Catherine Malfitano Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . .

[Note: This interview from 1985 was originally published in the Massenet Newsletter. It has been slightly re-edited for this website presentation. Photos and links have been added, as have the two boxes with her biography and Chicago performance history.]

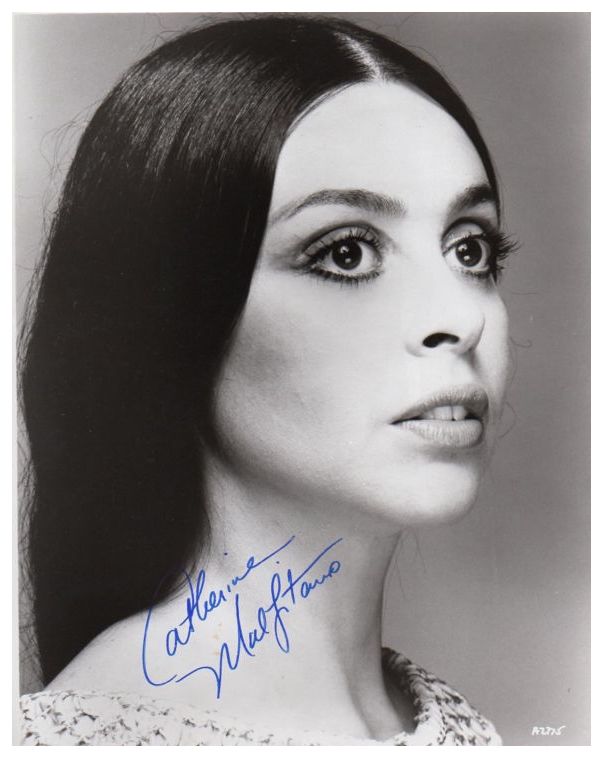

Soprano Catherine Malfitano

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

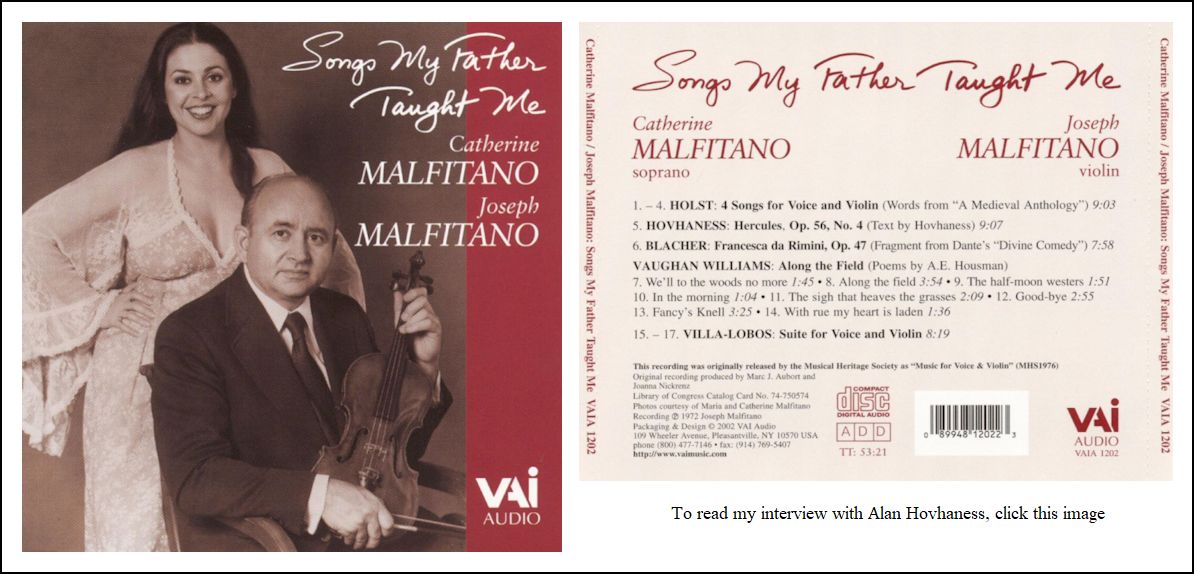

Catherine Malfitano, Singer, Actor, Director, and Teacher, was born in New York City on April 18, 1948, to a dancer/actress mother and violinist father. Renowned as a unique music theater performer, Ms. Malfitano has appeared at all the world’s leading opera houses including the Metropolitan Opera, the Lyric Opera of Chicago, the Vienna State Opera, La Scala, the Bavarian State Opera, the Paris Opera, the Royal Opera Covent Garden, Berlin’s Deutsche Opera and State Opera, the Salzburg Festival, Florence’s Teatro Comunale, the San Francisco Opera, the Netherlands Opera, the Los Angeles Opera, the Houston Grand Opera, the Théâtre du Chatelet in Paris, the Grand Théâtre du Genève, Barcelona’s Liceu, the Hamburg State Opera, and Brussels’ Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie. Her Emmy-award winning portrayal of Tosca, broadcast live from the actual Roman settings of the opera, was seen by more than one billion viewers worldwide.

