David Del Tredici Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . (original) (raw)

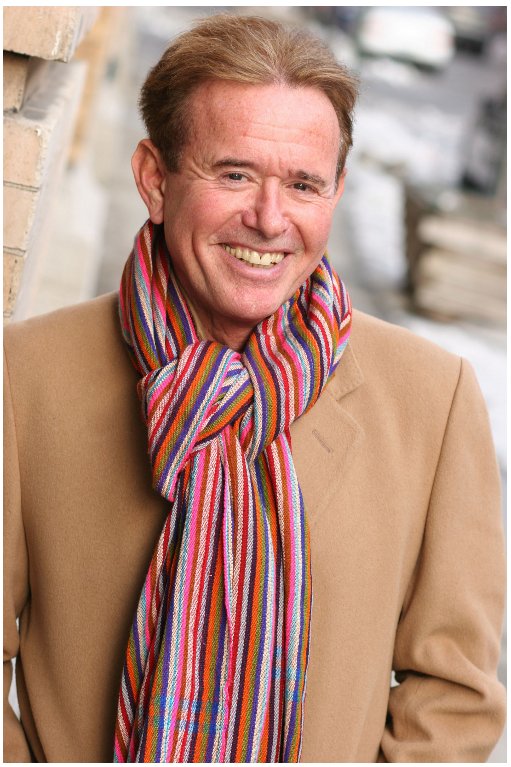

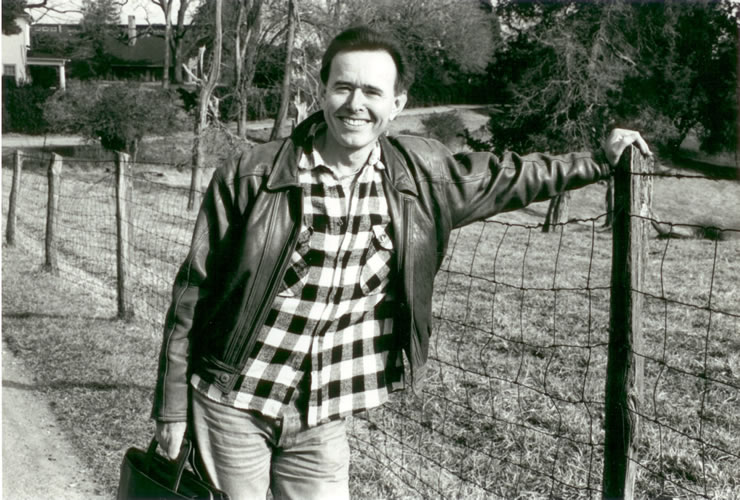

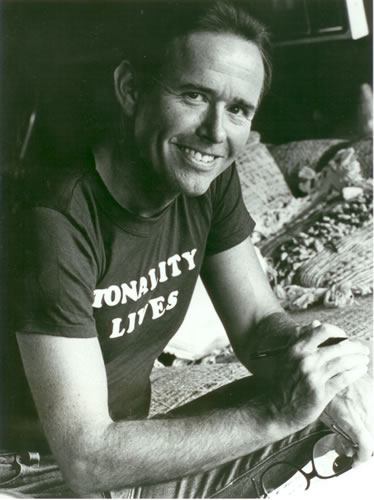

Composer / Pianist David Del Tredici

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Sometimes things which are perfectly correct look odd or simply cannot be used because of circumstances beyond the control of any and everyone. Some of these blockages are good, some are bad, and some are simply amusing when given any thought.

As readers of my interviews will know, after the first introduction using the full names, I indicate who is speaking by way of their initials. Bruce Duffie always becomes "BD," and Joe Musician would be "JM." In the case of today's guest, David Del Tredici should be listed as "DDT," which, unfortunately, is known these days as a pesticide that has been banned! I toyed with using "DdelT," but that simply looks odd and cumbersome. I even thought of using "D-13" (since "tredici" is that special number in Italian), but decided against making the reference. So this time, I have listed our last names in lieu of the usual initials.

No matter how things are laid out on the page, this turned out to be a very enlightening interview. My guest talked openly and frankly about the composing process, and in turn revealed a great deal about music in general, as well as himself and his work habits. Quite a number of my guests have given insights, but looking back over a quarter-century of material, this one seems to shine a light over more area and in more detail than most.

A brief biography of the composer, taken from his official website, is reproduced following the interview. Names on this page which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website.

One should note before starting, however, that aside from performances with major orchestras and chamber groups, and recordings of many of his pieces, Del Tredici is the winner of the Pulitzer Prize.

At the beginning of 1990, Del Tredici was back in Chicago to participate in a concert of chamber music. We met in a dressing room downstairs at Orchestra Hall in Chicago during the afternoon rehearsal, and following the concert, I moderated a discussion among the four composers (!) who were there [also Lukas Foss, Peter Schickele, and Paul Schoenfield]. It was a long, but wonderfully lovely day for all concerned.

Bruce Duffie: I'd like to begin by asking about the joys and sorrows of writing for the human voice.

