Nadine Denize Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

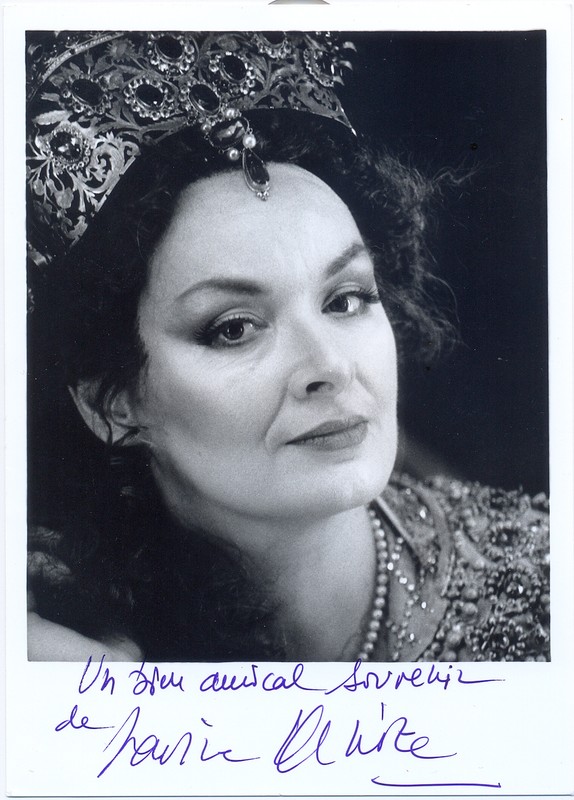

Mezzo - Soprano Nadine Denize

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Since making her debut at the Opéra de Paris, Nadine Denize (born in Rouen November 6, 1943) has become one of the most prominent exponents of the French lyric repertoire all over the world

She studied at the conservatoire à rayonnement régional de Rouen, in Marie-Louise Christol's class, and entered the conservatoire de Paris (rue de Madrid) in Camille Maurane's class at age eighteen. She won a First prize and was hired by the Paris opera. She sang small roles for two years, then was cast as Cassandra in Berlioz's LES TROYENS and Marguerite in LA DAMNATION DE FAUST.

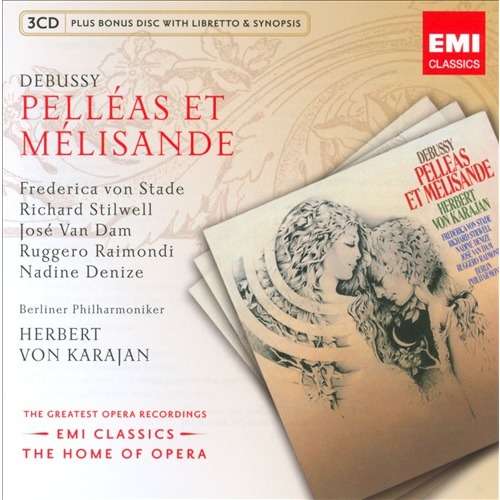

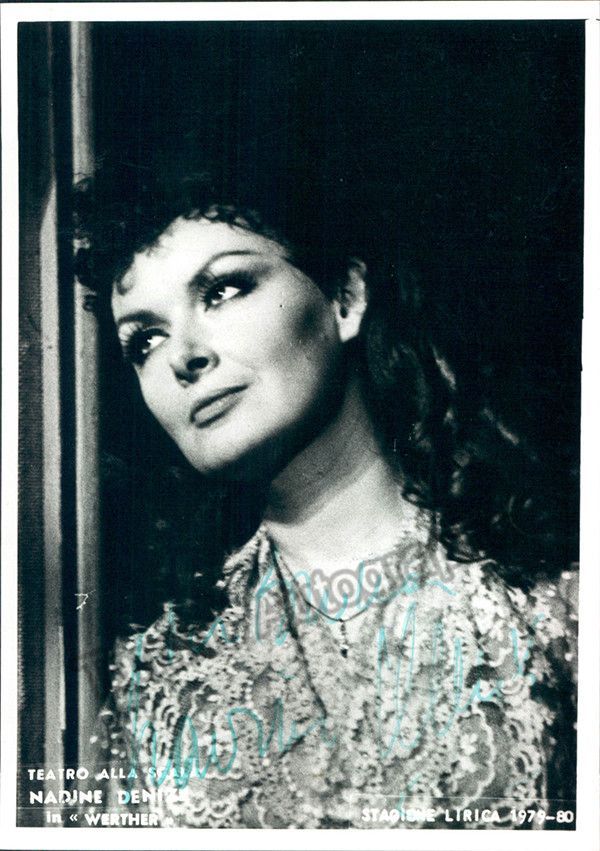

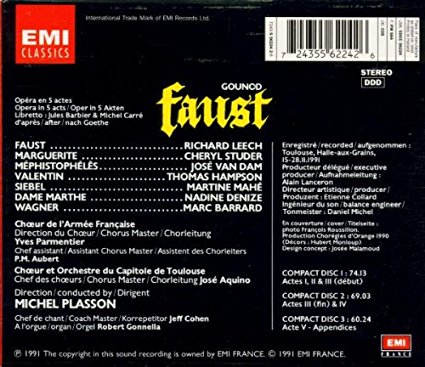

Her roles include many of the major dramatic mezzo soprano roles, such as Charlotte WERTHER (with Alfredo Kraus and Georges Prêtre at la Scala), Cassandre LES TROYENS (La Scala with Georges Prêtre, Chicago with James Levine) and Didon in the same piece at the Berlioz Festival in Saint Etienne under Serge Baudo. She has also appeared in CARMEN (Arena di Verona, Paris, Toronto, Hamburg, Santiago Chile), LA DAMNATION DE FAUST (Spoleto Italy, Berlin), SAMSON ET DALILA and DIALOGUES DES CARMELITES (Mère Marie in Paris and Toronto, La Première Prieure in Savonlinna and London), PELLÉAS ET MÉLISANDE (recording with Herbert von Karajan, Paris, Salzburg, Scala with Prêtre) and LOUISE (Marseille, Strasbourg).

