Genome sequence of the cultivated cotton Gossypium arboreum (original) (raw)

Main

The genus Gossypium includes 46 diploid (2_n_ = 2x = 26) and 5 well-established and 1 purported tetraploid (2_n_ = 4x = 52) species1,2. It has been proposed that all diploid cotton species may have evolved from a common ancestor that subsequently diversified to produce eight groups, including groups A–G and K3. Allopolyploid cotton may have appeared in the last 1–2 million years through hybridization and subsequent polyploidization events between the A- and D-subgenome progenitors. All tetraploid cotton species came from interspecific hybridization between the A-genome species G. arboreum (A2) and the D-genome species G. raimondii (D5)3. The A-genome species are cultivated, whereas the D-genome species do not produce spinnable fiber. Although G. arboreum (A2) and G. raimondii (D5) are the putative donor species for the A and D chromosome groups, respectively, tetraploid cotton species differ greatly with respect to plant morphology as well as economic characteristics, including fiber production, oil content and disease resistance. Furthermore, G. arboreum (1,746 Mb/1C) has a genome size that is almost twice that of G. raimondii (885 Mb/1C)4.

In the current study, assisted by a high-resolution genetic map, we anchored and oriented 90.4% of the G. arboreum assembled scaffolds on 13 pseudochromosomes. This assembly was compared with that of G. raimondii to understand possible paths for genome evolution and species divergence. A highly homozygous single-seed descendant, derived from 18 successive generations of self-fertilization, of the cultivated diploid cotton Shixiya1 (SXY1) was used for DNA sequencing. Assembly of the G. arboreum genome and comparative studies with the genome of G. raimondii5,6 may provide new insights into the process of divergence among polyploid species7,8,9. We believe that the G. arboreum genome offers a diploid reference for the analysis of cotton agronomic traits, such as fiber quality10,11,12,13 and disease resistance14,15.

Results

Genome sequencing and assembly

We sequenced and assembled the G. arboreum genome using the whole-genome shotgun approach. In brief, a total of 371.5 Gb of raw paired-end Illumina reads was generated by sequencing genome shotgun libraries with different fragment lengths that ranged from 180 bp to 40 kb (Supplementary Table 1). After filtering out low-quality reads, 193.6 Gb of high-quality sequence was obtained and used for the de novo assembly process (Supplementary Table 2). We next used 33,454 BAC end sequences (16,727 pairs; approximately 1-fold physical coverage) to improve the assembly. Over 90% of our BAC clones contained inserts of ≥50,000 bp in length (Supplementary Fig. 1). In-depth analysis showed that all scaffolds were supported by multiple (>80) paired-end linkages (Supplementary Fig. 2). The number of scaffolds decreased in libraries with increasing insert size (>2,000 bp). Using _K_-mer distribution analysis, the genome size was estimated to be 1,724 Mb (Supplementary Fig. 3), which is consistent with a previous report4.

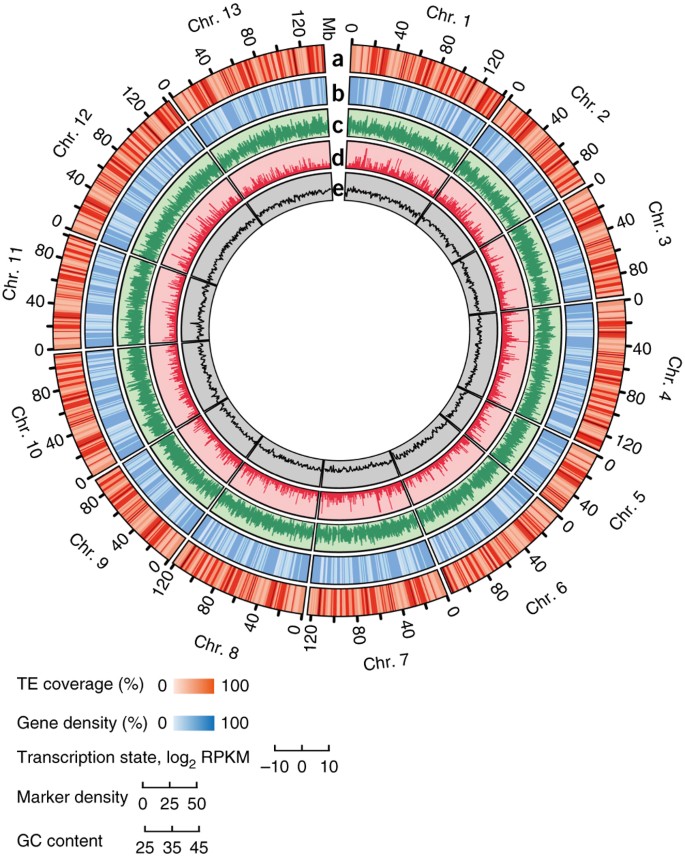

Our final assembly, performed with SOAPdenovo16,17, showed that the G. arboreum genome is 1,694 Mb in total length (Table 1). Ninety percent of the assembly fell into 2,724 superscaffolds that were >148 kb in length, with the largest scaffold being 5.9 Mb. N50 (the size above which 50% of the total length of the sequence assembly can be found) for the contigs and scaffolds was 72 kb and 666 kb, respectively. Data quality was assessed by comparison with Sanger sequencing–derived G. arboreum sequences and by mapping available ESTs to the assembly. Nineteen of the twenty completely sequenced G. arboreum BAC clones available from GenBank were recovered in our assembly, with >98% sequence identity (Supplementary Table 3). Of the 55,894 Sanger sequencing–derived G. arboreum ESTs (>200 bp in length) available from NCBI, 96.37% were detected in our assembly (Supplementary Table 4). Using a restriction site–associated DNA (RAD) linkage map that we constructed during the current study based on 24,569 codominant SNP markers, 1,532 Mb or 90.4% of the assembled genome was anchored and oriented on 13 pseudochromosomes (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 5), which contained 97.1% of the predicted gene models. Collinear relationships existed between the SNP markers and most of the assembled G. arboreum pseudochromosomes, which indicates that our assembly is of high quality (Supplementary Fig. 5). Collinearity was also observed between our G. arboreum assembly and the tetraploid genetic map reported previously18 (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 6). The GC content of the G. arboreum genome was comparable to those for the genomes of G. raimondii5, Theobroma cacao19 and Arabidopsis thaliana (Fig. 1e).

Table 1 Global statistics of G. arboreum genome assembly and annotation

Figure 1: Characterization of the G. arboreum cotton genome.

