An Interactive Resource to Probe Genetic Diversity and Estimated Ancestry in Cancer Cell Lines (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2020 Apr 1.

Abstract

Recent work points to a lack of diversity in genomics studies from genome-wide association studies to somatic (tumor) genome analyses. Yet, population-specific genetic variation has been shown to contribute to health disparities in cancer risk and outcomes. Immortalized cancer cell lines are widely used in cancer research, from mechanistic studies to drug screening. Larger collections of cancer cell lines better represent the genomic heterogeneity found in primary tumors. Yet, the genetic ancestral origin of cancer cell lines is rarely acknowledged and often unknown. Using genome-wide genotyping data from 1,393 cancer cell lines from the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) and Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE), we estimated the genetic ancestral origin for each cell line. Our data indicate that cancer cell line collections are not representative of the diverse ancestry and admixture characterizing human populations. We discuss the implications of genetic ancestry and diversity of cellular models for cancer research and present an interactive tool, Estimated Cell Line Ancestry (ECLA), where ancestry can be visualized with reference populations of the 1000 Genomes project. Cancer researchers can use this resource to identify cell line models for their studies by taking ancestral origins into consideration.

The diverse origins of cancer health disparities

In the US the incidence of certain cancers varies significantly by race and ethnicity, including some of the most common cancers such as breast, colorectal and prostate cancers (1). Wide disparities have also been reported in treatment outcomes and survival (1). As a first step towards addressing disparities, the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993 resulted in the establishment of the Office of Research on Minority Health, with the mandate to conduct and support research that would be inclusive of minority populations (2). Continued efforts, including the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), sought to address cancer care disparities (3). Despite these efforts, health disparities still exist (1) and exclusion of minority populations from health-related studies remains a concern (4–7).

Cancer disparities result in differences in risk and outcomes that are likely to be the result of a complex interplay between genetics (8,9) socioeconomic (10–12), environmental factors (13) and even receipt of treatment (14). The American Society of Clinical Oncology has proposed strategies for reducing disparities through insurance reform, access to care, quality of care, prevention and wellness, research on health care disparities, and diversity in the health care workforce (3). While these strategies will reduce disparities, they do not address biological factors. Evidence is accumulating that the cancer discoveries driving progress in prevention, screening strategies and treatment derive disproportionately from populations of European descent. This review focuses on research indicating variation in biological and molecular aspects of cancers in populations.

Genetic-based studies have identified differences among ancestral populations in tumor biology and clinical response (15). However, closely associated with these findings are the rather imprecise social terms of ethnicity and race (16,17). In this paper, we have followed the convention of referring to genetic ancestry, and only secondarily comparing to self-reported race and/or ethnicity (18,19). However, this area remains controversial (20). The use of genetic ancestry as a basis for scientific studies may help understand disease prevention and intervention (21,22) although this is only one factor among many (23). Assessing the role of ancestry-associated genetic variations in disease etiology is further complicated by the recent admixture that characterizes various populations of the world (24). Hence, an individual’s ancestry can be described by quantifying the proportion of the genome derived from each contributing population (global ancestry). Heterogeneity is also observed locally in the genome, as variability is observed in the ancestral origins of any particular segment of chromosomes (local ancestry) (25). Ultimately, genetics plays a role in the biological characteristics of a cancer in the form of both germline variation and somatic alterations. Further research is needed to determine the extent to which genetic differences align with ancestral genetic changes (26).

Limited cancer research in diverse populations

Cancer Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) have advanced our understanding of the inherited genetic factors that influence cancer risk. Despite recent progress, however, this understanding is mostly from data obtained from populations of European ancestry (27–29). Specifically, cancer GWAS have pinpointed over 700 risk loci (29) but remarkably, 80% were first discovered in European ancestry populations, approximately 15% in East Asians, and less than 1% in African and Latin American populations (29). Population structure which may result from ancestry variations in a cohort have been regarded as a confounder that can lead to spurious signals or hide true associations, (30–32), and it is only recently that multiethnic cohorts have emerged as a solution to identify risk loci in more diverse populations. Despite the challenges associated with the use of multiethnic cohorts such as admixture, genetic heterogeneity, variations in the linkage disequilibrium structure around causative variants, and imputation (27), there is a demonstrated benefit to adopt a more inclusive approach. Evidence is accumulating that relying solely on populations of European descent results in an incomplete or inaccurate representation of the genetic susceptibility to cancers (27). For example, replication of risk loci found in European populations through GWAS in multiethnic cohorts has revealed that risk factors may differ in their nature and magnitude of effect (33). The recent increases in the inclusion of non-European populations in GWAS has been mostly attributed to an increase in representation of Asian populations and collectively, African, Hispanics/Latinos, and native or indigenous populations represented less than 4% of the 35 million samples included in 2,500 studies reported in the GWAS Catalog (34).

Such lack of diversity has also been observed in areas of cancer research that will have direct consequences on treatment strategies of cancer patients. For instance, the identification of actionable driver somatic (tumor) mutations has been the basis of the development of targeted cancer therapies and identification of molecular tumor subtypes. In the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) exome sequencing dataset it was estimated that recurrent somatic mutations with 5% frequency would be detectable in whites, but not in populations of any other ethnic origin due to the paucity of samples from those populations (35). With only 33% of all samples identified as non-white (35), the TCGA dataset provides limited opportunities to study the relationship between disparities associated with race and cancer genomes (36). Cancer-related clinical trials also remain limited in ethnic and racial composition, limiting the applicability of trial findings (4–6,37). In 2014, less than 2% of the NCI’s clinical trials focused on non-European populations and only 20% of the randomized control studies published in higher tier journals analyzed data by race and ethnicity (7). Despite significant advances in precision medicine, we risk implementing a standard of care for only a limited segment of the population without appropriate inclusion of all groups in this type of research (38). We note that this paper addresses the use of genetic ancestry within cell line studies and is not a comprehensive review of ancestry-related contributions to health disparities; more comprehensive reviews of this topic can be found in, for example (15,39–42). To illustrate the research that indicates ancestral-based disparities exist related to cancer risk, tumor biology, therapeutic options or outcomes we have focused on the example of breast cancer below.

Ancestral-related health disparities in cancer: breast cancer

The 6q25 breast cancer risk locus clearly illustrates the variability of risk variants across populations. A GWAS of Chinese women identified rs2046210 at 6q25.1 (centromeric to ESR1, which codes for estrogen receptor alpha) associated with breast cancer risk and validated the association in an independent European ancestry cohort (43). Further replication confirmed the finding among Chinese, Japanese and European-descent American women, but not among African American women (44). Other studies have similarly failed to identify this association in African American women (45–48). In an African American replication study, only 27% of the known GWAS hits reached statistical significance, an observation that was partly explained by differences in linkage disequilibrium architecture around the causative variants as well as statistical power (49). Interestingly, a Latina breast cancer GWAS identified a protective variant of Indigenous American origin at the 6q25 locus, which acts independently of the previously known risk variants at this locus (50). Thus variants associated with risk may not validate in other populations, or even change the direction of risk association (33). Importantly, polygenic risk scores for stratifying women based on their inherited risk of developing breast cancer, which have been developed using data derived largely from European population GWAS, perform poorly in African-American populations as a consequence of inverse directionality of 30–40% of the susceptibility loci (33).