David Del Tredici: Oh, what a nicely phrased question. My relation to the voice has been as idiosyncratic as my composing. That is to say, the first real piece I wrote for voice was called I Hear an Army [(1964), for soprano and string quartet], and it was extremely difficult. I'm not a singer and I really didn't know singers, but I wrote a terrifically hard part. By coincidence it was for the Tanglewood Music Festival, and the singer they had hired was a young girl named Phyllis Bryn-Julson. She'd never sung before, so they put my piece together with her accidentally. She was terrific! She did it so easily that I said, "Well, I'm gonna write her another piece. This is easy vocal writing." I wroteNight Conjure-Verse

David Del Tredici: Oh, what a nicely phrased question. My relation to the voice has been as idiosyncratic as my composing. That is to say, the first real piece I wrote for voice was called I Hear an Army [(1964), for soprano and string quartet], and it was extremely difficult. I'm not a singer and I really didn't know singers, but I wrote a terrifically hard part. By coincidence it was for the Tanglewood Music Festival, and the singer they had hired was a young girl named Phyllis Bryn-Julson. She'd never sung before, so they put my piece together with her accidentally. She was terrific! She did it so easily that I said, "Well, I'm gonna write her another piece. This is easy vocal writing." I wroteNight Conjure-Verse

[(1965), for soprano, mezzo-soprano (or counter-tenor), and chamber ensemble] which was a little harder. Then the next year I wrote something called Syzygy [(1966), for soprano, horn, and orchestra] which is just unbelievably difficult. But Phyllis did them so easily that I really thought that was what singers did. [Both chuckle] After they were all done and I had a little more world experience, I realized I'd created three white elephants and wondered if anyone else in the world could even sing them. So really in a way, Phyllis shaped my vocal style because of that burst of being able to write high, low, and jumping around like an instrument. I've always somehow thought of the voice in terms of that kind of variety and extreme extension.

Duffie: Now do you find that other singers are up to those challenges?

Del Tredici: Oh, yeah. There are always some singers who can do it; in fact there are more and more.

Duffie: Can they do it well?

Del Tredici: Well, you know, it's like anything else. [Laughter] There are some, but not too many. What I always find interesting is that first summer at Tanglewood, when I hadn't met Phyllis, I'd met a more conventional singer who took my part and said, "This is impossible." She tried to sing it and made it sound horrible. So I wonder, would I, in fact, have gotten terribly conservative with my vocal writing and never developed the way I would have? "What if" is really interesting to me, and I think it points out the fact that a performer can enormously shape a composer's direction.

Duffie: Have there been other performers now who have also shaped different directions for different instruments, or even different ways of singing?

Del Tredici: No, not nearly to the extent that I would say Phyllis had because once we hear somebody do it and know that it's possible, we composers just do it. It's like a computer button

— I'll just push that high A again! [Both chuckle] When you compose, you are so involved with creating music, you don't think about — at least I don't think about — little problems like are there too many high A's, or does it lie too high. The hell with it! I'm not interested. When I came to writingFinal Alice [(1974-75), for soprano (amplified), folk group, and large orchestra] for the Chicago Symphony, I thought, "Well, high A is a normal note." What I hadn't realized is that 200 high A's in a row is an increasing problem. I mean, it's only one human being, but luckily, again, I had Barbara Hendricks, who did high A's easily.

Duffie: Are you, then, guilty of treating the voice like an instrument? You can just push the buttons on a keyboard instrument all the time and it's always right there.

Del Tredici: To a certain extent, although all the music I love is high-kind of soprano writing. I love Strauss, I love all of that kind of vocal writing, so it's just a question of degree. I push it and I ignore the human factor. I want this vocal line, and that's that.

Duffie: Do you feel that it's the responsibility of a composer to utilize every possibility of a voice or an instrument that you're writing for?

Del Tredici: No. I think the responsibility of a composer is to find what aspect of a voice or an instrument is them, that I as a composer can turn into me. For some reason, that kind of very agile high-lying vocal writing is something I can put my personality into. I've never written for male voice; I have no relationship to the male voice. I've written for chorus, but that somehow was different. I shouldn't admit these sins, but I don't really consider seriously how the words fall, even, in my vocal writing.

Duffie: Then what do you consider?

Del Tredici: The melody. The melody has to be right. I'm sure many more composers do this than admit it: I will write a piece, and I won't know what's sung and what isn't sung. It's all a line with other subsidiary lines and harmonies, and depending on how the poem goes, how I will divide it with the music. For example, Acrostic Song fromFinal Alice, which is certainly vocal, I began composing just as music; I didn't know what it was. I got halfway through it and I thought, "Oh my God, this is a song! I've got to find a text." So I went to my Alice in Wonderland, and luckily the "Acrostic Song" simply fit it. I shaped the end to really go with it, but that's another thing you can do with the kind of texts I deal with

— that is to say strophic song, where if one line fits and the music is very regular, the other lines will more or less fit. If you're setting something very modern, like e. e. cummings or Joyce, each line is idiosyncratic, and it wouldn't work. So for me to say the things I'm saying, it makes sense in the context of the kind of music I write.

Duffie: You don't feel that you're a reincarnation of Lewis Carroll that's still working on the same piece?

Del Tredici: Oh, I am the reincarnation too, but we won't talk about that. [Both laugh]

Duffie: When you're writing a piece of music — either for voices or instruments — are you always in control of that pencil, or are there times when that pencil is really guiding your hand?

