Structure-function relationships in the IL-17 receptor: Implications for signal transduction and therapy (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2009 Apr 8.

Abstract

IL-17 is the defining cytokine of a newly-described “Th17” population that plays critical roles in mediating inflammation and autoimmunity. The IL-17/IL-17 receptor superfamily is the most recent class of cytokines and receptors to be described, and until recently very little was known about its function or molecular biology. However, in the last year important new insights into the composition and dynamics of the receptor complex and mechanisms of downstream signal transduction have been made, which will be reviewed here.

1. Introduction: A unique subset of Th cells produce IL-17

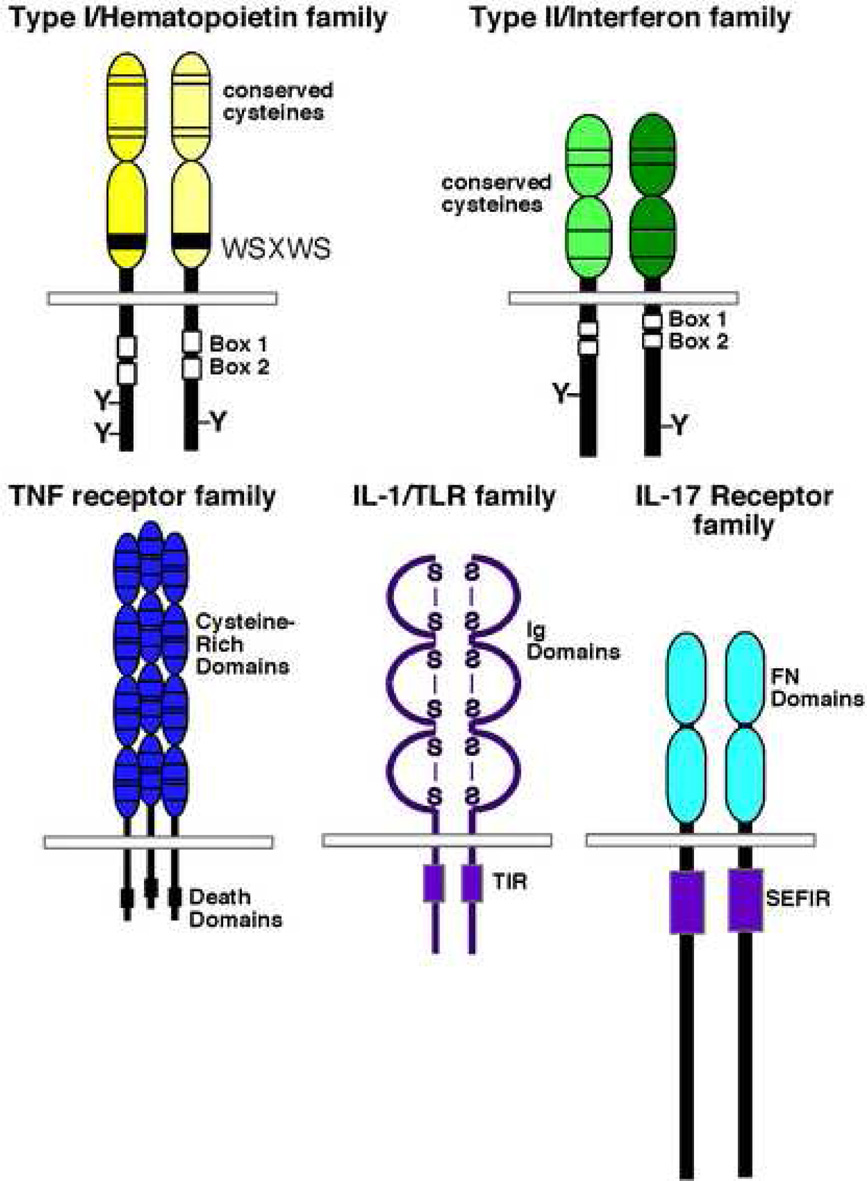

Cytokines coordinate nearly all immune functions, as well as many other processes such as bone remodeling, mammary gland development and nervous system function. A cytokine’s function is determined by its cognate receptor’s molecular signals, and receptor structure is, generally speaking, predictive of signaling function. For this reason, cytokines have been divided into a limited number of families based primarily on structural features of their receptors [1]. The newest grouping to be described is the IL-17 superfamily [2, 3] (Figure 1, Table 1). Members of the IL-17 and IL-17 receptor families share strikingly little sequence homology to other cytokine classes. Thus, few predictions about signaling or function could be made based simply on primary amino acid sequence. Although IL-17 has been recognized for almost 15 years, only recently have we begun to unravel elements of IL-17 receptor structure and function, which is the basis of this review.

Figure 1. Cytokine receptor superfamilies.

The five major subgroups of cytokine receptors are depicted, including the Type I hematopoietin receptors, Type II interferon receptors, TNF receptors, IL-1/Toll-like receptors and the IL-17 receptor family. Major conserved sequence elements are included. Box1 and Box2 are JAK-binding domains. “TIR” is the Toll-like receptor/IL-1 receptor interacting domain, and SEFIR is the SEF/IL-17 receptor domain. See Section 1 in the text for details.

Table 1. IL-17 and IL-17 receptor superfamily.

Currently accepted nomenclature for IL-17 ligands and receptors. Chromosomal locations are for human genes. [50, 53].

| Ligand | Chromosome | Receptor(s) | Receptor | Chromosome | Ligand(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-17A | 6p12 | IL-17RA, IL-17RC | IL-17RA | 22q11.1 | IL-17A, F, A/F |

| IL-17A/F | 6p12 | IL-17RA, IL-17RC | IL-17RB | 3p21.1 | IL-17B, E |

| IL-17B | 5q32–34 | IL-17RB | IL-17RC | 3p25.3 | IL-17A, F, A/F |

| IL-17C | 16g24 | ND‡ | IL-17RD/SEF*** | 3p21.2 | FGFR? |

| IL-17D | 13q12.11 | ND | IL-17RE | 3p25.3 | ND |

| IL-17E/IL-25 | 14q11.2 | IL-17RB | |||

| IL-17F | 6p12 | IL-17RA, IL-17RC | |||

| vIL-17 | H. Saimiri** | IL-17RA |

In 2005, IL-17 came into prominence with the seminal discovery that it is the hallmark of a new T helper cell population, now termed “Th17.” It was long known that IL-17 is produced almost exclusively by T cells, especially the CD4+ effector memory phenotype [4]. IL-17 is also produced by CD8+ T cells and γδ T cells, which probably contribute significantly to the pool of IL-17, particularly at mucosal sites [5–7]. Expression of IL-17 did not fall obviously into either the Th1 or Th2 categories [8, 9], an observation that was initially overlooked. However, the finding that IL-23 drives expression of IL-17 in CD4+ T cells [10, 11] coupled with the distinct functional roles of IL-12 and IL-23 (which share a common p40 subunit) [12–16] rapidly led to the realization that many functions formerly attributed to Th1 cells are in fact mediated by a distinct, IL-17-producing T cell subset [15]. Much work has elegantly demonstrated that Th17 cells arise as a distinct subpopulation, driven by IL-6, TGFβ, IL-21 and perhaps IL-1β and expanded by IL-23 through exclusive IL-23R expression on Th17 cells [17–24]. In addition to IL-17, Th17 cells produce IL-17F, IL-22, IL-26, TNFα and various chemokines [25–27], which act in concert to mediate the pro-inflammatory effects of this population. It is now clear that Th17 cells are essential mediators of pathology in numerous autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), multiple sclerosis (MS), Crohn’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), among others. Conversely, IL-17 contributes in a nonredundant manner to defense against various infectious organisms, primarily through its actions on neutrophil expansion and homeostasis [28–30]. While much remains to be learned about differentiation Th17 cells and the effects of Th17-derived cytokines, the IL-17 family is emerging as a key player in shaping immune responses.

2. The IL-17 and IL-17R superfamily

Six IL-17-family ligands in mammalian cells and one virally-encoded ligand have been described, and five related receptors have been identified (Table 1). The best characterized ligand is IL-17 (CTLA-8, IL-17A) [31]. IL-17F is the most closely-related protein, with ~60% homology to IL-17 [32]. Although distinct in primary sequence, IL-17F was found to be structurally similar to cysteine knot cytokines such as PDGF and NGF, and models of IL-17 indicate it adopts a similar 3-dimensional conformation [33]. Both IL-17 and IL-17F form homodimers [4], but the activities of IL-17 are consistently found to be at least 10-fold more potent than IL-17F. Recent findings indicate that IL-17 and IL-17F also form heterodimers with intermediate signaling potency [34, 35]. In fact, the IL-17A/F heterodimer may be the dominant form of this cytokine in vivo, as IL-17F mRNA is overexpressed relative to IL-17 in CD4+ T cells, and the IL-17A homodimer is found at very low levels in human donors [34, 36]. Far less is known about the functions of other IL-17 family cytokines, although several studies show that IL-17E/IL-25 promotes Th2-mediated immunity, particularly in airway inflammation [37–43]. More details of the discovery and functions of the extended IL-17 family can be found in Refs. [19, 44].

3. Anti-cytokine therapy and the IL-17R complex

Antibodies and soluble decoy cytokine receptors are currently used to treat RA, Crohn’s disease and other inflammatory conditions [45]. Inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL-β and IL-6 are the major targets of current anti-cytokine therapies. However, none of these drugs are successful in all patients [45, 46]. The pathogenic role of IL-17 in autoimmunity and its functional similarities to TNFα and IL-1β makes this cytokine/receptor system an attractive drug target [47], but little is currently known about the composition or molecular dynamics of the IL-17R complex.