The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, susceptibility genes for hereditary breast cancer, also illustrate the impact of ancestral heterogeneity (51,52). In a study of 4,835 Hispanic/Latino breast cancer individuals from 13 countries in Latin America, the Caribbean; and Hispanic/Latino individuals in the United States (52), different frequencies of BRCA1_and BRCA2 variants were observed. The authors report that in the Bahamas, it was estimated that 27.1 % of breast cancer cases had_BRCA pathogenic variants compared to other regions (typically 1–5% BRCA variants observed) (52). Further, BRCA1 variant p.A1708E was observed in the top 10 most frequent pathogenic variants from Hispanic/Latino breast cancer individuals yet this variant is not reported among the top 20 most frequent BRCA1 variants (52). Higher frequencies of BRCA pathogenic variants have also been observed in young black women (53) and Hispanics in the Southwestern United States (54).

Triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) has been shown to be more frequent in women of West African ancestry (55). This has significant clinical relevance as TNBC tumors are aggressive and often have limited specific therapies available (56). Several studies have identified an increased proportion of basal-like breast cancers in populations of African ancestry (57–61). Increased frequency of TNBC has also been observed in the Hispanic/Latino population (62–68), American Indian/Alaska Native population (64), and women from the Indian subcontinent (69). Interestingly, Filipino women were least likely to have TNBC (69) suggesting a broad range of variability.

Transcriptional signatures of proliferation and_VEGF_-activated gene expression were significantly higher in African-American TNBC tumors compared to tumors from European Americans (60). Importantly, higher tumor vascularization in African-American patients may consequently suggest potential_VEGF_/angiogenesis-related therapeutic options for this population (60). A similar study identified that breast tumors from African-American women are more likely to present with TP53 mutations, less likely to be mutated at the_PIK3CA_ locus and show greater tumor heterogeneity, a pattern consistent with the aggressive behavior of tumors in African-Americans (61). Research has also suggested that the presence of breast cancer stem cells (as determined by_ALDH1_ expression) is also more prevalent in tumors from women of African ancestry compared to European/White-American populations (57–59).

The recent pan-TCGA cancer study of the immune landscape of cancer identified relationships between ancestry and immune response (70). PD-L1 expression was lower in tumors from African ancestral populations across most cancer types including breast and colorectal cancers. Estimated lymphocyte fractions were lower in Asian ancestry in uterine and bladder cancers (UCEC, BLCA). Based on these findings, the authors suggested the hypothesis that checkpoint inhibitors could demonstrate ancestry-related efficacy (70).

Cellular models in cancer research

In vitro cultures of immortalized cell lines isolated from tumors have been used as model systems in cancer for at least 65 years. Cell lines have been developed from a variety of cancers including lung (71,72), breast (73,74), and ovarian (75,76) cancer. The National Cancer Institute assembled a panel of 60 cell lines representing a number of cancers including leukemia and many solid tumor types (non-small-cell lung, colon, ovarian, renal, prostate, breast, melanoma, CNS) (77–79). However, in the era of precision medicine, 60 cell lines represents only a small number of the over 100 histologies of cancer (79). Some of the notable data panels include the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) (80), the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) (81), the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) (82,83), the Cancer Therapeutic Response Portal (CTRP) (84) and CMT1000 (85) (see Supplemental Table S1 for a detailed list). These efforts have greatly expanded the number of cell line models and the data on these models available for cancer research.

The development and availability of cell line panels was driven by varied interests in the research community, governmental agencies and pharmaceutical companies predominantly as a method for screening compounds for potential efficacy (86–88). At the very early stages of the drug development pipeline, drug toxicity and efficacy can be quickly assessed in collections of cell lines derived from various cancer types. The NCI-60 panel of cell lines led to many innovations including the measurements of compound activity (89), data analytics (90–92) and screening automation (86,93,94). The broad diversity of cell types in the NCI60 have led to large number of compounds screened, approximately 150,000 in 2010 (95). Cell line panel drug response has also been correlated using the wealth of molecular profiling tools available such as gene expression (96–99), genetics (85,100–102), proteomics (103–105), and others (92). In the Connectivity Map (106), 164 small molecules were used to perturb MCF7 (breast cancer), HL60 (leukemia), SKMEL5 (melanoma) and PC3 (prostate cancer). This was vastly expanded in (107) to 19,811 compounds and 9 cell lines. Cell line panels have also been used for radiation therapy modeling (108–111) and metabolite profiling (112). In fact, cell line panels have been used to compare the applicability of cell lines with tumors (113–115).

Although cancer cell lines represent a valuable cancer research model system, issues such as misidentification and cross-contamination of cell lines (116–120) have been reported. Moreover, cell lines represent immortalized cancer cells and are often viewed skeptically as representing in vivo tumor development (71,114,121–124). Recently, individual cell line genetic drift was shown in the breast cancer cell line MCF7 to result in highly disparate drug response in different laboratory isolates (125). Finally, concerns over adequate patient consent for creating cell lines have arisen most notably from HeLa cells (126–130).

Leveraging cell line models in Health Disparities Research

While the NCI-60 provides a well-characterized resource of cell line models, the personalized medicine era challenged the paradigm of a single representative for an entire disease category (131,132). A broader representation of cancer was introduced through larger cell line panels such as the CCLE, although as we demonstrate large gaps still remain. Compounding this under-representation in cell line models is the lack of diversity in large molecular studies (28,35). Thus the ability to adequately address precision medicine with respect to genetic ancestry is severely limited.

When a scientist chooses a cell line model considerations should include the disease (e.g. breast cancer), molecular classification (e.g. triple-negative breast cancer) and genetic ancestry (e.g. ancestral components of a relevant population) as well as on practical laboratory considerations. The underpinnings of cancer risk associated with different genomic loci in GWAS follow-up studies requires researchers to identify cancer as well as normal tissue cell lines that reflect the population in which the association was identified. Additionally, when drug response correlations with molecular information are considered, the variable of estimated genetic ancestry should be included. For the reasons described above, genetic ancestry can impact the aggressiveness of disease (as prostate cancer in AA men), type of disease (as TNBC breast cancer in Hispanic/Latinos) or response to therapy. Thus, having accurate cell line ancestry information available supports experimental conclusions relevant to the population studied but not necessarily applicable to other populations. Further, actively selecting cell line models reflective of a study population allows for directed conclusions and actions in this population from gene perturbation (knock-down) functional studies or drug treatment response/resistance experiments.

Several research studies have addressed these considerations. For example, in (133) the authors examined the ancestry of several commonly used prostate cancer cell lines (including 22Rv1, PC3, DU145). In a larger study, germline variants were examined in 993 cell lines compared to 265 drugs for associations with drug response (134). While not explicitly examining ancestry, this result clearly indicates that the genetic background of cells can impact drug response.

Ancestral composition of cancer cell line models

We have identified a lack of research aids for determining genetic diversity in existing cell line databases. As an aid to cancer researchers and to support disparities studies, we have estimated the genetic ancestral components in existing cell line databases. First, we identify genetic ancestral populations that do not currently have representative cell line models. Secondly, we provide the admixture of genetic populations such that representative models can be identified for populations being studied. Future scientific studies can benefit from using this information on admixture of estimated ancestry within the cell line models when evaluating in vitro molecular biology endpoints and therapeutic responses. We also expect this resource to guide future efforts to generate cell lines in specific cancers in which disparities have been identified.

