Ulcerative Colitis: Practice Essentials, Background, Anatomy (original) (raw)

Practice Essentials

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is one of the two major types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), along with Crohn disease (CD). Unlike Crohn disease, which can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, ulcerative colitis characteristically involves the large bowel (see the image below). Ulcerative colitis is a lifelong illness that has a profound emotional and social impact on the affected patients.

Ulcerative Colitis. Ulcerative colitis as visualized with a colonoscope.

Signs and symptoms

Patients with UC predominantly complain of the following:

- Rectal bleeding

- Frequent stools

- Mucous discharge from the rectum

- Tenesmus (occasionally)

- Lower abdominal pain and severe dehydration from purulent rectal discharge (in severe cases, especially in the elderly)

In some cases, UC has a fulminant course marked by the following:

- Severe diarrhea and cramps

- Fever

- Leukocytosis

- Abdominal distention

UC is associated with various extracolonic manifestations, as follows:

- Uveitis

- Pyoderma gangrenosum

- Pleuritis

- Erythema nodosum

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Spondyloarthropathies

Other conditions associated with UC include the following:

- Recurrent subcutaneous abscesses unrelated to pyoderma gangrenosum [1]

- Multiple sclerosis [2]

- Immunobullous disease of the skin [3]

Physical findings are typically normal in mild disease, except for mild tenderness in the lower left abdominal quadrant (tenderness or cramps are generally present in moderate to severe disease [4] ). In severe disease, the following may be observed:

- Fever

- Tachycardia

- Significant abdominal tenderness

- Weight loss

The severity of UC can be graded as follows:

- Mild: Bleeding per rectum, fewer than four bowel motions per day

- Moderate: Bleeding per rectum, more than four bowel motions per day

- Severe: Bleeding per rectum, more than four bowel motions per day, and a systemic illness with hypoalbuminemia (< 30 g/L)

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies are useful principally in determining the extent of the disease, excluding other diagnoses, and in assessing the patient’s nutritional status. They may include the following:

- Serologic markers (eg, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies [ANCA], anti– Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies [ASCA])

- Complete blood cell (CBC) count

- Comprehensive metabolic panel

- Inflammation markers (eg, erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], C-reactive protein [CRP])

- Stool assays

Diagnosis is best made with endoscopy and biopsy, on which the following are characteristic findings:

- Abnormal erythematous mucosa, with or without ulceration, extending from the rectum to a part or all of the colon

- Uniform inflammation, without intervening areas of normal mucosa (skip lesions tend to characterize Crohn disease)

- Contact bleeding may also be observed, with mucus identified in the lumen of the bowel

The extent of disease is defined by the following findings on endoscopy:

- Extensive disease: Evidence of UC proximal to the splenic flexure

- Left-side disease: UC present in the descending colon up to, but not proximal to, the splenic flexure

- Proctosigmoiditis: Disease limited to the rectum with or without sigmoid involvement

Imaging modalities that may be considered include the following:

- Plain abdominal radiography

- Double-contrast barium enema examination

- Cross-sectional imaging studies (eg, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography scanning)

- Radionuclide studies

- Angiography

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Medical treatment of mild UC includes the following:

- Mild disease confined to the rectum: Topical mesalazine via suppository (preferred) or budesonide rectal foam

- Left-side colonic disease: Mesalazine suppository and oral aminosalicylate (oral mesalazine is preferred to oral sulfasalazine)

- Systemic steroids, when disease does not quickly respond to aminosalicylates

- Oral budesonide

- After remission, long-term maintenance therapy (eg, once-daily mesalazine)

Medical treatment of acute, severe UC may include the following:

- Hospitalization

- Intravenous high-dose corticosteroids

- Alternative induction medications: Cyclosporine, tacrolimus, infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab

Indications for urgent surgery include the following:

- Toxic megacolon refractory to medical management

- Fulminant attack refractory to medical management

- Uncontrolled colonic bleeding

Indications for elective surgery include the following:

- Long-term steroid dependence

- Dysplasia or adenocarcinoma found on screening biopsy

- Disease being present for 7-10 years

Surgical options include the following [5, 6, 7] :

- Total colectomy (panproctocolectomy) and ileostomy

- Total colectomy

- Ileoanal pouch reconstruction or ileorectal anastomosis

- In an emergency, subtotal colectomy with end-ileostomy

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is one of the two major types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), along with Crohn disease (CD). Unlike Crohn disease, which can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, ulcerative colitis characteristically involves the large bowel (see the images below). Ulcerative colitis is a lifelong illness that has a profound emotional and social impact on the affected patients.

Ulcerative Colitis. Ulcerative colitis as visualized with a colonoscope.

Ulcerative Colitis. Single-contrast enema study in a patient with total colitis shows mucosal ulcers with a variety of shapes, including collar-button ulcers (yellow arrow), in which undermining of the ulcers occurs, and double-tracking ulcers (red arrow), in which the ulcers are longitudinally orientated.

The exact etiology of ulcerative colitis is unknown, but the disease appears to be multifactorial and polygenic. The proposed causes include environmental factors, immune dysfunction, and a likely genetic predisposition. Some have suggested that children of below-average birth weight who are born to mothers with ulcerative colitis have a greater risk of developing the disease. (See Etiology.)

