William Bolcom and Joan Morris Interviews with Bruce Duffie . .

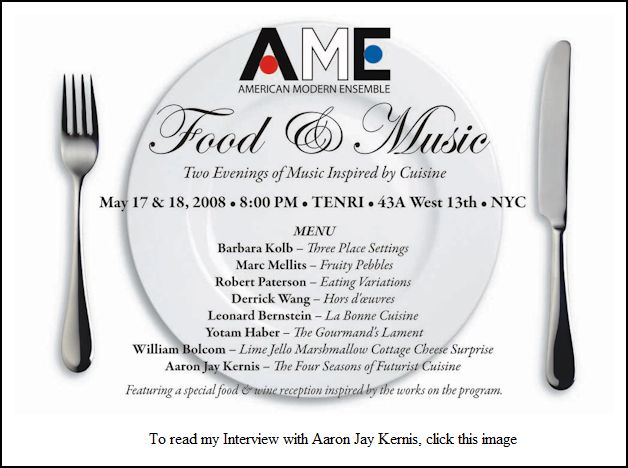

. . . . . . . (original) (raw)

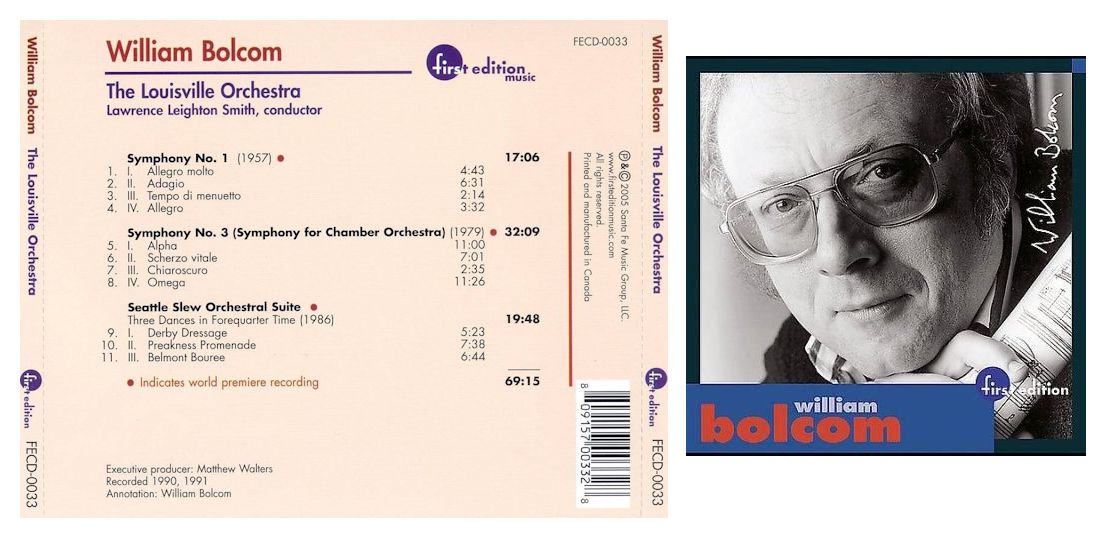

Composer / Pianist William Bolcom

== and ==Mezzo - Soprano Joan MorrisTwo Conversations with Bruce Duffie

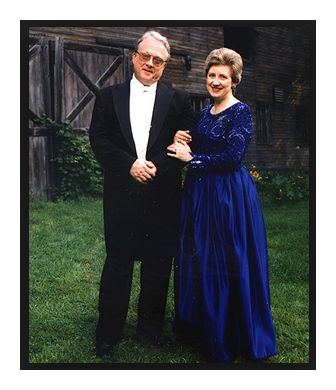

William Elden Bolcom (born in Seattle, Washington, May 26, 1938) is an American composer and pianist. He has received the Pulitzer Prize, the National Medal of Arts, a Grammy Award, the Detroit Music Award and was named 2007 Composer of the Year by Musical America. Bolcom taught composition at the University of Michigan from 1973–2008. He is married to mezzo-soprano Joan Morris.

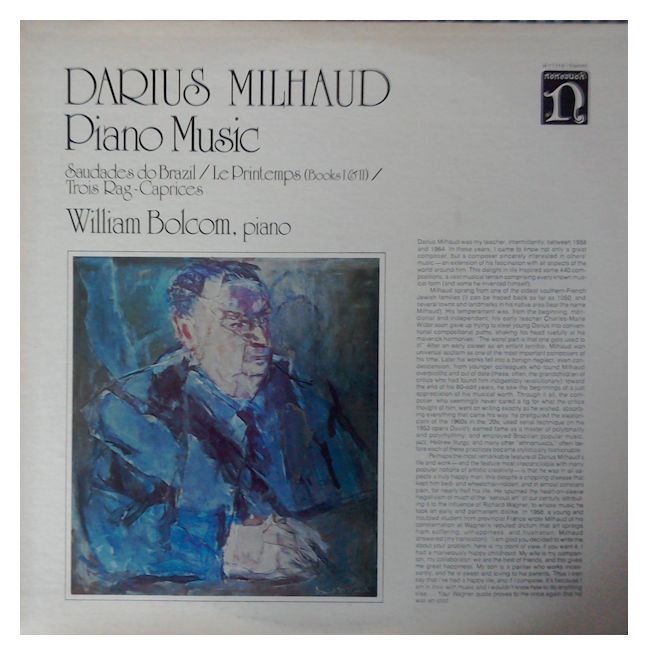

At the age of 11, he entered the University of Washington to study composition privately with George Frederick McKay and John Verrall and piano with Madame Berthe Poncy Jacobson. He later studied with Darius Milhaud at Mills College while working on his Master of Arts degree, with Leland Smith at Stanford University while working on his D.M.A., and with Olivier Messiaen at the Paris Conservatoire, where he received the 2ème Prix de Composition.

Bolcom won the Pulitzer Prize for music in 1988 for 12 New Etudes for Piano. In the fall of 1994, he was named the Ross Lee Finney Distinguished University Professor of Composition at the University of Michigan. In 2006, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts.

