Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology (original) (raw)

Practice Essentials

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an idiopathic disease caused by a dysregulated immune response to host intestinal microflora. The two major types of inflammatory bowel disease are ulcerative colitis (UC), which is limited to the colonic mucosa, and Crohn disease (CD), which can affect any segment of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus, involves "skip lesions," and is transmural. There is a genetic predisposition for IBD, and patients with this condition are more prone to the development of malignancy. See the image below.

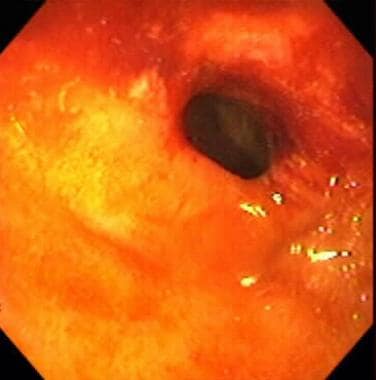

Inflammatory bowel disease. Severe colitis noted during colonoscopy in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease. The mucosa is grossly denuded, with active bleeding noted. The patient had her colon resected very shortly after this view was obtained.

Signs and symptoms

Generally, the manifestations of IBD depend on the area of the intestinal tract involved. The symptoms, however, are not specific for this disease. They are as follows:

- Abdominal cramping

- Irregular bowel habits, passage of mucus without blood or pus

- Weight loss

- Fever, sweats

- Malaise, fatigue

- Arthralgias

- Growth retardation and delayed or failed sexual maturation in children

- Extraintestinal manifestations (10%-20%): Arthritis, uveitis, or liver disease

- Grossly bloody stools, occasionally with tenesmus: Typical of UC, less common in CD

- Perianal disease (eg, fistulas, abscesses): Fifty percent of patients with CD

The World Gastroenterology Organization indicates the following symptoms may be associated with inflammatory damage of the digestive tract [1] :

- Diarrhea: Possible presence of mucus/blood in stool; occurs at night; incontinence

- Constipation: May be the primary symptom in UC limited to the rectum; obstipation may occur; may proceed to bowel obstruction

- Bowel movement abnormalities: Possible presence of pain or rectal bleeding, severe urgency, tenesmus

- Abdominal cramping and pain: Commonly present in the right lower quadrant in CD; occur in the periumbilical or in the left lower quadrant in moderate to severe UC

- Nausea and vomiting: More often in CD than in UC

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Examination in patients with IBD may include the following findings, which are directly related to the severity of the attack:

- Fever

- Tachycardia

- Dehydration

- Toxicity

- Pallor, anemia

- Toxic megacolon: Medical emergency; patients appear septic, have high fever, lethargy, chills, and tachycardia, as well as have increasing abdominal pain, tenderness, distention

- Mass in the right lower abdominal quadrant: May be present in CD

- Perianal complications: May be observed in up to 90% of cases of CD [2]

Testing

Although several laboratory studies may aid in the management of IBD and provide supporting information, no laboratory test is specific enough to adequately and definitively establish the diagnosis, including the following:

- Complete blood count

- Nutritional evaluation: Vitamin B12 evaluation, iron studies, red blood cell folate, nutritional markers

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels

- Fecal calprotectin level

- Serologic studies: Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA)

- Stool studies: Stool culture, ova and parasite studies, bacterial pathogens culture, and evaluation for Clostridium difficile infection [3]

Imaging studies

The following imaging studies may be used to assess patients with IBD:

- Upright chest and abdominal radiography

- Barium double-contrast enema radiographic studies

- Abdominal ultrasonography

- Abdominal/pelvic computed tomography scanning/magnetic resonance imaging

- Computed tomography enterography

- Colonoscopy, with biopsies of tissue/lesions

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy

- Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

- Capsule enteroscopy/double balloon enteroscopy

See Workup for more detail.

Management

The medical approach for patients with IBD is symptomatic care (ie, relief of symptoms) and mucosal healing for mild disease (eg, erythema without ulceration) following a stepwise approach to medication, with escalation of the medical regimen until a response is achieved (“step-up” or “stepwise” approach) for mild disease (eg, erythema without ulceration), such as the following:

- Step I – Aminosalicylates (oral, enema, suppository formulations): For treating flares and maintaining remission; more effective in UC than in CD

- Step IA – Antibiotics: Used sparingly in UC (limited efficacy, increased risk for antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis); in CD, most commonly used for perianal disease, fistulas, intra-abdominal inflammatory masses

- Step II – Corticosteroids (intravenous, oral, topical, rectal): For acute disease flares only

- Step III – Immunomodulators and biologics: Effective for steroid-sparing action in refractory disease; primary treatment for fistulas and maintenance of remission in patients intolerant of or not responsive to aminosalicylates

- Step IV – Clinical trial agents: Tend to be disease-specific (ie, an agent works for CD but not for UC, or vice versa)

Moderate to severe disease warrants more aggressive initial treatment (eg, immunomodulators or biologic agents) in order to prevent complications of the disease.

Pharmacotherapy

The following medications may be used in patients with IBD:

- 5-Aminosalicylic acid derivatives (eg, sulfasalazine, mesalamine, balsalazide, olsalazine)

- Antibiotics (eg, metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, rifaximin)

- Corticosteroid agents (eg, hydrocortisone, prednisone, methylprednisolone, prednisolone, budesonide, dexamethasone)

- Immunosuppressant agents (eg, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate, cyclosporine, tofacitinib)

- Biologic agents, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors (eg, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol); anti-integrin antibodies (eg, natalizumab); inhibitors of IL-12 and IL-23 (eg, ustekinumab)

- H2-receptor antagonists (eg, cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine, nizatidine)

- Proton pump inhibitors (eg, omeprazole, lansoprazole, esomeprazole magnesium, rabeprazole sodium, pantoprazole)

- Antidiarrheal agents (eg, diphenoxylate and atropine, loperamide, cholestyramine)

- Anticholinergic antispasmodic agents (eg, dicyclomine, hyoscyamine)

Surgery

UC is surgically curable. However, surgical resection is not curative in CD, with recurrence being the norm. Consider early consultation with a surgeon in the setting of severe colitis or bowel obstruction and in cases of suspected toxic megacolon.

Surgical intervention in IBD includes the following:

- UC: Proctocolectomy with ileostomy, total proctocolectomy with ileoanal anastomosis

- Fulminant colitis: Surgical procedure of choice is subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy and creation of a Hartmann pouch

- CD: Surgery (not curative) most commonly performed in patients with complications of the disease; generally consists of conservative resection (eg, potential stricturoplasty vs resective surgery) to preserve bowel length in case future additional surgery is needed [4]

- Selected patients with distal ileal or proximal colonic disease: Option for ileorectal or ileocolonic anastomosis

- Severe perianal fistulas: Option for diverting ileostomy; generally, resection for symptomatic enteroenteric fistulas

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an idiopathic disease caused by a dysregulated immune response to host intestinal microflora. The two major types of IBD are ulcerative colitis (UC), which is limited to the colon, and Crohn disease (CD), which can involve any segment of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract from the mouth to the anus, involves "skip lesions," and is transmural (see the images below). There is a genetic predisposition for IBD (see Etiology), and patients with this condition are more prone to the development of malignancy (see Prognosis).

Inflammatory bowel disease. Severe colitis noted during colonoscopy in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease. The mucosa is grossly denuded, with active bleeding noted. The patient had her colon resected very shortly after this view was obtained.

Inflammatory bowel disease. Stricture in the terminal ileum noted during colonoscopy in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease. This image depicts a narrowed segment visible upon intubation of the terminal ileum with the colonoscope. Relatively little active inflammation is present, indicating that this is a cicatrix stricture.

