Neuropilin-2 mediates VEGF-C–induced lymphatic sprouting together with VEGFR3 (original) (raw)

If neuropilin-2 and the growth factor VEGF-C don’t come together, lymphatic vessels don’t branch apart.

Abstract

Vascular sprouting is a key process-driving development of the vascular system. In this study, we show that neuropilin-2 (Nrp2), a transmembrane receptor for the lymphangiogenic vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C), plays an important role in lymphatic vessel sprouting. Blocking VEGF-C binding to Nrp2 using antibodies specifically inhibits sprouting of developing lymphatic endothelial tip cells in vivo. In vitro analyses show that Nrp2 modulates lymphatic endothelial tip cell extension and prevents tip cell stalling and retraction during vascular sprout formation. Genetic deletion of Nrp2 reproduces the sprouting defects seen after antibody treatment. To investigate whether this defect depends on Nrp2 interaction with VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) and/or 3, we intercrossed heterozygous mice lacking one allele of these receptors. Double-heterozygous nrp2vegfr2 mice develop normally without detectable lymphatic sprouting defects. In contrast, double-heterozygote nrp2vegfr3 mice show a reduction of lymphatic vessel sprouting and decreased lymph vessel branching in adult organs. Thus, interaction between Nrp2 and VEGFR3 mediates proper lymphatic vessel sprouting in response to VEGF-C.

Introduction

Organ system development across higher order species requires formation of tubular networks. These networks can be found in the respiratory system (Affolter and Caussinus, 2008), in the vertebrate ureteric system (Costantini, 2006), and most prominently, in the circulatory system, including the blood and lymphatic vasculature (Horowitz and Simons, 2008). The architecture, and therefore function of such systems, is largely determined by one key topographical feature: branching, which occurs by the sprouting of new tubes from preexisting ones. Thus, the molecular mechanisms regulating sprouting are central to how a given branching system forms (Horowitz and Simons, 2008), yet our understanding of this process is limited.

The lymphatic vasculature forms a hierarchical branching network that covers the skin and most internal organs of the body. The lymphatic system maintains tissue fluid balance by recovering fluid from the interstitial space (Alitalo et al., 2005). Unlike the circulatory system, the distal-most branches of the lymphatic vasculature are blind-ended capillaries that drain into larger-collecting lymphatics and return the lymph to the hematogenous system via the thoracic duct (Cueni and Detmar, 2006; Tammela et al., 2007). Imbalances in circulation of fluid or cells can result in lymphedema or disturbed immune responses.

In the mouse, lymph vessel development begins around embryonic day 10 (E10) by sprouting from the cardinal veins in the jugular and perimesonephric area to form lymph sacs. From these lymph sacs, vessels subsequently grow by proliferation and centrifugal sprouting toward the skin and internal organs (Maby-El Hajjami and Petrova, 2008; Oliver and Srinivasan, 2008). After the initial differentiation and budding of lymphatic vessels, which is regulated by Prox-1 and Sox-18 (Wigle et al., 2002; François et al., 2008), their subsequent migration, growth, and survival are mainly controlled by VEGF-C (Karpanen and Alitalo, 2008; Maby-El Hajjami and Petrova, 2008). Homozygous _vegf-c_–null mice show Prox1-positive cells in their cardinal veins, but these cells fail to migrate and form the primary lymph sacs, resulting in the complete absence of lymphatic vasculature in mouse embryos (Karkkainen et al., 2004). Overexpression of VEGF-C in transgenic mouse models or using viral delivery systems is a potent inducer of lymphatic endothelial survival, growth, migration, and proliferation (Jeltsch et al., 1997; Wirzenius et al., 2007).

VEGF-C binds to Flt-4/VEGF receptor 3 (VEGFR3), a receptor tyrosine kinase that is expressed at early stages of lymphatic vessel formation (Joukov et al., 1996). VEGFR3 appears to be the main signal-transducing receptor mediating VEGF-C actions during lymphatic vessel growth (Veikkola et al., 2001). However, in addition to VEGFR3, VEGF-C also binds additional receptors including VEGFR2 (Skobe et al., 1999) and coreceptors including the neuropilin-2 (Nrp2) receptor (Karkkainen et al., 2001) expressed on veins and lymphatic vessels. Nrp2 was initially identified as a class 3 semaphorin receptor and mediator of axon guidance (Chen et al., 1997; Giger et al., 1998). Homozygous nrp2 mutants show a reduction of small lymphatic vessels and lymphatic capillaries, indicating that Nrp2 is not required for lymphatic development but modulates it (Yuan et al., 2002). Moreover, inhibition of Nrp2 using a monoclonal antibody that selectively blocks VEGF-C binding to Nrp2 resulted in a reduction of tumor lymphangiogenesis and metastasis, which is a result with significant clinical implications (Caunt et al., 2008). However, these experiments did not address the mechanism by which Nrp2 mediates lymphangiogenesis in developmental or pathological contexts.

In this study, we show that in vivo modulation of Nrp2 using blocking antibodies or genetic reduction of Nrp2 levels results in selective disruption of lymphatic sprout formation without affecting other aspects of lymphatic development. The inhibition of sprout formation appears to be a result of altered behavior of tip cells at the leading ends of lymphatic vessel sprouts. Finally, we show that Nrp2 genetically interacts with VEGFR3 and not VEGFR2, indicating that Nrp2 partners with VEGFR3 to mediate lymphatic vessel sprouting. Thus, like in the nervous system, where Nrp2 mainly regulates axon guidance, its function in the lymphatic vasculature appears to affect a particular step of formation of the lymphatic tree. However, although the guidance functions Nrp2 exerts in response to semaphorins in the nervous system are mainly repulsive and mediate growth cone collapse (Chen et al., 2000), they appear to be attractive in the vascular system, mediating tip cell extension and guided vessel sprouting in response to VEGF-C.

Results

Tail dermal lymphatics as a model system for studying developmental lymphangiogenesis

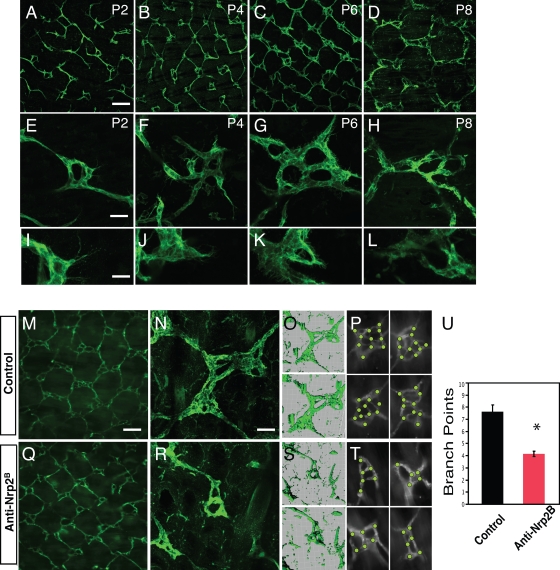

The superficial dermal lymphatic network of the adult mouse tail consists of a hexagonal lattice of lymphatic capillaries (Hagendoorn et al., 2004). At each junction in this matrix, there is a multiringed lymphatic vessel complex (hereafter referred to as lymphatic ring complexes [LRCs]) that connects the superficial network to collecting ducts. Initially, we performed a developmental analysis of lymphatic network formation. As the network largely forms after birth by sprouting from the major lateral lymphatic vessels that lie in the deeper dermis and the mature hexagonal pattern is established by postnatal day 10 (P10), we restricted our analysis to this early postnatal time frame (Fig. 1). We found that grossly, the lymphatic vessels have an irregular, discontinuous pattern at early time points (P2; Fig. 1 A) with only few LRCs comprised of only single-ringed vessels (Fig. 1 E). Multiple lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) with numerous filopodial extensions, which are morphologically similar to the tip cells that have been described at the ends of growing blood vessels (Gerhardt et al., 2003, 2004), protrude from the LRC (Fig. 1 I). By P4, the network takes on a regular rhomboid pattern (Fig. 1 B). At this point, the LRC is more prevalent and is comprised of 2–3 ringed structures (Fig. 1 F) with numerous tip cells (Fig. 1 J). These tip cells are occasionally seen contacting each other or stalk cells to form adjacent rings. By P6, the overall pattern becomes more hexagonal (Fig. 1 C), driven in part by the expansion of the LRCs, which now have 4–5 rings (Fig. 1 G). Tip cells are still extended from the rings but are rarer in comparison with P4 (Fig. 1 K). By P8, the regular hexagonal pattern that is seen in the adult tail is established (Fig. 1 D). The LRCs are composed of four to six rings (Fig. 1 H) and now extend above and below the plane of the network, appearing more 3D. Tip cells are generally not seen protruding from the rings (Fig. 1 L). Thus, it appears that the development of the LRC is a key to the formation of the regular hexagonal pattern and acquires increasing complexity by a sprouting process over the first postnatal week of life.

Figure 1.

Nrp2 inhibition results in abnormal tail dermal lymphangiogenesis. (A–L) Developmental time course of tail dermal lymphangiogenesis by whole-mount LYVE-1 immunohistochemistry at P2, 4, 6, and 8. The tails are imaged to show the overall lymphatic network pattern (A–D), to demonstrate representative ring complexes (E–H), and to demonstrate tip cells extending from the complexes (I–L). (M–U) Treatment with anti-Nrp2B results in alteration of lymphangiogenesis. The lymphatics in anti-Nrp2B–treated tails at P8 after treatment at P1, 3, and 5. 3D projections of the confocal images in control (O) and anti-Nrp2B–treated ring complexes (S) in N and R, respectively. The bottom projection is rotated 45° to provide depth perspective. (P and T) Representative examples of junctions with dots to denote tallied branch points in control (P) and anti-Nrp2B (T)–treated tails. (U) Quantification of branch points in ring complexes of control and anti-Nrp2B–treated tails (n = 10 junctions/animal for six animals per condition; *, P < 0.0001). Error bars indicate SEM. Bars: (A–D, M, and Q) 250 µm; (E–H) 60 µm; (I–L) 25 µm; (N–R) 75 µm.