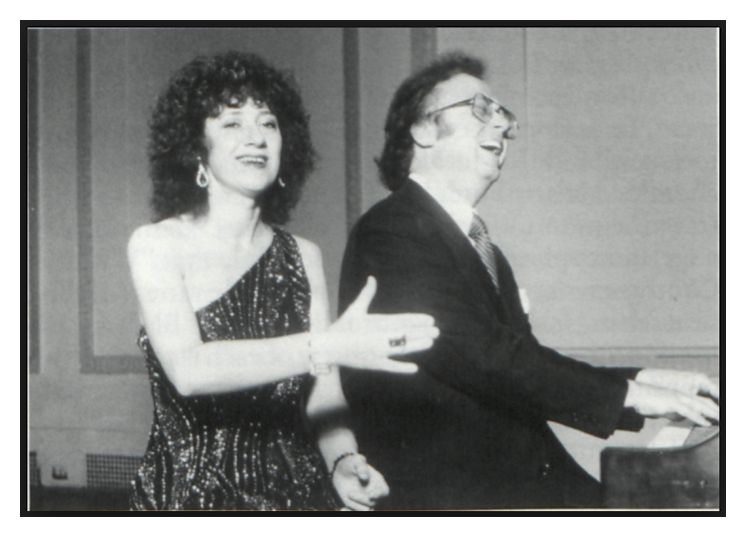

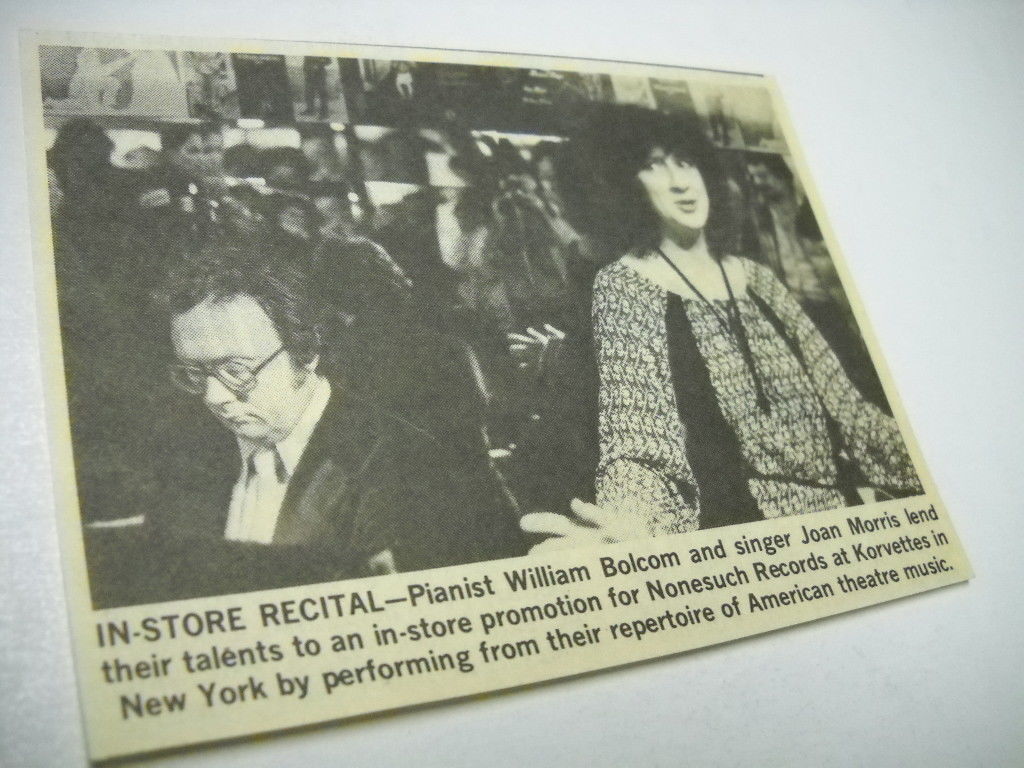

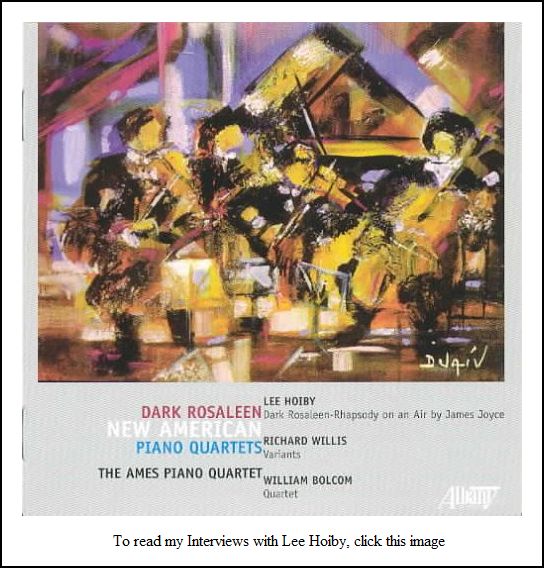

As a pianist, Bolcom has performed and recorded frequently in collaboration with Joan Morris (born in Portland, Oregon, February 10, 1943), whom he married in 1975. Bolcom and Morris have recorded more than two dozen albums together, beginning with the Grammy nominated After the Ball, a collection of popular songs from around the turn of the 20th century. Their primary specialties in both concerts and recordings are showtunes, parlor, and popular songs from the late 19th and early 20th century, by Henry Russell, Henry Clay Work, and others, and cabaret songs. As a soloist, Bolcom has recorded his own compositions, as well as music by Gershwin, Milhaud, and several of the classic Ragtime composers.

Bolcom's compositions date from his eleventh year. Early influences include Roy Harris and Béla Bartók. His compositions from around 1960 employed a modified serial technique, under the influence of Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Luciano Berio, whose music he particularly admired. In the 1960s he gradually began to embrace an eclectic use of a wider variety of musical styles. His goal has been to erase boundaries between popular and art music.

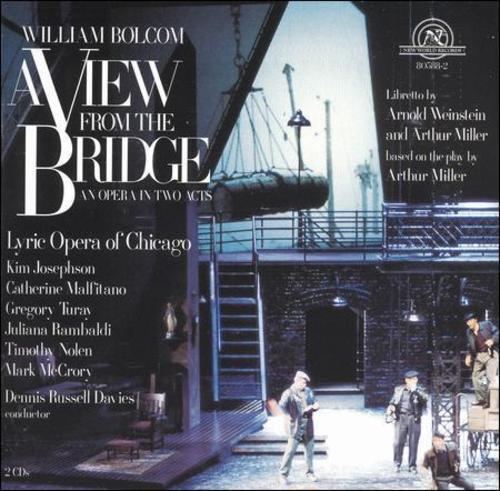

He has composed four major operas, the first three commissioned and premiered by Lyric Opera o Chicago, and conducted by Dennis Russell Davies:McTeague, based on the 1899 novel by Frank Norris, with libretto by Weinstein, was premiered on October 31, 1992; A View from the Bridge, with libretto by Weinstein and Arthur Miller, was premiered October 9, 1999; and A Wedding based on the 1978 motion picture by Robert Altman and John Considine, with libretto by Weinstein and Altman, was premiered on December 11, 2004. Dinner at 8 was composed with librettist Mark Campbell, based on the George S. Kaufman and Edna Ferber play of the same name, was premiered March 11, 2017, by the commissioning organization, Minnesota Opera.

He has also composed Lyric Concerto for Flute and Orchestra for James Galway, the Concerto in D for Violin and Orchestra for Sergiu Luca, the Concerto for Clarinet and Orchestra for Stanley Drucker, and Concert Suite for Alto Saxophone and Band, composed for University of Michigan professor Donald Sinta in 1998. He composed his Concerto Gaea for Two Pianos (left hand) and Orchestra for Gary Graffman and Leon Fleisher, both of whom have suffered from debilitating problems with their right hands. It received its first performance on April 11, 1996 by the Baltimore Symphony conducted by David Zinman. The concerto is constructed so that it can be performed in one of three ways: with either piano part alone with reduced orchestra, or with both piano parts and the two reduced orchestras combined into a full orchestra. This structure mimics that of a similar three-in-one work by his teacher, Darius Milhaud.

Bolcom's other works include nine symphonies, twelve string quartets, four violin sonatas, a number of piano rags (one written in collaboration with William Albright), four volumes of Gospel Preludes for organ, four volumes of cabaret songs, three musical theater works [which in the interview below he calls 'operas for actors'] (Casino Paradise,Dynamite Tonite, and Greatshot; all with Weinstein), and a one-act chamber opera, Lucrezia, with librettist Mark Campbell. William Bolcom was also commissioned to write Recuerdos for two pianos by The Dranoff International Two Piano Foundation.

-- Throughout this page, names which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

On this webpage are two interviews with composer/pianist William Bolcom. The first, which took place in June of 1986, also included the participation of his wife, mezzo-soprano Joan Morris. As with some other musical couples that I

’ve interviewed, on occasion they both responded to my questions together back and forth, and I was perceptive enough not to interrupt!

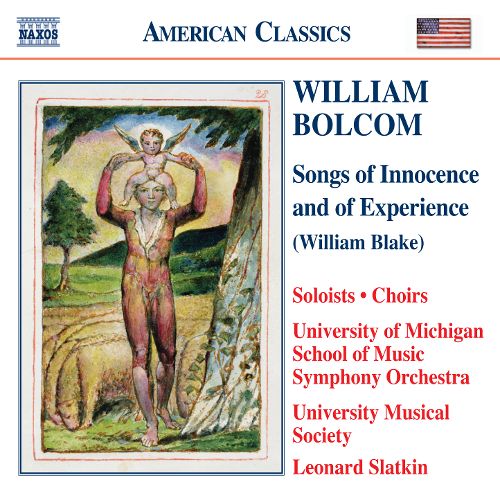

They were in Chicago for the Grant Park Music Festival, which was giving performances of his Songs of Innocence and Experience, a more than two-hour setting of poems by William Blake for soloists, choruses, and orchestra, which was premiered in 1984 in Stuttgart, culminating twenty-five years work.

The second interview, with Bolcom alone, took place six and a half years later, in November of 1992, when Lyric Opera of Chicago was presenting the World Premiere of what would be the first of three of his operas for the Windy City, McTeague, featuring Ben Heppner in the title role, Catherine Malfitano, and conducted by Dennis Russell Davies. [The other two operas were _A View from the Bridge_, and _A Wedding_, both again with Malfitano and Davies, and featuring Kim Josephson as Eddie Carbone in _View from the Bridge_, and Jerry Hadley in A Wedding.]

Be forewarned that in the second conversation, we get into some heavy discussions about the creation and meaning of music. The first one, however, deals with many of the lighter works in their repertoire.

Grant Park is an annual summer festival which takes place outdoors on the lakefront in downtown Chicago, so some of the comments in this first meeting reflect that situation . . . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: I was going to make a separate list of questions for you as composer and as performer, but then I wondered how you separate the two

— if at all?

William Bolcom: Absolutely, I don’t. I consider myself a ‘musician’. I’ve always been a ‘musician’. I’ve always thought that’s what I did

— I compose and I perform — which, in a way, is a restoration of the earlier non-classified, non-specialized way of doing music. I still feel that I compose, and this is my major activity, what I want to do the most and certainly the one that is the most time consuming.

BD: Yet in many circles you’re more well-known as a performer.

WB: That depends on what kind of world you’re talking about. I’m becoming more known as a composer, but you’re right, of course. Certainly I have a national reputation — if that is what you can call it — with my wife, Joan, which I have enjoyed. That has been from our records together and our performing careers, there’s no question about that. This is not a time where a modern composer is extremely known or revered or followed, particularly in this country, and I’m afraid it’s not that much better in Europe. But that wasn’t the reason we went into performing. We’ve always wanted to do that. One of the things we wanted to do was to perform, and we have indeed performed over the last fourteen years, and had a wonderful time doing it.

WB: That depends on what kind of world you’re talking about. I’m becoming more known as a composer, but you’re right, of course. Certainly I have a national reputation — if that is what you can call it — with my wife, Joan, which I have enjoyed. That has been from our records together and our performing careers, there’s no question about that. This is not a time where a modern composer is extremely known or revered or followed, particularly in this country, and I’m afraid it’s not that much better in Europe. But that wasn’t the reason we went into performing. We’ve always wanted to do that. One of the things we wanted to do was to perform, and we have indeed performed over the last fourteen years, and had a wonderful time doing it.

BD: As a composer, what do you expect from the public that comes to hear one of your pieces?

WB: A fair hearing. I hope they like it. This is a piece [_Songs of Innocence and Experience_], has probably something in it for everyone. This is true with the Blake poems that I took them from, and this is an experience which I’ve been producing with the Grant Park people who’ve been wonderful in every way.