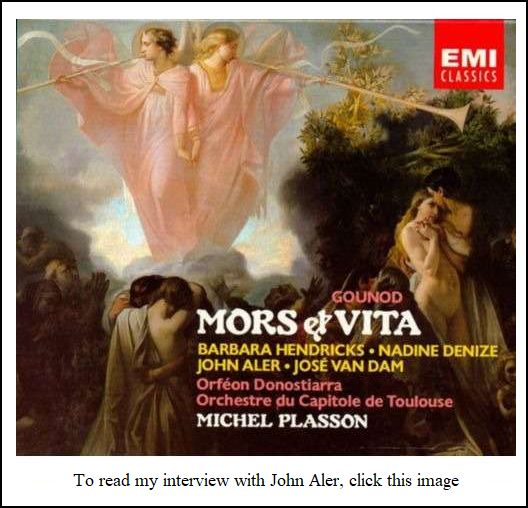

See my interviews with Richard Stilwell, José van Dam, Ruggero Raimondi,

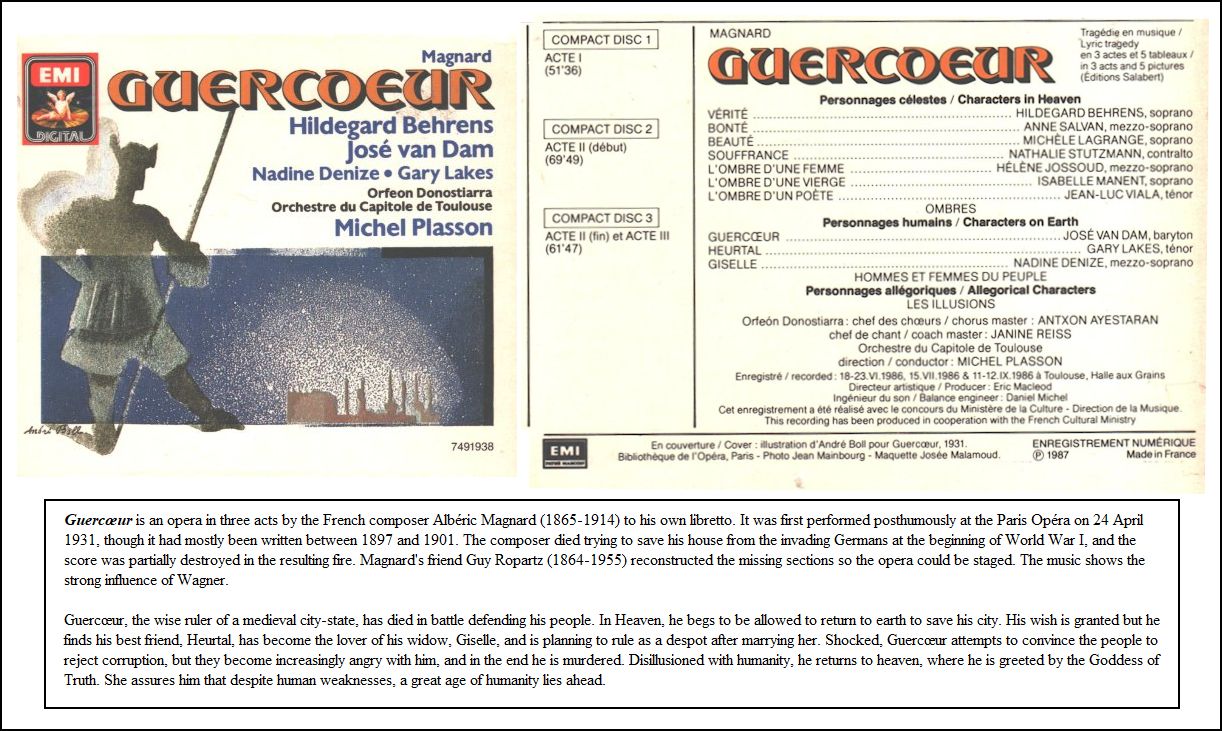

and Janine Reiss (language coach on this recording and others)

She sang the major roles of the Italian repertoire with great success, particularly Eboli DON CARLO with Mirella Freni and Nicolai Ghiaurov under Claudio Abbado at la Scala, in Vienna and Berlin (among others), Santuzza CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA (Strasbourg, Düssseldorf), Federica LUISA MILLER (Paris with Luciano Pavarotti and Katia Ricciarelli), Neris MEDEA with Leonie Rysanek in Aix-en-Provence, with Shirley Verrett in Paris under Pinchas Steinberg, just to name a few.