The first IL-17 receptor family member, IL-17RA, was reported in 1995 and was notably lacking in detectable homology to other known cytokine receptors [48, 49]. However, IL-17RA encodes an unusually large cytoplasmic tail and was shown to activate inflammatory events typical of innate cytokines such as TNFα and IL-1β including activation of the transcription factor NF-κB and induction of the IL-6 gene [48]. See Section 5 for further details regarding IL-17RA-mediated signal transduction.

Murine IL-17RA was found to bind mouse, human and viral IL-17 [48] and these cytokines are cross-reactive functionally. However, the binding affinity of IL-17RA for IL-17 was quite low (~4 × 107 M−1), and it was postulated that an additional subunit might cooperate with IL-17RA to create a receptor complex compatible with the low concentrations of cytokine needed to elicit biological responses [49]. Consistently, IL-17RC (IL-17RL), a poorly-characterized member of the IL-17R superfamily, was shown to be required for human IL-17-mediated signaling, and this work also identified interesting species-dependent association of these receptor subunits [50]. This finding has been confirmed in IL-17RC−/− mice (W. Ouyang, personal communication). IL-17RC exists in numerous splice forms, a phenomenon that has been mainly examined in the context of prostate cancer cells [3, 51, 52]. The significance of IL-17RC splice variation is not understood. However, a new study [53] examined binding of IL-17 and IL-17F to IL-17RA and various splice forms of IL-17RC. This report confirmed that IL-17RC is indeed a receptor for both IL-17 and IL-17F. Moreover, at least one isoform of IL-17RC binds more strongly to IL-17F than to IL-17RA, and species-dependent ligand binding was also observed. The distinct tissue distribution of IL-17RC compared to IL-17RA and its capacity for splice variation in the extracellular domain [51] hints that it may have other functions and/or ligands, which will certainly be developed further in the near future.

4. Structural features of the IL-17RA extracellular domain: receptor pre-assembly

All known cytokine receptors are multimeric, and oligomerization of receptor subunits is essential for activating signal transduction. For many years the paradigm for cytokine receptor signaling was that individual subunits exist as monomers in the plasma membrane, and ligand causes receptor subunits to oligomerize and thereby initiate signaling by bringing appropriate enzymes or adaptors into proximity. However, in most situations where this has been examined closely, this model has been challenged. In fact, the majority of cytokine receptors actually exist as pre-assembled, inactive molecular complexes that undergo large conformational alterations upon interaction with ligand [54–56]. An interesting case in point is the TNF receptor superfamily, where members form pre-formed trimers. A modular subdomain has been identified that directs receptor subunit pre-assembly, termed a “pre-ligand assembly domain” (PLAD) [57–59]. The PLAD has been found in nearly all TNF receptors, and serves to prevent assembly of non-productive heteromeric complexes. In humans, an intact PLAD in Fas/CD95 is required for mutants that cause an autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome to enable creation of mixed receptor complexes between wild type and mutant Fas subunits [60]. Intriguingly, this strategy has been exploited by poxviruses, which encode a TNFR inhibitor that also contains a “vPLAD” essential for its inhibitory function [61]. The discovery of pre-assembled receptors has led to a novel approach for developing cytokine-targeting agents, in that a soluble TNFR PLAD domain can block TNFα-mediated arthritis in vivo as effectively as existing drugs such as Enbrel/etanercept, a soluble TNFR fused to human Fc [62].

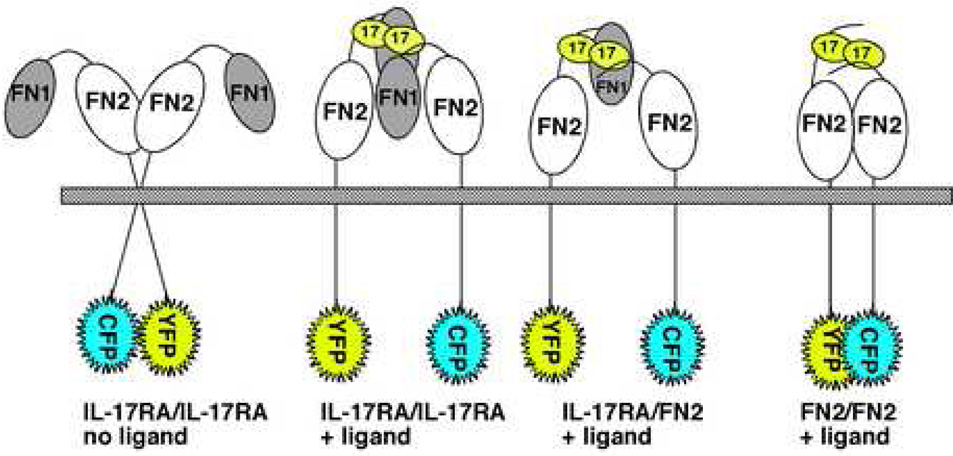

Until recently, nothing was known about IL-17 receptor composition, or even whether this receptor functioned as a multimer. To answer this question, our group fused the cytoplasmic tail of IL-17RA to the CFP and YFP fluorophores and used fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) microscopy to demonstrate that IL-17RA indeed forms a pre-assembled complex in the plasma membrane [63] (Figure 2). These findings did not rule out the involvement of additional subunits in the complex such as IL-17RC, nor do they indicate the stoichiometry of the complex with respect to IL-17RA subunits. However, this study did suggest that IL-17RA subunits are at minimum homodimeric, presumably “poised” for rapid signal transduction upon stimulation with ligand. Unexpectedly, unlike the TNFR, TLR9 or EPO receptors [54, 55, 58], addition of IL-17 caused a reduction of FRET signal, indicating a physical separation of the cytoplasmic domains. Although the IL-17A/F heterodimer was not available for testing, IL-17F exerted a similar effect [63], suggesting that all signaling-competent ligands are likely to trigger similar conformational alterations in the receptor complex. Possible explanations for this finding include recruitment of additional receptor subunits (e.g. IL-17RC) and/or intracellular signaling molecules (e.g. Act1, see Section 5) that separate or otherwise interfere with interactions in the cytoplasmic tail. To date, it is not clear whether IL-17RC is also part of the pre-assembled receptor complex or is inducibly recruited following ligand binding. It is plausible that the receptor reconfiguration observed in FRET analyses is due to separation of the IL-17RA cytoplasmic tails in order to accommodate recruitment of IL-17RC. Conversely, for rapid signaling to occur, it would make sense for IL-17RC subunits also to be in close proximity, and the apparent separation is due to large intra-molecular movements of IL-17RA subunits. There is precedent for such large movements in various receptor systems, including the EPOR and bacterial quorum sensing receptors [55, 64, 65]. A complete understanding of IL-17R subunit dynamics will await solution of the IL-17R crystal structure.

Figure 2. Homotypic interactions between IL-17RA subunits.

The IL-17RA is predicted to contain two fibronectin III-like (FN) motifs connected by an unstructured linker, and interacts via the FN2 motif in a ligand-independent manner as shown by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) studies. CFP, cyan fluorescent protein. YFP, yellow fluorescent protein. See section 3–section 4 in the text for details.

The fact that IL-17RA subunits are pre-assembled indicates that IL-17RA has an inherent molecular feature that directs its oligomerization, analogous to the TNFR PLAD domain. However, IL-17RA bears no homology to TNF receptors, and thus its PLAD is likely to be structurally distinct. Computational modeling of the IL-17RA extracellular domain (ECD) revealed two fibronectin III-like (FN) domains (Figure 2), confirming and extending a previous report [66]. FN domains are commonly found in Type I cytokine receptors where they mediate protein-protein interactions and ligand binding [67]. Studies using yeast-two-hybrid and FRET confirmed that the membrane-proximal FN domain of IL-17RA (termed FN2) is indeed capable of dimerization [68]. Unlike the TNFR, however, where the PLAD is physically distinct from the ligand-binding domain, the FN2 domain is also essential for binding to IL-17. However, in both cases the PLAD is necessary for efficient ligand binding. Thus, the FN2 domain constitutes the IL-17RA-PLAD, and is functionally but not structurally similar to the TNFR PLAD. It will be interesting to determine whether a soluble IL-17RA-PLAD can serve to inhibit IL-17-mediated signal transduction similar to the TNFR-PLAD [62].

