Synapses and Alzheimer’s Disease (original) (raw)

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a major cause of dementia in the elderly. Pathologically, AD is characterized by the accumulation of insoluble aggregates of Aβ-peptides that are proteolytic cleavage products of the amyloid-β precursor protein (“plaques”) and by insoluble filaments composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein (“tangles”). Familial forms of AD often display increased production of Aβ peptides and/or altered activity of presenilins, the catalytic subunits of γ-secretase that produce Aβ peptides. Although the pathogenesis of AD remains unclear, recent studies have highlighted two major themes that are likely important. First, oligomeric Aβ species have strong detrimental effects on synapse function and structure, particularly on the postsynaptic side. Second, decreased presenilin function impairs synaptic transmission and promotes neurodegeneration. The mechanisms underlying these processes are beginning to be elucidated, and, although their relevance to AD remains debated, understanding these processes will likely allow new therapeutic avenues to AD.

In Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid plaques and soluble oligomers disrupt synaptic structure and function, particularly on the postsynaptic side. In addition, aberrant presenilin impairs synaptic transmission and promotes neurodegeneration.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a common neurodegenerative disease of the elderly, first described by the physician-pathologist Alois Alzheimer in 1907 (Maurer and Maurer 2003). Clinically, AD is characterized by progressive impairment of memory (particularly short-term memory in early stages) and other cognitive disabilities, personality changes, and ultimately, complete dependence on others. The most prevalent cause of dementia worldwide, AD afflicts >5 million people in the United States and >25 million globally (Alzheimer’s Association, http://www.alz.org). Age is the most important risk factor, with the prevalence of AD rising exponentially after 65 (Blennow et al. 2006). However, many cases of so-called AD above 80 yr of age may result from a combination of pathological dementia processes (Fotuhi et al. 2009). The apolipoprotein E (ApoE) gene is the most important genetic susceptibility factor for AD, with the relatively common ApoE4 allele (prevalence ∼16%) increasing the risk for AD threefold to fourfold in heterozygous dose (Kim et al. 2009).

The histopathological hallmarks of AD are amyloid plaques (extracellular deposits consisting largely of aggregated amyloid beta [Aβ] peptide that are typically surrounded by neurons with dystrophic neurites) and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs, intracellular filamentous aggregates of hyperphosphorylated tau, a microtubule-binding protein) (Blennow et al. 2006). The development of amyloid plaques typically precedes clinically significant symptoms by at least 10–15 yr. Amyloid plaques are found in a minority of nondemented elderly patients, who may represent a “presymptomatic” AD population. As AD progresses, cognitive function worsens, synapse loss and neuronal cell death become prominent, and there is substantial reduction in brain volume, especially in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus. The best correlation between dementia and histopathological changes is observed with neurofibrillary tangles, whereas the relationship between the density of amyloid plaques and loss of cognition is weaker (Braak and Braak 1990; Nagy et al. 1995). In addition to amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, many AD cases exhibit widespread Lewy body pathology. (Lewy bodies are intracellular inclusion bodies that contain aggregates of α-synuclein and other proteins.) Particularly in very old patients, considerable overlap between AD, frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, and vascular disease is observed, and pure AD may be rare (Fotuhi et al. 2009).

THE ROLE OF Aβ IN AD PATHOGENESIS

Strong, though not yet conclusive, evidence indicates that AD is caused by the toxicity of Aβ peptide, either in the form of a microaggregate or an amyloid deposit. Multiple forms of Aβ are derived by proteolytic cleavage from the type I cell-surface protein APP (amyloid precursor protein), with Aβ40 and Aβ42 being the dominant species (Kang et al. 1987). The term “amyloid hypothesis” broadly posits that excessive amounts of Aβ peptide in the brain—particularly Aβ42—are responsible for AD-related pathology, including amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, synapse loss, and eventual neuronal cell death (Hardy and Selkoe 2002; Tanzi and Bertram 2005; Blennow et al. 2006). The precise meaning of the amyloid hypothesis changed over the years, and differs among scientists. Originally, it was thought that the actual amyloid is pathogenic—hence the term “amyloid hypothesis.” The more current version of this hypothesis posits that Aβ (especially Aβ42) microaggregates—also termed “soluble Aβ oligomers” or “Aβ-derived diffusible ligands” (ADDLs)—constitute the neurotoxic species that causes AD (Haass and Selkoe 2007; Krafft and Klein 2010).

In addition to the fact that β-amyloid in the brain is a pervasive (and now, defining) feature of AD, two major findings support the amyloid hypothesis in its broader sense: the overproduction of Aβ42 in nearly all familial forms of AD, and the neurotoxic effects of Aβ.

Aβ peptides are derived by proteolytic cleavage from the transmembrane protein APP by the action of integral membrane proteases termed secretases (see Fig. 1). APP is cleaved sequentially: first by α-secretase or β-secretase, then by γ-secretase. In most cell types, the initial cleavage of APP is mediated by α-secretase rather than β-secretase, followed in both cases by cleavage by γ-secretase (Haass and Selkoe 2007). α-Secretase and β-secretase cleave at single sites in the extracellular domain of APP, whereas γ-secretase performs a sequential series of intramembranous cuts on the product of the α-cleavage or β-cleavage, giving rise to Aβ peptides and intracellular fragments (termed “AICDs” for “APP intracellular domains”) of varying length (Fig. 1). Aβ42 is more prone to aggregation and believed to be more neurotoxic than Aβ40 and other Aβ variants. In mammals, APP is a member of a gene family that includes APLP1 and APLP2 (APP-like protein1 and 2), which are also cleaved by α-, β-, and γ-secretases. Together, the actions of these proteases acting on APP and APLPs produce a large number of protein fragments and peptides, of which only Aβ42 and Aβ40 peptides from APP appear to aggregate in vivo, and to have pathogenic effects. Although APP is highly conserved evolutionarily, the sequence of Aβ is not, and Aβ derived from non-primates does not appear to aggregate or to cause neurotoxicity.

Figure 1.

APP processing and the formation of Aβ peptide. (A, middle) The full-length human amyloid precursor protein (APP), a single transmembrane protein with an intracellular carboxyl terminus. (Horizontal arrows) Specific protease cleavage sites. In the amyloidogenic pathway (to the left), sequential cleavage of APP by β-secretase and γ-secretase releases the soluble extracellular domain of APP (sAPPβ), Aβ peptide, and the intracellular carboxy-terminal domain of APP (AICD). Cleavage by α-secretase prevents formation of Aβ, instead producing sAPPα and p3 peptide. (CTF) Carboxy-terminal fragment of APP, before cleavage by γ-secretase. (B) Diagram of the APP polypeptide and sequence of Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides, with secretase cleavage sites indicated.

Nearly 100 mutations in presenilin-1 and presenilin-2 (PS1 and PS2, the catalytic subunits of γ-secretase) cause familial AD. Familial early-onset AD also results from multiple point mutations in APP that are clustered in and around the Aβ sequence. Strikingly, most of these AD-related mutations seem to increase either overall Aβ production or the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio (Tanzi and Bertram 2005; Blennow et al. 2006; Bettens et al. 2010). Moreover, mutations at the β-secretase cleavage site of APP (such as the Swedish mutation of APP) increase Aβ production by improving APP as a substrate for β-secretase (encoded by BACE1). Several mutations surrounding the γ-secretase cleavage site of APP are believed to favor the production of the more amyloidogenic Aβ42 over Aβ40. Finally, mutations in the middle of the Aβ peptide enhance or alter Aβ aggregation properties. For example, four different point mutations in a single residue (E693) were observed that have distinct effects on the biophysical properties of Aβ42 and on the clinical phenotype (e.g., see Tomiyama et al. 2008), strongly supporting the pathogenic significance of the Aβ peptides.

Duplications of the APP gene can also lead to familial early-onset AD, presumably by increasing Aβ production (Rovelet-Lecrux et al. 2006). APP lies on chromosome 21 in a region that is duplicated in Down’s syndrome, and the presence of an extra copy of APP may contribute to the early-onset Alzheimer’s-like pathology that characterizes Down’s syndrome. Viewed together, the fact that most mutations causing familial AD either increase Aβ production or shift the Aβ42/40 ratio toward Aβ42 provides strong evidence for a causal role of Aβ peptides in familial AD pathogenesis, although their role in sporadic AD remains less certain. However, there are some puzzling exceptions to the correlation of pathogenic mutations in presenilins with excess Aβ42 production, and at least some pathogenic mutations of presenilin cause nearly complete inactivation of γ-secretase activity toward APP (Heilig et al. 2010; Pimplikar et al. 2010).

