Deletion of the H19 differentially methylated domain results in loss of imprinted expression of H19 and Igf2 (original) (raw)

Abstract

Differentially methylated sequences associated with imprinted genes are proposed to control genomic imprinting. A 2-kb region located 5′ to the imprinted mouse H19 gene is hypermethylated on the inactive paternal allele throughout development. To determine whether this differentially methylated domain (DMD) is required for imprinted expression at the endogenous locus, we have generated mice harboring a 1.6-kb targeted deletion of the DMD and assayed for allelic expression of H19 and the linked, oppositely imprinted Igf2 gene. H19 is activated and Igf2 expression is reduced when the DMD deletion is paternally inherited; conversely, upon maternal transmission of the mutation, H19 expression is reduced and Igf2 is activated. Consistent with the DMD’s hypothesized role of setting up the methylation imprint, the mutation also perturbs allele-specific methylation of the remaining H19 sequences. In conclusion, these experiments show that the H19 hypermethylated 5′ flanking sequences are required to silence paternally derived H19. Additionally, these experiments demonstrate a novel role for the DMD on the maternal chromosome where it is required for the maximal expression of H19 and the silencing of Igf2. Thus, the H19 differentially methylated sequences are required for both H19 and Igf2 imprinting.

Keywords: Differentially methylated domain, DNA methylation, H19, Igf2, genomic imprinting

The imprinted, maternally expressed mouse H19 gene is located in proximity to a number of imprinted genes on the distal portion of mouse chromosome 7 (Bartolomei et al. 1991; Caspary et al. 1998). Other genes in the region include the paternally expressed insulin-like growth factor 2 (Igf2) and insulin 2 (Ins2) genes and the maternally expressed p57KIP2, Kvlqt1, and Mash2 genes (DeChiara et al. 1991; Giddings et al. 1994; Guillemot et al. 1995; Hatada and Mukai 1995; Gould and Pfeifer 1998). A conserved cluster of imprinted genes is found on human chromosome 11p15.5 in the Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome critical region (Reid et al. 1997). A second cluster of imprinted genes resides in the Prader-Willi and Angelman syndrome critical regions on human chromosome 15, with the syntenic region located centrally on mouse chromosome 7 (Nicholls et al. 1998). Given the intriguing clustering of imprinted genes, it has been proposed that the imprinting of individual genes is dependent upon their linkage to other imprinted genes (Barlow 1997; Bartolomei and Tilghman 1992, 1997).

The interdependence of imprinted genes has been demonstrated clearly for the mouse H19 and Igf2 genes. The mouse H19 gene is highly expressed, does not encode a protein product, and is located 75 kb from the gene encoding the fetal mitogenic protein IGFII (Zemel et al. 1992). It has been shown that the expression of these two genes is, in part, dependent upon competition for two endodermal-specific enhancers that are located +9 and +11 kb relative to the start of H19 transcription (Yoo-Warren et al. 1988). Deletion of these enhancers on the maternal chromosome results in a loss of H19 expression in endodermal tissues, whereas deletion of the enhancers on the paternal chromosome results in the corresponding loss of Igf2 expression (Leighton et al. 1995b). Additionally, deletion of the H19 structural gene and 10 kb of upstream flanking sequence from the maternal allele leads to expression of the normally repressed Igf2 gene, indicating that the enhancers which initially supported maternally derived H19 expression were free to enhance the expression of Igf2 (Leighton et al. 1995a).

Whereas the imprinted expression of Igf2 is dependent upon linkage to the H19 locus, the imprinting of H19 appears to be autonomous. This idea is supported by H19 transgenic experiments in which constructs harboring 4 kb of upstream flanking sequence, an internally deleted H19 structural gene and the 3′ endodermal enhancers are imprinted similarly to the endogenous gene (Bartolomei et al. 1993; Pfeifer et al. 1996; Elson and Bartolomei 1997). We have proposed that this autonomous regulation is governed by paternal-specific DNA methylation present at the endogenous and transgenic loci (Bartolomei et al. 1993). The 7 kb of paternal-specific methylation observed in somatic tissues and sperm includes 4 kb of upstream flanking sequence and the H19 structural gene (Bartolomei et al. 1993; Brandeis et al. 1993; Ferguson-Smith et al. 1993). The importance of methylation for the repression of the paternal allele of H19 is underscored by experiments in which imprinted gene expression was characterized in mice that were deficient for the DNA methyltransferase gene Dnmt1 (Li et al. 1993). When analyzed prior to their death, Dnmt1 null mice expressed both alleles of H19, suggesting that DNA methylation is at least required to maintain H19 imprinting. To demonstrate that DNA methylation could also serve a causative role in the marking of the parental alleles and the setting of the parental imprint, we assayed DNA methylation of H19 during embryogenesis, with an emphasis on preimplantation development as this is the time when the embryo undergoes a period of generalized demethylation (Monk et al. 1987; Sanford et al. 1987). A 2-kb region located from −2 to −4 kb relative to the start of transcription is methylated exclusively on the paternal allele throughout development, suggesting that this region is crucial to determining the imprinted expression of H19 (Tremblay et al. 1995, 1997). When this region was deleted from the original imprinted H19 transgene, the new transgenes were expressed and hypomethylated regardless of parental origin (Elson and Bartolomei 1997).

To determine the role of the 2-kb differentially methylated domain (DMD) at the endogenous H19 locus, we have generated mice lacking the DMD. When the DMD deletion allele is transmitted to the progeny from the father, the normally repressed paternal H19 allele is activated and the expression of the linked paternal Igf2 gene is reduced coordinately. In contrast, transmission of the mutant H19 allele by the mother results in reduced expression of the H19 gene with a concomitant activation of the maternal Igf2 allele, revealing a novel regulatory role for this region. Whereas these experiments prove that the DMD is necessary for silencing the paternal H19 allele, they also show that the DMD is essential on the maternal chromosome for the exclusive expression of H19 and the silencing of Igf2. We conclude that the DMD is required on both parental alleles for the reciprocal imprinting of H19 and Igf2.

