Italo Tajo Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

Bass Italo Tajo

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Bass Italo Tajo

Directed, Taught After Opera Career

[Text compiled (and corrected) from obituaries in the Chicago Tribune, March 31, 1993, by John von Rhein,

and The New York Times, March 30, 1993, by Allan Kozinn.]

Italo Tajo was one of the most admired opera singers of the postwar era, an Italian bass especially renowned for his comic roles, an expert stage director and an influential teacher.

Professor emeritus of the University of Cincinnati College Conservatory of Music, Mr. Tajo died Monday of heart failure at Christ Hospital in Cincinnati. He was 77.

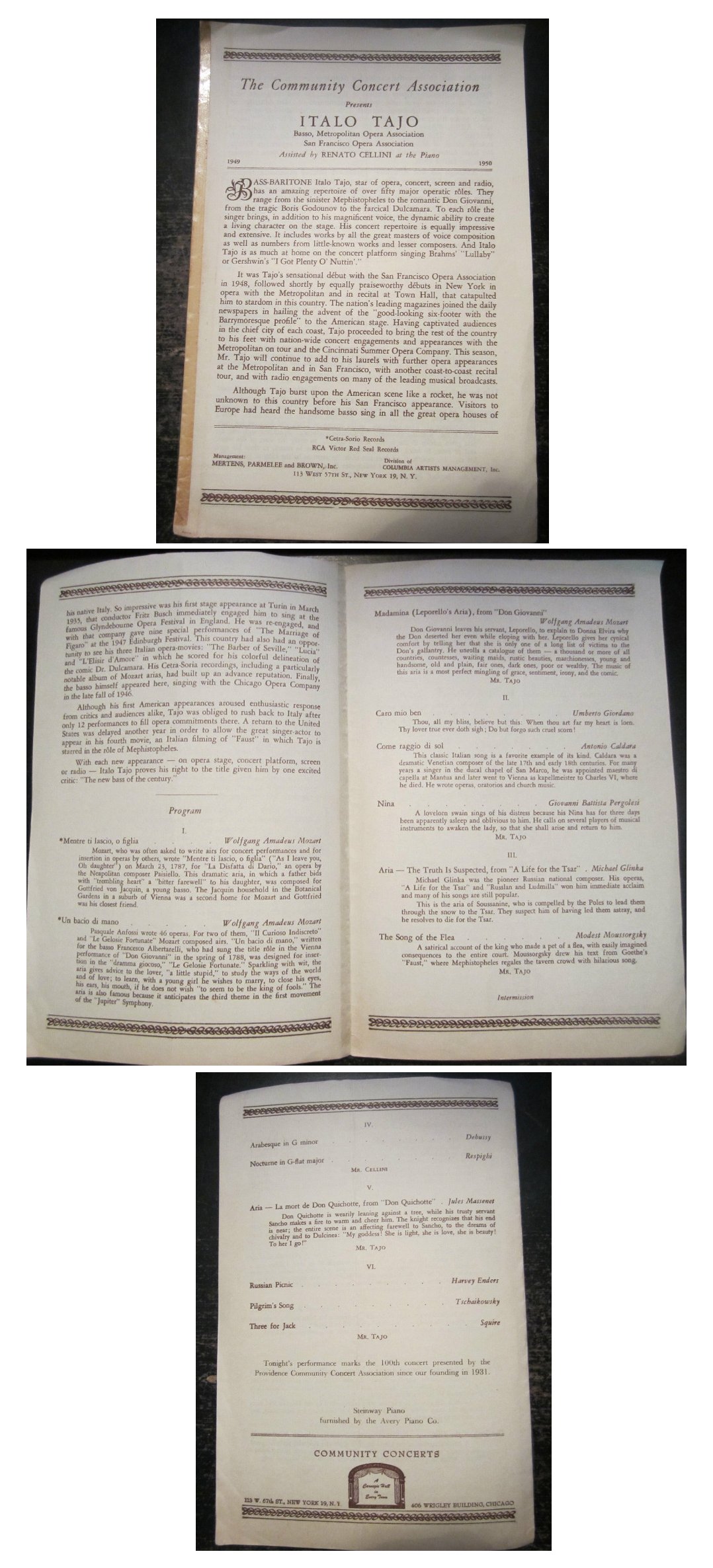

Mr. Tajo was born in Pinerolo, Italy, on April 25, 1915, and began his studies in Turin with Nilde Stinchi Bertozzi. He made his professional debut as Fafner in Wagner's "Rheingold" at the Teatro Regio in Milan in 1935, and in 1936 went to Glyndebourne as a chorister and an understudy in Mozart roles.

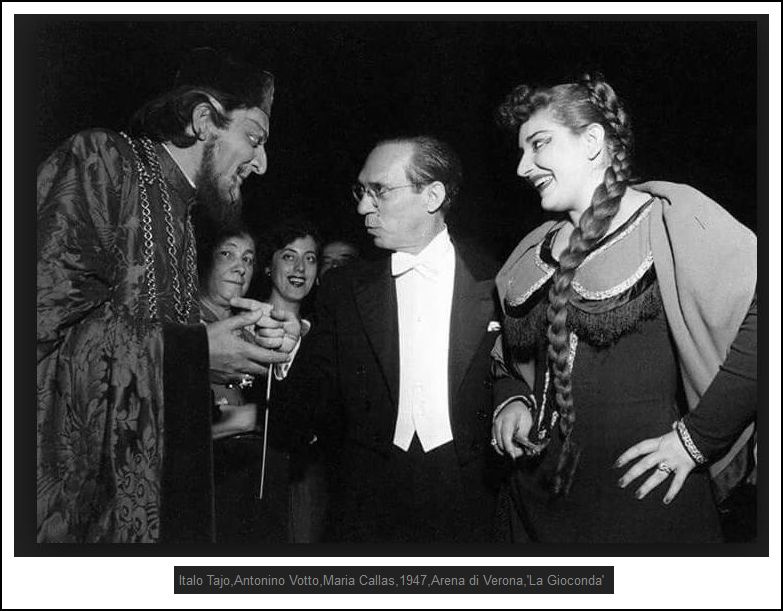

He made his American opera debut in Chicago, opening the season in 1946 with the Chicago Opera Company, as Ramfis in Verdi's "Aida" with Milanov, Baum, and Warren. He also sang Ponchielli's "La Gioconda", again with Milanov and Baum, and Castagna and Guelfi, and Saint-Saens' "Samson et Dalila" with Thorborg and Jobin here that season, all conducted by Fausto Cleva. He also sang in San Francisco, and made his Metropolitan Opera debut as Don Basilio in "Il Barbiere di Siviglia" in December 1948.