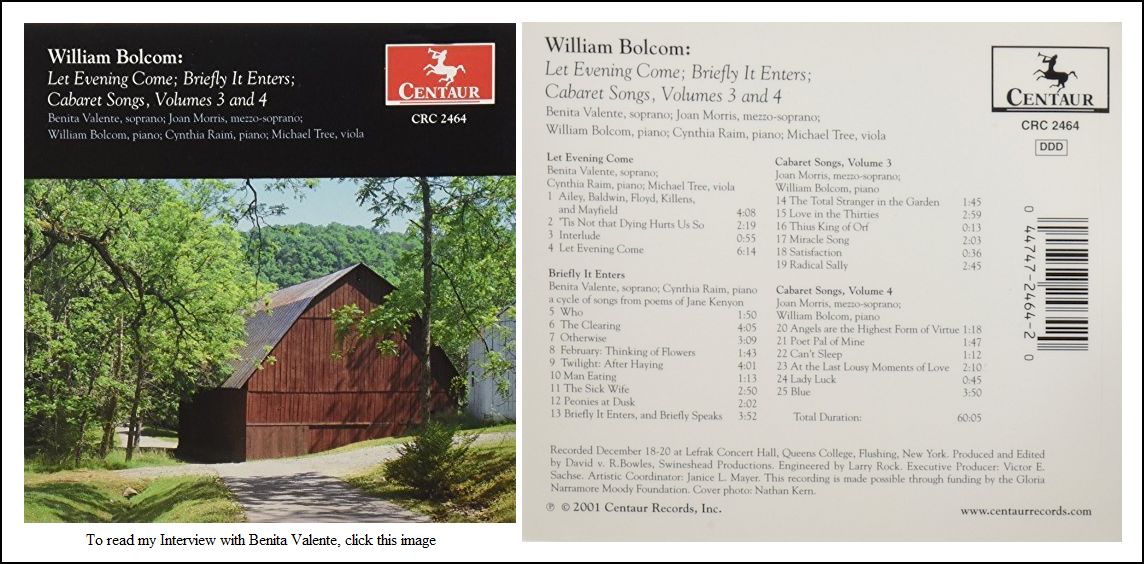

BD: Is this going to be recorded? [_See photo at left of CD conducted by Leonard Slatkin, made eighteen years later, in 2004_]

WB: We’re hoping to, but there’s going to have to be some foundation or other financial support because the total costs they’re estimated to be around to half a million dollars when you count the cost of the recording, the artists’ fees, and all the other things involved in a production of this size. There are 290 people performing here in Grant Park. So we’re trying to raise the money, and of course it will never make a big profit because this is serious music. I’m not Michael Jackson. But it’s still worth doing, and there are many people who are doing something about it. It seems to have been the piece of mine that has had the most response, and at least it elicits the most curiosity for people.

BD: Would you ever be surprised if you record sells as much as Michael Jackson?

WB: [Laughs] Well, I’d be delighted. That means I wouldn’t necessarily have to do some of the things I have to do to make a living! That would be very nice, and I wouldn’t mind it. But I don’t know... whatever happens will happen. One can never deal with these things as any expectancy. It’s not the same thing as, say, putting out a new line nail polish.

BD: If you had all the money that you needed, what would you do

— just compose all day?

WB: Probably, but I still would want to perform with my wife. I would miss that audience response. It’s very important to have some kind of one-to-one connection with people. I like that. I like looking at faces. I don’t always want to have the electronic medium between us. In fact, in that way I’m diametrically opposite to Glenn Gould, for example, who didn’t really want to have those people out there.

BD: Is it important, though, for a composer

— yourself, or any contemporary composer — to get their pieces recorded?

WB: It’s the only way that they get disseminated in a time when we don’t have an amateur culture to pick up a piece of music and read and try to learn it that way. That’s one of the things the composers of the past could reasonably depend on, so that kept the whole publishing world going. Today it’s a marginal business, and it’s basically really for the delectation of musicians who often as not just Xerox a thing from the library instead of buying new copies. We really don’t make any money from that, but it’s not even that. It’s a question of getting your pieces disseminated. When you can buy a recording, people will because it’s a more natural thing to do, and it presents a fantastic range of possibilities today. It doesn’t necessarily matter whether it’s CD or mono or 78 or 33. Just the fact that you can buy a performance and have it at home is so different from any other time before us that it has changed the whole business, and it’s changed the whole world of music, too. In certain ways it’s made it more passive, and I’m sorry about that. I love the idea of everybody who is somehow involved with a particular art also practicing it. Poets have that, and many people who follow poetry are also themselves poets. But many people who follow music are not in any way involved with doing music.

BD: This brings me to one of my favorite questions. For whom do you write?

WB: I write for myself and I write for everyone else in the world. Realistically I know everyone else in the world is not necessarily going to hear everything or anything that I write, but I hope to reach other humans. That’s the main thing. I never have thought of myself writing for a particular public. In fact, I want to cut across any of those classifications. I’m sorry for all of the classes that people put themselves into. In the end you get boxed in. I want to be a human being at large, and I hope in a strange way that everyone else will pick up that spirit from whatever anybody like me will do.

BD: At whose doorstep can be lay the blame for putting these major divisions between the kinds of performers?

WB: It’s probably the mercantile spirit. As in French, you don’t mix up the dish towels with the napkins. It’s an old saying, and we seem to find the same need to classify. We’ve had that notion, that mentality, for many, many years. It’s the nation of shopkeepers that we are. [_With a mock-stern tone_] We have to put things in niches and they have to stay there, by God. If they have to move about, then they are suddenly very dangerous and they won’t stay put. That’s the part that’s too bad, because anything that’s really interesting is going to be volatile. So I guess we just have to find out whether we can somehow make other people feel equally antsy about always having to stay in classes. That’s what I’m hoping to see happen.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] So now can we slap the ‘crossover’ label on you???

WB: [Laughs] I hate that because that would be honoring these classes even more than ever. I’d rather transcend them than be a ‘crossover’ person. My own objection is to all these people talking about ‘fusion’ and ‘crossover’

— assuming that those classifications are watertight and are somehow God-given. I don’t think that’s true. That’s just a hand-over we have put on things, and if we begin to believe in our own nomenclature, that’s too bad. It boxes everything in, and I don’t like that.

BD: Do you perform differently for the microphone than you do for a live audience?

WB: Of course! Everybody does. We try to find a different kind of compromise, however. Just recently we’ve made two live recordings, both of which are on RCA, and we had forty, fifty, sixty people out in front of us. We would record the same song maybe three times, and out of that you have various takes, so they can cut it as they might. You will hear audience response, and I like that. That makes it a do-able human experience in all kinds of ways. It also means that you have a certain kind of

‘momentariness’. Sometimes the way that people record these days— in which you can edit anything in or out or sideways, and so forth — all the imperfections are simply just moved out. It’s okay! I don’t mind recording like that, and for certain pieces it is absolutely right to do things like that. But for other things I like a little looseness.  BD: Has it become too sterile?

BD: Has it become too sterile?

WB: I think so.

BD: Does it ever become too perfect?

WB: I think so, yes, and I don’t think we need that. We need the engagement of immediacy of a certain kind of moment with something happening right now, and that’s the thing you can often lose in a recording.

BD: How do the two of you decide which songs you will put into your repertoire and which songs you will not?

Joan Morris: This is why we don’t like to print a program. We like to be responsive, and when we come to a town we find out what the sponsor would like to hear. Maybe someone will tell us at the last minute that they hope we’re going to do such-and-such. Then, at least we know there’s one song someone out there wants to hear. Also, it keeps it fresh for us, and we can put in new material that we’re trying out. Some of the songs we’ve recorded, and it’s always interesting to me to see which ones stay in our repertoire, and others we don’t seem to do much after we’ve recorded them. Some we tend to do quite a lot that really are the classics for us and the audience response is the most rewarding.

WB: And every audience is different. The one thing you’re trying to do is psyche out the difference between one audience and another, so we usually try to go to a place enough in advance

— say the day before — to be able to talk to the people who’ve hired us, to get a feeling for the place a little bit. Then we think about it, and as late as we dare we put together our program. In that way, every program is a bit different. Sometimes we will do a lot that seem a little light, but there’ll be certain ways that we will subtly slide it toward the people who you’ve gotten to know a bit.

JM: It also depends on the hall.

WB: Yes!

JM: We just played the Ordway in St. Paul, which is 1,800 seats and has a wonderful sound. But there you do numbers which you want to do in a big space, that really reach to the furthest corner of the audience. Maybe you wouldn’t do ‘The Physician’ [by Cole Porter] because all those words are going so fast. Some of it might get lost in that space. If it’s a more intimate hall, then we characterize the program that way.

WB: This doesn’t preclude the possibility of taking a very large place and turning it into a small place, just by willing it. You can do that.

JM: Oh, that’s fun, too!

BD: So you feed off the audience wherever you are?

WB: Absolutely!

JM: Sure!

WB: We want to look at their faces, if at all possible. We like to see them, and every so often you’ll see somebody out in the audience that [pretends to be excited] goes just like this, so excited and just jumping up and down! It’s like balm to you. You just feel all this terrific energy coming back, and you’re not exhausted. Other times they just sit there like a bunch of potatoes, and it’s very hard to move them. Then when you come out, you’re exhausted.

BD: What about an outdoor audience?

WB: This week we did two performances outside in Grant Park, and it was absolutely lovely.

JM: Even on that rainy day!

WB: On the Friday, just the stalwarts came out in their yellow raincoats, and they sat there and they jumped up and down, and they applauded, and they were just great. I loved them!

JM: [Nodding] Yes, very much so.

JM: [Nodding] Yes, very much so.

BD: Are you constantly looking for new material?

JM: Oh, sure. I’m always interested. Even with all the research and reading I’ve done, there’s always new things you come across

— new old things. For instance, a dear friend of Bill’s [Peter Winkler] wrote a revue [_Professionally Speaking_] that got produced off-Broadway this season, and he showed us a song from this several months back before the show went into production. That song, called Tamara, Queen of the Nile has really enlivened our current program.