Results

Targeted disruption of the H19 upstream differentially methylated domain

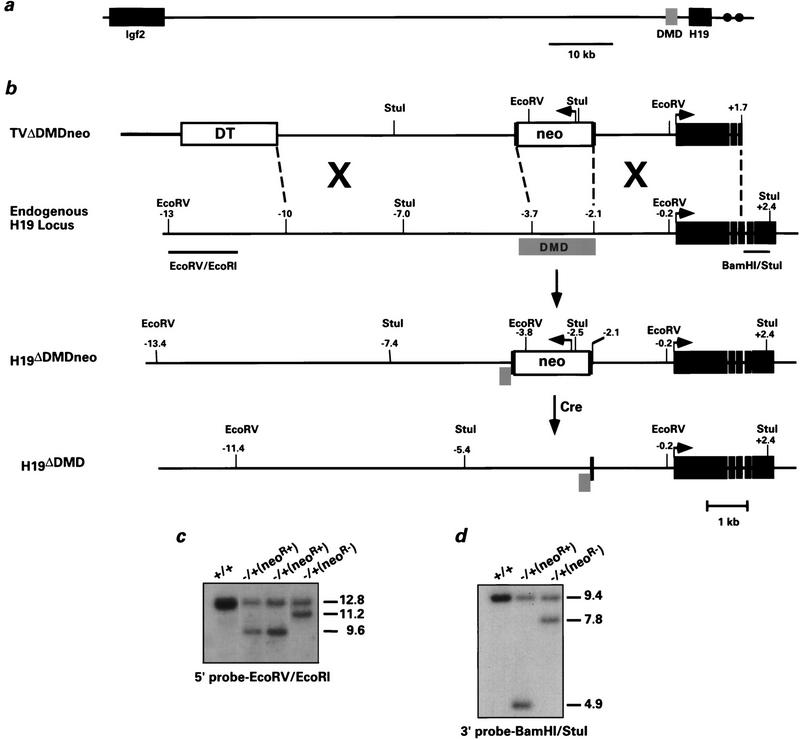

The region from approximately −2 to −4 kb relative to the start of H19 transcription is methylated in sperm, unmethylated in oocytes, and preferentially methylated on the paternal allele throughout development (Tremblay et al. 1995, 1997; Olek and Walter 1997). To test the role of this DMD at the endogenous locus, we deleted most of the DMD by gene targeting in embryonic stem (ES) cells and generated mice with the deletion. As shown in Figure 1b, a targeting vector was constructed in which 1.6 kb of the DMD was replaced by the neomycin resistance (_neo_r) gene flanked by loxP sites. The deletion removes 48 of the CpG dinucleotides that we have proposed to be essential for conferring imprinted expression (Tremblay et al. 1995, 1997). The remaining DMD sequence includes five differentially methylated CpG dinucleotides located 5′ to the targeted deletion.

Figure 1.

Deletion of the H19 differentially methylated domain in ES cells. (a) The positions of Igf2 and H19 relative to the DMD on mouse chromosome 7 are indicated. The gray box corresponds to the 2-kb DMD, which is located −2 to −4 kb relative to the start of H19 transcription. (•) The endodermal enhancers located at +9 and +11 kb. (b) From top to bottom: the linearized targeting vector, the endogenous H19 locus, the targeted H19 locus (H19ΔDMDneo), and the targeted H19 locus after removal of PGK–neo using CRE–loxP recombination (H19ΔDMD). The linearized vector includes Bluescript II KS (thick line), the diphtheria toxin A gene (open box, DT), PGK–neo (open box, neo) flanked by loxP sites (black vertical bars), 5′ H19 sequence (thin black line) and H19 gene sequence extending into the third exon (solid boxes). Arrows indicate direction of transcriptional orientation of PGK–neo and H19. The positions of the restriction sites and the external probes (_Eco_RV/_Eco_RI and _Bam_HI/_Stu_I) used to analyze the targeted clones are indicated. (c,d) ES cell clones were screened by Southern blot analysis for the targeting event. Genomic DNA was digested with _Eco_RV and hybridized to the 5′ probe _Eco_RV/_Eco_RI (c) or with _Stu_I and hybridized to the 3′ probe _Bam_HI/_Stu_I (d). The DNA samples shown include the parental ES cell DNA (+/+), targeted clones with the _neo_r gene (neoR+), and a targeted clone in which the _neo_r gene was excised (neoR−). Molecular sizes (in kb) are indicated to the right. Of the 85 G418-resistant clones analyzed, four were correctly targeted to the H19 locus.

Because the function of a putative imprinting regulatory element was being tested, it was important to eliminate any new regulatory elements introduced by the _neo_r gene cassette. Therefore, following the identification of correctly targeted cells lines, two independent clones were chosen for a second electroporation with a vector encoding Cre recombinase to derive clones that deleted the _neo_r gene (Fig. 1c,d). Cells (with and without the _neo_r gene) were injected into C57BL/6J host blastocysts and mice inheriting the targeted allele were selected for subsequent breeding. The mutant mice were maintained by breeding to C57BL/6J mice. For analysis of allelic imprinting patterns, the heterozygous DMD mutant mice were mated with a strain of mice [B6(CAST–_H19_), (Tremblay et al. 1995)] in which the portion of distal chromosome 7 harboring the imprinted genes of interest was derived from Mus musculus castaneus. Heterozygous and homozygous DMD mutant mice were obtained in the predicted Mendelian ratio and were viable and fertile.

Paternal inheritance of the DMD deletion

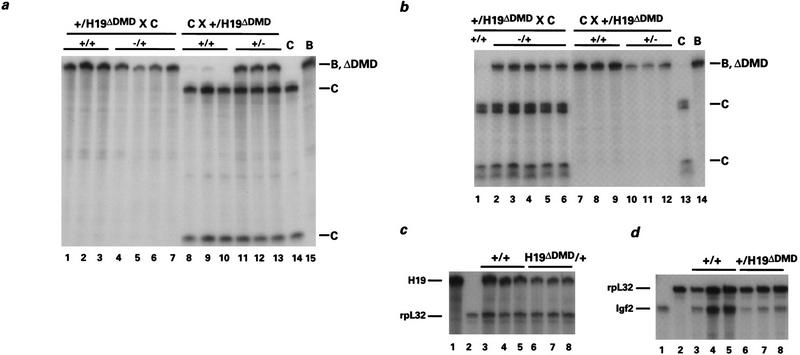

To determine the effect of the DMD deletion on the expression of imprinted genes, mice that inherited the mutant allele (H19ΔDMD) from the father were first tested for H19 expression (Fig. 2a). When the livers from neonatal heterozygous mice were analyzed by RNase protection, the normally silent paternal H19 allele (Fig. 2a, lanes 8–10) was activated to a level of ∼60% of that observed for the maternal wild-type allele, whereas H19 expression from the maternal allele was unaffected (Fig. 2a, lanes 11–13). The analysis of other tissues showed that the level of activation of the mutant paternal H19 allele varied according to tissue type, with gut derivatives exhibiting a moderate level of activation, whereas in muscle derivatives activation was nearly equivalent to that for liver (data not shown). These results indicate that deletion of the DMD eliminated sequences that were repressive to H19 gene expression. The deletion did not, however, completely activate H19 expression to levels observed for the wild-type maternal allele.

Figure 2.