Del Tredici: Again, I love the way you phrase that question. I fight for the times; I try to create an atmosphere where the pencil is guiding me. Those are the highs you like, when it's involuntary and comes out of you, and you sit and watch. I always loved the description Stravinsky gave of how he wrote Le Sacre. He said, "I was the vessel through which Le Sacrepoured," and that's a very good description of the ideal. When it's happening to you, you sit back and watch it. At the same time you're not passive; you're just very much alive and you're very alert to every little thing that's going on in your mind. The problem is getting it down fast enough. It's somehow going through your brain or your system, or your fingers if you're at a keyboard, and you think, "How will I remember this?" I always know when I'm hot composing, and whatever I write when I'm in that state will be good. You just grab it when those times are there, because you know you can't predict when it will happen.

Duffie: Are there enough of those times?

Del Tredici: [Chuckles] Knock on wood! [Raps on table with knuckles three times]

Duffie: When you're faced with the chore of composing

— and I use the term "chore" advisedly — do you know how long it will take you to write it, and then, also, do you know how long it will take to perform the piece once it's out on the page?

Del Tredici: Actually I'm a very poor estimator of the length of a piece because I tend to think of my pieces as the succession of ideas contained. If one movement is one idea, I think it's short. It's one! And also, because I'm a pianist, I play it on the piano much more quickly than an orchestra would play it because of the lack of sustaining power. I think I played Final Alice at 40 minutes, and in fact it came out to 55 or 60. So I'm not a good judge. Composers, I think, are notorious for not estimating correctly.

Del Tredici: Actually I'm a very poor estimator of the length of a piece because I tend to think of my pieces as the succession of ideas contained. If one movement is one idea, I think it's short. It's one! And also, because I'm a pianist, I play it on the piano much more quickly than an orchestra would play it because of the lack of sustaining power. I think I played Final Alice at 40 minutes, and in fact it came out to 55 or 60. So I'm not a good judge. Composers, I think, are notorious for not estimating correctly.

Duffie: Do you know how long it will take you to finish writing a work once it is underway on your desk?

Del Tredici: Oh, no. That's completely in the lap of the gods. I find that I compose more quickly than I orchestrate and finish. Orchestration and writing the whole thing out takes longer than the actual time from blank page to essential lines and harmonies, which is really the essence of the piece.

Duffie: When you've got the idea that you're going to write a certain piece, does it come to you as a piece, or does it move along linearly?

Del Tredici: [Pondering a bit] Because I write such odd pieces... Something like Final Alice is a kind of mix of many texts. In Memory of a Summer Day[(1980), for soprano (amplified) and orchestra, from Child Alice, Part I (1977-81)] is also an hour long. No, I never set out to write the pieces that have come out. I began Final Aliceas a five-minute encore. [Sings] "Dah-deee, dah-dahh, da-da..." It's a short poem, so I thought I would set that, but somehow in my setting it didn't have a closure. So I thought maybe I'll do a variation on it. Well that led to a set of many variations, and then that led to something else, and on and on. In fact, all along the way I fought it. I thought, "This is enough! I've got to bound this piece and make it reasonable. Okay, instead of five minutes, let it be ten." I've done this in all of my long pieces. Finally, at a certain point I have to surrender, and realize that in fact there's this sprawling something that I'm creating. [Both laugh]

Duffie: It's growing like Topsy!

Del Tredici: Yeah! And I have no idea why. Often when I'm composing I keep a notebook. I just jot down any ideas

— the way you would do a journal, without any connection or association or judgment. Then after a few months I begin to see a pattern in these jottings. Different musical ideas tend to go together and then I begin to have a suggestion of form. That's how a form of my pieces evolves. I like not knowing; I don't want to know. If I have a preconceived idea about the piece, I know it'll never turn out that way. It never has.

Duffie: So it's an exploration for you, really.

Del Tredici: Absolutely! That's the fun.

Duffie: Is it, then, an exploration for the audience?

Del Tredici: Oh, it always is. What can they know?

Duffie: Perhaps after they've heard it several times, does it then lose something knowing how it's going to work out?

Del Tredici: Always. That's life! [Both laugh] But then you have the reward of being able to hear details and things you would've missed in the first rush of a piece. There are all kinds of compensations. It's interesting for me because I like very much to write pieces that are very long. I often have in my mind the image of a thriller. If it's a good thriller, you can read two pages and know you won't put it down. It always turns out that that's true, and that's my ideal image for writing one of my long pieces

— that after a minute, I've caught the audience and it all seems inevitable. They can't let it go 'til it's all over. I love that idea, the sense that it just had to be that way, and it's irresistible. The creation of inevitability is what a composer tries to do. You want the illusion that it dropped from heaven and could be no other way. But it's an illusion.

Duffie: So is the ending of the piece really inevitable and you know exactly where it's going to stop?

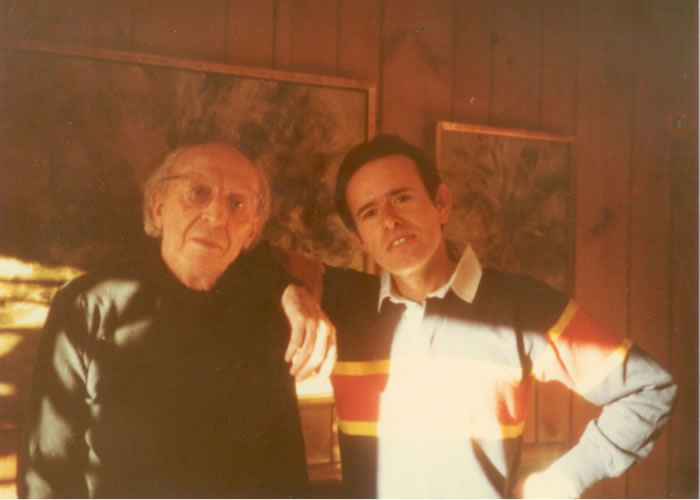

Del Tredici: Yeah. I had a teacher, Roger Sessions, who said to me, "There are certain places in a piece you can't work on. One is the climax and one is the ending. They have to just come to you."

