Regulation of the inflammatory response in cardiac repair (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2013 Jun 22.

Abstract

Myocardial necrosis triggers an inflammatory reaction that clears the wound from dead cells and matrix debris, while activating reparative pathways necessary for scar formation. A growing body of evidence suggests that accentuation, prolongation or expansion of the post-infarction inflammatory response results in worse remodeling and dysfunction following myocardial infarction. This review manuscript discusses the cellular effectors and endogenous molecular signals implicated in suppression and containment of the inflammatory response in the infarcted heart. Clearance of apoptotic neutrophils, recruitment of inhibitory monocyte subsets and regulatory T cells, macrophage differentiation and pericyte/endothelial interactions may play an active role in restraining post-infarction inflammation. Multiple molecular signals may be involved in suppressing the inflammatory cascade. Negative regulation of toll-like receptor signaling, downmodulation of cytokine responses and termination of chemokine signals may be mediated through the concerted action of multiple suppressive pathways that prevent extension of injury and protect from adverse remodeling. Expression of soluble endogenous antagonists, decoy receptors, and post-translational processing of bioactive molecules may limit cytokine and chemokine actions. Interleukin (IL)-10, members of the Transforming Growth Factor (TGF)-β family, and pro-resolving lipid mediators (such as lipoxins, resolvins and protectins) may suppress pro-inflammatory signaling. In human patients with myocardial infarction, defective suppression and impaired resolution of inflammation may be important mechanisms in the pathogenesis of remodeling and in progression to heart failure. Understanding of inhibitory and pro-resolving signals in the infarcted heart and identification of patients with uncontrolled post-infarction inflammation and defective cardiac repair is needed to design novel therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: Resolution of inflammation, Myocardial infarction, Cytokine, Chemokine, Mononuclear cells

INTRODUCTION

Over the last thirty years, advanced coronary care and early reperfusion strategies have dramatically improved survival rates in patients suffering an acute myocardial infarction1. However, this impressive success has resulted in a larger pool of patients who, having survived the acute infarction, are at risk of developing heart failure2. Despite therapeutic advances, the risk of heart failure following myocardial infarction has remained high; in fact, some studies have suggested an increased incidence of post-infarction heart failure in recent decades that parallels the decreasing acute mortality rates. Development of heart failure following myocardial infarction is closely associated with profound alterations in cardiac geometry, function and structure, also referred to as “ventricular remodeling”. The molecular and cellular changes in the remodeling heart affect both the area of necrosis and the non-infarcted segments of the ventricle and manifest clinically as increased chamber dilation and sphericity, myocardial hypertrophy, and worsened cardiac function3. Cardiac remodeling is linked to heart failure progression and is associated with poor prognosis in patients surviving a myocardial infarction4. The extent of post-infarction remodeling is dependent on the size of the infarct and on the quality of cardiac repair5.

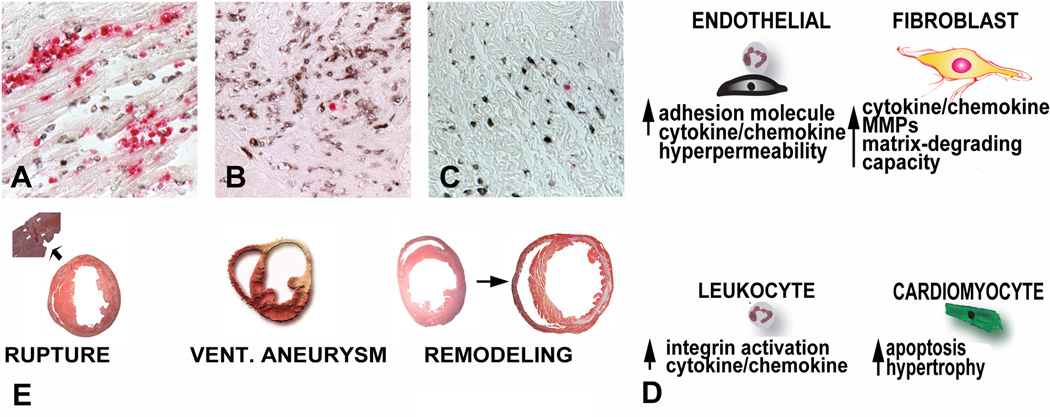

The adult human heart contains approximately 4–5 billion cardiomyocytes; because the myocardium has negligible endogenous regenerative capacity, loss of a significant amount of cardiac muscle ultimately leads to formation of a scar. Cardiac repair is dependent on a superbly orchestrated inflammatory response that serves to clear the wound from dead cells and matrix debris, but also provides key molecular signals for activation of reparative cells. It is becoming increasingly apparent that timely repression and containment of inflammatory signals are needed to ensure optimal formation of a supportive scar in the infarcted area and to prevent development of adverse remodeling. Because even relatively subtle alterations in myocardial architecture, matrix composition and cellular phenotype profoundly affect chamber geometry and ventricular function, defects and aberrations in temporal and spatial regulation of the post-infarction inflammatory reaction may have catastrophic consequences (Figure 1). Excessive early inflammation may augment matrix degradation causing cardiac rupture. Prolongation of the inflammatory reaction may impair collagen deposition leading to formation of a scar with reduced tensile strength, thus increasing chamber dilation. Enhanced expression of pro-inflammatory mediators may activate pro-apoptotic pathways inducing further loss of cardiomyocytes. Finally defective containment of the inflammatory reaction may lead to extension of the inflammatory infiltrate into the non-infarcted myocardium enhancing fibrosis and worsening diastolic function. From an evolutionary perspective the inflammatory reaction to injury developed to protect organisms from the disastrous consequences of infectious pathogens. These evolutionary pressures may have resulted in prolonged and intense endogenous inflammatory responses that may be excessive for the delicate requirements of the injured myocardium.

Figure 1. The consequences of unrestrained inflammation in the infarcted heart.

Repair of the infarcted heart is dependent on timely suppression of the post-infarction inflammatory response and on resolution of the inflammatory infiltrate. A-C: Histopathologic illustration of induction, suppression and resolution of the post-infarction inflammatory response in a canine model. Dual immunohistochemical staining combines staining for Mac387 (red), a myeloid cell marker that labels neutrophils and monocytes (but not mature macrophages), serving as a measure of active leukocyte recruitment in inflamed tissues and staining for PM-2K, a mature macrophage marker that is not expressed in newly-recruited monocytes. After 24h of reperfusion abundant newly-recruited myeloid cells are identified in the infarct; however; their number decreases significantly after 7 days reflecting suppression of active inflammatory cell recruitment. At this stage, PM-2K+ mature macrophages are the predominant leukocyte type in the infarct. After 28 days of reperfusion resolution of the leukocyte infiltrate is noted. D: : Expected effects of uncontrolled and excessive inflammation on the cell types involved in cardiac repair. Prolongation or accentuation of the inflammatory reaction may result in increased leukocyte activation, enhanced adhesiveness and permeability of endothelial cells, acquisition of a matrix-degrading phenotype by fibroblasts and cardiomyocyte apoptosis. E: Impact of the cellular effects of overactive, prolonged or poorly-contained inflammation on the infarcted heart. Cardiac rupture, formation of ventricular aneurysms, increased dysfunction and adverse dilative remodeling could result from defective regulation of the post-infarction inflammatory response.

Initially believed to be a “passive event” related to the dissipation of the injurious insult, it is now widely accepted that inhibition and resolution of inflammation are biosynthetically active processes that requires recruitment of cellular effectors and activation of molecular mediators that suppress inflammation. Although extensive research has explored the mechanisms responsible for activation of the inflammatory reaction in the infarcted heart; the pathways involved in repression of inflammation have been neglected. This review manuscript will discuss the cellular effectors and molecular signals responsible for negative regulation, resolution and containment of inflammation in the infarcted myocardium. As the pathophysiology of repression of the post-infarction inflammatory response remains - to a large extent- “uncharted territory”, the manuscript will also discuss important molecular pathways that, on the basis of their fundamental properties in regulation of the immune response, may play an important role in the process, despite the absence of direct experimental data documenting their significance. Because of the importance of inflammatory and reparative mechanisms in cardiac remodeling, defects in resolution of inflammation may be responsible for remodeling, injury and heart failure in a large number of patients surviving a myocardial infarction. Emerging concepts on the significance of endogenous inhibitory pathways in cardiac repair may provide insight into the reasons for the failure of previous strategies targeting the inflammatory response in patients with myocardial infarction.

INITIATION OF THE POST-INFARCTION INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE

The predominant mechanism of cardiomyocyte death in the infarcted heart is coagulation necrosis, although apoptosis is also likely to contribute to cardiomyocyte loss. Cells dying by necrosis release their intracellular contents and initiate an intense inflammatory response by activating innate immune mechanisms. Beyond its traditional role as a “warning system” that allows the host to defend against pathogenic microorganisms by discriminating “self” from “non-self”, innate immunity also serves as a sophisticated molecular network that senses host-derived “danger signals” released by necrotic cells, or by damaged extracellular matrix, activating inflammatory pathways while remaining unresponsive to non-dangerous motifs.

In the infarcted myocardium several innate immune pathways are activated. Generation of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMP) by necrotic cells and matrix fragments activates membrane-bound Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs)6; the role of TLR signaling in post-ischemic inflammation has been recently reviewed in Circulation Research7. Other innate immune pathways including the High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE)8 and the complement system are also activated after necrotic myocardial injury and participate in the early steps of the inflammatory response following infarction. As the antioxidant defenses in the infarcted heart are overwhelmed, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated and induce inflammatory signals while exerting direct inhibitory effects on myocardial function.