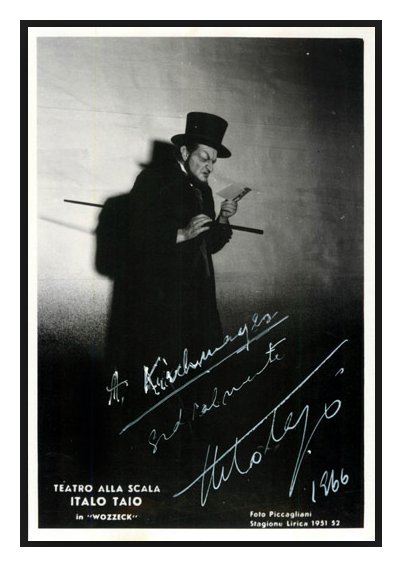

His repertory included several contemporary works. He sang in the Italian premieres of Berg's "Wozzeck" in 1942, Walton's "Troilus and Cressida" in 1956 and Shostakovich's "Nose" in 1964. He also created roles in works by several composers, including Luigi Nono and Luciano Berio.

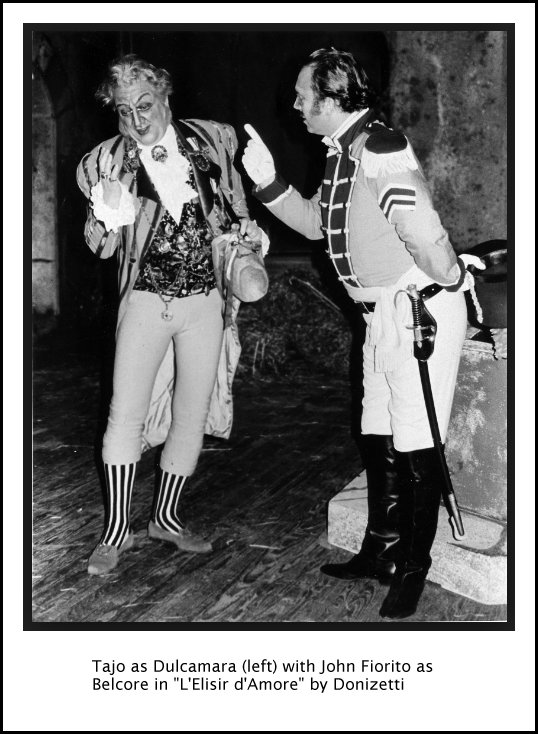

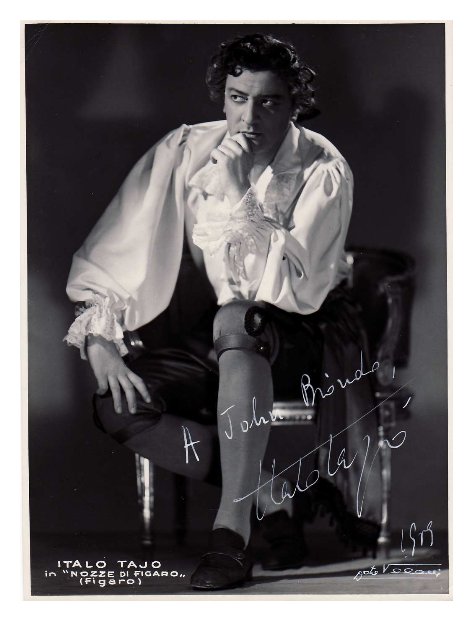

But it was in the standard Romantic repertory that he did most of his work, and he made his name playing a combination of serious and comic roles -- Banquo, Ramfis, Figaro, Don Pasquale and Dulcamara -- in the 1940's.

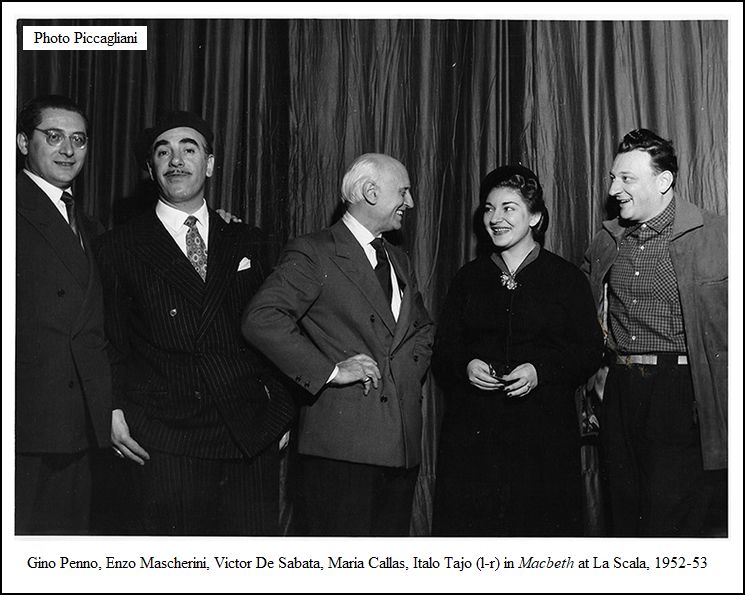

Mr. Tajo made several recordings, including Mozart's "Marriage of Figaro" with a Glyndebourne cast in the mid-1930's and La Scala recordings of Verdi's "Macbeth" and Giordano's "Andrea Chenier."

