of alcohol intake reported in a meta-analysis of prospective and case-control studies.85

Meat Consumption

The association between meat consumption and breast cancer is not well understood. Among a large cohort of women in the United Kingdom, increased consumption of total and nonprocessed meat was associated with a higher risk of premenopausal breast cancer, and total processed meat and red meat consumption was positively associated with postmenopausal breast cancer.92 A case-control study found that processed meat intake, even just 1 or 2 times per week, was associated with a 2.7-fold (OR, 2.65; 95% CI, 1.36–5.14; _P_=0.004) higher likelihood of developing breast cancer, but red, white, and grilled meat intake was not.93 A study of 4684 French women found that processed meat intake was associated with higher breast cancer risk (HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 0.92–2.27), and this association was stronger when cooked ham was excluded and manifested only in women who were not taking antioxidant supplements.94 Among the 44 231 participants of the NHSII cohort, greater consumption of red meat in adolescence was significantly associated with higher premenopausal breast cancer risk (highest versus lowest quintiles: RR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.05–1.94) but not postmenopausal breast cancer.95 Others have found weak positive associations between meat consumption and breast cancer.96,97 Several studies have linked red and processed meat intake with increased mortality98 and acute coronary events.99

Collectively, the evidence for the influence of diet on breast cancer and CVD risk is mixed. The results of epidemiological studies must be interpreted cautiously, because these studies cannot determine causation. The sample size, measurement error in nutrients and in outcome variables, and individual variation in human genetics and lifestyle factors limit the ability to measure the effect of diet on breast cancer.100 This is largely because of uncontrolled confounding factors and differences in study designs and measurement of end points. It appears that dietary factors are particularly important in determining premenopausal breast cancer risk. Likewise, there is increasing evidence to suggest the importance of alcohol consumption in the development of breast cancer. Understanding the impact of diet on breast cancer risk will require examination of gene-environment interactions and long-term epigenetic mechanisms. Some promising work has found that gut microbiota is less diverse and compositionally different in postmenopausal women with breast cancer than in similar women without breast cancer.101 Breast cancer risk can be affected by obscure early-life effects that are transmitted through the maternal line.102 It is plausible that the infant’s gut microbiota composition could influence breast cancer risk in adulthood.

Physical Activity

About 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week is recommended for all Americans.103 Only 17.6% of American women meet these physical activity guidelines.32 Strong evidence supports the elevated risk that inactivity (<150 min/wk) poses for both CVD and breast cancer.32,104 Globally, physical inactivity is believed to be responsible for 12.2% of the burden of myocardial infarction after accounting for other CVD risk factors including cigarette smoking, hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, alcohol, and psychosocial factors.105 A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies of women found that the RRs of incident CHD were 0.83 (95% CI, 0.69–0.99), 0.77 (95% CI, 0.64–0.92), 0.72 (95% CI, 0.59–0.87), and 0.57 (95% CI, 0.41–0.79) across increasing quintiles of physical activity compared with the lowest quintile.106 Women in the CARDIA study (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) who maintained high physical activity through young adulthood gained about 6 fewer kilograms of weight and about 3.8 fewer centimeters in waist circumference in middle age than those with lower activity.107 Similarly, among US women, every additional daily hour of television watching was associated with 0.3 lb of greater weight gain every 4 years, whereas every hour per day of less television watching was associated with a similar amount of relative weight loss.108 A study of >1 million women followed up over 9 years found that moderate physical activity but not strenuous physical activity was associated with lower risk of CHD or a cardiovascular event.109 Conversely, in a population-based study in Australia, among adults followed up for 6 years and reporting any moderate to vigorous physical activity, the proportion of vigorous activity showed an inverse doseresponse relationship with all-cause mortality compared with those reporting no vigorous activity.110

Studies have consistently shown that moderate to vigorous physical activity is associated with a decreased breast cancer risk among both premenopausal and postmenopausal women who are more active versus those who are less active.111 Several mechanisms have been proposed for how physical activity potentially reduces breast cancer risk, including reduced exposure to estrogen and androgens, insulin-related factors, adipokines, and inflammation.112,113 A meta-analysis of 29 observational studies found a significant reduction in breast cancer risk among the most physically active compared with the least active women.114 A more recent meta-analysis of 22 studies involving 123 574 participants found an inverse relationship between physical activity and breast cancer events and deaths.115 Compared with those who reported low or no lifetime recreational prediagnosis physical activity, those who reported high lifetime recreational physical activity had a significantly lower risk of breast cancer–related death (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.54–0.98). Additionally, significant risk reduction for breast cancer–related death was demonstrated in women who had engaged in recreational physical activity more recently before diagnosis (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73–0.97). In NHSII, data showed that physical activity at ages 14 to 17 years was associated with a 15% lower risk of premenopausal breast cancer.116

Sedentary Lifestyle

Sedentary behavior is defined as activities performed in a sitting or reclining posture with an energy expenditure typically in the range of 1.0 to 1.5 times the basal metabolic rate.117 Sedentary behavior is also characterized by prolonged sitting or lying down and absence of whole-body movement, such as watching television or other forms of screen-based entertainment and car driving.118,119 Previous research suggests that sedentary behavior has been associated with CVD and breast cancer.120,121 In the WHI observational study involving 71 018 women, sitting for ≥10 hours each day compared with <5 hours each day was associated with increased CVD risk (HR, 1.18) in multivariable models that included physical activity. Low physical activity was also linked with higher CVD risk.122

Sedentary behavior has also been associated with high breast density, which has been shown to be a strong, independent risk factor for breast cancer, with a 4- to 6-fold increased risk compared with the least dense breasts.123,124 A case-control study found that for women in the highest quartile of physical activity compared with those in the lowest quartile, time spent in moderate to vigorous activity (measured by accelerometer) was inversely associated with risk of developing breast cancer after adjustment for known risk factors, sedentary behavior, and time spent wearing the accelerometer. They also found that sedentary behavior was positively associated with breast cancer, independent of moderate to vigorous activity (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 0.27–0.56; _P_trend<0.001).125 In the Southern Community Cohort Study, sedentary behavior for ≥12 h/d compared with <5.5 h/d was associated with increased odds of breast cancer among white women (OR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.01–3.70) but not black women (OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 0.82–1.83) after adjustment for physical activity (measured as metabolic equivalent hours per day).126 The racial differences noted in this study might be explained by variation in determining physical activity and underlying biological mechanisms that impact breast cancer risk. Independent of one another, sedentary behavior and physical inactivity are risk factors for breast cancer among white women. Reducing sedentary behavior and increasing physical activity are potentially independent targets for breast cancer prevention interventions.

