Mignon Dunn Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

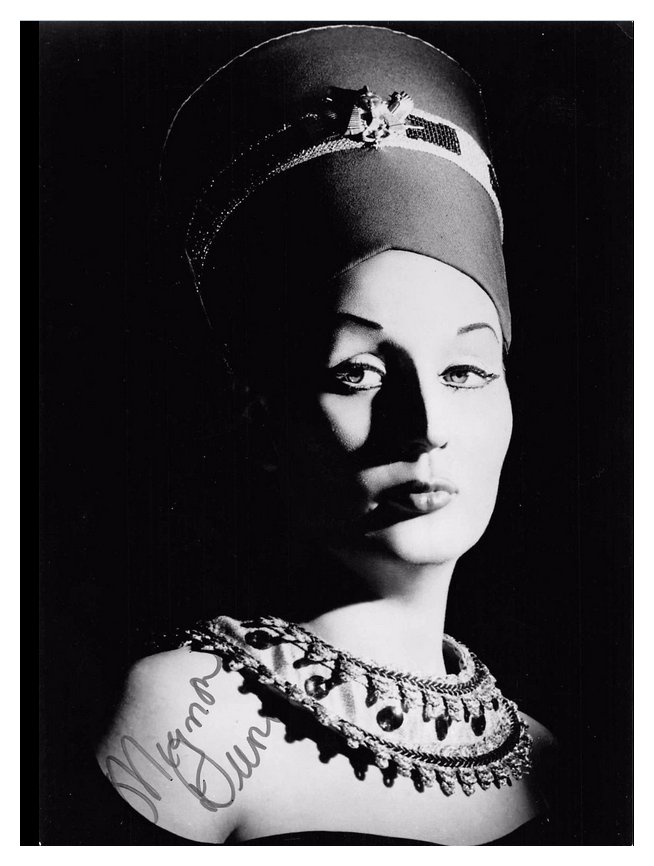

Mezzo - Soprano Mignon Dunn

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Mignon Dunn has sung the leading mezzo-soprano roles in the most important opera houses of the world. In Europe, she has sung at La Scala, Milan; the Vienna Staatsoper; London’s Royal Opera, Covent Garden; the Paris Opéra; Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre; Teatr Wielki, Warsaw; the Hamburg Staatsoper; the Deutsche Oper Berlin; and the opera companies of Frankfurt and Dusseldorf. In South and Central America, she has performed at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, the Opera Nacional in Chile, Mexico City’s Bellas Artes, and the Opera of Puerto Rico. In Canada she has performed with the Canadian Opera Company in Toronto and the Opéra de Montréal. In the United States she sang at the Chicago Lyric Opera, the San Francisco Opera, the Santa Fe Opera, the Opera Company of Boston, the Opera Theater of Detroit, and the New Orleans and Miami operas. At the Metropolitan Opera in New York she sang over six hundred and fifty performances over a span of 35 years.

Dunn is known especially for her portrayals of the dramatic Italian roles such as Amneris in Aïda, Azucena in Il trovatore, Eboli in Don Carlo, both Laura and La Cieca inLa gioconda, the Princess in Adriana Lecouvreur, and Santuzza in Cavalleria rusticana. Her French repertoire includes Dalila in Samson et Dalila and Giulietta in The Tales of Hoffmann, Hérodiade, as well as Dulcinée in Don Quichotte and Carmen, which she has sung over 400 times in four different languages.