(a) Percent coverage of TEs in non-overlapping windows (window size = 500 kb). Outer tick marks show the calculated lengths of 13 G. arboreum pseudochromosomes. (b) Gene density estimated on the basis of the number of genes in non-overlapping 500-kb windows. (c) Transcription state. The transcript level for each gene was estimated by averaging values of reads per kilobase of mapped cDNA per million reads (RPKM) from different tissues in non-overlapping 500-kb windows. (d) Marker density represented by the number of SNPs in non-overlapping 500-kb windows. (e) GC content estimated on the basis of the percentage of G+C nucleotides in 500-kb non-overlapping windows.

Genome annotation

We performed genome annotation by combining results obtained from ab initio prediction, homology search and transcriptome alignment. As much as 68.5% of the G. arboreum genome was composed of various types of repeat sequences (Fig. 1a, Table 1 and Supplementary Table 7). We believe that this genome has the greatest amount of repeat-containing sequences among sequenced eudicots19,20,21,22,23,24. Long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons accounted for 95.12% of all repeat sequences. In comparison with the G. raimondii genome5, the G. arboreum genome had noticeable proliferation of Gorge elements, whereas LTR Copia elements tended to accumulate in the G. raimondii genome (Supplementary Table 8), as has been suggested previously25. LTR retrotransposons in G. arboreum appeared to have inserted randomly along each chromosome (Fig. 1a), in a pattern substantially different from the ones observed for their insertion sites in soybean and potato, in which LTRs are clustered near the centromere and are found less frequently near telomeres20,21.

A total of 41,330 protein-coding genes were identified in the G. arboreum genome, with an average transcript size of 2,533 bp (as determined by GLEAN) and a mean of 4.6 exons per gene (Fig. 1b, Table 1 and Supplementary Table 9). The genome encoded 431 microRNAs (miRNAs), 10,464 rRNAs, 2,289 tRNAs and 7,619 small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) (Table 1). Among the annotated genes, 85.64% encoded proteins that showed homology to proteins in the TrEMBL database, and 68.71% were identified in InterPro (Supplementary Table 10). Over 96% of predicted coding sequences were supported by transcriptome sequencing data (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 9), which indicated high accuracy of G. arboreum gene predictions from the genome sequence. Orthologous clustering of the G. arboreum proteome with 3 closely related plant genomes identified 11,699 gene families in common, with 739 gene families that were present specifically in G. arboreum (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Genome evolution

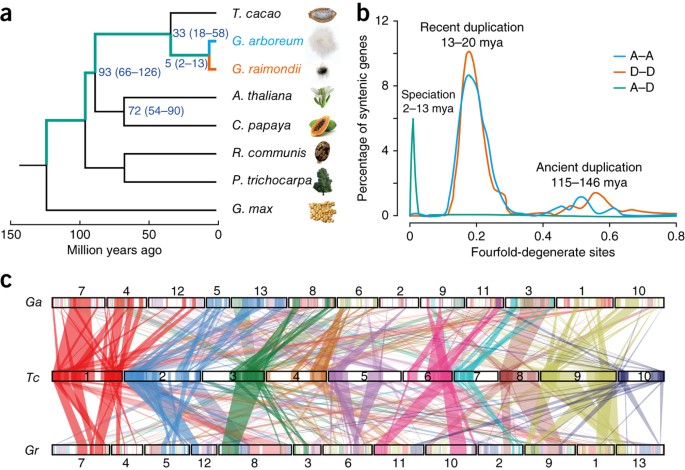

The current descendants of the two diploid cotton species that hybridized to create all cultivated allopolyploid cotton species, G. arboreum (A2) and G. raimondii (D5), exhibit a twofold difference in genome size4,26. Molecular phylogenetic analyses27 suggested a divergence time for G. arboreum and G. raimondii of 2–13 million years ago, with their common ancestor having diverged from T. cacao 18–58 million years ago (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2: Phylogenetic and evolutionary analysis of the Gossypium genomes.

(a) Phylogenetic analysis indicated that G. arboreum and G. raimondii separated ∼5 million years ago (mya). (b) Fourfold-degenerate analyses suggested that the Gossypium genomes might have undergone two WGD events and one speciation event. (c) Large numbers of syntenic blocks were found when comparing either the G. raimondii (Gr) or G. arboreum (Ga) genome with the genome of T. cacao (Tc). Numbered rectangles represent the chromosomes.

We scanned the G. arboreum genome for syntenic gene blocks identified on the basis of protein-coding sequence similarity. An age distribution was calculated for all duplicate gene pairs on the basis of the number of transversions at fourfold-degenerate sites. Using 1,917 paralogous gene pairs of similar age and excluding tandem or local duplications, a large peak centered around 0.17 synonymous transversions per site and a second peak at about 0.54 synonymous transversions per site were observed in both the G. arboreum and G. raimondii genomes, indicating that a recent and an ancient whole-genome duplication (WGD) event occurred in cotton (Fig. 2b). Both of these WGD events in G. arboreum coincided with those in G. raimondii, which were estimated to have occurred at 13–20 and 115–146 million years ago5,28. The ancient duplication event corresponds to the ancient hexaploidization event that is shared among the eudicots29,30. Using a whole-genome alignment approach, we found that both the G. raimondii and G. arboreum genomes showed close collinear relationships with the genome of T. cacao. There were 209 and 295 collinear blocks covering 82% and 66% of the G. raimondii and G. arboreum genomes, respectively (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 11). When the G. raimondii assembly reported by Paterson et al.6 was used for the analysis, a slightly lower number of collinear blocks with higher genome coverage were identified (Supplementary Table 11). Approximately 50% of the T. cacao genome was aligned with two segments in each of the cotton genomes (Fig. 2c), undoubtedly suggesting the existence of a _Gossypium_-specific WGD event after speciation from the T. cacao lineage.