Obesity, Overweight, and Body Mass Index

Overweight and obesity (body mass index [BMI] of ≥25 and ≥30 kg/m2, respectively) are major risk factors for CVD127; furthermore lifetime obesity and physical inactivity increase the risk of CVD. Severe obesity (class III, body mass index ≥40 kg/m2) may pose an even greater CVD risk than class I or class II obesity.128 Among women in the WHI (n=156 775) with severe obesity compared with normal BMI, HRs (95% CIs) for mortality were on the order of 1.5 to 2.6 across black, Hispanic, and white women. For CHD, HRs were 2- to nearly 3-fold higher. However, CHD risk was strongly related to CVD risk factors across BMI categories even in severe obesity, and CHD incidence was similar by race/ethnicity when adjusted for differences in BMI and CVD risk factors.128 A meta-analysis of white adults over a mean follow-up of 10 years reported that among women, overweight and obese status (and perhaps underweight) based on BMI correlated with elevated all-cause death.129

Obesity is also a factor that is associated with breast cancer risk specifically in postmenopausal women.130,131 The relationship between obesity and breast cancer is complex. A dose-response meta-analysis found that each 5-kg increase in adult weight gain was associated with an 11% increased risk of postmenopausal breast cancer among nonusers of hormone replacement therapy (HRT; RR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.08–1.13); there was no evidence of a linear relationship for premenopausal breast cancer (RR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.95–1.03).132 Furthermore, higher BMI (overweight-to-obese category) among women at age 18 years was associated with a 24% lower risk of breast cancer in premenopausal women compared with low BMI (95% CI, 0.60, 0.96, _P_trend=0.09).133 A BMI in the morbidly obese category, compared with normal- to low-weight BMI, was associated with a 19% reduced breast cancer risk (95% CI, 0.61–1.06; _P_trend=0.05) in premenopausal women. A meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies of premenopausal women found an inverse relationship between BMI and breast cancer risk. There was a 5% reduced risk for developing premenopausal breast cancer with a 5-kg/m2 increase in BMI.134 Stratified by ethnicity, the inverse association remained for black (RR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.91–0.98) and white women (RR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.91–0.95) but not for Asian women. However, for waist-hip ratio, the dose response showed a statistically significant increase in RR of 8% for each 0.1 increment, with the largest association detected in Asian women (19%; RR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.15–1.24).134

Investigators of the NHS and NHSII observed that childhood and adolescent body fatness was significantly associated with a 20% to 50% decreased breast cancer risk throughout life, regardless of menopausal status.135 More recently, investigators of the NHS evaluated the link between recent weight change and total premenopausal and postmenopausal invasive breast cancer and hormone receptor status subtypes while controlling for average BMI before and after menopause.136 Short-term weight change was significantly associated with breast cancer risk (RR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.09–1.33) for a 4-year weight gain of ≥15 lb versus no change (≤15 lb). The association was stronger for premenopausal women (RR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.13–1.69) than for postmenopausal women (RR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.97–1.25). Premenopausal short-term weight gain had a stronger association for ER-positive/PR-negative (RR per 25-lb weight gain, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.33–3.61) and ER-negative/PR-negative breast cancer (RR per 25-lb weight gain, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.09–2.38) than for ER-positive/PR-positive breast cancer (RR per 25-lb weight gain, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.89–1.43). This study supported the deleterious effects of short-term weight gain, particularly before menopause, even after controlling for average BMI before and after menopause.136 Regardless of levels of adolescent physical activity, early-life body leanness of 74 723 women in the NHSII was significantly associated with higher breast cancer risk; the association was slightly attenuated among those who were active during adolescence compared with those who were inactive.137 Increased breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women who had adolescent leanness was confined to those who gained excess weight during adulthood.138

Tobacco Use

Although cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for CVD and stroke, the link between cigarette smoking and breast cancer remains inconclusive. A meta-analysis comparing pooled data of ≈2.4 million smokers and nonsmokers found that the RR for smokers compared with nonsmokers for developing CHD was 25% higher in women than in men (95% CI, 1.12–1.39).139 The association between smoking and breast cancer risk has been evaluated extensively in epidemiological studies, with an emerging consensus for a weak, positive association.140 One large Canadian study found a non-significant trend toward increased breast cancer risk in premenopausal women who were active smokers or began smoking before their first pregnancy.141 Moreover, several studies reported an increased breast cancer risk associated with smoking for long durations and initiation early in life.142–146 The association between passive or sidestream smoke and breast cancer is also mixed. Some reports have found an association,147,148 whereas others have not.149 Genetic variants in enzymes involved in the metabolisms of carcinogens are postulated to modify the association between smoking and breast cancer risk.150,151 More recent meta-analyses report a significant interaction between smoking and carcinogen-metabolizing genotype variants (eg, NAT2); smokers carrying the slow acetylator variant NAT2 genotypes had an increased breast cancer risk,152 and among women with high pack-years of smoking exposure, the NAT2 slow acetylator variant genotypes were associated with an increased breast cancer risk.153

Age

The incidence of breast cancer increases with advancing age, doubling approximately every 10 years until menopause is reached, at which time the rate of increase slows.154 The incidence of CVD increases steadily with advancing age, but the rate of increase becomes steeper at menopause, rather than slowing.155 Age is obviously not changeable, so its role in prevention is as a risk predictor rather than a modifiable risk factor.

Age at Menarche and Menopause

In addition to age in general, age of menarche and menopause is an additional age-related risk factor for both breast cancer and CVD. Women who start menstruating earlier in life (early menarche) have an increased risk of developing breast cancer.154 These women also have a higher risk for developing CVD, particularly in nonsmoking populations.156,157 In terms of menopause, women who undergo menopause earlier in life (early menopause) have an increased risk of developing CVD158 but a decreased risk of developing breast cancer. Women undergoing menopause after the age of 55 years are twice as likely to develop breast cancer as women who undergo menopause before the age of 45.154

Postmenopausal HRT

Several studies have shown an association between postmenopausal hormone use and risk of breast cancer. The NHS study followed >100 000 healthy women 30 to 50 years of age at the time of enrollment and found that the risk of developing breast cancer was 1.2 to 2 times greater for women who reported ≥5 years of current use of HRTs than for those who never used HRT.159 Long-term cumulative follow-up data of postmenopausal women with hysterectomy from the WHI demonstrated a 45% lower risk of breast cancer–related mortality in those randomized to estrogen-only therapy than in those given placebo. However, postmenopausal women with an intact uterus who were randomized to combination therapy of estrogen plus progestin had a 44% increase in breast cancer mortality compared with those in the placebo arm, although this result did not meet statistical significance.160