5. IL-17R Signal Transduction

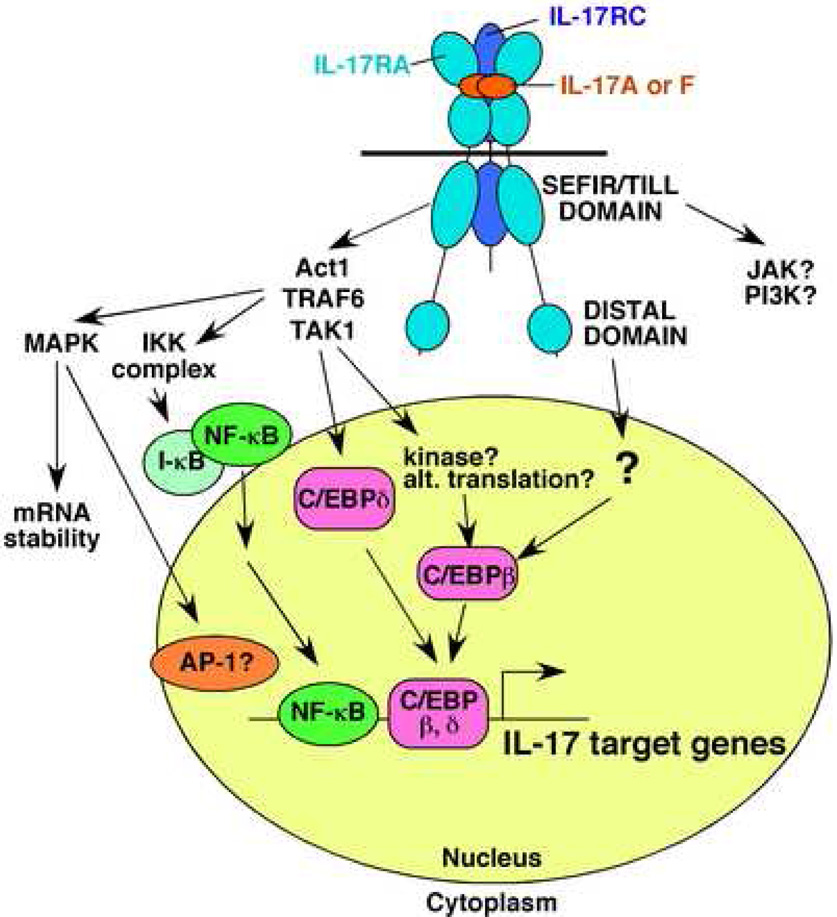

Much is now known regarding IL-17 and IL-17RA function, but our understanding of IL-17 receptor signal transduction is still surprisingly limited. As indicated, the IL-17RA bears little homology to other known cytokine receptor families [48, 69]. Since there was no obvious model based on homologous receptors, efforts were made to understand IL-17RA signal transduction from the “bottom up,” based on IL-17 target genes and their promoters. The following sections describe the major categories of IL-17 gene targets, and how the IL-17 receptor coordinates signaling to mediate gene expression (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Signal tranduction by the IL-17 receptor complex.

The IL-17R is composed of at least two IL-17RA subunit and at least one IL-17RC subunit, although the precise stoichiometry is still undefined. Binding of ligand [IL-17(A), IL-17F or IL-17A/F] triggers signaling mediated through at least two motifs in the IL-17RA tail: a SEFIR/TILL domain, which contains elements homologous to TIR domains, and a distal domain that activates C/EBPβ. The major signaling intermediates so far identified include Act1, TAK1 and TRAF6, which coordinate NF-κB and probably MAPK and C/EBP activation. Activation of these pathways leads to gene expression mediated the levels of transcription and mRNA stability. JAK1 and PI3K pathways have also been implicated, but far less is known about whether and how this occurs. See Section 5 in the text for details.

5.1 IL-17 regulates inflammatory genes through synergistic signaling

IL-6 was one of the earliest defined IL-17 gene targets and remains the standard bioassay for IL-17 activity [4, 48] (Table 2). IL-6, of course, mediates inflammation, but is also essential for Th17 development, suggesting a positive reinforcement loop induced by IL-17 signaling [70]. IL-17 activates IL-6 synergistically with other cytokines, including IL-1β, IFNγ, TNFα and most recently IL-22 [25, 71–74]. Subsequently, it was shown that many, if not all genes induced by IL-17 are regulated synergistically with other cytokines. Indeed, it has become standard practice to evaluate IL-17 and IL-17F responsiveness in concert with TNFα.

Table 2.

IL-17 gene targets by category. References are indicated.

| Gene Name | Gene description | Other Name | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemokines | |||

| CXCL1 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 | KC, Groα | [81] |

| CXCL2 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2 | MIP2, Groβ | [92] |

| CXCL5 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 | LIX | [82] |

| CXCL6 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 6 | GCP-2 | [157] |

| CXCL8 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 8 | IL-8 | [92] |

| CXCL9 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 | MIG | [90] |

| CXCL10 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 | IP10 | [90] |

| CXCL11 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 | I-TAC | [90] |

| CCL2 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 | MCP-1 | [93] |

| CCL5 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 | RANTES | [158] |

| CCL7 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 7 | MCP-3 | [123] |

| CCL11 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 11 | Eotaxin | [95] |

| CXCL12 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12 | SDF-1 | [159] |

| CCL20 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20 | MIP3α | [96] |

| Inflammation | |||

| IL6 | Interleukin 6 | IL-6 | [48] |

| IL-19 | Interleukin-19 | R. Wu, unpublished | |

| CSF2 | colony stimulating factor 2 (granulocyte-macrophage) | GM-CSF | [160] |

| CSF3 | colony stimulating factor 3 (granulocyte) | G-CSF | [4] |

| ICAM-1 | Intracellular adhesion molecule-1 | [97] | |

| PTGS2 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase | COX2 | [98] |

| NOS2 | Nitric oxide synthase 2 | iNOS | [98] |

| LCN2 | Lipocalin 2 | 24p3 | [103] |

| DEFB4 | defensin, beta 4_also known as_ human β-defensin-2 | BD2 | [96] |

| S100A7 | S100 calcium binding protein A7 | Psoriasin | [25] |

| S100A8 | S100 calcium binding protein A8 | Calgranulin A | [25] |

| S100A9 | S100 calcium binding protein A9 | Calgranulin B | [25] |

| MUC5AC | Mucin 5, subtypes A and C, tracheobronchial/gastric | [105] | |

| MUC5B | Mucin 5, subtype B, tracheobronchial | [105] | |

| EREG | epiregulin | [103] | |

| SOCS3 | Suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 | [103] | |

| Bone Metabolism | |||

| TNFSF11 | tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 11 | RANKL | [109] |

| MMP1 | Matrix metallopeptidase 1 | [115] | |

| MMP3 | Matrix metallopeptidase 3 | [118] | |

| MMP9 | Matrix metallopeptidase 9 | [121] | |

| MMP13 | Matrix metallopeptidase 13 | [119] | |

| TIMP1 | Tissue inhibitor of metallopeptidase 1 | [115] | |

| ADAMTS4 | a disintegrin-like and metalloprotease (reprolysin type) with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 4 | [120] | |

| Transcription | |||

| CEBPB | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein, beta | C/EBPβ, NF-IL-6 | [72] |

| CEBPD | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein, delta | C/EBPδ, NF-IL-6β | [72] |

| NFKBIZ | nuclear factor of kappa light gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, zeta | IκBζ, MAIL | [84, 103] |

To date, the underlying mechanism of synergy is not well understood. Considerable evidence indicates that IL-17 enhances the mRNA transcript stability of certain genes, particularly those containing AU-rich elements in the 3’ UTR, a feature typical of many cytokine and chemokine genes [75]. For example, IL-17 together with TNFα stabilizes IL-6 mRNA [71, 76–78]. Similarly, IL-17 serves to enhance mRNA stability of transcripts encoding G-CSF [79], GM-CSF [80], CXCL1/KC/Groα [81], CXCL5/LIX [82, 83], IL-8 [77], IκBζ [84] and COX-2 [85, 86]. Considerable data implicate MAPK pathways in mRNA stabilization effects. In particular, extracellular signal-related kinase p42/44 (ERK) and p38 MAPK are inducibly phosphorylated following IL-17 stimulation, and specific inhibitors to ERK and p38 MAPK reverse enhancement of mRNA stability [76, 85, 87]. However, other mechanisms are also likely to be involved. For example, TNFα and IL-17 additively activate the IL-6 promoter [72]. This regulation does not occur via NF-κB, but the transcription factors C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ are induced by IL-17 and TNFα, and overexpression of either can substitute for the cooperative IL-17 signal [72]. Finally, it is interesting to note that, while IL-17 exhibits potent synergy with TNFα and in some cases IL-1β, it only cooperates additively with TLR ligands such as LPS, indicating a fundamental mechanistic difference among these ligands’ modes of action [82].

In addition to IL-6, a major group of IL-17 target genes are chemokines, particularly neutrophil-attracting CXC chemokines (Table 2) [77, 81, 82, 88–90], which to a large extent underlies the potent effects of IL-17 on the neutrophil axis in vivo [91, 92]. In addition, some CC chemokines are also targets of IL-17, including CCL2/MCP-1 [76, 93, 94], CCL11/eotaxin [95] and CCL20 [96]. ICAM-1, required for effective neutrophil recruitment to inflamed sites, is also induced by IL-17 [97]. Therefore, IL-17 plays a key role in immune cell movement and recruitment during an inflammatory response.

IL-17 activates many other inflammatory mediators. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is one of the major mediators for pain and fever during inflammation, and cyclooxygenases (COX) catalyze the rate-limiting step of PGE2 biosynthesis. IL-17 induces COX-2 [86, 98] as well as microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 (mPGES-1) [99], thus enhancing PGE2 production. Nitric oxide (NO) is an important inflammatory second messenger, and pathological NO is generated by inducible NO synthase (iNOS) during inflammation. IL-17A triggers a dose- and time-dependent expression of iNOS and concomitant increase in NO in various cell types [98, 100, 101]. The acute phase protein 24p3/Lipocalin 2 exhibits potent antibacterial activities by competing with bacterial siderophores to limit bacterial intake of free iron [102]. 24p3 is strongly enhanced by IL-17 and/or TNFα in osteoblasts, fibroblasts and bone marrow stromal cells [83, 103]. Human β-defensin-2 (hBD2) is an antimicrobial peptide secreted by epithelial cells that provides protection against a broad spectrum of microorganisms, and IL-17 markedly up-regulates hBD2 and its murine homologue mBD3 but not mBD4 in airway epithelium [104]. In primary keratinocytes, IL-17 regulates the expression of other antimicrobial peptides such as S100A7, S100A8, and S100A9 in combination with IL-22 [25]. IL-17 also regulates mucins in airways [105]. Thus, IL-17 gene targets cover a broad spectrum of pro-inflammatory/host defensive activities.