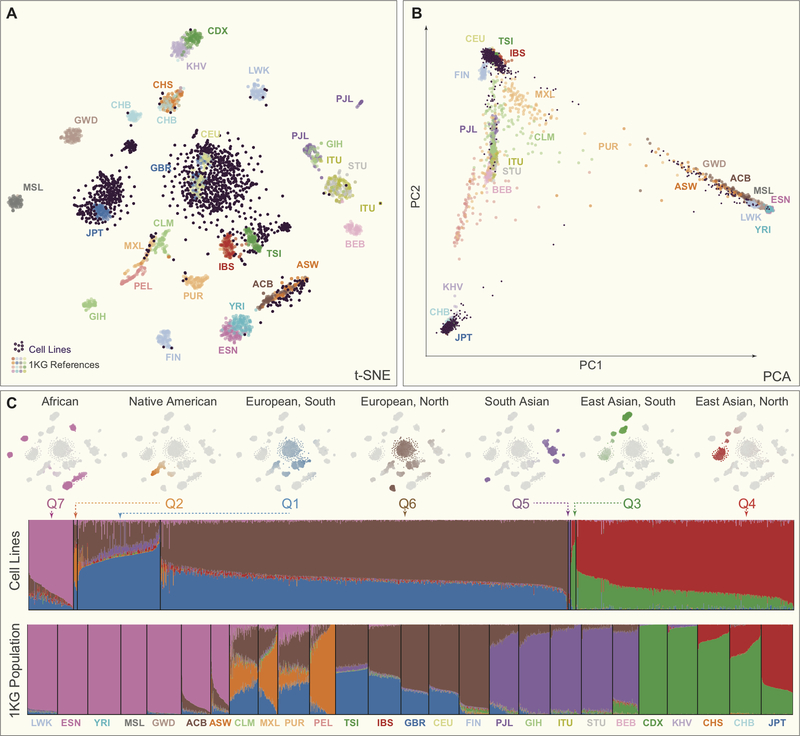

Using available genome-wide genotyping data (see Supplemental Material and Methods), we have determined the admixture proportions of 1,393 cancer cell lines (Supplemental Table S2) representing various cancer types (Supplemental Table S3) from the COSMIC and CCLE cell line panels using Admixture 1.3 (135). Excess genetic similarity was noted in 91 cell line pairs (Supplemental Table S4). Cell line Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) data was combined with population SNP data from The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium (24) (1kG, http://www.internationalgenome.org). This combined dataset was filtered (709,034 single nucleotide variants) and visualized using t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) (136) (Figure 1A) and principal components analysis (Figure 1B). Cell lines and 1kG populations were grouped based on the Infomap approach of detecting community structure from the adjacency graph of each sample’s 30 nearest neighbors (in Principal Component space) (137). Cell line associations were made based on most common 1kG population in the corresponding cluster: African (AFR), African American (AMR_AA), East Asian (EAS), European (EUR), Hispanic/Latino (AMR_HL) or South Asian (SAS). Admixture proportions for each cell line are presented in Supplemental Table S5.

Figure 1.

Estimated genetic ancestry of cell lines within key cell line panels with the 1000 Genomes Project (1kG) reference populations. (A) t-SNE plot of SNP data for cell line panels and 1kG reference populations where each reference population is labeled with the 1kG label (see Table S8 for abbreviation definitions) and the cell lines are labeled as small purple circles primarily clustered in the JPT (Japan), GBR (Great Britain) and CEU (Utah residents with Northern and Western European Ancestry) clusters indicating the majority of cell lines are limited to a few major genetic ancestral groups. (B) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plot of the cell line panels with the 1kG reference populations. (C) Panel of t-SNE plots showing specific estimated admixture component of ancestral populations estimated through an Admixture analysis with 1kG references and cell lines (7 populations, Q1-Q7 – see Table S5 for Admixture proportions). Shown are samples with majority admixture (Q1–7 color) for the specific population. Waterfall plots show the relative component fraction in each cell line and 1kG sample.

Comparing reported ethnicity to measured genetic ancestry

There is ample literature assessing the correspondence between genetic ancestry and self-identified race and ethnicity. While the former can be described and quantified through molecular genetic analysis, one’s perceived race and ethnicity is influenced by subjective variables. This perception stems from the complex interaction between physical characteristics and sociocultural factors. For more than half of the cell lines studied, self-reported ethnicity information could be obtained from one of the commonly used cell line databases Cellosaurus (138), COSMIC (139), Biosample (140), ATCC (https://www.atcc.org), among others. In the remaining 46.3%, information regarding the ethnicity of the individual from which it was derived could not be easily recovered. In 64 of the cell lines, the reported ethnicity did not correspond to the ancestry as measured by genetic markers. Cell lines reported as ‘African’ or ‘Black’ clustered with African American populations in 81.6% of the cases, emphasizing the ambiguity of the existing nomenclature. In fact, the proportion of the genome inferred to be of European origin in these cell lines averaged 18.32% (ranging from 0% to 95.09%). Another type of ambiguity concerns the cell line Hs 698.T labeled as originating from an ‘American Indian’, which clusters with populations of South Asia suggesting an origin in India rather than from a Native/Indigenous American individual. A total of 26 cell lines were reported as Caucasian but clustered genetically with other populations including African (n=2), African American (n=6), East Asian (n=1), Hispanic/Latinos (n=16), and South Asian (n=1). Interestingly, 89% of the cell lines identified as Hispanic/Latino from admixture patterns and clustering are reported as ‘Caucasian’. Several groups have reported a concordance between self- or observer-reported belonging to major racial/ethnic groups (141–143). However, these categories do not capture the inherent heterogeneity of admixed populations (144,145) (144,146,147). What appears as inconsistencies in self-report and genetic data may result from individuals having limited knowledge of their ancestral origins, or culturally identifying to an ethnic group that is not representative of one’s admixture proportions (18). Sociological, behavioral and biological factors that underlie race, ethnicity and ancestry are likely to interact (148). Consequently, from a biomedical research perspective, both self-reports of race/ethnicity group as well as genetically determined clustering and admixture are expected to be relevant in understanding disease susceptibility, and ultimately, the causes of health disparities (148) (18,149).

Distribution of genetic ancestry of cancer cell lines

Ancestry distribution of the cell lines is shown in Figure 1C and summarized in Supplemental Table S6. Across all cell lines, there was a clear bias in the representation of ancestry, with the majority of the cancer cell lines studied determined to be from European and East Asian origin (62.46% and 29.18%, respectively). All other reference populations were represented by less than 10% of the cell lines, with cell lines from African origin accounting for 5.26%, African American 0.86%, Hispanic/Latino 1.95% and South Asian 0.29%. These overall distributions were similar for subsets of cell lines representing the COSMIC and CCLE collections. However, the NCI60 panel stood out with the majority of the cell lines originating from individuals of European descent (over 94%).