Inhibition of Nrp2 results in abnormal tail dermal lymphangiogenesis

To understand the role of Nrp2 in lymphatic development, we studied the consequences of Nrp2 inhibition in this tail dermal lymphangiogenesis model (Fig. 1). We inhibited Nrp2 using a function-blocking anti-Nrp2 antibody that selectively blocks the binding of VEGF family ligands to Nrp2 (anti-Nrp2B; Caunt et al., 2008). This antibody also blocks VEGF-C function in vitro in VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 activation assays and in vivo (Caunt et al., 2008). Anti-Nrp2B treatment has a significant impact on the development of rings in the dermal lymphatic network. As noted, the control anti-ragweed–treated LRCs were comprised of four to six rings (Fig. 1 N) with a complex 3D topography. In contrast, the anti-Nrp2B–treated LRCs were simpler, generally comprised of one to two rings (Fig. 1 R). Quantification of the number of branch points in control and anti-Nrp2B–treated animals showed a significant reduction from 7.4 to 4.6, respectively (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1, P, T, and U). As a result of the less-complex, smaller rings, the network retained the rhombus pattern rather than maturing to the hexagonal pattern (Fig. 1, M and Q).

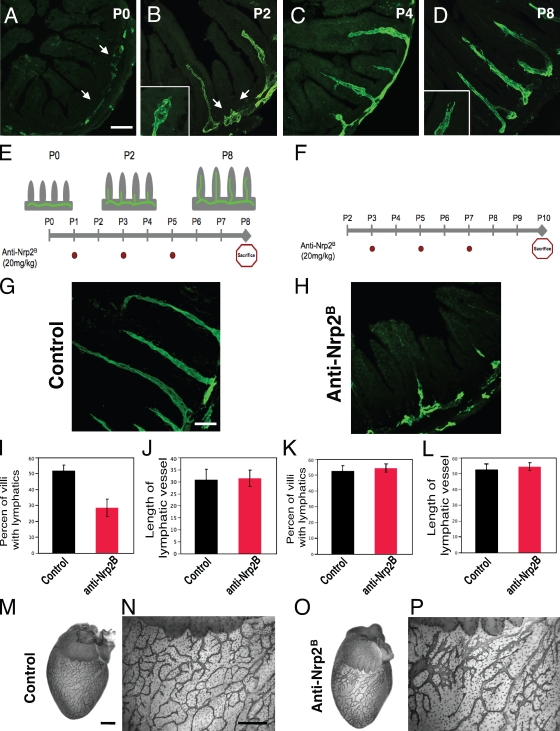

Nrp2 inhibition results in reduced lymphatic sprout formation

To examine whether Nrp2 inhibition affected the sprouting process, we evaluated the effects of anti-Nrp2B on the development of another lymphatic network with stereotypic pattern and sprouting behavior, the intestinal lymphatic network (Fig. 2; Kalima, 1971). Again, we performed a developmental analysis of sprouting lymphangiogenesis in the small intestine and confirmed that the intestinal lymphatic network provides another ideal system for studying lymphatic sprouting, with sprout initiation occurring between P0 and P2 (Fig. 2, A–D). Next, we injected anti-Nrp2B starting at P1 during sprout initiation (Fig. 2 E) to study effects on sprout formation. Nrp2 inhibition resulted in a reduction of the number of villi with sprouts compared with control-treated animals (Fig. 2, G–J). The percent of villi with lacteals dropped significantly from 52% in control-treated animals to 28% in anti-Nrp2B–treated animals (P = 0.004; Fig. 2 I). Interestingly, the mean length of a lacteal was not affected by anti-Nrp2B treatment (30.7 in control animals vs. 31.4 in anti-Nrp2B–treated animals; P = 0.54; Fig. 2 J), suggesting that once a sprout was established, inhibition of Nrp2 did not have any effect on intestinal lymphatics. This supported the idea that Nrp2 did not play a role in lymphatic sprout extension. To test this possibility, we performed additional experiments in which we initiated anti-Nrp2B treatment at P3, after sprout initiation, and during extension of the developing lacteals (Fig. 2 F). As predicted, inhibition of Nrp2 at this point did not have significant impact on lymphangiogenesis (Fig. 2, K and L). We also tested the effect of anti-Nrp2B treatment on mature, established lymphatic vessels in many organs including the intestines, skin, and pancreas. Extended treatment with high dose (100 mg/kg) anti-Nrp2B for 25 wk did not alter lymphatic structure (Fig. S1).

Figure 2.

Nrp2 inhibition reduces lymphatic sprouting in developing intestinal and epicardial lymphatics. (A–D) Developmental time course of intestinal lymphangiogenesis by LYVE-1 immunohistochemistry. (A) At P0, lymphatics are restricted to the submucosa (arrows). (B) By P2, lymphatic branches have extended into a portion of some villi, and newly formed sprouts (arrows) can be seen to form on the submucosal lymphatic vessel adjacent to other villi. Tip cells with filopodia (inset) are present on the growing lacteals. (C and D) By P4 (C), most villi have a developing lacteal, which extends to the villus tip by P8 (D). Tip cells (inset) can still be observed at the ends of the vessels. (E) Scheme of the time course of lymphatic sprouting into intestinal villi and representation of experiments shown in G, I, and J. Anti-Nrp2B was injected i.p. at P1, 3, and 5 (red dots), animals were sacrificed at P8, and tissues were analyzed. (F) Schematic representation of experiment shown in H, K, and L. Anti-Nrp2B was injected i.p. at P3, 5, and 7 (red dots), animals were sacrificed at P10, and tissues were analyzed. (G–J) Analysis of intestines from the experiment depicted in E. (G and H) Control-treated intestines (G) have a normal-appearing lymphatic pattern in contrast to anti-Nrp2B–treated intestines (H) in which a larger portion of villi lack lacteals. (I and J) Quantification of the percent of villi that have lacteals and villi length. (I–L) 50 villi per animal for six animals per treatment condition were analyzed. (M–P) Control (M and N) and anti-Nrp2B (O and P)–treated hearts showing reduced branching and increased vessel thickness in portions of the anti-Nrp2B–treated hearts. Error bars indicate SEM. Bars: (A–D) 250 µm; (G and H) 125 µm; (M–P) 400 µm.

Additionally, we characterized the pattern of lymphatic development in the heart, which has a highly branched surface epicardial lymphatic network (Fig. 2, M–P) that develops from P0 onward (Yuan et al., 2002). We noted that although at P8 control hearts have a highly branched lymphatic network (Fig. 2, M and N), treatment with anti-Nrp2B resulted in the simplification of the network with a reduction in the number of branches (Fig. 2, O and P). In addition, the anti-Nrp2B–treated lymphatic vessels were strikingly enlarged compared with the control-treated vessels (Fig. 2, N and P), suggesting that lymphatic cell expansion was ongoing, but rather than forming sprouts, the vessels were instead increasing in size.

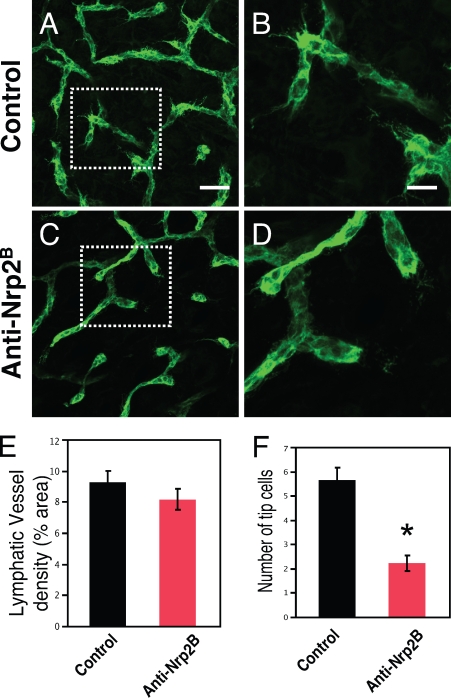

Tip cell abnormalities develop upon treatment with anti-Nrp2B

Our data support the notion that treatment with anti-Nrp2B inhibits sprout formation in three different developing lymphatic systems. Furthermore, our observations in the tail dermal lymphatics implied that there was a dramatic reduction in the number of tip cells that extend from LRC. This raised the possibility that Nrp2 inhibition resulted in a tip cell defect, which inhibited sprout formation. Thus, we evaluated whole-mount preparations of dorsal trunk skin at P8, which is when dermal lymphatics are undergoing a rapid branch expansion and the tips of many developing branches have morphologically distinct tip cells. In control-treated animals, we noted that the dermal lymphatic network was highly branched, and a large proportion of branches had a tip cell (5.6 tip cells per high powered field; Fig. 3, A, B, and F) with many filopodial extensions. In contrast, treatment with anti-Nrp2B resulted in the loss of these specialized cells (2.2 tip cells per high powered field; P < 0.01; Fig. 3, C, D, and F) and a reduction in branch number. Although the number of tip cells was dramatically reduced, the total vessel area appeared unchanged (Fig. 3 E). Furthermore, no morphological differences were observed with the stalk cells between anti-Nrp2B and control-treated animals, which is consistent with Nrp2-mediating tip cell–specific effects.

Figure 3.

Anti-Nrp2B treatment reduces tip cell number in dermal lymphatics. (A–D) Control (A and B) and anti-Nrp2B (C and D)–treated skin showing a reduction in the number of tip cells. The boxed areas in A and C are shown at higher magnifications in B and D, respectively. (E) No change in lymphatic vessel density was noted between control and anti-Nrp2B–treated samples. (F) A significant reduction in the number of tip cells per high powered field was noted between control and anti-Nrp2B–treated samples. Error bars indicate SEM. *, P < 0.01. Bars: (A and C) 150 µm; (B and D) 70 µm.

To further understand the basis of these selective effects on tip cells, we evaluated Nrp2 expression on developing lymphatics in many of these systems at the time of sprout formation. Immunostaining for Nrp2 revealed Nrp2 expression in developing lymphatic vessels. Nrp2 was found at higher levels in tip cells of new sprouts (Fig. S2) in both dermal lymphatics and lacteals. Additionally, Nrp2 was present in filopodial extensions emanating from the tip cells.