Orthology maps and retrotransposition analysis

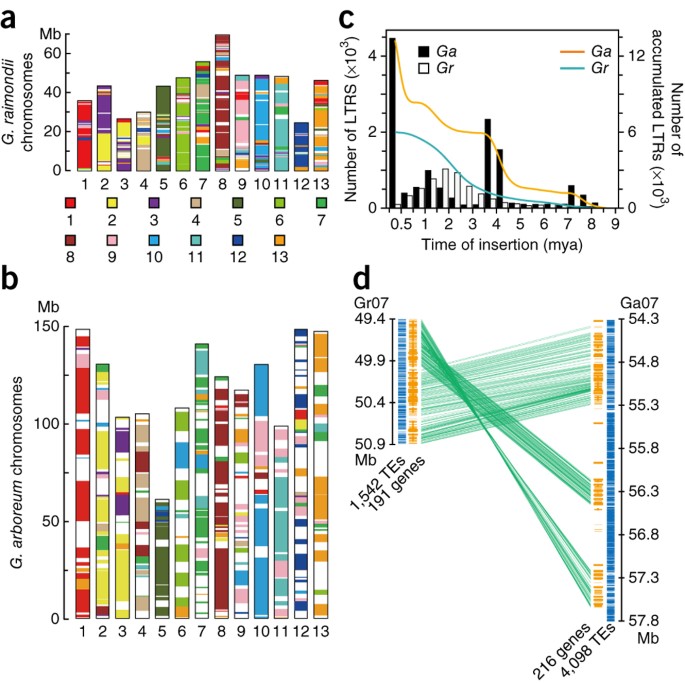

Whole-genome alignment also identified 68,863 orthologous hits (anchors) on the 2 cotton genomes, including 33,229 genes for G. arboreum and 34,204 genes for G. raimondii. These anchors spanned 17.1% of the A genome and 35.0% of the D genome (Supplementary Table 12). When the G. raimondii assembly by Paterson et al.6 was used for the analysis, we observed a total of 63,810 anchors that spanned 23% of the A genome and 48% of the D genome, indicating an improvement in data quality for the later assembly in this respect (Supplementary Table 12). Using these anchors, we found that the 2 cotton genomes shared 780 syntenic blocks that covered 73% and 88% of the assembled chromosomes in G. arboreum and G. raimondii, respectively (Supplementary Table 13). Chromosomes 1, 4–6 and 9–13 were highly collinear in the two cotton species, whereas large-scale rearrangements were observed on chromosomes 2 and 3 of G. raimondii and deletions and insertions were observed on chromosomes 7 and 8 of G. arboreum (Fig. 3a,b).

Figure 3: Whole-genome alignment and expansion of the G. arboreum genome.

(a,b) Whole-genome alignments of G. arboreum on G. raimondii (a) and of G. raimondii on G. arboreum (b). Chromosomes from both genomes were plotted according to their assembled lengths. Each of the 13 chromosomes in a and b is designated by color; white blocks represent regions that could not be aligned. Only syntenic blocks of ≥2 Mb in length are shown. (c) Analysis of LTR number and insertion time in G. arboreum (Ga) and G. raimondii (Gr). Bars (left y axis) indicate the number of LTRs inserted at any specific time point, whereas curves (right y axis) represent the accumulated total number of LTRs throughout evolution. (d) In-depth study of a microsyntenic block on chromosomes 7 of G. arboreum (Ga07) and G. raimondii5 (Gr07). Yellow bars, gene models; green lines, syntenic gene pairs; blue bars, TEs present at the corresponding chromosomal locations in each genome. The total number of genes and TEs found in each region is shown beneath each schematic.

Expansions of transposable element (TE) families have been reported in the genome of G. raimondii5. In G. arboreum, two major clusters of retrotransposition activity were found at 0–0.5 and 3.5–4.5 million years ago, with two additional minor sets of retrotransposition activity present around 1.0 and 7.0–8.0 million years ago (Fig. 3c). As a result, the difference in LTR numbers between these two cotton species showed two separate peaks at ∼0–0.5 and ∼3.5 million years ago (Fig. 3c). Data analysis indicated that the G. arboreum genome tended to harbor more LTRs inserted during the last 0.5 million years, whereas extremely low LTR activity was observed in the G. raimondii genome over the same period of time. Thus, LTR activities substantially contributed to the twofold increase in the size of the G. arboreum genome, as previously suggested31. We confirmed our assertion by analyzing microsyntenic blocks on chromosome 7 of both G. arboreum and G. raimondii that were 3.5 and 1.5 Mb in length, respectively (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 8). The gene loci in these syntenic blocks were highly collinear, with 191 loci in G. raimondii and 216 loci in G. arboreum. However, 4,098 TEs were identified in G. arboreum, whereas only 1,542 TEs were found in G. raimondii (Fig. 3d). Close to 58% of the TEs reported in Figure 3d were Gorge elements in G. arboreum, whereas these elements represented only ∼21% of TEs in G. raimondii (Supplementary Table 14).

Analysis of potential Verticillium wilt resistance genes

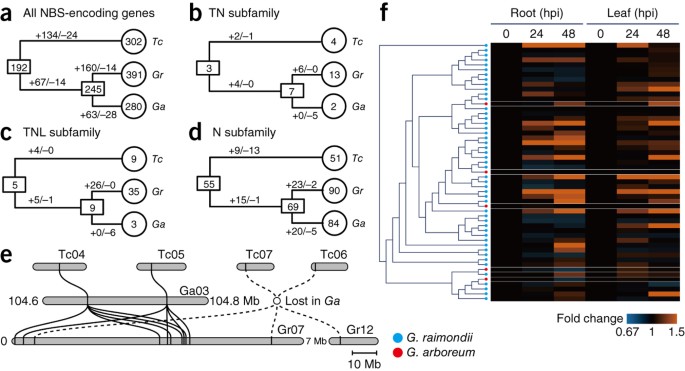

Verticillium wilt is a widespread and destructive cotton disease caused by the soil-borne fungus pathogen V. dahliae. G. raimondii is nearly immune to the pathogen, whereas G. arboreum is easily susceptible14,15. Genes related to disease resistance (R genes) have critical roles during various stages of disease development in plants. Thus far, most of the cloned R genes encode NBS domains21,32. We compared the G. arboreum genome to the G. raimondii5 and T. cacao19 genome sequences to identify differences in the expression patterns of NBS domain–encoding genes. We identified 391, 280 and 302 such genes in the genomes of G. raimondii, G. arboreum and T. cacao, respectively (Fig. 4a). T. cacao is also susceptible to Verticillium wilt. Phylogenetic analysis predicted that there were 192 ancestral NBS-encoding genes in the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of cotton and cocoa (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 9). The greatest differences in the numbers of NBS-encoding gene family members in these two cotton species existed in the TN and TNL subfamilies (Fig. 4b,c), whereas the number of genes in the N subfamily remained relatively unchanged (Fig. 4d). Tandem duplications seemed to have a significant role in the expansion of the NBS-encoding gene family in G. raimondii after its divergence from G. arboreum ∼5 million years ago, and segmental loss contributed to its contraction in G. arboreum (Fig. 4e). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of members of the TNL and TN subfamilies showed substantial gene expansion in the G. raimondii genome and indicated that many orthologs that were not present in G. arboreum responded to the pathogen soon after infection. All early pathogen-responsive genes came from the G. raimondii genome (Fig. 4f), suggesting that expansion and contraction in the numbers of NBS-encoding genes in different cotton species may have altered their resistance to V. dahliae. Less than 20% of the NBS-encoding genes from each of the diploid cotton species could be aligned with available Gossypium hirsutum ESTs (Supplementary Table 15a). Similarly, only 9 of the 53 TN and TNL subfamily members reported in Figure 4 could be amplified in the tetraploid genome (Supplementary Table 15b). These results indicate that NBS-encoding genes have evolved rapidly in either diploid or allotetraploid cotton species.