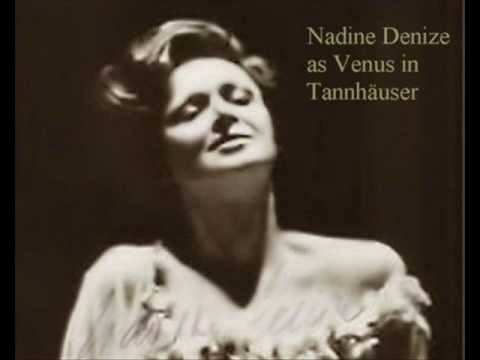

The German repertoire has also occupied a significant place in Denize's career. She was a remarkable Kundry PARSIFAL at the Opéra de Paris under Horst Stein with Jon Vickers, sang Venus TANNHÄUSER (Berlin, Bonn), Brangäne TRISTAN UND ISOLDE (Berlin, Paris, Chicago, under Ferdinand Leitner for the last full Tristan of Jon Vickers, Monte Carlo, Maggio Fiorentino), Fricka RHEINGOLD (Vienna, Münich, Paris, Chorégies d'Orange under Rudolf Kempe) and DIE WALKÜRE (Geneva, Münich with Wolfgang Sawallisch, San Francisco with Birgit Nilsson, Leonie Rysanek and Jess Thomas), Ortrud LOHENGRIN (Marseille, Lyon, Strasbourg), Waltraute GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG (at Radio France with Giuseppe Patané), Octavian DER ROSENKAVALIER (Strasbourg, Vienna), Die Amme DIE FRAU OHNE SCHATTEN (Geneva), Herodias SALOME (Festival de Radio France in Montpellier, Leipzig), Klytämnestra ELEKTRA (Nantes), Malik in Henze's L'UPUPA (Lyon) and The Mother HÄNSEL UND GRETEL (Geneva, Leipzig).

The German repertoire has also occupied a significant place in Denize's career. She was a remarkable Kundry PARSIFAL at the Opéra de Paris under Horst Stein with Jon Vickers, sang Venus TANNHÄUSER (Berlin, Bonn), Brangäne TRISTAN UND ISOLDE (Berlin, Paris, Chicago, under Ferdinand Leitner for the last full Tristan of Jon Vickers, Monte Carlo, Maggio Fiorentino), Fricka RHEINGOLD (Vienna, Münich, Paris, Chorégies d'Orange under Rudolf Kempe) and DIE WALKÜRE (Geneva, Münich with Wolfgang Sawallisch, San Francisco with Birgit Nilsson, Leonie Rysanek and Jess Thomas), Ortrud LOHENGRIN (Marseille, Lyon, Strasbourg), Waltraute GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG (at Radio France with Giuseppe Patané), Octavian DER ROSENKAVALIER (Strasbourg, Vienna), Die Amme DIE FRAU OHNE SCHATTEN (Geneva), Herodias SALOME (Festival de Radio France in Montpellier, Leipzig), Klytämnestra ELEKTRA (Nantes), Malik in Henze's L'UPUPA (Lyon) and The Mother HÄNSEL UND GRETEL (Geneva, Leipzig).

Denize has also appeared in several important roles of the Russian and Czech repertoire such as Larina EUGEN ONEGIN, Countess PIKOVAYA DAMA, Kostelnička JENŮFA and Kabanicha KÁT'A KABANOVÁ (Geneva with Jiří Bĕlohlávec).

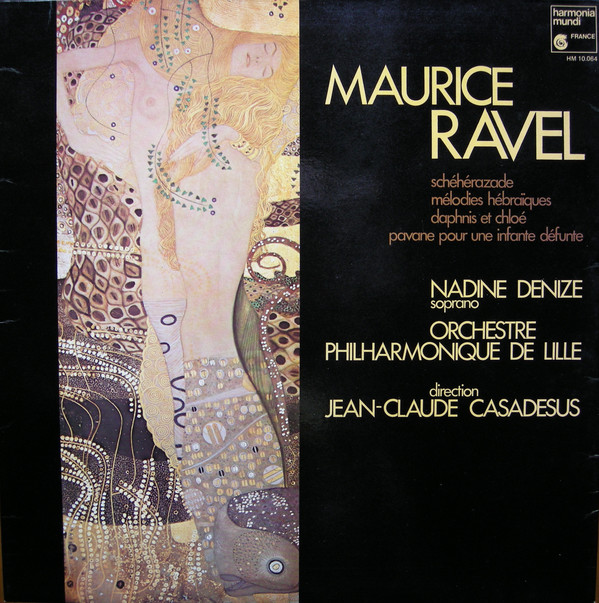

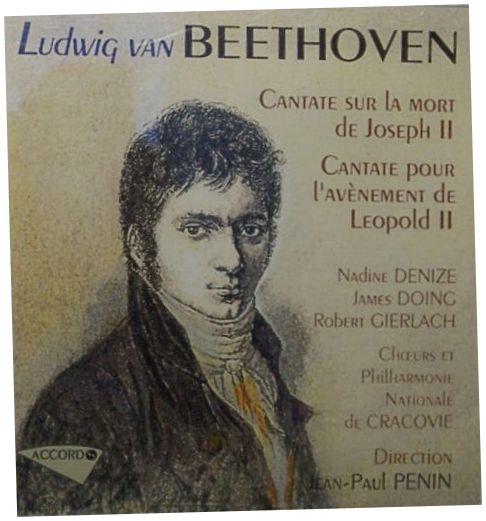

Miss Denize is regularly present on the concert platform, where she sings with the most prestigious orchestras all over the world. She has performed works such as Beethoven MISSA SOLEMNIS, the major works of Berlioz, Berg SIEBEN FHÜHE LIEDER, Duruflé REQUIEM, Chausson LE POEME DE L'AMOUR ET DE LA MER, Mahler Symphonies and Cycles; Ravel SHÉHÉRAZADE, Schönberg GURRELIEDER, Stravinsky LES NOCES and LE ROSSIGNOL and Wagner WESENDONCK LIEDER.

She has performed under the baton of the world's great conductors including Gerd Albrecht, Karl Böhm, Pierre Boulez, Myung Whun Chung, Colin Davis, Sylvain Cambreling, Christoph von Dohnányi, Eliahu Inbal, Armin Jordan, Marek Janowski, Alain Lombard, Seiji Ozawa, Lorin Maazel, Sir Charles Mackerras,Michel Plasson,Mstislav Rostropovitch, Sir Georg Solti, Yuri Temirkanov and Karl Tennstedt. She has also participated in numerous recordings.