Expression of H19 and Igf2 in H19ΔDMD heterozygous mice. Livers were isolated from neonates generated from reciprocal crosses of B6(CAST–H19) (C) and F1 H19ΔDMD heterozygotes maintained in a C57BL/6 background (B). Three micrograms of total RNA was analyzed using an allele-specific RNase protection assay. The C-, B-, and ΔDMD-specific protected fragments are designated. (a) H19 expression when H19ΔDMD was inherited from the mother (lanes 1–7) or the father (lanes 8–13). When the mother was heterozygous for the mutation, the maternal allele (B, ΔDMD) was expressed in wild-type newborn mice (+/+, lanes 1–3) and expressed at a reduced level in mutant (−/+, lanes 4–7) newborn mice. In 5-day-old littermates generated from paternal heterozygotes, the maternal allele (C) is expressed in wild-type mice (+/+, lanes 8–10), whereas mutant mice express both alleles (+/−, lanes 11–13). The relative ratio of paternally to maternally derived H19 RNA is 0.615, 0.586, and 0.575 (lanes 11–13, respectively). Note that a low level of expression of the paternal allele (<0.5%) was detected in wild-type mice (lanes 8,9) as observed previously (Leighton et al. 1995a). Control liver RNA isolated from 4-day-old B6(CAST–H19) and 5-day-old C57BL/6 mice was analyzed in lanes 14 and 15, respectively. (b) Igf2 expression when the H19ΔDMD allele is maternally (lanes 1–6) or paternally derived (lanes 7–12). Three-day-old mice generated from maternal heterozygotes expressed the paternal allele (C) when wild-type for the mutation (+/+, lane 1) and expressed both alleles when heterozygous for the mutation (−/+, lanes 2–6). The relative ratio of maternally to paternally derived Igf2 RNA is 0.373, 0.315, 0.317, 0.338, and 0.370 (lanes 2–6, respectively). In 5-day-old littermates generated from paternal heterozygotes, the paternal allele is expressed exclusively in wild-type mice (+/+, lanes 7–9) and expressed at a reduced level in mutant mice (+/−, lanes 10–12). Control liver RNAs as described in a are assayed in lanes 13 and 14. (c) The expression of H19 is analyzed relative to the expression of rpL32 when the H19ΔDMD allele is transmitted by the mother. RNA from wild-type (+/+, lanes 3–5) and mutant (H19ΔDMD/+, lanes 6–8) 5-day-old littermates was assayed with H19 and rpL32 probes. The ratio of H19 to rpL32 RNA is as follows: 2.72, 2.85, 1.60, 1.14, 1.34, and 1.04 (lanes 3–8, respectively). Neonatal liver RNA is assayed with the H19 or rpL32 probes alone in lanes 1 and 2, respectively. (d) The expression of Igf2 was analyzed relative to rpL32 when the H19ΔDMD allele was transmitted by the father. RNA from wild-type (+/+, lanes 3–5) and mutant (+/H19ΔDMD, lanes 6–8) newborn littermates is assayed with the Igf2 and rpL32 probes. The ratio of Igf2 to rpL32 RNA is as follows: 0.465, 0.502, 0.536, 0.150, 0.189, and 0.165 (lanes 3–8, respectively). Neonatal liver RNA was assayed with the Igf2 or rpL32 probes alone in lanes 1 and 2, respectively. Total RNA levels for the wild-type and heterozygous mutants were confirmed by Northern analysis (data not shown).

Because transcription of the Igf2 and H19 genes is linked (Leighton et al. 1995a,b), the effect of the DMD deletion on Igf2 expression was examined. Paternal transmission of the mutant H19ΔDMD allele caused repression of the paternally inherited Igf2 gene (Fig. 2b, cf. lanes 10–12 and lanes 7–9). When the level of paternal allele expression in the liver of neonatal heterozygous mice was compared to that of wild-type littermates, a 66% reduction in Igf2 RNA was observed (Fig. 2d). As noted for H19, the reduction in Igf2 expression varied according to tissue (data not shown). Consistent with the decrease in Igf2 expression, the weights of the heterozygous littermates were on average 93% that of their wild-type littermates. Whereas reduction of Igf2 expression in liver is concordant with experiments proving that H19 and Igf2 share enhancers, it is striking that the level of activation of H19 from the mutant paternal allele was equivalent roughly to the reduction of Igf2 expression on the same allele.

Maternal inheritance of the DMD deletion

The effect of maternal transmission of the DMD mutation was also tested for H19 and Igf2 expression. Surprisingly, transmission of the mutant H19ΔDMD allele through the maternal germ line resulted in the reduced expression of the H19 gene (Fig. 2a, cf. lanes 4–7 with lanes 1–3). When quantified by RNase protection, the expression of H19 in neonatal livers was approximately half that observed in wild-type littermates (Fig. 2c). To determine if Igf2 was affected by the maternally derived DMD mutation, allelic Igf2 expression levels were assayed. The normally silent maternal Igf2 allele was activated to about one-third the level of the wild-type paternal allele and expression from the wild-type paternal allele was unaffected (Fig. 2b, lanes 2–6). Additionally, when compared to their wild-type littermates, the mice that inherited the mutant allele maternally were on average 17% larger, which is consistent with activation of maternal Igf2. Thus, a reduction in the level of H19 expression on the mutant maternal allele was accompanied by an activation of the maternally derived Igf2 gene and a slight increase in weight. Because the coordinated expression of H19 and Igf2 was also observed upon paternal transmission of the mutation, these results indicate that deletion of the DMD resulted in a true competition for the endodermal enhancers. These results additionally demonstrate that the DMD has a previously unsuspected positive regulatory function for the exclusive expression of the maternal H19 allele.

Methylation analysis of the targeted H19 alleles

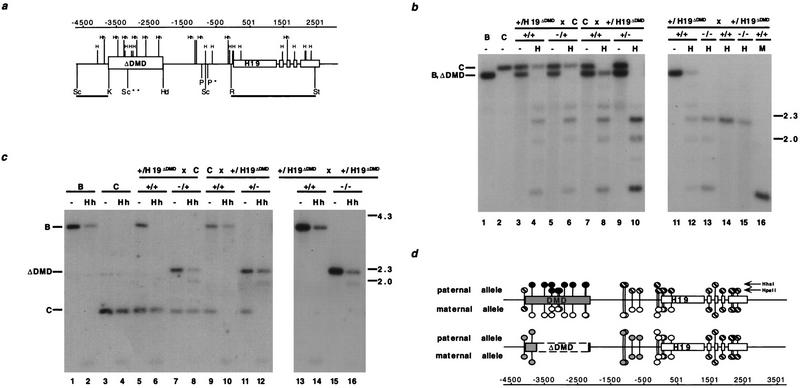

We have proposed that the DMD harbors an imprinting mark in the form of paternal-specific methylation (Tremblay et al. 1995, 1997). Because not all of the differentially methylated sequences at the H19 locus were removed by the DMD deletion, it was of interest to determine the effect of the deletion on the methylation of the remaining CpG dinucleotides. The CpG dinucleotides located in the promoter-proximal region and the 5′ portion of the H19 structural gene are preferentially methylated on the paternal allele late in gestation [see Fig. 3d, sites between −500 and +501 bp (Bartolomei et al. 1993; Brandeis et al. 1993; Ferguson-Smith et al. 1993; Tremblay et al. 1997)]. In contrast, the 3′ portion of the H19 structural gene is equally methylated on both alleles [see Fig. 3d, sites downstream of +501 bp (Ferguson-Smith et al. 1993)], as are sites 5′ of the 2-kb DMD [Fig. 3d, upstream of −4000 bp (Tremblay et al. 1997)]. To determine whether the methylation of the H19 promoter and structural gene was affected by the mutation, neonatal liver DNA from reciprocal heterozygotes was digested with _Pvu_II and _Stu_I and the methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme _Hpa_II and subjected to Southern analysis (Southern 1975). The wild-type M. castaneus allele lacks a _Pvu_II site, which enabled the distinction between the mutant C57BL/6 H19 allele (3.2 kb) and the wild-type M. castaneus H19 allele (3.4 kb) (Bartolomei et al. 1993). When the mutation was transmitted to the progeny by the mother, the methylation of the H19 promoter and structural gene appeared unaffected (Fig. 3b, cf. lanes 4 and 6). In contrast, the deletion of the DMD on the paternally inherited allele resulted in the hypomethylation of the _Hpa_II sites in the promoter region (Fig. 3b, _Pvu_II/_Stu_I fragment in lanes 8 and 10). Similarly, a _Hha_I site in the promoter was not methylated on the mutant paternal allele (data not shown). These results were consistent with methylation analysis in homozygous mutant animals in which the promoter was hypomethylated on both alleles (Fig. 3b, lane 13). Thus, deletion of the DMD from the paternal allele was accompanied by a loss of methylation in the sequences surrounding the promoter, causing the mutant paternal allele to resemble the wild-type maternal allele (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3.