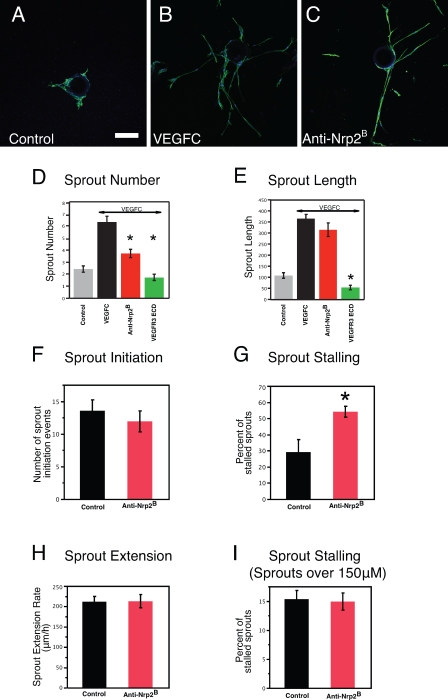

Anti-Nrp2B treatment in vitro reduces sprout formation and alters tip cell behavior

To directly evaluate the cellular basis for why Nrp2 inhibition affects sprout development, we tested the effects of anti-Nrp2B on LEC sprouting using an in vitro sprouting assay. Over the course of 14 d, the LECs form sprouts that radially extend from the bead and often display lumen formation and branching, which is highly reminiscent of lymphatic vessel sprouting in vivo. In the presence of VEGF-C, the LECs proliferate and form robust sprouts that extend from the bead (Fig. 4, A and B). Treatment with anti-Nrp2B reduced the number of sprouts (Fig. 4, C and D). Stimulation by VEGF-C resulted in an increase of sprout number from a mean of 2.4 sprouts per bead to a mean of 6.3 sprouts per bead (P < 0.01). Inhibition of Nrp2 by anti-Nrp2B in the presence of VEGF-C resulted in a significant reduction in the number of sprouts to 3.7 (P < 0.0001 compared with VEGF-C). As a positive control for blocking VEGF-C activity, the VEGFR3 extracellular domain protein (ECD; Mäkinen et al., 2001; Caunt et al., 2008) reduced sprouting to 1.7 sprouts per bead, which is a level comparable with the no VEGF-C control. Nrp2 inhibition did not affect mean sprout length (364 pixels in VEGF-C treated vs. 314 pixels in anti-Nrp2B treated; P = 0.09) in contrast to VEGFR3 ECD (53 pixels; P < 0.0001; Fig. 4 E). These data corroborate our in vivo observations that Nrp2 inhibition results in reduced sprouting but not sprout length, likely not affecting stalk cells. It also suggested an effect on the initial aspects of sprout formation.

Figure 4.

Anti-Nrp2B treatment in vitro results in reduced sprout formation and altered tip cell behavior. (A–C) Representative examples of LECs sprouting from coated beads in control (A), VEGF-C (B)–, or anti-Nrp2B (C)–treated cultures stained with anti–LYVE-1. (D) Sprout number is significantly reduced with anti-Nrp2B or VEGFR3 ECD treatment compared with VEGF-C treatment alone. (E) Sprout length is not reduced with anti-Nrp2B treatment but is reduced by VEGFR3 ECD treatment compared with VEGF-C treatment alone (n = 5 beads/well for 10 wells). (F–I) Quantification of sprout initiation events (F), sprout-stalling events (G), and sprout extension rates from live imaging experiments. Error bars indicate SEM. *, P < 0.01. Bar, 150 µm.

To gain further mechanistic insight into how Nrp2 inhibition may affect initial sprout formation, we performed live imaging of the bead cultures to observe and analyze tip cell behavior in real time in the presence or absence of the anti-Nrp2B antibody. We evaluated the number of sprout initiation events and the behavior of sprouts after initiation. We noted that treatment with anti-Nrp2B did not have any effect on the mean number of sprout initiation events during the first day of culture (Fig. 4 F). This was surprising given our finding of fewer sprouts in treated cultures (Fig. 4 D). We also observed that sprouts that initiated on control-treated beads generally developed into larger stable sprouts. In contrast, the sprouts that initiated from anti-Nrp2B–treated beads often stalled (Fig. 4 G) and retracted back to the bead (54% stall rate compared with 28% in control beads; P = 0.019). Once a sprout had extended to 150 µm in length, stalling and sprout elongation rates were not affected by inhibition of Nrp2 (Fig. 4, H and I). In these cultures and those observed after additional culturing for 48 h, no differences were noted in stalk cell behavior between control and anti-Nrp2B–treated cultures. Thus, Nrp2 inhibition increased the rate at which tip cells, which are initiating lymphatic sprouts, stall and retract. This results in a reduction in the number of sprouts in vitro and reduced lymphatic sprouting and altered tip cell morphology in vivo.

As modulation of cytoskeletal dynamics have been shown to be critical for tip cell growth, we evaluated the effects of Nrp2 inhibition on actin and microtubule cytoskeletal elements in LEC in culture. No changes were noted either in control VEGF-C–stimulated cells or in stimulated cells treated with anti-Nrp2B (Fig. S3). Additionally, no changes in activation of Rac, Rho, or Cdc42 were observed (Fig. S3). However, such changes may only occur at a subcellular level in actively sprouting tip cells.

LECs express VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 in vitro and in vivo

Nrp2 is thought to act as a VEGF-C coreceptor and is not known to activate any downstream signaling pathways via its intracellular domain. It is believed to work with the VEGFR family of receptor tyrosine kinases to promote VEGF-C signaling (Soker et al., 2002; Favier et al., 2006). Nrp2 can promote VEGF-C signaling via VEGFR2 and VEGFR3, and inhibition of Nrp2 modestly but significantly reduces VEGF-C–mediated activation of both receptors (Favier et al., 2006; Kärpänen et al., 2006; Caunt et al., 2008). Thus, neuropilins serve to augment the signaling of VEGF family ligands by VEGFRs.

To determine whether one or both of these receptors could interact with Nrp2 during lymphatic development, we investigated which of these VEGFRs are present on LECs. FACS analysis demonstrated that cultured LECs express both VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 (Fig. S2). Immunohistochemical analysis of developing lymphatic vessels of the intestine showed that as with the cultured LECs, both VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 are expressed (Fig. S2), which is in agreement with previous studies (Veikkola et al., 2001; Wirzenius et al., 2007). Therefore, we performed genetic analysis to determine which of the two VEGFRs partners with Nrp2 to functionally drive lymphatic sprouting and lymphangiogenesis.

We intercrossed heterozygous mice lacking one allele of these receptors. C57/BL6 nrp2vegfr2 or nrp2vegfr3 double-heterozygous mice were generated by interbreeding nrp2+/− mice (Giger et al., 2000) with mice carrying a knock-in of the egfp gene into the flk-1/vegfr2 locus (vegfr2+/egfp mice) or mice carrying a b-galactosidase knock-in into the vegfr3 locus (vegfr3+/lacZ mice; Dumont et al., 1998). Possible lymph vessel defects had not been previously analyzed in the present _nrp2_−/− mutants but were highly similar to those described in a different nrp2 loss of function mutation generated by a gene trap approach (Fig. S4; Chen et al., 2000; Yuan et al., 2002).

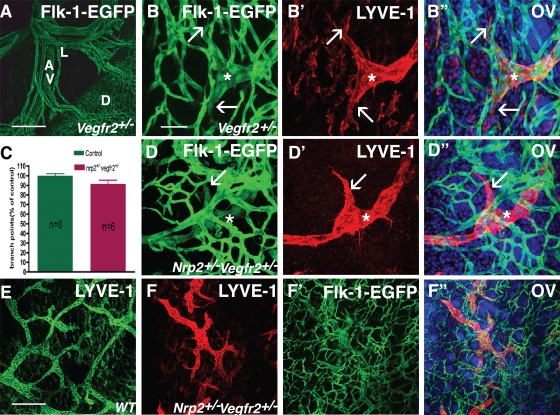

Normal lymphatic development in double-heterozygous nrp2+/−vegfr2+/− mice

We intercrossed heterozygous nrp2+/− mice with vegfr2+/egfp mice to test for possible defects in lymphatic vessel development in double-heterozygous offspring. Whole-mount analysis of P1 guts showed egfp expression in mesenteric arteries, veins, and capillaries covering the gut surface as well as robust egfp expression in lymphatic mesenteric vessels (Fig. 5 A). Similarly, double labeling of skin isolated from the trunk or tail of vegfr2+/egfp mice with the lymphatic marker LYVE-1 showed double labeling of lymphatic vessels with both egfp and LYVE-1, extending into the tips of sprouting lymphatic vessels (Fig. 5, B–B″). Arteries, veins, and capillaries expressed only egfp. Thus, consistent with the results obtained using antibody labeling (Fig. S2), vegfr2 expression was routinely detected by this reporter construct in lymphatic vessels including sprouting tips.

Figure 5.

Normal lymphatic development in double-heterozygous nrp2+/−vegfr2+/− mice. (A) EGFP staining of mesenteric vessels in a heterozygous vegfr2-egfp mouse pup at P0. Note green fluorescence in capillaries covering the surface of the duodenum and in mesenteric arteries, veins, and lymphatic vessels. D, duodenum; A, mesenteric arteries; V, veins; L, lymphatic vessels. (B–B″) EGFP–LYVE-1 double staining of tail skin at P1. Note Flk-1–EGFP expression in a lymphatic vessel sprout (asterisks) and in filopodia-extending tips (arrows). (C) Quantification of lymph vessel branch points. Error bars indicate SEM. (D–D″) Normal appearance of lymphatic vessel sprouts (asterisks) and filopodia-extending tips (arrows) in P1 tail skin in double-heterozygous nrp2+/−vegfr2+/− mice. (E and F) Lower magnification views of LYVE-1–positive lymphatic vessels in wild-type (E) and nrp2+/−vegfr2+/− dorsal trunk skin. WT, wild type. (F’–F″) Flk-1/VEGFR2-EGFP–LYVE-1 double labeling. OV, overlay. Bars: (A) 200 µm; (B–D″) 50 µm; (E–F″) 200 µm.

As the egfp insertion disrupts transcription of the vegfr2 gene, homozygous vegfr2_egfp/egfp die at early embryonic stages as a result of failure of blood vessel formation. However, heterozygous mice are viable and fertile and develop no detectable blood vascular or lymphatic malformations. Double-heterozygous nrp2+/−_vegfr2+/− mice were born at normal Mendelian ratios (12 litters, 79 mice, 16 wild type, 25 nrp2+/−, 16 vegfr2+/−, and 22 nrp2+/−vegfr2+/−). Real-time PCR of hearts isolated from P5 wild-type and nrp2+/−vegfr2+/− mice showed that, as expected, mRNA levels of flk-1/vegfr2 and nrp2 were decreased by ∼50% in the double-heterozygotes compared with wild-type littermates (Fig. 6 B). In contrast, levels of vegfr3 or podoplanin were not significantly different in nrp2+/−vegfr2+/− compared with wild type (Fig. 6 B).

Figure 6.

