Frank Little Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

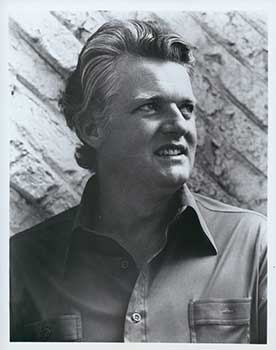

Tenor / Administrator Frank Little

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Frank Little, 69, Met Tenor and Educator, Dies

By Anne Midgette

· March 6, 2006 The New York Times

·

Frank Little, a tenor who sang at the Metropolitan Opera for five seasons but ultimately left the stage for a career as an arts administrator and educator, died on Feb. 22 at a palliative care center in Skokie, Ill. He was 69.

He died of complications of cardiac arrest, said his son Courtney Little.

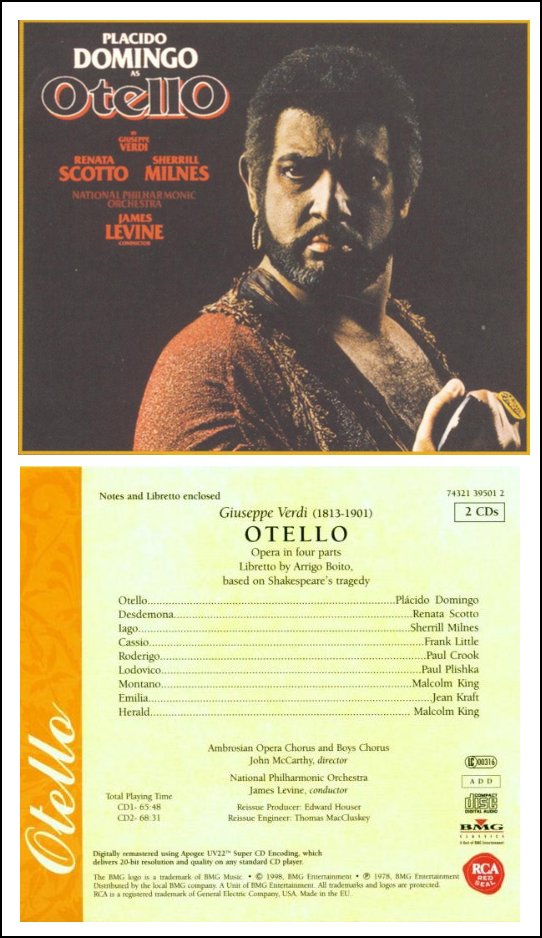

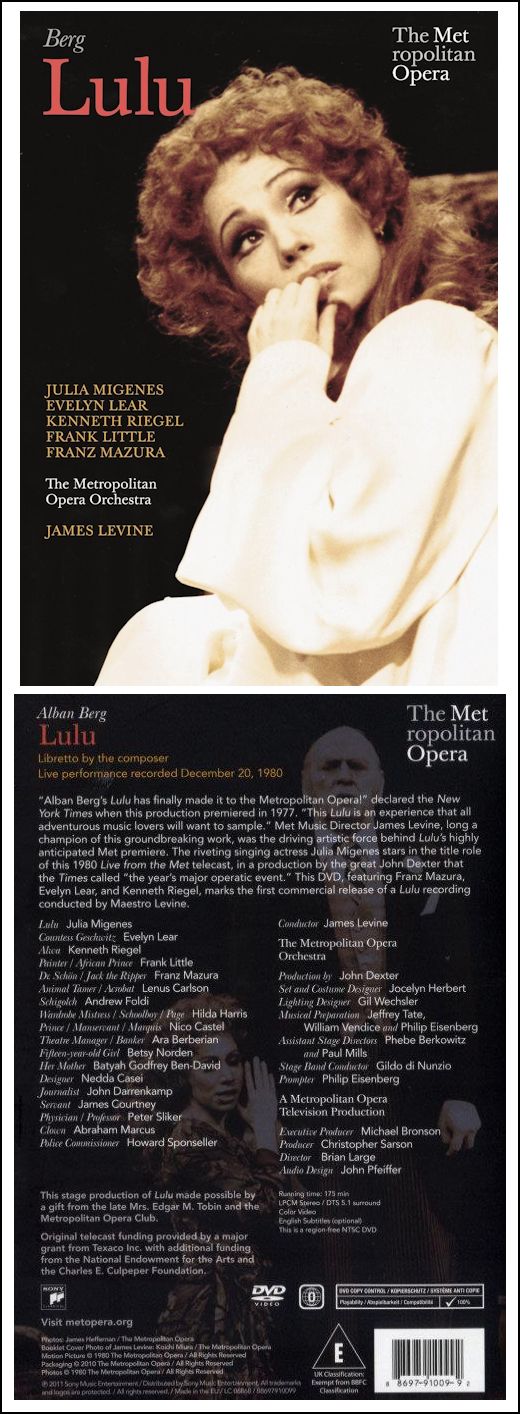

Mr. Little began singing at Chicago Lyric Opera in 1968, and made his debut at the Met as Narraboth in "Salome" in 1977. Other roles at the Met included parts in the world premiere of the three-act version of Berg's "Lulu" in 1977 and several turns as Cassio in Verdi's "Otello," which he also sang on the RCA recording with Plácido Domingo and Renata Scotto. At Chicago Lyric, he sang in the world premiere of Krystof Penderecki's "Paradise Lost." His appearances in Italy ranged from La Scala to a private performance for Pope John Paul II.

Mr. Little returned to teaching as early as 1970, and in 1981 decided to leave performing altogether. His performing schedule kept him on the road for as much as nine months a year, and he wanted to spend more time with his family.

After working as chairman of performance studies at DePaul University in Chicago and chairman of the music department at Furman University in Greenville, S.C., he became president of the Music Center of the North Shore in Chicago, later renamed the Music Institute of Chicago, a school for young, gifted musicians. He remained there for 17 years, until retiring in 2003.

Francis Easterly Little was born on March 22, 1936, in Greeneville, Tenn., in the Smoky Mountains, and began studying voice in high school. He worked his way through East Tennessee State University (with, among other things, stints in a vaudeville show), joined the Army and subsequently received a master's degree from the Cincinnati College Conservatory of Music (in 1960) and a doctorate in vocal performance from Northwestern (in 1971). Described by friends as a Southern gentleman, he remained true to his roots, with a passion for Civil War history and bluegrass music. Two of his sons, Courtney and Carter Little, are musicians in Nashville.

He met his wife, Carolyn, on a blind date in 1962; they were married the next year.

At the Music Institute of Chicago, Mr. Little tripled the enrollment, expanded the facilities and helped lead a number of students toward international success.

"I think he felt children's education in music was as, or more, important as education at the collegiate level," said his son Courtney.

Mr. Little also helped develop the school's Institute for Therapy Through the Arts, one of only a few such programs in the country.

In addition to his wife, of Winnetka, Ill., and his sons Courtney and Carter, he is survived by a daughter, Caroline Degenaars of Kenilworth, Ill.; another son, Kent Little of Santa Fe, N.M.; five grandchildren; and a sister, Winnie Pruett of Picayune, Miss.

