Widespread RNA Editing of Embedded Alu Elements in the Human Transcriptome (original) (raw)

Abstract

More than one million copies of the ∼300-bp Alu element are interspersed throughout the human genome, with up to 75% of all known genes having Alu insertions within their introns and/or UTRs. Transcribed Alu sequences can alter splicing patterns by generating new exons, but other impacts of intragenic Alu elements on their host RNA are largely unexplored. Recently, repeat elements present in the introns or 3′-UTRs of 15 human brain RNAs have been shown to be targets for multiple adenosine to inosine (A-to-I) editing. Using a statistical approach, we find that editing of transcripts with embedded Alu sequences is a global phenomenon in the human transcriptome, observed in 2674 (∼2%) of all publicly available full-length human cDNAs (n = 128,406), from >250 libraries and >30 tissue sources. In the vast majority of edited RNAs, A-to-I substitutions are clustered within transcribed sense or antisense Alu sequences. Edited bases are primarily associated with retained introns, extended UTRs, or with transcripts that have no corresponding known gene. Therefore, _Alu_-associated RNA editing may be a mechanism for marking nonstandard transcripts, not destined for translation.

Alu elements are the most successful primate-specific retrotransposons, comprising >10% of the human genome. The propagation of Alus over the last 65 million years has contributed to the evolution, structure, and dynamics of the human genome. Transcribed by RNA polymerase III, Alu encodes no functional protein and is thought to use the reverse transcriptase of another non-LTR retrotransposon, LINE-1, to make cDNA copies and retro-transpose back to the host genome (Dewannieux et al. 2003). Although Alu insertions can be mutagenic (Deininger and Batzer 1999), the vast majority of integrated Alus have no apparent influence on the genome. No obvious function exists for Alus, but their presence in the genome has been implicated in various biological processes including ectopic recombination, creation of new exons, and donation of new regulatory elements (Batzer and Deininger 2002; Sorek et al. 2002; Makalowski 2003; Kreahling and Graveley 2004). Furthermore, Alu RNA levels have been reported to increase in response to cell stress (Chu et al. 1998; Hagan et al. 2003). Alu elements are divided into several subfamilies whose relative ages are estimated based on sequence divergence from an Alu consensus sequence. The prototype Alu structure is a tandem dimer in which two monomers are linked by an A-rich region. The genomic distribution of Alu elements is nonuniform, with a strong bias toward GC-rich and gene-rich regions (Versteeg et al. 2003; Grover et al. 2004).

The ADAR (Adenosine Deaminase that Act on RNA) family of RNA editing enzymes found in many metazoans catalyzes adenosine deamination to inosine in double-stranded RNA (dsRNA; Bass 2002). By converting AU base pairs to unstable IU wobble base pairs, ADAR can destabilize dsRNA structures (Serra et al. 2004). Recent studies have shown that ADAR activity antagonizes RNAi by preventing double-stranded RNA from entering the RNAi pathway (Scadden and Smith 2001a; Tonkin and Bass 2003). Inosine in edited RNA is recognized as guanosine by cellular machineries. Hence, the base modification can alter and diversify the protein-coding capacity of edited transcript. Editing has also been shown to modify splice sites (Rueter et al. 1999) and may affect mRNA stability, transport, and translation efficiency. Only a handful of edited transcripts have been identified in mammalian cells to date, despite the significant levels of inosine detected in mRNAs (Paul and Bass 1998; Maas et al. 2003). Most of the identified transcripts contain one or very few site-specific A-to-I base changes within their coding regions, as exemplified by GluR (Higuchi et al. 1993) and serotonin receptor pre-mRNAs (Burns et al. 1997). In contrast, multiple A-to-I modifications are observed in some viral RNAs, particularly the hyper-mutations found in certain minus-strand virus genomes. A recent method developed to find edited RNA unexpectedly revealed 19 transcripts from human brain with multiple edited bases in noncoding regions, raising the possibility that this type of editing might be more common than single base editing within coding regions (Morse et al. 2002). Interestingly, 15 of those 19 transcripts were edited within repetitive elements present in introns or UTRs.

Even with these newly identified targets, there appears to be significantly more inosine in the poly(A) fraction of RNA than can be easily accounted for (Maas et al. 2003). The universal presence of repetitive elements, their potential to form extensive dsRNA structures, and the ubiquity of ADAR expression suggest that editing within repeats might be widespread and could affect numerous genes. An exhaustive screening of RNA pools for inosine-containing transcripts poses a daunting task with limited efficacy. An alternative approach is to examine the enormous amount of cDNA sequence data amassed in the public database, because potentially edited bases can be identified by sequence discrepancies between genomic DNA and corresponding cDNA, where G takes the place of A at the edited site.