Histocompatibility human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–B27 is identified in most patients with ulcerative colitis, although this finding is not causally associated with the condition and the finding of HLA-B27 does not imply a substantially increased risk for ulcerative colitis. Ulcerative colitis may also be influenced by diet, although diet is thought to play a secondary role. Food or bacterial antigens might exert an effect on the already damaged mucosal lining, which has increased permeability.

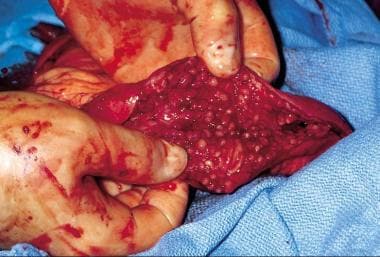

Grossly, the colonic mucosa appears hyperemic, with loss of the normal vascular pattern. The mucosa is granular and friable. Frequently, broad-based ulcerations cause islands of normal mucosa to appear polypoid, leading to the term pseudopolyp (see the image below).

Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamed colonic mucosa demonstrating pseudopolyps.

The bowel wall is thin or of normal thickness, but edema, the accumulation of fat, and hypertrophy of the muscle layer may give the impression of a thickened bowel wall. The disease is largely confined to the mucosa and, to a lesser extent, the submucosa. Muscle-layer and serosal involvement is very rare; such involvement is seen in patients with severe disease, particularly toxic dilatation, and reflects a secondary effect of the severe disease rather than primary ulcerative colitis pathogenesis. Early disease manifests as hemorrhagic inflammation with loss of the normal vascular pattern, petechial hemorrhages, and bleeding. Edema is present, and large areas become denuded of mucosa. Undermining of the mucosa leads to the formation of crypt abscesses, which are the hallmark of the disease. (See Presentation.)

The diagnosis of ulcerative colitis is best made with endoscopy and mucosal biopsy for histopathology. Laboratory studies are helpful to exclude other diagnoses and assess the patient's nutritional status, but serologic markers can assist in the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Radiographic imaging has an important role in the workup of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease and in the differentiation of ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease by demonstrating fistulae or the presence of small bowel disease seen only in Crohn disease. (See Workup.)

The initial treatment for ulcerative colitis includes mesalamine, corticosteroids, anti-inflammatory agents, antidiarrheal agents, and rehydration (see Medication). Surgery is considered if medical treatment fails or if a surgical emergency develops. (See Treatment.)

For more information, go to Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Crohn Disease.

For more Clinical Practice Guidelines, go to Guidelines.

Additional information can be found at Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA).

Anatomy

Ulcerative colitis (UC) extends proximally from the anal verge in an uninterrupted pattern to involve part or the entire colon. The rectum is involved in more than 95% of cases; some authorities believe that the rectum is always involved in untreated patients. Rectal involvement occurs even when the rest of the colon is spared.

Ulcerative colitis occasionally involves the terminal ileum, as a result of an incompetent ileocecal valve. In these cases, which may constitute as many as 10% of patients, the reflux of noxious inflammatory mediators from the colon results in superficial mucosal inflammation of the terminal ileum, called backwash ileitis. [8, 9] Up to about 30 cm of the terminal ileum may be affected.

Pathophysiology

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a diffuse, nonspecific inflammatory disease whose etiology is unknown. [10] The colonic mucosa proximal from the rectum is persistently affected, frequently involving erosions and/or ulcers, as well as involving repeated cycles of relapse and remission and potential extraintestinal manifestations. [10]

A variety of immunologic changes have been documented in ulcerative colitis. Subsets of T cells accumulate in the lamina propria of the diseased colonic segment. In patients with ulcerative colitis, these T cells are cytotoxic to the colonic epithelium. This change is accompanied by an increase in the population of B cells and plasma cells, with increased production of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin E (IgE). [11]

Anticolonic antibodies have been detected in patients with ulcerative colitis. A small proportion of patients with ulcerative colitis have antismooth muscle and anticytoskeletal antibodies.

Microscopically, acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrate of the lamina propria, crypt branching, and villous atrophy are present in ulcerative colitis. Microscopic changes also include inflammation of the crypts of Lieberkühn and abscesses. These findings are accompanied by a discharge of mucus from the goblet cells, the number of which is reduced as the disease progresses. The ulcerated areas are soon covered by granulation tissue. Excessive fibrosis is not a feature of the disease. The undermining of the mucosa and an excess of granulation tissue lead to the formation of polypoidal mucosal excrescences, which are known as inflammatory polyps or pseudopolyps.

Etiology

The exact etiology of ulcerative colitis (UC) is unknown, but certain factors have been found to be associated with the disease, and some hypotheses have been presented. Etiologic factors potentially contributing to ulcerative colitis include genetic factors, immune system reactions, environmental factors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, low levels of antioxidants, psychological stress factors, a smoking history, and consumption of milk products. Certain types of food composition and the use of oral contraceptives may be associated with this condition. [10]

Some evidence exists to indicate smoking may be protective of ulcerative colitis, but a causal association remains unclear. [10] A systematic review and meta-analysis that evaluated the association between smoking and need for surgery in patients with inflammatory bowel disease found that current smokers with Crohn disease had an increased risk of intestinal resection surgery compared to their never-smoking counterparts, whereas in patients with ulcerative colitis, current and never smokers had similar rates of colectomy. [12] However, there was an increased risk for colectomy in former smokers with ulcerative colitis.