Figure 4: Analysis of NBS-encoding genes and potential molecular targets for resistance to Verticillium wilt.

(a) Analysis of gene numbers in all NBS-encoding disease resistance gene families in G. arboreum (Ga), G. raimondii (Gr) and T. cacao (Tc). (b–d) Analysis of gene numbers in the TN subfamily (b), the TNL subfamily (c) and the N subfamily (d). Numbers in circles represent the number of family members in each genome, and gene numbers for the MRCA are shown in rectangles. Numbers with plus and minus signs indicate the numbers of duplicated and deleted genes, respectively. (e) Example of tandem repeat and gene deletion of several TN subfamily members in G. arboreum, G. raimondii and T. cacao. Solid lines link orthologous genes on different chromosomes, and dashed lines represent inferred orthologous relationships plus putative deletions. Sections of G. arboreum chromosome 3 (Ga03) and G. raimondii chromosome 7 (Gr07) are enlarged for clarity, whereas all other pseudochromosomes are shown according to the scale bar. (f) qRT-PCR analysis of induced gene expression in the TN and TNL subfamilies upon V. dahliae infection. hpi, hours post-infection.

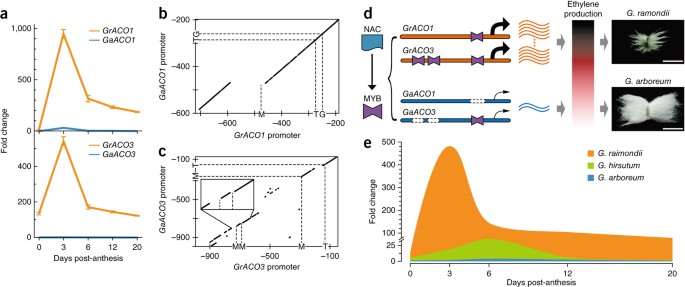

Ethylene is a key modulator of cotton fiber cell growth

Ethylene is an important signaling molecule that promotes cotton fiber elongation in G. hirsutum10,11,13. Products of the 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid oxidase (ACO) gene are involved in the last and rate-limiting step in ethylene biosynthesis during cotton fiber development10,11. In G. raimondii ovules collected at 3 days post-anthesis (dpa), the levels of ACO1 transcripts were ∼1,000-fold higher and the levels of ACO3 transcripts were ∼500-fold higher than in G. arboreum (Fig. 5a). These two genes were chosen because they accounted for >90% of all ACO transcripts during early fiber development (Supplementary Table 16). GrACO1 and GrACO3 showed 98% to 99% sequence identity in coding regions, respectively, with their counterparts in the G. arboreum genome (data not shown). Dot plots of promoter regions showed that a deletion of ∼130 bp beginning at −470 bp relative to the transcription start site of GaACO1 resulted in loss of a putative MYB-binding site (Fig. 5b). The pivotal role of MYB transcription factors in regulating cotton fiber development and secondary cell wall biosynthesis has previously been proposed33,34. Although GaACO3 and GrACO3 share one common MYB-binding site ∼150 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site, two small segments of mismatch located around −750 bp to −800 bp led to loss of two additional MYB-binding sites in G. arboreum (Fig. 5c). Very high levels of ACO transcripts in G. raimondii ovules in conjunction with an ethylene burst5,10 might force an early fiber senescence phenotype, whereas the inactivation of ACO gene transcription in G. arboreum ovules might be responsible for the short-fiber phenotype in this species (Fig. 5d). When all ACO transcripts were quantified from different cotton species (Fig. 5e; see Supplementary Table 17 for primer sequences), we found that fiber-specific upregulation of ACO expression, as in the case of G. hirsutum, seems to be required for normal fiber growth. Inactivation or overproduction of ACO, as in G. arboreum and G. raimondii, respectively, might suppress fiber development. Further functional characterization of biosynthesis and signaling pathways is required to pin down such a fundamental role for ethylene in the regulation of the growth of cotton fiber cells.

Figure 5: Ethylene modulates the elongation of cotton fiber cells.

(a) Comparisons of ACO1 and ACO3 transcript levels during fiber cell development in G. arboreum and G. raimondii. For calculation of fold change in expression, we arbitrarily set the expression level of each G. arboreum ACO transcript collected at 0 dpa to 1. Error bars, s.d. for three independent experiments. (b,c) Dot plots showing consensus in the promoter regions of ACO1 (b) and ACO3 (c) in the two cotton species. M, putative MYB-binding site; T, putative TATA box; G, putative GATA box. (d) Schematics showing the role of ethylene production in the regulation of cotton fiber elongation. Promoters for GrACO1 and GrACO3 (top) are potentially bound to more MYB protein than their counterparts in G. arboreum (bottom). Curved lines represent corresponding ACO transcripts, and the gradient bar shows the amount of ethylene production from low (white) to high (black). Scale bars, 1.0 cm. (e) Comparison of total ACO transcript levels in three cotton species on the basis of qRT-PCR analysis (n = 3 biological replicates). As shown in d, G. raimondii produces almost no mature fiber and G. arboreum produces short fiber of ∼1.5 cm in length; G. hirsutum produces fiber usually of >3.0 cm in length.

Discussion

Comparative genomic analysis showed that LTR insertions and expansions of LTR families contributed substantially to forming the double-sized G. arboreum genome relative to G. raimondii. The amount of sequence encompassing LTR-type retrotransposons increased from 348 Mb in G. raimondii5 to 1,145 Mb (or 67.6%) in G. arboreum, whereas the protein-coding capacities of these two species remained largely unchanged (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 7). Typically, data obtained from the whole-genome shotgun approach in plants with genome sizes exceeding a few hundred megabases are quite difficult to assemble satisfactorily because of their high TE content35,36,37. Here 90.4% of the 1,694-Mb G. arboreum genome, which is the largest of all sequenced eudicots19,20,21,22,23,24, was anchored and oriented. Problems related to high TE content were circumvented by using a high-density genetic map that involved 154 F2 RAD lines. A previous study showed an association between LTR number and ecogeography in barley, with more LTR copies present in the genomes of plants from sites with greater environmental stress37. All wild Gossypium species seem to be adapted to arid and stressful environments. The different number of LTRs in G. arboreum and G. raimondii does not support the ecogeography hypothesis. There must be other unknown mechanisms and causes for the dramatic increase in the number of LTRs in the domesticated species G. arboreum.