-- Names which are links in this box and throughout this page refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

In the fall of 1982, Nadine Denize was appearing with Lyric Opera of Chicago as Brangaene in Tristan und Isolde with Jon Vickers, Janis Martin, Siegmund Nimsgern, Hans Sotin, Gualtiero Negrini, andTerry Cook, conducted by Ferdinand Leitner. It was her only appearance with the company, though she had sung Cassandre in Les Troyens at the Ravinia Festival, the summer home of the Chicago Symphony, in 1978, and would return to downtown Chicago in November of 1985 for Act II of Tristan with René Kolo and Johanna Meier, and Daniel Barenboim conducting the CSO. Incidentally, the other two days of the weekend series of concerts had Barenboim conducting orchestral music of both Wagners – Vater und Sohn!

Miss Denize says the music of Hector Berlioz is harder to sing than Wagner. “Wagner is long, and has a big orchestra, but Berlioz is so intense.” She says she is more tired at the end of a Berlioz evening than at the end of a Wagner evening.

It was in the fall of 1982, when she was singing Brangäne for the first time, that I had the pleasure of speaking with Miss Denize. We talked about quite a number of subjects

— her French operas as well as Wagner. The first section of the interview was transcribed and posted in Wagner News in October of 1985, to herald the CSO performances. We then moved over to the French repertoire. Portions of the interview were aired on WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago along with some of her recordings. Now the entire encounter has been transcribed and presented on this webpage.

My thanks to Alfred Glasser, Director of Education at Lyric Opera, for providing the translation for us.

We started with the role she was doing at the moment . . . . .

We started with the role she was doing at the moment . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Do you enjoy singing Brangäne?

Nadine Denize: Yes! This is a very important event in my career because I sing all the other Wagner mezzo roles

— Kundry, Waltraute, Fricka, Venus. Brangäne is a very important role, and it is the last one for me to get involved in. I find it a very interesting part, a little more difficult than some of the other roles because is it not a leading character. She is, in a sense, a kind of mirror, and it is through Brangäne that we understand what is going on in Isolde. I am there to bring out these things. But I love to sing Brangäne because it lies so well in my voice. The Warning is one of the most beautiful things that Wagner ever wrote. Tristan is the most beautiful opera that has ever been written in the world, and I am delighted to participate in it. I don’t have much to do in Act III, but while that is being played, I stand in the wings to hear the music again. It sort of closes the circle, closes the book. What was in the head and mind of Wagner is completed in the third act.

BD: So Tristan is a ring, just like the Ring is the ring?

ND: Yes.

BD: Does Brangäne know beforehand the results of giving the love potion instead of the death potion?

ND: In this production of the opera, Brangäne is really confused. She makes a mistake because she is shaken up. Isolde asks for the death potion, and Brangäne is so confused and frightened that she just takes the first one which comes to hand, which happens to be the love potion.

BD: Does the audience observe this happenstance?

ND: Yes. In this production, there are several bottles from which to choose. In the story itself, she is not certain. In other productions, it might be a more conscious act on the part of Brangäne.

BD: If a producer insisted that you be evil, like Klingsor, and consciously disrupt Isolde’s life, how would you react?

ND: Well, as I said before, Brangäne represents the subconscious of Isolde, and if you think of her that way, you know that Isolde has been in love since before the opera started. So when she says,

“Give me the death potion,” her subconscious is really saying, “Give me the love potion.” So it would be very difficult to make Brangäne be anything else but the instrument of the subconscious.

BD: Tell me about the role of Kundry.

ND: It’s an extraordinary role, but very difficult vocally. The first act is for a contralto, and the second is for a lyric soprano.

BD: How do you feel about the third act with its complete lack of vocal line for you?

ND: There are only two words for me to sing, but the music is magnificent.

BD: How hard can Kundry fight Klingsor?

ND: It is a fight, but she is a prisoner. Klingsor sees that his empire is about to crumble, therefore he sends Kundry to prevent that from happening by enticing Parsifal.

BD: How much happier is she when she is not under Klingsor’s spell?

ND: There are the two aspects of the personality in the first two acts. The third act is really a re-birth. The cry is like a child issuing forth from the womb. In the first act she rushes to bring the little vile of balsam to Amfortas, and in the second act she is the siren, the temptress.

BD: Is there any connection between the love duets of Kundry and Parsifal, and Isolde and Tristan?

BD: Is there any connection between the love duets of Kundry and Parsifal, and Isolde and Tristan?

ND: No, absolutely no connection. Wagner missed his mother, and it’s amazing how the heroes in the operas are without a mother. The mother of Parsifal is dead, and Kundry uses the reference to her to be with him. She says that she knew his mother very well. There is the temptation of maternal love, perhaps even more than sexual love.BD: Do you enjoy the role of Venus?

ND: In Tannhäuser, there are two versions of the opera. The first version is much more ‘soprano-ized’, whereas the second version, done for Paris, was written later when Wagner was thinking of Parsifal. The role of Venus shorter, but has more of these other aspects to it.

BD: Do the French people like Wagner?

ND: Very much. There is a circle of fans of Wagner, but we don’t have many productions of Wagner because few French conductors do it. It is always an event when a new production is mounted of any opera, but when it’s a Wagner opera, it’s a very special event. The last time I saw Tristan in Paris was fifteen or twenty years ago with Birgit Nilsson. Anyway, there are very few singers who can approach these roles.

BD: Would you sing any of the Wagner roles in French?

