Three Rivers Stadium (Pittsburgh) – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

Three Rivers Stadium; if it wasn’t the most picturesque coliseum in American sports history, it was perhaps one of the most perfectly named.

In southwestern Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh, the county seat of Allegheny County, lies partly in a hilly region known as the Golden Triangle, the location of the city’s business district. For those unfamiliar with the region, one look at a map and it’s immediately apparent where the area derives its name from. Flowing diagonally from northeast of the city to southwest is the Allegheny River. Meandering gracefully from the southeast to the northwest is the Monongahela River. At the confluence of those two waterways, the point of the triangle, is formed the Ohio River; and it’s there, where the three rivers converge, across the Allegheny River from the Golden Triangle, on the riverbank known as the north shore, that Pittsburgh’s sports fans gathered for 31 years at Three Rivers Stadium to watch their favorite baseball team, the Pirates.

It is a riverbank steeped in local lore. During the region’s formative years, as the French and British vied for supremacy amid the native American Indians (Three Rivers Stadium was built on a Delaware Indian burial ground), each nation erected enclosures for protection, Fort Duquesne by the French; and Fort Pitt by the British. As those two world powers battled for local sovereignty, George Washington engaged in several military campaigns on the north shore, attempting to take possession of Fort Duquesne.

Three Rivers Stadium wasn’t the first ballpark to occupy the shoreline; in fact, it was merely the latest in a line of stadiums which had once stood upon the same site. In 1882 the Alleghenys,1 a founding member of the American Association, began play on the north shore at Exposition Park, in what would be the first incarnation of a structure known by that name. Exposition Park I remained intact for just one season. By opening day of 1883, flooding along the shore had forced hasty construction of a second version of Exposition Park, in roughly the same location, but on higher yet overlapping ground. The Alleghenys took up residence in that ballpark too, but for only a single season, as for the next six years the team called nearby Recreation Park its home. It was only a matter of time, however, before they once again occupied the Exposition Park grounds.

The year 1887 brought to the region a change in the baseball landscape. That season the Alleghenys not only joined the National League, but they also adopted as their identity the city across the river. For the first time, the team playing at Recreation Park was known not just as the Alleghenys, but as the Pittsburgh Alleghenys. If they were rarely very good on the field, at least they were major league.

If the lineage of today’s Pittsburgh Pirates2 can be traced to that first Alleghenys team playing at the first Exposition Park on the north shore, then Opening Day 1891 marks the date when all of the attributes of one of baseball’s most historic franchises were finally in place. On April 22, 1891, the Pittsburgh Pirates lost their season’s opener, 7-6, to the Chicago Colts, at the Pirates brand-new stadium, again named Exposition Park (III). It was the third and ultimately final version, which stood atop the previous two incarnations. It was to remain the team’s home for the next 18 seasons. That span, though, was dwarfed by the Pirates’ stay at their next ballpark. To get there, the team left the north shore and moved across the river to the heart of the Golden Triangle.

Little need be said about Forbes Field; much has been written about one of the legendary ballparks in baseball history. Besides, this essay is about Three Rivers Stadium, not Forbes Field. Suffice it to say that once the Pirates moved into their new state-of-the-art, concrete and steel coliseum in June 1909, they stayed in that ballpark in the Oakland neighborhood of Pittsburgh for the next 61 years, and won three World Series. By the 1950s, however, with the Forbes Field infrastructure beginning to crumble and the ballpark showing its age, a search was on for a new facility that would propel the Pirates into the modern era. Once again, attention turned back to the north shore.

Revitalization

Over the several generations that the Pirates called Forbes Field their home, the riverfront where once had stood the three versions of Exposition Park had become a sprawling industrial area, which by the early 1950s was severely in need of an architectural makeover. With the concurrent aging of Forbes Field, the need was acute for a new ballpark that could house not only the Pirates, but also the city’s football team, the Steelers. Planning for a multipurpose municipal ballpark had begun as early as 1948, when the first proposal was submitted to the city; but it wasn’t until the ’50s that substantive efforts to address the ballpark issue took shape. It was then that the city decided to revitalize the north shore. Baseball, it was determined, would return to the riverfront, at the site where it had all begun, the site where the three rivers met.

