Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): Epidemiology, etiology and molecular classification (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2022 Jan 28.

Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the primary malignancy of hepatocytes, is a diagnosis with bleak outcome. According to National Cancer Institute’s SEER database, the average five-year survival rate of HCC patients in the US is 19.6% but can be as low as 2.5% for advanced, metastatic disease. When diagnosed at early stages, it is treatable with locoregional treatments including surgical resection, Radio-Frequency Ablation, Trans-Arterial Chemoembolization or liver transplantation. However, HCC is usually diagnosed at advanced stages when the tumor is unresectable, making these treatments ineffective. In such instances, systemic therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) becomes the only viable option, even though it benefits only 30% of patients, provides only a modest (~3 months) increase in overall survival and causes drug resistance within 6 months. HCC, like many other cancers, is highly heterogeneous making a one-size fits all option problematic. The selection of liver transplantation, locoregional treatment, TKIs or immune checkpoint inhibitors as a treatment strategy depends on the disease stage and underlying condition(s). Additionally, patients with similar disease phenotype can have different molecular etiology making treatment responses different. Stratification of patients at the molecular level would facilitate development of the most effective treatment option. With the increase in efficiency and affordability of “omics”-level analysis, considerable effort has been expended in classifying HCC at the molecular, metabolic and immunologic levels. This review examines the results of these efforts and the ways they can be leveraged to develop targeted treatment options for HCC.

1. Introduction

Liver cancer is the fifth most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Among men, it is the fourth most frequent cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Men are at a higher risk of developing liver cancer compared to women. The global HCC incidence ratio of men to women is 2.8:1 (Kulik & El-Serag, 2019). It is worth noting that, despite being only the ninth most common cancer that affects women, it is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women, emphasizing its high mortality rate (Bray et al., 2018). There are two main types of primary liver cancers—hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), with less frequent cancers like angiosarcoma, hemangiosarcoma and hepatoblastoma. While ICC originates from bile ducts, HCC arises from hepatocytes, the main parenchymal cells of the liver. HCC accounts for more than 80% of primary liver cancer cases worldwide (El-Serag & Rudolph, 2007). Secondary liver cancer occurs when a tumor from another part of the body metastasizes to the liver. Although breast, esophageal, stomach, pancreatic, lung, kidney and several other cancers can metastasize to the liver, most secondary liver cancers originate from colorectal cancers. Approximately 70% of colorectal cancer patients develop secondary liver cancer (Valderrama-Trevino, Barrera-Mera, Ceballos-Villalva, & Montalvo-Jave, 2017).

2. Etiology and risk factors

HCC pathogenesis is complex and involves multiple molecular failures such as cell cycle deregulation, DNA methylation alteration, chromosomal instability, immunomodulation, Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal transition, increase in HCC stem cells and microRNA (miRNA) dysregulation (Hui, Makuuchi, & Li, 1998; Ogunwobi et al., 2019). Although the disease mechanism varies depending on underlying etiology, the usual sequence is liver injury, chronic inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis and HCC (Fig. 1). The release of molecular mediators like Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPS) from damaged or necrotic cells, and Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPS) by viruses elicits an innate immune response by activation of Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRR) like Toll-like receptor (TLR), C-type lectin Receptors, Nucleotide-binding Oligomerization Domain (NOD)-like receptors and retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors present on various immune cells causing an inflammatory response. An acute inflammatory response is resolved once the external stimulus is eliminated, whereas unresolved chronic inflammation can cause fibrosis and eventually cirrhosis (Villanueva & Luedde, 2016). Most HCCs (80–90%) are preceded by a cirrhotic event (Leong & Leong, 2005).

Fig. 1.

An overview of different HCC etiologies and the potential mechanism causing HCC. Created with Biorender.com.

2.1. Viral infections

Chronic hepatitis caused by Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infections is an important risk factor for HCC. HBV and HCV are both blood-borne pathogens and HCV can also be transmitted through other body fluids. Needle sharing, perinatal transmission and other routes of blood contact from an infected individual are major routes of transmission. In regions with high prevalence of these infections, HBV/HCV coinfection can occur, further increasing risk of HCC development (Donato, Boffetta, & Puoti, 1998). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 257 million people or 3.3% of the global population lives with chronic HBV infection whereas 71 Million live with chronic HCV infection. In 2018, 54.5% and 21.2% of new global HCC cases were attributable to HBV and HCV infections, respectively (Bray et al., 2018). There is a difference in global prevalence of HBV and HCV that is based on geography.

WHO estimates global HBV prevalence through detection of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen (HBsAg). To facilitate reporting, the world is divided into six WHO regions and the most recent HBV prevalence data from these regions are as follows—Western Pacific Region (6.2%), African Region (6.1%), Eastern Mediterranean Region (3.3%), South-East Asian Region (2%), European Region (1.6%) and the Americas Region (0.7%). Although there is no specific treatment for HBV infection, it is preventable by a safe and effective vaccine that provides 98–100% protection against the virus and antiviral treatments can slow the progression of liver damage. The probability of an acute infection becoming chronic is inversely related to age. If infection occurs before the age of 1, there is an 80–90% chance of chronic infection and the probability drops to 30–50% at 1–6 years of age and less than 5% in adults.

HCV prevalence, on the other hand, is estimated based on the presence of antibodies to HCV in a person’s blood. It is estimated to be the highest (>3.5%) in Central Asia and Central Africa, moderate (1.5–3.5%) in South, East and Southeast Asia, and North, East and West Africa, the Middle East, Southern and Tropical Latin America, the Caribbean (Cuba, Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico), Australasia (Australia and New Zealand), and Eastern Europe and low (<1.5%) in Western and Central Europe, North America, Southern Africa, Andean and Central Latin America and Pacific Asia (Japan and South Korea) (Petruzziello, Marigliano, Loquercio, Cozzolino, & Cacciapuoti, 2016). Roughly 30% of people infected with HCV clear the virus spontaneously within 6months of infection. The remaining 70% of HCV-infected individuals develop chronic HCV infection. More than 95% of HCV-infected people can be cured with antiviral drugs.

2.1.1. Hepatitis B virus

HBV is a hepatotropic virus with a relaxed circular and partially double stranded, 3kb DNA genome encoding four overlapping Open Reading Frames (ORF)—S, C, P and X (Liang, 2009). ORF S encodes the surface antigen HBsAg. ORF C encodes the core protein (HBcAg) that forms the viral nucleocapsid or the precore protein (HBeAg) that directs the translation product to the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER). ORF P is translated to a multidomain pol protein with terminal, reverse transcriptase and ribonuclease H domains. ORF X produces a regulatory protein that enhances viral gene expression and replication (Liang, 2009). Once HBV is imported into the nucleus of hepatocytes, the viral genome is repaired to form a covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA). This repaired DNA is then transcribed to form a pregenomic RNA. The pregenomic RNA is encapsulated and reverse transcribed by DNA polymerase to single-stranded linear DNA, which can reproduce the partially double-stranded relaxed circular DNA (rcDNA) in the cytoplasm or form a double stranded linear DNA (dslDNA). The rcDNA is recycled to the nucleus for synthesis of cccDNA or enveloped and released from the hepatocytes. The dslDNA can be integrated into the host genome and this phenomenon occurs in 85–90% of HBV-associated HCC cases (Furuta et al., 2018; Liang, 2009; Tu, Budzinska, Shackel, & Urban, 2017).

Only 5–10% of adults progress to chronic infection, which is defined as persistence of HBsAg for >6months in a patient’s body (Hyams, 1995). A cure for HBV is difficult because of the persistence of the highly stable viral replication intermediate, cccDNA, as a non-integrated episome in the nucleus of infected patients (Zoulim, 2005). Both innate and adaptive immune responses are triggered in response to HBV infection. HBV remains quiescent for a few weeks after infection causing a lack of robust early innate immune responses. Adaptive immunity involving HBV-specific antigens and T cells is the major player in clearing HBV infection (Tan, Koh, & Bertoletti, 2015). Improper T-cell memory maturation causes a lack of HBV antigen-specific T cells and a failure to mount an immune response (Lumley, McNaughton, Klenerman, Lythgoe, & Matthews, 2018). This can cause chronic infection, recurrent liver inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis and HCC. HBV integration into the host genome can cause oncogenesis when integration sites are close to genes like human Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase (hTERT) or other genes involved in cell cycle, proliferation and metabolism (Tu et al., 2017). The viral regulatory protein is suspected to have a role in oncogenesis in addition to its role in viral replication. It is involved in modulating oncogenic pathways, chromosomal instability, oxidative stress, DNA methylation, angiogenesis and migration (Tarocchi, Polvani, Marroncini, & Galli, 2014). Cirrhosis develops in 1.3–2.4% of HBV infected patients (Liaw, Tai, Chu, & Chen, 1988) and 3.9% of chronic HBV patients develop HCC (Takano, Yokosuka, Imazeki, Tagawa, & Omata, 1995).