* * * * *

Note: While preparing this interview for presentation on my website, I saw a discrepancy between the stated date of his Lyric debut in this obituary (as well as the one from the Chicago Tribune, which is reproduced at the bottom of this webpage), and the listing in the official annals of the company. I was fortunate to make contact with Little's daughter, Caroline Degenaars, and she told me that he was officially contracted with Lyric from 1970-81. However, while doing his doctoral work at Northwestern in the late 1960s, he did some work with Lyric. His full repertory with the company (and with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra) is shown in the chart below. BD

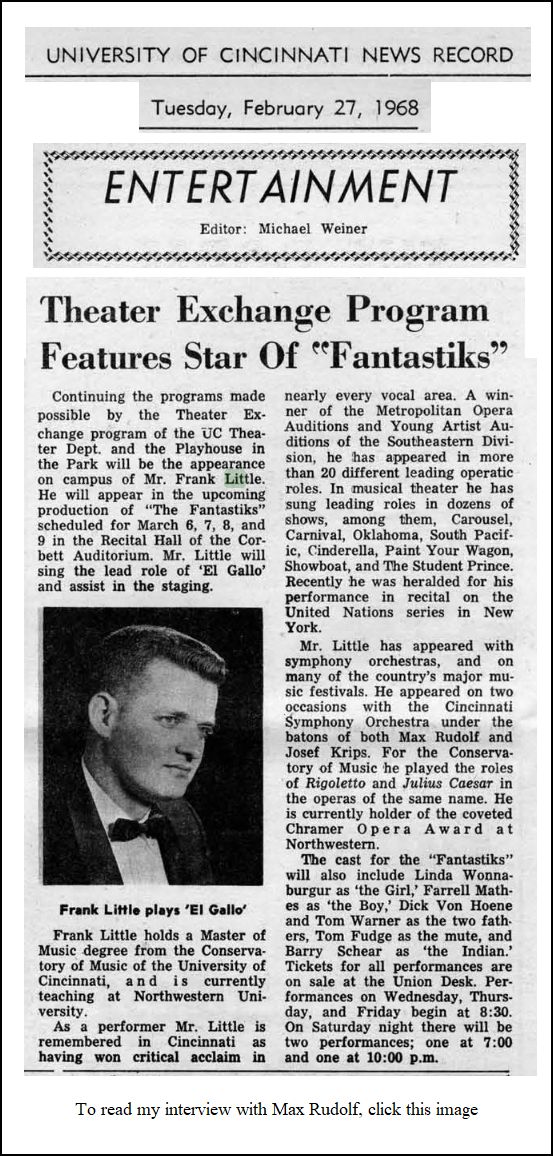

Having known the artistry of Frank Little for many years through his performances at Lyric Opera, it was my great pleasure to arrange for an interview with him at the end of July of 1982. We met in his office at DePaul, just as he was about to make a major change in his career . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: You are leaving your present post at DePaul?

Frank Little: Yes. For four years I’ve been the Chairman of the Performance Studies Department within the School of Music, and have been charged with the responsibility of organizing and guiding development of a performance program.

BD: How do you balance this with a busy concert and opera career?

Little: It’s very hard to do. You have to have an excessive amount of energy, and you have to be a bit hyper. There are times when I’m virtually unneeded here, but there are days and weeks at a stretch when my own actions have to come into play on an hourly basis.

BD: Does it ever work out that the times that you are not needed is when you have a concert contract to fulfill?

Little: Yes, it’s usually that way. There have been very few times where there’s been a conflict of any major proportion. Then, regrettably, it often means that I have to miss some major performances within the School of Music.

BD: So your concert career then comes first?

Little: DePaul is first, and has been first, but it has worked out quite equitably to a fifty-fifty balance, and both of us have been very happy. Living here was not really our choice. It was a circumstance of opportunity presenting itself, and a certain set of awareness about one’s chronological position.

Frank Little at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1970 - [Opening Night] Rosenkavalier (Animal Trainer) - with Minton, Ludwig, Berry, Brooks, Gutstein, Garaventa, Zilio, Andreolli, Voketaitis;

Dohnányi, Neugebauer, Schneider-Siemssen

Lucia di Lammermoor (Normanno) - with Deutekom, Tucker, Mittelmann, Washington; Votto, Frisell

1971 - Rheingold (Froh) - with Hofmann, Hoffman, Neidlinger, Holm, Nienstedt, Rundgren, Sotin, Boese; Leitner, Lehmann, Grübler

Salome(Narraboth) - with Silja, Nienstedt, Cervena,Ulfung, Johnson, Meredith, Drake; Dohnányi, Lehmann, Pizzi

1972 - [Opening Night] Due Foscari (Barbarigo) - with Cappuccilli, Ricciarelli, Tagliavini, Voketaitis; Bartoletti, DeLullo, Pizzi

Wozzeck (Drum Major) - with Evans, Silja, Meredith, Manno, Herrnkind; Bartoletti, Puecher, Damiani

1973 - Rosenkavalier (Major-Domo of the Marschallin) - with Berthold, Ludwig/Dernesch, Sotin,Blegen Gutstein, Merighi, Zilio, Andreolli, Voketaitis;

Leitner, Neugebauer, Schneider-Siemssen

1974 - Peter Grimes (Bob Boles) - with Vickers, Kubiak, Evans, Nolen, Chookasian; Bartoletti, Anderson, Toms

1975 - Elektra (Aegisth) - with Roberts/Schröder-Feinen, Boese/Dunn, Neblett,Stewart/Tyl; Klobučar/Bartoletti, Heinrich

Lucia di Lammermoor (Arturo) - with Sutherland, Pavarotti/Theyard, Saccomani, Ferrin; Bonynge, Copley, Bardon

1976 - Khovanshchina (Andrei Khovansky) - withGhiaurov, Cortez,Trussel, Mittelmann,Shade, Lagger; Bartoletti, Benois

Love for Three Oranges (Prince) - with Barlow, Dooley, Trussell, Titus, Gill, Tajo, Kuhlmann; Bartoletti, Chazalettes, Santicchi

1977 - Idomeneo (Arbace) - with Tappy, Ewing, Neblett, Eda-Pierre/Shade, Shirley; Pritchard, Ponnelle

Peter Grimes (Bob Boles) - with Vickers, Kubiak, Meredith/Evans, Nolen, Bainbridge; Bartoletti, Evans, Toms

Maria Callas Tribute (concert)- with (among others) Neblett, Vickers, Kuhlmann, Stilwell, Carol Fox, Gobbi; Bartoletti, Fournet

Meistersinger (Vogelgesang) - with Ridderbusch, Evans, Johns, Lorengar, Howell, Walker, Riegel, Dooley; Leitner, Merrill, O'Hearn,Tallchief

1978 - Salome (Narraboth) - with Bumbry, Bailey, Dunn, Ulfung, Kunde, O'Leary; Klobučar, Poettgen, Wieland Wagner

[World Premiere]Paradise Lost [Penderecki] (Michael) - with Stone, Shade, Van Ginkel, Ballam, Powers, Esswood; Bartoletti, Perry, Tallchief

1979 - Love for Three Oranges (Prince) - with Souliotis, Nolen, Trussell, Tajo, Kuhlmann, White, Sharon Graham; Prêtre, Chazalettes, Santicchi

1981 - Macbeth (Macduff) - with Cappuccilli, Barstow, Plishka, Kunde; Fischer, Merrill, Benois

Frank Little with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus

March, 1976 - Symphony #9 [Beethoven] - with Faye Robinson, Claudine Carlson, Raymond Michalski; Carlo Maria Giulini

April, 1976 - Passion [Alan Stout] - with Phyllis Bryn-Julson, John McCollum, Leslie Guinn, LeRoy Lehr, Monroe Olson; Margaret Hillis

[The premiere of Stout’s Passion, on which the composer worked for over twenty years, was a “monumental undertaking [and] provided the most difficult music the Chorus has undertaken since Fritz Reiner brought Margaret Hillis here in 1957 to found the now internationally known ensemble,” wrote Thomas Willis in the Chicago Tribune. “Stout fashions his church Latin text into curtains and tapestries of sound. Like a sonic aurora borealis, they expand and contract as needed, supplying intimate but still objective commentary on an emotional-laden event, creating towering climaxing as the peak points of the action, or providing canopies of tightly woven, often contrapuntal sheets of sound against which other portions of the action can take place.”] (Part of a tribute to Stout, from the CSO website.)