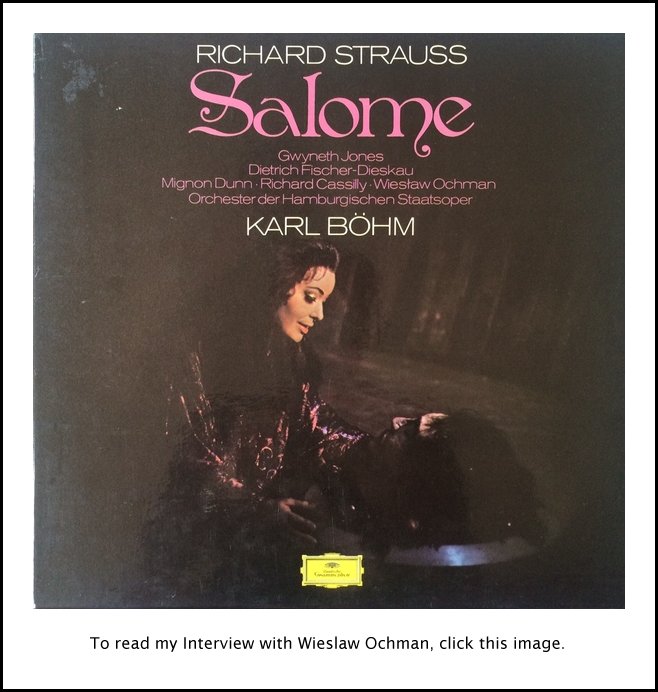

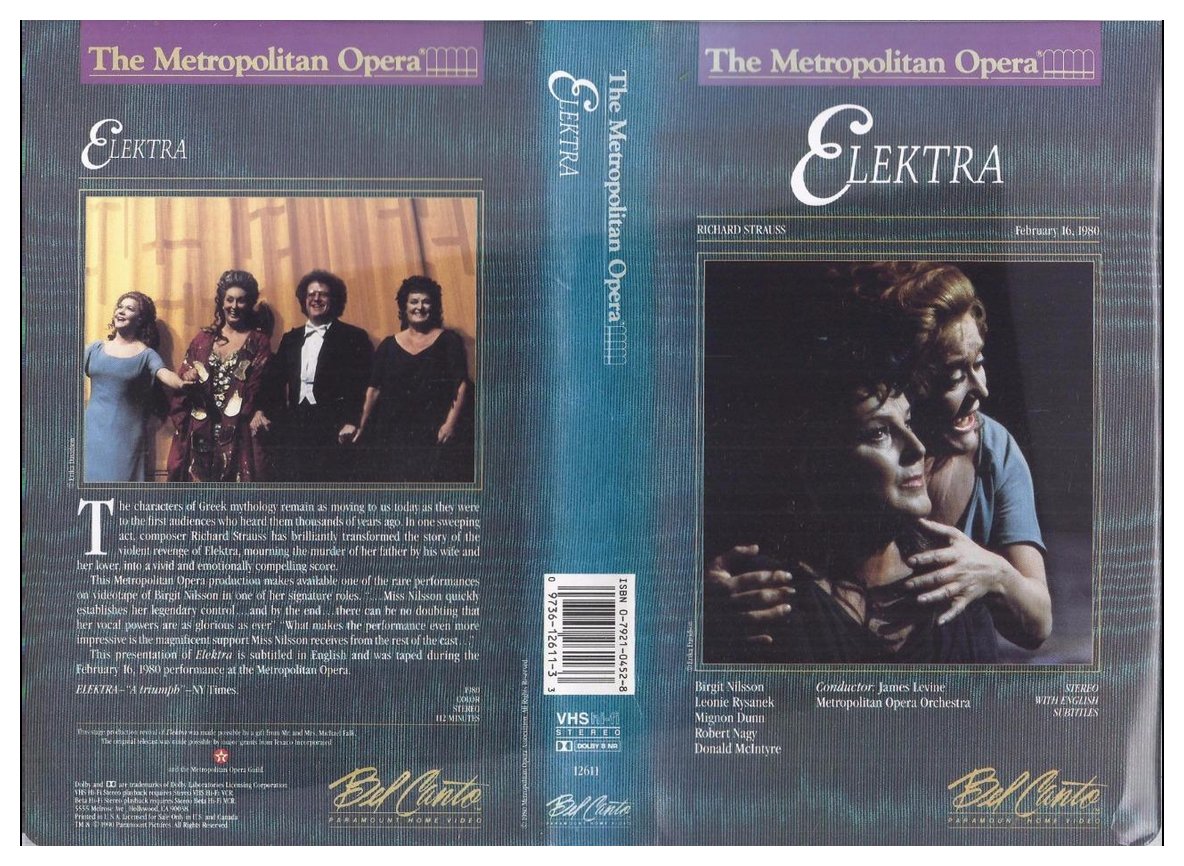

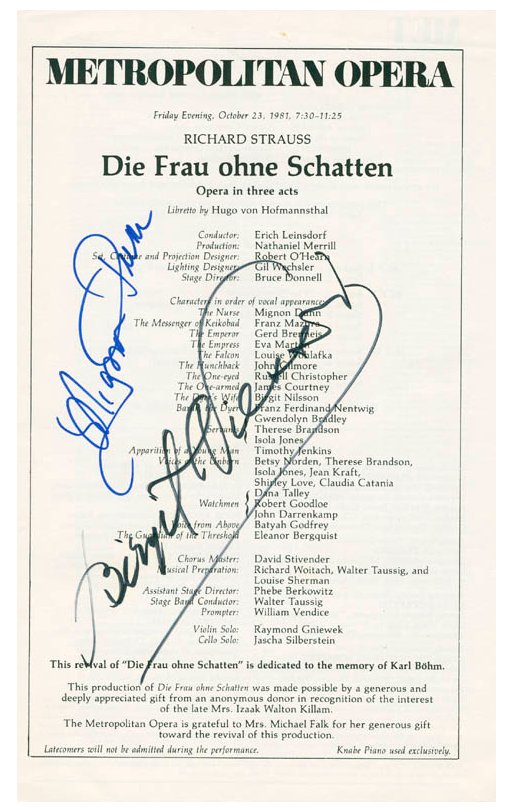

Her German repertoire has embraced the leading mezzo roles in different productions of Wagner’s Ring, Ortrud in Lohengrin, Kundry in Parsifal, and Venus in Tannhäuser. She has also given many performances of Strauss’s operas including Klytämnestra in Elektra, Herodias in Salome, and the Nurse in Die Frau ohne Schatten. She has sung Kostelnička in Jenůfa, Jezibaba in Rusalka, and Kabanicha in Katya Kabanova in Czech as well as Marina in Boris Godunov in Russian. Her Spanish repertoire includes Goyescasand La vida breve.

