The Varied Roles of Notch in Cancer (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2018 May 3.

Abstract

Notch receptors influence cellular behavior by participating in a seemingly simple signaling pathway, but outcomes produced by Notch signaling are remarkably varied depending on signal dose and cell context. Here, after briefly reviewing new insights into physiologic mechanisms of Notch signaling in healthy tissues and defects in Notch signaling that contribute to congenital disorders and viral infection, we discuss the varied roles of Notch in cancer, focusing on cell autonomous activities that may be either oncogenic or tumor suppressive.

Keywords: Notch, cellular transformation, cancer hallmarks, oncogene, tumor suppressor

INTRODUCTION

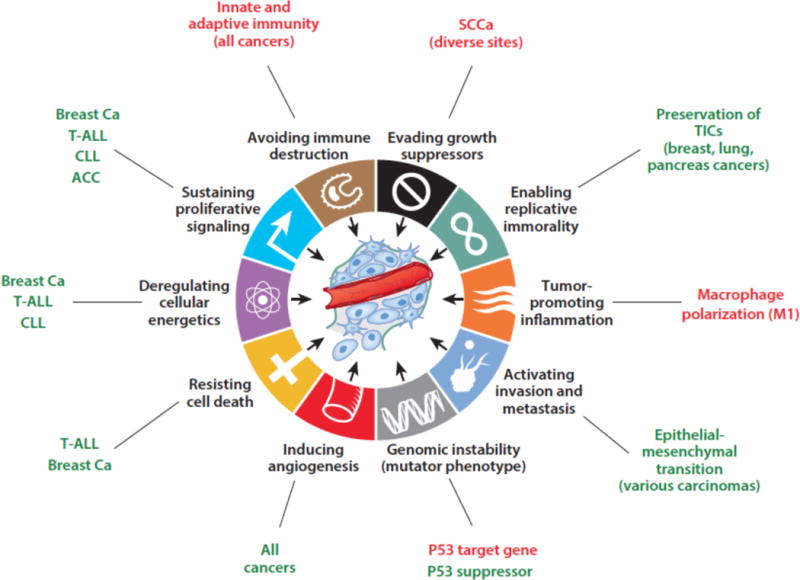

Notch receptors belong to a highly conserved signaling pathway that relies on cell-cell contacts to induce a response to environmental cues in multicellular animals. Most Notch-mediated cellular outcomes are determined by a signal transduction mechanism in which regulated proteolysis creates Notch transcription complexes controlling the expression of responsive genes. Biochemical, cell biological, and structural studies from many laboratories have brought the details of the Notch signaling mechanism into focus over the past two decades. More recently, unbiased genome-scale sequencing studies identified mutations in Notch genes in a broad spectrum of cancers. Remarkably, the positions, identities, and effects of these mutations are cancer-specific and reflect varied roles for Notch in different cancer contexts. Indeed, functional studies implicate Notch signaling in essentially all of the hallmarks of cancer (Figure 1), and clearly point to roles that range from oncogenic to tumor suppressive, depending on cancer type.

Figure 1.

Cancer hallmarks proposed to be influenced by Notch signaling. Positive (oncogenic) effects are shown in green, tumor suppressive effects are in red. T-ALL, T acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, ACC, adenoid cystic carcinoma; SCCa, squamous cell carcinoma; breast Ca, breast carcinoma; TICs, tumor initiating cells.

Here, we will briefly review the key steps and modulators of normal Notch signal transduction, and then turn to the varied roles of Notch in cancer. In doing so, we will not attempt to be encyclopedic, but rather will highlight particularly well characterized examples, recent studies, and important areas of continuing uncertainty or controversy.

STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF NOTCH RECEPTORS AND LIGANDS

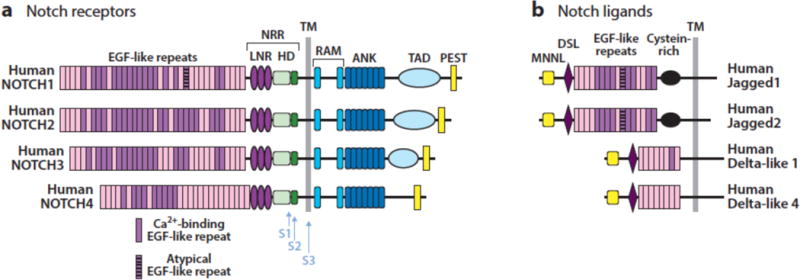

Notch receptors are single pass transmembrane proteins composed of a series of distinct protein modules. The extracellular region of Notch receptors consist of a series of N-terminal EGF repeats followed by a juxtamembrane negative regulatory region (NRR) comprised of 3 Lin12/Notch repeats (LNRs) and a heterodimerization domain. The intracellular region of Notch receptors contain a protein-binding RAM region, seven ankyrin repeat domains, a transcriptional activation domain, and a C-terminal degron domain rich in the amino acids proline, glutamate, serine, and threonine (PEST) (Figure 2A). Mammals express four different Notch receptors, Notch1-4, each encoded by a different gene. These receptors contain from 29-36 EGF repeats and also demonstrate structural divergence in their C-terminal intracellular regions. Notch1 and Notch2 are expressed widely in many tissues throughout development and in adult mammals. By contrast, Notch3 is most abundant in vascular smooth muscle and pericytes, and Notch4 most highly expressed in endothelium. In line with these expression patterns, Notch1 (1) and Notch2 (2) knockouts produce embryonic lethality in mice associated with developmental defects in many organs, whereas Notch3 (3) and Notch4 (1) knockout mice are viable have relatively subtle phenotypes that are confined to blood vessels.

Figure 2.

Structure of human Notch receptors and ligands. NRR, negative regulatory region; LNR, Lin-12/Notch repeat; HD, heterodimerization domain; TM, transmembrane domain; ANK, ankyrin repeat domain; TAD, transcriptional activation domain; MNNL, N-terminal domain of Notch ligands; DSL, Delta-Serrate-Lag2 domain.

There are four functional Notch ligands in mammals (Figure 2B), all of which also are single-pass transmembrane proteins: Dll1 and Dll4, which are members of the Delta family of ligands; and Jag1 and Jag2, which are members of the Serrate family of ligands. There also is a Dll3 gene, which cannot activate Notch receptors in trans and appears to encode a decoy receptor (4; 5), as phenotypes observed in Dll3 deficient mice are consistent with Notch gain-of-function (6). Expression patterns of ligands are less well defined than those of receptors, but knockout mice and some congenital human disorders (Table 1) have revealed specific functions and preferred cognate ligand-receptor pairs. For example, knockout mice showed that expression of Dll4 on thymic stromal cells (7) and Notch1 on T cell progenitors (8) is needed to induce T cell development, in line with biochemical studies showing that Notch1 has a higher affinity for Dll4 than Dll1 (9). Similarly, Adams-Oliver syndrome, a rare autosomal dominant disorder associated with terminal limb defects, may be caused by loss-of-function mutations in Notch1 and Dll4 as well as RBPJ. By contrast, Dll1 (10) and Notch2 (11) knockout mice have similar defects in splenic marginal B cell development, while human Alagille syndrome, a developmental disorder that principally affects the liver, biliary tree, and heart, is caused by germline loss-of-function mutations in Jag1 or Notch2. As will be discussed, developmental relationships between specific receptors are reflected in the patterns of Notch gene mutations that are seen in certain cancers, and have implications for the rational development of effective targeted therapies.

TABLE 1.

CONGENITAL DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH MUTATIONS IN NOTCH PATHWAY GENES

| Disorder | Affected Genes | Affected Tissues | Effect of Mutations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alagille Syndrome | Jag1, Notch2 | Liver, heart, eye, bone | Loss of function | (192; 193) |

| CADASIL | Notch3 | Arteries, particular in the CNS | Toxic gain of function versus loss of function | (194) |

| Bicuspid Aortic Valve | Notch1 | Heart (bicuspid valve, valve calcification) | Loss of function | (195) |

| Hajdu-Cheney Syndrome | Notch2 | Bone (excessive bone resorption) | Conditional gain of function (loss of Notch2 PEST domain) | (196) |

| Adams-Oliver Syndrome | RBPJ, Notch1, Dll4 | Aplasia cutis of the scalp, terminal limb defects | Loss of function | (197–199) |

| Spondylocostal Dysostosis | Dll3 | Hemivertebrae, rib fusions, rib deletions | Loss of function, may lead to increased Notch signaling | (200) |

| Dowling-Degos disease | Pofut1, Poglut1 | Skin, abnormal pigmentation | Loss of function | (201; 202) |

