Balance of Yin and Yang: Ubiquitylation-Mediated Regulation of p53 and c-Myc (original) (raw)

Abstract

Protein ubiquitylation has been demonstrated to play a vital role not only in mediating protein turnover but also in modulating protein activity. The stability and activity of the tumor suppressor p53 and of the oncoprotein c-Myc are no exception. Both are regulated through independent ubiquitylation by several E3 ubiquitin ligases. Interestingly, p53 and c-Myc are functionally connected by some of these E3 enzymes and their regulator ARF, although these proteins play opposite roles in controlling cell growth and proliferation. The balance of this complex ubiquitylation network and its disruption during oncogenesis will be the topics of this review.

Keywords: p53, c-Myc, ubiquitylation, yin and yang, oncogenesis

Introduction: The Need for Cellular Balance

Thousands of years ago, ancient Chinese and Greek physicians saw disease as a result of imbalance in the body. This imbalance was defined as a struggle between the “yin” (negative) and “yang” (positive) forces in traditional Chinese medicine. Amazingly, this ancient theory on how illness might occur can now be demonstrated at the molecular level. In this regard, tumorigenesis is one of the best examples. Now, it is generally believed that cancer evolves from the gradual imbalance of tumor suppressors (yin) and oncoproteins (yang) due to sequential genetic and/or epigenetic alterations often initiated by physical, chemical, or biologic carcinogens in a cell, or from inherited genetic errors. It has been proposed that these alterations occur sequentially in at least three or more genes, leading to the development of human cancers (reviewed in Hahn and Weinberg [1]). A number of such yin and yang protein regulators have been identified over the past 30 years. Two intensively studied representatives are the tumor suppressor p53 and the oncoprotein c-Myc. Because they play opposing roles in controlling cell growth and proliferation, the balanced regulation of these two proteins becomes critical for the cell to grow without undergoing transformation. Over the last decade, biochemical, cellular, and genetic studies have revealed strikingly complex regulation networks for both p53 and c-Myc within the cell. One such regulation is ubiquitylation. This review will focus on the ubiquitylation of these two proteins and will summarize the most recent progress toward understanding how the cell may regulate p53 and c-Myc by employing multiple ubiquitin ligases while also discussing the relevance of their imbalance to oncogenesis (see Table 1 for summary).

Table 1.

Summary of E3 Ubiquitin Ligases for p53 and c-Myc.

| Ubiquitin Ligase | Type | Subunits | Cell Growth | Cancer Status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p53 (yin) | MDM2 | RING | 1 | + | Oncogene |

| PirH2 | RING | 1 | ? | ? | |

| COP1 | RING | 1 | ? | ? | |

| CHIP | U-box | 1 | ? | ? | |

| E6AP | HECT | 2 | ? | ? | |

| ARF-BP1/HectH9 | HECT | 1 | + | ? | |

| Cullin 7 | Cul | 2–4? | ? | ? | |

| Cul5-Roc1- | Cul | 4 | ? | ? | |

| E1B55K | |||||

| c-Myc (yang) | Skp2 | RING | 4 | + | Oncogene |

| Fbw7 | RING | 4 | - | Tumor suppressor | |

| ARF-BP1/HectH9 | HECT | 1 | + | Oncogene? |

Regulation of the Tumor Suppressor p53 (Yin) by Multiple Ubiquitin Ligases: the Tumor Suppressor p53 and Its Turnover

The tumor-suppressor protein p53 can be regarded as a yin factor because of its inhibitory role in cell growth, proliferation, and migration. This role is crucial in preventing neoplasia and tumorigenesis. Inactivation of p53 by gene-targeting depletion in mice or by an inherited heterozygous point mutation in Li-Fraumeni syndrome leads to tumor formation in various tissues [2–5]. In addition, somatic alterations of p53 that lead to its inactivation are associated with more than 50% of all types of human cancers, most of which are malignant [6–8]. Conversely, activation of p53 in response to various external (chemotherapeutics or carcinogens) and internal stresses prevents tumor formation and progression [8–10]. The tumor-suppressive function of p53 is attributed to its multipotent capability of inducing apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, senescence, and DNA repair, as well as its ability to suppress angiogenesis and metastasis [8–10]. Most of these cellular effects are mediated by effector proteins whose expression at the RNA level is stimulated by p53 [8,11], although p53 can also directly induce mitochondria-mediated apoptosis [12–14] and probably participate in DNA repair directly [15]. Hence, p53 acts as the principal “guardian” of the genome to protect an organism from oncogenesis [8].

However, an overabundance of yin is detrimental to overall balance. This statement is very true for p53. Due to its negative effect on cell growth, overactive or excess p53 is detrimental to normal cells. Thus, the p53 protein needs to be maintained at a low and inert level with a half-life of ∼ 30 minutes in order for cells to grow under normal physiological conditions. To keep this balance of p53 maintained, cells have developed an elegant proteolytic mechanism.

Proteolysis is executed by a complicated ubiquitylation-dependent 26_S_ proteasome system with multiple proteins [16]. In principal, protein ubiquitylation is catalyzed through a cascade of enzymatic reactions. Ubiquitin (a 76-amino acid polypeptide) is activated through the ATP-dependent formation of a thiol ester bond with a cystine residue of the ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1. Then, activated ubiquitin is transferred to a cystine residue of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 and conjugated to a lysine residue(s) of a protein substrate by the ubiquitin protein ligase E3. The polyubiquitylated protein, with a minimum chain of four ubiquitins, has a final destination at the 26_S_ proteasome for degradation [17].

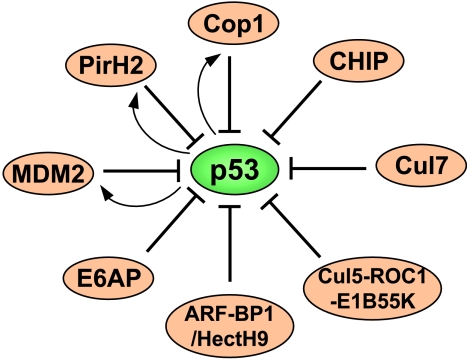

E3 plays a pivotal role in identifying a specific protein substrate for ubiquitylation. At least four classes of E3 have been reported to recognize p53 as a target for ubiquitylation, including RING, U-box, HECT (homology to E6AP C-terminal domain), and cullin/ROC1-containing ubiquitin ligase complexes (Figure 1). Therefore, p53 is under tight control by these E3 proteins, although it remains to be verified if some newly discovered E3s, as described below, are authentic to p53 in vivo and if they act in a concerted fashion to regulate p53 stability under certain physiological or pathological conditions. Elucidating the mechanisms of this control is vital for understanding how cells activate p53 to prevent transformation.

Figure 1.

A diagram showing that multiple ubiquitin E3 ligases target p53 for ubiquitylation. Bars indicate ubiquitylation and the functional suppression of p53, whereas arrows indicate the transcriptional activation of the ubiquitin E3 ligase by p53.

Ubiquitylation of p53 by the Oncoprotein MDM2

The oncoprotein MDM2 is encoded by the mdm2 gene, which was originally identified on a mouse double-minute chromosome in the 3T3DM cell line [18]. It is the most intensively studied E3 ubiquitin ligase that negates p53 function [19]. MDM2 possesses several key functional domains. The N-terminal domain of MDM2 mediates its binding to p53 [20,21]. The central acidic domain of MDM2 recently has been shown to be essential for MDM2-mediated p53 degradation, but not ubiquitylation [22–25]. In the C-terminal side of the acidic domain are a zinc finger domain with unknown function and a RING domain with intrinsic E3 ligase activity [26]. The MDM2 protein also contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and a nuclear export signal that are responsible for shuttling MDM2 between the cytoplasm and the nucleus, and possibly for regulating p53 activity [27,28]. Within the RING domain, a small region of amino acids (464–471) contains a nucleolar localization signal sequence [29]. Almost all of these functional domains are critical for the MDM2 suppression of p53 function.

MDM2 can inhibit p53's function through several of the following mechanisms. MDM2 can specifically bind to the N-terminal transcription activation domain of p53 [20,21] and directly block its transcriptional activity [21,30,31]. In addition, this binding initiates p53 ubiquitylation by MDM2, leading to proteasome-mediated p53 degradation [26,32]. MDM2 can also relocalize p53 to the cytoplasm where p53 is unable to function as a transcriptional regulator [33–36]. Finally, it has been shown that MDM2 associates with p53, and possibly with histones, promoting monoubiquitylation of histone H2B [37] on the promoters of target genes, therefore inhibiting p53's transcriptional activity [37,38]. Interestingly, the expression of MDM2 is activated by p53 [39,40]. Thus, MDM2 acts as a negative feedback regulator of p53 [41,42]. This feedback regulation is validated by two gene-targeting studies, which show that depleting the p53 gene rescues the lethality of mdm2 knockout mice [43,44].