Officially, that site for what was initially to be called Pittsburgh Stadium was chosen in 1958.3 Completion was estimated for some time in the early 1960s. Once built, the plan was for the ballpark to be the crown jewel in a complex that would include hotels, restaurants, and a riverfront park. In original conception the ballpark was to be round, with an open end facing south, toward the skyline of downtown Pittsburgh. Some designs, however, envisioned a bit more extravagance. Rather than a ballpark that would stand on the waterfront, one particularly grandiose design proposed a “Stadium Over the Monongahela” that would be built completely over the water.4 In that, a massive span would replace the existing Smithfield Street Bridge, and the ballpark would be built atop the span, with two parking lots below. The entire structure would stand above the river, “with plenty of room for boats to pass beneath.”5 The prohibitive cost alone of such a project probably ensured that such a proposal was never even considered.

With the ballpark’s location chosen, it took five years before work got under way to clear the land for eventual construction. That began in 1963. However, political squabbles and labor disputes further delayed the project. One key milestone, though, eventually served as the catalyst to begin building the ballpark, In 1958, work had begun on the Fort Duquesne Bridge, which would span the Allegheny River and connect the downtown with the north shore. The bridge’s main span was completed in 1963, yet, due to “red tape and governmental disagreement,”6 overall completion languished for several more years, during which time the project became known as the “Bridge to Nowhere.”7 (The roadway ended 90 feet short of the shoreline.) In 1968, however, the last piece was finally put in place, and the bridge was completed. Accordingly, on April 25, 1968, ground was broken on the long-delayed Pittsburgh Stadium. After a decade of waiting, construction of the Pirates’ new home was begun.

Three Rivers Stadium

Construction was scheduled to take two years; if all went according to plan, it would be ready for the start of the 1970 season. All didn’t go according to plan, however. On Opening Day, April 7, 1970, the Pirates lost to the New York Mets, 5-3, at Forbes Field. Soon, a revised completion date of May 29 was reported, but that, too, proved inaccurate, as the lights had yet to be put into place. Meanwhile, on June 28, the Pirates hosted the Chicago Cubs for a doubleheader at Forbes Field.8 The next day the Pirates were to embark on a 14-game road trip. Hopes were high throughout Pittsburgh that the Pirates’ next homestand would take place in their shiny new arena.

So it did. It hadn’t always been apparent, though, what name would be given to that new arena. While it had taken more than the projected two years to build the new ballpark, it took nearly as long to reach consensus on a new name. After much deliberation, the agreed-upon name was the uniquely descriptive Three Rivers Stadium.9 It was as apropos of its time as it was of its location.

The decades of the 1960s and ’70s became the era of the multipurpose stadium. In addition to Pittsburgh’s quest to provide a single home for both its baseball and football teams, similar stadiums with comparable intent had also recently been constructed in Washington, New York (Queens), Houston, Atlanta, St. Louis, and Cincinnati, with Philadelphia forthcoming. Architecturally there was little to tell one of these stadiums apart from another: They were round, multi-tiered, symmetrical structures designed to accommodate the playing fields of two entirely different sports with entirely different dimensions. By design, such requirements left little room for creativity. In identity, these stadiums came to be called “cookie cutter.”