MECHANISM OF NOTCH SIGNALING

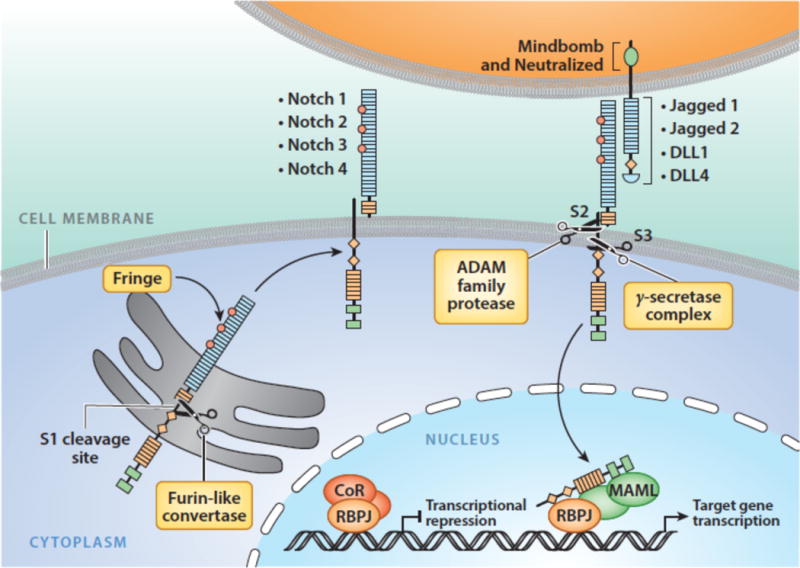

Notch receptor maturation and activation is dependent upon a series of cleavages carried out by 3 different proteases (Figure 3). During trafficking to the cell surface, Notch receptors undergo cleavage by a furin-like protease at site S1 in an unstructured region of the heterodimerization domain (12), creating a non-covalently associated heterodimer composed of a Notch extracellular subunit and a transmembrane Notch subunit (13). The resulting mature receptor is held in the “off-state” by the juxtamembrane Notch negative regulatory region (NRR) (14), which consists of three Lin12/Notch repeats (LNRs) and the heterodimerization domain. Binding of Notch to a ligand expressed on a neighboring cell releases the autoinhibition imposed by the NRR and allows ADAM metalloproteases to cleave at site S2, which lies immediately external to the transmembrane domain (15; 16). This second, rate-limiting cleavage relies not only on ligand binding to the receptor, but also on the delivery of mechanical force to the receptor by the signal-sending cell (17). Ubiquitination of the ligand cytoplasmic tail by either of two E3 ligases, Neuralized (18) or Mind Bomb (19), is required for ligand-mediated Notch receptor activation in vivo, leading to the proposal that ligand endocytosis serves as the origin of the supplied force, but this model has yet to be rigorously tested. Both ADAM10 and ADAM17 have been implicated in S2 cleavage; ADAM10 appears to be the most important physiologic Notch activator (20; 21), while ADAM17 may be particularly important for ligand-independent pathophysiologic Notch signaling (22). S2 cleavage creates a short-lived transmembrane form of Notch that is rapidly cleaved within its transmembrane segment by gamma-secretase (23; 24), releasing the Notch intracellular domain (NICD). Once freed from the membrane, NICD translocates to the nucleus and forms a Notch transcription complex (NTC) consisting of NICD, the DNA binding factor RBPJ (also known as CSL), and coactivators of the Mastermind-like (MAML) family (25). Binding of the NTC to Notch regulatory elements (NREs) is followed by recruitment of transcriptional coregulators that initiate transcription of Notch target genes. Proteins implicated in this step include the histone acetyl transferase p300 (26), histone demethylases such as KDM1A (also known as LSD1) (27; 28), and components of the mediator complex (29), which initiate transcription of Notch target genes. Transcriptional activation correlates with rapid, stereotypical increases in the deposition of chromatin marks on nucleosomes adjacent to sites of NTC binding, including H3K4 trimethylation and H2B ubiquitinylation in the promoters of Notch regulated genes (30), and H3K27 (31) and H3K56 acetylation (32) in Notch regulated enhancer elements.

Figure 3.

Notch signaling. See text for details.

In mammalian cells, evidence to date suggests that the majority of functional NREs reside in enhancer elements rather than promoters (31; 33), emphasizing the importance of whole genome analyses for understanding Notch regulation of gene expression. Dwell time of NTCs on NREs has not been measured directly but is proposed to be short due to evidence pointing to transcription-coupled degradation of NICD. In one plausible model, phosphorylation of the C-terminal PEST domain by the mediator components cyclinC/Cdk8 (29; 34) leads to recognition and ubiquitinylation of NICD by E3 ligase complexes, such as those containing the F-box protein Fbxw7 (35; 36), which stimulates proteasomal degradation of NICD.

Regulation of NICD function also likely involves inputs from many other signaling pathways, as NICD is subject to a host of post-translational modifications at other sites, including phosphorylation at sites outside of the PEST domain (37–40), arginine methylation (41) and hydroxylation (42), and lysine acetylation (43). Precisely how such modifications influence the assembly, function and turnover of NTCs is poorly understood, but early work in this area suggests that their impact on function is complex. For example, the arginine methyltransferase Prmt4 (also known as Carm1) was recently reported to bind and methylate the C-terminal transcriptional activation domain of Notch1 (41). Mutation of conserved arginines that are subject to methylation by Prmt4 stabilizes NICD1, but also creates phenotypes in frogs and fish that are consistent with Notch loss-of-function rather than gain-of-function. Similarly, deletion of the Notch1 transcriptional activation domain in mice stabilizes NICD1 while producing a loss-of-function phenotype that manifests as a defect in fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells (44), providing indirect evidence for the idea that defects that interfere with the intrinsic transcriptional activation activity of NICD also affect NICD turnover.

Notch signals rely on stoichiometric release of active molecules in response to bound ligands. This unusual signaling mechanism, which does not depend on any enzymatic amplification steps, probably serves to enable precise regulation of Notch signal strength under normal circumstances. In line with this idea, Notch phenotypes in invertebrate model organisms are typically sensitive to changes in gene dosage, and RBPJ, Notch1, Notch2, Dll4, and Jag1 haploinsufficiency are all associated with human developmental abnormalities (Table 1).

The numerous varieties of post-translational modifications that Notch receptors undergo also likely reflect the need for very precise “tuning” of Notch signaling tone. In flies, optimal delivery of Notch receptors to the cell surface depends on O-linked fucoslyation of the ligand-binding EGF-like repeats in the extracellular domain by Pofut1 (45), which is proposed to act as a chaperone for Notch receptors, but this role for Pofut1 is less certain in mammalian cells (46). What is consistent across studies in cells and tissues from various species is that the addition of fucose residues to consensus acceptor sites by Pofut1 increases the capacity of Notch proteins to bind ligands (46). The subsequent addition of N-acetylglucosamine to O-linked fucose residues by Fringe family enzymes further enhances responsiveness to Delta family ligands (47). The recent X-ray structure of a Notch1-Dll4 complex shows that the ligand contacts the fucose moiety on T466 of the twelfth EGF repeat directly (48), providing a structural rationale for the observed ability of Pofut1 and Fringe enzymes to increase the affinity of Delta-like ligand for Notch receptors. The O-glucosyl transferase Poglut1 (known as Rumi in Drosophila) similarly influences Notch receptor activity (49; 50), though the mechanistic basis for Notch loss-of-function in the absence of Poglut1 is more poorly understood. As noted above, NICD is subject to host of posttranslational modifications, all of which are proposed to modulate NICD stability and activity. It also seems highly likely that expression of Notch receptors themselves is under very tight control in normal cells; however, at present relatively little is known about the regulation of the transcription of Notch genes in various cellular contexts. For example, upregulation of Notch1 is critical for early stages of T cell development, whereas downregulation of Notch1 past the β-selection checkpoint at the DN3 stage of T cell development may be important in preventing sustain Notch signaling, which is potently transforming in this lineage. The latter event may occur via signals transduced by the pre-T cell receptor that upregulate Id3 and inhibition of Tcf3 (also known as E2A), which has been proposed to be an important positive regulator of Notch1 expression at the DN3 stage of thymocyte development (51).

An additional layer of control of Notch target gene expression involves i) inhibitory feedback loops and ii) the ability of RBPJ to bind to transcriptional repressors as well as NICD. Nrarp is a Notch target gene in vertebrates encoding a small ankyrin repeat protein that acts as a negative feedback regulator of signaling (52), and members of the Hairy/enhancer of split (Hes) family are proposed to have broad roles in negative regulation of both themselves and other Notch target genes (53). In the absence of NICD, RBPJ interacts with a number of transcription repressors, such as complexes containing Spen (also known as Sharp and Mint) (54; 55) that recruit histone deacetylases and the H3K4me3 demethylase KDM5A (56), providing RBPJ with a switch-like function that may serve to tighten the regulation of Notch target genes. It is unknown whether transcriptional activation and repression complexes are assembled on or off of chromatin, and the factors and variables that i) determine the fraction of RBPJ molecules that is found in either repression or activation complexes and ii) the relative occupancy of NREs by various RBPJ complexes in cells remain to be defined.

When considering the balance between RBPJ repressor and activation complexes, it is interesting to note that certain transforming viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus and adenoviruses, encode distinct proteins that activate or repress transcription by interacting with RBPJ, suggest that the ability to “toggle” between RBPJ-mediated transcriptional activation and repression has a critical role in the life cycle of these viruses (Table 2). As will be discussed, in certain tumors this delicate balance is disrupted by strong gain-of-function mutations in Notch receptors, leading to high levels of sustained Notch activation, overexpression of Notch target genes, and cellular transformation.

TABLE 2.

VIRAL PROTEINS TARGETING COMPONENTS OF THE NOTCH TRANSCRIPTION COMPLEX (NTC)

| Protein | Virus | NTC component targeted | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBNA2 | EBV | RBPJ | Transactivation; required for B cell transformation | (203) |

| EBNA3A, EBNA3B, EBNA3C | EBV | RBPJ | Interference with RBPJ function; required for B cell transformation | (204) |

| E1A S13 | Adenovirus | RBPJ | Transactivation; required for transforming activity | (205) |

| E1A S12 | Adenovirus | RBPJ | Transcriptional repression; required for transforming activity | (205) |

| E6 | β-HPV | MAML1 | Interference with MAML1 and NTC function | (137) |

| RTA | HHV8 | RBPJ | Transactivation; transition from latent to lytic infection | (206) |

In addition to the canonical Notch signaling pathway shown in Figure 3, in some experimental systems it has been noted that deletion of RBPJ fails to precisely mimic the effects of pan-Notch receptor inhibition, for example through blockade with gamma-secretase inhibitors or deletion of multiple Notch genes (57). This has been taken as evidence of alternative non-canonical Notch signaling mechanisms; however, the details of how non-canonical signaling occurs and its contribution to pathophysiologic states such as cancer remains obscure.