We have used a statistical approach to determine that multiple edited bases occur within interspersed repeat elements at the genome-wide scale. We report the widespread overabundance of A-to-G substitutions in human full-length cDNAs, which is best explained by A-to-I editing. Most of the edited bases coincide with Alu sequences embedded within larger host RNAs, including mRNAs, partially processed mRNAs, and polyadenylated RNAs that do not encode proteins. These findings indicate prevalent RNA editing of embedded Alu sequences in the human transcriptome and suggest novel impacts of intragenic Alus on their host genes at the RNA level.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

An Excess of A-to-G Substitutions in Human Full-Length cDNAs

To look specifically for multiple-edited targets, we compared the sequences of human full-length cDNAs to the reference genome sequence, and noted clusters of A-to-G substitutions. Expressed sequence tags (ESTs) were not used for this study because of their variable sequence quality. In contrast, full-length cDNAs, generated by a method that captures both the 5′-cap structure and 3′-poly(A) stretch, represent complete copies of mRNAs and are >99.99% accurate (Ota et al. 2004). Therefore, the major expected source of sequence variation would be single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). To maximize the distinction between SNPs and edited bases, we used a scan statistic method optimized to find clusters of A-to-G substitutions within one or more region of a given transcript. When each type of substitution (12 overall types) was tabulated and summed for all 128,406 full-length cDNAs, we found an overwhelming excess of A-to-G base changes (n = 109,732), which was ∼45,000 more than the analogous pyrimidine transition, T-to-C (n = 62,118; Fig. 1A). For known SNPs, the substitution rate observed for these two transitions is similar (p < 10-15; Supplemental Table 1). After subtracting out the A-to-G excess, the overall frequency of observed substitutions (1.4 per kilobase) was still somewhat higher than the predicted frequency of SNPs in human exons (0.9 per kilobase; Sachidanandam et al. 2001). This may be caused by a combination of errors from transcription, reverse transcription, and sequencing.

Figure 1.

Histograms of transition substitutions from the reference genomic DNA to full-length cDNA. Only transitions, whose frequencies are generally threefold to fourfold higher than transversions, are shown. (A) Total number of transition substitutions in 128,406 cDNAs (total of 254,330,565 bases). (B) Number of cDNAs with a significantly increased likelihood of specific substitutions, as determined by our scan statistic method (see Methods). There is a population of transcripts with excessive A-to-G substitutions that are not apparent in other transitions. A-to-G substitution: 2674 significant transcripts; G-to-A substitution: 35 significant transcripts; T-to-C substitution: 36 significant transcripts; C-to-T substitution: 52 significant transcripts.

The surplus A-to-G substitutions were accumulated in a subset of cDNAs rather than distributed uniformly throughout all transcripts. Surprisingly, we identified >2600 potentially multiple-edited (herein, termed “edited” for brevity) transcripts that had significantly more A-to-G substitutions than expected (false discovery rate <0.01), relative to all other transcripts and to all other substitutions (Fig. 1B). The characterization of individual transcripts can be viewed in Supplemental Table 2.

Within the 2674 selected cDNAs, A-to-G substitutions (n = 35,085) accounted for 84% of all substitutions (n = 41,848; Table 1). In comparison, within the 125,732 unselected cDNAs, A-to-G substitutions (n = 74,647) accounted for only 20% of all substitutions (n = 380,985). In the selected transcripts, the number of A-to-G substitutions per transcript ranged from 5 to 107, with a mean of 13.12 and a median of 10, whereas the number of the other 11 substitutions combined per transcript ranged from 0 to 37, with a mean of 2.53 and a median of 2. Thus, the selected cDNAs have a disproportionately high number of A-to-G changes (average of 13.12 per transcript for the selected cDNAs vs. 0.59 for the unselected) but show a similar frequency of base changes compared with unselected transcripts for the 11 other substitutions combined (average of 2.53 per transcript for the selected cDNAs vs. 2.44 for the unselected).

Table 1.

Distribution of A-to-G Substitutions Within 2674 Selected Transcripts

| Repeat element-type | No. of repeat elements | Total bases (% of total) | A-to-G substitutions (% of total) | Distribution of A-to-G substitutions in repeat elements (minimum, 25th percentile, median, 75th percentile, maximum) | Other 11 substitutions combined (% of total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alu | 6763 | 1,570,185 (20.7%) | 30,744 (87.6%) | 0,0,4,7,34 | 2017 (26.4%) |

| Other repeatsa | 6840b | 1,472,934 (19.4%) | 1826 (5.2%) | 0,0,0,0,63 | 1396 (18.3%) |

| Non-repeatsc | — | 4,555,872 (59.9%) | 2515 (7.2%) | — | 4235 (55.4%) |

| Total | 13603b | 7,598,991 | 35,085 | — | 6763 |

Correlation Between A-to-G Substituted Bases and Alu Sequences

The A-to-G substitutions in the selected transcripts were not randomly distributed but showed a striking correlation with embedded Alu sequences. Almost 88% of all A-to-G substitutions occurred within Alu sequences present in these RNAs, although Alu sequences comprised only 20% of the total length of these transcripts (p < 10-15; Table 1). On the contrary, the other types of substitutions showed a random distribution. Of all substitutions within Alus, A-to-G substitutions accounted for 94% (n = 30,744), whereas all other 11 substitutions contributed only 6% (n = 2017, p < 10-15). Edited sequences were also observed, at much lower frequencies, in LINE-1 and other interspersed repeats, as well as in nonrepetitive sequences (Table 1). Given the statistical improbability for numerous transcripts to randomly cluster A-to-G substitutions almost exclusively within embedded repeat sequences, as well as the experimental observation of inosine within Alus in some brain transcripts (Morse et al. 2002), we believe that the selected transcripts represent genuinely edited RNAs. Other explanations for the overabundance of targeted A-to G substitutions are implausible. Almost all Alus, except for the youngest _Alu_Y subfamily, are fixed in the human population (Batzer and Deininger 2002). Therefore, the observed overabundance of A-to-G substitutions within Alus cannot be explained by polymorphic Alu insertions. In addition, the ratio of different subfamilies showing Alu editing completely matched their overall genomic distribution. To determine whether Alu DNA sequences are hypermutable for A-to-G transitions, we analyzed nearly one million repeat-element-derived SNPs deposited in the dbSNP database and found no excess of A-to-G substitutions (Supplemental Table 1). Furthermore, the observed A-to-G changes are not likely due to recombination between Alus at different genomic loci. We performed BLAST searches of the human genome sampling 100 Alu sequences with five or more A-to-G substitutions. In each case, the original locus was clearly the best match.