Methylation analysis of H19 in heterozygous and homozygous DMD mutant mice. (a) The location of the _Hpa_II (H) and _Hha_I (Hh) sites with respect to the deleted DMD sequence. The 5′ H19 DMD sequence, deleted between the _Kpn_I (K) and _Hin_dIII (Hd) sites, and H19 are represented by boxed regions. (P) _Pvu_II; (R) _Eco_RI; (St) _Stu_I; (Sc) _Sac_I. (*) The polymorphic _Pvu_II site that is found in C57BL/6J and H19ΔDMD; (**) the polymorphic _M. castaneus Sac_I site. The RSt probe used in b and the ScK probe used in c are indicated beneath the line. The position of the sites, relative to the start of transcription, are indicated (in bp) above the gene line. (b) The methylation status of Hpa_II sites in the H19 Pvu_II/Stu_I fragment is assessed with the RSt probe. DNA from C57BL/6J (B) mice, B6(CAST–_H19) mice (C), progeny of a H19ΔDMD heterozygous female mated to a B6(CAST–_H19) male (lanes 3–6), progeny from a B6(CAST–_H19) female mated to a H19ΔDMD heterozygous male (lanes 7–10) and progeny of a H19ΔDMD heterozygous female mated to a H19ΔDMD heterozygous male (lanes 11–16) were analyzed. DNA was digested with _Pvu_II and _Stu_I and, in lanes indicated, _Hpa_II (H) or _Msp_I (M). The genotypes of the assayed DNA from the specific mating are indicated above the lanes. DNA from neonatal livers (lanes 1–13,16) and adult sperm (lanes 14,15) were assayed. The _M. castaneus_-specific _Pvu_II/_Stu_I fragment (C, 3.4 kb) and the C57BL/6 and _H19ΔDMD_-specific _Pvu_II/_Stu_I fragment (B, ΔDMD, 3.2 kb) are noted at left, with size markers in kb shown at right. (c) DNA from mice described in b was analyzed for _Hha_I methylation in the 5′ _H19 Sac_I fragment using the ScK probe. DNA was digested with _Sac_I and, in lanes indicated, Hha_I (Hh). The genotypes of the DNA samples are indicated above the lanes. The C57BL/6J (3.8 kb), B6(CAST–_H19) (1.5 kb) and the H19ΔDMD (2.2 kb)-specific _Sac_I fragments are indicated at left. (d) Summary of the parental-specific methylation status of _Hpa_II and _Hha_I sites on wild-type (top line) vs. H19ΔDMD (middle line) alleles. The taller and shorter lollipops represent the _Hha_I and the _Hpa_II sites, respectively. (Solid circles) Fully methylated sites; (open circles) unmethylated sites; (striped circles) sites that are methylated on a subset of the alleles, as determined from previous studies (bisulfite sequence and Southern analyses) and data presented herewith; (shaded circles) sites that are partially methylated. The paternal-specific methylation status is presented above each allele; the maternal-specific methylation status is presented below each allele.

Next, we examined the methylation status of upstream CpG dinucleotides that remained on the mutant allele (Fig. 3a, sites between −4500 and −500 bp). The _Hha_I site located immediately 5′ to the deletion and the two _Hha_I sites located between the promoter and the DMD were analyzed using _Sac_I polymorphic fragments (Fig. 3a). In wild-type animals, the sites were hypermethylated on the paternal allele but hypomethylated on the maternal allele (Fig. 3c, lanes 5,6,9,10). However, the mutant H19ΔDMD allele was hypermethylated whether it was maternally or paternally transmitted (Fig. 3c, ΔDMD _Sac_I fragment, lanes 7 and 8 and 11 and 12, respectively). This hypermethylation of the mutant allele was also evident in homozygous mutant animals (Fig. 3c, lanes 15,16). The remaining _Hpa_II sites in this upstream region were also hypermethylated on both mutant alleles (data not shown). Thus, whereas the DMD deletion was associated with the hypomethylation of cytosine residues surrounding the promoter, CpG dinucleotides located upstream from the promoter were partially methylated on the mutant alleles (Fig. 3c and data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that the methylation status of the mutant alleles reflected neither the maternal nor paternal wild-type pattern (Fig. 3d). Rather, the mutant allelic methylation pattern was intermediate between the two wild-type parental alleles and no longer parental-specific.

We also compared the methylation status of sperm DNA isolated from wild-type and homozygous mutant adult males generated from F1 heterozygous intercrosses. The methylation state of the H19 promoter, structural gene, and remaining 5′ sequence was unchanged with the removal of the DMD sequence. Specifically, the wild-type and ΔDMD sperm DNA were similarly unmethylated in the H19 promoter region (Fig. 3b, lanes 14 and 15) and were similarly methylated at _Hha_I sites immediately 5′ and 3′ of the deleted sequence (data not shown). These data indicate that removal of DMD sequence did not perturb the acquisition of the sperm-specific methylation pattern in the remaining H19 sequence.