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease share many extraintestinal manifestations, although some of these tend to occur more commonly with either condition (see the image below). Eye-skin-mouth-joint extraintestinal manifestations (eg, oral aphthae, erythema nodosum, large-joint arthritis, and episcleritis) reflect active disease, whereas pyoderma gangrenosum, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), ankylosing spondylitis, uveitis, kidney stones, and gallstones may occur in quiescent disease. [5]

Although both ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease have distinct pathologic findings, approximately 10%-15% of patients cannot be classified definitively into either type; in such patients, the disease is labeled as indeterminate colitis. Systemic symptoms are common in IBD and include fever, sweats, malaise, and arthralgias.

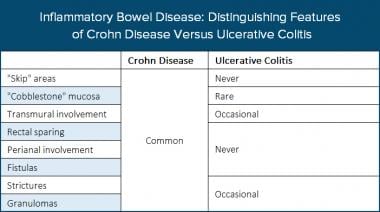

Inflammatory bowel disease. The table distinguishes features of Crohn disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).

The rectum is always involved in ulcerative colitis, and the disease primarily involves continuous lesions of the mucosa and the submucosa. Both ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease usually have waxing and waning intensity and severity. When the patient is symptomatic due to active inflammation, the disease is considered to be in an active stage (the patient is having a flare of the IBD). (See Presentation.)

In many cases, symptoms correspond well to the degree of inflammation present for either disease, although this is not universally true. In some patients, objective evidence linking active disease to ongoing inflammation should be sought before administering medications with significant adverse effects (see Medication), because patients with IBD can have other reasons for their gastrointestinal symptoms unrelated to their IBD, including coexisting irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), celiac disease, or other confounding diagnoses, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) effects and ischemic or infectious colitis.

Although ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease have significant differences, many, but not all, of the treatments available for one condition are also effective for the other. Surgical intervention for ulcerative colitis is curative for colonic disease and potential colonic malignancy, but it is not curative for Crohn disease. (See Treatment.)

Pathophysiology

The common end pathway of ulcerative colitis is inflammation of the mucosa of the intestinal tract, causing ulceration, edema, bleeding, and fluid and electrolyte loss. [6] In several studies, genetic factors appeared to influence the risk of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) by causing a disruption of epithelial barrier integrity, deficits in autophagy, [7] deficiencies in innate pattern recognition receptors, and problems with lymphocyte differentiation, especially in Crohn disease. [8]

Inflammatory mediators have been identified in IBD, and considerable evidence suggests that these mediators play an important role in the pathologic and clinical characteristics of these disorders. Cytokines, which are released by macrophages in response to various antigenic stimuli, bind to different receptors and produce autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine effects. Cytokines differentiate lymphocytes into different types of T cells. Helper T cells, type 1 (Th-1), are associated principally with Crohn disease, whereas Th-2 cells are associated principally with ulcerative colitis. The immune response disrupts the intestinal mucosa and leads to a chronic inflammatory process. [9]

In animal studies, a local irritant (eg, acetic acid, trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid) can be inserted via an enema into the colon of rats or rabbits to induce a chemical colitis. An interleukin-10 (IL-10) knockout mouse has been genetically engineered to have some characteristics similar to those of a human with IBD. The cotton-top marmoset, a South American primate, develops colitis very similar to ulcerative colitis when the animal is subjected to stress.

Ulcerative colitis

In ulcerative colitis, the inflammation begins in the rectum and extends proximally in an uninterrupted fashion to the proximal colon and could eventually involve the entire length of the large intestine. The rectum is always involved in ulcerative colitis; and unlike in Crohn disease, there are no "skip areas" (ie, normal areas of the bowel interspersed with diseased areas), unless pretreated with topical rectal therapy (ie, a steroid or 5-aminosalicylic acid [5-ASA] enema).

The disease remains confined to the rectum in approximately 25% of cases, and in the remainder of cases, ulcerative colitis spreads proximally and contiguously. Pancolitis occurs in 10% of patients. The distal terminal ileum may become inflamed in a superficial manner, referred to as backwash ileitis. Even with less than total colonic involvement, the disease is strikingly and uniformly continuous. As ulcerative colitis becomes chronic, the colon becomes a rigid foreshortened tube that lacks its usual haustral markings, leading to the lead-pipe appearance observed on barium enema. (See the images below.)

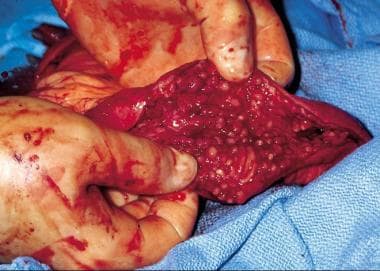

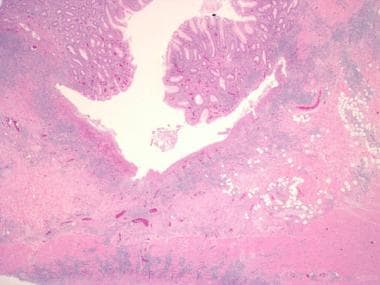

Inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamed colonic mucosa demonstrating pseudopolyps in a patient with ulcerative colitis.

Inflammatory bowel disease. Double-contrast barium enema study shows pseudopolyposis of the descending colon in a patient with ulcerative colitis.

Crohn disease

Crohn disease can affect any portion of the gastrointestinal tract, from the mouth to the anus, and causes three patterns of involvement: inflammatory disease, strictures, and fistulas. This disease consists of segmental involvement by a nonspecific granulomatous inflammatory process. The most important pathologic feature of Crohn disease is that it is transmural, involving all layers of the bowel, not just the mucosa and the submucosa, which is characteristic of ulcerative colitis. Furthermore, Crohn disease is discontinuous, with skip areas interspersed between two or more involved areas.

Late in the disease, the mucosa develops a cobblestone appearance, which results from deep, longitudinal ulcerations interlaced with intervening normal mucosa (see the images below). In 35% of cases, Crohn disease occurs in the ileum and colon; in 32%, solely in the colon; in 28%, in the small bowel; and in 5%, in the gastroduodenal region. [10] Diarrhea, cramping, and abdominal pain are common symptoms of Crohn disease in all of the above locations, except for the gastroduodenal region, in which anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are more common. [10]

Rectal sparing is a typical but not constant feature of Crohn disease. However, anorectal complications (eg, fistulas, abscesses) are common. Much less commonly, Crohn disease involves the more proximal parts of the GI tract, including the mouth, tongue, esophagus, stomach, and duodenum.

Inflammatory bowel disease. Cobblestone change of the mucosa of the terminal ileum in a patient with Crohn disease. Communicating fissures and crevices in the mucosa separate islands of more intact, edematous epithelium.

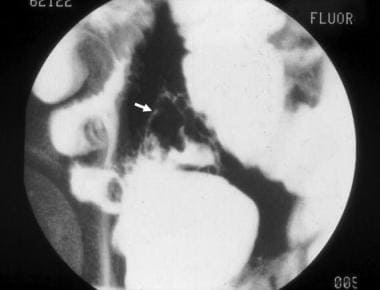

Inflammatory bowel disease. This computed tomography scan from a patient with terminal ileal Crohn disease shows an enteroenteral fistula (arrow) between loops of diseased small intestine.

Inflammatory bowel disease. Another example of a deep, fissuring ulcer in a patient with Crohn disease. Note the increase in submucosal inflammation and scattered lymphoid aggregates.

Cholelithiasis and nephrolithiasis

The incidence of gallstones and kidney stones is increased in Crohn disease because of malabsorption of fat and bile salts. Gallstones are formed because of increased cholesterol concentration in the bile, which is caused by a reduced bile salt pool.