Through the 1970s and '80s Mr. Tajo (pronounced Tah-yo) appeared with Lyric Opera of Chicago in various supporting roles, including the Sacristan in Puccini's "Tosca" and Alcindoro and Benoit in "La Boheme." He staged Massenet's "Don Quichotte" at the Lyric in 1974.

"He was the most magnetic stage presence and personality I have ever seen," said Danny Newman, longtime Lyric Opera publicist.

In 1966 Mr. Tajo moved from Rome to Cincinnati to help start the opera department at the University of Cincinnati. Among his students there were Kathleen Battle and Barbara Daniels.

He is survived by his wife, Inelda, and a daughter, Cecilia Benedett.

-- Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD

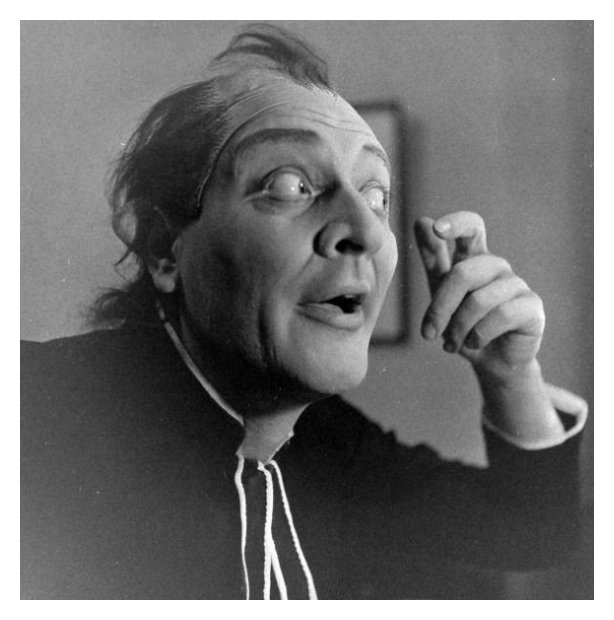

If there is one word which reveals the most about Italo Tajo, it would be

‘communication’. This is what he conveyed in his performances and what he stressed in his teaching. Life, to him was simply being able to communicate with the audience and with others on the stage.

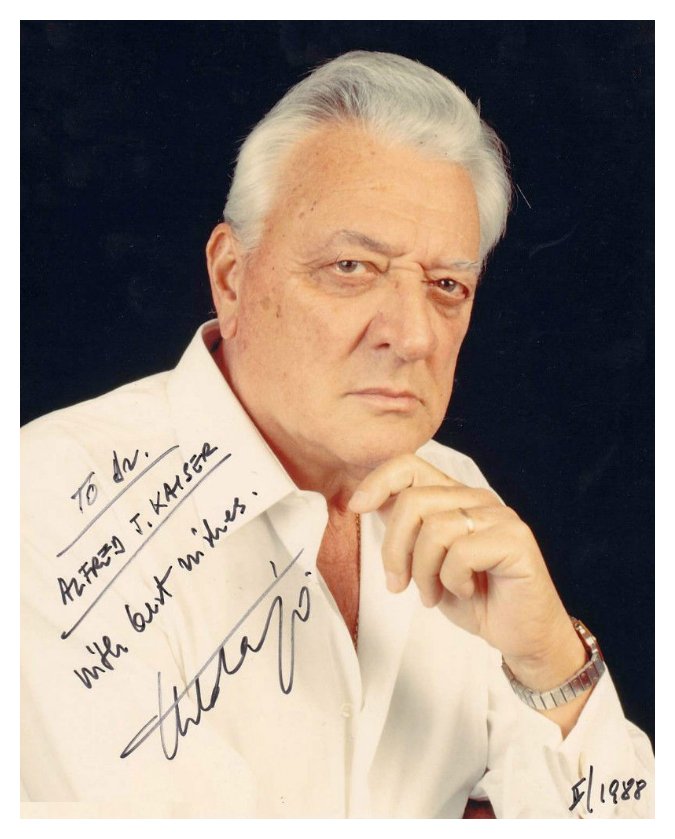

The color photo at the top of this webpage shows a man who is deeply concerned and perhaps even somewhat angry. Let me assure you that during our conversation in his apartment in the fall of 1982, he occasionally seemed that way, but mostly he was a kind and benevolent soul, with flashes of wit and an abundance of charm. The photo below conveys that side of him, and is what I felt during our time together.

He spoke with me about many aspects of his career, and shared the knowledge and style he had learned in a long and respected life. While modest almost to a fault, he was aware of his achievements and always felt secure in his attitude and views. It was truly a pleasure to spend an hour with this revered gentleman, and after airing portions a few times on WNIB, I am pleased to be able to post the entire encounter on this webpage.

While setting up the recording machine, we chatted about his various roles, including the newest ones that involved interesting characters . . . . . . .

Italo Tajo: In the last ten years or twelve years, I am doing all new roles for me

— Alcindoro, Benoît [both in La bohème], Sacristan [Tosca], and at my tender age of 67, I have a role debut as Geronte in Manon Lescaut. [This occurred on March 19, 1984, at the Met. He reprised the role there in 1986, 1987 and 1990, also singing it in Firenze (1985) and recording it for Decca/London conducted by Riccardo Chailly, starring Kiri Te Kanawa and José Carreras.] [A photo of Tajo as Alcindoro is shown in my Interview with Ken Recu, Captain of the Supers at Lyric Opera of Chicago, and there are two other photos of Tajo being made up by Stan Dufford.]

Bruce Duffie: Why the desire to go into small roles?

IT: It is not having so much so I can talk during the day in my classes. Being 67, having 47 years of career on my shoulders, I just go back to roles that don't demand much vocally. They don't demand training of voice or practicing!

BD: [Facetiously]

“Italo Tajo, Lazy Old Man.”

IT: [Laughing] No, no, not at all!

BD: You're really a man of the theater! Is this what prompted you to go into these character roles, these small characterizations, to bring these characters to special life?