2.1.1.1. Oncogenic properties of HBx

The viral regulatory protein HBx has a role in oncogenesis in addition to its role in viral replication and chromosomal instability. It is involved in modulating oncogenic pathways, oxidative stress, DNA methylation, angiogenesis and migration (Tarocchi et al., 2014). HBx disrupts p53-mediated apoptosis by forming a p53-HBx complex that prevents nuclear localization of p53 (Elmore et al., 1997; Ueda et al., 1995; Wang et al., 1995) and p53 DNA binding (Wang et al., 1994). Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) over-expression by HBx also prevents p53-mediated apoptosis (Cheng, Yu, Lai, Chan, & Sung, 2008). Other anti-apoptotic mechanisms include caspase-3 inactivation via the HBx-PI3K-Akt-Bad pathway (Lee, Kang-Park, Do, & Lee, 2001), survivin accumulation via the p38/MAPK pathway (Kuo & Chao, 2010), and activation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway (Shen et al., 2013). In addition to promoting cellular proliferation by inhibiting apoptosis, HBx causes liver injury by sensitizing cells to apoptosis. HBx promotes oxidative stress-related apoptosis via caspase-3 cascade and loss of anti-apoptotic protein MCL1 (Hu et al., 2011), and can be p53- (Chirillo et al., 1997) or TNFα-mediated (Su & Schneider, 1997). HBx is negatively correlated to E-cadherin, positively correlated to vimentin and increases migration and invasion in vitro (Jin, Wu, et al., 2017). HBx increases transcription of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) (Lee et al., 2000), angiopoietin (Sanz-Cameno et al., 2006) and increases transcriptional activity of HIF-1α by protein stabilization (Moon et al., 2004) to promote angiogenesis. HBx is also involved in aberrant cell cycle (Lee et al., 2002), increased chromosomal aberration and micronuclei formation (Livezey, Negorev, & Simon, 2002) and abnormal mitotic spindle formation (Forgues et al., 2003; Fujii et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2008; Wen, Golubkov, Strongin, Jiang, & Reed, 2008; Yun et al., 2004). HBx binds to different cellular proteins like Hepatitis B virus X-interacting protein (HBXIP) (Fujii et al., 2006; Wen et al., 2008) and the mitotic checkpoint protein, budding uninhibited by benzimidazol related protein 1 (BubR1), (Kim, Park, et al., 2008) to disrupt spindle formation and chromosome segregation. The RAS/MEK/MAPK pathway is involved in amplification of centrosomes by HBx (Yun et al., 2004).

2.1.1.2. HBV integration and genomic instability

HBV integration into the host genome is random and causes oncogenesis when integration sites are close to genes involved in cell cycle, proliferation and metabolism (Tu et al., 2017). Comparison of paired non-tumor and tumor liver samples have revealed the presence of distinct patterns of increased HBV integration in tumors compared to matched non-tumors (Sung et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2016). Several frequently altered genes and pathways have been described of which the most recurrent genes are TERT and Mixed Lineage Leukemia Gene Homolog 4 (MLL4) (Ding et al., 2012; Fujimoto et al., 2012; Jin et al., 2019; Shiraishi et al., 2014; Sung et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2016). Earlier studies suggested random integration of HBV in the host genome and attributed increased expression of an altered gene to positive selection and clonal propagation (Furuta et al., 2018). However, preferred HBV integration sites have also been identified (Zhao et al., 2016). Telomerase, made up of an RNA and a protein (TERT) subunit, prevents telomere shortening in immortal cells and is overexpressed in HCC (Amisaki, Tsuchiya, Sakabe, Fujiwara, & Shiota, 2019). Integration of HBV Enhancer 1 (Enh1) at the TERT promoter enhances telomerase activation (Sze et al., 2020). HBV integration also increases TERT expression by making the promoter responsive to the androgen pathway (Li et al., 2019). HBV HBx integrates into intron 3 of MLL4, a histone methyltransferase, to form HBx/MLL4 fusion protein that downregulates a specific set of genes to promote HCC (Saigo et al., 2008). Integration into exons 3, 5 and 6 and exon-intron boundaries 3 and 5 were later reported (Dong et al., 2015; Sung et al., 2012) and MLL4 expression pattern was found to vary depending on the integration site. In addition to TERT and MLL4, several other altered genes like cyclin E1 (CCNE1), fibronectin 1 (FN1), protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type D (PTPRD), unc-5 netrin receptor D (UNC5D), neuregulin 3 (NRG3), aryl hydrocarbon receptor repressor (AHRR), Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor 12 (ARHGEF12), RNA binding Fox-1 homolog 1 (RBFOX1), SMAD5, ADP-ribose/CDP-alcohol diphosphatase (ADPRM), keratin 32 (KRT32) and CDK15 have been reported (Ding et al., 2012; Jin et al., 2019; Shiraishi et al., 2014; Sung et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2016).

2.1.1.3. miRNAs and HBV-HCC

microRNAs (miR) are small non-coding RNAs that prevent gene expression by RNA silencing. They can act as oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes depending on their target genes. Deregulation of miRNAs occurs in every step of HCC development after HBV infection (Table 1). The miRNA profile of late-stage HCC differs from that of early infection, inflammatory phase or fibrosis. Additionally, miRNAs involved in major pathways like pI3K/MAPK, WNT/β-Catenin, TP53 and JAK/STAT pathways are deregulated during HBV-HCC development (Sartorius et al., 2019). Some of the most frequently upregulated miRNAs in HBV-HCC include miR-18a, miR-21, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-224 and the most commonly down-regulated miRNAs include miR-26a, miR-101, miR-122, miR-125b, miR-145, miR-199a, miR-199b, miR-200a, and miR-223 (Xu, An, Winkler, & Yu, 2020).

Table 1.

A list of miRNAs deregulated in HBV-related HCC.

| miRNA | Deregulation | Genes/pathways regulated | HCC properties regulated | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-18a | Upregulated | IRF2, CBX7 and BCL2L10 | Proliferation, migration, and invasion | Wang et al. (2018), Yongyu, Lewei, Jian, and Yuqin (2018) |

| miR-21 | Upregulated | PTEN and KLF5 | Proliferation, migration and invasion | Meng et al. (2007), Wang et al. (2019) |

| miRNA-221 | Upregulated | PHF2, PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling | Proliferation, invasion and migration | Fu et al. (2019), Kannan et al. (2019), Liu et al. (2016) |

| miR-222 | Upregulated | AKT signaling | Migration | (Wong et al. (2010) |

| miR-224 | Upregulated | API5, AKT signaling | Proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis | Li et al. (2010), Ma, Tao, Gao, Fan, and Wu (2012), Wang et al. (2008) |

| miR-26a | Downregulated | Cyclin D2 and E2, MEG3, PTEN | Cell cycle arrest, proliferation and metastasis, migration and invasion | Kota et al. (2009), Li et al. (2017), Zhao et al. (2019) |

| miR-101 | Downregulated | EZH2, DNA methyltransferase 3A, SOX9 and Girdin | Apoptosis and autophagy | Cao et al. (2016), Su et al. (2009), Wei et al. (2013), Xu et al. (2014), Xu et al. (2013), Zhang et al. (2012) |

| miR-122 | Downregulated | BCL2L2, NDRG3, snail1 and snail2 | Cell survival, cell proliferation and EMT | Fan et al. (2011), Jin, Wang, et al. (2017), Lin, Gong, Tseng, Wang, and Wu (2008) |

| miR-125b | Downregulated | sirtunin7, HOTTIP, TXNRD1, Sirtuin 6 | Proliferation and metastasis | Hua et al. (2019), Kim et al. (2013), Song et al. (2018), Tsang et al. (2015) |

| miR-145 | Downregulated | ROCK1, IRS1, HDAC2, ADAM17 | Proliferation and motility | Ding et al. (2016), Liu et al. (2014), Noh et al. (2013), Wang et al. (2014) |

| miR-199a | Downregulated | FZD7 | Cell proliferation | Song et al. (2014) |

| miR-199b | Downregulated | JAG1 | proliferation, invasion and migration | Li, Yuan, Zhuang, and Wu (2018) |

| miR-200a | Downregulated | MACC1, ZEB2, Foxa2, CDK6, GAB1 | cell growth, metastasis and migration | Chen et al. (2017), Feng et al. (2015), Wang et al. (2017), Xiao et al. (2013), Yang et al. (2015) |

| miR-223 | Downregulated | stathmin1, ABCB1, FOXO3a | Autophagy, chemoresistance | Wong et al. (2008), Yang et al. (2013), Zhou et al. (2019) |

Expression levels of miR-18a positively correlate with AFP levels, tumor size, TNM stage and intrahepatic vascular invasion. miR-18a over expression in vitro promotes whereas knock down inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCC cells. Interferon regulatory factor 2 (IRF2) and chromobox 7 (CBX7) are direct targets of miR-18a and BCL2-Like 10 (BCL2L10) is a downstream mediator of miR-18a (Wang et al., 2018; Yongyu et al., 2018). miR-21 is involved in tumor proliferation, migration and invasion and directly targets phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and Kruppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) (Meng et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2019). miR-221 promotes HCC cell proliferation, invasion and migration in vitro (Fu et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2016). miR-221 targets plant homeodomain finger protein 2 (PHF2) and miR-221/Astrocyte elevated gene-1 (AEG-1) axis regulates PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling in HCC (Fu et al., 2019; Kannan et al., 2019). miR-222 regulates cell migration through increased AKT signaling (Wong et al., 2010). miR-224 is involved in cell proliferation, migration, invasion, targets apoptosis inhibitor-5 (API5) to promote apoptosis and activates AKT signaling (Li et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2008). miR-26a is a complex miRNA since it acts as an oncogene in certain cancers and as a tumor suppressor in others. In HCC, it targets cyclins D2 and E2 to promote cell cycle arrest and Maternally Expressed Gene 3 (MEG3) to inhibit proliferation and metastasis (Kota et al., 2009; Li et al., 2017). miRNA-26a also increases migration and invasion through targeting PTEN (Li et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2019). This necessitates further exploration of this miRNA. miRNA-101 is downregulated by HBx and promotes apoptosis, inhibits autophagy and targets enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit (EZH2), DNA methyltransferase 3A, SRY-box transcription factor 9 (SOX9), and Girdin in HCC (Cao et al., 2016; Su et al., 2009; Wei et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2013, 2014; Zhang et al., 2012). miR-122 targets the anti-apoptotic gene, BCL2-like protein 2 (BCL2L2), N-myc downstream-regulated gene 3 (NDRG3), snail1 and snail2 to suppress tumor progression (Fan et al., 2011; Jin, Wang, et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2008). miR-125b regulates sirtunin7, long non-coding RNA HOXA transcript at the distal tip (HOTTIP), Thioredoxin Reductase 1 (TXNRD1) and Sirtuin 6 (Hua et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2013; S. Song et al., 2018; Tsang et al., 2015). miR-145 inhibits Rho associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 1 (ROCK1), insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1), histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) and ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (ADAM17) (Ding et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2014; Noh et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014). miR-199a inhibits cell proliferation and targets frizzled class receptor 7 (FZD7) (Song et al., 2014). miR-199b promotes its tumor suppressive activity by directly targeting jagged 1 (JAG1) (Li et al., 2018). miR-200a is a prognostic marker that suppresses cell growth, metastasis and migration by targeting metastasis-associated gene in colon cancer 1 (MACC1), Zinc finger _E_-box binding homeobox 2 (ZEB2), forkhead box A2 (Foxa2), cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (CDK6) and GRB2-associated-binding protein 1 (GAB1) (Chen et al., 2017; Feng et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2015). miR-223 downregulates stathmin1, ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 1 (ABCB1) and forkhead box O3a (FOXO3a) (Wong et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2019).