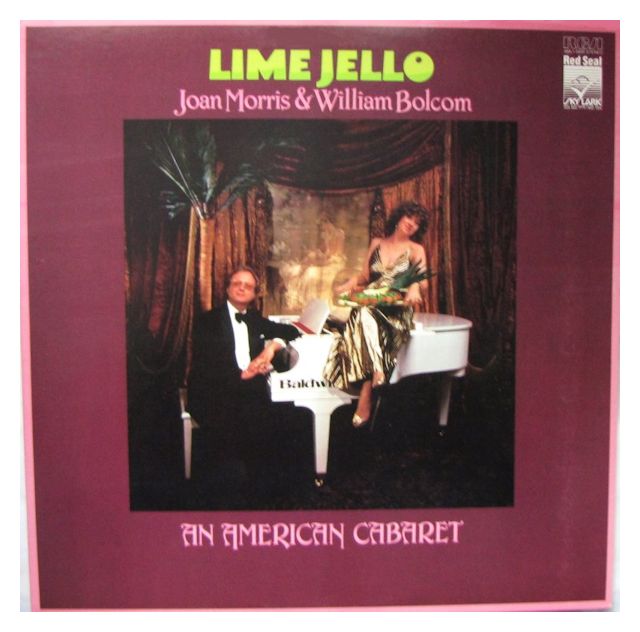

WB: In fact, that’s part of our new recording called Lime Jello. That is a song which I wrote for encores, and it really has been fun. We’ve done that encore, Lime Jello, Marshmallow, Cottage Cream Surprise, in halls all over the United States and Europe, and it always gets the same mad response. It

’s terrific fun to do, and that became the title of the album because people are always asking when we were going to record this thing. So we finally we did, with a collection of a lot of new cabaret-styled material by many of our friends and other people. Sheldon Harnick has done wonderful things over the years, and we’ve done three or four of his songs, as well as things by Winkler, Leiber & Stoller, and other people who are not as well known for that, like Dick Hyman, who is a wonderful composer as well as an arranger.

BD: So you’re not looking for just new ‘old material’, you’re looking for new ‘new material’?

JM: Yes, that’s right.

WB: As much as anything else, certainly. We tend to look for things that are not as well-travelled. We’ve never had any great desire, for example, for going into Rodgers & Hammerstein because lots and lots of other people are doing that. I don’t see any reason to beg comparison. On the other hand, when you’re talking about something like Gershwin or Cole Porter, which we’re hoping someday to record, it’s a matter of trying to find things that we really like, and not at the same time eschewing standards. Those are great things that are great and well-known because they really do deserve that.

JM: It

’s that way with all the greatest songs, even with classical pieces by Schubert or Brahms. They can stand the newest interpretation. Every artist brings their own special thing to it, and I hope that I bring something, at least one little spark of something to every song that maybe nobody’s thought of yet.

BD: Do you ever drop a song by Schubert or Brahms into your recitals?

WB: I have been known to do that.

JM: The year my voice teacher died we did some Brahms in New York in our program...

WB: In her memory.

JM: ...because she had actually played for Brahms when she a girl in Vienna. Once in a while we’ll do some Ives, b

ut, sometimes we get asked to do concert programs. For instance, we’ll do an all-Gershwin program in Pasadena, so there you make it special. Sometimes in Canada they love the old songs. It’s true, you don’t hear those as often as, say, Gershwin or Berlin, but that material is in our purview at the moment.

WB: Right. But we’ve done many anthologies on records. We just came out with a second anthology of Berlin Songs for Nonesuch. The first one was on RCA, and it’s something we like to do. We like to explore composers’ or songwriters’ viewpoints, so we look at everything we can find to see if there’s a whole record in there. We find their face after doing a number of songs.

WB: Right. But we’ve done many anthologies on records. We just came out with a second anthology of Berlin Songs for Nonesuch. The first one was on RCA, and it’s something we like to do. We like to explore composers’ or songwriters’ viewpoints, so we look at everything we can find to see if there’s a whole record in there. We find their face after doing a number of songs.

BD: Why is it that the two of you seem to be the only ones doing this kind of thing?

WB: Oh, I’m not sure that’s true. There are a few others around, and there are other people who are really fine artists who are known for other things, who have also done anthologies. There are some more now...

JM: These things have never completely died, but I know what you mean. There’s not the attention. It’s like ragtime. It takes a while for people to have the distance to look back at it and appreciate it, and understand the role it plays in our history, and that these things shouldn’t be allowed to completely die into oblivion. These are the tunes that are in the consciousness of us all, like ‘Wait ‘till the sun shines, Nellie’. Maybe the youngest kids that haven’t come across it, but it’s just part of our consciousness. It’s what shapes our language and the way we approach life.

BD: Do you want the audience that goes to a Michael Jackson concert to also come to hear your concert?

WB: Why not?

JM: Sure!

WB: It’s not uncommon. We’ll find people out there who are very big on all kinds of music

— omnivores — young people who have been fans of the one also like the other. People are cutting across in their tastes a good deal more than they once did, and I think that’s great.

JM: Old people come because,

“Oh,I remember that,” and the kids are, “Wow! That’s great.”

WB: Then they’ll come back years later, and they have gotten all those records. That’s when they ask really searching questions about this and that, particularly in places like Canada. They don’t just come back and tell you how much they like the concert; they tell you about their research on a particular person, or they’ll ask whether you know about such-and-such details. Sometimes they’ll be much more on the facts than we are. We forget! [Both laugh]

JM: A man in Interlochen told us a wonderful story about May Irwin one time. We do the ‘Frog Song’ of hers. She also introduced ‘After the ball’, and she was a favorite performer of Mark Twain. So we did one of these songs and he said,

“I have to tell you, I lived in one of the buildings she owned on Lexington Avenue! She was one of the few women who saved her money and took a lot of money out of Vaudeville. She had come to visit us after we’d moved in, and was chatting with us. She said, ‘My name won’t mean anything to you, but your parents knew me.’ As she was leaving, she said, ‘Well, boys, there’s only two things to do on a rainy day, and I don’t play cards!’” [Much laughter all around]

BD: In your composing, do you feel that you are part of a line, a lineage of composers?

WB: Oh, gosh, I don’t know. There are certainly composers whose music I respond to, and they range considerably.

JM: Ives maybe?

WB: I would say Ives, but I would say at the same time I feel very strongly connected with people like Gershwin, and Scott Joplin, and my teacher Darius Milhaud, and Alban Berg, and an enormous number of people who I respond to. I don’t know whether there’s any real sense of lineage. We’re not the Viennese tradition where Schoenberg could say that he was part of another tradition. You really have to understand him in that light to understand the music. We have never had a real absolute kind of tradition, but we do have a popular tradition which I’m very interested in and have always cared about, and that’s very much part of the background that we’ve had. One of the things that may make me unusual amongst American serious composers is that I’ve always been interested in incorporating all that, which in a way takes me back to the Classical Period. This is what you’ll find in Haydn.

WB: I would say Ives, but I would say at the same time I feel very strongly connected with people like Gershwin, and Scott Joplin, and my teacher Darius Milhaud, and Alban Berg, and an enormous number of people who I respond to. I don’t know whether there’s any real sense of lineage. We’re not the Viennese tradition where Schoenberg could say that he was part of another tradition. You really have to understand him in that light to understand the music. We have never had a real absolute kind of tradition, but we do have a popular tradition which I’m very interested in and have always cared about, and that’s very much part of the background that we’ve had. One of the things that may make me unusual amongst American serious composers is that I’ve always been interested in incorporating all that, which in a way takes me back to the Classical Period. This is what you’ll find in Haydn.

BD: Do you want your music to last? Do you expect your music to last?

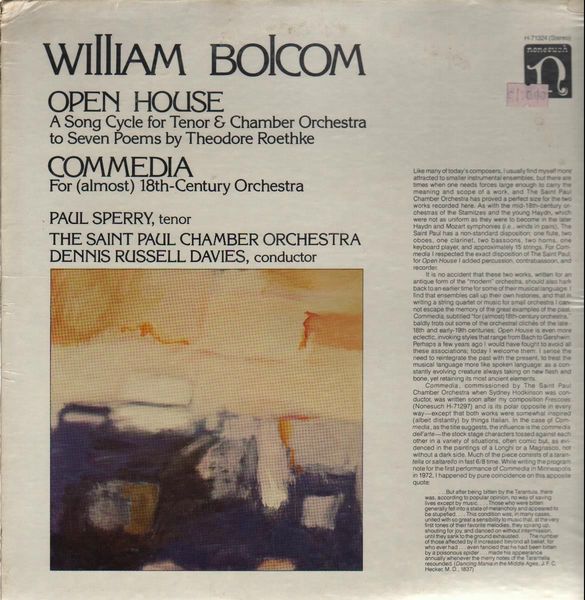

WB: I hope it does. So far, certainly it’s had a certain amount of longevity. I was just talking with one conductor who is going to be doing my Commedia in Brussels. That is an orchestra piece which has been played several hundred times, which is very unusual for a contemporary work. Much of my stuff which has been played gets played and played and played. For example, the performances here of the Songs of Innocence and Experience will be the fourth and fifth performances. For a piece that size that’s very unusual, and there are three more slated at the Brooklyn Academy in November [conducted by Lukas Foss], and there are other people who will be doing it, like the BBC, and the Philadelphia Orchestra. Those are not definite and the dates are still not clear, but with the luck this piece has had, they will be done. That’s an unusual thing and it’s very encouraging.

JM: When you were orchestrating all those years, and finishing the piece, you had your doubts.

“Am I ever going to see this piece done? It’s so humungous! Is there going to be a group that will really want to take it on?”

WB: Yes! And here more than one group has done it, and all from different venues. That’s what’s interesting. We’ve had a German opera house in Stuttgart, my university in Michigan, and here in a park concert situation. Then Brooklyn Academy of Music will have an entirely different thing because it’s going to be the Brooklyn Philharmonic with the Next Wave Festival, and that’s an entirely different way of doing things. So that’s in itself is very interesting, and very encouraging that it doesn’t have to be done just one way in one situation with one audience and by one kind of house.

BD: So let us broaden the idea even farther. Where’s music going today?