Patients who have Crohn disease with ileal disease or ileal resection are also likely to form calcium oxalate kidney stones. With the fat malabsorption, unabsorbed long-chain fatty acids bind calcium in the lumen. Oxalate in the lumen is normally bound to calcium. Calcium oxalate is poorly soluble and poorly absorbed; however, if calcium is bound to malabsorbed fatty acids, oxalate combines with sodium to form sodium oxalate, which is soluble and is absorbed in the colon (enteric hyperoxaluria). The development of calcium oxalate stones in Crohn disease requires an intact colon to absorb oxalate. Patients with ileostomies generally do not develop calcium oxalate stones, but they may develop uric acid or mixed stones. [11]

Etiology

Three characteristics define the etiology of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): (1) genetic predisposition; (2) an altered, dysregulated immune response; and (3) an altered response to gut microorganisms. However, the triggering event for the activation of the immune response in IBD has yet to be identified. Possible factors related to this event include a pathogenic organism (as yet unidentified) or an inappropriate response (ie, failure to downgrade the inflammatory response to an antigen, such as an alteration in barrier function).

No mechanism has been implicated as the primary cause, but many are postulated. The lymphocyte population in persons with IBD is polyclonal, making the search for a single precipitating cause difficult. In any case, an inappropriate activation of the immune system leads to continued inflammation of the intestinal tract, with both an acute (neutrophilic) and chronic (lymphocytic, histiocytic) inflammatory response.

Several environmental risk factors have been proposed as contributing to the IBD pathogenesis, but the results are inconsistent, and the limitations of the studies preclude drawing firm conclusions. The most consistent association described has been smoking, which increases the risk of Crohn disease. However, current smoking protects against ulcerative colitis, whereas former smoking increases the risk of ulcerative colitis. Dietary factors have also been inconsistently described. In some studies, high fiber intake and high intake of fruits and vegetables appear protective against IBD. [12] The E3N prospective study found that high animal protein intake (meat or fish) carried a higher risk of IBD. [13]

Genetics

Persons with IBD have a genetic susceptibility for the disease, [14] and considerable research over the past decade has improved our understanding of the role of these genes. Note that these genes appear to be permissive (ie, allow IBD to occur), but they are not causative (ie, just because the gene is present does not necessarily mean the disease will develop).

First-degree relatives have a 5- to 20-fold increased risk of developing IBD, as compared with persons from unaffected families. [6, 8] The child of a parent with IBD has a 5% risk of developing IBD. Twin studies show a concordance of approximately 70% in identical twins, versus 5%-10% in nonidentical twins. Of patients with IBD, 10%-25% are estimated to have a first-degree relative with the disease. Monozygous twin studies show a high concordance for Crohn disease but less so for ulcerative colitis.

Crohn disease

An early discovery on chromosome 16 (IBD1 gene) led to the identification of 3 single nucleotide polymorphisms (2 missense, 1 frameshift) in the NOD2 gene (now called CARD15) as the first gene (CARD15) clearly associated with IBD (as a susceptibility gene for Crohn disease). CARD15 is a polymorphic gene involved in the innate immune system. The gene has more than 60 variations, of which 3 play a role in 27% of patients with Crohn disease, primarily in patients with ileal disease.

Subsequent studies have suggested that the CARD15 genotype is associated not only with the onset of the disease but also with its natural history. A study on a German and Norwegian cohort showed that patients with 1 of the 3 identified risk alleles for CARD15 were more likely to have either ileal or right colonic disease. [15, 16] These gene products appear to be involved in the intracellular innate immune pathways that recognize microbial products in the cytoplasm.

Another early genome-wide association study looked at Jewish and non-Jewish case-control cohorts and identified 2 single nucleotide polymorphisms in the IL23R gene, which encodes 1 subunit of the interleukin-23 receptor protein. [17] Interestingly, this study also described the promising nature of certain therapies that block the function of IL-23. Further research suggested that one particular polymorphism in the IL23R gene showed the strongest association in a German population. [18] However, another study found that the Arg381Gln substitution is associated with childhood onset of IBD in Scotland. [19] These gene products appear to be involved in regulating adaptive immunity.

Numerous other loci have been identified as conferring susceptibility to Crohn disease, including several large meta-analyses that found multiple novel susceptibility loci and confirmed earlier findings. In one meta-analysis of 3 genome-wide association scans, 526 single nucleotide polymorphisms from 74 distinct genomic loci were found. [20] In sorting out loci that have been previously discussed, there were 21 new loci that were associated with an increased risk of developing Crohn Disease and have functional implications, including the genes CCR6, IL12B, STAT3, JAK2, LRRK2, CDKAL1, and PTPN22. [20] Most of these genes are involved in signal transduction in the immune function.

The interlectin gene (ITLN1) is expressed in the small bowel and colon, and it is also involved in the recognition of certain microorganisms in the intestine. Other genome-wide association studies have found associations between susceptibility to Crohn disease and polymorphisms in genes that are associated with the intestinal milieu. One such study examined nearly 20,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms in 735 individuals with Crohn disease. [21] An association was found with the ATG16L1 gene, which encodes the autophagy-related 16-like protein, which is involved in the autophagosome pathway that processes intracellular bacteria. [21]

Single nucleotide polymorphisms in other autophagy genes have also shown association with susceptibility to Crohn disease, such as 2 polymorphisms that flanked the IRGM gene and may exert regulatory control for the gene. [22] Subsequently, there have been a number of other loci implicated in the autophagy pathway that have been associated with Crohn disease. [7]

There is strong support for IBD-susceptibility genes on chromosome 5p13.1, which is a gene desert but does modulate expression of the PTGER4 gene. A murine PTGER4 knockout model has significant susceptibility to severe colitis. [23] A large genomic study of multiple diseases confirmed many of the findings that were found in earlier studies, as well as several additional loci of interest for Crohn disease. [24]

Disruption of a homologous gene in a murine model resulted in defective development of the intestine. [25] It was hypothesized that changes in the expression of this gene could alter the migration of lymphocytes in the intestine and change its inflammatory response. The last locus discussed in this model is immediately upstream of the PTPN2 on chromosome 18p11 and encodes a T cell protein tyrosine phosphatase, which is a negative regulator of inflammation. [25]

Ulcerative colitis

The genetic predisposition for ulcerative colitis appears to be lesser in magnitude than Crohn disease but consists of a set of genetic susceptibilities that shows significant overlap with Crohn disease. One genome-wide association study found a previously unknown susceptibility locus at ECM1 and also showed several risk loci that were common to both ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease. [26] Genes that confer risk for both diseases appear to influence the immune milieu of the intestine, whereas the genes that influence only Crohn disease appear to be involved mainly in autophagy. [26, 27]

Additional susceptibility loci for ulcerative colitis have been found on 1p36 and 12q15. The 1p36 single nucleotide polymorphism is near the PLA2G2E gene, which is involved in releasing arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids, leading to other proinflammatory lipids. The first 12q15 signal is located near the interferon (IFN)-gamma, interleukin (IL)-26, and IL-22 genes, whereas the second 12q15 signal is located in IL-26 gene. These genes play roles in the immune response to pathogens as well as the tissue inflammation processes. [28]

Data suggest that genetic influences increase the risk for one form of IBD while decreasing the risk for another. In a Japanese population, the HLA-Cw*1202-B*5201-DRB1*1502 haplotype increases the risk for ulcerative colitis but reduces the risk for Crohn disease. [29] This finding has not been replicated in other ethnic groups. However, as the authors noted, the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) type in question in this study is relatively common in the Japanese population but relatively rare in European populations. They suggest that the HLA type will favor a T-helper immune response, predisposing toward ulcerative colitis, as opposed to an IFN-predominant response, predisposing more toward Crohn disease. [29]

Smoking

The risk of developing ulcerative colitis is higher in nonsmokers and former smokers than in current smokers. The onset of ulcerative colitis occasionally appears to coincide with smoking cessation; however, this does not imply that smoking would improve the symptoms of ulcerative colitis. There has been limited success with the use of nicotine patches. Crohn disease patients have a higher incidence of smoking than the general population, and smoking appears to lessen the response to medical therapy.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Before 1960, the incidence of ulcerative colitis was several times higher than that of Crohn disease. More recent data suggest that the incidence of Crohn disease is approaching that of ulcerative colitis.