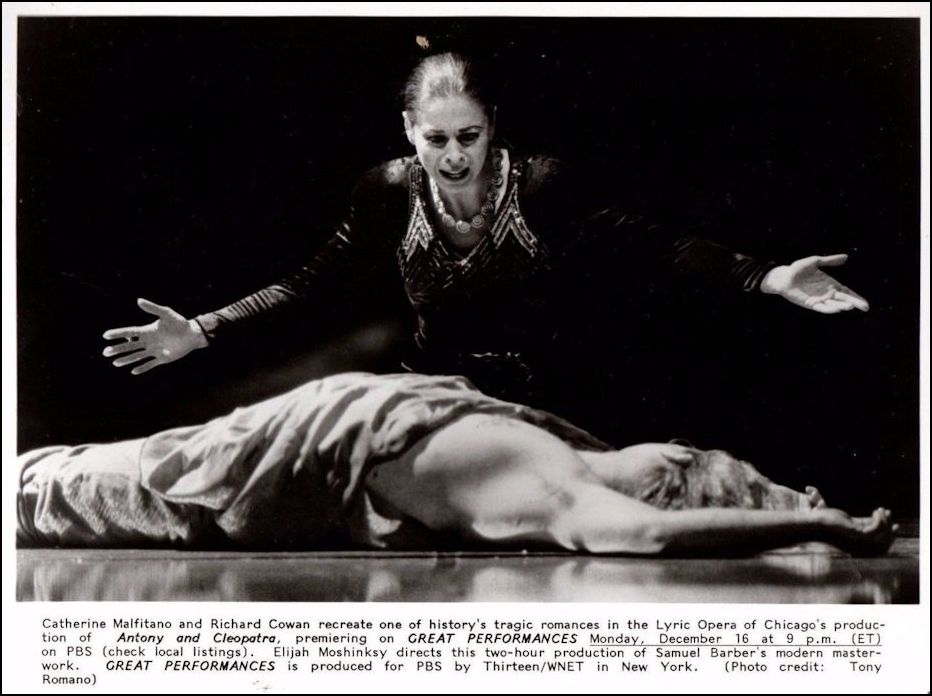

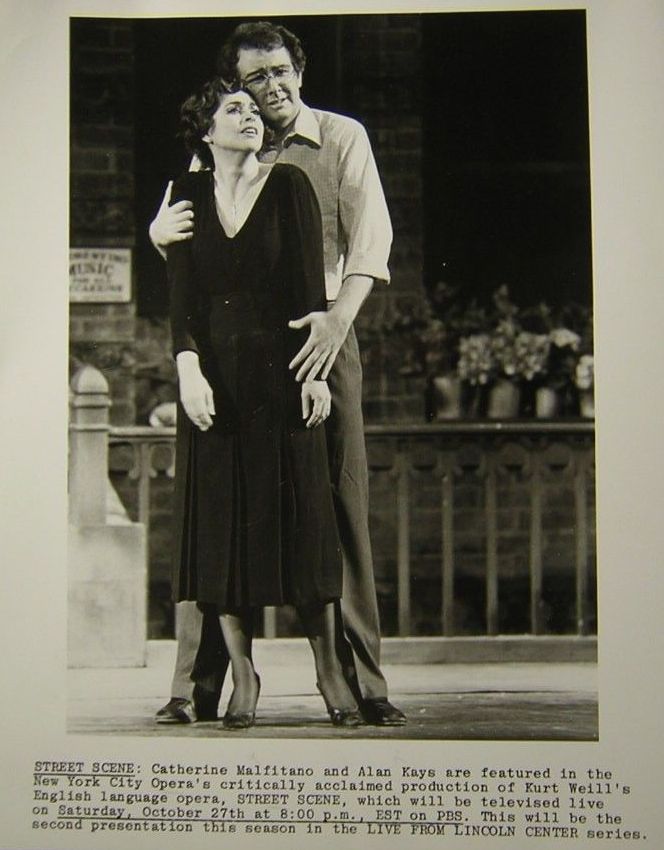

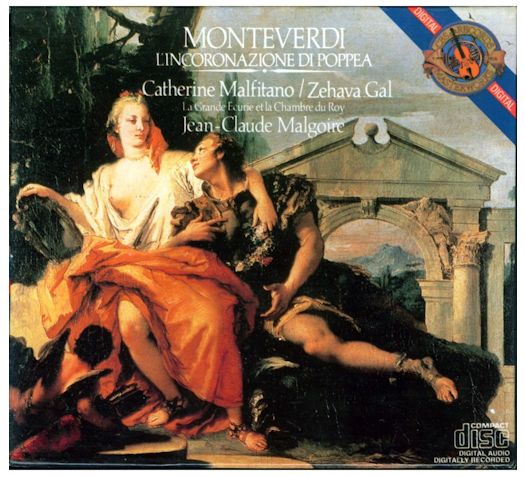

Malfitano’s stage repertoire of more than seventy roles spans the entirety of operatic history. Her interpretations extend from Monteverdi’s Poppea and Erisbe in Cavalli’s L’Ormindo to Annina in Menotti’s Saint of Bleecker Street; from Gluck’s Euridice to Polly Peachum in Weill’s_Three Penny Opera_; from Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor to Humperdinck’s Gretel; from Marzelline and Leonore in Beethoven’s Fidelio to Poulenc’s Thérèse in Les Mamelles de Tirésias; from Konstanze in Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Susanna in Le Nozze di Figaro and both Zerlina and Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni to Cleopatra in Samuel Barber’s_Antony and Cleopatra_; from Fiorilla in Rossini’s Il Turco in Italia_to Emilia Marty in Janáček’s Makropulos Case; from the three heroines in Offenbach’s Les Contes d’Hoffmann to the three heroines in Puccini’s Il Trittico; from Violetta in Verdi’s La Traviata and Lady Macbeth to Rose and Anna Maurrant in Weill’s Street Scene; from the title roles in Massenet’s_Manon and Thais to Puccini’s Tosca, Cio-Cio-San, Mimì, Liù, and Minnie.