IT: Characterization was the very first thing for me when I started singing! I always thought about characterization. When I was very young, I was into engineering, designing shows, knowing proportion and numbers; but theater was what I wanted to do, really, and it was not opera. It was acting! The very first love of my life was acting! I wanted to become an actor. Not that I wanted to become an actor, but I think I was an actor! My destiny was theater. I discovered I could sing in my church, in my small town where I was born. I was 16 and somebody told me,

IT: Characterization was the very first thing for me when I started singing! I always thought about characterization. When I was very young, I was into engineering, designing shows, knowing proportion and numbers; but theater was what I wanted to do, really, and it was not opera. It was acting! The very first love of my life was acting! I wanted to become an actor. Not that I wanted to become an actor, but I think I was an actor! My destiny was theater. I discovered I could sing in my church, in my small town where I was born. I was 16 and somebody told me,

“You have a voice! Why don't you study voice?” From the theater they were already reciting, playing drama, learning Shakespeare in Italian and Goldoni by heart. Then came opera! Then came the voice and that was theater for me. I always treat it as theater, as character!

BD: Is opera more theatrical today than it was 40 years ago?

IT: Generally speaking, yes, it is more; but this doesn't mean that we didn't have at that time good actors in opera! It's just different, and sometimes the emphasis is too much toward the theatrical to the detriment of the voice.

BD: [Surprised] Really? Why?

IT: It's still the voice. Voice is still the medium to communicate, and is important! Now the tendency for the new stage directors is doing things that are out of the context, out of the spirit of the composer. Ugh! That is wild and unjust to opera!

BD: Will it kill opera?

IT: Eventually.

BD: [surprised] Really???

IT: Eventually, I say, because I think that one of the things we should do is respect the composer's ideas and ideals! If you go away from that too much, then you do something that doesn't respect the spirit of the real composition. If you see Gianni Schicchi in modern 1920 Chicago gangster style, when you talk about a mule and the mills [la mula and i mulini di Signa, the most prized items in the will of the late Buoso Donati] even making sense in the translation you have to adjust to the new period! It goes down very much to ignorance and improvisation.

BD: Ignorance of the text or ignorance of the style?

IT: Not having the willingness to respect and document yourself in what you are really doing! They take a piece and just go into it superficially. The director will come with the libretto but without knowing the music, and they think they can do anything; or they don't tell you anything! They are The Directors!

BD: So all of these extra things don't say anything then to the public, and don't add anything to the picture?

IT: [Laughs] Heh heh! It is because they don't know. Ignorance is the big thing nowadays, and presumption!

“I know everything without the need of documenting myself, or knowing what happened before!”That, for me, is a big fight because I am, as they say, a traditionalist. I was an innovator in theater, as an actor! I did many innovative things while respecting the character of the composer and his composition!

BD: What if someone today is doing it the same way that Italo Tajo did 40 years ago?

IT: I don't expect anybody to do something that I did. Somebody else can do something different, but in an innovating way that makes sense, and is according to what the composer demanded. It's a very abstract idea, but it's very real! If you have Butterfly, you cannot go away from Japan. If you have Schicchi, you can't go away from Florence! The issue of what happens nowadays very often is they go away from that! This is the betrayal that I fight against. I am in a Conservatory of Music and I have my fights with some of the faculty. They come and want to do things. The conservatory should be a place where you learn what has been done. This is to prepare yourself to do something that can be innovating, but on very classic and solid knowledge!

BD: So you are preparing them to continue a line?

IT: Oh yes!

BD: You don't want theater to stand still.

IT: Oh no! Not at all! Not at all!

BD: You want it to continue to grow and develop.

IT: To grow, but in the right direction, not in the wild [makes a gesture and a noise] psshh! Not eccentric!

BD: I see on your desk you're preparing the directions for Falstaff for your students. Have you also directed professionals as well as students?

IT: Not Falstaff, but I have done Trovatore, Tosca, Barber of Seville lots of times, and the first Don Quichotte here at Lyric Opera of Chicago.

Italo Tajo at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1971 - Tosca (Sacristan) with Martin/Kubiak, Bergonzi, Gobbi, Giorgetti, Andreolli; Sanzogno, Gobbi, Pizzi

1972 - Bohème (Benoît and Alcindoro) with Krilovici/Bruno, Merighi, Patrick, Zilio, Ferrin, Holloway; Bartoletti, De Lullo, Pizzi

1973 - Tosca (Sacristan) with Kubiak, Tagliavini, Gobbi, Giorgetti, Andreolli; Bartoletti, Gobbi, Pizzi

Bohème (Benoît and Alcindoro) with Cotrubas/Wells, Pavarotti/Merighi, Patrick, Zilio, Washington, Giorgetti; Bartoletti, De Lullo, Pizzi

1974 - Don Quichotte (Director) with Ghiaruov, Foldi, Cortez, Paige; Fournet, Samaritani

1976 - Tosca (Sacristan) with Neblett, Pavarotti, MacNeil, Giorgetti, Andreolli; López-Cobos, Gobbi, Pizzi

Love for Three Oranges (Cook) with Barlow, Little, Titus, Gill, Dooley, Trussel,Kuhlmann, Powers; Bartoletti, Chazalettes, Santicchi

1979 - Love for Three Oranges(Cook) with Suliotis, Little, Nolen, Gill, Dooley, Trussel, White, Halfvarson; Prêtre, Chazalettes, Santicchi

Bohème (Benoît and Alcindoro) with Mitchell/Soviero/Niculescu, Shicoff/Prior/Moldoveanu, Romero, Zilio, Ramey, Nolen/Stone; Chailly, Frisell

1982 - Tosca (Sacristan) withBumbry/Marton, Luchetti/Domingo, Wixell/Nimsgern, Kavrakos, Andreolli, Cook; Rudel, Gobbi, Pizzi

1983 - Bohème (Benoît and Alcindoro) with Cotrubas, Ciannella, Raftery, Hong, Washington, Galbraith; Navarro, Copley, Pizzi

1987-88 - Tosca (Scaristan) with Scotto, Ciannella, Milnes/Nimsgern, Patterson, Andreolli; Tilson Thomas, Kellner, Pizzi

1989-90 - Tosca (Sacristan) with Marton/Neblett, Jóhannsson/Giacomini, Nimsgern, Runey, Andreolli; Bartoletti, de Tomasi, Pizzi

BD: Yes, that was a wonderful production!