ND: No, absolutely not! I would rather stay at home than sing Wagner in translation. The libretto is so very special, and Wagner thought of the word and the music at the same time. It is untranslatable. It is a kind of German that is much different from other German. It’s ‘High German’, but the words have a kind of meaning in Wagner’s vocabulary which renders them untranslatable.

BD: Do you try to go to Wagner operas even when you’re not singing in them?

ND: Whenever I’m singing some place, especially in Germany, I take advantage of it to go to performances that are accessible to me. As part of my job, it’s important to do that, to see how the different conductors approach the works.

BD: So it’s more study than relaxation?

ND: Yes. I can’t relax when I listen to music. The music of Wagner is like a drug. Right now, I am getting myself better under control, but it wasn’t very long ago that whenever I listened to Wagner I had definite symptoms

— feverishness, nervousness, agitation — a physical reaction.I thank God that I’ve been given a voice that can sing the Wagner repertoire because it’s marvelous and I enjoy doing it.

BD: Do you find your voice goes up or down through the years?

ND: Down. I’m now a dramatic mezzo-soprano. Brangäne is the same tessitura as Isolde. There is no high C, but the roles lie in the same part of the voice.

BD: Would you ever sing Isolde?

ND: No, never. I do sing the Liebestod in concert, and also the Wesendonck Lieder.

BD: In the alto arrangement?

ND: No, no. I know there is another arrangement for lower voice, but I sing it as originally written.

BD: Let me ask about one last role

— Fricka.

ND: Fricka is also one of these mirror-like characters, and in the confrontation scene with Wotan, she really is a reflection of the will of Wotan. She is telling Wotan one of the things he should be considering, something that Wotan already knew in the first place. So what she is doing is showing one aspect of what to do with the situation.

BD: Later on, though, Brünnhilde sways that she is Wotan’s will. Is he schizophrenic?

ND: Perhaps. I don’t like Wotan much. It is a difficult role that is often poorly realized by the people who approach it.

BD: Is Fricka happy with Wotan?

ND: No, not at all.

BD: Then why do they stay together?

ND: There are all kinds of things to hold her there earlier on. In Rheingold, there is the prospect of the gold, there is Valhalla under construction, there are all of these things which will be enough to hold her. She is the goddess who is in charge of conjugal rights, and it is her duty to maintain these rights. In the second opera, Die Walküre, she is stunned by the way things are going.

BD: In her heart, would she rather leave Wotan?

ND: In the Bayreuth production of Chéreau, this scene is presented as a domestic squabble, a household fight of a married couple.

BD: Let’s talk a bit about Massenet and about Carmen. Tell me about Carmen [_shown in photo below_].

ND: Carmen was the first role that I studied in 1965. I didn’t dare to sing it immediately because it’s a very difficult role.

BD: What makes it difficult?

ND: It was a question not so much of the difficulty of the role, but of her own personality; to be this extroverted kind of a lady who’s left her family, and she’s a free woman on her own. That was rather alien from me.

ND: It was a question not so much of the difficulty of the role, but of her own personality; to be this extroverted kind of a lady who’s left her family, and she’s a free woman on her own. That was rather alien from me.

BD: Do we look at Carmen differently now because of the malaise of today’s society?

ND: At the time it was first written, this kind of a woman was so extroverted that she ran things. She was the boss. She made all the decisions for the smugglers, and this kind of a role for woman was looked upon as scandalous at the time of the premiere, whereas nowadays it’s very readily accepted. People are recognizing in Carmen many of the traits of the contemporary woman.

BD: So, does this influence the way you bring her to the stage?

ND: Carmen’s a free woman, like a wild plant that grows without restraints. When the opera was first premiered, they thought that she was a whore, whereas we don’t look at her that way now at all. She is not as a whore, but rather a free woman who chooses her lovers as she pleases, and lives like that wild plant without restraint.

BD: Do you enjoy playing that role?

ND: Yes! [Laugh] Oh, it’s a lovely one.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] Do you ever wish you could live the life of Carmen?

ND: I’m not interested in smuggling! [Laughter all around]

BD: But you could run your own opera company that way with an iron fist!

ND: Why not?

BD: Do you have any interest in getting into the managerial side of opera?

ND: It would not be in an administrative capacity, but in an artistic one. I am also interested in teaching singing.

BD: How do you decide if a young singer is going to make the big career or not?

ND: First of all, nowadays there are a lot of singers, but a generation or so ago there weren’t very many. Part of the reason why there weren’t was that the whole career in the theater was looked upon as vaguely doubtful, or suspicious, or suspect. Even my parents were really upset when I declared that I wanted to become a singer, because I’m the only child, and they had other plans for me.

BD: What did they want you to do?

ND: My parents were very worried about my future, and they were afraid that with the singing profession, to be an opera singer, there’s such an element of the cast of the dice

— luck. My parents were very, very worried because many, many people start out to become singers, and only a very few actually become singers. So, they insisted on my having a complete musical education, and I have a degree. I could be a teacher of music. I had to study piano, and singing, and music history, and harmony, and all of the things that go to be a professor of music. Then, if anything ever happened to my voice, I would be prepared. I could teach at some university or other. That was my preparation, but after I graduated from the conservatory, and I won the first prize in singing, I was immediately admitted into the opera. My parents were delighted that I had made the grade, that I was launched on the career. They saw that opera is not such a bad place! BD: Would you encourage your children to do the same kind of thing?

BD: Would you encourage your children to do the same kind of thing?

ND: I would hesitate to give that advice

— as I would to any young student of singing —because, first of all, nowadays in order to have a career, you have to have an exceptional instrument. But even if you have this exceptional instrument, there are other things that you have to have. You have to have the will to become an opera singer. You have to have the desire, the application, the ability to make sacrifices, to accept a life of great deal of solitude, of being always on the road and traveling. It’s a different kind of life, and you have to want a stage career very much in order to make that kind of sacrifice to your comforts.

