Obesity and inflammation: the linking mechanism and the complications (original) (raw)

Abstract

Obesity is the accumulation of abnormal or excessive fat that may interfere with the maintenance of an optimal state of health. The excess of macronutrients in the adipose tissues stimulates them to release inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin 6, and reduces production of adiponectin, predisposing to a pro-inflammatory state and oxidative stress. The increased level of interleukin 6 stimulates the liver to synthesize and secrete C-reactive protein. As a risk factor, inflammation is an imbedded mechanism of developed cardiovascular diseases including coagulation, atherosclerosis, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and diabetes mellitus. It is also associated with development of non-cardiovascular diseases such as psoriasis, depression, cancer, and renal diseases. On the other hand, a reduced level of adiponectin, a significant predictor of cardiovascular mortality, is associated with impaired fasting glucose, leading to type-2 diabetes development, metabolic abnormalities, coronary artery calcification, and stroke. Finally, managing obesity can help reduce the risks of cardiovascular diseases and poor outcome via inhibiting inflammatory mechanisms.

Keywords: obesity, inflammation, interleukin 6, C reactive protein, adiponectin, linking mechanism

Introduction

Inflammation is an ordered sequence of events engineered to maintain tissue and organ homeostasis. The timely release of mediators and expression of receptors are essential to complete the program and restore tissues to their original condition [1]. Additionally, inflammation is a protective tissue response to injury or destruction of tissues that serves to destroy or dilute both the injurious agent and the injured tissues [2].

There are two types of inflammation; the first is acute inflammation that lasts for a short time and is characterized by edema and migration of leukocytes, and the second one is chronic inflammation that lasts for a long time and is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and macrophages and the proliferation of blood vessels and connective tissue [3].

It is considered a characteristic feature of metabolic syndrome [4], characterized by secretion of inflammatory adipokines usually from adipose tissue, such as leptin, interleukin (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and resistin [5]. Obesity, which is a feature of metabolic syndrome, was associated with chronic inflammation in obese subjects [6]. This review discusses the association of a number of inflammatory indictors with obesity, and sheds light on the associated health complications. Inflammatory indicators include IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP) as inflammatory markers, and adiponectin as an anti-inflammatory marker.

Interleukin 6

Interleukin 6 is a cytokine produced by many different cell types, including immune cells and adipose tissue, that mediates inflammatory responses [7]. The IL-6 receptor is also expressed in several regions of the brain, such as the hypothalamus, in which it controls appetite and energy intake, where it has a role in the regulation of energy homeostasis via suppressing lipoprotein lipase activity [8].

Unlike other cytokines, IL-6 is unusual in that its major effects take place at sites distinct from its origin and are consequent upon its circulating concentrations. For this reason, it is called the endocrine cytokine [9]. IL-6 exerts its action primarily by binding to the membrane-bound α receptor IL-6 receptor (IL-6R). Subsequently, the IL-6/IL-6R complex associates with glycoprotein 130 (gp130), leading to gp130-homodimer formation and signal initiation [10].

Obesity and IL-6

Obesity is considered a characteristic feature of metabolic syndrome [4]. The link between them has been attributed to the inflammatory process [6]. Obesity became a feature among rural populations like urban, as seen in Iran [11]. Obesity results from an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure, which means a positive energy balance [12]. The adipose tissue can be divided into two major types: brown and white adipose tissue [13]. In newborn humans, brown adipose tissue helps regulate energy expenditure by thermogenesis mediated by the expression of uncoupling protein-1 (UCP1) [14]. In adult humans, the amount of brown adipose tissue is inversely correlated to body mass index (BMI), especially in older people, suggesting a potential role of brown adipose tissue in adult human metabolism [14].

On the other hand, white adipose tissue is no longer considered an inert tissue mainly devoted to energy storage but is emerging as an active participant in regulating physiologic and pathologic processes, including immunity and inflammation [15]. Macrophages are components of adipose tissue and actively participate in its activities. Furthermore, cross-talk between lymphocytes and adipocytes can lead to immune regulation [16]. Adipose tissue produces and releases a variety of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors, including the adipokines leptin, adiponectin, and resistin, as well as cytokines and chemokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1 [5].

Positive associations between different measures of obesity and plasma IL-6 levels have been described [17]. It has been calculated that one third of total circulating concentrations of IL-6 originate from adipose tissue [18].

The overexpressed pro-inflammatory cytokines in obesity are considered the link between obesity and inflammation [19]. Adipose tissue responds to stimulation of extra nutrients via hyperplasia and hypertrophy of adipocytes. The nature of adipose tissue is heterogeneous, including endothelium, immune cells, and adipocytes [20]. With progressive adipocyte enlargement and obesity, the blood supply to adipocytes may be reduced, leading to hypoxia [21].

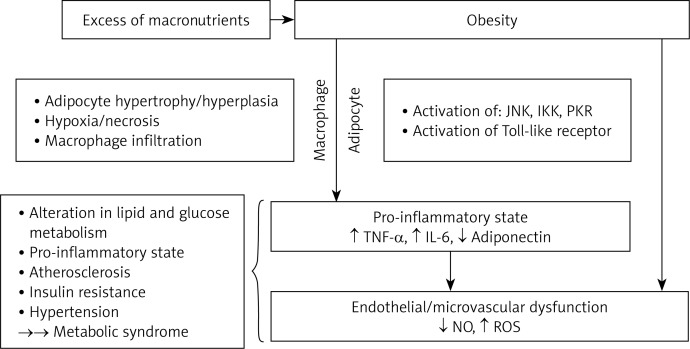

Hypoxia is proposed to be an inciting etiology of necrosis and macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, which leads to overproduction of pro-inflammatory mediators. This results in localized inflammation in adipose tissue that propagates overall systemic inflammation associated with the development of obesity-related comorbidities [22]. Amongst inflammatory mediators, three are produced by macrophages: TNF-α, IL-6, and adiponectin [15]. Furthermore, IL-6 strongly stimulates hepatocytes to produce and secrete CRP, indicating a state of inflammation [23]. Ellulu et al. [24] linked abdominal obesity with metabolic abnormalities via the inflammatory process; Figure 1 presents their illustration of it [24].

Figure 1.

Mechanisms linking abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome via inflammatory mediators [24]

_TNF-_α – tumor necrosis factor α, IL-6 – interleukin 6, NO – nitric oxide, ROS – reactive oxygen species, JNK – c-jun N-terminal kinase, IKK – inhibitor of k kinase, PKR – protein kinase R.

Moreover, accumulation of free fatty acids in obesity activates pro-inflammatory serine kinase cascades, such as IkB kinase and c-Jun N-terminal kinase, which in turn promotes adipose tissue to release IL-6 that triggers hepatocytes to synthesize and secrete CRP [25].