IT: I was asked to do this because the opinion of the great Lyric Opera of Chicago, I was a good Don Quichotte as an actor, so they thought I could do something, and that I could respect the spirit of Massenet. They were doing it in Paris in a production by Peter Ustinov, and they were going to bring the production here. They didn't, because somebody went there and said this is not Massenet, this is Ustinov! Strange, you know! That's where [Pier Luigi] Samaritani [the designer] and myself came in.

BD: Does your approach to direction change when you're working with students or with professionals?

IT: In the execution it changes, but not in the concept. The execution changes because when you have a professional, they have already certain guidelines and certain opinions. You try to get through and get them close to your own conception when you can do it, but if the resistance is too much, you just let it go. You don't have conflict with anybody. With the students, it is a different story. A student is like a virgin! They have to learn the style from scratch, what it is about. As much as our school is quite a good school, you cannot have that. We have a large number of students and productions are double cast. But you must give them some guidance and some acting instructions that you don't do to professionals. First of all, in professional life, you don't have time to do that.

BD: So you have more time for each production at the conservatory?

IT: I take two quarters for each production, my friend. I do only two productions a year in nine months.

BD: But it's not as intensive. Here at Lyric you work every day for three weeks.

IT: I tell you something. When I was very young, I was 19, not even 20 years old, I did my debut in Torino. Maestro Fritz Busch was conducting the entire Ringin Italian at the Regio Theater in Torino. After that, he asked me if I wanted to go to Glyndebourne with him, and naturally I was very enthusiastic about it. There I learned instrumental singing, and Mozart. I learned also that productions require a great deal of time to prepare. Six weeks they were, in Glyndebourne, for each production. Six weeks every day but Sunday, from 9 o'clock in the morning to 5 o'clock in the afternoon! So I have this kind of background, and I don't believe in improvising things. The actor doesn't improvise anything. One may have a great talent, but he doesn't improvise. He goes to the text and deep into the character psychologically. I do the same thing with my students at the school, for opera. So, this is what it is. I cannot stage anything in two weeks at the school

IT: I tell you something. When I was very young, I was 19, not even 20 years old, I did my debut in Torino. Maestro Fritz Busch was conducting the entire Ringin Italian at the Regio Theater in Torino. After that, he asked me if I wanted to go to Glyndebourne with him, and naturally I was very enthusiastic about it. There I learned instrumental singing, and Mozart. I learned also that productions require a great deal of time to prepare. Six weeks they were, in Glyndebourne, for each production. Six weeks every day but Sunday, from 9 o'clock in the morning to 5 o'clock in the afternoon! So I have this kind of background, and I don't believe in improvising things. The actor doesn't improvise anything. One may have a great talent, but he doesn't improvise. He goes to the text and deep into the character psychologically. I do the same thing with my students at the school, for opera. So, this is what it is. I cannot stage anything in two weeks at the school

— not because I cannot, but because I don't want to do it!

BD: You want the students then to understand.

IT: I want the students to understand that the process is long and detailed! Without that, you are always improvising things and you are not prepared! There is no first performance for me, never been in my life a first performance! I was prepared as if I did a hundred performances before! With this principle is my success in life. This is the result of my little talent

— now I can say that! — but also hard work and this kind of discipline. I arrived in the world in a kind of category that is nice for myself, telling myself, “It's not enough, this is not enough, do some more, make it perfect, perfect.” With this in mind, I have the same philosophy for my students.

BD: This is fabulous that you're passing this along to them! Do they accept it?

IT: Yes, they do! If they don't, they just [makes a whistle-like sound of dismissal] fyiut, out! It's very simple! They're not getting the message, they're not worthwhile! I have my little fights there, but generally speaking, I am loved by them. We do productions that are unbelievable! Yes! They are very good, even if there are people that are not so very talented. I am bragging about it not because I am doing it but because time is doing it for them! Time! Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Friday night from 7:30 till 11:00, Saturday afternoon and Sunday afternoon from 2 to 5:30. This is a regime of staging rehearsals that I have for six to seven weeks before going on the stage! Then we stay on the stage one week for the winter production and two weeks for the spring production. So you see, I give them time. There are two casts always, to be covers, and to give many of them, talented or not, this kind of experience.

BD: When you're directing, do you have the two Falstaffs there and the two Nannettas there, or do you do two separate rehearsals?

IT: Sì sì sì sì sì! Always together. Oh yes yes yes. That spares time for me, and they help each other. They look at each other. I believe in learning by seeing people doing things.

BD: You give them a direction, and it's almost like they can watch themselves do it!

IT: Yes! And then, according with their possibility, their personality, they will develop that. They will change a little, but fundamentally, physically, the production is there, as you see there [pointing to the drawings on the desk]. Physically it will be there. Then little nuances which are part of the human being, the vibrating human being, come along and they will help each other. You know, I'd never been in any acting school in my life. My school was theater. I skipped my dinner to go. I was born in Pinarolo and lived in Pinarolo, 36 kilometers from Torino. I studied voice in Torino, so I took the train, one hour on the train, to go to Torino. I had the lesson in the afternoon and my father gave me five lire. That was dinner for me or theater, and I always skipped the dinner there. I would never eat, but I went to the theater! That was my school! My experience was watching Italian actors playing Shakespeare, playing Plato!

BD: Spoken theater, not opera?

IT: No! Opera, [makes a sharp quick raspberry sound] ppp! I couldn't care less about opera! I saw my first great operas in Torino with Aureliano Pertile singing Lohengrin in Italian or Ballo in Maschera, but I was attracted by the theater!

BD: Does Shakespeare work in Italian?

IT: In Italian, sure! It is more easy to recite. There was a great, great actor Ermete Zacconi playing Ibsen, Goldoni. I saw many, many great actors in Torino in about three years, and that was my school, my way of learning. They said I was theatrically oriented!