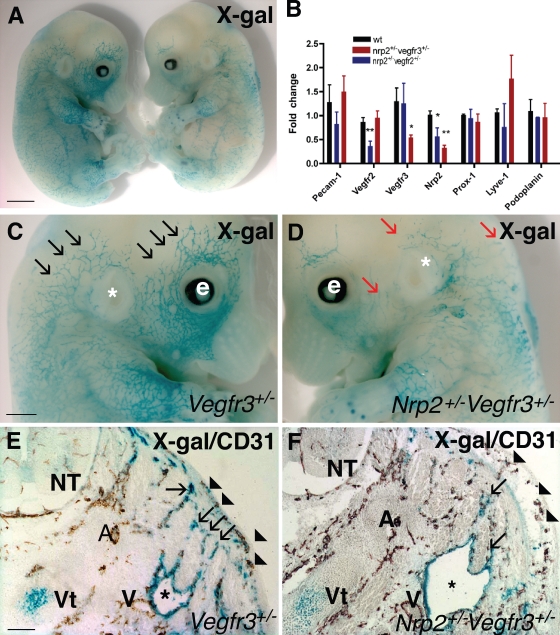

Abnormal lymphatic development in double-heterozygous nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice. (A) X-gal staining (blue) of E13.5 vegfr3+/− (left) and double-heterozygous nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− (right) littermate embryos. (B) expression levels of lymphatic marker genes as measured by quantitative PCR in RNA isolated from hearts of wild-type and double-heterozygote nrp2+/−vegfr2+/− and nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice. Values significantly different from wild-type mice (*, P > 0.05; **, P > 0.001) by Student’s t test are shown. Error bars indicate SEM. (C and D) Higher magnification of heads of embryos shown in A. Note numerous lymphatic vessel sprouts in vegfr3+/− (black arrows) and fewer enlarged lymph vessel sprouts in nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− (red arrows). e, eye; *, ear. (E and F) Transverse section through the neck of E13.5 embryos double stained with X-gal (blue) and CD-31 (brown). Note similar development of CD-31–positive arteries, veins, and skin capillaries (arrowheads) in vegfr3+/− (E) and nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− (F). Note enlarged jugular lymph sacs (asterisks) in nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− (F) compared with vegfr3+/− (E). Lymph vessels sprouting from the lymph sac toward the skin are less numerous in nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− compared with vegfr3+/− (arrows). A, arteries; V, veins; NT, neural tube; Vt, vertebra. Bars: (A) 1.4 mm; (C and D) 0.8 mm; (E and F) 150 µm.

Confocal analysis of whole-mount, double-labeled skins stained with LYVE-1 from tail (Fig. 5, D–D″) or trunk (Fig. 5, E–F″) showed no obvious alteration in capillary density or patterning in double- heterozygous compared with vegfr2 single-heterozygous skins (Fig. 5, compare B with D). Lymphatic vessel patterning and sprouting were also normal (Fig. 5, B and D–F). Quantification of lymphatic vessel branch points from whole mounts of trunk skins stained with anti-VEGFR3 (not depicted) or LYVE-1 showed similar numbers of branch points in control (wild-type single heterozygote) and double-heterozygote nrp2+/−vegfr2+/− animals (Fig. 5 C). Collectively, reduction of vegfr2 and nrp2 levels to 50% of their normal levels is compatible with normal lymphatic vessel development.

Abnormal lymphatic development in double-heterozygous nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice

We next used a similar approach to examine the genetic interaction between nrp2 and vegfr3 (formally denoted as flt4 but hereafter referred to as vegfr3 for clarity). Lymphatic vessel development was evaluated in double-heterozygous nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice. X-gal staining of lymphatic vessels from vegfr3+/lacZ heterozygous embryos (Dumont et al., 1998) showed progressive coverage of the skin from E13.5 onward (Fig. 6 A, left). Double-heterozygous nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− littermates were of similar size and showed no obvious developmental retardation but exhibited reduced X-gal–stained vascular coverage in the skin, which is consistent with reduced lymphatic coverage (Fig. 6 A, right). At a higher magnification, these X-gal–stained vessels in the skin of the head could be seen to sprout and grow toward the dorsal midline in vegfr3+/lacZ heterozygotes (Fig. 6 C), a pattern very similar to that observed in wild-type embryos stained with anti-VEGFR3 antibody (Fig. S4 A). In contrast, sprouting in the double-heterozygous nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− littermates was strongly reduced and appeared similar to the homozygous nrp2 knockout embryos (compare Fig. 6 D with Fig. S4 B). Enlarged, sac-like X-gal–stained structures were observed beneath the skin in the nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− double heterozygotes (Fig. 6 D). Sectioning of embryos and double labeling with CD31 showed no major defect in vessel number or patterning between vegfr3 single heterozygotes and nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− double heterozygotes (Fig. 6, E and F). In contrast, the number of lymphatic vessel sprouts was strongly reduced, and the lymph sacs were strikingly enlarged in the nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− compared with the vegfr3 single-heterozygote littermate, suggesting that rather than forming sprouts, lymph sacs were growing in size in these embryos (Fig. 6, E and F). At this stage, edema formation could be observed by histology (Fig. 6 F), but not grossly. In contrast, severe edema formation was observed in some nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− embryos from E15.5 onward (unpublished data), and they were recovered at reduced Mendelian ratios at birth (32 litters, 235 mice, 67 wild type, 59 nrp2+/−, 69 vegfr3+/−, and 40 nrp2+/−vegfr3+/−), indicating that defective lymph vessel sprouting and edema formation in some of these embryos might have precluded development to term. Real-time PCR analysis of hearts isolated from wild-type and nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice at P5 showed that as expected, levels of nrp2 and vegfr3 in the nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− double heterozygotes were reduced to ∼50% of wild-type levels, whereas expression levels of pecam-1, flk-1/vegfr-2, prox-1, Lyve-1, and podoplanin were not significantly altered (Fig. 6 B). These results confirm the histological findings and suggest that lymphatic specification occurs normally but that aspects of subsequent development of the lymphatic vasculature, notably patterning and sprouting, are deficient in the double-heterozygote mice.

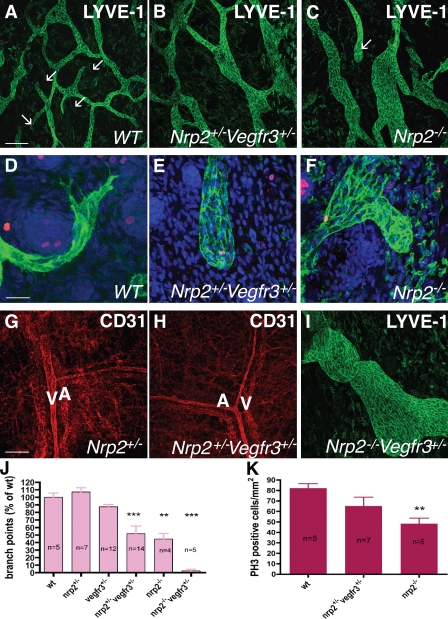

Lymphatic sprouting is selectively affected in nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice

To further characterize these defects, we used confocal microscopy analysis of whole-mount–stained skin preparation to compare wild-type, single-heterozygote, double-nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− heterozygote, and _nrp2_−/− lymphatic vessels (Fig. 7). Lymphatic vessels were visualized using LYVE-1 or VEGFR3 immunostaining with very similar results (Fig. 7 and Fig. S4).

Figure 7.

Defective lymphatic sprouting in nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice. (A–C) Confocal images of LYVE-1–stained lymph vasculature in the dorsal trunk skin at P0. Note enlarged, poorly branched vessels in nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− (B) and nrp2_−/− (C) compared with wild type (A). Several lymphatic tips are present in wild type (A, arrows), none are present in nrp2+/−_vegfr3+/− (B), and one is present in nrp2_−/− (C, arrow). (D–F) LYVE-1 (green)/phospho–histone H3 (red) DAPI (blue) staining of P0 skin; high magnification views of lymphatic tips are shown. Note filopodial-extending tips composed of several cells in wild type (D), whereas both nrp2+/−_vegfr3+/− (E) and _nrp2_−/− (F) show blunt-ended, enlarged tips devoid of filopodial extensions. (G and H) CD31 staining shows similar patterning of blood vasculature in the skin of mice with the indicated genotypes. A, arteries; V, veins. (I) Dorsal trunk skin at P0 in a nrp2_−/−_vegfr3+/− mouse. Note enlarged lymphatic vessel. (J) Quantification of lymphatic vessel branch points in mice of the indicated genotypes. (K) Replication of LECs. The number of phospho–histone H3 (PH3)-positive nuclei per millimeter squared of LYVE-1–positive vessels was counted. WT, wild type. Error bars indicate SEM. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Bars: (A–C) 200 µm; (D–F) 50 µm; (G–I) 200 µm.

Lymph vessels in wild-type mouse skin formed a regular array of uniformly sized, branched vessels with some sprouting tips visible in each image (Fig. 7 A and Fig. S4 L). At high magnification, these tips were composed of one or several filopodia-extending cells that were labeled both by LYVE-1 and VEGFR3 antibodies (Fig. 7 D and Fig. S4 M). In both nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− double-heterozygote and nrp2_−/− skins, lymphatic vessels appeared enlarged and poorly branched (Fig. 7, B, C, and J; and Fig. S4 N). Quantification of the number of branch points using LYVE-1 or VEGFR3 staining showed a 50% reduction in both nrp2+/−_vegfr3+/− heterozygote and _nrp2_−/− mutants compared with wild type (Fig. 7 J). Lymphatic tips were rarely seen in the double-heterozygote or nrp2 mutants. In the cases where tips were observed, their shape was changed when compared with wild type: they were composed of numerous cells that failed to extend filopodia (Fig. 7, E and F; and Fig. S4 O), reproducing treatment with anti-Nrp2B. Nrp2_−/−_vegfr3+/− mice showed enhancement of lymph vessel enlargement and poor branching (Fig. 7, I and J). Staining of wild-type skin sections with alkaline phosphatase (AP)–tagged VEGF-C (VEGF-C–AP) showed that VEGF-C selectively binds to lymphatics. Notably, strong staining was observed for tip cells compared with stalk cells (Fig. S5) and is consistent with the increased Nrp2 levels found in tip cells (Fig. S2). VEGF-C–AP staining was markedly decreased in double-heterozygous animals. In comparison, VEGF-A–AP strongly bound to blood vessels and only weakly stained lymphatic vessels, which is consistent with the immunohistochemistry analysis of VEGFRs (Fig. S2).

Examination of replication of LEC using phospho–histone H3/LYVE-1 double staining showed that there was no significant difference between the numbers of replicating LECs between wild-type and nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− skins (Fig. 7 K). Replication of LEC in nrp2_−/− skins was reduced compared with wild-type, as previously observed in a different nrp2 mutant allele (Yuan et al., 2002). Apoptosis of LECs using cleaved caspase-3 staining was only rarely detected, although some cells in hair follicles of the skin were found positive in each genotype. We found few positive LECs and therefore find it unlikely that increased apoptosis could be a possible cause for these observations. CD31 staining showed normally patterned arteries and veins in the skin of neonatal nrp2+/−_vegfr3+/− mice, confirming that the mutation selectively affected lymphatic vessels (Fig. 7, G and H).