Editing Patterns Within Alu Sequences

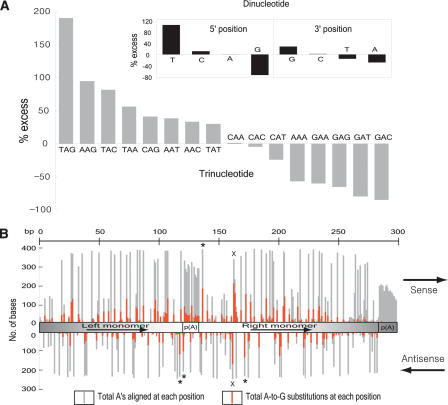

Why might Alu sequences be major targets for RNA editing? Although it is conceivable that targeting is based on particular nucleotide motifs intrinsic to Alu sequences, considering the nature of ADARs to recognize and bind any dsRNA structure, an a priori explanation is the capacity for Alus within a primary transcript to form extended RNA duplexes (Kikuno et al. 2002; Morse et al. 2002). The enormous number of Alus present in either orientation within transcribed regions makes the intramolecular formation of dsRNA by inverted Alu repeats the most plausible scenario, although dsRNA formation in trans is also possible. ADARs act on dsRNA without apparent sequence-specific binding, but they do show certain neighbor base preferences. To characterize editing preferences within Alu sequences, we carried out a nearest-neighbor analysis one base upstream or downstream of all substituted sites within Alus. There was substantial under representation of Gs and overrepresentation of Ts one base 5′ to the edited base, as well as a slight excess of Gs and paucity of As one base 3′ to the edited base. Specific trinucleotides were also relatively favored (TAG, AAG) or disfavored (GAN, AAA; Fig. 2A). These findings are in accord with previous experiments in which purified ADARs were mixed with model dsRNA substrates in vitro, and edited sites were determined (Polson and Bass 1994; Lehmann and Bass 2000). However, one notable difference is an exceptional preference for T as the 5′-neighbor. Given our large sample size, the observed pattern of preferences should help predict potential editing sites in other contexts.

Figure 2.

Analysis of preferred editing patterns within Alu sequences. (A) Nearest-neighbor preferences derived from 2868 Alu sequences with at least five A-to-G substitutions (n = 25,493 total edited bases) in either orientation. We determined the observed and expected frequencies of di- and tri-nucleotide patterns using the edited version of Alu sequences and their corresponding genomic sequences, respectively. We calculated percentage excess using the formula, [(observed frequency) - (expected frequency)]/(expected frequency) × 100. Previous studies (Polson and Bass 1994; Lehmann and Bass 2000) showed 5′ preferences of T ≈ A > C > G and T = A > C = G for ADAR1 and ADAR2, respectively; and 3′ preferences of nothing apparent and T = G > C = A for ADAR1 and ADAR2, respectively. (B) Identification of potential hotspots for editing within the Alus family consensus sequence, generated by separate alignments of 412 sense and 260 antisense sequences with at least 10 A-to-G substitutions using CLUSTALW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw). We used Alus with 10 or more A-to-G substitutions to get a reasonable input size for alignment and thus minimize the effects of alignment artifacts. The number of As aligned at each position is not uniform because of sequence divergence in individual Alus. The upper panel represents the sense strand and the bottom panel the antisense strand. The basic Alu structure, as shown in the middle, consists of two nonidentical direct repeats (left and right monomer), linked by a central A-rich region. The right monomer is followed by a 3′-poly(A) that is required for Alu replication. The most frequently edited trinucleotide motif, TAG, is labeled with an *. The right monomer hotspot, present on both strands (containing a palindromic TA), is labeled with ×. Sense strands are in general more prone to editing than antisense strands, probably because of differences in availability of As (80 As and 44 As on sense and antisense Alus consensus sequence, respectively).

To identify editing hotspots within Alu sense or antisense sequences, we compiled the position of edited bases for Alus, the largest subfamily of Alu elements (Fig. 2B). The overall pattern of editing is bell-shaped, hinting that the central region of the Alu RNA duplex may exhibit higher stability and thus serve as a better substrate for ADAR activity. In support of this idea, the central A-rich linker in Alus is a target for editing, but the 3′-poly(A) tail is not. There are several positions particularly prone to editing. For instance, a region in the right monomer, with the sense:antisense sequence of 5′-TGT(A/G)(A/G)T-3′ and 5′-ATT(A/G)CA-3′ contains the highest absolute numbers of edited bases. The palindromic dinucleotide TA has the highest likelihood of editing on both strands, consistent with ADARs being dsRNA-specific, and implying that these enzymes might edit both strands concurrently.