WB: Milhaud had a wonderful answer. He said,

“The history of music is the history of the music of the next great man or woman.” I think that’s pretty good. There was no absolute line. The one thing I would never want to do is predict anything, but I will say that I have noticed among younger composers— mine, or from other places — is that they are interested in a more inclusive attitude. I remember when I was their age it was an exclusive time. We had to be ‘atonal’ exclusively. There was a certain kind of attitude. Everybody was sure that tonality was dead. Well, it was not even sick! [Laughter all around] What has happened is that it’s been expanded enormously, more than we ever thought it could be. So we suddenly find ourselves with all this wonderful language you can use, instead of having to say you can only do this or you can only do that— which is a Nineteenth Century phenomenon. That was a period where there were new schools of painting, and new schools of poetry, but in music you had to do just one kind of thing, and say this is what it was. There was a certain canon everybody in the group agreed on, and we always had to say we were solidly against everybody else. We were going to be ourselves and impose our will on everyone else. Occasionally they do win the day for a while, and then that passes. It’s always been like that, and in the meantime, each one has something that they have left for us. Nowadays, all you have to do is simply say this was an exclusive phenomenon rather than an inclusive phenomenon, where you have something new that you can add to this enormous amount of language that we are approving. We can do so many wonderful things now that we couldn’t do a hundred years ago in music. One of our problems has been to box ourselves in with some sort of attitude.

BD: Is this the advice you give to the young composers?

WB: I see composers who try to deny some part of their background. I would say a good half of my students at the University of Michigan are ex-rockers, and there are an awful lot of them in other schools, too. Most of them are trying to just say good-bye to that whole life, which I can understand. It’s very bad with all the drugs and everything else, but at the same time it’s part of their lives. It’s part of their background, and it would be silly for them to deny all that whole big hunk of their lives because there’ll always be tripping over it. I say to them that they’re going to have to come to terms with every part of their life because if they don’t, at some point it will come bang, right up in their face and they won’t be able to deal with it in any realistic way. So what I try to do is find a way for them to integrate their own lives with their own experience, because when they do this, they will end up with something that is truly theirs.

BD: [With amazing foresight, considering the productions yet to come in Chicago!] Have you written an opera?

WB: I’ve written two operas for actors

— Dynamite Tonite and Greatshot — with the same librettist, a fellow named Arnold Weinstein, and just now we’re starting on a third one called Casino.

BD: What is an ‘opera for actors’?

WB: It is an opera where actors sing instead of singers sing! That was twenty-some years ago, (in 1961) my gosh! It was called Dynamite Tonite, and won a lot of awards. It kept getting revived, although it never made any kind of success on Broadway. It got to be known as

‘the flop that wouldn’t die’ because the same people would come back and revive it. For several years it became a kind of reunion. All the people would somehow get out of their old jobs, and come back and sing it anyway because in the believed in the work. Today I wouldn’t necessarily have to do that the same exclusive kind of way.

BD: Why do you call them operas? Are they not really Musical Theater?

WB: Because in an opera you sing all the time, and these people sang all the time. They weren’t structured like a musical comedy at all. They were really structured like an opera but they sounded lighter. They were operas in that sense, but the people who sang them were actors. The reason I wanted to use actors instead of the singers

— particularly twenty-five years ago — was that in those days, singers almost exclusively trained in what you might call ‘singer-ese’, or as Luciano Berio once put it, ‘British-Italian’, in which you have some sort of an attempt to put in Italian pure vowels and over-emphasize British consonants, which ends up sounding like gibberish. You really can’t understand it at all. It sounds like Esperanto, and I was terribly concerned that somebody understand what’s being sung. This is the kind of thing that was just assumed as a possibility in every musical culture, and everybody accepted it. Today we have gotten so inured to the idea of not being understood that people just decide to simply to go ahead and set words any way, and I think that would be a very academic exercise. I was interested in being understood, so I put up with the roughnesses and occasional mistakes that an actor would have because I wanted the reality of the actor’s presentation. Also, I like the variety of the actors’ voices. I love the fact that everyone sounded like themselves when they sang and talked — if they did have to talk. There wasn’t that big schism between their speaking and their singing voices that you find in so many singers. Today, many singers have decided that it’s time for them to work up their own kind of diction. One of the encouraging things that happened here at Grant Park was that I could understand most of the singing. They used diction that was really American. That was true with the chorus, and really was an attempt for Americans to sing to other Americans. When we do it in England on the BBC, then of course it will be British, and it will be ‘Britishers’ singing to other ‘Britishers’. They’ll be using their accent, which is absolutely legitimate, but I don’t want them to sing as British-Italians.

BD: [To Joan] Do you work terribly hard then at your diction especially in the popular songs?

BD: [To Joan] Do you work terribly hard then at your diction especially in the popular songs?

JM: I’ve always worked on it, but not so much on the diction itself as I take every piece as an acting piece. I take every song apart, put it in my own words and ask,

“What is the message? What am I trying to say?” I make sure when I go back to the real words that I’m getting the message over to the people; that they understand the story. How are they going to laugh if they can’t understand the words of a joke, or be touched if they don’t know exactly what you’re describing? I can’t imagine getting up there and not wanting to be understood. I don’t have a voice, just as an instrument, that can knock them dead in the aisles, so I emphasized my strong point, which is to appeal not only as beautiful sound. I use my voice as an instrument.

WB: But your diction is one of the things that people always remark on.

JM: Oh, it’s true, they do, but then I say to them that nobody says Frank Sinatra or Elvis Presley has great diction. It’s just taken for granted in popular music. Where did it ever get accepted that when you get up on the stage in opera you don’t have to convince people the same way just because it’s a familiar story?

WB: Which is exactly why I used actors all these years! Now I’m suddenly encouraged by the younger performers more. I can understand them, and that’s a new thing so that the new opera will actually be using both actors and singers. I’m interested in that, too. Just as what happened in the plays, I used an enormous variety of types of voice, and that’s interesting to me. We have this now. We don’t all sound the same.

BD: You’ve done many popular songs by these various composers. Would you ever get involved in a full-length show by any one of them?

WB: It might be a very interesting idea. Certainly, revivals would be interesting. Our friend John McGlinn has been making something of a career reviving older musicals, and has done this all very well. We might do that. There are lots of things we’d like to do, especially when there’s interesting material. We always look at the actual material. If it’s wonderful and we really want to do it, fine, but I don’t just want to do a show just to do a show. It’s got to be a good show.

JM: This August, in Charlemont, MA

— at the Mohawk Trail Festival, which we’ve done almost every year for the last ten years — Sheldon Harnick will be composer-in-residence. We’ve gotten to know him a little bit, and we will work on a lot of his material to showcase it.

WB: He composes as well as writes lyrics. He’s a real musician. He played the violin for many years, and was trained as a musician here in Chicago. He got a music degree from Northwestern, so he’s really a local product. He

’s a very nice guy, and extremely articulate, and I think he’s the best lyricist around. He’s just marvelous.

JM: In fact, we had three of his songs on our new album, Lime Jello. One is The Boston Beguine, for which he wrote both words and music, and two that he wrote with Jerry Bock. One is called _Artificial Flowers_from Tenderloin, and one is ‘_Just a Map_’...

WB: …which was cut…

JM: ...from The Rothschilds.

BD: Do you look for songs that are cut out of town?

JM: Sure. We look for whatever’s good, and often as not we’ll talk to the writers themselves. We will ask,

“What do you like that hasn’t been recorded? What would like to have done?” That’ll elicit a whole kind of marvelous response. People are crazy to have things they thought were terrific that got lost. They’d love to have them shown, and we’ve had a lot of fun, for example, with Leiber and Stoller, who are very old friends of mine. One day I walked up to their office and said, “What do you want to have us do that we haven’t seen or heard?”, and one album came out of that.

BD: Thank you for bringing your music to Chicago

WB: We hope to continue!

We now move ahead six and a half years, to November of 1992, for a further conversation with the composer alone . . . . . . .

BD: You’ve just completed McTeague, a huge work for Lyric Opera. I assume you consider this a huge work?

WB: It’s a good-sized one, probably bigger than Songs of Innocence and Experience. I wanted to have a full evening but a tight show. I didn’t want a three-hour opera, so we’ve actually ended up with one that’s two hours of music, and that seems big enough for me, considering the way we handle the story.

BD: Big enough for you as the composer, or big enough for the audience as listeners and viewers?

WB: It depends on the story. Some stories require longer time in telling. This was a full-scale nineteenth century novel. It came out in 1899, and became a nine or ten-hour movie [made in 1924, directed by Erich von Stroheim] called Greed. No one knows how many hours it really was.

WB: It depends on the story. Some stories require longer time in telling. This was a full-scale nineteenth century novel. It came out in 1899, and became a nine or ten-hour movie [made in 1924, directed by Erich von Stroheim] called Greed. No one knows how many hours it really was.

BD: A lot of it’s lost, unfortunately.

WB: Yes. The story I hear was that it all was thrown in the Catalina Island sound somewhere, and the fishes have probably eaten it up.

BD: [Wistfully] Wouldn’t it be interesting if they found the film-cans and they were still sealed?

WB: Wouldn’t it be wonderful! I’d love to see it all some time. My exposure to the film, which was coming from the novel McTeague, is probably one of the reasons I was interested in this particular story. I was very impressed by the story in the movie... what there is left of it! It may be a mess as far as everything is concerned, but there’s some very powerful moments in it, and the ending is very strong.

BD: Regarding the size of the work, aside from the obvious differences, what are the main changes that go through your mind when you’re working on a huge work as opposed to a shorter work, or even just a song?