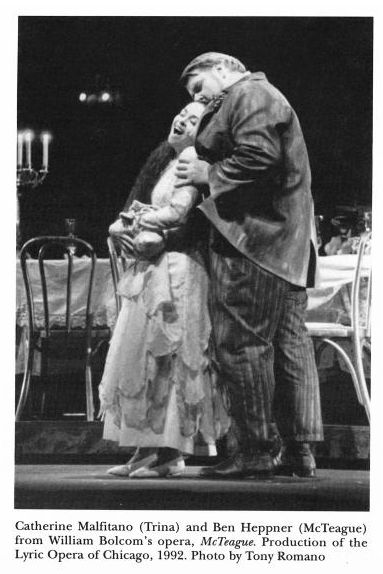

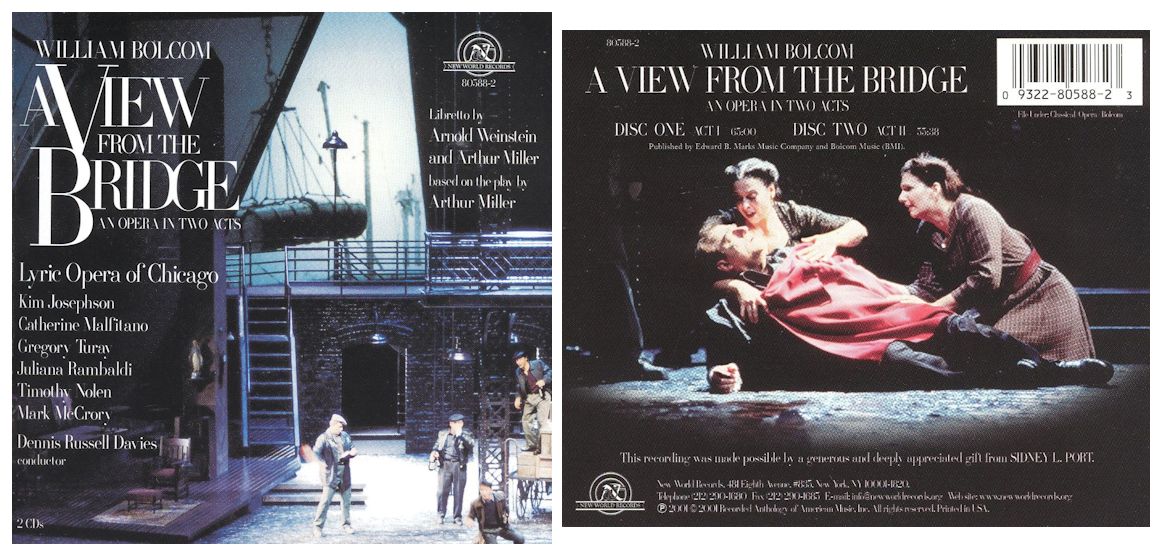

A champion of twentieth century music, she has sung in the world premieres of Carlisle Floyd’s Bilby’s Doll, Conrad Susa’s Transformations, Thomas Pasatieri’s Washington Square and The Seagull and William Bolcom’s A View from the Bridge, McTeague, A Wedding, and_Medusa_. She has also sung Berg’s Lulu and Marie in Wozzeck, Schreker’s Der Ferne Klang, Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, Poulenc’s La Voix Humaine and Weill’s Mahagonny and Seven Deadly Sins.

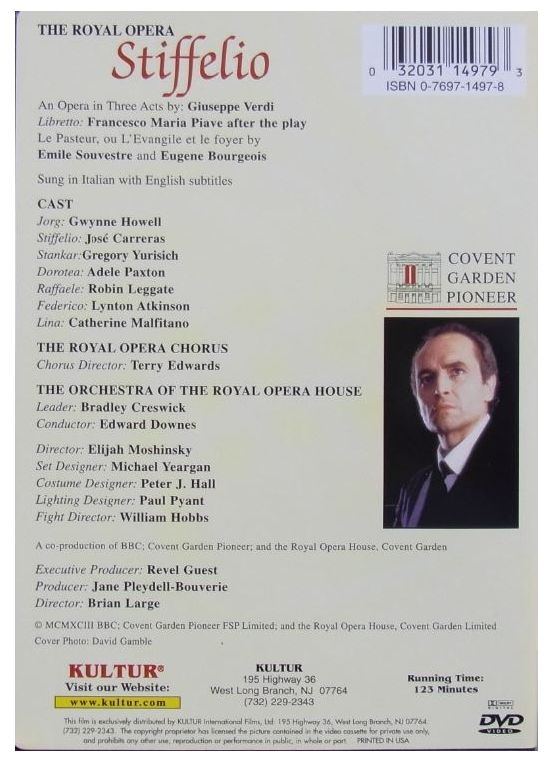

Throughout her career, Ms. Malfitano has worked with the world’s leading conductors including Daniel Barenboim, James Levine, Zubin Mehta, Wolfgang Sawallisch,Christoph von Dohnányi, Sir Colin Davis, Riccardo Muti, Sir Charles Mackerras,Riccardo Chailly,Giuseppe Sinopoli,Valery Gergiev, Christoph Eschenbach,James Conlon,Neeme Järvi,Sir Andrew Davis, Daniele Gatti, Dennis Russell Davies, Carlo Rizzi, Semyon Bychkov, Donald Runnicles, Simone Young, Michel Plasson and Bruno Bartoletti. Her collaborations with directors Robert Altman, Jean-Pierre Ponnelle, Luc Bondy, Nikolaus Lehnhoff, Patrice Chéreau, Elijah Moshinsky, Sir Peter Hall, Peter Zadek, David Pountney, Giuseppe Patroni Griffi, Graham Vick, Götz Friedrich, David and Christopher Alden, John Dexter, Giancarlo del Monaco, Jürgen Flimm, Stein Winge and others have produced many of the most memorable operatic events of our time.