Duffie: Once you get to the end of the piece and put the double bar down, how much tinkering do you do? Do you go back and fiddle with the score and make adjustments?

Del Tredici: When I first think I've finished a piece, then I have to play it all the way through again, and that's very hard because you lose your freshness. So what I often will do is get up in the morning and play through it once from beginning to end, and that's it. Then I just associate with that feeling. Where did I think it was too long? Where is it short? Where did it sag? Then I just work on that and do my corrections. But I only do it once a day because if I play it again, I'll lose those feelings and I'll be used to the way it is

— uncorrected. The next day I'll try it again in this new corrected version, but then something else will be wrong or the corrections won't be right. So I'll make another adjustment, and I'll do that for a long time, not that it's perfect, but until I can't think of a better way to do it. There are always places that just are never right from my point of view. I just sort of abandon it. Like what Mallarmé said, "I never finish poems; I abandon them." It's true! I know there are better solutions somewhere, but I can't think of them.

Duffie: Do you ever come back a couple of years later, or even after the score is published, and make adjustments?

Del Tredici: Sometimes, if it's a horrible thing and something better does come to me later. But when it comes is after I hear it for the first time because actually all this composing and tinkering is not the first degree of reality. You still haven't heard it

— if it's not for piano, which I can realize exactly. But when I hear that rush of orchestra, when I finally hear it all, that sometimes jogs my imagination especially in terms of orchestral color and orchestration. That is something I tinker with enormously after I hear it. And no matter how much experience I've had — and I've had a lot — with writing for orchestra, each piece is the first time. It's all new for that piece. I always redo the orchestration once or twice to some degree after I hear it.

Duffie: You say you always work in large forms and write big pieces. Do you have any small pieces at all? Even Acrostic Song that is for flute and piano is sort of out of Alice.

Del Tredici: Right.

Duffie: You've taken a little piece of it, but it's not really a small piece.

Del Tredici: I think I'm in a little bit of the Wagnerian idea where Siegfried Idyll is a little something out of The Ring. I'm very much sort of that way, and I don't know why! I began as a normal composer. I wrote little piano pieces and a few little songs...

Duffie: [With a gentle nudge] Is there such a thing as a normal composer?

Del Tredici: [Chuckles] Well, I think it's more "normal" to feel natural in the forms which have had a certain tradition

— the concerto, the symphony, etc. I would like to be that way; it's so much more practical as well. Orchestras are waiting, quartets are waiting, but nobody is waiting for an hourlong piece for amplified soprano and orchestra, nobody!

Duffie: And yet yours get done with regularity!

Del Tredici: [With amused pleasure] Ironically it's true. It's interesting, when somebody really wants to do something special, they do a piece of mine because there aren't that many white elephants roaming the musical plains!

Del Tredici: [With amused pleasure] Ironically it's true. It's interesting, when somebody really wants to do something special, they do a piece of mine because there aren't that many white elephants roaming the musical plains!

Duffie: Do you feel you are performed enough?

Del Tredici: No composer is ever performed enough! [Both chuckle] But it's interesting; it goes in cycles. With great big pieces it just depends. To do a big piece of mine is a real commitment of a budget of a symphony; or when I write with such difficulty, that cuts out many kinds of singers. So I make life difficult for myself. There's no getting around it, but it's what I do!

Duffie: Is it all worth it?

Del Tredici: I don't know if it's worth it or not, but it's what I do.

Duffie: Something else that you do is your teaching. Have you been teaching most of your career as well as composing?

Del Tredici: Mm-hmm.

Duffie: Do you get enough time to compose amongst your classes and lessons?

Del Tredici: My relationship to teaching has always been love-hate. On one hand the teaching is an enormous threat to composing, partly for time because it just takes a lot of time, but more for energy because teaching is an immediate energy drain. You go to class, you teach three or four hours, those students want something and they get it right there. Something like composing and sort of following your muse and having vague ideas of a piece seems very insubstantial in the face of these young sparrows waiting for their worm. So I tend to put composing on the back burner when I do heavy teaching. I've experimented and tried to teach one semester and not the other. The nice thing about teaching is that it's a very secure financial basis, and I need that. Commissions can pay very well, but they're not regular. So I have to teach and I enjoy teaching, but it is another profession. Composing is a profession and teaching is a profession, and when you combine the two it is at your own risk.

Duffie: Do you feel schizophrenic about it?

Del Tredici: Yes, I do! Definitely, particularly in the beginning. My first job was at Harvard, and it was such a thrill to teach there. I enjoyed it, but I stopped composing! I would compose in the summer only, and after about two or three years of that, I thought, "Wait a minute, I'm a composer!" So then I did start the idea of teaching every other semester, but that also makes life hard because schools aren't geared to having you there every other semester.

