Mirella Freni & Nicolai Ghiaurov Interviews with Bruce Duffie

. . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

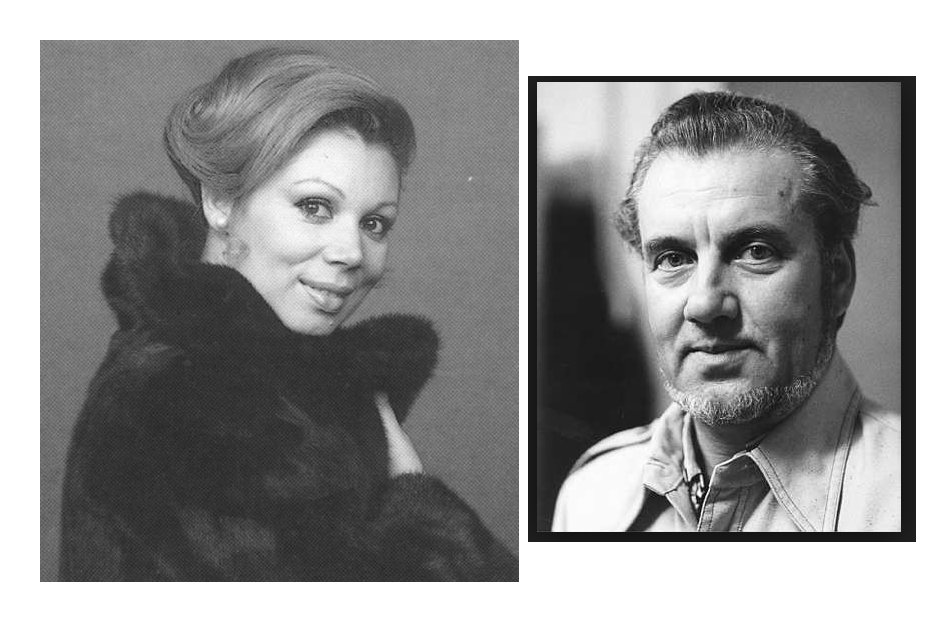

Soprano Mirella Freni

and

Bass Nicolai Ghiaurov

Two conversations with Bruce Duffie

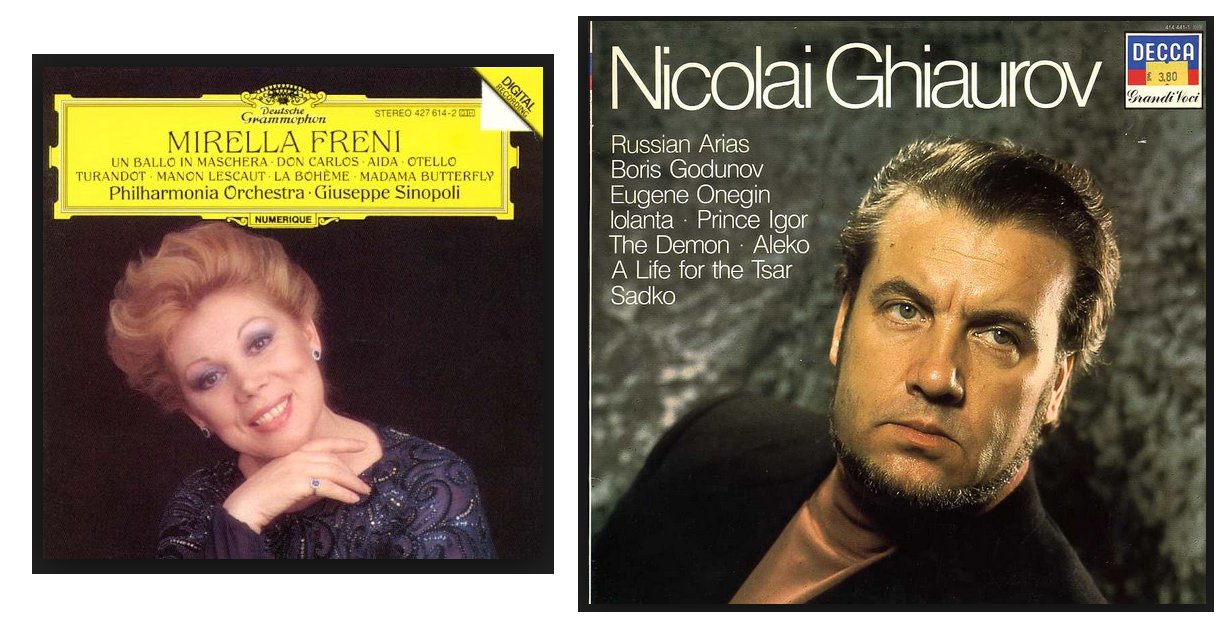

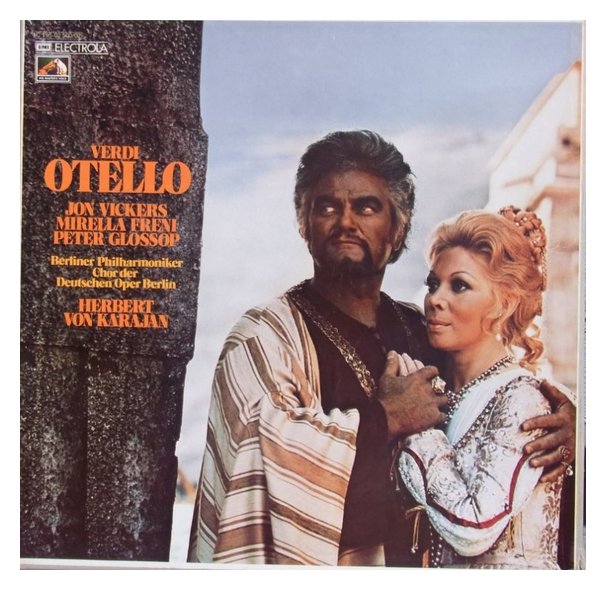

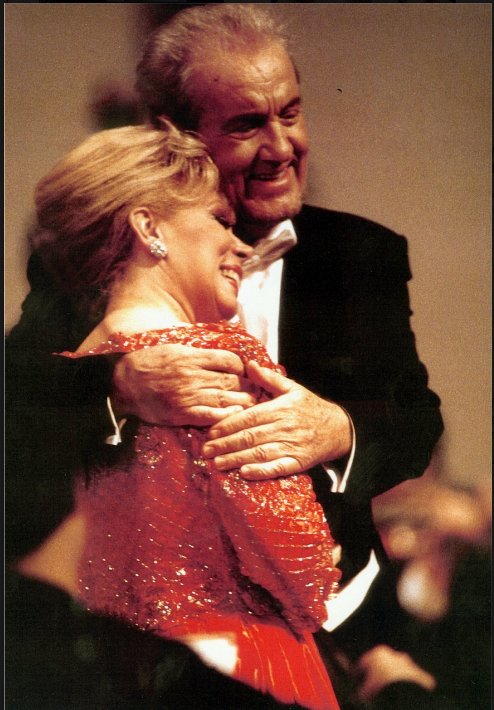

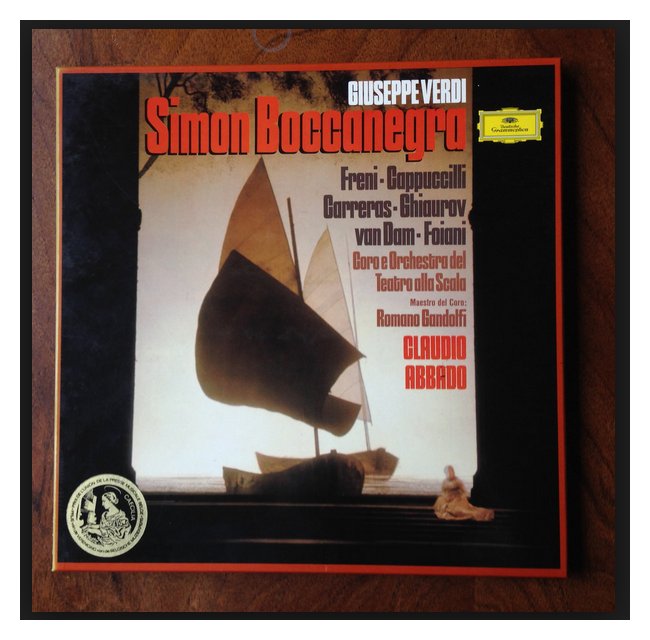

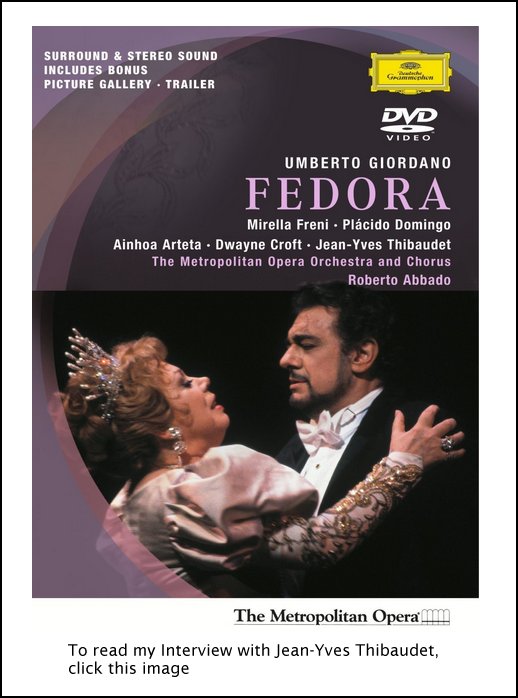

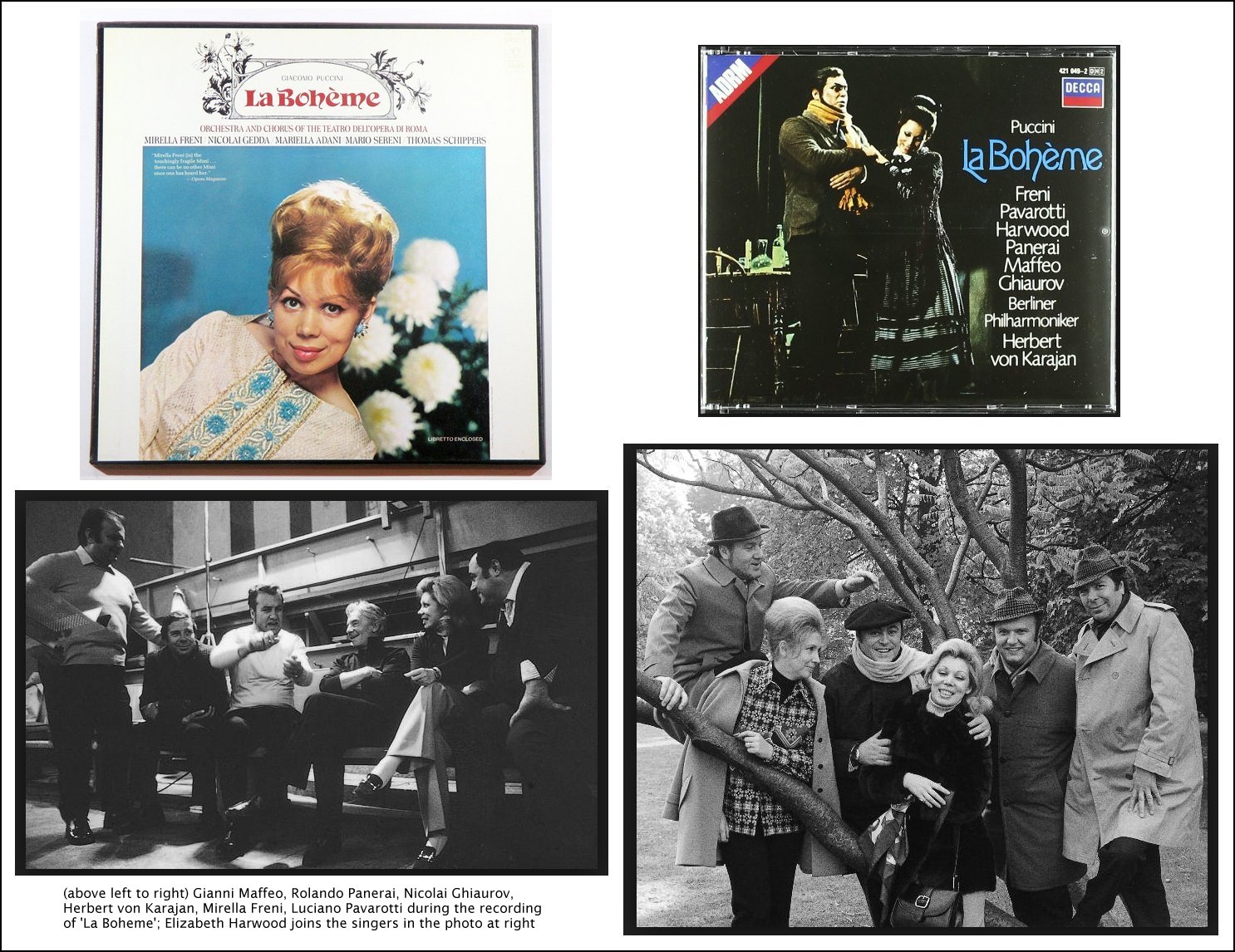

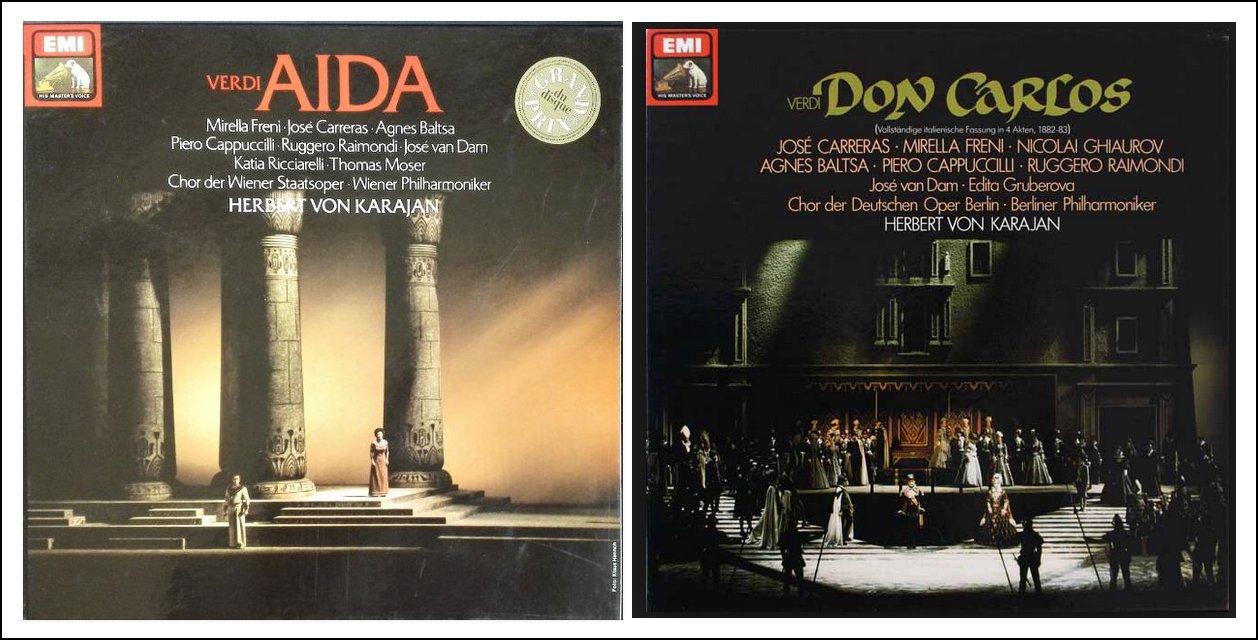

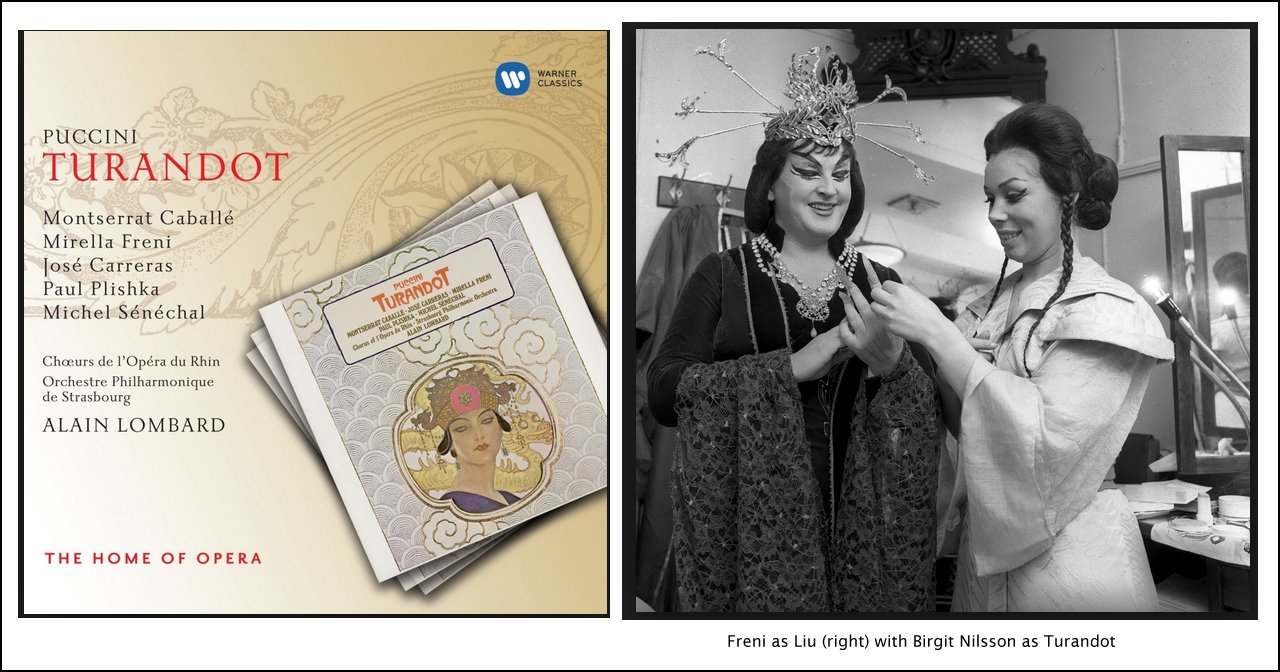

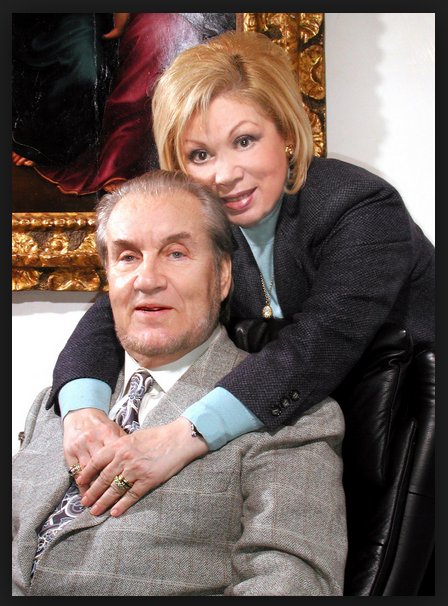

Mirella Freni, born Mirella Fregni on 27 February 1935, is an Italian opera soprano whose repertoire includes Verdi, Puccini, Mozart and Tchaikovsky. Freni was married for many years to the Bulgarian bass Nicolai Ghiaurov, with whom she performed and recorded. Freni was born into a working-class family in Modena; her mother and tenor Luciano Pavarotti's mother worked together and an aunt was the soprano Valentina Bartolomasi. [Freni and Pavarotti would later perform and record together many times.] She was a musically gifted child, and when 10 years old sang "Un bel dì vedremo" in a radio competition. Tenor Beniamino Gigli warned her, however, that she risked ruining her voice and advised her to give up singing until she was older. She resumed singing at the age of 17. Freni made her professional debut as Micaëla in Carmen in 1955 in her hometown of Modena and, over the following several seasons, sang at most of the leading Italian opera houses. She made her La Scala debut in 1963 as Nanetta in Falstaff and the following year. She achieved immediate international stardom there when she was cast by Herbert von Karajan as Mimì in a new production of La Bohème staged by Franco Zefferelli. Within a short period of time, guest appearances took Ms. Freni to the world’s most important opera houses, including the Vienna State Opera, where the prestigious title “Kammersängerin” was conferred upon her by the Austrian Government. In North America, the soprano made her Metropolitan Opera debut in 1965. On that occasion, as on the occasions of debuts in San Francisco, Chicago, Houston, Philadelphia and Miami, the role of Mimì served as her calling card. In 1970, Ms. Freni began a judicious transition from the purely lyric repertory to that of certain spinto roles. She starred with Jon Vickers and Peter Glossop in a new production of Otello at the Salzburg Festival. The conductor was Maestro von Karajan who, perhaps more than anyone, had a profound influence on her career. Other conductors with whom the soprano has enjoyed extended collaborations include Claudio Abbado, Roberto Abbado, Carlo