In the summer of 2005 Catherine Malfitano added another facet to her artistic profile with her debut as a stage director. Her critically acclaimed new production of Madama Butterfly was the highlight of the Central City Opera festival season, and marked her return to the theater where she had made her professional singing debut in 1972. The Financial Times praised her production as “thoughtfully conceived, fluently executed, and heavy with ritual,” while Opera News added “Malfitano fashioned a Butterfly rich in memorable imagery…she worked successfully with the central couple to delineate credible romance; their sensitive enactment of the love duet fueled genuine erotic heat.” ColoradoDrama.com lauded her innovation, citing her production as “one of the most significant and powerful in memory. Malfitano’s dramatic and bold staging bodes well for her second career as a director.”

Since 2005 she has also directed new productions of _La Voix Humaine_by Francis Poulenc (in which she also performed the role of Elle) for La Monnaie in Brussels, Gian Carlo Menotti’s The Saint of Bleecker Street, again for Central City Opera, Tosca for Florida Grand Opera, _Rigoletto_for Washington National Opera, Don Giovanni for San Francisco Opera’s Merola Program, and Lucia di Lammermoor for Central City Opera. In 2010 she made her UK directing debut in London, with a new production of Tosca for English National Opera. Other directing engagements include a new production of Lucia for the Lyric Opera of Chicago, a revival of Tosca for English National Opera, and a new double-bill production of Zemlinsky’s Eine florentinische Tragödie and Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi.

Since 1998 Ms. Malfitano has been teaching privately, giving master classes worldwide as well as her own special course entitled “Revealing the ActorSinger Within.” She joined the Voice Faculty at the Manhattan School of Music in the fall of 2008.

-- Biography from IMG Artists website (text only - photos and links added)

-- Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

In December of 1985, soprano Catherine Malfitano was in Chicago for performances as Violetta in Verdi’s La Traviata. Knowing that she had sung some French roles, I arranged to have a conversation with her for use in the Massenet Newsletter. Right at that time, word leaked out that Malfitano would be back in a future season for Berg’s masterpiece, Lulu, so we also chatted about that very difficult role. It wasn’t until well into the discussion that the connection was made between the characters of Lulu and Manon, and I knew that this revelation would be fascinating to readers of this journal.We met at her apartment between performances, and she was most cordial and gracious. She is well-known to audiences in New York, and Chicago was pleased with her portrayals. In the Fall of 1987, Malfitano did indeed return for the anticipated Lulu. The production was a resounding success, and won many converts among subscribers who had dreaded coming to such a work. [Her many appearances with Lyric Opera are fully detailed in the box at the end of this interview.]

In December of 1985, soprano Catherine Malfitano was in Chicago for performances as Violetta in Verdi’s La Traviata. Knowing that she had sung some French roles, I arranged to have a conversation with her for use in the Massenet Newsletter. Right at that time, word leaked out that Malfitano would be back in a future season for Berg’s masterpiece, Lulu, so we also chatted about that very difficult role. It wasn’t until well into the discussion that the connection was made between the characters of Lulu and Manon, and I knew that this revelation would be fascinating to readers of this journal.We met at her apartment between performances, and she was most cordial and gracious. She is well-known to audiences in New York, and Chicago was pleased with her portrayals. In the Fall of 1987, Malfitano did indeed return for the anticipated Lulu. The production was a resounding success, and won many converts among subscribers who had dreaded coming to such a work. [Her many appearances with Lyric Opera are fully detailed in the box at the end of this interview.]

Here is much of that enlightening conversation . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: You’re one of the very few singers who does both Romantic and Twentieth Century works. How do you manage to accommodate both styles, and not tie your voice into knots?

Catherine Malfitano: Primarily because I started off doing it that way. From the very beginning of my career, it was set up like that. My first professional engagement was as Nannetta in Verdi’s Falstaff in Central City, and immediately following that, I did an opera by Thomas Pasatieri called The Black Widow. Those were in 1972, and it set the pattern for the early part of my career. In the next few years, I did three premieres

— Conrad Susa’s Transformations in Minnesota, Washington Square by Pasatieri in Michigan, and Bilby_’_s Doll by Carlisle Floyd for the Houston Grand Opera. Later I did The Saint of Bleecker Street by Menotti at the New York City Opera, and Street Scene by Kurt Weill, but I don’t consider any of those operas unvocal in the way that most people think of modern music. In fact, I did Berg’s Lulu for the first time this year (1985), and it was the most difficult of any I’ve done, and it is the oldest of these works I’ve just mentioned. Lulu is certainly far ahead of the others in terms of vocal writing.

BD: What is it about Lulu that makes it so much more difficult?