2.1.1.4. Signaling pathways involved in HBV-HCC

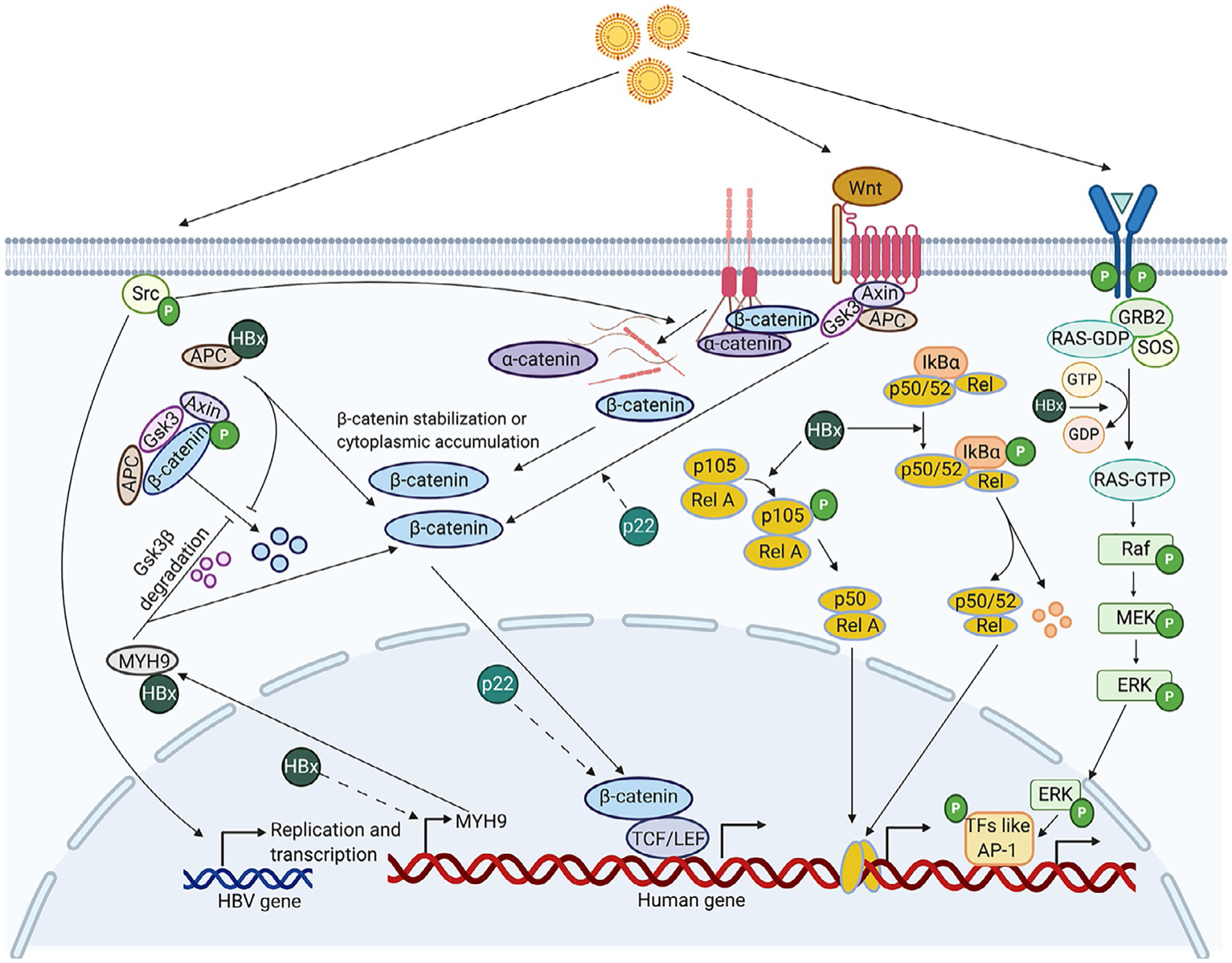

Multiple signaling pathways are known to be deregulated in HBV-related HCC (Fig. 2). Binding of WNT to frizzled family receptor stabilizes β-catenin, which translocates to the nucleus, interacts with T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) and promotes transcription. β-catenin is also bound to E-cadherins in the cytoplasm. E-cadherin loss during EMT is associated with nuclear translocation of β-catenin. The WNT/β-catenin pathway is commonly deregulated in HCC. Interaction between the ligand Wnt3 and receptor Frizzled-7 receptor is observed in HBV-related HCC (Kim, Lee, et al., 2008). The HBx protein is required for activating WNT/β-catenin signaling in HCC cells. HBx stabilizes cytoplasmic β-catenin by src kinase activation and activates WNT/β-catenin signaling in vitro (Cha, Kim, Park, & Ryu, 2004). HBx also activates WNT/β-catenin pathway by binding to the tumor suppressor, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), displacing β-catenin leading to its upregulation in the nucleus (Hsieh et al., 2011). The precore protein, p22, is also an activator of TCF/β-catenin transcription (Tran et al., 2020). The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway is a cascade of phosphorylation reactions that leads to nuclear localization of ERK and transcription of target genes involved in cellular functions like proliferation, adhesion, angiogenesis and mobility. HBx transactivates the transcription factor AP1 through the MAPK pathway. An increase in levels of activated Raf and ERK was observed due to stimulation of Ras-GTP cycling by HBx (Benn & Schneider, 1994). This pathway increases expression of transcription factors like Activator Protein 1 (AP1) (Cross et al., 1993). HBx also activates NF-κB via the Ras pathway (Su & Schneider, 1996). Association of β-catenin with the scaffolding protein APC is required for its degradation by the APC/Axin/GSK3β complex. HBx stabilizes β-catenin by preventing its degradation through inhibiting APC binding or increasing expression of Non-muscle myosin heavy chain IIA (MYH9), a protein that degrades GSK3-β (Hsieh et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2020). The precore protein p22 also activates Wnt signaling (Tran et al., 2020).

Fig. 2.

An overview of multiple signaling pathways deregulated by HBV and their potential mechanisms. Dotted lines indicate an unknown mechanism. Binding of Wnt3 to Frizzled-7 receptor activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling through β-catenin accumulation and enhanced TCF-mediated transcription (Kim et al., 2008). HBV infection increases phosphorylation of c-Src kinase, causing an increase in HBV transcription and replication and disassembly of adherens junctions. The disassembly of adherens junctions, made of _E_-Cadherin bound to β-catenin, results in increased levels of intracellular E-Cadherin and β-catenin leading to EMT and increased TCF/LEF dependent β-catenin signaling (von Olshausen et al., 2018). Association of β-catenin with the scaffolding protein APC is required for its degradation by the APC/Axin/GSK3β complex. HBx protein competitively binds to APC, preventing its association with β-catenin, leading to increased β-catenin stabilization (Hsieh, Kim, Lim, Yu, & Jung, 2011). Increased stabilization of β-catenin leads to an increase in levels of its downstream effectors like c-MYC and a decrease in E-cadherin expression (Not shown in illustration). HBx also transcriptionally regulates MYH9 through β-catenin signaling and interacts with Non-muscle myosin heavy chain IIA (MYH9) to facilitate ubiquitin mediated GSK3β degradation, thus stabilizing β-catenin (Lin et al., 2020). HBx also enhances MAPK/ERK pathway by activating Ras-GTP complex formation (Benn & Schneider, 1994). The transcription factor AP1 is activated through this pathway (Cross, Wen, & Rutter, 1993). HBx induces phosphorylation and degradation of the NF-κB inhibitor, IκBα and a decrease in levels of the p52 precursor, p105 (Su & Schneider, 1996). The precore protein p22 also activates Wnt signaling potentially both in the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Tran et al., 2020). Created with Biorender.com.

2.1.2. Hepatitis C virus

HCV is a single-stranded RNA virus with a 9.6kb long genome composed of 5′ and 3′ noncoding regions and a single ORF that encodes a polyprotein cleaved by cellular and viral proteases in a specific order co- and post-translationally to produce structural (C, E1 and E2) and nonstructural (NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, NS5B and P7) viral proteins (Bukh, 2016). The structural protein C forms the nucleocapsid and E1 and E2 are envelope glycoproteins. The nonstructural protein NS2 is a cysteine protease and NS3 a serine protease with nucleoside-triphosphatase (NTPase)/RNA helicase activity. N4A forms a non-covalent complex with and is a cofactor of NS3, and NS5A is involved in modulation of RNA replication and viral assembly. NS4B forms an intracellular membrane structure on which viral replication occurs. NS5B is an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and p7 is a viroporin involved in viral secretion (Ashfaq, Javed, Rehman, Nawaz, & Riazuddin, 2011).