Reduced Frequency of Edited Transcripts in Mouse

The mouse genome is devoid of Alus, which arose during primate radiation. It does contain other repeats, particularly four families of unrelated short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs), whose total copy number is similar to that of Alus in the human genome (Lander et al. 2001; Waterston et al. 2002). We performed a parallel scan for A-to-G clusters among 112,435 full-length mouse cDNAs and found only 91 transcripts with significantly increased A-to-G substitutions (false discovery rate <0.01). Also, 61 transcripts had evidence of editing within interspersed repeat sequences, the majority being SINEs (Supplemental Table 3). Assuming comparable levels of ADAR activity in human and mouse, the pronounced disparity in frequency may be explained by the differences in repeat length (∼300 bp vs. ∼150 bp for human _Alu_ and mouse SINE, respectively), the copy number of each distinct mouse SINE lineage (∼one-fourth the frequency of _Alus_), and the degree of sequence homogeneity (average divergence <10% vs. >20% for human Alu and mouse SINE, respectively). Thus, from an evolutionary perspective, dimerization of the Alu structure (doubling of Alu length by fusing left and right monomers) and the subsequent burst of Alu retrotransposition during early primate evolution (Batzer and Deininger 2002) have likely contributed to the elevated level of repeat-associated RNA editing in humans.

Tissue Distribution of Edited Transcripts

The ubiquitous expression of ADAR1 and ADAR2 has raised a question as to the existence of possible targets in tissues other than brain, where most edited transcripts have been discovered (Maas et al. 2003). Our analysis indicates that A-to-I editing occurs in at least 30 different organs. The greatest number of edited cDNAs (n = 854) are derived from different brain libraries, where they comprise ∼5% of these cDNAs. However, several other tissues show higher frequencies of edited transcripts than the brain, including thymus, prostate, spleen, and kidney (Table 2). Even within the brain, different regions showed widely different frequencies of editing, ranging from the cerebellum (12.1%; 181/1497 from three libraries) to the hippocampus (4.5%; 116/2007 from four libraries).

Table 2.

Tissue Distribution of the Selected (n = 2674) Transcripts

| Tissue | No. of libraries | No. of cDNAs | Edited cDNAs | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thymus | 5 | 1234 | 158 | 12.80 |

| Prostate | 7 | 1232 | 101 | 8.20 |

| Spleen | 5 | 1440 | 113 | 7.85 |

| Tongue | 3 | 669 | 43 | 6.43 |

| Mammary gland | 4 | 789 | 45 | 5.70 |

| Peripheral nervous system | 3 | 322 | 18 | 5.59 |

| Larynx | 6 | 1287 | 69 | 5.36 |

| Kidney | 14 | 2866 | 146 | 5.09 |

| Brain | 52 | 18,649 | 854 | 4.58 |

| Uterus | 10 | 3316 | 142 | 4.28 |

| Stomach | 3 | 395 | 16 | 4.05 |

| Other | 13 | 1538 | 48 | 3.12 |

| Eye | 5 | 1963 | 53 | 2.70 |

| Embryo | 2 | 1421 | 37 | 2.60 |

| Lymph node | 6 | 1491 | 38 | 2.55 |

| Small intestine | 8 | 1801 | 45 | 2.50 |

| Cervix | 2 | 891 | 22 | 2.47 |

| Lung | 11 | 3301 | 53 | 1.61 |

| Bone marrow | 4 | 872 | 14 | 1.61 |

| Colon | 8 | 2217 | 35 | 1.58 |

| Heart | 8 | 866 | 13 | 1.50 |

| Ovary | 7 | 1189 | 16 | 1.35 |

| Testis | 10 | 9064 | 104 | 1.15 |

| Bladder | 3 | 479 | 5 | 1.04 |

| Liver | 6 | 2049 | 21 | 1.02 |

| Placenta | 12 | 4317 | 44 | 1.02 |

| Mixed | 5 | 1506 | 13 | 0.86 |

| No information | 52 | 37,377 | 275 | 0.74 |

| Skin | 10 | 2761 | 12 | 0.43 |

| Blood | 7 | 3134 | 11 | 0.35 |

| Muscle | 6 | 1979 | 6 | 0.30 |

| Pancreas | 4 | 752 | 2 | 0.27 |

| Bone | 1 | 50 | 0 | 0.00 |

Owing to the wide variability in cDNA sequence acquisition methods, these numbers should be considered preliminary. Using a sample of 38,044 transcripts (including 659 edited transcripts) in which information about tissue or cell line source and normalization procedures were reported, we found about twofold increased frequencies of edited transcripts in tissue samples over cell line samples, normalized libraries over nonnormalized, and normal cells over malignant cells (each with p < 0.001; data not shown). Although these differences may reflect varying degrees of ascertainment bias, they may be indicators of more biologically meaningful differences (Maas et al. 2001).