Genetics

The current hypothesis is that genetically susceptible individuals have abnormalities of the humoral and cell-mediated immunity and/or generalized enhanced reactivity against commensal intestinal bacteria, and that this dysregulated mucosal immune response predisposes to colonic inflammation. [13]

A family history of ulcerative colitis (observed in 1 in 6 relatives) is associated with a higher risk for developing the disease. Disease concordance has been documented in monozygotic twins. [14] Genetic association studies have identified multiple loci, [10] including some that are associated with both ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease; one relatively recently identified locus is also associated with the susceptibility to colorectal cancer (CDH1). [15]

Chromosomes are thought to be less stable in patients with ulcerative colitis, as measured with telomeric associations in peripheral leukocytes. [16] This phenomenon may also contribute to the increased cancer risk. Whether these abnormalities are the cause or the result of the intense systemic inflammatory response in ulcerative colitis is unresolved.

Immune reactions

Immune reactions that compromise the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier may contribute to ulcerative colitis. Serum and mucosal autoantibodies against intestinal epithelial cells may be involved. The presence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) and anti– Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) is a well-known feature of inflammatory bowel disease. [17, 18, 19, 20, 21]

In addition, an immune modulatory abnormality has been assumed to be responsible for the lower incidence of ulcerative colitis in patients who have undergone previous appendectomy. The incidence of previous appendectomy is lower in patients with ulcerative colitis (4.5%) than in control subjects (19%), and a further protective effect is observed if the appendectomy was performed before the patient was age 20 years. [22] Also, patients in whom appendectomy was performed for inflammatory disorders (eg, appendicitis or mesenteric adenitis) seem to have a lower incidence of ulcerative colitis than patients who undergo appendectomy for other disorders such as nonspecific abdominal pain. [23]

Environmental factors

Environmental factors also play a role. For example, sulfate-reducing bacteria, which produce sulfides, are found in large numbers in patients with ulcerative colitis, and sulfide production is higher in patients with ulcerative colitis than in other people. Sulfide production is even higher in patients with active ulcerative colitis than in patients in remission. The bacterial microflora is altered in patients with active disease. [24] A decrease in Klebsiella species is seen in the ileum of patients relative to control subjects. This difference disappears after proctocolectomy.

NSAID use

NSAID use is higher in patients with ulcerative colitis than in control subjects, and one third of patients with an exacerbation of ulcerative colitis report recent NSAID use. This finding leads some clinicians to recommend avoidance of NSAID use in patients with ulcerative colitis. [25]

Other etiologic factors

Other factors that may be associated with ulcerative colitis include the following:

- Vitamins A and E, both considered antioxidants, are found in low levels in as many as 16% of children with ulcerative colitis exacerbation. [26]

- Psychological and psychosocial stress factors can play a role in the presentation of ulcerative colitis and can precipitate exacerbations. [23]

- Smoking is negatively associated with ulcerative colitis (although some evidence appears to show it having a protective effect [10] ). This relationship is reversed in Crohn disease.

- Milk consumption may exacerbate the disease.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

In the United States, about 1 million people are affected with ulcerative colitis (UC). [27, 28] The annual incidence is 10.4-12 cases per 100,000 people, and the prevalence rate is 35-100 cases per 100,000 people. Ulcerative colitis is three times more common than Crohn disease.

Ulcerative colitis occurs more frequently in white persons than in black persons or Hispanics. The incidence of ulcerative colitis is reported to be 2-4 times higher in Ashkenazi Jews. However, population studies in North America do not completely support this assertion.

Ulcerative colitis is slightly more common in women than in men. The age of onset follows a bimodal pattern, with a peak at 15-25 years and a smaller one at 55-65 years, although the disease can occur in people of any age. [29] Ulcerative colitis is uncommon in those younger than 10 years. Two of every 100,000 children are affected; however, 20%-25% of all cases of ulcerative colitis occur in persons aged 20 years or younger.

International statistics

Ulcerative colitis is more common in the Western and Northern hemispheres; the incidence is low in Asia and the Far East. [4]

In Japan, there are more than 160,000 patients with ulcerative colitis (about 27 per 100,000 people) and, unlike Western nations, a male predominance exists. [10]

Prognosis

In a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate patient-reported outcomes for rectal bleeding and stool frequency in 2132 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) in endoscopic remission, investigators noted that most of these individuals who had normal rectal bleeding and stool frequency subscores attained endoscopic remission, although many had no rectal bleeding. [30] However, despite endoscopic remission, many patients had abnormal stool frequencies.

Ulcerative colitis may result in disease-related mortality. However, overall mortality is not increased in patients with ulcerative colitis, as compared to the general population. An increase in mortality may be observed among elderly patients with the disease. Mortality is also increased in patients who develop complications (eg, shock, malnutrition, anemia). Evidence suggests that mortality is increased in patients with ulcerative colitis who undergo any form of medical or surgical intervention.

Involvement of the muscularis propria in the most severe cases can lead to damage to the nerve plexus, resulting in colonic dysmotility, dilatation, and eventual infarction and gangrene. This condition is termed toxic megacolon and is characterized by a thin-walled, large, dilated colon that may eventually become perforated. Chronic ulcerative colitis is associated with pseudopolyp formation in about 15%-20% of cases. Chronic and severe cases can be associated with areas of precancerous changes, such as carcinoma in situ or dysplasia.