Several studies have now also reported that HRT is associated with an increased risk of CVD in older postmenopausal women and women with CHD.161,162 The largest of these studies is the WHI, which randomized >16 000 postmenopausal women (average age 63.3±7.1 years) with no history of coronary artery disease to receive either estrogen alone, estrogen combined with progesterone, or placebo and then followed them for an average of 5.6 years. The estrogen plus progestin arm was prematurely terminated (after 5.2 years of follow-up), and at the time of study discontinuation, there was an increased risk of CHD with HRT (HR, 1.29; nominal 95% CI, 1.02–1.63).162 These data confirm that postmenopausal HRT is associated with both breast cancer and CVD (stroke, thromboembolic events, CHD), and this is a potentially modifiable risk factor for both diseases.159,162,163

Genetics

Clinical and population-based studies have demonstrated that genetic factors play important roles in both breast cancer and CVD, and genes involved in the development of breast cancer and CVD have been identified. Two breast cancer susceptibility genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2) are thought to account for between 5% and 10% of all breast cancer cases.164 Genetics plays a role in therapies as well. Therapies have been developed to target genes shown to be important in progression of breast cancer, such as the HER2 (c-erbB-2) oncogene.165 These discoveries have greatly enhanced our ability to detect and treat breast cancer. Although genes involved in the development of CVD have also been identified,166–168 we have not been able to identify a single gene responsible for a substantial proportion of cases, such as with the relationship of BRCA1 and BRCA2 to breast cancer. Animal studies have demonstrated an important role of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in cardiac injury responses and an increased susceptibility of mice harboring the cardiomyocyte-specific BRCA mutation to develop HF after anthracycline exposure.169 However, human studies in women who are BRCA mutation carriers did not identify a higher risk of myocardial dysfunction after breast cancer treatment with doxorubicin.170

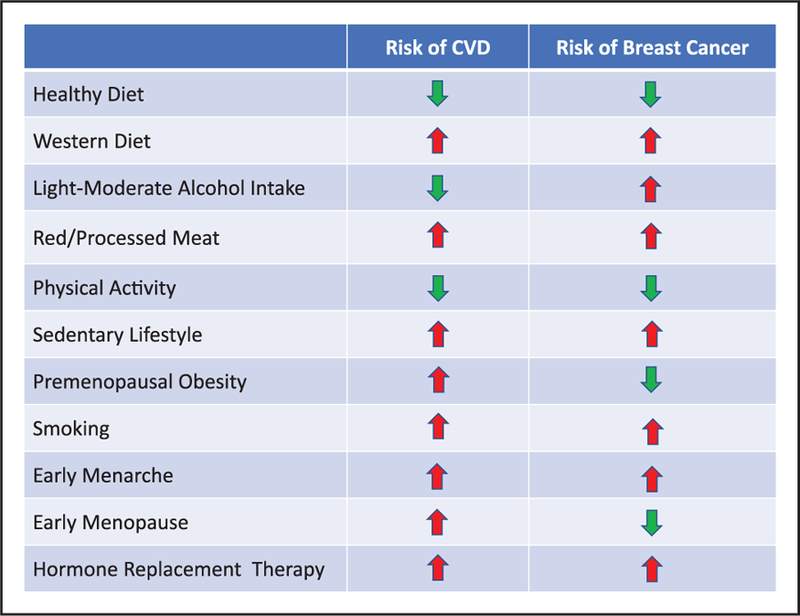

Although most of the risk factors that are common to both CVD and breast cancer move risk in the same direction (ie, decrease or increase risk in both diseases), a few risk factors move risk in opposite directions (Figure 3). Decreased risk for developing CVD but increased risk for developing breast cancer was associated with low to moderate alcohol intake, whereas increased risk for CVD but decreased risk for breast cancer was associated with early menopause and premenopausal obesity. Knowledge and understanding of the risk factors for CVD and breast cancer will contribute to a better understanding of how best to prevent both diseases.

Figure 3. Factors associated with developing CVD and breast cancer.

Impact of these factors in a positive (green downward arrow, reduced risk) or negative (red upward arrow, increased risk) on developing CVD or breast cancer.19,29–31 CVD indicates cardiovascular disease.

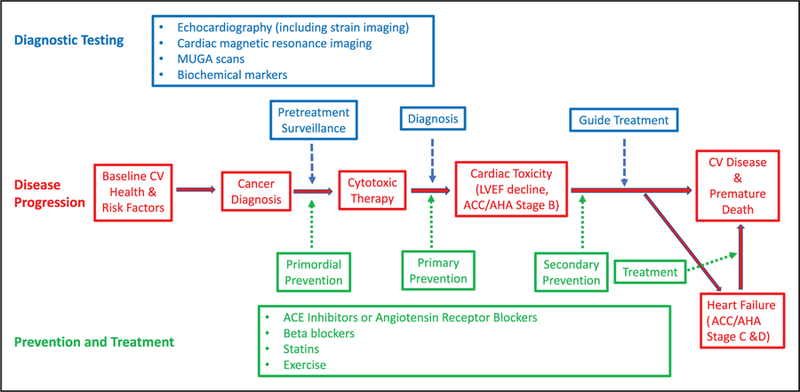

CARDIOVASCULAR EFFECTS OF CANCER THERAPY

Cancer treatment can result in early or delayed cardiotoxicity that can vary from LV dysfunction to overt HF, hypertension, arrhythmias, myocardial ischemia, valvular disease, thromboembolic disease, pulmonary hypertension, and pericarditis. The most commonly reported and monitored side effect of chemotherapy is LV systolic dysfunction.171 Arrhythmias, independent of other concurrent cardiac disease, can occur from breast cancer treatment, including chemotherapy and radiation therapy (RT).172 Several chemotherapeutic agents can also prolong QT intervals.173 The absence of a clear consensus in definitions of cardiotoxicity makes it difficult to compare results of cardiac end points between clinical trials and furthermore makes the applicability of these findings in the real world challenging at best. This section will briefly review the pathophysiological mechanisms and resultant adverse cardiovascular effects of common therapies for breast cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cancer Treatment and Cardiovascular Adverse Effects

| Cancer Treatment | Cardiovascular Adverse Effects |

|---|---|

| Anthracyclines (eg, doxorubicin, epirubicin) | Left ventricular dysfunction, heart failure, myocarditis, pericarditis, atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation |

| Alkylating agents (eg, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide) | Left ventricular dysfunction, heart failure, myocarditis, pericarditis, arterial thrombosis, bradycardia, atrial fibrillation, supraventricular tachycardia |

| Taxanes (eg, paclitaxel) | Bradycardia, heart block, ventricular ectopy |

| Antimetabolites (eg, 5-fluorouracil, capecitabine) | Coronary thrombosis, coronary artery spasm, atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation |

| Endocrine therapy (eg, tamoxifen, anastrozole, letrozole) | Venous thrombosis, thromboembolism, peripheral atherosclerosis, dysrhythmia, valvular dysfunction, pericarditis, heart failure |

| HER-2–directed therapies (eg, trastuzumab, pertuzumab) | Left ventricular dysfunction, heart failure |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors (eg, palbociclib, ribociclib) | QTc prolongation |

| Radiation therapy | Coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathy, valvular disease, pericardial disease, arrhythmias |

Chemotherapeutic Agents

Anthracyclines

Anthracyclines, such as doxorubicin, have been used successfully in the treatment of various neoplasms such as breast cancer since the 1970s, but their use can result in significant irreversible LV dysfunction. Doxorubicin interacts with DNA, intercalating and inhibiting macro-molecular biosynthesis and inhibiting the progression of the topoisomerase IIβ within cardiac myocytes. By intercalating into the DNA, the anthracyclines bind to topoisomerase IIβ and disrupt replication, causing myocyte cell death.174,175 Another central mechanism that has been postulated is the generation of reactive oxygen species, which damage DNA, proteins, and lipids, including the mitochondrial membrane, and accelerate myocyte death.176 Anthracyclines also form complexes with intracellular iron, which in turn generate oxygen radicals. Interestingly, individuals with higher iron stores exhibit increased anthracycline toxicity.177

The myocardial toxicity of the anthracyclines can manifest early or late after exposure. The early manifestations could be related to inflammation resulting in a pericarditis-myocarditis syndrome,178 whereas the late manifestations are related to actual myocyte damage that results in the clinical syndrome of HF. Cell death has been confirmed by rising troponin levels.179 The risk of HF increases with increasing cumulative doses of anthracyclines; for instance, with doxorubicin, there is an ≈5% risk at a dose of 400 mg/m2, a 26% risk at a dose of 550 mg/m2, and up to a 48% risk at a cumulative dose of 700 mg/m2.

However, there is no “safe dose” threshold, because individuals exposed to lower doses of anthracycline (<400 mg/m2), particularly those with underlying cardiovascular risk factors, are also at risk of experiencing cardiotoxicity.180–182 Most at risk for anthracycline-mediated cardiotoxicity are older patients, those with a prior cardiac pathology, and those who have been exposed to concomitant chemotherapy or RT (Table 2).11,183–185 Detailed cardiovascular phenotyping has suggested that on average, there are modest but persistent declines in LV ejection fraction (LVEF) of ≈4% even at 3 years after anthracycline exposure.186 LV functional recovery and reduction in cardiac events might be possible with early detection and prompt treatment of LV dysfunction; however, complete LVEF recovery was not seen in patients treated >6 months after completion of chemotherapy.187

Table 2.

Risk for Developing Cardiac Dysfunction

| At-risk therapies including any of the following: |

|---|

| High-dose anthracycline therapy: doxorubicin ≥250 mg/m2 or epirubicin ≥600 mg/m2 |

| High-dose radiation therapy when heart is in the field of treatment: radiotherapy ≥30 Gy |

| Sequential treatment: lower-dose anthracycline therapy (doxorubicin <250 mg/m2 or epirubicin <600 mg/m2) and then subsequent treatment with trastuzumab |

| Combination therapy: lower-dose anthracycline (doxorubicin <250 mg/m2 or epirubicin <600 mg/m2) combined with lower-dose radiation therapy when heart is in the field of treatment (<30 Gy) |

| Presence of any of the following risk factors in addition to treatment with lower-dose anthracycline or trastuzumab alone: |

| Older age at time of cancer treatment (≥60 y) |

| ≥2 CVD risk factors during or after cancer treatment: diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension, obesity, smoking |

| History of myocardial infarction, moderate valvular disease, or low-normal left ventricular function (50%–55%) before or during cancer treatment |

Doxorubicin-based adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer has been found to cause arrhythmias and conduction abnormalities in 2.6% of patients versus 1% of patients who did not receive doxorubicin.188 Anthracyclines are associated with atrial fibrillation (2%–10%), which can occur acutely during or after chemotherapy.189 An individualized patient-centered approach to decisions regarding the use of antithrombotic agents in the management of atrial fibrillation is recommended, with careful consideration of the benefits and risks of treatment.171,190 Ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation are less likely to be associated with anthracycline treatment.189 The burden of arrhythmias detected on defibrillators in patients with anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy is similar to those with other forms of cardiomyopathy (non-anthracycline chemotherapy or IHD), with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia as the most common arrhythmia, followed by atrial fibrillation and then sustained ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation.191 A small study of long-term survivors with childhood cancers treated with anthracyclines, especially with concomitant chest radiation, found that prior anthracycline therapy was associated with a prolonged corrected QT interval of 0.43 or higher, but no torsade de pointes was documented.188

Structural analogues of doxorubicin, such as epirubicin (commonly used in Europe and Canada), were suggested to have lower clinical cardiotoxicity than doxorubicin (OR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.2–0.78).192 However, a recent Cochrane database review of 5 randomized trials (1036 patients) comparing doxorubicin and epirubicin did not find a statistically significant difference in HF incidence between the 2 regimens (RR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.12–1.11),193 and therefore, epirubicin should not be perceived as cardioprotective or less cardiotoxic.