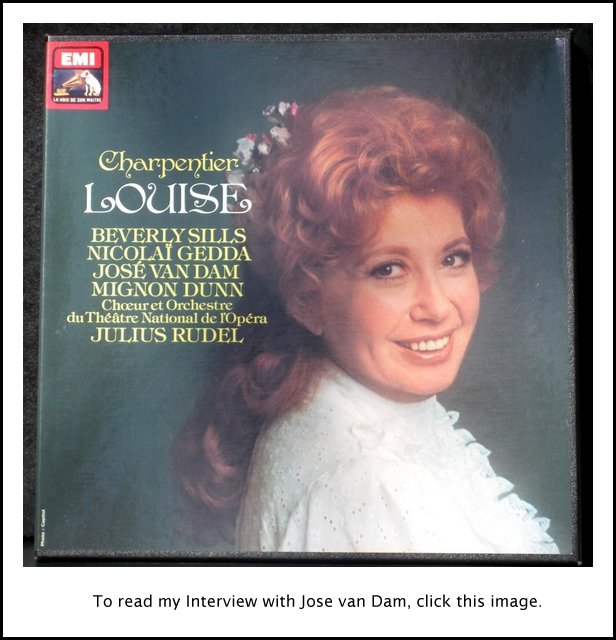

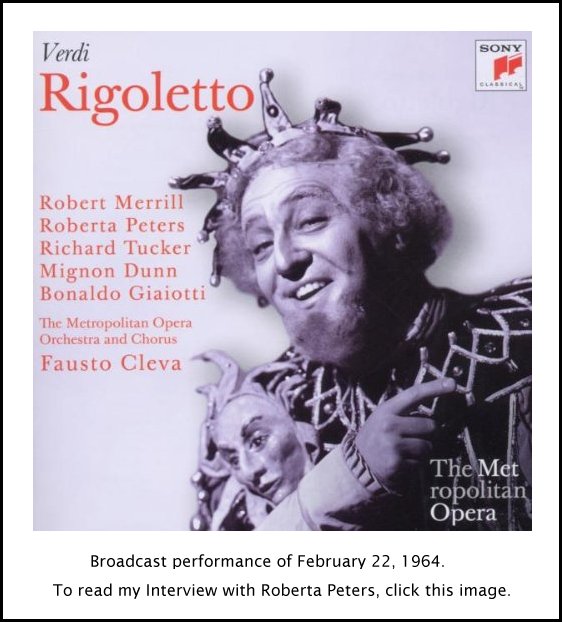

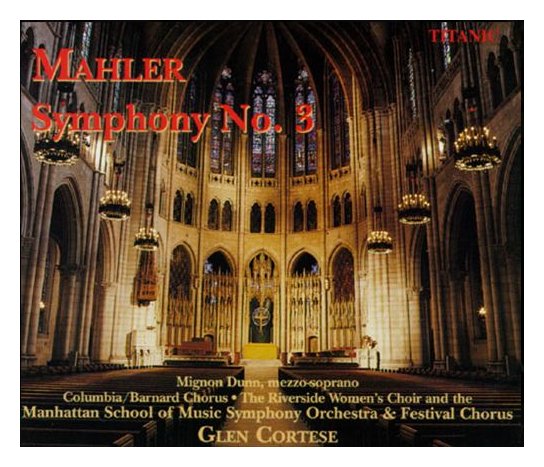

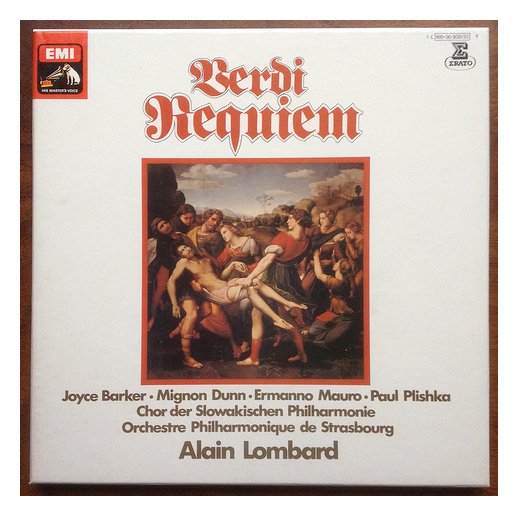

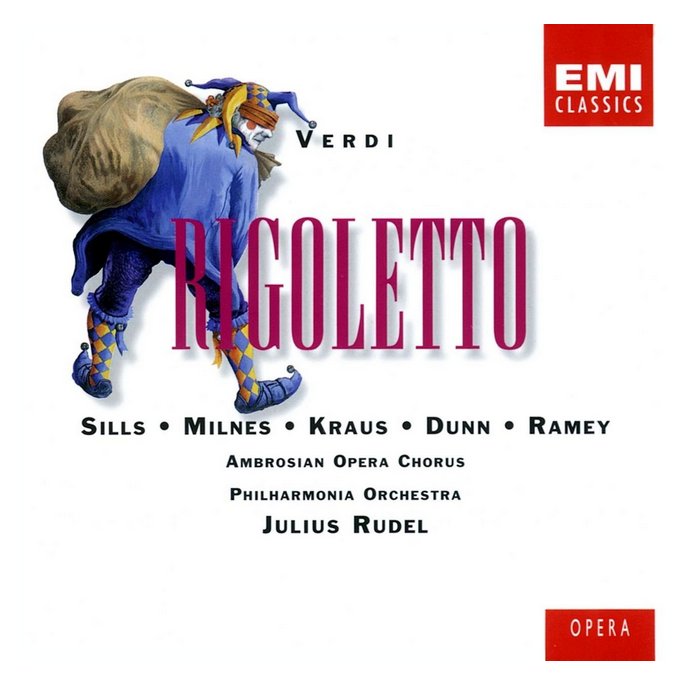

Ms. Dunn has performed recitals all over Europe and the United States and has sung with many major symphony orchestras, including the New York Philharmonic and the orchestras of Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Detroit, Cincinnati, Hamburg, and Vienna. Her varied repertoire has especially featured the works of Mahler, Ravel, and Verdi. Ms. Dunn has recorded for EMI, Erato, and Deutsche Grammophon. She has conducted master classes extensively in the United States, Germany, Austria, Italy, Israel, China, and Japan.

She is widely known as a professor of voice and has taught on the faculties of the University Texas at Austin, the University of Illinois, Northwestern University, Brooklyn College, and for many years at Manhattan School of Music.

Ms. Dunn was married to the late conductor Kurt Klippstatter and lives in New York City.

Mignon Dunn sang with Lyric Opera in several seasons (as noted in the chart farther down on this webpage) and during her double stint in 1984 we arranged to meet at her hotel. She was very willing to share her insights, and was quite funny at times about what she was doing or how she thought it should be done.

I began with the obvious question . . . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Have you ever sung the role of Mignon [the title role in the opera by Ambroise Thomas]?

Mignon Dunn: [Laughs] No. I covered it years ago for the New York City Opera, and I've sung two arias from it but it's a little too light for me, really.

BD: Have you done any other French operas?

MD: I've done over 400 performances of Carmen in four different languages — German, Italian, English, and the original French. I've sung it from Finland to Israel, and from Chile to Canada, and I've sung the role of Delilah a great deal, as well as Don Quichotte, and Hérodiade. I would love to do Hérodiade again. It's a marvelous opera.