BD: So, you have to put up with the bad times in order to get the good times?

ND: Yes, and there are other problems that a singer can have. For example, I know many singers in the chorus who have exceptional voices. They are wonderful singers, but they really stay in the chorus and don’t even try for a soloist’s career because once they’re out on the stage all by themselves, they are so afflicted with stage fright that they’re paralyzed, and they cannot sing. You’ve got to have this ability to be able to do this opera in front of the audience. And you’ve got to be able to recognize it, and to grab it when it passes the first time.

BD: You don’t get a second chance?

ND: Apart from the element of luck, you must always be directing your career, focusing it. For example, I entered the Opera de Paris when I was twenty, and they wanted me to do roles like Amneris, and other leading mezzo roles which are very heavy, which I felt I was not ready for. You have to be able to have the wisdom to realize that if you attempt these roles at that age, that you can fail, and you can damage your instrument. You can do other things first.

BD: How difficult is it to say no?

ND: Sometimes it is difficult. At the time I entered the Opéra de Paris, the theater was functioning very poorly. There was a very reduced repertory

— about five or six operas — and the only opera which had a mezzo soprano as a leading lady was Carmen, and I wasn’t ready for that yet. I wanted to choose my roles carefully, whereas the Opéra Comique was functioning very well, and they a big repertoire with lots of things that I would like to sing eventually — like_Werther_, Don Quichotte...

BD: Mignon?

ND: Mignon, yes. So I was able to the choose the roles I wanted to do. I was a member of the Opéra, and I would also sing with the Opéra Comique because there was many of the same personnel for both theaters. One real stroke of luck gave my career a push. While I was there, Rolf Liebermann came to the Paris Opéra. He started reviving things and changing things. He was producing Parsifal, and the Kundry got sick. So he asked me if I would like to sing Kundry. I had been studying_Parsifal_ for my own pleasure. I never thought of doing the role, and I was given this opportunity. It was like a hand of poker because I felt I had very little to lose and very much to gain. So, I sang it, and it was successful, and it really launched my career. Now I travel all over, doing this kind of repertoire.

BD: Let me ask about Charlotte. Do you like the part? [Shown in photo at right, which is for sale from a commercial dealer, hence the watermark.]

BD: Let me ask about Charlotte. Do you like the part? [Shown in photo at right, which is for sale from a commercial dealer, hence the watermark.]

ND: I love the role, but it is a more difficult role than Carmen. The character of Charlotte is really kind of cut out, and she has nothing to do because she is more of a middle-class woman, a woman who is dictated to, who has many, many principals that she feels are really important, and necessary to follow. Then she comes into to all these internal struggles, whereas Carmen doesn’t struggle. Carmen knows what she wants to do and she does it, whereas Charlotte does not know there are any options. She knows what she ought to do, and she was the prisoner of her parents. Her dying mother forced her into this marriage when she still had a chance to get out of it. Her principals pushed her into the marriage. Even though she met Werther, who’s very romantic and very different, it is this blossoming of the woman that you have to show with Charlotte. This is a woman who had been guided with her blinders on, and who feels she has a definite destiny.

BD: She can’t stray from this one plan?

ND: No. All of a sudden she’s presented with this, and she realizes who she is in her struggle. Not so much that her hands are free to do what she wants to do, but she finds that she is not really the daughter of these two people. Charlotte is very middle-class. All of the middle-class ideals and virtues and requirements are very important to her.

BD: Could Charlotte and Werther have been happy?

ND: The real problem is with Werther, not with Charlotte. Werther creates his own destiny. It’s Werther that decides he wants to kill himself. It’s Werther that does all these things. Charlotte couldn’t just say,

“I’m packing my suitcases, and good-bye,” because she has this situation which Werther also respects. There is also the conflict in Werther. He does not want take this woman and turn her into a fallen woman. That’s not what Werther wants at all. He’s very romantic, and would have a cry about it rather than do something about it.

BD: Would it have destroyed Werther then if she had come with him rather than go with Albert?

ND: The whole character of Werther is so tormented. He requires this kind of a situation in order to feed his personality, to develop it with these conflicts. He needs those in order to live.

BD: So he couldn’t have fallen in love then with a woman who could have married him?

ND: No. He’s like Hoffmann! [Both laugh] He wants something far removed from the common place, someone extraordinary.

BD: Is Albert at all happy with his lot?

ND: He’s neither happy or unhappy. He’s tranquil, middle-class, content.

BD: Do you do any other Massenet besides Werther?