WB: It depends on the work that you

’re starting with. Some pieces call for a multifarious approach. There are things I’ve wanted to do that would require a very varied approach. Here, despite some of the critical comments — they had troubles dealing with the various styles, which is their problem not mine, and obviously not the audiences, either — over time people are beginning to realize that this is what I do and that’s how it is. I have probably used fewer types of molds — or if you’d rather call them styles — than in something like The Songs of Innocence and Experience, which was done here six years ago at Grant Park, and will be done this month by Leonard Slatkin and the St. Louis Symphony, both in St. Louis and New York. That work has forty-six poems by William Blake and is a group of poems that are extremely varied in approach, and therefore they are many different situations. Here in McTeague, we have a novel which is full of all kinds of subcharacters, and a truncated film, but underneath it all is a very simple, straightforward story. Our approach — Bob Altman and Arnold Weinstein and myself — was to reduce it to this fable kind of level where you’re really telling a story that is as tight a Grimm’s Fairy Tale. We really did cut down on the number of characters and sub-plots and other things that could be found in the book and the film, so it came out to the right length. As operas go, this is rather a short one.

BD: Two hours, with one intermission?

WB: Yes, it’s a nice length. It’s certainly right for this work. We could have taken the opposite approach and try to pick up every single thing in the book, which is what the movie Greed did...

BD: … or tried to do!

WB: Right, and probably did do, but we’ll never know because so much of it is lost. I have seen a book of stills of all of the scenes that were shot, and you have an idea of the enormity of the enterprise. It showed terrific ambitiousness.

BD: Should someone with a computer take the stills and remake it into a nine-hour film? [

In 1999, Turner Entertainment created a four-hour version of Greed_that used existing stills of cut scenes to reconstruct the film_.]

WB: Why??? Leave it as it is! Even the truncated thing is still wonderful in its ways. Would you like to put the head back onto the Winged Victory of Samothrace in the Louvre? There’s a point where somebody decides that the part of what is left to us has been left to us because of the situation. I don’t think it’s necessarily right that it should be all that’s left by fate. Monteverdi wrote forty operas, and we have just two or three of them. That’s all there is. I’d love to know what the other thirty-seven are like, but they could not possibly be reconstructed by computer.

BD: Suppose we have some kind of atomic destruction here, and all that’s left of McTeague are a couple of scenes. Would you want someone to go back and reconstruct it from a broadcast tape?

WB: No! I used to think it was a good idea to reconstruct things. I finished an unfinished Schubert sonata, and I actually finished one of the Iberia numbers of Albeniz which he didn’t finish himself. They’re perfectly all right as ‘finishings’, and it’s all right if you want to put them in concert for people who need to have everything finished up, but I wouldn’t do it today. I don’t think I did such a bad job, as it turns out, on the C Major Sonata of Schubert. Krenek also did the same thing, but I never compared his finishing to mine.

WB: No! I used to think it was a good idea to reconstruct things. I finished an unfinished Schubert sonata, and I actually finished one of the Iberia numbers of Albeniz which he didn’t finish himself. They’re perfectly all right as ‘finishings’, and it’s all right if you want to put them in concert for people who need to have everything finished up, but I wouldn’t do it today. I don’t think I did such a bad job, as it turns out, on the C Major Sonata of Schubert. Krenek also did the same thing, but I never compared his finishing to mine.

BD: It would be interesting to see if you arrived at the same place. [_Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my interview with Paul Sperry._]

WB: I rather doubt we did. In fact, I did see something that seemed sort of prolix and kind of meandering. I tried to do something closer to what I thought was meant, but whatever happens, why do it? We have lots of other things that we could finish, and if something has gone from the past, then that means there’s more room for something new to come in its place. Maybe our nineteenth and twentieth century pack-driven mentality is so over-populating our artistic universe with such an awful lot of wonderful things that there’s no room for new thing. It may be possibly understandable that there were some terrible holocausts, and that left the remaining humans room to reconstruct their own culture. Maybe a few shards and pieces of pottery and odd things are left over from theirs, but it won’t be the first time it’s happened after all.

BD: We’ve a few relics, but otherwise we have to start over?

WB: I can’t worry about all that.

BD: Is there too much music around?

WB: No, there’s simply people who don’t listen to it, which makes it too much music because they put it on all day and never really listen to what they have going on all day. So it becomes a kind of drug. There is too much music than requires thorough listening, but I can’t really say that there’s too much music. I’m simply saying there aren’t enough listeners who really listen.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] So you expect your audience who comes to hear your piece to really listen?

WB: I hope they will! You do what you can to make them do that, or at least induce to do that, but you can’t make them do that. I always think of that line from William Blake where he says,

“I give you the end of the golden string, only wind it up into a ball.” A lot of people might see the end of the golden string being tendered to them, but the actual effort of winding it up into a ball may be more than they’re ready to do. They may have it all thrown at them, and there’s only so much you can do to get them to do that winding.

BD: Should your music be for everyone

— the ones who wind and the ones who don’t wind?

WB: I give it to anyone who wants it, and that’s what anybody who writes, does. If they get it, wonderful! If they don’t get it, also wonderful! I certainly don’t make it difficult for them, but I’m not going to give away all of the marbles either.

BD: Do you have the audience in mind while you’re writing?

WB: I have myself as the audience. I can’t figure out what they want, but I do imagine myself as audience, and have to assume that there is a certain constant between me as audience and them as audience, and it usually has worked as far as timing. I do know that there is somewhere a sense of relationship between myself and an audience. I like very much what Yo-Yo Ma says about a kind of circle, that it is almost an electrical current that goes between the performer, the work and the audience. So you have the piece, you have the performer, you have the audience, and you get a circuit going, and the whole idea is to keep that circuit going. That’s something you can deal with. You can sense when the circuit begins to flutter, and you can sense when the circuit is overloaded. You try very hard to keep a certain control over the electricity so that this constant thing keeps going.

BD: Without it just becoming feedback?

WB: That’s right. You have all kinds of means of doing it, but the point is you do try to keep a relationship going. That’s why it’s very important for people who are writing or composing to have at least some very deep sense of what it is to perform. Through circumstance, serendipity, or whatever, I have continued to perform in some way or another through most of my composing life, and I’m very thankful for it because it does give one a certain sense of timing. It might make it less mysterious to an audience than if I had not stopped performing, and that might make it very difficult for critics to deal with because they don’t have any need to have to deal with their usual self-imposed notion of having to be translator for the audience

WB: That’s right. You have all kinds of means of doing it, but the point is you do try to keep a relationship going. That’s why it’s very important for people who are writing or composing to have at least some very deep sense of what it is to perform. Through circumstance, serendipity, or whatever, I have continued to perform in some way or another through most of my composing life, and I’m very thankful for it because it does give one a certain sense of timing. It might make it less mysterious to an audience than if I had not stopped performing, and that might make it very difficult for critics to deal with because they don’t have any need to have to deal with their usual self-imposed notion of having to be translator for the audience

— which I don’t think they do terribly well half the time because most of them are not able to read music! A very simple case in point is that 187 critics have come to McTeague, but only twelve asked for the vocal score.

BD: Is that a good thing or a bad thing?

WB: It means they really don’t know music. They know records. They are

‘record-heads’, and that’s perfectly okay. I have nothing against ‘record-heads’, but they’re not critics.

BD: Or are they coming without the vocal score because they are assuming they should see what the audience sees without any help or crutch?

WB: Then why don’t they become audience themselves? If they learn how to be audience, they’d be better critics.

BD: [Playing Devil

’s Advocate] If they saw the vocal score, then they might see something they could understand more than an audience member who hasn’t seen the vocal score.

WB: That’s what the vocal score is for, and if they’re able to read music, they could understand it a little bit better and come with a certain amount of information. But they can’t read music, so they have no right to talk.

BD: So the whole audience should get vocal scores??? We should have 3,600 vocal scores in the lobby for them?

WB: No, I just say it is a matter of what you decide. When you decide you can set yourself up as a critic and impose yourself as such, you’re taking on certain responsibilities. If you’re going to do that, then you want to have the credentials to do it, and I don’t actually honestly believe that most critics who are setting themselves up as critics have those credentials.

BD: Should we get rid of critics?

WB: No, I want good ones. I want those who know something. It would be analogous to having criticism in the field of English literature by people who couldn’t read, and I’m afraid that’s the situation we have. If you’re going to take on the job as a translator, or an introductory person to people who are asking you for this kind of information, then you have a certain responsibility. In a way you’re a teacher, and maybe that’s the whole point of it. It also is possible that people who start out as critics, particularly in Europe, used it as a way to break into the literature field. Don't forget about most of Shaw’s criticism when he was a young man. It was a way for him to break into print, and how many others can you think of as the same case?

BD: Corno di Bassetto! [Bassett Horn, the pen-name Shaw used.]

WB: Exactly, and Debussy wrote criticism as a young man, too. Tchaikovsky did it for a while, and then other people did. It was something you did as a young person to give yourself some sort of an introduction.

BD: Schumann also did it.

WB: Yes, but he also was interested in continuing the whole publishing notion, which was informing. He looked at it as being a teacher. He was very much a teacher. He thought of it as teaching. I don’t find too many critics today that think of their own job as teaching. They tend to be basically opinion-mongering, and I don’t find that very interesting, even from the ones who were kind to one’s music. I would rather see a situation where they really took the time to do it. Unfortunately, that’s partly the way things are today. One has to criticize, which is say at least review six or eight concerts in a week, and that’s an awful lot for anybody to do. Naturally, or eventually, inevitably you find yourself going towards short-cuts. How can you not?

BD: Let’s get off of the critics...

WB: Yes, let’s leave them alone. I’d much rather not think about them.

BD: ...and come back to being a composer. You were talking about writing for yourself. Have you figured out what it is you want, or is this a constant learning experience for you in finding new things that you want?

WB: I’d be more likely to accept the latter because otherwise I’d have it all decided and there’d be no reason to go on. You’re always trying to find out what you want to do next, and the thing eventually introduces itself to you. You try to keep yourself aware of those things. There’s a lot of work involved, and it always changes. Five or six years ago I didn’t know I’d be writing this opera. But now I have done it, and there it is, and it’s on the boards, and people are singing it and playing it, and I have to go onto the next thing.