HCV enters host cells through interaction of the two viral surface glycoproteins E1 and E2 with heparan sulfate proteoglycans on the surface of hepatocytes followed by endocytosis and fusion of cell membranes. The 5’-Untranslated Region (UTR) has an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) element, which recruits the translational machinery to the viral RNA in the cytosol and translation occurs. Encoded viral proteins involved in viral replication and other cellular factors associate with a double-membraned vesicle formed from the ER, where replication takes place. Lipid droplets containing triacylglycerides and cholesteryl esters and surrounded by a phospholipid monolayer are also a part of this structure and have an important role in HCV life cycle. Polymerase NS5B uses the positive stranded RNA as a template and replication occurs through a negative stranded intermediate. The RNA generated can act as a template to further produce RNA or undergo translation to produce new viral proteins that are assembled to form viral particles. Once assembled, HCV particles associated with distinct lipid and apolipoprotein profiles are egressed from the infected cell through the secretory pathway (Kim & Chang, 2013).

The initial immune response to HCV infection is triggered by activation of PRRs like TLR3 and RIG-I through PAMPS released by HCV. Activation of these receptors initiates a cascade of reactions that results in transcription of Interferon-β gene and the production of Interferon stimulated genes (ISGs), that can mutate RNA-specific adenosine deaminase 1 (ADAR1), degrade 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase 1/RNAse L (OAS1/RNAse L) system and inhibit translation (P56 and PKR) of the viral genome. HCV attenuates innate immune response through various mechanisms. HCV NS3/NS4A complex can block TLR3 and RIG-I signaling, and NS5A inhibits OAS. HCV core inhibits signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) activation and NS5A induces interleukin (IL)-8 both of which inhibits ISG expression downstream. HCV E2 and NS5A can inhibit the ISG protein kinase R (PKR) (Rehermann, 2009). There is also evidence of T cell-meditated immune response at 5–9 weeks post-infection. Specific cluster of differentiation (CD) 4+ and CD8+ T cells can act against HCV-derived antigens and eliminate the virus. When this process to clear HCV infection is unsuccessful, acute HCV infection can progress to chronic HCV infection. Chronic HCV infection progresses to HCC through fibrosis and cirrhosis. Fibrosis is accelerated by fat deposition in the liver or hepatic steatosis, specifically in HCV genotype 3 (Asselah, Rubbia-Brandt, Marcellin, & Negro, 2006). Several miRNAs and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are also involved in HCV-related HCC which will be discussed in detail in Chapter 3 (Plissonnier, Herzog, Levrero, & Zeisel, 2018).

2.2. Alcohol

Alcohol consumption increases the risk of not just liver cancer, but also oropharyngeal, colorectal, breast and stomach cancers. The risk of developing cancer is proportional to the amount of alcohol intake. Liver cancer risk increases 46% for consumption of 50g of ethanol per day and 66% for 100g per day compared to non-drinkers (Turati et al., 2014). Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) accounts for about 30% of HCC cases, including HCC occurrences where other risk factors, like obesity, diabetes, hepatitis infections might co-exist with ALD (Ganne-Carrie & Nahon, 2019).

The first sign of liver damage due to alcohol abuse is steatosis or alcohol-associated fatty liver (AFL), which is usually asymptomatic. Although >90% of heavy drinkers develop AFL, it is a reversible condition and only about 30% of them progress to severe ALD. The accumulation of fat in hepatocytes happens primarily through an activation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP-1) causing increased lipogenesis or down-regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-α causing decreased fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) (Gao & Bataller, 2011). In hepatocytes, alcohol is converted to toxic acetaldehyde by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). Acetaldehyde is then converted to non-toxic acetate by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) in the mitochondria and subsequently broken down to H20 and CO2. The first two steps involve reduction of NAD+ to NADH. As more molecules of ethanol are metabolized, intracellular NADH/NAD+ ratio increases disrupting mitochondrial FAO. Increased NADH/NAD+ can also increase the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through the electron transport chain (ETC) (Donohue., 2007). Certain factors like polymorphisms in ADH and ALDH can cause accumulation of acetaldehyde molecules that form adducts with proteins, DNA or both, inhibiting their endogenous function and/or eliciting an intense immune reaction (Brooks & Theruvathu, 2005; Setshedi, Wands, & Monte, 2010).

A steatotic liver is vulnerable to secondary insults that can lead to alcoholic hepatitis (AH) or liver inflammation. It is characterized by activation of liver resident macrophages and recruitment of monocytes, macrophages and neutrophil leukocytes into the liver producing cytokines. The intestinal lumen is surrounded by a mucosal membrane that acts as a barrier between the gut and the liver. A small amount of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) derived from Gram negative bacteria can enter the liver through the portal vein, but it is readily cleared by the liver. Metabolites derived from alcohol can disrupt the tight junction proteins, adherens junction proteins, microtubule cytoskeleton and epithelial cell-cell adhesion, making the gut-liver barrier highly permeable. As a result, high levels of LPS enter the liver and are recognized by receptors like complement receptor 3 (in macrophages), CD14/TLR4 (in monocytes, macrophages, B cells, liver parenchymal cells, and some fibroblast cells) and myeloid differentiation factor (MD)-2/TLR4 (in myeloid and endothelial lineage cells). These receptors present in multiple cell types including liver-resident macrophages are activated to produce cytokines like TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β and IL-8 that cause inflammation. AH is also a reversible stage in alcohol-related HCC, with the solution being cessation of alcohol intake (Szabo & Bala, 2010).

Chronic Alcoholic hepatitis can cause fibrosis by replacement of normal liver parenchymal tissues by connective tissues as a result of an imbalance between synthesis and degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components. Activation of Kupffer cells, release of DAMPs from dying hepatocytes and PAMPS from a leaky gut, and activation of hedgehog-responsive genes can cause activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSC). Activated HSCs transdifferentiate to myofibroblasts that produce ECM components collagen types I, III and IV, fibronectin, hyaluronan, and proteoglycans. Natural killer (NK) cells can kill activated HSCs by inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest through different mechanisms. Alcohol-related fibrosis is linked to a decrease in the number and efficiency of NK cells, increasing HSC activity. The histology of alcohol-related fibrosis is also different from non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) or hepatitis-related fibrosis (Lackner & Tiniakos, 2019; Schuppan, Ashfaq-Khan, Yang, & Kim, 2018). Regression of early fibrosis is possible through cessation of intake of alcohol and research on anti-fibrotic drugs is promising. However, prolonged fibrosis leads to cirrhosis and HCC.

2.3. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

NAFLD refers to a spectrum of liver conditions ranging from steatosis to its more aggressive manifestation NASH. It is the most common liver disorder with a global prevalence of ~25% (Maurice & Manousou, 2018). Twenty percent of patients with early NAFLD or steatosis progress to NASH-cirrhosis, from which 2.6% undergo further progression to HCC (Ascha et al., 2010). Even though the number is lower than for other etiologies, the fact that NAFLD cases are forecasted to increase by 21% and NASH-related HCC by 137% in the US between 2015 and 2030 is of significant concern (Estes, Razavi, Loomba, Younossi, & Sanyal, 2018). Obesity and diabetes are two major risk factors for NAFLD, and the increase in NAFLD cases in the past decade parallels an increase in the worldwide incidence of obesity and diabetes (Younossi, 2019). As the name suggests, the pathology of NAFLD is similar to alcohol-related fatty liver disease, except that the etiology cannot be ascribed to chronic alcohol consumption.

The two-hit hypothesis for NAFLD progression to NASH and cirrhosis is based on steatosis being the first hit, which sensitizes hepatocytes to inflammation, which is the second hit, ultimately leading to fibrosis and cirrhosis. However, with a disease as complicated as NASH, support for the multi-hit hypothesis, which includes genetic and environmental factors, is gaining traction (Buzzetti, Pinzani, & Tsochatzis, 2016). The first stage of NAFLD is simple fatty liver, which is characterized by an excessive accumulation of triglycerides in hepatocytes. This can occur through increased lipolysis of visceral adipose tissue, which is transported to the liver, excess de novo lipogenesis (DNL) in the liver or consumption of high fat diet. Excess Free Fatty Acids (FFA) disrupt the lipid balance within cells, damage cellular organelles like mitochondria and ER, and cause cell injury and cell death. ER stress can cause chronic inflammation by increasing ROS levels and activation of NF-κB and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways. Saturated fatty acids can also activate TLR4 directly in hepatocytes causing increased TNFα production and inflammation (Pierantonelli & Svegliati-Baroni, 2019).

In response to hepatocyte injury, lymphocytes and natural killer T cells are recruited to the liver and produce IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor superfamily member 14 (TNFSF14). Signals from the gut can also activate an innate immune response through TLRs, causing inflammation. This activates liver-resident macrophages that release inflammatory cytokines and the resultant chronic inflammation culminates in HCC.

2.4. Aflatoxins

Aflatoxins are mycotoxins produced by fungal species like Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus. Chemically, they are furanocoumarin compounds, composed of a furan ring fused with a coumarin and are synthesized by secondary metabolic pathways in fungi. Most contaminations occur in grains and nuts during their harvest, transport or storage. Upon consumption, aflotoxins can lead to complications like hepatotoxicity, teratogenicity and immunotoxicity in plants and animals. There are more than 20 known aflatoxins, but the four important ones are aflatoxin B1, B2, G1 and G2, with aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) being the most potent hepatocarcinogen (Kumar, Mahato, Kamle, Mohanta, & Kang, 2016).