Sitting almost exactly on the site of Exposition Park, Three Rivers Stadium never fulfilled the elaborate plans for the north shore that had been imagined back in 1958. The adjoining hotels and shops were never built; nor was the beatific open end of the ballpark with its proposed magnificent view of the Pittsburgh skyline. Instead, cost constraints dictated that the city got what it paid for: At a cost of 55million,thearchitecturaltriumvirateofDeeter,Ritchey,Sippel;MichaelBakerJr.;andOsbornEngineeringprovidedafunctional,multipurposestadiumthatseated47,971fansforbaseballand59,000forfootball.Aroundacircularbowl,fivetiersofredandyellowseatsenclosedthestadium.(Overtheyears,numberswerepaintedontheright−fieldseatstodesignatewhereWillieStargell’shomerunslanded.)ConvertingthestadiumfortheSteelers’occupancyinthefallincludedmovingtwobanksof4,000seatsalongthefirstandthirdbaselinestobecome8,000seatsonthe50−yardline.Themainscoreboardwaslocatedovertheoutfieldfenceincenterfield;thiswasreplacedin1984bya55 million, the architectural triumvirate of Deeter, Ritchey, Sippel; Michael Baker Jr.; and Osborn Engineering provided a functional, multipurpose stadium that seated 47,971 fans for baseball and 59,000 for football. Around a circular bowl, five tiers of red and yellow seats enclosed the stadium. (Over the years, numbers were painted on the right-field seats to designate where Willie Stargell’s home runs landed.) Converting the stadium for the Steelers’ occupancy in the fall included moving two banks of 4,000 seats along the first and third base lines to become 8,000 seats on the 50-yard line. The main scoreboard was located over the outfield fence in center field; this was replaced in 1984 by a 55million,thearchitecturaltriumvirateofDeeter,Ritchey,Sippel;MichaelBakerJr.;andOsbornEngineeringprovidedafunctional,multipurposestadiumthatseated47,971fansforbaseballand59,000forfootball.Aroundacircularbowl,fivetiersofredandyellowseatsenclosedthestadium.(Overtheyears,numberswerepaintedontheright−fieldseatstodesignatewhereWillieStargell’shomerunslanded.)ConvertingthestadiumfortheSteelers’occupancyinthefallincludedmovingtwobanksof4,000seatsalongthefirstandthirdbaselinestobecome8,000seatsonthe50−yardline.Themainscoreboardwaslocatedovertheoutfieldfenceincenterfield;thiswasreplacedin1984bya5 million video scoreboard placed below the stadium’s rim in center field. For Pirates fans, it was to be an antiseptic, manufactured environment, far removed from the cozy confines of beloved Forbes Field, right down to the artificial, plastic Tartan Turf upon which the modern game of baseball was to be played. (In 1983 the original Tartan Turf was replaced by Astroturf.)

Three Rivers Stadium was not without its elegance, though. High atop the stadium, providing a birds-eye view of the field, was the luxurious Allegheny Club, a restaurant that accommodated 300 people for the field view and 400 in the main dining area. In an effort to maintain the team’s link to its past, moved from Forbes Field and displayed in the restaurant were an 8-by-12-foot section of the old ballpark’s left-field brick wall (on which the 406-foot marker had been visible), over which Bill Mazeroski hit his Game Seven World Series-winning home run in 1960; a plaque showing where Babe Ruth’s 714th home run had landed in Forbes Field; and 12 Romanesque window frames from the Pirates’ iconic former home. Additionally, an 18-foot, 1,800-pound statue of Pirates legend Honus Wagner that had stood behind the left-field wall at Forbes Field was moved outside the new stadium, to be joined in 1994 by another in honor of Roberto Clemente. All ensured that as the Pirates moved into the future, their past would never be forgotten.

On the Field

In the 31 years that Three Rivers Stadium stood on the north shore, the Pirates won two World Series and witnessed several historic accomplishments by some of baseball’s most legendary players. Following are some of the stadium’s most memorable events.

July 16, 1970: The first game

After their doubleheader sweep of the Cubs at Forbes Field, the Pirates’ road trip had been a tremendous success, as they posted a 10-4 record. Returning home for the opener at Three Rivers Stadium, they held first place in the National League East, 1½ games ahead of the New York Mets. The Pirates’ opponents on this clear evening were the West Division-leading Cincinnati Reds, winners of three in a row.

A crowd of 48,846, the largest ever to attend a baseball game in Pittsburgh, was on hand to witness the festivities. Among the VIPs in attendance were Pittsburgh Mayor Peter Flaherty and Pirates part-owner and vice president Bing Crosby. Bandleader and singer Billy Eckstine, a Pittsburgh native, sang the National Anthem, and Pirates Hall of Famer Pie Traynor threw out the first pitch.