Signal transduction from activation of innate immune pathways converges on activation of Nuclear Factor (NF)-κB that drives production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The multifaceted role of NF-κB in cardiac injury has been recently reviewed in Circulation Research9. As prominent and early mediators of inflammation, pro-inflammatory cytokines critically regulate the response to cardiac injury. Interleukin (IL)-1 signaling mediates chemokine synthesis in the infarcted myocardium and stimulates infiltration of the infarct with leukocytes10. Generation of active IL-1β requires processing of pro-IL-1β, an inactive precursor, by the converting enzyme caspase-1. Caspase-1 activity is tightly regulated within multiprotein complexes termed “inflammasomes”; these molecular platforms control maturation and processing of IL-1β11. Inflammasome activation in the infarcted myocardium is localized in both leukocytes and resident fibroblasts and drives IL-1-mediated inflammatory cell infiltration and cytokine synthesis12. ROS production and potassium efflux appear to play an important role in inflammasome activation in cardiac fibroblasts undergoing hypoxia/reoxygenation protocols.

Chemokine induction is a prominent feature of the post-infarction inflammatory response13. Chemokines provide directional signals for extravasation of leukocyte subpopulations in the infarcted myocardium. Both CC chemokines that function as potent mononuclear cell chemoattractants, and ELR motif-containing CXC chemokines that attract neutrophils, are rapidly and markedly upregulated in the infarcted myocardium. Chemokines released in the infarct are immobilized to glycosaminoglycans on the endothelial surface and in the extracellular matrix; these interactions generate localized high chemokine concentrations in areas of injury despite the shear forces caused by blood flow14. Through interactions with chemokine receptors expressed by leukocyte subpopulations, the chemokine expression profile in the infarcted myocardium determines the composition of the leukocytic infiltrate. Neutrophils are recruited very early after cardiac injury, pro-inflammatory monocytes and lymphocytes follow. Leukocyte transmigration in the infarcted myocardium requires adhesive interactions with activated vascular endothelial cells and involves a cascade of molecular steps. First, leukocytes are “captured” from the rapidly flowing bloodstream and roll on vascular endothelial cells through interactions involving a family of cell adhesion receptors, the selectins. The next step is stable arrest, characterized by firm adhesion of the leukocyte on the endothelial surface mediated through chemokine-induced activation of leukocyte integrins that bind to their endothelial counterreceptors (such as Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule (VCAM)-1, Intercellular Adhesion Molecule (ICAM)-1/ICAM-2 and the members of the Junctional Adhesion Molecules (JAM) family). Transendothelial migration follows at both junctional and non-junctional locations leading to infiltration of the infarcted tissue with leukocytes.

SUPPRESSION AND RESOLUTION OF THE POST-INFARCTION INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE: THE CELLULAR EFFECTORS

In experimental models of myocardial infarction, early activation of inflammatory signals is followed by rapid repression of pro-inflammatory genes and subsequent resolution of the leukocytic infiltrate (Figure 1)15. A growing body of evidence suggests that resolution of post-infarction inflammation is an active process that requires activation of multiple inhibitory pathways. Timely resolution of inflammation following myocardial infarction requires the coordinated actions of several different cell types and involves the participation of the extracellular matrix. Evidence suggests that neutrophils, mononuclear cells, endothelial cells and pericytes contribute to suppression and resolution of the inflammatory reaction; moreover, alterations in the composition of the extracellular matrix also participate in repression of inflammatory signals.

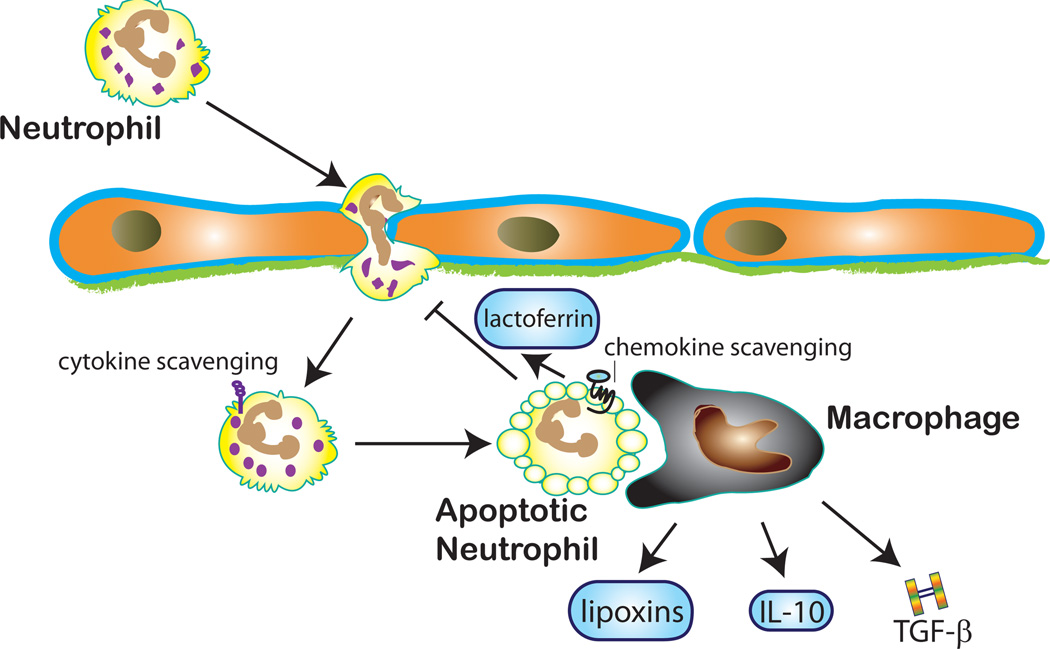

Apoptotic neutrophils as negative regulators of inflammation (Figure 2)

Figure 2. The role of neutrophil clearance in suppression of the inflammatory response.

Abundant neutrophils infiltrate the infarcted myocardium. Neutrophils are short-lived cells that undergo apoptosis; dying neutrophils may contribute to repression of the post-infarction inflammatory response through several distinct mechanisms. First apoptotic neutrophils may release lactoferrin, an inhibitor of granulocyte transmigration. Second, during clearance of apoptotic neutrophils, macrophages secrete large amounts of anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving mediators including IL-10, TGF-β and lipoxins. Third, expression of decoy cytokine receptors by neutrophils may promote cytokine scavenging. Increased expression of chemokine receptors (such as CCR5) in apoptotic neutrophils may serve as a molecular trap for chemokines terminating their action.

Perhaps the most important cellular mechanism for resolution of inflammation is clearance of apoptotic cells in the injured tissue 16, a process associated with active suppression of inflammation, as phagocytes ingesting apoptotic cells release large amounts of inhibitory mediators17. The abundant neutrophils infiltrating the infarcted myocardium represent a large pool of short-lived inflammatory cells, programmed to undergo apoptosis. Their removal from the infarcted myocardium by macrophages, prodigious phagocytic cells, is likely to activate potent inhibitory pathways. Neutrophil life-span may be somewhat prolonged in the pro-inflammatory environment of the infarct due to the effects of Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-α and IL-1β, mediators capable of extending granulocyte survival18. However 3–7 days after the acute event the neutrophil infiltrate resolves in both mouse and canine infarcts15 as most granulocytes undergo apoptosis. Like all dying cells, apoptotic neutrophils attract their scavengers by producing “find me’ signals (such as lipid mediators and nucleotides) and express “eat me” signals in their surface (such as lysophosphatidylcholine) promoting their own clearance. Apoptotic granulocytes are capable of attenuating inflammation through two distinct mechanisms. First, dying neutrophils release mediators that inhibit further neutrophil recruitment, such as annexin A1 and lactoferrin19. These mediators also act as chemoattractants for phagocytic cells thus promoting resolution of the neutrophil infiltrate. Second, uptake of apoptotic neutrophils activates an anti-inflammatory program in macrophages promoting induction and release of IL-10, Transforming Growth Factor (TGF)-β and of proresolving lipid mediators (such as lipoxins and resolvins)20. Although the fundamental biology of the inflammatory response suggests that macrophage-mediated clearance of apoptotic infiltrating neutrophils may be crucial in triggering anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving signals, the significance of these interactions in the infarcted heart has not been investigated.

Monocyte subpopulations as suppressors of the inflammatory response

Through their ability to produce and secrete inhibitory mediators, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, suppressive monocyte subpopulations are ideally suited as negative regulators of inflammation. Over the last decade our understanding of the involvement of monocytes in immune responses has evolved revealing their functional heterogeneity and their complex roles in inflammatory conditions21. In mice two main subsets of monocytes have been documented: a) a subpopulation of Ly6Chi inflammatory monocytes that migrate into injured tissues and exhibit high levels of expression of the CC chemokine receptor CCR2, while expressing low levels of the fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 (Ly-6ChiCCR2hiCX3CR1low) and b) a smaller subset of Ly6Clow/CCR2low/neg/CX3CR1hi “resident” monocytes 22. Monocyte subpopulations with distinct modulatory effects on inflammatory responses have also been described in humans: human CD16- monocytes express high levels of CCR2 and have pro-inflammatory properties resembling murine Ly6Chi cells21. Following myocardial infarction early induction of the CCR2 ligand Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein (MCP)-123 drives recruitment of pro-inflammatory Ly-6Chi monocytes; these cells scavenge debris and secrete inflammatory cytokines and matrix-degrading proteases24. Repression of inflammatory signals is associated with recruitment of Ly6Clo/CX3CR1hi monocytes that produce angiogenic mediators and contribute to infarct healing. Whether specific chemokine/chemokine receptor interactions induce recruitment of suppressive monocyte subpopulations ensuring timely repression of post-infarction inflammation in the healing myocardium remains unknown. Monocyte heterogeneity has also been demonstrated in human patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulating pro-inflammatory CD14+/CD16- cells showed an early peak in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction and were negatively associated with recovery of function25.