BD: I asked you about Shakespeare in Italian. Does opera work in translation?

IT: I do all my major productions, in English.

BD: Are you happy with them that way?

IT: [Without hesitation] Absolutely! I adjust some translations, also. You have to. For example, I did I Quattro Rusteghi by Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari. I don't know if you know this piece.

BD: I have heard it on tape, but have not seen it.

IT: School for Fathers is the title. Edward J. Dent made the translation, and reset the action into England. Now, for me, it's a profanation to bring that play into England, into London! This is Venetian. The spirit of Wolf-Ferrari is Venice, it is Goldonian. We used to call him My Father Goldoni! Wolf-Ferrari was enchanted with Goldoni! So little by little I made some changes, and then I put down a manual for the students, a translation of the commedia dell'arte comedy of Goldoni, the spirit of Venice. I gave them Pietro Longhi paintings, so then they had an idea, because they didn't have any idea of what Venice was or what Goldoni's spirit was! We are talking about the theater that is the basis of Donizetti and Rossini opera buffa characters! Once you do those in School for Fathers, then you can play any old man in Donizetti and in Rossini, my dear! That is the Bible! I wrote really a dissertation on these things and then gave it to them. In the beginning they didn't understand much, then little by little the came to it. I saw them crying after the last performance because it was over! So there is kind of a reward in what I am doing there, a great reward.

BD: Can you teach someone the art of buffo playing, or is that something you have to be born with?

IT: No, you can help them for sure. You are born with certain abilities. You are born an actor. This I believe, and that you have a talent, but talent without hard work, forget it! With talent and hard work you will achieve something.

BD: What about no talent, but hard work?

IT: No talent? I saw miracles happen. I saw the first miracle happening in '47 when I was in Glyndebourne, singing Figaro in Marriage of Figaro with Carl Ebert staging it. He was a great giant! An English tenor was singing Don Basilio, and when he came he was absolutely crude, nothing! I thought this is a lost case! But he studied at home, and after a few weeks he was in the picture beautifully with the others. So you can achieve little miracles in this respect if you give time and the right instructions. But you cannot confuse people. If you confuse people, goodbye. They are already too much confused about this music and words and the voice and projection and all these things. So it's hard work, my dear.

BD: Do you find that the students today, your nineteen and twenty year olds accept the music of Rossini and Wolf-Ferrari and Verdi?

IT: In my institution, yes. Last year I did The Barberagain. I did Cenerentola already twice in 16 years because I believe it's very valuable for the students. Vocally speaking it is good. I did Albert Herring, and when I had a soprano to kill, I did The Consul. This singer was already older and she wanted to do it, and she didn't care about making a career. So I could kill her with that role. [See my Interviews with Gian Carlo Menotti.]

BD: Are there operas that you stay away from, that you won't do in Cincinnati?

IT: Absolutely! And I fight because this is part of the ignorance that I was talking about before. People are improvising, and they don't know what they're talking about regarding vocal problems. If you imagine, when I came back from sabbatical in '77, at the first meeting we had a conductor asked me,

“Why don't we do Don Carlos?” I answered, “With whom???” People want to put faculty into the productions and do what Indiana University does. I am not for that.

BD: You don't want to sing Philip II again?

IT: No! I have another mission in life now. I am there for the students. The students must have the experience of performing. I don't say that the experience of performing with some great cast members is not valuable. But when I have a production, it must a students' production, and they must find pieces that are good for their own voices! They wanted to do Ariadne auf Naxos! This is what I am talking about

— ignorance and incompetence! Often in academia you find individuals [professors] that simply want to put on their résumé that they did this and this and this! For no other reason, you know. They say they care about the students, but actually I doubt it!

BD: I was talking with a young singer last year, David Gordon, whom you may know...

IT: Sì.

BD: ...and he was saying that when he was younger, the operas he enjoyed seeing were Otello and Don Carlos because they were exciting.

IT: True.

BD: But now that he is a little older, he likes works such as Barber of Seville and L'elisir d'amore. How can you talk to a nineteen year old and get them to see the difference between Otello and Elisir d'amore?

IT: As a responsible instructor, you allow everyone to have their own taste. But if you are going to sing it, it's my duty to tell him,

“Don't singOtello, don't sing Don Carlos because you are only nineteen. It is something you are not prepared to do. At nineteen you are a baby. Le ossa non sei fatta, your bones are not made, as the old Italian saying goes.” One of the big troubles in the conservatory is the repertoire. At nineteen and twenty, they sing even arias they shouldn't touch because they are too young. BD: Do the students nowadays prefer to work on roles they will sing a hundred times rather than something they will do just once or twice?

IT: The students nowadays are often too impatient. They want to do everything done, done, done, done. Not with me there! I tell them they will learn how to do it. Little things, small things...

BD: A foundation?

IT: A foundation! And from that they can go everywhere. They can go to the stratosphere, but only if they know the basic things. If you jump without having your foot down, where do you jump?

BD: On your face!

IT: That's right. [Both laugh]

BD: In your career as a bass, did you ever sing characters you didn't enjoy?

IT: Some characters I didn't enjoy in the beginning. The Doctor in Wozzeck, for example. When I started to learn it, I received only my part, not the entire score. Serafin sent me that, and it was the first time I looked at dodecaphonic music in my life! That was in '42, during the war, and Tito Gobbi was the protagonist. Since I am a researcher, the first thing I did was to buy Woyzeck the drama, so I could learn what it was about. Then when I read the score, little by little I enjoyed. When I found the way of dealing with the new music, then I enjoyed it. The same thing happened when I sang Ochs in Rosenkavalier in Italy. I had to read the role in Italian. It was a new style.