Pleiotropic Effects of Notch in Normal and Transformed Cells

Despite the relative simplicity of the core Notch signaling pathway, outcomes produced by Notch during development and in adult tissues are remarkably varied. The simplest explanation for this pleiotropy is for Notch to activate sets of target genes that also vary across different epigenetic contexts. While systematic identification of direct Notch target genes has thus far been confined to a relatively small set of cell types, findings to date are consistent with this idea. We have compared genes that rapidly respond to Notch activation in three human cell types in which Notch1 has an oncogenic role, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), mantle cell lymphoma (a B-cell tumor) and triple negative breast cancer (58). In each cell type, Notch1 activation stimulates the expression of >100 genes, but only 5 of these are common across all three cell types. Notably, one of the common genes is Myc, which is an important driver of Notch-mediated transformation in several tumors types (discussed later). Only three of these 5 genes (Nrarp, Hey1, and Notch3) overlap with a different set of likely direct Notch1 target genes in murine C2C12 myoblasts (33). Others studying the effects of acute Notch activation in several different Drosophila cell types also have observed lineage-dependent variation in downstream transcriptional responses (59). The variation of transcriptional outputs in response to Notch as a function of cell type highlights how methods such as gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) are likely to be misleading when trying to determine Notch activity unless one uses a signature specific for the context of interest.

A corollary to this reasoning is that the transcriptional output of Notch activation in any given context is likely dictated by pre-existing chromatin states set by upstream “pioneers”, transcription factors capable of binding to and opening up repressed chromatin, as well as factors that regulate chromatin looping, which is critical for enhancer function. This makes it tempting to relegate Notch to the category of “settlers”, transcription factors that alight on and work through regulatory elements made accessible by other factors. While this view may hold in cells that are arrested at particular stages of development (e.g., cancer cell lines), it seems likely that Notch must have a more complex and dynamic relationship with pioneer factors during the normal development and differentiation of particular cell lineages. For example, Notch1 is essential to specificy adult-type hematopoietic stem cells in the dorsal aorto-gonadal-mesonephros (AGM) region, and lineage-tracing experiments place Notch upstream of pioneer factors such as Runx1, Myb, and Gata2 in this process (60). Perhaps Notch acts in combination with certain pioneer factors at lineage decision branch points to turn on downstream pioneer factors, which then modify chromatin landscapes so as to enable Notch to drive a different set of transcriptional outputs during subsequent downstream cell fate decisions.

The outcome of Notch activation also is influenced by signal strength, which determines the number of NTCs that are available to bind to any particular NRE. NREs vary in sequence and affinity for RBPJ and come in two forms, monomeric sites and highly conserved “sequence paired sites” consisting of head to head RBPJ binding sites separated by 15-17 base pair spacers (61). Sequence paired sites bind NTCs cooperatively and may be preferentially associated with genes that respond to Notch activation with rapid kinetics (62). Thus, short, relatively weak Notch signals may only activate a subset of target genes, whereas stronger, longer duration signals (as in tumor cells with constitutively active Notch) may lead to activation of larger sets of genes, perhaps even “capturing” genes that are not subject to Notch regulation at physiologic doses.

In addition to the core canonical Notch signaling pathway described above, diverse lines of investigation have raised the possibility of non-canonical Notch signaling mechanisms. In mammalian cells this has mainly focused on possible interactions involving NICD with downstream effectors other than RBPJ. For example, evidence has been generated suggesting that NICD physically interacts with β-catenin (63), Smad proteins (64), and HIF-1α (65), thereby providing a means for direct crosstalk between Notch and the Wnt, TGFβ, and hypoxia-dependent signaling pathways. However, it is noteworthy that most Notch-dependent cancer phenotypes described to date can be perturbed by interfering with the expression or function of RBPJ or MAMLs, that is, other components of the canonical Notch signaling pathway. Thus, the importance of non-canonical Notch signaling in cancer remains to be determined.

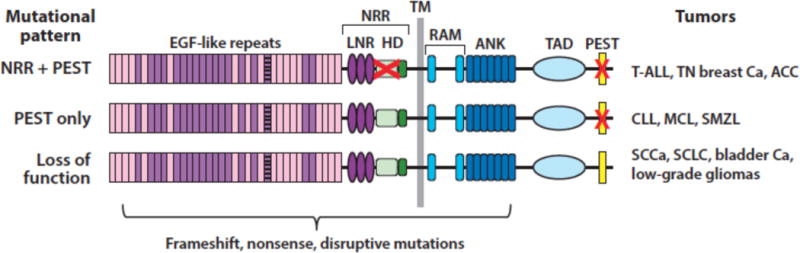

MUTATIONAL PATTERNS POINT TO DIVERGENT ROLES FOR NOTCH IN DIFFERENT CANCERS

Sequencing of cancer genomes has revealed three distinct patterns of Notch gene mutation in various human tumors (Figure 4), each reflecting context-specific selective pressure for altered Notch function. The prototype (pattern 1) was first discovered through analysis of a rare (7;9) chromosomal translocation in T-ALL that produces a chimeric gene consisting of the 3′ end of Notch1 fused to enhancer elements of the TCRβ gene (66). Such rearrangements completely remove the NRR coding sequence and lead to expression of truncated Notch1 polypeptides that undergo ligand-independent proteolysis and conversion to NICD1. We subsequently identified much more frequent point substitutions and in-frame insertion/deletion mutations in T-ALL that also disrupt the structure of the Notch1 NRR (67), again resulting in ligand-independent Notch1 proteolysis and activation. By contrast, murine T-ALLs arising in many different genetic backgrounds have RAG-mediated 5′ deletions in Notch1 that remove the proximal Notch1 promoter, leading to expression of truncated transcripts similar to those seen in human T-ALLs with the t(7;9) (68). A limited number of other tumors also have point substitutions or 5′ Notch1 deletions that disrupt the NRR (Table 3), including subsets of triple negative breast cancer (58; 69), adenoid cystic carcinoma (70–72)(and unpublished data, JCA), and tumors derived from pericytes or smooth muscle (73). T-ALL (67), triple negative breast cancers (74), and adenoid cystic carcinoma (70; 72) also are sometimes associated with nonsense and frameshift mutations that result in loss of the C-terminal PEST degron domain (Figure 4). These two types of mutations are sometimes found in cis in the same allele, a configuration that leads to high levels of NICD1 (67). Thus, in some tumor types, there is ongoing selective pressure for accumulation of ever-higher levels of constitutive Notch activation.

Figure 4.

Patterns of Notch mutations in various cancers. The red X in the negative regulatory region (NRR) corresponds to point substitutions, in-frame indels, and rare deletions that remove the 5′ coding exons of Notch receptors. The red X in the PEST domain corresponds to nonsense or frameshift mutations that lead to loss of the PEST domain.

TABLE 3.

NOTCH GENE MUTATIONS IN CANCER

| Tumor | Affected Gene(s) and Frequency | References/Tumor Numbers |

|---|---|---|

| GOF, NRR or PEST Mutations | ||

| T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Notch1 (50% to 60%)Notch3 (rare) | (67) (n=96); (207) (n=1) |

| Early T cell progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Notch1 (uncertain in pediatric cases, 15% to 35% of adult cases) | (208) (n=29); (209) (n=12); (210) (n=58) |

| Breast carcinoma | Notch1 (5% to 10% of triple negative breast cancer)Notch2 (5% of triple negative breast cancer) | (69) (n=38); (58) (n=66) |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | Notch1 (5% to 15%) | (72) (n=24); (71) (n=60) |

| Glomus tumor | Notch2 (52%)Notch3 (9%)Notch1 (rare) | (73) (n=33) |

| GOF, PEST Mutations Only | ||

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma | Notch1 (10%-15%) | (75) (n=43); (77) (n=363); (211) (n=452) |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | Notch1 (5% to 10%)Notch2 (5%) | (80) (n=126); (212) (n=172) |

| Marginal zone B cell lymphoma | Notch2 (5% to 25%) | (78) (n=69); (79) (n=99); (213) (n=39) |

| Diffuse large B cell lymphoma | Notch2 (20%)*Notch1 (5%) | (83) (n=46); (82) (n=49) |

| Splenic diffuse red pulp small B cell lymphoma | Notch1 (11%) | (214) (n=19) |

| Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma | Notch1 (5% to 10%) | (215) (n=21); (84) (n=32) |

| LOF Mutations | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma – skin | Notch1, Notch2 (70% to 80%) | (89) (n=26); (216) (n=132); (217) (n=8) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma – head and neck | Notch1 (10%)Notch2 (<5%)Notch3 (<5%) | TCGA, provisional data set (n=530) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma – lung | Notch1 (5-10%)Notch2 (<5%)Notch3 (<5%) | TCGA, provisional data set (n=504); (93) (n=178) |

| Small cell lung carcinoma | Notch1, Notch2, Notch3 (25% of tumors affected) | (94) (n=110) |