IllÁn-GÓmez et al. [26] evaluated the inflammatory mediators in morbidly obese patients after undergoing bariatric surgery. Levels of IL-6 significantly decreased after 12 months of surgery, IL-6 correlated significantly with BMI (r = 0.53, p < 0.001), and IL-6 was associated with high levels of CRP. Arnardottir et al. [27] assessed the interaction between obstructive sleep apnea with obesity in IL-6 individuals aged + 50 years. Patients were categorized into three groups based on BMI (< 30, 30–35, and ≥ 35 kg/m2), and IL-6 was distributed as follows: 1.3, 1.6, and 2.2 pg/ml, respectively, indicating the strong association of IL-6 with BMI.

Fontana et al. [18] tested the level of IL-6 and other inflammatory markers between the portal vein and peripheral artery among 25 morbidly obese patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery in St. Louis, Missouri. The study hypothesized that visceral fat promotes systemic inflammation by secreting inflammatory adipokines into the portal circulation that drains visceral fat. Mean plasma IL-6 concentration was about 50% greater in the portal vein than in the peripheral artery (p = 0.007). Additionally, the study showed that portal vein IL-6 concentration correlated directly with systemic CRP concentrations (r = 0.544, p = 0.005).

Wannamethee et al. [28] examined the association of IL-6 with metabolic abnormalities among non-diabetic elderly British individuals. After adjusting for age, levels of IL-6 increased by increasing both BMI and waist circumference (WC). Means of IL-6 were 2.23, 2.39, and 2.61 pg/ml; they were associated respectively with BMI: < 25.08, 25.08–27.79, and ≥ 27.8 kg/m2. Similarly for WC, means of IL-6 were 2.23, 2.33, and 2.69 pg/ml, and were associated respectively with WC: < 92.4, 92.4–100.1, and ≥ 100.2 cm.

Warnberg et al. [29] designed a study to clarify the association between BMI and low-grade inflammation in Spanish adolescents. Levels of IL-6 showed an elevation with increased BMI in both males and females, and the same results were achieved for TNF-α for both genders.

Complications of IL-6

Circulating inflammatory mediators including IL-6 have been hypothesized to play a substantial role in the development and alteration of several diseases [30–32]. IL-6 is a key cytokine in the acute-phase inflammatory response that stimulates CRP and fibrinogen production in the liver, release of white blood cells and platelets from bone marrow, and activation of endothelium and hemostasis [32]. Table I summarizes complications associated with increased IL-6 levels, accompanied by other markers, particularly CRP [33–51].

Table I.

Complications of elevated IL-6

| Authors | Biochemical factors | Complications |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular diseases: | ||

| Adar et al. [33] | IL-6, CRP, fibrinogen | Atherosclerosis and coagulation |

| Sarvottam and Yadav [34] | IL-6, adiponectin, endothelin-1 | Cardio-metabolic risks |

| Chen et al. [35] | Adiponectin, IL-6, CRP, oxidative stress | Metabolic syndrome |

| Danesh et al. [31] | IL-6, CRP | Coronary heart disease |

| Wannamethee et al. [28] | IL-6, CRP, FBG, TC, TG, HDL-c, fibrinogen, BP | Cardiovascular disease |

| Von Eynatten et al. [36] | IL-6, CRP, FBG, BP, adiponectin | Heart failure |

| Hansson [32] | IL-6 | Coronary artery disease |

| Fernandez-Real et al. [37] | IL-6, CRP, BP, TC, TG, FBG | Atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, blood pressure |

| Pradhan et al. [38] | IL-6, CRP | T2DM |

| Ridker et al. [39] | IL-6 | Myocardial infarction |

| Cancer diseases: | ||

| Taniguchi and Karin [40] | IL-6 | Colorectal and gastric cancers |

| Zhou et al. [41] | IL-6, CRP | Lung cancer |

| Sansone and Bromberg [30] | IL-6 | Metastatic progression |

| Ara and DeClerck [42] | IL-6 | Bone metastasis and cancer |

| Other diseases: | ||

| Matura et al. [43] | IL-6 | Pulmonary hypertension |

| Gluba et al. [44] | IL-6, TNF-α, leptin, TG, TC, BMI, WHR, BP, T2DM, MCP-1 | Chronic renal diseases |

| Arnardottir et al. [27] | IL-6, CRP | Obstructive sleep apnea |

| Fujishima et al. [45] | IL-6, IL-17F | Induction of IL-6 in keratinocytes causes inflammation in psoriasis |

| Gabay [46] | IL-6 | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Di Cesare et al. [47] | IL-6 | Periprosthetic infection in patients undergoing a reoperation at the site of a total hip or knee arthroplasty |

| Arican et al. [48] | IL-6, TNF-α, IL-8, IL-12, IL-18, IFN-γ | Active psoriatic patients have significantly higher levels of inflammatory mediators than controls |

| Musselman et al. [49] | IL-6 | Depression |

| Wirtz et al. [50] | IL-6, CRP | Inflammation after total knee and hip arthroplasties |

| Elder et al. [51] | IL-6 | IL-6 acts as an autocrine mitogen in psoriatic epidermis |

C-reactive protein

C-reactive protein is a sensitive marker of systemic inflammation that is synthesized by the liver. C-reactive protein is a nonspecific acute-phase reactant that has traditionally been used to detect acute injury infection and inflammation [52].

Biomedical evaluation of CRP

The risk categories were established by the American Heart Association (AHA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2003. The level of CRP should be less than 1.0 mg/l to reduce the inflammatory risk of metabolic diseases. A very high level of CRP (≥ 10.0 mg/l) indicates an infection status, and the test should be removed from epidemiological studies [53], and it should be repeated after 2 weeks of infection treatment [54]. Additionally, the stable and repeated elevated level of CRP for a while (≥ 10.0 mg/l) suggests that the condition is more likely to be chronic rather than acute inflammation [53]. Categories of CRP are shown in Table II.

Table II.

AHA/CDC risk categories of CRP level

| Risk categories | CRP level [mg/l] |

|---|---|

| Low | Less than 1.0 |

| Average | 1.0 to 3.0 |

| High | More than 3.0 |

| Very high | More than 10.0 |

According to the AHA and the CDC in 2002, the CRP test is a simple blood test that carries no risks, but could be affected by medications and other factors. Hormone therapy, pregnancy, birth control pills, and chronic inflammation (such as arthritis) can raise CRP levels. Cholesterol-lowering statin drugs and anti-inflammatories (such as aspirin, ibuprofen, diclofenac, and naproxen) may lower CRP levels [54].