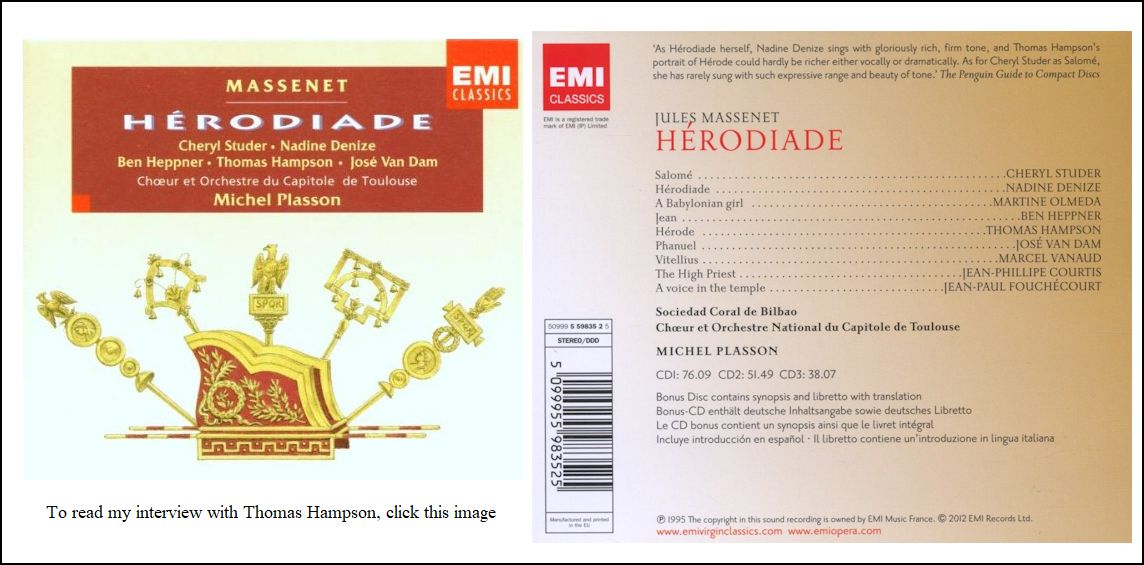

ND: I sing Hériodiade in Hériodiade

[_which she later recorded, as seen in the CD notes below_].

BD: Is that a good opera?

ND: There are beautiful pieces of music, it is true but the text itself is rather old-fashioned, out of date. Compared to Strauss it’s a rather negligible work.

BD: Have you done the Strauss?

ND: I might sing Heriodias, but never Salome. [Laughs]

BD: Tell me a bit about Berlioz.

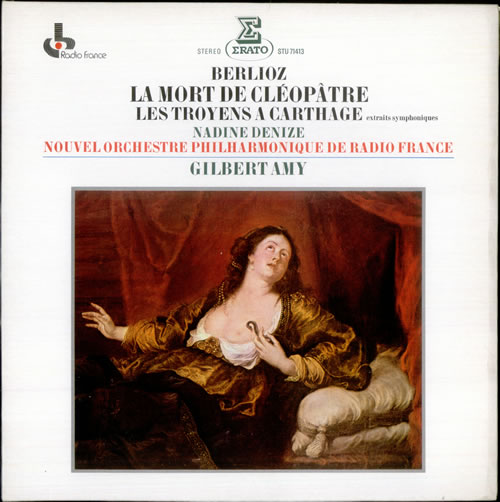

ND: I like him above all because of the originality of his music. I sang Cassandre at Ravinia, and for this period I am very enamored of the Cantata called The Death of Cleopatra. It is very interesting. It’s a cantata that lasts about half an hour, but it really is a mini-opera, a sort of monologue for Cleopatra who is preparing to kill herself. The vocal line and the harmony that he uses show an ability to seek out an unusual orchestral timbre in the way he writes this work. He turns it into something extraordinary

— above all, for that period when it was written. It was a student work that he wrote to win the Prix de Rome, a scholarship to study. He submitted it for the Prix de Rome competition, and it was rejected because the jury was horrified by what he was doing. It was much too original for these fine gentlemen of the institute.

The Prix de Rome, or Grand Prix de Rome, was a French scholarship for arts students, initially for painters and sculptors, that was established in 1663 during the reign of Louis XIV of France. Winners were awarded a bursary that allowed them to stay in Rome for three to five years at the expense of the state. The prize was extended to architecture in 1720, music in 1803, and engraving in 1804. The prestigious award was abolished in 1968 by André Malraux, the Minister of Culture.

The Prix de Rome, or Grand Prix de Rome, was a French scholarship for arts students, initially for painters and sculptors, that was established in 1663 during the reign of Louis XIV of France. Winners were awarded a bursary that allowed them to stay in Rome for three to five years at the expense of the state. The prize was extended to architecture in 1720, music in 1803, and engraving in 1804. The prestigious award was abolished in 1968 by André Malraux, the Minister of Culture.

The music prize was an award for composers allowing the winner to spend a year studying at the Villa Medici in Rome. It also entitled him to a five-year pension. The prize was adjudicated by the Paris Conservatoire. Entrants had to submit a fugue as proof of their compositional skills and the four successful candidates were then required to write a dramatic cantata to a text chosen by the judges.

Berlioz's efforts to win the prize are described at length in his Memoirs. He regarded it as the first stage in his struggle against the musical conservatism represented by the judges, who included established composers such as Luigi Cherubini, François-Adrien Boieldieu and Henri Montan Berton. Berlioz's stay in Italy as a result of winning the prize also had a great influence on later works such as Benvenuto Cellini and Harold en Italie. The composer subsequently destroyed the scores of two cantatas (Orphée and Sardanapale) almost completely, and reused music from all four of them in later works. There was a revival of interest in the cantatas in the late 20th century, particularly La mort de Cléopâtre, which has become a favourite showcase for the soprano and mezzo-soprano voice.

La Mort de Cléopâtre (The Death of Cleopatra) was Berlioz's third attempt to win the Prix de Rome from the Academie des Beaux-Arts. His first attempt in 1827 was La Mort d'Orphée, which failed to place. His second attempt in 1828 was Herminie, which took second place. Berlioz called La Mort de Cléopâtre "a lyric scene" for soprano and orchestra, setting a text by P.A. Vieillard. The vocal writing is extremely dramatic, but it ignores distinctions between recitative and aria, which infuriated the jury. The orchestral writing is lush and full, with extraordinary harmonies that likewise alienated the jury. La Mort de Cléopâtre was judged such a failure in the eyes of the Academie that it gave no first place prize that year. The following year, Berlioz won the Prix de Rome with his conservative La Mort de Sardanapale, but, having already composed his wildly experimental Symphonie fantastique, he found that he no longer cared all that much about the Academie.

BD: Does The Damnation of Faust work as an opera on stage?