Alkylating Agents

Alkylating agents, including cisplatin and cyclophosphamide, can also damage DNA, resulting in cytotoxicity and myocyte death. Histopathology shows interstitial hemorrhage, edema, and necrosis. Cyclophosphamide has been the alkylating agent most commonly used in the treatment of breast cancer. Clinical cardiotoxicity with cyclophosphamide is extremely rare, can occur within 10 days of administration, and appears to be related to prior anthracycline therapy or mediastinal radiation.194–196 Myocarditis and pericarditis have also been described but are rare.197,198 Bradycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, and atrial fibrillation have also been reported in patients receiving systemic alkylating agents.171,189,199–201

Taxanes

Taxanes, such as paclitaxel, act as microtubule poisons and block mitotic cycle progression by affecting microtubule processes and producing abnormal spindles and by disrupting mitosis, which results in apoptosis.202 Taxanes are important agents in the treatment of early and advanced breast cancer. Taxanes can be given sequentially or in combination with anthracyclines in early-stage breast cancer. Sequencing of taxanes alters the pharmacokinetics of anthracyclines but is not known to directly result in HF.203

Administration of paclitaxel has been associated with bradycardia; 29% of patients in the phase II paclitaxel clinical trials experienced heart rates <40 bpm.204 Other rhythm disturbances noted in patients with rhythm monitoring were asymptomatic left bundle-branch block and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, which was also noted when paclitaxel was combined with cisplatin. It is unclear whether the rhythm disturbances observed with paclitaxel might have been caused by the formulation vehicle, polyethoxylated castor oil, or premedication with H1 and H2 antagonists to prevent hypersensitivity reactions.204

Antimetabolite Drugs

The antimetabolite drugs, in particular 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and capecitabine (a prodrug that is enzymatically converted to fluorouracil in the tumor), are pyrimidine analogues that disrupt DNA and RNA synthesis.205 These agents have been used as first-line therapy (capecitabine alone or intravenous 5-FU in combination with other cytotoxic agents) for metastatic breast cancer and in combination with anthracyclines (5-FU, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide) in early-stage breast cancer. The most commonly described cardiac side effect is chest pain; however, myocardial infarction, HF, and arrhythmias have been reported, albeit rarely.206–208 Mechanisms that have been attributed to the chest pain include thrombosis or coronary arterial vasospasm.209 These symptoms usually resolve by stopping the drug infusion.210,211 Patients without coronary artery disease can also develop ischemia but at a much lower incidence than in those with pretreatment coronary artery disease (1.1% versus 4.5%).212 Cardiotoxicity incidence varies in the literature, ranging between 1% and 68% with 5-FU, and can occur early after treatment because of high, continuous-infusion doses, which is rare in the treatment of breast cancer.206–208,212–215 Cardiotoxicity (vasospasm) with 5-FU can occur in the acute setting (during intravenous infusion) or can be delayed (2–5 days after administration). Long-term cardiotoxicity with 5-FU is uncommon.216 Other reported risk factors for cardiotoxicity with 5-FU include previous mediastinal RT, antecedent history of CVD, and concurrent use of combination chemotherapeutic agents.206,212,215 Arrhythmias induced by 5-FU and capecitabine, including ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation, are mostly ischemic in origin and usually occur in the context of coronary artery spasm; however, there are also reported cases of atrial fibrillation, atrial/ventricular ectopy, and QT prolongation.217–221

Endocrine Therapy

Endocrine therapy has an important role in the treatment of patients with breast cancer expressing ER or PR. In early-stage hormone receptor–positive breast cancer, use of adjuvant tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors (AIs) reduces cancer recurrence rates, improves overall survival, and is recommended by the current clinical practice guidelines.222 Hormonal therapies act by interrupting the cellular processes through which estrogen promotes growth of normal and cancerous tissue, and importantly, the differences in their molecular targets determines their cardiovascular and overall side-effect profile. Two main strategies are interference with estrogen signaling by competitive binding to ER, represented by tamoxifen, and inhibition of endogenous estrogen production, as in the case of AIs. In the adjuvant setting, endocrine therapy is prescribed for an extended period, often ≥5 years, which emphasizes the importance of detailed evaluation of its overall toxicity and cardiovascular side-effect profile. Tamoxifen is the endocrine therapy of choice for premenopausal women, whereas strategies in postmenopausal women can include tamoxifen, AIs, or a sequential combination, with careful weighing of benefits and management of toxicity risks.222

Tamoxifen

Tamoxifen, a hormonal agent approved for treatment of early breast cancer >30 years ago, is a selective ER modulator that interferes with estrogen binding to ER and in turn alters the expression of genes downstream from ER.223 The effects of the selective ER modulator/ER nuclear receptor transcription complex on gene transcription are determined by the presence and preferential binding of corepressors and coactivators in different tissues and account for their tissue-specific estrogen agonist and estrogen antagonist actions. In breast tissue, tamoxifen exhibits estrogen antagonist activity, and the competitive binding of tamoxifen to ER leads to the inhibition of estrogen-dependent tumor growth. ER antagonism is also the mechanism of some adverse effects of tamoxifen, including hot flashes and mood disturbances. However, in most organs, including the cardiovascular system, bone, and uterus, tamoxifen has estrogen agonistic activity, which can result in beneficial or detrimental effects, depending on the affected tissue. Tamoxifen has a favorable effect on the lipid profile, with reductions in total serum cholesterol (in the range of 10% to 15%) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (reductions ranging from 15% to 22%), but no significant changes in HDL-C.224–227 Smaller studies reported increases in triglyceride levels in Asian patients treated with tamoxifen and raised concerns about hypertriglyceridemia,228,229 but the broader clinical relevance of these findings remains unknown.

Despite observed favorable effects and the reductions in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and total cholesterol levels, long-term data from clinical trials have failed to demonstrate a protective effect of tamoxifen with regard to hard cardiovascular end points. In the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group overview,230 which included 55 trials and 37 000 women, there was no difference in cardiac or vascular death between adjuvant and placebo groups. This was similar to the findings in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B14,231 which reported only a small number of cardiac or vascular deaths, with no statistically significant difference between tamoxifen and placebo groups. These results indicate the need for cautious interpretation of surrogate end points, such as lipid profile, which did not translate into a clinically relevant benefit of prevention of CVD death. Interesting comparisons have been made between findings in tamoxifen trials and the WHI study, which used HRT in postmenopausal women. Despite the lowering of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and the increasing of HDL-C levels (but also increased triglyceride levels) in the WHI, HRT did not confer cardiovascular protection.162,232

In contrast to its protective effects on lipid metabolism, the estrogen-agonistic actions of tamoxifen result in a detrimental increase in thrombogenicity and increased risk of venous thrombosis and thromboembolism.233 Later studies that compared AI to tamoxifen demonstrated a reduced risk of thrombosis with AIs, presumably because of their lack of proestrogen effects. A meta-analysis of randomized adjuvant endocrine trials reported the incidence of thrombosis at 2.8% in the tamoxifen group compared with 1.6% in the AI group.234 Venous thromboembolism is associated with mortality and significant morbidity related to deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and long-term sequelae such as pulmonary hypertension, which highlights the need to consider other risk factors (eg, history of stroke) when selecting endocrine therapy for women with ER-positive breast cancer.235