Although the general concept of the MDM2-p53 loop is well accepted, it remains obscure how MDM2 precisely degrades p53 in cells. Currently, it is debatable where MDM2 mediates the degradation of p53 and whether MDM2 works alone to mediate this degradation in cells. As to the first question, several studies propose that MDM2 mediates p53 degradation in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm [45–47]. However, a later study suggests that MDM2 only monoubiquitylates p53, possibly at multiple lysines on its C-terminus [48] in the nucleus, and then transfers this form of p53 to the cytoplasm for polyubiquitylation and degradation [35]. A new question derived from this model is whether MDM2 acts by itself to mediate p53 polyubiquitylation in the cytoplasm. If not, two candidate proteins may fill this gap. One is p300 [49,50]. p300 was shown to act as a potential E4 enzyme and to mediate subsequent polyubiquitylation and degradation by cooperating with MDM2 [49]. However, this protein has never been shown to exist in the cytoplasm; therefore, it is a less likely contender, although it remains possible that p300 may assist MDM2 in polyubiquitylating p53 in the nucleus.

Another likely candidate is MDMX, a protein that typically resides in the cytoplasm. MDMX is a homolog of MDM2 [51]. Albeit MDMX lacks demonstrable E3 ubiquitin ligase activity [22], it works as a partner of MDM2, possibly to enhance p53's ubiquitylation and degradation [52]. The essential role of MDMX in the MDM2-p53 loop is also established by double knockout studies, showing that deleting the p53 gene rescues the lethal phenotype of mdmx knockout mice [53,54]. Again, it remains uncertain whether MDMX accelerates MDM2-dependent p53 polyubiquitylation in the cytoplasm. This speculation is seemingly contradicted by the fact that MDMX is imported to and degraded in the nucleus by MDM2 in response to ionizing irradiation [55,56]. Although there are some important pieces that are still missing in the puzzle that would provide a unified model of MDM2-mediated p53 ubiquitylation, it is likely that MDM2 may ubiquitylate p53 primarily in the nucleus and perhaps in the cytoplasm as well, with p53's monoubiquitylation or polyubiquitylation depending on the stoichiometry of these proteins and/or the existence of other helpers, such as MDMX.

A myriad of questions involving the ubiquitination of p53 by MDM2 remain. Another area that requires more examination is the precise enzymatic mechanism of this ubiquitylation. Furthermore, direct evidence demonstrating that ubiquitylated p53 molecules are destined for proteasome-mediated degradation in cells is missing [57]. Regardless of unsolved problems, it is reasonable to say that the oncoprotein MDM2, as a physiological antagonist of p53, is a positive regulator of cell growth (Figure 1). However, MDM2 is not the only negative regulator of p53, as several other associated E3 ubiquitin ligases have been identified recently.

Ubiquitylation of p53 by Other E3 Ligases

Ring domain ligases Using differential display and affinity purification approaches, two more members of the RING finger E3 ligase family, PirH2 [58] and COP1 (constitutive photomorphogenic 1), have been identified, respectively, to monitor p53 stability [59]. PirH2 and COP1 both associate with and ubiquitylate p53 independently, also without requiring the aid of MDM2. Notably different from MDM2, the PirH2 central region binds to the central sequence-specific DNA-binding domain of p53. Although deleting the RING finger abolishes PirH2 E3 ligase activity toward p53, this mutant is still able to repress p53's transactivation activity [58]. This observation suggests that PirH2 may interfere with the interaction of p53 with its DNA elements by competing for the DNA-binding domain of p53. However, an intact RING finger domain is necessary for COP1 to suppress p53 activity by ubiquitylating this protein, as the RING finger-truncated COP1 was no longer able to ubiquitylate p53 and to suppress p53's activity [59]. Like MDM2, pirh2 and cop1 genes are also transcriptional targets of p53 (Figure 1). Thus, both proteins appear to be feedback regulators of p53, although the biologic meaning of these regulatory processes requires further investigation. It will also be important to learn whether PirH2 and COP1 are oncoproteins, as well as negative regulators of p53, in vivo.

HECT domain ligases E6AP is the first known ubiquitin E3 ligase for p53 and was originally identified as a human papilloma virus protein E6-associated protein in cervical carcinoma (HeLa) cells [60]. Human papilloma viruses 16 and 18 are highly related to the pathogenesis of cervical carcinoma (90%). These viruses encode two transforming oncoproteins E6 and E7, which directly bind to the tumor suppressors p53 and pRb, respectively, and suppress their functions [61,62]. After papilloma virus infection, the E6 protein associates with and recruits the HECT domain protein E6AP to p53 in host cells to accelerate its ubiquitylation and degradation. Unlike MDM2, which only serves as a platform for the E2 to transfer activated ubiquitin to p53, E6AP possesses a special C-terminal domain that is capable of catalyzing the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a substrate [63]. E6AP does not recognize p53 directly. In normal cells without virus infection, E6AP does not ubiquitylate and degrade p53. Therefore, E6AP is a negative regulator of p53 only after cellular infection with papilloma virus.

Most recently, a new HECT member, ARF-BP1/HectH9, has been reported to target p53 as well [64] and will be discussed in Convergence of p53 and c-Myc by ARF and the ARF-BP1/HectH9 E3 Ligase section.

U-box ligases Another E3 ligase, CHIP (carboxyl terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein), has been reported to induce p53 degradation [65]. CHIP ubiquitylates p53 in vitro in the presence of Hsc70 and E2 (UbcH5b). Although both wild-type p53 and R175H mutant p53 are targeted by CHIP, CHIP appears to be more efficient in decreasing the level of mutant p53 than that of wild-type p53 because this p53 mutant is unfolded and Hsc70 often chaperones unfolded peptides [66–70]. Therefore, Hsc70 may serve as a bridge for this mutant and CHIP, facilitating CHIP-mediated R175H-p53 ubiquitylation. As to wild-type p53, Hsc70 may use the same mechanism to facilitate the CHIP ubiquitylation of unfolded p53s, which are a small fraction of the highly expressed protein. This study suggests that CHIP-mediated p53 ubiquitylation may be coupled to protein synthesis, as nascent peptides are often unfolded. Although this model is provocative, additional studies are necessary to demonstrate the physiological meaning of p53 regulation by CHIP, particularly its relationship with cancer.

Cullin-containing ligases Two cullin-containing ubiquitin ligase complexes have been reported to ubiquitylate p53. This type of complex usually consists of four components, including cullin, ROC (the RING E3 ligase), and two other proteins, forming a functional complex [71]. Interestingly, two adenoviral proteins, E4orf6 and E1B55K, cooperate in targeting p53 for ubiquitylation and degradation [72]. Purification of E4orf6-associated proteins has revealed a novel p53 ligase complex containing cullin 5, elongins B and C, E4orf6, E1B55K, and ROC1. This complex is remarkably similar to the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor and SCF E3 complexes [72,73]. Thus, in addition to the papilloma virus, the adenovirus also encodes viral oncoproteins, such as EIB55K, that suppress p53 activity [74] by degrading it through the ubiquitin-dependent proteasome pathway. By doing so, viruses would keep host cells alive for the sake of their own replication and life cycle during infection.

Besides adenovirus, human cells also use a cullincontaining complex to target p53. This complex contains cullin 7 [75] and appears to monoubiquitylate or diubiquitylate p53 in vitro and in cells. However, this ubiquitylation suppresses p53 activity without affecting p53 stability. Although it remains unclear exactly how this complex regulates the activity of p53, it is possible that the monoubiquitylation or the diubiquitylation of p53 by this complex may inhibit p53 transcriptional activity by interfering with the interaction of p53 with DNA. Surprisingly, cullin 7 resides in the cytoplasm but does not recruit p53 into this cellular compartment, leaving the puzzle of where p53 ubiquitylation actually occurs. This study, although interesting, adds more questions to the waiting list for future investigations.

Regulation of p53 Ubiquitin Ligases

As described above, half a dozen E3 ligases or ligase complexes have been identified to ubiquitylate p53. Although many of the mechanisms underlying these ubiquitylations remain largely unaddressed, the overall outcome is the same: suppression of p53 function. The cell could overcome this suppression and activate p53 to mediate cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in many ways. The easiest way would be to reverse this ubiquitylation. Indeed, a deubiquitylase called HAUSP (herpesvirus-associated ubiquitin-specific protease) has been identified to deubiquitylate p53, leading to p53 stabilization and activation [76]. However, because HAUSP also deubiquitylates MDM2 and its partner MDMX, knocking down this ubiquitin hydrolase stabilizes and activates p53 as well [77,78]. HAUSP seems to reverse MDM2-mediated ubiquitylation specifically, as it has no effect on p53 ubiquitylation by E6AP [79]. Whether it has an effect on p53 ubiquitylation by other RING finger E3 ligases, as mentioned above, is still an open question. In addition to this reverse reaction, other posttranslational modifications (such as phosphorylation, methylation, acetylation, sumoylation, or neddylation), in response to various stresses and protein-protein interactions, are also believed to play various roles in stabilizing and activating p53 by blocking the MDM2-p53 loop (for details, see latersections and Refs. [9,11,80,81]). Recently, it has been shown that 14-3-3γ can bind to MDMX, which is phosphorylated at serine 367 by Chk1 in response to UV irradiation, and this binding results in the suppression of MDMX-enhanced p53 ubiquitylation by MDM2 [82]. In contrast, ionizing radiation activates Chk2, which phosphorylates the same serine and initiates 14-3-3-MDMX binding, resulting in the MDM2-mediated degradation of MDMX in the nucleus [83]. Even though the mechanisms in both cases are unclear and await further investigation, their outcomes are the same: p53 activation [82–84]. It would be interesting and important to learn whether stress signals can also activate p53 by inhibiting other E3 ligases. These multiple levels of the ubiquitin-mediated regulation of p53 not only reflect the complexity of this network but also provide a remarkable molecular paradigm for the yin-yang balance in the cell. A second system that serves as an apt example of fine-tuned regulation and is an appropriate balance to the discussion of p53 as a major tumor suppressor is the pathway regulating a major oncoprotein, c-Myc.