5.2 IL-17 regulates genes involved in bone turnover

Overwhelming data implicate IL-17 as a bone-erosive factor in arthritis [28, 106]. Bone destruction is mediated by osteoclasts, hematopoietic cells that are induced to mature by the TNFR-family members RANK and RANKL [107]. Inflammation, particularly when it occurs in proximity to bone in diseases such as RA and periodontal disease, causes bone loss in part because activated T and B lymphocytes express RANKL, and therefore promote osteoclastogenesis and subsequent bone destruction [28, 108]. Inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IL-1β also enhance RANKL expression in osteoblasts, further driving osteoclast formation [107]. Not surprisingly, IL-17 promotes RANKL expression [109, 110] and blocking IL-17 in vivo reduces RANKL expression and associated joint damage [111, 112]. Strikingly, Th17 cells express higher levels of RANKL than other T cell subsets [113]. Furthermore, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are major players in matrix destruction and tissue damage in arthritis, and the balance between MMPs and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase (TIMPs) are critical to maintaining normal bone metabolism [114]. IL-17 can induce MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-9 and MMP-13 [115–123], and IL-17 also regulates TIMP-1 [115, 118, 124].

5.3 Transcription factors involved in regulating IL-17 gene targets

5.3.1. NF-κB

Taken as a whole, the spectrum of IL-17 target genes sheds important light on the end-point of IL-17 receptor-mediated signal transduction. Nearly all IL-17 target genes are also positively regulated by IL-1β and TLR ligands such as LPS, suggesting similarity in their signaling mechanisms. Like the TLR and IL-1R families, IL-17 activates NF-κB, a classic inflammatory transcription factor (TF) used by diverse stimuli including antigen receptors, inflammatory cytokines and UV light [48, 125]. Although NF-κB exists in multiple isoforms, gel shift analyses have demonstrated that the major IL-17-activated NF-κB isoform consists of the canonical pathway components, p65 and p50. To date, there is no evidence for involvement of the non-canonical pathway involving processing of p100 and regulation of the RelB/p52 complex; although NIK, which is involved in the non-classical pathway, has been reported to be downstream of IL-17 signaling [126]. Interestingly, IκBζ is also induced by IL-17 [84, 103]. Unlike other IκBs, which act as inhibitors by masking the nuclear localization signal of NF-κB and retaining it in the cytoplasm, IκBζ is expressed in the nucleus and is required for IL-6 expression by the TLR and IL-1R pathways [127]. It is not yet known whether IκBζ is required for IL-17 signaling. Although it is clear that IL-17 activates NF-κB, its activation is considerably more modest then TLR agonists or TNFα, even at very high concentrations of IL-17 [72, 128]. Moreover, IL-17 fails to activate a linked NF-κB reporter gene in all cell lines examined, even in settings where potent NF-κB DNA binding is observed (FS, unpublished observations). Based on the dissimilarity of their respective receptors, it is unlikely that IL-17RA is simply a duplicated receptor for TLR/IL-1R signaling. Indeed, IL-17RA-deficient mice with intact TLR/IL-1R systems nonetheless fail to mount effective immune responses for host defense to a wide variety of organisms (reviewed in [30]).

5.3.2. CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Proteins (C/EBP)

In a microarray screen for IL-17 target genes, IL-17 was found to up-regulate expression of CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins, (C/EBP)-δ and -β [72]. This was a striking finding, since C/EBPs are known to be critical regulators of IL-6 transcription. Indeed, it was subsequently demonstrated in C/EBPβδ-deficient cells that these TFs are essential for IL-17-induced IL-6 expression [72]. Many inflammatory genes contain C/EBP DNA binding elements in their promoters, and in some cases C/EBP proteins cooperate with NF-κB to activate transcription [129]. TLRs also activate C/EBP proteins, although the precise mechanism is not yet known (W. Yeh and P. Ohashi, personal communication [130]). Recently, we performed a bioinformatics analysis of a collection of IL-17 target gene promoters, revealing that not only NF-κB binding sites but also C/EBP sites are statistically over-represented [83]. Standard “promoter bashing” of the mouse IL-6 and 24p3 genes supported an essential role of functional C/EBP proteins in IL-17-mediated transcription [72, 83].

Among the six C/EBP family members, only C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ have been found to be induced by IL-17 [72, 103, 131]. While NF-κB nuclear import and DNA binding occur within 15–30 minutes of IL-17 ligation, activation of C/EBP is a relatively late event, peaking at 2–4 hours post-stimulation in all cell types examined. The time course of C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ protein expression correlates with DNA binding [83]. However, the upstream events that regulate C/EBP activation are poorly understood. C/EBP expression and activities are regulated both transcriptional and by posttranscriptional events. The C/EBPβ protein exists in multiple isoforms, generated by alternative translation [130]. Interestingly, IL-17 preferentially induces the largest C/EBPβ isoform (known as LAP*), but the mechanism underlying this preference is unknown. C/EBPβ is also inducibly phosphorylated in other systems. For example, phosphorylation of Thr188 and subsequently Ser184/Thr179 on C/EBPβ are required for adipocyte differentiation [132], but this has not been reported for IL-17. Numerous kinases have been implicated in C/EBPβ phosphorylation in other pathways, including RSK, MAPK, mixed lineage kinases (MLK), PKC and PKA [133]. Although there are no data indicating that C/EBPδ is subject to post-translational modification, the C/EBPδ gene is capable of autoregulation, as its own enhancer contains a functional C/EBP binding element [134]. It is not clear whether C/EBPβ and C/EPBδ are functionally redundant in terms of IL-17 signaling, as C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ can individually rescue C/EBPβδ-deficient cells for IL-6 promoter activity [72]. However, our recent analysis of the IL-17 receptor demonstrated that a mutant IL-17RA that can activate C/EBPδ but not C/EBPβ is compromised in the induction of some but not all IL-17 target genes [135], suggesting preference for C/EBPβ in some target genes.

5.3.3. Other IL-17-induced transcription factors

In addition to NF-κB and C/EBP, the AP-1 binding site is also enriched in IL-17 target gene promoters [83], consistent with reports showing that IL-17 induces activation of AP-1 [136, 137]. However, other data suggest that IL-17 cannot directly trigger strong AP-1 activation, and the AP-1 site in the IL-6 promoter is dispensable for IL-17-mediated activity [72, 138, 139]. Pharmacological inhibitors of JNK, required for AP-1 formation, in some cases inhibit IL-17 target gene expression [120], which may indicate signaling by an AP-1-dependent mechanism [140]. The enrichment analysis of IL-17 target promoters described above also identified the Oct-1 and Ikaros TF binding sites (TFBS) as over-represented [83]. The Ikaros TFBS is highly similar to the NF-κB TFBS, and hence may be an artifact of the analysis. The significance of Oct-1 is still unknown, but may point to a worthy line of future investigation.

The JAK-STAT pathway has also been implicated in IL-17 signaling ([95, 104, 141] and R. Wu, personal communication) although activation of these factors is weak compared to Type I or II hematopoietic receptors, and could be indicative of secondary responses to IL-17-induced cytokines. Moreover, IL-17 can induce gene expression in STAT-1-deficient cells [142], and there is evidence against a role for tyrosine kinases in IL-17 gene regulation [79]. Future efforts will need to dissect this issue further. Recent data also implicate the phosphatidylinositol 3’-kinase (PI3K) pathway and activation of Akt and GSK3β in regulation of certain IL-17 target genes, including IL-6 and IL-19 (R. Wu, personal communication).

5.4. Proximal mediators of IL-17 signaling

The similarities between IL-17 signaling and IL-1/TLR signaling are further supported by the finding that IL-17 fails to activate NF-κB or ICAM-1 expression in TRAF6-deficient fibroblasts [97]. TRAF6 is an adaptor and E3 ubiquitin ligase that is an essential convergence point for activation of NFκB and MAPK pathways by many stimuli. Whereas some receptors such as CD40 and RANKL bind TRAF6 directly in order to activate NF-κB, TLRs/IL-1R recruit adaptors such as MyD88 and TRIF that activate the IKK complex and lead to NF-κB activation or mobilize the IRF pathway and upregulate Type I interferons [143]. IL-17RA has no obvious TRAF6-binding motifs [144], and cells lacking MyD88 and TRIF are still capable of IL-17 signaling [131, 135], which collectively suggest that TRAF6 interacts with IL-17RA via an adaptor. There is also a recent report indicating that IL-17RA may be ubiquitinated via TRAF6 in response to IL-17F, perhaps revealing an additional role for TRAF6 [145].