Aromatase Inhibitors

AIs act by inhibiting the aromatase enzyme and depleting estrogen levels in postmenopausal women. Circulating estrogen is made in peripheral tissues from the conversion of androstenedione to estradiol via the enzyme aromatase in postmenopausal women.236 The 3 AIs currently in clinical use (anastrozole, letrozole, and exemestane) are third-generation agents characterized by high specificity and suppression of the aromatase enzyme, and their side-effect profiles mostly reflect the effects of estrogen depletion.237 AIs are recommended either as primary therapy or after 2 to 3 years of tamoxifen therapy (total duration, 5 years) in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer, to lower the risk of breast cancer recurrence.222 This recommendation is based on randomized controlled trials that continue to demonstrate reduced cancer recurrence rates and disease-free survival in postmenopausal women treated with AIs compared with tamoxifen.222,238–240 AIs have also been shown to be effective for primary prevention of breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women.241

Because AIs deplete endogenous estrogen production, it has been hypothesized that they might increase the risk of CVD, and most large adjuvant trials that have compared AIs to tamoxifen have included cardiovascular end points. Only a few large studies assessed hypercholesterolemia, and these yielded inconclusive results. The ATAC trial (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination)242 and the BIG (Breast International Group) I-98 trial239 reported a higher incidence of hypercholesterolemia with anastrozole and letrozole, respectively, than with tamoxifen, whereas the MA.17 trial did not find significant differences with letrozole.243 However, a meta-analysis of adjuvant AI trials that accounted for the duration of AI treatment and differences in treatment approach demonstrated that longer duration of AI use was associated with a statistically significant 2.3- fold increase in the OR for hypercholesterolemia compared with tamoxifen.234 The effect was most apparent when upfront AI use was compared with tamoxifen and least evident when switching from tamoxifen to AI was compared with tamoxifen.

In the same meta-analyses of adjuvant trials, a similar pattern of risk for CVD was observed: longer durations of AI use were associated with increased risk for CVD compared with tamoxifen use, with the effect being the strongest in the trials that evaluated upfront AIs versus upfront tamoxifen.234 In a pooled analysis, the OR for development of CVD with the use of AI compared with tamoxifen was 1.26 (CI=1.10–1.43; P<0.001), with an increase in absolute risk of 0.8% (4.2% versus 3.4% risk, respectively). Despite the small absolute risk, the clinical relevance of these findings could be high in specific populations at risk. In the ATAC trial, for example, in women with preexisting heart disease, the incidence of cardiovascular events was 17% in the anastrozole arm compared with 10% in the tamoxifen arm, which led to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) label recommendation that the risks and benefits of anastrozole be considered in this group of patients.244 Various adverse CVD effects have been demonstrated in trials comparing AI with tamoxifen245; however, a randomized controlled trial comparing AI and placebo after 5 years of tamoxifen did not demonstrate any difference in CVD end points in early-stage breast cancer.246

The results of population-based studies that investigated cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women treated with AIs versus tamoxifen have also been mixed,247,248 but large studies have traditionally been limited by a lack of information about cardiovascular risk factors and medications.247 A recent analysis of 13 273 postmenopausal women with endocrine-positive breast cancer in the Kaiser Permanente managed care system showed no association between AI use and risk of ischemia and stroke. Patients receiving AIs had a significantly higher risk of other forms of CVD (dysrhythmia, valvular dysfunction, pericarditis, HF, or cardiomyopathy), the significance of which requires further investigation.249 In a recent meta-analysis of AIs and tamoxifen in the adjuvant and extended adjuvant setting, significant CVD risk reduction was seen in patients treated with tamoxifen compared with placebo or no treatment in the adjuvant setting, and in the extended adjuvant setting, there was not an increased risk with AIs compared with placebo. These data suggest that the increased risk of cardiovascular effects of AIs compared with tamoxifen in randomized controlled trials might be secondary to the cardioprotective effects seen with tamoxifen.250

Ovarian Suppression Therapy

Premenopausal women with stage II or stage III breast cancers who would ordinarily be advised to receive adjuvant chemotherapy should receive ovarian suppression in addition to endocrine therapy.251 In clinical studies, ovarian suppression was associated with a substantial increase in menopausal symptoms, sexual dysfunction, and diminished quality of life compared with tamoxifen alone but not cardiovascular specific side effects, which likely reflects the younger age and overall low cardiovascular risk profile of these patients. Longer follow-up will be needed to assess the effect of early menopause on cardiovascular risk, morbidity, and mortality in these patients.

HER2-Targeted Therapies

Monoclonal Antibodies

Trastuzumab and pertuzumab are the 2 current FDA-approved monoclonal antibodies that inhibit the signaling of HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2). LV dysfunction associated with targeted therapies has been most extensively evaluated in the breast cancer population treated with trastuzumab.252 Trastuzumab binds to the extracellular domain of the ErbB2 (erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2)/HER2 and leads to reduced ErbB2 signaling via several mechanisms. It has been speculated that the cardiac dysfunction associated with trastuzumab is a direct consequence of ErbB2 inhibition in cardiomyocytes.253 In contrast to anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity, trastuzumab exposure can result in LV dysfunction and HF that is mostly reversible.254 At highest risk for cardiotoxicity from trastuzumab exposure are those >50 years of age, patients with underlying heart disease or hypertension, those with baseline LVEF between 50% and 55% or lower, and those who have also received anthracycline therapy (Table 2).183,255 The introduction of adjuvant trastuzumab (with chemotherapy) for patients with HER2-positive early-stage breast cancer has reduced the risk of breast cancer recurrence by 50% and mortality by 33%.256 However, in the 5 major adjuvant trastuzumab trials,257–260 symptomatic, severe HF or cardiac events, with an incidence ranging from 0% to 3.9%, were observed with the addition of trastuzumab to traditional chemotherapy.261–263 Long-term follow-up data (median 8 years) after adjuvant chemotherapy in the international, multicenter, open-label, randomized HERA trial (HERceptin Adjuvant) of 5102 women demonstrated low overall cardiotoxicity, with a greater cumulative incidence of cardiotoxicity (4.1% versus 7.2% with New York Heart Association functional class I or II and significant drop in LVEF ≥10 points with absolute LVEF <50%) and no additional benefit in those treated with 2 years versus 1 year of trastuzumab therapy.259 Population-based studies, particularly in older individuals (women >65 years old), have suggested higher rates of cardiotoxicity. In a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program–based analysis of 9535 women (median age, 71 years) with early-stage breast cancer, of whom 2203 (23.1%) received trastuzumab, the rate of HF was 29.4% compared with 18.9% in nonusers of trastuzumab (P<0.001). Older age (age >80 years; HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.16–2.10), coronary artery disease (HR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.34–2.48), hypertension (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.02–1.50), and weekly trastuzumab administration (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.05–1.68) increased the risk of HF.264