Macrophage heterogeneity and resolution of post-infarction inflammation

In the pro-inflammatory environment of the healing infarct, upregulation of Macrophage-Colony Stimulating Factor (M-CSF) induces monocyte to macrophage differentiation26. During resolution of post-infarction inflammation macrophages are capable of exerting both inhibitory actions by secreting mediators that suppress inflammation, and proresolving effects through the removal of inflammatory leukocytes. Despite extensive evidence demonstrating the abundance of macrophages in the infarcted heart and their potential to regulate the inflammatory response, our knowledge on the role of macrophage-mediated interactions in repression of inflammatory signals and in resolution of the leukocyte infiltrate remains extremely limited. The key for understanding the role of macrophages in cardiac repair lies in identification of time-dependent alterations in phenotype and function of macrophage subpopulations. Mirroring the classification of T helper cells in Th1 and Th2 types, two distinct macrophage subsets have been recognized27: the classically activated M1 macrophages that exhibit enhanced microbicidal capacity and secrete large amounts of pro-inflammatory mediators and the alternatively-activated M2 macrophages that show increased phagocytic activity and a phenotype of high expression of IL-10, the decoy type II IL-1 receptor and IL-1 Receptor Antagonist (IL-1RA) 28. The polarized M1/M2 classification clearly represents an oversimplification; it is increasingly recognized that inflamed tissues contain a wide spectrum of macrophage subpopulations with distinct properties and functional characteristics29. Mosser and Edwards have suggested a functional classification of macrophages that distinguishes in addition to the pro-inflammatory, classically-activated cells, subpopulations of regulatory and reparative macrophages29. In the complex environment of the infarcted heart, the spatially and temporally regulated expression of a variety of cytokines, chemokines and growth factors is likely to affect macrophage phenotype leading to sequential generation of many distinct subsets. During the resolution phase of inflammation, macrophages that phagocytose apoptotic neutrophils may acquire a regulatory phenotype, expressing large amounts of inhibitory mediators and promoting suppression of the inflammatory response. Unfortunately, experimental studies investigating the role of macrophage subpopulations in the healing infarct have not been performed. The phenotypic characteristics, molecular profile and the functional role of these cells remain unknown.

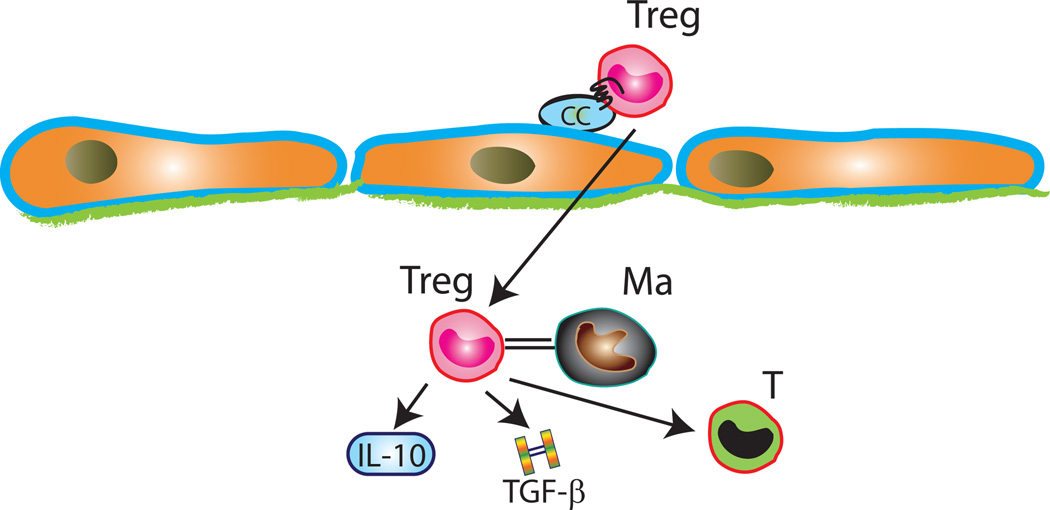

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) as suppressors of post-infarction inflammation (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) may suppress inflammation following myocardial infarction.

Molecular interactions involving yet unidentified chemokines presented by endothelial cells and their corresponding chemokine receptors mediate infiltration of the infarcted myocardium with Tregs. Tregs may suppress inflammation by secreting inhibitory signals such as IL-10 and TGF-β and through contact-mediated actions. T, effector T cell; Ma, macrophage.

Due to the tight regulation of constitutive lymphocyte homing, homeostatic circulation of naïve lymphocytes is restricted to secondary lymphoid organs30. In contrast, in inflammatory states, chemokine induction and activation of adhesive lymphocyte/endothelial cell interactions result in intense infiltration of inflamed non-lymphoid tissues with lymphocytes. Effector T cells are recruited in sites of injury where they release pro-inflammatory mediators. However, the immune system also produces a population of T cells with suppressive properties that serves to keep in check the activation and expansion of the immune response. These cells, termed regulatory T cells (Tregs) are a CD4+/CD25+ subset of T lymphocytes with potent suppressive properties31. Tregs play an essential role in immune homeostasis; depletion of Tregs elicits autoimmunity and augments immune responses to non-self antigens32. Beyond their essential role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases, Tregs also appear to modulate immune responses to infection and malignancy and have been implicated in suppression of the atherosclerotic process33. Recent evidence suggests that Tregs may play a role in suppression of the post-infarction inflammatory response34. Mice with genetic disruption of the chemokine receptor CCR5 exhibited accentuated inflammatory response and enhanced Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP) activity following reperfused myocardial infarction. Increased inflammation in CCR5 null animals was associated with reduced infiltration of the infarcted myocardium with CD4+/CD25+ Tregs34. Although a causative relation between defective recruitment of Tregs and enhanced remodeling has not been established, Tregs may modulate macrophage phenotype and suppress post-infarction inflammation by secreting soluble mediators, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, or through contact-dependent pathways34. On the other hand, the anti-inflammatory effects of CCR5 signaling may be mediated through Treg-independent mechanisms. CCR5 signaling may suppress inflammation through chemoattraction of inhibitory monocyte subsets; moreover, increased CCR5 expression in apoptotic leukocytes may serve as a molecular sink for inflammatory chemokines35.

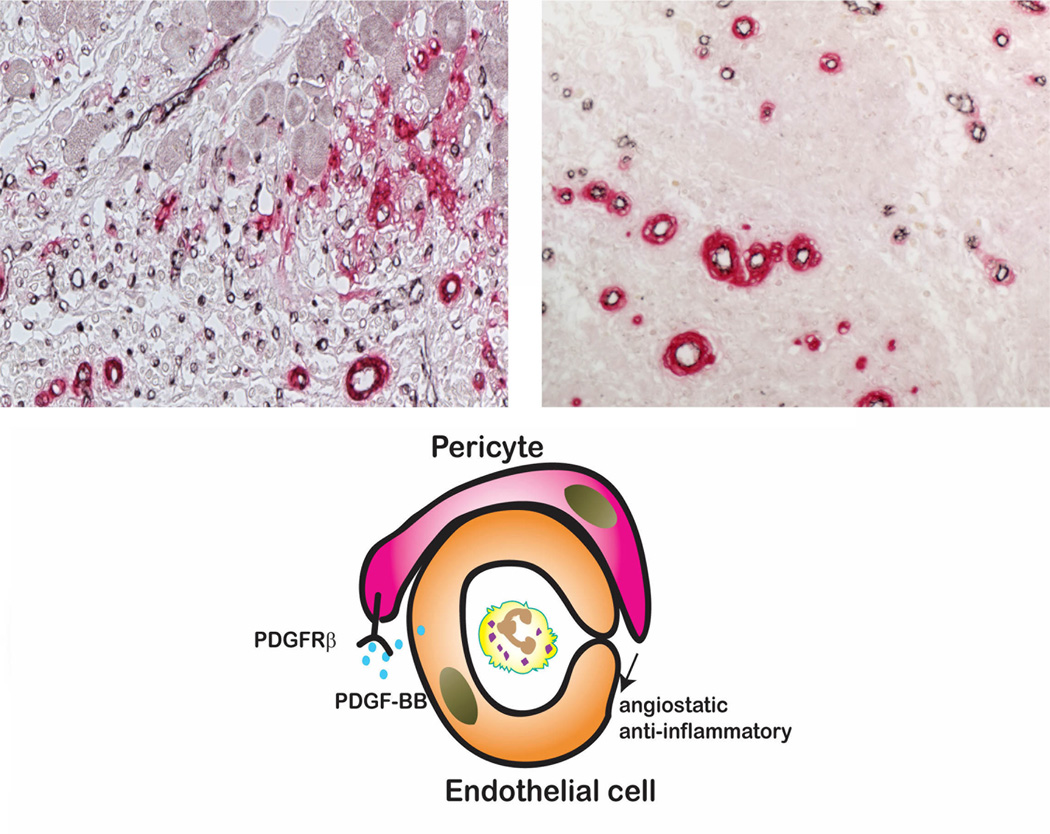

Pericyte coating may control inflammation by promoting vascular maturation (Figure 4)

Figure 4. Vascular maturation through acquisition of a mural cell coat may contribute to inhibition of inflammation following myocardial infarction.