WB: I’d be more likely to accept the latter because otherwise I’d have it all decided and there’d be no reason to go on. You’re always trying to find out what you want to do next, and the thing eventually introduces itself to you. You try to keep yourself aware of those things. There’s a lot of work involved, and it always changes. Five or six years ago I didn’t know I’d be writing this opera. But now I have done it, and there it is, and it’s on the boards, and people are singing it and playing it, and I have to go onto the next thing.

BD: When you’re sitting down at the paper and it’s essentially or completely blank, and you start writing notes, are you always controlling your hand that’s putting the notes on the paper?

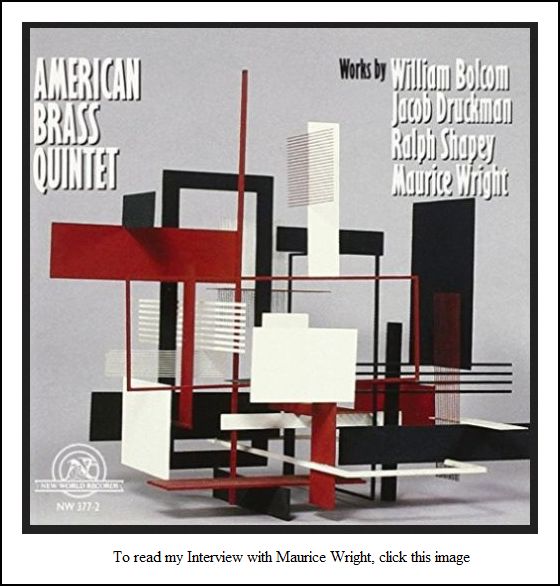

BD: The hand never controls you? [_Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my interviews with Jacob Druckman, and Ralph Shapey._]

WB: No, but the piece might control me. It’s the movement of the hand, isn’t it? Once you start a particular animal going, it reveals itself to you, and you have to listen very carefully to what it wants to do. But at the same time, you have to keep your control. It’s like a horse and rider. There are some relationships like that. Sometimes you’re a horse and sometimes you’re a rider, but there is a relationship, and that is how it’s done.

BD: Are you ever surprised by where the horse will lead you?

WB: Occasionally, but then I have to take the lead and say maybe this is what it is. I think half of my composing has been,

“Oh, my God, is this where’s it leading? Oh, right. I’ll go with it.” That, of course, is great excitement and surprise, and also it tends to bedevil our friends the critics, of course. [Both laugh] I no longer seem to fit with their notion of what I should be doing.

BD: Does a piece ever say to you,

“Oh, my God, where have we gotten???”

WB: Occasionally, and then sometimes I have to find where I am. Then I spend time getting myself out. So you just backtrack and go back to where you were. But in the end, I have loved the idea of when the mind goes and takes leaps that you never have imagined it would take. That’s when it gets to be fun.

BD: When you’re tinkering with it and you put in the double bar, how do you know when to stop, when it’s done, when it’s ready to be launched?

WB: It sort of tells you, but there is also an awful lot of experience and technique, and I do very strongly believe in the technique. It’s not a very bourgeois notion because novels and movies have this idea there’s some sort of weird spiritual thing is going on, like angels singing to you. One of the fun things is to collect the notions that people have in movies about how tunes come to composers. They’re very funny. In many cases, angels sing them to you as they float by, and they’re always absolutely off the mark. That’s not how it happens. It never can be the way it happens.

BD: Can you explain how it happens?

WB: No! [Both laugh] I would certainly not want to even if I could because it would be the kind of thing that one would have to keep as a secret. But I don’t think you can explain it. It’s one of those things that has to do with the machinery that is going on in the mind, which, if it were explicable, would then be words. That’s the whole point. We’re dealing with a new language which has its own rules, and they tend to reveal themselves to you over time. But I do believe that you acquire the ability and the means of setting down exactly what you want, and that is what I would call ‘technique’.

BD: Do the rules evolve over time?

WB: Constantly.

BD: So when you discover a rule, was it not a rule but just a very temporary waystation?

WB: That’s sort of it. The next time around you’re talking about the next one. Once it becomes case-hardened a rule, there has to be a really major dynamite blast or two to push things out of that situation. Most of the early part of the twentieth century was trying to get rid of rules, for they had become a very codified harmonic style. So people did all kinds of dreadfully anti-establishment moves for a lot of plain, simply draconian anachronisms to blow things up. [This was probably the reasoning behind Pierre Boulez

WB: That’s sort of it. The next time around you’re talking about the next one. Once it becomes case-hardened a rule, there has to be a really major dynamite blast or two to push things out of that situation. Most of the early part of the twentieth century was trying to get rid of rules, for they had become a very codified harmonic style. So people did all kinds of dreadfully anti-establishment moves for a lot of plain, simply draconian anachronisms to blow things up. [This was probably the reasoning behind Pierre Boulez

’ s published remark, “Opera Houses? Blow them up! ” , which actually got him into serious trouble with the police some years later, as can be seen in the interview.] That’s fine, and we had to do it. It was one of the necessary moves of getting out of what would have otherwise been a kind of super-Richard Straussian kind of harmony taken to its final destination. We had to throw all that out, and then we came back to find what survives. There is a certain amount of that which happens, particularly in music, and some people have said that ours is the longest Mannerist Period in the history of art — which is most of the twentieth century. Now we’re in the process of finding out what is viable in all of that material.

BD: Who decides if it’s viable

— the composers, the public, who?

WB: The composers in the end, but the point is that the composer again is part of the circuit. There you are with the performer and the composer and the public, and when you get that machinery and electricity going, then we have something that has a real viability. The validity is that the current moves. It working and we are making a connection. It’s the kind of thing that absolute bedevils any critic because they are often looking for rules, and there aren’t any.

BD: No rules at all?

WB: The rules impose themselves as the piece progresses.

BD: Are they the same new rules each time?

WB: I’d have to say the same thing. They are things that would be parallel to what you might call grammar and syntax, and any kind of language function. Those things continue. They are tendencies, and they tend toward comprehensive ability, and they have a certain atmosphere about them. But you don’t write the literature out of grammar. Grammar guides you toward a certain discipline and comprehensive ability, but it does not generate what you’re writing about. It makes it possible to communicate to someone else in a clear way, but it does not create ‘the idea’. The rules will not generate anything. No system nor little notion will save you. We’ve had a pile of them in the last century or so, yet at the same time this or that system or procedure can generate a discipline, which can help you hold what you’re doing and bring to it a certain level of control. But that’s another story. Then you’re making the rules, or, if you want, the tendencies or the syntactical phenomenal to work for you. But they will not generate the idea.

BD: So once it’s all written down, then you can look back and see what rules were used?

WB: You might notice tendencies. I do notice sometimes that I will find a piece that will generate certain things.

“Oh, is that what I’m doing?” I always tell my students to ask themselves, “What am I doing?” Look back and take a look at what you are doing. Don’t do it in such a way that you’re going to inhibit yourself, but once in a while take a good hard look at what’s happening in there, and be as objective as you can. Then go back into the piece again. That way you have a certain sense of what’s happening. Yes, there is definitely a kind of syntax that grows out of every piece. It is slightly different in every piece, and sometimes it’s very different, but you have to have a mixture of self-awareness and total heedlessness.

BD: That way you know what you are doing?

WB: Sure.

BD: Then my question is, why are you doing it?

WB: Because I can’t help it! I’m a composer! [Both laugh]

BD: Here is a more general question but aiming at the same target. What’s the purpose of music?

WB: If there were a purpose, then we should all just throw up our hands and do something else. Its purpose is itself. You do it because that is what you do. I think of art as a big totality. If there was a nice, interesting, simple answer to it all, then there’d be no reason to go on. Once you figure out the purpose then you might as well say,

“Okay, fine, QED, let’s go onto something else.” I can’t do that. If I could explain it to myself then why should I bother go on? I’m not pretending to be dumb but I’m simply saying that the thing in itself is its own purpose.

BD: Then are you always searching for it?

WB: Of course! Well, I’m not necessarily searching for the purpose, I’m searching for the next piece. This happens to be what I do but, as I said, I cannot help doing. Anybody who’s a committed artist and this kind of person would probably, often as not, be perfectly happy to be able to pull the whole thing over and forget about it. It’s only amateurs’ block to the artists. You can’t help with it if you are one, and it would be very nice to be able to get that burden off your back, but you can’t help it. There you are, you’re doing it, and the darn thing has its control over you, but you can’t wait to get back to work.

BD: Are you glad for the burden to be on your back?

BD: Are you glad for the burden to be on your back?

WB: I have no choice.

BD: So you’ve made a friend of it?

WB: At least I’ve made some kind of a roommate.

BD: [Laughs] Roommates can be co-operative, or roommates can be irritating!

WB: Oh, I can’t kick this one out. It’s paying the rent! [Both laugh]

BD: [With a gentle nudge] Oh, come on... composing is more than just your job!

WB: It is always a job. Probably it’s the most labor-intensive of the arts, although if you talked to any artist they’ll always tell you that every one is labor-intensive. When I think about the amount of time it takes to write the notes of an orchestral score, just to be finished with one minute of music, especially with the whole orchestra on full tilt, I would be very surprised that the same amount of work would be put into pretty much anything else. In his autobiography, Aaron Copland is complaining about the same thing

— that no one else seems to understand the amount of sheer drudgery that goes into writing the score.

BD: Is it not true that every note gets its little moment?

WB: Every note gets its little moment, but it’s a very small moment. I’ve written millions of notes. Any composer who has ever been a professional has written millions of notes, and they all have their little moments.

BD: But every little moment becomes a sound at some place in performance.

WB: Sure it does, and that’s what you’re doing. You’re dealing with putting together all these sounds. That’s the way it’s done. That’s what’s known as being a composer

— you’re putting things together. That’s what the word means.