Tip cell abnormalities in nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice are similar to those obtained after anti-Nrp2B treatment

As lymphatic tip cell defects in the neonatal skin of nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice were highly reminiscent of the defects seen in the skin after anti-Nrp2B treatment (Fig. 3), we next compared lymphatic development in these mice with the effects of anti-Nrp2B administration in previously described model systems.

Tail dermal lymphatics were missing in the nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− double heterozygotes until at least P6 (Fig. S5). In contrast, the central collecting lymphatics of the tail were already present at P1 and exhibited the characteristic enlargement and lack of sprouting observed in the trunk skin (unpublished data). Sectioning of the tails and staining with VEGF-C–AP showed that VEGF-C selectively decorated lymphatics, in particular sprouting lymphatics (Fig. S5 E). For comparison, VEGF-A–AP strongly bound to microvessels (Fig. S5 F). Although wild-type tails showed two concentric layers of lymphatic vessels, an inner layer comprising the collecting lymphatics and an outer dermal layer (Fig. 1 and Fig. S5 E), only the inner collecting layer developed in nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− double-heterozygotes and nrp2−/− mutants (Fig. S5, G and I). Lymphatics in this layer still bound VEGF-C, as expected from the presence of VEGFR3 on these vessels in both mutants, but they enlarged rather than formed sprouts in the mutant background and represent an earlier phenotype compared with antibody treatment. Thus, lack of Nrp2 or reduction of Nrp2 and VEGFR3 levels on tail lymphatics leads to selective lack of lymphatic vessel sprouting.

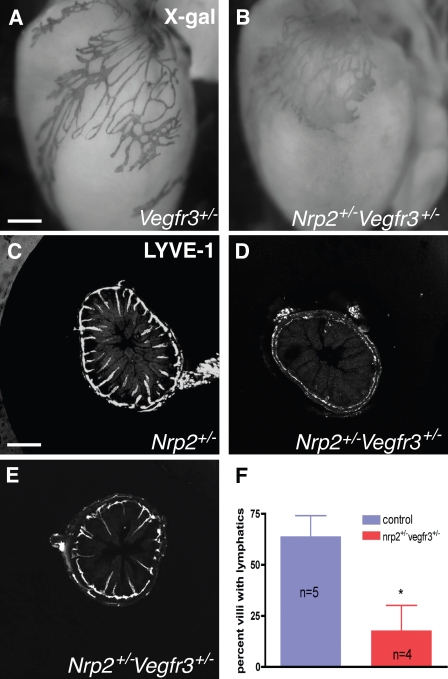

We next examined the small intestine and hearts of the nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− and nrp2−/− mice. In those tissues, sprouting and coverage of the lymphatics only begins at birth, and the effects of antibody treatment could thus be expected to mirror mutation of nrp2 or genetic reduction of nrp2 and vegfr3 expression levels. In the heart, both nrp2−/− mice (Fig. S4) and nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− double heterozygotes showed reduced lymphatic vessel sprouting and lymphatic vessel enlargement compared with vegfr3+/LacZ (Fig. 8, A and B), a phenotype highly similar to the one observed after anti-Nrp2B treatment (Fig. 2, O and P).

Figure 8.

Tip cell abnormalities in nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice are similar to those obtained after anti-Nrp2B treatment. (A and B) X-gal staining of P5 hearts from mice of the indicated genotypes. Note regular branching of lymphatics in the vegfr3+/− heart (A) but enlarged, poorly branched vessels devoid of sprouting tips in the double-heterozygote heart (B). (C–F) Lymphatic sprouting defects in the small intestine at P4. LYVE-1–stained sections show presence of lymphatics in almost all villi of wild-type mice (C) but virtually no sprouts in most sections of the double-heterozygous mice (D). Only some sections show a portion of the villi-containing lymphatics (E), which are of normal length compared with wild type (C). (F) Quantification of the percentage of villi-containing lymphatics. *, P < 0.01. Error bars indicate SEM. Bars: (A and B) 210 µm; (C–E) 200 µm.

In the small intestine, both wild-type and nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice at P4 had a submucosal lymphatic plexus established (Fig. 8, C–E). However, nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice showed a striking reduction of the number of villi-containing sprouting lymphatics when compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 8, C–F). Interestingly, in a few sections of the double-heterozygote mice, some of the villi were already invaded by lymphatics (Fig. 8 E), and these appeared similar in length when compared with the wild-type villi (Fig. 8 C), which is consistent with the finding that anti-Nrp2B treatment affected the initial sprouting event but not sprout elongation. At P8, most of the villi in nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− had mature lacteals that appeared indistinguishable from the wild-type littermates (unpublished data), confirming that inhibition of Nrp2-VEGFR3 function selectively affected the initial sprout formation in this tissue but not subsequent growth of the sprouts.

Comparison of lymphatic vessel patterning in adult vegfr3+/− and nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice showed that double-heterozygote mice exhibited reduced lymph vessel branching in these organs (Fig. S4, F–K). Examination of functionality of lymph vessels in the ear skin using FITC dextran injection showed that although they were more poorly branched, lymph vessels in the double heterozygote were capable of transporting dextran (Fig. S4, J and K). Cellular junctional proteins were also observed to have similar distribution in both wild-type and nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice in patterns consistent with those previously described (Baluk et al., 2007), suggesting that cell–cell interactions were unaffected. This was also observed in cultured cells treated with anti-Nrp2B antibody (Fig. S3).

Finally, smooth muscle coverage of larger collecting lymphatic vessels was indistinguishable between wild-type and nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice, indicating that lymph vessel maturation occurred normally in these animals (unpublished data). Collectively, our analysis shows that nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice exhibit selective defects in lymphatic vessel sprouting and recapitulate inhibition of Nrp2 by anti-Nrp2B.

Discussion

The lymphatic system regulates fluid homeostasis, immune system function, and is involved in initiation of tumor cell dissemination or metastasis for many solid tumor types. As such, elucidating the molecular mediators of lymphatic development is of significant importance. Our recent studies have implicated Nrp2 as a modulator of lymphangiogenesis both in the context of development and tumor biology (Yuan et al., 2002; Caunt et al., 2008). The results presented in this study show that in vivo modulation of Nrp2, either by genetic or pharmacologic means, results in disruption of lymphatic sprout formation by altering tip cell behavior. We further show that Nrp2 genetically interacts with VEGFR3 and not VEGFR2, indicating that Nrp2 partners with VEGFR3 to modulate lymphatic vessel sprouting.

Nrp2 is necessary for selective aspects of VEGF-C–mediated lymphangiogenesis

VEGF-C has been implicated in many aspects of lymphangiogenesis, including LEC survival, proliferation and migration, vessel growth, and the formation of vessels/vascular structures by signaling through VEGFR3 (Alitalo et al., 2005). However, proteolytically processed VEGF-C can also bind to VEGFR2 (Joukov et al., 1997), which is also expressed on lymph vessels and has been implicated in lymphangiogenesis (Hong et al., 2004; Goldman et al., 2007). Additionally, Nrp2 has been shown to be a VEGF-C coreceptor without any inherent signaling role (Karkkainen et al., 2001; Favier et al., 2006; Kärpänen et al., 2006). Primarily, Nrp2 has been proposed to function to augment signaling of VEGF-C via the receptor tyrosine kinases VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 (Favier et al., 2006). Indeed, inhibition of Nrp2 function in vitro results in a reduction in VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 phosphorylation by VEGF-C (Caunt et al., 2008). Thus, one might predict that inhibition of Nrp2 should result in modest reduction of all of the VEGF-C–mediated lymphangiogenic activities attributed to VEGF-C. In fact, we show that Nrp2 plays a role in only a specific aspect of lymphangiogenesis: sprout formation. Furthermore, we assign a more specific role to Nrp2, preventing tip cell stalling and retraction, thereby modulating lymphatic endothelial tip cell stability. In contrast, stalk cell behavior largely appears unaffected by Nrp2 inhibition. These findings are consistent with the observation that Nrp2 protein is enriched in cells at the leading tip of growing lymphatic sprouts (Caunt et al., 2008) in tip cell filopodia and that VEGF-C–AP more strongly stains lymphatic tip cells (Fig. S5). A selective role in modulating some but not all aspects of VEGF-C biology has been previously noted (Caunt et al., 2008), but this is the first study to associate a cellular basis for this observation. This also provides a biological basis for the previously described differential activities of VEGF family ligands that selectively activate either VEGFR2 or VEGFR3. Ligands that selectively activate VEGFR3 but not VEGFR2 induce lymphatic sprouting, whereas ligands that selectively activate VEGFR2 but not VEGFR3 lead only to enlargement of lymphatic capillaries but fail to induce sprouting (Veikkola et al., 2001; Wirzenius et al., 2007).

The molecular basis for Nrp2’s selective action in sprouting lymphatic tips is unclear. It is possible that Nrp2 provides functionality to specifically modulate tip cell extension, potentially by conveying additional molecular mediators to the VEGFR complex. Consistent with this, Nrp2 intracellular domain interacts with neuropilin-interacting protein (also known as synectin), a PDZ domain–containing protein that has been implicated in cell adhesion (Cai and Reed, 1999). _Synectin_-deficient mice show defects in arterial branching (Chittenden et al., 2006) and lymphatic vessel sprouting, which is similar to the ones described in this study (M. Simons, personal communication), suggesting that Nrp2–synectin interaction in growing lymphatic vessel tips could mediate sprouting downstream of VEGFR3. Additionally, neuropilins are known to interact with many membrane-associated proteins that have been implicated in cellular migratory and cell extension behaviors, including integrins and plexins (Cheng et al., 2001; Bagri et al., 2003; Fukasawa et al., 2007; Pan et al., 2008; Serini et al., 2008; Uniewicz and Fernig, 2008; Valdembri et al., 2009). As anti-Nrp2B is known to inhibit Nrp2 interaction with the VEGFR signaling complex (Caunt et al., 2008), inhibition of Nrp2 in this scenario could result in selective modulation of tip cell extension.

