Cas-OFFinder: a fast and versatile algorithm that searches for potential off-target sites of Cas9 RNA-guided endonucleases (original) (raw)

Abstract

Summary: The Type II clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas system is an adaptive immune response in prokaryotes, protecting host cells against invading phages or plasmids by cleaving these foreign DNA species in a targeted manner. CRISPR/Cas-derived RNA-guided engineered nucleases (RGENs) enable genome editing in cultured cells, animals and plants, but are limited by off-target mutations. Here, we present a novel algorithm termed Cas-OFFinder that searches for potential off-target sites in a given genome or user-defined sequences. Unlike other algorithms currently available for identification of RGEN off-target sites, Cas-OFFinder is not limited by the number of mismatches and allows variations in protospacer-adjacent motif sequences recognized by Cas9, the essential protein component in RGENs. Cas-OFFinder is available as a command-line program or accessible via our website.

Availability and implementation: Cas-OFFinder free access at http://www.rgenome.net/cas-offinder.

Contact: baesau@snu.ac.kr or jskim01@snu.ac.kr

1 INTRODUCTION

Genome editing with engineered nucleases is broadly useful for biomedical research, biotechnology and medicine. Engineered nucleases cleave chromosomal DNA in a targeted manner, and the repair of the resulting double-strand breaks by endogenous systems gives rise to targeted genome modifications in cultured cells, animals and plants. We and others have developed three different types of engineered nucleases: zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) (Bibikova et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2009), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) (Kim et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2011) and RNA-guided engineered nucleases (RGENs) (Cho et al., 2013; Cong et al., 2013; Jinek et al., 2013; Mali et al., 2013) derived from the Type II clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated (Cas) system, an adaptive immune response in bacteria and archaea.

Unlike ZFNs and TALENs whose DNA specificities are determined by DNA-binding proteins, RGENs use complementary base pairing to recognize target sites. RGENs consist of (i) dual RNA components comprising sequence-invariant tracrRNA and sequence-variable guide RNA termed crRNA [or single-chain guide RNA (sgRNA) constructed by linking essential portions of tracrRNA and crRNA (Jinek et al., 2012)] and (ii) a fixed protein component, Cas9, that recognizes the protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) downstream of target DNA sequences corresponding to guide RNA. Custom-designed RGENs are produced simply by replacing guide RNAs, making this system easy to access.

Unfortunately, RGENs cleave not only on-target sites but also off-target sites that differ by up to several nucleotides from the on-target sites (Cho et al., 2014; Fu et al., 2013; Hsu et al., 2013), causing unwanted off-target mutations and chromosomal rearrangements. These undesired off-target effects raise significant concerns for using RGENs as genome editing tools in diverse applications. To address this issue, researchers must be able to search for potential off-target sites in the genome. Sequence alignment tools such as TagScan (Cradick et al., 2011; Iseli et al., 2007), Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009) or GPGPU-enabled CUSHAW (Liu et al., 2012) can be used to find potential off-target sites, but are limited by the number of mismatched bases allowed and a requirement for a fixed PAM sequence.

Here we introduce a fast and highly versatile off-target searching tool, Cas-OFFinder. Importantly, Cas-OFFinder is written in OpenCL, an open standard language for parallel programming in heterogeneous environments, enabling operation in diverse platforms such as central processing units (CPUs), graphics processing units (GPUs) and digital signal processors (DSPs).

2 METHODS

2.1 Concept of Cas-OFFinder

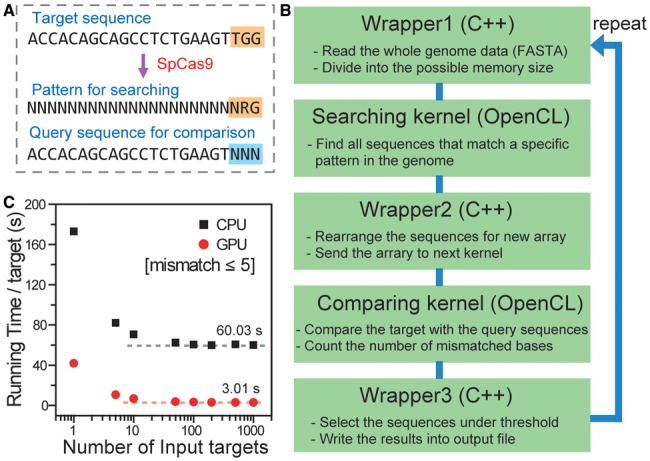

Versions of Cas9 derived from three different species have been exploited to edit genes in human cells. These Cas9 proteins recognize different PAM sequences. Cas9 originated from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) recognizes 5′-NGG-3′ PAM sequences and, to a lesser extent, 5′-NAG-3′. Cas9 from Streptococcus thermophilus (StCas9) (Cong et al., 2013) and that from Neisseria meningitidis (NmCas9) (Hou et al., 2013) recognizes 5′-NNAGAAW-3′ (W = A or T) and 5′-NNNNGMTT-3′ (M = A or C), respectively. The degeneracy in PAM recognition by Cas9 must be accounted for when searching for potential off-target sites. In the case of SpCas9, Cas-OFFinder first compiles all the 23-bp DNA sequences composed of 20-bp sequences corresponding to the sgRNA sequence of interest and the 5′-NRG-3′ PAM sequences (Fig. 1A). Cas-OFFinder then compares all the compiled sequences with the query sequence and counts the number of mismatched bases in the 20-bp sgRNA sequence.