February/March, 1980 - Elijah [Mendelssohn] - with Phyllis Bryn-Julson, Linn Maxwell, Dale Duesing; Margaret Hillis

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

BD: What is your new position?

Little: I’m going to be Head of the Music Department at Furman University. It’s a very large department, the size of a music school. The terms school or department are interchangeable, as are the terms Dean and Director and Chairman. It has some two hundred majors, and a very active and aggressive qualitative undergraduate music program. If there is a distinction, it is in that there is no graduate program in music, but that quite frankly appeals to me.

BD: Are you turning out teachers of music, or performers of music?

Little: Basically performers. There is a strong program in music education, but Furman’s role has been one of being a feeder school to the really fine graduate schools in the country, such as Eastman and Juilliard and Northwestern. It seems like there’s an

‘underground railroad’ between Furman University and Northwestern University. Many of their fine graduates come to Northwestern.

BD: That’s where I did my graduate degree.

Little: Mine, too! My doctorate is from there, and I’m very proud of that, as I am sure you are, too.

BD: Extremely.

Little: Also, a number of Northwesterners are on the faculty at Furman.

BD: So the

‘railroad’ goes back there!

Little: That’s right, and there will be more in the Fall. Furman’s in Greenville, South Carolina, and has a beautiful campus with wonderful physical facilities.

BD: What did they offer you to make you leave Chicago?

Little: Let me take a step back from that. Long before I ever became a Singer with a capital S, I had supposed that my career would be in education. I had hoped that it would be in education administration. My family is filled with teachers, and I had carved out, through my earlier experiences in education, a kind of academic Nirvana, or Valhalla, that someday I would like to operate in. It took the form of a small distinguished academically superior liberal arts college or university, with a likewise strong commitment to the Arts. If you look across this country, there’s a very short list of those kinds of schools, such as Oberlin, Lawrence University, perhaps Amherst, Stetson University in Florida, St. Olaf, these kinds of schools. Furman is one of those schools, and has become increasingly so in the last seven or eight years.

Little: Let me take a step back from that. Long before I ever became a Singer with a capital S, I had supposed that my career would be in education. I had hoped that it would be in education administration. My family is filled with teachers, and I had carved out, through my earlier experiences in education, a kind of academic Nirvana, or Valhalla, that someday I would like to operate in. It took the form of a small distinguished academically superior liberal arts college or university, with a likewise strong commitment to the Arts. If you look across this country, there’s a very short list of those kinds of schools, such as Oberlin, Lawrence University, perhaps Amherst, Stetson University in Florida, St. Olaf, these kinds of schools. Furman is one of those schools, and has become increasingly so in the last seven or eight years.

BD: Is this just in music, or in all the arts?

Little: Mainly in music. It has, without question, the strongest choral program in the south. There are two hundred majors, there’s a seventy-piece symphony orchestra with no ringers

— that is no faculty, nor community ‘golden-oldies’ sitting in. There is a one-hundred-fifty-piece marching band, a concert band, a second concert band, a wind ensemble, and a couple of jazz ensembles. There is also a brand-new music facility, a major endowment, and music scholarship.

BD: What is the total enrollment? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Renata Scotto,Sherrill Milnes, Jean Kraft, and James Levine.]

Little: Twenty-five-hundred is the total enrollment of the university, and about nine percent of those are involved in music. So, that’s a strong commitment.

BD: You’ll be running this whole school?

Little: Yes.

BD: As a singer, are you going to be as much help to the bassoon player as to a tenor?

Little: That’s an interesting question, and I have to be very careful about that, but not from the point of view of what you think. Looking back on my time at DePaul, I could have been more supportive of the vocal areas. One would think that one would have a natural bias there, but perhaps I had a natural tendency to lean the other way.

BD: Maybe this was because you had to work a little bit harder on the woodwinds?

Little: Yes, and not only that, but I suppose I felt that it would be expected of me to come in and favor the development of a vocal program at the expense of the other programs. As it turns out, here at DePaul we have developed very strong strings, winds, percussion, and brass programs, and it is now the turn of the vocal program to have a shot in the arm.

BD: Who is going to replace you?

Little: The person who’ll replace me is the current co-ordinator of the woodwind program, so maybe she’ll bend over backwards to emphasize vocal, just as I, perhaps, bent too far backwards in the direction of instrumental.

BD: When you get to your new position, you will maybe have arrived at a balance?

Little: Yes, I think so. From the perspective of being, for want of a better word, what I call Number One

— the person who runs the show, or who has the responsibility for the whole show — one has more of the wherewithal, including financial, to assure that each gets its day in the sun. Whereas, when one sits in a subordinate position — a Number Two position, such as I am here, which is my position in relationship to the Dean — one can have a great deal of input, but the ultimate decision, the ultimate bottom line rests with the Number One.

BD: Being Number One, will this cut down on your performing at all?

Little: I think not. As a matter of fact, we were approaching a phenomenon at DePaul. This university has been very good to me in terms of encouraging my performance, and insisting upon it to the extent that I wanted to do it. However, this School of Music has grown and become more complex because there are some seventy, or seventy-five faculty members, sixty of whom are in this one department.

BD: In the performance department?

Little: Yes. So as this program has become more complex just by sheer weight of numbers, there’s a greater demand on your time, and upon the decision-making process. There are a lot of just the routine nit-picky kinds of things that have to get done nowadays, and when you multiply that by the number of bodies that are present, you suddenly find lots of days which are just wall-to-wall problem-solving and people-solving. Therefore, I was beginning to feel that the responsibilities of this position, as it has grown

— and it has grown vastly in these four years — were beginning to dictate that I look long and hard at accepting certain kinds of engagements, particularly those that took me away for weeks and months at a time. In the case of Furman, I know that they are very interested in having me use the stages that I’m on to further the greater good of Furman University, which means it comes home to them in some ways.

BD: When you’re doing a major role some place, and your bio says you’re the Head of the School of Music at Furman University, that’s a good plug for them?

Little: Yes, it is. It’s also good for them in the region, and in the South East, for the local publicity to say that I will be appearing with the Cleveland Orchestra in Carnegie Hall for example.

BD: If it ever comes down to a question of accepting an engagement in one or another city, or being where you’re supposed to be at the school, what kind of decision do you make?