Regulation of the c-Myc Oncoprotein (Yang) by Multiple Ubiquitin Ligases

The c-Myc Oncoprotein and Its Turnover

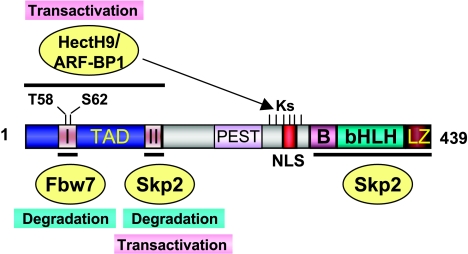

The c-Myc oncoprotein can be considered the yang factor due to its positive role in promoting cell growth and proliferation and its subsequent opposition to p53. It is a basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper (bHLH/LZ) transcription factor that is responsible for regulating a variety of genes whose protein products are involved in cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and neoplastic transformation [85,86]. The N-terminal transcriptional activation domain (TAD) of c-Myc contains two conserved segments, Myc box (MB) I and II, which are crucial for all biologic activities [87]. The C-terminal bHLH/LZ domain of c-Myc mediates sequence-specific DNA recognition of E-box elements (CACGTG) (Figure 2). However, c-Myc does not work alone and forms a heterodimer with its partner protein Max [88–90]. The c-Myc/Max heterodimer activates the transcription of many target genes. Max also acts as a transcriptional repressor when forming a heterodimer with one of the Mad family members that binds to the same E box sequence elements. In such a way, the Max-Mad complex antagonizes the function of the c-Myc-Max complex [91]. Max is ubiquitously expressed and present in stoichiometric excess to c-Myc, whereas the level of Myc and Mad is highly regulated during cell growth. Thus, the Myc-Mad ratio determines whether Max heterodimerizes with c-Myc to promote cell growth or with Mad to inhibit cell growth [92]. More complex than these regulations, the c-Myc-Max complex also counteracts the transactivation activity of another zinc finger transcription factor called Miz-1, repressing a specific set of Miz-1 target genes [89,93]. This repressive activity of c-Myc also requires Max [94–97]. Hence, c-Myc possesses transcriptional activation and repression activities toward specific target genes.

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram showing the functional domains of the c-Myc protein and its regulation by multiple ubiquitin E3 ligases. c-Myc contains an N-terminal TAD, as well as C-terminal basic (B), helix-loop-helix (HLH), and leucine zipper (LZ) domains. The central domain contains a PEST region. There are two conserved MBI and MBII motifs located in the TAD. Two phosphorylation residues, T58 and S62, are shown. Fbw7 binds to MBI and ubiquitylates c-Myc in a T58 phosphorylation-dependent manner. Skp2 targets c-Myc for ubiquitylation through both the MBII and C-terminal domains. ARF-BP1/HectH9 ubiquitylates one or more of six lysine (K) residues around the NLS region by binding to TAD. Ubiquitylation by SCFFbw7 results in the degradation of c-Myc, whereas ubiquitylation by SCFSkp2 and HectH9/ARF-BP1 leads to the activation of c-Myc.

These activities of c-Myc are highly linked to its positive role in controlling cell cycle [86] and ribosomal biogenesis [98–100]. Consistent with this notion, c-Myc levels are high during embryogenesis and in rapidly dividing cells, but considerably low in quiescent and differentiating cells. Homozygous deletion of the c-myc gene is lethal to mice at E9.5–10.5 days [101]. In addition, c-Myc-deficient cells no longer proliferate [102,103]. Conversely, overexpression of c-Myc inhibits cell differentiation independent of its ability to promote cell proliferation [104,105]. However, c-Myc also induces apoptosis when cells are under stress or when cultured with limited survival signals [106,107]. Hence, c-Myc is essential for cell growth and embryogenesis, although it also plays a role in apoptosis under stress conditions.

In contrast to the tumor-suppressing function of p53, c-Myc promotes uncontrolled cell growth and subsequent tumorigenesis. Abnormal overexpression of c-Myc due to chromosomal translocations, gene amplification, or viral insertion at the c-myc locus is highly associated with several types of human cancers [108–110]. Constitutive overexpression of c-Myc in cells inhibits differentiation and induces neoplastic transformation [111,112]. Moreover, c-myc transgenic mice develop lymphoid malignancies [113]. In addition, induced overexpression of c-myc either in the epidermis [114], in hematopoietic lineages [115], or in pancreatic islet β cells [116] of inducible c-myc transgenic mice leads to neoplastic, premalignant, and malignant phenotypes. In contrast, when c-myc expression is turned off in these mice, these tumorigenic phenotypes spontaneously remit [114–116]. These studies demonstrate that deregulation of c-Myc level or activity favors cell transformation and tumorigenesis. Therefore, tight regulation of the c-Myc level is essential for preventing cells from undergoing hyperplasia and consequent neoplasia. To do so, the cells have evolved multiple mechanisms, including transcriptional, post-transcriptional (mRNA stability and translation), and post-translational (protein stability) regulations [110], to regulate the level and activity of c-Myc. Only ubiquitin-mediated regulation of c-Myc will be discussed here because this topic is the concern of this review, and because this particular c-Myc modification is highly relevant to c-Myc's response to growth stimuli and tumorigenesis.

As mentioned above, ubiquitylation is an exceedingly powerful tool for the cell to master both a potent tumor suppressor and an influential oncogene to achieve homeostasis. Like p53 [117,118], c-Myc is also an extremely shortlived protein with a half-life of less than 30 minutes in cells [119]. Its fast turnover is carried out by the ubiquitindependent proteasome system as well [120–122]. As for other transcriptional factors whose TADs also serve as degradation signals (degrons) [123] (reviewed in Muratani and Tansey [124]), the N-terminal TAD of c-Myc, harboring two conserved MBI and MBII domains, is also involved in the regulation of c-Myc stability [121,125,126]. Although it is still debatable how these two motifs work together, or independently, to modulate c-Myc turnover [121,125,126,127], the consensus seems to be that they are crucial for c-Myc ubiquitylation and degradation. Over the past 3 years, three ubiquitin ligases, SCFSkp2 [128,139,130], SCFFbw7 [131–134], and ARF-BP1/HectH9 [135], have been identified to contact the TAD domain, leading to c-Myc ubiquitylation (Figure 2). As detailed below, SCFFbw7 ubiquitylates and degrades c-Myc in a phosphorylation-dependent manner [132,133], whereas SCFSkp2, as well as ARF-BP1/HectH9, ubiquitylates c-Myc and regulates its transcriptional activity [128,130,135]. Therefore, both p53 and c-Myc are regulated through several ubiquitylation-dependent pathways, reflecting the importance of protein stability to cellular harmony.

Ubiquitylation of c-Myc by SCFFbw7 Regulates Its Stability

In contrast to p53's case, where phosphorylation is generally believed to prevent its degradation [136–139], phosphorylation has been shown to positively and negatively regulate the stability of c-Myc [140–144]. These regulatory steps are performed through a sequential phosphorylation at serine (S) 62 and threonine (T) 58 in the MBI motif of c-Myc in response to growth signals [143]. Interestingly, c-Myc levels display a bell-shaped induction curve in response to serum stimulation [145]. This induction is regulated by Ras through a dual mechanism. First, the serum-activated Ras triggers the immediate early response of the Raf-MEK-ERK kinase cascade, which in turn leads to the S62 phosphorylation of c-Myc [143] and to c-Myc's consequent stabilization. In addition, Ras can activate the PI3K/AKT kinase cascade that leads to c-Myc stabilization by blocking the GSK3_β_ kinase-activated c-Myc degradation pathway.