Nrp2 interacts with VEGFR3 to promote lymphatic sprouting

Lymphatic development is unaltered in nrp2+/−vegfr2+/− trans-heterozygous mutant mice. In contrast, although both single-heterozygous mutant mice have normal lymphatic development, the nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− trans-heterozygous mutants have a dramatic lymphangiogenesis defect, phenocopying in vivo pharmacologic inhibition with anti-Nrp2 antibodies and the _nrp2_-null mutant phenotype. This indicates that nrp2 genetically interacts with VEGFR3 but not VEGFR2. Thus, although Nrp2 can interact with both VEGFRs in vitro (Favier et al., 2006) and both VEGFRs are present on lymphatic endothelial cells during development in vivo, the primary VEGFR that Nrp2 interacts with to modulate lymphatic sprouting is VEGFR3. Although Nrp2 can clearly augment VEGF-C–mediated activation of both VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 in vitro in cellular assays (Caunt et al., 2008), VEGFR2 appears to play a more limited role in developing lymphatics in vivo. In addition, lymphatic vessels in vivo bind VEGF-C strongly and VEGF-A more weakly (Fig. S5; Lymboussaki et al., 1999). These results indicate that despite VEGFR2 expression, binding of VEGF-A to LECs is inefficient, whereas VEGF-C readily binds lymphatic vessels. Differential binding of VEGF-A and -C to endothelial cells might be regulated by the presence of additional coreceptors, such as Nrp1 and Nrp2 on microvessels and lymphatic vessels, respectively. Whether VEGFR3 is specifically assigned to tip cell extension is presently unclear, but recent studies have specifically implicated VEGFR3 in tip cell–associated biology even in blood vascular endothelial cells (Padera and Jain, 2008; Tammela et al., 2008). Interestingly, the role of Nrp2 was not addressed in those studies. It is also noteworthy that anti-Nrp2B specifically inhibits Nrp2’s role as a VEGF-C coreceptor while preserving Nrp2’s role as a semaphorin coreceptor (Caunt et al., 2008). It also does not affect the binding of other ligands that have been described to interact with Nrp2, including FGFs and hepatocyte growth factor (Caunt et al., 2008). However, the key lymphatic phenotype of the nrp2_-null mice and nrp2+/−_vegfr3+/− trans-heterozygous mice is phenocopied by treatment with the anti-Nrp2B antibody. This suggests that Nrp2’s role as a VEGF-C coreceptor is central to mediating lymphatic sprouting and that its role as a coreceptor for other ligands, including those that have been implicated in lymphangiogenesis such as hepatocyte growth factor (Jiang et al., 2005; Kajiya et al., 2005; Cao et al., 2006; Sulpice et al., 2008), is not significant for developmental lymphatic biology.

Tip cell extension in the lymphatic system

The biological phenomenon of sprouting in general, and more specifically tip cell extension, is incompletely understood. It is likely to involve the interplay between negative and positive regulators as in other systems that rely on branching morphogenesis (Horowitz and Simons, 2008). Within the vascular system, lymphatic vessels exhibit several unique characteristics, including the fact that some of the tips remain blind ended throughout life and develop functional specializations that allow fluid entry (Baluk et al., 2007). Currently, much of our limited understanding of vessel sprout formation derives from studies of developing blood vessels, and this is also true of tip cell behavior (for review see Suchting et al., 2007). Thus, modulation of lymphatic vessel morphogenesis and sprouting in particular is poorly understood, and the generalizability of this process to other systems that branch is also unclear. Based on in vitro and in vivo analyses of developing lymphatics, it was postulated that VEGF-C would be a positive regulator, but the mechanism by which it acts was not known. We show that Nrp2 plays the central role in modulating lymphatic tip cell activity to drive this behavior. Interestingly, inhibition of Nrp2 does not affect the number of sprout initiation events. Instead, it increases the frequency at which these sprouts stall/retract, suggesting that that Nrp signaling is required to fully allow sprout extension to manifest. The biochemical basis for this remains unclear and may involve the modulation of cytoskeletal elements by Rho family GTPases, although not observed in the two-dimentional cultured LECs evaluated in this study. Additionally, whether this is also the case in other vessels and other branching systems, more broadly, is yet to be determined.

From a therapeutic perspective, modulation of tip cell biology and sprouting has several distinct advantages. It allows the targeting of newly growing vessels, although allowing mature quiescent vessels to remain unaffected. This is in contrast to modulation of growth factors that may be potential survival factors: modulation of these would result in targeting of normal quiescent vessels as well, with the possibility of undesirable toxicity.

In summary, our work provides novel insight into the central role that Nrp2, an axon guidance receptor, plays in lymphatic vessel development. We show for the first time that the cellular basis for the defect in lymphangiogenesis is a selective inhibition of sprout formation, modulating lymphatic endothelial tip cell extension and preventing tip cell stalling and retraction. We also show that Nrp2 interacts genetically with VEGFR3, confirming previous theories and providing the mechanistic basis for how these two receptors act in concert to drive lymphatic sprouting.

Materials and methods

Mice

For pharmacologic inhibitory experiments, neonatal CD1 mice were injected intraperitoneally with monoclonal antibodies at 40 mg/kg. Pharmacokinetic analysis and dose-ranging in vivo experiments (Fig. S1) showed that maximal efficacy was noted at 20 mg/kg with no additional inhibition of lymphatic sprouting at higher doses to 100 mg/kg. Thus, anti-Nrp2B was dosed at 40 mg/kg to ensure complete saturation and inhibition of Nrp2. The injections were performed on P1, 3, and 5 unless otherwise noted. For analysis of effects on mature lymphatics, 6–8-wk-old mice were treated at 100 mg/ml twice a week for 25 wk. Mice were sacrificed, and the skin, pancreata, and intestines were collected and stained for LYVE-1.

C57/BL6 nrp2vegfr3 or nrp2vegfr2 double-heterozygous mice were generated by interbreeding nrp2+/− mice (Giger et al., 2000) with vegfr3+/lacZ (Dumont et al., 1998) or vegfr2+/egfp mice. For vegfr2+/egfp mice, a targeting construct was prepared to allow insertion of an EGFP reporter followed by poly(A) signal and a loxP-flanked neomycin selection cassette into the initiation codon within exon 1 of the flk1 locus. We retained all sequence elements of the locus to avoid deletion of potential regulatory elements. Linearized targeting vector was electroporated into mouse embryonic stem (ES) cell line E14Tg2a, and the targeted clones were selected by Southern blotting. The floxed selection cassette in the vector was excised by Cre-mediated recombination in targeted ES cells by transient transfection with a Cre-expressing plasmid. Chimeric mice were produced after injection of correctly targeted ES cells into blastocysts and were back crossed to the C57/BL6 background for at least nine generations. The Flk1-GFP embryos showed a typical vascular pattern of expression.

Colonies of nrp2+/−, vegfr2+/egfp, and vegfr3+/lacZ mice were maintained by breeding heterozygous males with wild-type C57/BL6 females (Charles River). Genotyping was performed using PCR beads (Ready-To-Go; GE Healthcare).The following primers were used for genotyping nrp2: forward primer 1, 5′-CGCATTGCATCAGCCATGAT-3′; forward primer 2, 5′-TCAGGACACGAAGTGAGAAG-3′; and reverse primer, 5′-GGGAGATGTGTTCTGCTTCA-3′. The following primers were used for genotyping vegfr3: forward primer 1, 5′-GCGGTCTGAAAGGAAGACAG-3′; forward primer 2, 5′-ACTGGCAGATGCACGGTTAC-3′; reverse primer 1, 5′-ACACCAAGCCAAGCTCAAGT-3′; and reverse primer 2, 5′-GTT GCACCACAGATGAAACG-3′. vegfr2+/egfp mice were identified by fluorescence.

Immunohistochemistry

For whole-mount staining, tissues were fixed in 4% PFA and blocked overnight in blocking buffer (PBS, 5% goat serum, 0.3% Triton X-100, and 0.2% BSA). Tissues were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies in blocking buffer (biotinylated or unconjugated anti–mouse VEGFR3 [R&D Systems], anti–mouse LYVE-1 [R&D Systems or Angiobio], anti–mouse podoplanin [R&D Systems], phospho–histone H3 [Abcam], anti–PECAM-1 [BD], and VE-cadherin [Cell Signaling Technology]). Tissues were washed in PBS and 0.3% Triton X-100 and incubated overnight with fluorescent streptavidin (Cy2 or Cy3; GE Healthcare) or species-specific fluorescent secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488 or 555; 1:200; Invitrogen). For tail whole-mount preparation, tails were dissected, a longitudinal cut was made down the dorsal length of the tail, and the tail bone was removed. Tails were incubated with 20 mM EDTA and PBS for 4 h at 37°C to remove the epidermis and were fixed with 4% PFA for 3 h at room temperature. For immunocytochemistry on LECs, cells were grown to confluence and serum starved overnight. They were incubated in serum-free media containing 0.1% BSA (unstimulated) or 200 ng/ml VEGF-C (stimulated) in the presence or absence of 40 mg/ml anti-Nrp2B. Cells were stained with antibodies to LYVE-1, VE-cadherin and tubulin (Cell Signaling Technology), or Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin (Invitrogen).

Mouse VEGF-C–AP and VEGF-A–AP constructs (provided by C. Ruiz de Almodovar, Vesalius Research Center, Leuven, Belgium) were obtained by cloning cDNA encoding mouse VEGF-A and VEGF-C into pAPtag-5 vector (GenHunter Corporation). To produce AP-tagged proteins, HEK293T cells were transfected using Lipofectamine plus (Invitrogen). Supernatant was collected after 48 h, and AP concentration was measured using _p_-nitrophenyl phosphate tablets (Sigma-Aldrich). VEGF-A– and VEGF-C–AP-binding experiments were performed on cryostat sections of tails from p6 mice or diaphragms as described previously (Feiner et al., 1997). In brief, fresh frozen tissue sections were postfixed in precooled methanol at −20°C for 10 min and washed with TBS, blocked with TBS containing 10% calf serum for 15 min, and incubated with AP ligand fusion protein diluted to 600 pM in TBS containing 10% calf serum for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were rinsed with TBS and fixed with 60% acetone, 3% PFA, and 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.0, for 5 min and washed with TBS. Endogenous AP activity was heat inactivated by incubating the sections at 65°C for 3 h, and sections were processed for AP in 100 mM Tris, pH 9.5, 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween 20, 0.33 mg/ml nitroblue tetrazolium, and 0.05 mg/ml BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate) overnight at room temperature.