BD: What makes it marvelous?

MD: The music, what else? It would need a great production, but there are so many goodies in it that you go from one goodie to another goodie.

BD: But does it hold together?

MD: Yes, it does hold together.

BD: Why is it not more well-known?

MD: I really don't know. It takes five "first" singers — like a French Gioconda.

BD: Let's talk a bit about Wagner. Which roles have you sung?

MD: I've done all the Ring roles for my voice at the Met many many times. I still wait in the wings for special moments in all the operas, such as the Todesverkündigung scene with Vickers and Behrens which was really spectacular. I loved the Chereau production of Walküre. I thought it was fantastic, particularly well done. I've also done Ortrud and Kundry. Ortrud is more fun to do. Kundry is hellish-hard. It's an incredible part, but very difficult.

BD: Do you like playing evil people?

BD: Do you like playing evil people?

MD: I like a good part. It doesn't have to be evil; it could be funny, although I don't get as many funny parts as I wish I did. I am a funny lady and I love to get funny parts, but everybody hires me for these "chewing-up-the-scenery" parts. That's why I liked the role in Arabella so much because it's a silly, funny lady. I mean, how many operas do I get to waltz in? I'm not particularly interested in doing Rienzi, which is about the only Wagner that I haven't done. It suits my voice, and I don't agree that it is hard on your voice if you sing it, and I don't agree that Strauss is hard on your voice, either. This is my big Strauss year. After I finish Arabellaand Frau here, I go to Nice forCapriccio, and then after a Delilah, I do Herodias in Salome.

BD: Do you like the life of a wandering minstrel? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my interview with Gwyneth Jones.]