Annually, an estimated 700,000 physician visits and 100,000 hospitalizations are due to IBD. [30] Approximately 1-2 million people in the United States have ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease, with an incidence of 70-150 cases per 100,000 individuals. [31, 32] In persons of European descent in Olmstead County, Minnesota, the incidence of ulcerative colitis was 7.3 cases per 100,000 people per year, with a prevalence of 116 cases per 100,000 people; the incidence of Crohn disease was 5.8 cases per 100,000 people per year, with a prevalence of 133 cases per 100,000 people. [33, 34]

Racial, sexual, and age-related differences

The incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) among Americans of African descent is estimated to be the same as the prevalence among Americans of European descent, with the highest rates in the Jewish populations of middle European extraction. [35] There is a higher prevalence along a north-south axis in the United States [36] and in Europe, [37] although trends show that the gap is narrowing.

The male-to-female ratio is approximately 1:1 for ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease, with females having a slightly greater incidence. Both diseases are most commonly diagnosed in young adults (ie, late adolescence to the third decade of life).

The age distribution of newly diagnosed IBD cases is bell-shaped; the peak incidence occurs in people in the early part of the second decade of life, with the vast majority of new diagnoses made in people aged 15-40 years. A second, smaller peak in incidence occurs in patients aged 55-65 years and is increasing. Approximately 10% of IBD patients are younger than 18 years.

International statistics

The highest rates of IBD are assumed to be in developed countries, and the lowest are considered to be in developing regions; colder-climate regions and urban areas have a greater rate of IBD than those of warmer climates and rural areas. Internationally, the incidence of IBD is approximately 0.5-24.5 cases per 100,000 person-years for ulcerative colitis and 0.1-16 cases per 100,000 person-years for Crohn disease. [30] Overall, the prevalence for IBD is 396 cases per 100,000 persons annually. [30]

A review of IBD reported that the prevalence of Crohn disease in North America was 319 per 100,000 persons, whereas in Europe, it was 322 per 100,000 persons. [31] Prevalence rates for ulcerative colitis were 249 per 100,000 persons in North America and 505 per 100,000 persons in Europe. The annual incidence of Crohn disease was 20.2 per 100,000 person-years in North America, 12.7 per 100,000 person-years in Europe, and 5.0 per 100,000 person-years in Asia and the Middle East, whereas incidence rates of ulcerative colitis were 19.2 per 100,000 person-years in North America, 24.3 per 100,000 person-years in Europe, and 6.3 per 100,000 person-years in Asia and the Middle East. Time-trend analyses showed statistically significant increases in the incidence of IBD over time. [31]

Prognosis

The standardized mortality ratio for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) ranges from approximately 1.4 times the general population (Sweden) to 5 times the general population (Spain). Most of this increase appears to be in the Crohn disease population; the ulcerative colitis population appears to have the same mortality rate as the general population. [38]

The majority of studies indicate a small but significant increase in mortality associated with IBD. [39] A frequent cause of death in persons with IBD is the primary disease [40] ; infections and COPD/respiratory illness are other major causes of death. [41] IBD is not a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality. [42]

Patients with IBD are more prone to the development of malignancy. Persons with Crohn disease have a higher rate of small bowel malignancy. Patients with pancolitis, particularly ulcerative colitis, are at a higher risk of developing colonic malignancy after 8-10 years of disease. The current standard of practice is to screen patients with colonoscopy at 1-2 year intervals once they have had the disease for greater than 10 years.

A comprehensive discussion regarding the diagnosis, management, and surveillance of colorectal cancer in patients with IBD is beyond the scope of this article. For more information, see the following two guidelines:

Morbidity

In addition to long-term, disease-related complications, patients can also experience morbidity from prolonged medical therapy, particularly as a consequence of steroid exposure.

There also appears to be an increased risk for IBD in patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In a population-based retrospective cohort study of 136,178 individuals with asthma and 143,904 individuals with COPD, Brassard and colleagues found a significantly increased incidence of IBD. The average incidences of CD and UC in asthma patients were 23.1 and 8.8/100,000 person-years, respectively. Corresponding figures in COPD patients were 26.2 CD and 17 UC cases/100,000 person-years, respectively. [46, 47]

Compared with the general population, the incidence of CD in asthma and COPD patients was 27% and 55% higher, and the incidence of UC was 30% higher among those with COPD. Among children up to 10 years old in the asthma group and adults aged 50 to 59 in the COPD group, the incidence of CD was more than twice that seen in the general population. [46, 47]

Psychologic morbidity affects patients with IBD, especially younger patients, and are typically associated with depression and anxiety symptoms but also exhibit externalizing behaviors. [48] Risk factors for psychologic morbidity appear to include increased disease severity, lower socioeconomic status, use of corticosteroids, parental stress, and older age at diagnosis. [48]

Ulcerative colitis

The average patient with ulcerative colitis has a 50% probability of having another flare during the next 2 years; however, patients may have only one flare over 25 years, and others may have almost persistently active disease. A small percentage of patients with ulcerative colitis have a single attack and no recurrence. Typically, remissions and exacerbations are characteristic of this disease, with acute attacks lasting weeks to months.

Patients with ulcerative colitis limited to the rectum and sigmoid have a 50% chance of progressing to more extensive disease over 10 years [49] and a 7.5% rate of colectomy over 5 years. [50] Approximately 10% of patients presenting with proctitis will develop a pancolitis. [49, 50]

Surgical resection for ulcerative colitis is considered “curative” for this disease, although patients may experience symptoms related to the ileal pouch (J-pouch), including acute and chronic pouchitis. Pouchitis is far more common in patients who have had a colectomy for ulcerative colitis than in those who have had a colectomy for familial adenomatous polyposis.

Beyond 8-10 years after diagnosis, the risk of colorectal cancer increases by 0.5%-1.0% per year. Surveillance colonoscopies with random biopsies reduce mortality from colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis by allowing the detection of low- or high-grade dysplasia and early stage carcinoma.

Crohn disease

The clinical course of Crohn disease is much more variable than that of ulcerative colitis, and it is dependent on the anatomic location and extent of the disease. Periodic remissions and exacerbations are the rule in Crohn disease. The relapse rate over 10 years is 90%, and the cumulative probability of requiring surgery over 10 years is approximately 38%. Terminal ileum location, fistulizing, and structuring disease are all independent risk factors for subsequent surgery. [51]

A review of the literature indicates that approximately 80% of patients who are in remission for one year will remain in remission over subsequent years. [52] Patients with active disease in the past year have a 70% chance of having clinical disease activity in the following year. Approximately 20% of patients will have annual relapses, and 13% will have a course free of relapses. Less than 5% of patients with Crohn disease will have continually active disease. [52]

Surgery for Crohn disease is generally performed for complications (eg, stricture, stenosis, obstruction, fistula, bleeding, or abscess). Surgical intervention is an important treatment option for Crohn disease, but patients should be aware that it is not curative and that disease recurrence after surgery is high, mimicking the original disease pattern at the site of the surgical anastomosis.