In vitro assays

For the in vitro sprouting assay, dextran-coated microcarrier beads (Cytodex 3; GE Healthcare) were incubated with LECs (400 cells/bead) in EGM-2MV (Lonza), which contains 200 ng/ml VEGF-C, overnight at 37°C. To induce clotting, 0.5 ml cell-coated beads in PBS with 2.5 µg/ml fibrinogen (200 beads/ml) was added into one well of a 24-well tissue culture plate containing 0.625 U thrombin and incubated for 5 min at room temperature and for 20 min at 37°C. The clot was equilibrated in EMG-2MV for 30 min at 37°C. The medium was replaced with EGM-2–containing skin fibroblast cells (Detroit 551; 20,000 cells/ml). Antibodies were added to each well, and the assay was monitored for 14 d with a change in medium every 2–3 d. Images of the beads were captured by an inverted microscope, and the number of sprouts per bead was counted for 10 beads per condition. The length of the sprouts was determined in ImageJ (National Institutes of Health).

Time-lapse image series were acquired with a live cell imaging system (Axio Observer; Carl Zeiss, Inc.) controlled by SlideBook (version 4.2.012RC11; Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Inc.). Four beads per well were imaged at 20× magnification (0.62 × 0.62 µm/pixel). The xy position of each bead was manually defined and stored, and a z stack (20 slices with 5-µm step size) was acquired at 20-min intervals for 24 h. Sprout dynamics were quantified manually from the resulting 4D time series for a minimum of three wells per condition.

For analysis of Rho family GTPase, LECs were grown to confluence and serum starved overnight. They were then incubated in serum-free media containing 0.1% BSA (unstimulated) or 200 ng/ml VEGF-C (stimulated) in the presence or absence of 40 µg/ml anti-Nrp2B. After 10 min of stimulation, cells were evaluated for activated Rho, Rac, or Cdc42 using a commercial kit (Cell Biolabs). VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 activation levels were assessed as follows: confluent human umbilical vein endothelial cells were stimulated for 10 min with 200 ng/ml VEGF-C in the presence or absence of control (anti-ragweed) or anti-Nrp2B antibodies. The cells were lysed and assayed, as many mediators know to play a role in VEGFR signaling. VEGFR2 activation was evaluated using total VEGFR2 and phospho-VEGFR2 ELISA assays (DuoSet IC ELISA kit; R&D Systems). VEGFR3 activation was evaluated using a kinase receptor activation assay with a VEGFR3-293 cell line. In brief, stable 293 cell lines expressing full-length Flag-tagged human VEGFR3 were assayed for receptor phosphorylation after stimulation. 5 × 104 cells were starved overnight (DME with 0.1% BSA) and stimulated with 40 ng/ml VEGF-A (Genentech) or 200 ng/ml VEGF-C (Genentech) for 10 min. Cells were lysed in PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 and sodium orthovanadate. ELISA plates were coated with capture Flag antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). The plates were coated overnight (PBS + 1 µg/ml antibody) and blocked (PBS + 0.5% BSA) for 1 h. After three washes (PBS + 0.05% Tween 20), lysates were added for 2 h and washed three times followed by the addition of phospho-detection antibody 4G10 (Millipore) for 2 h. Detection was performed with HRP antibody (GE Healthcare) and tetramethylbenzidine substrate.

FACS

LECs were harvested with enzyme-free cell dissociation buffer (Invitrogen) and incubated with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-VEGFR1, anti-VEGFR2, and anti-VEGFR3 (BD) for 2 h at 4°C at 1:100 in FACS buffer (PBS, 2% FBS, 2 mM EDTA, and 0.1% sodium azide) containing 5% normal mouse serum, 2% normal rat serum, and 10 µg/ml human IgG. Cells were washed with FACS buffer, and data were analyzed with the FACSCalibur system (BD).

Quantification of LEC replication

After phospho–histone H3 and LYVE-1 double staining, samples were mounted, and three to five fields per animal were imaged on a 20× confocal microscope (SP5; Leica). Only phospho–histone H3-positive cells within lymphatic vessels were counted. Images were processed using Photoshop (Adobe) and ImageJ to quantify vessel surface area and normalize replication index.

Quantification of lymphatic vessel branch points

The dorsal skin surrounding the forelimbs from P0 pups was stained for VEGFR3, LYVE-1, or X-gal (Invitrogen), imaged on a 4× stereomicroscope, and branch points were counted manually. Only skin samples from the dorsal part of the pup surrounding the forelimb were quantified to ensure reproducibility between pups.

Quantitative PCR

Hearts were isolated from P5 wild-type, nrp-2+/−, vegfr2+/egfp, and nrp-2+/−vegfr3+/lacz mice, and total mRNA was extracted using a total RNA extraction kit (MiniKit; QIAGEN). Four independent samples were analyzed for each genotype. RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript III (Invitrogen) and random primers according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR was performed with a real-time PCR detection system (iCycler; Bio-Rad Laboratories) using SYBR green PCR master mix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and standard thermocycler conditions. PCRs were performed in duplicate in a total volume of 25 µl using 1 µl cDNA. Each sample was analyzed for β-actin to normalize for RNA input amounts and to perform relative quantifications. Levels of each transcript in one wild-type animal were set at 1. The following primers were used: mouse flk1, 5′-GCCCTGCTGTGGTCTCACTAC-3′ and 5′-GCCCATTCGATCCAGTTTCA-3′; mouse Pecam1, 5′-CAAGCAAAGCAGTGAAGCTG-3′ and 5′-TCTAACTTCGGCTTGGGAAA-3′; and mouse β-actin, 5′-TGTTACCAACTGGGACGACA-3′ and 5′-GGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTCAAA-3′. Mouse flt4, Lyve1, podoplanin, prox1, and nrp2 genes were detected using predesigned primer pairs (QuantiTect primer assays; QIAGEN). Melting curve analysis showed a single, sharp peak with the expected temperature melting for all samples.

Image acquisition and analysis

For Figs. 1 (N and R), 5, 7, 8 (C–E), S2, and S3, tissues stained with Alexa Fluor 555 and 488 (Invitrogen) were used mounted in type F immersion liquid (Leica), and images were captured with a confocal microscope (Sp5; Leica) at room temperature with acquisition software (LAS AF; Leica) and a 10× NA 0.3 Plan Fluotar lens (HC; Leica), a 20× NA 0.7 Plan Apo lens (HCX CS; Leica), and a 40× NA 1.4 Plan Apo lens (HCX CS; Leica).

For Figs. 1 (all panels except panels N, O, R, and S), 2 (A–D, G, and H), 3, and S1, tissues stained with Alexa Fluor 555 and 488 were used mounted in Fluoromount G (EMS Sciences), and images were captured with an upright microscope (Axioplan2; Carl Zeiss, Inc.) at room temperature with a charge-coupled device (HQ2; Photometrics) camera using SlideBook (version 5.0) software and 5×, 10×, and 20× objectives with NA 0.16, 0.45, and 0.75, respectively (Carl Zeiss, Inc.).

For Figs. 2 (M–P), 6 (A–D), 8 (A and B), and S4 (A–K), tissues stained with Alexa Fluor 555 and 488 were wet mounted in PBS, and images were captured with a microscope (FX MZ FL111 DFC 340; Leica) at room temperature on a compact flash camera (CoolSNAP; Photometrics) with acquisition software (Fire Cam; Leica) and a 10× HC Plan Fluotar NA 0.3 lens, a 20× HCX Plan Apo CS NA 0.7 lens, and a 40× NA 1.4 HCX Plan Apo CS lens.

For Figs. 6 (E and F), S4 (L–O), and S5, tissues were chromogenically stained or stained with Alexa Fluor 555 and 488, were mounted in DakoCytomation mounting media (Dako), and images were captured with a microscope (BX50; Olympus) at room temperature on a compact flash camera (CoolSNAP; Photometrics) with acquisition software (Iplab 3.2.4; Scanalytics, Inc.) and a 4× NA 0.16 UPlan Apo lens, a 10× NA 0.3 UPlan FL lens, and a 20× NA 0.5 UPlan FL lens. Imaris software (version x64; Bitplan) was used to generate 3D surface renderings of z-stack 40× confocal images depicted in Fig. 1 (N and R) to generate the images in Fig. 1 (O and S), respectively.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows concentration dependence of anti-Nrp2B and analysis of mature lymphatics in control and anti-Nrp2B–treated mice. Fig. S2 shows expression of Nrp2, VEGFR2, and VEGFR3 in developing lymphatics in vitro and in vivo. Fig. S3 shows effects of Nrp2 inhibition on cytoskeletal behavior, VEGFR activation, and cellular junctions in vitro and in vivo. Fig. S4 shows analysis of lymphatic structure and function in nrp2_−/− and nrp2+/−_vegfr3+/− mice. Fig. S5 shows that VEGF-C–AP selectively binds to lymphatic vessels and sprouts. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200903137/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alex Kolodkin and David Ginty of Johns Hopkins Medical Institute (Baltimore, MD) for their generous gifts of Nrp2 knockout mice and Annie Boisquillon and Jeremy Teillon for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Neuroscience, blanc), Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer, Institut National du Cancer, Institut de France (Cino del Duca), and the European Community (LSHG-CT-2004-503573). Judy Mak, Maresa Caunt, Ian Kasman, Jillian Silva, Alexander Koch, and Anil Bagri are full-time employees of Genentech, Inc.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