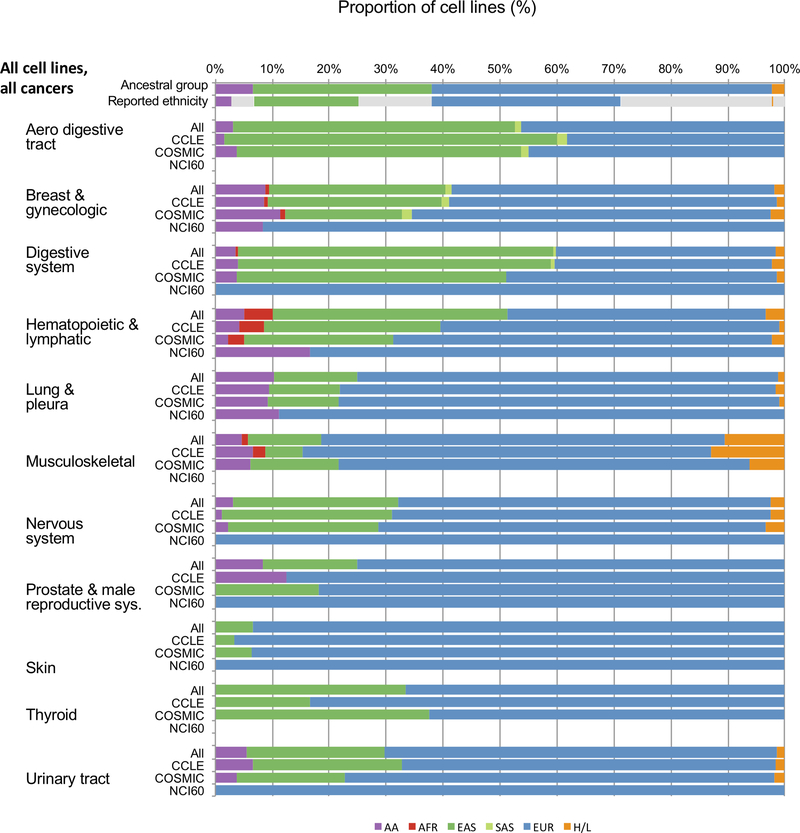

Proportions of cell lines associated with ancestral groups also varied across cancer types as detailed in Figure 2and Supplemental Table S7. While breast and lung cancer cell lines have the highest proportion of African descent cell lines (17.19% and 19.83% respectively), breast cancer had the lowest proportion of cell lines of Asian origin (6.25%). Below we describe several significant limitations by cancer types known to exhibit disparities.

Figure 2.

Stacked barplots of the proportion of cell lines within population by disease type. For each annotated disease type, the cell lines are summarized by cell line panel. Each bar represents the proportion of cells within the group with the majority admixture belonging to one of 6 groups (AA: African American, AFR: African, EAS: East Asian, EUR: European, H/L: Hispanic/Latino, SAS: South Asian). The results clearly indicate the overwhelming proportion of European-ancestry cell lines within the panels.

In prostate cancer, risk alleles at the 17q21 susceptibility locus have been shown to be rare in European and Asian populations but may contribute to up to 10% of the prostate cancer risk in men of African descent (150). In a large multi-ethnic replication study of prostate cancer risk GWAS hits, the magnitude of the association of known risk loci also varied substantially across cohorts of different ethnicities (151). Novel signals unique to men of African ancestry were recently identified on chromosomes 13q34 and 22q12, further supporting the contribution of population-specific variants to prostate cancer risk (152). Recent work indicates that beyond inherited risk variants, somatic driver mutations also differ in the African population compared to European-derived tumors (153). African American men are diagnosed with prostate cancer at younger age, have different treatment profiles, and have a higher risk of prostate cancer specific mortality even after adjusting for other factors (154). Ten prostate cell lines (seven carcinoma, one hyperplasia, two normal) are reported in CCLE and NCI-60. Despite widely acknowledged differences in the incidence and severity of prostate cancer in men of African descent, African ancestral genetic factors are represented in only 1 out of 10 cell lines (Q7 > 5%). This single cell line was MDAPCA2B, consisting of an estimated 90% African component (Q7=90% AFR/AMR-AA). Most cell lines have majority European (Q1+Q6) ancestry component. Interestingly, BPH-1, while reported as “Japanese”, has a European component of 95%, and an Asian component of 4%.

Cell lines of East Asian origin were the vast majority of cancers of the stomach (86.05%). This might reflect the higher incidence of these cancers in Asian populations. However, the increased burden of gastric cancer in Latin America (155,156) suggests that better representation outside of East Asian origin will be important.

Asian/Pacific Islanders men and women experience a 70% and 95% higher incidence rate of liver cancer, respectively, than European American men and women. Hispanic men and women have a similarly elevated incidence of liver cancers (157). Liver cancer cell lines appear to be more representative when considering Asian ancestry: of the 27 listed cell lines, 16 have a reported ethnicity consistent with Asian ancestry. However, we note that 1000 Genomes does not include Pacific Islander populations, and so we are currently unable to distinguish this ancestral component. Twenty-two of the 27 cell lines have East Asian (Q3+Q4) components of > 80%. Two cell lines have African (Q7) components >70%. However, only two cell lines have Native American (Q2) components >5% (C3A, HEPG2).

Lung cancer is highly prevalent in Hispanic/Latino (HL) men and women, and is the leading cause of cancer death in HL men (158). Recent studies have shown a difference in mutation rates prevalence among common oncogenic driver genes:EGFR is more highly mutated in Asian (159) and HL (160,161), whereas_KRAS_ is more highly mutated in Non-Hispanic Whites (NHW) (160). This difference may have a direct impact on treatment and outcomes, as EGFR and_KRAS_ mutation status affects choice of treatment. Again, the majority of 230 lung cancer cell lines (including adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and small cell carcinoma) have majority European ancestry. Only four cell lines have Native American (Q2) components >5% (COLO668: 16.6%, HS618T: 21.6%, NCI-H716: 14.7%, NCI-H1435: 15.6%) and 75 cell lines have Asian ancestral components (Q3, Q4, Q5) >5% and 31 cell lines have African ancestral components (Q7) >5%.

Estimated Cell Line Ancestry

Using the estimated ancestry from the cell line panels and the 1000 Genome populations (described above), we have developed an online, interactive and searchable web-based tool that allows visualizing and exporting of publication-quality figures for the estimated genetic ancestry and population structure of cancer cell lines in relation to reference populations of the 1000 Genomes project. For all samples, the contribution of each inferred ancestral population to the genome is quantified and available via tooltips. The tool can be accessed at http://ecla.moffitt.org/.

The application visualizes a t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) (136) plot (Figure 1) of the genotype data for both the 1kG populations and the cell lines. A mouse-over tooltip provides detailed information on the sample. For all samples, the sample name is indicated as well as Q1-Q7 admixture proportions. The 1kG population sample detail includes the population and super-population codes. The cell line detail includes whether it is in CCLE and/or COSMIC, as well as the reported tissue type. The reported ethnicity of the cell line is also included (or NA if not available). All available annotation information on the cell lines and 1kG reference samples are present in table form in the ‘Table: Cell Line’ or ‘Table: Ref’ tabs of the application.

The 1kG clusters can be visually annotated by 1kG population or 1kG super-population. Cell lines are not assigned to clusters by default but are indicated by small, purple circles. Several options exist to categorize cell lines. Cell lines can be annotated by the reported ethnicity from the cell line panel (although a large proportion are missing ethnicity annotation); by admixture score (Q1-Q7); or from cluster association using a graph-based clustering approach. The graph-based clustering approach, Infomap (137), is used to detect community structure from the adjacency graph of each sample’s 30 nearest neighbors (in Principal Component space).

Search functionality is built into the application so that a cell line (e.g. A-549) or all cell lines (‘cell’) can be highlighted. Reference 1kG populations and super-populations (e.g MXL) can also be searched and highlighted. This functionality allows a researcher to quickly identify the estimated genetic ancestry of the cell line being considered, with respect to reference 1kG populations. The tool also allows searching and highlighting of cell lines by the “Reported Ethnicity” terms or by cell line tissues of origin.

Additional views in this tool include the 2-dimensional principal components (PCA) plot with the same functionality as the t-SNE clustering. Side-by-side plots of t-SNE and PCA can also be selected to visualize particular populations or cell lines in both visualizations simultaneously. Given the complexity of the data being represented, a 3 dimensional t-SNE clustering is also available interactively so that the view can be rotated in three dimensions to see additional structure. Finally, the t-SNE plot can be annotated with the admixture memberships (Q1-Q7) as a further method of exploring additional structure in this clustering.