The most recent version of the amyloid hypothesis (or Aβ hypothesis) suggests that AD arises from synaptic toxicity mediated by soluble microaggregates (also termed oligomers) of Aβ, leading to synaptic dysfunction and synapse loss (“synapse failure”) (Lambert et al. 1998; Selkoe 2002; Kamenetz et al. 2003; Cleary et al. 2005; Lesne et al. 2006; Haass and Selkoe 2007; Shankar et al. 2007; Krafft and Klein 2010). Aβ has been shown to be neurotoxic in mouse brain in mainly two different experimental paradigms: in transgenic mice that express human mutant APP and overproduce human Aβ40/42, and in slices from wild-type mice that are acutely exposed to various preparations of Aβ microaggregates. Many studies using these approaches are available; for example, as of spring 2011, the transgenic mouse line Tg2576 overexpressing mutant human APP alone was used in more than 600 papers. Despite the fact that both experimental paradigms increase Aβ concentrations, the pathological effects are substantially different between these paradigms, and it remains unclear how they are related to each other and to human AD. In the following, we briefly review the results obtained with these two experimental paradigms and then discuss the implications of these results for understanding AD. Note that because thousands of papers have been published using these paradigms, only selected studies are reviewed here.

TRANSGENIC APPROACHES TO PROBING Aβ NEUROTOXICITY

Mouse models of AD using transgenic expression of mutant human APP (sometimes together with mutant presenilins) have been intensely studied. These models produce high concentrations of Aβ in the brain and develop amyloid plaques with aging (Games et al. 1995; Hsiao et al. 1996) but exhibit either minimal or modest (5%–25%) degrees of neuronal loss, even at stages when amyloid plaque deposition is plentiful (Bondolfi et al. 2002). Loss of dendritic spines and synapses (or reduced expression of synaptic markers such as synaptophysin) are reported in the brains of transgenic APP or APP/PS mutant mice, but the loss is relatively small and not necessarily correlated with plaque deposition (Hsia et al. 1999; Mucke et al. 2000; Lanz et al. 2003; Boncristiano et al. 2005; Spires et al. 2005; Jacobsen et al. 2006). Although this seemingly argues against Aβ/amyloid being a major causative agent of neuronal death and synapse loss, it should be born in mind that even in human AD, extensive amyloid burden can exist for a decade or more before significant neurodegeneration and clinical cognitive dysfunction occur. (One argument would be that the slow course of disease exceeds the observation period available in AD transgenic mice, which incidentally also have a shortened life span relative to wild type.)

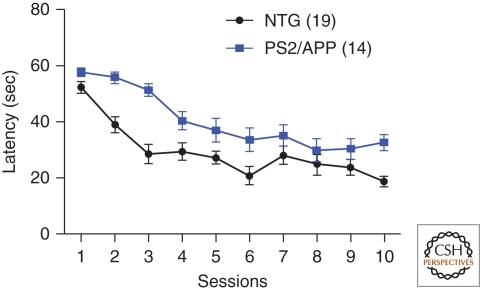

Whereas overall neuron loss is much less prominent in APP and APP/PS models of AD than in human postmortem specimens, careful studies of mouse models have detected significant reduction of neuron numbers in some specific regions of the brain, as well as decreased spine density in specific subdomains of neurons (e.g., see Perez-Cruz et al. 2011; Rupp et al. 2011 and references therein). Moreover, dysmorphic neuronal features, including spine/synapse loss, are particularly concentrated in the neighborhood of amyloid plaques (Spires et al. 2005; Meyer-Luehmann et al. 2008). In mutant APP/PS1 double transgenic mice, in vivo imaging revealed that plaques can form rapidly over ∼24 h, followed by recruitment of activated microglia 1–2 d later and development of dysmorphic neurites in the vicinity of the plaque over the subsequent days to weeks (Meyer-Luehmann et al. 2008). Despite the absence of overt neurodegeneration, transgenic mice expressing mutant APP generally display robust deficits in behavioral tasks, particularly of learning and memory (Fig. 2) (e.g., see Hsiao et al. 1996; Saura et al. 2005), suggesting that they are useful models of AD, and in particular, the amyloidosis aspect of AD (Ashe and Zahs 2010; Crews and Masliah 2010).

Figure 2.

Impaired spatial learning and memory in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Transgenic mice overexpressing human mutant APP and human mutant presenilin2 (PS2/APP mice) were tested in the acquisition of spatial memory in the Morris water maze at 6 mo of age. PS2/APP mice (n = 14) take significantly longer to reach a hidden platform during the 5 d of training (two sessions/day) than nontransgenic controls (NTG, n = 19). Repeated-measures ANOVA found a significant genotype (p < 0.001) and genotype × session interaction (p < 0.05). (Data kindly provided by William Meilandt, Tiffany Wu, and Kimberly Scearce-Levie [Genentech, Inc.].)

Synaptic function and plasticity have been extensively studied in APP and APP/PS transgenic mouse models of AD, with focus on CA1 and dentate gyrus subfields of the hippocampus. A comprehensive review of this topic is beyond the scope of this chapter (see also Lüscher and Malenka 2012). A variety of AD transgenic mice show abnormal synaptic transmission and impaired LTP, often well in advance of plaque formation (e.g., Chapman et al. 1999; Hsia et al. 1999; Roberson et al. 2011). However, the electrophysiological findings have been sometimes inconsistent and variable between different mouse models, regions of the hippocampus, and experimental conditions (Chong et al. 2011; Marchetti and Marie 2011).

Many pharmacological treatments, such as inhibition of calcineurin, have been reported to reverse the memory deficits or neuropathology of APP transgenic mice (Dineley et al. 2007; Taglialatela et al. 2009; Wu et al. 2010; Rozkalne et al. 2011). Moreover, a large number of genetic manipulations that ameliorate or aggravate the pathology observed in APP transgenic mice have been described, although some of the observed effects are likely indirect. Some of the results at first appear to be difficult to understand; for example, expression of EphB2 in the dentate gyrus of APP transgenic mice reversed the memory deficit in these mice (Cisse et al. 2011), even though this brain region is not generally thought to be required for the memory task used. Nevertheless, the genetic approach overall has led to important insights, especially when focused on genes known to interact with APP or otherwise implicated in human AD. Specifically, studies on the effect of the ApoE2, E3, and E4 variants of apolipoprotein ApoE have yielded major observations on the role of ApoE in Aβ clearance and plaque development (Kim et al. 2009; Castellano et al. 2011). Similarly, deletion of Mint/X11 proteins that bind to the cytoplasmic tail of APP significantly ameliorates the plaque load in transgenic mice expressing mutant APP (Ho et al. 2008). Furthermore, a recent study showed that the activity of caspase-3—the main executioner caspase in apoptosis—is elevated in the dendritic spines of hippocampal neurons of 3-month-old APP transgenic mice (line Tg2576) before the appearance of amyloid plaques and in the absence of cell death (D’Amelio et al. 2011). The elevation of caspase-3 activity correlated temporally with memory impairment, reduced spine density and size, altered excitatory synaptic transmission, and enhanced LTD. Remarkably, pharmacological inhibition of caspase-3 ameliorated the synaptic transmission, spine size, and memory deficits in these AD transgenic mice (D’Amelio et al. 2011). Increased caspase-3 activity is also reported in the human AD brain, and elevated levels of caspase-3 were observed in the postsynaptic density fraction of AD brain (Gervais et al. 1999; Stadelmann et al. 1999; Louneva et al. 2008). Moreover, suppression of LTP by Aβ (see below) is prevented by pharmacological inhibition or genetic knockout of caspase-3 (Jo et al. 2011). Thus, caspase-3—sublethally activated—may contribute to synapse dysfunction and loss in AD (Li et al. 2010c; D’Amelio et al. 2011). Importantly, antibodies to Aβ, which are at the forefront of potential AD therapies in clinical trials, can prevent the memory deficits in transgenic mouse models of AD (Dodart et al. 2002; Hartman et al. 2005; Klyubin et al. 2005).

Recent studies suggest that despite overall impairment of excitatory synaptic function, there may be aberrant hyperactivity in some brain circuits in APP transgenic mice and perhaps (more controversially) in human AD brains. J20 APP transgenic mice, and double transgenic mice expressing both APP and the tyrosine kinase FYN, exhibit spontaneous non-convulsive seizure activity in cortex and hippocampus and increased seizure severity after inhibition of GABAA receptors (Palop et al. 2007). This is associated with increased sprouting of inhibitory axons in the dentate gyrus, which may serve as a compensatory mechanism against excitotoxicity (Palop et al. 2007). In vivo Ca2+ imaging studies corroborate the idea that different subsets of neurons in AD transgenic mice can be hypoactive or hyperactive. The “hyperactive” neurons were found exclusively near amyloid plaques and appeared to result from a relative decrease in synaptic inhibition (Busche et al. 2008). In vivo imaging of aged APP transgenic mouse brain shows elevated intracellular Ca2+ and aberrant Ca2+ homeostasis in a subset of neurites in the close proximity of amyloid plaques (Kuchibhotla et al. 2008). The abnormal Ca2+ handling of neurons affected by amyloid-β was associated with loss of dendritic spines and neuritic dystrophy, mediated in part by the Ca2+-dependent protein phosphatase calcineurin (Wu et al. 2010). It is notable that calcineurin is also required for apoptosis and LTD, as well as for Aβ-induced spine loss and endocytosis of NMDA and AMPA receptors (Snyder et al. 2005; Hsieh et al. 2006; Shankar et al. 2007; Li et al. 2010c).