The conditions were perfect for Three Rivers’ inaugural game. Although the day had begun with cloudy skies and light rain, by afternoon the skies had brightened and at game time a full moon bathed the stadium. In the bottom of the first inning, Richie Hebner got the first hit, an infield single, and he scored the first run on Al Oliver’s double. Pittsburgh starter Dock Ellis protected the lead until the top of the fifth, when the Reds’ Tony Perez blasted the stadium’s first home run, his 30th, a two-run shot, to put Cincinnati in front. The Pirates’ Willie Stargell evened the score in the bottom of the sixth with a solo homer, but in the top of the ninth, the Reds’ Lee May singled home Perez from second base to give Cincinnati a 3-2 victory, the only blemish on an otherwise perfect evening.10

August 14, 1971: The first Three Rivers Stadium no-hitter

It had been a long time since fans had witnessed a no-hitter in Pittsburgh. On September 20, 1907, at Exposition Park, Pirates right-hander Nick Maddox, in the midst of a fabulous rookie season, tossed what until the night of August 14, 1971, was Pittsburgh’s only no-hitter when he beat the Brooklyn Superbas, 2-1. During the 61 years that baseball was played at Forbes Field, no pitcher had ever thrown a hitless gem. On this night, however, one of the greatest hurlers in baseball history threw his only no-hit game.

Over the course of a career that would eventually earn his enshrinement in the baseball Hall of Fame, Cardinals hurler Bob Gibson had twice thrown one-hitters. Until this night, though, he had never thrown a no-hitter. Ten days before, against the Giants in San Francisco, Gibson had won his 200th game in a gutsy complete-game, seven-hit performance. On this Saturday night, he was demonstrably better, even dominant. Until the seventh inning the Pirates never came close to recording a hit. Then in the seventh, with one out, Milt May blasted a drive deep toward the 390-foot mark in left-center field. Running full speed, the Cardinals’ José Cruz, losing his hat in the process, chased down the ball and caught it on the warning track. That was the Pirates’ lone threat as Willie Stargell was called out on strikes to end the game. Gibson allowed just four baserunners while fanning 10 as he throttled the Pirates, 11-0.

October 13, 1971: The first World Series night game

In their second season playing at Three Rivers Stadium, the Pirates played for baseball’s championship. There had been 67 previous World Series, and all had one thing in common: Every game had been played during the day. That changed on the evening of October 13, 1971. After opening the Series in Baltimore, where the Pirates dropped two daytime games to the Orioles, the Series moved to Pittsburgh for the next three games. On Tuesday afternoon, October 12, the Pirates, behind a three-run homer from Bob Robertson and a stellar complete-game three-hitter by Steve Blass, downed the Orioles 5-1. On Wednesday evening, the two teams met in Game Four for the first night game in World Series history.

It couldn’t have started worse for Pittsburgh. Against the Pirates’ left-handed starter, Luke Walker, in the top of the first inning the Orioles’ first three batters singled; then a passed ball by Pirates catcher Manny Sanguillen allowed the first run. After an intentional walk to Orioles slugger Frank Robinson, Walker gave up consecutive sacrifice flies, and six batters into the game, Baltimore led 3-0. But they’d not score again in this contest.

With the Orioles’ Davey Johnson due up, Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh summoned from the bullpen 21-year-old rookie right-hander Bruce Kison, who, over the next 6⅓ innings allowed just one hit and no runs. (He hit three batters.) By the third inning the Pirates had tied the game, 3-3, and in the seventh, pinch-hitting for Kison, Milt May singled home the eventual winning run, to tie the Series at two games apiece.

After surprise starter Nelson Briles fired a two-hit shutout against the Orioles the next afternoon, again at Three Rivers Stadium, the Series returned to Baltimore and went to a seventh game. Finally, on Sunday afternoon, October 17, the Pirates defeated the Orioles 2-1, and won the franchise’s fourth world championship.

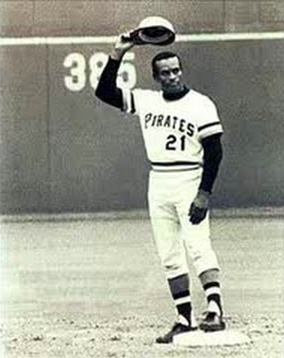

September 30, 1972: Roberto Clemente’s 3,000th hit

To those readers who were born in the 1960s and came of age in the ’70s, it’s perhaps natural to associate Roberto Clemente’s career with Three Rivers Stadium. In actuality, though, Clemente spent just 2½ of his 18 seasons playing on the north shore; moreover, due to injuries, he played a total of just 136 games at Three Rivers before his untimely death on December 31, 1972. In light of Clemente’s tragic loss, one of those games provided one of baseball’s most singular and poignant moments.

