Danny Murtaugh – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

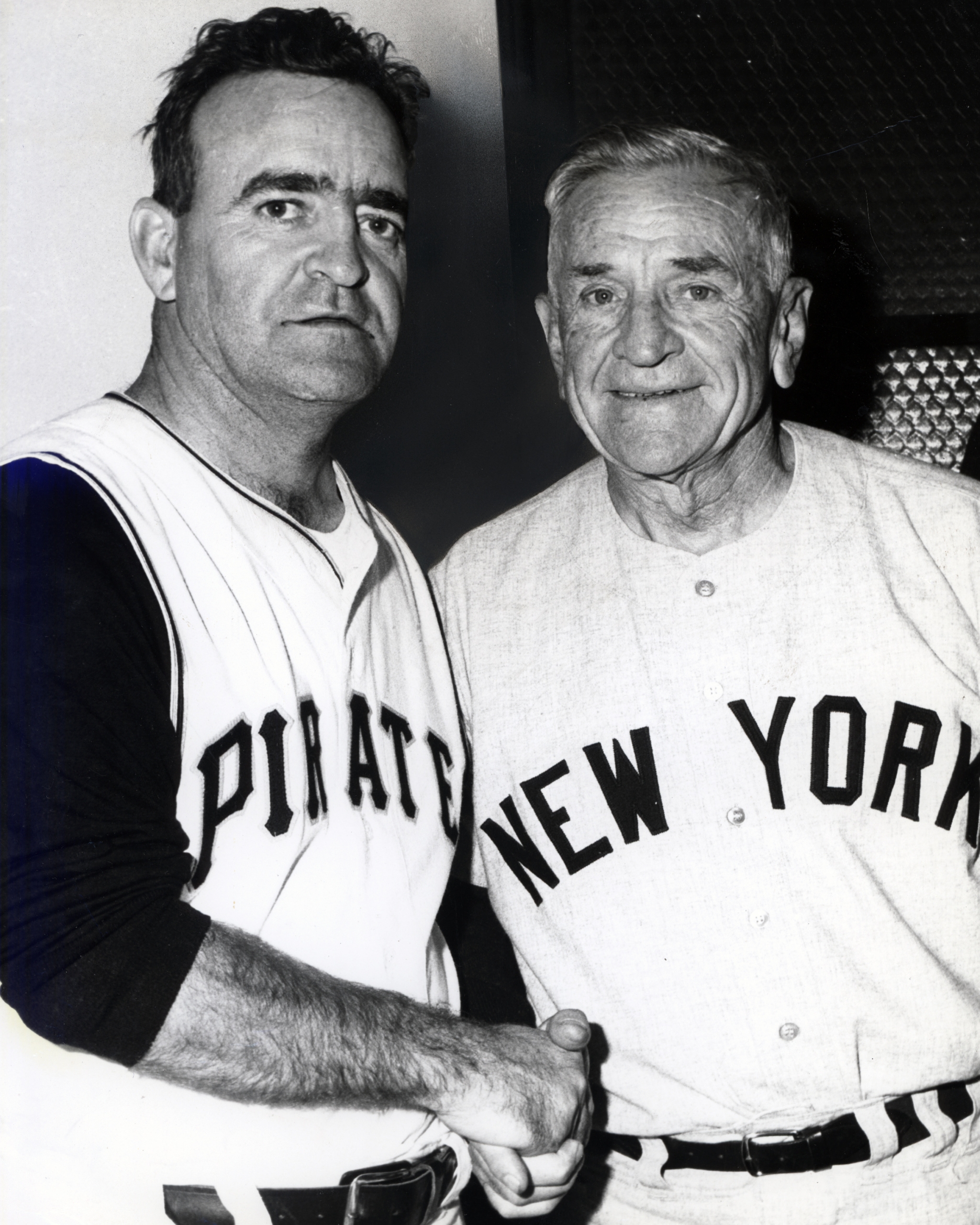

Serial retirement has a long tradition in sports. Boxing has produced many serial retirees, aging fighters who swear each fight is their last until the promise of another big payday becomes too much to resist. In the 2000s, no NFL season was complete without the will-he-won’t-he drama surrounding Brett Favre’s retirement. But perhaps the king of sports retirements is Danny Murtaugh, who retired from baseball as a player in 1951 and then retired as manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates four times in a 13-year span in the 1960s and ’70s.