PROBING Aβ NEUROTOXICITY BY ACUTE EXPOSURE OF NEURONS TO Aβ OLIGOMERS

Synaptotoxic effects have been observed with soluble Aβ oligomers prepared from multiple sources such as synthetic Aβ peptides, APP-transfected cell culture supernatants, APP transgenic mouse brain, and even human AD brain tissue (Shankar et al. 2008). However, whether toxic soluble Aβ species represent the main toxic entity in AD, whether amyloid plaques are harmful, or whether both act synergistically remains a major question. Amyloid plaques could act as “reservoirs” that release soluble oligomeric Aβ. Indeed, synapse loss seems to be maximal very close to plaques and diminishes with distance from the plaque (Spires et al. 2005; Koffie et al. 2009). Thus, plaques, which are likely surrounded by a high concentration of soluble oligomeric Aβ, can still be central players in the damage to neurons and synapses in AD, even if they are not directly injurious per se.

At nanomolar to low micromolar concentrations, soluble Aβ oligomers impair excitatory synaptic transmission, inhibit long-term potentiation (LTP, a form of synaptic plasticity that is believed to be the cellular correlate of learning and memory), induce loss of dendritic spines, and impair rodent spatial memory (Selkoe 2002; Haass and Selkoe 2007; Crews and Masliah 2010). In addition to synaptic effects, soluble Aβ oligomers can elicit other features of AD, such as tau hyperphosphorylation, production of reactive oxygen species, and neuronal death (albeit weakly) (Lambert et al. 1998; Ashe and Zahs 2010). Given the acute toxic effects of exogenous Aβ microaggregates, it is striking that transgenic mice overproducing Aβ42 for many months exhibit relatively little neuronal cell death, suggesting that the Aβ peptides are rapidly neutralized in these mice, or other compensatory mechanisms exist in vivo.

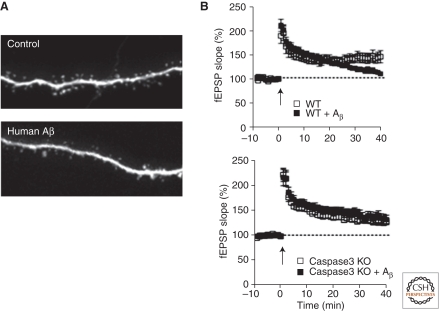

Aβ acutely alters synaptic plasticity in vitro: One of the most reproducible and widely studied effects is the inhibition of LTP in hippocampal slices (see Fig. 3) (Cullen et al. 1997; Lambert et al. 1998; Chapman et al. 1999; Freir et al. 2001; Walsh et al. 2002; Cleary et al. 2005; Townsend et al. 2006; Krafft and Klein 2010; Jo et al. 2011). In contrast to suppression of LTP, long-term depression (LTD) is unaffected or even enhanced by Aβ (Wang et al. 2002; Hsieh et al. 2006; Shankar et al. 2007, 2008). Thus, in terms of synaptic plasticity, exposure to Aβ seems to favor the weakening, and oppose the strengthening, of synapses. Consistent with its functional effects on LTP and LTD, prolonged exposure to Aβ leads to morphological loss of synapses (Fig. 3) (Hsieh et al. 2006; Lacor et al. 2007; Shankar et al. 2007, 2008; Wei et al. 2010). Aβ42, which is more prone to aggregation and more toxic than Aβ40, is also more effective at impairing LTP and reducing spine density (Kessels et al. 2010).

Figure 3.

Effects of exogenous Aβ on dendritic spines and long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices. (A) Loss of dendritic spines induced by exposure to Aβ oligomers isolated from human AD brains. (Top) Image of an apical dendrite of a control CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neuron in an organotypic slice culture, showing the normal high density of dendritic spines. (Bottom) A similar neuron in a slice that has been exposed to ∼1 nm soluble Aβ oligomers derived from postmortem human AD brain. Prolonged exposure to Aβ oligomers from a variety of sources leads to loss of ∼50% of dendritic spines and of functional glutamatergic synapses. These images were acquired during the study described by Shankar et al. (2008) and are reprinted with permission from one of the authors. (B, top) Sustained long-term potentiation (LTP) is readily inducible by tetanic stimulation in untreated wild-type (WT) acute hippocampal slices (open symbols), but is blocked by exposure of the slice to soluble Aβ oligomers, especially at later time points (filled symbols). (Bottom) LTP is also inducible in caspase-3 knockout slices, but it is not suppressed by Aβ oligomers, indicating that caspase-3 is required for Aβ suppression of LTP. (These data were acquired by Kimberly Moore Olsen during the study described by Jo et al. [2011].)

Based on transfection experiments in which APP or βCTF (the APP fragment remaining after β-secretase cleavage) (see Fig. 1) is overexpressed in hippocampal slice cultures, Aβ appears to impair glutamatergic transmission by promoting the internalization of postsynaptic glutamate receptors, which is associated with loss of dendritic spines (Hsieh et al. 2006). In this experimental model, Aβ-induced synaptic depression shows similarity with LTD, which is also mediated by the endocytosis of AMPA receptors and associated with shrinkage and/or loss of dendritic spines (Malenka and Bear 2004; Zhou et al. 2004). Moreover, the synaptic depression induced by APP/Aβ overexpression in neurons requires second-messenger pathways necessary for LTD, such as calcineurin; it can be blocked by overexpression of an AMPA receptor mutant that also prevents LTD (Hsieh et al. 2006). In this context, it is interesting that endocytosis abnormalities are present early in AD (Pimplikar et al. 2010). Moreover, both LTD and AMPA receptor internalization require the activation of caspase-3 via the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis (Li et al. 2010c), a pathway that is also implicated in the neurotoxicity of Aβ. Indeed, excessive mitochondrial fission has been implicated in Aβ-induced spine loss and neuronal toxicity (Cho et al. 2009). In general, however, exogenously added Aβ has few immediate effects on basal AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission (Shankar et al. 2007; Jo et al. 2011), suggesting that strong basal synaptic depression might require prolonged Aβ overproduction from transfection of APP or βCTF. Nevertheless, it is conceptually useful to think of Aβ-triggered signaling mechanisms as promoting AMPA receptor internalization, thereby impairing LTP and favoring LTD.

It should be remembered that experiments showing the detrimental effects of Aβ on synapses typically use high concentrations of soluble Aβ oligomers, or overexpression of APP constructs that produce Aβ at high local concentrations; these manipulations may or may not be relevant in vivo or in AD. Moreover, experiments based on APP overexpression cannot exclude the possibility that other non-Aβ products of APP processing are involved in the pathogenesis or modulate the action of Aβ (see below).

The loss of synapses is one of the best anatomical correlates of cognitive deficits in human AD and a better disease predictor than the amyloid plaque load (Terry et al. 1991). Synapse loss is likely a morphological reflection of the synaptic dysfunction that begins early in the disease. Application of Aβ oligomers reduces the density of spines in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures and dissociated cultured neurons (Fig. 3) (Hsieh et al. 2006; Calabrese et al. 2007; Lacor et al. 2007; Shankar et al. 2007; Wei et al. 2010). The reduction in dendritic spine number occurs progressively over 5–15 d of exposure to Aβ in vitro (Shankar et al. 2007), as opposed to the 2-h exposure needed for inhibition of LTP by exogenously applied Aβ oligomers (Jo et al. 2011). Aβ-induced spine loss is associated with a decrease in glutamate receptors and requires the activity of calcineurin, which is a calcium-dependent protein phosphatase also necessary for LTD (Snyder et al. 2005; Hsieh et al. 2006; Shankar et al. 2007; Sun et al. 2009). It is widely believed that the synaptic dysfunction and synapse loss contribute to the cognitive deficits of patients with AD. Consistent with this idea, soluble Aβ can disrupt cognitive function after infusion into the CNS in mice (Cleary et al. 2005; Lesne et al. 2006; Shankar et al. 2008).

What intracellular signaling pathways are activated by Aβ? As discussed above, Aβ may stimulate—directly or indirectly—the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis, which can culminate in cell death or synaptic depression due to the subapoptotic activation of caspase-3. Aβ is also reported to trigger Ca2+ influx, excitotoxicity, and stress-related signaling pathways in neurons, which may exacerbate aging-related increases in oxidative stress, impaired energy metabolism, and defective Ca2+ homeostasis (Bezprozvanny and Mattson 2008). Pharmacological data suggest that oligomeric Aβ-induced Ca2+ influx occurs through postsynaptic NMDA receptors, and this can lead to excessive formation of reactive oxygen species (De Felice et al. 2007), as well as calpain activation and degradation of critical proteins (Kelly and Ferreira 2006). An excitotoxic action of Aβ via NMDA receptors could explain why memantine, a weak NMDA receptor antagonist, has modest efficacy as a cognition-enhancing drug in AD patients.