Current clinical trials in early breast cancer are taking advantage of the role of dual HER2 blockade, including the synergistic activity of pertuzumab and trastuzumab. Two neoadjuvant studies (NeoSphere and TRYPHAENA) demonstrated higher pathological complete response rates in women with HER2-positive breast cancer treated with chemotherapy and dual HER2 blockade (pertuzumab, trastuzumab) than in those treated with chemotherapy and trastuzumab therapy alone. In the TRYPHAENA study, the primary end point of cardiac safety was met, with a low incidence of symptomatic and asymptomatic LV systolic dysfunction across all arms.265 To date, there have not been any additional cardiac safety concerns when those agents were combined.266,267 In a recently published large, prospective, randomized trial (APHINITY trial) exploring trastuzumab with or without pertuzumab with adjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of women with early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer, there was a low incidence of HF (0.7% in the pertuzumab group versus 0.3% in the placebo group, with HF defined as New York Heart Association functional class III or IV and a significant drop in LVEF ≥10 points with absolute LVEF <50%) and cardiac death (2 cardiac deaths in each arm).268

Small-Molecule Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

An alternative approach to inhibit HER2-mediated signaling is the use of small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors that target the HER2 intracellular kinase domain. Lapatinib is a reversible small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor that is frequently administered in combination with capecitabine or with endocrine therapy and is approved for the treatment of women with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer.269,270 A phase III trial comparing lapatinib monotherapy versus combination therapy with trastuzumab demonstrated a 4.5-month survival advantage with combination therapy but also reported a higher incidence of serious adverse cardiac events of systolic dysfunction with combination therapy (6.7% versus 2%).271 Subsequently, the ALTTO trial (Adjuvant Lapatinib and/or Trastuzumab Treatment Optimization) of 8381 women with early-stage breast cancer demonstrated no significant improvement in disease-free survival with adjuvant treatment that included lapatinib compared with trastuzumab monotherapy. Those treated with lapatinib experienced more noncardiac side effects (diarrhea, cutaneous rash, and hepatic toxicity); however, in all treatment arms, the incidence of cardiotoxicity was low (2%–3% for HF, 2%–5% for any cardiac event).272

Emerging Therapies

Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitors are being developed to overcome endocrine resistance based on cross talk between ER pathways. CDK 4/6 is a group of serine/threonine kinases that accomplish their action by forming a complex with cyclin D. In turn, this complex phosphorylates the retinoblastoma protein and deactivates it, which results in gene transcription and progression of cell replication in the transition between the G1 and S process.273–275 In cancer, CDK 4/6 are upregulated and participate in tumor growth by blocking tumor suppression and apoptosis. Blocking the formation of CDK 4/6 cyclin D complex causes cell cycle arrest.276,277

The CDK 4/6 inhibitors that have been evaluated in the treatment of women with metastatic breast cancer are palbociclib, ribociclib (both approved by the FDA), and abemaciclib (pending approval by the FDA). All of these agents have been tested in phase II and III clinical trials and are administered in combination with endocrine therapy (eg, AI, fulvestrant). The clinical benefit of CDK 4/6 inhibitors in the treatment of women with metastatic breast cancer is beyond the scope of this review. The most common adverse events reported with these agents are bone marrow suppression (neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia), fatigue, vomiting, and diarrhea.277,278 Ribociclib is the only oral CDK 4/6 inhibitor for which there are cardiovascular concerns: prolongation of the corrected QT interval was seen in ≈9% of patients at doses of 600 mg/d (current approved dose in clinical practice) and in ≈33% at doses of >600 mg/d.279,280 This has led to the product label stipulating that ribociclib should be initiated only when the corrected QT interval is <450 ms and that electrocardiograms must be performed at baseline, on day 14, before starting cycle 2 (day 28), and then as clinically indicated.281 Healthcare professionals and patients should be educated about the importance of avoiding concomitant use of other drugs that could further prolong the QT interval.

Radiation Therapy

The biological mechanisms of RT cardiotoxicity remain incompletely understood but are most likely secondary to alterations in multiple pathways, including myocyte ischemia/injury, inflammation, fibrosis, oxidative stress, and microvascular dysfunction. Animal models of RT cardiotoxicity indicate that an inflammatory response is elicited within cardiac and endothelial cells, with increased adhesion molecule and cytokine activity.282 RT also results in increased reactive oxygen species in cardiac tissues.283 In the rodent heart, radiation causes microvascular endothelial damage, which leads to lymphocyte adhesion and extravasation. This is followed by thrombus formation and capillary loss. Progressive reduction in capillary patency eventually results in ischemia, myocardial cell death, and fibrosis. In vitro and in vivo studies demonstrate that RT has significant effects on the macrovasculature and microvasculature, causing myocardial ischemia and injury.284 In large blood vessels, such as the coronary and carotid arteries, RT causes inflammation and oxidative damage, which, in the presence of high cholesterol, leads to lipid peroxidation and the formation of foam cells that initiate the atherosclerotic process. RT results in accelerated atherosclerosis, with thickened and fibrotic media/adventitia.285 Myocyte fibrosis is a consequence of ischemia and has been observed in cardiac histopathological studies in animals with RT.285 Intriguing, emerging data suggest a cardioprotective role for mast cells in cardiac RT injury, through the kallikrein-kinin pathway.286–288

Thoracic RT carries a significant risk of CVD toxicity that results in increased morbidity and mortality, which limits the critical gains in cancer control and survival.289–291 Cardiovascular effects secondary to coronary atherosclerosis and accelerated endothelial injury can occur as early as 5 years after exposure among breast cancer survivors who receive left-sided thoracic RT, and persistence of risk remains for up to 30 years.292 In addition to macrovascular disease, patients can also develop microvascular dysfunction that results clinically in impaired coronary flow reserve, myocardial ischemia, and myocardial fibrosis.292 A recent population-based case-control study demonstrated an increased risk in HF with preserved ejection fraction among women treated with contemporary breast cancer RT, which correlated with mean cardiac radiation dose.293 RT also increases the risk of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity.294 Acute and chronic pericarditis, valvular regurgitation and stenosis, and conduction abnormalities and sudden death are also well described, especially with chest radiation doses >30 Gy.295 Autonomic dysfunction is an underreported cardiovascular effect of RT that has an increased prevalence with higher radiation doses, and the associated impaired heart rate recovery significantly affects all-cause mortality.296