| Urothelial carcinoma | Notch1 (50%) | (95) (n=72) |

| Esophageal carcinoma | Notch1 (10%) | (218) (n=88) |

| Low-grade glioma | Notch1 (31% of IDH mutated tumors) | (96) (n=223) |

The second pattern is defined by tumors in which frameshift, nonsense, or alternative splicing mutations affecting the Notch PEST domain are observed in the absence of mutations disrupting the Notch NRR (Figure 4). This pattern is mainly confined to B cell tumors such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (75–77), splenic marginal zone lymphoma (78; 79), and mantle cell lymphoma (80), as well as occasional diffuse large B cell lymphomas (81–83) and peripheral T cell lymphomas, such as adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (84). Based on the logic of Notch receptor activation and regulation, several conclusions can be drawn regarding Notch signaling in tumors exhibiting “PEST only” mutations: 1) there is no selective pressure for constitutive (i.e., ligand-independent) Notch activation, presumably because it is disfavored; 2) the dose of Notch that provides a selective advantage is likely to be lower than in tumors with mutation pattern 1; and 3) the selective pressure for increased Notch activation is likely to be confined to one or more microenvironments where tumor cells engage Notch ligands expressed on stromal cells. In line with the latter idea, in situ staining of lymph nodes involved by Notch1 PEST domain-mutated chronic lymphocytic leukemia has shown that levels of activated Notch1 are substantially higher within lymph nodes than immediately adjacent extranodal soft tissues (85). An alternative explanation that has been proposed for Notch activation in tumor cells bearing only PEST deletions is that activation depends on ligands expressed in the tumor cells (see reference (86), for example). Though not formally disproven, such a mechanism is at odds with evidence from developmental and cell culture systems that co-expression of ligand and receptor in the same cell leads to Notch inhibition rather than Notch activation, a phenomenon referred to as cis inhibition (87; 88).

The third mutational pattern is marked by disruptive nonsense, frameshift, or point substitutions in the N-terminal portions of Notch receptors, all of which are predicted to produce loss of Notch function. Some of these mutations simply lead to a failure to produce Notch protein, but occasional point mutations or truncations result in the expression of dominant negative decoy receptors with disabled or deleted intracellular domains (89). Loss-of-function mutations in Notch receptors are particularly prevalent in squamous cell carcinomas of the skin (89), head and neck (90; 91), esophagus (92), and lung (89; 93), and also are seen in small cell lung cancers (94), urothelial carcinomas (95), and low-grade gliomas (96). The identification of disruptive Notch mutations in squamous cancers was presaged by experiments showing that Notch1 deletion greatly increases the incidence of skin tumors in mice exposed to carcinogens (97) and dominant negative MAML1 is a potent inducer of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (98).

Somatic mutations involving components of the Notch signaling pathway other than Notch receptors have been reported in cancers, but are generally less common. A possible exception to this rule is found in one recent study reporting frequent RBPJ copy number loss and diminished RBPJ protein expression in a sizable minority of several types of carcinoma, particularly breast cancers. It is proposed that the reduction in RBPJ gene dosage in cancers in which Notch has an oncogenic role, such as breast cancer, leads to the derepression of oncogenic Notch target genes, presumably because of a failure of RBPJ to recruit co-repressors to genomic regulatory elements (99). However, this same study also identified RBPJ deletions in tumors in which Notch has a clear tumor suppressive role, such as squamous cell carcinoma, suggesting that the relationship between altered RBPJ gene dosage and carcinogenesis is complex and may vary depending on tumor type. Other work has shown that MAML2 is frequently involved by translocations in mucoepidermal carcinoma (100), but the resulting CRTC1-MAML2 fusion gene does not appear to alter Notch signaling.

To summarize, based on mutational patterns, it is clear that Notch receptors can function as cell autonomous oncoproteins, cell autonomous tumor suppressors, or microenvironment-dependent oncoproteins in different cellular contexts. With this as an overview, we will now discuss specific cancer-relevant Notch functions, focusing on the cell autonomous actions of Notch in tumor cells.

NOTCH, CELL GROWTH, AND WARBURG METABOLISM

The best-characterized oncogenic function of Notch in human cancers is to turn on programs of gene expression that support increased cell growth. Much of this work has been conducted in human and murine T-ALL primary tumors and cell lines and is centered on the ability of Notch to increase expression of Myc (101–103), a global regulator of pro-growth metabolism (104). In line with the importance of Myc as a Notch target gene, transgenic expression of Myc in hematopoietic progenitors drives the development of Notch-independent T-ALL in mice (105) and in zebrafish (106), and retroviral expression of Myc partly or completely rescues Notch-addicted human T-ALL cell lines from Notch pathway inhibition (107).

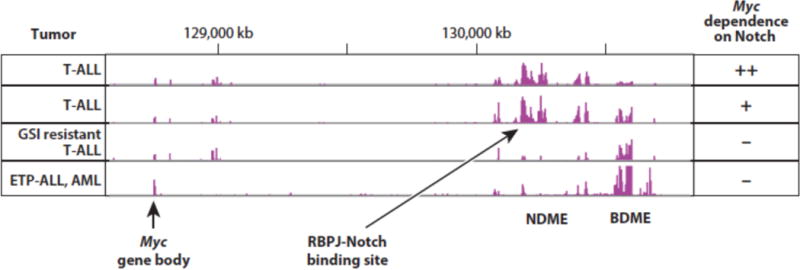

The question of precisely how Notch regulates Myc was addressed recently by several groups that used chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled to Next Gen Sequencing (ChIP-Seq) to identify genomic Notch response elements in an unbiased fashion. Studies with anti-Notch1 antibodies and antibodies that recognize certain “activated” chromatin marks such as acetylated H3K27 revealed a large multidomain enhancer >1 Mb 3′ of Myc that binds Notch transcription complexes (NTCs) (108; 109). Remarkably, deletion of a 1Kb sequence (termed the Notch dependent Myc enhancer, or NDME) that includes the enhancer binding sites for RBPJ completely abolished the ability of Notch to drive Myc expression in T-ALL cells and in normal thymocytes, yet apparently produces no other deleterious phenotypes in mice (suggesting that many lineage-specific enhancers are likely to be located in the large “gene desert” surrounding Myc) (108). Similar far-ranging effects of Notch on other large enhancer regions in T-ALL cells also have been observed (31). Thus, binding of NTCs to a single regulatory element can control the activation state of large chromatin domains through unknown mechanisms that must involve the recruitment and highly regulated “spreading” of histone modifying complexes.

Another measure of the importance of Myc as a Notch target is that resistance to Notch inhibitors (such as GSIs) is associated with re-expression of Myc via Notch-independent mechanisms (110; 111) (Figure 5). In T-ALL cells, this appears to involve epigenetic “remodeling” of the Myc 3′ enhancer. Specifically, GSI resistant cells appear to adopt a Myc enhancer state in which enhancer domains immediately adjacent to the NDME are silenced and Myc expression instead relies on an adjacent enhancer domain that has been previously shown to regulate Myc expression in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells (109; 112). This alternative enhancer domain has been shown to depend on the bromodomain protein BRD4 for its function, and hence has been termed the BRD4-dependent Myc enhancer (BDME). As would be anticipated, T-ALL that adopt the GSI-resistant state are hypersensitive to BRD4 inhibitors (111), and combining GSI and BRD4 inhibitors appears to have at least additive anti-leukemia effects in xenografted models of T-ALL (111; 113). It remains to be determined if this phenomenon of Myc enhancer “plasticity” explains the relatively modest effects of GSI treatment to date in clinical trials conducted in patients with relapsed/refractory T-ALL. Similarly, we also have observed that some T-ALL cell lines that are exceptionally sensitive to GSI have an active NDME and a relatively silent BDME (Figure 5). It will be of interest to determine if this alternative enhancer state correlates with better responses to GSIs and other Notch inhibitors in preclinical models and in patients treated within the context of clinical trials.

Figure 5.

H3K27 acetylation patterns in the 3′ Myc enhancer region predict response to Notch pathway inhibitors. T-ALL, T acute lymphoblastic leukemia; ETP-ALL, early T progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; NDME, Notch dependent Myc enhancer; BDME, Brd4 dependent Myc enhancer.

Beyond influencing Myc, Notch signaling has been shown to interact with a number of other pro-growth pathways in cell types in which it has oncogenic activity. One of the most notable examples is found in the ability of Notch to enhance PI3K-Akt signaling in T-ALL cells, probably through multiple mechanisms. Notch appears to be able to suppress expression of the tumor suppressor Pten, which normally acts as a brake on PI3K-Akt signaling, through induction of Hes1, which functions as a transcriptional repressor (114). In T-ALL cells, Notch also binds to long-range enhancers controlling the expression of several surface receptors that transduce signals leading to PI3K-Akt activation, such as the IL7 receptor (31; 115) and the IGF1 receptor (31; 116).