Maria Giulini, Carlos Kleiber, George Prêtre, James Levine, Riccardo Muti, Seiji Ozawa and Giuseppe Sinopoli. During the ‘70’s and ‘80’s, Mirella Freni continued to expand her repertory by undertaking major Verdi, Puccini and Russian operas, e.g. Don Carlo, Aïda, Ernani, Manon Lescaut, Eugene Onegin and Pique Dame. In recent seasons, she has explored the verismo repertory, adding the title roles of Adriana Lecouvrer, Fedora, Madame Sans-Gêne, and The Maid of Orleans. Many of Ms. Freni’s distinguished video performances from the Metropolitan Opera, La Scala, Paris Opera and the Vienna State Opera are currently released on DVD. -- Names which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD Freni made her professional debut as Micaëla in Carmen in 1955 in her hometown of Modena and, over the following several seasons, sang at most of the leading Italian opera houses. She made her La Scala debut in 1963 as Nanetta in Falstaff and the following year. She achieved immediate international stardom there when she was cast by Herbert von Karajan as Mimì in a new production of La Bohème staged by Franco Zefferelli. Within a short period of time, guest appearances took Ms. Freni to the world’s most important opera houses, including the Vienna State Opera, where the prestigious title “Kammersängerin” was conferred upon her by the Austrian Government. In North America, the soprano made her Metropolitan Opera debut in 1965. On that occasion, as on the occasions of debuts in San Francisco, Chicago, Houston, Philadelphia and Miami, the role of Mimì served as her calling card. In 1970, Ms. Freni began a judicious transition from the purely lyric repertory to that of certain spinto roles. She starred with Jon Vickers and Peter Glossop in a new production of Otello at the Salzburg Festival. The conductor was Maestro von Karajan who, perhaps more than anyone, had a profound influence on her career. Other conductors with whom the soprano has enjoyed extended collaborations include Claudio Abbado, Roberto Abbado, Carlo Maria Giulini, Carlos Kleiber, George Prêtre, James Levine, Riccardo Muti, Seiji Ozawa and Giuseppe Sinopoli. During the ‘70’s and ‘80’s, Mirella Freni continued to expand her repertory by undertaking major Verdi, Puccini and Russian operas, e.g. Don Carlo, Aïda, Ernani, Manon Lescaut, Eugene Onegin and Pique Dame. In recent seasons, she has explored the verismo repertory, adding the title roles of Adriana Lecouvrer, Fedora, Madame Sans-Gêne, and The Maid of Orleans. Many of Ms. Freni’s distinguished video performances from the Metropolitan Opera, La Scala, Paris Opera and the Vienna State Opera are currently released on DVD. -- Names which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