A major clue in defining IL-17R proximal signaling events came from a bioinformatics analysis published in 2003 [66]. This report predicted the existence of a motif with homology to a TIR domain (Toll-IL-1 Receptor-like signaling domain), which was termed "SEFIR" for SEF/IL-17R. The SEFIR motif is found in most IL-17R family members, and also in the adaptor molecule Act1 (CIKS). Act1 was originally identified as an activator of NF-κB and p38-MAPK and negatively regulates signaling through CD40 and BAFF [146–148]. The presence of a SEFIR domain in Act1 led two groups to demonstrate that Act1 could co-immunoprecipitate with IL-17RA in a SEFIR-dependent manner. This event is followed by recruitment of TAK1/TRAF6, degradation of IκBα, and IL-17-dependent activation of NF-κB [131, 149]. Act1-deficient cells fail to activate IL-17-dependent IκB degradation or NF-κB DNA binding or induce IL-17 target genes such as KC/Groα, IL-6 or C/EBPδ [131, 149]. Moreover, Act1-deficient mice exhibit resistance to autoimmune encephalomyelitis and dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis, both of which are known to involve Th17 cells [149]. Interestingly, there is some evidence for Act1-independent signaling, as Act1-deficient cells induce phosphorylation of ERK, although only after 24 hours stimulation [149]. Accordingly, Act1 appears to fill an important gap between IL-17RA and TRAF6 (extensively reviewed in Ref. [150]) (Figure 3).

5.5. Signaling motifs within the IL-17RA cytoplasmic tail

Although the SEFIR domain seems to be equivalent to a TIR in its recruitment of an appropriate adaptor that leads to NF-κB activation, this domain is intriguing in that it lacks important structural elements found in bona fide TIR domains. In particular, TIR domains contain a “BB loop” motif that links the second β-strand to the second α-helix, and is crucial for interactions between TIR-containing molecules [151, 152]. Importantly, cell-permeable peptides encoding TLR BB-loops can inhibit signaling, suggesting a possible therapeutic avenue based on understanding the structure of this motif in detail [153, 154]. The BB-loop in TLR4 is the site of the naturally occurring LPSd mutation in C3H mice (P712H) that renders them resistant to LPS-induced shock [155]. Interestingly, there is no obvious BB-loop in the SEFIR motif [66]. However our recent analysis of mouse and human IL-17RA compared to TLR and IL-1R family members identified a BB-loop-like motif (termed a TIR-like loop, TILL) located at the C-terminal end of the IL-17RA-SEFIR with considerable homology to BB-loops [135]. Using a reconstitution system in IL-17RA-deficient fibroblasts, we demonstrated that both the SEFIR and the TILL domains are required for activation of NF-κB and NF-κB-dependent genes. Moreover, a single point mutation within the TILL in a location that aligns with the LPSd mutation (V553H) is sufficient to completely eliminate IL-17-dependent NF-κB activation [135]. These findings indicate that the SEFIR/TILL is an extended functional motif, and it is still not clear where the N-terminus of this motif lies. Deletion of the SEFIR or TILL motifs in IL-17RA also compromised ERK activation. The finding is inconsistent with the observation that ERK can be activated in Act1-deficient cells [149]; however, additional SEFIR-dependent adaptor distinct from Act1 may be involved in ERK signaling.

The SEFIR/TILL domains are also necessary for C/EBPβ and -δ activation [135]. However, IL-17RA mapping analysis revealed unexpectedly that regulation of C/EBPβ but not C/EBPδ expression involves signals from a distal region in the IL-17RA tail. Defects in C/EBPβ activation through this distal domain correlated with a failure to induce some but not all IL-17 target genes, including CCL2 and CCL7 [135]. Interestingly, there is no obvious TILL domain in IL-17RC, although it does contain a predicted SEFIR motif [66]. It will be interesting to determine how IL-17RC contributes to recruitment of Act1 or other signaling events.

In conclusion, IL-17 receptor signal transduction is an emerging area of research, with many new insights generated in the last year. The composition, dynamics and subunit interactions of the receptor complex are beginning to be defined, but there are still many key questions remaining. The intracellular signaling mediated by of IL-17RA is similar to TLR and IL-1 receptor families in terms of gene targets and common transcription factors, but the receptor itself shares only distant homology to classic innate cytokine receptors. Indeed, IL-17 uses a novel adaptor protein Act1, which associates with IL-17RA through a newly-defined SEFIR/TILL motif. No doubt future work in this area will uncover new surprises about the newest of the cytokine receptor families, with implications for understanding and perhaps treating inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgments

SLG was supported by the NIH (AI43929) and the Arthritis Foundation. We thank Drs. Reen Wu (UC Davis, Davis CA), Steven Levin (Zymogenetics, Seattle WA), Pamela Ohashi (U. Toronto, Toronto Canada), Wen-Chen Yeh (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) and Wenjun Ouyang (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) for sharing unpublished information.