The most common cause of death of patients with ulcerative colitis is toxic megacolon. Colonic adenocarcinoma develops in 3%-5% of patients with ulcerative colitis, and the risk increases as the duration of disease increases. Patients with extensive ulcerative colitis over a long period have a significantly increased risk of colorectal cancer. [10] The risk of colonic malignancy is higher in cases of pancolitis and in cases in which disease onset occurs before age 15 years. Benign stricture rarely causes intestinal obstruction.

- Murata I, Satoh K, Yoshikawa I, Masumoto A, Sasaki E, Otsuki M. Recurrent subcutaneous abscess of the sternal region in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999 Mar. 94(3):844-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kimura K, Hunter SF, Thollander MS, et al. Concurrence of inflammatory bowel disease and multiple sclerosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000 Aug. 75(8):802-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Egan CA, Meadows KP, Zone JJ. Ulcerative colitis and immunobullous disease cured by colectomy. Arch Dermatol. 1999 Feb. 135(2):214-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Bernstein CN, Eliakim A, Fedail S, et al. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guidelines: inflammatory bowel disease: update August 2015. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016 Nov/Dec. 50(10):803-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Esteve M, Gisbert JP. Severe ulcerative colitis: at what point should we define resistance to steroids?. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 Sep 28. 14(36):5504-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Shen B. Crohn's disease of the ileal pouch: reality, diagnosis, and management. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009 Feb. 15(2):284-94. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P. Treatment of severe steroid refractory ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 Sep 28. 14(36):5508-11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Heuschen UA, Hinz U, Allemeyer EH, et al. Backwash ileitis is strongly associated with colorectal carcinoma in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001 Mar. 120(4):841-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kaufman SS, Vanderhoof JA, Young R, Perry D, Raynor SC, Mack DR. Gastroenteric inflammation in children with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997 Jul. 92(7):1209-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Matsuoka K, Kobayashi T, Ueno F, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2018 Mar. 53(3):305-53. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Himmel ME, Hardenberg G, Piccirillo CA, Steiner TS, Levings MK. The role of T-regulatory cells and Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of human inflammatory bowel disease. Immunology. 2008 Oct. 125(2):145-53. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kuenzig ME, Lee SM, Eksteen B, et al. Smoking influences the need for surgery in patients with the inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis incorporating disease duration. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016 Dec 21. 16(1):143. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007 Jul 26. 448(7152):427-34. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lindberg E, Magnusson KE, Tysk C, Jarnerot G. Antibody (IgG, IgA, and IgM) to baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), yeast mannan, gliadin, ovalbumin and betalactoglobulin in monozygotic twins with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1992 Jul. 33(7):909-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Barrett JC, Lee JC, Lees CW, et al. Genome-wide association study of ulcerative colitis identifies three new susceptibility loci, including the HNF4A region. Nat Genet. 2009 Dec. 41(12):1330-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Vasiliauskas E. Serum immune markers in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology and Endoscopy News. Available at https://www.gastroendonews.com. October 1997;

- Peeters M, Joossens S, Vermeire S, Vlietinck R, Bossuyt X, Rutgeerts P. Diagnostic value of anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae and antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Mar. 96(3):730-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Dubinsky MC, Ofman JJ, Urman M, Targan SR, Seidman EG. Clinical utility of serodiagnostic testing in suspected pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Mar. 96(3):758-65. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hoffenberg EJ, Fidanza S, Sauaia A. Serologic testing for inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr. 1999 Apr. 134(4):447-52. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kaditis AG, Perrault J, Sandborn WJ, Landers CJ, Zinsmeister AR, Targan SR. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody subtypes in children and adolescents after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998 Apr. 26(4):386-92. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Duggan AE, Usmani I, Neal KR, Logan RF. Appendicectomy, childhood hygiene, Helicobacter pylori status, and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a case control study. Gut. 1998 Oct. 43(4):494-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Andersson RE, Olaison G, Tysk C, Ekbom A. Appendectomy and protection against ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2001 Mar 15. 344(11):808-14. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, et al. Stress and exacerbation in ulcerative colitis: a prospective study of patients enrolled in remission. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 May. 95(5):1213-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Almeida MG, Kiss DR, Zilberstein B, Quintanilha AG, Teixeira MG, Habr-Gama A. Intestinal mucosa-associated microflora in ulcerative colitis patients before and after restorative proctocolectomy with an ileoanal pouch. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008 Jul. 51(7):1113-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Felder JB, Korelitz BI, Rajapakse R, Schwarz S, Horatagis AP, Gleim G. Effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Aug. 95(8):1949-54. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bousvaros A, Zurakowski D, Duggan C, et al. Vitamins A and E serum levels in children and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease: effect of disease activity. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998 Feb. 26(2):129-35. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Garland CF, Lilienfeld AM, Mendeloff AI, Markowitz JA, Terrell KB, Garland FC. Incidence rates of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease in fifteen areas of the United States. Gastroenterology. 1981 Dec. 81(6):1115-24. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cotran RS, Collins T, Robbins SL, Kumar V. Pathologic Basis of Disease. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders; 1998.