Duffie: So you have to carve out your own way.

Del Tredici: Well, it helps to win the Pulitzer Prize. When I got that, then I could much more call my own teaching tune. That was one of the enormous benefits of winning something like that, not that you asked...

Duffie: [Laughs] No, I often ask about that, so that's fine; I'm glad you brought that up. Coming back to the teaching just a little bit, are you pleased with some of the talent that you see coming along in composition students?

Del Tredici: I've had some extraordinary talents. In fact, my first year at Harvard one of my students was John Adams. I teach now at City College in New York, and I've had just some amazingly diverse kinds of composers. Interestingly enough, I can remember very much how students are now as when I was a student, and there's so much more diversity of styles. I'll have a minimal composer, a tonal composer, a serial composer. I think I almost envy students now; they can sort of do whatever they want and it somehow is acceptable, whereas when I was a student at Princeton, there was a very strong sense that one had to be an atonal composer, or not be a composer. At that time I suffered from that.

Duffie: Who is it that ultimately decides what music should be written? Is it the composing community, is it the audience, is it the historian?

Del Tredici: It's the composer, I think, and he hopes to find some resonance in the audience. It's not the composing community, really. You just have to do what you do. It sounds kind of trite, but you have to have a sense of yourself. I had composed in my senior year at college. That was the beginning, my first attempt. The next year I went to Princeton, so I was very young, an untried composer. I had written very little and that first year at Princeton was just too high-powered for me. I had very clearly the sense that if I stayed, something in relation to composing would die, so I quit! But I often wonder; I don't know where I got that sense

— 'cause I'd written so little of myself — that there was something there that to be killed or not killed. I don't know whether it was real or not real, but it turned out to be true in the sense that by stopping going to school, I lived in New York for a couple years and I did just do what I wanted to do without too-early or too-critical judgement. Then I went back to Princeton and got a degree, and it was not a threat. Not from the teacher's point of view, but as a student, studying composition in school is a mixed blessing. The "academicizing" of something as disorderly as composing has its risks.

Duffie: On whose shoulders is the burden of sorting out the risks? Is it the teachers, or is it the students?

Del Tredici: Since I really do compose, one of the things I like about teaching composition is that I try very very much not to inhibit their composing. I try to have sense of letting 'em do what they want. Even when you're a composer, you still wanna somehow organize the other person... depending on how much of a control freak you are! But if you're not a composer at all, then you really don't have any idea what's involved. I think students learn incorrectly because there's such an emphasis on analysis in school; they think composing is analysis reversed. The way you would look at a Beethoven sonata, with all of the order and organization one can see after the fact, is in fact NOT the way Beethoven composed! Composing is much more chaotic, and you have to surrender yourself to your impulses

— which one might do very naturally and not think two cents about outside of an academic situation. But it's the old thing — schooling brings a self-consciousness that has its price.

Duffie: Do you have any specific advice for the young composers coming along?

Del Tredici: Hang on to your fantasies, whatever they are and however dimly you may hear them, because that's what you're worth.

Duffie: You receive lots of commissions. How do you decide which ones you'll accept, and which ones you'll either push back or decline?

Del Tredici: I always know the piece I want to write next, or the kind of thing, so I always choose a commission that will allow that piece to be written. For example, no one ever commissioned an Alice work as such from me. I would get an orchestral commission. For example, Georg Solti asked me to write a piece for the Chicago Symphony, and it was just that

— a piece for the Chicago Symphony. I said, "Can I have a soprano?" and he said, [in a somewhat grudging tone of voice] "Okay." I then asked, "Can I have a folk group with saxophones, mandolin, banjo, accordion?" Well, they were very nice and said yes, but I knew that that was the kind of ensemble I wanted, so that's why I accepted.

Duffie: He didn't look at you in horror because of those requests?

Del Tredici: No, no; he said to me, [in a disinterestedly agreeable tone of voice] "Do whatever you want." But the Chicago Symphony has a very enlightened view of such things. Thinking of more traditional expressions of music

Del Tredici: No, no; he said to me, [in a disinterestedly agreeable tone of voice] "Do whatever you want." But the Chicago Symphony has a very enlightened view of such things. Thinking of more traditional expressions of music

— like the quartet or the symphony or the brass quintet — I wish I felt like writing them because a lot of groups ask me, and I want to be able to, but at this point, somehow, I'm afraid to say I will, for fear... I don't know what I fear... that I won't be able to do it. I guess that's always a fear. Although I've never not been able to write something I wanted to write, it is an occupation full of superstition. It's not like composing isn't like something you learn and, "Oh!" . . . you just do it for the rest of your life. When you look at great composers, they had periods where they were wonderful, and then some composers just got worse and worse! Think of someone like Schumann... of course he went crazy, whatever that means... he deteriorated. With Hugo Wolf, all those songs come in a very short span. Someone like Verdi is a great exception. He did everything right — successful, rich, a patriot, everyone loved him, and he wrote his best piece when he was in his eighties. [Both chuckle]

Duffie: Hooray for Falstaff!

Del Tredici: [Chuckles] Yeah, exactly.

Duffie: Are you looking forward to writing your best piece when you're in your eighties?

Del Tredici: Well, I always wonder about Schubert and Mozart; suppose they had lived to be seventy, would they have gotten better and better? I'd love to have seen Mozart gone academic after about fifty.