To those readers who were born in the 1960s and came of age in the ’70s, it’s perhaps natural to associate Roberto Clemente’s career with Three Rivers Stadium. In actuality, though, Clemente spent just 2½ of his 18 seasons playing on the north shore; moreover, due to injuries, he played a total of just 136 games at Three Rivers before his untimely death on December 31, 1972. In light of Clemente’s tragic loss, one of those games provided one of baseball’s most singular and poignant moments.

At the conclusion of the 1971 season, in which he had produced his third consecutive .340-plus batting average, Clemente had amassed 2,882 hits, leaving him just 118 shy of joining the rarefied 3,000-hit club. With injuries limiting the superstar to playing just 102 games in 1972, on Thursday night, September 28, in Philadelphia he collected hit number 2,999, a leadoff single to right field in the fourth inning, then asked to be removed for a pinch-hitter in the sixth inning. Clemente wanted to get his 3,000th hit before the home fans.

On Friday night, September 29, at Three Rivers Stadium, the Mets’ Tom Seaver shut out the Pirates on two hits. Clemente went 0-for-4. The next afternoon, with only 13,117 fans in attendance, the Pirates faced Mets left-hander Jon Matlack. In his first at-bat against Matlack, Clemente struck out. Then, leading off the Pirates’ fourth inning, Clemente lashed a double to the wall in left-center field for his 3,000th hit, just the 11th man at that point to join the exclusive fraternity. The crowd arose as one and provided Clemente a heartfelt standing ovation. Perched on second base, Clemente doffed his cap and soaked in the adulation. Umpire Doug Harvey handed Clemente the ball from the historic hit. Finally, an inning later, the Mets’ Willie Mays, a fellow member of the 3,000-hit club, visited Clemente in the Pirates dugout and offered his congratulations.

As the Pirates removed Clemente from the starting lineup of the team’s final three games in preparation for the playoffs, the double became Clemente’s final regular-season hit.

July 23, 1974: Three Rivers’ first All-Star Game

In 1974 the All-Star Game came to Pittsburgh. Only twice before had the city hosted baseball’s annual event; the first time was July 11, 1944, with the National League victorious by a 7-1 score. The classic also came in 1959, when two All-Star games were played, and Forbes Field hosted the first. The National League won that day, July 7, 5-4.

On this night in 1974 a sellout crowd of 50,706 was on hand. After Pirates owner John Galbreath threw out the first pitch, the National League, which had won 10 of the previous 11 contests, again got the better of the American League, winning 7-2. For the Nationals, the Cardinals’ Reggie Smith hit a solo home run, the Dodgers’ Steve Garvey was named the game’s MVP, and reliever Ken Brett, the Pirates’ lone representative, was the winning pitcher.

It was the third win in a row for the National League, and advanced the circuit’s record in All-Star Games to 26-18-1.

August 9, 1976: The first no-hitter by a Pirate at Three Rivers Stadium

It couldn’t have been a more perfect giveaway. On August 9, 1976, in recognition of the Pirates’ newest star, 6-foot, 7-inch, 22-year-old left-handed pitcher John Candelaria, whose nickname was, naturally, Candyman, the team gave away candy bars to all 9,860 attendees that night. Indeed, they were in for a treat.

A Pirate hadn’t pitched a no-hitter since Dock Ellis, at San Diego, in 1970. Bob Gibson, the future Hall of Famer who’d thrown the first no-hitter at Three Rivers, was in attendance as part of ABC’s Monday Night Baseball TV broadcast team. This night the Pirates faced the Los Angeles Dodgers. The Dodgers were in for a quick but futile evening, as Candelaria was totally dominant. In the third inning, by virtue of two errors and a walk, Los Angeles loaded the bases with two outs, but Candelaria escaped harm when he got Bill Russell to ground out. Other than that, offered Candelaria afterward, “It was (Ted) Sizemore’s line drive to (Frank) Taveras in the sixth inning. A foot either way and it’s a base hit.”11

In the end Candelaria retired the Dodgers in order in every inning except that dicey third, and struck out seven. Although he claimed later that “I knew I had it from the first inning,” still, against Russell with two outs in the ninth, “I thought Russell’s fly [to shallow center field] was gonna drop in at first. I thought ‘what a way to lose it.’”12 However, center fielder Al Oliver raced in and caught the ball one-handed, brushing against shortstop Taveras, and the no-hitter was preserved.