Recurrence of perianal fistulas after medical or surgical treatment is common (59%-82%). [52] In one study, one year after surgery for Crohn disease, 20%-37% of patients had symptoms suggestive of clinical recurrence, and endoscopic evidence of recurrent inflammation was in the neoterminal ileum in 48%-93% of patients. [53]

Overall, the patient's quality of life with Crohn disease is generally lower than that of individuals with ulcerative colitis. Data suggest that in persons with Crohn colitis involving the entire colon, the risk of developing malignancy is equal to that in persons with ulcerative colitis; however, the risk is much smaller (albeit poorly quantified) in most patients with Crohn disease primarily involving the small bowel. Intestinal cancer may become a more important long-term complication in patients with Crohn disease because of longer survival.

Studies support evidence that specific CARD15 mutations are associated with the intestinal location of the disease, as well as course and prognosis, [8] and are correlated with the propensity for developing ileal strictures and with an early onset of disease.

Complications of IBD disease

Intestinal complications

IBD can be associated with several gastrointestinal complications, including risk of hemorrhage, perforation, strictures, and fistulas—as well as perianal disease and related complications, such as perianal or pelvic abscesses, toxic megacolon (complicating acute severe colitis), and malignancy (colorectal cancer, cholangiocarcinoma complicating primary sclerosing cholangitis).

Extraintestinal complications

Extraintestinal complications occur in approximately 20%-25% of patients with IBD. [1] In some cases, they may be more symptomatic than the bowel disease itself. These include osteoporosis (usually a consequence of prolonged corticosteroid use), hypercoagulability resulting in venous thromboembolism, anemia, gallstones, primary sclerosing cholangitis, aphthous ulcers, arthritis, iritis (uveitis) and episcleritis, and skin complications (pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum).

Table 1, below, summarizes the rates of the most common extraintestinal complications in patients with IBD the United States and Europe.

Table 1. Common Extraintestinal Complications of IBD in US and Europe [54] (Open Table in a new window)

| Complication | Prevalence |

|---|---|

| Scleritis | 18% |

| Anterior uveitis | 17% |

| Gall stones (particularly in Crohn disease) | 13%-34% |

| Inflammatory arthritis | 10%-35% |

| Anemia | 9%-74% |

| Aphthous stomatitis | 4%-20% |

| Osteoporosis | 2%-20% |

| Erythema nodosum | 2%-20% |

| Source: Larson S, Bendtzen K, Nielsen OH. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Ann Med. 2010;42:97-114. |

The Swiss National IBD Cohort Study also demonstrated the risks of extraintestinal complications of IBD; their results are summarized in Table 2, below. [55] The risk factors of having complications included family history and active disease observed for Crohn disease only; no significant risk factors were noted in patients with ulcerative colitis. [55]

Table 2. Extraintestinal Complications of IBD in Swiss Patients [55] (Open Table in a new window)

| Complication | Crohn Disease | Ulcerative Colitis |

|---|---|---|

| Arthritis | 33% | 4% |

| Aphthous stomatitis | 10% | 4% |

| Uveitis | 6% | 3% |

| Erythema nodosum | 6% | 3% |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 6% | 2% |

| Psoriasis | 2% | 1% |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | 2% | 2% |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 1% | 4% |

| Source: Vavricka SR, Brun L, Ballabeni P, et al. Frequency and risk factors for extraintestinal manifestations in the Swiss inflammatory bowel disease cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:110-9. |

Patient Education

Because inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, often lifelong disease that is frequently diagnosed in young adulthood, increasing patient knowledge improves medical compliance and assists in the management of symptoms.

Encourage the patient to join an IBD support group, such as the Crohn's & Colitis Foundation of America. This foundation can provide educational materials for patients and educational brochures for physicians.

Crohn's & Colitis Foundation of America

733 Third Avenue

Suite 510

New York, NY 10017

Phone: 800-932-2423

E-mail: info@ccfa.org

- World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guideline. Inflammatory bowel disease: a global perspective. Munich, Germany: World Gastroenterology Organisation (WGO); 2009.

- American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: perianal Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2003 Nov. 125(5):1503-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kornbluth A, Sachar DB. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Mar. 105(3):501-23; quiz 524. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kiran RP, Nisar PJ, Church JM, Fazio VW. The role of primary surgical procedure in maintaining intestinal continuity for patients with Crohn's colitis. Ann Surg. 2011 Jun. 253(6):1130-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Agrawal D, Rukkannagari S, Kethu S. Pathogenesis and clinical approach to extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2007 Sep. 53(3):233-48. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Thoreson R, Cullen JJ. Pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease: an overview. Surg Clin North Am. 2007 Jun. 87(3):575-85. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rioux JD, Xavier RJ, Taylor KD, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for Crohn disease and implicates autophagy in disease pathogenesis. Nat Genet. 2007 May. 39(5):596-604. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Tsianos EV, Katsanos KH, Tsianos VE. Role of genetics in the diagnosis and prognosis of Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Jan 14. 18(2):105-18. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lashner B. Inflammatory bowel disease. Carey WD, ed. Cleveland Clinic: Current Clinical Medicine -- 2009. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2009.

- Wilkins T, Jarvis K, Patel J. Diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease. Am Fam Physician. 2011 Dec 15. 84(12):1365-75. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Trinchieri A, Lizzano R, Castelnuovo C, Zanetti G, Pisani E. Urinary patterns of patients with renal stones associated with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2002 Jun. 74(2):61-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Amre DK, D'Souza S, Morgan K, et al. Imbalances in dietary consumption of fatty acids, vegetables, and fruits are associated with risk for Crohn's disease in children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Sep. 102(9):2016-25. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Jantchou P, Morois S, Clavel-Chapelon F, Boutron-Ruault MC, Carbonnel F. Animal protein intake and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: The E3N prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Oct. 105(10):2195-201. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bengtson MB, Solberg IC, Aamodt G, Jahnsen J, Moum B, Vatn MH. Relationships between inflammatory bowel disease and perinatal factors: both maternal and paternal disease are related to preterm birth of offspring. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010 May. 16(5):847-55. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hampe J, Grebe J, Nikolaus S, et al. Association of NOD2 (CARD 15) genotype with clinical course of Crohn's disease: a cohort study. Lancet. 2002 May 11. 359(9318):1661-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zouali H, et al. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001 May 31. 411(6837):599-603. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Duerr RH, Taylor KD, Brant SR, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 2006 Dec 1. 314(5804):1461-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Glas J, Seiderer J, Wetzke M, et al. rs1004819 is the main disease-associated IL23R variant in German Crohn's disease patients: combined analysis of IL23R, CARD15, and OCTN1/2 variants. PLoS One. 2007 Sep 5. 2(9):e819. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Nimmo ER, et al. IL23R Arg381Gln is associated with childhood onset inflammatory bowel disease in Scotland. Gut. 2007 Aug. 56(8):1173-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Barrett JC, Hansoul S, Nicolae DL, et al. Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn's disease. Nat Genet. 2008 Aug. 40(8):955-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Hampe J, Franke A, Rosenstiel P, et al. A genome-wide association scan of nonsynonymous SNPs identifies a susceptibility variant for Crohn disease in ATG16L1. Nat Genet. 2007 Feb. 39(2):207-11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Parkes M, Barrett JC, Prescott NJ, et al. Sequence variants in the autophagy gene IRGM and multiple other replicating loci contribute to Crohn's disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2007 Jul. 39(7):830-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Libioulle C, Louis E, Hansoul S, et al. Novel Crohn disease locus identified by genome-wide association maps to a gene desert on 5p13.1 and modulates expression of PTGER4. PLoS Genet. 2007 Apr 20. 3(4):e58. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Hedin C, Whelan K, Lindsay JO. Evidence for the use of probiotics and prebiotics in inflammatory bowel disease: a review of clinical trials. Proc Nutr Soc. 2007 Aug. 66(3):307-15. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007 Jun 7. 447(7145):661-78. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Fisher SA, Tremelling M, Anderson CA, et al. Genetic determinants of ulcerative colitis include the ECM1 locus and five loci implicated in Crohn's disease. Nat Genet. 2008 Jun. 40(6):710-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Weersma RK, Zhernakova A, Nolte IM, et al. ATG16L1 and IL23R are associated with inflammatory bowel diseases but not with celiac disease in the Netherlands. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Mar. 103(3):621-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Silverberg MS, Cho JH, Rioux JD, et al. Ulcerative colitis-risk loci on chromosomes 1p36 and 12q15 found by genome-wide association study. Nat Genet. 2009 Feb. 41(2):216-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Okada Y, Yamazaki K, Umeno J, et al. HLA-Cw*1202-B*5201-DRB1*1502 haplotype increases risk for ulcerative colitis but reduces risk for Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2011 Sep. 141(3):864-871.e1-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Available at https://www.cdc.gov/ibd/#epidIBD. Accessed: August 6, 2012.

- Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012 Jan. 142(1):46-54.e42; quiz e30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Loftus EV Jr. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004 May. 126(6):1504-17. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Loftus EV Jr, Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gut. 2000 Mar. 46(3):336-43. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Loftus EV Jr, Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Crohn's disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gastroenterology. 1998 Jun. 114(6):1161-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Roth MP, Petersen GM, McElree C, Feldman E, Rotter JI. Geographic origins of Jewish patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989 Oct. 97(4):900-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sonnenberg A, McCarty DJ, Jacobsen SJ. Geographic variation of inflammatory bowel disease within the United States. Gastroenterology. 1991 Jan. 100(1):143-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Shivananda S, Lennard-Jones J, Logan R, et al. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease across Europe: is there a difference between north and south? Results of the European Collaborative Study on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EC-IBD). Gut. 1996 Nov. 39(5):690-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Langholz E. Current trends in inflammatory bowel disease: the natural history. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2010 Mar. 3(2):77-86. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Card T, Hubbard R, Logan RF. Mortality in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2003 Dec. 125(6):1583-90. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Jess T, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, et al. Survival and cause specific mortality in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a long term outcome study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-2004. Gut. 2006 Sep. 55(9):1248-54. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Hutfless SM, Weng X, Liu L, Allison J, Herrinton LJ. Mortality by medication use among patients with inflammatory bowel disease, 1996-2003. Gastroenterology. 2007 Dec. 133(6):1779-86. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Dorn SD, Sandler RS. Inflammatory bowel disease is not a risk factor for cardiovascular disease mortality: results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Mar. 102(3):662-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Farraye FA, Odze RD, Eaden J, et al. AGA medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2010 Feb. 138(2):738-45. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- AGA medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. 2010. Available at https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(09)02202-1/fulltext. Accessed: August 6, 2012.

- Colonoscopic surveillance for prevention of colorectal cancer in people with ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease or adenomas. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE); 2011. Available at https://guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=34830. Accessed: August 6, 2012.

- Barclay L. COPD, asthma may up risk for inflammatory bowel disease. Medscape Medical News by WebMD. November 20, 2014. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/835213. Accessed: November 22, 2014.

- Brassard P, Vutcovici M, Ernst P, et al. Increased incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Québec residents with airway diseases. Eur Respir J. 2015 Apr. 45(4):962-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Brooks AJ, Rowse G, Ryder A, Peach EJ, Corfe BM, Lobo AJ. Systematic review: psychological morbidity in young people with inflammatory bowel disease - risk factors and impacts. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016 Jul. 44(1):3-15. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Meucci G, Vecchi M, Astegiano M, et al. The natural history of ulcerative proctitis: a multicenter, retrospective study. Gruppo di Studio per le Malattie Infiammatorie Intestinali (GSMII). Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Feb. 95(2):469-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Henriksen M, Jahnsen J, Lygren I, et al. Ulcerative colitis and clinical course: results of a 5-year population-based follow-up study (the IBSEN study). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Jul. 12(7):543-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Solberg IC, Vatn MH, Hoie O, et al. Clinical course in Crohn's disease: results of a Norwegian population-based ten-year follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Dec. 5(12):1430-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lichtenstein GR, Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ. Management of Crohn's disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Feb. 104(2):465-83; quiz 464, 484. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Buisson A, Chevaux JB, Allen PB, Bommelaer G, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Review article: the natural history of postoperative Crohn's disease recurrence. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012 Mar. 35(6):625-33. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Larsen S, Bendtzen K, Nielsen OH. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Ann Med. 2010 Mar. 42(2):97-114. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Vavricka SR, Brun L, Ballabeni P, et al. Frequency and risk factors for extraintestinal manifestations in the Swiss inflammatory bowel disease cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Jan. 106(1):110-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Bernstein CN, Fried M, Krabshuis JH, et al. World Gastroenterology Organization Practice Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of IBD in 2010. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010 Jan. 16(1):112-24. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gisbert JP, McNicholl AG. Questions and answers on the role of faecal calprotectin as a biological marker in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2009 Jan. 41(1):56-66. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Reuters Health. Study backs wider use of fecal calprotectin in pediatric IBD workup. Medscape Medical News by WebMD. May 27, 2013. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/804796. Accessed: June 1, 2013.