Upper panel: Dual immunohistochemical staining for the endothelial cell marker CD31 (black) and α-smooth muscle actin (red) to detect vascular mural cells illustrates the maturation process in canine infarct neovessels. After 7 days of reperfusion the infarct contains abundant microvessels; the majority lacks coverage with mural cells. In the mature scar after 28 days of reperfusion, a large number of coated vessels is noted, whereas most capillaries have regressed. Acquisition of a pericyte coat involves PDGF-BB/PDGFR-β interactions and contributes to stabilization of the scar reducing the inflammatory and angiogenic activity of endothelial cells.

During the inflammatory phase of infarct healing, vascular endothelial cells synthesize and present chemokines while expressing adhesion molecules on their surface. Adhesive interactions between endothelial cells and leukocytes are required for recruitment of inflammatory cells into the infarct. As the inflammatory infiltrate is replaced by granulation tissue, extensive angiogenesis occurs resulting in formation of neovessels that provide oxygen and nutrients to the highly dynamic and metabolically active cells of the healing wound. Because Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) is markedly induced within the first few hours after infarction, early neovessels in the infarcted heart are hyperpermeable and pro-inflammatory36 lacking a pericyte coat. As a mature scar is formed, the infarct vasculature undergoes a maturation process that plays an important role in stabilization of the wound37. Some of the infarct neovessels acquire a coat comprised of pericytes and smooth muscle cells, whereas uncoated endothelial cells undergo apoptosis. Acquisition of a mural cell coat reduces vascular permeability and decreases angiogenic potential of the vessels, contributing to the formation of a stable scar. The interactions between pericytes and endothelial cells that result in vascular coating involve Platelet Derived Growth Factor (PDGF)-BB-PDGFR-β signaling38. PDGFR-β blockade resulted in impaired maturation of the infarct vasculature, enhanced capillary density, and promoted formation of a significant number of dilated uncoated vessels. Defective vascular maturation upon PDGFR-β inhibition was associated with increased and prolonged extravasation of red blood cells and monocyte/macrophages, suggesting increased permeability and uncontrolled inflammation; these defects were associated with decreased collagen content in the healing infarct. Thus, pericyte coating is an important step for suppression of granulation tissue formation following myocardial infarction, and promotes resolution of inflammation and stabilization of the scar. Whether pericytes secrete soluble mediators, or directly signal to promote endothelial cell quiescence, is unknown.

The extracellular matrix as a regulator of the post-infarction inflammatory response

Beyond their obvious contribution in providing mechanical support to the infarcted heart, extracellular matrix proteins also act as key regulators of the inflammatory response. The dynamic alterations in the extracellular matrix composition critically regulate inflammatory activity by modulating phenotype function and gene expression in fibroblasts, endothelial cells and leukocytes. In the early stages following infarction, generation of matrix fragments enhances cytokine and chemokine synthesis, while deposition of a plasma-derived provisional matrix provides a scaffold for leukocyte infiltration and may transduce pro-inflammatory signals39. Clearance of matrix fragments from the injured tissue appears to be an essential step for resolution of inflammation and, much like removal of apoptotic cells, may activate inhibitory pathways40. Hyaluronan fragments are potent activators of inflammatory pathways; their clearance through interactions with the transmembrane adhesion molecule CD44 is important for resolution of chronic inflammation41. Extensive disruption of the myocardial hyaluronan network is observed in myocardial infarcts. CD44 expression is markedly induced in leukocytes, wound myofibroblasts and vascular cells infiltrating the infarct; CD44 absence is associated with enhanced and prolonged neutrophil and macrophage infiltration and increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the infarcted myocardium42. These observations suggest that CD44-mediated removal of hyaluronan fragments may be essential to restrain the inflammatory response.

The temporally and spatially restricted expression of fibronectin and matricellular proteins in the infarcted heart may provide an additional matrix-related mechanism for regulation of inflammation. The matricellular protein Thrombospondin (TSP)-1, a crucial TGF-β activator with potent angiostatic and anti-inflammatory properties, is strikingly upregulated in the border zone of the infarct43. TSP-1 −/− mice exhibited enhanced and prolonged expression of chemokines in the infarcted heart and showed expansion of the inflammatory infiltrate into the non-infarcted area. Prolonged and expanded post-infarction inflammation in TSP-1 null animals resulted in increased adverse remodeling of the ventricle43. These findings suggest an important role for TSP-1 in suppression and containment of the inflammatory reaction following infarction. Localized induction of TSP-1 in the infarct border zone may form a “barrier” preventing expansion of the inflammatory infiltrate in the non-infarcted area. The mechanisms involved in TSP-1-mediated inhibition of inflammation remain unknown and may involve impaired TGF-β activation or direct anti-inflammatory actions.

MOLECULAR PATHWAYS INVOLVED IN REPRESSION AND RESOLUTION OF POST-INFARCTION INFLAMMATION

Negative regulation of TLR signaling

Considering the extensive collateral damage that may be induced by stimulation of a broad spectrum of inflammatory signals due to uncontrolled TLR activation, it is not surprising that several distinct pathways have evolved to negatively regulate TLR-mediated responses. Over the last ten years, many molecules have been identified as inhibitors of TLR signaling at multiple levels; detailed discussions of these pathways are provided in fundamental immunological reviews44. Disruption of some of these negative regulators results in uncontrolled inflammation suggesting their essential role in restraining TLR-mediated immune responses. Tyrosine phosphatases can negatively regulate TLR responses. SH2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 1 (SHP1) negatively regulates TLR-mediated induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines through activation of NF-κB and MAPK45. SHP2 also has inhibitory actions, but in a more specific manner limiting TLR3-induced inflammatory responses without affecting TLR2 or TLR9 signaling46. Interleukin-1 Receptor Associated Kinase (IRAK)-M, is the only member of the IRAK family that lacks kinase activity, thus functioning as a decoy that negatively regulates TLR- and IL-1-mediated inflammatory responses. IRAK-M null mice exhibit accentuated inflammatory responses following bacterial and viral infections and IRAK-M deficient macrophages display enhanced activation of IL-1/TLR signaling47. IRAK-M acts by preventing IRAK-1 from dissociating from the MyD88 complex thus inhibiting NF-κB activation. Additional inhibitory actions of IRAK-M are IRAK-1-independent, mediated through stabilization of MAPK Phosphatase (MKP)-1 that negatively regulates TLR2-induced p38 phosphorylation48. MyD88s, a lipopolysaccharide-inducible spliced form of MyD88 that lacks the IRAK4-interacting domain is also involved in negative regulation of TLR signaling by inhibiting IRAK-4-mediated IRAK-1 phosphorylation49. The TAM receptor protein tyrosine kinases have been recently recognized as inhibitors of TLR signaling. TAM ligands activate a type I interferon receptor pathway leading to STAT1 activation and induction of SOCS1 and SOCS3, which block TLR signaling. Defective TAM signaling results in interruption of this inhibitory pathway and potentiates TLR signaling50. Receptor Interacting Protein 3 (RIP3), a kinase that inhibits RIP1-induced NF-κB signaling51, activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3), the autophagy-related molecule Atg16L1, and the TLR-inducible zinc finger proteins A20 and Zc3h12a have also been identified as essential negative regulators of TLR signaling in vivo52. Despite the fundamental evidence demonstrating a role for all these pathways in preventing uncontrolled TLR signaling; their contribution in regulation of post-infarction inflammation has not been investigated.