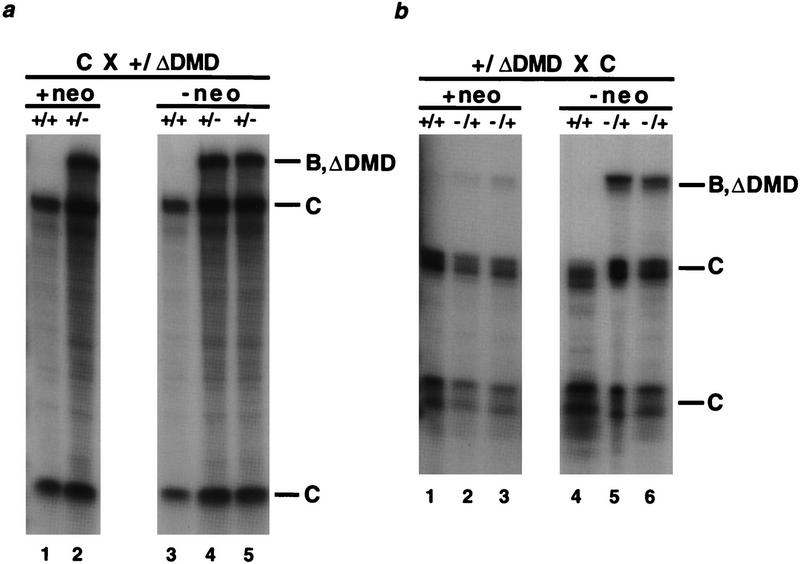

Analysis of H19ΔDMDneo alleles

The experiments described above used mice in which the _neo_r gene was excised. To determine if the perturbation of imprinted gene expression was caused solely by the absence of the DMD or if the spacing change imposed by the deletion was responsible for altered gene-expression patterns, mice in which the _neo_r gene remained at the H19 locus were examined. Because the size of the _neo_r gene was similar to that of the deleted DMD fragment, inclusion of the _neo_r gene preserved spacing of the H19 upstream elements. As observed for the H19ΔDMD alleles, both the H19 and Igf2 genes were expressed on the maternal and paternal H19ΔDMDneo alleles in neonatal liver (Fig. 4). The _neo_r gene did not affect H19 expression levels on either parental allele (Fig. 4a, data not shown), supporting the proposed role of the DMD as both a positive and negative regulator of H19 gene expression. However, the presence of the _neo_r gene caused a less dramatic increase in the expression of Igf2 on the mutant maternal allele (Fig. 4b, lanes 2,3). That is, in the presence of the _neo_r gene, Igf2 was activated to ∼6% that of the wild-type paternal allele, whereas in the absence of the _neo_r gene, Igf2 expression on the mutant maternal allele increased to an average of one-third the level of the wild-type paternal allele (Fig. 4b, lanes 1–3 and 4–6, respectively). These results suggest that the _neo_r gene interfered with the activation of Igf2 on the mutant maternal allele and are consistent with studies of regulatory elements at other loci demonstrating that the _neo_r gene regulatory elements affected gene expression (Fiering et al. 1995).

Figure 4.

Expression of H19 and Igf2 in H19ΔDMD and H19ΔDMDneo mice. The genotypes are noted above the lanes and the parental identity of protected fragments are indicated to the right. Neonatal liver RNA (3 μg) is analyzed using allele-specific RNase protection assays. (a) H19 expression in paternal heterozygotes. The RNA isolated from a wild-type and a mutant littermate, generated from mating a B6(CAST–H19) female with a heterozygous H19ΔDMDneo male, is assayed in lanes 1 and 2, respectively. The RNA isolated from the progeny of a mating between a B6(CAST–H19) female and a heterozygous H19ΔDMD male is assayed in lanes 3–5. (b) Igf2 expression in maternal heterozygotes. RNA from wild-type and mutant +neo littermates (lanes 1 and 2 and 3, respectively) and wild-type and mutant −neo littermates (lanes 4 and 5 and 6, respectively) produced from the reciprocal mating performed in a is assayed.

The imprinting of the _neo_r gene was also assessed in RNA isolated from livers of heterozygous and homozygous H19ΔDMDneo neonatal mice. Northern blot analysis showed that the _neo_r expression levels were similar in the maternal and paternal H19ΔDMDneo heterozygous mutants and twofold higher in the homozygous mutants (data not shown), demonstrating _neo_r expression was not imprinted. Thus, in contrast to previous experiments in which the _neo_r gene was used to replace the H19 transcription unit and was imprinted (Ripoche et al. 1997), the sequences remaining at the H19ΔDMD locus were not sufficient to imprint the _neo_r gene.

Discussion

We proposed previously that paternal-specific DNA methylation in the region located from −2 to −4 kb relative to the start of H19 transcription is involved in the imprinting of the mouse H19 gene (Tremblay et al. 1997). Absence of this region in a normally imprinted mouse transgene results in parental-independent expression and hypomethylation of the derivative transgene (Elson and Bartolomei 1997), indicating that the DMD is crucial for suppression of a paternally transmitted transgene. This element also has unique properties in Drosophila where it acts as a silencer, despite the absence of DNA methylation in the Drosophila genome (Lyko et al. 1997).

To test the role of the DMD at the endogenous H19 gene locus, we have deleted most of this region using gene-targeting technology. Paternal transmission of the mutant allele resulted in activation of H19 expression, a concomitant reduction in Igf2 expression, and a reduction in methylation of the remaining CpG dinucleotides at the H19 locus (Fig. 5). These results are consistent with the transgenic experiments and support the hypothesis that the DMD represses transcription of the paternally derived H19 allele. The negative regulatory role of the paternally derived DMD is likely caused by its hypermethylation that could either act directly by preventing the binding of factors that establish a transcriptionally competent state or could act indirectly through the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2, or other unknown proteins with analogous activities, which subsequently recruits histone deacetylases and represses transcription (Jones et al. 1998b; Nan et al. 1998).

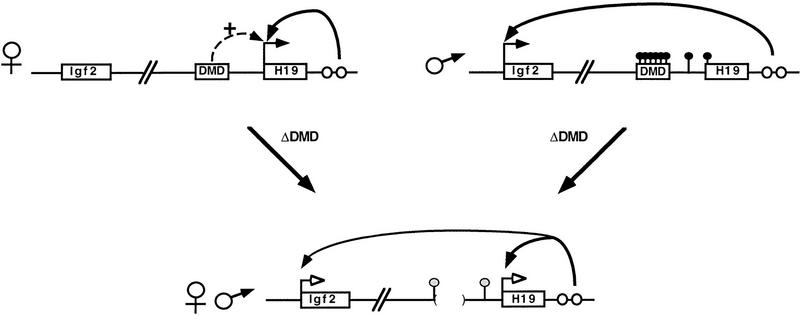

Figure 5.

A model for DMD-regulated H19 and Igf2 imprinting based on the analysis of neonatal liver. The maternal and paternal wild-type alleles are represented with parental-specific gene expression (horizontal arrows) and H19 paternal-specific methylation (filled-in circles above the locus). The H19 and Igf2 genes and the DMD are depicted as boxes and endodermal enhancers as open circles. The deletion of the DMD (bordered by parentheses) on the maternal or the paternal allele results in expression of both genes as depicted at bottom. In addition, 5′ H19 sequence is similarly methylated on both alleles (shaded circles above 5′ H19 sequence). The model illustrates the following properties of the DMD. (1) The DMD positively affects maternal H19 expression (broken arrow); when it is deleted, maternal H19 expression is reduced (open arrowheads). (2) The DMD contributes to silencing of the paternal H19 allele. (3) Presence of the DMD is required for reciprocal imprinting of Igf2. In ΔDMD mice, reduced H19 expression on the maternal allele is accompanied by activated Igf2 expression, and activated H19 expression from the paternal allele is accompanied by reduced Igf2 expression, consistent with previous proposals that the endodermal enhancers are shared. (4) Paternal-specific methylation is maintained in the presence of DMD. (5) The DMD serves as the mark that distinguishes the parental alleles of H19.