In 2002, the AHA and the CDC co-sponsored a conference and workshop on several laboratory-based inflammatory markers: adhesion molecules, cytokines, fibrinogen, CRP, serum, amyloid A, and the white blood cell count. The workshop participants concluded that, of the tests studied, the CRP test had the most desirable characteristics. Assays for some markers, such as cytokines, were not sufficiently standardized for clinical use, and other markers that had reliable, commercially available assays, such as the white blood cells (WBC) count, were not as predictive or had not been demonstrated to be an independent predictor of CVD events. The conference recommended that, when CRP is used, it should be “measured twice, either fasting or non-fasting, with the average expressed in mg/l, in metabolically stable patients” [54].

C-reactive protein levels well below the conventional clinical upper limit of 1.0 mg/l have been associated with a 2- to 3-fold increase in risk of heart disease mortality in healthy adults. In a meta-analysis of seven prospective studies, elevated serum CRP has been shown to predict future risk of CHDs [55]. Recent studies have shown a positive independent association between atherosclerotic events and CRP [52, 56, 57], which acts as a proatherosclerotic factor by up-regulating angiotensin type-1 receptor expression [58]. Some of the complications of elevated CRP concentration are presented in Table III [59–80].

Table III.

Complications of elevated CRP

| Authors | Population | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Vadakayil et al. [59] | Patients with chronic plaque psoriasis | Elevated levels of CRP are a useful marker of psoriasis severity, and may be an independent risk factor for CVD |

| Takahashi et al. [60] | Psoriasis vulgaris patients | CRP level is increased in psoriasis, and can predict the future risk of cardio- and cerebrovascular disease |

| Ma et al. [61] | Patients with large artery atherosclerosis and small artery occlusion had higher levels of CRP, fibrinogen, and CXCL16 (chemokine) | |

| KöşÜş et al. [62] | Obese pregnant women are susceptible to the development of metabolic complications such as gestational diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and CVDs due to CRP and SCFT | |

| Kurtoglu et al. [63] | Heart disease patients | Increased risk of mitral annular calcification |

| Rajendran et al. [64] | Chennai population India | Acute myocardial infarction |

| Woodard et al. [65] | Women transitioning through menopause | Aortic stiffness |

| Lee et al. [66] | T2DM (free of CVDs) | Major adverse cardiovascular events |

| Kalhan et al. [67] | Young adults | Abnormal lung functions |

| Den Hertog et al. [68] | Ischemic stroke patients | Poor outcome or death |

| Devaraj et al. [69] | CRP impaired glycocalyx function “lines and protects endothelial luminal surface”, leading to endothelial dysfunction, resulting in atherogenesis | |

| Cirillo et al. [70] | Metabolic syndrome and progressive renal disease | |

| Hubel et al. [71] | Pregnant women | Preeclampsia |

| Trichopoulos et al. [72] | CRP was a strong carcinogenic factor, associated with liver cancer, lymphoma, bladder cancer, leukemia | |

| Erlinger et al. [73] | CRP strongly correlated with colorectal cancer | |

| Seddon et al. [74] | Geriatrics | Macular degeneration |

| Russell et al. [75] | Polymorphism at the CRP locus influences gene expression and predisposes to systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Sesso et al. [76] | Prospective with normal BP in female aged ≥ 45 years | Hypertension |

| Stuveling et al. [77] | Renal disease patients | Renal function loss due to glomerular hyperfiltration |

| Ridker [78] | Heart attack and stroke | |

| Han et al. [79] | Prospective in Caucasians (Mexico), CRP predicted T2DM and metabolic syndrome in adults | |

| Mallya et al. [80] | CRP concentration closely reflects activity of rheumatoid arthritis |

Obesity and CRP

In 2010, a meta-analysis by the Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration identified that each increase of CRP by 1 standard deviation was associated with a 60% increase of vascular risk. Many cross-sectional studies have linked obesity with CRP [81]. Each degree of obesity was related directly to CRP, regardless of ethnicity characteristics and sex [82]. Also, a strong correlation was obtained by the meta-regression analysis between obesity and CRP in both adults and children.

The link between obesity and elevated serum level of CRP has been well explained by the pathophysiological mechanism. The central role of inflammation is attributed to the liver, as it drains free fatty acids, and circulating triacylglycerol promoting release of cytokines (IL-6) by adipose tissue, which in turn triggers hepatocyte expression and release of CRP [81]. The cross-sectional evidence addressed the link between obesity and CRP. Klisic et al. [83] measured CRP and metabolic markers among normal weight and overweight postmenopausal women in Montenegro. Significantly higher levels of CRP and triglyceride (TG) (p = 0.005, p < 0.001; respectively) in overweight women were reported compared to normal weight women. Similarly, Dayal et al. [84] identified the role of anthropometric measurements with CRP in Indian children. By using a multiple logistic regression analysis, for each 1.0 unit increase in BMI, the odds ratio of CRP increased by 37% (95% CI: 1.23–1.53, p < 0.001).

Stępień et al. [6] evaluated the association between inflammatory markers and obesity indices in normo- and hypertensive subjects; waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), which is a sensitive index of visceral obesity, was associated with chronic inflammation in obese hypertensive subjects, and body adiposity index (BAI) correlated with CRP independently of hypertension and sex. Likewise, Kawamoto et al. [85] studied the association between BMI and CRP after considering the confounding factors by multiple linear regression analysis. Body mass index, age, smoking habits, and TG were significant predictors of CRP. In addition, Fontana et al. [18] evaluated the role of visceral adiposity in generating inflammation in extremely obese adults possessing BMI 54.7 ±12.6 kg/m2, WC 150 ±10 cm, and aged 42 ±9 years. By considering the blood from the portal vein and radial artery, IL-6 was about 50% greater in the portal vein than in the radial artery (p = 0.007), and portal vein IL-6 correlated directly with systemic CRP (r = 0.544, p = 0.005). Finally, Ajani et al. [86] determined the prevalence of high CRP (≥ 3 mg/l) among free diabetes or heart diseases, and normo-lipidemic adults in the USA. CRP was related directly to BMI: 31.4–35.1% for overweight participants, and 52.5–60.9% for obese participants. After omitting individuals with CRP ≥ 10 mg/l, the adjusted prevalence of high CRP (≥ 3 mg/l) was 14.4% for normal weight, 31.6% for overweight, and 36.0% for obese.

Subcutaneous abdominal fat thickness (SCFT) is important for predisposition to metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. In pregnant women between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation, KöşÜş et al. [62] evaluated maternal SCFT and metabolic changes. The results indicated a significant association between SCFT and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c). Whereas higher levels of CRP were found in 47.9% of cases with SCFT over 15 mm.