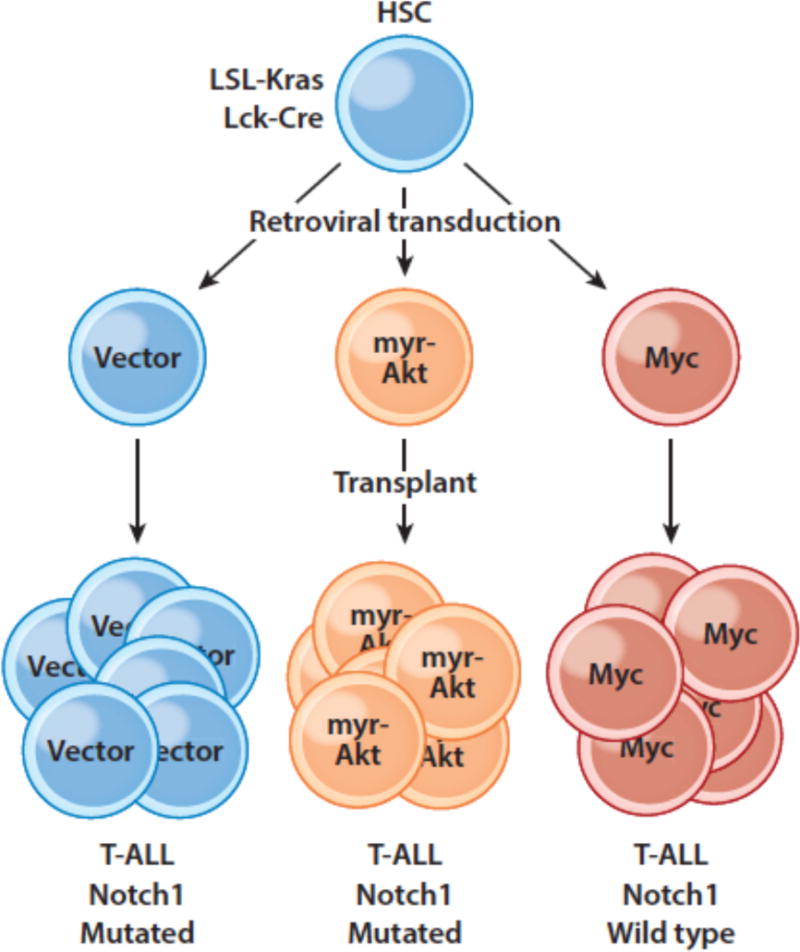

Akt has a number of pro-oncogenic activities, including increasing the expression of glucose transporters that augment Warburg metabolism, and some studies suggest that Pten loss-of-function mutations, which are often seen in T-ALL, lead to resistance to Notch inhibitors (114). However, in experiments conducted in a conditional mutant Kras model of T-ALL, we found that retroviral expression of Myc completely suppressed the acquisition of Notch1 gain-of function mutations and that Myc driven T-ALLs were accordingly GSI resistant (Figure 6). By contrast, T-ALLs arising in a model in which there was retroviral expression of constitutive active Akt still acquired Notch1 gain-of-function mutations and retained GSI sensitivity. Thus, while crosstalk between Notch and PI3K-Akt may well contribute to the genesis and maintenance of T-ALL, the weight of the evidence points to a preeminent role for the Notch-Myc signaling axis in this particular tumor type. Of note, other common mutations that are seen in T-ALL, particularly dominant negative mutations in Fbxw7, may also act to increase Myc protein levels.

Figure 6.

Enforced expression of Myc, but not myristylated Akt, suppresses the selective drive for Notch1 mutations in murine T-ALL. Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) engineered to develop Kras-driven T-ALL were transduced with retroviruses expressing only GFP, myristylated Akt, or Myc and transplanted into recipient mice, which were monitored for T-ALL development.

Is Myc a direct Notch target in all tumor types in which Notch gain-of-function mutations are observed? The answer is not in, as direct Notch target genes have yet to be firmly identified in Notch-mutated B cell tumors and breast cancers (most work has been confined to a few cell lines) and are completely unknown in other tumor types such as adenoid cystic carcinoma. One recent report using feeder cells observed that Notch ligands appear to upregulate Myc expression and certain aspects of Warburg metabolism in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells (117), suggesting that Notch-mutated B cell tumors also rely on the Notch-Myc connection. Other work in mouse models has suggested that Myc is essential for development of Notch-induced breast cancer (118). Since deletion of the NDME has no effect on B cell and mammary development, if Notch is indeed directly driving Myc expression in B cell tumors and breast cancers, it must do so through other regulatory elements in these tumors. In the case of B cell tumors, a likely alternative regulatory element is found approximately 0.5 Mb 5′ of the Myc gene body, as prior work in Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) transformed B cells has identified RBPJ binding sites in this region that also bind EBNA2, a “Notch-like” EBV-encoded RBPJ binding protein (119). Notch-regulation of Myc in breast cancer cells has been proposed to occur through an RBPJ binding site in the proximal Myc promoter (118), but an unbiased genome-wide ChIP-Seq analysis to identify RBPJ/Notch binding sites in the genomes of breast cancer cells has yet to be performed. On the other hand, detailed analysis of a case of human _Notch1_-mutated early T cell progenitor ALL that responded completely to GSI treatment argues that target genes other than Myc must be important in some tumors (120). Specifically, in this highly responsive case the Myc 3′ enhancer was in the “AML” configuration in which Myc expression is independent of Notch, and accordingly treatment of this tumor ex vivo with GSI did not alter Myc expression. This case highlights the importance of correlative studies within the context of clinical trials to understand why tumors respond (or fail to respond) to Notch inhibitors.

Other work has focused on potential interactions between Notch, hypoxia, HIF transcription factors, and tumor cell metabolism (42; 65; 121). Crosstalk has been proposed to occur at multiple levels in particular cell contexts, but whether these observations can be extended generally to cancers in which Notch signaling has pro-oncogenic functions is uncertain.

NOTCH AND CELL SURVIVAL

As already mentioned, Notch activation has been proposed to augment PI3K-Akt signaling in T-ALL as well as in other contexts as divergent as the developing Drosophila eye (114). Akt lies at the center of a signaling node that phosphorylates a large number of substrate proteins and thereby regulates a number of potentially oncogenic activities, including cell survival via inhibition of Foxo transcription factors, activation of NF-kB, and phosphorylation of components of the caspase cascade and downstream effectors of apoptosis such as Bad (122).

As a general rule, Notch activation is often correlated with activation of NF-kB, a pro-survival transcription factor that is hyperactive in many cancers, but the mechanism by which this occurs is not well understood and may be multifactorial. In addition to activation via PI3K-Akt (described above), it has been proposed in T-ALL that the Notch gene Hes1 suppresses the expression of the tumor suppressor Cyld, an inhibitor of NF-kB, leading to NF-kB activation and enhanced T-ALL cell survival (123). However, individuals with inherited mutations in Cyld have not been reported to be susceptible to T-ALL, and somatic Cyld loss-of-function mutations have yet to be described in T-ALL or other tumors in which Notch has an oncogenic function. Other work suggests that activated Notch stimulates the expression of genes encoding NF-kB transcription factors such as Relb and Nfkb2 in T-ALL cells (124), or that Notch stimulates NF-kB activity by promoting its nuclear retention (125).

Multiple lines of investigation have identified Notch as a mediator of increased tumor cell survival in the context of chemotherapy. Bevan’s group was the first to show that activated Notch protected thymocytes and T-ALL cells from glucocorticoid-mediated apoptosis (126), an effect that is proposed to stem from Notch-dependent upregulation of Akt leading in turn to phosphorylation and nuclear export of glucocorticoid receptors (127). Similarly, groups doing unbiased screens for drugs that synergize with Notch inhibitors to kill T-ALL cells have confirmed strong synergistic interactions between Notch pathway inhibitors and glucorticoids (128; 129). These observations have provided the rationale for clinical trials of GSIs combined with glucocorticoids such as dexamethasone in patients with relapsed/refractory T-ALL.

Other focused studies have produced evidence that the introduction of strong gain-of-function Notch alleles into melanoma and breast cancer cell lines affords relative protection against drugs that target estrogen receptor and the MAPK signaling pathway (130). However, the precise mechanisms by which Notch protects cancer cells from chemotherapy in vitro and the relevance of this activity to drug resistance in vivo remain to be determined.

NOTCH AND TUMOR CELL FATE CHOICES

Arguably, the best characterized developmental role for Notch is as an arbiter of cell fates within multipotent progenitors, as perturbation of Notch signaling often leads to hyperplasia of one cell type, frequently at the expense of alternative fates. Well-characterized mechanisms of cell fate determination involving Notch include lateral inhibition, induction (e.g., T cell development), and sensitization of cells to other signaling pathways that influence fate choices (e.g., sensitization of non-polarized activated T cells to chemokines/cytokines that skew helper T cell fate). In an unexpected wrinkle on this theme, other recent work has shown that ligand-mediated Notch signaling prevents secretory cells in pulmonary airways from directly transdifferentiating into non-secretory ciliated cells (131).

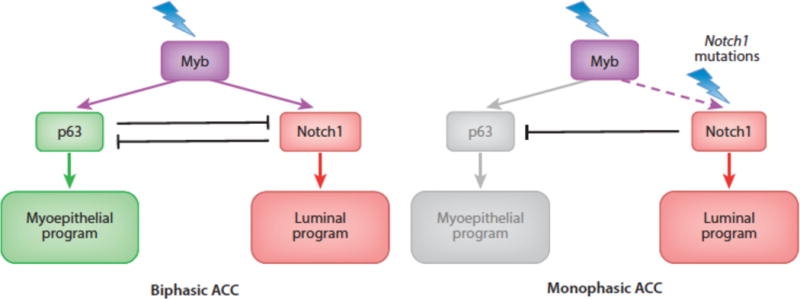

It thus might be expected that in tumors characterized by the presence of multiple cell types, Notch signaling might act by favoring one cell fate at the expense of others. This expectation has recently been realized in studies of adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) (132), an epithelial cancer that most commonly arises in salivary gland or the trachea and occasionally occurs in other sites such as the breast. ACC is highly associated with gene rearrangements that drive expression of Myb, a pioneer DNA-binding factor that is believed to be a key driver of cellular transformation in this particular tumor type. Most ACCs (roughly 90%) are biphasic tumors composed of variable mixtures of myoepithelial cells and gland-like epithelial cells, both of which harbor the same founding Myb rearrangement. The remaining 10% of tumors are “solid” variants composed only of epithelial cells that tend to pursue a much more aggressive clinical course.