MD: It goes with the territory, it goes with the business. It's difficult to adjust to the different houses. But I love being here. Chicago is a fabulous town with a fabulously run opera house. Ardis Krainik is a wonder. It's a great feeling in the house. There is great morale, everything works, and it's fabulous. I haven't done the Frau

for about 4 years, and I'm re-working it now. I usually re-work everything every time I get it out again.

BD: Do you go back beyond the scores to letters of composers and writings, etc.?

MD: No, I don't. I think that is the conductor's job, unless you're very confused about something. I'm doing a Janáček opera next year, and for that I'll do as much research as I can because it's not a work you see very often. For every work, though, it's important to go to the score. Of course I've read the Arabella book and the Carmen book, and I've done as much research as I can on the libretti from various things that I've done. But the letters, no. My husband [Conductor Kurt Klippstatter] does.

BD: Does he give you a lot of help, a lot of pointers?

MD: Indeed he does.

BD: Is it fun being married to a conductor?

MD: Most of the time it is. It's made me a little more tolerant with other conductors because they do work awfully hard. But the conductor is really where the show hangs. If you don't have a really good conductor, you don't have a good show. You do the best you can anytime, but it's a joy to have a good one.

BD: Tell me about Fricka. She seems to be yelling all the time at Wotan.

MD: She's not yelling just to give orders. She's really right, and people who are right are usually the most difficult people. When one doesn't want to hear it, the truth is the most unpleasant and unfriendly thing one can think of. But Fricka [in Walküre] is going by the book, and she's absolutely convinced that she's right. It's a different character from the Fricka in Rheingold, who is concerned about the recklessness of her husband but will go along with it. But she has been so concerned for so long, and he has hurt her for so long, that she will have no more of it. She cannot accept it. If he had been willing to give in a little bit, it might have been different. But that wouldn't have been as good a scene. I did a production in France that was set in turn-of-the-century with bustles. You can take it out of the context of Gods and Goddesses and it works. I think every woman has had a similar discussion with her husband.

BD: Would she have been happier if Wotan had been less reckless?

MD: Sure. She was a housewife, and if she'd been human she would have been very happy with someone who had a 9-to-5 job rather than someone with irregular hours.

BD: Does she have a martyr complex?

BD: Does she have a martyr complex?

MD: [Firmly, but with a smile] Stop trying to make her into something she isn't! She's just a nice housewife that is stuck with somebody who is an absolute nut

— an attractive, brilliant, reckless, selfish, egotistical, totally charming nut.BD: You say he has hurt her. Has she hurt him?

MD: No. She has not understood his recklessness.

BD: Why did they get together in the first place?

MD: She was a different person. They were young, and those things develop over the years in marriages. There is a lot of compromise that must be made, and Fricka has compromised until she is not going to do that any more. She says, "I'm right and you're wrong, and you'd better agree with it, buddy!" And he has to agree because she is right. He's never confided in her why he's doing all these things, but he's been power-mad for a long time. He looks at things on a bigger scale, and she looks at things on a smaller scale. But he is always finagling, always trying to wheel and deal. She doesn't understand those things. She's a very straight-forward person.

BD: She doesn't crave power at all?

MD: She doesn't do it for power. She has resorted to power because that is her last resort with him. Remember, when I play a character, I have to believe what they believe because if not, I cannot make it work for me. Ortrud, for example, in her mind, is right. The whole big deal with her is that she is pagan and doesn't understand the habits and beliefs of Christians. This is a totally different ball game. In our countries of the West, we find it difficult to understand Muslims and people of eastern cultures. It's a different set of rules that they go by.

BD: So do you temporarily adopt those rules for yourself?

MD: Yes. When I'm in the opera, of course, but it stops when you go offstage. She's not doing it to be mean, it's just the way she thinks. If you're going to crawl into these characters, you have to try to find out what they think and why they do what they do.

BD: Does she manipulate Telramund?

MD: Yes. She is very manipulative.

BD: Is he weak?

MD: No, he is just one-dimensional.

BD: Do you like the character?

MD: It's not that I like it, it's just an interesting part to play. Obviously my kind of morals don't go that way at all, but in order to play a character, I do think that you have to believe in what the character believes in. Sometimes you say, "Gee, and I'm getting paid for this, too!" You can really rip into things, but I don't think that you equivocate things. I did many Carmens, but I don't go around looking like Carmen in my private life, or acting like her, either.

BD: Are there some roles you don't accept?

MD: What suits you vocally is the first consideration. I would love to have done Octavian because I could have sung it, but type-wise I was out of it immediately. Nobody would believe I was a young man. So you have to accept the fact that there are certain roles that you are more suited to than others. But there are certain roles that interest me more than other roles. They are more interesting parts. The characters are more interesting, and the music is more interesting, too. Waltraute is similar to Brangaene in devotion to father/mistress. Waltraute is desperate and she cannot possibly understand Brünnhilde, just as Brangaene can never understand Isolde. There is not real communication between the two in each case. They are speaking on two different planes. That's the way Wagner wrote it, and that's what makes it so interesting.