- Jang ES, Lee DH, Kim J, et al. Age as a clinical predictor of relapse after induction therapy in ulcerative colitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009 Sep-Oct. 56(94-95):1304-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Narula N, Alshahrani AA, Yuan Y, Reinisch W, Colombel JF. Patient-reported outcomes and endoscopic appearance of ulcerative colitis-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Feb. 17(3):411-418.e3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Kornbluth A, Sachar DB. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College Of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Mar. 105(3):501-23; quiz 524. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gooding IR, Springall R, Talbot IC, Silk DB. Idiopathic small-intestinal inflammation after colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Jun. 6(6):707-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Slatter C, Girgis S, Huynh H, El-Matary W. Pre-pouch ileitis after colectomy in paediatric ulcerative colitis. Acta Paediatr. 2008 Mar. 97(3):381-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Falcone RA Jr, Lewis LG, Warner BW. Predicting the need for colectomy in pediatric patients with ulcerative colitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000 Mar-Apr. 4(2):201-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, et al. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994 Jun 30. 330(26):1841-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rowe FA, Walker JH, Karp LC, Vasiliauskas EA, Plevy SE, Targan SR. Factors predictive of response to cyclosporin treatment for severe, steroid-resistant ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Aug. 95(8):2000-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Yu N. The prevalence of extraintestinal diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Apr. 96(4):1116-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- de Vlam K, Mielants H, Cuvelier C, De Keyser F, Veys EM, De Vos M. Spondyloarthropathy is underestimated in inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and HLA association. J Rheumatol. 2000 Dec. 27(12):2860-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cox KL, Cox KM. Oral vancomycin: treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis in children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998 Nov. 27(5):580-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Marchesa P, Lashner BA, Lavery IC, et al. The risk of cancer and dysplasia among ulcerative colitis patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997 Aug. 92(8):1285-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kim B, Barnett JL, Kleer CG, Appelman HD. Endoscopic and histological patchiness in treated ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999 Nov. 94(11):3258-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Calabrese C, Fabbri A, Gionchetti P, et al. Controlled study using wireless capsule endoscopy for the evaluation of the small intestine in chronic refractory pouchitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Jun 1. 25(11):1311-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bernstein CN, Fried M, Krabshuis JH, et al. World Gastroenterology Organization Practice Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of IBD in 2010. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010 Jan. 16(1):112-24. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- McNamara D. New IBD guidelines aim to simplify care. Medscape Medical News. February 20, 2018. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/892853. Accessed: June 6, 2018.

- Carucci LR, Levine MS. Radiographic imaging of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002 Mar. 31(1):93-117, ix. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Eisenberg RL. Gastrointestinal Radiology: A Pattern Approach. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. 602-8.

- Wiesner W, Steinbrich W. [Imaging diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease]. Ther Umsch. 2003 Mar. 60(3):137-44. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- van den Broek FJ, Fockens P, Dekker E. Review article: New developments in colonic imaging. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Dec. 26 Suppl 2:91-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Deutsch DE, Olson AD. Colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy as the initial evaluation of pediatric patients with colitis: a survey of physician behavior and a cost analysis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997 Jul. 25(1):26-31. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Matsumoto T, Nakamura S, Jin-No Y, et al. Role of granuloma in the immunopathogenesis of Crohn's disease. Digestion. 2001. 63 Suppl 1:43-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Basson MD, Etter L, Panzini LA. Rates of colonoscopic perforation in current practice. Gastroenterology. 1998 May. 114(5):1115. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Polter DE. Risk of colon perforation during colonoscopy at Baylor University Medical Center. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2015 Jan. 28(1):3-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Makkar R, Bo S. Colonoscopic perforation in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2013 Sep. 9(9):573-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Shergill AK, Lightdale JR, Bruining DH, et al, for the Standards of Practice Committee. The role of endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 May. 81(5):1101-21.e1-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Boal Carvalho P, Cotter J. Mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis: a comprehensive review. Drugs. 2017 Feb. 77(2):159-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ford AC, Achkar JP, Khan KJ, et al. Efficacy of 5-aminosalicylates in ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr. 106(4):601-16. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lichtenstein GR, Ramsey D, Rubin DT. Randomised clinical trial: delayed-release oral mesalazine 4.8 g/day vs. 2.4 g/day in endoscopic mucosal healing--ASCEND I and II combined analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Mar. 33(6):672-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Dallaire C, et al. Delayed-release oral mesalamine 4.8 g/day (800 mg tablets) compared to 2.4 g/day (400 mg tablets) for the treatment of mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis: The ASCEND I trial. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007 Dec. 21(12):827-34. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sandborn WJ, Regula J, Feagan BG, et al. Delayed-release oral mesalamine 4.8 g/day (800-mg tablet) is effective for patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2009 Dec. 137(6):1934-43.e1-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ford AC, Khan KJ, Sandborn WJ, Kane SV, Moayyedi P. Once-daily dosing vs. conventional dosing schedule of mesalamine and relapse of quiescent ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Dec. 106(12):2070-7; quiz 2078. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- D'Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Barrett K, Hodgson I, Streck P. Once-daily MMX(®) mesalamine for endoscopic maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Jul. 107(7):1064-77. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Barber J Jr. FDA approves Uceris for ulcerative colitis. Medscape Medical News. Jan 18, 2013. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/777917. Accessed: January 28, 2013.