Aflatoxins are hepatotoxins that cause acute or chronic poisoning. Several outbreaks related to acute aflatoxin poisoning have occurred in countries like India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Kenya and Tanzania causing hundreds of deaths (Sarma, Bhetaria, Devi, & Varma, 2017). Acute poisoning results in liver failure that can present with jaundice, nausea and abdominal pain or can even be fatal. Chronic aflatoxin poisoning is carcinogenic, specifically related to HCC. AFB1-related HCC is most prevalent in Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, where the dry and humid climates are favorable for fungal proliferation. The most common mutation seen in aflatoxin-related HCC patients is an AGGarg→AGTser missense mutation in codon 249 of the p53 gene (Aguilar, Hussain, & Cerutti, 1993). This mutation is known to promote HCC by affecting differentiation and metastasis (Peng, Peng, & Yao, 1998). Aflatoxin can also be metabolized by cytochrome P450 to form reactive genotoxic intermediates like aflatoxin B1–8, 9-oxide (AFBO) which can form DNA adducts in hepatocytes causing DNA damage (Hamid, Tesfamariam, Zhang, & Zhang, 2013). Aflatoxin is capable of inducing chromosomal aberrations and chromosomal strand breaks in human cells (Turkez & Sisman, 2012). In addition to purely mutagenic effects, a meta-analysis of 5 studies found that aflatoxin exposure is associated with a higher risk of liver cirrhosis, which could also lead to HCC (Mekuria, Routledge, Gong, & Sisay, 2020). Aflatoxin exposure and HBV infection can synergistically increase HCC risk up to 70% compared to aflatoxin (0.3–17.4%) or HBV (4.8–17.4%) alone (Kew, 2003).

2.5. Predisposing genetic factors

In addition to environmental factors, certain genetic factors also play a role in increasing HCC risk (Table 2). In most conditions, HCC is a secondary outcome of the underlying genetic condition in adulthood. These genetic changes are also predisposing and generally, interaction with a secondary risk factor is essential for HCC development.

Table 2.

A list of predisposing genetic conditions for HCC.

| Genetic condition | Gene(s) mutated | Type of study | Cirrhosis frequency | HCC frequency | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency | A1AT | Retrospective study of 17 autopsied patients with A1ATD | 5 of 17 | 8 of 17 | Eriksson, Carlson, and Velez (1986) |

| Retrospective analysis of clinical data from 246 A1ATD patients | 19% of patients with age over 50 | 12 of 91 deceased patients had liver disease | Larsson (1978) | ||

| Retrospective study of 31 autopsied patients with A1ATD | 13 of 31 | 5 of 31 | Elzouki and Eriksson (1996) | ||

| Retrospective study of 675 patients with end-stage liver disease | All patients | 4 of 47 A1ATD patients | Antoury, Lopez, Zein, Stoller, and Alkhouri (2015) | ||

| Autoimmune hepatitis | Multiple genes including DRB1, FAS, TNFA and CTLA4 | Meta-analysis of 25 studies with 6528 AIH patients | 92 of 93 patients with known cirrhosis status at diagnosis | 118 of 6528 | Lleo, de Boer, Liberal, and Colombo (2019) |

| Meta-analysis of 11 studies with 8460 AIH patients | 18.7% to 83.3% in Japan and 12% to 50.2% in other areas | 0–12.3% | Valean et al. (2019) | ||

| Hereditary hemochromatosis | Type 1 HH—HFE | Retrospective study of 163 patients with HH | 112 of 163 | 16 of 53 deceased patients had liver cancer | Strohmeyer, Niederau, and Stremmel (1988) |

| Prospective study of 208 HH patients | 80 of 208 | 16 of 208 | Bradbear et al. (1985) | ||

| Prospective study of 230 HH patients | 134 of 230 | 49 of 230 | Fracanzani et al. (2001) | ||

| population-based cohort study of 1847 HH patients | 20–25% | 49 of 1847 | Elmberg et al. (2003) | ||

| Glycogen Storage Disease | Type 1 GSD—glucose-6-phosphatase | Retrospective analysis of 72 GSD patients | Data not available | 4 of 72 | Jang et al. (2020) |

| Type III GSD—glycogen debranching enzymes | Systemic review of 45 GSD type III patients | 2 of 45 | 2 of 45 | Demo et al. (2007) | |

| Type VI GSD—glycogen phosphorylase | Case report of 2 patients with GSD-associated HCC | 0 of 2 | 2 of 2 | Manzia et al. (2011) | |

| Porphyria | Enzymes involved in heme biosynthesis | Retrospective population-based mortality study including 33 AIP | 4 of 33 | 9 of 33 | Andersson, Bjersing, and Lithner (1996) |

| Prospective study of 62 AIP gene carriers | 4 of 22 HCC patients | 22 of 62 | Innala and Andersson (2011) | ||

| A nationwide cohort study including 612 PCT patients (of which 23 were diagnosed with cancer prior to PCT) | 2 of 612 | 6 of 589 | Baravelli, Sandberg, Aarsand, and Tollanes (2019) | ||

| Prospective study of 83 PCT patients | 13 of 13 HCC patients | 13 of 83 | Salata et al. (1985) | ||

| Retrospective analysis of 245 AHP patients | 2 of 7 HCC patients | 7 of 206 | Kauppinen and Mustajoki (1988) | ||

| Prospective analysis of 650 AHP patients | 2 of 7 HCC patients | 7 of 605 | Andant et al. (2000) | ||

| Case report of 2 AP-related HCC patients | 1 of 2 | 2 | Schneider-Yin et al. (2010) | ||

| Tyrosinemia type 1 | Fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase | Retrospective study of 16 HT patients | 10 of 10 (with known cirrhosis status) | 4 of 16 | Ozcan et al. (2019) |

| Retrospective study of 16 HT patients | 16 of 16 | 12 of 16 | Seda Neto et al. (2014) |

2.5.1. Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency (A1ATD)

Alpha 1-antitrypsin (A1AT) belongs to the protein super family SERPIN (SERine Proteinase INhibitor). Members of this family are characterized by three beta sheets (A, B and C) and a mobile reactive loop that inhibits the target proteinase by presenting it a peptide sequence as a pseudo-substrates that are >30% homologous in their structure to each other (Topic, Ljujic, & Radojkovic, 2012). The primary role of A1AT is to inhibit the serine protease neutrophil elastase (NE), a major protease that cleaves a number of connective tissue substrates. It is an acute phase response, anti-inflammatory protein that blocks TNFα effects and is produced as a host response to tissue injury and inflammation (Stockley, 2015).

A1ATD is characterized by low levels of serum A1AT and affects 1:1800 to 1:2000 live births. It is the most common genetic cause of liver disease in children and increases risk for cirrhosis and HCC (Eriksson et al., 1986; Perlmutter, 2006). Lung disorders associated with A1AT occur due to a decrease in circulating A1AT and are attributed to a loss-of-function mechanism whereas liver abnormalities occur through a gain-of-toxic function mechanism (Ghouse, Chu, Wang, & Perlmutter, 2014). AT1ATD is associated with accumulation and polymerization of mutant A1AT in hepatocytes, mitochondrial dysfunction (Perlmutter, 2002; Teckman, An, Blomenkamp, Schmidt, & Perlmutter, 2004), delayed ER protein degradation (Wu et al., 1994) and altered regulation of cyclin D1 and melanoma cell adhesion molecule (MCAM) (Marcus et al., 2010).

2.5.2. Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH)

AIH is a chronic liver disease in which the body’s immune system attacks liver cells in genetically predisposed individuals. It is a polygenic, multifactorial disease that does not follow a typical inheritance pattern. AIH is linked to mutation in a human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II gene—DR beta 1 (DRB1), which is involved in antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells. Additionally, mutations in Fas cell surface death receptor (FAS), TNFA and cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4) genes are also linked to AIH (Liberal, Longhi, Mieli-Vergani, & Vergani, 2011). There are two main types of AH depending on what autoantigens are mediators of this disease. Type 1 AIH is seen in children and adults and characterized by the presence of anti-smooth muscle and antinuclear antibodies. Type 2 AIH is predominantly observed in children and characterized by anti-liver cytosol type 1 and/or anti-liver/kidney microsomal type 1 (anti-LKM1) antibodies (Sucher et al., 2019). The production of autoantibodies can be explained by a phenomenon termed “molecular mimicry.” For example, anti-LKM1 recognizes the autoantigen cytochrome P450IID6, which is molecularly similar to HCV antigens (Manns, Johnson, Griffin, Tan, & Sullivan, 1989; Zanger, Hauri, Loeper, Homberg, & Meyer, 1988). Prevalence of AH is 11–25/100,000 per year, with more women than men being affected. A meta-analysis of 11 studies indicate that the percentage of cirrhosis in AIH patients varies from 12% to 83% and 5–6% of AH patients develop HCC (Valean et al., 2019).

2.5.3. Hereditary hemochromatosis (HH)

Hemochromatosis is an iron overload disorder characterized by increased absorption of iron from the diet and accumulation of iron in organs like the liver, heart, pancreas and joints. There are two types of Hemochromatosis—hereditary/primary (which is further classified into types 1, 2, 3 and 4) and non-hereditary/secondary. Type 1 hereditary hemochromatosis is the most common (90%) hemochromatosis and is a result of mutations in the hemostatic iron regulator (HFE) gene (Radford-Smith, Powell, & Powell, 2018).