A new finding of this study was the observed decrease in H19 expression together with the concomitant activation of Igf2 upon maternal transmission of the mutant allele, suggesting that the DMD also influences transcription of H19 on the maternal allele positively (Fig. 5). Indeed, chromatin studies of the H19 locus have shown that the DMD is hypersensitive to nucleases exclusively on the maternal chromosome, supporting the concept of a novel maternally derived positive role for this element (Hark and Tilghman 1998). A number of mechanisms could lead to this positive regulatory function. First, the unmethylated DMD might bind transcription factors that promote the expression of H19. In the case of the mutant maternal allele, the decreased expression of H19 may be caused by the loss of positive transcriptional elements rendering H19 less effective in utilizing the endoderm-specific enhancers. These enhancers are then free to drive the expression of Igf2. Thus, although the DMD is not required for transgenic H19 expression (Pfeifer et al. 1996; Elson and Bartolomei 1997), possibly because of the absence of the competing Igf2 gene, it appears to be essential for the optimal and exclusive expression of H19 at the endogenous locus. Second, the maternally derived DMD may form a unique chromatin configuration that promotes transcriptional activity. Third, the DMD could act as a selector that directs transcription either toward H19 or Igf2. Fourth, the DMD may function to repress Igf2 transcription on the maternal allele, thereby indirectly affecting H19 expression. Thus, in the absence of the DMD on the maternal allele, Igf2 expression is derepressed, which reduces access of the enhancers to H19. Finally, Tilghman and colleagues have suggested that the DMD acts as a domain boundary or a chromatin insulator which isolates the H19 promoter and endodermal enhancers and blocks the Igf2 gene from accessing these enhancers on the maternal chromosome (Webber et al. 1998). Originally identified in Drosophila, boundary elements insulate a gene and its regulatory elements from position effect variegation and can block gene expression when placed between a gene and its enhancers (Kellum and Schedl 1991, 1992). The proposal that the DMD functions as a domain boundary in mouse is supported by experiments in which Igf2 is preferentially expressed on maternally derived chromosomes in which the H19 endoderm enhancers were removed from their normal location and placed between the H19 and Igf2 genes and upstream of the DMD (Webber et al. 1998). Although these latter experiments could be explained by distance effects or the placement of the enhancers in a new chromatin environment, taken together, the gene-targeting experiments would argue in favor of the DMD acting as a domain boundary. Formal proof of this model will require the demonstration that the DMD insulates gene expression at a heterologous locus.

The experiments described in this report support the original model proposing that the reciprocal imprinting of the H19 and Igf2 genes is mediated by a competition for the shared set of endoderm enhancers [Fig. 5 (Bartolomei and Tilghman 1992)]. Mice harboring the DMD deletion express H19 and Igf2 from the mutant chromosome, with enhanced expression of one gene accompanied by a coordinate decrease in the expression of the other gene. The canonical example for this type of regulation is the promoter competition in the chicken β-globin gene complex, where the switch from the embryonic ε-globin to the adult β-globin is achieved through a competition for the β-globin enhancer (Choi and Engel 1988; Foley and Engel 1992). Similar to the compensatory expression changes observed in our mutant mice, mutations that attenuated adult β-globin expression were accompanied by an increase in the expression of ε-globin (Foley and Engel 1992). Recent experiments by Jones and colleagues indicate that the competition by H19 and Igf2 promoters for the endoderm enhancers may not be mediated strictly by the promoters and DMD alone (Jones et al. 1998a). In experiments in which the H19 transcriptional unit was replaced with the luciferase gene, luciferase was expressed at variable levels on the paternal allele, whereas the expression and imprinting of Igf2 was maintained at wild-type levels. One interpretation of these experiments is that the RNA-coding portion of the H19 gene is also required for linked competition of these genes.

Our study does not address the mechanism by which H19 and Igf2 share enhancer elements at the cellular level. For example, in the paternal mutant heterozygote, H19 and Igf2 may be expressed simultaneously from the mutant allele. Alternatively, each cell makes a choice: some cells may exclusively express Igf2 from the mutant paternal allele and other cells may exclusively express H19. It is also possible that each cell expresses both genes from the mutant paternal allele but only one gene is expressed at a given time. The latter is analogous to the flip-flop model of gene regulation that has been proposed to explain how distal control elements allow the simultaneous expression of γ- and β-globin in early development (Wijgerde et al. 1995). Future studies of our mutants at the cellular level will discriminate between these possibilities.

Finally, we have determined that deletion of the DMD on one chromosome does not appear to affect the expression or methylation of the genes on the wild-type chromosome. Unlike experiments showing that Igf2 transgenes can transactivate the endogenous Igf2 gene and lead to Beckwith-Wiedemann-related symptoms (Sun et al. 1997), the activation of either H19 or Igf2 on the mutant chromosome does not affect the expression of their counterparts on the wild-type chromosome. Furthermore, after three generations of breeding the mutant mice, the only observed phenotypes in animals with alterations in H19 and Igf2 expression are subtle size effects that are consistent with the changes in Igf2 expression. No phenotypic consequences reminiscent of Beckwith-Wiedemann have been noted. Additionally, homozygous mutant animals have no apparent phenotype, possibly because the total expression of H19 and Igf2 in the neonatal livers of homozygous animals is similar to that of wild-type animals (data not shown).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the DMD has multiple roles in regulating the imprinting of the H19 gene. Our hypothesis that the differential methylation serves as the allelic mark is strengthened by the observation that deletion of the DMD on both chromosomes renders them indistinguishable by the criteria employed in these studies. As expected, the DMD mediates a repressive effect on the transcription of the paternally derived chromosome, presumably through its hypermethylation. Additionally, we have shown that the DMD permits the exclusive expression of H19 on the maternal chromosome, possibly through the binding of positive regulatory factors, a unique chromatin configuration, inhibition of Igf2, or through the assembly of a domain boundary which prevents access of Igf2 to the enhancers. Future studies will elucidate the factors responsible for the multiple roles of this complex element.

Materials and methods

Preparation of the targeting vector

A phage clone containing 13.5 kb of 5′ flanking and 1.8 kb of H19 gene sequence was isolated from a 129Sv/J mouse genomic library in the Lambda FIX II vector (Stratagene). The phage insert was subcloned as two fragments into Bluescript II KS (Stratagene); a _Not_I/_Kpn_I fragment corresponding to 9.8 kb of 5′ flanking H19 sequence (p9.8N/K) and a _Kpn_I/_Not_I fragment containing the remaining 5′ flanking and H19 gene sequence (p5.5K/N). The _Kpn_I site is −3.7 kb relative to the start of H19 transcription and is the 5′ boundary of the DMD-targeting event. To initiate construction of the targeting vector, an _Eco_RI/Xho_I fragment containing a 2-kb PGK–_neo loxP flanked cassette was subcloned into Bluescript II KS and the _Xho_I site was eliminated subsequently (ploxPneo–BS). p5.5K/N was then digested with _Hin_dIII, blunted with Klenow, and digested with _Not_I to generate the 3.9-kb _Hin_dIII/_Not_I H19 fragment that serves as the 3′ arm of the targeting vector. This fragment was subcloned into _Not_I/_Sma_I-digested ploxPneo–BS to generate pneo3′H19. To assemble the target vector the following were simultaneously ligated: a 6.6-kb _Bam_HI/_Kpn_I 5′ H19 fragment (from p9.8N/K), a 5.9-kb _Kpn_I/Not_I fragment including loxP–_neo cassette and 3.9-kb H19 sequence (from pneo3′H19), and _Not_I/_Bam_HI digested Bluescript II KS. Finally, a 2.3-kb _Sal_I fragment containing a diphtheria toxin A cassette (McCarrick et al. 1993) was ligated to the _Xho_I linearized target vector. The final targeting vector contains a total of 10.1 kb of homology to the H19 locus (Fig. 1b).