CM: All of those contemporary operas are very consonant; they are not dissonant at all. Floyd uses more complex harmonies than Pasatieri or Susa, and certainly more than Menotti or Weill. It’s not a problem, but a challenge to do the Berg because there are several layers. On first hearing, one doesn’t detect immediately where the line or melody is. It takes some analysis and a great deal of listening and exposure. Once you understand it, the music sounds logical and apparent, and you follow the line as it shifts among various instruments in the orchestra, and then to the voice on stage. At first, the voice doesn’t seem to have any relationship to what’s going on in the orchestra, but in fact it’s a highly structured piece.

BD: Is this something on the page for the eye, or does it eventually come across to the ears of the audience?

CM: It’s on the page, but it’s also there for the ear. I cannot stress enough how constant exposure to the music brings that out. It’s not easy in the beginning, but any opera at first can be difficult to listen to. Nowadays, it’s difficult for us to imagine hearing a Strauss opera for the first time, but for the people of that time, it must have been startling to hear his works, or even those Puccini or Verdi.

BD: [Gently protesting] But in the Nineteenth Century, the public was always clamoring for something new. Now we clamor for something old.

CM: That’s the point. I don’t quite understand it, and that comes back to your original question about how and why I do it. I feel a sense of responsibility toward our time. I don’t want to be just an artist who reflects the past. I don’t want to reject it, either. If it’s possible for artists to do both, they should do both. Artists who choose to do only contemporary music may feel it’s so difficult, that their career should be devoted entire to it. Or, it may be that they really can’t sing the other, and they can get away with it in contemporary music. That bothers me because then the public never get to hear that music sung beautifully, and with the technique that is used for the more traditional operas.

BD: Do you enjoy the character of Lulu?

CM: Yes, I do. I’ve always been attracted to the character, even before I was convinced that I would ever like the music. So, I thought that even if I didn’t enjoy the music, at least I’d enjoy doing the part.

BD: Have you done any roles that you really don’t care for?

CM: I have, but once I’ve experienced them I don’t do them again. My reasons for not wanting to do them can be either musical or dramatic. I want to find roles that involve me emotionally and stimulate my intellect. It comes down to being a challenge. Roles which don’t have enough contrasts really don’t interest me. I try to make too much happen, and it’s not fair to the role. Roles which are stimulating are fun. One could take the attitude that it’s an easy role, and I can rest my voice and get paid a nice fee, but that’s not an option for me. Monteverdi’s Poppea or Susanna of Mozart are roles that I enjoy, but still are a bit restful, and I can do them after a series of performances of Lulu.

CM: I have, but once I’ve experienced them I don’t do them again. My reasons for not wanting to do them can be either musical or dramatic. I want to find roles that involve me emotionally and stimulate my intellect. It comes down to being a challenge. Roles which don’t have enough contrasts really don’t interest me. I try to make too much happen, and it’s not fair to the role. Roles which are stimulating are fun. One could take the attitude that it’s an easy role, and I can rest my voice and get paid a nice fee, but that’s not an option for me. Monteverdi’s Poppea or Susanna of Mozart are roles that I enjoy, but still are a bit restful, and I can do them after a series of performances of Lulu.

BD: It seems like most of your roles are the whole weight of the operas

— Lulu, Susanna, Violetta, Manon...

CM: Well, I like that! I’ve done a few roles

— even one at Salzburg — where the part is very beautiful, but so short that the waiting time between arias is too long. I go crazy siting in my dressing room waiting around to go back on stage. I have to be out there on stage. That’s where I live, that’s where I feel the best and happiest. I don’t like roles where I spend most of the time in the dressing room.

BD: Let me ask the Capriccio question. Which is more important, the music or the drama?

CM: They’re both important. I don’t know which should come first.

BD: Does the balance shift from one composer to another?

CM: Yes, absolutely. It’s always shifting with different composers. Usually they want the audience to understand the words, but often they abandon that hope in favor of vocal effects. Puccini, for example, will write pages of conversation, and others just sheer vocal sound.

BD: Talking about the importance of text, do you do any of your roles in translation?

CM: I did earlier on when I was singing in regional opera houses. I think it was good.

BD: Do you find any more closeness with the audience that way?

CM: Yes, that’s the major reason to do it. At this point in my career, I don’t think I’d ever want to do it again. I guess the supertitles are okay, but the ideal is to get away from any of these crutches. [Remember, this interview took place in 1985, when supertitles were just coming into general use.]

BD: What do you expect from the audience?

CM: That’s a good question. What I expect from a performer is easier to answer, but I do expect involvement by the audience. I like to feel that the audience can be sucked into a drama, into the music, into the atmosphere of the piece that I’m involved in. That’s what I try to accomplish as a performer. I like to really move, even disturb, as well as entertain the audience. So, the primary expectation I have is an openness of spirit, and willingness to be pulled along and into.

BD: Then where is the balance between art and entertainment?

CM: Everything on the stage should be entertaining. That is not to say that entertainment can’t be disturbing. People have an idea that entertainment means having fun, with light pieces that don’t have dark or deeper resonances. But it depends on what people want. It’s a matter of interpretation what is entertainment.

BD: Besides being a singer, do you feel you are also an athlete?

CM: I like to keep up a very physical, active life. You see my exercise bike over there in the corner, which I use every day. I have to be active. There are too many built-in energies inside of me, and if they’re not being used directly on the stage, where they’re most happy, I have to find a way to channel them. Exercise is a good way.

BD: Do you like being a wandering minstrel?

BD: Do you like being a wandering minstrel?