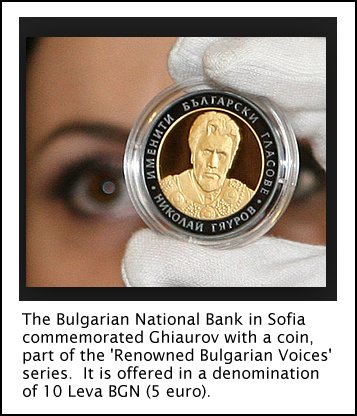

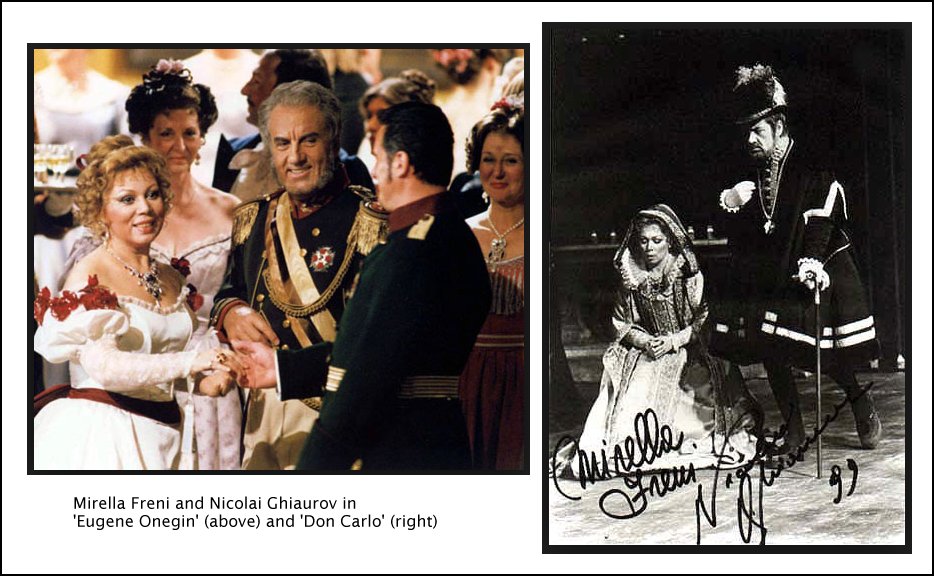

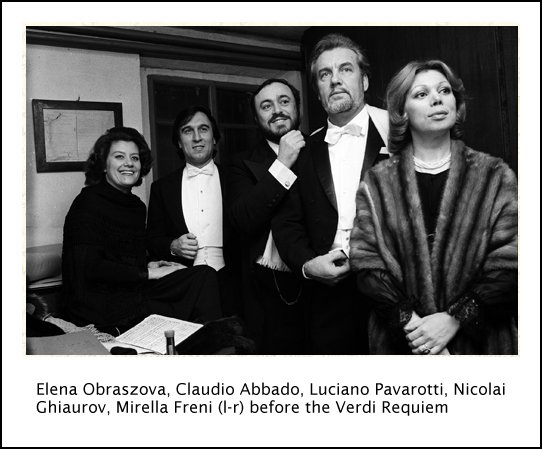

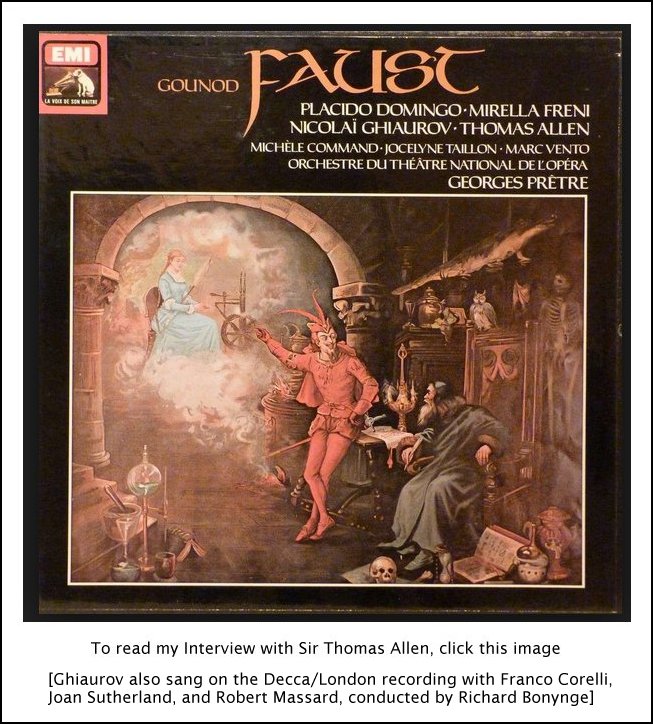

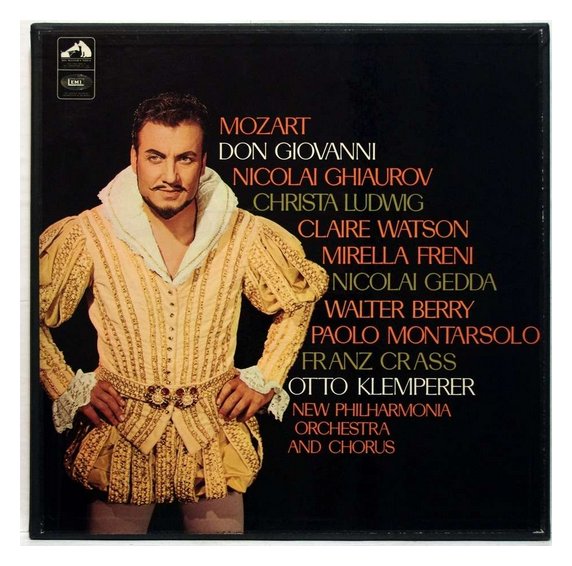

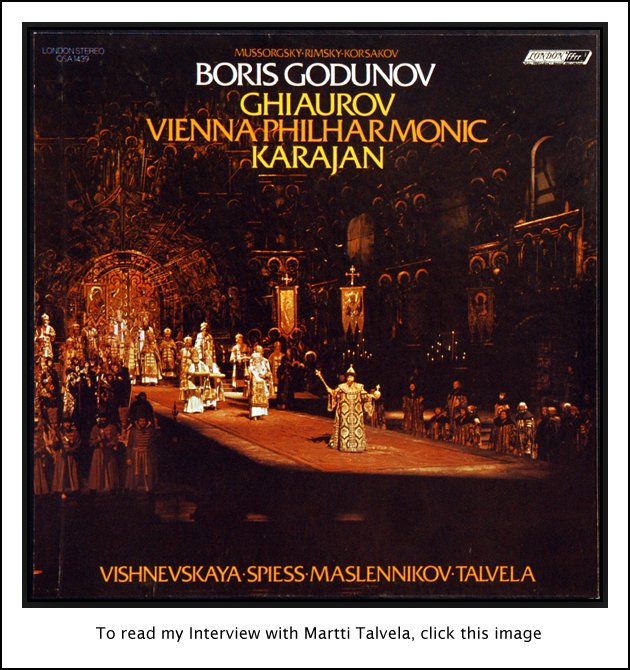

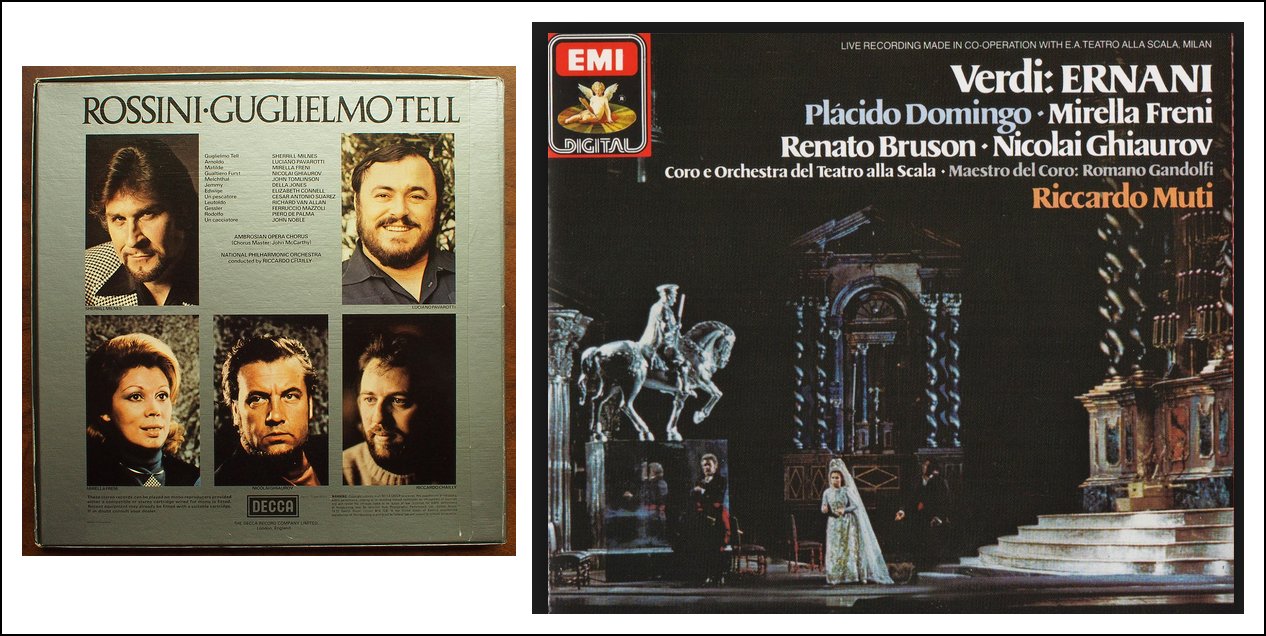

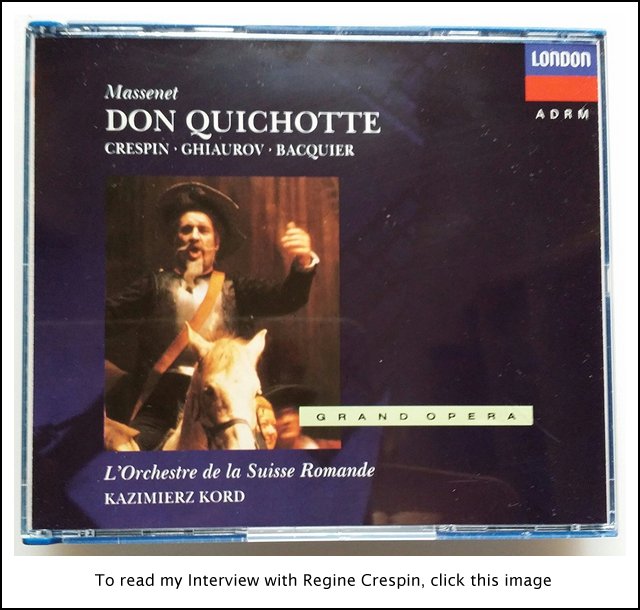

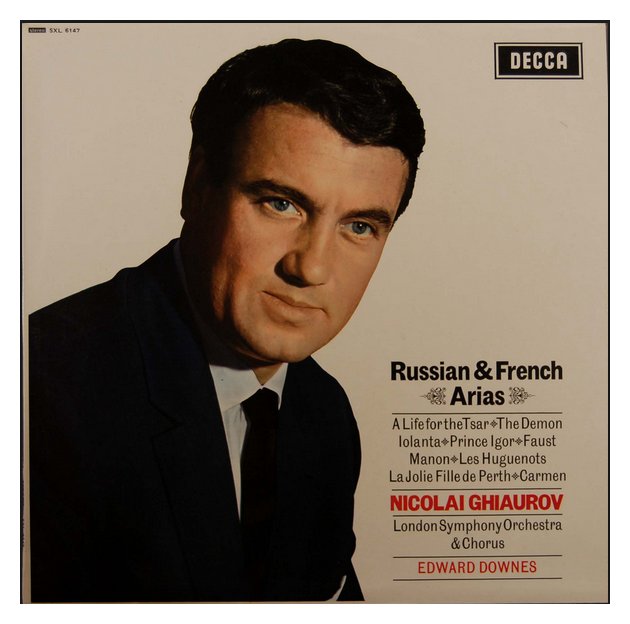

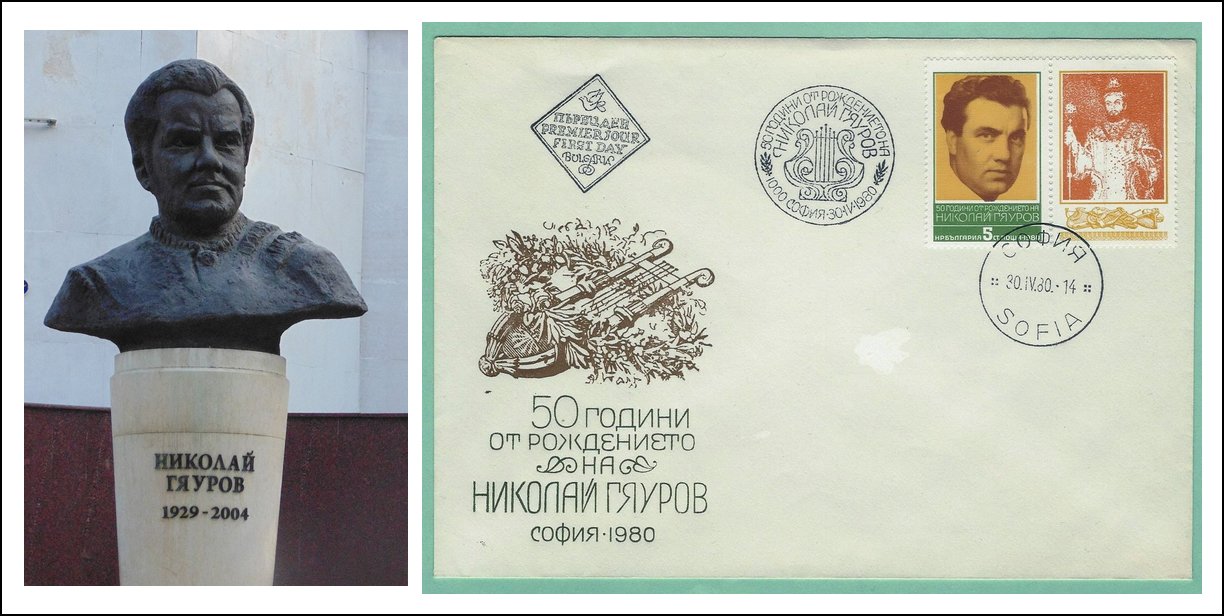

Nicolai Ghiaurov (or Nikolai Gjaurov, Nikolay Gyaurov, Bulgarian: Николай Гяуров) (September 13, 1929 – June 2, 2004) was a Bulgarian opera singer and one of the most famous basses of the postwar period. He was admired for his powerful, sumptuous voice, and was particularly associated with roles of Mussorgsky and Verdi. Ghiaurov married the Bulgarian pianist Zlatina Mishakova in 1956 and Italian soprano Mirella Freni in 1978, and the two singers frequently performed together. They lived in Modena until Ghiaurov's death in 2004 of a heart attack. Ghiaurov was born in the small mountain town of Velingrad in southern Bulgaria. As a child, he learned to play the violin, piano and clarinet. He began his musical studies at the Bulgarian State Conservatory in 1949 under Prof. Hristo Brambarov. From 1950 until 1955, he studied at the Moscow Conservatory. Ghiaurov's career was launched in 1955, when he won the Grand Prix at the International Vocal Competition in Paris and the First Prize and a gold medal at the Fifth World Youth Festival in Prague. He made his operatic debut in 1955 as Don Basilio in Rossini's The Barber of Seville in Sofia. He made his Italian operatic debut in 1957 in Teatro Comunale Bologna, before starting an international career with his rendition of Varlaam in the opera Boris Godunov at La Scala in 1959. 1962 marked Ghiaurov's Covent Garden debut as Padre Guardiano in Verdi's La forza del destino as well as his first appearance in Salzburg in Verdi's Requiem, conducted by Herbert von Karajan. Ghiaurov first shared a stage with Mirella Freni in 1961 in Genoa. She was Marguerite, he was Mefisto in Faust. Married in 1978, they lived in her hometown, Modena. They sang together frequently. He made his US debut in Gounod's Faust in 1963 at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, and he went on to sing twelve roles with the company, including the title roles in Boris Godunov, Don Quichotte, and Mefistofele. Ghiaurov made his Metropolitan Opera debut on 8 November 1965 as Mephistofele. He sang a total of 81 performances in ten roles there, last appearing there on October 26, 1996, as Sparafucile in Rigoletto. During the course of his career, he also performed at Moscow's Bolshoi Theatre, the Vienna State Opera, Covent Garden, and Paris Opéra. He recorded frequently, and his discography includes complete recordings of many of his great stage roles. Ghiaurov was born in the small mountain town of Velingrad in southern Bulgaria. As a child, he learned to play the violin, piano and clarinet. He began his musical studies at the Bulgarian State Conservatory in 1949 under Prof. Hristo Brambarov. From 1950 until 1955, he studied at the Moscow Conservatory. Ghiaurov's