Little: It would depend on what the engagement is. I have made a pact with myself, and have explained this rather thoroughly to whomever I have been affiliated with as an academic, that if I have an opportunity to sing with any of the four or five major opera companies in this country

— and I have sung with all of them — when and if they call back, if the terms are right and the conditions are right, then I will go and sing there, because that is what I do. That is what I am. I’m a singer.

BD: This means a major role in a major house?

Little: Absolutely, or a major concert engagement with a major orchestra. I would go, no questions. I don’t care if I would miss the annual Christmas Gala, or the benefit for the philanthropists’ dinner, or whatever. Under those circumstances, I go. I also weigh other things. I don’t mean for that to sound condescending. It’s purely and simply that we all go through a process of placing a certain value on our time.

BD: You’re juggling two very important positions, and it’s interesting that they wind up meshing as well as they do.

Little: Yes, and there’s a third aspect to it which I created. It’s a many-headed monster, but it’s a very nice monster. I developed as a singer, I developed as an academic, and earned a terminal degree.

BD: [Laughs] Sounds like a disease!

Little: [Also laughs] Yes, and it felt like that at the time! But during the process of becoming an administrator, I’ve increasingly involved myself in development, meaning fund-raising and public relations. I don’t know whether that’s an extension of my personality, or a lack of fear as a result of being on stage a lot, but I find that turf

— the idea of raising money — very interesting and very appealing. I’m one of those few people who love to go out and ask people the questions,“Will you support this? Will you give us your dollars?” Most people don’t like doing that.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] Maybe you should ask someone like Carlisle Floyd to write an opera called The Fundraiser. [Both laugh]

Little: I’m afraid there would be a lot of anti-heroes in it! [More laughter] Anyway, it’s a combination that seems to be fairly appealing in terms of arts administration.

BD: How are the arts doing these days in terms of funding on the educational level? Are they healthy?

Little: That’s a very general question, but I would say yes, they’re healthy, but they’re impaired. They are healthy because of the general cultural explosion that’s gone on in the last two decades in this country, and they are likely to survive... even though that is really pious of me. [Laughs] They’re likely to remain in a reasonably good position because very few of the dollars that are committed to them are Federal, or are government associated. I believe very, very strongly that funding for the arts and education, and, for that matter, any kind of philanthropy, is going to have to find more and more basis in the private sector. I have believed that forever, even when I argued that ten or twelve years ago with my colleagues at the Lyric Opera, and the Chicago Symphony, and so forth. They thought I was a madman, and they all advocated government funding for the arts. Not me. I never did, and I never will. What the government has done only represents about one or two per cent of the total funding, anyway. If it were taken away, certain kinds of projects would be forced to find their funding in the private sector.

BD: And a few of them would fold?

Little: A few would fold, but there are two things, and the perfect example of that is what has happened at the Lyric. I’m talking about the Federal Government. I’m not talking about the local Municipal Government, for that matter, and the State is not a factor, anyway. But I think the City of Chicago should do something for the Lyric Opera of Chicago and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, because the citizens of this particular city, who spend their dollars here, and who contribute to the welfare of this particular metropolis, deserve those institutions. But I don’t think that the Federal Government has any business being in that arena, or that the Lyric Opera has any right to step up and ask the Federal Government to assist with its deficit. That’s just a personal feeling. I was talking the other day with a very distinguished gentleman in this regard. He is one of the President’s Ambassadors for the Arts. They comprise a Council to study this particular problem. I think that re-arranging tax structures has a very negative influence on the philanthropic dollar, because if a person only has to pay tax on thirty per cent of his earnings over a certain amount, as opposed to fifty per cent, then the twenty per cent factor of the shelter is taken away, and therefore, philanthropic institutions will suffer.

BD: The straight percentage income tax is not something you favor?

Little: No, I really don’t in any shape or form, but also I’m not heavily in favor of tax cuts for the wealthy or the upper middle class. I believe that there should be tax incentive for philanthropy.

BD: This is what the charitable donations do.

Little: That’s for any kind of philanthropy

— for medical, religious, artistic, scientific, whatever. It’s a much more viable resource then than trying to create philanthropy through a governmental bureaucracy.

BD: If they just set up a whole new bureau, lots of money would get lost in the shuffle?

Little: All of it, virtually.

BD: Getting back to your position here and your new position, do you feel that because you are a performer, that you can give students a different kind of outlook on performing, than someone who spent most or all of their time in academia?

Little: Oh absolutely. It works two ways. One has to be careful about one’s objectivity, and one has to be careful about relating the young developing performer to the finished product. Those of us who’ve spent a lot of time in the company of the great, great singers, or the great conductors, or the great directors, sometimes have expectations which are a little bit too high for the younger singer. Personally, I have been guilty from time to time of being not upbeat and positive enough with young singers.

BD: You are seeing too much of their limitations?

Little: Yes, and not looking at the different perspective of the person who has ten or fifteen years to go, and the perspective of what is the stage of their art. This is not an uncommon phenomenon, and I do think that it’s better for me, as a performer, to have those kinds of expectations than it is for certain studio-types, pure academics who have never known the rigors, or have never been in the arena, as it were.

BD: I would assume that just about anyone who is heading up a music school, or involved in it, would have, at some time, gone through the rigors of performance

— even if it was a recital or two twenty years ago, as opposed to a string of performances every six weeks.

Little: Absolutely. However, I don’t think one has to have been a great performer, or a good performer, or an excellent performer to be an excellent teacher. The two don’t necessarily follow, but I do believe that if the person is capable of relating, or keeping it in perspective, that the pure amount of experience and information that is there, as a result of having been through the events, is a tremendous boon.

BD: Have you worked with singers that you know are going to be able to make it into the big career? Not necessarily the top, top career, but certainly the good strong career?

Little: We’ve had a couple of students who have been through here over the years, including one girl in particular, who is going to have a major career. She didn’t stay unfortunately. She moved along. She had an altercation with her teacher, but it’s going to be a major career, there’s no question. It’s one of things that you know. It’s like the first time I ever heard Ashley Putnam. I was privy to that. I was in the Canary Islands singing Maria Stuarda with Joan Sutherland, and Ashley was in the University of Michigan Chorus. She kept badgering Richard Bonynge to audition. He wouldn’t give her one, and finally he succumbed and heard her, and within no time she was with Colbert Artists Management. I’m not saying that it happened directly that way, but I know that Bonynge was very impressed with her. She sure got an awful lot of hullabaloo in the beginning. She’s a great artist and a great singer.

BD: Is she intelligent enough to say no at the right time?

Little: Hopefully.

BD: This is a question that I ask of most singers. How difficult is it to say no?

Little: It’s very difficult. I’ve made some mistakes along the way, in that I’ve gotten greedy a couple of times.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] That Siegfried you sang was not the best for you! [Both laugh]

Little: I sang Pollione (in Norma) a few years ago opposite Beverly Sills. I would like to think of myself as being sandwiched between Tatiana Troyanos and Beverly Sills. I went into the first performance and suffered an inguinal hernia on the right side, and got that trussed up. Then, in the second performance I blew one on the other side. I came directly back to Chicago almost on a hospital stretcher. I never went home, but went straight into the hospital. We were standing in the immolation at the end of the opera, and I’m just hurting badly. We were clutching each other, and she said to me, “Frank, do you realize you have just sung my last Norma with me?” I replied, “Beverly, do you realize you’ve sung my only Pollione with me?” [Both laugh] But you do those things, and I have three or four of those scalps that I’d like to take off of my belt.