The protein kinase glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3; especially the isoform GSK3β) is implicated in Alzheimer’s disease because it phosphorylates tau and increases Aβ production and toxicity (Ryder et al. 2003; Bhat et al. 2004). Aβ stimulates GSK3 activity, and GSK3 inhibitors can abrogate the neurotoxicity of Aβ (Fitzjohn et al. 2008; Hu et al. 2009). Interestingly, GSK3 activation promotes NMDA receptor-dependent LTD and inhibits LTP in the hippocampus (Peineau et al. 2007), which is similar to the effects of Aβ.

The interpretation of the acute Aβ administration studies assumes the existence of an “Aβ receptor.” Indeed, Aβ oligomers have been reported to bind in a punctate synaptic pattern on excitatory neurons in dissociated culture (Lacor et al. 2004, 2007; Koffie et al. 2009; Lauren et al. 2009), suggesting the presence of such an Aβ receptor at synapses. Numerous Aβ receptor candidates have been proposed, including NMDA receptors (De Felice et al. 2007; Decker et al. 2010), glutamate transporters (Li et al. 2009), mGluR5 (Renner et al. 2010), α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (Wang et al. 2000; Dineley et al. 2001; Snyder et al. 2005), and cellular prion protein (Lauren et al. 2009). Some of these putative receptors are plausible and could potentially explain the synaptotoxic effects of Aβ. For example, direct Aβ binding may activate NMDA receptors, leading to excitotoxicity that causes the Aβ-induced spine loss and synaptic depression (Kamenetz et al. 2003; Wei et al. 2010). Aβ has also been reported to induce aberrant clustering and activation of mGluR5 receptors, leading to elevated postsynaptic intracellular calcium and synaptic defects that are prevented by mGluR5 antagonists (Renner et al. 2010). Alternatively, Aβ inhibition of glutamate re-uptake mechanisms may indirectly cause nonphysiological activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors (Li et al. 2009). Overall, it seems unlikely that there are multiple high-affinity-specific Aβ receptors, and considerable controversy exists about which, if any, of these receptors are functionally important for Aβ toxicity.

A new facet of the Aβ hypothesis emerged with the discovery that Aβ amyloid pathology can spread during the time course of months in mouse brain after infusion of Alzheimer’s brain extracts (Kane et al. 2000). More recent studies revealed that even when Aβ is first introduced into the peritoneum, it can “seed” amyloid deposition in the brain (Eisele et al. 2010). These new observations suggest that Aβ neurotoxicity may spread from cell to cell via a “prion-like” mechanism in which a disease-related Aβ conformation is capable of nucleating the conformational transformation of endogenous normal Aβ.

NORMAL FUNCTIONS OF APP AND APP PROCESSING

Despite strong evidence that APP processing and Aβ production are involved in the pathogenesis of AD—or at least in familial early-onset AD—the normal functions of APP remain elusive. Adding to the mystery is the fact that APP is widely expressed in non-neural tissues and gives rise to measurable levels of Aβ outside of the CNS, including in plasma. Most confounding, however, is the fact that, as described above, APP is a member of a gene family that includes APLP1 and APLP2, which are all processed by α-, β-, and γ-secretases. There is considerable evidence for functional redundancy among these three genes, but only APP is implicated in AD. Genetic studies revealed that double knockout of either APP and APLP2, or of APLP1 and APLP2, causes lethality, whereas double knockout of APP and APLP1 (which is expressed at lowest levels) does not (Heber et al. 2000). Among various phenotypes, these mice exhibit deficits in neuromuscular junction formation and changes in gene expression (Li et al. 2010a). Strikingly, the lethality or the neuromuscular junction phenotype of APP/APLP2 double-KO mice cannot be rescued by APP knockin mice in which only the extracellular sAPP β-secretase cleavage product of APP is produced (Li et al. 2010a), or in which the cytoplasmic tail of APP is truncated (Li et al. 2010b). Although the soluble sAPPβ fragment was unable to rescue the lethality of the double-KO mice, it did rescue some of the gene expression changes, providing evidence for a biological function of the extracellular sAPP fragment (Fig. 1) (Li et al. 2010a). One important implication of the mouse genetic analysis of APP is that the essential functions of APP and APLPs are likely mediated by conserved sequences among them, thus arguing against a normal function of the Aβ peptide.

A possible clue to the physiological function of APP is the activity-dependent regulation of Aβ production and/or secretion. Aβ secretion is enhanced by neural activity in vitro and in vivo (Kamenetz et al. 2003; Cirrito et al. 2005; Ting et al. 2007; Wei et al. 2010). In human brain, regions with high resting “default mode” activity by functional MRI imaging show a higher Aβ plaque load (Buckner et al. 2005). These findings suggest that synaptic activity regulates APP processing, although it is unclear whether the regulation occurs at the level of α/β- or γ-secretase. Given the fact that the resulting cleavage products derived from APP, APLP1, and APLP2 show high homologies in the sequences corresponding to the sAPP and the intracellular AICD fragment of APP, but none in the sequences corresponding to the Aβ peptides, it seems likely that the functional importance of the activity-dependent cleavage of APP and its homologs resides in the conserved sequences, with Aβ being perhaps an incidental side-product.

Holtzman and colleagues (Kang et al. 2009) used microdialysis to measure the amount of Aβ in vivo in the extracellular interstitial fluid of hippocampus. Extracellular Aβ varied with a diurnal rhythm, correlating with wakefulness in both wild-type and mutant APP transgenic mice. Sleep deprivation acutely elevated extracellular Aβ, apparently via enhanced orexin signaling (a neuropeptide system that promotes wakefulness). Remarkably, chronic sleep restriction significantly increased, and an orexin receptor antagonist decreased, amyloid plaque load in AD transgenic mice (Kang et al. 2009). Because wakefulness is associated with a net increase in brain synaptic activity, the control of Aβ by the sleep–wake cycle is consistent with the idea that neuronal activity is a key regulator of APP processing.

Finally, the cytoplasmic fragment of APP (APP intracellular domain, AICD) (see Fig. 1), which is released by γ-secretase cleavage, can translocate to the nucleus, regulate gene transcription, and affect calcium signaling, synaptic plasticity, and memory (Cao and Sudhof 2001; Gao and Pimplikar 2001; Ma et al. 2007). As a transcriptional regulator, AICD was proposed not to be a transcription factor like the Notch intracellular domain NICD, but to affect chromatin remodeling via binding to the histone acetyltransferase Tip60 (Cao and Sudhof 2001, 2004). Interestingly, transgenic mice overexpressing the AICD by itself exhibit AD-like features, including hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of tau, neurodegeneration, and memory deficits (Ghosal et al. 2009). These studies underscore the importance of considering the non-Aβ products of APP in the pathogenesis of AD.

PRESENILIN, APOE4, AND SYNAPTIC FUNCTION

As the catalytic component of γ-secretase and a common site of mutations underlying familial AD, presenilins have generally been thought of in the context of APP processing and Aβ production. However, presenilins have a multitude of substrates and functions beyond serving as γ-secretase for APP; thus, they can act independent of APP processing to affect synapse function and neurodegeneration (Shen and Kelleher 2007; Lee et al. 2010; Pimplikar et al. 2010).

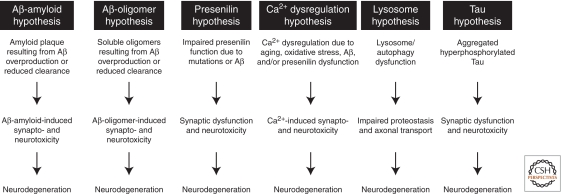

Conditional knockout of presenilins in the mouse forebrain results in impaired NMDA receptor function, defective LTP, defective learning and memory, and age-related neurodegeneration (Saura et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2009). By genetically disrupting presenilins specifically in presynaptic (CA3) or postsynaptic (CA1) neurons in hippocampus, Zhang et al. (2009) showed that presynaptic but not postsynaptic presenilin is required to support normal LTP as well as short-term plasticity and synaptic facilitation. Presynaptic disruption of presenilins reduced the probability of glutamate release during stimulus trains, most likely via effects on intracellular Ca2+ release from ER stores in presynaptic terminals (Zhang et al. 2009). Familial AD mutations in presenilins have been linked to abnormal Ca2+ handling in neurons, and presenilins may regulate Ca2+ leak from the ER (Zhang et al. 2010). These findings raise the possibility that presynaptic dysfunction might be an early component of synaptic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease, and that presenilins can affect synapses via a loss-of-function mechanism, as opposed to the gain-of-function increase in the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio that is typically assumed under the amyloid hypothesis (Fig. 4). Nevertheless, conditional genetic inactivation of PS1 can rescue learning deficits in the context of APP transgenic mice, at least in young APP transgenic mice (Saura et al. 2005).