BD: Does The Damnation of Faust work as an opera on stage?

ND: It works very well. I’m going to sing it very shortly in Marseille after I leave here. This will be the first opera that I’ve ever done with the staging of Maurice Béjart. It’s a wonderful piece of music, and it works very well on the stage.

BD: Do you prefer to do it on stage, or in a concert?

ND: Even with an opera like Wagner, the music itself is so rich that you don’t really need a stage production. But if you’ve got one, why not?

BD: Let me ask about The Trojans. Have you done both roles in the same evening, or just Cassandre?

ND: In 1984 [_two years after this interview took place_] for the first time I will sing both of them on the same night.

BD: Is that too much?

ND: It’s very difficult because it calls for a lot of nervous energy. The roles are very contrary and require a lot of stamina, a lot of nervous energy in order to pull them off. Cassandra is a hysterical woman, and then the role of Didon is very long. It is going to be very interesting when I do it. The technical difficulty is the difference in the roles, because Cassandre calls for a rather classical declamation style. She sings almost always alone, and it requires one kind of vocal production in singing, whereas the role of Didon is mostly in conjunction with duets and trios. In some of the numbers, what you need is not this grand romantic declamation instrument, but rather something like a chamber instrument to work with the different ensemble pieces. The role places different demands on the voice.

BD: Is there enough time at the intermission to change gears?

ND: Yes, there is half an hour. I don’t know yet how it will work physically, but mentally yes. An intermission can be sufficient to change gears and do the other role. Technically, whether that is going to come off remains to be seen.

BD: I hope it goes well. Have you sung Béatrice?

ND: Béatrice et Bénédict? It’s a real masterpiece. The whole situation is comic and it’s all kinds of fun, but on the other hand, the character of Béatrice is proud and sort of wild. She’s got many quite serious qualities which are then emerging mainly into the story.

Béatrice et Bénédict is like Carmen — it has two versions. One of them is where everything is sung, and there’s a recitative in between musical numbers. There’s also another version which has spoken dialogue between the two.

BD: Which do you prefer?

ND: I prefer the spoken dialogue version.

BD: What about in Carmen?

ND: I have never done it with spoken dialogue. They don’t do that version so much in France. The speaking voice destroys the atmosphere. The recitatives that were done by Ernest Guiraud are very well done, and they’re very effective. They connect the musical numbers very well, and I like that. The placement of the voice for speaking passages and sung passages is not always the same, which can create problems. And the French like Carmen with the sung recitatives because it works so well. It’s a dramatic piece. It’s dissipated by the spoken word. The very fact that there is spoken dialogue in Béatrice et Bénédict adds to the fun because it’s a comic situation, whereas in Carmen, which is a dramatic one which terminates in death, the spoken dialogue destroys that somberness of tone, the dramatic effect of the rest of the piece.

ND: I have never done it with spoken dialogue. They don’t do that version so much in France. The speaking voice destroys the atmosphere. The recitatives that were done by Ernest Guiraud are very well done, and they’re very effective. They connect the musical numbers very well, and I like that. The placement of the voice for speaking passages and sung passages is not always the same, which can create problems. And the French like Carmen with the sung recitatives because it works so well. It’s a dramatic piece. It’s dissipated by the spoken word. The very fact that there is spoken dialogue in Béatrice et Bénédict adds to the fun because it’s a comic situation, whereas in Carmen, which is a dramatic one which terminates in death, the spoken dialogue destroys that somberness of tone, the dramatic effect of the rest of the piece.

BD: Let me ask you about your Italian roles.

ND: I

’ve sung Princess Eboli in Don Carlos [_shown in photo at right_], and the Duchess, Federica, in Luisa Miller.

BD: How conniving is Eboli? [The translator rendered the word as

‘wicked’.]

ND: Eboli was a mistress who is a very rich woman, and very powerful in the court of Spain. She falls into line with these other great ladies of the period who are mistresses to kings. As an intriguer or a conniver, I’d say very much so, and this is very obvious because when she sees what she has done to the queen, and she repents very sincerely. That is the essence of the aria O don fatale.

BD: Does she love Philip?

ND: There’s nothing in the text that indicates she’s still in love with him. I’ve read an Austrian writer who claims that Eboli was never a mistress of Philip. There are things in the text that are never explained, such as if Eboli put the picture into the jewel box when she lifts the jewel box and takes it to the king. She takes the place of Elisabeth in the garden because she’s in love with Don Carlos. She confesses all of her sins in the garden.

BD: Have you done this work in French?

ND: No, never. Like most French singers, I don’t like to sing in French because French is not a vocal language. It’s wonderful for the richness of vocabulary and subtleties of expression, but vocally it works against the vocal production, whereas in the operas of Verdi, the language itself helps the vocal production. French is a flat language because it does not have stressed syllables. Unlike Italian, where there are stressed and unstressed syllables, French just kind of irons everything out.

BD: Because Verdi wrote the opera in French, this is my own little hobby horse to get Don Carlos back into the original French. It

’s the same with The Sicilian Vespers, but there’s no part for you. Have you done Azucena?

ND: No. It’s a little bit contralto for me. I prefer the roles that have a little more in the upper register.

BD: It is apparent that you enjoy singing!

ND: For sure! If I didn’t sing I’d be dead!

BD: I hope you continue to sing for a long time. Thank you very much for spending this time with me today.

ND: Thank you.

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded over two sessions, October 6 & 13, 1982. The first part (about Wagner) was transcribed and published in Wagner News in October of 1985. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1993 and 1998. This transcription was completed in 2018, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to Alfred Glasser, Director of Education at Lyric Opera of Chicago, for providing the translation during the interview. My thanks also go to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit hiswebsite for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.