BD: Are there roles that you’ve really wanted to sing, and know you should sing, but you have never had the opportunity?

Little: Yes. There are a couple of roles that I really would like to sing. I’ve always wanted to sing Erik in The Flying Dutchman. I was offered it several years ago, but had a conflict and couldn’t do it, and I’ve never been offered it since. I have had real big successes with these kinds of quarter-horse roles, as opposed to thorough-bred roles.

BD: Like the Prince in The Love for Three Oranges?

Little: Yes, exactly.

Little: Yes, exactly.

BD: What about Tom Rakewell (in Stravinsky’s_The Rakes Progress_)?

Little: Tom Rakewell is a real thorough-bred. That’s one of these roles that starts on Page 1, and ends on Page 380, and they’re very few pages in between that he doesn’t sing. But I’m talking about roles like Narraboth, or Bacchus. There are hundreds of them.

BD: Those are roles that require the real first-rate sound and first-rate weight, but only are on stage for a short time?

Little: Right, they take real heavy and tense singing over short periods of time.

BD: Aegisthus?

Little: Aegisthus, I’ve sung a lot.

BD: Do you enjoy these kinds of roles?

Little: I enjoy them. Also, the role of the Painter that I sang in Lulu at the Met last year. [_DVD of that telecast is shown at right. See my interviews with Evelyn Lear,Lenus Carlson,Andrew Foldi, and Jeffrey Tate._]

BD: What about the composer Alwa (another role in Lulu)?

Little: That’s a very intense, extremely difficult role, but it only exists in maybe thirty or forty minutes of the opera. Somehow or other, I have had better luck with those kinds of roles, and with roles that have more of an expressionistic nature.

BD: Pinkerton (in Madama Butterfly) is that kind of a role. It’s all in the first act, a little bit at the very end.

Little: Yes, and I have sung Cavaradossi, and Riccardo in Un Ballo in Maschera. I also did Traviata many times, but somehow these other kinds of roles appeal to me.

BD: Do they appeal to you more because you know you do them well, so you feel more successful in them?

Little: Could be! It’s also a phenomenon of never being able to see myself as the romantic, for example the Duke in Rigoletto. I just could never see myself as that kind of character. Macduff is one of those special roles, and I did it here last year. It is hard, very exposed singing, but for short bursts of time. I’m absolutely in awe of the person who can go out and deliver Tristan, or Otello, or Tannhäuser. It could be that I’ve never been quite willing to go out and gamble my very life and existence against my survival in a role. Part of that, also, could have to do with the nature of the dual career. That used to trouble me a little bit, but as it turns out, it’s been more of an asset than a handicap.

BD: If you knew that by turning this role down you would have two months of sitting around doing nothing, might that influence you to a different decision?

Little: Sure. Michael in_Paradise Lost_ was the same kind of role. It seems that Bruno Bartoletti, or James Levine, or whoever the people are who are casting, have me in mind.

BD: And you’re happy with that?

Little: Yes, I really am. It would be perhaps impossible, if one was a primo tenor, to do anything like that, but I have rationalized, or have negotiated myself to a position where I will do the second roles. I won’t do comprimario anymore. There’s nothing wrong with it, but that also means one gets on the staff at an opera house and is available every night. I think some of the great singers in this country are comprimario singers, and they are magnificent. People like Charles Anthony, who is wonderful, and who is capable of singing Pinkerton on any night, but he has allowed himself to be relegated to the comprimario niche.

BD: Of course he’s working steadily that way.

Little: Absolutely, and believe me, among the most valuable people in the house are these kinds of singers.

BD: Do you rate Florindo Andreolli in that class?

Little: From my point of view, he is the greatest comprimario in the world!

BD: [With some concern] More than Piero De Palma?

Little: Well, when one says the

‘greatest this’, or the ‘greatest that’, I suppose that’s always wrong. Andreolli’s one of the most interesting people, and one of the funniest people I’ve ever known. He is an absolutely delightful character. Remember, my remarks about comprimario weren’t said with any kind of condescension.

BD: No, but it’s not just for you.

Little: Right. That kind of singing is more confining than singing primo roles, because you’re expected to sing every night, or every other night.

BD: [With a wink] So you give up singing those for the same reasons you gave up singing Tristan and Siegfried?

Little: That’s right... if I could have ever sung them! [Both laugh]

BD: But you know you shouldn’t do those huge parts. You also know you shouldn’t do _comprimario,_and it’s two different things.

Little: My career has been built in those middle kind of roles, really

‘quarter horse’ roles. [_A Quarter Horse is one that excels in sprinting short distances._] I also do a great deal of concert work with orchestras, oratorio and so on.

BD: Which do you prefer, or is that a terrible question?

Little: Selfishly, with the exception of the three or four major opera houses, I prefer the concert work. It’s very selfish because one goes out, and usually the orchestras do three or four performances. The rehearsal period is also usually a couple of days. An opera that’s any good requires anywhere from ten days to two weeks of rehearsal for a performance. You can get three to five performances out of those two weeks, but there’s not much successful opera being produced on three days of rehearsal.

BD: Is it a let-down after the first performance when you have a couple of days before the next performance? Do you do anything to psyche yourself up, or do you make a few administrative decisions and then go back?

Little: I’ve done a lot of that, but it depends on how you performed. If you’ve performed well, and you have had a good experience, and you know what you’ve delivered has been somewhere close to your best standard for yourself, then the days in between don’t make any difference. But if you have sung poorly, or if you’ve not met your standard, or something has gone wrong in terms of the orchestra or the conductor, or your relationship with a colleague is not exactly what it should be, then there’s a let-down.

BD: Do the newspaper reviews bother you?

Little: Not very much. I would say that eighty per cent of the reviews I have received as a singer have been very much in the ball park of the quality of performance that I have in my own mind. Fifteen per cent have been very gratuitous, and maybe five per cent of the time I have felt that I have been ripped off by a critic. I don’t like to get even qualified reviews in my home town, because I spend a lot of my time among the lay public. A lot of my relationships have nothing to do with music, and when the layman reads a qualified review, he thinks it’s a bad review. So you spend a lot of time trying to explain to the person what was meant by a particular catch phrase. Recently, one of the Chicago critics wrote that I had sung a

‘routine performance’ of that particular role. It was absolutely right. There was very little that was distinguished about the particular performance that he heard, and I had struggled a little bit, and the word ‘routine’ might have been slightly gratuitous. He could have said something a little more explanatory, but all of my lay friends in the suburbs said they had seen this bad review. In my musical world, I don’t worry about my musical peers, or my colleagues, or the people at the opera house, but this was in the Chicago Tribune, and I couldn’t give all my lay friends the review from Opera Canada, which said I was brilliant in the role! [Both laugh] So, to go back to your question, yes I guess we do get upset about reviews. I have had some reviews that were scathing. One critic in Wilmington, Delaware, called me an operatic creep. [More laughter]

BD: If it’s in Wilmington, Delaware, is that a major critic, or just someone who is on their staff?