HFE encodes cell surface protein with a role in maintaining iron homeostasis by indirectly regulating the function of two proteins—ferroportin and transferrin. Ferroportin is an iron exporter found mainly in the intestinal epithelium where it transports absorbed dietary iron out of the cell and into the blood stream, increasing plasma iron concentration. Hepcidin is a protein that decreases iron delivery to plasma by binding to and destroying ferroportin. HFE regulates hepcidin expression through an unknown mechanism. In HH, HFE is mutated causing low levels of hepcidin, high ferroportin expression, increased iron uptake and systemic iron overload (Pietrangelo, 2006). Transferrin is the iron bound ligand of transferrin receptor 1 involved in cellular uptake of iron. HFE also binds to transferrin receptor 1 blocking its interaction with transferrin, preventing iron uptake by cells. In HH, there is increased uptake of iron by cells as a consequence of lack of functional HFE protein (Roy, Penny, Feder, & Enns, 1999). An increase in circulating iron levels and cellular uptake of iron leads to its deposition in various organs including the liver.

Iron overload can promote tumor growth by increasing cellular proliferation, cause DNA damage by increasing ROS levels and damage cell membranes of subcellular organelles through peroxidative damage (Bacon & Britton, 1989; Kowdley, 2004). Iron overload can also inhibit lymphocyte proliferation (Kowdley, 2004). Incidence of cirrhosis in HH patients is 10–25% and HCC incidence in HH patients is 8–10% (Kew, 2014) and the increase in risk for HCC development has been reported to be ~20-fold compared to healthy individuals (Elmberg et al., 2003).

2.5.4. Glycogen storage diseases (GSD)

Glycogen, a form of energy reserve for the body, is a branched polymer of linear chains of 8–12 glucose units linked by alpha (1→4) glycosidic bonds. GSDs are rare metabolic disorders involving glycogen synthesis or breakdown pathways. There are over 12 types of GSDs each due to deficiency of a different enzyme. The liver is the major site for glycogen metabolism and hence most affected by any error in the pathways. The most common types of GSDs are types I, III, and IV (Burda & Hochuli, 2015).

Type I or von Gierke’s disease is the most common form of GSD. This disease involves an autosomal recessive transmission with an incidence of 1 in 100,000 individuals (Ozen, 2007). There are four subtypes of Type I GSD—Type 1a, 1b, 1c and 1d, of which type 1a is the most common. People with type I GSD have a deficiency of the enzyme glucose-6-phosphatase, which is involved in breaking down glycogen to glucose (glycogenolysis) and synthesizing glucose from non-carbohydrates sources when glycogen reserves are depleted (gluconeogenesis). This enzyme is primarily present in the liver, kidney, and intestine and is involved in the terminal step, the conversion of glucose-6-phosphate to glucose, in both these pathways. Deficiency of this enzyme leads to severe hypoglycemia, due to low availability of glucose. Also, glucose-6-phosphate allosterically inhibits glycogen phosphorylase, the first enzyme in glycogenolysis, causing an accumulation of glycogen in the liver. Other biochemical abnormalities are lactic acidosis, hyperlipidemia and hyperuricemia. 57% and 8% of GSD type 1 patients develop hepatocellular adenoma and HCC, respectively (Jang et al., 2020). Autophagy impairment, mitochondrial dysfunction, metabolic reprogramming, oncogene activation and downregulation of tumor suppressors are potential mechanisms causing type 1GSD-related HCC (Bianchi, 1993; Cho, Lee, Bae, & Chou, 2020). Animal models of this disease did not develop cirrhosis (Resaz et al., 2014).

Type III, Cori disease, or Forbes disease is an autosomal recessive disease with an incidence of 1 in 100,000 individuals, initiated by a deficiency of the glycogen debranching enzymes—glucosyltransferase and glucosidase (Ozen, 2007). There are two subtypes—type IIIa (~80% of cases) where enzyme deficiency occurs in liver and muscle and type IIIb where only the liver is involved. Glycogen is a branched molecule with α-1,6 glycosidic bonds at branch points. Since the enzyme glycogen phosphorylase can only act on α-1,4 bonds, during glycogen breakdown a debranching enzyme removes the α-1,6 glycosidic bond leaving a linear chain for glycogen phosphorylase to continue the break down process. Deficiency of this enzyme leads to accumulation of short chain length branched glycogen molecules in the liver and muscles. Liver involvement in this condition is limited and the major cause of morbidity is muscle diseases in early adulthood (Kishnani et al., 2010). There have been isolated reports of liver cirrhosis in type III GSD patients, with less than 10 cases of HCC reported overall (Demo et al., 2007).

Type VI or Hers disease is an extremely rare condition with unknown prevalence, except in older Mennonite population where the disorder has a prevalence of 1:1000 (Ozen, 2007). It is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by a defect in the glycogenolysis enzyme glycogen phosphorylase. Symptoms of this disorder include hepatomegaly, poor growth, ketonic hypoglycemia, elevated hepatic transaminases, hyperlipidemia and low prealbumin level. There are limited reports of HCC development in type VI GSD patients. However, there is evidence that while rare, these patients can develop HCC. Also, fibrosis is more common than cirrhosis in these patients (Manzia et al., 2011).

2.5.5. Porphyria

Porphyrin is a compound formed of four modified pyrrole subunits interconnected at their alpha carbon atoms by methine bridges. Heme is chemically a protoporphyrin, a type of porphyrin, linked to an iron molecule. Porphyria represents a group of rare mostly genetic disorders caused by a deficiency of enzymes involved in heme biosynthesis, causing an accumulation of porphyrins and porphyrin precursors in the body. It can be broadly classified into acute and cutaneous porphyria. Acute porphyria (AP) causes sudden attacks of severe abdominal pain that can last for several days and primarily affects the nervous system. The subtypes of APs are acute intermittent porphyria (AIP), variegate porphyria (VP), aminolevulinic acid dehydratase deficiency porphyria (ALAD) and hereditary coproporphyria (HCP), each uniquely characterized by deficiency of a different enzyme. Non-acute or cutaneous porphyrias primarily cause blistering, swelling, reddening, itching and scarring of the skin as a result of exposure to sunlight. Their subtypes are X-linked dominant protoporphyria (XLDPP), congenital erythropoietic porphyria (CEP), porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) and erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP). Porphyria can also be classified into acute hepatic porphyria (AHP) and erythropoietic porphyria, based on the origin of excess precursors. AIP, PCT, HCP and VP are hepatic, with precursors originating in the liver and CEP and EPP are erythropoietic, where precursors originate in the bone marrow (Ramanujam & Anderson, 2015).

AHP are specifically associated with increased risk for HCC. They are autosomal dominant traits and one mutant allele is sufficient to reduce enzyme levels to 50%. However, other susceptibility factors like viral infections, alcohol abuse, HFE mutations or smoking are required to display the disease phenotype since more than a 50% decrease in enzyme activity is required to manifest this phenotype. Since these additional susceptibility factors in themselves can cause HCC, proper controlled studies are required to estimate the actual incidence and increased risk associated strictly with AHP (Gisbert et al., 2004). AHP patients have a 35-fold increased risk of developing HCC (Lang, Schafer, Schwender, Neumann, & Frank, 2015) and the incidence rate for AHP-related HCC is 0.16–0.35% (Peoc’h et al., 2019). PCT patients have abnormal liver enzymes and histological abnormalities. A 20-fold increase in risk for HCC (Baravelli et al., 2019) has been reported and a study with 39 patients reported 0.26% incidence per year. HCC was found in 4–27% of AIP patients (Andersson et al., 1996) and 1.3–5.4% of VP patients.

2.5.6. Tyrosinemia type 1

Hereditary Tyrosinemia type 1 (HT1) is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder resulting from a deficiency in the enzyme fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase, which breaks down 4-fumarylacetoacetate (FAA) and water into acetoacetate, fumarate, and H+ in the ultimate step of tyrosine breakdown (Bergeron, D’Astous, Timm, & Tanguay, 2001). FAA and associated toxic metabolites accumulate in the liver and cause severe liver dysfunction. Treatment for this condition involves 2-(2 nitro-4–3 trifluoro-methylbenzoyl)-1, 3-cyclohexanedione (NTBC), which is a compound that blocks the tyrosine catabolic pathway at an earlier step preventing the accumulation of most toxic metabolites. However, accumulation of tyrosine and phenylalanine (a precursor for tyrosine) still occurs which needs to be regulated through diet. Reports of HCC development have been observed in untreated patients or patients treated with NTBC after symptoms develop. If treated asymptomatically, HCC development in tyrosinemia type 1 patients can be prevented. However, the lack of newborn screening and NTBC availability still causes HCC due to untreated HT1 (van Ginkel, Pennings, & van Spronsen, 2017).

Twenty-five to 75% of HT1 positive individuals developed HCC (Ozcan et al., 2019; Seda Neto et al., 2014). In untreated patients, oxidative stress, inhibition of DNA repair enzymes, ER stress, Golgi complex disruption, and apoptosis resistance are some of the potential mechanisms for HCC development (Tanguay, Angileri, & Vogel, 2017).

3. Liver cancer staging

Liver cancer staging is the process of classifying liver cancer based on various factors. It helps determine the severity of the disease, potential prognosis and the best treatment plan after diagnosis. There are more than 18 staging systems, each with a different purpose and their own advantages and disadvantages. For example, Okuda and CLIP are score-based staging systems to predict survival whereas BCLC guides treatment decision. In addition to liver cancer staging systems, scoring systems like Child-Pugh and MELD are used to assess liver function.

3.1. Child-Pugh (CP) score

Child-Pugh or Child-Pugh-Turcotte scoring system was introduced in 1964 to classify patients undergoing liver decompression surgery for portal hypertension based on hepatic function to predict survival (Child & Turcotte, 1964; Pugh, Murray-Lyon, Dawson, Pietroni, & Williams, 1973). It was modified in 1973 to substitute the variable clinical nutritional status with prothrombin time (Pugh et al., 1973). The updated version uses blood albumin level (>35 g/L, 28–35 g/L, <28 g/L), blood bilirubin level (<2, 2–3, >3), presence or absence of ascites (absent, slight, moderate), encephalopathy grade (absent, grade 1–2, grade 3–4) and prothrombin time (<4s, 4–6s, >6s) to classify patients. Each variable can be scored 1, 2 or 3 with 1 indicating normal hepatic function and 3 indicating a compromised liver. The severity of cirrhosis is estimated based on the cumulative score—higher the score, worse the cirrhosis. A score of 5–6 is designated Child-Pugh A, 7–9 is Child-Pugh B and 10–15 is Child-Pugh C.