This tool enables a researcher to explore the CCLE and COSMIC cell line panels with respect to 1kG reference populations. A researcher can use this tool to select cancer cell lines for study that better represent the population under examination. Further, when researchers perform drug cancer screenings or mechanistic studies, the effect of genetic ancestry can be considered in the analysis. Further descriptions of the tool and methods for generating the data are available in Supplemental Data and Methods.

Concluding remarks

In summary, we identify an important gap in our knowledge and understanding of genetic-based disparities within cancer research. Most cancer studies have not systematically taken into consideration the ancestry composition in the cell lines used to model the disease in vitro. To mitigate this problem we present an interactive tool that allows the investigation of specific global ancestry in cell line models. We expect this resource to allow a direct examination of ancestry in cell line models and to direct efforts to redress the underrepresentation in cancer types with clear disparities. Incorporating estimated genetic ancestry within cell line molecular biology and drug discovery studies can significantly improve the rigor and reproducibility of cancer research activities, not just those explicitly examining the role of genetic ancestry in cancer biology.

Supplementary Material

1

2

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the PHSU-MCC Partnership (NCI U54 CA163071 and U54 CA163068) under the Developmental Grant program and the Quantitative Sciences Core; by NCI 1SC1CA182845; and by the Cancer Informatics Shared Resource at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292).

Financial support:

This work was supported by the PHSU-MCC Partnership (NCI U54 CA163071 and U54 CA163068) under the Developmental Grant program and the Quantitative Sciences Core; by NCI 1SC1CA182845; and by the Cancer Informatics Shared Resource at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292).