Little: I don’t whether he is major or not. He’s not in my eyes, but what he was referring to was that in this role I was creeping around the stage. Jon Vickers, for example, has never done anything but creep in his entire career, because that’s the way Jon moves. It’s like he is under water! That’s his style. He’s a marvelous actor, but this is what the reviewer was talking about, that I was very slow moving. My motions were all clearly defined, and he saw that as creeping. But instead of saying that I had a tendency to creep around the stage, he called me an operatic creep, which is a completely different thing! I had a hard time explaining that to my wife’s parents’ friends who live in Wilmington. But by and large, I have no great complaint with reviews. I don’t feel any of the anger that certain artists do about critics and the critical process.

BD: Do they serve a purpose?

Little: Darn right, they serve a purpose. Artists, and arts administrators need a monitor.

BD: Do you see yourself as ever being an administrator of an opera house?

Little: I’d love to run an opera house, but I don’t think I ever will because I’m not dedicated enough. I look at somebody like Ardis Krainik as the paragon of what an operatic administrator should be. We are talking about a person who gives the company twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, with virtually no vacation.

BD: Of course, a lot of that is fundraising, and you said you liked that.

Little: Yes, although selfishly I have a wife and four children, and at this stage in my life I don’t think I would be successful. If I accepted such a position, I might be successful, but at an enormous personal cost. Most of the really first-rate administrators of today are single, or have been single. It’s also awfully hard to be a great artist and divide and share the muse with another person; to literally share your life and problems with another person while being a primo artist. A few of the great singers of the world have mates who love them, and care for them deeply. They have a special kind of relationship which accommodates the artist. There are two kinds of operatic mates. There are those who stay completely out of it, and who will come to an opening, but they stay home and have a second career. Or they tend the home fires, or have a volunteer career. Then there are those stage mates who are there in the dressing room, who pick up every sock, who keep the hairdressers running around, and keep the costumers coming back to be sure that the dress is fitting the mate properly, or that the tights are not too tight.

BD: I assume they can sometimes get under foot back stage?

Little: Yes, they can. There are wonderful stories about some of those. There was the wife of a great, great tenor

— who will remain nameless — who was so involved in what he did that she’d stand in the wings, and if he was not singing well, she would just shake her head at him to indicate that it was not going well... to the point that he would become so paranoid that he would lose the performance. [Both laugh] BD: How do you feel about opera in translation? [_Remember, this interview was held in 1982, just before the introduction of Supertitles in the theater._]

BD: How do you feel about opera in translation? [_Remember, this interview was held in 1982, just before the introduction of Supertitles in the theater._]

Little: In English, for example, or a language other than the one it was composed in? [Sighs] There again, I would say that sometimes I was a little too heavy-handed, and had, perhaps, too great expectations based on my own experience. I prefer opera in the original language. I know all the arguments for translation, but I have always felt that opera is an elitist form. It is not a form that was meant to be necessarily accessible to every living breathing human being, or if it was, we would be any better for it. It began as a Court form. It was not until recent years that opera was supported and subsidized by legislators, congresses, and federal entities. It was subsidized in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries buy private families

— princes, dukes, kings — and if you want to say that the king is the government, that’s another matter. When talking about international opera, not about our American opera, part of the mystique of opera is that it exists in another language. So, access to it, and the understanding of it, must be through some small breaking down of that barrier, and if that barrier is erased, then I don’t think the opera-goer has done his homework. I don’t think he should be privy to the form without doing that particular little bit of homework. That may be interpreted as a very chauvinistic remark, but is that a rare opinion from your point of view?

BD: It’s a little different, but it’s the idea that one needs a bit of understanding before you come to a performance. In the same manner, you wouldn’t enjoy a baseball game if you didn’t know the difference between a foul ball and a double-play.

Little: That’s exactly right. So why go? Believe me, we have an awful lot of people out there who parade as aficionados of opera who don’t know what ‘_Dio Mio_’ means. I’m not saying that the operatic public must go out and translate a libretto. I don’t mean that for a minute. That would be a chauvinistic expectation, but I do think that any opera-goer should have a pretty strong understanding of what happens in the sequence of events from curtain-up to curtain-down.

BD: More than just reading the program while waiting for the performance to begin?

Little: Unlike most other theatrical experiences, with the repetition of attendance upon a given opera, and with the recognized differences of each performance of opera because of the different casts, it’s not like refusing to see The Sound of Music again because you’ve seen Julie Andrews in it. I would like very much to see seven different tenors interpret Werther, because it changes the event. The opera-goer then terraces, or layers his knowledge of that work with each subsequent attendance, and if at some point he wants to know exactly what Charlotte is saying in the Letter Scene, then fine. I don’t think it would be wrong for me to insist that an opera-goer know that, but I do think that when the opera-goer, the fan, goes to the event, he should know what’s happening in the Letter Scene. Of course, the best argument against opera-in-English is that nobody can understand the English language.

BD: When you work with singers, do you guide them in their diction in English, or Italian, or German?

Little: Of course, of course! But for that matter, in the Italian opera house, or in the German opera house, much of what passes as German, or German singing, goes right by the ears of the Germans, too. The best singers of German in the world are the Americans.

BD: Because they work at it?

Little: Yes. However, the best singers of English are not the Italians. There’s a not a quid pro quo there.

BD: Then who are the best singers of English?

Little: The English, or those from the Commonwealth. Vickers is just a tremendous exponent of the English language. I happen to sing English well, and have always gotten very strong critical praise.

BD: Were you happy singing The Love for Three Oranges in English?

Little: Yes, I was happy with that. Those kinds of Expressionistic works are fine, as are certain kinds of comedies, but I just don’t like to go and hear The Magic Flute in English, and I don’t feel anybody else should, either.

BD: Or La Traviata?

Little: Or La Traviata, or La Bohème. Everybody is entitled to his opinion, so what I have to say about that is a personal feeling. I learned to sing English because I came from a mountain territory of East Tennessee. I grew up sounding like a male Loretta Lynn, or Merle Haggard.

BD: Do you enjoy Country music?

Little: I love Country music, but I was forced at an early age to learn to sing the King’s English by singing many of the old chestnut Parlor Songs that were so much a part of the

’20s and ’30s in this country.

BD: Are we losing that kind of thing now that people don’t sit at home and play the piano at night? They watch television, or perhaps even listen to the radio?

Little: We’re losing this tradition because there is too much pre-occupation with artsy material, particularly in the English Song literature as Eternal Art. The best songs to sing are the old melodic ones, pieces of Dudley Buck and Mrs. HHA Beach, and The Road to Mandalay by Rudyard Kipling as set to music by Oley Speaks. These old late-Nineteenth and early-Twentieth Century war horses have already within them their melodic line, and in their particular kind of phrase structures there is a kind of drama. So, all that the singer has to do is go and articulate the text in such a way that it can be understood. There’s an awful lot of singing to be learned there, as opposed to going out and trying to conquer Charles Ives or some of the more difficult things of Rorem.

BD: Where do the Copland Old American Songs fit into that?

Little: Those are the kinds of songs I am talking about, yes. Barber falls into that category. I’m talking about songs that purists and esoterics would not consider to be Art Songs because they’re more popular. For example, operetta! Thank goodness for the Light Opera Works.