Serial retirement has a long tradition in sports. Boxing has produced many serial retirees, aging fighters who swear each fight is their last until the promise of another big payday becomes too much to resist. In the 2000s, no NFL season was complete without the will-he-won’t-he drama surrounding Brett Favre’s retirement. But perhaps the king of sports retirements is Danny Murtaugh, who retired from baseball as a player in 1951 and then retired as manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates four times in a 13-year span in the 1960s and ’70s.

Murtaugh was known for his wit and ability to give the media a good quote. As manager he often held court from a rocking chair in his office and offered up gems like “Why certainly I’d like to have a fellow who hits a home run every time at bat, who strikes out every opposing batter when he’s pitching and who is always thinking about two innings ahead. The only trouble is to get him to put down his cup of beer, come down out of the stands, and do those things.”1

Daniel Edward Murtaugh was born on October 8, 1917, at his parents’ home in Chester, Pennsylvania, a city on the Delaware River halfway between Philadelphia and Wilmington, Delaware. He was the middle of five children — the four others were girls — born to Daniel and Nellie (McCarey) Murtaugh. Without the documentation that accompanies a hospital birth, Murtaugh was unsure of his actual birthdate. His family found definitive evidence of the birthdate, ironically enough, at his funeral. A man there remembered the day Murtaugh was born because it was the day that he himself had got married, and Danny’s mother was unable to attend because she was having a baby. The man’s anniversary? October 8, 1917.2 The Murtaughs lived in a working-class Irish neighborhood. Danny’s father worked in the shipyards; Nellie took in laundry to make money and also baked pies that the children would sell around the neighborhood. In The Whistling Irishman, a biography of Murtaugh, his granddaughter Colleen Hroncich wrote that “modest” would be a generous description of the family’s circumstances. She cited the Murtaugh children walking along railroad tracks in search of loose coal to bring home to heat the home, as well as the long-term presence of a large hole in the family dining room because the Murtaughs could not afford to fix it.3

As a youth, Murtaugh played baseball, basketball, and soccer, and even earned a football scholarship offer to attend Villanova University, which he had to decline because he could not afford textbooks or transportation to and from the nearby school.4 Playing for Chester’s team in American Legion ball, Murtaugh got well acquainted with another future major leaguer, Marcus Hook American Legion star Mickey Vernon, who went on to two batting championships and seven All-Star Games. The two established a friendship that endured until Murtaugh’s death.

After leaving high school Murtaugh had no offers to continue his baseball career, so he went to work with his father at the shipyards for Sun Ship, and played baseball and basketball in a local semipro industrial league.5 He followed in the footsteps of his father and grandfather by serving in the local volunteer fire company, and once carried a woman from a burning building only to realize that she had died in his arms.6