AP

alkaline phosphatase

ECD

extracellular domain protein

ES

embryonic stem

LEC

lymphatic endothelial cell

LRC

lymphatic ring complex

Nrp2

neuropilin-2

VEGFR

VEGF receptor

References

- Affolter M., Caussinus E. 2008. Tracheal branching morphogenesis in Drosophila: new insights into cell behaviour and organ architecture. Development. 135:2055–2064 10.1242/dev.014498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alitalo K., Tammela T., Petrova T.V. 2005. Lymphangiogenesis in development and human disease. Nature. 438:946–953 10.1038/nature04480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagri A., Cheng H.J., Yaron A., Pleasure S.J., Tessier-Lavigne M. 2003. Stereotyped pruning of long hippocampal axon branches triggered by retraction inducers of the semaphorin family. Cell. 113:285–299 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00267-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluk P., Fuxe J., Hashizume H., Romano T., Lashnits E., Butz S., Vestweber D., Corada M., Molendini C., Dejana E., McDonald D.M. 2007. Functionally specialized junctions between endothelial cells of lymphatic vessels. J. Exp. Med. 204:2349–2362 10.1084/jem.20062596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H., Reed R.R. 1999. Cloning and characterization of neuropilin-1-interacting protein: a PSD-95/Dlg/ZO-1 domain-containing protein that interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of neuropilin-1. J. Neurosci. 19:6519–6527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao R., Björndahl M.A., Gallego M.I., Chen S., Religa P., Hansen A.J., Cao Y. 2006. Hepatocyte growth factor is a lymphangiogenic factor with an indirect mechanism of action. Blood. 107:3531–3536 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caunt M., Mak J., Liang W.C., Stawicki S., Pan Q., Tong R.K., Kowalski J., Ho C., Reslan H.B., Ross J., et al. 2008. Blocking neuropilin-2 function inhibits tumor cell metastasis. Cancer Cell. 13:331–342 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Chédotal A., He Z., Goodman C.S., Tessier-Lavigne M. 1997. Neuropilin-2, a novel member of the neuropilin family, is a high affinity receptor for the semaphorins Sema E and Sema IV but not Sema III. Neuron. 19:547–559 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80371-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Bagri A., Zupicich J.A., Zou Y., Stoeckli E., Pleasure S.J., Lowenstein D.H., Skarnes W.C., Chédotal A., Tessier-Lavigne M. 2000. Neuropilin-2 regulates the development of selective cranial and sensory nerves and hippocampal mossy fiber projections. Neuron. 25:43–56 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80870-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H.J., Bagri A., Yaron A., Stein E., Pleasure S.J., Tessier-Lavigne M. 2001. Plexin-A3 mediates semaphorin signaling and regulates the development of hippocampal axonal projections. Neuron. 32:249–263 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00478-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittenden T.W., Claes F., Lanahan A.A., Autiero M., Palac R.T., Tkachenko E.V., Elfenbein A., Ruiz de Almodovar C., Dedkov E., Tomanek R., et al. 2006. Selective regulation of arterial branching morphogenesis by synectin. Dev. Cell. 10:783–795 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini F. 2006. Renal branching morphogenesis: concepts, questions, and recent advances. Differentiation. 74:402–421 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00106.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cueni L.N., Detmar M. 2006. New insights into the molecular control of the lymphatic vascular system and its role in disease. J. Invest. Dermatol. 126:2167–2177 10.1038/sj.jid.5700464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont D.J., Jussila L., Taipale J., Lymboussaki A., Mustonen T., Pajusola K., Breitman M., Alitalo K. 1998. Cardiovascular failure in mouse embryos deficient in VEGF receptor-3. Science. 282:946–949 10.1126/science.282.5390.946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favier B., Alam A., Barron P., Bonnin J., Laboudie P., Fons P., Mandron M., Herault J.P., Neufeld G., Savi P., et al. 2006. Neuropilin-2 interacts with VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 and promotes human endothelial cell survival and migration. Blood. 108:1243–1250 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiner L., Koppel A.M., Kobayashi H., Raper J.A. 1997. Secreted chick semaphorins bind recombinant neuropilin with similar affinities but bind different subsets of neurons in situ. Neuron. 19:539–545 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80370-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FranÇois M., Caprini A., Hosking B., Orsenigo F., Wilhelm D., Browne C., Paavonen K., Karnezis T., Shayan R., Downes M., et al. 2008. Sox18 induces development of the lymphatic vasculature in mice. Nature. 456:643–647 10.1038/nature07391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukasawa M., Matsushita A., Korc M. 2007. Neuropilin-1 interacts with integrin beta1 and modulates pancreatic cancer cell growth, survival and invasion. Cancer Biol. Ther. 6:1173–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt H., Golding M., Fruttiger M., Ruhrberg C., Lundkvist A., Abramsson A., Jeltsch M., Mitchell C., Alitalo K., Shima D., Betsholtz C. 2003. VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J. Cell Biol. 161:1163–1177 10.1083/jcb.200302047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt H., Ruhrberg C., Abramsson A., Fujisawa H., Shima D., Betsholtz C. 2004. Neuropilin-1 is required for endothelial tip cell guidance in the developing central nervous system. Dev. Dyn. 231:503–509 10.1002/dvdy.20148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger R.J., Urquhart E.R., Gillespie S.K., Levengood D.V., Ginty D.D., Kolodkin A.L. 1998. Neuropilin-2 is a receptor for semaphorin IV: insight into the structural basis of receptor function and specificity. Neuron. 21:1079–1092 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80625-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger R.J., Cloutier J.F., Sahay A., Prinjha R.K., Levengood D.V., Moore S.E., Pickering S., Simmons D., Rastan S., Walsh F.S., et al. 2000. Neuropilin-2 is required in vivo for selective axon guidance responses to secreted semaphorins. Neuron. 25:29–41 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80869-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman J., Rutkowski J.M., Shields J.D., Pasquier M.C., Cui Y., Schmökel H.G., Willey S., Hicklin D.J., Pytowski B., Swartz M.A. 2007. Cooperative and redundant roles of VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 signaling in adult lymphangiogenesis. FASEB J. 21:1003–1012 10.1096/fj.06-6656com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagendoorn J., Padera T.P., Kashiwagi S., Isaka N., Noda F., Lin M.I., Huang P.L., Sessa W.C., Fukumura D., Jain R.K. 2004. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase regulates microlymphatic flow via collecting lymphatics. Circ. Res. 95:204–209 10.1161/01.RES.0000135549.72828.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y.K., Lange-Asschenfeldt B., Velasco P., Hirakawa S., Kunstfeld R., Brown L.F., Bohlen P., Senger D.R., Detmar M. 2004. VEGF-A promotes tissue repair-associated lymphatic vessel formation via VEGFR-2 and the alpha1beta1 and alpha2beta1 integrins. FASEB J. 18:1111–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz A., Simons M. 2008. Branching morphogenesis. Circ. Res. 103:784–795 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.181818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeltsch M., Kaipainen A., Joukov V., Meng X., Lakso M., Rauvala H., Swartz M., Fukumura D., Jain R.K., Alitalo K. 1997. Hyperplasia of lymphatic vessels in VEGF-C transgenic mice. Science. 276:1423–1425 10.1126/science.276.5317.1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W.G., Davies G., Martin T.A., Parr C., Watkins G., Mansel R.E., Mason M.D. 2005. The potential lymphangiogenic effects of hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Mol. Med. 16:723–728 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joukov V., Pajusola K., Kaipainen A., Chilov D., Lahtinen I., Kukk E., Saksela O., Kalkkinen N., Alitalo K. 1996. A novel vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF-C, is a ligand for the Flt4 (VEGFR-3) and KDR (VEGFR-2) receptor tyrosine kinases. EMBO J. 15:290–298 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joukov V., Sorsa T., Kumar V., Jeltsch M., Claesson-Welsh L., Cao Y., Saksela O., Kalkkinen N., Alitalo K. 1997. Proteolytic processing regulates receptor specificity and activity of VEGF-C. EMBO J. 16:3898–3911 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajiya K., Hirakawa S., Ma B., Drinnenberg I., Detmar M. 2005. Hepatocyte growth factor promotes lymphatic vessel formation and function. EMBO J. 24:2885–2895 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalima T.V. 1971. The structure and function of intestinal lymphatics and the influence of impaired lymph flow on the ileum of rats. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 10:1–87 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkkainen M.J., Saaristo A., Jussila L., Karila K.A., Lawrence E.C., Pajusola K., Bueler H., Eichmann A., Kauppinen R., Kettunen M.I., et al. 2001. A model for gene therapy of human hereditary lymphedema. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:12677–12682 10.1073/pnas.221449198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkkainen M.J., Haiko P., Sainio K., Partanen J., Taipale J., Petrova T.V., Jeltsch M., Jackson D.G., Talikka M., Rauvala H., et al. 2004. Vascular endothelial growth factor C is required for sprouting of the first lymphatic vessels from embryonic veins. Nat. Immunol. 5:74–80 10.1038/ni1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpanen T., Alitalo K. 2008. Molecular biology and pathology of lymphangiogenesis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 3:367–397 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärpänen T., Heckman C.A., Keskitalo S., Jeltsch M., Ollila H., Neufeld G., Tamagnone L., Alitalo K. 2006. Functional interaction of VEGF-C and VEGF-D with neuropilin receptors. FASEB J. 20:1462–1472 10.1096/fj.05-5646com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lymboussaki A., Olofsson B., Eriksson U., Alitalo K. 1999. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF-C show overlapping binding sites in embryonic endothelia and distinct sites in differentiated adult endothelia. Circ. Res. 85:992–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maby-El Hajjami H., Petrova T.V. 2008. Developmental and pathological lymphangiogenesis: from models to human disease. Histochem. Cell Biol. 130:1063–1078 10.1007/s00418-008-0525-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkinen T., Jussila L., Veikkola T., Karpanen T., Kettunen M.I., Pulkkanen K.J., Kauppinen R., Jackson D.G., Kubo H., Nishikawa S., et al. 2001. Inhibition of lymphangiogenesis with resulting lymphedema in transgenic mice expressing soluble VEGF receptor-3. Nat. Med. 7:199–205 10.1038/84651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver G., Srinivasan R.S. 2008. Lymphatic vasculature development: current concepts. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1131:75–81 10.1196/annals.1413.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padera T.P., Jain R.K. 2008. VEGFR3: a new target for antiangiogenesis therapy? Dev. Cell. 15:178–179 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H., Wanami L.S., Dissanayake T.R., Bachelder R.E. 2008. Autocrine semaphorin3A stimulates alpha2 beta1 integrin expression/function in breast tumor cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 118:197–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serini G., Napione L., Bussolino F. 2008. Integrins team up with tyrosine kinase receptors and plexins to control angiogenesis. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 15:235–242 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3282fa745b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skobe M., Brown L.F., Tognazzi K., Ganju R.K., Dezube B.J., Alitalo K., Detmar M. 1999. Vascular endothelial growth factor-C (VEGF-C) and its receptors KDR and flt-4 are expressed in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J. Invest. Dermatol. 113:1047–1053 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00798.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soker S., Miao H.Q., Nomi M., Takashima S., Klagsbrun M. 2002. VEGF165 mediates formation of complexes containing VEGFR-2 and neuropilin-1 that enhance VEGF165-receptor binding. J. Cell. Biochem. 85:357–368 10.1002/jcb.10140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchting S., Freitas C., le Noble F., Benedito R., Breant C., Duarte A., Eichmann A. 2007. Negative regulators of vessel patterning. Novartis Found. Symp. 283:77–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulpice E., Plouët J., Bergé M., Allanic D., Tobelem G., Merkulova-Rainon T. 2008. Neuropilin-1 and neuropilin-2 act as coreceptors, potentiating proangiogenic activity. Blood. 111:2036–2045 10.1182/blood-2007-04-084269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammela T., Saaristo A., Holopainen T., Lyytikkä J., Kotronen A., Pitkonen M., Abo-Ramadan U., Ylä-Herttuala S., Petrova T.V., Alitalo K. 2007. Therapeutic differentiation and maturation of lymphatic vessels after lymph node dissection and transplantation. Nat. Med. 13:1458–1466 10.1038/nm1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]