Founded in 1980, Light Opera Works (later called Music Theater Works) is a resident professional not-for-profit musical theatre company in Evanston, Illinois.

The company has presented over 75 productions of operetta and musical theatre at Northwestern University's 1,000-seat Cahn Auditorium. Since 1998, in addition to its three annual productions in this theatre, Music Theater Works also produces a fourth, more intimate show, in the 450 seat Nichols Concert Hall. The company performs all of its productions in English with orchestra.

Philip Kraus was the first Artistic Director of the company, serving from 1981 through 1999. The first production of the company occurred in 1981 with a staging of Gilbert and Sullivan's H.M.S. Pinafore. Under Kraus' leadership, the company's main emphasis in programming centered on American, French and Viennese operetta, and in its early years, the company staged all twelve of the full-length extant Gilbert and Sullivan Savoy operas.

I think that’s a wonderful enterprise. You can learn to sing English far more readily doing Victor Herbert than you can trying a translation of an Italian opera.

BD: Is there a place for that kind of work at Lyric Opera?

BD: Is there a place for that kind of work at Lyric Opera?

Little: No. They have their Spring Season in which they’re doing some lighter things, but I’m not talking about the operatic experience. I’m talking just about the learning to sing. If you talk to singers in my particular vintage

— in their middle 40s — an awful lot of them learned to sing on those old chestnuts. Now it is a pity that something is missing, and that is they don’t have an opportunity to sing. Gosh, when I grew up, I used to go around. I was under ‘management’ when I was about eighteen, but it was so silly. The manager happened to be a fellow who worked in a factory over in Kingsport, Tennessee, and he would put five acts in the back of a stage wagon. We had a girl that whistled, and a fellow by the name of Pistol Pete who was a one-man band. He had a bass drum strapped on his back, and cymbals between his knees, and a bunch of pots running around his waist, and he could just do all kinds of things. I went along and sang show tunes and these chestnuts we were talking about, for ten bucks a night. We would travel half-way across the Blue Ridge Mountains, or the Cumberland Mountains from Tennessee to Kentucky, and go to some Lion’s Club Lady’s Night in some coal mining town, and then spend half the night coming back across the mountains. But you felt you were in show business. It was wonderful, and I got virtually nothing for it. [Both laugh] For two years I sang on a Gospel television show, singing religious songs while these Gospel quartets paraded through. I got no money for it, but the guy who sponsored the show was a used car dealer, so he gave me an old junker of a car to drive around all the time! [More laughter] But I got to sing, and I was very seldom in auditions. The ‘audition’ was something that was to come later. Now, the young singer comes to college, and the first thing he’s confronted with is six weeks of work, and immediately he’s got to go out to compete on some national singing teacher’s audition, and be evaluated against his peers.

BD: Before he’s had any experience???

Little: Before he’s got anything going for him, to just see where he is. Sometimes these experiences are just absolutely shattering to these young singers. I sang for four years before I ever saw or heard of an

‘audition’. I finally went through an evaluation in my senior year in college, and by that time, I’d sung maybe four or five hundred events. So there was no pressure. You always sang well because it’s the only way you knew how to sing, and nobody was there adjudicating it. But it’s changed now. I don’t know if it’s the advent of communications — television, radio, the record industry — but freshman singers come here and they’re just frantic to get on with their careers. If they’re not identified already as having potential by the time they’re sophomores, then paranoia sets in.

BD: Is there a place today that they could go out every three or four nights and sing even if they wanted to?

Little: I don’t know. Churches would have Wednesday night dinners, and at those dinners you would get up after the meal and sing a number or two. Also, there were all sorts of club meetings.

BD: In your role here at DePaul, do you encourage them to go out and become affiliated with a couple of churches to sing at these Wednesday night dinners, if there are any?

Little: We tried to do some of that, but we have not been successful. There are four or five places in this neighborhood, right here within four hundred yards of DePaul in any given direction, that could do it. I’m not talking about a little saloon, or something like that. I’m talking about a restaurant with larger rooms. If the university would be involved in organizing it, we could provide them with something special. Every night of the week, we could send a pianist and a singer who’d come and perform fifteen or twenty minutes for your clients. Then, they could give those kids dinner.

A dinner like that would be about fifteen dollars, so each would have a nice dinner and get a chance to stand up and try out their repertoire before a non-critical public. It would be a good idea to identify those places. For example, Monastero’s Ristorante on the North side [_which closed in 2017 after fifty-five years_] does a wonderful job with this, although the atmosphere is not really authentic because you have to sing with an accordion, and you have to stand up in the middle of a room. I’m grateful for what Monastero’s has done, but that’s not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about a situation where there’s a piano and an area for the person to stand and face his audience to perform.

BD: Where’s opera going today?

Little: That’s a serious question! [Thinks a moment] A lot of it depends on the economy. If investors, philanthropists feel that they can get or are getting a lot of bang for the buck; that is if opera houses and the smaller companies, and for that matter symphony orchestras, are administered well; if the pencil is very sharp, and if the person does the kind of work that Ardis Krainik has done at the Lyric Opera – she really did work a miracle two years, there’s no question about it. If the impresarios do that kind of job, and keep the fingers that want to get into the pie as clean as possible, the future is very bright. I think that we will continue that the operatic revolution still has a way to go. If on the other hand a company, like the New York City Opera, which is so visible, does not solve its problems, and if it is allowed to collapse or die, something like that could be a very distasteful event for, let’s say, some entrepreneur who wants to start an opera company.

Since its founding in 1943 by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia as “The People’s Opera”, New York City Opera (NYCO) has been a critical part of the city’s cultural life. During its history, the company launched the careers of dozens of major artists, and presented engaging productions of both mainstream and unusual operas alongside commissions and regional premieres. The result was a uniquely American opera company of international stature.

Laszlo Halasz was the company's first director, serving in that position from 1943 until 1951. Given the company's goal of making opera accessible to the masses, Halasz believed that tickets should be inexpensive and that productions should be staged convincingly with singers who were both physically and vocally suited to their roles. To this end, ticket prices during the company's first season were priced at just 75 cents to 2(2 (2(29 in current dollar terms), and the company operated on a budget of 30,463(30,463 (30,463(4,400,000 in current dollar terms) during its first season. At such prices the company was unable to afford the star billing enjoyed by the Metropolitan Opera. Halasz, however, was able to turn this fact into a virtue by making the company an important platform for young singers, particularly American opera singers

For more than seven decades, New York City Opera has maintained a distinct identity, adhering to its unique mission: affordable ticket prices, a devotion to American works, English-language performances, the promotion of up-and-coming American singers, and seasons of accessible, vibrant and compelling productions intended to introduce new audiences to the art form. Stars who launched their careers at New York City Opera include Plácido Domingo, Catherine Malfitano, Sherrill Milnes, Samuel Ramey, Beverly Sills, Tatiana Troyanos, Carol Vaness, Jerry Hadley, Gianna Rolandi, and Shirley Verrett, among dozens of other great artists.

New York City Opera has a long history of inclusion and diversity. It was the first major opera company to feature African-American singers in leading roles (Todd Duncan as Tonio in Pagliacci, 1945; Camilla Williams in the title role in Madama Butterfly, 1946); the first to produce a new work by an African-American composer (William Grant Still,Troubled Island, 1949); and the first to have an African-American conductor lead its orchestra (Everett Lee, 1955).