3.2. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD)

MELD was introduced in 2000 to predict survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt procedure for portal hypertension (Malinchoc et al., 2000). The risk score in this method was calculated from 4 prognostic values—bilirubin level, creatinine level, International Normalized Ratio (INR), derived from prothrombin time and cause of cirrhosis. [0.957 × Log e (creatinine mg/dl) + 0.378 × Log e (bilirubin mg/dl) + 1.120 × Log e (INR) + 0.643 × 10, rounded off to the nearest integer].

Prior to 2002, the United Network for Organ Sharing which administers the national Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, used Child-Pugh score to determine which patient qualified to receive an available donor liver. CP score is categorical and classified patients based on their liver function into status 1, 2A, 2B and 3. Within category 3 which had the sickest patients, priority was given to patients who had been on the list the longest. Hence, there was a good chance that a person that had the greatest need for a liver transplant might not receive it because they were added to the list at a later time. To overcome this problem, the CP score was replaced by the MELD score in 2002 (Freeman et al., 2002). In 2006, the MELD score was updated to include serum sodium levels and referred to as MELD-Na (Biggins et al., 2006). Another model called Albumin-Bilirubin (ALBI) score was introduced in February 2015 and uses serum albumin and bilirubin levels to assess liver function (Johnson et al., 2015).

3.3. Tumor node metastasis (TNM) system

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) developed the TNM staging system for multiple cancers. The first edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual was released in 1977. However, criteria for liver cancer staging was included only in the second edition in 1983. The most recent is the 8th edition of AJCC cancer staging manual, published in 2016. This is the most commonly used system in the US and includes tumor size (T), nodal involvement (N) and metastatic status (M), to stage liver cancer.

T refers to tumor size and can fall into one of the three categories (T1, T2, T3 and T4). T1 refers to a single tumor that has not grown into blood vessels. It is subcategorized based on tumor size into T1a (≤2 cm) or T2a (>2 cm). T2 refers to either a single >2-cm tumor that has grown into blood vessels or more than one tumor with maximum tumor size <5-cm. More than one tumor, with at least one tumor larger than 5-cm across is considered as T3 and T4 refers to any tumor that has grown into the hepatic or portal vein. Cancer can spread through the bloodstream to distant organs or through the lymphatic system to lymph nodes. N refers to nearby nodal involvement and can fall into one of the two types—N0 when the tumor has not spread and N1 when the tumor has spread to nearby lymph nodes. M indicates the state of metastasis. M1 and M0 refer to a tumor that has spread and not spread to distant organs, respectively.

Different combinations of T, N and M are classified into the following stages—I A (T1a, N0, M0), I B (T1b, N0, M0), II (T2, N0, M0), III A (T3, N0, M0), III B (T4, N0, M0), IV A (Any T, Any N, M0) and IV B (Any T, Any N, M1). Each revision of TNM staging system is based on evaluations done on current guidelines. The current version is based on two studies that indicated there was a need to subclassify T1, which was not subclassified in the previous edition, into T1a and T1b (Shindoh et al., 2013) and that there was no difference in survival between patients with T3a and T3b tumors or between those with T3b and T4 tumors (Chan et al., 2013). Evaluation of the current system suggests that it is better in predicting patient prognosis than the previous version, but also points that a sub-stratification of T2 group would help the system perform better (Kamarajah, Frankel, Sonnenday, Cho, & Nathan, 2018). A disadvantage of the TNM classification is that it includes only tumor characteristics and does not include liver function parameters.

3.4. The Okuda system

The Okuda classification was introduced in 1984 in Japan to predict prognosis in relation to disease stage and treatment (Okuda et al., 1984). The following four criteria were used for the classification—presence of ascites, tumor ≥50% of the 2-dimensional size of the liver, serum albumin ≤30 g/L, serum bilirubin ≥3 mg/dL. A person that does not meet any of the above criteria is classified as stage 1, 1 or 2 criteria is stage 2 and >3 criteria is stage 3.

3.5. Cancer of the liver Italian program (CLIP) system

The CLIP system was introduced in 1998 to produce a more sensitive prognostic index for HCC patients (A new prognostic system, 1998). CLIP score is calculated by assigning a score between 0 and 2 to four clinical factors Child-Pugh stage (A = 0, B = 1, C = 2), AFP (<400 ng/dL = 0, ≥ 400 ng/dL = 1), presence of portal vein thrombosis (no = 0, yes = 1) and tumor morphology (uninodular and extension ≤50% of the liver = 0, multinodular and extension ≤50% = 1 and massive or extension >50% = 2). These scores are added together to yield a CLIP score of 0–6, each score is linked to an estimated survival—0 = 42.5 months, 1 = 32.0 months, 2 = 16.5 months, 3 = 4.5 months, 4 = 2.5 months and 5–6 1 month.

3.6. Barcelona clinic liver cancer (BCLC) system

The BCLC system was proposed by the BCLC group from University of Barcelona in 1999 to classify HCC patients into 5-stages and link each HCC stage to a treatment option (Llovet, Bru, & Bruix, 1999). In addition to CP score and tumor size, BCLC uses the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale to evaluate performance status (PS). PS can range from PS 0 where a person is fully active to PS4 where a person is in a chair or a bed all the time and needs complete care. There are 5-stages to the BCLC staging system. Stage 0 indicates very early stage, where the tumor is <2 cm, PS 0 and CP score A. Stage A indicates early stage, with one tumor of any size or up to 3 tumors all <3 cm, PS 0 and CP score A or B. Surgical ablation is the treatment option with best outcome for BCLC stages 0 and A. Stage B is intermediate stage with >3 tumors, PS 0, CP A or B and recommended Trans-Arterial Chemoembolization (TACE). Stage C is advanced with spreading of cancer into blood vessels, lymph nodes or other organs, PS 1 or 2 and CP A or B. Systemic therapy is recommended for these patients. Stage 4 is severe liver damage with CP C and PS 3 or 4, without any treatment except best supportive care.

4. Molecular classification of HCC

HCC staging is a classification based on tumor morphology and various clinical parameters to determine treatment with the most favorable outcome and patient prognosis. Despite belonging to the same HCC stage, tumors with different molecular signatures can respond differently to the same treatment. Although challenging due to molecular heterogeneity, various studies have classified HCC into a finite number of molecular categories, primarily using sequencing techniques (Table 3, Fig. 3). Molecular classification of HCC has a similar objective as HCC staging, but is based on differences at the molecular level. It can also help develop subtype-specific targeted HCC therapies.

Table 3.

An overview of various established HCC molecular classification systems.

| Type of classification | HCC classes | Basis for classification | Samples | Techniques | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene-signature based classification | G1–G6 | Loss of heterozygosity, gene mutations, promoter methylation of CDH1 and CDKN2Aand HBV DNA copy | 57 HCCs and 3 hepatocellular adenomas. 63 additional HCCs (for validation) | Genome wide transcriptome microarray and unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis | Boyault et al. (2007) |

| Class 1—5 | Hierarchical clustering of gene expression data | 103 tumor samples From transplant patients | Single-nucleotide polymorphism arrays, statistical analysis of copy number alterations, fluorescence in-situ hybridization, tissue microarrays | Chiang et al. (2008) | |

| EpCAM+ AFP+, EpCAM+ AFP−, EpCAM− AFP+, EpCAM− AFP− | AFP and EpCAM expression | 40 HCC samples.349 HCC samples (for validation) | cDNA microarray, oligonucleotide microarray and immunohistochemical analyses | Yamashita et al. (2008) | |

| S1–S3 | Expression of meta-analysis marker genes | 603 patients from eight independent cohorts | Subclass mapping (SubMap), gene set enrichment analysis, microarray (for validation) | Hoshida et al. (2009) | |

| Subtype A–D | Expression of top differentially expressed genes | 373 HCC samples and 50 controls | Differential gene expression analysis, enrichment analysis and gene–gene interaction | Agarwal, Narayan, Bhattacharyya, Saraswat, and Tomar (2017) | |

| iClust 1–3 | Unsupervised clustering of data from five platforms | 363 hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) samples from various institutes | Whole exome sequencing, DNA copy number analysis, methylation profiling, mRNA-seq, miRNA-seq, and proteomic analysis | Wheeler and Roberts (2017) | |

| Metabolic classification | iHCC 1–3 | Expression status of stratifying metabolic genes identified in this study | Transcriptomics and clinical data of 369 HCC and 50 matched noncancer liver samples (TCGA) | “Functional” gene–gene networks-based characterization | Bidkhori et al. (2018) |

| C1–C3 | Gene expression profile of metabolic genes | Metadata set with 371 and 231 HCC samples from TCGA and the International Cancer Genome Consortium, respectively | Subsequent non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) clustering, gene set variation analysis, microenvironment cell population-counter to estimate immune filtration | Yang, Huang, Liu, Qin, and Wang (2020) | |

| Immunological classification | Immune-high, Immune-mid and Immune-low | Immune cell infiltration pattern | 158 samples from 141 patients | Multiplex IHC and cluster analysis | Kurebayashi et al. (2018) |

| Immunocompetent, Immunodeficient and Immunosuppressive | Tumor microenvironment including immune status, chemokines/cytokines and cell metabolism | 42 samples from eight HCC patients | Whole-exome sequencing, RNA-seq, quantitative proteomics by multiplexed tandem mass tag (TMT) MS, untargeted metabolomics by liquid chromatography (LC)-MS/MS, CyTOF analysis of immune cells | Zhang et al. (2019) | |

| Type I to IV | Tumor budding assessment and immune scores | 423 resected HCC samples | Tumor budding evaluation, Immunohistochemistry and hematoxylin-eosin staining, Whole-exome sequencing | Wei et al. (2020) | |

| Chromosomal classification | Poorly polyploid and highly polyploid | Percentage of polyploid hepatocytes | 75 tumor and non-tumor tissue pairs from HCC surgery patients and 13 normal liver samples | ImageJ quantification of cellular and nuclear ploidy | Bou-Nader et al. (2020) |

Fig. 3.