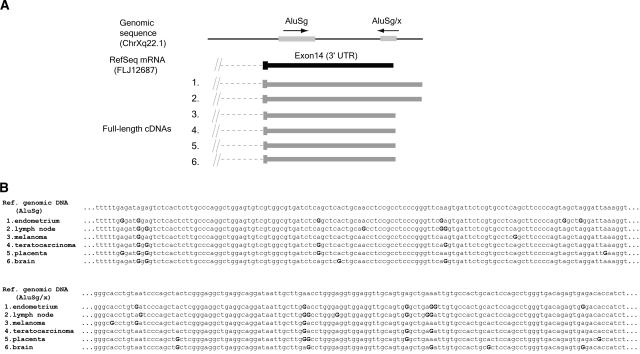

To characterize editing patterns within a given genomic locus from different tissues, we examined several loci where multiple independent overlapping transcripts showed significant A-to-G substitutions. Approximately 10% of our 2674 edited transcripts were of this type. We found that transcripts from independent tissue sources showed different editing patterns, and the positions of edited bases were only partially superimposable (Fig. 3). This suggests that editing of embedded Alu RNA sequences is stochastic, depending on particular local conditions (i.e., availability of ADAR and RNA structures) at the time of processing.

Figure 3.

Example of a locus with multiple-edited transcripts from different tissues. (A) The position and orientation of Alu elements at the corresponding chromosomal location are shown at the top. Below the genomic location is the RefSeq mRNA, in black. Exons are wide blocks, UTRs are narrower blocks, and introns are dashed lines. Accession numbers for the transcripts shown are NM024917 for RefSeq mRNA, and (1) BX647969, (2) AL832849, (3) BC008067, (4) AK022749, (5) BC009437, (6) BC034272 for full-length cDNAs. (B) Partial alignment of the cDNAs overlapping with Alu sequences. A-to-G substituted bases are labeled with a boldface G. No other types of substitutions were present within the listed transcripts.

Note: While our paper was in review, we learned that another group had reached a similar result using a different statistical approach (Levanon et al. 2004). They sequenced the cDNAs derived from multiple tissues of several genes, and confirmed that editing of embedded Alu RNA sequences showed variable patterns from tissue to tissue.

Characterization of Edited Transcripts

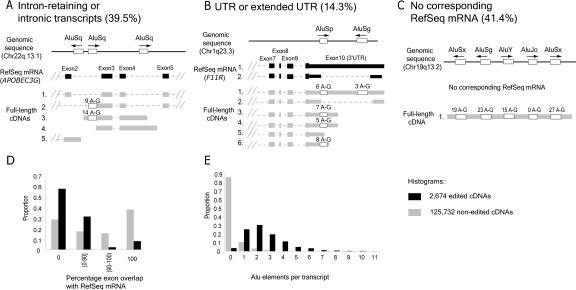

What do edited transcripts represent? When compared with the nonredundant gene-oriented set of transcripts in the UniGene database, the edited transcripts encompass 1879 independent transcription units, corresponding to 6.6% of all annotated RNA clusters described by full-length cDNAs. Inspection of individual edited transcripts, however, revealed a strong deviation from known gene structures. Edited exons, or blocks, corresponded to (1) retained introns, either overlapping with exon(s) of a known gene or completely intronic (Fig. 4A); (2) UTRs or extended UTRs, in which a transcript continues beyond the known UTR structure (Fig. 4B); or (3) transcripts that do not correspond to known genes in the RefSeq database (Fig. 4C). Among the 2674 edited transcripts, only 61% and 76% of edited exons retained canonical GU and AG splice sites, respectively, compared with 95% and 96% of nonedited exons. Furthermore, although 54% of nonedited cDNAs overlap by >90% to exon regions of known genes, only 10% of edited cDNAs belong to this subset (Fig. 4D). Edited transcripts are enriched for Alu sequences; 96% of edited cDNAs contained one or more Alu sequence, compared with 15% of nonedited transcripts (Fig. 4E). Taken together, edited transcripts seem to embody a subset of widely distributed nonstandard transcripts in the human transcriptome.

Figure 4.

Characterization of edited transcripts. Below the genomic location is the RefSeq mRNA, in black. Exons are wide blocks, UTRs are narrower blocks, and introns are dashed lines. Alu sequences present within edited transcripts are empty blocks, and the number of A-to-G substitutions is shown above each block. Other (A) APOBEC3G locus exemplifies intron-retaining transcripts. Accession numbers for the transcripts shown are NM021822 for RefSeq mRNA, and (1) AF182420, (2) AK092614, (3) AX748234, (4) AK022802, (5) BC061914 for full-length cDNAs. (B) The F11R locus exemplifies _Alu_-associated editing within a UTR. Of note, the positions of edited bases for the four edited transcripts were only partially overlapping. The accession numbers are (1) NM016946, (2) NM144501 for RefSeq mRNAs, and (1) AF172398, (2) AL136649, (3) AK026665, (4) BC001533, (5) AY154005, (6) AY358896 for full-length cDNAs. (C) AK126984 exemplifies transcripts that have no corresponding known gene. This particular transcript is extensively edited in four of five Alus. (D) Deviation from known gene structure measured as percentage exon overlap with RefSeq mRNA. (E) Edited transcripts are enriched in Alu elements. The distribution of edited versus nonedited transcripts in each of the histograms was determined to be significantly different (p < 10-9).