Qualitative differences in several NBS-encoding subfamilies and in ACO gene expression between the G. arboreum and G. raimondii genomes were observed. Our data thus identify prime targets in deciphering the molecular mechanisms that control resistance to Verticillium wilt and fiber cell development. We suggest that this G. arboreum genome will be an essential reference for the assembly of tetraploid cotton genomes and for evolutionary studies of Gossypium species. It also provides an essential tool for the identification, isolation and manipulation of important cotton genes conferring agronomic traits for molecular breeding and genetic improvement.

Methods

Strain selection.

We used DNA samples prepared from a specific genetic line (cultivar Shixiya1, SXY1) of the cultivated diploid cotton G. arboreum for sequencing and assembly. This line was brought to near homozygosity after 18 successive generations of self-fertilization. G. arboreum cv. Shixiya1 (SXY1) and G. raimondii D5-3 (CMD#10) plants were maintained in the National Wild Cotton Nursery in Sanya, Hainan Province, China.

DNA extraction, library construction and sequencing.

Fresh young leaves were collected, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction. We used the standard phenol-chloroform method for DNA extraction with RNase A and proteinase K treatment to prevent RNA and protein contamination10. Genomic libraries were prepared following the manufacturer's standard instructions and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. To construct paired-end libraries, DNA was fragmented by nebulization with compressed nitrogen gas, and DNA ends were blunted before adding an A base to each 3′ end. DNA adaptors with a single T-base 3′-end overhang were ligated to the above products. Ligation products were purified on 0.5%, 1% or 2% agarose gels, which each targeted a specific range of insert sizes. We constructed G. arboreum genome sequencing libraries with insert sizes of 180 bp, 250 bp, 350 bp, 500 bp, 800 bp, 2 kb, 5 kb, 10 kb, 20 kb and 40 kb.

Genome assembly.

All sequences were assembled with SOAPdenovo software16,17. Unusable reads were filtered out before assembly, including (i) reads that contained sequences with >10% “N” bases, (ii) reads with low-quality data (i.e., ≤7) for 65% of bases for short insert sizes or 80% of bases for long insert sizes, (iii) reads that contained >10 bp of adaptor sequence, (iv) reads with >10 bp that overlapped between two ends of reads of short insert size and (v) reads with identical sequences at the two ends.

The 193.6 Gb of clean data were assembled to contigs and scaffolds using the de Bruijn graph–based assembler of SOAPdenovo16,17 with the following four steps.

Constructing K-mer graphs. SOAPdenovo split reads with an insert size of <1,000 bases into _K_-mers to use in constructing the de Bruijn graphs. The parameters of this step in the cotton genome assembly were as follows: SOAPdenovo-127mer pregraph –s cotton_0308.lib –K 75 –R –p 24 –D –o GOSakoD>pregraph.log.

_Building contig_s. SOAPdenovo built contigs using the simplified de Bruijn graphs. The parameters of this step in the cotton genome assembly were as follows: SOAPdenovo-127mer contig –g GOSakoD –R >contig.log.

_Linking scaffold_s. SOAPdenovo aligned paired-end reads on the contig sequences. We subsequently calculated the total number of paired-end relationships between each pair of contigs and analyzed the rates of conflicting and consistent paired ends. A connecting relationship was regarded as a credible relationship between two contigs when that relationship met the given conditions. We then linked the contigs into scaffolds with N bases in a step-by-step manner from the paired-end reads with the shortest insert size to the paired-end reads with the longest insert size. We determined the orientation of the scaffolds on the basis of the paired-end relationship between reads and prescaffolds while we constructed the scaffolds. A reliable link was built between 2 contigs when there were ≥3 paired-end reads for short inserts or ≥5 paired-end reads for long inserts. We started with the smallest libraries, using the RANK parameter of the configuration files to control the order of the libraries. The parameters of this step in the cotton genome assembly were as follows: SOAPdenovo-127mer map –s cotton_0308.lib –p 16 –g GOSakoD –k 39 >map.log; SOAPdenovo-127mer scaff –g GOSakoD –F –p 16 >scaff.log.

Filling gaps. We used GapCloser to fill gaps in the scaffolds. This program makes use of reads for local assembly within the gaps by aligning the other ends of paired-end reads onto scaffolds. The parameters were as follows: GapCloser –a ./GOSakoD.scafSeq –b ./cotton_0330.lib –o ./GOSakoD.scafSeq.FG –t 64.

Genetic map construction.

Genetic linkage maps were constructed to develop the integrated genome map for anchoring the scaffolds, using 154 individuals from an F2 population of a cross between G. arboreum cultivars SXY1 and AnhuiFuyangZisedahua (AFZ). Young leaves of parents and individuals from the F2 population were collected for DNA extraction using the Plant Genomics DNA kit (Qiagen). Genomic DNA from this mapping population was digested with the restriction endonuclease EcoRI and processed into RAD libraries38. Every 20 cotton individuals were pooled into 1 sequencing library with nucleotide multiplex identifiers (4, 6 and 8 bp), and each sequencing library was barcoded. Approximately 1,600 Mb of 50-bp reads (10 Mb of read data for each progeny on average) was generated on the HiSeq 2000 next-generation sequencing platform. The SNP calling process was carried out using the SOAP2+SOAPsnp pipeline39. JoinMap4.0 (ref. 40) was used to conduct the linkage analysis. A _χ_2 test was used to determine whether the RAD-based SNP markers corresponded with the expected segregation ratio. Unusable markers (P < 0.01) were filtered out before a genetic map was constructed. ABH-style markers were used to build the main framework of 13 linkage groups, and a logarithm of odds (LOD) score of 7 was initially set as the linkage threshold for linkage group identification. AC-style markers were also included to expand the length of linkage groups by reducing the LOD value to 3. All high-quality markers were used to construct the consensus maps with the F2 population in JoinMap4.0. We calculated the recombination fractions between all pairs of SNP markers in a scaffold and chose the SNP marker that had the minimum recombination fraction in the sum. Scaffold order was determined by tag SNPs, and inner SNPs were then used to orient the scaffolds.

Annotation of transposable elements.