career was launched in 1955, when he won the Grand Prix at the International Vocal Competition in Paris and the First Prize and a gold medal at the Fifth World Youth Festival in Prague. He made his operatic debut in 1955 as Don Basilio in Rossini's The Barber of Seville in Sofia. He made his Italian operatic debut in 1957 in Teatro Comunale Bologna, before starting an international career with his rendition of Varlaam in the opera Boris Godunov at La Scala in 1959. 1962 marked Ghiaurov's Covent Garden debut as Padre Guardiano in Verdi's La forza del destino as well as his first appearance in Salzburg in Verdi's Requiem, conducted by Herbert von Karajan. Ghiaurov first shared a stage with Mirella Freni in 1961 in Genoa. She was Marguerite, he was Mefisto in Faust. Married in 1978, they lived in her hometown, Modena. They sang together frequently. He made his US debut in Gounod's Faust in 1963 at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, and he went on to sing twelve roles with the company, including the title roles in Boris Godunov, Don Quichotte, and Mefistofele. Ghiaurov made his Metropolitan Opera debut on 8 November 1965 as Mephistofele. He sang a total of 81 performances in ten roles there, last appearing there on October 26, 1996, as Sparafucile in Rigoletto. During the course of his career, he also performed at Moscow's Bolshoi Theatre, the Vienna State Opera, Covent Garden, and Paris Opéra. He recorded frequently, and his discography includes complete recordings of many of his great stage roles. |

|---|---|

|

It was only on rare occasions that I had the opportunity to interview a couple.

Besides the two featured on this webpage, other partnerships included Dame Joan Sutherland and Richard Bonynge, Stafford Dean and Anne Howells, Fiorenza Cossotto and Ivo Vinco, John Shirley-Quirk and Sara Watkins, and twice, as is the case here, with Léopold Simoneau and Pierrette Alarie. Another duo, though not a couple as the others, was Sir John Pritchard and Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, and one other famous couple, Evelyn Lear and Thomas Stewart, were both interviewed, but at separate times.

Like those just listed, Mirella Freni and Nicolai Ghiaurov both had stunning individual careers, and they were able to sing together on many occasions — which they both agreed was the preferable situation. However, this was not always the case. When they appeared in Chicago in the same season, they almost always appeared in different productions during the same time period, and that made arranging a mutually convenient time much more tricky. In December of 1981 and November of 1994 we were able to get together, and this webpage presents both conversations.

The first interview originally appeared in Nit&Wit Magazine, and segments from both chats were used on WNIB several times when we played their recordings. Mme. Freni spoke in English

— which was quite good, by the way — and Sig. Ghiaurov went through a translator. My thanks to Marina Vecci or Lyric Opera of Chicago for rendering my thoughts to him and presenting his responses to me in both of the interviews.