Duffie: Of course you have one example of that in Rossini. He wrote up to a certain point and then quit writing. He kept living but he essentially quit writing.

Del Tredici: And so did Verdi!

Duffie: Yeah, but he came back to it.

Del Tredici: He came back, but maybe it has to do with operas, too. Maybe it's an opera thing; it's such a horrible thing writing operas, the whole collaborative aspect. They probably get sick of it.

Duffie: With all of your stage works and everything, are there operas in your canon or are they still just mixed media?

Del Tredici: No! I've been afraid to write an opera when I think how it's always been a collaborative element, although I'm thinking about it again. I'm looking at the world of Italian folktales. I even went so far as to read Pinocchio, but I don't know. I'd love to write an opera! It seems to me that I should have one in me...

Duffie: There's sort of a resurgence now of people using the Goldoni stories.

Del Tredici: I don't know those. I just bought a volume of Italian Folktales edited by Italo Calvino [published in 1956]. I brought it with me to Chicago, but have not cracked it.

Duffie: You always bring your ideas with you; are you always working on your pieces wherever you go?

Del Tredici: I'm working on Steps now, which is gonna be done with the New York Philharmonic in March. I brought the score with me to look at on the plane, in my hotel room... Yes, I like to work nonstop, obsessively.

Duffie: Is it just there, or do you actually get some work done on it?

Del Tredici: What I'm doing now is orchestrating it without dynamics, without slurs, without any markings. After that I xerox it and have it bound like a book. Then I put in all of those things that are missing. It's like the final draft. Then I revise it again because when you try to put in all the little tiny things that people take for granted, I'm hearing it more exactly. And in hearing it more exactly I'm less satisfied with it, so it's like a whole other draft. So that's the score I have brought with me, and that's a very good thing to do when you're traveling.

Duffie: Sure. Is there really only one way to perform any of your pieces?

Del Tredici: What do you mean "one way"?

Duffie: One right way.

Del Tredici: Oh, no! That's one of the nice things about performance. Because I'm a performer, I know very well it's wonderful to have somebody think of a way that's better than anything you ever thought of. It's just a dream; you fall in love with them, you wanna marry them. It doesn't happen that often, but it's wonderful when it does... or when a conductor who has real ideas about a piece

— about shaping a piece —that you never had. The thing which is so discouraging to me is a performer who's neutral and just kinda does it without any commitment— especially if they're proficient. I want to know what's wrong? Why can't you get involved? It's very, hard.

Duffie: "Proficient..." sounds like you're equating it with "pedantic."

Del Tredici: Yeah, because so much is still in a piece that you can't write in the score! I mean motion and energy which you're trying to catch when you write down notes and dynamics and phrases. All those are just meant to suggest a sense of flow

— an ebb and flow — and if someone doesn't tune in to that and just literally does what they see, it doesn't come out right. It's like language or inflection. I want the performer to get on to my bandwagon, and somehow I try to give every clue that will help. But if it doesn't work it doesn't, and it's very frustrating because it's like any kind of simpatico; some people you like to be with, and some you don't! Some conductors like to be with my music and it makes others nervous! I think my whole sense of excess and length and pushing things to a certain kind of limit and extreme virtuosity makes more conservative types uncomfortable. I mean my music is unsettling and it's very loud.

Duffie: Are you pushing the limits of music?

Del Tredici: Sure, in the sense that I write very long pieces that I want to be coherent. It's not as though I write just to go on. It could go on forever in a very minimal way, and where you tune in or tune out doesn't matter. [Emphatically] No! If I write for an hour, I want to grip the audience for an hour. I want to be the boa constrictor wrapped around that pig of an audience for one hour.

Duffie: Now, now... Shouldn't you be nicer to the audience?

Del Tredici: No, I have a certain aggressive view of the audience. It's the composer's way to have power. I want to be the Svengali that just hypnotizes the audience and has it under my control for one hour.

Duffie: What do you expect of that audience that comes to hear a piece of yours?

Del Tredici: To love it and me.

Duffie: Really?

Del Tredici: Mm-hmm! That's all it is.

Duffie: Do you succeed?

Del Tredici: I try!

Duffie: Do they succeed?

Del Tredici: [Thinks for a moment] Sure! Everybody wins. If they love me, I'm very happy; and if they've enjoyed the piece, they've had an experience that's pleasurable. So they're happy.

Duffie: You mentioned that you're shying away from the collaborative effort. Is that one of the hidden reasons that your pieces are so long, that you then don't have to collaborate on a program with anybody else — it's entirely your program?

Del Tredici: It just grew up willy-nilly that way. I began with a simple text, and then it got longer and longer. I found The Annotated Alice, which is Alice in Wonderland with annotations by Martin Gardner. Because he included a lot of extra poems on which the Carroll poems are based, he, in fact, gave me a libretto. So I got used to setting all these different poems.

Duffie: But if you write a piece which is an hour, you have the half of the program to yourself. If it was a 20-minute piece, there'd have to be something with it.

Del Tredici: Oh no, I'm not that megalomaniacal. [Laughs] Not really. But Alice in Wonderland has a story. It's operatic in a sense that it's a way of getting the audience out of the normal concert hall format; although I like creating for that format but changing the terms of it. It's a little like Romeo and Juliet or Damnation of Faust by Berlioz. They are for the concert hall, but yet they're like an opera; they have a story and a progression, and I like that. I don't know why, but it appeals to me.