We searched the genome for tandem repeats using the software program Tandem Repeats Finder41. Both homology-based and de novo approaches were used to find TEs. The homology-based approach involved applying commonly used databases of known repetitive sequences along with such programs as RepeatProteinMask and RepeatMasker42. To identify DNA-level TEs, we used Repbase43 along with a database of plant repeating sequences and our de novo TE library to find repeats with RepeatMasker. We used four software programs, LTR_FINDER44, PILER45, RepeatModeler and RepeatScout46, to generate the de novo repeat library. These programs predict repeats in different ways. LTR_FINDER retrieves full-length LTR retrotransposons, which usually contain ∼18 bp of sequence that is complementary to the 3′ tail of certain tRNAs. PILER searches for repeats in the genome by aligning the genome with itself. RepeatScout builds a consensus sequence on the basis of lmer using the fit-preferred alignment score. RepeatModeler uses two ab initio repeat prediction programs (RECON and RepeatScout), which identify repeat element boundaries and family relationships among sequences. Intact LTRs were predicted using LTR_STRUC47 Windows-based software, and solo LTRs were predicted on the basis of comparison with intact ancestor LTRs. Single-copy gene families were used to construct the phylogenetic tree, and syntenic blocks were identified by MCscan48.

Gene prediction.

Homology-based gene prediction. The target locations of homologous proteins were obtained by aligning the protein sequences of A. thaliana, Carica papaya, Populus trichocarpa, G. raimondii, Populus trichocarpa, T. cacao and Vitis vinifera to the G. arboreum genome using TBLASTN with an _E_-value parameter of 1 × 10−5. Proteins encoded by TEs were filtered out before alignment. We next extracted target sequences from the genome, including a 2,000-bp extension at both ends of the alignment with intron regions, and again aligned the homologous protein sequences to these DNA fragments using GeneWise49 (with parameters –trev –sum –genesf). Coding sequences were aligned against the genome using BLAT to generate spliced alignments, and overlapping sequences were filtered out to link the spliced alignments using PASA50.

De novo gene prediction. AUGUSTUS (version 2.5.5)51 and SNAP (version 2006-07-28)52 were applied for de novo gene prediction using gene model parameters trained by A. thaliana. We masked all TEs from the genome before gene prediction and filtered out all short coding regions that were <150 bp in length during the process.

Transcriptome alignment. We used TopHat53 to map raw reads of cDNA sequence to the G. arboreum genome sequence to identify potential areas of exons in addition to donor or receptor sites with the following parameters: –p 4-max-intron-length 20,000 –m 1 –r 20-mate-std-dev 20. Cufflinks53 software was used to assemble potential alignments to transcripts, with the following parameters: –I 20,000 –p 4. To obtain complete gene models, we used the fifth-order Markov model to predict ORFs.

Combination of all methods. Data derived from homology-based, de novo and transcriptome alignment methods were integrated to generate a consensus gene set by GLEAN54 with default parameters.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Gene Ontology (GO)55 terms for each gene were obtained from its corresponding InterPro entry. We used OrthoMCL56 to confirm the genes that were orthologous among four species (A. thaliana, G. arboreum, G. raimondii and T. cacao). All-versus-all BLASTP (E value < 1 × 10−5) comparison of all protein sequences for each species was performed, and orthologous genes were clustered by OrthoMCL (inflation parameter: 1.5). We performed multiple alignments of protein sequences with MUSCLE57 for each single-copy gene family and converted the protein alignments to coding sequences using a Perl script. Phase-1 sites were extracted from each family and concatenated to one supergene for every species, and Mrbayes 3.1.2 (ref. 58) was used to construct the phylogenetic tree. Branch-specific Ka/Ks ratios (the number of nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site, Ka, over the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site, Ks) were calculated using codeml in the PAML59 software package with the branch model.

Syntenic analysis and whole-genome alignment.

A BLASTP search (with an _E_-value cutoff of 1 × 10−5) was performed to identify paralogous genes. Syntenic blocks (with at least five genes per block) were identified by MCscan48. For the alignment results between these, each aligned block represented the orthologous pair derived from the common ancestor, and the sequences that contained the genes were used to show the intergenome relationships with their length information. The fourfold-degenerate value of the blocks was calculated as revised by the HKY model, and whole-genome alignment was carried out by LASTZ (see URLs) between G. raimondii and G. arboreum after repeat regions were first masked.

LTR analysis.

Intact LTRs from the A genome and D genome were predicted using LTR_STRUC47 Windows-based software. We constructed ancestor subfamilies on the basis of the following two rules: (i) family members had to share the same polypurine tract sequences and primer-binding-site sequences and (ii) the E value had to be <1 × 10−10 among transposable gene sequences. For each family, we aligned all intact LTRs with MUSCLE57 and manually corrected the alignments using MEGA5.5 (ref. 60). We then constructed ancestor sequences for this family using the cons program (contained in the EMBOSS package61). To find more solo LTRs, we used the ancestor sequences for different families as queries for LTR prediction based on the standard prediction pipeline, and we followed the 80-80-80 rule (identity, >0.8; align rate, >80%; alignment length, >80 bp)62 to find which family the solo LTRs belonged to. All intact LTRs and solo LTRs were used to calculate the insert time with the formula time = K/r (where K is the distance between all alignment pairs and r is the rate of nucleotide substitution). The value was set to 7 × 10−9, and K was calculated with the distmat program implemented in the EMBOSS package61 with the Kimura two-parameter model.

Analysis of disease resistance– and fiber development–related genes.

The largest class of characterized disease resistance (R) genes encodes intracellular proteins that contain a nucleotide-binding site (NBS) and C terminus with leucine-rich repeats (LRRs)63. These genes are rather abundant in plant genomes and have an important role in mediating resistance to pathogens19,64. Resistance-related genes were identified using the HMMER 3.0 (ref. 65) software package. CAFE66 was used to predict the expansion and contraction of gene numbers on the basis of the topological gene tree.

ACO genes in G. raimondii and G. arboreum were obtained on the basis of a homology search with the ACO genes in G. hirsutum. Dot plot figures were generated using a word size of 9. All fold-change values were calculated with respect to the G. arboreum expression level at 0 dpa. For qRT–PCR analysis, total RNA (∼2 μg) was reverse transcribed in a 20-μl reaction mixture using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). After the reaction, 1-μl aliquots were used as a template for PCR amplification with gene-specific primers. As an internal control, the UBQ7 transcript was used to quantify the relative transcript level of each target gene in each tissue type. Three biological replicates were analyzed for all qRT-PCR experiments.

URLs.

Cotton Genome Project (CGP), http://cgp.genomics.org.cn/; LASTZ, http://www.bx.psu.edu/miller_lab/; RepeatModeler, http://www.repeatmasker.org/RepeatModeler.html.

Accession codes.

The G. arboreum genome sequence and gene annotation information have been deposited at the Cotton Genome Project (CGP), available at http://cgp.genomics.org.cn/, and all raw sequencing data are accessible through the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession SRA150181.