Our interest in ACC was piqued by the recent discovery by several groups of gain-of-function Notch1 mutations in roughly 10% of ACCs (70–72). Using a reliable immunohistochemical stain that is specific for activated Notch1 (85), we noted that virtually all ACCs have ongoing Notch1 activation, but in two distinct patterns. In biphasic ACCs, only a subset of cells is activated Notch1 (NICD1) positive, whereas in solid variants all cells contain NICD1. We subsequently determined that in both tumor types, NICD1 is confined to p63-negative epithelial cells, whereas myoepithelial cells are positive for p63 and negative for NICD1. Finally, we noted that solid tumors have a high incidence of Notch1 gain-of-function mutations.

These results are consistent with a model in which a Myb transformed bipotent epithelial precursor gives rise to two lines of differentiation depending on the Notch activation state of the cells (Figure 7). In Notch1 wildtype tumors, differentiating cells assort into two fates, one (epithelial) Notch-on/p63 off, the second (myoepithelial) Notch-off/p63 on. How this occurs is unclear, but ACC tumor cells express ligands such as Jag1, suggesting a lateral inhibition-type mechanism. When a Notch1 gain-of-function mutation is acquired, the myoepithelial fate is suppressed at the expense of the epithelial fate, which appears to be associated with more aggressive cellular behavior. Recognition of an important role for Notch in ACC has led to new trials of Notch pathway inhibitors in this disease. Whether Notch will prove to have similar roles in other biphasic human cancers remains to be ascertained.

Figure 7.

Myb/p63/Notch1 transcriptional hierarchies in adenoid cystic carcinoma.

The ability to influence differentiation also may explain the strong selection for Notch loss-of-function mutations in squamous cell carcinomas, which in total likely are the most common tumors with Notch mutations. Interestingly, the basis for the tumor suppressive activity of Notch in squamous epithelia may again involve crosstalk with p63. In squamous epithelia, p63 is preferentially expressed in basilar cells, on which p63 confers self-renewing activity (133). As these cells divide along an axis parallel to the basement membrane, one daughter cell leaves the basal niche and assumes a suprabasilar position. Here, ligands expressed on neighboring cells activate Notch, which (as in ACC) appears to oppose the action of p63 (134). However, p63 downregulation and Notch activation in the context of squamous epithelia initiates a program of cell cycle arrest and terminal squamous differentiation (135), functions that are tumor suppressive. Precisely how Notch achieves these tumor suppressive functions awaits unbiased studies designed to identify functional RBPJ/Notch binding elements in the genomes of keratinocytes and other squamous cell types. The same knowledge gap also exists in other cancers in which Notch has tumor suppressive roles, such as urothelial carcinoma (95), small cell lung cancer (94), and low-grade gliomas (96).

Notch1, Notch2, and Notch3 are expressed in squamous epithelial cells and some squamous cancers have mutations in multiple Notch genes (89), suggesting that there is ongoing selection for subclones with ever decreasing Notch signaling tone. This may explain why models that employ ectopic expression of pan-Notch inhibitors such as dominant negative MAML1 (98) are more potent inducers of squamous cancers in mice than are conditional knockouts of individual Notch genes (97). It is also notable that certain strains of human papilloma virus (HPV) express variant E6 proteins that target and inhibit the function of MAML1 instead of p53 (136–138), one of a number of examples of viruses hijacking the Notch signaling pathway to support their life cycle (Table 2).

Although genetic evidence for a tumor suppressive role of Notch is strong in squamous cancers, it is clear that loss of Notch function is not sufficient to cause them. Patchy expression of dominant negative MAML1 in the basal epithelium cells of the esophagus enhances self-renewal, allowing the Notch-inhibited cells to outcompete their neighbors, but tumors do not occur (139). Similarly, sequencing of human skin from sun-exposed individuals has identified frequent loss-of-function Notch gene mutations in non-neoplastic skin (140). Other work has suggests that defective Notch signaling in the skin, either in the epidermis or the dermis, compromises epidermal barrier and secretory functions so as to promote pro-oncogenic inflammatory responses (141; 142). How host response factors, as well as common mutations in other genes such as TP53, interact with defects in Notch signaling to cause squamous cancers are yet to be well understood.

MAINTAINING STEMNESS

While there is no evidence to suggest that Notch is a general “stemness” factor, in certain lineages Notch activation appears to favor maintenance or expansion of stem cell pools at the expense of differentiation, an activity with obvious potential cancer relevance. Notably, mouse models have consistently implicated Notch in maintenance of neural stem cells in the fetal brain (143; 144). These observations and others from developmental biology have led investigators to hypothesize that Notch might have a similar role in maintaining cancer stem cell populations, particularly in solid tumors such as glioblastoma (145; 146), ovarian cancer (147; 148), and breast cancer (149; 150). Multiple studies using cell lines and 3-dimensional organotypic explants have shown that Notch inhibitors decrease expression of markers that correlate with “stemness” and that Notch inhibitors sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapy and radiation. Other work in mouse models of breast cancer driven by oncogenes such as Her2 have suggested that in vivo Notch is involved in producing tumor dormancy (151), a phenomenon whereby tumor cells enter a prolonged cell cycle arrest, a state of “hibernation” that results in resistance to therapies that target actively growing cells. Most of these models lack mutations in Notch genes, suggesting that Notch activation depends on ligand engagement with Notch receptors in a microenvironmental niche. There is evidence in ovarian cancer that Notch activation occurs preferentially in tumor cells near small vessels (152), which express both Jagged and Delta ligands and could be involved in creation of such a niche. In line with this idea, another model proposes that soluble Jag1 released from endothelial cells by ADAM metalloproteases activates Notch in nearby colorectal carcinoma cells and imparts a stem-like phenotype (153). Parenthetically, this is not the first report suggesting that shed Jag1 supports stem cell maintenance by activating Notch (154), an effect that runs counter to current models of Notch activation and that remains to be explained mechanistically. To date, however, the beneficial effects of Notch inhibition in preclinical models where Notch is proposed to promote “stemness” or tumor dormancy have yet to translate to clinical trials in which Notch inhibitors are combined with conventional therapies.

TRIGGERING EPITHELIAL-MESENCHYMAL TRANSITION (EMT) AND METASTASIS

EMT is an alteration in cell state marked by downregulation of proteins involved in intercellular adhesion such as E-cadherin, reorganization of the cellular cytoskeleton, and upregulation of markers of mesenchymal cells such as vimentin. It can be induced by expression of the transcription factors Snail, Slug, Twist, and Zeb1, which directly regulate genes that mediate EMT. Many signaling pathways have been implicated in control of EMT, including Notch. For example, EMT is required for endocardial cushion formation during cardiac development, and Notch deficiency has been reported to lead to defects in Snail and Slug expression and endocardial cushion EMT (155; 156).

In the context of cancer, EMT has been implicated in metastasis, tumor initiating capacity, and drug resistance (157). Since the ability of Notch to skew cell states such as fate choices is well established, a direct role for Notch in EMT is plausible. Indeed, multiple reports over the past decade have proposed that Notch has a role in promoting tumor metastasis (121; 158–164) as well as resistance to both conventional chemotherapy (148; 165–167) and targeted therapy (130; 168). However, the connections between Notch and EMT are less pervasive, both during development and in cancer, than are connections between EMT and other pathways, particularly the TGFβ signaling pathway. Moreover, there are few if any examples in which it has been shown that altered Notch signaling mediates tumor-resistance to drugs in patients on clinical trials. This is a critical issue, since several recent studies using lineage tracing in mouse models of solid tumors have produced intriguing evidence that the principal effect of EMT is to slow cellular proliferation and render cancer cells more resistant to therapy, with little or no impact on the incidence of metastasis (169; 170). Thus, while targeting of EMT remains a logical goal, the rationale for doing so may be in a state of flux and the importance of Notch in EMT remains unsettled.

Other workers have proposed that Notch ligands expressed by stromal cells trigger tumor cell invasion or support the growth of tumor cells by activating Notch in the metastatic niche. An example of the former effect has been observed in mouse models of colorectal carcinoma, in which it is proposed that ligands expressed on vessels activate Notch and stimulate tumor invasion and intravasation, effects that are suppressed the endogenous RBPJ-binding corepressor Aes (161) and promoted by a Notch/Dab/Trio signaling axis (162). Following tumor cell extravasation, Jag ligands expressed on osteoblasts in bone and astrocytes in brain have been implicated in the growth of metastatic breast cancer in mouse models (163; 171). As with EMT, whether these are general functions of Notch of broad relevance in human cancer remains to be established.