IT: Some characters I didn't enjoy in the beginning. The Doctor in Wozzeck, for example. When I started to learn it, I received only my part, not the entire score. Serafin sent me that, and it was the first time I looked at dodecaphonic music in my life! That was in '42, during the war, and Tito Gobbi was the protagonist. Since I am a researcher, the first thing I did was to buy Woyzeck the drama, so I could learn what it was about. Then when I read the score, little by little I enjoyed. When I found the way of dealing with the new music, then I enjoyed it. The same thing happened when I sang Ochs in Rosenkavalier in Italy. I had to read the role in Italian. It was a new style.

BD: [Gently protesting] But Rosenkavalier is more melodic than Wozzeck.

IT: Oh sure, but it is the first approach to something.

Something more in your own nature is very easy. Some music is more difficult, the intervals are different. But every time you are given a role that you don't like much in the beginning, you start liking it dramatically if you find your motivation. You get interested in the recreation of the role, and any role becomes beautiful. One of the first roles that I studied was Sam in Ballo in Maschera, which, in my opinion, is a very dry, arid role, a supporting role. But I enjoyed it. I didn't enjoy so much the few roles where I was not prepared. I was in a hurry to prepare, so I couldn't really enjoy them. But the ones that I had time to prepare, to enter, to personalize the role, those I liked. I sang 186 roles before I did Sacristan and Benoît. That includes Boris Godunov, Philip II, and all the Verdi roles except Vespri Siciliani and Nabucco, and the first one, Oberto.

BD: Did you do too many roles?

IT: [Matter-of-factly] No. I was happy. It is an entirety. It's a question of the way you think. Some say,

“I will specialize in five roles and I will be great.” I don't care to be great or not great. I enjoyed everything I did. The old Timur in Turandot was an incredibly beautiful role. Colline in Bohèmewas a personification of beauty, of poetry. It was beautiful. I don't care if I sang it three times or a hundred times. The joy was putting myself in that role and doing something different each time. BD: Were there any roles that you wanted to sing that you never got a chance to do?

IT: [Pauses, then heaves a sigh] Ah, that I don't know.

BD: Maybe Procida in Vespri?

IT: No. Maybe one, and this is Falstaff. Falstaff was offered to me by Victor de Sabata one year at the Scala. He wanted me so much, and I started really trying to practice vocally this thing, but it was too high for me. I have a voice that could sing Ochs in Rosenkavalier, which is very high. It's higher than Falstaff, but it's different.

BD: The tessitura?

IT: The tessitura is different. You can make falsetto up there, but it is different. It was pleasantly easy for me. I could talk up there beautifully, but in Falstaff there were a few phrases... At the end of

‘honor’ monologue in Act I, there is the G! I didn't have the G! I sang Schicchi at the Met because when Edward Johnson told me he would give me Faust but I must also sing Schicchi, I said I would be glad to sing Simone! But he said no, not Simone but Schicchi! I said I don't have the G, but he said it doesn't matter! I didn't have to put it in! So I sang Schicchi without the G! So my vocal construction was that I knew myself. I knew what to sing, what I could sing or not, and this is the secret for everybody that wants to be on the stage.

BD: Was it easy for you to say

‘no’ to a role?

IT: Yes, it was not so difficult. The first

‘no’ that I said in my life was to the Scala for the role of L'Orco in Piccolo Marat by Mascagni. I was in my early twenties and was in Rome when I received a letter from the Scala offering this role because Andrea Mongelli, a bass, broke his leg and couldn't sing it. I looked at this thing which I'd never seen before, and I said,“Ma, no, this is too heavy for me.”I went to Ricci and asked him, but he said I was too young. I had my own opinion, but that told me no, so I wrote to Ghiringhelli at the Scala and said I was sorry. I didn't go to the Scala for two years because of that. They closed the door to me! Then at twenty-seven I sang Rosenkavalier, but the tessitura, the weight of the voice, I didn't have! Also, I never sang _Mephistophele_by Boito.

BD: [Dismayed] That's too bad, that's a pity.

IT: Ma no! When they offered that part to me, it was too soon to finish my career! For me, that was considered a role to finish vocally! After doing that, you are just finished! [Both laugh] You go in Ischia, or a rest home some place, and I didn't want to do that. I sang the Prologuein concert, and happily so. I studied it and found out what I could do with my own voice. I wasn't this giant up there, and I knew it! So when they offered me that full part, I said no thank you, not yet.

BD: But you did the Gounod!

IT: Oh, the Gounod, yes, hundreds of performances. In the San Carlo theater in Naples, I sang 43 performances in Italian. Then I come here in the States, and I sang it in French many, many, many times.

BD: Did you have to relearn it from the beginning in French, or just the new words?

IT: Yes, in a way you really relearn a role because of the language.

BD: Do you have to get it into the voice differently?

IT: For certain inflexions, yes. There are certain subtleties that are different in French. It's something that is better than in Italian, really. The original is better, yes. In the Garden Scene, especially, it's more in the language.

BD: I hope your students thank you very, very much for all the help that you've given them.

IT: Well, it's my pleasure to do that, really! I was the lucky one to come to Cincinnati in 1966. Really, I considered that very seriously, to be honest. For me it was a great experience after so many years of theater, of being able to be in a conservatory, to help young people understand their problems, and to give something of what I learned myself. It's a great, great thing that happened to me.

IT: Well, it's my pleasure to do that, really! I was the lucky one to come to Cincinnati in 1966. Really, I considered that very seriously, to be honest. For me it was a great experience after so many years of theater, of being able to be in a conservatory, to help young people understand their problems, and to give something of what I learned myself. It's a great, great thing that happened to me.

BD: Are there some of your singers who are now major stars?

IT: One is Kathy Battle, who is very well-known, and another is Barbara Daniels, who

is doing very well. She will sing Bohème next year at the Met, and we'll sing together, incidentally! [Note: Ms. Daniels sang twelve performances at the Met with her old teacher — eleven Bohèmes, in which she was Musetta and he was Benoît/Alcindoro, and the Centennial Gala II, for which they performed the Norina/Pasquale duet, the scene with the famous slap!] I also have a few students in Germany, that are doing very, very well. The fact of having students that come from CCM is also luck. I believe that it is not really the teacher that makes the student, but it is the student that makes the teacher. The talent is there, then you can give some ideas and some of your experiences. This is wonderful, I have to say that, but if the talent is not there, you can preach in the desert and nothing happens!