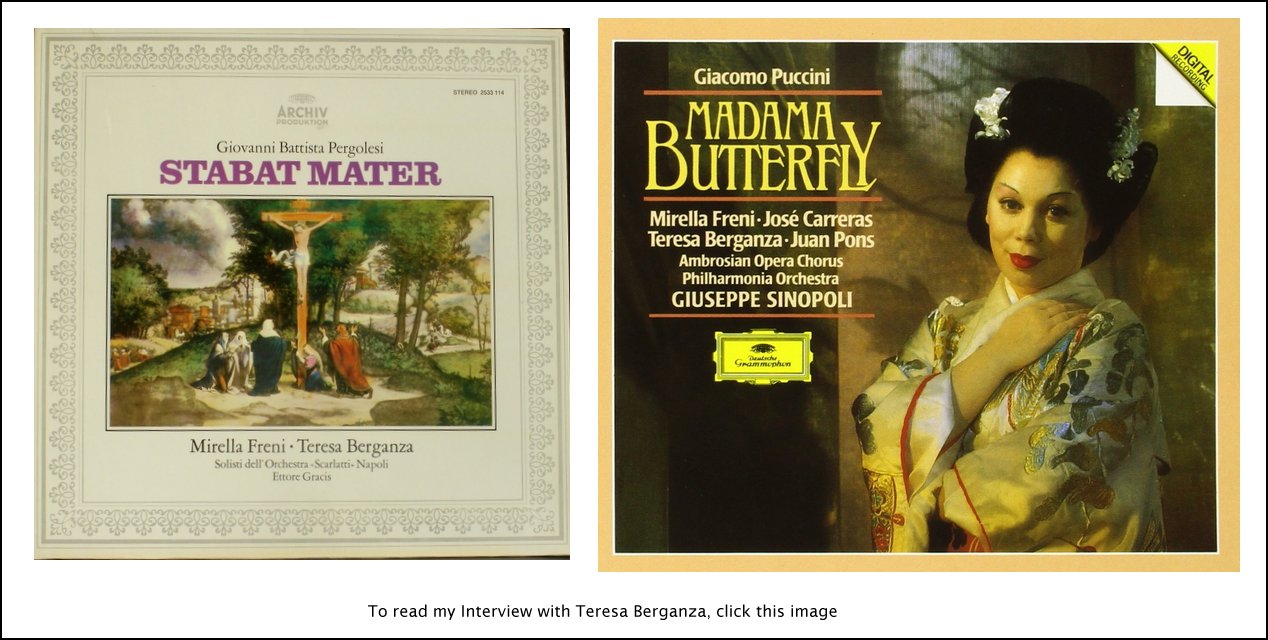

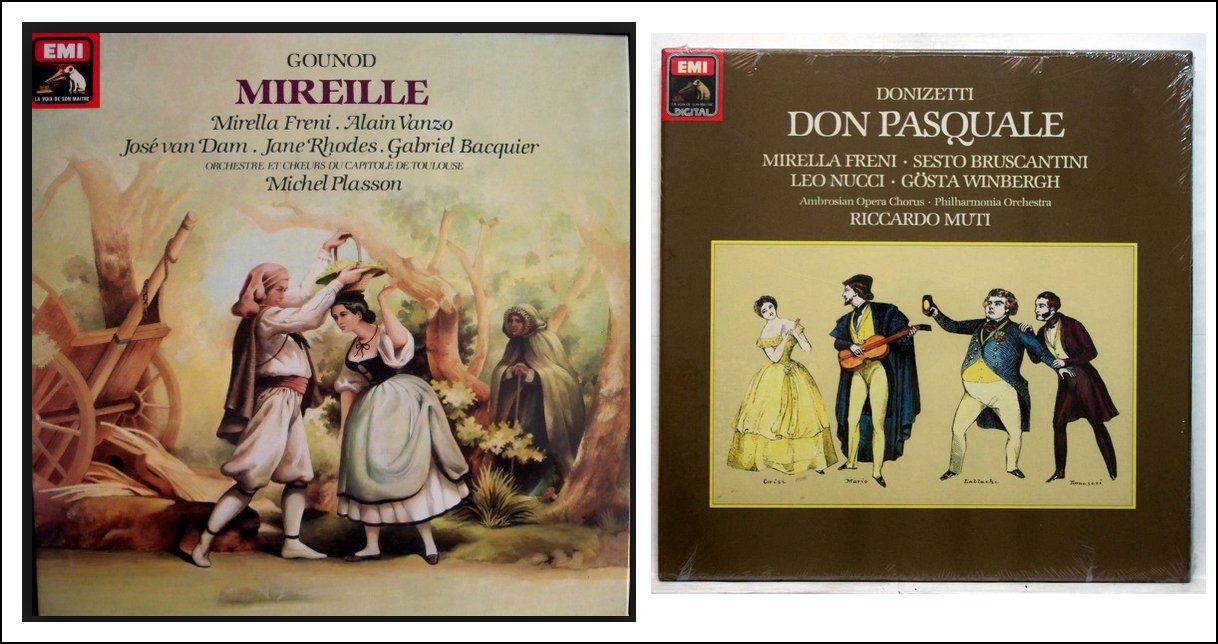

I presented some questions for each artist, and some for both together, and I tried very hard not to favor one over the other. Amidst the smiles and laughter there were many serious moments, and in the end everyone seemed very pleased with each encounter. Both artists made many recordings separately and together, and I have included images of a few of them to illustrate the roles being discussed, or simply to show the photographs on the record jackets. Remember those?

As we sat down to begin, we all agreed it had been difficult to find a time amongst all the performances and rehearsals of the two operas . . . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Do you find it a happy experience when you perform with Signor Ghiaurov?

Mirella Freni: Oh, yes!

BD: Happier than when you’re performing apart?

Freni: It’s the same, but I like it better when we are together, especially when we are in Milan. I especially prefer to sing in the same opera because, like now when we’re in two different operas, we are never free together.

BD: You both have worked a lot with Herbert von Karajan. Do you find his operas are more unified because he is both conductor and producer?

Freni: For me, he is more than just a great conductor. He has something special.

BD: Is he a better conductor than producer?

Freni: I think so, but perhaps he won’t like me to say so. [Laughs] For me he is an incredible conductor. There is no comparison with the others.

Freni: I think so, but perhaps he won’t like me to say so. [Laughs] For me he is an incredible conductor. There is no comparison with the others.

Nicolai Ghiaurov: I’ve been working with him since 1961 in Salzburg with the Verdi Requiem, but then my big break was when he asked me to do Boris in 1965.

BD: You mention the Requiem. Is that another opera by Verdi?

Ghiaurov: It is, of course, done in concert, but the operatic hand of Verdi is so clear that we could almost say it was another opera. Therefore it is more difficult for the interpreters because they have to bring to it this enormous operatic sonority rather than a concert-like sonority.

Freni: But at the same time you need the right line like a concert, so it’s not easy. For me this piece is really fantastic, incredible.

BD: Do you ever do operas in concert?

Freni: I have done some many years ago, but not now.

BD: Do they work?

Freni: Yes, why not?

BD: I was wondering how much of the drama was lost.

Freni: In this way you can hear some lines that are lost when the operas are staged because you’re not running or turning. In concert, you hear something different sometimes, and I like doing them.

Ghiaurov: A concert version of an opera is for a musically more prepared and advanced audience. It needs an audience that can imagine what is lacking in scenic terms.

BD: Is that the same kind of idea needed for recordings?

Ghiaurov: Yes, it’s the same thing because the audience cannot see what is happening without the stage or without a TV screen to look at. So it’s left to the fantasy of the imagination. It’s probably very difficult for the record audiences to realize how difficult it is for the singer or interpreter of the piece to concentrate and sing the character and build a character in the midst of all this technical equipment

— mikes, wires, cables, and such.

Freni: But after many years, you are ‘diprotic’. [Laughter all around]

BD: Do you enjoy making records?

Freni: Yes, I like doing it.

BD: Let me ask you about Bohème. Is that a special role for you?

Freni: Yes, it was really important for me. I did the very important and beautiful production at La Scala in 1963 with Karajan and Zeffirelli, and all the world speaks about this production and Mirella Freni as Mimì. I’m very happy because I’m still singing in this way. I’ve just done it in Houston and received a lot of praise in the news magazine. For me it’s very important because I like this role, and I repeated it in my career. But I love so many others. I’m not only Mimì. Every role that I’ve sung I’ve loved very much. Every role is something of mine and has a small place in my heart. They are all like my little babies, so I don’t prefer one, really.

BD: Are there any roles that you sing where you don’t like the character?

Freni: No, because if I don’t like it, I don’t sing it. I don’t accept. When I say yes, it’s because I like it.

BD: Is it difficult for you as a singer to say no?

Freni: At the beginning of a career you must do things in a diplomatic way, and if you say no, you’ll stay at home and cook. But now it’s not so difficult because I know very well what I want and what is good for me. But I was strong enough at the beginning of my career, and I’ve said no many times. This is very important because you must save your instrument.

BD: Are there roles you once said no to, that you now accept?

BD: Are there roles you once said no to, that you now accept?

Freni: Yes, for example, I always said no to Butterfly. Now I’ve done the record and the movie, but I still say no to requests for stage performances because it’s very dangerous for the voice.

BD: Signor Ghiaurov, are there roles you don’t like? Do you like portraying the Devil?

Ghiaurov: All my roles are bad guys! I don’t play nice people. They are either men who have betrayed their wives, or they’re evil.

Freni: Oh, no, Don Quichotte is a wonderful man!

Ghiaurov: In my voice category, I don’t have the choice that the sopranos or the tenors have. If someone would ask me to do Micaëla, I would do it. [Laughter]

Freni: Why not? Coloratura is more fun. [Freni made three commercial recordings of Micaëla: Price/Karajan, Bumbry/Frübeck de Burgos, Norman/Ozawa.]

Ghiaurov: All the bass roles are very hard to interpret because you have to enter into the flesh and blood of the character in order to convince the public.

BD: How do you get into the flesh and blood of the Devil?

Freni: Perhaps he has a little of the Devil in him! [Laughter]

Ghiaurov: The world is full of devils, so I have a lot of models.

BD: Is there a difference in doing the Gounod and the Boito?

Ghiaurov: In the Boito, the character is much closer to the literary characters, so it is different from the Gounod. Musically, Boito is much stronger, and more hellish and evil. The Gounod Devil is like a secret agent that has been sent to the earth like an elegant spy. He is not as bad a guy as Boito.

BD: In Don Carlo, is Philip II an evil man, or is he just betrayed?

Ghiaurov: In history, they attribute a lot of bad deeds to Philip, but in the opera he is a man who is lonely, betrayed and abandoned. He is a very sad, very human character.

BD: Would Elisabeth have been happy with Philip if she’d not met Carlo?

Freni: In the story it’s not possible. In my mind, she never forgets Carlo. She’s so honest and has such a sense of duty.

Ghiaurov: But Mirella, when you sing with me you are very happy.

BD: Let’s discussOtello. How pure is Desdemona?

Freni: For me, she simply doesn’t see bad things. When she talks incessantly about Cassio, it’s for the simple reason, and she doesn’t know there’s someone behind her pushing. She loves Otello so much, and she is completely honest. For this reason, you must find out completely about the character of Desdemona. She is really pure. She’s not stupid but a bit too trusting.

BD: Is she confident?

BD: Is she confident?

Freni: Yes, surely.

BD: Let me ask about different sized houses. Does it affect your voice to sing in a smaller house or a bigger house?

Freni: You must sing in the same way. If you start to change your vocal production, you can strangle the voice. Naturally, if the house is smaller, you can hear me better.

Ghiaurov: All the theaters are too large! [Laughter all around] Actually I enjoy singing in a smaller theater more, but I like the big theaters also.

BD: How much does the scenery affect your interpretation of a part?

Freni: I arrive at the first rehearsal with my interpretation already figured out. My personality is there, but naturally, during the rehearsals you can change things to find accord with the producer and the conductor. You must be flexible, but the idea must be very clear.