In the locker room after the game, the players laid towels from the door of the clubhouse to Candelaria’s locker. On the towels were candy bars. As the team celebrated, Oliver presented Candelaria with the game ball.

October 14, 1979: Pirates win World Series Game Five to save the Series

There couldn’t have been much optimism in Pittsburgh the afternoon of October 14, 1979 … other than, perhaps, among Pirates manager Chuck Tanner, starting pitcher Jim Rooker, and Rooker’s teammates. With the Pirates in the World Series against the Baltimore Orioles, in a rematch of their 1971 encounter, the Orioles had taken a three-games-to-one lead, and had only to win Game Five to avenge their 1971 loss. For Baltimore, 23-game winner Mike Flanagan, the eventual American League Cy Young Award winner, would take the mound. Opposing him was Rooker, a 37-year-old left-hander whose fastball rarely touched 90 mph and who had won all of four games during the regular season. Of such matchups, however, are Series victories often made.

With Rooker’s aged arm rarely able to get batters out with speed, “The book on Rooker is that he’s a breaking ball pitcher,” explained his catcher, Steve Nicosia, after the Pirates had defeated the Orioles, 7-1, behind five strong innings by Rooker. “He doesn’t usually throw the ball by guys. He spots his fastball. Today they were looking for offspeed stuff and he was busting the fastball. The next thing you know they were 0-2. … That was the best fastball he’s had all year.”13

Indeed, as the Orioles flailed at inside fastballs, Rooker allowed just three hits in his five innings. In the bottom of the fifth, with Baltimore ahead 1-0, Rooker was lifted for a pinch-hitter. As the Pirates scored seven runs over the next three innings, right-hander Bert Blyleven shut out the Orioles over the next four innings to preserve Rooker’s performance, and the Pirates went on to win and extend the Series. When they returned to Baltimore and took the next two games, Pittsburgh rejoiced in the Pirates’ second world championship of the decade.

September 27, 1992: Pirates defeat Mets to win third consecutive division title

Since the beginning of divisional play in 1969, only two National League teams had won three consecutive division titles: the Pirates in 1970-72, and the Philadelphia Phillies in 1976-78. Now, having won division titles in both 1990 and ’91, the Pirates sought to be the first team to twice win three in a row.

If excitement was in the air for the Pirates, it was most likely a muted enthusiasm. In the previous two years the team had celebrated divisional titles only to lose in the NLCS, to the eventual World Series champion Reds in 1990, and to the Atlanta Braves in 1991. Still, 1992 was a new year, with new opportunities for victory, and as the Pirates took the field against the New York Mets, they were determined to once again clinch the National League East crown.

On this Sunday afternoon at Three Rivers Stadium, few pitchers were better prepared mentally to take the mound in a pressure situation than was veteran left-handed starter Danny Jackson, who had won World Series titles with the Kansas City Royals in 1985 and the Cincinnati Reds in 1990. So it was that Jackson threw seven-plus strong innings, allowing New York just six hits and one run, and the Pirates clinched the title with a 4-2 win. This time, though, there was little celebration in the clubhouse, for the team knew how much work remained; and alas, for the third consecutive season, the Pirates were beaten in the NLCS, once again by the Braves.

It would be 21 years before Pittsburgh celebrated another trip to postseason action.

The Final Game

By the 2000 season the Pirates had largely fallen into disrepair, much as had Three Rivers Stadium; and as the team on the field ceased to be competitive, the fans stayed away. In 1994, the ballpark hosted its second All-Star Game, for which new blue seats were added in the lower deck. However, by the mid-1990s many upper-deck seats were routinely covered by huge canvas tarpaulins that bore Pittsburgh’s championship logos. (In a summary of the Pirates final game at Three Rivers, it would later be written that the ballpark had “lost favor because it had poor sight lines, lacked swanky luxury boxes and had tens of thousands of empty seats for many baseball games.”14) Eventually, as both the Pirates and Steelers sought ways to generate extra revenue, it was determined that separate stadiums would be built on each side of Three Rivers Stadium, the new facilities to be named Heinz Field (for the Steelers) and PNC Park (for the Pirates). They were to be ready for occupancy by their respective 2001 seasons.