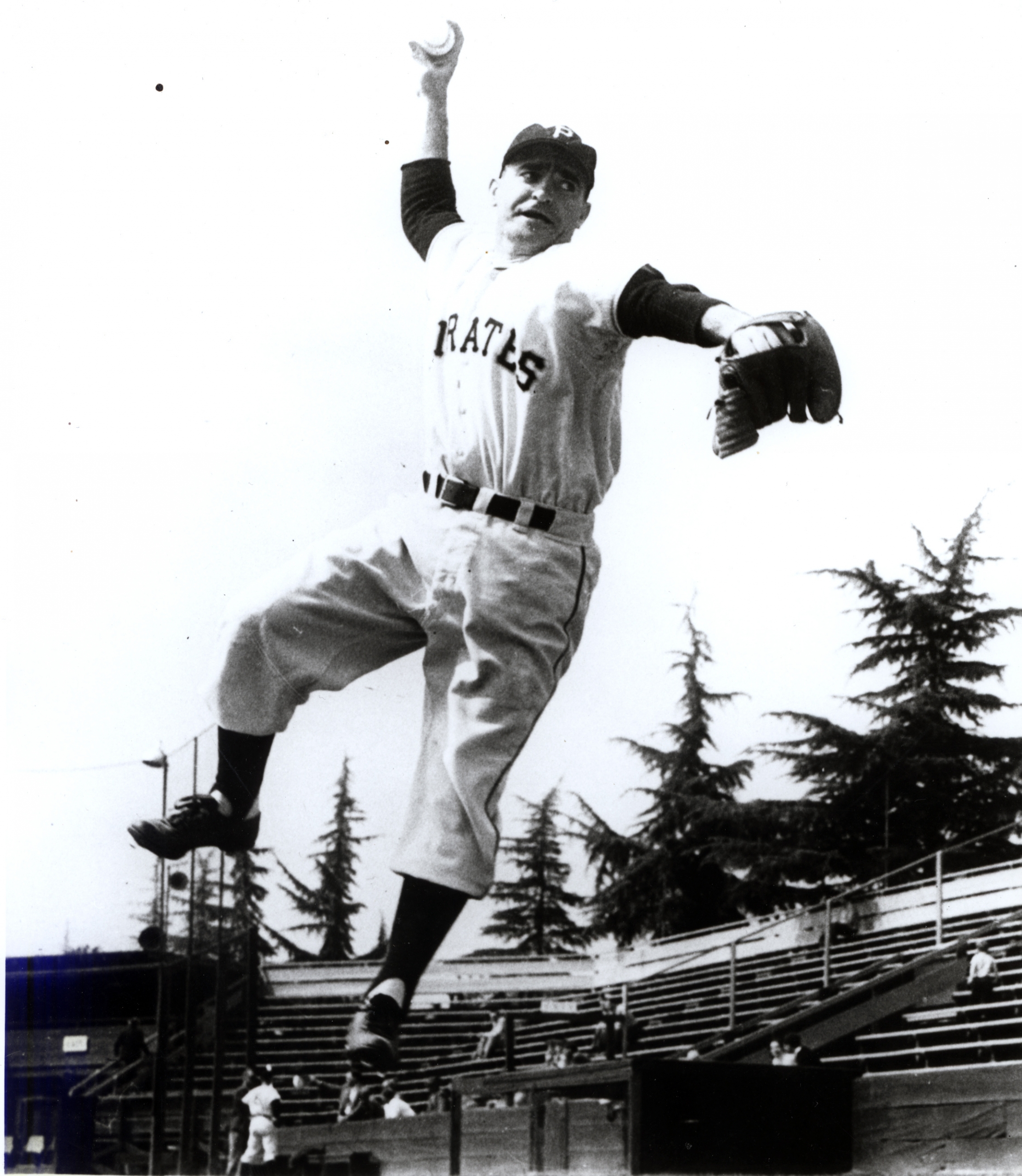

Murtaugh got a chance to play professional baseball in 1937, but to take his shot he had to give up his 35−a−weekjobatSunShipforasalaryof35-a-week job at Sun Ship for a salary of 35−a−weekjobatSunShipforasalaryof65 per month for the Cambridge (Maryland) Cardinals of the Class D Eastern Shore League. He played second base, third base, and shortstop and posted solid offensive numbers as he rose through the Cardinals’ minor-league system between 1937 and 1940. Halfway through the 1941 season he earned a shot at the big leagues, but not with the Cardinals. In late June Murtaugh’s hometown Philadelphia Phillies purchased his contract from the Cardinals, and he made his big-league debut on July 3 in a 4-1 loss to the Boston Braves. Murtaugh played in 85 games for the Phillies in 1941, hitting .219 with 11 RBIs. Though he played in the major leagues for only three months that season, his 18 stolen bases led the National League. The Phillies finished in last place with a woeful 43-111 won-lost record, the fourth of five consecutive seasons the team lost at least 103 games during one of the darkest eras for any team in major-league history.

Coming up as a second baseman, Murtaugh was described in the press as “peppery,” “a spark,” and a “flash.”7 He could run and throw, but felt that he wasn’t adept enough at making the turn at second base, and asked Cincinnati second baseman Lonnie Frey for help after a game against the Reds. Frey obliged by working with Murtaugh on the field for nearly an hour after a game, and Murtaugh credited Frey with helping him stay in the majors for a decade as a second baseman.8 In November after his rookie year, Murtaugh married his high-school sweetheart, Kate Clark.