Abbreviations used

RA

rheumatoid arthritis

PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3’-kinase

FN

fibronectin III-like

FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

IL-

interleukin

PLAD

pre-ligand assembly domain

SEFIR

SEF/IL-17R signaling motif

TIR

Toll/IL-1R signaling motif

C/EBP

CCAAT/Enhancer binding protein

TILL

TIR-like loop

RANKL

receptor activator of NF-κB ligand

TF

transcription factor

TFBS

transcription factor binding site

EPO

erythropoietin

MS

multiple sclerosis

Th

T helper

ICAM

intracellular adhesion molecule

BD

β-defensin

COX

cyclooxygenase

TIMP

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase

MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

UTR

untranslated region

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ozaki K, Leonard WJ. Cytokine and cytokine receptor pleiotropy and redundancy. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29355–29358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggarwal S, Gurney AL. IL-17: A prototype member of an emerging family. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2002;71:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moseley TA, Haudenschild DR, Rose L, Reddi AH. Interleukin-17 family and IL-17 receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:155–174. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fossiez F, Djossou O, Chomarat P, Flores-Romo L, Ait-Yahia S, Maat C, Pin J-J, Garrone P, Garcia E, Saeland S, Blanchard D, Gaillard C, Das Mahapatra B, Rouvier E, Golstein P, Banchereau J, Lebecque S. T cell interleukin-17 induces stromal cells to produce proinflammatory and hematopoietic cytokines. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:2593–2603. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He D, Wu L, Kim HK, Li H, Elmets CA, Xu H. CD8+ IL-17-producing T cells are important in effector functions for the elicitation of contact hypersensitivity responses. J Immunol. 2006;177:6852–6858. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shibata K, Yamada H, Hara H, Kishihara K, Yoshikai Y. Resident Vdelta1+ gammadelta T cells control early infiltration of neutrophils after Escherichia coli infection via IL-17 production. J Immunol. 2007;178:4466–4472. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stark MA, Huo Y, Burcin TL, Morris MA, Olson TS, Ley K. Phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils regulates granulopoiesis via IL-23 and IL-17. Immunity. 2005;22:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aarvak T, Chabaud M, Miossec P, Natvig JB. IL-17 is produced by some proinflammatory Th1/Th0 cells but not by Th2 cells. J. Immunol. 1999;162:1246–1251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albanesi C, Cavani A, Girolomoni G. IL-17 is produced by nickel-specific T lymphocytes and regulates ICAM-1 expression and chemokine production in human keratinocytes: Synergistic or antagonistic effects with IFN-γ and TNF-α. J. Immunol. 1999;162:494–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aggarwal S, Ghilardi N, Xie MH, De Sauvage FJ. Gurney AL. Interleukin 23 promotes a distinct CD4 T cell activation state characterized by the production of interleukin 17. J Biol Chem. 2002;3:1910–1914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Happel KI, Zheng M, Young E, Quinton LJ, Lockhart E, Ramsay AJ, Shellito JE, Schurr JR, Bagby GJ, Nelson S, Kolls JK. Cutting Edge: Roles of Toll-Like Receptor 4 and IL-23 in IL-17 Expression in Response to Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection. J Immunol. 2003;170:4432–4436. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy CA, Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein W, McClanahan T, Kastelein RA, Sedgwick JD, Cua DJ. Divergent pro- and antiinflammatory roles for IL-23 and IL-12 in joint autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1951–1957. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cua DJ, Sherlock J, Chen Y, Murphy CA, Joyce B, Seymour B, Lucian L, To W, Kwan S, Churakova T, Zurawski S, Wiekowski M, Lira SA, Gorman D, Kastelein RA, Sedgwick JD. Interleukin-23 rather than interleukin-12 is the critical cytokine for autoimmune inflammation of the brain. Nature. 2003;421:744–748. doi: 10.1038/nature01355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trinchieri G, Pflanz S, Kastelein RA. The IL-12 family of heterodimeric cytokines: new players in the regulation of T cell responses. Immunity. 2003;19:641–644. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00296-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, Mattson J, Basham B, Sedgwick JD, McClanahan T, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:233–240. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langrish CL, McKenzie BS, Wilson NJ, de Waal Malefyt R, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ. IL-12 and IL-23: master regulators of innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:96–105. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong C. Diversification of T-helper-cell lineages: finding the family root of IL-17-producing cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nri1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cua DJ, Kastelein RA. TGF-beta, a 'double agent' in the immune pathology war. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:557–559. doi: 10.1038/ni0606-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weaver CT, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Harrington LE. IL-17 Family Cytokines and the Expanding Diversity of Effector T Cell Lineages. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:821–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weaver CT, Murphy KM. T-cell subsets: the more the merrier. Curr Biol. 2007;17:R61–R63. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sutton C, Brereton C, Keogh B, Mills KH, Lavelle EC. A crucial role for interleukin (IL)-1 in the induction of IL-17-producing T cells that mediate autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1685–1691. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nurieva R, Yang XO, Martinez G, Zhang Y, Panopoulos AD, Ma L, Schluns K, Tian Q, Watowich SS, Jetten AM, Dong C. Essential autocrine regulation by IL-21 in the generation of inflammatory T cells. Nature. 2007;448:480–483. doi: 10.1038/nature05969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korn T, Bettelli E, Gao W, Awasthi A, Jager A, Strom TB, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-21 initiates an alternative pathway to induce proinflammatory T(H)17 cells. Nature. 2007;448:484–487. doi: 10.1038/nature05970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou L, Ivanov, Spolski R, Min R, Shenderov K, Egawa T, Levy DE, Leonard WJ, Littman DR. IL-6 programs T(H)-17 cell differentiation by promoting sequential engagement of the IL-21 and IL-23 pathways. Nat Immunol. 2007 doi: 10.1038/ni1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang SC, Tan XY, Luxenberg DP, Karim R, Dunussi-Joannopoulos K, Collins M, Fouser LA. Interleukin (IL)-22 and IL-17 are coexpressed by Th17 cells and cooperatively enhance expression of antimicrobial peptides. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2271–2279. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung Y, Yang X, Chang SH, Ma L, Tian Q, Dong C. Expression and regulation of IL-22 in the IL-17-producing CD4+ T lymphocytes. Cell Res. 2006;16:902–907. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stockinger B, Veldhoen M. Differentiation and function of Th17 T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaffen SL. Interleukin-17: A Unique Inflammatory Cytokine With Roles in Bone Biology and Arthritis. Arth Res Ther. 2004;6:240–247. doi: 10.1186/ar1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weaver CT, Harrington LE, Mangan PR, Gavrieli M, Murphy KM. Th17: an effector CD4 T cell lineage with regulatory T cell ties. Immunity. 2006;24:677–688. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kolls JK, Linden A. Interleukin-17 family members and inflammation. Immunity. 2004;21:467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rouvier E, Luciani M-F, Mattei M-G, Denizot F, Golstein P. CTLA-8, cloned from an activated T cell, bearing AU-rich messenger RNA instability sequences, and homologous to a Herpesvirus Saimiri gene. J. Immunol. 1993;150:5445–5456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Starnes T, Robertson MJ, Sledge G, Kelich S, Nakshatri H, Broxmeyer HE, Hromas R. Cutting edge: IL-17F, a novel cytokine selectively expressed in activated T cells and monocytes, regulates angiogenesis and endothelial cell cytokine production. J Immunol. 2001;167:4137–4140. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hymowitz SG, Filvaroff EH, Yin JP, Lee J, Cai L, Risser P, Maruoka M, Mao W, Foster J, Kelley RF, Pan G, Gurney AL, de Vos AM, Starovasnik MA. IL-17s adopt a cystine knot fold: structure and activity of a novel cytokine, IL-17F, and implications for receptor binding. Embo J. 2001;20:5332–5341. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright JF, Guo Y, Quazi A, Luxenberg DP, Bennett F, Ross JF, Qiu Y, Whitters MJ, Tomkinson KN, Dunussi-Joannopoulos K, Carreno BM, Collins M, Wolfman NM. Identification of an Interleukin 17F/17A Heterodimer in Activated Human CD4+ T Cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13447–13455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700499200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang SH, Dong C. A novel heterodimeric cytokine consisting of IL-17 and IL-17F regulates inflammatory responses. Cell Res. 2007;17:435–440. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Turner H, Murphy TL, Murphy KM, Weaver CT. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1123–1132. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang YH, Angkasekwinai P, Lu N, Voo KS, Arima K, Hanabuchi S, Hippe A, Corrigan CJ, Dong C, Homey B, Yao Z, Ying S, Huston DP, Liu YJ. IL-25 augments type 2 immune responses by enhancing the expansion and functions of TSLP-DC-activated Th2 memory cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1837–1847. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kleinschek MA, Owyang AM, Joyce-Shaikh B, Langrish CL, Chen Y, Gorman DM, Blumenschein WM, McClanahan T, Brombacher F, Hurst SD, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ. IL-25 regulates Th17 function in autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:161–170. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharkhuu T, Matthaei KI, Forbes E, Mahalingam S, Hogan SP, Hansbro PM, Foster PS. Mechanism of interleukin-25 (IL-17E)-induced pulmonary inflammation and airways hyper-reactivity. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36:1575–1583. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Angkasekwinai P, Park H, Wang YH, Chang SH, Corry DB, Liu YJ, Zhu Z, Dong C. Interleukin 25 promotes the initiation of proallergic type 2 responses. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1509–1517. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ballantyne SJ, Barlow JL, Jolin HE, Nath P, Williams AS, Chung KF, Sturton G, Wong SH, McKenzie AN. Blocking IL-25 prevents airway hyperresponsiveness in allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hurst SD, Muchamuel T, Gorman DM, Gilbert JM, Clifford T, Kwan S, Menon S, Seymour B, Jackson C, Kung TT, Brieland JK, Zurawski SM, Chapman RW, Zurawski G, Coffman RL. New IL-17 family members promote Th1 or Th2 responses in the lung: in vivo function of the novel cytokine IL-25. J Immunol. 2002;169:443–453. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fort MM, Cheung J, Yen D, Li J, Zurawski SM, Lo S, Menon S, Clifford T, Hunte B, Lesley R, Muchamuel T, Hurst SD, Zurawski G, Leach MW, Gorman DM, Rennick DM. IL-25 induces IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and Th2-associated pathologies in vivo. Immunity. 2001;15:985–995. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaffen SL, Kramer JM, Yu JJ, Shen F. The IL-17 Cytokine Family. In: Litwack G, editor. Vitamins and Hormones. London: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 255–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feldmann M, Steinman L. Design of effective immunotherapy for human autoimmunity. Nature. 2005;435:612–619. doi: 10.1038/nature03727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Filler SG, Yeaman MR, Sheppard DC. Tumor necrosis factor inhibition and invasive fungal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41 Suppl 3:S208–S212. doi: 10.1086/430000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kikly K, Liu L, Na S, Sedgwick JD. The IL-23/Th(17) axis: therapeutic targets for autoimmune inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:670–675. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao Z, Fanslow WC, Seldin MF, Rousseau A-M, Painter SL, Comeau MR, Cohen JI, Spriggs MK. Herpesvirus Saimiri encodes a new cytokine, IL-17, which binds to a novel cytokine receptor. Immunity. 1995;3:811–821. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yao Z, Spriggs MK, Derry JMJ, Strockbine L, Park LS, VandenBos T, Zappone J, Painter SL, Armitage RJ. Molecular characterization of the human interleukin-17 receptor. Cytokine. 1997;9:794–800. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Toy D, Kugler D, Wolfson M, Vanden Bos T, Gurgel J, Derry J, Tocker J, Peschon JJ. Cutting Edge: Interleukin-17 signals through a heteromeric receptor complex. J. Immunol. 2006;177:36–39. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haudenschild D, Moseley T, Rose L, Reddi AH. Soluble and transmembrane isoforms of novel interleukin-17 receptor-like protein by RNA splicing and expression in prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4309–4316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haudenschild DR, Curtiss SB, Moseley TA, Reddi AH. Generation of interleukin-17 receptor-like protein (IL-17RL) in prostate by alternative splicing of RNA. Prostate. 