Editing and splicing may be coordinated events in mammalian cells, with pre-mRNAs exposed to ADARs at the time of their processing (Raitskin et al. 2001; Bratt and Ohman 2003). Although we do not find evidence that editing has directly altered splice sites, base modifications of Alu duplexes could change local RNA structures and hinder the normal splicing process. Conversely, the sheer number of Alus present in intragenic regions and their near universal tendency to be removed from premRNAs suggest that editing could mark certain aberrant RNAs for nuclear retention and/or degradation. Cellular machineries exist that process multiple-inosine-containing RNAs. For example, extensively edited transcripts are retained in the nucleus by a protein complex consisting of p54nrb, PSF, and matrin 3 (Zhang and Carmichael 2001). In addition, a cytoplasmic ribonuclease activity that specifically cleaves multiple-edited RNA has been reported (Scadden and Smith 2001b). In both cases, the key requisite for protein-RNA interaction is hyperedited bases, whereas a single A-to-I modified RNA is not a target. Despite the exquisite specificity of these systems, endogenous targets have yet to be identified. It would be of interest to see whether multiple-edited _Alu_-containing RNAs serve as targets for these regulatory proteins.

The true proportion of edited transcripts in the human transcriptome cannot be estimated based on this cDNA survey for several reasons, including the arbitrary minimum threshold inherent in a statistical approach, the likely differential stability of multiple-inosine-containing transcripts and their partitioning between the nucleus and cytoplasm, as well as the variability in methods used to generate cDNA libraries. Nonetheless, given the ubiquity of Alu elements and ADARs, edited transcripts are likely to constitute a sizable and widespread population of RNAs. A recent study indicates that the human transcriptome is much more complex than commonly considered, having ∼50% novel transcripts that do not correspond to known genes or ESTs (Kampa et al. 2004). The presence of edited transcripts adds to our appreciation of this complexity. The editing targets identified in the current study may represent a small portion of this “hidden” transcriptome. Consistent with this idea, only two of the 15 previously found _Alu_-associated editing targets (Morse et al. 2002) overlapped with our selected transcripts.

dsRNAs longer than 30 bp induce dsRNA-dependent pathways in mammalian cells such as the interferon response, with activation of PKR and 2′,5′-oligoadenylate (Samuel 2001). Similar to their role in antagonizing RNAi by destabilizing dsRNA (Scadden and Smith 2001a; Tonkin and Bass 2003), ADARs might alleviate the dsRNA pressure generated by inverted Alus, probably the biggest reservoir of dsRNAs in the cell. Interferon-induced up-regulation of ADAR1 in lymphocytes leads to an increase of inosine in mRNAs up to 5% of all As (Yang et al. 2003). Thus, the existence of a large pool of targets edited within Alu sequences could account for the abundance of inosine found in poly(A) RNAs from many different tissues (Paul and Bass 1998; Maas et al. 2003). The presence of Alu sequences within noncoding portions of genes may have an impact on expression of host genes. Recent reports concerning full-length LINE elements within introns in the human genome suggest that they too subtly influence the level of host RNAs by affecting the rate of synthesis through a gene by RNA polymerase II (Perepelitsa-Belancio and Deininger 2003; Han et al. 2004). Identification of potential functions and regulation of _Alu_-associated RNA editing are future challenges in understanding this novel intersection of RNA-modification and retrotransposon biology.

METHODS

Statistical Identification of Potentially Edited Transcripts

We obtained all human and mouse full-length cDNA sequences from the UCSC Genome Browser database (http://genome.ucsc.edu, as of December 2003; versions hg16 and mm4 for human and mouse, respectively), and aligned them against their reference genome sequences (July 2003 freeze of the human genome; October 2003 freeze of the mouse genome) using BLAT (http://genome.ucsc.edu), setting a minimum threshold of 95% sequence identity. For alignments that matched to multiple locations in the genome, we selected the one with the highest alignment score, which gave us a final working set of 128,406 and 112,435 nonredundant alignments for human and mouse, respectively. We tabulated each type of substitutions as well as matches (16 sets overall), with respect to the reference genome, for each transcript, but did not consider insertions or deletions. All data generated in this study or acquired from other sources were parsed and loaded onto a MySQL database to facilitate efficient analyses. Because A-to-G changes clustered within small regions, as opposed to more randomly distributed SNPs and sequence errors, we used a scan statistic method to look for clusters of A-to-G substitutions in each transcript (Glaz et al. 2001). For each transcript, we applied a weighted mean of observed rates of all substitutions other than A-to-G to generate an expected rate of A-to-G substitutions for that transcript; the relative weights were proportional to the overall rate of each type of substitution over all transcripts in the study. In this way, a higher rate of A-to-G substitutions would be expected in a transcript with a higher overall error rate. For all transcripts, however, we used a minimum expected substitution rate of 9.34 × 10-4, the mean overall substitution rate of the other three transitions. For each transcript, we generated a reduced transcript consisting only of the genomic A bases. We then recorded for each transcript the scan statistic of the maximum number of A-to-G substitutions in a sliding window of size 80 (or for the entire reduced transcript if the length was <80). The window size of 80 was chosen because 80 As approximated the number of As within an Alu repeat. The probability for each transcript of the observed scan statistic was calculated using the formula of Naus (1982). Because of the multiple comparisons issue caused by the large number of transcripts, we did not use a traditional threshold for the _p_-values.