- Sandborn WJ, Danese S, D'Haens G, et al. Induction of clinical and colonoscopic remission of mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis with budesonide MMX 9 mg: pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Mar. 41(5):409-18. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Uceris (budesonide) rectal foam [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ 08807: Distributed by Salix Pharmaceuticals (a division of Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC). Rev September 2016. Available at [Full Text].

- Ford AC, Bernstein CN, Khan KJ, et al. Glucocorticosteroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr. 106(4):590-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, et al. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr. 106(4):644-59, quiz 660. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Singh S, George J, Boland BS, Vande Casteele N, Sandborn WJ. Primary non-response to tumor necrosis factor antagonists is associated with inferior response to second-line biologics in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2018 May 25. 12(6):635-43. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, et al. Colectomy rate comparison after treatment of ulcerative colitis with placebo or infliximab. Gastroenterology. 2009 Oct. 137(4):1250-60; quiz 1520. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hindryckx P, Novak G, Vande Casteele N, et al. Review article: dose optimisation of infliximab for acute severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017 Mar. 45(5):617-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kevans D, Murthy S, Mould DR, Silverberg MS. Accelerated clearance of infliximab is associated with treatment failure in patients with corticosteroid-refractory acute ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2018 May 25. 12(6):662-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Hommes DW, et al. Adalimumab for induction of clinical remission in moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results of a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2011 Jun. 60(6):780-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012 Feb. 142(2):257-65.e1-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano CW, et al. A phase 2/3 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of subcutaneous golimumab induction therapy in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC): Pursuit SC [abstract #943d]. Presented at: Digestive Disease Week; San Diego, California; May 21, 2012.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new treatment for moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis [news release]. Available at https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm609225.htm. May 30, 2018; Accessed: May 31, 2018.

- Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, et al, for the OCTAVE Induction 1, OCTAVE Induction 2, et al. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017 May 4. 376(18):1723-36. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Eli Lilly and Company. FDA approves Lilly's Omvoh (mirikizumab-mrkz), a first-in-class treatment for adults with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. Available at https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/fda-approves-lillys-omvohtm-mirikizumab-mrkz-first-class. October 26, 2023; Accessed: October 31, 2023.

- D'Haens G, Dubinsky M, Kobayashi T, and the, LUCENT Study Group. Mirikizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2023 Jun 29. 388 (26):2444-55. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, et al, for the UNIFI Study Group. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 26. 381(13):1201-14. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Bristol Myers Squibb. Bristol Myers Squibb receives European Commission approval of Zeposia (ozanimod) for use in adults with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis [press release]. Available at https://news.bms.com/news/corporate-financial/2021/Bristol-Myers-Squibb-Receives-European-Commission-Approval-of-Zeposia-ozanimod-for-use-in-Adults-with-Moderately-to-Severely-Active-Ulcerative-Colitis/default.aspx#. November 23, 2021; Accessed: November 28, 2021.

- Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, D'Haens G, and the True North Study Group. Ozanimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2021 Sep 30. 385 (14):1280-91. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 22. 369(8):699-710. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Leblanc S, Allez M, Seksik P, et al. Successive treatment with cyclosporine and infliximab in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr. 106(4):771-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Khan KJ, Ullman TA, Ford AC, et al. Antibiotic therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr. 106(4):661-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sakuraba A, Sato T, Naganuma M, et al. A pilot open-labeled prospective randomized study between weekly and intensive treatment of granulocyte and monocyte adsorption apheresis for active ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2008. 43(1):51-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Miki C, Okita Y, Yoshiyama S, Araki T, Uchida K, Kusunoki M. Early postoperative application of extracorporeal leukocyte apheresis in ulcerative colitis patients: results of a pilot trial to prevent postoperative septic complications. J Gastroenterol. 2007 Jun. 42(6):508-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Emmrich J, Petermann S, Nowak D, et al. Leukocytapheresis (LCAP) in the management of chronic active ulcerative colitis--results of a randomized pilot trial. Dig Dis Sci. 2007 Sep. 52(9):2044-53. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ruuska T, Lahdeaho ML, Sutas Y, Ashorn M, Gronlund J. Leucocyte apheresis in the treatment of paediatric ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007 Nov. 42(11):1390-1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Domenech E, Panes J, Hinojosa J, et al, for the ATTICA Study Group by the Grupo Espanol de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa. Addition of granulocyte/monocyte apheresis to oral prednisone for steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis: a randomized multicentre clinical trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2018 May 25. 12(6):687-94. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zittan E, Ma GW, Wong-Chong N, et al. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis: a Canadian institution's experience. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017 Feb. 32(2):281-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sandborn WJ, Vermeire S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Etrasimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis (ELEVATE): two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies. Lancet. 2023 Apr 8. 401 (10383):1159-71. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Pfizer Inc. U.S. FDA approves Pfizer’s VELSIPITY for adults with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC). October 13, 2023. Available at https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/us-fda-approves-pfizers-velsipitytm-adults-moderately.

- Sandborn WJ, et al. A phase III randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of subcutaneous golimumab maintenance therapy in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: PURSUIT-Maintenance. Presented at the American College of Gastroenterology, October 22, 2012 Las Vegas, NV.