- Henderson P, Anderson NH, Wilson DC. The diagnostic accuracy of fecal calprotectin during the investigation of suspected pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 May. 109(5):637-45. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Lichtenstein GR, Abreu MT, Cohen R, Tremaine W. American Gastroenterological Association Institute medical position statement on corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2006 Mar. 130(3):935-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Prideaux L, De Cruz P, Ng SC, Kamm MA. Serological antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012 Jul. 18(7):1340-55. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- D'Inca R, Dal Pont E, Di Leo V, et al. Calprotectin and lactoferrin in the assessment of intestinal inflammation and organic disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007 Apr. 22(4):429-37. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Panes J, Bouzas R, Chaparro M, et al. Systematic review: the use of ultrasonography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis, assessment of activity and abdominal complications of Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Jul. 34(2):125-45. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rimola J, Ordas I, Rodriguez S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for evaluation of Crohn's disease: validation of parameters of severity and quantitative index of activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Aug. 17(8):1759-68. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Paulsen SR, Huprich JE, Fletcher JG, et al. CT enterography as a diagnostic tool in evaluating small bowel disorders: review of clinical experience with over 700 cases. Radiographics. 2006 May-Jun. 26(3):641-57; discussion 657-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Guimaraes LS, Fidler JL, Fletcher JG, et al. Assessment of appropriateness of indications for CT enterography in younger patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010 Feb. 16(2):226-32. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Solem CA, Loftus EV Jr, Fletcher JG, et al. Small-bowel imaging in Crohn's disease: a prospective, blinded, 4-way comparison trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008 Aug. 68(2):255-66. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Wilkins T, Jarvis K, Patel J. Diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease. Am Fam Physician. 2011 Dec 15. 84(12):1365-75. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Baumgart DC. Endoscopic surveillance in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: who needs what and when?. Dig Dis. 2011. 29 Suppl 1:32-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Leighton JA, Shen B, Baron TH, et al. ASGE guideline: endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006 Apr. 63(4):558-65. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Li CY, Zhang BL, Chen CX, Li YM. OMOM capsule endoscopy in diagnosis of small bowel disease. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2008 Nov. 9(11):857-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Yamamoto H, Kita H, Sunada K, et al. Clinical outcomes of double-balloon endoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of small-intestinal diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004 Nov. 2(11):1010-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Moschler O, May A, Muller MK, Ell C. Complications in and performance of double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE): results from a large prospective DBE database in Germany. Endoscopy. 2011 Jun. 43(6):484-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gross SA, Stark ME. Initial experience with double-balloon enteroscopy at a U.S. center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008 May. 67(6):890-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gerson LB, Flodin JT, Miyabayashi K. Balloon-assisted enteroscopy: technology and troubleshooting. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008 Dec. 68(6):1158-67. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Amezaga AJ, Van Assche G. Practical approaches to "top-down" therapies for Crohn's disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2016 Jul. 18(7):35. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Froslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007 Aug. 133(2):412-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Schnitzler F, Fidder H, Ferrante M, et al. Mucosal healing predicts long-term outcome of maintenance therapy with infliximab in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009 Sep. 15(9):1295-301. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Baert F, Moortgat L, Van Assche G, et al. Mucosal healing predicts sustained clinical remission in patients with early-stage Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2010 Feb. 138(2):463-8; quiz e10-1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr 15. 362(15):1383-95. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ha C, Kornbluth A. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: where do we stand?. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010 Dec. 12(6):471-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Feagan BG, Lemann M, Befrits R, et al. Recommendations for the treatment of Crohn's disease with tumor necrosis factor antagonists: an expert consensus report. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012 Jan. 18(1):152-60. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hanauer SB. Crohn's disease: step up or top down therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003 Feb. 17(1):131-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ashton JJ, Gavin J, Beattie RM. Exclusive enteral nutrition in Crohn's disease: evidence and practicalities. Clin Nutr. 2019 Feb. 38(1):80-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ford AC, Bernstein CN, Khan KJ, et al. Glucocorticosteroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr. 106(4):590-9; quiz 600. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ardizzone S, Cassinotti A, Duca P, et al. Mucosal healing predicts late outcomes after the first course of corticosteroids for newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Jun. 9(6):483-489.e3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gordon M, Naidoo K, Thomas AG, Akobeng AK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of surgically-induced remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011. (1):CD008414. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sandborn WJ, Regula J, Feagan BG, et al. Delayed-release oral mesalamine 4.8 g/day (800-mg tablet) is effective for patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2009 Dec. 137(6):1934-43.e1-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Papa A, et al. Treatment of relapsing mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis with the probiotic VSL#3 as adjunctive to a standard pharmaceutical treatment: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Oct. 105(10):2218-27. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mach T. Clinical usefulness of probiotics in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006 Nov. 57 Suppl 9:23-33. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Khan KJ, Ullman TA, Ford AC, et al. Antibiotic therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr. 106(4):661-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sandborn WJ, Travis S, Moro L, et al. Once-daily budesonide MMX® extended-release tablets induce remission in patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis: results from the CORE I study. Gastroenterology. 2012 Nov. 143(5):1218-26.e2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Silverman J, Otley A. Budesonide in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011 Jul. 7(4):419-28. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chande N, Wang Y, MacDonald JK, McDonald JW. Methotrexate for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Aug 27. CD006618. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Khan KJ, Dubinsky MC, Ford AC, Ullman TA, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of immunosuppressive therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr. 106(4):630-42. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kotlyar DS, Lewis JD, Beaugerie L, et al. Risk of lymphoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 May. 13(5):847-58.e4; quiz e48-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Vande Casteele N, Ferrante M, Van Assche G, et al. Trough concentrations of infliximab guide dosing for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2015 Jun. 148(7):1320-9.e3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, et al. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr. 106(4):644-59, quiz 660. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rubin DT, Panaccione R, Chao J, Robinson AM. A practical, evidence-based guide to the use of adalimumab in Crohn's disease. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011 Sep. 27(9):1803-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Louis E, Mary JY, Vernier-Massouille G, et al. Maintenance of remission among patients with Crohn's disease on antimetabolite therapy after infliximab therapy is stopped. Gastroenterology. 2012 Jan. 142(1):63-70.e5; quiz e31. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rubin DT, Panaccione R, Chao J, Robinson AM. A practical, evidence-based guide to the use of adalimumab in Crohn's disease. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011 Sep. 27(9):1803-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: new risk factor for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) associated with Tysabri (natalizumab). Available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/ucm288186.htm. Accessed: July 11, 2012.

- Brown T. FDA OKs vedolizumab (Entyvio) for ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s. Medscape Medical News from WebMD. May 20, 2014. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/825449. Accessed: June 1, 2014.

- Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, et al, for the Ustekinumab Crohn's Disease Study Group. A randomized trial of Ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2008 Oct. 135(4):1130-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sandborn, WJ, Sands BE, Gasink C, et al. Reduced rates of Crohn's- related surgeries, hospitalizations and alternate biologic initiation with ustekinumab in the IM-UNITI study through 2 years. Gastroenterology. 2018 May. 154(6) Suppl 1:S-377-8.

- Chen JH, Andrews JM, Kariyawasam V, et al, for the IBD Sydney Organisation and the Australian Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Consensus Working Group. Review article: acute severe ulcerative colitis - evidence-based consensus statements. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016 Jul. 44(2):127-44. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Peyrin-Biroulet L. Anti-TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases: a huge review. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2010 Jun. 56(2):233-43. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- FDA. Drug labels for the Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNFα) blockers now include warnings about infection with Legionella and Listeria bacteria. US Food and Drug Administration. September 7, 2011. Available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/ucm270849.htm. Accessed: April 5, 2012.

- Mokrowiecka A, Daniel P, Slomka M, Majak P, Malecka-Panas E. Clinical utility of serological markers in inflammatory bowel disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009 Jan-Feb. 56(89):162-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kefalakes H, Stylianides TJ, Amanakis G, Kolios G. Exacerbation of inflammatory bowel diseases associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: myth or reality?. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009 Oct. 65(10):963-70. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- de Silva S, Ma C, Proulx MC, et al. Postoperative complications and mortality following colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Nov. 9(11):972-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lazarev M, Ullman T, Schraut WH, Kip KE, Saul M, Regueiro M. Small bowel resection rates in Crohn's disease and the indication for surgery over time: experience from a large tertiary care center. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010 May. 16(5):830-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Clinical Effectiveness Unit. Sexual and reproductive health for individuals with inflammatory bowel disease. London (UK): Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH); 2009.

- Yamamoto T, Nakahigashi M, Umegae S, Matsumoto K. Prospective clinical trial: enteral nutrition during maintenance infliximab in Crohn's disease. J Gastroenterol. 2010. 45(1):24-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Helwick C. Low vitamin D exacerbates inflammatory bowel disease. Medscape Medical News from WebMD. May 21, 2013. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/804509. Accessed: June 1, 2013.

- Ananthakrishnan AN, Cagan A, Gainer VS, et al. Normalization of vitamin D status is associated with reduced risk of surgery and hospitalization in inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2013 May. 144(5 Suppl 1):S-1.

- Raftery TC, Healy M, Cox G, et al. Vitamin D supplementation improves muscle strength, fatigue and quality of life in patients with Crohn's disease in remission: results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2013 May. 144(5 Suppl 1):S-227.

- Johannesson E, Simren M, Strid H, Bajor A, Sadik R. Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 May. 106(5):915-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gisbert JP. Safety of immunomodulators and biologics for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease during pregnancy and breast-feeding. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010 May. 16(5):881-95. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- FactTank - News in the numbers: Baby boomers retire. Pew Research Center. December 29, 2010. Available at https://pewresearch.org/databank/dailynumber/?NumberID=1150. Accessed: August 3, 2012.