Fig. 1.

(A) The scheme of Cas-OFFinder. (B) The workflow of Cas-OFFinder. (C) Running time per target site as a function of the number of input target sites via CPU (black squares) and GPU (red circles)

2.2 Workflow of Cas-OFFinder

Cas-OFFinder is composed of two different OpenCL kernels (a searching kernel and a comparing kernel) and C++ (wrapper) parts (Fig. 1B). First, Cas-OFFinder reads genome sequence data files in single or multi-sequence FASTA formats. To read and parse FASTA files, an open-source FASTA/FASTQ parser library is used. Although OpenCL supports various processors, the memory of the devices is not always large enough for big data analysis. To overcome the memory limitation of OpenCL devices, wrapper1 divides the genome data into units of the largest possible size allowed by the device memory. These divided chunks are then loaded into the searching kernel that compiles all sites that include a PAM sequence in the entire genome. To search for and select these specific sites rapidly and effectively, the searching kernel runs independently on every calculation unit of a processor, i.e. all searching processes on the calculation units are accomplished simultaneously. After this step, wrapper2 collects the information about the specific sites containing PAM sequences and delivers these sequences to the comparing kernel, which counts the number of mismatched bases. Similar to the searching kernel, all comparing processes on the calculation units are accomplished simultaneously. Finally, wrapper3 selects potential off-target sites that have fewer mismatched bases than a given threshold, and writes the results into an output file with the following information: chromosome number, position, direction, number of mismatched bases and potential off-target DNA sequences with mismatched bases noted in lowercase letters. These processes are repeated until all the divided chunks are loaded.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To evaluate the performance of Cas-OFFinder, we first chose arbitrary SpCas9 target sites in the human genome and ran Cas-OFFinder with query sequences via CPU (Intel i7 3770K) or GPU (AMD Radeon HD 7870). Notably, running time per target site was decreased as the number of target sites was increased (Fig. 1C). This result is expected because the searching kernel works only once for many input targets. The speed of Cas-OFFinder based on GPU (3.0 s) was 20× faster than that of CPU (60.0 s) when 1000 target sites were analyzed. We also used Cas-OFFinder to search for potential off-target sites of NmCas9, which recognizes 5′-NNNNGMTT-3′ (where M is A or C) PAM sequences in addition to a 24-bp target DNA sequence specific to guide RNA in human and other genomes (Table 1). Note that Cas-OFFinder allows mixed bases to account for the degeneracy in PAM sequences.

Table 1.

Running time of Cas-OFFinder via GPU to search for NmCas9 potential off-target sites

| Data set (size) | Number of mismatches | Time for 100 targets |

|---|---|---|

| H. sapiens genome (3.01 Gb) | 1 | 76.4 ± 2.0 s |

| H. sapiens genome (3.01 Gb) | 5 | 79.9 ± 1.6 s |

| H. sapiens genome (3.01 Gb) | 10 | 114.4 ± 3.0 s |

| M. musculus genome (2.65 Gb) | 5 | 62.6 ± 2.4 s |

| D. rerio genome (1.32 Gb) | 5 | 37.7 ± 3.5 s |

| A. thaliana genome (116 Mb) | 5 | 4.8 ± 0.8 s |

In conclusion, Cas-OFFinder enables searching for potential off-target sites in any sequenced genome rapidly without limiting the PAM sequence or the number of mismatched bases. These features make Cas-OFFinder applicable to ZFNs, TALENs and transcription factors that are prone to off-target DNA recognition.

Funding: National Research Foundation of Korea (2013000718 to J.-S.K.) and the Plant Molecular Breeding Center of Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (PJ009081), the National Research Foundation of Korea (2013065262), TJ Park Science Fellowship (to S.B.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Bibikova M, et al. Enhancing gene targeting with designed zinc finger nucleases. Science. 2003;300:764. doi: 10.1126/science.1079512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SW, et al. Targeted genome engineering in human cells with the Cas9 RNA-guided endonuclease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:230–232. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SW, et al. Analysis of off-target effects of CRISPR/Cas-derived RNA-guided endonucleases and nickases. Genome Res. 2014;24:132–141. doi: 10.1101/gr.162339.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cradick TJ, et al. ZFN-site searches genomes for zinc finger nuclease target sites and off-target sites. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, et al. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:822–826. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Z, et al. Efficient genome engineering in human pluripotent stem cells using Cas9 from Neisseria meningitidis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:15644–15649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313587110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu PD, et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:827–832. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iseli C, et al. Indexing strategies for rapid searches of short words in genome sequences. PLoS One. 2007;2:e579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M, et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M, et al. RNA-programmed genome editing in human cells. eLife. 2013;2:e00471. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, et al. Targeted genome editing in human cells with zinc finger nucleases constructed via modular assembly. Genome Res. 2009;19:1279–1288. doi: 10.1101/gr.089417.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, et al. A library of TAL effector nucleases spanning the human genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:251–258. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, et al. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, et al. CUSHAW: a CUDA compatible short read aligner to large genomes based on the Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1830–1837. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JC, et al. A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:143–148. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]