On the other hand, many factors such as age, gender, smoking, and sedentary lifestyle have correlated closely with CRP and systemic cytokine concentrations [54, 87, 88]. Furthermore, elevated CRP level may be associated with some pathological conditions and used as a marker for more severe conditions; e.g. high levels of CRP among patients with myocardial infarction may lead to left ventricular systolic dysfunction [89]. Sleep restriction was also correlated with cardiovascular diseases (CVD), because it was hypothesized to elevate CRP [90]. Likewise, obstructive sleep apnea was linked directly with the progression of CVDs, which has been associated significantly with high CRP levels and BMI [27].

Shivpuri et al. [91] identified the impact of chronic stress in major life domains (relationship, work, sympathetic-caregiving, financial) in worsening CRP in men and women aged > 45 years. Moreover, women showed a slight higher stress level than men. Along the same line, Kwon et al. [92] found that plasma level of CRP was significantly higher in patients with pulmonary hypertension (“systolic pulmonary artery pressure ≥ 35 mm Hg”) than in individuals without hypertension.

Molecular link of IL-6 and CRP

C-reactive protein is synthesized and secreted primarily in human hepatocytes and is regulated mainly by IL-6 and IL-1 [23]. The induction of IL-6 and IL-1b could be inhibited by the farnesoid X receptor (FXR; NR1H4). FXR is a member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily that functions as a ligand-activated transcription factor and is highly expressed in the liver, intestine, kidney and adrenal glands [93]. FXR regulates many genes involved in bile acid synthesis and lipid and lipoprotein metabolism [94]. FXR can be activated by physiological concentrations of bile acids [95], or by potent synthetic FXR ligands including GW4064, 6a-ethyl-chenodeoxycholic acid (6ECDCA) and WAY-362450 [96]. Activation of FXR has been shown to induce eNOS expression in vascular endothelial cells and inhibit vascular smooth muscle cell inflammation by downregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 expression [97]. Furthermore, an agonist for the nuclear receptor, liver X receptor, also inhibited IL-6/IL-1b-induced CRP expression in human hepatocytes. This was shown to be mediated through inhibition of cytokine-induced NCoR clearance from the CRP promoter [98].

Adiponectin

Adiponectin is a protein hormone derived from adipocytes that has gained considerable importance due to its positive impacts on inflammation [99], atherosclerosis, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and insulin resistance [99–101]; thus, it links the adipose tissue directly with the cornerstones of metabolic abnormalities [102]. Adiponectin is a 247-amino acid peptide discovered in 1995 [103], which circulates at relatively high (2–20 µg/ml) serum concentrations [104], while Ouchi et al. [105] evaluated the levels typically ranging from 3–30 µg/ml, in normal human subjects.

In healthy non-metabolic subjects, adiponectin was accompanied by anti-inflammatory effects of T2DM, and reduced risk of atherosclerosis [106]. It increases local nitric oxide production, which in turn protects against endothelial dysfunction, and inhibits plaque initiation and thrombosis [107]. Thus it acts as a vasoprotective factor [108] and reduces oxidative stress [109]. In the liver, adiponectin improves insulin sensitivity, decreases uptake of non-esterified fatty acids, reduce gluconeogenesis, and increases the oxidation process [110]. Centrally, it has high potency in regulating weight gain and increasing energy expenditure [111].

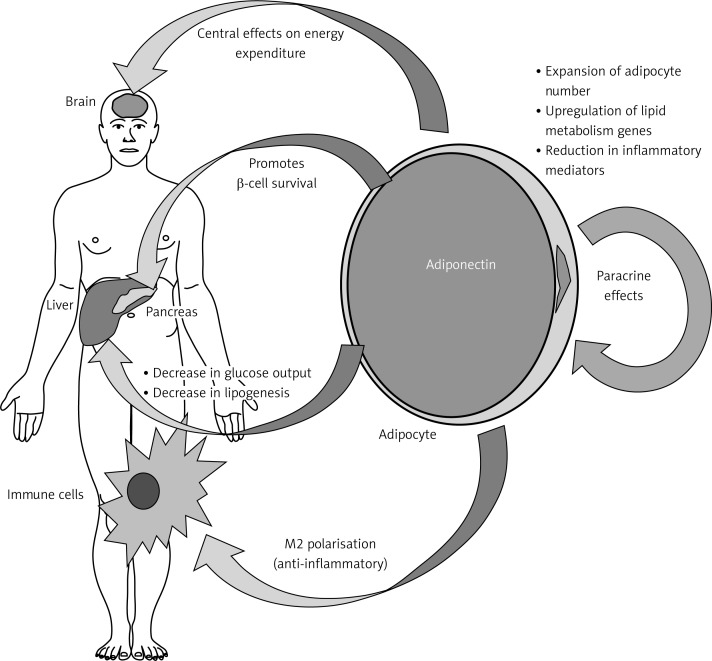

In healthy adults with adiponectin levels within the upper 20% range, it was noted that they have 2-fold reduced risk of myocardial infarction [112], and have 7-fold reduced risk of progression of coronary artery calcification [113]. Figure 2 illustrates the action of adiponectin on insulin sensitivity and peripheral tissues [114].

Figure 2.

Effects of adiponectin on insulin sensitivity and peripheral tissues [114]. Adiponectin regulates energy expenditure centrally, decreases lipogenesis and glucose output in the liver, improves the immune system via anti-inflammatory effects, and regulates lipid metabolism genes in adipocytes

Obesity and adiponectin

Adiponectin plays an important autocrine or paracrine role, having “local effects”, which influence adipose tissue functions by overexpressing the Adipoq gene which increases fat tissue mass via an increased number of adipocytes rather than size [114].

Different studies proved that serum level of adiponectin is reduced significantly with weight gain and obesity [115]. Studies in humans identified the role of visceral adipocytes in secreting adiponectin and other adipokines more than subcutaneous adipocytes, even though the decreased level of adiponectin in obesity is still unclear [106]. However, there is an assumption supposed that the increased serum level of inflammatory mediators such as IL-6 and TNF-α that are secreted from adipocytes are responsible for inhibiting and reducing the synthesis and secretion of adiponectin [106], and thus, the endothelial well-being and its cardioprotective action will also be suppressed [102].

Stępień et al. [116] compared adipokines and inflammatory markers in obese insulin-sensitive and insulin-resistant patients divided according to the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR). The study included 64 obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) outclinic adult patients, 39 women and 25 men, with or without hypertension (mean age: 55.9 ±11.8 years). The BAI strongly correlated with adiponectin in insulin-resistant patients (r = 0.479; p < 0.001).