This degradation process involves multiple steps. It starts with the phosphorylation of c-Myc at T58 by GSK3β [140–144]. This phosphorylation facilitates the recruitment of a prolyl isomerase, Pin1, to c-Myc. Pin1 then catalyzes cis-trans isomerization at proline (P) 63 of c-Myc, and subsequent conformational change allows the PP2A phosphatase to dephosphorylate c-Myc at S62 [146]. Finally, phosphorylated T58 and dephosphorylated S62 serve as a dock to recruit a T58 phosphorylation-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, called SCFFbw7 [131–134], to ubiquitylate c-Myc (Figure 3). The importance of T58 in regulating c-Myc stability is highlighted by the fact that T58 is frequently mutated in a subset of Burkitt's lymphomas [147–149]. Moreover, artificial mutation at T58 prevents cMyc ubiquitylation and degradation, as well as enhances the oncogenic activity of c-Myc in vitro [125,126,144,150]. Strikingly, mice harboring the c-Myc T58A mutant develop lymphomas at a significantly higher penetrance and reduced latency than mice with the wild-type c-myc transgene [151]. Thus, growth factors in sera can activate Ras, which turns on two kinase cascades. One of them mediates S62 phosphorylation and the other blocks T58 phosphorylation. In doing so, Ras can protect c-Myc from being degraded by the SCFFbw7 complex, consequently leading to c-Myc stabilization (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A diagram showing growth signal-mediated c-Myc phosphorylation and ubiquitylation pathways. Growth signals such as serum stimulation activate RAS. The RAS/Raf/MEK/ERK kinase cascade phosphorylates c-Myc at S62. The RAS-PI3K/Akt cascade inhibits GSK3_β_ activity. GSK3_β_ mediates the phosphorylation of c-Myc at T58. Phosphorylation of T58 recruits the Pin 1 prolyl isomerase, which may catalyze cis-trans isomerization at the P63 bond. This conformational change facilitates the targeting of c-Myc by PP2A phosphatase, which dephosphorylates c-Myc at S62. Phosphorylation of T58 and dephosphorylation of S62 serve as signals that trigger subsequent ubiquitylation and degradation of c-Myc by the SCFFbw7 complex.

Therefore, the SCFFbw7 complex is a critical player in the business of c-Myc turnover. This complex contains an F-box protein, termed Fbw7, that is a human ortholog of yeast Cdc4 [131–134]. Although how this complex exactly degrades c-Myc remains to be studied, it has been shown that Fbw7 directly interacts with the c-Myc MBI domain in a T58 phosphorylation-dependent manner. Overexpression of Fbw7 destabilizes wild-type, but not T58-mutated, c-Myc. Conversely, knocking down Fbw7 leads to the accumulation of c-Myc levels and enhances c-Myc transactivational activity. Similarly, the Drosophila archipelago (ago) protein, a fly ortholog of human Fbw7, interacts with dMyc. Mutations in ago result in elevated dMyc protein levels and massive growth of tissues with increased cell size and number [131]. These studies indicate that the regulation of c-Myc by the SCFFbw7 complex is evolutionarily conserved.

c-Myc is a nuclear protein, but recent evidence suggests that it may be degraded in the nucleolus, a subnuclear compartment where rRNA biogenesis takes place. A Fbw7 isoform, Fbw7γ, was found to colocalize with c-Myc in the nucleolus [134]. Specific knockdown of the Fbw7γ isoform by siRNA increases the nucleolar level of c-Myc and the size of targeted cells. It is possible that c-Myc may shuttle between the nucleoplasm and the nucleolus, and that ubiquitylation, the proteasome-mediated degradation of c-Myc, or both may occur in the nucleolus. Consistent with its inhibitory role in regulating c-Myc turnover, Fbw7 has been shown to be a potential tumor suppressor [152] (see the text below for more discussion). Thus, Fbw7 acts as regulatory factor for maintaining the balance of c-Myc.

Ubiquitylation of c-Myc by SCFSkp2 Regulates Its Transactivational Activity

Unlike p53, the ubiquitylation of c-Myc does not always mean its physical destruction or functional repression. Instead, this modification by another SCF complex, SCFSkp2, increases the activity of c-Myc [128–130]. This effect is executed through the interaction of the Skp2 subunit of the SCFSkp2 complex with the MBII and bHLH-LZ domains of c-Myc [128,130]. In contrast to the association of the SCFFbw7 complex with the MBI domain of c-Myc (see above), this interaction is phosphorylation-independent [128–130]. Although SCFSkp2 has been shown to mediate c-Myc degradation, this complex can also function as a coactivator of c-Myc by ubiquitylating it and enhancing its transcriptional activity. This dual, yet seemingly contradictory, role of SCFSkp2 in regulating c-Myc stability and activity has been postulated to be important for coupling the proteasome system with transcription. Consistent with this idea are the data showing that c-Myc also interacts with a proteasome subunit called Sug1, and this interaction positively affects c-Myc activity [129]. Furthermore, chromatin immunoprecipitation analyses reveal that c-Myc may recruit Skp2, ubiquitylated proteins, and AAA ATPase (APIS) components from the 19_S_ regulatory subunit of the proteasome to the endogenous cyclin D2 promoter, which is a c-Myc target [128]. Therefore, the MBII domain of c-Myc is not only involved in controlling its stability but also important for regulating its activity. Indeed, several coactivators, such as TRRAP-associated hGCN5 or TIP60-containing histone acetyltransferase complexes, have been shown to bind to MBII and to mediate the histone H4 acetylation of c-Myc target genes, leading to their expression [153–156]. Moreover, the TIP48/TIP49 ATPases in chromatin remodeling complexes also interact with the MBII domain of c-Myc [157]. However, it remains unknown how these coactivators interplay with SCFSkp2 in regulating c-Myc activity and how c-Myc acetylation affects its ubiquitylation during transcription under normal physiological conditions. These are important issues for future exploration.

It is intriguing that Skp2 mediates both the proteasomal degradation and the transactivational activity of c-Myc. How Skp2 is able to perform both functions is still a mystery. Although no definite answers are available thus far, a few more pieces of evidence further indirectly support this transcription-coupled proteasomal degradation mechanism. Surprisingly, inhibition of c-Myc turnover by the proteasome inhibitor MG132 leads to suppression of c-Myc's transactivational activity, even though c-Myc levels increase [100]. In addition, the 19_S_ base ATPases and the lid Rpn7 subunit, as well as the 20_S_ (α2 subunit) particles, are recruited to the cyclin D2 promoter by c-Myc [128,129]. These studies suggest that the 26_S_ proteasome may degrade c-Myc at its target promoters once this transcriptional factor fulfills its duty to activate transcription of its target genes. Alternatively, once recruiting the proteasome to its promoters, c-Myc may need to be destroyed to allow the proteasome-mediated transcriptional activation of its target genes. SCFSkp2 participates in both degradation and transcription. This type of regulation has also been shown for other transcriptional factors, such as GCN4, Vp16, and Gal1-10, in yeast [158–161]. Hence, ubiquitylation of c-Myc by the SCFSkp2 complex mediates not only its degradation but also its transcriptional activity.

Although this model is very attractive and interesting, it also raises a number of new questions, in addition to the questions mentioned above. For instance, is this regulation of c-Myc by SCFSkp2 responsive to growth signals? Do SCFSkp2 and SCFFbw7 interplay with each other in regulating c-Myc stability and activity? Do they target the same lysine residues in c-Myc for ubiquitylation? In addition, is it possible that c-Myc stability may be regulated through a postubiquitylation or a ubiquitylation-independent mechanism [126]? A more radical question is whether p53 activity or stability is also regulated through the transcription-coupled proteasome pathway. It would not be surprising if this speculation will turn out to be true, as MDM2 has been shown to associate with p53 at the target promoter [37,38]. Addressing these questions would certainly advance our understanding of the molecular details underlying c-Myc or p53 regulation by these E3 ubiquitin ligases.

Convergence of p53 and c-Myc by ARF and the ARF-BP1/HectH9 E3 Ligase

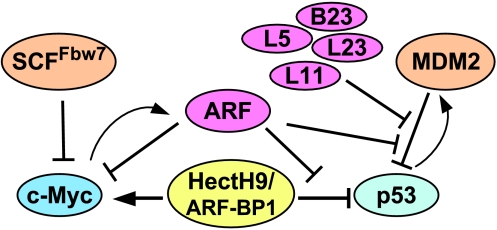

Although p53 and c-Myc play opposite roles in cell growth control and are regulated by independent E3 ubiquitin ligases, as described above, these two proteins are functionally linked through a tumor suppressor called ARF (alternative reading frame of p16_INK_, also called p14_arf_ in humans and p19arf in mice). ARF is a nucleolar protein and may play a role in rRNA processing by inhibiting B23 function [162,163]. It has been shown that c-Myc induces the expression of ARF at the level of mRNA and that ARF, in turn, activates p53 [164–167]. In addition, it has been shown that ARF induces p53 by blocking the MDM2-MDMx-p53 feedback loop [168–170]. ARF's activation of p53 contributes to its role in suppressing tumorigenesis. The tumor-suppressive role of ARF is further verified by at least two forms of genetic evidence. First, germline mutations in p14arf occur in 20% to 40% of human familial melanomas [171,172]. Second, _arf_-null mice are highly prone to cancer development [173,174]. These studies have two implications: 1) that ARF functions as a sensor of oncogenic stress, such as deregulated c-Myc activation or expression, to activate p53 against c-Myc-mediated cell transformation, and 2) that c-Myc may induce apoptosis in an ARF-p53-dependent fashion in response to nutrient deprivation. This c-Myc-ARF-p53 pathway presents a graceful molecular model of the yin-yang relationship. However, the relationship between p53 and c-Myc is far more complex than this relatively simplified version. Another E3 ligase is also involved.