MD: What suits you vocally is the first consideration. I would love to have done Octavian because I could have sung it, but type-wise I was out of it immediately. Nobody would believe I was a young man. So you have to accept the fact that there are certain roles that you are more suited to than others. But there are certain roles that interest me more than other roles. They are more interesting parts. The characters are more interesting, and the music is more interesting, too. Waltraute is similar to Brangaene in devotion to father/mistress. Waltraute is desperate and she cannot possibly understand Brünnhilde, just as Brangaene can never understand Isolde. There is not real communication between the two in each case. They are speaking on two different planes. That's the way Wagner wrote it, and that's what makes it so interesting.

BD: How can you as Waltraute play the scene knowing that it's hopeless from the start?

MD: How can any actor, who knows the end of the play, portray the character? You go out and play the scene the way the scene is played. It's the old thing you learn in acting class

— who am I, why am I, what do I want in this scene? You have to play it as if you've never played the scene before and will never play it again.

BD: Do you ever get so caught up in the opera you're doing at the moment that you are surprised by what happens?

MD: That's very interesting. I haven't had that happen, but it is very interesting. You find yourself caught up in things and weeping sometimes at a desperate situation. I find myself in tears at the end of the second act of Arabella. Adelaide's whole world is crumbling around her and I just weep real tears. There is never a time when I've done Amneris in Aïdathat I've not come off the judgment scene without tears in my eyes.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You never want to just chase the two of them out and say, "Be off!"?

MD: You're like newspapers

— you want me to say something because it's controversial, but it's just not so.

BD: [Reassuringly] No, I'm just trying to find out what makes you tick and what makes these characters tick.

MD: Well, I just go on with a very honest feeling about them. You try to work it all out. There are certain things in certain operas that for maybe half a page are just vocal technique which you must think about. You just take it out of context and say, "This is the note I must be careful of now," and it must be set up vocally. Those are the things in opera that you will not find in a straight play. Most of those things are worked out before you get to the rehearsals, and those kinds of things are intertwined with the character. But you don't stop acting and reacting when you stop singing. There are things we can do, especially if you are able to play off another person very well. You can improvise a bit, but you still have to keep that core, and these are like little extras.

BD: You mentioned that Kundry is very hard. Is there a special peace for you in the third act?

MD: That is a total relaxation. It's like a deep breath and your face is washed clean from the inside. That is where you just weep buckets, honestly. If you have a fabulous Parsifal, it's just fantastic and beautiful. The problem with Parsifal is to stay cool because the music so glorious. If you react to everything that happens in the first act (where you don't have too much to sing), you have to be careful not to give too much of your own emotions later in the opera when there is more to sing. I've worked awfully hard on this part and feel I've only scratched the surface of it. It's so massive an opera, and so technical vocally, that there is so much to it.

BD: Is Parsifal too long?

MD: No, but Meistersinger is! [Both laugh] I'm dying to do light roles like Gerolstein. I also do master classes and I very much enjoy working with young singers.

BD: Are young singers today as good as young singers were 20 years ago?

MD: You bet they are! There is an absolute wealth of young singers today. I don't know if they're better, but they're damn good. There are a lot of wonderful voices in all categories.

BD: Is there enough work for them all?

MD: Of course not, but there is more work than there was. So it's better than it was. Opera gives birth to more opera because people feel it is a wonderful art form, and there's nothing like live entertainment. It is important to look at many things. It's good to look at a good sports event or a good prize fight, or see a good rock group or a good comedian. It all belongs to our business. I would have gone to the Michael Jackson concert but I couldn't get a ticket!

BD: Tell me just a bit about your own studies.

BD: Tell me just a bit about your own studies.

MD: I really am a mezzo and not a contralto. My mentor and teacher was Karen Branzell. I went to her when I was 19 and was with her quite a while. She was a fabulous lady. I sang for the Met when they were on tour to Memphis when I was 16 or 17. Then I came to New York to sing for them when I was 18 and they arranged auditions for me with her and with others to see who I would study with. I continue to study today with another teacher.

These days I also give master classes. I'm very technical about certain things, and I seem to be able to explain it very well.BD: Do you ever work on Wagner or are they too young for that? [_Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Paul Plishka._]

MD: I don't work on Wagner or Strauss, but some of them could. There are certain people where it would build their voices very well. It's one of those things

— you either have it or you don't. Visually it's like you cannot make me three feet tall and Japanese. Vocally you either have the voice for the repertoire or you don't, and if you have it, I don't think it's going to hurt you.

BD: When can you tell if one has a voice for it or not?

MD: That's completely individual. There is no hard-and-fast rule. Many famous singers sang things you'd never expect from them when they were early in their careers.

BD: Are there any parts you'd love to sing but are not for your voice?