Instead, based on the _p_-values, we selected the transcripts to limit the false discovery rate (q) to 0.01 (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995; Storey and Tibshirani 2003). Transcripts with fewer than five A-to-G substitutions or <50% A-to-G substitutions among all substitutions were removed to reduce false positives generated by the scan statistic method. Of all the transcripts in which we believe editing has taken place, we expect that <1% are false positives. Computations were done using the R statistical environment with the _q_-value package (Storey 2002; Team 2003). We identified the location of interspersed repeat elements (excluding simple low complexity repeats and satellites) in each transcript by RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org).

Repeat-Element-Derived SNP Analysis

We obtained 704,418 repeat element-SNPs from the dbSNP database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP, Build #119). Because the direction of the nucleotide change is unknown in this data set, we categorized them into six different polymorphic allele types and calculated the frequency of each allele. Similarly, we obtained an additional 175,097 _Alu_-derived SNPs with known direction of nucleotide change, separated them into 12 different substitution patterns, and tallied the frequency of each substitution (see Supplemental Table 1).

Characterization of Edited Transcripts

We downloaded tissue, library, histology, normalization protocol, and preparation method information from the UCSC Table Browser as well as the Cancer Genome Anatomy Project (CGAP; http://cgap.nci.nih.gov). We simplified tissue categories according to the UniGene (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=unigene) tissue classification system. For example, libraries derived from different parts of the brain were combined into a single brain category. To minimize the ascertainment bias, we only used libraries with at least 50 cDNAs for Table 2. We used the UniGene database (Build #164 for Homo sapiens) to cluster edited transcripts that mapped to the same genomic location. We manually inspected each edited transcript using the UCSC Genome Browser and categorized them into three major classes as described in the text. We examined the extent of deviation of edited transcripts from the known gene structure by calculating the percentage exon overlap with RefSeq mRNA (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/RefSeq).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by R01GM60534 (A.G.) and U24MH068457 (S.B.) from the Public Health Service. We thank Xuemei Chen, Marc Gartenberg, Sam Gunderson, Mike Kiledjian, Joseph Naus, Harold Sackrowitz, Steven Sherry, Bento Soares, Ruth Steward, and Susan Wessler for helpful discussions and/or evaluation of the manuscript.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available online at www.genome.org.\]

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.2855504.

References

- Bass, B.L. 2002. RNA editing by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71**:** 817-846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batzer, M.A. and Deininger, P.L. 2002. Alu repeats and human genomic diversity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3**:** 370-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y. and Hochberg, Y. 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate—A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. Ser. B—Methodological 57**:** 289-300. [Google Scholar]

- Bratt, E. and Ohman, M. 2003. Coordination of editing and splicing of glutamate receptor pre-mRNA. RNA 9**:** 309-318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns, C.M., Chu, H., Rueter, S.M., Hutchinson, L.K., Canton, H., Sanders-Bush, E., and Emeson, R.B. 1997. Regulation of serotonin-2C receptor G-protein coupling by RNA editing. Nature 387**:** 303-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, W.M., Ballard, R., Carpick, B.W., Williams, B.R., and Schmid, C.W. 1998. Potential Alu function: Regulation of the activity of double-stranded RNA-activated kinase PKR. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18**:** 58-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, P.L. and Batzer, M.A. 1999. Alu repeats and human disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 67**:** 183-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewannieux, M., Esnault, C., and Heidmann, T. 2003. LINE-mediated retrotransposition of marked Alu sequences. Nat. Genet. 35**:** 41-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaz, J., Naus, J.I., and Wallenstein, S. 2001. Scan statistics. Springer, New York.

- Grover, D., Mukerji, M., Bhatnagar, P., Kannan, K., and Brahmachari, S.K. 2004. Alu repeat analysis in the complete human genome: Trends and variations with respect to genomic composition. Bioinformatics 20**:** 813-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, C.R., Sheffield, R.F., and Rudin, C.M. 2003. Human Alu element retrotransposition induced by genotoxic stress. Nat. Genet. 35**:** 219-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.S., Szak, S.T., and Boeke, J.D. 2004. Transcriptional disruption by the L1 retrotransposon and implications for mammalian transcriptomes. Nature 429**:** 268-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, M., Single, F.N., Kohler, M., Sommer, B., Sprengel, R., and Seeburg, P.H. 1993. RNA editing of AMPA receptor subunit GluR-B: A base-paired intron-exon structure determines position and efficiency. Cell 75**:** 1361-1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampa, D., Cheng, J., Kapranov, P., Yamanaka, M., Brubaker, S., Cawley, S., Drenkow, J., Piccolboni, A., Bekiranov, S., Helt, G., et al. 2004. Novel RNAs identified from an in-depth analysis of the transcriptome of human chromosomes 21 and 22. Genome Res. 14**:** 331-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuno, R., Nagase, T., Waki, M., and Ohara, O. 2002. HUGE: A database for human large proteins identified in the Kazusa cDNA sequencing project. Nucleic Acids Res. 30**:** 166-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreahling, J. and Graveley, B.R. 2004. The origins and implications of Aluternative splicing. Trends Genet. 20**:** 1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander, E.S., Linton, L.M., Birren, B., Nusbaum, C., Zody, M.C., Baldwin, J., Devon, K., Dewar, K., Doyle, M., FitzHugh, W., et al. 2001. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409**:** 860-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, K.A. and Bass, B.L. 2000. Double-stranded RNA adenosine deaminases ADAR1 and ADAR2 have overlapping specificities. Biochemistry 39**:** 12875-12884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levanon, E.Y., Eisenberg, E., Yelin, R., Nemzer, S., Hallegger, M., Shemesh, R., Fligelman, Z.Y., Shoshan, A., Pollock, S.R., Sztybel, D., et al. 2004. Systematic identification of abundant A-to-I editing sites in the human transcriptome. Nat. Biotech. 22**:** 1001-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas, S., Patt, S., Schrey, M., and Rich, A. 2001. Underediting of glutamate receptor GluR-B mRNA in malignant gliomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98**:** 14687-14692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas, S., Rich, A., and Nishikura, K. 2003. A-to-I RNA editing: Recent news and residual mysteries. J. Biol. Chem. 278**:** 1391-1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makalowski, W. 2003. Genomics. Not junk after all. Science 300**:** 1246-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse, D.P., Aruscavage, P.J., and Bass, B.L. 2002. RNA hairpins in noncoding regions of human brain and Caenorhabditis elegans mRNA are edited by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99**:** 7906-7911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naus, J.I. 1982. Approximations for distributions of scan statistics. J. Am. Stat. Ass. 77**:** 177-183. [Google Scholar]