Targeted disruption of the DMD region in ES cells

The vector was linearized at a unique _Not_I site prior to electroporation into ES cells. E14.1 ES cells (Kuhn et al. 1991) were grown on neomycin-resistant mouse embryonic fibroblasts. ES cells (1.5 × 107/ml) were collected in 0.8 ml of phosphate-buffered saline and electroporated with a pulse of 250 V/500 mF (Gene Pulser, Bio-Rad) with 25 μg of linearized targeting vector. Following a 24-hr recovery, the medium was adjusted to 200 μg/ml G418. After 8–10 days growth, G418-resistant colonies were isolated and expanded, and DNA was prepared. The DNA was digested with _Eco_RV (5′-end confirmation) or _Stu_I (3′-end confirmation) and size fractionated on 0.75% and 1.0% agarose gels, respectively. DNA was transferred to nitrocellulose (Southern 1975) and hybridized to nick-translated external probes (Rigby et al. 1977). The _Eco_RV/_Eco_RI probe was used for 5′-end confirmation and the _Bam_HI/_Stu_I probe was used for 3′-end confirmation (Fig. 1b).

The _neo_r cassette was removed by transiently transfecting two independent ΔDMDneo ES cell lines with 25 μg of a plasmid encoding the Cre recombinase (Sauer and Henderson 1990). Correctly excised clones were verified by digestion with _Stu_I or _Eco_RV, as described above, and by a 350-bp PCR product that was amplified using primers that flank the ΔDMD mutation. The forward primer was 5′-ATCCAGGAGGCATCCGAATT-3′ and the reverse primer was 5′-GTGTCACAAATGCCTGATCC-3′.

Cells from targeted ES cell clones (with and without the neo_r gene) were injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts, and the blastocysts were transferred to pseudopregnant female mice. To determine if germ-line transmission of the mutant allele had occurred, chimeras were bred with C57BL/6J mice, and DNA was isolated from tail biopsies of progeny. The Southern blot and PCR analyses described above were used to genotype the mice. To analyze allelic expression and methylation patterns, the heterozygous mutant mice were bred to the B6(CAST–_H19) strain of mice (Tremblay et al. 1995). These mice have M. castaneus H19 and Igf2 alleles on a C57BL/6 background. For F1 hybrid mice, the maternal parent is designated first.

RNA isolation and analysis

Total RNA was prepared from various staged mouse tissues by the lithium chloride method (Auffray and Rougeon 1980). The RNase protection assays that were used to detect H19 (Bartolomei et al. 1991; Brunkow and Tilghman 1991), Igf2 (Leighton et al. 1995a), and rpL32 (Dudov and Perry 1984) gene expression were performed as described previously. Products were resolved on a 7.0% acrylamide/7 m urea gel.

For quantitation, RNase protection gels were exposed to storage phosphor screens that were scanned on a Storm 840 PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Band intensities were calculated using ImageQuant Version 1.0 (Molecular Dynamics). After pseudocolor enhancement of the image, bands of interest were traced using the freehand drawing tool. The median pixel values of individual segment boundaries were used as the background values. In all cases, RNase protection assays of the deletion allele produce one protected fragment, whereas assays of the wild-type M. castaneus allele produce two protected fragments. In samples in which biallelic expression was observed, the value of the mutant protected fragment was quantified relative to the two fragments corresponding to the wild-type B6(CAST–H19) allele. The levels of H19 RNA in ΔDMD maternal heterozygotes and Igf2 RNA in ΔDMD paternal heterozygotes were quantified relative to wild-type levels using rpL32 as an internal control.

DNA isolation and methylation analysis

DNA was isolated from tissues and sperm as described previously (Bartolomei et al. 1993). Genomic DNA (10 μg) was digested with _Pvu_II and _Stu_I in combination with _Hpa_II or _Msp_I to analyze the methylation of the H19 structural gene or with _Sac_I and _Hha_I to analyze the methylation of upstream sequences. The probes used for the respective analyses were the 2.5-kb _Eco_RI–_Stu_I (RSt) fragment and the 0.9-kb _Sac_I–_Kpn_I (ScK) 5′ fragment (Fig. 3a).

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Richa and the University of Pennsylvania Transgenic Core Facility for the production of chimeric mice. We thank M. Malim, S. Liebhaber, A. Webber, K. Tremblay, and members of the lab for critical reviews of the manuscript. We are grateful to A. Hark and S.M. Tilghman for communication of results prior to publication. This work was supported by U.S. Public Service grant GM51279 and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. J.L.T. was supported by National Research Service Award postdoctoral fellowship GM18458.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ‘advertisement’ in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL bartolom@mail.med.upenn.edu; FAX (215) 573-6434.

References

- Auffray C, Rougeon F. Purification of mouse immunoglobulin heavy-chain messenger RNAs from total myeloma tumor RNA. Eur J Biochem. 1980;107:303–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb06030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DP. Competition—a common motif for the imprinting mechanism. EMBO J. 1997;16:6899–6905. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomei MS, Tilghman SM. Parental imprinting of mouse chromosome 7. Semin Dev Biol. 1992;3:107–117. [Google Scholar]