Figure 4.

Pathogenic hypotheses for synaptic and neuronal toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. The specific hypotheses shown are not mutually exclusive, and, moreover, they likely “cross-talk” with each other. For instance, Aβ may induce tau hyperphosphorylation and aggregation, and presenilin mutations may cause lysosome and autophagy dysfunction (Pimplikar et al. 2010; Nixon and Yang 2011). Not all possible mechanisms of synaptic and neural toxicity are shown here (see text for additional examples).

The ApoE4 allele of ApoE—a major brain apolipoprotein—is a strong genetic risk factor for AD, but little is known about how it affects neuronal or synaptic function (Kim et al. 2009). Not only are human ApoE4 carriers more likely to get AD, but they also show earlier accumulation of amyloid plaque and a younger age of onset of dementia. This problem seems to arise because the ApoE4 isoform is associated with less efficient clearing of Aβ from the brain, rather than increased production of Aβ (Castellano et al. 2011). The ApoE receptors ApoER2 and VLDLR, which are expressed on neurons, aid in the transport of cholesterol from astrocytes to neurons, but also function as signaling receptors for Reelin, an extracellular protein that regulates neuronal migration in early development as well as synaptic function in the adult brain (Herz and Chen 2006). Reelin induces phosphorylation of NMDA receptor GluN2 subunits and enhances NMDA receptor activity and LTP, thereby countering the inhibitory effects of soluble Aβ on synaptic plasticity (Durakoglugil et al. 2009). ApoE4 is more effective than other ApoE isoforms in depleting ApoER2 as well as NMDA receptors and AMPA receptors from the neuronal surface; in this way, ApoE4 could exacerbate the synaptic impairment of AD by inhibiting the ability of Reelin to stimulate NMDA receptor function and LTP (Durakoglugil et al. 2009).

Aβ MAY NOT BE THE WHOLE STORY: WHAT CAUSES AD?

The cumulative evidence outlined above, on balance, supports the amyloid (or better, the Aβ) hypothesis, but leaves some space for doubt. Four main observations give rise to concerns about the amyloid hypothesis. First, as described above, not all AD-related mutations in APP and presenilins fit the concept of Aβ42 overproduction. Especially the presence of loss-of-function presenilin mutations that appear to decrease Aβ42 production is puzzling (Shen and Kelleher 2007). Second, no treatment targeting Aβ has yet shown convincing efficacy in phase III human clinical trials, although we all hope this will change soon given the large number of ongoing trials. It should be acknowledged, however, that some of the clinical trials lack pharmacodynamic evidence of adequately hitting the drug target. Moreover, an argument can be made that by the time AD patients are treated in those clinical trials published so far, the neuronal damage done by Aβ has already occurred and cannot be reversed simply by reducing Aβ. Third, Aβ accumulation or levels do not correlate with dementia in patients more than 80 yr of age; even in younger patients, neurofibrillary tangles are much better predictors of cognitive performance than Aβ plaques (e.g., see Bancher et al. 1993). Fourth, the inability of mouse models in which human Aβ42 is overproduced to recapitulate the neurodegeneration observed in human AD patients is concerning. However, it should be pointed out that even in human AD, there is a time lag of more than a decade between amyloid plaque deposition and clinical dementia.

Some of the arguments against the Aβ hypothesis can be explained by the notion that many patients with dementia above age 80 who are diagnosed with AD may actually either have a combination of AD with other types of dementias, especially vascular dementia, or not have AD at all (Fotuhi et al. 2009). If so, the lack of treatment success targeting solely Aβ and the lack of correlation between dementia and Aβ plaque load is not surprising, and future therapies should also consider therapies directed toward other targets or combination therapies or should be directed potentially toward a more defined patient population. An alternative explanation for the problems with the Aβ hypothesis is that the hypothesis is incorrect, and that the underlying pathogenesis is mediated by a different process. For example, it has been shown that presenilin loss of function induces neurodegeneration in mice (Saura et al. 2004), leading to the “presenilin hypothesis” of AD whereby AD pathogenesis is a loss-of-function state of γ-secretase (Fig. 4) (Shen and Kelleher 2007). The presenilin loss-of-function hypothesis explains the presence and nature of presenilin mutations in AD and is supported by mouse genetics. However, the presenilin hypothesis does not readily account for APP mutations in familial AD; in particular, this hypothesis is difficult to reconcile with the propensity of some APP mutations to produce cerebrovascular rather than neuronal lesions.

TAU AND SYNAPTIC FUNCTION

The accumulation within neurons of hyperphosphorylated and aggregated forms of tau as paired neurofilaments is thought to be a key step in AD pathogenesis. The characteristic tau pathology of AD lags behind amyloid plaques (by up to many years), but is more closely correlated with neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment in AD than is plaque pathology (Braak and Braak 1991). In the extended “amyloid cascade hypothesis,” tau hyperphosphorylation and cell death are considered to be downstream effects of Aβ accumulation (Hardy and Selkoe 2002). It is unclear how Aβ toxicity leads to tau pathology, and it is controversial whether there is a causal pathway connecting the two. Oligomeric Aβ applied to neurons can induce tau phosphorylation; however, tau can also form aggregates in the absence of Aβ pathology, as in the so-called tauopathies such as frontotemporal dementia (FTD), where mutations have been identified in the tau gene (MAPT) (Ballatore et al. 2007). Mutant tau is clearly toxic to neurons: Transgenic overexpression in the brain of a mutant tau that causes familial tauopathy results in age-dependent formation of NFTs, as well as synaptic impairment, neuronal death, and behavioral impairment. Interestingly, when expression of the mutant tau transgene was later turned off, memory function recovered, and neurodegeneration was halted despite persistence of tau aggregates in the brain, suggesting that the continuous presence of a soluble tau species rather than NFTs themselves is the toxic entity (Santacruz et al. 2005; Sydow et al. 2011).

In APP transgenic mouse models of AD, genetic deficiency of endogenous tau appears to mitigate Aβ synaptotoxicity and to prevent cognitive dysfunction and other behavioral abnormalities without reducing Aβ load, suggesting that tau is required somehow for Aβ-mediated toxicity (Roberson et al. 2007, 2011; Ittner et al. 2010). However, in these AD mouse models, aggregation of hyperphosphorylated tau is not observed, and it is unclear why deletion of tau would be beneficial. In fact, the function of tau in the basic biology of neurons, synaptic transmission, and overall brain function has not been elucidated in detail, and it is uncertain whether tau exerts a direct effect on synapses.

A major problem is that so little is known about the normal function of tau. A microtubule-binding protein, tau was regarded as primarily an axonal protein that regulates microtubule stability and transport (Dixit et al. 2008). However, hyperphosphorylated tau also accumulates in the somatodendritic compartment of neurons in AD (Ballatore et al. 2007; Li et al. 2011), and mislocalization of hyperphosphorylated tau in dendritic spines may disrupt glutamate receptor trafficking and hence synaptic function (Hoover et al. 2010). Provocative studies suggest that in the absence of tau, the postsynaptic targeting of non-receptor tyrosine kinase Fyn is disrupted (Ittner et al. 2010). Fyn—a component of the postsynaptic density of excitatory synapses—phosphorylates the NMDA receptor subunit GluN2B (also termed NR2B), thereby enhancing NMDA receptor surface expression and function, a process that is antagonized by the tyrosine phosphatase STEP (Braithwaite et al. 2006). Overexpression of Fyn exacerbates, whereas Fyn knockout ameliorates, the neuronal and cognitive deficits in APP transgenic mice, consistent with the idea that Fyn plays a role in AD, potentially in synergy with Aβ-mediated toxicity (Chin et al. 2005). Loss of postsynaptic Fyn could protect from Aβ toxicity by reducing the excitotoxic actions of NMDA receptors. In this respect, it is notable that the GluN2B subtype is particularly implicated in both excitotoxicity and Aβ-mediated toxicity (Liu et al. 2007; Li et al. 2009; Tu et al. 2010). What is puzzling about these findings, however, is that no major effects of tau deletion on synaptic transmission were reported, and none of the many papers in this area examine how synaptic function is changed in any of these conditions. Much more work needs to be done to clarify how tau hyperphosphorylation and aggregation contribute mechanistically to the synaptic deficits and neuronal death in AD.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

AD is a prevalent cause of dementia in the elderly and probably involves major dysfunctions of synapses caused by increased levels of soluble Aβ oligomers and/or decreased levels of presenilin function. Despite a vast amount of data that include descriptions of mutations in APP and presenilin genes causing AD, isoforms of ApoE genes predisposing to AD, mouse models replicating some of these genetic conditions, and biochemical studies of Aβ and APP processing, the pathogenesis of AD remains incompletely understood, and its relation to other forms of dementia continues to be unclear. Given the special vulnerability of axons, nerve terminals, and dendritic spines to injury, an axo-synaptic origin of neurodegeneration makes eminent sense, but it is still unknown whether a single pathogenic pathway underlies such synapse-based neurodegeneration, or whether AD neurodegeneration is mediated by a multitude of independent insults that work in combination to eventually annihilate a synapse and kill a neuron (see Fig. 4). Even fundamental biological questions—such as whether a biological receptor for Aβ exists, or what physiological functions presenilins perform independently of their role as catalytic subunits in γ-secretase—remain unanswered. Given these uncertainties, it seems likely that significant progress in understanding late-life neurodegeneration will require a better understanding of the neurobiology of aging and of the molecular regulation of synapses in the mature brain.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank William Meilandt, Tiffany Wu, and Kimberly Scearce-Levie for providing the behavioral data on APP/PS2 transgenic mice (Fig. 1), and Kimberly Olsen for providing the data on Aβ suppression of LTP (Fig. 2). This work is supported by Grants PO1AG0107701 (project 3, to T.C.S.) and RC2AG036614 (to T.C.S.).