ENHANCING GENOMIC INSTABILITY

Notch has been proposed to participate in context-specific crosstalk with pathways that regulate genomic stability, particularly the p53 response. As already discussed, PI3K-Akt signaling appears to be augmented by Notch in some tumor types. Among Akt substrates is Mdm2, a negative regulator of p53 stability whose nuclear localization and activity appears to be increased by Akt-dependent phosphorylation (172). Notch signaling rises to a crescendo during normal thymocyte development at the time of β-selection when TCRβ rearrangements are occurring, and it makes intuitive sense that cells undergoing programmed DNA breakage might need to downregulate TP53 to prevent unwanted activation of the DNA damage response. Notch-mediated suppression of TP53 expression might also explain why TP53 mutations are relatively rare in primary T-ALL (this is not true of cell lines, which often have TP53 mutations). In line with this idea, in some murine T-ALL models withdrawal of Notch signals leads to p53 upregulation and tumor regression (173). However, precisely how Notch suppresses TP53 in the context of immature T cells remains an unsolved mystery. There also is evidence of complex interactions between Notch and TP53 in contexts such as squamous epithelial cells in which Notch functions as a tumor suppressor (174). These proposed interactions have been reviewed elsewhere and will not be discussed further here.

NOTCH AND STROMAL-TUMOR CELL INTERACTIONS

Together with VEGF, Notch has an essential role in coordinating many aspects of vessel development and maintenance (175) and cancer-related neoangiogenesis (176). The latter relies on Notch1 activation by the ligand Dll4, which has provided part of the rationale for ongoing trials of Dll4 blockade in cancer patients. Dll4 blockade has measurable anti-tumor effects in animal models of various cancers (177), but this has yet to translate into clear therapeutic signals in clinical trials. Alternatively, Notch has also been implicated as a key general co-activator of T cells (178) and as a pathway that favors polarization of activated macrophages towards the M1 state (179; 180), both of which could augment the host immune response against cancer in the local microenvironment.

Because of the complexity of these roles and the difficulty of measuring Notch activation and downstream effects in tumors, the remains much uncertainty about the overall contribution of Notch to the biology of stromal-host cell interactions. Nonetheless, some intriguing preclinical data have emerged that suggest that modulation of host responses with selective Notch pathway inhibitors holds therapeutic promise. For example, short-term treatment with Dll4 or Notch1 blocking antibodies in the immediate post-transplant setting abrogates graft-versus-host disease without any measurable deleterious effects on graft-versus-leukemia effects (181), possibly because of a role for Dll4 expressed on lymph node stromal cells in priming of Notch-expressing T cells (182). Further investigation of Notch effects on host immunity in various disease settings clearly appears to be merited.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The varied outcomes of Notch signaling in normal and transformed cells emphasizes the importance of direct determination of Notch effects in cell types of interest, rather than attempting to do so by extrapolation from studies conducted in other cell types. The varied outcomes of Notch signaling in normal and transformed cells emphasizes the importance of direct determination of Notch effects in cell types of interest, rather than by attempting to extrapolate from studies conducted in other cell types. It is likely that some of the current contradiction and confusion with respect to the role of Notch in cancer has resulted from studies reported using such misguided extrapolations. Other tumors in which important roles for Notch have been proposed but where a causal link remains unclear include myeloid neoplasms (183; 184), ovarian cancer (185), and melanoma (186). Part of the uncertainty in these tumor types is the failure to identify recurrent mutations in Notch genes, which can be taken as incontrovertible evidence of a role for Notch in that tumor type. In tumors in which acquired Notch mutations are frequent, it still remains for investigators to determine which of many potential roles Notch might be playing in their tumor of interest. These roles are reasonably well understood only in T-ALL, and there is much work that remains to be done to determine the oncogenic function of Notch in other Notch-associated cancers such as triple negative breast cancer, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and B cell lymphomas and leukemias, as well as the tumor suppressive functions of Notch in squamous cell carcinomas and other tumors.

In the absence of mutational evidence, a role for Notch in any given cancer can also be probed by determining phenotypes that result from perturbation of Notch signaling with specific inhibitors. GSIs have the advantage of being cheap and easy to obtain, but are broad-spectrum inhibitors associated with both on-target toxicity and off-target effects. A number of pharmaceutical companies, by contrast, have produced highly selective antibody inhibitors of individual Notch receptors and ligands (131; 176; 187–190), which are in many ways ideal for testing the role of Notch signaling components in individual cancers. They also have the potential to reveal completely new and unexpected functions, such as the role of Jagged ligands in preventing the transdifferentiation of secretory cells into ciliary cells in the tracheal mucosa (131). The important caveat to the use of antibodies is that some tumor-associated Notch receptor mutations can both activate the receptor and prevent effective targeting by antibody, a limitation of importance to both lab- and clinic-based investigators.

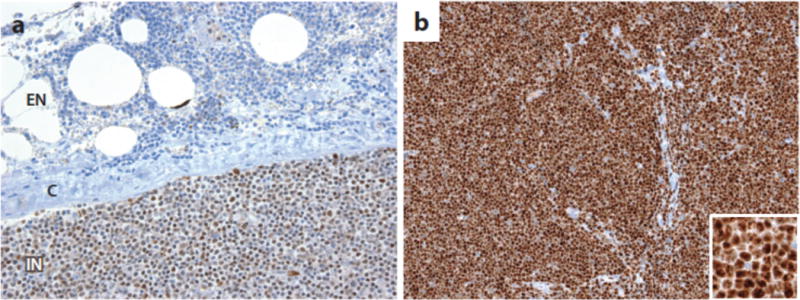

Work on the role of Notch signaling in cancer also has been hampered by the lack of diagnostic reagents and biomarkers. There are relatively few well-characterized, reliable reagents for identifying Notch pathway components in archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor samples, and as mentioned gene signatures for Notch activation have been determined in only a few cellular contexts. Two currently available immunohistochemical tests that appear to be reliable use monoclonal antibodies that specifically detect neoepitopes created by gamma-secretase cleavage of Notch1 (85) and Notch3 (191), enabling the detection of activated Notch1 and Notch3 in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples (Figure 8). In principle, it should be possible to develop analogous tests that are specific for activated Notch2 and Notch4. Also needed are reliable tests for Notch ligands, particularly members of the Delta-like family. Development of a more complete and robust set of biomarker tests related to Notch and its downstream effects would benefit investigators and also help guide clinical trials of Notch pathway inhibitors, none of which to date have used biomarkers as criteria for patient selection. Only when these additional tools are available is it likely that the complex roles of Notch in cancer will be fully unraveled, hopefully in turn setting the stage for better designed, more efficacious trials of Notch pathway inhibitors in cancer patients.

Figure 8.

Detection of activated Notch in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. A) Staining for activated Notch1 in a lymph node involved by chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) associated with a Notch1 PEST domain mutation (85). Note that the staining is nuclear and is stronger in intranodal (IN) cells than in extranodal (EN) cells, presumably due to ligand-mediated Notch1 activation in the nodal microenvironment. C, lymph node capsule. B) Detection of activated Notch3 in human TALL1 cells, which carry a Notch3 allele an activating mutation in the Notch3 negative regulatory region (191). Strong nuclear staining is observed in the tumor cells using an antibody specific for activated Notch3 (191).

SUMMARY POINTS.

- Notch signals have broad cell autonomous and non-cell autonomous roles in cancer, both oncogenic and tumor suppressive

- Analyses of human cancers have identified 3 distinct patterns of Notch mutations, including tumors with strong gain-of-function mutations (e.g., T-ALL), tumors with microenvironment-dependent weak gain-of-function mutations (e.g., CLL), and tumors with loss-of-function mutations (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma).

- In tumors with strong gain-of-function Notch mutations, Myc is a frequent target gene that appears to have important roles in driving Notch-dependent tumor cell growth. Myc regulation occurs through lineage specific enhancers that appear to show considerable “plasticity”, a characteristic that may contribute to escape from Notch addiction.

- Notch also has been implicated in cancer cell metabolism, survival and drug resistance; maintenance of cancer stem cells; epithelial-mesenchymal transition; and genomic instability; however, the mechanistic details underlying these activities and how broadly applicable they are to cancer remain to be ascertained.

FUTURE ISSUES.

- It is important to determine if it is possible to simultaneously target multiple “accessible” Myc enhancer states in particular Notch-addicted tumors, thereby increasing the efficacy of therapeutic combination including Notch pathway inhibitors.

- Studies need to be designed that permit the identification of key target genes in tumors such as CLL in which Notch signaling appears to be advantageous to the tumor only within particular microenvironments, as well as in contexts in which Notch has tumor suppressive roles.

- Additional work is needed to confirm, extend, and mechanistically delineate the possible role of stromal/tumor cells interactions in imparting tumor cell stemness and dormancy via Notch activation.

- Better reagents need to be developed to gauge Notch signaling and the expression of Notch signaling components in diverse tumor types, particularly in archival human tumor collections.

- In addition to conditional mouse models, selective antibody inhibitors of ligands and receptors offer a path forward to understanding their contributions in specific kinds of tumors.