Eglit et al. [117] conducted a cross-sectional study to evaluate the association between metabolic risk factors and obesity in a healthy population aged ≥ 20 years in Estonia. Adiponectin was negatively associated with obesity in both males and females, as it correlated positively with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c), and negatively with fasting blood glucose (FBG), total cholesterol (TC), and TG.

Snijder et al. [118] conducted a study to investigate the relationship between adiposity, adiponectin, and arterial stiffness. By cross-sectional design, 456 participants aged between 60 and 86 years were included from the Hoorn Study. Higher adiponectin was associated with decreased peripheral arterial stiffness, and also adiponectin was negatively associated with abdominal and total fat.

Dekker et al. [119] studied the impact of adiponectin in predicting CVDs and mortality in a population aged 50–75 years from the Hoorn Study. Adiponectin levels were divided into quartiles; the lowest quartile was associated with higher BMI, and the highest quartile was associated with lower BMI in significant trends in both men and women.

Jaleel et al. [120] compared the adiponectin level in normal weight and obese post-menopause women. The level of adiponectin was significantly reduced in obese subjects compared with normal weight ones. The study also showed that metabolic abnormalities are associated with obesity including lipid profile and leptin.

Complications associated with adiponectin

Hypoadiponectinemia (plasma level < 4.0 µg/ml) has been associated with increased levels of TG and FBG, decreased HDL-c, hypertension, and increased risk of metabolic syndrome [121]. The atherosclerosis risk was doubled by a low level of adiponectin [122]. Moreover, lower adiponectin has been associated with decreased low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particle size [123], and increased markers of systemic inflammation [105]. In addition, Dalamaga et al. [124] in a review linked it with many types of cancer based on epidemiological evidence. Table IV presents collected studies describing the complications of reduced levels of adiponectin and the main studied vascular and systemic diseases [125–136].

Table IV.

Complications associated with lower level of adiponectin

| Authors | Population | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Narayan et al. [125] | T2DM | Myocardial infarction |

| Kanhai et al. [126] | Meta-analysis | CHD and stroke |

| Kim et al. [127] | Meta-analysis | Hypertension |

| Blaslov et al. [128] | T1DM | Metabolic abnormalities |

| Chen et al. [35] | In metabolic syndrome patients, there was increased inflammation (CRP, IL-6), reduced activity of antioxidant enzyme (glutathione peroxidase), and increased oxidative stress markers (malondialdehyde) | |

| Kim et al. [129] | Non-diabetic adults | Impaired fasting glucose |

| Ho et al. [130] | Women’s Health Study | Peripheral artery disease |

| Li et al. [131] | Meta-analysis | T2DM |

| Snijder et al. [118] | Hoorn Study (Netherlands) | Peripheral arterial stiffness |

| Greif et al. [132] | CVD patients | Coronary atherosclerosis |

| Marso et al. [133] | Non-diabetic population | Plaque composition in coronary artery |

| Dekker et al. [119] | Hoorn Study (Netherlands) | Significant predictor of CVD mortality |

| Qasim et al. [134] | Healthy, non-diabetic subjects had positive CVD family history | Coronary artery calcification |

| Hanley et al. [135] | Non-diabetic Africans with positive family history | Negative association with adiposity and FBG level |

| Frystyk et al. [136] | Healthy elderly men | Coronary heart disease |

| Von Eynatten et al. [36] | In patients with CHD and heart failure patients, positive correlation with HDL-c and NT-proBNP (measure of left ventricular ejection fraction), negative correlation with TG |