2006;66:1268–1274. doi: 10.1002/pros.20422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuestner R, Taft D, Haran A, Brandt C, Brender T, Lum K, Harder B, Okada S, Osatrander C, Kreindler J, Aujla S, Reardon B, Moore M, Shea P, Schreckhise R, Bukowski T, Presnell S, Guerra-Lewis P, Parrish-Novak J, Ellsworth J, Jaspers S, Lewis K, Appleby M, Kolls J, Rixon M, West J, Gao Z, Levin S. Identification of the IL-17 receptor related molecule, IL-17RC, as the receptor for IL-17F. J Immunol. 2007;179:5462–5473. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Latz E, Verma A, Visintin A, Gong M, Sirois CM, Klein DC, Monks BG, McKnight CJ, Lamphier MS, Duprex WP, Espevik T, Golenbock DT. Ligand-induced conformational changes allosterically activate Toll-like receptor 9. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:772–779. doi: 10.1038/ni1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Livnah O, Stura EA, Middleton SA, Johnson DL, Jolliffe LK, Wilson IA. Crystallographic evidence for preformed dimers of erythropoietin receptor before ligand activation. Science. 1999;283:987–990. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5404.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krause C, Mei E, Xie J, Bopp M, Hochstrasser R, Pestka S. Seeing the light: preassembly and ligand-induced changes of the interferon gamma receptor complex in cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:805–815. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200065-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chan FK. Three is better than one: pre-ligand receptor assembly in the regulation of TNF receptor signaling. Cytokine. 2007;37:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chan FK, Chun HJ, Zheng L, Siegel RM, Bui KL, Lenardo MJ. A domain in TNF receptors that mediates ligand-independent receptor assembly and signaling. Science. 2000;288:2351–2354. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan FK-M. The pre-ligand binding assembly domain: A potential target of inhibition of tumour necrosis factor receptor function. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59 Suppl I:i50–i53. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.suppl_1.i50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Siegel RM, Frederiksen JK, Zacharias DA, Chan FK, Johnson M, Lynch D, Tsien RY, Lenardo MJ. Fas preassociation required for apoptosis signaling and dominant inhibition by pathogenic mutations. Science. 2000;288:2354–2357. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sedger LM, Osvath SR, Xu XM, Li G, Chan FK, Barrett JW, McFadden G. Poxvirus tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-like T2 proteins contain a conserved preligand assembly domain that inhibits cellular TNFR1-induced cell death. J Virol. 2006;80:9300–9309. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02449-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Deng GM, Zheng L, Chan FK, Lenardo M. Amelioration of inflammatory arthritis by targeting the pre-ligand assembly domain of tumor necrosis factor receptors. Nat Med. 2005;11:1066–1072. doi: 10.1038/nm1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kramer J, Yi L, Shen F, Maitra A, Jiao X, Jin T, Gaffen S. Cutting Edge: Evidence for ligand-independent multimerization of the IL-17 receptor. J Immunol. 2006;176:711–715. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Remy I, Wilson IA, Michnick SW. Erythropietin receptor activation by a ligand-induced conformation change. Science. 1999;283:990–993. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5404.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Neiditch MB, Federle MJ, Pompeani AJ, Kelly RC, Swem DL, Jeffrey PD, Bassler BL, Hughson FM. Ligand-induced asymmetry in histidine sensor kinase complex regulates quorum sensing. Cell. 2006;126:1095–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Novatchkova M, Leibbrandt A, Werzowa J, Neubuser A, Eisenhaber F. The STIR-domain superfamily in signal transduction, development and immunity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:226–229. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Murphy JM, Young IG. IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF signaling: crystal structure of the human beta-common receptor. Vitam Horm. 2006;74:1–30. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(06)74001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kramer J, Hanel W, Shen F, Isik N, Malone J, Maitra A, Sigurdson W, Swart D, Tocker J, Jin T, Gaffen SL. Cutting Edge: Identification of the pre-ligand assembly domain (PLAD) and ligand binding site in the IL-17 receptor. J Immunol. 2007 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6379. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yao Z, Painter SL, Fanslow WC, Ulrich D, Macduff BM, Spriggs MK, Armitage RJ. Cutting Edge: Human IL-17: A novel cytokine derived from T cells. J. Immunol. 1995;155:5483–5486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shimada M, Andoh A, Hata K, Tasaki K, Araki Y, Fujiyama Y, Bamba T. IL-6 secretion by human pancreatic periacinar myofibroblasts in response to inflammatory mediators. J Immunol. 2002;168:861–868. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ruddy MJ, Wong GC, Liu XK, Yamamoto H, Kasayama S, Kirkwood KL, Gaffen SL. Functional cooperation between interleukin-17 and tumor necrosis factor-α is mediated by CCAAT/enhancer binding protein family members. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2559–2567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308809200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chabaud M, Fossiez F, Taupin JL, Miossec P. Enhancing effect of IL-17 on IL-1-induced IL-6 and leukemia inhibitory factor production by rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes and its regulation by Th2 cytokines. J Immunol. 1998;161:409–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Teunissen MB, Koomen CW, de Waal Malefyt R, Wierenga EA, Bos JD. Interleukin-17 and interferon-γ synergize in the enhancement of proinflammatory cytokine production by human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:645–649. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lindsten T, June CH, Ledbetter JA, Stella G, Thompson CB. Regulation of lymphokine messenger RNA stability by a surface-mediated T-cell activation pathway. Science. 1989;244:339–343. doi: 10.1126/science.2540528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hata K, Andoh A, Shimada M, Fujino S, Bamba S, Araki Y, Okuno T, Fujiyama Y, Bamba T. IL-17 stimulates inflammatory responses via NF-kappaB and MAP kinase pathways in human colonic myofibroblasts. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G1035–G1044. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00494.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Henness S, Johnson CK, Ge Q, Armour CL, Hughes JM, Ammit AJ. IL-17A augments TNF-alpha-induced IL-6 expression in airway smooth muscle by enhancing mRNA stability. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:958–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tokuda H, Kanno Y, Ishisaki A, Takenaka M, Harada A, Kozawa O. Interleukin (IL)-17 enhances tumor necrosis factor-alpha-stimulated IL-6 synthesis via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in osteoblasts. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:1053–1061. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cai XY, Gommoll CP, Jr, Justice L, Narula SK, Fine JS. Regulation of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor gene expression by interleukin-17. Immunol Lett. 1998;62:51–58. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(98)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Andoh A, Yasui H, Inatomi O, Zhang Z, Deguchi Y, Hata K, Araki Y, Tsujikawa T, Kitoh K, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Takayanagi A, Shimizu N, Fujiyama Y. Interleukin-17 augments tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced granulocyte and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor release from human colonic myofibroblasts. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:802–810. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1632-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Witowski J, Pawlaczyk K, Breborowicz A, Scheuren A, Kuzlan-Pawlaczyk M, Wisniewska J, Polubinska A, Friess H, Gahl GM, Frei U, Jorres A. IL-17 stimulatesv intraperitoneal neutrophil infiltration through the release of GRO alpha chemokine from mesothelial cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:5814–5821. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ruddy MJ, Shen F, Smith J, Sharma A, Gaffen SL. Interleukin-17 regulates expression of the CXC chemokine LIX/CXCL5 in osteoblasts: Implications for inflammation and neutrophil recruitment. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004;76:135–144. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0204065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shen F, Hu Z, Goswami J, Gaffen SL. Identification of common transcriptional regulatory elements in interleukin-17 target genes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24138–24148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yamazaki S, Muta T, Matsuo S, Takeshige K. Stimulus-specific induction of a novel nuclear factor-kappaB regulator, IkappaB-zeta, via Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor is mediated by mRNA stabilization. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1678–1687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409983200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Faour WH, Mancini A, He QW, Di Battista JA. T-cell-derived interleukin-17 regulates the level and stability of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) mRNA through restricted activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade: role of distal sequences in the 3'-untranslated region of COX-2 mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26897–26907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212790200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.LeGrand A, Fermor B, Fink C, Pisetsky DS, Weinberg JB, Vail TP, Guilak F. Interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-17 synergistically up-regulate nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 production in explants of human osteoarthritic knee menisci. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2078–2083. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200109)44:9<2078::AID-ART358>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Andoh A, Hata K, Araki Y, Fujiyama Y, Bamba T. Interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-17 synergistically stimulate IL-6 secretion in human colonic myofibroblasts. Int J Mol Med. 2002;10:631–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jones CE, Chan K. Interleukin-17 stimulates the expression of interleukin-8, growth-related oncogene-alpha, and granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor by human airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:748–753. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.6.4757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dragon S, Rahman MS, Yang J, Unruh H, Halayko AJ, Gounni AS. IL-17 enhances IL-1beta-mediated CXCL-8 release from human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L1023–L1029. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00306.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Khader SA, Bell GK, Pearl JE, Fountain JJ, Rangel-Moreno J, Cilley GE, Shen F, Eaton SM, Gaffen SL, Swain SL, Locksley RM, Haynes L, Randall TD, Cooper AM. IL-23 and IL-17 in the establishment of protective pulmonary CD4(+) T cell responses after vaccination and during Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:369–377. doi: 10.1038/ni1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Linden A, Laan M, Anderson G. Neutrophils, interleukin-17A and lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:159–172. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00032904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Laan M, Cui A-H, Hoshino H, Lötvall J, Sjöstrand M, Gruenert DC, Skoogh B-E, Lindén A. Neutrophil recruitment by human IL-17 via C-X-C chemokine release in the airways. J. Immunol. 1999;162:2347–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Van Kooten C, Boonstra JG, Paape ME, Fossiez F, Banchereau J, Lebecque S, Bruijn JA, De Fijter JW, Van Es LA, Daha MR. Interleukin-17 activates human renal epithelial cells in vitro and is expressed during renal allograft rejection. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:1526–1534. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V981526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Takaya H, Andoh A, Makino J, Shimada M, Tasaki K, Araki Y, Bamba S, Hata K, Fujiyama Y, Bamba T. Interleukin-17 stimulates chemokine (interleukin-8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1) secretion in human pancreatic periacinar myofibroblasts. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:239–245. doi: 10.1080/003655202753416948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rahman MS, YamasakiQ A, Yang J, Shan L, Halayko AJ, Gounni AS. IL-17A induces eotaxin-1/CC chemokine ligand 11 expression in human airway smooth muscle cells: role of MAPK (Erk1/2, JNK, and p38) pathways. J Immunol. 2006;177:4064–4071. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.4064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kao C-Y, Huang F, Chen Y, Thai P, Wachi S, Kim C, Tam L, Wu R. Up-regulation of CC chemokine ligand 20 expression in human airway epithelium by IL-17 through a JAK-independent but MEK-NF-kappaB-dependent signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2005;175:6676–6685. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schwandner R, Yamaguchi K, Cao Z. Requirement of tumor necrosis factor-associated factor (TRAF)6 in interleukin 17 signal transduction. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:1233–1239. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shalom-Barak T, Quach J, Lotz M. Interleukin-17-induced gene expression in articular chondrocytes is associated with activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and NF-kappaB. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:27467–27473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lix X, Afif H, Cheng S, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP, Ranger P, Fahmi H. Expression and regulation of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 in human osteoarthritic cartilage and chondrocytes. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:887–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Trajkovic V, Stosic-Grujicic S, Samardzic T, Markovic M, Miljkovic D, Ramic Z, Mostarica Stojkovic M. Interleukin-17 stimulates inducible nitric oxide synthase activation in rodent astrocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;119:183–191. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00391-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Miljkovic D, Trajkovic V. Inducible nitric oxide synthase activation by interleukin-17. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Flo TH, Smith KD, Sato S, Rodriguez DJ, Holmes MA, Strong RK, Akira S, Aderem A. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature. 2004;432:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shen F, Ruddy MJ, Plamondon P, Gaffen SL. Cytokines link osteoblasts and inflammation: microarray analysis of interleukin-17- and TNF-alpha-induced genes in bone cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:388–399. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0904490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kao CY, Chen Y, Thai P, Wachi S, Huang F, Kim C, Harper RW, Wu R. IL-17 markedly up-regulates beta-defensin-2 expression in human airway epithelium via JAK and NF-kappaB signaling pathways. J Immunol. 2004;173:3482–3491. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chen Y, Thai P, Zua Y-H, Ho Y-S, DeSouza M, Wu R. Stimulation of airway mucin gene expression by interleukin (IL)-17 through IL-6 paracrine/autocrine loop. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17036–17043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lubberts E, Koenders MI, van den Berg WB. The role of T cell interleukin-17 in conducting destructive arthritis: lessons from animal models. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:29–37. doi: 10.1186/ar1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Theill L, Boyle W, Penninger J. RANK-L and RANK: T cells, bone loss and mammalian evolution. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:795–823. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Taubman MA, Valverde P, Han X, Kawai T. Immune response: the key to bone resorption in periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2005;76:2033–2041. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kotake S, Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Matsuzaki K, Itoh K, Ishiyama S, Saito S, Inoue K, Kamatani N, Gillespie MT, Martin TJ, Suda T. IL-17 in synovial fluids from patients with rheumatoid arthritis is a potent stimulator of osteoclastogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:1345–1352. doi: 10.1172/JCI5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nakashima T, Kobayashi Y, Yamasaki S, Kawakami A, Eguchic K, Sasaki H, Sakai H. Protein expression and functional difference of membrane-bound and soluble receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand: modulation of the expression by osteotropic factors and cytokines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;275:768–775. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lubberts E, Koenders MI, Oppers-Walgreen B, van den Bersselaar L, Coenen-de Roo CJ, Joosten LA, van den Berg WB. Treatment with a neutralizing anti-murine interleukin-17 antibody after the onset of collagen-induced arthritis reduces joint inflammation, cartilage destruction, and bone erosion. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:650–659. doi: 10.1002/art.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lubberts E, van den Bersselaar L, Oppers-Walgreen B, Schwarzenberger P, Coenen-de Roo CJ, Kolls JK, Joosten LA, van den Berg WB. IL-17 promotes bone erosion in murine collagen-induced arthritis through loss of the receptor activator of NF-kappa B ligand/osteoprotegerin balance. J Immunol. 2003;170:2655–2662. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sato K, Suematsu A, Okamoto K, Yamaguchi A, Morishita Y, Kadono Y, Tanaka S, Kodama T, Akira S, Iwakura Y, Cua DJ, Takayanagi H. Th17 functions as an osteoclastogenic helper T cell subset that links T cell activation and bone destruction. J Exp Med. 2006 doi: 10.1084/jem.20061775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rannou F, Francois M, Corvol MT, Berenbaum F. Cartilage breakdown in rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chabaud M, Garnero P, Dayer JM, Guerne PA, Fossiez F, Miossec P. Contribution of interleukin 17 to synovium matrix destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Cytokine. 2000;12:1092–1099. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Koenders MI, Kolls JK, Oppers-Walgreen B, van den Bersselaar L, Joosten LA, Schurr JR, Schwarzenberger P, van den Berg WB, Lubberts E. Interleukin-17 receptor deficiency results in impaired synovial expression of interleukin-1 and matrix metalloproteinases 3, 9, and 13 and prevents cartilage destruction during chronic reactivated streptococcal cell wall-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3239–3247. doi: 10.1002/art.21342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Koshy PJ, Henderson N, Logan C, Life PF, Cawston TE, Rowan AD. Interleukin 17 induces cartilage collagen breakdown: novel synergistic effects in combination with proinflammatory cytokines. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:704–713. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.8.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bamba S, Andoh A, Yasui H, Araki Y, Bamba T, Fujiyama Y. Matrix metalloproteinase-3 secretion from human colonic subepithelial myofibroblasts: role of interleukin-17. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:548–554. doi: 10.1007/s00535-002-1101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rifas L, Arackal S. T cells regulate the expression of matrix metalloproteinase in human osteoblasts via a dual mitogen-activated protein kinase mechanism. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:993–1001. doi: 10.1002/art.10872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sylvester J, Liacini A, Li WQ, Zafarullah M. Interleukin-17 signal transduction pathways implicated in inducing matrix metalloproteinase-3, -13 and aggrecanase-1 genes in articular chondrocytes. Cell Signal. 2004;16:469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Jovanovic DV, Martel-Pelletier J, Di Battista JA, Mineau F, Jolicoeur F-C, Benderdour M, Pelletier J-P. Stimulation of 92-kd gelatinase (matrix metalloproteinase 9) production by interleukin-17 in human monocyte/macrophages. Arthritis & Rheum. 2000;43:1134–1144. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200005)43:5<1134::AID-ANR24>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Inatomi O, Andoh A, Yagi Y, Ogawa A, Hata K, Shiomi H, Tani T, Takayanagi A, Shimizu N, Fujiyama Y. Matrix metalloproteinase-3 secretion from human pancreatic periacinar myofibroblasts in response to inflammatory mediators. Pancreas. 2007;34:126–132. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000246662.23128.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Park H, Li Z, Yang XO, Chang SH, Nurieva R, Wang YH, Wang Y, Hood L, Zhu Z, Tian Q, Dong C. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1133–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Jovanovic DV, Di Battista JA, Martel-Pelletier J, Reboul P, He Y, Jolicoeur FC, Pelletier JP. Modulation of TIMP-1 synthesis by antiinflammatory cytokines and prostaglandin E2 in interleukin 17 stimulated human monocytes/macrophages. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:712–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lin X, Wang D. The roles of CARMA1, Bcl10, and MALT1 in antigen receptor signaling. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Awane M, Andres PG, Li DJ, Reinecker HC. NF-kappa B-inducing kinase is a common mediator of IL-17-, TNF-alpha-, and IL-1 beta-induced chemokine promoter activation in intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:5337–5344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Yamamoto M, Yamazaki S, Uematsu S, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Kuwata H, Takeuchi O, Takeshige K, Saitoh T, Yamaoka S, Yamamoto N, Yamamoto S, Muta T, Takeda K, Akira S. Regulation of Toll/IL-1-receptor-mediated gene expression by the inducible nuclear protein IkappaBzeta. Nature. 2004;430:218–222. doi: 10.1038/nature02738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hwang SY, Kim JY, Kim KW, Park MK, Moon Y, Kim WU, Kim HY. IL-17 induces production of IL-6 and IL-8 in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts via NF-kappaB- and PI3-kinase/Akt-dependent pathways. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:R120–R128. doi: 10.1186/ar1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Yang T, Chow C-W. Transcription cooperation by NFAT-C/EBP composite enhancer complex. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15874–15885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211560200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ramji DP, Foka P. CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins: structure, function and regulation. Biochem J. 2002;365:561–575. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Chang SH, Park H, Dong C. Act1 adaptor protein is an immediate and essential signaling component of interleukin-17 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35603–35607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Tang QQ, Gronborg M, Huang H, Kim JW, Otto TC, Pandey A, Lane MD. Sequential phosphorylation of CCAAT enhancer-binding protein beta by MAPK and glycogen synthase kinase 3beta is required for adipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9766–9771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503891102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kalvakonalu D, Roy S. CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins and interferon signaling pathways. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25:757–769. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Yamada T, Tsuchiya T, Osada S, Nishihara T, Imagawa M. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein δ gene expression is mediated by autoregulation through downstream binding sites. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;242:88–92. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Maitra A, Shen F, Hanel W, Mossman K, Tocker J, Swart D, Gaffen SL. Distinct functional motifs within the IL-17 receptor regulate signal transduction and target gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, USA. 2007;104:7506–7511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611589104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Andoh A, Takaya H, Makino J, Sato H, Bamba S, Araki Y, Hata K, Shimada M, Okuno T, Fujiyama Y, Bamba T. Cooperation of interleukin-17 and interferon-gamma on chemokine secretion in human fetal intestinal epithelial cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;125:56–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Benderdour M, Tardif G, Pelletier JP, Di Battista JA, Rebou P, Ranger P, Martel-Pelletier J. Interleukin 17 (IL-17) induces collagenase-3 production in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes via AP-1 dependent activation: differential activation of AP-1 members by IL-17 and IL-1beta. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1262–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Granet C, Miossec P. Combination of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1, TNF-alpha and IL-17 leads to enhnaced expression and additional recruitment of AP-1 family members, Egr-1 and NF-kappaB in osteoblast-like cells. Cytokine. 2004;26:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Granet C, Maslinski W, Miossec P. Increased AP-1 and NF-kappaB activation and recruitment with the combination of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1beta, tumor necrosis factor alpha and IL-17 in rheumatoid synoviocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:R190–R198. doi: 10.1186/ar1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.de Haij S, Bakker AC, van der Geest RN, Haegeman G, Vanden Berghe W, Aarbiou J, Daha MR, van Kooten C. NF-kappaB mediated IL-6 production by renal epithelial cells is regulated by c-jun NH2-terminal kinase. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1603–1611. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Subramaniam SV, Cooper RS, Adunyah SE. Evidence for the involvement of JAK/STAT pathway in the signaling mechanism of interleukin-17. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;262:14–19. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Samardzic T, Jankovic V, Stosic-Grujicic S, Trajkovic V. STAT1 is required for iNOS activation, but not IL-6 production in murine fibroblasts. Cytokine. 2001;13:179–182. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Miggin S, O'Neill L. New insights into the regulation of TLR signaling. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:220–226. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]