Duffie: They've occasionally staged those Berlioz works; do you ever want your pieces to be staged?

Del Tredici: Well, they made a wonderfully successful ballet of In Memory of a Summer Day. [This was entitled Alice.] Glen Tetley choreographed The National Ballet of Canada. It never occurred to me to do that, but he made it completely visual. I think my music is very visual and very three-dimensional. So I would like someone to make me write an opera!

Duffie: [Obliging the request] Write an opera!!!

Del Tredici: Thank you. [Much laughter]

Duffie: Get all the managements of the companies together, and collaborate to take it around!

Del Tredici: I'd love to do it. It exhausts me to think about all that...

Duffie: Have you exhausted the Alice potential?

Del Tredici: Oh, no. I have two more in my trunk which I've already mostly written. I have written a lot of pieces over the years just 'cause that's what I'm writing, and then I stuff them in the trunk and pull them out when a commission comes along. But I got very interested in Alice for some reason; in fact, it started with the Chicago Symphony. My second commission was for an orchestral piece, and I wrote something called March To Tonality in 1985. I think it was the first non-Alice piece. Then I got interested in writing other works like that, and wrote something called Tattoo for orchestra in 1986. Now I'm writing Steps for orchestra. When I look at all three, they have similar qualities but a very different atmosphere than the Alice pieces. It's hard to characterize yourself, but they certainly are darker and have a kind of... I wouldn't say Boléro-like quality, but there's a kind of idea that will run through the whole piece, a kind of inexorable, repetitive rhythm. It's just very different to me than the kind of music I wrote in Alice. Also, I think I'm starting to discover the world of dissonance, and in a sense I'm going through the history of tonality in my own music! If you can think of myself beginning tonally with a work like Final Alice, which is quite pure in its use of tonic-dominants and other chords, and gradually I've added more and more dissonance in these orchestral pieces, so that I'm doing the progression from Schumann through Mahler within my own works.

Duffie: And yet the rest of music seems to be going from Mahler back through Mozart in its tonality and simplicity!

Duffie: And yet the rest of music seems to be going from Mahler back through Mozart in its tonality and simplicity!

Del Tredici: Oh, well, who can tell the direction of music nowadays? You're speaking in general?

Duffie: Yes.

Del Tredici: I suppose yeah, you're right. Well, I guess it's a normal thing. Nothing stays the same. I've gotten used to being tonal. To me it's completely natural. It just is the air I breathe, so naturally I get interested in upping the dissonance level. I write quite weird chords and it becomes really quite atonal, although I never think about being atonal or not. I just simply get it to sound the way I want to, and maybe when it's all over I look and go, "Jesus, what is this chord?" But I do notice when I take my own temperature as it were, that it becomes more and more dissonant. So suddenly I'll end up being atonal in 1996 when the rest of the world has gone into Mozart-like white notes.

Duffie: Do you think that music is heading in a much more simplistic direction?

Del Tredici: Certainly certain kinds are; look at minimalism. That's screaming and saying music can be this simple. We did lose touch with some of the most elemental transports of music when we got so involved with atonality and the complexity of musical rhythms.

Duffie: Is there any hope for music?

Del Tredici: Well, there's always hope, as long as there are breathing, bloody composers.

Duffie: We've kind of been dancing around it a little bit, so let me hit you with the big philosophical question

— what's the purpose of music?

Del Tredici: The purpose is pleasure, but I didn't make that up. I always hang onto this anecdote... Someone asked Debussy, "Mr. Debussy, what is your method?" He said, "My method is pleasure," and it's true. I compose because it brings me enormous pleasure and excitement. Something comes out of me I didn't know was there, and I try to capture it and write it down. Then that is me; somehow I've made permanent some aspect of my personality. You can tell a funny story or a joke and see delight on people's faces for the moment, but then it's gone! Whereas if I can put whatever that is about myself that is me into a piece, there it is and that's irresistible! That's never dying. That's one thing that's very appealing, although I've never been asked that question. It's just fun to do! Does it have to be a lot more than that?

Duffie: Not necessarily! [Both laugh]

Del Tredici: Can't you just think of composers as some sort of athletes?

Duffie: Is music an athletic contest?

Del Tredici: No, but it totally involves the body and the brain. You're very alive, the way I often think of when somebody is doing a terrifically wonderful dive or running a race; you're just enormously alive. Especially nowadays, too often you think of composing as a mental thing. Nobody really has any idea what goes on; you just think it up. You try real hard, you shut your eyes, or you put on incense

. You don't think that it's physical, but because I'm a pianist, I compose at the piano and I run around and jump; it's completely physical. When I'm on a hot streak, I often wish there were a video camera on me, 'cause I'd like to see what I'm doing and see how much translates into body language.

Duffie: Have you thought of putting a camera in your studio to catch that?

Del Tredici: [Bursts out laughing] No! My electronics budget is too modest.

Duffie: Speaking of electronics, are you pleased with the records that have been made of your music?