An overview of various molecular classification systems for HCC. For each classification system, the subgroup with better prognosis and worse prognosis are shaded yellow and gray, respectively. Correlating subgroups between multiple classification systems are connected using dotted lines. Created with Created with https://biorender.com.

4.1. Gene signature-based classification of HCC

High-resolution copy number analysis of 125 HCC tumors followed by validation using whole exome sequencing of 24 tumors and matched normal livers revealed 5 pathways that were frequently altered in HCC. The WNT/β-catenin pathway was mutated in 49.6% of tumors with three mutually exclusive mutations Catenin Beta 1 (CTNNB1) 32.8%, Axis inhibition protein 1 (AXIN1) 15.2% and adenomatous polyposis coli protein (APC) 1.6%. The second pathway most frequently mutated was p53 signaling in 28.8% of samples, specifically mutations in TP53 gene inactivation (20.8%) or cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) 8%. Genes in chromatin remodeling complex (>24%) were the next frequently mutated, with AT-rich interaction domain (ARID) 1A and ARID2 mutations in 16.8% and 5.6% of samples. 9.6% of samples had a mutation in the ribosomal protein S6 kinase A3 (RPS6KA3) gene, a kinase in Ras/MAPK signaling pathway. Nuclear factor, erythroid 2 like 2 (NFE2L2), a transcription factor involved in maintaining cellular redox homeostasis was mutated in 6.4% of HCC tumors. This mutation was present with CTNNB1 mutations, potentiating alterations of the oxidative stress pathway in WNT/β-catenin signaling (Guichard et al., 2012).

4.1.1. G1–G6 classification

Boyault. et al. suggested an HCC classification system based on genome wide transcriptome microarray and unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis of 123 tumors (Boyault et al., 2007). A combination of 16 gene signatures were used to classify HCC into 6 groups G1–G6. G1 group was associated with genes expressed during development (Myosin Heavy Chain 4, SRY-Box Transcription Factor 9), paternally imprinted genes (Insulin Like Growth Factor 2, Paternally-expressed gene 3, Paternally-expressed gene 10 and Sarcoglycan Epsilon) and high alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) expression and G2 with mutations in the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) gene. Both G1 and G2 have AXIN1 gene mutations and are related to HBV infection. However, G1 samples were associated with low and G2 with high copy numbers of viral DNA. G3 over-expresses genes implicated in cell cycle control including genes encoding cyclins, cell cycle checkpoint and DNA replication checkpoint proteins and has CDKN2A promoter hypermethylation. The G4 cluster comprised of the 5 samples of non-tumorous liver tissues, the 3 hepatocellular adenoma and 2 HCCs and had a T cell factor 1 (TCF1) mutation. G5 shows down-regulation of genes involved in stress and immune response. G6 tumors showed an overexpression of lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1 (LEF1), downregulation of E-cadherin, under expression of cadherin 1 (CDH1) and presence of satellite nodules around the principal tumor (Boyault et al., 2007).

In addition to the 6 classes mentioned above, the system classifies HCCs broadly into tumors with chromosomal instability (G1–G3) or chromosomal stability (G4–G6), TP53 mutated (G2–G3), CTNNB1 mutated (G5–G6) or neither mutated (G1, G4) and AKT activated (G1–G2), WNT activated (G5–G6) or neither activated (G3–G4). Unfortunately, none of the classification systems in this study were able to predict survival. However, they can act as a tool to identify patients for targeted therapy (Boyault et al., 2007). After almost a decade, the same group validated the system in another cohort and correlated the molecular alterations to HCC phenotype (Calderaro et al., 2017). CTNNB1 mutated tumors were larger, well differentiated, cholestatic, without inflammatory infiltrates and associated with intact tumor capsule and areas of micro-trabecular and pseudo-glandular histological patterns. TP53 tumors, on the other hand, were poorly differentiated, non-cholestatic, pleomorphic, multinucleated and associated with macrovascular and microvascular invasion, areas of compact histological pattern and foci of sarcomatous changes. The tumors were also associated with WHO histological classification of HCC. G1 tumors were associated with a progenitor phenotype, G3 with macro-trabecular massive subtype and G4 with steatohepatitic subtype (Calderaro et al., 2017).

This classification system was validated in other cohorts. Transcriptome analysis of 82 samples from Singapore assembled patients into similar groups using the same gene signatures. Although the distribution of patients in the 6 groups was different, overall the results were concordant. This study further examined at distinct clinical features of groups and found that subgroup G3 strongly associated with microvascular invasion (Allen. et al., 2016). Similarly, 205 Korean HCC samples were classified into the six subgroups and similar molecular characteristics were observed (Ahn et al., 2018).

4.1.2. Class 1–5 classification

Microarray analysis of gene expression profiles of 91 HCCs revealed 4 gene expression classes. Class 1 had high prevalence of CTNNB1 mutations. The tumors were >3 cm in size and several liver-specific marker genes were overexpressed. Class 2 tumors had increased proliferation, high AFP, chromosomal instability (4q loss, 13q loss and 6q loss) and insulin like growth factor (IGF) 1 receptor, ribosomal protein S6 (RPS6) and Akt phosphorylation. Class 3 tumors had lower expression of IGF2, CTNNB1 target genes, over-expression of ISG marker genes and associated with tumors <3 cm. Class 4 tumors contained polysomy of chromosome 7 and high expression of genes in this region like Cordon-Bleu WH2 repeat protein (COBL), claudin 15 (CLDN15), mitotic arrest deficient 1 like 1 (MAD1L1), DNA polymerase delta 2 (POLD2) and ephrin type-A receptor 1 (EPHA1). These tumors also lacked chromosome 8q gains. Class 5 consists of a group of unannotated tumors. The prognostic significance of this classification was not determined (Chiang et al., 2008).

4.1.3. EpCAM- and AFP-based classification

Epithelial cellular adhesion molecule (EpCAM) is a cell-cell adhesion molecule highly expressed in embryonic liver and hepatic stem cells (de Boer, van Krieken, Janssen-van Rhijn, & Litvinov, 1999; Schmelzer, Wauthier, & Reid, 2006). Mature hepatocytes lack EpCAM expression (de Boer et al., 1999; Schmelzer et al., 2006) whereas premalignant livers (Kim et al., 2004) and 35% of HCC patients express EpCAM (de Boer et al., 1999; Kim et al., 2004; Ruck, Wichert, Handgretinger, & Kaiserling, 2000; Schmelzer et al., 2006). Although controversial, AFP is the most commonly used serum biomarker for HCC and expressed in 60% of HCC patients (Trevisani et al., 2001).

Gene signatures associated with EpCAM expression were identified using microarray analysis of 40 primary HCC tissues (Yamashita et al., 2008). Over-expressed genes in EpCAM-positive tumors were associated with organ development and protein synthesis and linked to the signaling networks of nine genes caldesmon 1 (CALD1), CTNNB1, epidermal growth factor (EGF), insulin (Ins)-1, N-Myelocytomatosis (MYCN), myogenic differentiation 1 (MYOD1), PPARA, transforming growth factor (TGF) beta 1, and TP53. Similarly, genes involved in mature hepatocyte functions, such as lipid metabolism and drug metabolism, were down regulated by five genes [NFE2L2, UDP glucuronosyltransferase family 1 member A6 (UGT1A6), transcription factor T cell factor 1 (TCF1), hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 Alpha (HNF4A), and plasminogen (PLG)]. EpCAM+ and EpCAM− tumors were further stratified based on the expression of AFP into EpCAM+ AFP+, EpCAM+ AFP−, EpCAM− AFP+ and EpCAM− AFP−. Although gene signatures of these four groups were not studied, morphological differences between them were. EpCAM+ AFP+, EpCAM+ AFP−, EpCAM− AFP+, EpCAM− AFP− resembled hepatic stem cells, bile duct epithelial cells, hepatocyte progenitors and mature hepatocytes, respectively. EpCAM+ AFP+ and EpCAM− AFP+ groups correlated with poor prognosis whereas EpCAM− AFP− and EpCAM+ AFP− groups corresponded to intermediate and good prognosis, respectively (Yamashita et al., 2008). This classification was validated in three independent cohorts using cDNA microarray, oligonucleotide microarray, and immunohistochemistry. This classification can be used to determine prognosis and targeted therapy.

4.1.4. S1–S3 classification

Meta-analysis of gene expression data from 603 patients from nine independent patient cohorts from around the world by Hoshida et al. revealed three HCC subclasses termed S1, S2 and S3 (Hoshida et al., 2009). S1 tumors are characterized by TGF-β activation causing β-catenin to be localized in the cytoplasm resulting in WNT activation. These tumors also showed more vascular invasion and satellite lesions and associated with risk of early recurrence. S2 tumors exhibited suppression of interferon-target genes, activation of MYC and AKT signaling and high levels of AFP expression. This group also consisted of the largest tumors in the cohort. S3 tumors were the smallest, included most of the well-differentiated tumors, had activation of p53 and p21 target genes and associated with good survival. This classification has been validated in multiple cohorts in this study, has prognostic value and can be used for targeted therapy.

4.1.5. A–D classification