Murtaugh began the 1942 season playing second base, but before long was moved to third base, then ended up back at the middle infield positions around the All-Star break. For the season he played 60 games at shortstop, 53 at third base, and 32 at second. His batting average increased to .241 and he had 13 stolen bases as the Phillies lost 109 games and finished last again. After the season Murtaugh returned to Sun Ship in Chester to aid in the US war effort.

In May 1943 the Murtaughs’ first child, a son, Timothy, was born. On the field Murtaugh blossomed by hitting .273 and helping the Phillies out of the cellar for the only time between 1938 and 1945. In August he was inducted into the Army. His last game before going into the service was August 19, and the Phillies dubbed the game Danny Murtaugh Night at Shibe Park. Murtaugh reported to Fort Meade, Maryland, where one of his first assignments was to play in a War Bond game in New York between an Army team and a mixed squad of the New York teams. Later he was granted, a transfer to the Air Corps, but after a month it was discovered that he was colorblind, and he was disqualified from flying. He returned to the infantry and spent 1944 and ’45 marching across Europe with the 97th Infantry in the 1st Army, a unit that saw significant battle action and earned three battle stars.9 After the war ended, Murtaugh was assigned to the occupation forces in Japan. He was discharged from the Army 15 days before the start of spring training in 1946.10

Early in the season Murtaugh was sold back to the Cardinals, and spent the rest of the 1946 season at Triple-A Rochester. He was picked by the Boston Braves in the Rule 5 draft after the season, and spent most of the 1947 campaign at Triple-A Milwaukee. After the season Murtaugh was traded by the Braves to the Pittsburgh Pirates with outfielder Johnny Hopp for outfielder-pitcher Al Lyons, outfielder Jim Russell, and catcher Bill Salkeld. He spent 1948-51 with the Pirates, his seasons alternating between productive and weak. His first season 1948, was probably his most productive as a major leaguer; he hit .290 with 71 RBIs and 10 stolen bases as the Pirates vaulted from a last-place finish to fourth. Hobbled by injuries in 1949. Murtaugh batted a dismal .203. A nice bounce-back season in 1950 (.294) was interrupted on August 30 when he was hit in the head by a Sal Maglie fastball and was hospitalized for ten days with a skull fracture. Then, after hitting a meager .199 in 77 games as a 33-year-old in 1951, Murtaugh approached Pirates boss Branch Rickey and was offered a job as player-manager at the Pirates’ Double-A farm team at New Orleans.11

Murtaugh managed the Pelicans for three seasons, then decided to be home with Kate and their two children in Pennsylvania. That desire was sidetracked when in 1955 he was named manager of the Triple-A Charleston (West Virginia) Senators, a financially ailing team that let him go in midseason to cut costs. Pirates general manager Joe Brown offered him the job as the manager at Williamsport of the Double-A Eastern League, but before he made it to Williamsport a spot opened on the Pirates’ coaching staff, and Danny filled the role.12

Murtaugh managed the Pelicans for three seasons, then decided to be home with Kate and their two children in Pennsylvania. That desire was sidetracked when in 1955 he was named manager of the Triple-A Charleston (West Virginia) Senators, a financially ailing team that let him go in midseason to cut costs. Pirates general manager Joe Brown offered him the job as the manager at Williamsport of the Double-A Eastern League, but before he made it to Williamsport a spot opened on the Pirates’ coaching staff, and Danny filled the role.12

In 1956 the Pirates posted a 66-88 record under manager Bobby Bragan. In 1957 the Bucs stood at 36-67 when general manager Brown fired Bragan and named the interim manager. Brown had wanted to give the job to first-base coach Clyde Sukeforth, but Sukeforth declined and recommended Murtaugh.13 Danny led the Pirates to a 26-25 mark under his direction, and Brown removed the interim label before the end of the season.14

The Pirates followed up their strong finish in 1957 by finishing in second place in 1958 with an 84-70 record. He was an overwhelming choice for the Associated Press Manager of the Year award. (He received 149 points in the voting, while the runner-up got only six.)15 But 1959 was disappointing; the Pirates fell to fourth place with a 78-76 mark. That led to a new team rule for 1960: no wives on the road. “Not that I don’t approve of wives. I’d better, I’ve been married for 20 years,” Murtaugh said. “But something ruined us on the road and I gotta find out.”16 He suggested that when wives travel with the team they want to go to shows, shopping, etc., which wears players out and distracts them from the task at hand. Whether or not the ukase was helpful, the 1960 Pirates sprinted out to a 12-3 start by May 1, and starting on May 30 were in first place each day for the rest of the season. (They won 12 more games on the road than they had in 1959.) The Pirates finished seven games ahead of second-place Milwaukee and won their first pennant since the 1927 team was swept by the Ruth–Gehrig Murderer’s Row Yankees.