BD: You noted earlier that you have taken a lot of these styles and put them together. It seems in your music that instead of being a ‘soup’, it’s much more of a ‘salad’.

WB: I don’t know what you mean.

BD: In a soup everything melds together and becomes one homogenous entity, whereas each item in a salad retains its own distinct character.

WB: Oh, I see. It depends on the piece. I’ve made soups and I’ve made salads. [Continuing the metaphor] I’ve made casseroles and I’ve made the kinds of pieces that I can cook and serve as a reasonably extensive repertoire of recipes. It depends on what the occasion calls for.

BD: With your notoriety, you must be inundated with requests and offers. How do you decide which ones you will accept and which ones you’ll turn aside?

WB: If they’re interesting artists, that helps. If they have enough to pay for my time, that definitely helps because my time is valuable and I only have so much of it, so you tend to husband it. But things tend to work out that way. I’ve done things for nothing, I’ve done things for lots of money, and I put the same care into both. It’s just that you do have to at least somehow try to make a part of your living in this process because there’s an awful of labor-intensiveness. When I think back at the actual number of notes that went into McTeague, and if I counted the money I was paid, I would say it probably came to about a dollar and a half an hour, which is way below the minimum wage.

BD: So obviously you’re getting more than just the dollars in your pocket.

WB: Of course, because I’m sure there’d be ways to make a heck of a lot better money for less work, but what can I say? That’s what I picked to do, and it

’s a good piece. I never really thought seriously of doing anything else. That’s what I do.

BD: You seem to have contradicted yourself. You say you picked to do it, when I thought it picked you.

WB: I did say that, really. It picked me. I really have had no choice. I was always going to be a composer, and I can’t remember ever looking seriously at doing anything else... except, of course, being a musician, which I am. I’m also a pianist. I’m an accompanist for my wife, Joan Morris, as one of my major, major things in life, and I’m a professor. I teach composition to budding composers

— which is something that is really essential, but impossible. You really can’t teach it, but what you can do is help the students. You can guide them a bit. You can at least open doors for them, but you can’t push them through.

BD: What are the main things you see coming off the pages of your students?

BD: What are the main things you see coming off the pages of your students?

WB: They come out to a place like Michigan because probably we have a reputation

— not only me, but my colleagues have been very open to many American vernacular styles. My colleague, Bill Albright, has been very involved with Ragtime, and Michael Daugherty, who is new with us, has been involved with Rock and also with the various popular electronic things. But all of us have very strong classical background, and this the armature on which everything was hung. So we do essentially what has happened throughout the ages, which is to say an amalgam of popular and historical and classical styles, to put together a structure that will be comprehensible and also have the resonance that you wouldn’t have had without that background. I don’t think this is very different from the mandate of any composer throughout the history of music. Palestrina put little pop tunes of his day in his ‘cantus firmuses’, and Monteverdi took popular styles and popular dances and put them into an opera which was meant to have been a revival of the ancient Greek tragedy. You can call case after case of opera styles that have been put in and subsumed into a larger structure throughout the history of music. I find what I am doing is exactly that.

BD: Has it changed a bit now that it has gotten away from being a toy of the aristocracy, and being for everyone?

WB: I don’t think it was ever really a toy of the aristocracy. In the strictest sense it was for everyone, however, the audience changes. The aristocracy could pay for it for a while. Later you had subscription concerts, from the eighteenth century onwards, where other people started to pay for it. Later it became a tool, if you like, or a toy of the button manufacturers in the beginnings of the bourgeoisie. Every one of these people helps pay for the continuation of something which is essentially, in some weird way, non-profit. It’s because they truly want it, not because it’s going to make them any money. Nowadays, once the composer or the generator is gone you could put the work into a museum of one kind or another. It could be an art museum where you hadn’t to pay any longer because it’s past any kind of royalties. You can do the same thing to an opera house or a symphony orchestra because these fellows are long gone. There’s no estate to worry about, and they’re going to have a grand old time playing. One of the reasons people concentrate on older music is that it costs less to make. You don’t have to pay the living guy, who’s a pain in the rear because he keeps making things tough on you. He keeps wanting to correct your notes; he has definitely no sense of style; he’s an irritant. It’s much nicer to deal with older folks, and you can get scholarly conferences to talk about historical accuracy, and have Historically Informed Performances which follow metronomic markings, which any composer will tell you are not trusted. Nowadays, people are organizing whole aesthetics around what Beethoven might have marked in a particular movement, where half the time, I’m sure, the metronome wasn’t working properly. Schumann’s hardly worked right, and I know I’ve done with a broken one for years!

BD: How accurate do you want your music to be when it’s reproduced?

WB: I want the same current between performer, the audience, and the artists. True artists find their place in that community of electricity, that circle which Yo-Yo Ma talks about so well. A really good performer will perform accurately

— sometimes more accurately than I’ve written it!

BD: [Mildly shocked] How can that possibly be?

WB: Because, for example, tempo notions tend to develop and settle themselves when a really good performer who is on that track gets in there. Dennis Davies was able to say,

“No, that wasn’t the right tempo, this is the right tempo,” and when I heard it I had to admit he was right and I was wrong. I wrote down the wrong one.

BD: Has he figured out what you really wanted?

WB: Yes, because we’ve been on that circuit for a long time. I’ve worked with this man for twenty-five years.

BD: Earlier you said that if some of a piece is lost for some reason, you don’t want it re-created, re-established, but how much re-establishing do you expect from the score while it’s there?

WB: We’re not talking about the same thing. You’re talking about finishing out the fragments of works. We were talking earlier about that, and it’s not the same thing. Any piece of written-out music is an imperfect transcript of what the music is supposed to be because our notation is severely limited. It’s pretty good in many ways, but it really does not impart the notions of style, particularly if we’re talking about something like Popular Style, which was essentially what people used to always equate as the style. People talk about the eighteenth century ‘notes inégales’, the unequal notes. How do you play Couperin or Bach, or something like that? This was, in a way, very analogous to popular styles that everybody knows. How’s the Shuffle been played? Do you play Ragtime with absolute equal sixteenths? When do you bend and when do you not? This is where you have to keep that circuit going between Performer, Audience and Piece, and as long as the cycle is going, that’s going to be imparted to somebody else. This is what tradition is about!

BD: So does your piece get better and better as it’s performed more and more?

BD: So does your piece get better and better as it’s performed more and more?

WB: Until people lose the thread, and I’m afraid to say that in many cases with the classical repertory we probably have lost the thread of performance style in many cases. We’re dealing with a kind of torso of what it might have been.

BD: If we’ve lost the thread, should we go and find the thread, or should we just abandon it completely? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my Interview with Libby Larsen.]

WB: Well let’s at least try! Often as not you find it in popular styles. When I was hearing the old archive recordings of Monteverdi operas , which were perfectly deadly dull renderings of what was written down, everything was just people following all the half notes and whole notes, and generally plunking along with this rather pedestrian style because they were playing what THE NOTES

said — as Eubie Blake used to call it.I just knew this was wrong. One day I was taken to a coffee house in Florence where a fellow was sitting there improvising a kind of sing-song over the events of the day. He was accompanying himself on the guitar, and I said to myself, “Hoo-ee! This is Monteverdi in recitative!” It was probably way before Monteverdi, and they picked up the style. If you want to find out how the old styles were, look into popular sources. There’s a very interesting record we put out in the Explorer Series when I was working at Nonesuch called Folk Fiddling from Sweden. It’s full of quadruple stops, and it has a wonderfully raw sound about it that can be compared to the Bach Partitas and Sonatas for unaccompanied violin. You see enormous numbers of parallels. If you want to have some sense of what it might sounded like in Bach’s day, listen to that. In other words, the popular sources will continue this kind of relationship, often longer than you’ll find in conservatories. So there are sources, and you can find them. About three or four years ago, The New York Times was despairing, talking about how Charles Ives was over-rated, and everybody was checking their hands about how to play it. These were conservatory musicians trying to get a handle onto Ives. Well, for heaven’s sake, there is the whole Gospel tradition, and the whole popular music traditions that Ives grew up with, and this is very much extant. Go look at that and you’ll have a better idea of how to play Hello, my Baby in the middle of Central Park in the Dark!

BD: And even the marching bands that just go by in his works!

WB: You bet, it’s all there! All you

’ve got to do is look at it, and find that part of you that responds to it. Then you can keep that circuit going. Many people are very puritanical about it and don’t know how to bring it off. They try to do it in some sort of prescribed conservatory notion, and they’re missing the whole point of Ives.

BD: Despite all of this, are you optimistic about the future of music, (a) composition, and (b) performance?

WB: In general versus being pessimistic about it? Anybody reasonable has good reason to be pessimistic about anything. We have a terrific number of horrible problems as a planet that we’re not really hurrying towards resolving, so I don’t know why I should be any more optimistic about the future of music and performance than I should be about the future of the world. I feel we’re on a terrible collision course, and we have a very good chance of screwing the whole works up. So why should I be any more optimistic about the future of music?

BD: So you don’t expect your music to last two hundred and fifty or three hundred years?

WB: I don’t know whether my music will last or not. It’s not my business. We’ve really spent too much of our time thinking about this. Probably most of the neuroses of the twentieth century stem from worrying about what’s going to happen to us in the future. I hope that people will understand something as they go by, and I hope that people will respond, and I hope that what I’m doing will become part of that wonderful circuit that Yo-Yo keeps talking about. Then, if it has a certain kind of longevity, fine. I’ve also noticed that longevity for music has nothing to do with current criticism. I’ve looked back into the things that were reviewed by even the very best critics of the past, and much time is spent on people we don’t play at all.

BD: Slonimsky has that wonderful book... [Lexicon of Musical Invective: Critical Assaults on Composers Since Beethoven

’ _s Time_]

WB: Exactly! It