Negative regulation of cytokine signaling

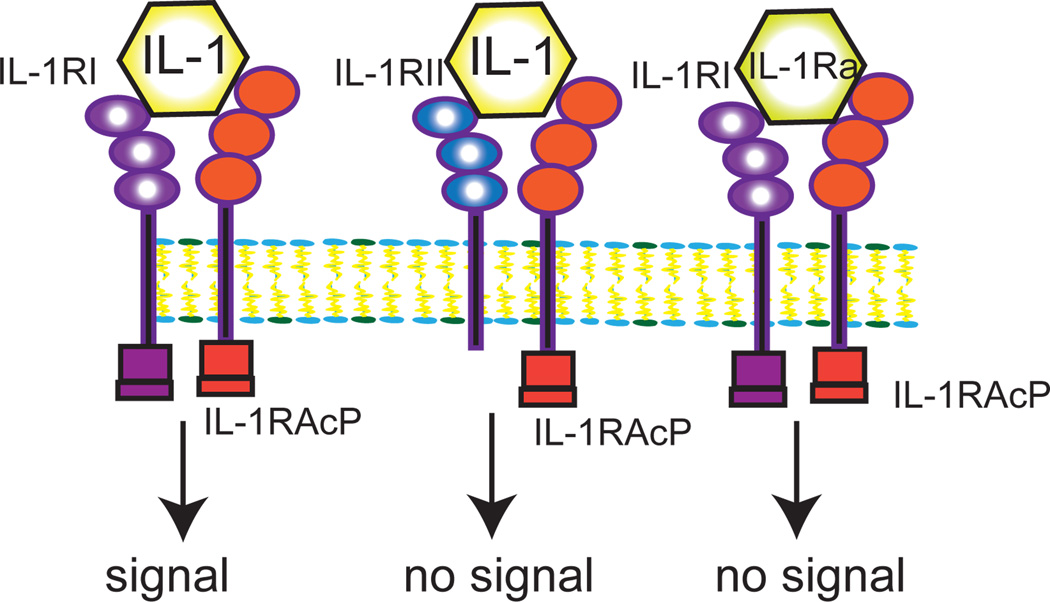

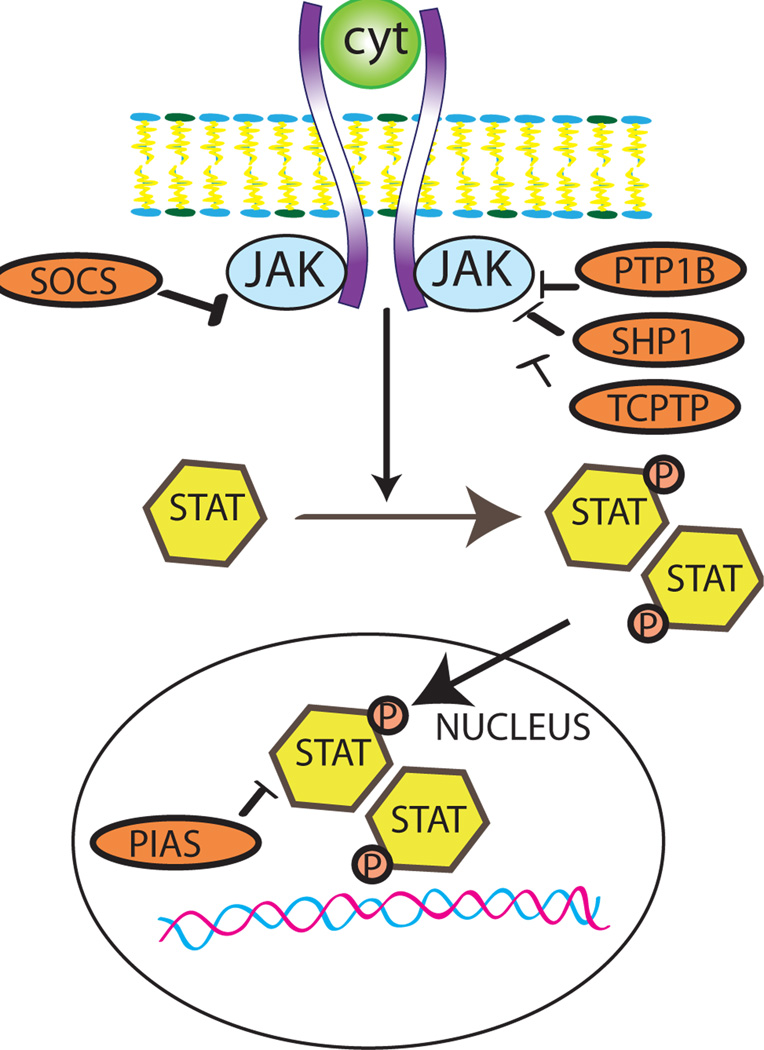

Binding of cytokines to their receptors results in activation of intracellular cascades involving a family of tyrosine kinases called Janus activated kinases (JAKs). Activated JAKs phosphorylate tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic portion of cytokine receptors and serve as docking platforms for intracellular proteins. Most of the cytokine-activated intracellular proteins belong to the family of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) and after tyrosine phosphorylation by JAKs, then dimerize and translocate to the nucleus where they initiate transcription. Negative regulation of cytokine signaling may involve several distinct mechanisms. First, natural endogenous cytokine inhibitors may be upregulated to suppress specific responses. IL-1Ra, an endogenous competitive inhibitor of IL-1-driven inflammation, plays an important role in preventing autoinflammatory responses. Although the role of endogenous IL-1Ra in suppression and resolution of the post-infarction inflammatory response has not been dissected, IL-1Ra overexpression exerts protective actions on the infarcted heart53. Second, expression and activation of decoy receptors (such as the type II IL-1 receptor) may serve as molecular sinks or scavengers for cytokines (Figure 5). The importance of this regulatory mechanism in regulating cytokine-driven inflammation following infarction has not been tested. Third, endocytosis of signaling-competent receptors followed by proteasomal degradation of signaling molecules may play an important role in preventing uncontrolled cytokine actions. Finally, negative regulation of cytokine signaling may involve induction of molecular signals that actively terminate cytokine signaling by dephosphorylating JAKs (Figure 6)54. Several phosphatases have been implicated in negative regulation of cytokine signaling, including SHP-1, the protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B and the T cell protein tyrosine phospatase (TCPTP). Members of the protein inhibitor of activated STAT (PIAS) family inhibit cytokine-induced gene expression by blocking the DNA binding ability of STAT proteins55. Perhaps the best studied family of cytokine inhibitors is the Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling (SOCS) family of inhibitory proteins. Cytokine Inducible SH2 containing protein (CIS), the first member of the SOCS family, acts as a negative regulator of STAT5 signaling. The development of CIS knockout animals suggested that most CIS-mediated functions may be redundant in vivo due to compensation by other SOCS proteins. SOCS-1 is the best studied member of the SOCS family. Like most SOCS proteins, SOCS-1 is inducible upon stimulation of the cells with cytokines or bacterial components. A wide range of cytokines can stimulate SOCS-1 synthesis, including mediators that activate JAK/STAT and growth factors that act independently of STAT signaling (such as TGF-β). SOCS-1 exhibits broad inhibitory effects on cytokine signaling, mediated through binding with the activation loop of JAKs and suppression of their kinase activity54. JAK-independent suppressive actions of SOCS-1 have also been reported. The generation of SOCS-1 null mice revealed an essential role for SOCS-1 in suppression of inflammation. SOCS-1 −/− mice are born normally but develop diffuse multi-organ inflammation due to uncontrolled cytokine activity and die approximately three weeks after birth56. T cells and dendritic cells isolated from SOCS-1 null mice exhibit increased activity highlighting the role of SOCS-1 in regulating immune responses. In contrast to SOCS-1, SOCS-2 is only upregulated by certain hormones (such as prolactin and growth hormone) and does not exert suppressive actions on inflammatory cytokine signaling. SOCS-3, on the other hand, is structurally and functionally related to SOCS-1 serving as a negative feedback regulator of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Both pro-inflammatory cytokines and the inhibitory cytokine IL-10 induce SOCS-3 expression in mononuclear cells. In vivo studies suggest that SOCS-3 plays a negative regulatory role in a variety of inflammatory and autoimmune processes57. In a model of cerebral ischemia, SOCS-3 knockdown exacerbated injury resulting in impaired suppression of the post-ischemic inflammatory response58. Although members of the SOCS family are likely to play an important role in regulation of the post-ischemic myocardial inflammatory response, their contribution to the downmodulation of inflammation in the infarcted heart has not been investigated.

Figure 5. Negative regulation of IL-1-mediated inflammation.

Termination of IL-1-driven inflammation may involve a competitive inhibitor (IL-1Ra) and a decoy receptor (IL-1RII). IL-1RAcP, IL-1 receptor accessory protein..

Figure 6. Negative regulation of cytokine signaling.

Intracellular signals such as the SOCS proteins and several phosphatases interfere with JAK-STAT signaling inhibiting cytokine responses (see text).

Pentraxin-3 as a negative regulator of inflammation

The members of the pentraxin family constitute the prototypic components of the humoral arm of the innate immune system, representing the functional ancestors of antibodies and playing an important role in discrimination between self and non-self and in recognition of danger signals59. C-Reactive Protein (CRP) and Serum Amyloid Peptide (SAP) are the classic short pentraxins, prototypic acute phase proteins released by hepatocytes upon inflammatory injury. CRP injection in an experimental model of coronary occlusion accentuates cardiomyocyte injury by activating the complement cascade; CRP inhibition has been suggested as a promising therapeutic strategy in myocardial infarction60. The prototypic long pentraxin, PTX3, on the other hand, is upregulated in the infarcted heart and appears to play an important role in negative regulation of the inflammatory reaction. PTX3 null mice exhibit accentuated cardiac injury in a model of reperfused infarction, attributed at least in part to accentuated inflammation resulting in a larger no-reflow area61. Although immobilized PTX3 activates the complement cascade, in the fluid phase, PTX3 can sequester C1q preventing complement activation62. Moreover, in inflamed tissues PTX3 released by neutrophils binds to P-selectin and inhibits leukocyte recruitment63, while suppressing the pro-inflammatory actions of platelets64. Downmodulation of the complement cascade, disruption of selectin-mediated rolling and inhibition of platelet-induced inflammation may contribute to the inhibitory effects of PTX3 in the post-infarction inflammatory response.

Termination of chemokine signaling

Chemokine signaling is essential for infiltration of the infarcted heart with pro-inflammatory leukocytes13. The brief duration of MCP-1-dependent recruitment of CCR2+ mononuclear cells suggests rapid termination of chemokine signaling24. Suppression of chemokine synthesis by inhibitory mediators, such as TGF-β65, IL-10 or lipid-derived substances may be the predominant mechanism for deactivation of chemokinetic signals. Moreover, two additional pathways may operate for negative regulation of chemokine responses. First, post-translational modifications of mature chemokine proteins through protease-mediated actions may generate molecules with reduced activity, or endogenous chemokine antagonists66. Although effects of several members of the MMP family, cathepsins and dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP) IV in chemokine processing have been documented in vitro, in vivo evidence supporting the role of these actions in myocardial infarction is lacking. Second, silent chemokine receptors that bind to their ligand without signaling may function as decoy or scavenging receptors67. Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines (DARC) and D6 have been identified as essential mechanisms for termination of chemokine-driven inflammation in vivo. DARC is expressed on blood vessels and erythrocytes and limits endotoxin-induced inflammation68. D6 is expressed on the lymphatic endothelium and functions as a mechanism for chemokine clearance in cutaneous inflammation69. Whether chemokine decoy receptors are expressed and play a role in myocardial inflammation remains unknown. It should be noted that under certain conditions signaling-competent chemokine receptors may function as decoy receptors. In a model of peritonitis CCR5 expression was markedly increased in apoptotic neutrophils and lymphocytes serving as a molecular trap for chemokines35. This mechanism may provide an alternative explanation for the accentuated inflammatory response observed in CCR5 null animals following myocardial infarction34.