In the World Series, the Pirates again faced off with the Yankees, who were appearing in their tenth World Series since 1949. The Pirates won a thrilling Series in seven games on Bill Mazeroski’s walk-off home run, and Murtaugh was praised for aligning his pitching staff so that Pirates ace Vern Law could start three games, including the decisive seventh game, while the Yankees’ manager, Casey Stengel waited until Game Three before using his ace, Whitey Ford, allowing Ford only two starts. The Pirates won despite being badly outscored in the Series; the Yankees won three laughers in which they outscored the Pirates by 38-3. But the Pirates were able to scratch out wins in four hard-fought games to become world champions. Of his nerves during the deciding game, Murtaugh said, “I used four packs (of chewing tobacco) and don’t remember spitting.”17 Afterward, Kate told Danny that she had never seen him so happy, to which he replied, “If you had been standing on one side of me and Bill Mazeroski on the other side, and somebody said I had to kiss one or the other, it wouldn’t have been you.”18

After their climactic Series victory, the 1961 Pirates stumbled to sixth place with a record under .500. Near the end of the season Murtaugh’s oldest son, Tim, started college at Holy Cross. Between athletic and academic scholarships Tim was given nearly a full ride, but Danny, who years earlier had been unable to attend Villanova because of financial concerns, wrote to the school’s president asking that his son’s scholarships be awarded to another student, as he was fortunate enough to be able to pay for his son’s education.19

During spring training in 1962 at Fort Myers, Florida, Murtaugh checked himself into the Lee County Hospital, claiming to be suffering the effects of the flu, but instead learned that he had a heart problem. After a few days of rest he was cleared to return to the team. The 1962 Pirates won 93 games (fourth place in the ten-team league), but the ’63 and ’64 teams fell badly to eighth and sixth, respectively. At the end of 1964 Murtaugh, only 46, walked away from managing the team, citing health concerns. (Few knew the extent and nature of his health issues, and he usually blamed his illnesses on the flu and stomach ailments.) He remained with the ballclub as a scout and adviser to GM Joe Brown.20

During Murtaugh’s stay in the front office, which he referred to as the “golf tour of baseball,” he was able to spend more time with Kate and their high-school-age daughter, Kathy. (Danny Jr. had joined Tim at Holy Cross.) The Pirates signed Tim in 1965, and he caught nine seasons in the organization, reaching the Triple-A level. He also managed for seven seasons.21

The Pirates muddled through the first half of the 1967 season under manager Harry Walker, who was fired after 84 games. Murtaugh agreed to manage the team the rest of the season, posting a 39-39 mark nearly identical to Walker’s 42-42. Murtaugh admitted that he was not in the right frame of mind to manage and ended up serving more as a cheerleader on the bench than a real manager. Before the season ended the team announced that Murtaugh would not return as manager, and named him director of player acquisition and development, where he oversaw the farm system and scouting. After two seasons the Pirates sought a replacement for manager Larry Shepard, and Joe Brown and Murtaugh met deep into the night regarding potential candidates. Early the next morning Danny knocked on Brown’s door and asked why he himself shouldn’t be the manager, with Brown replying that the job was his any time as long as he had the permission of his doctor and his wife. Both consented and in Danny’s return the Pirates closed down Forbes Field, moved into Three Rivers Stadium, and won the new National League East division before losing in the National League Championship Series to Cincinnati. Murtaugh was named Manager of the Year.22

Murtaugh and his star outfielder Roberto Clemente sought to assure all who asked that everything was fine with their relationship, which admittedly had had rough patches during Murtaugh’s first tenure with the team. Murtaugh said, “Clemente is Clemente. He’s the best player I’ve ever seen. I’m old enough and I think smart enough to get along with anybody on our ballclub — especially if he’s a .350 hitter.”23