CM: I think I do. There are times when I miss being home, and I’ve learned to accept the idea that wherever I am has a sense of home. So, I make home be wherever I am, but there is no replacement for my home in New York City, which is my birthplace. It’s always important to be able to return there.

BD: So, is a contract at the Met, or the New York City Opera, special because it’s home?

CM: That certainly had a great deal to do with it. Every time I return home to sing, there is a special feeling there.

BD: Are the audiences in America different from the audiences in Europe? [_Vis-à-vis the DVD shown at left, see my interviews with Gwynne Howell, and Robin Leggate._]

CM: A lot of people ask that question, and it’s difficult to answer. I’ve witnessed enthusiastic audiences in both places, depending on the circumstances of the performance. There are also negative reactions all over. When I’m not singing, I’m attending opera all the time, so I get to watch the audience a great deal. But when an audience is enthusiastic, they are never more so than in Vienna and Salzburg.

BD: Is it good to be so demonstrative?

CM: Not if it happens every single night with any old artist. There should be a certain sense of distinguishing between one performance and another. In certain European capitals, such as Vienna, the audience can be extremely hard on an artist. They can carry on and give you thirty curtain calls, but they can also be brutal and boo and demonstrate very much against an artist.

BD: Should the audience boo?

CM: I don’t think so, personally. One of the strongest reactions an audience can give is not to applaud at all. I’ve heard about that happening. A singer came out in front of the curtain and the audience stopped applauding. That must have been more devastating than being booed. It’s a destructive thing to boo. Even if an artist is bad, one has to distinguish whether it’s just an off-night of a good artist, or they’re not singing the right role, or are simply past their good singing days. There are so many variables. It’s not easy to get up there on the stage no matter who the artist is, and the audience sometimes forgets that. But booing can be a way for the audience to release their pent-up frustrations.

BD: Are there singers who make it who shouldn’t? And vice-versa, are there some who don’t make it that should?

CM: I think the answer to both question is yes, but the more fundamental ideas are the qualities that make a career. One would think that success depends on talent, but that’s only a part of it. Lots of artists say that. Anybody who is successful in their work can relate to this because everyone has to rely on a lot of things to become successful in whatever they do. Whatever talent or skill you have is a starting point. Then comes the incredible commitment to that skill, to hone it and develop it. It’s a kind of discipline that not everyone has. There are some who can get away with their natural gifts and go very far and become successful, but at some point they will stop, or they won’t go as far as they could have. No natural gift will go by itself without some discipline or some elbow-grease. There are all kinds of other things that can help people make something of their careers. Luck is a part, but very small part of it. You have to have an awful lot of encouragement from people around you. It’s very important to have a belief in yourself, a sense of confidence, and that can only be reinforced by the outside. Surely there are a few individuals who believe in themselves no matter what anybody else says about them, and they can give themselves the kind of support they need to continue, but most people need outside encouragement. Developing a tough skin to resist the myriad kinds of hardships one encounters all along is also necessary.

BD: Do you ever feel you’re a slave to the voice or to your career?

CM: I suppose from time to time, but this is what I want to do, so ultimately I could not say that I was a slave to it. There are moments I’d like to not have to practice, or maybe take half a year to not sing, and just do other things in my life, but if you don’t sing for six months, you probably need a year to get back in shape again, and that’s not worth it. So, in that sense you do become a slave to your art, but there’s too much gratification and pleasure to feel enslaved for very long.

BD: Does it give you a secure feeling to be booked several years ahead?

CM: Yes, and no. Yes, it’s secure, but it doesn’t leave enough room for spontaneity. That’s especially true if your seasons are booked solidly. I’m starting to find a balance. I try to book major portions of the year but leave other areas open. Then if something comes along that I want, I’ll take it. My first Lulu came about that way in Munich. The time was open and I accepted, and I was thrilled to have had that opportunity without needing to rearrange my whole schedule or try to get out of other commitments. Knowing way in advance is nice, but it can lose that spontaneous excitement when you live with that idea for so long. It’s good to have a sense of security, and it’s good to have those surprises, so to manage a schedule that has both is ideal.

BD: When you’re up on the stage, are you portraying the character or do you become that character?

CM: I’m portraying the character. When I was young and learning a great many roles, and learning my craft of what it was to be an actress, I became the characters. It was great to do that because it stretched me along with my own sense of myself. It made me look deep down inside of myself to pull out things that I didn’t know where there. Now I rely much more on technique and a sense of being able to know how to portray that character without having to be her. So, the sense from the audience is that I am the character when in actuality it’s a technique.

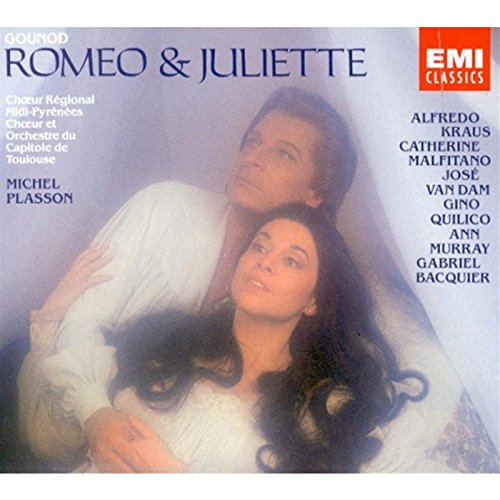

BD: Let’s come around to the French repertoire. You’ve sung a number of roles, so we can start with Juliette. [_Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Alfredo Kraus, José van Dam, Ann Murray, and Janine Reiss (vocal coach for the recording)._]