- Ota, T., Suzuki, Y., Nishikawa, T., Otsuki, T., Sugiyama, T., Irie, R., Wakamatsu, A., Hayashi, K., Sato, H., Nagai, K., et al. 2004. Complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 full-length human cDNAs. Nat. Genet. 36**:** 40-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul, M.S. and Bass, B.L. 1998. Inosine exists in mRNA at tissue-specific levels and is most abundant in brain mRNA. EMBO J. 17**:** 1120-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perepelitsa-Belancio, V. and Deininger, P. 2003. RNA truncation by premature polyadenylation attenuates human mobile element activity. Nat. Genet. 35**:** 363-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polson, A.G. and Bass, B.L. 1994. Preferential selection of adenosines for modification by double-stranded RNA adenosine deaminase. EMBO J. 13**:** 5701-5711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raitskin, O., Cho, D.S., Sperling, J., Nishikura, K., and Sperling, R. 2001. RNA editing activity is associated with splicing factors in lnRNP particles: The nuclear pre-mRNA processing machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98**:** 6571-6576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueter, S.M., Dawson, T.R., and Emeson, R.B. 1999. Regulation of alternative splicing by RNA editing. Nature 399**:** 75-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachidanandam, R., Weissman, D., Schmidt, S.C., Kakol, J.M., Stein, L.D., Marth, G., Sherry, S., Mullikin, J.C., Mortimore, B.J., Willey, D.L., et al. 2001. A map of human genome sequence variation containing 1.42 million single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nature 409**:** 928-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, C.E. 2001. Antiviral actions of interferons. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14**:** 778-809, table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scadden, A.D. and Smith, C.W. 2001a. RNAi is antagonized by A→I hyper-editing. EMBO Rep. 2**:** 1107-1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 2001b. Specific cleavage of hyper-edited dsRNAs. EMBO J. 20**:** 4243-4252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra, M.J., Smolter, P.E., and Westhof, E. 2004. Pronounced instability of tandem IU base pairs in RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 32**:** 1824-1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorek, R., Ast, G., and Graur, D. 2002. _Alu_-containing exons are alternatively spliced. Genome Res. 12**:** 1060-1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey, J.D. 2002. A direct approach to false discovery rates. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. Ser. B—Stat. Meth. 64**:** 479-498. [Google Scholar]

- Storey, J.D. and Tibshirani, R. 2003. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100**:** 9440-9445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team, R.D.C. 2003. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

- Tonkin, L.A. and Bass, B.L. 2003. Mutations in RNAi rescue aberrant chemotaxis of ADAR mutants. Science 302**:** 1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versteeg, R., van Schaik, B.D., van Batenburg, M.F., Roos, M., Monajemi, R., Caron, H., Bussemaker, H.J., and van Kampen, A.H. 2003. The human transcriptome map reveals extremes in gene density, intron length, GC content, and repeat pattern for domains of highly and weakly expressed genes. Genome Res. 13**:** 1998-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterston, R.H., Lindblad-Toh, K., Birney, E., Rogers, J., Abril, J.F., Agarwal, P., Agarwala, R., Ainscough, R., Alexandersson, M., An, P., et al. 2002. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature 420**:** 520-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.H., Luo, X., Nie, Y., Su, Y., Zhao, Q., Kabir, K., Zhang, D., and Rabinovici, R. 2003. Widespread inosine-containing mRNA in lymphocytes regulated by ADAR1 in response to inflammation. Immunology 109**:** 15-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. and Carmichael, G.G. 2001. The fate of dsRNA in the nucleus: A p54(nrb)-containing complex mediates the nuclear retention of promiscuously A-to-I edited RNAs. Cell 106**:** 465-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WEB SITE REFERENCES

- http://cgap.nci.nih.gov; Cancer Genome Anatomy Project (CGAP).

- http://genome.ucsc.edu; UCSC Genome Browser database.

- http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw; CLUSTALW.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=unigene; UniGene.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/RefSeq; RefSeq.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP; dbSNP database.

- http://www.repeatmasker.org; RepeatMasker.