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:7–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NIH guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research. Fed Regist Volume 59: National Institutes of Health; 1994. p 14508–13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moy B, Polite BN, Halpern MT, Stranne SK, Winer EP, Wollins DS, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: opportunities in the patient protection and affordable care act to reduce cancer care disparities. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3816–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh SS, Galanter J, Thakur N, Pino-Yanes M, Barcelo NE, White MJ, et al. Diversity in Clinical and Biomedical Research: A Promise Yet to Be Fulfilled. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickmann LJ, Schutzman JL. Racial and Ethnic Composition of Cancer Clinical Drug Trials: How Diverse Are We? Oncologist 2018;23:243–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geller SE, Koch AR, Roesch P, Filut A, Hallgren E, Carnes M. The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same: A Study to Evaluate Compliance With Inclusion and Assessment of Women and Minorities in Randomized Controlled Trials. Acad Med 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Chen MS Jr., Lara PN, Dang JH, Paterniti DA, Kelly K Twenty years post-NIH Revitalization Act: enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT): laying the groundwork for improving minority clinical trial accrual: renewing the case for enhancing minority participation in cancer clinical trials. Cancer 2014;120 Suppl 7:1091–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozdemir BC, Dotto GP. Racial Differences in Cancer Susceptibility and Survival: More Than the Color of the Skin? Trends Cancer 2017;3:181–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan DS, Mok TS, Rebbeck TR. Cancer Genomics: Diversity and Disparity Across Ethnicity and Geography. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:91–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerend MA, Pai M. Social determinants of Black-White disparities in breast cancer mortality: a review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17:2913–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hastert TA, Beresford SA, Sheppard L, White E. Disparities in cancer incidence and mortality by area-level socioeconomic status: a multilevel analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:168–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang CM, Su YC, Lai NS, Huang KY, Chien SH, Chang YH, et al. The combined effect of individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status on cancer survival rates. PLoS One 2012;7:e44325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wogan GN, Hecht SS, Felton JS, Conney AH, Loeb LA. Environmental and chemical carcinogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol 2004;14:473–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shavers VL, Brown ML. Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:334–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallace TA, Martin DN, Ambs S. Interactions among genes, tumor biology and the environment in cancer health disparities: examining the evidence on a national and global scale. Carcinogenesis 2011;32:1107–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braun L Race, ethnicity, and health: can genetics explain disparities? Perspect Biol Med 2002;45:159–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins FS. What we do and don’t know about ‘race’, ‘ethnicity’, genetics and health at the dawn of the genome era. Nat Genet 2004;36:S13–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mersha TB, Abebe T. Self-reported race/ethnicity in the age of genomic research: its potential impact on understanding health disparities. Hum Genomics 2015;9:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Royal CD, Dunston GM. Changing the paradigm from ‘race’ to human genome variation. Nat Genet 2004;36:S5–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Outram SM, Ellison GT. Anthropological insights into the use of race/ethnicity to explore genetic contributions to disparities in health. J Biosoc Sci 2006;38:83–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bamshad M, Guthery SL. Race, genetics and medicine: does the color of a leopard’s spots matter? Curr Opin Pediatr 2007;19:613–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torres JB, Kittles RA. The relationship between “race” and genetics in biomedical research. Curr Hypertens Rep 2007;9:196–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foster MW, Sharp RR. Race, ethnicity, and genomics: social classifications as proxies of biological heterogeneity. Genome Res 2002;12:844–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Genomes Project C, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015;526:68–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thornton TA, Bermejo JL. Local and global ancestry inference and applications to genetic association analysis for admixed populations. Genet Epidemiol 2014;38 Suppl 1:S5–S12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorusso L The justification of race in biological explanation. J Med Ethics 2011;37:535–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haiman CA, Stram DO. Exploring genetic susceptibility to cancer in diverse populations. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2010;20:330–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bustamante CD, Burchard EG, De la Vega FM. Genomics for the world. Nature 2011;475:163–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park SL, Cheng I, Haiman CA. Genome-Wide Association Studies of Cancer in Diverse Populations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2018;27:405–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathieson I, McVean G. Differential confounding of rare and common variants in spatially structured populations. Nat Genet 2012;44:243–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clayton DG, Walker NM, Smyth DJ, Pask R, Cooper JD, Maier LM, et al. Population structure, differential bias and genomic control in a large-scale, case-control association study. Nat Genet 2005;37:1243–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marchini J, Cardon LR, Phillips MS, Donnelly P. The effects of human population structure on large genetic association studies. Nat Genet 2004;36:512–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang S, Qian F, Zheng Y, Ogundiran T, Ojengbede O, Zheng W, et al. Genetic variants demonstrating flip-flop phenomenon and breast cancer risk prediction among women of African ancestry. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018;168:703–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Popejoy AB, Fullerton SM. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature 2016;538:161–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spratt DE, Chan T, Waldron L, Speers C, Feng FY, Ogunwobi OO, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Genomic Sequencing. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1070–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spratt DE. Are we inadvertently widening the disparity gap in pursuit of precision oncology? Br J Cancer 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Ramamoorthy A, Pacanowski MA, Bull J, Zhang L. Racial/ethnic differences in drug disposition and response: review of recently approved drugs. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2015;97:263–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Claw KG, Anderson MZ, Begay RL, Tsosie KS, Fox K, Garrison NA, et al. A framework for enhancing ethical genomic research with Indigenous communities. Nat Commun 2018;9:2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith CJ, Minas TZ, Ambs S. Analysis of Tumor Biology to Advance Cancer Health Disparity Research. Am J Pathol 2018;188:304–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yedjou CG, Tchounwou PB, Payton M, Miele L, Fonseca DD, Lowe L, et al. Assessing the Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Breast Cancer Mortality in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Lynce F, Graves KD, Jandorf L, Ricker C, Castro E, Moreno L, et al. Genomic Disparities in Breast Cancer Among Latinas. Cancer Control 2016;23:359–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daly B, Olopade OI. A perfect storm: How tumor biology, genomics, and health care delivery patterns collide to create a racial survival disparity in breast cancer and proposed interventions for change. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:221–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng W, Long J, Gao YT, Li C, Zheng Y, Xiang YB, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a new breast cancer susceptibility locus at 6q25.1. Nat Genet 2009;41:324–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cai Q, Wen W, Qu S, Li G, Egan KM, Chen K, et al. Replication and functional genomic analyses of the breast cancer susceptibility locus at 6q25.1 generalize its importance in women of chinese, Japanese, and European ancestry. Cancer Res 2011;71:1344–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stacey SN, Sulem P, Zanon C, Gudjonsson SA, Thorleifsson G, Helgason A, et al. Ancestry-shift refinement mapping of the C6orf97-ESR1 breast cancer susceptibility locus. PLoS Genet 2010;6:e1001029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng W, Cai Q, Signorello LB, Long J, Hargreaves MK, Deming SL, et al. Evaluation of 11 breast cancer susceptibility loci in African-American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:2761–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hutter CM, Young AM, Ochs-Balcom HM, Carty CL, Wang T, Chen CT, et al. Replication of breast cancer GWAS susceptibility loci in the Women’s Health Initiative African American SHARe Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011;20:1950–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huo D, Zheng Y, Ogundiran TO, Adebamowo C, Nathanson KL, Domchek SM, et al. Evaluation of 19 susceptibility loci of breast cancer in women of African ancestry. Carcinogenesis 2012;33:835–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu Q, Shepherd L, Lunetta KL, Yao S, Liu Q, Hu Q, et al. Trans-ethnic follow-up of breast cancer GWAS hits using the preferential linkage disequilibrium approach. Oncotarget 2016;7:83160–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fejerman L, Ahmadiyeh N, Hu D, Huntsman S, Beckman KB, Caswell JL, et al. Genome-wide association study of breast cancer in Latinas identifies novel protective variants on 6q25. Nat Commun 2014;5:5260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dean M, Boland J, Yeager M, Im KM, Garland L, Rodriguez-Herrera M, et al. Addressing health disparities in Hispanic breast cancer: accurate and inexpensive sequencing of BRCA1 and BRCA2. Gigascience 2015;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dutil J, Golubeva VA, Pacheco-Torres AL, Diaz-Zabala HJ, Matta JL, Monteiro AN. The spectrum of BRCA1 and BRCA2 alleles in Latin America and the Caribbean: a clinical perspective. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015;154:441–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pal T, Bonner D, Cragun D, Monteiro AN, Phelan C, Servais L, et al. A high frequency of BRCA mutations in young black women with breast cancer residing in Florida. Cancer 2015;121:4173–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weitzel JN, Clague J, Martir-Negron A, Ogaz R, Herzog J, Ricker C, et al. Prevalence and type of BRCA mutations in Hispanics undergoing genetic cancer risk assessment in the southwestern United States: a report from the Clinical Cancer Genetics Community Research Network. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:210–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jiagge E, Jibril AS, Chitale D, Bensenhaver JM, Awuah B, Hoenerhoff M, et al. Comparative Analysis of Breast Cancer Phenotypes in African American, White American, and West Versus East African patients: Correlation Between African Ancestry and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23:3843–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1938–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schwartz T, Stark A, Pang J, Awuah B, Kleer CG, Quayson S, et al. Expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 as a marker of mammary stem cells in benign and malignant breast lesions of Ghanaian women. Cancer 2013;119:488–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nalwoga H, Arnes JB, Wabinga H, Akslen LA. Expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) is associated with basal-like markers and features of aggressive tumours in African breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2010;102:369–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiagge E, Chitale D, Newman LA. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer, Stem Cells, and African Ancestry. Am J Pathol 2018;188:271–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lindner R, Sullivan C, Offor O, Lezon-Geyda K, Halligan K, Fischbach N, et al. Molecular phenotypes in triple negative breast cancer from African American patients suggest targets for therapy. PLoS One 2013;8:e71915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Keenan T, Moy B, Mroz EA, Ross K, Niemierko A, Rocco JW, et al. Comparison of the Genomic Landscape Between Primary Breast Cancer in African American Versus White Women and the Association of Racial Differences With Tumor Recurrence. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3621–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martinez ME, Gomez SL, Tao L, Cress R, Rodriguez D, Unkart J, et al. Contribution of clinical and socioeconomic factors to differences in breast cancer subtype and mortality between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;166:185–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martinez ME, Nielson CM, Nagle R, Lopez AM, Kim C, Thompson P. Breast cancer among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women in Arizona. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2007;18:130–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen L, Li CI. Racial disparities in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment by hormone receptor and HER2 status. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2015;24:1666–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Li CI, Chen VW, Clarke CA, Ries LA, et al. US incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Ooi SL, Martinez ME, Li CI. Disparities in breast cancer characteristics and outcomes by race/ethnicity. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;127:729–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Banegas MP, Li CI. Breast cancer characteristics and outcomes among Hispanic Black and Hispanic White women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;134:1297–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lara-Medina F, Perez-Sanchez V, Saavedra-Perez D, Blake-Cerda M, Arce C, Motola-Kuba D, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer in Hispanic patients: high prevalence, poor prognosis, and association with menopausal status, body mass index, and parity. Cancer 2011;117:3658–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Parise C, Caggiano V. Disparities in the risk of the ER/PR/HER2 breast cancer subtypes among Asian Americans in California. Cancer Epidemiol 2014;38:556–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thorsson V, Gibbs DL, Brown SD, Wolf D, Bortone DS, Ou Yang TH, et al. The Immune Landscape of Cancer. Immunity 2018;48:812–30 e14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gazdar AF, Gao B, Minna JD. Lung cancer cell lines: Useless artifacts or invaluable tools for medical science? Lung Cancer 2010;68:309–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gazdar AF, Girard L, Lockwood WW, Lam WL, Minna JD. Lung cancer cell lines as tools for biomedical discovery and research. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1310–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Comsa S, Cimpean AM, Raica M. The Story of MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cell Line: 40 years of Experience in Research. Anticancer Res 2015;35:3147–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neve RM, Chin K, Fridlyand J, Yeh J, Baehner FL, Fevr T, et al. A collection of breast cancer cell lines for the study of functionally distinct cancer subtypes. Cancer Cell 2006;10:515–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Anglesio MS, Wiegand KC, Melnyk N, Chow C, Salamanca C, Prentice LM, et al. Type-specific cell line models for type-specific ovarian cancer research. PLoS One 2013;8:e72162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kreuzinger C, Gamperl M, Wolf A, Heinze G, Geroldinger A, Lambrechts D, et al. Molecular characterization of 7 new established cell lines from high grade serous ovarian cancer. Cancer Lett 2015;362:218–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shoemaker RH. The NCI60 human tumour cell line anticancer drug screen. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:813–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Niu N, Wang L. In vitro human cell line models to predict clinical response to anticancer drugs. Pharmacogenomics 2015;16:273–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Caponigro G, Sellers WR. Advances in the preclinical testing of cancer therapeutic hypotheses. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2011;10:179–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang W, Soares J, Greninger P, Edelman EJ, Lightfoot H, Forbes S, et al. Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC): a resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:D955–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature 2012;483:603–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Forbes SA, Bindal N, Bamford S, Cole C, Kok CY, Beare D, et al. COSMIC: mining complete cancer genomes in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 2011;39:D945–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Forbes SA, Tang G, Bindal N, Bamford S, Dawson E, Cole C, et al. COSMIC (the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer): a resource to investigate acquired mutations in human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38:D652–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Seashore-Ludlow B, Rees MG, Cheah JH, Cokol M, Price EV, Coletti ME, et al. Harnessing Connectivity in a Large-Scale Small-Molecule Sensitivity Dataset. Cancer Discov 2015;5:1210–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McDermott U, Sharma SV, Settleman J. High-throughput lung cancer cell line screening for genotype-correlated sensitivity to an EGFR kinase inhibitor. Methods Enzymol 2008;438:331–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sharma SV, Haber DA, Settleman J. Cell line-based platforms to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of candidate anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer 2010;10:241–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Goodspeed A, Heiser LM, Gray JW, Costello JC. Tumor-Derived Cell Lines as Molecular Models of Cancer Pharmacogenomics. Mol Cancer Res 2016;14:3–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kong D, Yamori T. JFCR39, a panel of 39 human cancer cell lines, and its application in the discovery and development of anticancer drugs. Bioorg Med Chem 2012;20:1947–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Weinstein JN, Myers TG, O’Connor PM, Friend SH, Fornace AJ Jr., Kohn KW, et al. An information-intensive approach to the molecular pharmacology of cancer. Science 1997;275:343–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Paull KD, Shoemaker RH, Hodes L, Monks A, Scudiero DA, Rubinstein L, et al. Display and analysis of patterns of differential activity of drugs against human tumor cell lines: development of mean graph and COMPARE algorithm. J Natl Cancer Inst 1989;81:1088–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shi LM, Myers TG, Fan Y, O’Connor PM, Paull KD, Friend SH, et al. Mining the National Cancer Institute Anticancer Drug Discovery Database: cluster analysis of ellipticine analogs with p53-inverse and central nervous system-selective patterns of activity. Mol Pharmacol 1998;53:241–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shankavaram UT, Varma S, Kane D, Sunshine M, Chary KK, Reinhold WC, et al. CellMiner: a relational database and query tool for the NCI-60 cancer cell lines. BMC Genomics 2009;10:277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chabner BA, Roberts TG Jr. Timeline: Chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2005;5:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Monks A, Scudiero D, Skehan P, Shoemaker R, Paull K, Vistica D, et al. Feasibility of a high-flux anticancer drug screen using a diverse panel of cultured human tumor cell lines. J Natl Cancer Inst 1991;83:757–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Holbeck SL, Collins JM, Doroshow JH. Analysis of Food and Drug Administration-approved anticancer agents in the NCI60 panel of human tumor cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther 2010;9:1451–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Greshock J, Bachman KE, Degenhardt YY, Jing J, Wen YH, Eastman S, et al. Molecular target class is predictive of in vitro response profile. Cancer Res 2010;70:3677–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zeeberg BR, Kohn KW, Kahn A, Larionov V, Weinstein JN, Reinhold W, et al. Concordance of gene expression and functional correlation patterns across the NCI-60 cell lines and the Cancer Genome Atlas glioblastoma samples. PLoS One 2012;7:e40062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weinstein JN, Pommier Y. Transcriptomic analysis of the NCI-60 cancer cell lines. C R Biol 2003;326:909–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Staunton JE, Slonim DK, Coller HA, Tamayo P, Angelo MJ, Park J, et al. Chemosensitivity prediction by transcriptional profiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:10787–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.McDermott U, Sharma SV, Dowell L, Greninger P, Montagut C, Lamb J, et al. Identification of genotype-correlated sensitivity to selective kinase inhibitors by using high-throughput tumor cell line profiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:19936–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sos ML, Michel K, Zander T, Weiss J, Frommolt P, Peifer M, et al. Predicting drug susceptibility of non-small cell lung cancers based on genetic lesions. J Clin Invest 2009;119:1727–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Varma S, Pommier Y, Sunshine M, Weinstein JN, Reinhold WC. High resolution copy number variation data in the NCI-60 cancer cell lines from whole genome microarrays accessible through CellMiner. PLoS One 2014;9:e92047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Park ES, Rabinovsky R, Carey M, Hennessy BT, Agarwal R, Liu W, et al. Integrative analysis of proteomic signatures, mutations, and drug responsiveness in the NCI 60 cancer cell line set. Mol Cancer Ther 2010;9:257–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ummanni R, Mannsperger HA, Sonntag J, Oswald M, Sharma AK, Konig R, et al. Evaluation of reverse phase protein array (RPPA)-based pathway-activation profiling in 84 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines as platform for cancer proteomics and biomarker discovery. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014;1844:950–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gholami AM, Hahne H, Wu Z, Auer FJ, Meng C, Wilhelm M, et al. Global proteome analysis of the NCI-60 cell line panel. Cell Rep 2013;4:609–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lamb J, Crawford ED, Peck D, Modell JW, Blat IC, Wrobel MJ, et al. The Connectivity Map: using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science 2006;313:1929–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Subramanian A, Narayan R, Corsello SM, Peck DD, Natoli TE, Lu X, et al. A Next Generation Connectivity Map: L1000 Platform and the First 1,000,000 Profiles. Cell 2017;171:1437–52 e17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Amundson SA, Do KT, Vinikoor LC, Lee RA, Koch-Paiz CA, Ahn J, et al. Integrating global gene expression and radiation survival parameters across the 60 cell lines of the National Cancer Institute Anticancer Drug Screen. Cancer Res 2008;68:415–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Guo WF, Lin RX, Huang J, Zhou Z, Yang J, Guo GZ, et al. Identification of differentially expressed genes contributing to radioresistance in lung cancer cells using microarray analysis. Radiat Res 2005;164:27–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li Z, Xia L, Lee LM, Khaletskiy A, Wang J, Wong JY, et al. Effector genes altered in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells after exposure to fractionated ionizing radiation. Radiat Res 2001;155:543–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Torres-Roca JF, Eschrich S, Zhao H, Bloom G, Sung J, McCarthy S, et al. Prediction of radiation sensitivity using a gene expression classifier. Cancer Res 2005;65:7169–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jain M, Nilsson R, Sharma S, Madhusudhan N, Kitami T, Souza AL, et al. Metabolite profiling identifies a key role for glycine in rapid cancer cell proliferation. Science 2012;336:1040–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhao N, Liu Y, Wei Y, Yan Z, Zhang Q, Wu C, et al. Optimization of cell lines as tumour models by integrating multi-omics data. Brief Bioinform 2017;18:515–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Domcke S, Sinha R, Levine DA, Sander C, Schultz N. Evaluating cell lines as tumour models by comparison of genomic profiles. Nat Commun 2013;4:2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Vincent KM, Findlay SD, Postovit LM. Assessing breast cancer cell lines as tumour models by comparison of mRNA expression profiles. Breast Cancer Res 2015;17:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yu M, Selvaraj SK, Liang-Chu MM, Aghajani S, Busse M, Yuan J, et al. A resource for cell line authentication, annotation and quality control. Nature 2015;520:307–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.American Type Culture Collection Standards Development Organization Workgroup ASN. Cell line misidentification: the beginning of the end. Nat Rev Cancer 2010;10:441–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Capes-Davis A, Theodosopoulos G, Atkin I, Drexler HG, Kohara A, MacLeod RA, et al. Check your cultures! A list of cross-contaminated or misidentified cell lines. Int J Cancer 2010;127:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Fusenig NE, Capes-Davis A, Bianchini F, Sundell S, Lichter P. The need for a worldwide consensus for cell line authentication: Experience implementing a mandatory requirement at the International Journal of Cancer. PLoS Biol 2017;15:e2001438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hay RJ. Human cells and cell cultures: availability, authentication and future prospects. Hum Cell 1996;9:143–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wilding JL, Bodmer WF. Cancer cell lines for drug discovery and development. Cancer Res 2014;74:2377–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Daniel VC, Marchionni L, Hierman JS, Rhodes JT, Devereux WL, Rudin CM, et al. A primary xenograft model of small-cell lung cancer reveals irreversible changes in gene expression imposed by culture in vitro. Cancer Res 2009;69:3364–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Borrell B How accurate are cancer cell lines? Nature 2010;463:858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gillet JP, Varma S, Gottesman MM. The clinical relevance of cancer cell lines. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:452–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ben-David U, Siranosian B, Ha G, Tang H, Oren Y, Hinohara K, et al. Genetic and transcriptional evolution alters cancer cell line drug response. Nature 2018;560:325–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wilson D A Troubled Past? Reassessing Ethics in the History of Tissue Culture. Health Care Anal 2016;24:246–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Skloot R The immortal life of Henrietta Lacks New York: Crown Publishers; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Nisbet MC, Fahy D. Bioethics in popular science: evaluating the media impact of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks on the biobank debate. BMC Med Ethics 2013;14:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Smith JD, Birkeland AC, Goldman EB, Brenner JC, Carey TE, Spector-Bagdady K, et al. Immortal Life of the Common Rule: Ethics, Consent, and the Future of Cancer Research. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:1879–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Beskow LM. Lessons from HeLa Cells: The Ethics and Policy of Biospecimens. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2016;17:395–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med 2015;372:793–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.National Research Council (US) Committee on A Framework for Developing a New Taxonomy of Disease. Toward Precision Medicine: Building a Knowledge Network for Biomedical Research and a New Taxonomy of Disease Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Woods-Burnham L, Basu A, Cajigas-Du Ross CK, Love A, Yates C, De Leon M, et al. The 22Rv1 prostate cancer cell line carries mixed genetic ancestry: Implications for prostate cancer health disparities research using pre-clinical models. Prostate 2017;77:1601–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Menden MP, Casale FP, Stephan J, Bignell GR, Iorio F, McDermott U, et al. The germline genetic component of drug sensitivity in cancer cell lines. Nat Commun 2018;9:3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res 2009;19:1655–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.van der Maaten LJP, Hinton GE. Visualizing High-Dimensional Data Using t-SNE. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2008;9:2579–605 [Google Scholar]