- Schnitzler F, Fidder H, Ferrante M, et al. Outcome of pregnancy in women with inflammatory bowel disease treated with antitumor necrosis factor therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Sep. 17(9):1846-54. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zelinkova Z, de Haar C, de Ridder L, et al. High intra-uterine exposure to infliximab following maternal anti-TNF treatment during pregnancy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 May. 33(9):1053-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Roux CH, Brocq O, Breuil V, Albert C, Euller-Ziegler L. Pregnancy in rheumatology patients exposed to anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007 Apr. 46(4):695-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- O'Donnell S, O'Morain C. Review article: use of antitumour necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel disease during pregnancy and conception. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008 May. 27(10):885-94. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Casanova MJ, Chaparro M, Domenech E, et al. Safety of thiopurines and anti-TNF-a drugs during pregnancy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 Mar. 108(3):433-40. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rajaratnam SG, Eglinton TW, Hider P, Fearnhead NS. Impact of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis on female fertility: meta-analysis and systematic review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011 Nov. 26(11):1365-74. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bartels SA, DʼHoore A, Cuesta MA, Bensdorp AJ, Lucas C, Bemelman WA. Significantly increased pregnancy rates after laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy: a cross-sectional study. Ann Surg. 2012 Dec. 256(6):1045-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Beyer-Berjot L, Maggiori L, Birnbaum D, Lefevre JH, Berdah S, Panis Y. A total laparoscopic approach reduces the infertility rate after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a 2-center study. Ann Surg. 2013 Aug. 258(2):275-82. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019 Dec. 68(Suppl 3):s1-s106. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn's disease: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Jan 1. 14 (1):4-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Adamina M, Bonovas S, Raine T, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn's disease: surgical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Feb 10. 14 (2):155-68. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Feuerstein JD, Isaacs KL, Schneider Y, et al, for the AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020 Apr. 158(5):1450-61. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MG, Shetty A, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006 Apr. 55(4):505-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Oren R, Arber N, Odes S, et al. Methotrexate in chronic active ulcerative colitis: a double-blind, randomized, Israeli multicenter trial. Gastroenterology. 1996 May. 110(5):1416-21. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Akbari M, Shah S, Velayos FS, Mahadevan U, Cheifetz AS. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of thiopurines on birth outcomes from female and male patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013 Jan. 19(1):15-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Francella A, Dyan A, Bodian C, Rubin P, Chapman M, Present DH. The safety of 6-mercaptopurine for childbearing patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a retrospective cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2003 Jan. 124(1):9-17. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Garcia-Erce JA, Gomollon F, Munoz M. Blood transfusion for the treatment of acute anaemia in inflammatory bowel disease and other digestive diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Oct 7. 15(37):4686-94. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Granlund AB, Beisvag V, Torp SH, et al. Activation of REG family proteins in colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011 Nov. 46(11):1316-23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Kennedy NA, Rhatigan E, Arnott ID, et al. A trial of mercaptopurine is a safe strategy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease intolerant to azathioprine: an observational study, systematic review and meta-analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. Nov 2013. 38(10):1255-66. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kristensen SL, Ahlehoff O, Lindhardsen J, et al. Prognosis after first-time myocardial infarction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease according to disease activity: nationwide cohort study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014 Nov. 7(6):857-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Stiles S. Ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s flares may raise post-MI risk: registry study. Heartwire News from Medscape by WebMD. October 17, 2014. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/833424. Accessed: October 23, 2014.

- [Guideline] Howdle P, Atkin W, Rutter M, et al. Colonoscopic surveillance for prevention of colorectal cancer in people with ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease or adenomas: clinical guideline 118. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). March, 2011. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg118. Accessed: April 7, 2011.

- Bryant RV, Brain O, Travis SP. Conventional drug therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015 Jan. 50(1):90-112. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Garg SK, Loftus EV Jr. Risk of cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: going up, going down, or still the same?. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016 Jul. 32(4):274-81. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Schaefer JS. MicroRNAs: how many in inflammatory bowel disease?. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016 Jul. 32(4):258-66. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bernstein CN. Does everyone with inflammatory bowel disease need to be treated with combination therapy?. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016 Jul. 32(4):287-93. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Atreya R, Neurath MF. From bench to bedside: molecular imaging in inflammatory bowel diseases. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016 Jul. 32(4):245-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Author

William A Rowe, MD President, Gastroenterology Associates of Central Pennsylvania, PC; Manager, Endoscopy Center of Central Pennsylvania, LLC; Clinical Associate Professor of Surgery, Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery, Milton S Hershey Medical Center, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine

William A Rowe, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Gastroenterological Association, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Coauthor(s)

Gary R Lichtenstein, MD Professor of Medicine, Director, Center for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania

Gary R Lichtenstein, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Gastroenterology, American College of Physicians, American Gastroenterological Association, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Disclosure: Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant or trustee for: Abbott Corp/Abbvie; Actavis; Alaven; CellCeutrix; Celgene; Ferring; Gilead; Hospira; Janssen Orthobiotech; Luitpold/American Regent; Pfizer Pharm; Prometheus Labs; Romark; Salix Pharma/Valeant; Santarus/Receptos/Celgene; Shire Pharma; Takeda; UCB

Received research grant from: Salix Pharm/Valeant; Santarus/Receptos/Celgene; Shire Pharm; UCB

Received author or editor honorarium or book royalty from for: Clinical Advances in Gastroenterology; Gastroenterology and Hepatology; Gastro-Hep Communications; Ironwood; Luitpold/American Regent; Merck; McMahon Publishing; Romark; SLACK Inc; Springer Science and Business Media; Up-To-Date.

Specialty Editor Board

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Received salary from Medscape for employment. for: Medscape.

Chief Editor

Acknowledgements

Mounir Bashour, MD, CM, FRCS(C), PhD, FACS Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology, McGill University; Clinical Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology, Sherbrooke University; Medical Director, Cornea Laser and Lasik MD

Mounir Bashour, MD, CM, FRCS(C), PhD, FACS is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Ophthalmology, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American College of International Physicians, American College of Surgeons, American Medical Association, American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, American Society of Mechanical Engineers, American Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Biomedical Engineering Society, Canadian Medical Association,Canadian Ophthalmological Society, Contact Lens Association of Ophthalmologists, International College of Surgeons US Section, Ontario Medical Association, Quebec Medical Association, and Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

William K Chiang, MD Associate Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, New York University School of Medicine; Chief of Service, Department of Emergency Medicine, Bellevue Hospital Center

William K Chiang, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Clinical Toxicology, American College of Medical Toxicology, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Andrew A Dahl, MD Director of Ophthalmology Teaching, Mid-Hudson Family Practice Institute, The Institute for Family Health; Assistant Professor of Surgery (Ophthalmology), New York College of Medicine

Andrew A Dahl, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American Academy of Ophthalmology, American College of Surgeons, American Medical Association, American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, and Wilderness Medical Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Steven C Dronen, MD, FAAEM Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine, LeConte Medical Center

Steven C Dronen, MD, FAAEM is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Eugene Hardin, MD, FAAEM, FACEP Former Chair and Associate Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Charles Drew University of Medicine and Science; Former Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine, Martin Luther King Jr/Drew Medical Center

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Sarvotham Kini, MD Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA

Sarvotham Kini, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Emergency Physicians, American College of Surgeons, and South Carolina Medical Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Alex J Mechaber, MD, FACP Senior Associate Dean for Undergraduate Medical Education, Associate Professor of Medicine, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine

Alex J Mechaber, MD, FACP is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine, and Society of General Internal Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Hampton Roy Sr, MD Associate Clinical Professor, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Hampton Roy Sr, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Ophthalmology, American College of Surgeons, and Pan-American Association of Ophthalmology

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

William Shapiro, MD Consulting Staff, Department of Urgent Care and Emergency Medicine, Scripps Clinic and Research Foundation

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Medscape Salary Employment

Rajeev Vasudeva, MD, FACG Clinical Professor of Medicine, Consultants in Gastroenterology, University of South Carolina School of Medicine

Rajeev Vasudeva, MD, FACG is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Columbia Medical Society, South Carolina Gastroenterology Association, and South Carolina Medical Association

Disclosure: Pricara Honoraria Speaking and teaching; UCB Consulting fee Consulting