BD: Let’s come around to the French repertoire. You’ve sung a number of roles, so we can start with Juliette. [_Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Alfredo Kraus, José van Dam, Ann Murray, and Janine Reiss (vocal coach for the recording)._]

CM: She gets to live a very fast life in terms of years and maturity. We see her in the beginning as a very young girl. It’s her birthday, and her first exposure to society. She has all the hope and aspiration of finding a young man. Love is fresh for her. She also has a great deal of character. She’s not a wimpy kid. She’s full of pepper, and knows that her parents have picked out this character, named Paris, for her, and she doesn’t think very much of him at all. So, there’s already a great sense of independence and strength. Everybody knows what happens. She and Romeo fall in love, and though their relationship doesn’t last very long, you see the tremendous growth from the child to the woman in a very short span of time. That, for me, is the great challenge

— to portray that incredible growth that most of us have a lifetime to express. The music reflects that gaiety, that youth, that sparkling vivacity, and that peppery quality she has in the beginning very beautifully. If you compare that first aria to the one just before she takes the potion, which will put her to sleep, she has a big decision to make. Is it, perhaps, really poison? Might she die? Will Romeo really come? She’s got to take a chance and make an adult decision. The music reflects that great expanse of knowledge she suddenly has to use, and the great passion she feels for Romeo, and the great daring she has. I think Gounod expresses all the qualities of Juliette very, very well. In some way, I think she’s stronger in the opera than in the play.

BD: How does Gounod add a French taste to it?

CM: It’s most telling in the balcony scene. In Shakespeare, it doesn’t go on as long as it does in the opera. There are many lines for Juliette in the opera. It’s perhaps the most difficult thing to portray musically because it’s not the more obvious type of structure

— aria, duo, etc. — except at the end when they are parting with such sweet sorrow. That’s a set-piece, but earlier it is quasi-recitative, which is very French. Wistful internal musings are things the French do so well. There are very delicate kinds of shadings on the words.

BD: You’ve also done Marguerite?

CM: Yes, I’ve done it twice now, and I was just doing it in Florence before coming to Chicago. There again, I got to do the second aria. Gounod’s second arias were so often cut in Paris, but we did everything including the Walpurgis Nacht, which is a very long ballet. In the second aria of Marguerite, you have again this child-to-woman progression in a much quicker space of time. She has a brief scene, but her first real music is the Jewel Aria in the garden. She’s quite a young woman, also rather naïve and sheltered. But where Juliette has a knack for picking the right person

— even though his circumstances were wrong —Marguerite chooses the wrong man to love. In a certain sense, she seems to have less wisdom than Juliette. I prefer Juliette as a character. She’s a much more intelligent and clever woman.

BD: So you think Romeo and Juliette would have been happy if it had worked out correctly?

CM: Yes, definitely, but not Faust and Marguerite. Faust is a very strange man who’s dealing with age-old problems. We all have to do that, but he’s a pretty horrible character. What happens to Marguerite is a pretty horrible situation if one takes it on a realistic level. One can also take it on symbolic levels, so that we’re not dealing with specific characters but rather with prototypes. In her second aria, Marguerite is pregnant, and the music reminds you a little of Schubert’s (song) Gretchen am Spinnrade because it has a kind of spinning-wheel motif in the orchestra. She’s lamenting the fact that she’s been abandoned by her lover, and wondering when he’ll come back. It adds a poignancy to her character, and a contrast to the wonderful_Jewel waltz_. Gounod always has a waltz for his heroines! But if you cut the second, dramatic aria, you have a character who is rather shallow, and you don’t get to see how the composer intended to have his women grow. I like the whole work, but the church scene is my favorite. It’s very dramatic when she finds Mefistofele inhabiting the church, and I think it’s the most exciting music of the whole opera. Everybody loves the final trio, and it’s effective, but I don’t think it’s a great piece of music.

BD: Is there any satisfactory way of staging that final scene?

CM: I don’t know. [Laughs] I have not seen it done really well. I’ve seen a lot of ‘kitchy’ endings, and I don’t remember how it was done in Paris. The piece is very surreal, and if anything ever needed to be done in a surreal manner, Faust is it. Romeo and Juliette is a romantic love story and could be done in epic style, but not surreal. Faust is not about real people, but about types of people, and the ending is not realistic. It needs a very imaginative director who may be a little far-out, but who could find solutions.

BD: The next opera to speak about is your big role, Manon.

CM: It’s my favorite French role. [_Malfitano’s husband, who has been listening to the conversation, shakes his head and says it’s Antonia._] Well, that’s another favorite, but a very personal kind of role that gets total identification. She’s a singer who has to sing, with a mother and father close to the theater. My father is a violin player, and my mother is a dancer, so the whole family-theater environment is something so close to my existence that Antonia is a kind of autobiography. So, going back to your earlier question about whether you portray or become the character, with Antonia I am the role!

BD: You’ve done all three roles in Hoffmann. Is it more satisfying to sing all three rather than just one?