BD: It seems that you've been very fortunate as both performer and as teacher.

IT: Yes, yes, yes. I taught two-years-and-a-half of voice at the conservatorio in Torino. I don't think I am a

‘voice teacher’.I can give advice. I know exactly what the voice does and does not, but for me it was aggravating to have the studio with 16 students. I was looking for something different. I have the opera workshop. When I started staging, I could get rid of the studio of voice and I was very happy! At the moment I have a class called Operatic Characterization. That is a specialized class for the best ten or twelve students. They learn how to recreate a character and research a character. It is an acting class.

BD: So they don't learn a character, rather they learn how to create a character!

IT: [With hushed enthusiasm] Any character! We take a scene from literature, and then we start talking about the entire play, the background, the way we research the background, the way of analyzing the text, the way of analyzing the music, and then how to do it. That is the most important thing. It is an acting class, actually, more than anything else.

BD: Would you work with a composer?

IT: [With relish] Oh, I would! I would love to!

BD: Would this help a composer to make opera more theatrical?

IT: [Chuckles] The collaboration between director and composer is always very very helpful. One can help the other. It's the same way with the librettist and the composer. We see that with great composers and great librettists. Look at the Falstaff as an example. Boito and Verdi! Boito was milking the old man, finally convincing Verdi to write Falstaff. What a genius was Boito.

BD: It's one of the great regrets of my life that they did not do King Lear.

IT: Listen to the honesty of this old man Verdi. That great mind was afraid of touching King Lear! Can you imagine the modesty? You can't teach that, nowadays, to be modest about what they are doing! He was God!

BD: I fantasize about that... Otello, then Lear, then Falstaff!

IT: Did you read the letters about Otello?

BD: Yes.

IT: He talks about Iago. When Morelli, the painter, sent him the poster with the little man Iago, kind of deformed, Verdi writes,

“No! He must be handsome. Everybody has to like him. They don't know the devil that is inside him.”

BD: He almost called the opera Iago!

IT: [In hushed, reverent tones] Unbelievable, unbelievable man. Verdi's a genius. Mozart, Verdi...

IT: [In hushed, reverent tones] Unbelievable, unbelievable man. Verdi's a genius. Mozart, Verdi...

BD: Wagner?

IT: Wagner... [thoughtful whistle] phew! The three of them... [Gasps in awe]

BD: Is there anybody else that belongs with those three?

IT: Eh well, you got me there! [Both laugh] I don't know. Rossini, but for me he's another kind of genius. There is a humanity in that composer that everybody forgets, especially in this country! They are doing Barber, they are doing a farce, a circus! No, this is a comedy of characters — as Nozze di Figaro is! There is no difference! They masturbate the piece. They destroy the human values there in Barber of Seville! They make a farce!

BD: When you do The Barber of Seville or Marriage of Figaro, should you understand the Beaumarchais?

IT: Absolutely! My recipe in researching a character or doing the staging is humanity, a certain humanity in the play and in the players, the characters. You don't fail if you go deep into humanity. Then you find all the values of the piece because when a genius like that wrote music, he has underlined the humanity of the characters!

BD: Maybe this is why we're losing the humanity in our daily lives today

— because of electronics, because of robotics and computers.

IT: Well, maybe. [Chuckles] That could be a point, a good point! But it is in the approach of theater, theatricality, that is important for me, that helped me. That's why I'm preaching the same thing that helped me in my own career. This is for my own satisfaction, also, so that they never be superficial. Any little character, there is deep inside them great humanity. When you look for that, it's half the success in what you are doing! If you don't look at that, you don't go far. The rapport between audience and stage is human. This electronic medium of television takes away that humanity in the opera. In the opera, because there is the music and there is the singing, electronics is not natural. The forceful atmosphere is in the theater, and the fact is that it is not natural that you sing. There is music, but it's not a naturalistic way of playing a drama. But you accept that! The distance and the music in this medium of television becomes difficult to realize. The rapport in the theater is the humanity that is there. If you don't have that, you don't dig into this humanity.

BD: Even in the big theaters?

IT: Even in the big theaters, sure! It doesn't matter because from the point of the interpreter, of the actor, if you are not convinced of the humanity of your character, you don't project anything. The voice doesn't project much if it's not surrogated by feelings, and the thinking and feelings are the humanity of the character.

BD: So it's the voice and the head and the heart?

IT: The voice by itself is beautiful, but it is not enough. It can be very boring. Even the most beautiful sounds can be boring!

BD: Are we losing the heart today?

IT: I don't know if we are losing it. Some of us lose it and some of us still have it. It's our duty to remember that. I learned in the very beginning that I had a responsibility, being an actor, being a singer. I had the duty of educating my audience, to give the audience the good taste, to make people better! And I would like to see this continue. Nowadays, sometimes I am not convinced that this happens, really. Performers are distracted with other things, especially money and going around in planes. They lose that kind of educational function of this theater, also. I believe in this play-with-music, and we are the interpreters of this medium. It has something to do with the taste of the audience. We are the ones that give it to them, and when they see a bad Rossini production on the stage, it is a sin! This is betraying Rossini and giving to the audience something that is not good! Perhaps it is just for a laugh. Ha ha ha, everybody laughing... no! In Barber of Seville, there is a moment that Rosina suffers in the last act, and the audience must get this moment of emotion with a little tear in the eyes! I don't find that generally in Rossini performances. I see just people clowning around and singing [imitates in a self-indulgent, mushmouth sort of barking... then he breaks off, making dismissive noises]. Maybe I demand too much...

BD: [Protesting and reassuring him] Oh no no no! To demand for Rossini, that is the gift!

IT: I hope so.

BD: Thank you so very much for everything you have given and continue to give us.

IT: You're welcome. I thank you.

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at his apartment in Chicago on October 23, 1982. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1989, 1990, 1993, 1995 and 2000. A copy of the unedited audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to Doug Han for his help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website,click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.