In a study of 2168 women with breast cancer, each 1-Gy increase in mean heart radiation dose was associated with a 7.4% increase in coronary events.5 In a meta-analysis by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group of >23 000 women, there was an excess of non–breast cancer deaths after 5 years among patients receiving RT, principally attributable to CVD and lung cancer.297 Multiple epidemiological studies support these results.6,298,299 Mortality ratios defined by laterality of breast cancer in 558 871 women from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program suggest that left-sided breast cancer patients treated with RT have a 1.19 to 1.90 increased risk of CVD mortality compared with those with right-sided breast cancer.299 Although some studies suggest that the CVD risks might be decreasing over time given improvements in treatment techniques, there is an important need for long-term data, particularly in the era of proton therapy.6 However, even with the use of modern techniques, including computed tomography planning and deep inspiration breath hold, incidental irradiation to smaller volumes of the heart results in cardiac perfusion defects.300–302

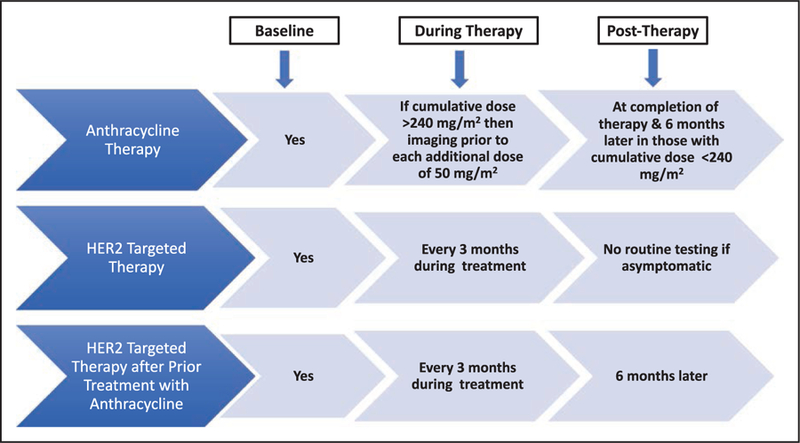

MONITORING FOR CARDIOVASCULAR TOXICITY

Early Identification of Risk

LVEF obtained by echocardiography, multigated acquisition scan, or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to identify patients with cardiotoxicity; however, a change in LVEF could constitute a late manifestation of myocardial damage and might represent irreversible cardiac damage, thus emphasizing the need to predict cardiac damage before its occurrence. In addition, the limited accuracy and variability of 2-dimensional echocardiography (on the order of 10% in non–core laboratory quantitation settings) for LVEF assessment,303 coupled with a lack of consensus of what constitutes a clinically significant reduction in cardiac function, suggest a critical need for a consensus for diagnostic and prognostic strategies. The variability in LVEF assessment can be of the same magnitude used to define cardiotoxicity in some settings. Furthermore, serial LVEF monitoring, although accepted, has never been validated in terms of outcomes. It is noteworthy that the sensitivity of 2-dimensional echocardiography for detection of small changes in LV function is low and is affected by changes in loading conditions associated with chemotherapy, which can then affect the LVEF value. As such, the development of strategies for early detection of cardiotoxicity has been the focus of more recent research efforts. In the clinical setting, these strategies thus far have fallen largely into 3 main categories: myocardial strain imaging, cardiac biomarkers, or a combination of imaging and biomarkers.

Myocardial Strain Imaging for Risk Identification

Speckle-tracking echocardiography for detection of LV myocardial strain is a newer cardiac imaging technique. It measures LV regional and global deformation in response to force as a marker of contractility and elasticity. Change in LV strain measures precedes change in LVEF,304 and strain has been shown to be a predictor of cardiac dysfunction in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy.305

One study showed that an absolute longitudinal strain value of ≤17.2% obtained 6 months after anthracycline (doxorubicin or epirubicin) therapy was predictive of abnormal longitudinal strain at 1-year follow-up, with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 80%.306 Strain alterations were associated with higher doses of anthracyclines, although within the dose range considered to have an acceptable toxicity profile. Global longitudinal strain has also been shown to be an early predictor of subsequent LV systolic dysfunction in patients treated with trastuzumab.307 Studies by others have also demonstrated that longitudinal and circumferential strain have diagnostic and prognostic relevance in female breast cancer patients undergoing treatment with doxorubicin or trastuzumab.308

Myocardial strain has excellent interobserver and intraobserver variability compared with other cardiac imaging modalities309 and is highly correlated with the relatively expensive and much less available cardiac MRI in the assessment of LV dysfunction.310 In addition, strain imaging as obtained with echocardiography is less expensive and less time consuming, does not confer radiation risk to the patient, and is not nephrotoxic compared with other cardiac imaging modalities for LVEF assessment; however, echocardiography image acquisition can be significantly limited in the setting of obesity and lung disease.

Biomarkers as Risk Markers of Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiac Disease

The role of biomarkers in this setting lies in the prediction of cardiomyopathy or detection of subclinical cardiomyopathy. Studies have evaluated the role of cardiac biomarkers, particularly brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and troponin I, which accurately reflect myocardial injury, in the evaluation of cardiotoxicity associated with breast cancer therapy.311,312

Troponin I

Troponin I is a well-established, highly sensitive and specific marker of myocardial injury with a wide diagnostic window and is a robust chemical assay.313 A rise in troponin-I within ≈3 days of high-dose chemotherapy has been shown to predict a reduction in LVEF.314 Troponin I has an excellent negative predictive value for not developing cardiotoxicity during and immediately after treatment. Additional studies have shown similar findings, with a negative predictive value of 90% for ruling out the possibility of doxorubicin-induced systolic dysfunction with troponin I.305 Troponin I has also been successful in differentiating reversible and irreversible LV dysfunction associated with trastuzumab,315 as well as in the identification of cardiovascular outcomes (defined as death resulting from a cardiac cause, acute pulmonary edema, overt HF, asymptomatic LVEF reduction [≥25% from baseline], or life-threatening arrhythmias) in patients receiving various types and combinations of high-dose chemotherapy. In contrast, it has also been demonstrated that troponin I increases were common in breast cancer patients receiving both trastuzumab and lapatinib but were not associated with subsequent LV dysfunction according to multigated acquisition scans.316

Natriuretic Peptides