MD: I'd love to sing Minnie in Fanciulla del West. I think she should have been a mezzo. I'd love to sing Tosca or Senta, and I get asked every year to do Lady Macbeth, but I turn it down. Just this year I'm judging the Met auditions for the first time.

BD: What do you look for when you judge?

MD: I'm very practical and note if they can they make a good career in a big house That doesn't mean they have to sing loud, but you know if it's a major voice by the quality, and whether they have a sense of drama. It's that certain thing. My friend Francis Robinson, a longtime assistant manager at the Met, was asked what a star did, and he replied that he sparkles.

BD: Are there some who don't make it that should?

MD: Yes.

BD: Are there some who do make it that shouldn't?

MD: Yes, but they don't last long. If you wonder why someone is there now, you can probably bet he won't be around in three years. Generally it's a problem of discipline or lack of consistency. And sometimes they are pushed into a specialty which is a little ahead of them and they ruin their voices.

BD: What advice can you give to those who should make it but don't?

MD: Find a new teacher and re-evaluate the situation. But keep at it. Everybody goes through a bad time, and it can last five years. It also depends on where you are when you hit the bad time

— whether it's later or earlier.

BD: Tell me a bit about your recordings.

MD: You have to act with your voice on them. It's so important to have a feeling of presence when making them. I wish they could have recorded this Arabella because I don't see how you'd ever get a better cast. The emotions are layered and complicated, not just straight joy, sorrow, happy, sad.

Mignon Dunn at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1975 - Elektra (Klytämnestra) with Schröder-Feinen, Neblett, Tyl, Little; Bartoletti

1978 - Salome (Herodias) with Bumbry, Bailey, Ulfung, Little; Klobučar (Wieland Wagner production)

1979 - Tristan und Isolde (Brangäne) with Vickers, Knie,Nimsgern, Sotin; Decker

1980 - Ballo in Maschera (Ulrica) with Scotto, Pavarotti, Nucci, Battle, Voketaitis,Macurdy; Pritchard, Tallchief, Frisell, Conklin

1984 - Arabella (Adelaide) withTe Kanawa, Wixell, Daniels, Greer, Korn; Pritchard, Tallchief

Frau ohne Schatten (Nurse) with Marton, Johns, Nimsgern, Zschau; Janowski, Corsaro

1986-87 - Gioconda (Cieca) withDimitrova,Ciannella, Welker, Milcheva, Plishka; Bartoletti, Tallchief

-- Names which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on this website. BD

BD: What's the role of the critic?

MD: A critic must be objective, and there are many good critics. Any critic who gives you only bad reviews, or only good reviews, or projects something before it's been done and says it will be great or it will be terrible, is not a real critic. Mr. Von Rhein in the Tribune is excellent. Mr. Ardoin in Texas is also fantastic. Martin Bernheimer in California (who won a Pulitzer) is also a fine critic. Andrew Porter in the New Yorker is certainly a good one. There are times, though, when I read one and fall out of bed laughing. One said some not very complimentary things about me and went on to say that I ruined a certain aria... but that aria had been cut and I did not sing it at all! If they say in a roundabout way, "I just don't like her," or if they say, "everything she does is wonderful," that's just nonsense. But they're going to do it. I don't read them unless somebody brings it to me.

BD: Aren't you happy, though, if you've given a great performance and the critic says it was a great performance?

MD: Sure, but you know yourself if it's been good or bad. Obviously, you always try to do your very best, but you have a level that you try not to go under. Sometimes if you have a real dog of a performance it's because you don't know the part, or you're doing it too soon, or it's not right for you. Unfortunately, when you get to a certain strata it's hard to try out parts. Ideally you should be able to try out parts where it doesn't count that much. But what happens is you do your parts first in a major opera house and you make your mistakes in front of 4000 people. This is unfortunate. So, you have to do your preparation and keep in shape. You don't get in shape, you keep in shape.

BD: Wagner is special for you, but you also do a wide range of roles.

MD: I love Wagner, but I would hate to only sing Wagner. Somehow I've gotten a reputation as a Wagner specialist. I just went to Warsaw, Poland, and did Don Carlos and also a concert. I love the Poles. I could have sung until 4 AM if I'd had voice. They are fabulous people, and it breaks my heart to see what they have to put up with.

BD: How much does a political situation

— or simply day-to-day life— affect the way you perform an opera?

MD: You think about it, especially if you're 100% American and chauvinistic about it as I am. When I sing behind the Iron Curtain I just want to send so much love out to them, and I wish I could do something for them and help them. You have to remember that Poland and Hungary didn't choose that particular political situation. They've been stepped on, and I feel very sorry for them. One time at a restaurant, a man came up to us while we were having a good time and said, "You're American. I know it's too late for me, but could you help my son?" And a doorman said, "Ah, you're American. Take me with you. It's not that we suffer so much, but it's so boring, it's so gray." We really don't know what we have here in America.