BD: How much flexibility do you have, and how much do you let the producer pull your interpretation?

Freni: This depends. It’s like in life. When you meet someone who is sympathetic, you can be infinitely flexible. But if it’s not really a good idea that the producer wants, you can back off a bit.

Ghiaurov: There are very few producers who are capable of doing really great things on the stage, and the decor can help a lot in the production. The great directors, like Strehler, can certainly give you very good hints about your character that you’re supposed to interpret because they know so much about the opera that they are staging. But there are very few.

Freni: It’s very difficult to explain. It’s very important to have the decor, and sometimes even the costumes can help. If you feel well when you look in the mirror, you become the character. The sensation is there, and it’s very important. Here, when I first saw the costume for Juliette, I was very happy with it, and I become Juliette. So very many things are important. You must look like the role you are singing.

BD: Do you enjoy becoming all these very different characters?

Freni: I like it when I can change. I cannot stay always the same way; it would be really boring.

BD: I would think that the soprano would find it easier to change characters than the bass who is always evil.

Ghiaurov: As I see it, the characters Mirella sings are usually the same, and are similar types of characters.

Freni: No, it’s not true! Desdemona is different. Desdemona is not Mimì. Mimì is not Juliette. Juliette is not Aïda. It’s really quite difficult because you must change each time.

Ghiaurov: But they are all lovers and mistresses

— all positive characters. The bass, on the other hand, has such very diverse roles as Basilio, Philip, Boris Godunov, Don Giovanni. You see, the range is much larger.

BD: More possibilities?

BD: More possibilities?

Ghiaurov: Certainly.

Freni: Even though they may be closer characters, it’s much more difficult to make the people perceive the differences between them when they are on the same line.

BD: The differences are more subtle?

Freni: Yes, exactly.

Ghiaurov: I agree with that

— they are more subtle.

BD: Where is opera going today? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my Interviews with Walter Berry and Paolo Montarsolo.]

Freni: The theater is always full — not only here in America, but in Europe, also. The problem — and it’s true all over — is money. I do see a lot of possibilities. There are many audiences of people who would love to see beautifully staged works, and the technical possibilities are available. But on the other hand there are fewer very good singers, and there is not that much money going around to put into the productions.

BD: Are there really fewer good singers today than there were maybe fifteen years ago?

Freni: Yes.

BD: Why?

Freni: I don’t know.

BD: It seems like we have so many students learning today.

Freni: Yes, it’s true, but before they can come out they must take time to learn. Think of basses and try to think of those who are world-class today. It is the same for baritones and sopranos, and all the rest. I speak about the whole world. This is the problem. So if you have a big production in La Scala, another at the Met, and another in Chicago, and all use the best singers, what happens to the rest of the world’s theaters? Perhaps there are some students coming along, but it takes time to develop an operatic voice. It’s so very difficult now because when a theater finds a good soprano or tenor, they take them and give them too much to sing, and they burn out the voice very quickly. They don’t save their voices for the future. This might be one reason for the shortage of great singers today.

[At this point, Mme. Freni had to leave for another appointment, but

Sig. Ghiaurov graciously agreed to remain for a few more minutes.]

Ghiaurov: To respond to your question about where opera is going, it’s true that on the one hand there are few great singers today, but on the other hand you have a lot more interest towards theater and towards opera nowadays. So you have a lot of theaters doing a lot of operas every night. There are always curtains going up on different productions. Therefore, there are many singers who have worked and studied who go on stage and sing. And there’s more interest fostered by the new technology. That’s especially true in Japan where all the homes have all the latest hi-fi systems. So great passion is born for opera and classical music.

BD: So the recording industry helps to foster the arts in a way?

Ghiaurov: Yes, and also the TV. The public gets to see them and learn what opera is all about. Before, opera was a very limited art, and was accessible only to those who had money to buy seats in theater. So this presents problems for singers

— all of whom are grabbed by the theaters and offered money in a quick way. There are very few singers who devote the time that is necessary to build up a career in the service of music. I myself studied for seven years before singing a role. It was just study and preparation. Today it seems to me that there are very few singers who are ready to go through the same thing with such long preparation.  BD: Are we losing the tradition?

BD: Are we losing the tradition?

Ghiaurov: It is necessary to find the balance between the singers that devote the time to preparation and study, and the public that will demand a certain level of performers. Otherwise, when you have a mediocre production, it becomes the most boring thing that you can see.

BD: Jon Vickers told me that there was this ascent of mediocrity.

Ghiaurov: There are very few people who are ready to dedicate themselves to serve art as apostles.

BD: How is the music of Verdi different from that of Mussorgsky?

Ghiaurov: It’s a different style, just as Stravinsky is different from Brahms. Gounod and Bizet are from the French school, but they have a totally different style.

BD: Do you enjoy singing early works? You did Poppea by Monteverdi.

Ghiaurov: It was a very useful experience for me because I felt I went back to the foot of ‘bel canto’ by doing Poppea.

BD: Are there any modern operas that you enjoy?

Ghiaurov: I would like to find something that is interesting for my voice. At one time, Pendereckidid discuss the possibility of writing an opera on the subject of Ivan the Terrible. So far, though, I haven’t come across any operas with a character as interesting as Boris. At one time, composers did write operas and roles for certain singers, plus they had a very good understanding of what the vocal possibilities of a singer were.

BD: Do composers today not understand the voice?

Ghiaurov: The sonority is sometimes outside the human possibilities of the voice. Perhaps their own concepts of the sonorities sound very well, but for the voice they are hard to achieve. The evolution of a man’s body has occurred through millions of years, or perhaps just a hundred years, or five hundred years, but the voice has not changed that much in that time. The voice is an instrument guided by the most delicate system, the nervous system, and it’s not something that can be tampered with like a piano or violin. It would be great to be able to tune it or fix it when it breaks down. That’s why in the difficult roles I have to start practically from the beginning every day preparing and getting my voice in shape.

BD: One question about Boris. Is there a time when you would sing both Boris and Pimen in the same performance?

Ghiaurov: I don’t really agree with that concept. It’s really a trick rather than a concept. I was asked to sing all three roles for the record, but I declined. Mr. Christoff did it, and a critic remarked that he was surprised that he didn’t also do the chorus part! [Laughter all around]

BD: Will you be back in Chicago?

Ghiaurov: Not next year but after that. This is ‘my’ American city! Even though the audience here is not very demonstrative, I feel that I am liked here, and that the audience takes something home with them when they leave the theater.

BD: We may not be as demonstrative as others, but we have as much love. Mille grazie.

Ghiaurov: It was a pleasure. Thank you.

|

Mirella Freni and Nicolai Ghiaurov at Lyric Opera of Chicago1963 - [American Debut] Faust (Ghiaurov as Mefistofélès) with Guiot, Chauvet, Massard; Dervaux, Gilles 1964 - Don Carlo (Ghiaurov as Philip II) with Gencer, Tucker, Gobbi,Bumbry/Cossotto, Marangoni; Bartoletti Don Giovanni (Ghiaurov as Giovanni) with Stich-Randall, Curtin, Kunz, Kraus, Panni,Uppman; Krips Zeffirelli (prod) 1965 - [Opening Night] Mefistofele (Ghiaurov as Mefistofele) with Tebaldi, Kraus, Suliotis; Sanzogno Bohème (Freni as Mimì) with Corelli, Bruscantini, Martelli, Cesari; Cillario 1966 - [Opening Night] Boris Godunov (Ghiaurov as Boris) with Baldani, Cossutta, Wildermann, Paunov, Haywood; Bartoletti, Benois (prod) Pearl Fishers (Ghiaurov as Nourabad) with Eda-Pierre, Kraus, Bruscantini; Fournet 1969 - [Opening Night] Khovanshchina (Ghiaurov as Khovansky) with Baldani, Shtokolov, Mittelmann, Andreolli, Bodurov; Bartoletti, Benois 1971 - Don Carlo (Ghiaurov as Philip II) with Lorengar, Cossutta, Milnes, Cossotto, Sotin, Estes; Bartoletti, Mansouri 1974 - Don Quichotte (Ghiaurov as Quichotte) with Cortez, Foldi, Paige; Fournet, Tajo, Samaritani 1976 - Khovanshchina (Ghiaurov as Khovansky) with Shade, Lagger,Trussel, Cortez, Mittelmann, Andreolli; Bartoletti, Benois 1979 - Faust (Freni as Marguerite & Ghiaurov as Mefistofélès) with Kraus, Stilwell,Decker; Prêtre, Tallchief (Ballet) 1980 - [Opening Night] Boris Godunov (Ghiaurov as Boris) with Baldani, Ochman, Sotin, Trussel, Tyl, Gordon,Cook, Raftery; Bartoletti, Everding, Lee (prod) Attila (Ghiaurov as Attila) with Cruz-Romo, Luchetti, Carroli; Bartoletti 1981 - Don Quichotte (Ghiaurov as Quichotte) with Valentini-Terrani,Gramm, Gordon; Fournet, Samaritani (director & designer) Romeo and Juliette (Freni as Juliette) with Kraus, Raftery, Kavrakos, Bruscantini, Negrini, Graham; Fournet 1984 - [Opening Night] Eugene Onegin (Freni as Tatiana & Ghiaurov as Gremin) with Brendel, Dvorský, Walker, Doss, Kraft; Bartoletti, Samaritani Ernani (Ghiaurov as Silva) with Bumbry, Bartolini, Cappuccilli; Renzetti 1994-95 - Fedora (Freni as Fedora) with Domingo/Cura, Summers, Lawrence; Bartoletti Barber of Seville (Ghiaurov as Basilio) with Von Stade, Allen, Blake, Desderi; Rizzi, Copley,Conklin 1997-98 - Bohème (Freni as Mimì & Ghiaurov as Colline) with La Scola, Josephson, Rambaldi; Bartoletti, Pizzi (Prod) |

|---|

As can be seen in the chart above, both artists did return to Chicago three more times.

We now move ahead almost thirteen years for our second conversation in November of 1994.

BD: First, a question for both of you. Over your career, you have been offered many, many roles. How do you decide which roles you’ll accept and which roles you’ll turn aside, and has this changed over the course of your career?

Freni: No, not really. When you start to sing, they ask for roles you can really sing, but sometimes they ask for very, very heavy roles. I remember I was only twenty-two years old, and they asked me in Italy to sing Butterfly. I said you are crazy [laughs] because if you want to sing Butterfly, you need something different. For me it’s important that the tessitura is right for me. I can sing and I can support because I have now the technical maturity and the experience. But it doesn’t mean you can sing anything. I take very great care for the tessitura. I don’t force my voice or my body. This is the only way. Naturally I must love the music and the role, otherwise I say no.

Ghiaurov: My career started up very strongly. They asked me immediately for very important roles and big roles.

Freni: But Nicolai has a very great voice, a big incredible voice. I was the opposite. [Giggles]

See my Interviews with Sir John Tomlinson, and Riccardo Chailly

Ghiaurov: I started at La Scala. Immediately La Scala wanted me to sing, and I had my début in the big roles of my repertoire there. I have debuted all my big roles at La Scala.

BD: Is that good to make the debut in the large theater, in the large hall?