Recently, three studies unveiled a member of the HECT E3 ligase family, named ARF-BP1 (ARF-binding protein 1; also called HectH9) and Mule (Mcl1 ubiquitin ligase E3) [64,135,175], which ubiquitylates three distinct protein substrates (a combined term ARF-BP1/HectH9 will be used here for the sake of simplicity). This E3 ligase is a nuclear protein with a molecular mass of 482 kDa, whose gene was originally identified and partially cloned as Lasu1/Ureb1 [176]. Two of three substrates were identified as p53 and c-Myc [64,135]. Interestingly, ARF-BP1/HectH9 directly binds to and ubiquitylates p53, as well as c-Myc, in vitro and in cells [64,135]. ARF-BP1/HectH9 was also demonstrated as an E3 ligase for both p53 and c-Myc, as ablation of this E3 protein by siRNA prevents ubiquitylation of p53 and c-Myc in cells. However, the outcomes of their respective ubiquitylations are completely divergent. Ubiquitylation of p53 by ARF-BP1/HectH9, likely through lysine 48 of ubiquitin, commits p53 to proteasome-mediated degradation [64], whereas ubiquitylation of c-Myc by ARF-BP1/HectH9, through lysine 63 of ubiquitin, enhances the transcriptional activity of c-Myc without degrading it [135]. Thus, ARFBP1/HectH9 serves as a novel linker between p53 and c-Myc. The overall outcome of this diverse regulation of these yin and yang factors by ARFBP1/HectH9 is to promote cell growth and proliferation [64,135].

Again, ARF also joins this new tangle because ARF was used as a bait to fish out ARF-BP1 and because it inhibited p53 ubiquitylation by this E3 ligase [64]. Although ARF suppresses MDM2-mediated p53 ubiquitylation, as mentioned above, both p53 ubiquitylation by ARF-BP1/HectH9 and suppression of this ubiquitylation by ARF have nothing to do with MDM2. Therefore, ARF can activate p53 by suppressing either MDM2-mediated or ARF-BP1/HectH9-mediated p53 ubiquitylation [64,170]. Because depleting ARF-BP1/HectH9 induces p53 at a much greater level than does knocking down MDM2 or Pirh2 in cells [64], it has been proposed that ARF-BP1 may play a more important role in monitoring the physiological level of p53 without any apparent stress [177]. This speculation is stimulating and requires further examination, particularly in animals. However, it may be considerably challenging to test this model in vivo, as ARFBP1/HectH9 also targets two other substrates, c-Myc and Mcl-1, and probably more unidentified ones.

It remains untested whether ARF also suppresses c-Myc activity by interfering with ARF-BP1/HectH9-mediated c-Myc ubiquitylation. However, it would not be astonishing if it does so, as ARF has been shown to directly suppress c-Myc activity [178,179]. Regardless of this remaining issue, another c-Myc suppressor, Miz-1, does inhibit ARF-BP1/HectH9-mediated c-Myc ubiquitylation, possibly by competing with the binding of c-Myc for this E3 ligase. Miz-1 is not the substrate for ARF-BP1/HectH9 [135]. Interestingly, ARF-BP1/HectH9-mediated c-Myc ubiquitylation is required for the transcriptional coactivator p300 to bind to c-Myc at c-Myc target promoters, as the c-MycK6R mutant, which is not ubiquitylated by this E3 ligase, is unable to recruit p300 to the same promoters. In this aspect, it appears that ARF-BP1/HectH9 may facilitate c-Myc-dependent transcription by ubiquitylating this transcriptional factor. Taken together, these studies [64,135] demonstrate that ARF-BP1/HectH9 serves as another node of convergence of p53 and c-Myc and another example of how the yin-yang forces of the cell are balanced through ubiquitylation regulation. The fulcrum supporting this balance is the tight regulation of ARF. Disruption of this network could lead to uncontrolled cell growth and consequent tumorigenesis (see Implications of p53 and c-Myc Ubiquitin Ligases in Tumorigenesis section for further discussion).

Nucleolar Proteins Regulate Ubiquitylation of Both p53 and c-Myc

In addition to ARF [166,168,170,178,179], there are other nucleolar proteins that have also been shown to regulate p53 and c-Myc. These proteins appear to sense a type of stress called ribosomal stress. Ribosomal stress is often caused by external and internal signals or chemicals that interfere with rRNA synthesis, rRNA processing, and ribosome assembly. This type of stress has been shown to activate p53 as well [180–183]. For example, overexpression of dominant-negative mutants of Bop1, a nucleolar protein critical for rRNA processing and ribosome assembly [180], inhibits 28_S_ and 5.8_S_ rRNA formation and causes a defect in ribosome assembly in NIH3T3 fibroblast cells. Consistent with this result, deleting the gene encoding the S6 protein, a component of the 40_S_ ribosomal subunit, may disrupt ribosomal assembly in T lymphocytes [184,185], causing ribosomal stress. Consequently, these cells undergo p53-dependent G1 cell cycle arrest [181,182,184]. In addition, a low dose of actinomycin D, which specifically inhibits RNA polymerase I, can stall rRNA synthesis and ribosome assembly. By doing so, this anticancer drug stimulates p53 activity without triggering N-terminal phosphorylation of p53 [183,186]. Furthermore, ARF directly inhibits rRNA processing, which may also generate ribosomal stress, thus contributing to p53 activation, in addition to its role in regulating the MDM2-p53 and ARF-BP1/HectH9-p53 pathways, as discussed above. These studies support the ribosomal stress-p53 activation pathway. However, the molecular mechanism underlying this pathway has been unknown until recent studies, including ours, revealed several nucleolar proteins that may participate in this pathway.

These nucleolar proteins include the ribosomal proteins L11, L23, and L5 [187–191]. Normally, these L proteins are assembled with rRNA and other ribosomal proteins into the 60_S_ large subunit of the ribosome in the nucleolus and are then exported to the rough endoplasmic reticulum for protein translation, together with the 40_S_ small subunit. In response to ribosomal stress, such as serum starvation or inhibition of RNA polymerase I activity by actinomycin D, L11, L23, and L5 are released from the nucleolus to associate directly with MDM2, mostly in the nucleoplasm [187–189,192]. By doing so, these ribosomal proteins can inhibit MDM2-mediated p53 ubiquitylation, increasing p53 level and activity in human cells. As a result, the cells undergo p53-dependent G1 arrest [187–192]. Despite these discoveries, little is known about the mechanism underlying the regulation of MDM2 E3 ubiquitin ligase activity by these L proteins. Some clues suggest that the L proteins may interfere with MDM2's ubiquitin ligase activity by interacting with the central acidic domain of this protein [187–189,191] because it has been shown that this acidic domain contributes to MDM2-mediated p53 degradation [22–25]. Surprisingly, not all of these L proteins appear to use the same mechanism; our recent studies suggest that only L23 and L5 appear to suppress MDM2 autoubiquitylation in cells [245]. L11 seems to use a postubiquitylation mechanism [245] similar to that used by ARF [193]. Regardless of these remaining issues, it is conceivable that the L proteins also play a role in the ribosomal stress-p53 signaling pathway, besides their essential function during protein translation.

In addition, another nucleolar protein, called B23 or nucleophosmin, which is ubiquitously expressed in all cells and has been implicated in rRNA processing, ribosomal protein assembly, and transport [194,195], also activates p53 [196,197]. Similar to the L proteins, B23 interacts directly with MDM2 and inhibits MDM2-mediated p53 ubiquitylation and degradation in response to UV [196], resulting in p53-dependent cell growth arrest. Furthermore, it was found that the normal nucleolar structure was disrupted in cells treated with 11 of 13 different agents that induced p53 stabilization [198]. Because all of these reagents can cause nuclear accumulation of B23 through unknown mechanisms [198,199], it has been proposed that mammalian cells may have evolved a sensing mechanism that can be activated when the nucleolus is disrupted (nucleolus stress) [198]. The tumor suppressor p53 is a downstream responder of this sensing system, as loss of this p53 response can result in unrestrained cellular proliferation [200,201]. This nucleolus stress-p53 pathway remains to be elucidated in parallel to the DNA-damaging p53 activation mechanism and is important for protecting cells from undergoing uncontrolled cell growth. It is possible that different nucleolar stress reagents may activate p53 through different nucleolar proteins. Recent proteomic analyses of the nucleolus have identified a number of novel nucleolar proteins that might be rRNA processing and ribosome assembly factors [202,203]. Thus, we speculate that more nucleolar proteins will be probably uncovered to regulate the MDM2-p53 pathway in the near future. Furthermore, in the interest of maintaining balance, the nucleolus is also a common territory of c-Myc.