MD: You think about it, especially if you're 100% American and chauvinistic about it as I am. When I sing behind the Iron Curtain I just want to send so much love out to them, and I wish I could do something for them and help them. You have to remember that Poland and Hungary didn't choose that particular political situation. They've been stepped on, and I feel very sorry for them. One time at a restaurant, a man came up to us while we were having a good time and said, "You're American. I know it's too late for me, but could you help my son?" And a doorman said, "Ah, you're American. Take me with you. It's not that we suffer so much, but it's so boring, it's so gray." We really don't know what we have here in America.

BD: Doesn't having opera help in any way to relieve the boredom?

MD: Of course, and they have damn good singers and damn good companies. But I just wanted to give so much to them to help them. One other thing, though, is that we need to stop thinking that the whole world situation is our fault. It ain't.

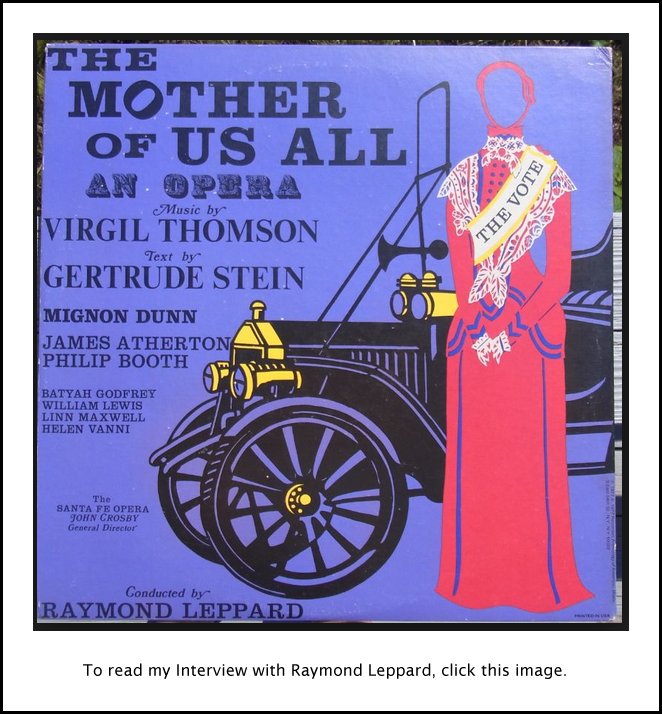

BD: It's good that you're so pro-American. Is there a Great American Opera?

MD: I don't know what it is. There certainly should be some. I certainly thinkSusannah by Carlisle Floyd is a great piece and I enjoyed it very much. I remember seeing it with Norman Treigle. Menotti'sSaint of Bleeker Street is a great piece, as is The Consul. [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right, see my interview with Virgil Thomson.]

BD: Why aren't more of these works done by major companies?

MD: Americans have been brainwashed into thinking that we're really not good enough, and that's silly. There are incredible amounts of talented singers and conductors and composers in the United States.

BD: So where is opera going today?

MD: It's getting more and more popular all the time, with the television and the fact that it's become more of a drama-art-form, too, along with the music. That is as it should be.

BD: Then the "Capriccio" question

— which is more important, the music or the drama?

MD: I don't know. It's extremely hard for me, for example, to sing lieder where I don't like the poetry. I can't just sing notes without words. I have to have a text that I can relate to in order to make it live. But that's just me. I don't know which is more important.

BD: So you can't be uninvolved?

MD: No. I wish I could sometimes, but I can't.

It's a great profession and I love it, and I feel very blessed that I have been able to do the things that I've wanted to do. I've sung almost everything I've wanted to sing. There are still things I want to do, and I feel very good vocally.

BD: Would you ever want to do any directing?

MD: I want to, I really do. I think I would be very good at it. I haven't done any yet because I haven't had time. I want to teach and do master-classes, and be involved with young singers because that's the continuance. But before I teach I want to learn more about teaching. I don't think that you just stop singing and teach. You need to know more about how to do the technical ends of things.

BD: Did these things come easily for you or did you have to work at them?

MD: Some things you work like hell, and other things came easy. Mostly you work like hell. Every role I do is worked note by note by note, then three notes together, then four notes together, then a line together, then a sentence together, then a page together.

BD: Thank you so much.

MD: Thank you, it's been lovely.

To read my Interview with Birgit Nilsson, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Leonie Rysanek, click HERE.

To read my Interview with James Levine, click HERE.

To read my Interviews with Sherrill Milnes, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Alfredo Kraus, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Julius Rudel, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Erich Liensdorf, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Nathaniel Merrill, cllick HERE.

To read my Interview with Jean Kraft, click HERE.

To read my Interview with David Stivender, click HERE.

© 1984 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in her apartment in Chicago on October 5, 1984. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1996. This transcription was made and much of it was published in Nit & Wit Magazine in May, 1986. It was completed and slightly re-edited, photos and links were added, and it was posted on this website at the end of 2015.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.