- 137.Rosvall M, Bergstrom CT. Maps of random walks on complex networks reveal community structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:1118–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Bairoch A The Cellosaurus, a Cell-Line Knowledge Resource. J Biomol Tech 2018;29:25–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Forbes SA, Beare D, Boutselakis H, Bamford S, Bindal N, Tate J, et al. COSMIC: somatic cancer genetics at high-resolution. Nucleic Acids Res 2017;45:D777–D83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Barrett T, Clark K, Gevorgyan R, Gorelenkov V, Gribov E, Karsch-Mizrachi I, et al. BioProject and BioSample databases at NCBI: facilitating capture and organization of metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40:D57–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Tang H, Quertermous T, Rodriguez B, Kardia SL, Zhu X, Brown A, et al. Genetic structure, self-identified race/ethnicity, and confounding in case-control association studies. Am J Hum Genet 2005;76:268–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Banda Y, Kvale MN, Hoffmann TJ, Hesselson SE, Ranatunga D, Tang H, et al. Characterizing Race/Ethnicity and Genetic Ancestry for 100,000 Subjects in the Genetic Epidemiology Research on Adult Health and Aging (GERA) Cohort. Genetics 2015;200:1285–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Sinha M, Larkin EK, Elston RC, Redline S. Self-reported race and genetic admixture. N Engl J Med 2006;354:421–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Yaeger R, Avila-Bront A, Abdul K, Nolan PC, Grann VR, Birchette MG, et al. Comparing genetic ancestry and self-described race in african americans born in the United States and in Africa. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17:1329–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Lins TC, Vieira RG, Abreu BS, Gentil P, Moreno-Lima R, Oliveira RJ, et al. Genetic heterogeneity of self-reported ancestry groups in an admixed Brazilian population. J Epidemiol 2011;21:240–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Klimentidis YC, Miller GF, Shriver MD. Genetic admixture, self-reported ethnicity, self-estimated admixture, and skin pigmentation among Hispanics and Native Americans. Am J Phys Anthropol 2009;138:375–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Chakraborty R, Sellers TA, Schwartz AG. Examining population stratification via individual ancestry estimates versus self-reported race. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:1545–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Risch N, Burchard E, Ziv E, Tang H. Categorization of humans in biomedical research: genes, race and disease. Genome Biol 2002;3:comment2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Burchard EG, Ziv E, Coyle N, Gomez SL, Tang H, Karter AJ, et al. The importance of race and ethnic background in biomedical research and clinical practice. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1170–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Haiman CA, Chen GK, Blot WJ, Strom SS, Berndt SI, Kittles RA, et al. Genome-wide association study of prostate cancer in men of African ancestry identifies a susceptibility locus at 17q21. Nat Genet 2011;43:570–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Hoffmann TJ, Van Den Eeden SK, Sakoda LC, Jorgenson E, Habel LA, Graff RE, et al. A large multiethnic genome-wide association study of prostate cancer identifies novel risk variants and substantial ethnic differences. Cancer Discov 2015;5:878–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Conti DV, Wang K, Sheng X, Bensen JT, Hazelett DJ, Cook MB, et al. Two Novel Susceptibility Loci for Prostate Cancer in Men of African Ancestry. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Jaratlerdsiri W, Chan EKF, Gong T, Petersen DC, Kalsbeek AMF, Venter PA, et al. Whole Genome Sequencing Reveals Elevated Tumor Mutational Burden and Initiating Driver Mutations in African Men with Treatment-Naive, High-Risk Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res 2018 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 154.Williams VL, Awasthi S, Fink AK, Pow-Sang JM, Park JY, Gerke T, et al. African-American men and prostate cancer-specific mortality: a competing risk analysis of a large institutional cohort, 1989–2015. Cancer Med 2018;7:2160–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E359–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Ruiz-Garcia E, Guadarrama-Orozco J, Vidal-Millan S, Lino-Silva LS, Lopez-Camarillo C, Astudillo-de la Vega H. Gastric cancer in Latin America. Scand J Gastroenterol 2018;53:124–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Altekruse S, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2013. Based on November 2015 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 158.Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2015–2017 American Cancer Society. [Google Scholar]

- 159.Shi Y, Au JS, Thongprasert S, Srinivasan S, Tsai CM, Khoa MT, et al. A prospective, molecular epidemiology study of EGFR mutations in Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer of adenocarcinoma histology (PIONEER). J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:154–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Cress WD, Chiappori A, Santiago P, Munoz-Antonia T. Lung cancer mutations and use of targeted agents in Hispanics. Rev Recent Clin Trials 2014;9:225–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Arrieta O, Cardona AF, Martin C, Mas-Lopez L, Corrales-Rodriguez L, Bramuglia G, et al. Updated Frequency of EGFR and KRAS Mutations in NonSmall-Cell Lung Cancer in Latin America: The Latin-American Consortium for the Investigation of Lung Cancer (CLICaP). J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:838–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1

2