Conclusions

Sustained inflammation is considered a strong risk factor for developing many diseases including CVDs, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and cancer. As a risk factor, obesity predisposes to a pro-inflammatory state via increased inflammatory mediators IL-6 and TNF-α, and reduced levels of adiponectin, which has totally anti-inflammatory function. According to Badawi et al. [137], TNF-α is overexpressed in the overweight state, while IL-6 is linked more to the obese state that influences the liver to synthesize and secrete CRP, which is a feature of systemic inflammation. This state is associated with reduced levels of adiponectin, which is important in improving insulin sensitivity, reducing metabolic abnormalities, and adjusting the energy expenditure. In addition, the inflammatory state followed by vascular and endothelial dysfunction is characterized by decreased nitric oxide and elevated reactive oxygen species leading to oxidative stress. Both statuses of oxidative stress and inflammation initiate atherosclerosis, hypertension, alteration of metabolic markers, and thus major adverse cardiovascular events.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses sincere thanks to the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, for the use of the library.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Romano M. Inflammation resolution: does the bone marrow have a say? Am J Hematol. 2008;83:435–6. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feuerstein GZ, Libby P, Mann DL. Inflammation – a new frontier in cardiac disease and therapeutics. In: Feuerstein GZ, Libby P, Mann DL, editors. Inflammation and cardiac diseases. Birkhäuser Basel; 2003. pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seki H, Tani Y, Arita M. Omega-3 PUFA derived anti-inflammatory lipid mediator resolvin E1. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2009;89:126–30. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassuk SS, Rifai N, Ridker PM. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein: clinical importance. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2004;29:439–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lafontan M. Fat cells: afferent and efferent messages define new approaches to treat obesity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;45:119–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stępień M, Stępień A, Wlazeł RN, Paradowski M, Banach M, Rysz J. Obesity indices and inflammatory markers in obese non-diabetic normo- and hypertensive patients: a comparative pilot study. Lipids Health Dis. 2014;13:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-13-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brichory FM, Misek DE, Yim AM, et al. An immune response manifested by the common occurrence of annexins I and II autoantibodies and high circulating levels of IL-6 in lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9824–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171320598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stenlof K, Wernstedt I, Fjallman T, Wallenius V, Wallenius K, Jansson JO. Interleukin-6 levels in the central nervous system are negatively correlated with fat mass in overweight/obese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4379–83. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papanicolau DA, Vgontzas AN. Interleukin-6: the endocrine cytokine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1331–2. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.3.6582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheller J, Chalaris A, Schmidt-Arras D, Rose-John S. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:878–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahmanian M, Kelishadi R, Qorbani M, et al. Dual burden of body weight among Iranian children and adolescents in 2003 and 2010: the CASPIAN-III study. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:96–103. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2014.40735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krzysztoszek J, Wierzejska E, Zielińska A. Obesity. An analysis of epidemiological and prognostic research. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11:24–33. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.37343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curat CA, Miranville A, Sengenès C, et al. From blood monocytes to adipose tissue-resident macrophages induction of diapedesis by human mature adipocytes. Diabetes. 2004;53:1285–92. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.5.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1509–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karastergiou K, Mohamed-Ali V. The autocrine and paracrine roles of adipokines. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;318:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fantuzzi G. Adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:911–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Straub RH, Hense HW, Andus J, Scholmerich J, Riegger AJ, Schunkert H. Hormone replacement therapy and interrelation between serum interleukin-6 and body mass index in postmenopause women: a population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1340–4. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.3.6355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fontana L, Eagon JC, Trujillo ME, Scherer PE, Klein S. Visceral fat adipokine secretion is associated with systemic inflammation in obese humans. Diabetes. 2007;56:1010–3. doi: 10.2337/db06-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halberg N, Wernstedt-Asterholm I, Scherer PE. The adipocyte as an endocrine cell. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008;37:753–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cinti S, Mitchell G, Barbatelli G, et al. Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:2347–55. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500294-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trayhurn P, Wood I. Adipokines: inflammation and the pleiotropic role of white adipose tissue. Br J Nutr. 2004;92:347–55. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang S, Liu Q, Wang J, Harnish DC. Suppression of interleukin-6-induced C-reactive protein expression by FXR agonists. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;379:476–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.12.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellulu MS, Khaza’ai H, Abed Y, Rahmat A, Ismail P, Ranneh Y. Role of fish oil in human health and possible mechanism to reduce the inflammation. Inflammopharmacology. 2015;23:79–89. doi: 10.1007/s10787-015-0228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rocha VZ, Libby P. Obesity, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:399–409. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.IllÁn-GÓmez F, GonzÁlvez-Ortega M, Orea-Soler I, et al. Obesity and inflammation: change in adiponectin, C-reactive protein, tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2012;22:950–5. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0643-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnardottir ES, Maislin G, Schwab RJ, et al. The interaction of obstructive sleep apnea and obesity on the inflammatory markers C-reactive protein and interleukin-6: the Icelandic Sleep Apnea Cohort. Sleep. 2012;35:921. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wannamethee SG, Whincup PH, Rumley A, Lowe G. Inter-relationships of interleukin-6, cardiovascular risk factors and the metabolic syndrome among older men. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1637–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warnberg J, Moreno LA, Mesana MI, Marcos A The AVENA group. Inflammatory mediators in overweight and obese Spanish adolescents. The AVENA Study. Int J Obes. 2004;28:S59–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sansone P, Bromberg J. Targeting the interleukin-6/Jak/Stat pathway in human malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1005–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.8907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Danesh J, Kaptoge S, Mann AG, et al. Long-term interleukin-6 levels and subsequent risk of coronary heart disease: two new prospective studies and a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e78. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adar SD, D’Souza J, Mendelsohn-Victor K, et al. Markers of inflammation and coagulation after long-term exposure to coarse particulate matter: a cross-sectional analysis from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:541–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1308069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarvottam K, Yadav RK. Adiponectin, interleukin-6, and endothelin-1 correlate with modifiable cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight/obese men. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:419–20. doi: 10.1089/acm.2013.0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen SJ, Yen CH, Huang YC, Lee BJ, Hsia S, Lin PT. Relationships between inflammation, adiponectin, and oxidative stress in metabolic syndrome. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Von Eynatten M, Hamann A, Twardella D, Nawroth P, Brenner H, Rothenbacher D. Relationship of adiponectin with markers of systemic inflammation, atherogenic dyslipidaemia, and heart failure in patients with coronary heart disease. Clin Chem. 2006;52:853–9. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.060509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernandez-Real JM, Monteserrat M, Richart C, et al. Circulating interleukin 6 levels, blood pressure, and insulin sensitivity in apparently healthy men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1154–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pradhan A, Manson J, Rifai N, Buring J, Ridker P. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;682:327–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Meir J, Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH. Plasma concentration of interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation. 2000;101:1767–72. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.15.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taniguchi K, Karin M. IL-6 and related cytokines as the critical lynchpins between inflammation and cancer. Semin Immunol. 2014;26:54–74. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou B, Liu J, Wang Z, Xi T. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6 and lung cancer risk: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ara T, DeClerck Y. Interleukin-6 in bone metastasis and cancer progression. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1223–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matura LA, Ventetuolo CE, Palevsky HI, et al. Interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha are associated with quality of life-related symptoms in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:370–5. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201410-463OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gluba A, Mikhailidis DP, Lip GY, Hannam S, Rysz J, Banach M. Metabolic syndrome and renal disease. Int J Cardiol. 