Footnotes

Editors: Morgan Sheng, Bernardo Sabatini, and Thomas C. Südhof

REFERENCES

*Reference is also in this collection.

- Ashe KH, Zahs KR 2010. Probing the biology of Alzheimer’s disease in mice. Neuron 66: 631–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballatore C, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ 2007. Tau-mediated neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 663–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancher C, Braak H, Fischer P, Jellinger KA 1993. Neuropathological staging of Alzheimer lesions and intellectual status in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease patients. Neurosci Lett 162: 179–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettens K, Sleegers K, Van Broeckhoven C 2010. Current status on Alzheimer disease molecular genetics: From past, to present, to future. Hum Mol Genet 19: R4–R11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I, Mattson MP 2008. Neuronal calcium mishandling and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci 31: 454–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat RV, Budd Haeberlein SL, Avila J 2004. Glycogen synthase kinase 3: A drug target for CNS therapies. J Neurochem 89: 1313–1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H 2006. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 368: 387–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boncristiano S, Calhoun ME, Howard V, Bondolfi L, Kaeser SA, Wiederhold KH, Staufenbiel M, Jucker M 2005. Neocortical synaptic bouton number is maintained despite robust amyloid deposition in APP23 transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging 26: 607–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondolfi L, Calhoun M, Ermini F, Kuhn HG, Wiederhold KH, Walker L, Staufenbiel M, Jucker M 2002. Amyloid-associated neuron loss and gliogenesis in the neocortex of amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J Neurosci 22: 515–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E 1990. Alzheimer’s disease: Striatal amyloid deposits and neurofibrillary changes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 49: 215–224 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E 1991. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82: 239–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite SP, Paul S, Nairn AC, Lombroso PJ 2006. Synaptic plasticity: One STEP at a time. Trends Neurosci 29: 452–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Shannon BJ, LaRossa G, Sachs R, Fotenos AF, Sheline YI, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Morris JC, et al. 2005. Molecular, structural, and functional characterization of Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence for a relationship between default activity, amyloid, and memory. J Neurosci 25: 7709–7717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busche MA, Eichhoff G, Adelsberger H, Abramowski D, Wiederhold KH, Haass C, Staufenbiel M, Konnerth A, Garaschuk O 2008. Clusters of hyperactive neurons near amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Science 321: 1686–1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese B, Shaked GM, Tabarean IV, Braga J, Koo EH, Halpain S 2007. Rapid, concurrent alterations in pre- and postsynaptic structure induced by naturally-secreted amyloid-β protein. Mol Cell Neurosci 35: 183–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Sudhof TC 2001. A transcriptionally [correction of transcriptively] active complex of APP with Fe65 and histone acetyltransferase Tip60. Science 293: 115–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Sudhof TC 2004. Dissection of amyloid-β precursor protein-dependent transcriptional transactivation. J Biol Chem 279: 24601–24611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano JM, Kim J, Stewart FR, Jiang H, DeMattos RB, Patterson BW, Fagan AM, Morris JC, Mawuenyega KG, Cruchaga C, et al. 2011. Human apoE isoforms differentially regulate brain amyloid-β peptide clearance. Sci Transl Med 3: 89ra57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman PF, White GL, Jones MW, Cooper-Blacketer D, Marshall VJ, Irizarry M, Younkin L, Good MA, Bliss TV, Hyman BT, et al. 1999. Impaired synaptic plasticity and learning in aged amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. Nat Neurosci 2: 271–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin J, Palop JJ, Puolivali J, Massaro C, Bien-Ly N, Gerstein H, Scearce-Levie K, Masliah E, Mucke L 2005. Fyn kinase induces synaptic and cognitive impairments in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 25: 9694–9703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho DH, Nakamura T, Fang J, Cieplak P, Godzik A, Gu Z, Lipton SA 2009. _S_-Nitrosylation of Drp1 mediates β-amyloid-related mitochondrial fission and neuronal injury. Science 324: 102–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong SA, Benilova I, Shaban H, De Strooper B, Devijver H, Moechars D, Eberle W, Bartic C, Van Leuven F, Callewaert G 2011. Synaptic dysfunction in hippocampus of transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease: A multi-electrode array study. Neurobiol Dis 44: 284–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrito JR, Yamada KA, Finn MB, Sloviter RS, Bales KR, May PC, Schoepp DD, Paul SM, Mennerick S, Holtzman DM 2005. Synaptic activity regulates interstitial fluid amyloid-β levels in vivo. Neuron 48: 913–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisse M, Halabisky B, Harris J, Devidze N, Dubal DB, Sun B, Orr A, Lotz G, Kim DH, Hamto P, et al. 2011. Reversing EphB2 depletion rescues cognitive functions in Alzheimer model. Nature 469: 47–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary JP, Walsh DM, Hofmeister JJ, Shankar GM, Kuskowski MA, Selkoe DJ, Ashe KH 2005. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-β protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat Neurosci 8: 79–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews L, Masliah E 2010. Molecular mechanisms of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 19: R12–R20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen WK, Suh YH, Anwyl R, Rowan MJ 1997. Block of LTP in rat hippocampus in vivo by β-amyloid precursor protein fragments. Neuroreport 8: 3213–3217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amelio M, Cavallucci V, Middei S, Marchetti C, Pacioni S, Ferri A, Diamantini A, De Zio D, Carrara P, Battistini L, et al. 2011. Caspase-3 triggers early synaptic dysfunction in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci 14: 69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker H, Jurgensen S, Adrover MF, Brito-Moreira J, Bomfim TR, Klein WL, Epstein AL, De Felice FG, Jerusalinsky D, Ferreira ST 2010. _N_-Methyl-d-aspartate receptors are required for synaptic targeting of Alzheimer’s toxic amyloid-β peptide oligomers. J Neurochem 115: 1520–1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felice FG, Velasco PT, Lambert MP, Viola K, Fernandez SJ, Ferreira ST, Klein WL 2007. Aβ oligomers induce neuronal oxidative stress through an _N_-methyl-d-aspartate receptor-dependent mechanism that is blocked by the Alzheimer drug memantine. J Biol Chem 282: 11590–11601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dineley KT, Westerman M, Bui D, Bell K, Ashe KH, Sweatt JD 2001. β-Amyloid activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade via hippocampal α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: In vitro and in vivo mechanisms related to Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 21: 4125–4133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dineley KT, Hogan D, Zhang WR, Taglialatela G 2007. Acute inhibition of calcineurin restores associative learning and memory in Tg2576 APP transgenic mice. Neurobiol Learn Mem 88: 217–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit R, Ross JL, Goldman YE, Holzbaur EL 2008. Differential regulation of dynein and kinesin motor proteins by tau. Science 319: 1086–1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodart JC, Bales KR, Gannon KS, Greene SJ, DeMattos RB, Mathis C, DeLong CA, Wu S, Wu X, Holtzman DM, et al. 2002. Immunization reverses memory deficits without reducing brain Aβ burden in Alzheimer’s disease model. Nat Neurosci 5: 452–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durakoglugil MS, Chen Y, White CL, Kavalali ET, Herz J 2009. Reelin signaling antagonizes β-amyloid at the synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 15938–15943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisele YS, Obermuller U, Heilbronner G, Baumann F, Kaeser SA, Wolburg H, Walker LC, Staufenbiel M, Heikenwalder M, Jucker M 2010. Peripherally applied Aβ-containing inoculates induce cerebral β-amyloidosis. Science 330: 980–982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzjohn SM, Doherty AJ, Collingridge GL 2008. The use of the hippocampal slice preparation in the study of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Pharmacol 585: 50–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotuhi M, Hachinski V, Whitehouse PJ 2009. Changing perspectives regarding late-life dementia. Nat Rev Neurol 5: 649–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freir DB, Holscher C, Herron CE 2001. Blockade of long-term potentiation by β-amyloid peptides in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus in vivo. J Neurophysiol 85: 708–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Games D, Adams D, Alessandrini R, Barbour R, Berthelette P, Blackwell C, Carr T, Clemens J, Donaldson T, Gillespie F, et al. 1995. Alzheimer-type neuropathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F β-amyloid precursor protein. Nature 373: 523–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Pimplikar SW 2001. The γ-secretase-cleaved C-terminal fragment of amyloid precursor protein mediates signaling to the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci 98: 14979–14984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais FG, Xu D, Robertson GS, Vaillancourt JP, Zhu Y, Huang J, LeBlanc A, Smith D, Rigby M, Shearman MS, et al. 1999. Involvement of caspases in proteolytic cleavage of Alzheimer’s amyloid-β precursor protein and amyloidogenic Aβ peptide formation. Cell 97: 395–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal K, Vogt DL, Liang M, Shen Y, Lamb BT, Pimplikar SW 2009. Alzheimer’s disease-like pathological features in transgenic mice expressing the APP intracellular domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 18367–18372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C, Selkoe DJ 2007. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: Lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide. Nat Rev 8: 101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ 2002. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297: 353–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman RE, Izumi Y, Bales KR, Paul SM, Wozniak DF, Holtzman DM 2005. Treatment with an amyloid-β antibody ameliorates plaque load, learning deficits, and hippocampal long-term potentiation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 25: 6213–6220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heber S, Herms J, Gajic V, Hainfellner J, Aguzzi A, Rulicke T, von Kretzschmar H, von Koch C, Sisodia S, Tremml P, et al. 2000. Mice with combined gene knock-outs reveal essential and partially redundant functions of amyloid precursor protein family members. J Neurosci 20: 7951–7963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig EA, Xia W, Shen J, Kelleher RJ III 2010. A presenilin-1 mutation identified in familial Alzheimer disease with cotton wool plaques causes a nearly complete loss of γ-secretase activity. J Biol Chem 285: 22350–22359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz J, Chen Y 2006. Reelin, lipoprotein receptors and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci 7: 850–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho A, Liu X, Sudhof TC 2008. Deletion of Mint proteins decreases amyloid production in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 28: 14392–14400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover BR, Reed MN, Su J, Penrod RD, Kotilinek LA, Grant MK, Pitstick R, Carlson GA, Lanier LM, Yuan LL, et al. 2010. Tau mislocalization to dendritic spines mediates synaptic dysfunction independently of neurodegeneration. Neuron 68: 1067–1081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia AY, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Yu GQ, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA, Mucke L 1999. Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 3228–3233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G 1996. Correlative memory deficits, Aβ elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science 274: 99–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, Boehm J, Sato C, Iwatsubo T, Tomita T, Sisodia S, Malinow R 2006. AMPAR removal underlies Aβ-induced synaptic depression and dendritic spine loss. Neuron 52: 831–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Begum AN, Jones MR, Oh MS, Beech WK, Beech BH, Yang F, Chen P, Ubeda OJ, Kim PC, et al. 2009. GSK3 inhibitors show benefits in an Alzheimer’s disease (AD) model of neurodegeneration but adverse effects in control animals. Neurobiol Dis 33: 193–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ittner LM, Ke YD, Delerue F, Bi M, Gladbach A, van Eersel J, Wolfing H, Chieng BC, Christie MJ, Napier IA, et al. 2010. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-β toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Cell 142: 387–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen JS, Wu CC, Redwine JM, Comery TA, Arias R, Bowlby M, Martone R, Morrison JH, Pangalos MN, Reinhart PH, et al. 2006. Early-onset behavioral and synaptic deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 5161–5166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo J, Whitcomb DJ, Olsen KM, Kerrigan TL, Lo SC, Bru-Mercier G, Dickinson B, Scullion S, Sheng M, Collingridge G, et al. 2011. Aβ1–42 inhibition of LTP is mediated by a signaling pathway involving caspase-3, Akt1 and GSK-3β. Nat Neurosci 14: 545–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamenetz F, Tomita T, Hsieh H, Seabrook G, Borchelt D, Iwatsubo T, Sisodia S, Malinow R 2003. APP processing and synaptic function. Neuron 37: 925–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MD, Lipinski WJ, Callahan MJ, Bian F, Durham RA, Schwarz RD, Roher AE, Walker LC 2000. Evidence for seeding of β-amyloid by intracerebral infusion of Alzheimer brain extracts in β-amyloid precursor protein-transgenic mice. J Neurosci 20: 3606–3611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Lemaire HG, Unterbeck A, Salbaum JM, Masters CL, Grzeschik KH, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, Muller-Hill B 1987. The precursor of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature 325: 733–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JE, Lim MM, Bateman RJ, Lee JJ, Smyth LP, Cirrito JR, Fujiki N, Nishino S, Holtzman DM 2009. Amyloid-β dynamics are regulated by orexin and the sleep–wake cycle. Science 326: 1005–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BL, Ferreira A 2006. β-Amyloid-induced dynamin 1 degradation is mediated by _N_-methyl-d-aspartate receptors in hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem 281: 28079–28089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels HW, Nguyen LN, Nabavi S, Malinow R 2010. The prion protein as a receptor for amyloid-β. Nature 466: E3–E5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Basak JM, Holtzman DM 2009. The role of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 63: 287–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klyubin I, Walsh DM, Lemere CA, Cullen WK, Shankar GM, Betts V, Spooner ET, Jiang L, Anwyl R, Selkoe DJ, et al. 2005. Amyloid β protein immunotherapy neutralizes Aβ oligomers that disrupt synaptic plasticity in vivo. Nat Med 11: 556–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffie RM, Meyer-Luehmann M, Hashimoto T, Adams KW, Mielke ML, Garcia-Alloza M, Micheva KD, Smith SJ, Kim ML, Lee VM, et al. 2009. Oligomeric amyloid β associates with postsynaptic densities and correlates with excitatory synapse loss near senile plaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 4012–4017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krafft GA, Klein WL 2010. ADDLs and the signaling web that leads to Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology 59: 230–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchibhotla KV, Goldman ST, Lattarulo CR, Wu HY, Hyman BT, Bacskai BJ 2008. Aβ plaques lead to aberrant regulation of calcium homeostasis in vivo resulting in structural and functional disruption of neuronal networks. Neuron 59: 214–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Chang L, Fernandez SJ, Gong Y, Viola KL, Lambert MP, Velasco PT, Bigio EH, Finch CE, et al. 2004. Synaptic targeting by Alzheimer’s-related amyloid β oligomers. J Neurosci 24: 10191–10200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Furlow PW, Clemente AS, Velasco PT, Wood M, Viola KL, Klein WL 2007. Aβ oligomer-induced aberrations in synapse composition, shape, and density provide a molecular basis for loss of connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 27: 796–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, et al. 1998. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci 95: 6448–6453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanz TA, Carter DB, Merchant KM 2003. Dendritic spine loss in the hippocampus of young PDAPP and Tg2576 mice and its prevention by the ApoE2 genotype. Neurobiol Dis 13: 246–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauren J, Gimbel DA, Nygaard HB, Gilbert JW, Strittmatter SM 2009. Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by amyloid-β oligomers. Nature 457: 1128–1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Yu WH, Kumar A, Lee S, Mohan PS, Peterhoff CM, Wolfe DM, Martinez-Vicente M, Massey AC, Sovak G, et al. 2010. Lysosomal proteolysis and autophagy require presenilin 1 and are disrupted by Alzheimer-related PS1 mutations. Cell 141: 1146–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne S, Koh MT, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Yang A, Gallagher M, Ashe KH 2006. A specific amyloid-β protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature 440: 352–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Hong S, Shepardson NE, Walsh DM, Shankar GM, Selkoe D 2009. Soluble oligomers of amyloid β protein facilitate hippocampal long-term depression by disrupting neuronal glutamate uptake. Neuron 62: 788–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Wang B, Wang Z, Guo Q, Tabuchi K, Hammer RE, Sudhof TC, Zheng H 2010a. Soluble amyloid precursor protein (APP) regulates transthyretin and Klotho gene expression without rescuing the essential function of APP. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 17362–17367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Wang Z, Wang B, Guo Q, Dolios G, Tabuchi K, Hammer RE, Sudhof TC, Wang R, Zheng H 2010b. Genetic dissection of the amyloid precursor protein in developmental function and amyloid pathogenesis. J Biol Chem 285: 30598–30605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Jo J, Jia JM, Lo SC, Whitcomb DJ, Jiao S, Cho K, Sheng M 2010c. Caspase-3 activation via mitochondria is required for long-term depression and AMPA receptor internalization. Cell 141: 859–871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Kumar Y, Zempel H, Mandelkow EM, Biernat J, Mandelkow E 2011. Novel diffusion barrier for axonal retention of Tau in neurons and its failure in neurodegeneration. EMBO J 30: 4825–4837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wong TP, Aarts M, Rooyakkers A, Liu L, Lai TW, Wu DC, Lu J, Tymianski M, Craig AM, et al. 2007. NMDA receptor subunits have differential roles in mediating excitotoxic neuronal death both in vitro and in vivo. J Neurosci 27: 2846–2857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louneva N, Cohen JW, Han LY, Talbot K, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Trojanowski JQ, Arnold SE 2008. Caspase-3 is enriched in postsynaptic densities and increased in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol 173: 1488–1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Lüscher C, Malenka RC 2012. NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation and long-term depression (LTP/LTD). Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a005710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Lesne S, Kotilinek L, Steidl-Nichols JV, Sherman M, Younkin L, Younkin S, Forster C, Sergeant N, Delacourte A, et al. 2007. Involvement of β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) in amyloid precursor protein-mediated enhancement of memory and activity-dependent synaptic plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 8167–8172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Bear MF 2004. LTP and LTD: An embarrassment of riches. Neuron 44: 5–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti C, Marie H 2011. Hippocampal synaptic plasticity in Alzheimer’s disease: What have we learned so far from transgenic models? Rev Neurosci 22: 373–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer K, Maurer U 2003. Alzheimer: The life of a physician and career of a disease. Columbia University Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Luehmann M, Spires-Jones TL, Prada C, Garcia-Alloza M, de Calignon A, Rozkalne A, Koenigsknecht-Talboo J, Holtzman DM, Bacskai BJ, Hyman BT 2008. Rapid appearance and local toxicity of amyloid-β plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 451: 720–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucke L, Masliah E, Yu GQ, Mallory M, Rockenstein EM, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Johnson-Wood K, McConlogue L 2000. High-level neuronal expression of Aβ1–42 in wild-type human amyloid protein precursor transgenic mice: Synaptotoxicity without plaque formation. J Neurosci 20: 4050–4058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy Z, Esiri MM, Jobst KA, Johnston C, Litchfield S, Sim E, Smith AD 1995. Influence of the apolipoprotein E genotype on amyloid deposition and neurofibrillary tangle formation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 69: 757–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RA, Yang DS 2011. Autophagy failure in Alzheimer’s disease—locating the primary defect. Neurobiol Dis 43: 38–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palop JJ, Chin J, Roberson ED, Wang J, Thwin MT, Bien-Ly N, Yoo J, Ho KO, Yu GQ, Kreitzer A, et al. 2007. Aberrant excitatory neuronal activity and compensatory remodeling of inhibitory hippocampal circuits in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 55: 697–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peineau S, Taghibiglou C, Bradley C, Wong TP, Liu L, Lu J, Lo E, Wu D, Saule E, Bouschet T, et al. 2007. LTP inhibits LTD in the hippocampus via regulation of GSK3β. Neuron 53: 703–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Cruz C, Nolte MW, van Gaalen MM, Rustay NR, Termont A, Tanghe A, Kirchhoff F, Ebert U 2011. Reduced spine density in specific regions of CA1 pyramidal neurons in two transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 31: 3926–3934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimplikar SW, Nixon RA, Robakis NK, Shen J, Tsai LH 2010. Amyloid-independent mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J Neurosci 30: 14946–14954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner M, Lacor PN, Velasco PT, Xu J, Contractor A, Klein WL, Triller A 2010. Deleterious effects of amyloid β oligomers acting as an extracellular scaffold for mGluR5. Neuron 66: 739–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson ED, Scearce-Levie K, Palop JJ, Yan F, Cheng IH, Wu T, Gerstein H, Yu GQ, Mucke L 2007. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid β-induced deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Science 316: 750–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson ED, Halabisky B, Yoo JW, Yao J, Chin J, Yan F, Wu T, Hamto P, Devidze N, Yu GQ, et al. 2011. Amyloid-β/Fyn-induced synaptic, network, and cognitive impairments depend on tau levels in multiple mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 31: 700–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovelet-Lecrux A, Hannequin D, Raux G, Le Meur N, Laquerriere A, Vital A, Dumanchin C, Feuillette S, Brice A, Vercelletto M, et al. 2006. APP locus duplication causes autosomal dominant early-onset Alzheimer disease with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Nat Genet 38: 24–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozkalne A, Hyman BT, Spires-Jones TL 2011. Calcineurin inhibition with FK506 ameliorates dendritic spine density deficits in plaque-bearing Alzheimer model mice. Neurobiol Dis 41: 650–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp NJ, Wegenast-Braun BM, Radde R, Calhoun ME, Jucker M 2011. Early onset amyloid lesions lead to severe neuritic abnormalities and local, but not global neuron loss in APPPS1 transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging 32: 2324.e1–2324.e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder J, Su Y, Liu F, Li B, Zhou Y, Ni B 2003. Divergent roles of GSK3 and CDK5 in APP processing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 312: 922–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santacruz K, Lewis J, Spires T, Paulson J, Kotilinek L, Ingelsson M, Guimaraes A, DeTure M, Ramsden M, McGowan E, et al. 2005. Tau suppression in a neurodegenerative mouse model improves memory function. Science 309: 476–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saura CA, Choi SY, Beglopoulos V, Malkani S, Zhang D, Shankaranarayana Rao BS, Chattarji S, Kelleher RJ III, Kandel ER, Duff K, et al. 2004. Loss of presenilin function causes impairments of memory and synaptic plasticity followed by age-dependent neurodegeneration. Neuron 42: 23–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saura CA, Chen G, Malkani S, Choi SY, Takahashi RH, Zhang D, Gouras GK, Kirkwood A, Morris RG, Shen J 2005. Conditional inactivation of presenilin 1 prevents amyloid accumulation and temporarily rescues contextual and spatial working memory impairments in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J Neurosci 25: 6755–6764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ 2002. Alzheimer’s disease is a synaptic failure. Science 298: 789–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar GM, Bloodgood BL, Townsend M, Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ, Sabatini BL 2007. Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-β protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway. J Neurosci 27: 2866–2875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, Brett FM, Farrell MA, Rowan MJ, Lemere CA, et al. 2008. Amyloid-β protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med 14: 837–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Kelleher RJ III 2007. The presenilin hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence for a loss-of-function pathogenic mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 403–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EM, Nong Y, Almeida CG, Paul S, Moran T, Choi EY, Nairn AC, Salter MW, Lombroso PJ, Gouras GK, et al. 2005. Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking by amyloid-β. Nat Neurosci 8: 1051–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spires TL, Meyer-Luehmann M, Stern EA, McLean PJ, Skoch J, Nguyen PT, Bacskai BJ, Hyman BT 2005. Dendritic spine abnormalities in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice demonstrated by gene transfer and intravital multiphoton microscopy. J Neurosci 25: 7278–7287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadelmann C, Deckwerth TL, Srinivasan A, Bancher C, Bruck W, Jellinger K, Lassmann H 1999. Activation of caspase-3 in single neurons and autophagic granules of granulovacuolar degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Evidence for apoptotic cell death. Am J Pathol 155: 1459–1466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B, Halabisky B, Zhou Y, Palop JJ, Yu G, Mucke L, Gan L 2009. Imbalance between GABAergic and glutamatergic transmission impairs adult neurogenesis in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Stem Cell 5: 624–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sydow A, Van der Jeugd A, Zheng F, Ahmed T, Balschun D, Petrova O, Drexler D, Zhou L, Rune G, Mandelkow E, et al. 2011. Tau-induced defects in synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory are reversible in transgenic mice after switching off the toxic Tau mutant. J Neurosci 31: 2511–2525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taglialatela G, Hogan D, Zhang WR, Dineley KT 2009. Intermediate- and long-term recognition memory deficits in Tg2576 mice are reversed with acute calcineurin inhibition. Behav Brain Res 200: 95–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzi RE, Bertram L 2005. Twenty years of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid hypothesis: A genetic perspective. Cell 120: 545–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry RD, Masliah E, Salmon DP, Butters N, DeTeresa R, Hill R, Hansen LA, Katzman R 1991. Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: Synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol 30: 572–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting JT, Kelley BG, Lambert TJ, Cook DG, Sullivan JM 2007. Amyloid precursor protein overexpression depresses excitatory transmission through both presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 353–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama T, Nagata T, Shimada H, Teraoka R, Fukushima A, Kanemitsu H, Takuma H, Kuwano R, Imagawa M, Ataka S, et al. 2008. A new amyloid beta variant favoring oligomerization in Alzheimer's-type dementia. Ann Neurol 63: 377–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend M, Shankar GM, Mehta T, Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ 2006. Effects of secreted oligomers of amyloid β-protein on hippocampal synaptic plasticity: A potent role for trimers. J Physiol 572: 477–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu W, Xu X, Peng L, Zhong X, Zhang W, Soundarapandian MM, Balel C, Wang M, Jia N, Lew F, et al. 2010. DAPK1 interaction with NMDA receptor NR2B subunits mediates brain damage in stroke. Cell 140: 222–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]