Lipid mediators in resolution of post-infarction inflammation

During acute inflammation, leukocytes synthesize a wide range of lipid-derived mediators that regulate the inflammatory response. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes are released early following tissue injury and exert pro-inflammatory actions70. During the resolution phase of inflammation, a recently-described genus of specialized proresolving mediators (SPM) is induced71, comprised of four distinct families: the lipoxins, resolvins, protectins and the maresins. These mediators have potent and direct anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving functions, limiting inflammatory leukocyte recruitment, while promoting clearance of apoptotic neutrophils by macrophages. Lipoxins A4 and B4 are lipoxygenase-derived eicosanoids; their appearance in inflammatory exudates is associated with resolution of inflammation. Lipoxins are anti-inflammatory at nanomolar concentrations inhibiting chemokine-driven recruitment of both granulocytes and monocytes72. At the site of inflammation lipoxins also stimulate macrophages to ingest and clear apoptotic neutrophils73 exerting proresolving actions. Resolvins are enzymatically derived from the major ω-3 fatty acids EPA (E-series resolvins) and DHA (D-series resolvins), or as aspirin-triggered epimers generated through Cycloxygenase (COX)-2-dependent reactions in the presence of aspirin. Resolvins exert potent anti-inflammatory effects by attenuating neutrophil transendothelial migration and tissue infiltration74, while inducing resolution of inflammation by enhancing neutrophil clearance from sites of injury. Protectin D1 (PD1) is generated from the biosynthetic intermediate 17S-hydroxy-DHA and is also released in inflammatory exudates. PD1 possesses potent immunoregulatory functions in vitro and in vivo markedly inhibiting inflammation75. Maresins, a newly discovered family of anti-inflammatory mediators, were isolated from exudates of mouse peritonitis and were identified as inhibitors of inflammation and potent pro-resolving agents76. Their mechanism of function remains largely unknown. Renal and pulmonary ischemia and reperfusion induce upregulation of D series resolvins, PD1 and lipoxins77,78. Administration of exogenous anti-inflammatory eicosanoids has demonstrated potent anti-inflammatory effects in experimental models of ischemia and reperfusion. Moreover, a recent experimental study reported protective effects of exogenous administration of resolving E1 in the ischemic and reperfused myocardium79. However, evidence on the involvement of lipid-derived mediators in resolution of the post-infarction myocardial inflammatory response is lacking.

Inhibition of leukocyte adhesion cascades

Inflammatory responses are dependent on activation of adhesive interactions between endothelial cells and leukocytes. During suppression of inflammation the adhesive properties of both endothelial cells and leukocytes are markedly attenuated. Upregulation of pleiotropic inhibitory cytokines that suppress adhesion molecule expression, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, may play an important role in downmodulation of adhesive interactions. In addition, recent evidence has identified endogenous endothelial cell-derived integrin ligands that serve as potent inhibitors of leukocyte adhesion80. Developmental endothelial locus (Del)-1 is secreted by endothelial cells and binds to the LFA-1 integrin functioning as an antagonist of leukocyte/endothelial cell adhesion. In vivo, loss of Del-1 is associated with accentuated endotoxin-mediated pulmonary inflammation81. Whether Del-1, or other endogenous inhibitors of adhesion, is involved in regulation of the post-infarction inflammatory response remains unknown.

The inhibitory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β

Extensive evidence has documented the role of the pleiotropic cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β in regulation of the immune response82. TGF-β1 is essential in restraining relentless T cell responses in peripheral tissues82. IL-10, on the other hand, is critically involved in immune tolerance limiting immune responses to foreign antigens. Although both mediators have been implicated in regulation of the post-infarction inflammatory response, their role is complex as they affect most cell types involved in cardiac repair in a context-dependent manner.

IL-10

IL-10, a cytokine predominantly expressed by activated T lymphocytes and stimulated monocytes, possesses potent anti-inflammatory properties and prevents excessive inflammatory reactions83. Among the different cell types affected by IL-10, mononuclear cells appear to be particularly modified in regard to their function, morphology and phenotype. IL-10 inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by endotoxin-stimulated macrophages suppressing the inflammatory response. Furthermore, IL-10 may play a significant role in extracellular matrix remodeling by promoting Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases (TIMP)-1 synthesis, contributing to stabilization of the matrix84. The suppressive effects of IL-10 on mononuclear cells are dependent on STAT3 signaling.

Published evidence implicates IL-10 in regulation of the post-infarction inflammatory reaction. IL-10 mRNA and protein is markedly upregulated in reperfused canine and murine myocardial infarction exhibiting a prolonged time course of expression85,15. T cell subsets and macrophage subpopulations appear to be responsible for IL-10 synthesis in the infarcted myocardium85,86. In a canine model IL-10 upregulation in the infarcted myocardium was associated with decreased expression of proinflammatory cytokines; i_n vitro_, IL-10 released in the cardiac interstitium was responsible for induction of TIMP-1 mRNA by isolated canine mononuclear cells suggesting a role in matrix stabilization85. Two independent loss-of-function studies in mouse models of reperfused infarction have produced somewhat contradictory results. Yang and co-workers suggested that IL-10 −/− mice had markedly increased mortality and exhibited an enhanced inflammatory response following reperfused myocardial infarction showing accentuated neutrophil recruitment, elevated plasma levels of TNF-α and higher tissue expression of ICAM-187. In contrast, Zymek and co-workers found much more subtle differences in the post-infarction inflammatory response between IL-10 null and wildtype animals88. Infarcted IL-10 −/− mice and wildtype littermates exhibited comparable survival following infarction. Although IL-10 disruption was associated with higher peak TNF-α and MCP-1 mRNA levels in the infarcted heart, repression of pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine synthesis and resolution of the neutrophil infiltrate were not affected. IL-10 gene disruption did not alter fibrous tissue deposition and dilative remodeling of the infarcted heart88. Taken together the findings suggest that IL-10 induction in the infarcted heart may play a role in controlling the acute inflammatory response, but is not involved in clearance of the inflammatory infiltrate and resolution of inflammation. However, administration of exogenous IL-10 significantly reduced inflammation and improved cardiac remodeling following myocardial infarction in mice89.

Members of the TGF-β superfamily

The TGF-βs are some of the most pleiotropic and multifunctional peptides known and exert potent and direct effects on all cell types involved in the inflammatory and reparative response following myocardial infarction. The cellular actions of TGF-β are not only dependent on the cell type but also on its state of differentiation and on the cytokine milieu90. Development of mice with genetic disruption of the TGF-β1 gene has revealed a critical role of TGF-β in homeostasis of the immune system. Approximately 50% of TGF-β1 null mice die in utero due to defective yolk sac vasculogenesis and hematopoiesis91. The remaining animals develop to term and show no gross developmental abnormalities, but about 2–4 weeks after birth they succumb to a wasting syndrome associated with multifocal inflammation and massive lymphocyte and macrophage infiltration in many organs, but primarily in the heart and lungs92. The inflammatory response in TGF-β1 null mice is eliminated by depleting mature T cells93.

In vitro and in vivo studies suggest that TGF-β regulates immune and inflammatory responses by modulating leukocyte phenotype and activity. The effects of TGF-β on lymphocytes, monocytes and macrophages can be either stimulatory or inhibitory, depending on microenvironmental cues, the state of cellular differentiation and the tissue origin of the cells94, highlighting the pleiotropic nature of the cytokine. TGF-β inhibits T and B lymphocyte proliferation95, suppresses Th cell differentiation, and induces conversion of naïve T cells into Tregs96. Femtomolar concentrations of TGF-β induce chemotaxis in peripheral blood monocytes97 suggesting that it may play an important role in recruitment of mononuclear cells in inflamed tissues. Picomolar concentrations of TGF-β activate monocytes, stimulating synthesis of a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors90,97 and increasing integrin expression. In contrast to the activating effects of TGF-β on peripheral blood monocytes, its actions on mature macrophages are predominantly suppressive. TGF-β has a deactivating effect on macrophages, suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine synthesis98,99 and decreasing reactive oxygen generation. In vascular endothelial cells TGF-β inhibits cytokine-stimulated synthesis of adhesion molecules100 attenuating lymphocyte101 and neutrophil102 adhesion to the endothelium. These TGF-β mediated effects may be important in suppression and resolution of the inflammatory response.

In addition to its effects on leukocytes, TGF-β is a potent modulator of fibroblast phenotype and function. TGF-β stimulation induces myofibroblast transdifferentiation103 and enhances synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins. Moreover, TGF-β suppresses the activity of proteases that degrade extracellular matrix by inhibiting MMP expression and by inducing synthesis of protease inhibitors, such as PAI-1 and TIMPs104,105. Thus, through its broad immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties and its profibrotic/matrix-preserving actions, TGF-β is an excellent candidate for a role as the “master switch” mediating suppression of post-infarction inflammation while promoting fibroblast activation and scar formation106. Although this is an attractive hypothesis, the complex biology of TGF-β activation and its pleiotropic effects have hampered efforts to test the concept in experimental models of myocardial infarction.