Ghiaurov: This if course was against the tradition because usually artists start off in small theaters, and then they go to the big theater, whereas I started in the big ones. I started like a rocket, very fast, as Mephistophele (both Gounod and Boito) and Philip II, and Don Giovanni. It was my decision to wait for Boris for at least ten years after I finished my conservatory studies.

BD: Did you ever feel that you were being asked too much?

Ghiaurov: Yes, immediately they asked me for the big roles, but for me Boris was sacrosanct role, and I didn’t feel like starting it. I was trying to wait to have enough experience

— both scenic and vocal — to start doing Boris. I waited ten years, and it was really the right time — ten years exactly — because I finished the conservatory in 1955, and in ’65 Karajan invited me to do Boris in Salzburg. So I did it just as my plan was.

BD: Is Boris a special role because of the size and the weight of the role, or because it was a Russian role?

Ghiaurov: It is psychologically a very intense role. It’s like having Macbeth and Hamlet all altogether, and perhaps even two Macbeths in the role of Boris.

BD: Did you purposely though seek out the other larger roles for bass, rather than roles where the bass only sings an aria or two?

BD: Did you purposely though seek out the other larger roles for bass, rather than roles where the bass only sings an aria or two?

Ghiaurov: They never accepted me for the small roles because probably I was very expensive. [Laughter all around] They preferred to have me for the large roles, like The Huguenots. They offered me that role which had not been done at La Scala for fifty years, and the same thing in Paris in 1973 with Don Quichotte. They hadn’t done that opera in a while. Chaliapin did it in 1913, and the piece was composed in 1910.

BD: Was it special to bring Don Quichotte to Chicago, where we had such a long history of doing Massenet in the

’20s and ’30s with Mary Garden and Chaliapin and Vanni Marcoux? [See my article, Massenet, Mary Garden, and the Chicago Opera 1910-1932.]

Ghiaurov: I was very happy to do it here just for those reasons, and I was very lucky to do it twice [1974 and 1981].

BD: Many of your roles are fathers and kings. [With a gentle nudge] Would you rather have played characters that got the girl once in awhile?

Ghiaurov: [Smiles] Well, I’ve done Don Giovanni many times, including once with Karajan in Salzburg, and also here. He conquers women, but he never really conquers them at all.

Freni: In the opera, it really is the end of Don Giovanni, because with Donna Anna, no, and he doesn’t want Donna Elvira, and with Zerlina, no. It’s not nice publicity for Don Giovanni! It really is the end for this man.

Ghiaurov: Psychologically I see him in different ways. He never succeeds in any of his conquests in a sense.

BD: We only know him by reputation. [With a gentle nudge to Freni] Is it better for you that he’s not chasing the soprano around the stage so much?

Freni: It’s okay if he’s that way on the stage, but not in the private life! [Much laughter all around] Then it would be different because though I am sweet, I can really be angry. [With mock terror, BD moves his chair slightly away, and there is more laughter]

BD: When you walk on stage, are you portraying a character, or do you become that character?

Freni: It’s difficult to explain because naturally you’ve been this character. You try to find out a bit of something when you prepare her. You study the opera, and you develop her on stage when you work with the producer and the conductor with the others in the cast. I come with my idea of what I must do, but you must be both portraying and becoming her on stage. You have the character in your mind, so you must give it, but always naturally. It’s very important with every role to develop the human being, the truth of this personality in this role, in this person. I really try to match what I can do if finally I have everything in my body that is natural for me on stage. When I feel this, it’s working well.

BD: Is there any character that you play on stage that is perhaps too close to the real Mirella Freni

Freni: Not really. I think I am so strange. [Has a huge laugh] I have in me some of every role I have done. Naturally it’s difficult because each artist can really believe in what she does in this moment. I put off my own character in the role, but not too much. It’s necessary to put your personality more into character. It’s important to have a nice balance together with everything, but when I study the role, there are always the little things they help me to develop her. For example, to discover the personaggio [character, personality] of Mimì, I look at the last part, the last act to help me. There Mimì knows she’s very sick and near to death, but she has a good word for everybody. She always says,

“I’m sorry; I’ve nothing; don’t be worrying about me.” From there you can build the personaggioof the role, the character of Mimì from the beginning and the end. BD: You take the ideas from the ending and use them throughout the portrayal? Freni: Yes. The key was there in the last act for me. Usually it is like that in every role, so I look for this. It is the same for Fedora. A few words help me. It might be just a little thing to develop this woman. In the beginning she’s really a princess. She used to command a bit. When she asked the doctor at the beginning “Please help! You must save my Vladimiro!” It is like a command. But at the end, when she prays to the tenor, to Loris, “Please forgive this woman,” she is a different woman.

BD: You take the ideas from the ending and use them throughout the portrayal? Freni: Yes. The key was there in the last act for me. Usually it is like that in every role, so I look for this. It is the same for Fedora. A few words help me. It might be just a little thing to develop this woman. In the beginning she’s really a princess. She used to command a bit. When she asked the doctor at the beginning “Please help! You must save my Vladimiro!” It is like a command. But at the end, when she prays to the tenor, to Loris, “Please forgive this woman,” she is a different woman.

BD: She’d become more human?

Freni: Yes. Naturally it was the love for Loris. She changes. She’s another woman. It’s really important when you have a score to develop these things and not only to sing. It’s exciting and interesting to take this up, more than just to sing. With my technique I am sure enough, but from the beginning, when I was really young, it was really for me interesting for me to find out what the character was. You can build her like an actor and not only to sing. I can’t just sing.

BD: Then how much of you is singer and how much of you is actress?

Freni: I don’t know. You must say, not me! [Both laugh]

BD: [With a wink] A hundred per cent and hundred per cent!

Freni: [With a big smile] Thank you. You are very kind. We will go to have a coffee, or some lunch! [Much laughter all around]

BD: [Turning to the bass] Signor Ghiaurov, what about portraying and becoming the character?

Ghiaurov: I cannot judge for other voice categories — like tenors and sopranos — what they have to do. Basses are very complicated from the character point of view. I had the good luck of starting off as a theater actor, which was my passion, and also my training. I thought it was going to be my career to be a theater actor, and when I studied at the conservatory, I studied a lot of dramatic art with the Stanislavski method, which is a system that is used in Hollywood a lot. Characters such as Philip II or Boris Godunov are for me a great study of literary material first of all. It is the study of dramatic character. I’m studying the literary text first— Pushkin for Boris, and Schiller for Philip. This is important historical support for what I’m trying to build — the history, the period, the characteristics of the person. Then afterwards it is the musical text. It’s clear to me when Mussorgsky composed Boris Godunov that he took very much into consideration the Pushkin words. The same thing happens for Philip II in Don Carlo. My practical support in my roles is above all in the arias, in which there are more concentrated characteristics of the character, and I take advantage of this. It is not possible to interpret a tyrant, someone like Philip II, when in the opera he expresses an aria like Ella giammai m’amò. He’s such a lonely man, and such an abandoned man. He doesn’t have anyone, and it’s very difficult to portray him as a tyrant. He owns the whole world and yet he’s a lonely man. It’s very hard for me to see him as a killer or as a tyrant. It’s the same thing for Boris Godunov. He adored his children, and he wanted to put his son onto the Czar’s throne as the legitimate Czar because he was not a legitimate Czar himself. He was really driven by this notion of being a killer. He’s a man who died from his remorse, from his conscience. It’s not possible to be a bad Czar, and he cannot be a bad man or a bad Czar. There are no politicians today who die of remorse. [Laughs]

BD: Should there be? [Immediately says to the translator] Don’t ask him that! [Laughter all round, especially from Mme. Freni, who understands the English. Coming back to the topic] Is it part of your responsibility, as an actor and singer, to portray both of these sides of the character?

Ghiaurov: Absolutely. That is my joy as a singer. I try to do that. If I’ve succeeded, I don’t know, but I tried.

BD: You were mentioning Schiller and Pushkin. Do these make better operas when they have the better dramatic texts?

Ghiaurov: It depends, of course. A composer who writes and uses Goethe’s Faust might compose badly, yet where he starts from is very good.

Ghiaurov: It depends, of course. A composer who writes and uses Goethe’s Faust might compose badly, yet where he starts from is very good.

Freni: Yes, I think they can help or perhaps give inspiration to the big composer. They must have a feeling with what they are writing. I say this with humility because I don’t want to put myself close to the big composers, but when I find something that excites me, I think

“Oh, this role, I must do it. I can build something.” and I think for the composer it’s the same. When they read something, they immediately they start to have in the mind the melody, or some idea to build really something important. The big literary works help the big composers.

Ghiaurov: Composers often have started off from good literary works of important writers like Shakespeare. Usually the big works have started off from good literary works.

BD: Coming back to the original question, when you walk on stage, are you portraying that person, or are you becoming that person?

Ghiaurov: I think on average I become the character. The greatest compliment I received for Boris was from a man who saw Chaliapin twenty-five times in performances of this role. This very old man told me that Chaliapin would be unsurpassed in this role, but he explained to me why I am better than Chaliapin. He said it was,

“Because Chaliapin interpreted Boris, whereas you are Boris.”

BD: Is it difficult to become different characters on different nights?

Ghiaurov: Very difficult because it’s always that all my blood has to change and become the blood of another person. Becoming the character is a way of thinking, of suffering, of expressing his feelings. There was a part of my brain that controls me.

Freni: It is the brain that controls all that transformation, and all of this acting.

Ghiaurov: Perhaps what happens is that fifty per cent is controlled, and fifty per cent may become the character.

BD: After all of this you have to project these characters. Does your projection of either the character or the voice change if it’s a small theater or a large theater?

Ghiaurov: It’s very difficult to explain. It a sensation that the singer has which cannot be measured or modified like the volume knob on a radio. Naturally you’ll have to change the production of your voice accordingly. You have always to ride over the orchestra and reach the audience, so you have to gauge that.

Freni: Naturally you spend less energy in a small theater than in a one big. It is easier because the voice comes back to you on the stage, and you are able to control that. In the big theater, it doesn’t happen. Perhaps the feeling is more comfortable in a small theater.

Ghiaurov: There is also the acoustic of each theater to consider.

Freni: Yes, that’s also true because sometimes the small theater is not good enough in a nice acoustic. You believe you have enough voice, but this is the problem sometimes. You must really have a nice control, and don’t start to push. You must give the normal amount in a big theater and a small one, but with a bad acoustic, if you start to force you lose the color of the voice and everything else.

BD: How are the audiences different from Italy to the rest of Europe to the United States?

BD: How are the audiences different from Italy to the rest of Europe to the United States?

Freni: It’s strange to say because now, after many, many years in this profession, I have many, many, many fans. For me it’s difficult to say where is better because, thank God, many fans really love me in every place.

BD: Well, not necessarily better or worse but is it different from place to place?