The nucleolus is a workshop for ribosomal biogenesis, which is a highly controlled process requiring coordinated transcription by all three RNA polymerases (Pol) to ensure efficient and accurate production of ribosomes [204,205]. Several studies have acclaimed that c-Myc is a new and critical player in this process. In addition to regulating RNA Pol II-catalyzed transcription [206–209], c-Myc also enhances polymerase I-catalyzed rRNA synthesis [98–100] and polymerase III-mediated 5_S_ and tRNA transcription in the nucleolus [210]. Strikingly, these nucleolar activities of c-Myc are all regulated by ARF. ARF binds to c-Myc and inhibits c-Myc transactivation activity [178,179]. Thus, ARF is thought of as a feedback regulator of c-Myc in response to oncogenic stress (Figure 4). Not only c-Myc activity but also c-Myc stability is most likely monitored in the nucleolus. As mentioned in Regulation of the c-Myc Oncoprotein (Yang) by Multiple Ubiquitin Ligases section, the nucleolar Fbw7γ may mediate c-Myc ubiquitylation and degradation in the nucleolus [134].

Figure 4.

Regulation of p53 and c-Myc transcription factors by nucleolar proteins. Bars indicate inhibition; arrows denote the functional activation of c-Myc.

In summary, both p53 and c-Myc are associated with ribosomal biogenesis. Under unstressed conditions, c-Myc activity is required for driving normal ribosomal biogenesis in order for cells to grow and to proliferate. In response to ribosomal stress, nucleolar proteins, such as ARF, L11, L23, L5, or B23, are released from the nucleolus to crosstalk with MDM2 and to repress its activity. As a result, p53 is stabilized and activated to prevent cell growth and proliferation. Therefore, the coupling of ARF to proteasomal degradation and the stability of two major regulators of cellular homeostasis maintain the delicate balance of the cell.

Implications of p53 and c-Myc Ubiquitin Ligases in Tumorigenesis

Unbalanced regulation of p53 (yin) and c-Myc (yang) forces cells toward the path of oncogenesis. This notion is substantially supported not only by the fact that inactivation of p53, as well as activation of c-Myc, has been consistently demonstrated to lead to carcinogenesis [8,10,86,109] but also by the increasing volume of evidence showing that their aforementioned regulators are highly relevant to cancer formation. As discussed above, inactivation of ARF by deletion mutation and knockout also leads to tumor growth in certain tissues. Although it remains to be clarified if the ribosomal proteins L11, L5, and L23 may function as tumor suppressors, mutations of some ribosomal proteins have been linked to tumorigenesis in zebrafish [211]. The relevance of several E3 ubiquitin ligases in the p53 and c-Myc pathways to cancer is discussed below.

MDM2 is an Oncoprotein

The oncogenic activity of MDM2 is reflected through its capability to immortalize and to transform rat embryonic fibroblasts, in cooperation with Ras [212]. In addition, overexpression of MDM2 converts NIH 3T3 cells into tumor cells that can develop into xenografted tumors in mice [213]. Consistently, amplification and overexpression of MDM2 have been found in a variety of human tumors, particularly in soft tissue sarcomas, carcinomas, leukemias, lymphomas, and breast and lung cancers [214–219]. The tumorigenic potential of MDM2 is primarily attributed to its ability to inhibit the tumor-suppressor function of p53, as discussed above.

Fbw7 Is a Haploinsufficient Tumor Suppressor

Because SCF_Fbw7_ targets multiple oncoproteins, such as c-Myc [131–134], cyclin E [220–222], c-Jun [223,224], and Notch [225,226], for ubiquitylation and degradation, it acts as a tumor suppressor (reviewed in Minella and Clurman [152]). Indeed, Fbw7 is mutated in 8 of 51 (15.7%) cases of human endometrial carcinomas [227] and in 22 of 190 (11.6%) cases of colorectal cancers [228], as well as in several ovarian [221] and breast cancer [222] cell lines. Interestingly, the majority of mutations occur either at the F-box (Skp1-binding domain) or at WD40 repeats (substrate recognition domain) of Fbw7, highlighting the importance of these domains in tumorigenesis. In addition, the chromosome locus 4q32 containing the Fbw7 gene is deleted in over 31 % of human cancers [229]. Because homozygous deletion of this gene results in embryonic lethality, Fbw7 is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. This conclusion is further supported by a recent study showing that radiation-induced lymphomas from p53+/-, but not p53-/-, mice display frequent loss of heterozygosity and a 10% mutation rate in the Fbw7 gene. Furthermore, Fbw7 heterozygote mice are more susceptible to radiation-induced tumorigenesis, in comparison with either p53+/- or p53-/- mice [230]. Despite the fact that mutations of Fbw7 often coexist with elevated levels of total and phosphorylated cyclin E and that overexpression of cyclin E results in genomic instability [231] that correlates with cancer presentation and poor prognosis in murine and human [232–235] systems, it remains to be investigated whether c-Myc activation may have a direct contribution to the formation of human cancers due to loss of one copy of the Fbw7 gene.

Skp2 is an Oncoprotein

The oncogenic activity of Skp2 is highly associated with its role in controlling the turnover of another tumor suppressor p27kip1 [236,237], which inhibits Cdk2/cyclin E activity during the G1-phase to S-phase transition. Deletion of the p27Kip1 gene almost completely rescued the overreplicative phenotype of skp2 knockout mice [238], suggesting that p27Kip1 is a major target of Skp2. In addition, overexpression of Skp2 induces malignant phenotypes in transgenic mice [239,240]. Although it is still unaddressed whether c-Myc is also involved in the oncogenesis induced by Skp2, it is quite possible that c-Myc may play a part in Skp2-induced tumorigenesis.

The Possibility of ARF-BP1/HectH9 as an Oncoprotein In light of its role in suppressing p53 activity and in enhancing c-Myc activity, it can be predicted that ARF-BP1/HectH9 may act as an oncoprotein. In line with this hypothesis is the fact that this protein is overexpressed in 80% (16 of 20) of breast cancer cell lines [64], as well as in a large number of primary human tumors, including breast (43%), lung (46%), colon (52%), liver (18%), pancreatic (20%), and thyroid (9%) carcinomas [135]. The level of ARF-BP1/HectH9 is closely correlated with tumor progression, as its overexpression is detected in 33% (9 of 27) of adenomas and 49% (42 of 85) of adenocarcinomas, but not in the normal epithelium and in polyps [135]. However, more studies are critical to fully establish its role as an oncoprotein and to determine whether ARF-BP1/HectH9 can be used as a marker for cancer progression or whether its gene is amplified in human cancers.

Conclusion: The Balance Maintained

The molecular anatomy of the p53 and c-Myc pathways using biochemical, cell biologic, and genetic tools over the past decades has unraveled an overwhelmingly complex network that functionally bridges the two distinct transcription factors with opposing roles in controlling cell growth. In this network, ARF and ARF-BP1/HectH9 appear to play a key role as the fulcrum providing a sustained balance between the cell growth promoted by c-Myc and the cell growth suppression executed by p53. On one hand, ARF-BP1/HectH9 is activated to turn on c-Myc activity, but can also turn off p53 through ubiquitylation, although it is still unclear how this E3 ubiquitin ligase is activated (Figure 4). However, when c-Myc is aberrantly overactive, such as in response to Ras activation (Fig. 3), it induces ARF, which in turn represses c-Myc activity through crosstalk. Other than reducing c-Myc activity, ARF also could inactivate the c-Myc helper, ARF-BP1/HectH9. Additionally, ARF activates p53 by suppressing the E3 ligase activities of both Mdm2 and ARF-BP1/HectH9. As a result, the cell growth program is turned off. By doing so, ARF and p53 act as the yin force to prevent cells from undergoing uncontrolled growth and to suppress neoplasia provided by the yang of c-Myc. However, repeated perturbation of yin and yang through mechanisms such as inactivation of p53 and ARF, or activation of c-Myc, MDM2, or ARF-BP/HectH9, would gradually lead to cell transformation and oncogenesis. For instance, two N-terminal mutation alleles of c-Myc identified in human Burkitt's lymphoma fail to bind to the BH3-only protein Bim and to effectively inhibit Bcl2 and thus lose their ability to induce apoptosis but still promote cell proliferation [151]. Because of this failure, these c-Myc mutant alleles are able to evade the tumor suppression activity of p53, more efficiently promoting lymphomagenesis, regardless of their capability of inducing p53 level [151]. Thus, the interdependence and fluctuating balance between yin and yang are represented in cellular homeostasis by p53-c-Myc networks for the control of cell growth.

One ultimate benefit of identifying these positive and negative growth regulators and of elucidating their interplay in cell growth control is to divulge a broad spectrum of molecular targets that are potentially useful for cancer diagnosis and antitumor drug development. For example, the MDM2-p53 feedback loop has been used as a drug target [241–244]. ARF-BP1/HectH9, as well as others (as described in this review), may be a potential candidate for future pharmacological studies, once its individual role in tumorigenesis and its connections with specific tumors have been firmly established. Yet because most of these proteins reside in the nucleus or the nucleolus, it would be particularly challenging to deliver effective drugs against them. Nevertheless, continued dissection of how individual molecules act in maintaining the balance in cell growth control pathways for the larger purpose of cellular harmony and homeostasis will definitely lead to better and promising treatments for cancer in the future.