Del Tredici: Yes! I've been thrilled that long pieces such as Final Alice and In Memory of a Summer Day were even recorded! But it's funny... I think because I've had works recorded, in a sense I sometimes compose with a record in mind. I'll think, "This section won't really come out unless it's on a record." It's just the whole idea that you can balance things and get an ideal balance on a record that you could never get in a concert hall. Especially for my works, records are almost essential because I use a soprano and a very large, active orchestra. In reality they have to have heavy amplification which distorts the voice unless it's a very sophisticated hall

— which most concert halls aren't; they're old, and sophistication in electronics is new. So there's always a terrible loss because the voice is distorted! Or if you don't amplify it, you don't hear it. So a record is perfect because you hear them in the right balance and there's no sense of distortion.

Duffie: Does the disc then set up an impossible standard for future live performances?

Del Tredici: I don't know; yes and no. But what I love is if people who want to do my music just hear the record, they have no idea what's involved when you really have a roaring 104-piece Mahler orchestra and a soprano on a low C, and they're supposed to be the same level. For some reason I have no regard for realistic balances, and I will write a soprano on a low C if that note down there is climactic. And I'll have a big orchestra because there is amplification and it can be heard. It may mean I'll have to have very extraordinary amplification, but I take that risk.

Duffie: This is what you want, and so you let the performers accomplish it?

Del Tredici: Yeah! Exactly. And I think that kind of thing is what feeds the more imaginative, inventive performers! They're looking for something; they're looking for a mountain that hasn't been climbed, or a desert that hasn't been crossed! And, you know, that's fun! In fact, my music has appealed to performers and conductors who like a challenge. Phyllis Bryn-Julson has said to me, "I love singing your music; it opens me up! It's only your music does that. I don't know what it is; it's about jumping around like that." She has also told me, "Nobody else writes that way; I never can do what I can do. In fact, I didn't know I could do that until you asked me to do it!" So there's a certain reciprocity that's quite pleasing.

Duffie: Thank you for being a composer

— for all of your works so far and for those yet to be created!

Del Tredici: What a nice interview! You're very good. You make it very easy. You were able to bring out things I've never said with your good questions. Thank you.

Duffie: [Genuinely flattered by the remark] Thank you so very much.

Generally recognized as the father of the Neo-Romantic movement in music, David Del Tredici has received numerous awards (including the Pulitzer Prize) and has been commissioned and performed by nearly every major American and European orchestral ensemble. "Del Tredici," said Aaron Copland, "is that rare find among composers — a creator with a truly original gift. I venture to say that his music is certain to make a lasting impression on the American musical scene. I know of no other composer of his generation who composes music of greater freshness and daring, or with more personality."

Much of his early work consisted of elaborate vocal settings of James Joyce (I Hear an Army; Night Conjure-Verse; Syzygy) and Lewis Carroll (Pop-Pourri, An Alice Symphony, Vintage Alice and Adventures Underground, to name just a few). More recently, Del Tredici has set to music a cavalcade of contemporary American poets, often celebrating a gay sensibility (three examples: Gay Life, Love Addiction and Wondrous the Merge). OUT Magazine, in fact, has twice named the composer one of its people of the year.

Over the past several years he has ventured into the more intimate realm of chamber music with String Quartet No. 1, Grand Trio (brought to life by the Kalichstein-Laredo-Robinson Trio and recently printed by Boosey & Hawkes), and — harkening to his musical beginnings as a piano prodigy — a large number of solo-piano works (Gotham Glory, Three Gymnopedies, Ballad in Yellow, S/M Ballade, and Aeolian Ballade).

Still, the extravagant Del Tredici remains at large and busy. In May 2005 Robert Spano conducted the Atlanta Symphony and Chorus in the premiere and subsequent recording of Paul Revere's Ride, recently nominated for the 49th Annual Grammy Awards as the Best New Classical Composition of 2006. November 2005 held the world premiere of the melodrama Rip Van Winkle with the National Symphony Orchestra conducted by Leonard Slatkin and narrated by world famous Broadway actor, Brian Stokes Mitchell.

In recent years several Del Tredici CDs have abounded: on Deutsche Grammophon, an all-Del Tredici CD (released in its highly-regarded "20/21" series) featuring conductor Oliver Knussen, soprano Lucy Sheltonand the Netherlands' ASKO Ensemble; on the Music and Arts label, a pair of recent Del Tredici song cycles featuring soprano Hila Plitmann with the composer at the piano; on Dorian, In Wartime, a spectacular new work for concert band; and on Koch, a selection of piano compositions played by Anthony de Mare. Among past recordings were two best-sellers — Final Alice and In Memory of a Summer Day (Part I of Child Alice); the latter work won Del Tredici the Pulitzer Prize in 1980.

March 2007 marked David Del Tredici's 70th birthday, with concerts given throughout the year, including the premiere of Magyar Madness, a chamber piece for clarinet and string quartet, commissioned by Music Accord for clarinetist David Krakauer and the Orion String Quartet. Another premiere was S/M Ballade for solo piano which was commissioned and performed by Marc Peloquin.

Recent publications include a collection entitled Songs for Baritone and Piano as well as the score and parts for the piano trio entitled Grand Trio. A second printed volume of solo piano pieces is in progress which will include Gotham Glory and Three Gymnopedies.

Distinguished Professor of Music at The City College of New York, Del Tredici makes his home in Greenwich Village.

David Del Tredici is published exclusively by Boosey & Hawkes.

© 1990 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in a dressing room downstairs at Orchestra Hall in Chicago on January 8, 1990. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1992 and 1997. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2011.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website,click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.