Acknowledgments

J.C.A., W.S.P., and S.C.B. are supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (P01 CA119070, R01 AI047833, and R01 CA92433), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (7003-13), the William Lawrence & Blanche Hughes Foundation, and the Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma Research Foundation.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

J.C.A., W.S.P., and S.C.B. do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Krebs LT, Xue Y, Norton CR, Shutter JR, Maguire M, et al. Notch signaling is essential for vascular morphogenesis in mice. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1343–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamada Y, Kadokawa Y, Okabe M, Ikawa M, Coleman JR, Tsujimoto Y. Mutation in ankyrin repeats of the mouse Notch2 gene induces early embryonic lethality. Development. 1999;126:3415–24. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domenga V, Fardoux P, Lacombe P, Monet M, Maciazek J, et al. Notch3 is required for arterial identity and maturation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2730–5. doi: 10.1101/gad.308904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ladi E, Nichols JT, Ge W, Miyamoto A, Yao C, et al. The divergent DSL ligand Dll3 does not activate Notch signaling but cell autonomously attenuates signaling induced by other DSL ligands. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:983–92. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geffers I, Serth K, Chapman G, Jaekel R, Schuster-Gossler K, et al. Divergent functions and distinct localization of the Notch ligands DLL1 and DLL3 in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:465–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman G, Sparrow DB, Kremmer E, Dunwoodie SL. Notch inhibition by the ligand DELTA-LIKE 3 defines the mechanism of abnormal vertebral segmentation in spondylocostal dysostosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:905–16. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hozumi K, Mailhos C, Negishi N, Hirano K, Yahata T, et al. Delta-like 4 is indispensable in thymic environment specific for T cell development. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2507–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radtke F, Wilson A, Stark G, Bauer M, van Meerwijk J, et al. Deficient T cell fate specification in mice with an induced inactivation of Notch1. Immunity. 1999;10:547–58. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrawes MB, Xu X, Liu H, Ficarro SB, Marto JA, et al. Intrinsic Selectivity of Notch 1 for Delta-like 4 over Delta-like 1. J Biol Chem. 2013 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.454850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hozumi K, Negishi N, Suzuki D, Abe N, Sotomaru Y, et al. Delta-like 1 is necessary for the generation of marginal zone B cells but not T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:638–44. doi: 10.1038/ni1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saito T, Chiba S, Ichikawa M, Kunisato A, Asai T, et al. Notch2 is preferentially expressed in mature B cells and indispensable for marginal zone B lineage development. Immunity. 2003;18:675–85. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Logeat F, Bessia C, Brou C, LeBail O, Jarriault S, et al. The Notch1 receptor is cleaved constitutively by a furin-like convertase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8108–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rand MD, Grimm LM, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Patriub V, Blacklow SC, et al. Calcium depletion dissociates and activates heterodimeric notch receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1825–35. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1825-1835.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordon WR, Vardar-Ulu D, Histen G, Sanchez-Irizarry C, Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Structural basis for autoinhibition of Notch. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brou C, Logeat F, Gupta N, Bessia C, LeBail O, et al. A novel proteolytic cleavage involved in Notch signaling: the role of the disintegrin-metalloprotease TACE. Mol Cell. 2000;5:207–16. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mumm JS, Schroeter EH, Saxena MT, Griesemer A, Tian X, et al. A ligand-induced extracellular cleavage regulates gamma-secretase-like proteolytic activation of Notch1. Mol Cell. 2000;5:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80416-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon WR, Zimmerman B, He L, Miles LJ, Huang J, et al. Mechanical Allostery: Evidence for a Force Requirement in the Proteolytic Activation of Notch. Dev Cell. 2015;33:729–36. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le Borgne R, Remaud S, Hamel S, Schweisguth F. Two distinct E3 ubiquitin ligases have complementary functions in the regulation of delta and serrate signaling in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e96. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itoh M, Kim CH, Palardy G, Oda T, Jiang YJ, et al. Mind bomb is a ubiquitin ligase that is essential for efficient activation of Notch signaling by Delta. Dev Cell. 2003;4:67–82. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibb DR, El Shikh M, Kang DJ, Rowe WJ, El Sayed R, et al. ADAM10 is essential for Notch2-dependent marginal zone B cell development and CD23 cleavage in vivo. J Exp Med. 2010;207:623–35. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Tetering G, van Diest P, Verlaan I, van der Wall E, Kopan R, Vooijs M. Metalloprotease ADAM10 is required for Notch1 site 2 cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31018–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.006775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bozkulak EC, Weinmaster G. Selective use of ADAM10 and ADAM17 in activation of Notch1 signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5679–95. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00406-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schroeter EH, Kisslinger JA, Kopan R. Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain. Nature. 1998;393:382–6. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Struhl G, Grenwald I. Presenilin is required for activity and nuclear access of Notch in Drosophila. Nature. 1999;398:522–5. doi: 10.1038/19091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu L, Aster JC, Blacklow SC, Lake R, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Griffin JD. MAML1, a human homologue of Drosophila mastermind, is a transcriptional co-activator for NOTCH receptors. Nat Genet. 2000;26:484–9. doi: 10.1038/82644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oswald F, Tauber B, Dobner T, Bourteele S, Kostezka U, et al. p300 acts as a transcriptional coactivator for mammalian Notch-1. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7761–74. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.22.7761-7774.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mulligan P, Yang F, Di Stefano L, Ji JY, Ouyang J, et al. A SIRT1-LSD1 Corepressor Complex Regulates Notch Target Gene Expression and Development. Mol Cell. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yatim A, Benne C, Sobhian B, Laurent-Chabalier S, Deas O, et al. NOTCH1 Nuclear Interactome Reveals Key Regulators of Its Transcriptional Activity and Oncogenic Function. Mol Cell. 2012;48:445–58. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fryer CJ, White JB, Jones KA. Mastermind recruits CycC:CDK8 to phosphorylate the Notch ICD and coordinate activation with turnover. Mol Cell. 2004;16:509–20. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bray S, Musisi H, Bienz M. Bre1 is required for Notch signaling and histone modification. Dev Cell. 2005;8:279–86. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Zang C, Taing L, Arnett KL, Wong YJ, et al. NOTCH1-RBPJ complexes drive target gene expression through dynamic interactions with superenhancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:705–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315023111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skalska L, Stojnic R, Li J, Fischer B, Cerda-Moya G, et al. Chromatin signatures at Notch-regulated enhancers reveal large-scale changes in H3K56ac upon activation. EMBO J. 2015;34:1889–904. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castel D, Mourikis P, Bartels SJ, Brinkman AB, Tajbakhsh S, Stunnenberg HG. Dynamic binding of RBPJ is determined by Notch signaling status. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1059–71. doi: 10.1101/gad.211912.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li N, Fassl A, Chick J, Inuzuka H, Li X, et al. Cyclin C is a haploinsufficient tumour suppressor. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:1080–91. doi: 10.1038/ncb3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Neil J, Grim J, Strack P, Rao S, Tibbitts D, et al. FBW7 mutations in leukemic cells mediate NOTCH pathway activation and resistance to gamma-secretase inhibitors. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1813–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson BJ, Buonamici S, Sulis ML, Palomero T, Vilimas T, et al. The SCFFBW7 ubiquitin ligase complex as a tumor suppressor in T cell leukemia. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1825–35. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Espinosa L, Ingles-Esteve J, Aguilera C, Bigas A. Phosphorylation by glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta down-regulates Notch activity, a link for Notch and Wnt pathways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32227–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foltz DR, Santiago MC, Berechid BE, Nye JS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta modulates notch signaling and stability. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1006–11. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00888-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mo JS, Kim MY, Han SO, Kim IS, Ann EJ, et al. Integrin-linked kinase controls Notch1 signaling by down-regulation of protein stability through Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5565–74. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02372-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ranganathan P, Vasquez-Del Carpio R, Kaplan FM, Wang H, Gupta A, et al. Hierarchical phosphorylation within the ankyrin repeat domain defines a phosphoregulatory loop that regulates Notch transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:28844–57. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.243600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hein K, Mittler G, Cizelsky W, Kuhl M, Ferrante F, et al. Site-specific methylation of Notch1 controls the amplitude and duration of the Notch1 response. Sci Signal. 2015;8:ra30. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng X, Linke S, Dias JM, Gradin K, Wallis TP, et al. Interaction with factor inhibiting HIF-1 defines an additional mode of cross-coupling between the Notch and hypoxia signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3368–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711591105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guarani V, Deflorian G, Franco CA, Kruger M, Phng LK, et al. Acetylation-dependent regulation of endothelial Notch signalling by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Nature. 2011;473:234–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerhardt DM, Pajcini KV, D’Altri T, Tu L, Jain R, et al. The Notch1 transcriptional activation domain is required for development and reveals a novel role for Notch1 signaling in fetal hematopoietic stem cells. Genes Dev. 2014;28:576–93. doi: 10.1101/gad.227496.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okajima T, Xu A, Lei L, Irvine KD. Chaperone activity of protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 promotes notch receptor folding. Science. 2005;307:1599–603. doi: 10.1126/science.1108995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stahl M, Uemura K, Ge C, Shi S, Tashima Y, Stanley P. Roles of Pofut1 and O-fucose in mammalian Notch signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13638–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802027200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruckner K, Perez L, Clausen H, Cohen S. Glycosyltransferase activity of Fringe modulates Notch-Delta interactions. Nature. 2000;406:411–5. doi: 10.1038/35019075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luca VC, Jude KM, Pierce NW, Nachury MV, Fischer S, Garcia KC. Structural biology. Structural basis for Notch1 engagement of Delta-like 4. Science. 2015;347:847–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1261093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Acar M, Jafar-Nejad H, Takeuchi H, Rajan A, Ibrani D, et al. Rumi is a CAP10 domain glycosyltransferase that modifies Notch and is required for Notch signaling. Cell. 2008;132:247–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takeuchi H, Fernandez-Valdivia RC, Caswell DS, Nita-Lazar A, Rana NA, et al. Rumi functions as both a protein O-glucosyltransferase and a protein O-xylosyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16600–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109696108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yashiro-Ohtani Y, He Y, Ohtani T, Jones ME, Shestova O, et al. Pre-TCR signaling inactivates Notch1 transcription by antagonizing E2A. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1665–76. doi: 10.1101/gad.1793709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lamar E, Deblandre G, Wettstein D, Gawantka V, Pollet N, et al. Nrarp is a novel intracellular component of the Notch signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1885–99. doi: 10.1101/gad.908101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]