Freni: Different? It is not different from us. If you are in good form and give some really big emotion, they respond. Once I did a very important concert

— I will not say where — and it was the first time I’d done a recital there. They told me not to be worried if the audience is not too warm because they are very rich. They love it, but they applaud like [looking for English words] too sophisticated. But I was told it’s not because they don’t love it. Usually they do this, so I shouldn’t be worried because it’s the first time I sing there. I thanked them, and the first piece went very well. Then these people screamed,“Bravo, bravo!” and there was a standing ovation. So you see it depended from us also what feeling you find with this audience. Also with the opera, we do many things. When I’m alone or I feel not really good, I don’t arrive to capture them. It could be very nice, but not really a standing ovation. I must say in Vienna, in Salzburg, also in Covent Garden, they are really special. There’s big enthusiasm in Italy, and in Spain. In Barcelona you can’t imagine. They react differently. It’s not because they scream more, but you can feel when you have captured the audience. They are with you. I feel it in my skin, in my body.

BD: Do you give a little more if the audiences has taken you to their hearts?

Freni: This is right. It’s a good question you ask me, but it’s not a matter of giving more. You trust them more when you feel the audience is with you, so perhaps you sing better. Perhaps you give more, but it is more with less tension. You are more relaxed, so sometimes they help us to do better performances.

BD: In the great works, or even in the lesser works, how much is art and how much is entertainment?

Freni: It depends. A lot of what has to do with distinguishing between art and entertainment is the way they are presented, and which cast you have. If there is the possibility to have a big cast and a big production, it’s very much art with divertimento for me. The word

‘divertimento’ gives the sense of something amusing.

Ghiaurov: There is a lot of entertainment in the big pieces, and it goes with the art if they are done right.

BD: So it

’s all wrapped up together?

Freni: Yes.

For me it sometimes depends, especially if you have a nice cast. I will give you an example. We have done this production of Fedora in La Scala and it was fantastic. It had been thirty-five years since they had done this opera because they don’t like it too much. The critics say they don’t like it, but the audience said they like it but not completely. We discovered it for them, and they weighed it and now they audience discovered this work. This is art and divertimento for everybody. I have sung many performances of Fedora, but this was the first time in La Scala. I meet people in the street and they thank me for this Fedora. They said it’s a beautiful show. It’s not only me. It’s because together with the producer, with Plácido, with all the cast, we make it really something they believe. It was not divertimento, but it is art.

BD: Is it special for you to bring a different opera which they like so much, rather than just another Mimì?

Freni: [Gently chiding] I adore my Mimì because I have done this role many times, but not only Mimì. I don’t leave it. Two months ago I was just with Nicolai, and we sang it in La Scala before we came here. I adore it and continue to do it. After this Fedora I go to sing Mimì yet again, but naturally, in forty years of career I’m more excited and interested to sing something new for me, to use my experience and my maturity to do something different. It is also for the theater, for the audience, to give something new, because in forty years I’ve sung many roles.

BD: What advice do you have for younger singers who want to have a forty-year career?

Freni: Oh it’s easy. They have to love to say

‘no’! [Laughs] They have to work very hard, and be honest with the possibility to wait to sing some roles. No twenty-two year old should sing Butterfly. I said ‘no’, and I never sang Butterfly on stage in my life.

BD: There is just the recording?

Freni: Just the recording and the movie, because really for me it’s very dangerous. I can do it. I know can, but it demands too much energy, too much emotion, and you pay very, very dearly for it later. For this reason, I say no, no, no and no! Karajan and many, many other big conductors have asked for it, but I’m sorry. It’s important to be humble in front of the music, to do the best you can to build a career, and to know really well what you can do.

BD: But how does a young singer of twenty-two or twenty-five, or even thirty or thirty-five know what he or she can do?

Freni: It’s easy. When you force, you are too tired. It’s not difficult to understand it. The opera is not for forcing the voice.

BD: So you try it in the studio?

Freni: Yes, naturally you try, but you will see if it’s not right for you. When I did my debut for Don Carlo, for Otello¸ for Requiem, for Adrianna, for Manon Lescaut, I knew they are very heavy roles. If I found in the main dress rehearsal it’s too much for me, I would say,

“Bye-bye.”

BD: [Surprised] So you would go right up through the dress rehearsal???

See my Interviews with Ruggero Raimondi, José van Dam, and Thomas Moser

[Ghiaurov recorded Aïda twice: Caballé/Muti, and Ricciarelli/Abbado. He also recorded another

Don Carlo with Tebaldi, Bergonzi, Fischer-Dieskau, Bumbry, and Talvela, conducted by Solti]

Freni: Yes, because it’s important to see what happens on stage with the orchestra, and with the emotion when you have the audience. At home it’s easier. But naturally, if I tried ten years ago to sing Norma, I know I could do it, but not now because it’s not for me. There are many young singers who sing because their top notes are easy. I was in this way, but those roles are not for not me. Karajan asked me to sing Turandot on record, but I said I would only sing Liù.

BD: [Gently protesting] But obviously Karajan heard something in your voice that he wanted in that role.

Freni: I think because I was very easy in the top notes. He loves me and he knows we have a very nice collaboration. Perhaps he thinks with Mirella we can do something, but I don’t want to destroy my voice.

See my Interviews with Paul Plishka, and Birgit Nilsson

[Ironically, Ghiaurov had recorded Timur five years previously on a set where Caballé sings Liù!

The booklet-cover is shown below, and includes a link to a photo taken at a recording session.]

BD: So you could do it once or twice, but that would be the end of your career?

Freni: No, never! Never, I repeat! I don’t want to do this. Even if I am at the end of my career, I don’t want to do something that is not for me. You must know very well what you can do with your voice and your personality. Never!

BD: [With a mischievous wink] Never?

Freni: Never! [Both laugh] One must learn to say

‘no’. I said ‘no’ many times to Karajan.

BD: [To Sig. Ghiaurov] Have you any advice for the young singers coming along?

Ghiaurov: In every period you can count on your two hands some voices or singers that arrive to the top. There’s a natural selection that happens with singers, and it’s not a matter of giving advice or not giving advice. Today there is much talent, many young beautifully-prepared voices, and they study. I don’t think that they will need our advice. They will take care of themselves, and they will try to do what they want, and what they think. Theaters naturally try to look for singers who will be able to attract an audience, and perform and give. What I can say is the human voice requires a long period of time in order to be ready. Often times the big mistake of young singers is that they’re flattered by the possibility of making a lot of money right away, and doing a fast career. This is where the selection happens because the silly ones fall. I’ve seen so many of those with beautiful voices. They all thought they were the new Callas or Di Stefano, and they have just burned out. It requires long preparation and very hard work. It’s a human body, and it’s the same as it was a hundred years ago. You can’t fix it, or program it like a computer, or hurry the time of preparation. The preparation of the voice requires four or five years of very serious study, and afterwards you can start to sing.

Freni: Yes, but also for this reason this good singer with a good voice must learn learn to say

‘NO’! I don’t want them to fall down and have to be picked up, because we need to have a new generation that can make it for a long career, and not only for three or four or five or ten years. That’s not enough.

Ghiaurov: A good singer must be a conglomerate of many good qualities. Character, for instance, musicality, musicianship, talent, dramatic talent, and in addition to all that you must have this beautiful natural voice and develop it to the maximum. It’s the same thing when you have pianist or violinist. Everybody plays, and yet only five or ten would go to the top.

See my Interviews with Michel Plasson, and the French Diction Coach

on this (and other) recording(s), Janine Reiss

BD: Without mentioning any names, are there singers coming along who will have the kind of career the great singers of today and yesterday and the day before have had?

Ghiaurov: It’s hard for me to say because I’ve seen some with the possibility, but then a lot of things depend on what happens in the special circumstances of their life and career. It’s a very complicated matter; it’s hard to tell.

Freni: Naturally it must come that some make the very, very big career, but I feel now it could be more difficult because there are not many great teachers. Everything has changed in the theater. In our time there were many who helped us with the traditions. I don’t speak about Chicago because here you have really incredible teachers. They work, and you have really very, very, good younger singers with big possibility. But now this depends if they learn to say

‘no’, to understand what they really must do. But I speak generally that in the theater today you don’t find the teachers that care about the young singers like they did with us. Also the conductors have no time to stay to work with the young singer. They worked with us and helped us, and that’s important. Now they have lost their time to do it. The young singers don’t have somebody who can really help them, to give the tradition of the Italian opera. It’s really difficult for this reason. These young singers are in trouble because it’s not enough to have a good voice to sing and only to make the notes.

BD: They need to have all of this together?

Freni: Yes. In order to work right, they must learn the Italian, or Russian, or French, or German style. The young singers are not stupid. They need really somebody that can help them. For this reason I am afraid we lose many during their early years. They have the blessing from God. Perhaps some can do it alone, but there are many others who need more help. They need the technique of the voice, but thank God we have many things from nature. We were born like this, you know, and they need to work better, have somebody to take care more in this. Now there are not many teachers, not many conductors who take care of them, and we lose many on the road.

BD: Despite all of this, are you optimistic or not optimistic about the future of opera?

BD: Despite all of this, are you optimistic or not optimistic about the future of opera?

Freni: Not too much for the way I wish. We have many, many more theaters built in the last forty years, and naturally they demand more of the young singers. As I say, they have no time to grow up, to study, to wait because it’s important to have a nice balance with your body and your mind. Maturity is a very difficult career choice, but it interesting, fantastic, believe me. [Laugh] I am old, but I am still with enthusiasm.

BD: One last question. Is singing fun?

Freni: For me, yes. It is my life. It’s something strange, and it is difficult to explain because it’s a liberating feeling. There is a sensation, and inside really I am happy when I sing.

Ghiaurov: For me it’s complicated. Mirella is much more of an extrovert, and a more optimistic person.

Freni: I love everything now in an enthusiastic way. Nicolai is more serious, more brooding.

Ghiaurov: For me, too, it is a great joy to sing, but at the same time there is a suffering underneath. My character is that of a perfectionist.

Freni: Me too.

Ghiaurov: Perhaps you suffer less than I do! [Both have a huge laugh] I just ponder by myself a little bit.

Freni: To make a big career, sometime there is suffering, but I’m optimistic. I’ve enjoyed everything. I react in a different way from him. Nicolai takes everything inside him. It’s different from how I feel.

You can see the difference. Nicolai is more profound, but I am more open. [Laughs]

BD: You make the ideal couple.

Freni & Ghiaurov together: Yes!

Freni: He helps me to stay relaxed. I help him, push him a little.

Ghiaurov: There’s a great joy in making music and producing these sounds to use this phenomenal instrument, which is the human voice. It is a gift of God to have a voice. It’s a great, great joy. It’s also a great joy to approach great characters that have been written by the great composers.

Freni: We are very lucky because it’s a very hard job. It’s difficult. It’s not easy, believe us. I’m forty years in this career, and Nicolai also the same. We have a very big experience now of the joys and of the suffering, and everything else, but we are lucky to be doing what we love.

BD: We are the ones who are lucky to have experienced your artistry.

Freni: That’s kind of you to say. Thank you

Ghiaurov: Thank you very much.

© 1981 & 1994 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in Chicago on December 10, 1981, and November 14, 1994. The first interview was edited and published in Nit&Wit Magazine in September of 1994. Portions of each artist alone were broadcast on WNIB in 1990, 1995, 1997, 1999, and 2000. Brief selections from each singer were given to Lyric Opera of Chicago for use on their website as part of their group of Jubilarians, celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the company in 2004 by honoring several artists who were important during the early days of the company. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website,click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.