Accession codes

Primary accessions

Sequence Read Archive

References

- Wendel, J. & Albert, V.A. Phylogenetics of the cotton genus (Gossypium): characterstate weighted parsimony analysis of chloroplast-DNA restriction site data and its systematic and biogeographic implications. Syst. Bot. 17, 115–143 (1992).

Article Google Scholar - Krapovickas, A. & Seijo, G. Gossypium ekmanianum (Malvaceae), algodon silvestre de la Republica Dominicana. Bonplandia 17, 55–63 (2008).

Article Google Scholar - Wendel, J., Brubaker, C., Alvarez, I. & Cronn, R. in Genetics and Genomics of Cotton, Vol. 3 (ed. Paterson, A.H.) 3–22 (Springer-Verlag, New York, 2009).

- Hendrix, B. & Stewart, J.M. Estimation of the nuclear DNA content of Gossypium species. Ann. Bot. 95, 789–797 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wang, K. et al. The draft genome of a diploid cotton Gossypium raimondii. Nat. Genet. 44, 1098–1103 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Paterson, A.H. et al. Repeated polyploidization of Gossypium genomes and the evolution of spinnable cotton fibres. Nature 492, 423–427 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Paterson, A.H. et al. The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature 457, 551–556 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Schnable, P.S. et al. The B73 maize genome: complexity, diversity, and dynamics. Science 326, 1112–1115 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hu, T.T. et al. The Arabidopsis lyrata genome sequence and the basis of rapid genome size change. Nat. Genet. 43, 476–481 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Shi, Y.-H. et al. Transcriptome profiling, molecular biological, and physiological studies reveal a major role for ethylene in cotton fiber cell elongation. Plant Cell 18, 651–664 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Qin, Y.-M. et al. Saturated very-long-chain fatty acids promote cotton fiber and Arabidopsis cell elongation by activating ethylene biosynthesis. Plant Cell 19, 3692–3704 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Pang, C.-Y. et al. Comparative proteomics indicates that biosynthesis of pectic precursors is important for cotton fiber and Arabidopsis root hair elongation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 2019–2033 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Qin, Y.-M. & Zhu, Y.-X. How cotton fibers elongate: a tale of linear cell-growth mode. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14, 106–111 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Pegg, G.F. & Brady, B.L. in Verticillium Wilts 552 (CABI, New York, 2002).

- Khadi, B.M., Santhy, V. & Yadav, M.S. in Cotton: Biotechnological Advances (ed. Zehr, U.B.) 15–44 (Springer, New York, 2010).

- Li, R. et al. The sequence and de novo assembly of the giant panda genome. Nature 463, 311–317 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Li, R. et al. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res. 20, 265–272 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Rong, J. et al. A 3347-locus genetic recombination map of sequence-tagged sites reveals features of genome organization, transmission and evolution of cotton (Gossypium). Genetics 166, 389–417 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Argout, X. et al. The genome of Theobroma cacao. Nat. Genet. 43, 101–108 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Schmutz, J. et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature 463, 178–183 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence and analysis of the tuber crop potato. Nature 475, 189–195 (2011).

- Velasco, R. et al. The genome of the domesticated apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.). Nat. Genet. 42, 833–839 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Tomato Genome Consortium. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature 485, 635–641 (2012).

- Varshney, R.K. et al. Draft genome sequence of pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan), an orphan legume crop of resource-poor farmers. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 83–89 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hawkins, J.S., Kim, H., Nason, J.D., Wing, R.A. & Wendel, J.F. Differential lineage-specific amplification of transposable elements is responsible for genome size variation in Gossypium. Genome Res. 16, 1252–1261 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhang, H.-B., Li, Y., Wang, B. & Chee, P.W. Recent advances in cotton genomics. Int. J. Plant Genomics 2008, 742304 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wikström, N., Savolainen, V. & Chase, M.W. Evolution of the angiosperms: calibrating the family tree. Proc. Biol. Sci. 268, 2211–2220 (2001).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lynch, M. & Conery, J.S. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science 290, 1151–1155 (2000).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Tang, H. et al. Unraveling ancient hexaploidy through multiply-aligned angiosperm gene maps. Genome Res. 18, 1944–1954 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Van de Peer, Y., Fawcett, J.A., Proost, S., Sterck, L. & Vandepoele, K. The flowering world: a tale of duplications. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 680–688 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Swigonová, Z. et al. Close split of sorghum and maize genome progenitors. Genome Res. 14, 1916–1923 (2004).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Collier, S.M. & Moffett, P. NB-LRRs work a “bait and switch” on pathogens. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 521–529 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Zhong, R., Lee, C., Zhou, J., McCarthy, R.L. & Ye, Z.-H. A battery of transcription factors involved in the regulation of secondary cell wall biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20, 2763–2782 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Machado, A., Wu, Y., Yang, Y., Llewellyn, D.J. & Dennis, E.S. The MYB transcription factor GhMYB25 regulates early fibre and trichome development. Plant J. 59, 52–62 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - International Barley Genome Sequencing Consortium. A physical, genetic and functional sequence assembly of the barley genome. Nature 491, 711–716 (2012).

- Ling, H.-Q. et al. Draft genome of the wheat A-genome progenitor Triticum urartu. Nature 496, 87–90 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kalendar, R., Tanskanen, J., Immonen, S., Nevo, E. & Schulman, A.H. Genome evolution of wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum) by BARE-1 retrotransposon dynamics in response to sharp microclimatic divergence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6603–6607 (2000).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Chutimanitsakun, Y. et al. Construction and application for QTL analysis of a Restriction Site Associated DNA (RAD) linkage map in barley. BMC Genomics 12, 4 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lam, H.M. et al. Resequencing of 31 wild and cultivated soybean genomes identifies patterns of genetic diversity and selection. Nat. Genet. 42, 1053–1059 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Stam, P. Construction of integrated genetic linkage maps by means of a new computer package: JoinMap. Plant J. 3, 739–744 (1993).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 573–580 (1999).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics Chapter 4, Unit 4.10 (2009).