On May 20, 1971, Murtaugh was admitted to Christ Hospital in Cincinnati with chest pains. After tests, doctors could find nothing wrong with him. He spent two weeks in hospitals in Cincinnati and Pittsburgh and was unsure if he would ever return to uniform. He finally did return to the dugout on June 6, ten pounds lighter.24

With and without Murtaugh, the 1971 Pirates ran roughshod over the National League, winning the East by seven games over St. Louis before dispatching the Giants in four games in the NLCS. They went on to beat Baltimore in seven games for their second world championship in 12 seasons, both under Murtaugh’s direction. In a memorable game on September 1, a 10-7 victory over the Phillies, Murtaugh made history by writing out a lineup of Rennie Stennett, Gene Clines, Roberto Clemente, Willie Stargell, Manny Sanguillen, Dave Cash, Al Oliver, Jackie Hernández, and Dock Ellis. For the first time in major-league history a team had a starting lineup of minority players. With the Pirates in the midst of a pennant race, the notion of a gimmick was easily brushed aside. Asked afterward if he realized the significance of the lineup, Murtaugh replied, “I knew we had nine Pirates.”25

After finishing the 1971 season with his second World Series title, Murtaugh again moved into the front office, once again citing concerns over his health. (He did return to the field to manage the National League in the 1972 All-Star Game.)

Late in the 1973 season Joe Brown asked Murtaugh to take over as manager for a fourth time. After receiving the requisite doctoral and spousal permission, he returned to the dugout for the final 26 games of the 1973 season before winning back-to-back division titles in ’74 and ’75 and losing in the NLCS both years. Despite rumors that he would quit, Murtaugh returned for the 1976 season and led the Pirates to a second-place finish before announcing at season’s end that he was stepping down — this time for good — because of his health and his desire to spend more time with his family, which now included grandchildren.

On November 30, 1976, Murtaugh went to a doctor’s appointment and was told that everything looked good. But later that day he suffered a stroke at home. He died at Crozer Chester Hospital on December 2 at the age of 59. He was survived by his wife, Kate; his sons, Tim and Danny Jr.; his daughter, Kathy; and five grandchildren. His funeral drew many of his players, including Willie Stargell, Manny Sanguillen, and Al Oliver, as well as longtime GM Joe Brown and radio voice Bob Prince, former major leaguer Mickey Vernon, and Pittsburgh Steelers owner Art Rooney.26

Murtaugh’s number 40 was retired by the Pirates in 1977. As of 2012 his 1,115 victories as a manager ranked him second on the team behind Fred Clarke.

Perhaps the most definitive words on why anyone would want to keep coming back to manage a ball club belong to Murtaugh himself, who said, “Managing a ballclub is like getting malaria. Once you’re bitten by the bug, it’s difficult to get it out of your bloodstream.”27

This biography is included in the book “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2013), edited by Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Other than sources cited in the notes, the author also consulted:

Baseball Digest

Baseball-Reference.com

New York Times

The Sporting News

Sports Illustrated

Notes

1 Sports Illustrated, October 7, 1974.

2 Colleen Hroncich, The Whistling Irishman: Danny Murtaugh Remembered (Philadelphia: Sports Challenge Network Publishing, 2010), 1.

3 Hroncich, 2.

4 Hroncich, 5.

5 Hroncich, 6.

6 Hroncich, 7.

7 Hroncich, 19.

8 Hroncich, 22.

9 Hroncich, 41.

10 Hroncich, 43.

11 Hroncich, 62.

12 Hroncich, 82-83.

13 Harold Rosenthal, Baseball’s Best Managers (New York: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1961), 103.

14 Rosenthal, 104.

15 Hroncich, 98.

16 Rosenthal, 107.

17 Rick Cushing, 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates, Day by Day. (Pittsburgh: Dorrance Publishing, 2010), 377.

18 Kal Wagenheim, Clemente! (Republished by E-Reads.com, original copyright 1973), 4.

19 Hroncich, 135.

20 Hroncich, 160-2.

21 Hroncich, 163.

22 Hroncich, 164-7.

23 Wagenheim, page number unavailable.

24 Hroncich, 176.

25 Baseball Digest, September 1995.

26 Hroncich, 233-4.

27 Cushing, 377.