- ————— Genomic imprinting in mammals. Annu Rev Genet. 1997;31:493–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.31.1.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomei MS, Zemel S, Tilghman SM. Parental imprinting of the mouse H19 gene. Nature. 1991;351:153–155. doi: 10.1038/351153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomei MS, Webber AL, Brunkow ME, Tilghman SM. Epigenetic mechanisms underlying the imprinting of the mouse H19 gene. Genes & Dev. 1993;7:1663–1673. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.9.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandeis M, Kafri T, Ariel M, Chaillet JR, McCarrey J, Razin A, Cedar H. The ontogeny of allele-specific methylation associated with imprinted genes in the mouse. EMBO J. 1993;12:3669–3677. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunkow ME, Tilghman SM. Ectopic expression of the H19 gene in mice causes prenatal lethality. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:1092–1101. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.6.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspary T, Cleary MA, Baker CC, Guan X-J, Tilghman SM. Multiple mechanisms regulate imprinting of the mouse distal chromosome 7 gene cluster. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3466–3474. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi O-RB, Engel JD. Developmental regulation of β-globin switching. Cell. 1988;55:17–26. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeChiara TM, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Parental imprinting of the mouse insulin-like growth factor II gene. Cell. 1991;64:849–859. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90513-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudov KP, Perry RP. The gene encoding the mouse ribosomal protein L32 contains a uniquely expressed intron containing gene and an unmutated processed gene. Cell. 1984;37:457–468. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elson DA, Bartolomei MS. A 5′ differentially methylated sequence and the 3′ flanking region are necessary for H19 transgene imprinting. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:309–317. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson-Smith AS, Sasaki H, Cattanach BM, Surani MA. Parental-origin-specific epigenetic modification of the mouse H19 gene. Nature. 1993;362:751–754. doi: 10.1038/362751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiering S, Epner S, Robinson K, Zhuang Y, Telling A, Hu M, Martin DI, Enver T, Ley TJ, Groudine M. Targeted deletion of 5′HS2 of the murine β-globin LCR reveals that it is not essential for the proper regulation of the beta-globin locus. Genes & Dev. 1995;15:2203–2213. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley KP, Engel JD. Individual stage selector element mutations lead to reciprocal changes in β- vs. ε-globin gene transcription: Genetic confirmation of promoter competition during globin gene switching. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:730–744. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.5.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giddings SJ, King CD, Harman KW, Flood JF, Carnaghi LR. Allele specific inactivation of insulin 1 and 2 in the mouse yolk sac indicates imprinting. Nat Genet. 1994;6:310–313. doi: 10.1038/ng0394-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould TD, Pfeifer K. Imprinting of mouse Kvlqt1 is developmentally regulated. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:483–487. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemot F, Caspary T, Tilghman SM, Copeland NG, Gilbery D J, Jenkins N A, Anderson DJ, Joyner AL, Rossant J, Nagy A. Genomic imprinting of Mash-2, a mouse gene required for trophoblast development. Nat Genet. 1995;9:235–241. doi: 10.1038/ng0395-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hark, A.T. and S.M. Tilghman. 1998. Chromatin conformation of the H19 epigenetic mark. Hum. Mol. Genet. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hatada I, Mukai T. Genomic imprinting of p57/KIP2, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, in mouse. Nat Genet. 1995;11:204–206. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BK, Levorse JM, Tilghman SM. Igf2 imprinting does not require its own DNA methylation or H19 RNA. Genes & Dev. 1998a;12:2200–2207. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PL, Veenstra GJC, Wade PA, Vermaak D, Kass SU, Landsberger N, Strouboulis J, Wolffe AP. Methylated DNA and MeCP2 recruit histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nat Genet. 1998b;19:187–191. doi: 10.1038/561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellum R, Schedl P. A position-effect assay for boundaries of higher order chromatin domains. Cell. 1991;64:941–950. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90318-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— A group of scs elements function as domain boundaries in an enhancer-blocking assay. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2424–2431. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn R, Rajewsky K, Muller W. Generation and analysis of interleukin-4 deficient mice. Science. 1991;254:707–710. doi: 10.1126/science.1948049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton PA, Ingram RS, Eggenschwiler J, Efstratiadis A, Tilghman SM. Disruption of imprinting caused by deletion of the H19 gene region in mice. Nature. 1995a;375:34–39. doi: 10.1038/375034a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton PA, Saam JR, Ingram RS, Stewart CL, Tilghman SM. An enhancer deletion affects both H19 and Igf2 expression. Genes & Dev. 1995b;9:2079–2089. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.17.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li E, Beard C, Jaenisch R. Role for DNA methylation in genomic imprinting. Nature. 1993;366:362–365. doi: 10.1038/366362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyko F, Brenton JD, Surani MA, Paro R. An imprinting element from the mouse H19 locus functions as a silencer in Drosophila. Nat Genet. 1997;16:171–173. doi: 10.1038/ng0697-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarrick JWI, Parnes JR, Seong RH, Solter D, Knowles BB. Positive-negative selection gene targeting with the diphtheria toxin A-chain gene in mouse embryonic stem cells. Transgen Res. 1993;2:183–190. doi: 10.1007/BF01977348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk M, Boubelik M, Lehnert S. Temporal and regional changes in DNA methylation in the embryonic, extraembryonic and germ cell lineages during mouse embryo development. Development. 1987;99:371–382. doi: 10.1242/dev.99.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan X, Ng H-H, Johnson CA, Laherty CD, Turner BM, Eisenman RN, Bird A. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature. 1998;393:386–389. doi: 10.1038/30764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls RD, Saitoh S, Horsthemke B. Imprinting in Prader-Willi and Angelman Syndromes. Trends Genet. 1998;14:194–200. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01432-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olek A, Walter J. The pre-implantation ontogeny of the H19 methylation imprint. Nat Genet. 1997;17:275–276. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer K, Leighton P, Tilghman SM. The structural gene of H19 is required for transgene imprinting. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:13876–13883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid LH, Davies C, Cooper PR, Crider-Miller SJ, Sait SN J, Nowak NJ, Evans F, Stanbridge EJ, deJong P, Shows TB, Weissman BE, Higgins MJ. A 1-mb physical map and PAC contig of the imprinted domain in 11p15.5 that contains TAPA1 and the BWSCR1/WT2 region. Genomics. 1997;43:366–375. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby PWJ, Dieckmann M, Rhodes D, Berg P. Labeling deoxyribonucleic acid to high specific activity in vitro by nick translation with DNA polymerase I. J Mol Biol. 1977;113:237–251. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripoche M-A, Chantal K, Poirier F, Dandolo L. Deletion of the H19 transcription unit reveals the existence of a putative imprinting control element. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:1596–1604. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.12.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford JP, Clark HJ, Chapman VM, Rossant J. Differences in DNA methylation during oogenesis and spermatogenesis and their persistance during early embryogenesis in the mouse. Genes & Dev. 1987;1:1039–1046. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.10.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer B, Henderson N. Targeted insertion of exogenous DNA into the eukaryotic genome by the cre recombinase. New Biol. 1990;2:441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern EM. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F-L, Dean WL, Kelsey G, Allen ND, Reik W. Transactivation of Igf2 in a mouse model of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Nature. 1997;389:809–815. doi: 10.1038/39797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay KD, Duran KL, Bartolomei MS. A 5′ 2-kilobase-pair region of the imprinted mouse H19 gene exhibits exclusive paternal methylation throughout development. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4322–4329. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay KD, Saam JR, Ingram RS, Tilghman SM, Bartolomei MS. A paternal-specific methylation imprint marks the alleles of the mouse H19 gene. Nat Genet. 1995;9:407–413. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber AL, Ingram RS, Levorse JM, Tilghman SM. Location of enhancers is essential for the imprinting of H19 and Igf2 genes. Nature. 1998;391:711–715. doi: 10.1038/35655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijgerde M, Grosveld F, Fraser P. Transcription complex stability and chromatin dynamics in vivo. Nature. 1995;377:209–213. doi: 10.1038/377209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo-Warren H, Pachnis V, Ingram RS, Tilghman SM. Two regulatory domains flank the mouse H19 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:4707–4715. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.11.4707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemel S, Bartolomei MS, Tilghman SM. Physical linkage of two mammalian imprinted genes. Nat Genet. 1992;2:61–65. doi: 10.1038/ng0992-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]