On October 1, 2000, the Pirates played their final game at Three Rivers Stadium. They went into the game with a record of 69-92, which placed them fifth of six teams in the National League’s Central Division. Their opponents were the Chicago Cubs, who stood five games behind the Pirates, in last place.

For the record, the Pirates lost that day to the Cubs, 10-9, coincidentally the same score by which Bill Mazeroski’s home run had won the World Series for the Pirates at Forbes Field in 1960. Before 55,351 fans (ironically a Three Rivers record for baseball attendance), the Pirates’ John Wehner, a Pittsburgh native who as a boy had attended Pirates games at the ballpark, hit his fourth and last career home run, the final home run to go over the wall at Three Rivers Stadium. For his fifth-inning two-run blast, the fans gave him a standing ovation.

Much of that applause was undoubtedly in recognition of the ending of an era.

The Ending

February 11, 2001, was a frigid morning in Pittsburgh, with the temperature in the teens. Despite the cold, thousands of people from all over the Golden Triangle gathered to witness the demolition of Three Rivers Stadium. The previous week, explosives experts from Controlled Demolition Inc., which had charge of the implosion, had packed the stadium with 4,800 pounds of dynamite that would level the iconic arena. Earlier, the Carnegie Science Center had held a raffle to select the person who would win the honor of pushing the button that would detonate the charge. A stadium employee named Elizabeth King won the raffle, and at 7:58 A.M., she and her 16-year-old son, Joseph, pushed the button. Within seconds the western wall collapsed into a cloud of dust, and in 19 seconds Three Rivers Stadium had been reduced to an 8,000-ton pile of concrete and scrap metal. Beneath the rubble lay nearly 31 years of Pittsburgh’s sports memories.15

Today the spot where Three Rivers Stadium stood is commemorated by a Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission marker, placed there on November 26, 2007, at Art Rooney Avenue, near North Shore Drive. (The locations of Forbes Field and Exposition Park are also commemorated with historical markers.) Only the stadium’s Gate D marker remains as a memorial to the history that was created along the bank of the Allegheny River, near the site where the three rivers meet.

This article appears in “When Pops Led the Family: The 1979 Pitttsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Gregory H. Wolf.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the following**:**

Mulligan, Stephen. Were You There? Over 300 Wonderful, Weird and Wacky Moments from Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium (Pittsburgh: RoseDog Books, 2013), 51.

popularpittsburgh.com/baseballhistory/.

ballparksofbaseball.com/past/ThreeRiversStadium.htm.

ballparks.com/baseball/national/3river.htm.

3riversstadium.com/about/history.html.

pittsburghsteelers.co.uk/steelers/trs/three%20rivers%20page1.htm.

pahighways.com/features/threeriversstadium.html.

Notes

1 Before 1907, when Pittsburgh annexed the region, the area that included the north shore was a separate city known as Allegheny City. For the first five years of the team’s existence, the Alleghenys were known simply by that name. It wasn’t until the team joined the National League that it became known as the Pittsburgh Alleghenys.

2 As to the team’s new nickname, after a convoluted series of maneuvers involving the Alleghenys, the Burghers, a team in the newly formed Players League, and both the American Association and National League, the Alleghenys were accused by the American Association’s Philadelphia Athletics of “pirating” one of their players; hence, the Pittsburgh team changed their name to the Pirates.

4 Phillip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Walker Publishing Co. 2006), 192.

5 Ibid.

6 http://newsinteractive.post-gazette.com/thedigs/2013/07/24/pittsburghs-bridge-to-nowhere/.

7 Ibid.

8 Sixty-one years earlier, the Cubs had been the Pirates’ opponent the day Forbes Field opened, June 30, 1909, so it was perhaps fitting that the Cubs were also the Pirates’ opponent in the ballpark’s final game. On this day the Pirates swept the Cubs in what turned out to be the final major-league games played at the venerable ballpark in the Oakland neighborhood.

10 As the first Pirate to hit a home run in the new stadium, Stargell won a $1,000 prize that had been donated by a local lumber company.

11 United Press International, Bucks County (Pennsylvania) Courier Times, August 10, 1976.

12 Ibid.

13 Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Daily Intelligencer, October 15, 1979.

14 Associated Press, Titusville (Pennsylvania) Herald, October 2, 2000.

15 Altoona (Pennsylvania) Mirror, August 12, 2001.