The company filed for bankruptcy in 2013, and then a revitalized City Opera re-opened in January 2016 with Tosca, the opera that originally launched the company in 1944.

BD: Would that have a domino effect if the City Opera collapses?

Little: Not so much physically as it would psychologically. It is an extremely expensive business in order to bring opera of real quality. Richard Gaddes was head of the St. Louis Opera (1976-87) and with his limited budget has brought that company to a point of real distinction in the operatic sphere in this country. But he’s done it through very careful management, and extremely careful programming. [In November 2008, Gaddes was one of four recipients of the first National Endowment for the Arts's "Opera Honors Award" given at a ceremony in Washington, DC. The three other recipients were conductor James Levine, composer Carlisle Floyd, and soprano Leontyne Price

.] BD: He always seems to have something in each season that’ll attract major critics, such as Andrew Porter.

BD: He always seems to have something in each season that’ll attract major critics, such as Andrew Porter.

Little: That’s right, exactly, careful programming. He understands acutely his position in this sphere of opera, and this may be because of his long tenure at Santa Fe. He is not a competitor with Houston, and he is not a competitor with the Metropolitan Opera. He has built the St. Louis Opera, and it has a special nature and character of its own. That sometimes can take the form of a repertoire, or it can take the form of the way your house is organized, or the way you deal with your audience. He’s done it, and he’s done it very well. If it’s done that way, and if there are enough of those people out there who want to do opera that way, or do it their own way but carefully, the revolution will continue, but it still has a long way to go. However, I think that the ball is beginning to really slow down for cities of one hundred thousand, or a quarter of a million that say,

“Let’s have an opera company, and let’s build the sets, and let’s bring two stars, and we’ll do Carmen or La Bohème.” There’s plenty of room for development of operas and opera companies in those kinds of cities, or in a metropolitan area of half a million to a million if the mission is understood, and if the pencil is sharp, and if the people who are doing it are imaginative.

BD: So it’s got to develop in a really different way. They can’t just have two weeks of the Met on tour for their opera company?

Little: I’ve thought about this very seriously. At Furman University, we have absolutely glorious theatrical facilities, with 2,000 seats, a pit, a highly-sophisticated lighting system, all reasonably modern, built fifteen or sixteen years ago. It’s a perfect setting for the development of a regional company, but before I would become involved in anything like that, I would want to do a real in-depth study of what was possible, and what was feasible. After all, Atlanta is only two hours away, and the Met does eight performances there in April each year. So, you wouldn’t want to duplicate that role.

BD: No, you’ve got to do something else. You’ve got to bring another phase of opera. How do you get the public to want to come to operas they don’t know? They want to hear Traviata and Carmen and Bohème because they’ve heard them on the Met on Saturday afternoons for years, and they have the records of them.

Little: That goes back to what we were talking about, namely opera as being an elitist form. Perhaps there are different rows. One is the social row, in which the opera is underwritten by certain kinds of society and philanthropic types, who, through their lay educational processes or guilds, develop a certain amount of interest. Then, a certain number of people come, and they drag their husbands and or their wives by the nape of the neck to the event. Sometimes

— rarely — there are academic and artistic institutions in the immediate proximity to an operatic enterprise, which will form the basis of an audience which is inquisitive about those things. But it would be tough to sell _Le Prophète_in Tulsa...

BD: At least that one they can listen to. How do you sell Lulu... or do you?

Little: That brings up another topic, namely opera-on-television. I sang one of those seven performances of Lulu at the Met which was televised, and I don’t think any performance in the house was nearly as successful as that performance. [Video of that performances is shown above.] I have heard that not just from people who know me and who watched it because I was in it, but I’ve heard it from many people who don’t know me from Adam, who watched it and said they were absolutely intrigued, and were glued to the television set. This is because it is a work which really lends itself to television, much like a lot of the programs on Masterpiece Theater.

BD: [Noticing that we had been talking for well over an hour] Thank you so very much for all of your artistry, and for spending this time with me today.

Little: It

’s been a pleasure speaking with you.

Dave Wischnowsky, Tribune staff reporter Chicago Tribune

Frank Little may be gone, but the powerful voice that he long made soar to the ceiling of the Lyric Opera of Chicago still lingers, his daughter said.

"Professionally and in his public life, my father was known for his singing voice," Caroline Degenaars said about a man who spent 13 seasons in the 1960s and '70s making more than 140 performances as a leading tenor for the Lyric. "But in his private life he also had an incredible ability to tell stories and an unbelievable sense of humor. His voice and personality could light up any room.

"As his only daughter and his firstborn, my father also had an unbelievably comforting voice. What I'm going to miss the most is just his voice, in every aspect."

Francis Easterly Little, 69, of Winnetka died Wednesday, Feb. 22, of complications from cardiac arrest and a stroke in Rush North Shore Hospice in Skokie.

A former educator with DePaul University and the Music Institute of Chicago, Mr. Little also spent five seasons singing major roles at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

Preferring to perform in contemporary operas over traditional ones, Mr. Little was the principal tenor in a number of world premieres, including Alban Berg's "Lulu" at the Met and Krystof Penderecki's "Paradise Lost" at the Lyric, his family said.

He also appeared at La Scala in Milan and Opera Communale in Florence and once conducted a private command performance for Pope John Paul II at the Vatican, his family said.

Opting to spend more time with his wife, Lyn, and their four children, Mr. Little left his successful stage career during the late 1970s and made an equally successful foray into music education.

In 1978 he was named chairman of the department of performance studies at DePaul before moving to Greenville, S.C., in 1983 to become chairman of the music department at Furman University.

Mr. Little remained in that role until 1988, when he moved back to Illinois and became president of the Music Institute of Chicago, where he served until his retirement in 2003.

Born in Greeneville, Tenn., Mr. Little was influenced during his childhood by the voice of his mother, Mary, and the mountain hymns he sang each week at church, his family said.

In high school he began to fully recognize his vocal talents, which led Mr. Little to enroll at East Tennessee State College in Johnson City.

Paying his way through school with myriad jobs, including work in a traveling theatrical troupe, Mr. Little graduated from the college in 1958. Two years later, he received a master's degree in music from the College-Conservatory of Music in Cincinnati. In 1971, Mr. Little completed his doctorate in vocal performance at Northwestern University.

Having emerged from such humble beginnings to become a critically acclaimed tenor provided Mr. Little with a treasure-trove of tales, his daughter said.

"There was such a contrast from where his life started in the Smoky Mountains to where his life went, with him traveling all over the world and performing," she said. "So you can imagine all the stories he had. He had historical stories, stories about growing up in the mountains, funny stories, everything."

Even with all his accolades and achievements, however, Mr. Little remained proudest of his family, his daughter said.

"He told us over and over and over again that we were his greatest accomplishment," she said. "And he's the reason that we're all incredibly close."

Other survivors include three sons, Kent, Carter and Courtney; a sister, Winnie Pruett; and five grandchildren.

A memorial service will be held at 11 a.m. Saturday in Kenilworth Union Church, 211 Kenilworth Ave.

----------

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on July 30, 1982. A copy of the unedited audio was given to DePaul University. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1990. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.