Footnotes

1

Tremendous progress has been made in the fields of p53 and c-Myc. Unfortunately, this review could not possibly cover all the aspects and new discoveries related to this network due to the focus of this review on ubiquitylation and its limited scope. We apologize for not being able to cite all of the publications in these fields. We hope that our review could at least touch or depict one portion of the “big elephant”—the molecular mechanisms of tumorigenesis.

2

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants (CA095441, CA93614, and CA079721)to Hua Lu.

References

- 1.Hahn WC, Weinberg RA. Modelling the molecular circuitry of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:331–341. doi: 10.1038/nrc795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olive KP, Tuveson DA, Ruhe ZC, Yin B, Willis NA, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Jacks T. Mutant p53 gain of function in two mouse models of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cell. 2004;119:847–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lang GA, Iwakuma T, Suh YA, Liu G, Rao VA, Parant JM, Valentin Vega YA, Terzian T, Caldwell LC, Strong LC, et al. Gain of function of a p53 hot spot mutation in a mouse model of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cell. 2004;119:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srivastava S, Zou ZQ, Pirollo K, Blattner W, Chang EH. Germ-line transmission of a mutated p53 gene in a cancer-prone family with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Nature. 1990;348:747–749. doi: 10.1038/348747a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malkin D, Li FP, Strong LC, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Nelson CE, Kim DH, Kassel J, Gryka MA, Bischoff FZ, Tainsky MA, et al. Germ line p53 mutations in a familial syndrome of breast cancer, sarcomas, and other neoplasms. Science. 1990;250:1233–1238. doi: 10.1126/science.1978757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Harris CC. p53 mutations in human cancers. Science. 1991;253:49–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1905840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soussi T, Dehouche K, Beroud C. p53 website and analysis of p53 gene mutations in human cancer: forging a link between epidemiology and carcinogenesis. Hum Mutat. 2000;15:105–113. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200001)15:1<105::AID-HUMU19>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vousden KH. Activation of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1602:47–59. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(02)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oren M. Decision making by p53: life, death and cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:431–442. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prives C. Signaling to p53: breaking the MDM2-p53 circuit. Cell. 1998;95:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81774-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumont P, Leu JI, Della Pietra AC, III, George DL, Murphy M. The codon 72 polymorphic variants of p53 have markedly different apoptotic potential. Nat Genet. 2003;33:357–365. doi: 10.1038/ng1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mihara M, Erster S, Zaika A, Petrenko O, Chittenden T, Pancoska P, Moll UM. p53 has a direct apoptogenic role at the mitochondria. Mol Cell. 2003;11:577–590. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chipuk JE, Kuwana T, Bouchier-Hayes L, Droin NM, Newmeyer DD, Schuler M, Green DR. Direct activation of Bax by p53 mediates mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Science. 2004;303:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1092734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford JM. Regulation of DNA damage recognition and nucleotide excision repair: another role for p53. Mutat Res. 2005;577:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pickart CM. Ubiquitin in chains. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:544–548. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01681-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flick K, Ouni I, Wohlschlegel JA, Capati C, McDonald WH, Yates JR, Kaiser P. Proteolysis-independent regulation of the transcription factor Met4 by a single Lys 48-linked ubiquitin chain. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:634–641. doi: 10.1038/ncb1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cahilly-Snyder L, Yang-Feng T, Francke U, George DL. Molecular analysis and chromosomal mapping of amplified genes isolated from a transformed mouse 3T3 cell line. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1987;13:235–244. doi: 10.1007/BF01535205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwakuma T, Lozano G. MDM2, an introduction. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:993–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J, Marechal V, Levine AJ. Mapping of the p53 and mdm-2 interaction domains. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4107–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliner JD, Pietenpol JA, Thiagalingam S, Gyuris J, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Oncoprotein MDM2 conceals the activation domain of tumour suppressor p53. Nature. 1993;362:857–860. doi: 10.1038/362857a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawai H, Wiederschain D, Yuan ZM. Critical contribution of the MDM2 acidic domain to p53 ubiquitination. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4939–4947. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.4939-4947.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meulmeester E, Frenk R, Stad R, de Graaf P, Marine JC, Vousden KH, Jochemsen AG. Critical role for a central part of Mdm2 in the ubiquitylation of p53. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4929–4938. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.4929-4938.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Argentini M, Barboule N, Wasylyk B. The contribution of the acidic domain of MDM2 to p53 and MDM2 stability. Oncogene. 2001;20:1267–1275. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu Q, Yao J, Wani G, Wani MA, Wani AA. Mdm2 mutant defective in binding p300 promotes ubiquitination but not degradation of p53: evidence for the role of p300 in integrating ubiquitination and proteolysis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29695–29701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102634200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fang S, Jensen JP, Ludwig RL, Vousden KH, Weissman AM. Mdm2 is a RING finger-dependent ubiquitin protein ligase for itself and p53. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8945–8951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freedman DA, Levine AJ. Nuclear export is required for degradation of endogenous p53 by MDM2 and human papillomavirus E6. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7288–7293. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth J, Dobbelstein M, Freedman DA, Shenk T, Levine AJ. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the hdm2 oncoprotein regulates the levels of the p53 protein via a pathway used by the human immunodeficiency virus rev protein. EMBO J. 1998;17:554–564. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lohrum MA, Ashcroft M, Kubbutat MH, Vousden KH. Contribution of two independent MDM2-binding domains in p14(ARF) to p53 stabilization. Curr Biol. 2000;10:539–542. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Momand J, Zambetti GP, Olson DC, George D, Levine AJ. The mdm-2 oncogene product forms a complex with the p53 protein and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation. Cell. 1992;69:1237–1245. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90644-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu H, Lin J, Chen J, Levine AJ. The regulation of p53-mediated transcription and the roles of hTAFII31 and mdm-2. Harvey Lect. 1994;90:81–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Honda R, Tanaka H, Yasuda H. Oncoprotein MDM2 is a ubiquitin ligase E3 for tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Lett. 1997;420:25–27. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyd SD, Tsai KY, Jacks T. An intact HDM2 RING-finger domain is required for nuclear exclusion of p53. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:563–568. doi: 10.1038/35023500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geyer RK, Yu ZK, Maki CG. The MDM2 RING-finger domain is required to promote p53 nuclear export. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:569–573. doi: 10.1038/35023507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lohrum MA, Woods DB, Ludwig RL, Balint E, Vousden KH. C-terminal ubiquitination of p53 contributes to nuclear export. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:8521–8532. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.24.8521-8532.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tao W, Levine AJ. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of oncoprotein Hdm2 is required for Hdm2-mediated degradation of p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3077–3080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Minsky N, Oren M. The RING domain of Mdm2 mediates histone ubiquitylation and transcriptional repression. Mol Cell. 2004;16:631–639. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin Y, Zeng SX, Dai MS, Yang XJ, Lu H. MDM2 inhibits PCAF (p300/CREB-binding protein-associated factor)-mediated p53 acetylation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30838–30843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204078200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perry ME, Piette J, Zawadzki JA, Harvey D, Levine AJ. The mdm-2 gene is induced in response to UV light in a p53-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11623–11627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barak Y, Juven T, Haffner R, Oren M. mdm2 expression is induced by wild type p53 activity. EMBO J. 1993;12:461–468. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05678.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Picksley SM, Lane DP. The p53-mdm2 autoregulatory feedback loop: a paradigm for the regulation of growth control by p53? Bioessays. 1993;15:689–690. doi: 10.1002/bies.950151008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu X, Bayle JH, Olson D, Levine AJ. The p53-mdm-2 autoregulatory feedback loop. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1126–1132. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7a.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones SN, Roe AE, Donehower LA, Bradley A. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm2-deficient mice by absence of p53. Nature. 1995;378:206–208. doi: 10.1038/378206a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montes de Oca Luna R, Wagner DS, Lozano G. Rescue of early embryonic lethality in mdm2-deficient mice by deletion of p53. Nature. 1995;378:203–206. doi: 10.1038/378203a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stommel JM, Wahl GM. Accelerated MDM2 auto-degradation induced by DNA-damage kinases is required for p53 activation. EMBO J. 2004;23:1547–1556. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shirangi TR, Zaika A, Moll UM. Nuclear degradation of p53 occurs during down-regulation of the p53 response after DNA damage. FASEB J. 2002;16:420–422. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0617fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joseph TW, Zaika A, Moll UM. Nuclear and cytoplasmic degradation of endogenous p53 and HDM2 occurs during down-regulation of the p53 response after multiple types of DNA damage. FASEB J. 2003;17:1622–1630. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0931com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodriguez MS, Desterro JM, Lain S, Lane DP, Hay RT. Multiple C-terminal lysine residues target p53 for ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8458–8467. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.22.8458-8467.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grossman SR, Deato ME, Brignone C, Chan HM, Kung AL, Tagami H, Nakatani Y, Livingston DM. Polyubiquitination of p53 by a ubiquitin ligase activity of p300. Science. 2003;300:342–344. doi: 10.1126/science.1080386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grossman SR, Perez M, Kung AL, Joseph M, Mansur C, Xiao ZX, Kumar S, Howley PM, Livingston DM. p300/MDM2 complexes participate in MDM2-mediated p53 degradation. Mol Cell. 1998;2:405–415. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shvarts A, Steegenga WT, Riteco N, van Laar T, Dekker P, Bazuine M, van Ham RC, van der Houven van Oordt W, Hateboer G, van der Eb AJ, et al. MDMX: a novel p53-binding protein with some functional properties of MDM2. EMBO J. 1996;15:5349–5357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Linares LK, Hengstermann A, Ciechanover A, Muller S, Scheffner M. HdmX stimulates Hdm2-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12009–12014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2030930100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Migliorini D, Denchi EL, Danovi D, Jochemsen A, Capillo M, Gobbi A, Helin K, Pelicci PG, Marine JC. Mdm4 (Mdmx) regulates p53-induced growth arrest and neuronal cell death during early embryonic mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5527–5538. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.15.5527-5538.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parant J, Chavez-Reyes A, Little NA, Yan W, Reinke V, Jochemsen AG, Lozano G. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm4-null mice by loss of Trp53 suggests a nonoverlapping pathway with MDM2 to regulate p53. Nat Genet. 2001;29:92–95. doi: 10.1038/ng714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pan Y, Chen J. MDM2 promotes ubiquitination and degradation of MDMX. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5113–5121. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5113-5121.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Graaf P, Little NA, Ramos YF, Meulmeester E, Letteboer SJ, Jochemsen AG. Hdmx protein stability is regulated by the ubiquitin ligase activity of Mdm2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38315–38324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brignone C, Bradley KE, Kisselev AF, Grossman SR. A postubiquitination role for MDM2 and hHR23A in the p53 degradation pathway. Oncogene. 2004;23:4121–4129. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leng RP, Lin Y, Ma W, Wu H, Lemmers B, Chung S, Parant JM, Lozano G, Hakem R, Benchimol S. Pirh2, a p53-induced ubiquitin-protein ligase, promotes p53 degradation. Cell. 2003;112:779–791. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dornan D, Wertz I, Shimizu H, Arnott D, Frantz GD, Dowd P, O'Rourke K, Koeppen H, Dixit VM. The ubiquitin ligase COP1 is a critical negative regulator of p53. Nature. 2004;429:86–92. doi: 10.1038/nature02514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scheffner M, Huibregtse JM, Vierstra RD, Howley PM. The HPV-16 E6 and E6-AP complex functions as a ubiquitin-protein ligase in the ubiquitination of p53. Cell. 1993;75:495–505. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dyson N, Howley PM, Munger K, Harlow E. The human papilloma virus-16 E7 oncoprotein is able to bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Science. 1989;243:934–937. doi: 10.1126/science.2537532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Werness BA, Levine AJ, Howley PM. Association of human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 E6 proteins with p53. Science. 1990;248:76–79. doi: 10.1126/science.2157286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rolfe M, Beer-Romero P, Glass S, Eckstein J, Berdo I, Theodoras A, Pagano M, Draetta G. Reconstitution of p53-ubiquitinylation reactions from purified components: the role of human ubiquitinconjugating enzyme UBC4 and E6-associated protein (E6AP) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3264–3268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen D, Kon N, Li M, Zhang W, Qin J, Gu W. ARF-BP1/Mule is a critical mediator of the ARF tumor suppressor. Cell. 2005;121:1071–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Esser C, Scheffner M, Hohfeld J. The chaperone-associated ubiquitin ligase CHIP is able to target p53 for proteasomal degradation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27443–27448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501574200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bargonetti J, Manfredi JJ, Chen X, Marshak DR, Prives C. A proteolytic fragment from the central region of p53 has marked sequence-specific DNA-binding activity when generated from wild-type but not from oncogenic mutant p53 protein. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2565–2574. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hinds PW, Finlay CA, Quartin RS, Baker SJ, Fearon ER, Vogelstein B, Levine AJ. Mutant p53 DNA clones from human colon carcinomas cooperatewith ras in transforming primary rat cells: a comparison of the “hot spot” mutant phenotypes. Cell Growth Differ. 1990;1:571–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gannon JV, Greaves R, Iggo R, Lane DP. Activating mutations in p53 produce a common conformational effect. A monoclonal antibody specific for the mutant form. EMBO J. 1990;9:1595–1602. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08279.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rainwater R, Parks D, Anderson ME, Tegtmeyer P, Mann K. Role of cysteine residues in regulation of p53 function. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3892–3903. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stephen CW, Lane DP. Mutant conformation of p53. Precise epitope mapping using a filamentous phage epitope library. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:577–583. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90386-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Deshaies RJ. SCF and Cullin/Ring H2-based ubiquitin ligases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:435–467. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Querido E, Blanchette P, Yan Q, Kamura T, Morrison M, Boivin D, Kaelin WG, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, Branton PE. Degradation of p53 by adenovirus E4orf6 and E1B55K proteins occurs via a novel mechanism involving a Cullin-containing complex. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3104–3117. doi: 10.1101/gad.926401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Blanchette P, Cheng CY, Yan Q, Ketner G, Ornelles DA, Dobner T, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, Branton PE. Both BC-box motifs of adenovirus protein E4orf6 are required to efficiently assemble an E3 ligase complex that degrades p53. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9619–9629. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9619-9629.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Querido E, Morrison MR, Chu-Pham-Dang H, Thirlwell SW, Boivin D, Branton PE. Identification of three functions of the adenovirus e4orf6 protein that mediate p53 degradation by the E4orf6-E1B55K complex. J Virol. 2001;75:699–709. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.699-709.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Andrews P, He YJ, Xiong Y. Cytoplasmic localized ubiquitin ligase cullin 7 binds to p53 and promotes cell growth by antagonizing p53 function. Oncogene. 2006;25 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209490. March 20 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li M, Chen D, Shiloh A, Luo J, Nikolaev AY, Qin J, Gu W. Deubiquitination of p53 by HAUSP is an important pathway for p53 stabilization. Nature. 2002;416:648–653. doi: 10.1038/nature737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cummins JM, Rago C, Kohli M, Kinzler KW, Lengauer C, Vogelstein B. Tumour suppression: disruption of HAUSP gene stabilizes p53. Nature. 2004;428:486–487. doi: 10.1038/nature02501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Meulmeester E, Maurice MM, Boutell C, Teunisse AF, Ovaa H, Abraham TE, Dirks RW, Jochemsen AG. Loss of HAUSP-mediated deubiquitination contributes to DNA damage-induced destabilization of Hdmx and Hdm2. Mol Cell. 2005;18:565–576. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li M, Brooks CL, Kon N, Gu W. A dynamic role of HAUSP in the p53-Mdm2 pathway. Mol Cell. 2004;13:879–886. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Appella E, Anderson CW. Post-translational modifications and activation of p53 by genotoxic stresses. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:2764–2772. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meek DW, Knippschild U. Posttranslational modification of MDM2. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:1017–1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jin Y, Dai MS, Lu SZ, Xu Y, Luo Z, Zhao Y, Lu H. 14-3-3gamma binds to MDMX that is phosphorylated by UV-activated Chk1, resulting in p53 activation. EMBO J. 2006;25:1207–1218. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.LeBron C, Chen L, Gilkes DM, Chen J. Regulation of MDMX nuclear import and degradation by Chk2 and 14-3-3. EMBO J. 2006;25:1196–1206. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Okamoto K, Kashima K, Pereg Y, Ishida M, Yamazaki S, Nota A, Teunisse A, Migliorini D, Kitabayashi I, Marine JC, et al. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of MdmX at serine 367 activates p53 by targeting MdmX for Mdm2-dependent degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9608–9620. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9608-9620.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eisenman RN. Deconstructing myc. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2023–2030. doi: 10.1101/gad928101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pelengaris S, Khan M, Evan G. c-MYC: more than just a matter of life and death. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:764–776. doi: 10.1038/nrc904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sakamuro D, Prendergast GC. New Myc-interacting proteins: a second Myc network emerges. Oncogene. 1999;18:2942–2954. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Amati B, Dalton S, Brooks MW, Littlewood TD, Evan GI, Land H. Transcriptional activation by the human c-Myc oncoprotein in yeast requires interaction with Max. Nature. 1992;359:423–426. doi: 10.1038/359423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Adhikary S, Eilers M. Transcriptional regulation and transformation by Myc proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:635–645. doi: 10.1038/nrm1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Luscher B, Larsson LG. The basic region/helix-loop-helix/leucine zipper domain of Myc proto-oncoproteins: function and regulation. Oncogene. 1999;18:2955–2966. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ayer DE, Kretzner L, Eisenman RN. Mad: a heterodimeric partner for Max that antagonizes Myc transcriptional activity. Cell. 1993;72:211–222. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90661-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ayer DE, Eisenman RN. A switch from Myc:Maxto Mad:Max heterocomplexes accompanies monocyte/macrophage differentiation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2110–2119. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]