TGF-β is markedly upregulated in experimental models of myocardial infarction107 where it is predominantly localized in the infarct border zone, associated with expression of its downstream intracellular effectors, Smad2, 3 and 4108 and phosphorylation of Smad1 and Smad2109. Although evidence suggests that bioactive TGF-β is released in the cardiac extracellular fluids 3–5h following reperfused infarction110, the mechanisms responsible for TGF-β activation in the infarcted heart are poorly understood. Induction of the matricellular protein TSP-1 in the infarct border zone may play an important role in activation of TGF-β signaling pathways in mouse and canine infarcts43.

In vivo, several studies have suggested important modulatory effects of TGF-β on the post-infarction inflammatory response. TGF-β injection during the inflammatory phase of healing significantly reduced ischemic myocardial injury, presumably by attenuating the deleterious effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines111. Two independent studies showed that systemic inhibition of TGF-β signaling by injection of an adenovirus harboring soluble TGF-β type II receptor in the hindlimb muscles resulted in attenuated left ventricular remodeling by modulating cardiac fibrosis112,113. However, early TGF-β inhibition increased mortality and exacerbated left ventricular dilation enhancing cytokine expression, suggesting that during the phase of resolution of the inflammatory response, TGF-β signaling may play an important role in suppression of inflammatory mediator synthesis112.

Because of the pleiotropic effects of TGF-β on the inflammatory and reparative response following infarction, dissection of the signaling pathways responsible for its actions in the infarcted myocardium is essential for identification of therapeutic targets. TGF-β is capable of activating the canonical Smad-mediated pathway as well as a variety of Smad-independent pathways. Many studies have suggested that Smad3 signaling plays an essential role in fibrotic conditions114; moreover, a growing body of evidence implicates Smad3 as a key mediator in TGF-β-induced suppression of inflammation115. Recent investigations have attempted to dissect the role of Smad3 signaling in the post-infarction inflammatory and reparative response. Somewhat surprisingly, Smad3 null animals had markedly suppressed peak chemokine expression and decreased neutrophil recruitment in the infarcted myocardium and showed timely repression of inflammatory gene synthesis and resolution of the inflammatory infiltrate. Although myofibroblast density was higher in Smad3 null infarcts, interstitial matrix deposition in the peri-infarct zone and the non-infarcted myocardium was markedly reduced. In vitro, Smad3 signaling was essential for TGF-β-mediated myofibroblast differentiation and matrix synthesis, but also exerted anti-proliferative effects116 on cardiac fibroblasts. In the absence of Smad3 the infarct was filled with a large number of dysfunctional fibroblasts. Thus, TGF-β/Smad3 signaling does not appear to be involved in suppression and resolution of inflammation in healing infarcts, but mediates interstitial fibrosis in the infarct border zone and in the non-infarcted myocardium. The role of non-canonical Smad-independent signaling in mediating TGF-β-induced suppression of post-infarction inflammation has not been investigated.

Recently, Growth Differentiation Factor (GDF)-15, another member of the TGF-β superfamily, has been identified as a crucial endogenous mediator involved in suppression of the inflammatory response associated with myocardial infarction. (GDF)-15 is upregulated in the infarcted myocardium, primarily localized in cardiomyocytes of the infarct border zone117. GDF-15 −/− mice had a high incidence of cardiac rupture following myocardial infarction associated with accentuated recruitment of neutrophils. GDF-15 restrains inflammation by counteracting conformational activation of neutrophil β2 integrins, thus preventing excessive chemokine-activated leukocyte arrest on the endothelium118.

The clinical implications: is adverse remodeling in patients with myocardial infarction due to defective suppression and impaired resolution of inflammation?

Ample evidence from experimental models of myocardial infarction suggests that defects in pathways involved in timely suppression, resolution and containment of the post-infarction inflammatory response result in adverse remodeling of the infarcted heart118,34,42. In addition to the experimental findings, the fundamental biology of inflammation suggests catastrophic consequences of an uncontrolled post-infarction inflammatory response on myocardial structure and function providing a strong theoretical basis to support the notion that prolonged or expanded inflammation would result in adverse outcome. Thus, there is little doubt that unrestrained inflammation is deleterious for the infarcted heart. However, to support the therapeutic importance of this concept, a key question needs to be answered: to what extent is defective negative regulation of the inflammatory response responsible for adverse remodeling and worse outcome in patients with acute myocardial infarction? Obviously, considering the difficulties in assessment of myocardial inflammation in human patients with acute myocardial infarction, this question is particularly challenging. However, emerging evidence from clinical trials may support a role for uncontrolled inflammation as a determinant of adverse outcome following myocardial infarction. In the A to Z study, persistently elevated serum MCP-1 levels in patients with acute coronary syndromes were independently associated with reduced survival119; the increased mortality in patients with sustained systemic inflammation was not due to new coronary events. The study did not examine the relation between MCP-1 levels and cardiac remodeling. However, one could hypothesize that persistently elevated serum chemokine levels may identify patient subpopulations with defective repression of pro-inflammatory signaling following myocardial infarction that results in accentuated remodeling and adverse outcome120.

Targeting the inflammatory response in patients with acute myocardial infarction

The idea of targeting the inflammatory response in patients with myocardial infarction is not new. Twenty to thirty years ago extensive experimental evidence derived primarily from research in large animal models suggested that early infiltration of the infarcted myocardium with leukocytes induces cytotoxic injury on viable cardiomyocytes extending ischemic damage121. These findings fueled several clinical trials aimed at protecting the ischemic myocardium through early inhibition of key inflammatory signals. The catastrophic effects of methylprednisolone administration in patients with acute myocardial infarction122 highlighted the need for more selective anti-inflammatory approaches in order to achieve effective suppression of injurious processes without interfering with the reparative response. Thus, later efforts were focused on pharmacologic inhibition of selected molecular targets that mediate recruitment of leukocytes in the infarcted myocardium. Unfortunately, both anti-CD18 integrin approaches123 and complement inhibition strategies124 produced disappointing results in clinical trials raising concerns regarding the usefulness of strategies targeting the inflammatory cascade in myocardial infarction. Considering the extensive evidence supporting their effectiveness in experimental animal models, what is the basis for failure of targeted anti-inflammatory strategies in reducing ischemic cardiac injury?

First, although animal models provide important information in dissecting pathophysiologic mechanisms, their ability to predict the success of a specific approach in human patients is limited. The complexity of the clinical context cannot be simulated by experimental studies. A well-designed animal investigation aims at testing a specific hypothesis on the biological role of a mediator, or pathway, by eliminating confounding variables that may affect outcome. In the clinical context variables such as age, gender, genetic variations between individuals, the presence of comorbid conditions such as diabetes, obesity and hypertension, the timing of reperfusion and the presence of distinct patterns of coronary disease greatly complicate prediction of the potential effects of a therapeutic intervention. Studies examining the effects of aging on the post-infarction inflammatory response have provided insight into the challenges of predicting the effects of a therapeutic intervention on the basis of experimental animal studies. In senescent mice, increased dilative remodeling was associated with suppressed and prolonged inflammation, and defective scar formation due, at least in part, to impaired responses of fibroblasts to fibrogenic growth factors125. Because experimental infarction studies are almost always performed in young adult animals that exhibit robust inflammatory responses, the injurious potential of inflammatory mediators in patients with myocardial infarction may have been overstated due to extrapolation of the findings to the middle-aged or elderly human patients with myocardial infarction.

Second, the post-infarction inflammatory cascade is dependent on a complex network of molecular mediators with pleiotropic effects, dictated by contextual factors and by critical spatial and temporal variables. Inflammatory signals that may appear reasonable therapeutic targets considering their injurious role in the early stages of the inflammatory response may also be essential regulators of cardiac repair. Thus, interventions attenuating early inflammatory injury may also result in impaired healing, leading to accentuated adverse remodeling through alterations in the properties of the scar. For many anti-inflammatory strategies the possible benefit from reduction of inflammatory cardiomyocyte injury may not outweigh detrimental effects on the reparative response. Furthermore because of the distinct pathologic processes in the infarct, the border zone and the remote remodeling myocardium, spatial localization of the therapeutic intervention is a critical determinant of its success.

Third, it should be noted that the strength of experimental evidence supporting the use of anti-inflammatory approaches varies. Thus, the effectiveness of anti-complement approaches was primarily supported by neutralization studies126. Anti-integrin strategies, on the other hand, were supported by antibody inhibition studies127 and loss-of-function genetic models128. Stronger experimental evidence derived from both loss-of-function and gain-of-function approaches supports the effectiveness of inhibiting the IL-1 system following myocardial infarction10,53,129. The promising early findings from a pilot study administering anakinra, the recombinant form of the IL-1 receptor antagonist, in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction130 may reflect the higher likelihood of success of approaches with a higher level of validation.

Our growing knowledge on the regulation of the inflammatory response in the healing infarct suggests that the significance of acute inflammatory cardiomyocyte injury following myocardial infarction may have been overstated. Although early investigations using antibody neutralization strategies in large animal models suggested detrimental effects of post-infarction inflammation later studies in murine models have challenged the concept of “leukocyte-mediated cytotoxic injury” demonstrating that animals with genetic disruption of genes with a critical role in the inflammatory response (such as ICAM-1/P-selectin and IL-1RI)131,10 had no increase in infarct size despite marked attenuation of leukocyte infiltration.