- Jurka, J. et al. Repbase update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110, 462–467 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W265–W268 (2007).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Edgar, R.C. & Myers, E.W. PILER: identification and classification of genomic repeats. Bioinformatics 21 (suppl. 1), i152–i158 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Price, A.L., Jones, N.C. & Pevzner, P.A. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 21 (suppl. 1), i351–i358 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - McCarthy, E.M. & McDonald, J.F. LTR_STRUC: a novel search and identification program for LTR retrotransposons. Bioinformatics 19, 362–367 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Tang, H. et al. Synteny and collinearity in plant genomes. Science 320, 486–488 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Birney, E., Clamp, M. & Durbin, R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 14, 988–995 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Haas, B.J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 5654–5666 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W435–W439 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Korf, I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 5, 59 (2004).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Trapnell, C. et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 511–515 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Elsik, C.G. et al. Creating a honey bee consensus gene set. Genome Biol. 8, R13 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29 (2000).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Li, L., Stoeckert, C.J. Jr. & Roos, D.S. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13, 2178–2189 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 (2004).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542 (2012).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yang, Z. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 13, 555–556 (1997).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Tamura, K. et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Rice, P., Longden, I. & Bleasby, A. EMBOSS: the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 16, 276–277 (2000).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wicker, T. et al. A unified classification system for eukaryotic transposable elements. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 973–982 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Meyers, B.C., Kaushik, S. & Nandety, R.S. Evolving disease resistance genes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 8, 129–134 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - DeYoung, B.J. & Innes, R.W. Plant NBS-LRR proteins in pathogen sensing and host defense. Nat. Immunol. 7, 1243–1249 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Eddy, S.R. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics 14, 755–763 (1998).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - De Bie, T., Cristianini, N., Demuth, J.P. & Hahn, M.W. CAFE: a computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics 22, 1269–1271 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Mid-term Gene Bank for Cotton at the Institute of Cotton Research, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences for providing the original SXY1 seeds. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars (grant 31125020), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 90717009) and the 863 National High-Tech Research Development Program in China (grant 2013AA102601).

Author information

Author notes

- Fuguang Li, Guangyi Fan, Kunbo Wang, Fengming Sun, Youlu Yuan, Guoli Song, Qin Li and Zhiying Ma: These authors contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

- State Key Laboratory of Cotton Biology, Institute of Cotton Research of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Anyang, China

Fuguang Li, Kunbo Wang, Youlu Yuan, Guoli Song, Cairui Lu, Changsong Zou, Haihong Shang, Wuwei Ye, Xueyan Zhang, Hengling Wei, Zhifang Li, Kun Liu & Shuxun Yu - BGI-Shenzhen, Shenzhen, China

Guangyi Fan, Fengming Sun, Wenbin Chen, Xinming Liang, Weiqing Liu, Chengcheng Shi, Caiyun Gou, Xun Xu, Junyi Wang & Jun Wang - State Key Laboratory of Protein and Plant Gene Research, College of Life Sciences, Peking University, Beijing, China

Qin Li, Guanghui Xiao & Yu-Xian Zhu - Key Laboratory for Crop Germplasm Resources of Hebei, Agricultural University of Hebei, Baoding, China

Zhiying Ma & Guiyin Zhang - US Department of Agriculture–Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS), Crop Germplasm Research Unit, Southern Plains Agricultural Research Center, College Station, Texas, USA

Russell J Kohel, Richard G Percy & John Z Yu - Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

Jun Wang - King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Jun Wang - Macau University of Science and Technology, Macau, China

Jun Wang - Department of Medicine, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Jun Wang - State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Jun Wang

Authors

- Fuguang Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Guangyi Fan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kunbo Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Fengming Sun

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Youlu Yuan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Guoli Song

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Qin Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Zhiying Ma

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Cairui Lu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Changsong Zou

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Wenbin Chen

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xinming Liang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Haihong Shang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Weiqing Liu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Chengcheng Shi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Guanghui Xiao

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Caiyun Gou

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Wuwei Ye

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xun Xu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xueyan Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hengling Wei

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Zhifang Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Guiyin Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Junyi Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kun Liu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Russell J Kohel

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Richard G Percy

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - John Z Yu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yu-Xian Zhu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jun Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Shuxun Yu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

F.L., K.W., G.F., F.S., Y.Y., G.S., Jun Wang and S.Y. designed the analyses. G.F., F.S., X.X., W.C., X.L., C.G., W.L., C.S. and Junyi Wang performed sequencing, assembly and genome annotation. F.L., K.W., Y.Y., G.S., C.L., C.Z., H.S. and W.Y. managed the project. Q.L., C.L., C.Z. and Y.-X.Z. performed genome analysis and physical map integration. C.L., Q.L., C.Z., G.X., W.Y., X.Z. and H.W. prepared DNA and RNA samples and performed PCR analysis. G.S., K.W., Y.Y., C.L., H.S., Z.L., K.L. and G.Z. provided the homozygous seeds. Y.-X.Z., Q.L., C.Z., C.L. and G.X. performed transcriptome and lineage-specific gene functional analyses. Y.-X.Z., C.L., C.Z. and Q.L. conceived the project and wrote the manuscript. Jun Wang, Z.M., R.J.K., R.G.P. and J.Z.Y. conceived the project and revised the manuscript. S.Y. conceived and directed the project.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence toYu-Xian Zhu, Jun Wang or Shuxun Yu.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Integrated supplementary information

Supplementary Figure 1 The distribution of insert size of the mapped BAC ends.

Supplementary Figure 2 Distribution of average paired-end linkages on scaffolds of different sizes.

Supplementary Figure 3 _K_-mer analysis for estimating the genome size of G. arboreum.

The volume of _K_-mers is plotted against the frequency at which they occur. The left, truncated peak at low frequency and high volume represents _K_-mers containing essentially random sequencing errors, whereas the right distribution represents proper (putatively error-free) data. The total _K_-mer number is 43,099,162,547, and the volume peak is 25. The genome size can be estimated as (total _K_-mer number)/(volume peak), which is 1,724 Mb.

Supplementary Figure 4 Linkage groups of the G. arboreum genome.

Genetic distances are listed on the left of each group and respective marker IDs are listed on the right.

Supplementary Figure 5 Genetic versus physical map distance of the 13 G. arboreum chromosomes.

Supplementary Figure 6 Collinearity between the G. arboreum assembly and the tetraploid G. hirsutum genetic map reported previously18.

Supplementary Figure 8 In-depth study of a microsyntenic block on chromosome 7 of the G. arboreum (Ga07) and G. raimondii (Gr07) genomic sequence obtained from the JGI website, as reported by Paterson et al.6.

Yellow bars, gene models; green lines, syntenic gene pairs; blue bars, TEs present along the corresponding chromosomal locations in each genome. The total number of genes and TEs found in each region is shown beneath the respective schematic.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, F., Fan, G., Wang, K. et al. Genome sequence of the cultivated cotton Gossypium arboreum.Nat Genet 46, 567–572 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2987

- Received: 17 June 2013

- Accepted: 24 April 2014

- Published: 18 May 2014

- Issue Date: June 2014

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2987