CM: Absolutely! When I do Antonia in the midst of three, it makes her even stronger. Again, it’s being able to play off the contrasts. When I get to Antonia, the depth of fanaticism, despair, and feverishness of that character is a great contrast to Olympia, who is this inanimate dead thing, a strange kind of devil’s tool. She has no sexuality

— or perhaps a dead, strange, demonic sexuality — but she has to have the capacity to be destructive. Antonia is the one in the piece who is full-blooded, and is the most sympathetic character for the audience. But getting back to Manon, she’s a real treat to do. She’s the French Lulu! Before I did Lulu, I knew that she would be a wonderful role to do because I had already tasted Manon from the very beginning of my career. Two years into my career I started doing Manon. Manon, like Lulu, epitomizes great sexuality and sensuality without being aware of it. Manon is more aware of it than Lulu, and has that incredible aria in the Cours-la-Reine. However, as you see her in the beginning, she’s totally innocent.

BD: Is she a virgin when she first comes on stage?

CM: Yes, I think she is, but it’s debatable. I can see it being valid both ways. She’s being sent off to the convent, so if she is still a virgin, it’s only a matter of minutes before she’s not any more. [Laughter all around] Her parents sense that, and sending her away was the thing to do in those times

— especially when the daughter was so lovely and appealing and sensual. But there is a real innocence about her, a naïveté, a sense of her not knowing what her real attraction is and not being aware of it. But everyone is attracted to her despite themselves. Manon eventually does become aware of her power, and she uses it. Lulu does too. All these French heroines live very fast lives!

BD: Like the old quote, ‘Live fast, die young, have a good-looking corpse!’

CM: That right, exactly! But in every scene, Manon is a different character. You asked if I enjoy doing the three ladies in Hoffmann. I see that as three aspects of the same character, or three facets of the same jewel. I enjoy those characters who are multi-sided, like Manon, or Lulu, or Violetta. They let you show the different characteristics of the one person. Roles that have very few facets don’t challenge me very much, and I don’t think people are like that. Interesting people have many facets, and are different from day to day. I love characters who are like that because I’m like that, and I’m lucky that as a performer I get to explore. I’m allowed. It’s almost sanctioned that I be all these different people because I use it in my work. It’s a wonderful kind of experience to be able to do.

Catherine Malfitano at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1975 - Marriage of Figaro (Susanna) with Dean, M. Price, Stewart, Ewing, Voketaitis, Begg, Andreolli;

Pritchard, Ponnelle

1985-86 - Traviata (Violetta) with Araiza, Elvira, Stoltz, Negrini; Bartoletti, Alden, Pizzi, Schuler

1987-88 - Lulu (Lulu) with Trussel, Braun, Foldi, Kaasch, Lear (Geshwitz); D.R. Davies, Ljubimov;

Borosvkij, Schuler

1991-92 - Antony and Cleopatra [Barber] (Cleopatra) with Cowan, Trussel, Halfvarson,White;

R. Buckley, Moshinsky, Yeargan, Tallchief, Schuler

Madama Butterfly (Butterfly) with Leech, Stilwell, Romanò, Markley; Gatti, Prince, Dunham

Turandot (Liù) with Savova, Jóhannsson, Doss; Bartoletti, Farlow, Hockney, Schuler

1992-93 - [World Premiere] McTeague [Bolcom] (Trina Sieppe) with Heppner, Nolan, Golden;

D.R. Davies, Altman, Kuper, Schuler

1995-96 - Makropulos Affair [Janáček] (Emilia Marty) with Begley, Fox, Ulfung;

Bartoletti, Alden, Edwards, Schuler

1996-97 - Trittico (Giorgetta, Angelica, Lauretta) with Lafont, Jóhannsson, Panerai, Aronica, Castle;

Bartoletti, Winge, Hoheisel

Salome (Salome) with Terfel, Riegel, Silja (Herodias), Keys; Pappano, Bondy, Wonder

1997-98 - Madama Butterfly (Butterfly) with Leech/Denniston, Stone, White, Cangelosi;

Fisch, Prince/Liotta, Dunham

1998-99 - Mahagonny [Weill] (Jenny) with Begley, Nolen, Palmer, Devlin, Aceto;

Cambreling, Alden, Steinberg

1999-00 - [World Premiere] View from the Bridge [Bolcom] (Beatrice) with Josephson, Turay, Rambaldi, Nolen;

D.R. Davies, Galati, Loquasto

Macbeth (Lady Macbeth) with Grundheber, Aceto, Aronica; Fisch, Alden, Edwards

2000-01 - Flying Dutchman (Senta) with Morris, Hawlata, Begley, Gorton, Wottrich; Davis, Lehnhoff, Bauer, Tallchief, Schuler

2001-02 - Street Scene [Weill] (Anna Mourrant) with Turay, Gardner, Nolen; R. Buckley, Pountney, Pyant

Parsifal (Kundry) with Winbergh, Salminen, Delavan, Silins, Kristinsson; Davis, Lehnhoff, Bauer, Tallchief, Schuler

2003-04 - Regina [Blitzstein] (Regina) with Shelton, Nolen, Woods, Blackwell, Travis, Langan; Mauceri, Newell, Culbert

2004-05 - [World Premiere] A Wedding [Bolcom] (Victoria) with Hadley, Gardner, Doss, Lawrence, Flanigan, Nolen, Harries; D.R. Davies, Altman, Wagner, Schuler

2011-12 - Lucia (Director) with Phillips, Filianoti/Barbera, Mulligan/Kelsey, Van Horn; Zanetti, Chin, Schuler

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on December 7, 1985. Much of it was transcribed and published in the Massenet Newsletter in January, 1991. Portions were broadcast (along with her recordings) on WNIB in 1995 and 1998. The transcription was slightly re-edited in 2018, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website,click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.