Thus, direct inflammatory cardiomyocyte injury may not be significant; however a growing body of evidence suggests that disruption of inflammatory pathways may protect the heart by preventing adverse remodeling through effects on reparative cells and on matrix metabolism. Targeting the inflammatory reaction remains promising; however, the focus of our therapeutic strategies should be shifted to a new direction: to ensure optimal temporal and spatial regulation of the inflammatory response preventing uncontrolled or prolonged inflammation. From this perspective, the early disruption of key inflammatory signals attempted in some clinical trials may in fact prolong inflammation by preventing removal of dead cells and matrix debris leading to impaired wound healing, accentuated remodeling and adverse outcome. Identification of novel therapeutic targets requires intensification of our research efforts in two main areas. First, using carefully-selected experimental models we need to understand the mechanisms involved in repression and resolution of the post-infarction inflammatory response and study the relation between specific defects in negative regulation of inflammation and cardiac remodeling. Second, using suitable biomarkers we need to identify patients exhibiting defective resolution of inflammation following myocardial infarction; these subpopulations may be ideal candidates for targeted anti-inflammatory approaches to inhibit excessive or prolonged inflammation. Understanding the STOP signals involved in suppression of inflammation following infarction may be the key to prevent adverse remodeling and progression to heart failure.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING:

Dr Frangogiannis’ laboratory is funded by NIH grants R01 HL-76246 and R01 HL-85440 and by the Wilf Family Cardiovascular Research Institute.

NON-STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

DAMP

damage-associated molecular patterns

TLR

toll-like receptor

HMGB1

high mobility group box 1

RAGE

receptor for advanced glycation end-products

ROS

reactive oxygen species

NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

IL

interleukin

VCAM

vascular cell adhesion molecule

ICAM

intercellular adhesion molecule

JAM

junctional adhesion molecule

TNF

tumor necrosis factor

TGF

transforming growth factor

MCP

monocyte chemoattractant protein

M-CSF

macrophage-colony stimulating factor

IL-1Ra

Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist

Tregs

regulatory T cells

MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

TSP

thrombospondin

SHP1

SH2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 1

IRAK

interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase

MyD88

myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88

MKP-1

MAPK phosphatase 1

RIP

receptor interacting protein

ATF3

activating transcription factor 3

JAK

janus activated kinase

STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

PTP1B

protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B

TCPTP

T cell protein tyrosine phosphatase

CIS

cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein

CRP

C-reactive protein

SAP

serum amyloid protein

PTX3

pentraxin 3

DPP

dipeptidyl peptidase

DARC

Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines

SPM

specialized proresolving mediators

PD1

protectin D1

Del-1

developmental endothelial locus-1

LFA-1

leukocyte function-associated antigen-1

TIMP

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases

PAI

plasminogen activator inhibitor

GDF

growth differentiation factor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURES: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Parikh NI, Gona P, Larson MG, Fox CS, Benjamin EJ, Murabito JM, O'Donnell CJ, Vasan RS, Levy D. Long-term trends in myocardial infarction incidence and case fatality in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Framingham Heart study. Circulation. 2009;119:1203–1210. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.825364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis EF, Moye LA, Rouleau JL, Sacks FM, Arnold JM, Warnica JW, Flaker GC, Braunwald E, Pfeffer MA. Predictors of late development of heart failure in stable survivors of myocardial infarction: the CARE study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1446–1453. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)01057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling--concepts and clinical implications: a consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. Behalf of an International Forum on Cardiac Remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:569–582. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White HD, Norris RM, Brown MA, Brandt PW, Whitlock RM, Wild CJ. Left ventricular end-systolic volume as the major determinant of survival after recovery from myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1987;76:44–51. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frangogiannis NG. The immune system and cardiac repair. Pharmacol Res. 2008;58:88–111. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arslan F, Smeets MB, O'Neill LA, Keogh B, McGuirk P, Timmers L, Tersteeg C, Hoefer IE, Doevendans PA, Pasterkamp G, de Kleijn DP. Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury is mediated by leukocytic toll-like receptor-2 and reduced by systemic administration of a novel anti-toll-like receptor-2 antibody. Circulation. 2010;121:80–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.880187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann DL. The emerging role of innate immunity in the heart and vascular system: for whom the cell tolls. Circ Res. 108:1133–1145. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrassy M, Volz HC, Igwe JC, Funke B, Eichberger SN, Kaya Z, Buss S, Autschbach F, Pleger ST, Lukic IK, Bea F, Hardt SE, Humpert PM, Bianchi ME, Mairbaurl H, Nawroth PP, Remppis A, Katus HA, Bierhaus A. High-mobility group box-1 in ischemia-reperfusion injury of the heart. Circulation. 2008;117:3216–3226. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.769331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon JW, Shaw JA, Kirshenbaum LA. Multiple facets of NF-kappaB in the heart: to be or not to NF-kappaB. Circ Res. 108:1122–1132. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bujak M, Dobaczewski M, Chatila K, Mendoza LH, Li N, Reddy A, Frangogiannis NG. Interleukin-1 receptor type I signaling critically regulates infarct healing and cardiac remodeling. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:57–67. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 140:821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawaguchi M, Takahashi M, Hata T, Kashima Y, Usui F, Morimoto H, Izawa A, Takahashi Y, Masumoto J, Koyama J, Hongo M, Noda T, Nakayama J, Sagara J, Taniguchi S, Ikeda U. Inflammasome activation of cardiac fibroblasts is essential for myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 123:594–604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.982777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frangogiannis NG. Chemokines in ischemia and reperfusion. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:738–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Proudfoot AE, Handel TM, Johnson Z, Lau EK, LiWang P, Clark-Lewis I, Borlat F, Wells TN, Kosco-Vilbois MH. Glycosaminoglycan binding and oligomerization are essential for the in vivo activity of certain chemokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1885–1890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0334864100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dewald O, Ren G, Duerr GD, Zoerlein M, Klemm C, Gersch C, Tincey S, Michael LH, Entman ML, Frangogiannis NG. Of mice and dogs: species-specific differences in the inflammatory response following myocardial infarction. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:665–677. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nathan C, Ding A. Nonresolving inflammation. Cell. 140:871–882. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huynh ML, Fadok VA, Henson PM. Phosphatidylserine-dependent ingestion of apoptotic cells promotes TGF-beta1 secretion and the resolution of inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:41–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI11638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colotta F, Re F, Polentarutti N, Sozzani S, Mantovani A. Modulation of granulocyte survival and programmed cell death by cytokines and bacterial products. Blood. 1992;80:2012–2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bournazou I, Pound JD, Duffin R, Bournazos S, Melville LA, Brown SB, Rossi AG, Gregory CD. Apoptotic human cells inhibit migration of granulocytes via release of lactoferrin. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:20–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI36226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soehnlein O, Lindbom L. Phagocyte partnership during the onset and resolution of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 10:427–439. doi: 10.1038/nri2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robbins CS, Swirski FK. The multiple roles of monocyte subsets in steady state and inflammation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 67:2685–2693. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0375-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dewald O, Zymek P, Winkelmann K, Koerting A, Ren G, Abou-Khamis T, Michael LH, Rollins BJ, Entman ML, Frangogiannis NG. CCL2/Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 regulates inflammatory responses critical to healing myocardial infarcts. Circ Res. 2005;96:881–889. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163017.13772.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK, Aikawa E, Stangenberg L, Wurdinger T, Figueiredo JL, Libby P, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3037–3047. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsujioka H, Imanishi T, Ikejima H, Kuroi A, Takarada S, Tanimoto T, Kitabata H, Okochi K, Arita Y, Ishibashi K, Komukai K, Kataiwa H, Nakamura N, Hirata K, Tanaka A, Akasaka T. Impact of heterogeneity of human peripheral blood monocyte subsets on myocardial salvage in patients with primary acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frangogiannis NG, Mendoza LH, Ren G, Akrivakis S, Jackson PL, Michael LH, Smith CW, Entman ML. MCSF expression is induced in healing myocardial infarcts and may regulate monocyte and endothelial cell phenotype. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H483–H492. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01016.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena P, Sica A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:549–555. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 11:889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moser B, Loetscher P. Lymphocyte traffic control by chemokines. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:123–128. doi: 10.1038/84219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Littman DR, Rudensky AY. Th17 and regulatory T cells in mediating and restraining inflammation. Cell. 140:845–858. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ait-Oufella H, Salomon BL, Potteaux S, Robertson AK, Gourdy P, Zoll J, Merval R, Esposito B, Cohen JL, Fisson S, Flavell RA, Hansson GK, Klatzmann D, Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Natural regulatory T cells control the development of atherosclerosis in mice. Nat Med. 2006;12:178–180. doi: 10.1038/nm1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dobaczewski M, Xia Y, Bujak M, Gonzalez-Quesada C, Frangogiannis NG. CCR5 signaling suppresses inflammation and reduces adverse remodeling of the infarcted heart, mediating recruitment of regulatory T cells. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2177–2187. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ariel A, Fredman G, Sun YP, Kantarci A, Van Dyke TE, Luster AD, Serhan CN. Apoptotic neutrophils and T cells sequester chemokines during immune response resolution through modulation of CCR5 expression. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1209–1216. doi: 10.1038/ni1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J, Brown LF, Hibberd MG, Grossman JD, Morgan JP, Simons M. VEGF, flk-1, and flt-1 expression in a rat myocardial infarction model of angiogenesis. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H1803–H1811. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.5.H1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ren G, Michael LH, Entman ML, Frangogiannis NG. Morphological characteristics of the microvasculature in healing myocardial infarcts. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50:71–79. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]