- Sandborn WJ, Travis S, Moro L, et al. Once-daily budesonide MMX® extended-release tablets induce remission in patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis: results from the CORE I study. Gastroenterology. 2012 Nov. 143(5):1218-26.e1-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rembacken BJ, Snelling AM, Hawkey PM, Chalmers DM, Axon AT. Non-pathogenic Escherichia coli versus mesalazine for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999 Aug 21. 354(9179):635-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tsuda Y, Yoshimatsu Y, Aoki H, et al. Clinical effectiveness of probiotics therapy (BIO-THREE) in patients with ulcerative colitis refractory to conventional therapy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007 Nov. 42(11):1306-11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Simchuk EJ, Thirlby RC. Risk factors and true incidence of pouchitis in patients after ileal pouch-anal anastomoses. World J Surg. 2000 Jul. 24(7):851-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Farouk R, Dozois RR, Pemberton JH, Larson D. Incidence and subsequent impact of pelvic abscess after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998 Oct. 41(10):1239-43. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Shamberger RC, Hergrueter CA, Lillehei CW. Use of a gracilis muscle flap to facilitate delayed ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000 Nov. 43(11):1628-31. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Karlbom U, Raab Y, Ejerblad S, Graf W, Thorn M, Pahlman L. Factors influencing the functional outcome of restorative proctocolectomy in ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg. 2000 Oct. 87(10):1401-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Meagher AP, Farouk R, Dozois RR, Kelly KA, Pemberton JH. J ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis: complications and long-term outcome in 1310 patients. Br J Surg. 1998 Jun. 85(6):800-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ogilvie JW Jr, Goetz L, Baxter NN, Park J, Minami S, Madoff RD. Female sexual dysfunction after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Br J Surg. 2008 Jul. 95(7):887-92. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cornish JA, Tan E, Teare J, et al. The effect of restorative proctocolectomy on sexual function, urinary function, fertility, pregnancy and delivery: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007 Aug. 50(8):1128-38. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Shen BO, Jiang ZD, Fazio VW, et al. Clostridium difficile infection in patients with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Jul. 6(7):782-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Falk A, Olsson C, Ahrne S, Molin G, Adawi D, Jeppsson B. Ileal pelvic pouch microbiota from two former ulcerative colitis patients, analysed by DNA-based methods, were unstable over time and showed the presence of Clostridium perfringens. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007 Aug. 42(8):973-85. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chia CS, Chew MH, Chau YP, Eu KW, Ho KS. Adenocarcinoma of the anal transitional zone after double stapled ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2008 Jul. 10(6):621-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Arias MT, Vande Casteele N, Vermeire S, et al. A panel to predict long-term outcome of infliximab therapy for patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Mar. 13(3):531-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sarigol S, Wyllie R, Gramlich T, et al. Incidence of dysplasia in pelvic pouches in pediatric patients after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999 Apr. 28(4):429-34. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pekow JR, Hetzel JT, Rothe JA, et al. Outcome after surveillance of low-grade and indefinite dysplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010 Aug. 16(8):1352-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Farraye FA, Melmed GY, Lichtenstein GR, Kane SV. ACG clinical guideline: preventive care in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Feb. 112(2):241-58. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Raine T, Bonovas S, Burisch J, et al. ECCO Guidelines on therapeutics in ulcerative colitis: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2022 Jan 28. 16 (1):2-17. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Spinelli A, Bonovas S, Burisch J, et al. ECCO Guidelines on therapeutics in ulcerative colitis: surgical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2022 Feb 23. 16 (2):179-89. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Holubar SD, Lightner AL, Poylin V, et al, on behalf of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical practice guidelines for the surgical management of ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2021 Jul 1. 64(7):783-804. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] De Simone B, Davies J, Chouillard E, et al. WSES-AAST guidelines: management of inflammatory bowel disease in the emergency setting. World J Emerg Surg. 2021 May 11. 16(1):23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Kucharzik T, Ellul P, Greuter T, et al. ECCO guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and management of infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021 Jun 22. 15(6):879-913. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Feuerstein JD, Isaacs KL, Schneider Y, et al, for the AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020 Apr. 158(5):1450-61. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Ko CW, Singh S, Feuerstein JD, et al, for the American Gastroenterological Association Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2019 Feb. 156(3):748-64. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, Sauer BG, Long MD. ACG clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019 Mar. 114(3):384-413. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Swift D. Updated UC guideline adds mucosal healing to treatment goal. Medscape Medical News. March 4, 2019. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/909801. Accessed: March 20, 2019.

- [Guideline] Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019 Dec. 68(Suppl 3):s1-s106. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- American Gastroenterological Association. New guideline provides recommendations for the treatment of mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. January 9, 2019. Available at https://www.gastro.org/press-release/new-guideline-provides-recommendations-for-the-treatment-of-mild-to-moderate-ulcerative-colitis. Accessed: March 20, 2019.

- Parente F, Molteni M, Marino B, et al. Are colonoscopy and bowel ultrasound useful for assessing response to short-term therapy and predicting disease outcome of moderate-to-severe forms of ulcerative colitis?: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 May. 105(5):1150-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Moran CP, Neary B, Doherty GA. Endoscopic evaluation in diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Dec 16. 8(20):723-32. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Andersson T, Lunde OC, Johnson E, Moum T, Nesbakken A. Long-term functional outcome and quality of life after restorative proctocolectomy with ileo-anal anastomosis for colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2011 Apr. 13(4):431-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Brooks M. FDA approves new indication for Simponi. Medscape Medical News. May 15, 2013. [Full Text].