2013;164:141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujishima S, Watanabe H, Kawaguchi M, et al. Involvement of IL-17F via the induction of IL-6 in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:499–505. doi: 10.1007/s00403-010-1033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gabay C. Interleukin-6 and chronic inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:S3. doi: 10.1186/ar1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di Cesare PE, Chang E, Preston CF, Liu CJ. Serum interleukin-6 as a marker of periprosthetic infection following total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1921–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.01803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, Ciragil P. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273–9. doi: 10.1155/MI.2005.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Musselman D, Miller A, Porter M, et al. Higher than normal plasma interleukin-6 concentrations in cancer patients with depression: preliminary findings. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1252–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wirtz DC, Heller KD, Miltner O, Zilkens KW, Wolff JM. Interleukin-6: a potential inflammatory marker after total joint replacement. Int Orthop. 2000;24:194–6. doi: 10.1007/s002640000136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elder JT, Sartor CI, Boman DK, Benrazavi S, Fisher GJ, Pittelkow MR. Interleukin-6 in psoriasis: expression and mitogenicity studies. Arch Dermatol Res. 1992;284:324–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00372034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Backes JM, Howard PA, Moriarty P. Role of C-reactive protein in cardiovascular disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:110–8. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ishii S, Karlamangla A, Bote M, et al. Gender, obesity and repeated elevation of C-reactive protein: data from the CARDIA Cohort. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003;107:499–511. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052939.59093.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Danesh J, Wheeler JG, Hirschfield GM, et al. C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1387–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kasapis C, Thompson PD. The effects of physical activity on serum C-reactive protein and inflammatory markers: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1563–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ledue TB, Rifai N. Preanalytic and analytic sources of variations in C-reactive protein measurement: implications for cardiovascular disease risk assessment. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1258–71. doi: 10.1373/49.8.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang CH, Li SH, Weisel RD, et al. C-reactive protein upregulates angiotensin type 1 receptors in vascular smooth muscle. Circulation. 2003;107:1783–90. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000061916.95736.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vadakayil AR, Dandekeri S, Kambil SM, Ali NM. Role of C-reactive protein as a marker of disease severity and cardiovascular risk in patients with psoriasis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:322–5. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.164483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takahashi H, Iinuma S, Honma M, Iizuka H. Increased serum C-reactive protein level in Japanese patients of psoriasis with cardio- and cerebrovascular disease. J Dermatol. 2014;41:981–5. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ma A, Pan X, Xing Y, Wu M, Wang Y, Ma C. Elevation of serum CXCL16 level correlates well with atherosclerotic ischemic stroke. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:47–52. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.39200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.KöşÜş N, KöşÜş A, Turhan N. Relation between abdominal subcutaneous fat tissue thickness and inflammatory markers during pregnancy. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:739–45. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2014.44865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kurtoglu E, Korkmaz H, Akturk E, Yılmaz M, Altas Y, Uckan A. Association of mitral annulus calcification with high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, which is a marker of inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:606207. doi: 10.1155/2012/606207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rajendran K, Devarajan N, Ganesan M, Ragunathan M. Obesity, inflammation and acute myocardial infarction – expression of leptin, IL-6 and high sensitivity-CRP in Chennai based population. Thromb J. 2012;10:13. doi: 10.1186/1477-9560-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Woodard G, Mehta V, Mackey R, et al. C-reactive protein is associated with aortic stiffness in a cohort of African American and white women transitioning through menopause. Menopause. 2011;18:1291–7. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31821f81c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee S, Kim IT, Park HB, et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein can predict major adverse cardiovascular events in Korean patients with type 2 diabetes. J Kor Med Sci. 2011;26:1322–7. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.10.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kalhan R, Tran BT, Colangelo LA, et al. Systemic inflammation in young adults is associated with abnormal lung function in middle age. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Den Hertog HM, van Rossum JA, van der Worp HB, et al. C-reactive protein in the very early phase of acute ischemic stroke: association with poor outcome and death. J Neurol. 2009;256:2003–8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5228-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Devaraj S, Yun J, Adamson G, Galvez J, Jialal I. C-reactive protein impairs the endothelial glycocalyx resulting in endothelial dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;84:479–84. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cirillo P, Sautin Y, Kanellis J, et al. Systemic inflammation, metabolic syndrome and progressive renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1384–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hubel C, Powers R, Snaedal S, et al. CRP is elevated 30 years after eclamptic pregnancy. Hypertension. 2008;51:1499–505. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.109934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Trichopoulos D, Psaltopoulou T, Orfanos P, Trichopoulou A, Boffetta P. Plasma C-reactive protein and risk of cancer: a prospective study from Greece. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:381–4. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Erlinger TP, Platz EA, Rifai N, Helzlsouer K. C-reactive protein and the risk of incident colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2004;291:585–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Seddon J, Gensler C, Milton R, Klein M, Rifai N. Association between C-reactive protein and age-related macular degeneration. JAMA. 2004;291:704–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.6.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Russell AI, Graham DC, Shepherd C, et al. Polymorphism at the C-reactive protein locus influences gene expression and predisposes to systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:137–47. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sesso HD, Buring JE, Rifai N, Blake GJ, Gaziano JM, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein and the risk of developing hypertension. JAMA. 2003;290:2945–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stuveling EM, Hillege HL, Bakker S, Gans R, de Jong PE, de Zeeuw D. C-reactive protein is associated with renal function abnormalities in a non-diabetic population. Kidney Int. 2003;63:654–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ridker PM. C-reactive protein: a simple test to help predict risk of heart attack and stroke. Circulation. 2003;108:e81–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093381.57779.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Han TS, Sattar N, Williams K, Gonzalez-Villalpando C, Lean M, Haffner S. Prospective study of C-reactive protein in relation to the development of diabetes and metabolic syndrome in the Mexico City Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2016–21. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.11.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mallya RK, De Beer FC, Berry H, Hamilton ED, Mace BE, Pepys MB. Correlation of clinical parameters of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis with serum concentration of C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. J Rheumatol. 1981;9:224–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brooks GC, Blaha MJ, Blumenthal RS. Relation of C-reactive protein to abdominal adiposity. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Choi J, Joseph L, Pilote L. Obesity and C-reactive protein in various populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2013;14:232–44. doi: 10.1111/obr.12003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Klisic A, Vasiljevic N, Simic T, Djukic T, Maksimovic M, Matic M. Association between C-reactive protein, anthropometric and lipid parameters among healthy normal weight and overweight postmenopause women in Montenegro. Lab Med. 2014;45:12–6. doi: 10.1309/lmi6i2rn7ampeuul. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dayal D, Jain H, Attri S, Bharti B, Bhalla A. Relationship of high sensitivity C-reactive protein levels to anthropometric and other metabolic parameters in Indian children with simple overweight and obesity. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:PC05. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8191.4685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kawamoto R, Kusunoki T, Abe M, Kohara K, Miki T. An association between body mass index and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein concentrations is influenced by age in community-dwelling persons. Ann Clin Biochem. 2013;50:457–64. doi: 10.1177/0004563212473445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ajani UA, Ford E, Mokdad A. Prevalence of high C-reactive protein in persons with serum lipid concentrations within recommended values. Clin Chem. 2004;50:1618–22. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.036004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Khand F, Shaikh SS, Ata MA, Shaikh SS. Evaluation of the effect of smoking on complete blood counts, serum C-reactive protein and magnesium levels in healthy adult male smokers. J Pak Med Assoc. 2015;65:59–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Libby P, Ridker P, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135–43. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Swiatkiewicz I, Kozinski M, Magielski P, et al. Usefulness of C-reactive protein as a marker of early post-infarct left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Inflamm Res. 2012;61:725–34. doi: 10.1007/s00011-012-0466-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Van Leeuwen WA, Lehto M, Karisola P, et al. Sleep restriction increases the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases by augmenting proinflammatory responses through IL-17 and CRP. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shivpuri S, Gallo L, Crouse J, Allison M. The association between chronic stress type and C-reactive protein in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA): does gender make a difference? J Behav Med. 2012;35:74–85. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9345-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kwon YS, Chi SY, Shin HJ, et al. Plasma C-reactive protein and endothelin-1 level in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pulmonary hypertension. J Kor Med Sci. 2010;25:1487–91. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.10.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Forman BM, Goode E, Chen J, et al. Identification of a nuclear receptor that is activated by farnesol metabolites. Cell. 1995;81:687–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rader DJ. Liver X receptor and farnesoid X receptor as therapeutic targets. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:S15–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Makishima M, Okamoto AY, Repa JJ, et al. Identification of a nuclear receptor for bile acids. Science. 1999;284:1362–5. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Evans MJ, Mahaney PE, Zhang S, et al. A synthetic farnesoid X receptor agonist protects against diet-induced dyslipidemia. Circulation. 2007;116:II–106. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Li J, Wilson A, Kuruba R, et al. FXR-mediated regulation of eNOS expression in vascular endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:169–77. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Blaschke F, Takata Y, Caglayan E, et al. A nuclear receptor corepressor-dependent pathway mediates suppression of cytokine-induced C-reactive protein gene expression by liver X receptor. Circ Res. 2006;99:e88–99. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000252878.34269.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Matsuda M, Shimomura I, Sata M, et al. Role of adiponectin in preventing vascular stenosis. The missing link of adipovascular axis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37487–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bastard JP, Maachi M, Lagathu C, et al. Recent advances in the relationship between obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006;17:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Goldstein BJ, Scalia R. Adiponectin: a novel adipokine linking adipocytes and vascular function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2563–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Alvarez A, Brodsky JB, Lemmens H, Morton JM. Morbid obesity: peri-operative management. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pischon T, Rimm E. Adiponectin: a promising marker for cardiovascular disease. Clin Chem. 2006;52:797–9. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.067819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Oh D, Giaraldi T, Henry R. Adiponectin in health and disease. Diab Obes Metab. 2007;9:282–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2006.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ouchi N, Kihara S, Funahashi T, et al. Reciprocal association of C-reactive protein with adiponectin in blood stream and adipose tissue. Circulation. 2003;107:671–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055188.83694.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Matsuzawa Y. The metabolic syndrome and adipocytokines. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2917–21. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Szmitko PE, Teoh H, Stewart DJ, Verma S. Adiponectin and cardiovascular disease: state of the art? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1655–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01072.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nakamura Y, Shimada K, Fukuda D, et al. Implications of plasma concentrations of adiponectin in patients with coronary artery disease. Heart. 2004;90:528–33. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.011114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ouedraogo R, Wu X, Xu SQ, et al. Adiponectin suppression of highglucose-induced reactive oxygen species in vascular endothelial cells: evidence for involvement of a cAMP signaling pathway. Diabetes. 2006;55:1840–6. doi: 10.2337/db05-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Harmancey R, Wilson C, Taegtmeyer H. Adaptation and maladaptation of the heart in obesity. Hypertension. 2008;52:181–7. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.110031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Park S, Kim DS, Kwon DY, Yang HJ. Long-term central infusion of adiponectin improves energy and glucose homeostasis by decreasing fat storage and suppressing hepatic gluconeogenesis without changing food intake. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23:687–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pischon T, Girman CJ, Hotamisligil GS, Rifai N, Hu FB, Rimm EB. Plasma adiponectin levels and risk of myocardial infarction in men. JAMA. 2004;291:1730–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Maahs DM, Ogden LG, Kinney GL, et al. Low plasma adiponectin levels predict progression of coronary artery calcification. Circulation. 2005;111:747–53. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155251.03724.A5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Turer A, Scherer P. Adiponectin: mechanistic insights and clinical implications. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2319–26. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2598-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ricci R, Bevilacqua F. The potential role of leptin and adiponectin in obesity: a comparative review. Vet J. 2012;191:292–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Stępień M, Stępień A, Wlazeł RN, et al. Predictors of insulin resistance in patients with obesity a pilot study. Angiology. 2014;65:22–30. doi: 10.1177/0003319712468291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Eglit T, Ringmets I, Lember M. Obesity, high-molecular-weight (HMW) adiponectin, and metabolic risk factors: prevalence and gender-specific associations in Estonia. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Snijder MB, Flyvbjerg A, Stehouwer C, et al. Relationship of adiposity with arterial stiffness as mediated by adiponectin in older men and women: the Hoorn Study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160:387–95. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Dekker JM, Funahashi T, Nijpels G, et al. Prognostic value of adiponectin for cardiovascular disease and mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1489–96. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jaleel F, Jaleel A, Rahman M, Alam E. Comparison of adiponectin, leptin and blood lipid levels in normal and obese postmenopause women. J Pak Med Assoc. 2006;56:391–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ryo M, Nakamura T, Kihara S, et al. Adiponectin as a biomarker of the metabolic syndrome. Circ J. 2004;68:975–81. doi: 10.1253/circj.68.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tziakas DN, Chalikias GK, Kaski JC. Epidemiology of the diabetic heart. Coron Artery Dis. 2005;16:S3–10. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200511001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Baratta R, Amato S, Degano C, et al. Adiponectin relationship with lipid metabolism is independent of body fat mass: evidence from both cross-sectional and intervention studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2665–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dalamaga M, Diakopoulos KN, Mantzoros CS. The role of adiponectin in cancer: a review of current evidence. Endocr Rev. 2012;33:547–94. doi: 10.1210/er.2011-1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Narayan A, Kulkarni S, Kothari R, Deepak T, Kempegowda P. Association between plasma adiponectin and risk of myocardial infarction in Asian Indian patient with diabetes. Br J Med Pract. 2014;7:e729. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kanhai DA, Kranendonk ME, Uiterwaal C, Graaf Y, Kappelle L, Visseren F. Adiponectin and incident coronary heart disease and stroke. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Obes Rev. 2013;14:555–67. doi: 10.1111/obr.12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kim DH, Kim C, Ding E, Townsend M, Lipsitz L. Adiponectin levels and the risk of hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2013;62:27–32. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Blaslov K, Bulum T, Zibar K, Duvnjak L. Relationship between adiponectin level, insulin sensitivity, and metabolic syndrome in type 1 diabetic patients. Int J Endocrinol. 2013;2013:535906. doi: 10.1155/2013/535906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kim SY, Lee SJ, Park H, et al. Adiponectin is associated with impaired fasting glucose in the non-diabetic population. Epidemiol Health. 2011;33:e2011007. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2011007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ho DY, Cook NR, Britton KA, et al. High-molecular-weight and total adiponectin levels and incident symptomatic peripheral artery disease in women. Circulation. 2011;124:2303–11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.045187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Li S, Shin HJ, Ding EL, van Dam R. Adiponectin levels and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;302:179–88. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Greif M, Becker A, von Ziegler F, et al. Pericardial adipose tissue determined by dual source CT is a risk factor for coronary atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:781–6. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.180653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Marso SP, Mehta SK, Frutkin A, House JA, McCarary JR, Kullarni KR. Low adiponectin levels are associated with atherogenic dyslipidemia and lipid-rich plaque in nondiabetic coronary arteries. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:989–94. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Qasim A, Mehta NN, Tadesse MG, et al. Adipokines, insulin resistance and coronary artery calcification. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:231–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hanley AG, Bowden D, Wagenknecht LE, et al. Associations of adiponectin with body fat distribution and insulin sensitivity in nondiabetic Hispanics and African-Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2665–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Frystyk J, Berne C, Berglund L, Jensevik K, Flyvbjerg A, Zethelius B. Serum adiponectin is a predictor of coronary heart disease: a population-based 10-year follow-up study in elderly men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:571–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Badawi A, Klip A, Haddad P, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and inflammation: prospects for biomarkers of risk and nutritional intervention. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2010;3:173–86. doi: 10.2147/dmsott.s9089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]