- Charron M, del Rosario JF, Kocoshis S. Use of technetium-tagged white blood cells in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: is differential diagnosis possible?. Pediatr Radiol. 1998 Nov. 28(11):871-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Choi JS, Potenti F, Wexner SD, et al. Functional outcomes in patients with mucosal ulcerative colitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis by the double stapling technique: is there a relation to tissue type?. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000 Oct. 43(10):1398-404. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cottliar A, Fundia A, Boerr L, et al. High frequencies of telomeric associations, chromosome aberrations, and sister chromatid exchanges in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Sep. 95(9):2301-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cucchiara S, Celentano L, de Magistris TM, Montisci A, Iula VD, Fecarotta S. Colonoscopy and technetium-99m white cell scan in children with suspected inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr. 1999 Dec. 135(6):727-32. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- da Luz Moreira A, Kiran RP, Lavery I. Clinical outcomes of ileorectal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg. 2010 Jan. 97(1):65-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Durno C, Sherman P, Harris K, et al. Outcome after ileoanal anastomosis in pediatric patients with ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998 Nov. 27(5):501-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1990 Nov 1. 323(18):1228-33. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fonkalsrud EW, Bustorff-Silva J. Reconstruction for chronic dysfunction of ileoanal pouches. Ann Surg. 1999 Feb. 229(2):197-204. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Fonkalsrud EW, Thakur A, Roof L. Comparison of loop versus end ileostomy for fecal diversion after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2000 Apr. 190(4):418-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gorfine SR, Bauer JJ, Harris MT, Kreel I. Dysplasia complicating chronic ulcerative colitis: is immediate colectomy warranted?. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000 Nov. 43(11):1575-81. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hunt LE, Eichenberger MR, Petras R, Galandiuk S. Use of a microsatellite marker in predicting dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Arch Surg. 2000 May. 135(5):582-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Metcalf DR, Nivatvongs S, Sullivan TM, Suwanthanma W. A technique of extending small-bowel mesentery for ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008 Mar. 51(3):363-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Wilkinson KH, et al. Thirty-year analysis of a colonoscopic surveillance program for neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2006 Apr. 130(4):1030-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Shamberger RC, Masek BJ, Leichtner AM, Winter HS, Lillehei CW. Quality-of-life assessment after ileoanal pull-through for ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis. J Pediatr Surg. 1999 Jan. 34(1):163-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Treem WR, Cohen J, Davis PM, Justinich CJ, Hyams JS. Cyclosporine for the treatment of fulminant ulcerative colitis in children. Immediate response, long-term results, and impact on surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995 May. 38(5):474-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bezzio C, Festa S, Saibeni S, Papi C. Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: digging deep in current evidence. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Apr. 11(4):339-347. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Feuerstein JD, Nguyen GC, Kupfer SS, Falck-Ytter Y, Singh S, for the American Gastroenterological Association Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2017 Sep. 153(3):827-34. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Dharmaraj R, Dasgupta M, Simpson P, Noe J. Predictors of pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016 Dec. 63(6):e210-1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rinawi F, Assa A, Eliakim R, et al. Predictors of pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in pediatric-onset ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Sep. 29(9):1079-85. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Author

Marc D Basson, MD, PhD, MBA, FACS Senior Associate Dean for Medicine and Research, Professor of Surgery, Pathology, and Biomedical Sciences, University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Marc D Basson, MD, PhD, MBA, FACS is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American College of Surgeons, American Gastroenterological Association, Phi Beta Kappa, Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Additional Contributors

Burt Cagir, MD, FACS Associate Regional Dean and Professor of Surgery, Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine; Director, General Surgery Residency Program, Executive Director, Donald Guthrie Foundation for Research and Education, Guthrie Robert Packer Hospital; Medical Director, Guthrie/RPH Skills and Simulation Lab; Associate in Surgery, Guthrie Robert Packer Hospital and Corning Hospital

Burt Cagir, MD, FACS is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons, Association of Program Directors in Surgery, Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Michael A Grosso, MD Consulting Staff, Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, St Francis Hospital

Michael A Grosso, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society of University Surgeons

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Alex Jacocks, MD Program Director, Professor, Department of Surgery, University of Oklahoma School of Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Tri H Le, MD Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Penn State Milton S Hershey Medical Center

Tri H Le, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association, American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and Crohns and Colitis Foundation of America

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Luis M Lovato, MD Associate Clinical Professor, University of California, Los Angeles, David Geffen School of Medicine; Director of Critical Care, Department of Emergency Medicine, Olive View-UCLA Medical Center

Luis M Lovato, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Anil Minocha, MD, FACP, FACG, AGAF, CPNSS Professor of Medicine, Director of Digestive Diseases, Medical Director of Nutrition Support, Medical Director of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Internal Medicine Department, University of Mississippi Medical Center; Clinical Professor, University of Mississippi School of Pharmacy

Anil Minocha, MD, FACP, FACG, AGAF, CPNSS is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Clinical Toxicology, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Forensic Examiners, American College of Gastroenterology, American College of Physicians, American Federation for Clinical Research, American Gastroenterological Association, and American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Medscape Salary Employment

Noel Williams, MD Professor Emeritus, Department of Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada; Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Noel Williams, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.